Abstract

Immigration has been historically and contemporarily racialized in the United States. Although each immigrant group has unique histories, current patterns, and specific experiences, racialized immigrant groups such as Latino, Asian, and Arab immigrants all experience health inequities that are not solely due to nativity or years of residence but also influenced by conditional citizenship and subjective sense of belonging or othering. Critical race theory and intersectionality provide a critical lens to consider how structural racism might uniquely impact the health of racialized immigrants, and to understand and intervene on the interlocking systems that shape these shared experiences and health consequences. We build on and synthesize the work of prior scholars to advance how society codifies structural disadvantages for racialized immigrants into governmental and institutional policies and how that impacts health via three key pathways that emerged from our review of the literature: (1) Formal racialization via immigration policy and citizenship status that curtails access to material and health resources and political and civic participation; (2) Informal racialization via disproportionate immigration enforcement and criminalization including on-going threats of detention and deportation; and (3) Intersections with economic exploitation and disinvestment such as labor exploitation and neighborhood disinvestment. We hope this serves as a call to action to change the dominant narratives around immigrant health, provides conceptual and methodological recommendations to advance research, and illuminates the essential role of the public health sector to advocate for changes in other sectors including immigration policy, political rights, law enforcement, labor protections, and neighborhood investment, among others.

Keywords: structural racism, immigrant health, health inequities, Latino Americans, Asian Americans, Arab Americans

Introduction

The role of structural racism on population health, particularly health inequities, is gaining traction in public health discourse in the United States. Given its consistent linkages to differences in health outcomes, race, a social construct with no identified biological underpinnings, remains an important factor in health research (Krieger, 2000). These race-based health inequities are attributable to racism, whereby the social construction of race suggests that some racial groups are inferior to others and should be treated differently, leading to devaluation, disempowerment, and differential allocation of power, resources, and opportunities (Williams, Lawrence, & Davis, 2019). This is due in large part to white supremacy, a political, economic, social, and cultural system that affords white people with disproportionate power, resources, and opportunities that engenders structural advantages across institutions and settings; this white privilege both consciously and unconsciously perpetuates the notion that those classified as white are superior to other racial groups and should retain this dominance (Rollock & Gillborn, 2011). Structural racism enumerates the totality of ways in which society codifies white supremacy and racial hierarchy into governmental and institutional policies through mutually reinforcing systems including housing, labor, and credit markets, and education, economic, healthcare, and criminal justice systems. These patterns then reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and practices (Bailey et al., 2017; Williams, Lawrence, & Davis, 2019). Thus, structural racism functions as a fundamental cause of disease, enumerating direct and indirect pathways to health that operate similarly even as specific outcomes change across time and place (Phelan & Link, 2015; Williams & Mohammed, 2013).

Critical race theory highlights the centrality of racism in U.S. society and emphasizes the need to be conscious of racism and its contemporary mechanisms in the pursuit of equity, including in public health scholarship and action-oriented systems change. A central tenet of critical race theory is intersectionality, or the multiple complex systems of subordination that can occur simultaneously, such as race, immigration, class, and gender (Ford & Airhihenbuwa, 2010). Given the historical and contemporary context of race in the United States, the majority of discussion on racism and population health has appropriately centered on Black and Indigenous communities while sometimes considering people of color more broadly. However, data also reveal health inequities for Latino and Asian immigrants (Williams & Mohammed, 2013), and potentially for Arab immigrants (i.e., from Arab-speaking countries in the Middle East and North Africa), a group missing from research due to their classification as ‘white’ despite racialization as ‘non-white’ (Abboud, Chebli, & Rabelais, 2019). Although beyond the scope of this paper, we note that there are also African immigrants who experience a different health profile than the majority of Black people in the United States who are multigenerational descendants of enslaved peoples forcibly brought over from Africa during the 17th and 18th centuries (Venters & Gany, 2011). The focus on immigrants is particularly relevant given that 13.7% of the U.S. population (>40 million people) is born outside the United States (Budiman, 2020), and close to 30% of the population is “immigrant-influenced;” that is, immigrants and their family members, including U.S.-born spouses and children (Hirschman, 2005). These proportions will only increase over time – and are already more pronounced in large metropolitan areas, such as New York City (38% foreign-born) (NYC Planning, 2017).

To date, immigrant health research has primarily focused on behavioral factors such as health service utilization, treatment adherence, preventive screenings, and diet and exercise; acculturation processes; and culturally competent interventions (Castañeda et al., 2015). Studies also investigate the “immigrant paradox,” where despite socioeconomic disadvantage, recent immigrants often appear to have better health than those with longer residence or birth in the United States, although actual findings are mixed (Alcántara, Estevez, & Alegría, 2017). Surprisingly, potential explanations for this paradox do not typically consider the harmful effects of being racialized once in the United States (Abraído-Lanza, Echeverría, & Flórez, 2016). However, there are growing calls to consider the role of structural racism on immigrant health, including intersections with other racialized dimensions such as citizenship status, country of origin, language abilities, religion, and socioeconomic status (Asad & Clair, 2018; Sáenz & Douglas, 2015; Viruell-Fuentes, Miranda, & Abdulrahim, 2012). This suggests health inequities for immigrants do not merely rely on nativity (born in the United States or elsewhere) or years of residence in the country but also on conditional citizenship and subjective sense of belonging or othering.

