Abstract

Hibernation is a mammalian strategy that uses metabolic plasticity to reduce energy demands and enable long-term fasting. Fasting mitigates winter food scarcity but eliminates dietary nitrogen, jeopardizing body protein balance. Here, we reveal gut microbiome-mediated urea nitrogen recycling in hibernating thirteen-lined ground squirrels (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus). Ureolytic gut microbes incorporate urea nitrogen into metabolites that are absorbed by the host, with the nitrogen reincorporated into the squirrel’s protein pool. Urea nitrogen recycling is greatest after prolonged fasting in late winter, when urea transporter abundance in gut tissue and urease gene abundance in the microbiome are highest. These results reveal a functional role for the gut microbiome during hibernation and suggest mechanisms by which urea nitrogen recycling may contribute to protein balance in other monogastric animals.

Hibernation is an adaptation to seasonal food scarcity. The hallmark of hibernation is torpor, a metabolic state that reduces rates of fuel use by up to 99% relative to active season rates. Torpor enables seasonal hibernators such as the thirteen-lined ground squirrel (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus) to fast for the ~6-month hibernation season, solving the problem of winter food scarcity; however, fasting deprives the squirrel of dietary nitrogen, thus jeopardizing protein balance.

Despite dietary nitrogen deficiency and prolonged inactivity, hibernators lose little muscle mass and function during winter (1). Moreover, late in hibernation, squirrels elevate muscle protein synthesis rates to active season levels (2). It is unknown how hibernators preserve tissue protein during hibernation, but one hypothesis is that they harness the ureolytic capacities of their gut microbes to recycle urea nitrogen back into their protein pools (3). This process, termed urea nitrogen salvage, is present in ruminants and at least some nonruminant animals (4), but there is minimal evidence of its use by mammalian hibernators (5).

We hypothesized that squirrels use this mechanism to recoup urea nitrogen to facilitate tissue protein synthesis during, and particularly late in, hibernation (Fig. 1A). We tested this hypothesis with three seasonal squirrel groups: summer (active), early winter (1 month of hibernation and fasting), and late winter (3 to 4 months of hibernation and fasting) squirrels. Early and late winter squirrels were studied during induced interbout arousals at euthermic metabolic rates and body temperatures. Each seasonal group contained squirrels with intact and antibiotic-depleted gut microbiomes. For each group, we administered two intraperitoneal injections of 13C,15N-urea (~7 days apart depending on season, with unlabeled urea used as the control; fig. S1 and table S2). We then examined the critical steps of urea nitrogen salvage (Fig. 1).

