Abstract

Most caregiving literature has focused on women, who have traditionally taken on caregiving roles. However, more research is needed to clarify the mixed evidence regarding the impact of gender on caregiver/patient psychological outcomes, especially in an advanced cancer context. In this paper, we examine gender differences in caregiver stress, burden, anxiety, depression, and coping styles, as well as how caregiver gender impacts patient outcomes in the context of advanced cancer. Eighty-eight patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers completed psychosocial surveys. All couples were heterosexual and most caregivers were women (71.6%). Female caregivers reported significantly higher levels of perceived stress, depression, anxiety, and social strain compared with male caregivers, and female patients of male caregivers were more likely to use social support as a coping style compared with male patients of female caregivers. These findings highlight the potential differences between male and female caregivers’ needs and psychological health.

Keywords: Caregiving, Gender, Spouse, Advanced cancer, Marriage

Introduction

In addition to the direct impact on patients, a diagnosis of cancer has direct implications for caregivers, especially spouse caregivers because they are frequently involved in direct care and management of the patient (Stenberg, Ruland, & Miaskowski, 2010; Stetz, 1987). Cancer is the third most common reason for adult caregiving (National Alliance for Caregiving, 2015), and can have important implications for psychological and physical health. Although some caregivers have reported benefits from providing care (Hudson, 2004; Kang et al., 2013; Wong, Ussher, & Perz, 2009), the negative outcomes associated with caregiving are important, have been well documented, and include outcomes such as high stress, poor health, unmet needs, depressive symptoms, and caregiver burnout (Fitzell & Pakenham, 2010; Girgis, Lambert, Johnson, Waller, & Currow, 2013; Hagedoorn, Sanderman, Bolks, Tuinstra, & Coyne, 2008; Li, Mak, & Loke, 2013; Matthews, Baker, & Spillers, 2004; Northouse, Williams, Given, & McCorkle, 2012; Perz, Ussher, Butow, & Wain, 2011).

Caregivers of advanced cancer patients are at greater risk for adverse outcomes when compared with caregivers of other kinds of patients, which is likely due to increased need for physical care of the patient and greater emotional concerns (Andershed, 2006; Cameron, Franche, Cheung, & Stewart, 2002; Palos et al., 2011; Rumpold et al., 2016). Additionally, witnessing the deterioration or suffering of one’s partner, and coping with impending loss, may cause additional distress or depression for spouse caregivers more than other types of caregivers (Carr, House, Wortman, Nesse, & Kessler, 2001; Grunfeld et al., 2004; Kim & Schulz, 2008; Prigerson et al., 2003; Rossi Ferrario, Cardillo, Vicario, Balzarini, & Zotti, 2004). As such, patients with advanced cancer may need more attention (both physical and emotional) from their family caregivers, which may create increased pressure on the caregiver. Given these unique experiences, it is important that the literature expands from its primary focus on early-stage cancer to capture the experience of patients with advanced cancer and their spouse caregivers.

In understanding the demands placed on spouse caregivers, most literature has focused on women. Women provide most of the paid and unpaid acts of caregiving (National Alliance for Caregiving, 2015), and feelings and actions associated with caring are likewise part of women’s accepted social roles in many cultures worldwide (Cancian & Oliker, 2000). Women are traditionally viewed as “kin-keepers and care providers,” shaped not only by familial experiences and expectations but societal expectations and gender norms (Aronson, 1992; Fleming & Agnew-Brune, 2015; Gaugler et al., 2008; Moen, Robison, & Dempster-McClain, 1995, pp. 259). Nevertheless, approximately 40% of the caregivers in the United States are men, which means there are around 16 million male caregivers in the United States, and this number is increasing (Accius, 2017; National Alliance for Caregiving, 2015).