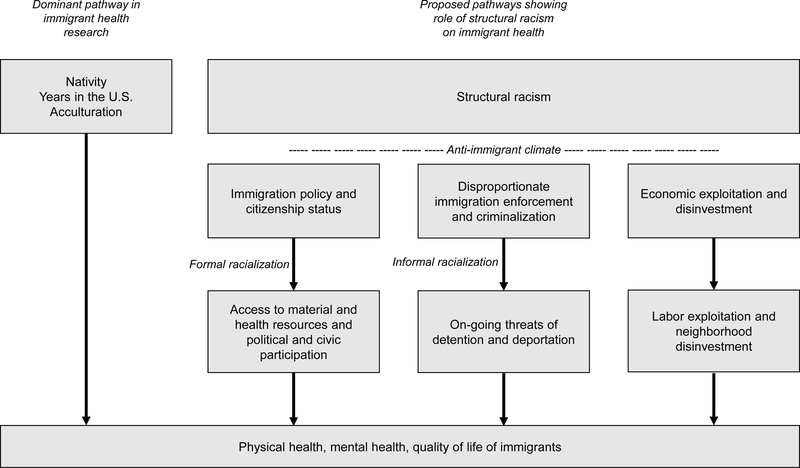

Although each immigrant group has unique histories, current patterns, and specific experiences, studies confirm that Latino, Asian, and Arab immigrant groups all experience higher rates of racial discrimination than white counterparts that affect health outcomes (Abuelezam, El-Sayed, & Galea, 2018; Andrade, Ford, & Alvarez, 2020; Carter et al., 2019; Gee et al., 2009; Samari, Alcalá, & Sharif, 2018), including in access to quality education, healthcare, and housing; inclusive political and civic participation; and equitable employment opportunities and police interactions (e.g., Findling et al., 2019; McMurtry et al., 2019; Nicholson, 2019). Critical race theory and intersectionality provide a critical lens to consider how structural racism might uniquely impact the health of racialized immigrants, and to understand and intervene on the interlocking systems that shape these shared experiences and health consequences. We build on and synthesize the work of prior scholars to advance how society codifies structural disadvantages for racialized immigrants into governmental and institutional policies and how that impacts health via three key pathways that emerged from our review of the literature: (1) Formal racialization via immigration policy and citizenship status that curtails access to material and health resources and political and civic participation; (2) Informal racialization via disproportionate immigration enforcement and criminalization including on-going threats of detention and deportation; and (3) Intersections with economic exploitation and disinvestment such as labor exploitation and neighborhood disinvestment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed pathways showing role of structural racism on immigrant health. (1) Formal racialization via immigration policy and citizenship status that curtails access to material and health resources and political and civic participation; (2) Informal racialization via disproportionate immigration enforcement and criminalization including on-going threats of detention and deportation; and (3) Intersections with economic exploitation and disinvestment such as labor exploitation and neighborhood disinvestment.

Setting the Context: Anti-Immigrant Climate

Integral across all three pathways are the ways in which structural racism codifies cultural racism. Culture refers to a society’s shared value and belief systems that ascribe social meaning, and cultural racism reflects the dominant racial group’s views toward the non-dominant groups; cultural racism is both structurally operationalized into policies and practices and dynamically shaped by them (Hicken et al., 2018; Williams & Mohammed, 2013). For immigrants, this cultural racism includes the everyday expressions of anti-immigrant sentiments in media and community, anti-immigrant rhetoric in political and personal discourse, and anti-immigrant violence such as hate crimes and harassment. While it is difficult to measure how anti-immigrant sentiments directly impact health, they create an environment that enables harmful immigration policies and enforcement that clearly worsen health and exacerbate inequities (Morey, 2018; Taylor, 2020). This anti-immigrant climate further intersects with the racialization of immigrants to perpetuate specific stereotypes that negate citizenship and belonging; for example, Latino Americans are presumed to be “illegal” (Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012), Asian Americans are seen as “perpetual foreigners” (Huynh, Devos, & Smalarz, 2011), and Arab Americans are seen as “terrorists,” “fanatics” and “enemies” whose faith conflicts with their loyalties to the state (Wray-Lake, Syvertsen, & Flanagan, 2008). While the specific stereotypes may evolve over time, their function is to maintain subordination in the racial hierarchy. This is particularly salient in the current context of increasing anti-immigrant sentiment, more restrictive policies (e.g., changes in visa, work, and residency rules), and aggressive enforcement (e.g., record highs in detention and deportation) promoted by the recent Trump administration (Fleming, Novak, & Lopez, 2019; Nichols, Lebrón, & Pedraza, 2018).