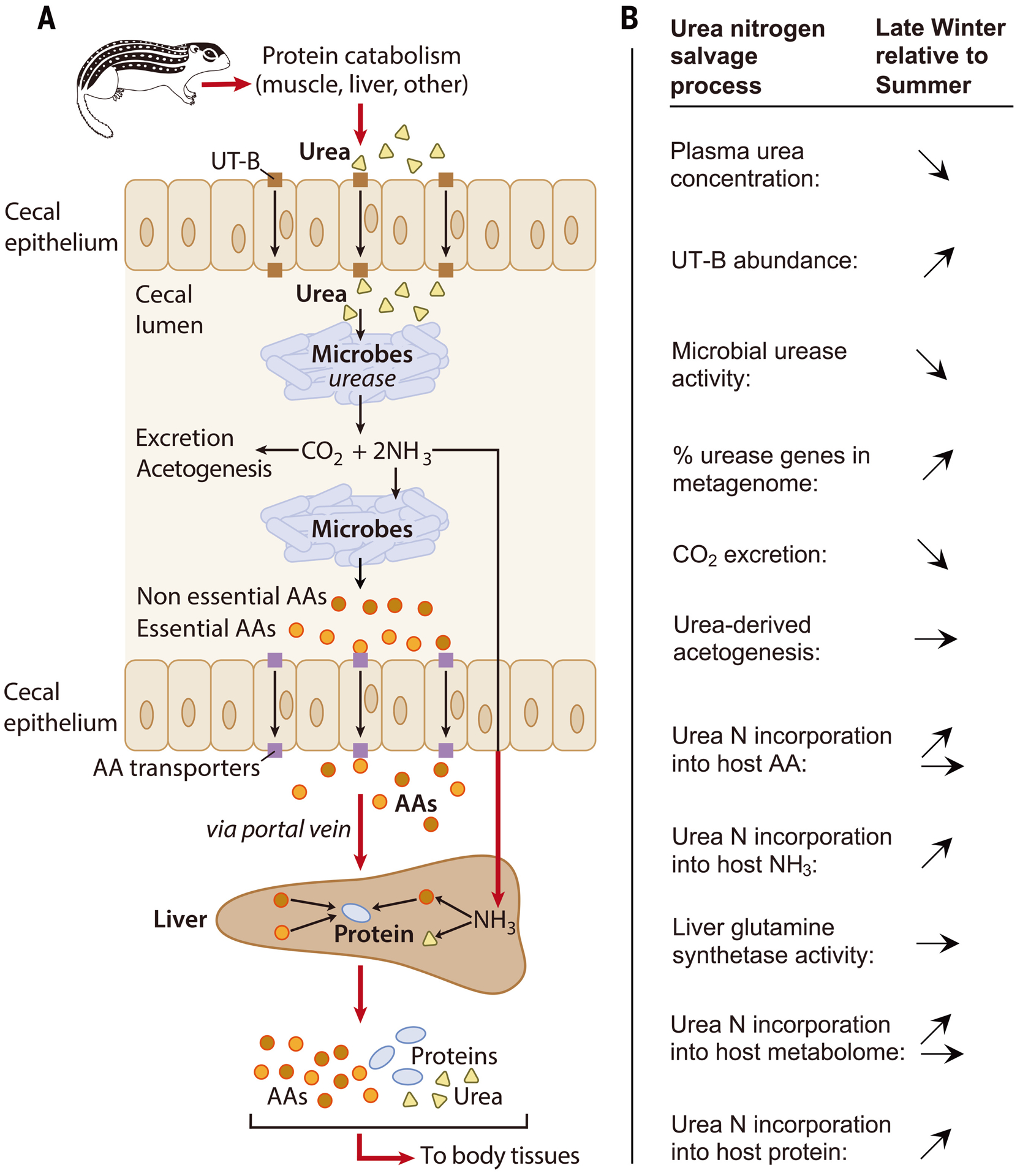

Fig. 1. Proposed mechanism for urea nitrogen salvage and relative changes during hibernation.

(A) Urea (yellow triangles), endogenously produced by the liver, is transported by epithelial urea transporters (UT-B; brown squares) from blood into the cecal lumen where it is hydrolyzed into CO2 and NH3 by urease-expressing gut microbes. CO2 is excreted by the host and/or fixed by microbes. NH3 is absorbed by the host and converted into amino acids (AAs) and/or urea in the liver, or used by microbes to synthesize AAs (circles) which are incorporated into the microbial proteome or potentially absorbed by the host through ceco-colonic amino acid transporters (purple squares) (11). Ultimately, the AAs are used to synthesize protein (blue ovals) in host tissues, recycling the urea nitrogen. (B) Arrows indicate how processes change (increase, decrease, no change) in winter versus summer as revealed by this study. All changes are based on statistically significant results except for percentage of urease genes in the metagenome (P = 0.083).