There is a small but growing literature on gender differences in caregiving, yet evidence is mixed regarding the impact of caregiving on psychological outcomes. A literature review by Li et al. (2013) found that although caring for a spouse affects males and females differently, both male and female spouse caregivers are affected by secondary stressors (e.g., relationship, lifestyle, sleep, finance). Female spouse caregivers of cancer patients, compared with male spouse caregivers, have typically been found to have higher levels of stress, depression, and anxiety (Barnoy, Bar-Tal, & Zisser, 2006; Dumont et al., 2006; Kim, Loscalzo, Wellisch, & Spillers, 2006; Langer, Abrams, & Syrjala, 2003; Li et al., 2013; Morgan, Ann Williams, Trussardi, & Gott, 2016; Pinquart & Duberstein, 2005; Swinkels, Tilburg, Verbakel, & Broese van Groenou, 2019). However, other studies found that male spouse caregivers experienced higher distress (Baider, Ever-Hadani, Goldzweig, Wygoda, & Peretz, 2003; Goldzweig et al., 2009), and still others have found no gender differences in stress or anxiety (Northouse, Templin, & Mood, 2001; Oechsle, Goerth, Bokemeyer, & Mehnert, 2013). Research on factors that may mediate the relationship between caregiving and psychosocial outcomes, such as social support, is also mixed (Goldzweig et al., 2009; Northouse et al., 2001).

These differences may be a byproduct of different approaches to caregiving by men and women (Campbell & Carroll, 2007; Mott, Schmidt, & MacWilliams, 2019). Female spouse caregivers tend to complete more care tasks than male spouse caregivers (Li et al., 2013), but male caregivers are more likely than female caregivers to be employed, which can add additional strain (Accius, 2017; Navaie-Waliser, Spriggs, & Feldman, 2002). Caregiving could also be particularly challenging for male spouse caregivers, as in addition to navigating new roles (e.g., patient and caregiver) and maintaining old roles (e.g., husband and wife), they experience a shift in traditional gender roles (Russell, 2007). Evidence suggests that role conflict such as this can cause stress and lower an individual’s level of psychological well-being (Burke & Stets, 2009; Hecht, 2001). Men’s gender role conflict, more specifically, has been linked to depression, substance abuse, and relationship issues (O’Neil, 2015). Male spouse caregivers appear to take on a more intensive caregiving role compared with other types of male caregivers, such as brothers or sons (Accius, 2017; Wagner, Bigatti, & Storniolo, 2006), providing care for a longer period of time, and assisting with more activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (Accius, 2017). Rather than reflecting only gender, kinship ties and obligations that accompany aspects of gender play an important role in the performance of care (Comas-d’Argemir & Soronellas, 2019). Understanding the many complex interrelationships between people, context, and the cancer trajectory adds to an expanded conceptual model of the cancer family caregiving experience proposed by Fletcher, Miaskowski, Given, and Schumacher (2012). In using this conceptual model, we do not limit ourselves to a single theory. Rather, we hope to understand advanced cancer caregiving in a more holistic manner.

More research has been called for that specifically focuses on variations in the caregiver experience and how these are influenced by factors such as gender (Stenberg et al., 2010). Additionally, most previous work focuses on patients and caregivers with early-stage cancers. There is a growing literature on caregiving in the advanced or life-limiting cancer context (Dionne-Odom et al., 2019; Dumont et al., 2006; Grov, Dahl, Moum, & Fosså, 2005) yet more research is needed, especially on the differential impacts of caregiving based on gender (Allen, 1994; Stenberg et al., 2010). For instance, work conducted by Dionne-Odom et al. (2019) articulates the ways in which family caregivers assist their advanced cancer patients with healthcare decision-making; this is an important addition to the literature, but other than highlighting that most caregivers in their sample are female (95%), there is no discussion about gender. Given the limited work and inconsistent findings regarding gender differences in spouse caregivers of cancer patients, our goals are threefold: (1) to identify potential differences in the amount of spousal caregiving provided by males and females; (2) to examine how gender influences caregiver stress, burden, anxiety, and depression as well as patient psychosocial outcomes; and (3) explore how caregiver gender influences coping styles.

Methods

This was a secondary data analysis of questionnaire data completed at a single time point by advanced cancer patients and their spouse caregivers as part of a larger study of naturalistic patient-caregiver communication (Reblin et al., 2018).

Participants

Patients at a large NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center were screened for eligibility criteria using clinic schedules and medical records. Inclusion criteria for patients included a diagnosis of stage III or IV non-small cell lung or pancreatic, esophageal, gastric, gallbladder, colorectal, hepatocellular, or bile duct cancer; Karnofsky Performance Status (Peus, Newcomb, & Hofer, 2013) scores of 70+ (i.e., able to care for self, but normal activity may be limited); a prognosis of more than 6 months; and undergoing active treatment at the Cancer Center. Inclusion criteria were selected to identify advanced cancer patients with high enough functional status to complete the aims of the primary study, which involved a full day of study-related activities. Patient participants had a cohabiting spouse/partner who identified as providing some care and also agreed to participate. Both patient and caregiver were required to be over 18 years of age and English-speaking/writing. Participants were approached in clinic; study staff verified eligibility and obtained informed consent from each patient and spouse that wished to participate.