Immigration Policy, Citizenship Status, and Civic Participation

Structural racism is enacted when laws and policies are used to codify racial inequalities, which can then further contribute to racialization (Armenta, 2017). In the United States, immigration and race are deeply intertwined as immigration policy has been used to deliberately exclude specific groups from citizenship and its associated benefits, not only by restricting citizenship to those classified as ‘white’ but also by constructing racial categories for specific groups (Gee & Ford, 2011; Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012). In the early 20th century, Arab immigrants sought classification as ‘white’ in order to achieve citizenship (Abboud et al., 2019). Meanwhile, the flow of immigration from Latin America, Asia, and Africa was heavily restricted until immigration policy reform in 1965 removed quotas based on national origin, leading to a rapid influx of immigrants from those regions (Hirschman, 2005). This creation of distinct categories for immigration has contributed to on-going ideas of racial difference.

Immigration policy enacted at multiple levels of jurisdiction (e.g., federal, state, local), and perceptions of those policies, have negative impacts on immigrant health including higher mortality, poorer self-reported health, and poorer mental health (Perreira & Pedroza, 2019). While federal policy dictates citizenship status, state and local policies can expand or contract public benefits and restrictions (Philbin et al., 2018). For example, exclusionary state policies were associated with worse mental health for Latino compared to non-Latino people (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2017) while more inclusive state policies were associated with higher rates of health insurance for Latino non-citizens (although slightly lower rates for Asian non-citizens) (Young et al., 2019). Similarly, hostile policy contexts (which also fuel fears of becoming a “public charge”) can deter immigrants from accessing health-promoting resources for which they are eligible, leading to lower participation in public assistance and safety-net programs (Hardy et al., 2012; Perreira & Pedroza, 2019) and increased poverty (Wimer, Maury, & Bahl, 2018).

Citizenship status creates additional social stratifications (e.g., undocumented, discretionary, temporary, permanent) that offer differing degrees of legal protections that shape health risks, resources to manage those risks, and access to health-promoting services (Asad & Clair, 2018; Torres & Young, 2016). Available data suggest that undocumented individuals have worse health than documented individuals, with spillover effects to documented individuals, particularly those in mixed status families (Cabral & Cuevas, 2020). For some immigrants, their status may remain precarious as policies change (Castañeda et al., 2015). Health research is limited on temporary statuses such as those on restricted visas. Additionally, U.S.-born immigrant children may not have full access to the benefits afforded to them by citizenship because of their parents’ status or challenges such as language barriers (Javier et al., 2015), which may help explain observed inequities for immigrant children in health, access to healthcare, and other structures such as housing, education, and employment (Ayalew et al., 2021).

Citizenship status also determines access to political and civic representation. Not only are immigrants precluded from accessing many health-promoting resources, but the very tools used to enact structural change and increase access are also often infeasible for immigrants. For example, the decennial census, used for several vital purposes including legislative representation, resource allocation, and public health surveillance, is supposed to enumerate all residents regardless of citizenship status. However, efforts by the recent Trump administration to exclude undocumented immigrants have likely deterred participation from undocumented and mixed status households. Further, the lack of a racial/ethnic category for Arabs renders them invisible in the data (Abboud et al., 2019). Incomplete census data for immigrants could have substantial impacts on health due to an inadequate understanding of health patterns in these communities and a corresponding lack of resources. Similarly, elections are another common mechanism by which communities advocate for what they need to thrive. Immigrants who work, including undocumented workers, pay federal, state, and local income taxes but have no say in how their tax dollars are spent since only U.S. citizens are eligible to vote. Among eligible voters, targeted denaturalization efforts contribute to voter disenfranchisement and suppression (Shahshahani, 2020). There are similar citizenship restrictions on who can run for public office. Other forms of local civic engagement that are not directly tied to citizenship status (e.g., membership on school board) may not seem viable to those who fear it could still risk their status. Although the direct health consequences of the lack of political and civic engagement are difficult to document, the structural racism framework helps illuminate how these are additional mechanisms used to suppress power, resources, and opportunities for racialized immigrants.

Disproportionate Immigration Enforcement and Criminalization

While immigration policies influence health by constraining access to resources and political action, their health impacts are exacerbated by disproportionate immigration enforcement that deliberately target racialized groups (Fleming et al., 2019). Detention and deportation affect mental health (Von Werthern et al., 2018), including for children separated from families (Lovato et al., 2018) and for those who know someone who has been deported (Nichols et al., 2018). Further, the threat of detention and deportation deters engagement in health and social services, delays seeking care, and negatively affects physical and mental health for immigrants (Cabral & Cuevas, 2020; Fleming et al., 2019; Saadi et al., 2020). This is particularly salient given that the United States has the largest immigration detention system in the world, with mass deportations on the rise (Saadi et al., 2020). This threat impacts both undocumented and documented immigrants including those living in mixed status households; however, undocumented immigrants do not have access to the same legal recourses guaranteed to documented individuals (Armenta, 2017).