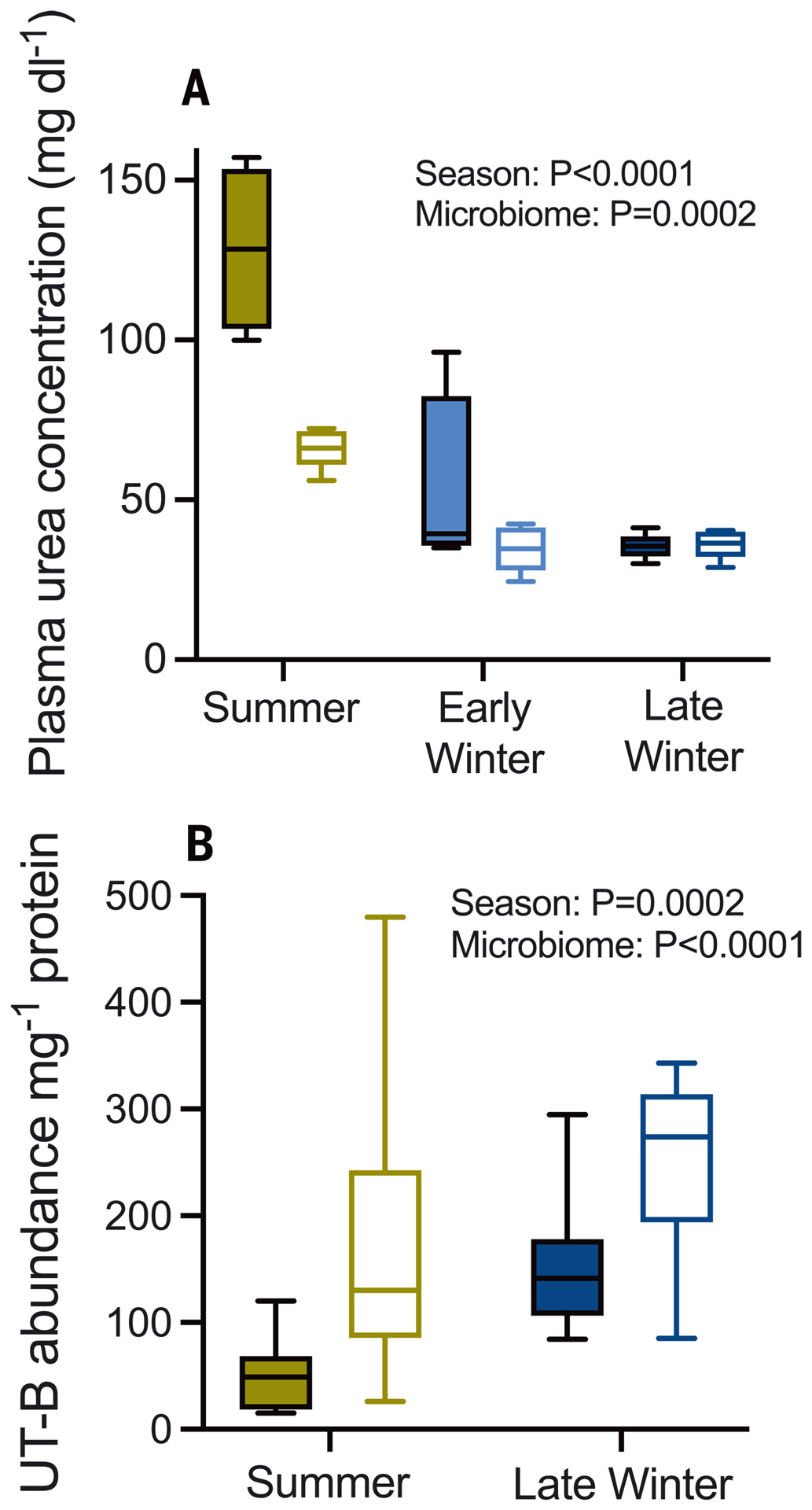

This process begins with hepatic urea synthesis and transport into the blood. Urea that is not excreted by the kidneys can be transported into the gut lumen through epithelial urea transporters (UT-Bs) (6) where, in the presence of ureolytic microbes, it is hydrolyzed into ammonia and CO2. Plasma urea concentrations in early and late winter squirrels were lower than those in summer squirrels (Fig. 2A), as observed previously (7) (fig. S2). However, UT-B abundance in the ceca of squirrels untreated with urea was about three times as high in late winter squirrels relative to summer squirrels (Fig. 2B), suggesting that lower plasma urea concentrations in winter may be partially offset through enhanced capacity for urea transport into the gut. Although this must be verified by future UT-B inhibition experiments, the observations that microbiome depletion increases UT-B expression (Fig. 2B), lowers plasma urea (Fig. 2A), and increases luminal urea concentrations (fig. S3) in summer squirrels support a role for UT-B in urea nitrogen salvage during the hibernation season. The mechanism underlying greater UT-B abundance in late winter squirrels and microbiome-depleted summer squirrels may involve luminal ammonia, which inhibits UT-B expression in ruminants (8). Commensurate with this, luminal ammonia levels were lower during hibernation in late winter squirrels than in summer squirrels (9) (fig. S4A) and in microbiome-depleted relative to microbiome-intact squirrels (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 2. Plasma urea concentration and cecal urea transporter (UT-B) expression.