Measures

Patients and caregivers separately completed questionnaires on demographic and health factors, including the amount of time spent caregiving and the number of ADLs/IADLs caregivers assisted with. Both patients and caregivers also completed the following psychosocial measures. For all measures, higher scores indicate higher levels of the construct.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

The HADS is a 14-item scale capturing state anxiety and depression. Each item on the questionnaire is scored from 0 to 3 (no to high anxiety); a summed score is calculated for each 7-item subscale between 0 and 21. This scale has been validated among cancer family caregivers in both screening and research (Bjelland, Dahl, Haug, & Neckelmann, 2002).

Perceived Stress Scale

The 4-item Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, 1988; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983) was used to capture baseline stress levels for patient and caregiver. This scale has previously been used in cancer patients (Golden-Kreutz, Browne, Frierson, & Andersen, 2004) and caregiver populations (Kessler et al., 2014).

Caregiver Burden Scale

Caregiver burden was assessed for caregivers only using the Caregiver Burden Scale, a 14-item survey that measures the impact of caregiving on three dimensions of burden: objective, subjective demand, and subjective stress (Montgomery, Gonyea, & Hooyman, 1985a; Montgomery, Stull, & Borgatta, 1985b). Objective burden is defined as the perceived interruption of the tangible aspects of a caregiver’s life (Ferrell & Mazanec, 2009). Subjective demand burden is the caregiver’s perceived demands of caregiving responsibilities (Ferrell & Mazanec, 2009). Subjective stress burden is the caregiver’s perceived emotional response to the caregiving responsibilities (Ferrell & Mazanec, 2009; Montgomery, Stull, et al., 1985b). The ordinal scale ranges from 1 (a lot less) to 5 (a lot more). Cut-off scores were established for each of the burden dimensions, with Objective Burden scores of > 23, Subjective Demand Burden score of > 15, and Subjective Stress Burden score of > 13.5 indicating higher levels of burden (Montgomery, Stull, et al., 1985b).

Duke Social Support and Stress Scale (DUSOCS)

The DUSOCS (Parkerson, Broadhead, & Tse, 1991; Parkerson Jr. et al., 1989) includes subscales for network social support and network social stress. Over 12-items, respondents use a 3-point scale (none to a lot) to rate people who give personal support and people who cause stress.

Coping Self-Efficacy Scale (CSE)

The CSE (Chesney, Neilands, Chambers, Taylor, & Folkman, 2006) is a 13-item scale used to measure confidence in performing coping behaviors under stress. There are three subscales: using problem-focused coping (6 items), stopping unpleasant emotions and thoughts (4 items), and getting support from friends and family (3 items).

Communication and Attitudinal Self-Efficacy Scale for Cancer (CASE)

The CASE is a 12-item scale of self-efficacy to maintain productive communication and a positive attitude in the face of cancer (Wolf, Chang, Davis, & Makoul, 2005). The scale consists of three, 4-item subscales: understanding and participating in care, maintaining a positive attitude, and seeking and obtaining information.

Preparedness subscale of the Family Care Inventory

Preparedness for caregiving was assessed for caregivers only and was measured by the 8-item Preparedness subscale of the Family Care Inventory, which assesses the perceived level of preparation for various facets of caregiving such as dealing with physical needs and emotional problems (Archbold, Stewart, Greenlick, & Harvath, 1990). A five-point Likert-type scale is used ranging from 0 (not at all prepared) to 4 (very well prepared). The scale also assesses previous caregiving experience.

Couples Satisfaction Index (CSI)

Relationship satisfaction was measured using the 4-item CSI where participants respond using a 6-point Likert-type scale (Funk & Rogge, 2007). The CSI discriminates between distressed and non-distressed relationships (Funk & Rogge, 2007) and a meta-analysis found excellent reliability (range 0.90–0.98) and an average Cronbach’s alpha of 0.94 (Graham, Diebels, & Barnow, 2011).

Analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted on all measures, as shown in Table 1, using IBM SPSS 25 (IBM Corp., 2017). Significance for all analyses was specified at α = 0.05 (two-tailed). Differences in quantitative variables were analyzed using t-tests. Categorical variables were analyzed by a Chi square test (Polit & Beck, 2008).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and measures

| Characteristic | Number of participants (%)/mean (range) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver | Statistic | p value | Patient | Statistic | p value | |||||

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | |||||

| Demographics | ||||||||||

| Gender | 25 (28.4) | 63 (71.6) | 88 (100) | 63 (71.6) | 25 (28.4) | 88 (100) | ||||

| Age | 66.5 (47–84) | 64 (39–80) | 65 (45–78) | 67.5 (44–89) | ||||||

| Length of relationship | 34.5 (2–58) | 33.9 (1–64) | 0.15 | 0.8796 | 35 (8–58) | 33.8 (1–64) | 0.33 | 0.7419 | ||

| Race | ||||||||||

| AI/AN | 0 | 2 (2.3) | 2 (2.3) | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 22 (25.0) | 57 (64.8) | 79 (89.8) | 24 (27.3) | 58 (65.9) | 82 (93.2) | ||||

| African–American | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.4) | 4 (4.5) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (4.5) | 5 (5.7) | ||||

| Other | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic | 24 (27.9) | 57 (66.3) | 81 (94.2) | 0.2118 | 1 | 25 (28.4) | 60 (68.2) | 85 (96.6) | 1.2325 | 0.2669 |

| Hispanic | 1 (1.2) | 4 (4.65) | 5 (5.8) | 0 | 3 (3.4) | 3 (3.4) | ||||

| Religious affiliation | ||||||||||

| Catholic | 7 (8.4) | 14 (16.9) | 21 (25.3) | 0.9556 | 0.9165 | 5 (6.0) | 14 (16.9) | 19 (22.9) | 4.2076 | 0.3786 |

| Jewish | 1 (1.2) | 4 (4.8) | 5 (6.0) | 1 (1.2) | 3 (3.6) | 4 (4.8) | ||||

| Protestant | 9 (10.8) | 23 (27.7) | 32 (38.6) | 13 (15.7) | 22 (26.6) | 35 (42.2) | ||||

| Other | 4 (4.8) | 11 (13.3) | 15 (18.1) | 4 (4.8) | 8 (9.6) | 12 (14.5) | ||||

| No religious affiliation | 4 (4.8) | 6 (7.2) | 10 (12.1) | 1 (1.2) | 12 (14.5) | 13 (15.7) | ||||

| Financial situation | ||||||||||

| Not very good | 3 (3.5) | 7 (8.1) | 10 (11.5) | 0.0715 | 0.9649 | 2 (2.4) | 9 (10.6) | 11 (12.9) | 0.6358 | 0.7277 |

| Comfortable | 17 (19.5) | 41 (47.1) | 58 (66.7) | 15 (17.7) | 35 (41.2) | 50 (58.8) | ||||

| More than adequate to meet my needs | 5 (5.8) | 14 (16.1) | 19 (21.8) | 7 (8.2) | 17 (20.0) | 24 (28.2) | ||||

| Education | ||||||||||

| Less than high school | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.3) | 7.1088 | 0.2127 | 0 | 3 (3.4) | 3 (3.4) | 8.0048 | 0.156 |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 4 (4.6) | 10 (11.4) | 14 (15.9) | 7 (8) | 6 (6.8) | 13 (14.8) | ||||

| Some college or vocational school | 6 (6.82) | 26 (29.6) | 32 (36.4) | 7 (8) | 22 (25.0) | 29 (32.9) | ||||

| College graduate (4 years) | 5 (5.7) | 8 (9.1) | 13 (14.8) | 2 (2.3) | 14 (15.9) | 16 (18.2) | ||||

| Some graduate or professional school | 0 | 6 (6.82) | 6 (6.8) | 2 (2.3) | 5 (5.7) | 7 (8) | ||||

| Graduate or professional degree | 9 (10.2) | 12 (13.6) | 21 (23.9) | 7 (8) | 13 (14.8) | 20 (22.7) | ||||

| Employment | ||||||||||

| Not currently employed | 15 (17.7) | 38 (44.7) | 53 (62.4) | 0.8182 | 0.6643 | 23 (26.4) | 44 (50.6) | 67 (77.0) | 4.7772 | 0.0918 |