Immigration enforcement has resulted in criminalization of immigrants, in large part to changes in federal policies such as the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) that authorized Immigration and Custom Enforcement (ICE) to enforce federal immigration law via regular law enforcement activities by state and local agencies. This has been a major shift from a more humanitarian approach that promoted the welfare of individuals once in the United States. Most immigration enforcement occurs at the border, but there is also increasing targeted enforcement within borders (e.g., workplace raids) (Fleming et al., 2019; Perreira & Pedroza, 2019). Armenta (2017) describes this convergence of the criminal legal and immigration enforcement systems as “crimmigation,” where racialized practices by local law enforcement (e.g., disproportionate traffic stops) can then initiate immigration enforcement, with negative impacts for both undocumented and documented immigrants (Armenta, 2017). Similarly, policies like the Patriot Act and National Security Entry Exit Registration System (NSEERS) launched following 9/11 resulted in illegal racialized profiling, surveillance and detention of Arab and South Asian immigrants. Cainkar & Maira (2005) described this selective criminalization of Arabs and South Asians as exclusions from cultural citizenship, regardless of actual citizenship (Cainkar & Maira, 2005). These efforts imply certain individuals are more or less worthy of belonging and negate citizenship in the name of state security.

Economic Exploitation and Disinvestment

Contemporary arguments against immigration tend to focus on economic impacts rather than racialized ones (Hirschman, 2005), with economic downturns associated with increases in anti-immigrant sentiment (Goldstein & Peters, 2014; Kwak & Wallace, 2018). For example, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 banned immigration of Chinese laborers because of the perceived competition for jobs; however, it is also the only law ever passed to prevent a specific racial/ethnic group from entering the country. More recently, former President Trump’s “America First” program increased immigration restrictions in the name of protecting American workers and industries. In reality, many immigrants work menial jobs and live in impoverished conditions. While Asian immigrants are perceived as economically successful, there is a bimodal income distribution with many low-income Asian immigrants experiencing similar patterns of disparity as other immigrants groups (Yi et al., 2016). Thus, racialized immigrant groups face similar challenges around low education and literacy levels; low wage work and/or work without benefits; lack of support for stable employment; impoverished neighborhoods and housing; limited English proficiency and linguistic isolation; and lack of access to protective health resources and social services (Shields & Behrman, 2004; Gee & Ford, 2011; Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012). These relationships are bidirectional, as structural racism engenders economic disadvantage, which then perpetuates structural racism. These experiences are also intergenerational; for example, compared to children of U.S.-born parents, children of immigrants are more likely to live in poverty and experience increased exposure to detrimental social determinants of health (Linton, Choi, & Mendoza, 2016). Across immigrants groups, there is insufficient consideration for the structural ways in which racialized immigration policy and enforcement suppress socioeconomic gains by directly shaping access to these economic resources and opportunities. Here we focus on two exemplars that best illustrate these points for immigrant health: labor exploitation and neighborhood disinvestment.

One of the most significant aspects of economic disinvestment for immigrants is unfair labor practices including precarious labor and labor exploitation. The threats of immigration enforcement for undocumented and documented workers can both lead to violation of labor rights and curtail worker’s rights to organize. Undocumented workers, who are often in low wage jobs that pay below minimum wage, may experience wage theft with no legal recourse for recompense, unsafe labor practices, and workplace injuries due to lack of labor protections (Castañeda et al., 2015; Fleming et al., 2019). Documented immigrants on work-sponsored visas may also experience exploitation and overwork due to lack of power and risk of retaliation, which would jeopardize not only their employment but also their residency in the country. Additionally, many immigrant workers do so to provide monetary remittances to countries of origin, which can further constrain resources for health (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2012), with more hostile policies proposing “double” taxes on these remittances (Ratha, De, & Schuettler, 2017). Among immigrant groups with higher levels of success, racialization contributes to on-going feelings of precariousness and insecurity (Shams, 2020), and challenges remain in terms of equal pay, promotions, and upward mobility (Yi et al., 2016).

Like other low-income communities of color, immigrants are more likely to experience worse neighborhood safety and poor housing quality (Castañeda et al., 2015). Over a quarter of Asian Americans reported experiences of housing discrimination (McMurtry et al., 2019), which have been linked with worse health (Gee, 2002). One study also found Arab Americans experience rental discrimination based solely on their names (Carpusor & Loges, 2006). Black people tend to live in more segregated communities than Asian and Latinx people due to structural racism (i.e., ‘minority ghetto’) rather than the formation of ‘ethnic enclaves’ (i.e. living in a community with a high percentage of residents from the same racial or ethnic group). However, a distinction can made between the ‘immigrant enclave’ with some root in racial discrimination and the ‘ethnic community’ where individuals of a particular ethnic group choose to reside despite having more economic resources (Logan, 2002). This has contributed to mixed findings about the potential health-harming or health-promoting benefits of living in ethnic enclaves (Bécares et al., 2012). While these enclaves can offer beneficial social support such as increased family ties, familiar culture and help in finding work, they often coincide with disinvested neighborhoods that experience a concentration of poverty, lack of resources, and exposure to environmental risk factors that negatively impact health (Logan, 2002). The literature is also mixed because health in these communities can differ due to different endemic rates of disease in countries of origin and the retention of healthy and unhealthy behaviors from those countries.