(A) Plasma urea concentration in urea-treated squirrels with intact (filled bars) and depleted (open bars) gut microbiomes (n = 4 to 5 animals). (B) UT-B protein abundance per milligram of cecal protein in cecum tissue (n = 12; immunoblots in fig. S8). A subset of non-urea-treated squirrels was used that lacked the early winter group. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) results are shown in each panel.

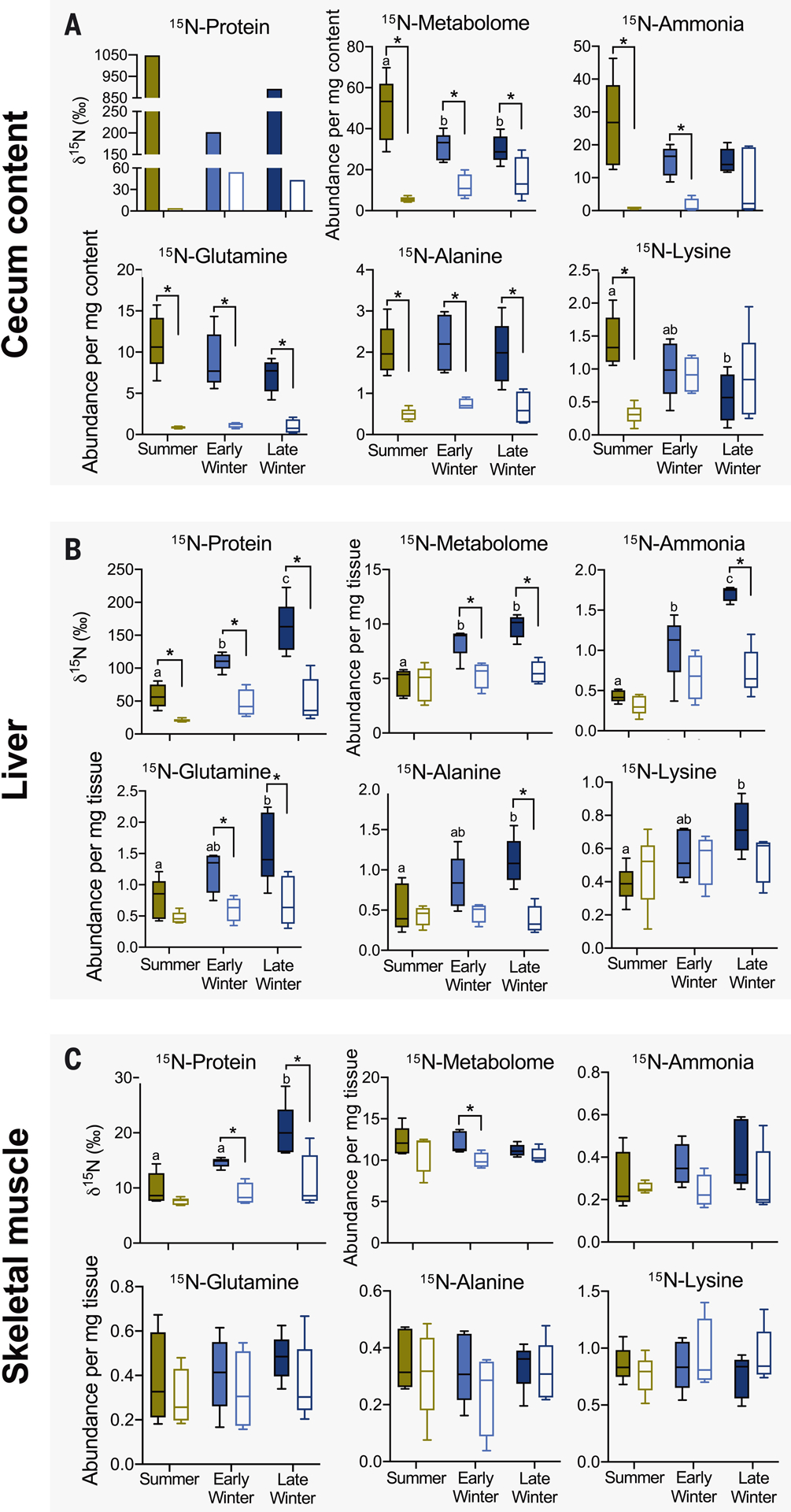

Fig. 4. 15N-urea nitrogen incorporation into metabolite and protein pools of gut microbiome and host tissues.

(A) Cecal content, (B) liver, and (C) muscle (quadriceps) of microbiome-intact (filled bars) and microbiome-depleted (open bars) squirrels. For each panel, 15N-Protein portrays 15N-incorporation into protein, 15N-Metabolome portrays 15N-incorporation into the total pool of metabolites (identifiable and nonidentifiable), and the remaining plots portray 15N-incorporation into the metabolite named above the plot. Metabolomic data are relative abundances in arbitrary units. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between microbiome groups within a season, and different lowercase letters indicate significant seasonal difference among microbiome-intact groups. See tables S1 and S2 for statistical results, n = 5 for all data, except for early winter microbiome depleted (n = 4) and cecum content 15N-protein [n = 1 (pooled samples)].