| Part-time | 2 (2.4) | 9 (10.6) | 11 (12.9) | 0 | 5 (5.8) | 5 (5.8) | ||||

| Full-time | 7 (8.2) | 14 (16.5) | 21 (24.7) | 2 (2.30) | 13 (14.9) | 15 (17.2) | ||||

| Overall health | ||||||||||

| Excellent | 2 (2.3) | 12 (13.6) | 14 (15.9) | 3.5583 | 0.3133 | 3 (3.4) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (4.6) | 6.5578 | 0.1612 |

| Very good | 14 (15.9) | 24 (27.3) | 38 (43.2) | 9 (10.2) | 23 (26.1) | 32 (36.4) | ||||

| Average | 8 (9.1) | 26 (29.6) | 34 (38.6) | 9 (10.2) | 19 (21.6) | 28 (31.8) | ||||

| Poor | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.3) | 3 (3.4) | 18 (20.5) | 21 (23.9) | ||||

| Very poor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.3) | 3 (3.4) | ||||

| Psychosocial measures | ||||||||||

| HADS | ||||||||||

| Anxiety | 5.8 (0–16) | 8.6 (0–19) | −2.85 | 0.0054 | 5.0 (0–12) | 5.2 (0–13) | −0.28 | 0.7817 | ||

| Depression | 3.3 (0–9) | 5.3 (0–15) | −2.9 | 0.0051 | 4.4 (0–12) | 4.8 (0–14) | −0.65 | 0.5151 | ||

| Total | 9.0 (0–23) | 13.9 (1–32) | −3.39 | 0.0012 | 9.3 (1–22) | 10.0 (1–26) | −0.51 | 0.6123 | ||

| Perceived Stress Scale | 4.7 (1–9) | 6.3 (0–13) | −2.26 | 0.026 | 4.0 (0–11) | 4.7 (0–12) | −0.91 | 0.3659 | ||

| Caregiver burden | ||||||||||

| Objective burden | 21.5 (17–29) | 22.3 (14–30) | −0.95 | 0.3464 | ||||||

| Stress burden | 13.5 (8–16) | 14.3 (8–20) | −1.7 | 0.0945 | ||||||

| Demand burden | 11.8 (4–18) | 11.8 (4–19) | −0.07 | 0.9453 | ||||||

| DUSOCS | ||||||||||

| Social support | 11.1 (5–18) | 11.7 (5–20) | −0.722 | 0.473 | 13.5 (9–18) | 12.1 (5–20) | 1.498 | 0.138 | ||

| Social stress | 2.2 (0–8) | 2.9 (0–7) | −1.579 | 0.118 | 1.7 (0–5) | 1.7 (0–10) | −0.114 | 0.910 | ||

| Coping self-efficacy | ||||||||||

| Problem focused | 52.9 (34–70) | 49.9 (17–70) | 1.01 | 0.315 | 54.8 (0–32) | 52.2 (4–70) | 0.82 | 0.4148 | ||

| Emotion focused | 24.4 (8–40) | 22.7 (0–40) | 0.7 | 0.4837 | 29.6 (7–40) | 29.4 (4–40) | 0.28 | 0.7829 | ||

| Social support | 20.6 (11–30) | 19.9 (2–30) | 0.48 | 0.6297 | 25.0 (14–30) | 21.8 (0–30) | 1.99 | 0.0496 | ||

| Total | 91.9 (60–130) | 87.0 (25–130) | 0.87 | 0.3864 | 102.4 (54–130) | 96.0 (20–130) | 1.11 | 0.2691 | ||

| CASE | ||||||||||

| Participate in care | 13.4 (10–16) | 13.5 (9–16) | −0.21 | 0.8358 | 14.8 (11–16) | 13.6 (10–16) | 1.56 | 0.123 | ||

| Positive attitude | 12.8 (9–16) | 11.8 (4–16) | 1.69 | 0.0956 | 13.5 (11–16) | 13.0 (4–16) | 1.03 | 0.3052 | ||

| Seek information | 13.7 (12–16) | 13.7 (8–16) | 0.08 | 0.9365 | 14.0 (10–16) | 13.2 (7–16) | 1.59 | 0.1146 | ||

| Preparedness-Family Care Inventory | 21.3 (10–31) | 21.4 (5–32) | −0.05 | 0.9606 | ||||||

| Couples Satisfaction Index | 20.2 (13–24) | 20.6 (13–24) | 0.139 | 0.617 | 21.3 (17–24) | 19.16 (7–24) | 7.872 | 0.022 | ||