Implications and Recommendations for Future Research

Immigration has been historically and contemporarily racialized in the United States. Critical race theory reminds us to keep race and racism at the forefront of health equity research and practice in the United States by centering those at the margins and paying attention to both historical and contemporary dynamics to identify the root causes that impact health. Intersectionality helps us articulate the unique social position of racialized immigrants. Thus, we apply the framework of structural racism to contextualize how larger sociopolitical forces including immigration policy and disproportionate enforcement can directly and indirectly impact the health of racialized immigrants by influencing who is allowed to enter and stay in the United States and their stratified status in society, the ways in which access to resources are limited or promoted, and the associated economic consequences. While we can learn from prior research knowledge and methods that originated in studying Black versus White disparities, we must also expand it to incorporate novel aspects for immigrants that might warrant further investigation and innovation such as citizenship privileges, language justice, and heterogeneity of diverse subgroups. We hope this paper will 1) serve as a call to action to change the dominant narratives around immigrant health that focus primarily on generational status, years in the United States, and acculturation processes without addressing racialization and “othering”; 2) suggest conceptual and methodological advances to research on health inequities by considering the structural racialization of immigrants via immigration policy and disproportionate enforcement in producing disadvantage and harming health; and 3) illuminate the essential role of the public health sector to advocate for changes in other sectors including immigration policy, political rights, law enforcement, labor protections, neighborhood investment, and housing quality, amongst others.

We recommend a reprioritization of health research by the academic and government sectors at large, and of funding by public and private institutions, to consider the simultaneous effects of racialization and immigration on population health and health inequities, including intersections with other racialized domains such as Islamophobia. This will also require reconceptualizing who experiences health inequities. While Latino immigrants are more commonly acknowledged as experiencing inequities, they are also more often blamed for them due to their presumed illegal status (Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012). For Asian immigrants, this will entail dispelling the ‘model minority myth’ that they do not experience disadvantage (Yi et al., 2016) and racial discrimination (as made apparent most recently during the COVID-19 pandemic; Chen, Zhang, & Liu, 2020; Misra et al., 2020). For Arabs immigrants, it will require classification as a racialized minority group in data collection to ascertain inequities (Abboud et al., 2019; Abuelezam, El-Sayed, & Galea, 2017). Across all three groups, it also requires consideration of the immense within-group heterogeneity including differing sociopolitical histories, cultures, religions, and languages. We also emphasize the need for immigrant research will not diminish with time. While seemingly a specialized population, one in four children in the United States lives in a family with at least one immigrant parent and 75% of the population growth amongst children ages 0 to 8 years has been among Latino and Asian communities (Javier et al., 2015). Practically, this means studies should not focus solely on race/ethnicity or nativity but also consider citizenship and belonging (Asad & Clair, 2018; Gee & Ford, 2011), including spillover effects for those in mixed status households or perceived as immigrants.

Due to exclusion from political and civic processes, immigrant communities are not accurately represented when setting research priorities and funding allocations, including within the research workforce (Santiago & Miranda, 2014). In other words, immigrants are excluded from participating in the very systems that determine who gets studied and why. Research agendas need to both prioritize better recruitment of immigrants and reduce barriers to participating (e.g., language, trust, compensation) (Liu et al., 2019). For example, in the last two decades, only 0.17% of the NIH budget was dedicated to clinical research projects focused on Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander participants (includes non-immigrant groups; Doàn et al., 2019). A common challenge is the exclusion of non-English speakers (Brodeur et al., 2017). The structural racism framework helps illuminate how the lack of adequate healthcare provisions for limited English proficient speakers (over 25 million people), which is another right under threat by hostile immigration policies (Chin, 2019), contributes to this problem. Similarly, the framework indicates the importance of building trust due to threats to safety related to immigration enforcement, especially if participation feels like another form of surveillance. Economic challenges and segregation could also deter participation but innovative strategies for appropriate compensation and community outreach could help counter this (Liu et al., 2019).

So far, research on how immigrant policy and disproportionate enforcement influence health have primarily focused on undocumented Latino immigrants and considered the impacts on healthcare access and mental health, particularly for woman and children (Castañeda et al., 2015; Martinez et al., 2015; Perreira & Pedroza, 2019; Philbin et al., 2018). This should be expanded to other immigrant groups including Asian and Arab immigrants; other temporary citizenship statuses in addition to undocumented and mixed households; men and older adults, and other outcomes including healthcare quality and physical health. Wallace and colleagues propose a framework to capture the policy climate for immigrant health: 1) public health and welfare benefits; 2) higher education; 3) labor and employment policies; 4) driver’s licenses and identification systems, and 5) immigration enforcement (Wallace et al., 2019) and Perreira and Pedroza summarize innovative methods used to assess the impact of policies on immigrant health (Perreira & Pedroza, 2019). Neighborhood research must take a multi-pronged approach that pairs administrative data with more nuanced information on the composition and community norms of a neighborhood. For example, studies among immigrant communities must take into consideration endemic rates of disease in countries of origin and not only consider cross-sectional views of disease prevalence. They also need to move beyond definitions based solely on geographic boundaries to consider how immigrant neighborhoods define and perceive themselves. Future studies can also investigate the proposed mechanisms by which racialized policies and practices impact immigrant health including psychosocial aspects such as fear, stress, and trauma; differential access to material resources including food, employment, and housing; differential access to healthcare including healthcare literacy and healthcare quality; experiences of social exclusion and community disruption; actual or anticipated experiences of discrimination, neglect, violence, and abuse (Cabral & Cuevas, 2020; Fleming et al., 2019; Lee, Rhee, Kim, & Ahluwalia, 2015; Philbin et al., 2018; Saadi et al., 2020); and the long-term and dynamic impacts across the life course (Torres & Young, 2016).