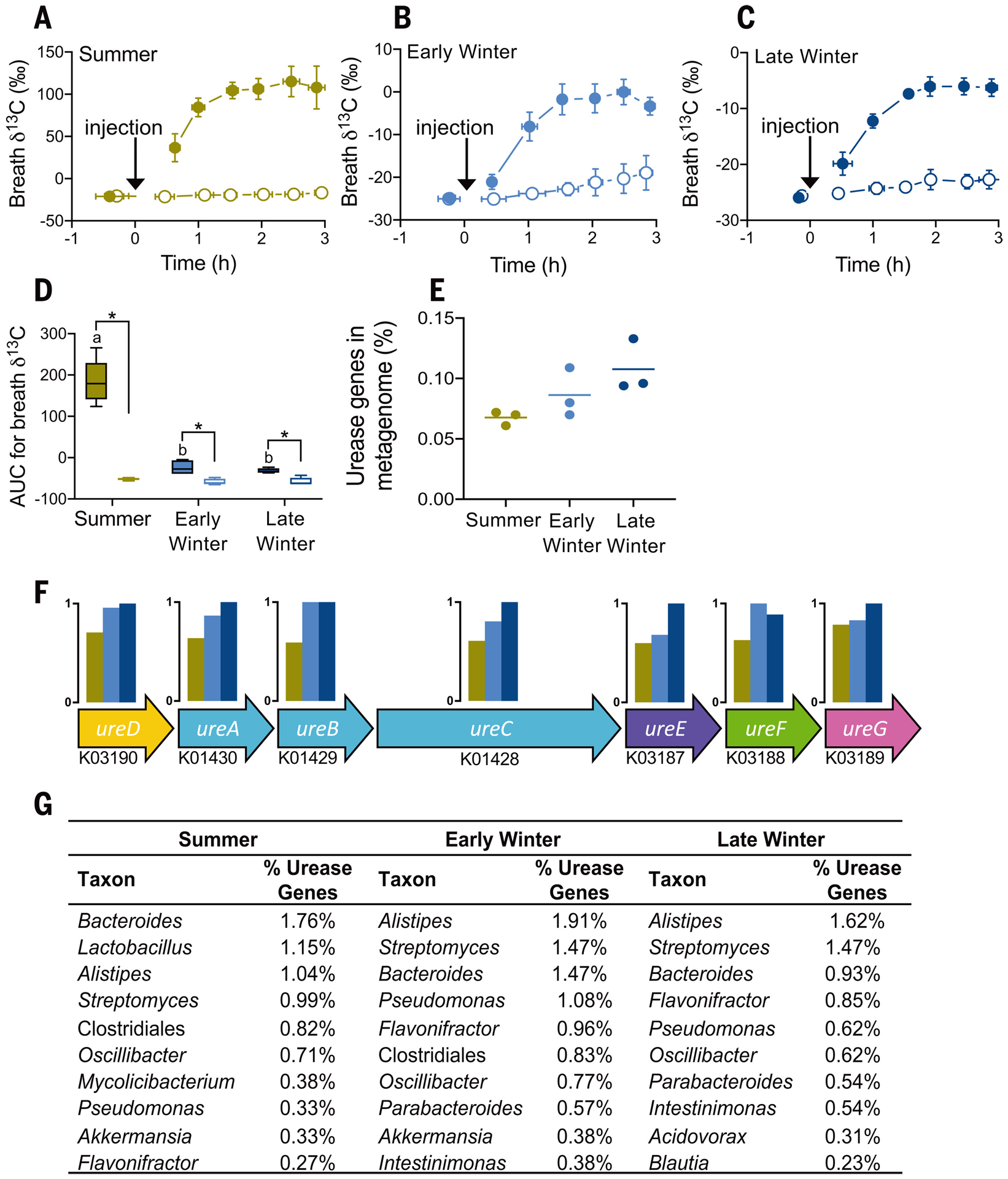

Next, we measured microbial ureolytic activity in vivo using stable isotope breath analysis where, because vertebrates lack urease, elevated 13CO2:12CO2 (δ13C) after injection of 13C,15N-urea indicates microbial ureolysis. Breath δ13C increased after 13C,15N-urea injection (Fig. 3, A to C) in microbiome-intact—but not microbiome-depleted—squirrels (Fig. 3D), thus confirming microbial ureolytic activity. Ureolysis was greatest in summer squirrels (Fig. 3D and fig. S4B), consistent with greater bacterial abundance in summer versus hibernating squirrels (fig. S5). Nevertheless, microbial ureolysis continued throughout hibernation.

Fig. 3. Gut microbial ureolysis and metagenome.

Mean breath δ13C for (A) summer, (B) early winter, and (C) late winter squirrels treated with 13C,15N-urea. Horizontal and vertical error bars represent SEM, and closed and open symbols represent squirrels with intact and depleted microbiomes, respectively. The arrows indicate intraperitoneal 13C,15N-urea injection. (D) Mean area-under-the-curve (AUC) values for data in (A) to (C), where asterisks indicate significant differences between microbiome groups within a season, and lowercase letters indicate significant seasonal differences among microbiome-intact groups [n = 5, (A) to (D); n = 4 for early winter microbiome-depleted animals]. Seasonal effect on (E) the percentage of urease genes in the bacterial metagenome, (F) urease operons including each gene’s Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes ontology identifier and seasonal relative abundance, and (G) the top 10 bacterial taxa from taxonomic classification of urease genes as determined by sequence abundance.

The metagenomes of hibernating squirrels trended toward higher percentages of urease genes than those of summer squirrels (Fig. 3E) across the seven urease-related genes (Fig. 3F). This suggests that during hibernation, a higher percentage of microbes have the potential to hydrolyze urea. Indeed, Alistipes—the bacterial genus with the greatest detectable genomic representation of urease genes in early and late winter squirrels (Fig. 3G)—is predominant during hibernation, with a six-fold population increase between the summer and late winter groups (9).

To benefit the host, microbial ureolytic activity would need to provide nitrogenous compounds such as amino acids and/or ammonia. Using two-dimensional 1H-15N NMR spectroscopy, we found that more 15N was incorporated into the cecal content and liver metabolomes of microbiome-intact compared with microbiome-depleted squirrels (Fig. 4, A and B), a trend that—with a few exceptions—also held for specific metabolites such as ammonia, glutamine, and alanine (Fig. 4, A and B). 15N-metabolite levels also varied seasonally. In cecum contents, early and late winter metabolite levels were generally lower than summer levels, whereas in the liver, early and late winter metabolite levels were generally higher than summer levels and were typically highest in the late winter group (Fig. 4, A and B). For muscle, metabolite 15N incorporation was generally unaffected by the presence of a microbiome (Fig. 4C), which could be due to the timing of our 13C,15N-urea dosing and tissue sampling protocols. When tissues were sampled, the 15N-amino acids from the initial 13C,15N-urea dose may have already been incorporated into muscle protein, thus explaining the microbiome-dependent 15N-protein results (Fig. 4C), whereas the 3 hours between the second dose and tissue sampling may have been too brief for 15N-metabolites to appear in muscle. Rather, the muscle 15N-metabolite levels may represent microbiome-independent background 15N levels, which is consistent with the equivalent 15N-metabolite abundances in the muscle of squirrels treated with labeled and unlabeled urea and with intact and depleted microbiomes (table S1).

The ultimate benefit of urea nitrogen salvage is nitrogen incorporation into host protein. Using isotope ratio mass spectrometry, we found that microbiome-intact squirrels incorporated significant 15N into liver and muscle protein, but microbiome-depleted squirrels did not (Fig. 4, B and C), thereby verifying that urea nitrogen salvage is microbe-dependent and benefits the host. Moreover, 15N incorporation into liver and muscle protein was two to three times as high in the late winter group versus the summer group, indicating that urea nitrogen salvage is most beneficial late in the winter fast. We also found large amounts of 15N incorporated into cecal content protein (indicative of microbial protein; Fig. 4A) in microbiome-intact squirrels, indicating nutritional benefits for the gut microbiome. However, unlike in muscles and the liver, microbial protein 15N incorporation was highest in the summer group (Fig. 4A), for which microbial abundance was also highest (fig. S5).

Notably, 15N incorporation into host protein was highest when ureolytic activity was lowest (i.e., late winter; Fig. 3D). This can be explained by our observations at multiple steps (Fig. 1B): First, urea transport capacity into the gut likely increases during hibernation through elevated UT-B abundance (Fig. 2B). Second, the microbiome becomes proportionally (though not absolutely) more ureolytic in winter, evidenced by elevated urease gene percentages (Fig. 3E) and bacterial urease activity levels (fig. S4B) that are higher than those predicted by the breath δ13C changes (Fig. 3D). Another possible contributor is proportionally greater microbial CO2 fixation (e.g., acetogenesis) in winter than in summer (fig. S6), thus reducing the quantity of exhaled 13CO2. Third, higher bacterial death rates in winter (10) could liberate relatively higher amounts of bacterial contents for host absorption during hibernation, including metabolites containing urea nitrogen (Fig. 4A).

Salvaged urea nitrogen can potentially be absorbed by the squirrel as amino acids or ammonia. Though ceco-colonic amino acid absorption occurs in rodents (11), our results suggest that ammonia absorption and its hepatic conversion to glutamine through glutamine synthetase may be the key step that is enhanced during hibernation. For example, tissue abundance of 15N-lysine (an essential amino acid that must be absorbed) was affected only by season and not by microbiome presence. Additionally, numerous lines of evidence support the absorption and hepatic conversion of 15N-ammonia, including elevated liver 15N-ammonia and 15N-glutamine levels in early and late winter (Fig. 4B), sustained liver glutamine synthetase activity during hibernation (fig. S7), and reduced urea cycle enzymes and intermediates (12, 13). This implies that during hibernation, the condensation of ammonia with glutamate to form glutamine is favored over its conversion to urea. Indeed, in protein-deficient rats, hepatic ammonia processing shifts from urea toward glutamine production (14), and in fasting hibernating arctic ground squirrels, ammonia from muscle protein breakdown is directed away from the urea cycle toward amino acid formation (13). Despite this implied shift in ammonia processing, urea production continues during hibernation (albeit at lower rates), with plasma concentrations lowest upon torpor reentry and highest during interbout arousal (fig. S2) (7). Much of this urea is likely transferred to the gut by urea transporters, where it becomes available for microbial ureolysis. Thus, nitrogen recycling in hibernators involves both endogenous (13) and microbe-dependent mechanisms, underscoring the importance of maintaining nitrogen balance during hibernation.