Since structural racism affects all racialized immigrant groups, this suggests interventions can also be designed to leverage these commonalities rather than exclusively focusing on the cultural needs of specific immigrant groups. This approach can be accelerated by the growing interest in the principles of implementation science – that can provide structure to enumerating “what works, for whom and why” (Damschroder et al., 2009; Lobb & Colditz, 2013). We underscore the merits in culturally-specific interventions, targeted and tailored towards reaching racial/ethnic subgroups, but note this has created a segmented approach to addressing, understanding and studying health inequities for racialized groups. Alignment across studies is lacking, which limits the sustainability, efficiency, and utility of immigrant health research in the long run. A wider lens focused on the impacts of structural racism on immigrant health more broadly will not only allow programs to address the limited generalizability that race/ethnic-specific work may bring but also acknowledges the co-ethnic neighborhoods in which immigrants often live and the similar resources they access in these communities. Ultimately, these approaches that integrate across populations indicate the need for both large and small scale structural solutions and more systematic mindfulness on the part of researchers, health practitioners, and policymakers to transform the racialization of immigrants embedded into current policies and practices and re-imagine how societies can treat all residents equitably including via shared resources and economic gains.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (grant number U54MD000538); the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (grant number UL1TR001445l); the NIH National Cancer Institute (grant number P30CA016087); and the NIH National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grant number P30ES000260).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abboud S, Chebli P, & Rabelais E (2019). The contested whiteness of Arab identity in the United States: Implications for health disparities research. American Journal of Public Health, 109(11), 1580–1583. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraído-Lanza AF, Echeverría SE, & Flórez KR (2016). Latino Immigrants, Acculturation, and Health: Promising New Directions in Research. Annual Review of Public Health, 37, 219–236. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuelezam NN, El-Sayed AM, & Galea S (2017). Arab American Health in a Racially Charged U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52(6), 810–812. 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abuelezam NN, El-Sayed AM, & Galea S (2018). The Health of Arab Americans in the United States: An Updated Comprehensive Literature Review. Frontiers in Public Health, 6(September), 1–18. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Sanchez-Vaznaugh EV, Viruell-Fuentes EA, & Almeida J (2012). Integrating social epidemiology into immigrant health research: A cross-national framework. Social Science and Medicine, 75(12), 2060–2068. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara C, Estevez CD, & Alegría M (2017). Latino and Asian immigrant adult health: Paradoxes and explanations. In Schwartz JB, Unger SJ (Ed.), Oxford Library of Psychology. The Oxford Handbook of Acculturation and Health (pp. 197–220). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade N, Ford AD, & Alvarez C (2020). Discrimination and Latino Health: A Systematic Review of Risk and Resilience. Hispanic Health Care International. 10.1177/1540415320921489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenta A (2017). Racializing Crimmigration. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 3(1), 82–95. 10.1177/2332649216648714 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asad AL, & Clair M (2018). Racialized legal status as a social determinant of health. Social Science and Medicine, 199, 19–28. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalew B, Dawson-Hahn E, Cholera R, Falusi O, Haro TM, Montoya-Williams D, & Linton JM (2021). The health of children in immigrant families: Key drivers and research gaps through an equity lens. Academic Pediatrics. 10.1016/j.acap.2021.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, & Bassett MT (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. The Lancet, 389(10077), 1453–1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bécares L, Shaw R, Nazroo J, Stafford M, Albor C, Atkin K, … Pickett K (2012). Ethnic density effects on physical morbidity, mortality, and health behaviors: A systematic review of the literature. American Journal of Public Health, 102(12). 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur M, Herrick J, Guardioloa J, & Richman P (2017). Exclusion of non-English speakers in published emergency medicine research - A comparison of 2004 and 2014. Acta Informatica Medica, 25(2), 112–115. 10.5455/aim.2017.25.112-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budiman A (2020, August 20). Key findings about U.S. immigrants. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/