Urea nitrogen salvage provides two major benefits for hibernators: First, it augments protein synthesis when dietary nitrogen is absent and appears especially important late in hibernation, just before the squirrel’s emergence into its breeding season (2, 15). By facilitating protein synthesis and subsequent tissue function, this process may confer reproductive advantages. Second, as in water-deprived camels (16), urea nitrogen salvage may enhance water conservation in water-deprived hibernators by diverting urea away from the kidneys, thus requiring less water for urine production.

Our results provide evidence that the gut microbiome plays a functional role during the hibernation season, building upon earlier results that suggest a possible role for the microbiome in pre-hibernation fattening (17). Our demonstration of monogastric urea nitrogen salvage as a mechanism facilitating protein synthesis under nitrogen limitation has potential implications beyond hibernation. For example, muscle wasting affects hundreds of millions of people globally as a result of nitrogen-limited diets (18) and sarcopenia (19), and there is evidence for humans possessing the necessary machinery for urea nitrogen salvage (20). Understanding the mechanisms by which hibernators maintain protein balance and mitigate muscle wasting under severe nitrogen limitation may inform strategies for muscle preservation in humans.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Steinberg, S. Cailey, W. Porter, S. Martin, and M. T. Grahn for assistance, and the reviewers for insightful comments.

Funding:

Work was supported by NSF Grant IOS-1558044 to H.V.C., F.M.A.-P., and G.S.; NIH Grants P41GM136463, P41GM103399 (NIGMS), and P41RR002301 to the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison; National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH traineeship T32GM008349 and NSF Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-1747503 to E.C.; NSERC Canada Postdoctoral Fellowship to M.D.R.

Footnotes

Competing interests: F.M.A.-P. is the founder of MetResponse, LLC and Isomark Health Inc. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

Metagenomic data are available at NCBI (PRJNA693524); other data are available as supplementary materials.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Gao Y-F et al. , Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol 161, 296–300 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hindle AG et al. , J. Exp. Biol 218, 276–284 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riedesel ML, Steffen JM, Fed. Proc 39, 2959–2963 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patra AK, Aschenbach JR, J. Adv. Res 13, 39–50 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harlow H, in Comparative Physiology of Fasting, Starvation, and Food Limitation, McCue MD, Ed. (Springer, 2012) pp. 277–296. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-642-29056-5_17 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walpole ME et al. , J. Dairy Sci 98, 1204–1213 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epperson LE, Karimpour-Fard A, Hunter LE, Martin SL, Physiol. Genomics 43, 799–807 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu Z et al. , Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 308, R283–R293 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carey HV, Walters WA, Knight R, Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 304, R33–R42 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevenson TJ, Duddleston KN, Buck CL, Appl. Environ. Microbiol 80, 5611–5622 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y et al. , Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 318, G189–G202 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epperson LE, Rose JC, Carey HV, Martin SL, Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 298, R329–R340 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rice SA et al. , Nat. Metab 2, 1459–1471 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rémésy C, Moundras C, Morand C, Demigné C, Am. J. Physiol 272, G257–G264 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rongstad OJ, J. Mammal 46, 76 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mousa HM, Ali KE, Hume ID, Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Comp. Physiol 74, 715–720 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sommer F et al. , Cell Rep 14, 1655–1661 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.FAO, “The State of Food Insecurity in the World (S0FI)” (FAO, 2014) www.fao.org/publications/card/en/c/56efdla2-0f6e-4185-8005-62170e9b27bb/. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marty E, Liu Y, Samuel A, Or O, Lane J, Bone 105, 276–286 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langran M, Moran BJ, Murphy JL, Jackson AA, Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 82, 191–198 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Metagenomic data are available at NCBI (PRJNA693524); other data are available as supplementary materials.