- Cabral J, & Cuevas AG (2020). Health Inequities Among Latinos/Hispanics: Documentation Status as a Determinant of Health. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 7(5), 874–879. 10.1007/s40615-020-00710-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cainkar L, & Maira S (2005). Targeting Arab/Muslim/ South Asian Americans: Criminalization and cultural citizenship. Amerasia Journal, 31(3), 1–27. 10.17953/amer.31.3.9914804357124877 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpusor AG, & Loges WE (2006). Rental discrimination and ethnicity in names. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(4), 934–952. 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00050.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT, Johnson VE, Kirkinis K, Roberson K, Muchow C, & Galgay C (2019). A Meta-Analytic Review of Racial Discrimination: Relationships to Health and Culture. Race and Social Problems, 11(1), 15–32. 10.1007/s12552-018-9256-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda H, Holmes SM, Madrigal DS, Young MEDT, Beyeler N, & Quesada J (2015). Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 36, 375–392. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JA, Zhang E, & Liu CH (2020). Potential Impact of COVID-19-Related Racial Discrimination on the Health of Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 110(11), 1624–1627. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin KK (2019, August 9). Language Access Rights Under Threat. Health Affairs Blog. 10.1377/hblog20190809.457959 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, & Lowery JC (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice : a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science, 15, 1–15. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doàn LN, Takata Y, Sakuma KLK, & Irvin VL (2019). Trends in Clinical Research Including Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Participants Funded by the US National Institutes of Health, 1992 to 2018. JAMA Network Open, 2(7), 1–16. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling MG, Bleich SN, Casey LS, Blendon RJ, Benson JM, Sayde JM, & Miller C (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of Latinos. Health Services Research, 54(S2), 1409–1418. 10.1111/1475-6773.13216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming PJ, Novak NL, & Lopez WD (2019). U.S. Immigration Law Enforcement Practices and Health Inequities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 57(6), 858–861. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CL, & Airhihenbuwa CO (2010). Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: toward antiracism praxis. American Journal of Public Health, 100(S1), S30–S35. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.171058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC (2002). A multilevel analysis of the relationship between institutional and individual racial discrimination and health status. American Journal of Public Health, 92(4), 615–623. 10.2105/AJPH.92.4.615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, & Ford CL (2011). Structural racism and health inequities: Old Issues, New Directions. Du Bois Review, 8(1), 115–132. 10.1017/S1742058X11000130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ro A, Shariff-Marco S, & Chae D (2009). Racial Discrimination and Health Among Asian Americans: Evidence, Assessment, and Directions for Future Research. Epidemiologic Reviews, 31, 130–151. 10.1093/epirev/mxp009.Racial [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JL, & Peters ME (2014). Nativism or economic threat: Attitudes toward immigrants during the great recession. International Interactions, 40(3), 376–401. 10.1080/03050629.2014.899219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy LJ, Getrich CM, Quezada JC, Guay A, Michalowski RJ, & Henley E (2012). A call for further research on the impact of state-level immigration policies on public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1250–1254. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Prins SJ, Flake M, Philbin M, Frazer MS, Hagen D, & Hirsch J (2017). Immigration policies and mental health morbidity among Latinos: A state-level analysis. Social Science and Medicine, 174, 169–178. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicken MT, Kravitz-Wirtz N, Durkee M, & Jackson JS (2018). Racial inequalities in health: Framing future research. Social Science and Medicine, 199, 11–18. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman C (2005). Immigration and the American Century. Demography, 42(4), 595–620. 10.1353/dem.2005.0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh QL, Devos T, & Smalarz L (2011). Perpetual foreigner in one’s own land: Potential implications for identity and psychological adjustment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(2), 133–162. 10.1521/jscp.2011.30.2.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javier JR, Festa N, Florendo E, & Mendoza FS (2015). Children in Immigrant Families: The Foundation for America’s Future. Advances in Pediatrics, 62(1), 105–136. 10.1016/j.yapd.2015.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N (2000). Refiguring “race”: Epidemiology, racialized biology, and biological expressions of race relations. International Journal of Health Services, 30(1), 211–216. 10.2190/672J-1PPF-K6QT-9N7U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak J, & Wallace M (2018). The Impact of the Great Recession on Perceived Immigrant Threat: A Cross-National Study of 22 Countries. Societies, 8(3), 52. 10.3390/soc8030052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Rhee TG, Kim NK, & Ahluwalia JS (2015). Health Literacy as a Social Determinant of Health in Asian American Immigrants: Findings from a Population-Based Survey in California. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(8), 1118–1124. 10.1007/s11606-015-3217-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton JM, Choi R, & Mendoza F (2016). Caring for children in immigrant families: vulnerabilities, resilience, and opportunities. Pediatric Clinics, 63(1), 115–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Elliott A, Strelnick H, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, & Cottler LB (2019). Asian Americans are less willing than other racial groups to participate in health research. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, 3(2–3), 90–96. 10.1017/cts.2019.372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobb R, & Colditz GA (2013). Implementation Science and Its Application to Population Health. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Logan JR, Alba RD, & Zhang W (2002). Immigrant enclaves and ethnic communities in New York and Los Angeles. American Sociological Review, 67(2), 299–322. 10.2307/3088897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovato K, Lopez C, Karimli L, & Abrams LS (2018). The impact of deportation-related family separations on the well-being of Latinx children and youth: A review of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review, 95(October), 109–116. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.10.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez O, Wu E, Sandfort T, Dodge B, Carballo-Dieguez A, Pinto R, … Chavez-Baray S (2015). Evaluating the Impact of Immigration Policies on Health Status Among Undocumented Immigrants: A Systematic Review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17(3), 947–970. 10.1007/s10903-013-9968-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurtry CL, Findling MG, Casey LS, Blendon RJ, Benson JM, Sayde JM, & Miller C (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of Asian Americans. Health Services Research, 54(S2), 1419–1430. 10.1111/1475-6773.13225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra S, Le PTD, Goldmann E, & Yang LH (2020). Psychological Impact of Anti-Asian Stigma Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Call for Research, Practice, and Policy Responses. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 10.1037/tra0000821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey BN (2018). Mechanisms by which anti-immigrant stigma exacerbates racial/ethnic health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 108(4), 460–463. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols VC, Lebrón AMW, & Pedraza FI (2018). Policing Us Sick: The Health of Latinos in an Era of Heightened Deportations and Racialized Policing. PS - Political Science and Politics, 51(2), 293–297. 10.1017/S1049096517002384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson HL (2019). Associations Between Major and Everyday Discrimination and Self-Rated Health Among US Asians and Asian Americans. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 10.1007/s40615-019-00654-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NYC Planning. (2017). NYC’s Foreign-born, 2000 to 2015. New York NY. [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, … Gee G (2015). Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 10(9), 1–48. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, & Pedroza JM (2019). Policies of Exclusion: Implications for the Health of Immigrants and Their Children. Annual Review of Public Health, 40, 147–166. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, & Link BG (2015). Is Racism a Fundamental Cause of Inequalities in Health? Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 311–330. 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Philbin MM, Flake M, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Hirsch JS (2018). State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Social Science and Medicine, 199, 29–38. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratha D, De S, & Schuettler K (2017, March 24). Why taxing remittances is a bad idea. World Bank Blogs. Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/peoplemove/why-taxing-remittances-bad-idea

- Rollock N, & Gillborn D (2011) Critical Race Theory (CRT), British Educational Research Association on line resource. Available online at [http://www.bera.ac.uk/files/2011/10/Critical-Race-Theory.pdf] Last accessed February 15, 2021.

- Saadi A, De Trinidad Young M-E, Patler C, Leonel Estrada J, & Venters H (2020). Understanding US Immigration Detention: Reaffirming Rights and Addressing Social-Structural Determinants of Health. Health & Human Rights: An International Journal, 22(1), 187–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz R, & Douglas KM (2015). A Call for the Racialization of Immigration Studies : On the Transition of Ethnic Immigrants to Racialized Immigrants. 10.1177/2332649214559287 [DOI]

- Samari G, Alcalá HE, & Sharif MZ (2018). Islamophobia, health, and public health: A systematic literature review. American Journal of Public Health, 108(6), e1–e9. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago CD, & Miranda J (2014). Progress in improving mental health services for racial-ethnic minority groups: A ten-year perspective. Psychiatric Services, 65(2), 180–185. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahshahani A (2020, October 14). The Trump Administration is Using an Under-the-Radar Tactic to Suppress Votes. Time. [Google Scholar]

- Shams T (2020). Successful yet Precarious: South Asian Muslim Americans, Islamophobia, and the Model Minority Myth. Sociological Perspectives, 63(4), 653–669. 10.1177/0731121419895006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shields MK, & Behrman RE (2004). Children of immigrant families: Analysis and recommendations. Future of Children, 14(2), 4–15. 10.2307/1602791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CJ (2020). Health Consequences of Laws and Public Policies That Target, or Protect, Marginalized Populations. Sociology Compass, 14(2), 1–13. 10.1111/soc4.12753 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torres JM, & Young MED (2016). A life-course perspective on legal status stratification and health. SSM - Population Health, 2, 141–148. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venters H, & Gany F (2011). African immigrant health. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 13(2), 333–344. 10.1007/s10903-009-9243-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, & Abdulrahim S (2012). More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Social Science and Medicine, 75(12), 2099–2106. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Werthern M, Robjant K, Chui Z, Schon R, Ottisova L, Mason C, & Katona C (2018). The impact of immigration detention on mental health: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 1–19. 10.1186/s12888-018-1945-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace SP, Young MEDT, Rodríguez MA, & Brindis CD (2019). A social determinants framework identifying state-level immigrant policies and their influence on health. SSM - Population Health, 7(October 2018), 100316. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Cooper LA (2019). Reducing racial inequities in health: Using what we already know to take action. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(4). 10.3390/ijerph16040606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Lawrence JA, & Davis BA (2019). Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annual Review of Public Health, 40(1), 1–21. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Mohammed SA (2013). Racism and Health I: Pathways and Scientific Evidence. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(8), 1152–1173. 10.1177/0002764213487340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimer C, Maury M, & Bahl V (2018). Public Charge: How a New Policy Could Affect Poverty in New York City.

- Wray-Lake L, Syvertsen AK, & Flanagan CA (2008). Contested citizenship and social exclusion: Adolescent Arab American immigrants’ views of the social contract. Applied Developmental Science, 12(2), 84–92. 10.1080/10888690801997085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yi SS, Kwon SC, Sacks R, & Trinh-Shevrin C (2016). Commentary: Persistence and health-related consequences of the model minority stereotype for Asian Americans. Ethnicity and Disease, 26(1), 133–138. 10.18865/ed.26.1.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MEDT, Leon-Perez G, Wells CR, & Wallace SP (2019). Inclusive state immigrant policies and health insurance among Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, Black, and White noncitizens in the United States. Ethnicity and Health, 24(8), 960–972. 10.1080/13557858.2017.1390074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]