Results

Eighty-eight spouse caregivers (n = 63 women, n = 25 men) of patients with stage III or IV cancer participated in this study. Although this study was open to all sexual orientations, our study sample consisted of only heterosexual spousal couples. The sample consisted of older adults with an average caregiver age of 65 (SD = 9.4) and patient age of 66.8 (SD = 9.2). The average number of years married was 34 (SD = 15.7). The sample was predominantly white (90% of caregivers, 93% of caregivers). See Table 1 for demographics and descriptive statistics for patients and caregivers separated by gender.

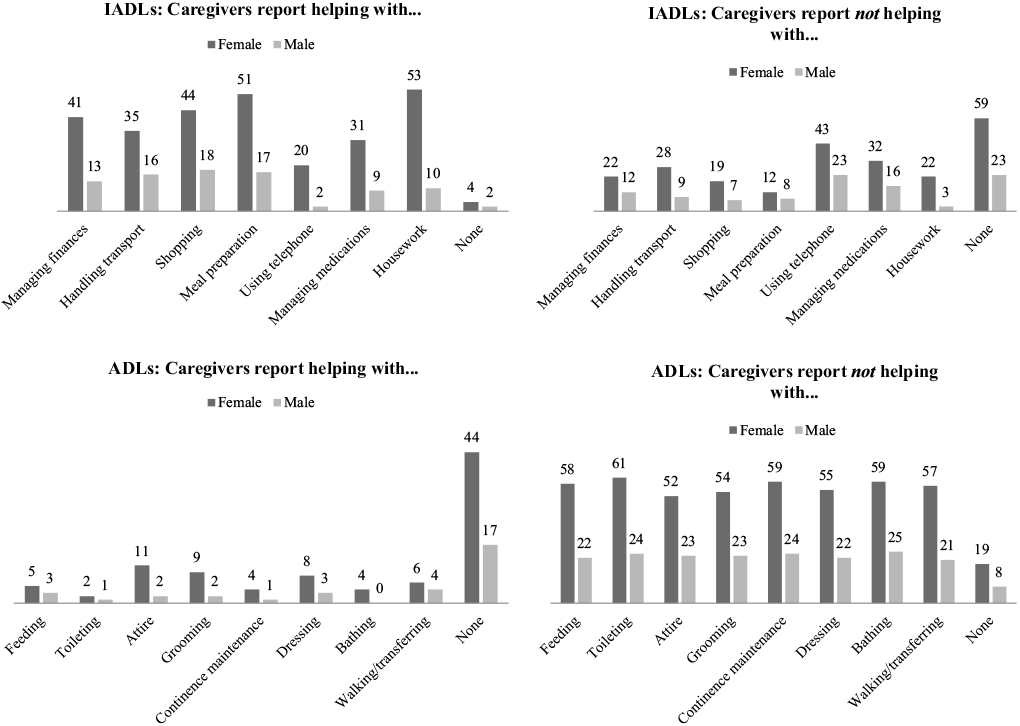

There were no significant gender differences for patient or caregiver demographics, including race/ethnicity, education, religion, employment, financial situation, income, insurance, age, years married, number of people living in the home, and medical history. There were no differences in caregiving variables, such as the number of ADLs, years caregiving, or hours of care provided per week. Caregivers reported caring for their spouse on average between 4.4 months (female) and 5.6 months (male) prior to the study, for an average of 10 h (female) to 12.7 h (male) per week. Although there were no significant gender differences in caregiving tasks assessed through ADLs and IADLs, Fig. 1 shows which caregiving tasks spousal caregivers reporting doing and not doing. Male spouse caregivers and female spouse caregivers also did not differ in terms of caregiver burden (demand, objective, or stress burden). However, female spouse caregivers reported significantly higher levels of perceived stress (t = −2.26, p < 0.05), depression (t = −2.90, p < 0.01), and anxiety (t = −2.85, p < 0.01) compared with male spouse caregivers. Patient perceived stress, anxiety, and depression were not significantly different based on the gender of the caregiver.

Fig. 1.

Number of caregivers who report ADL and IADL help or not

There were no significant differences in caregiver self-efficacy for coping (CSE) or communication (CASE), social support, or preparedness for caregiving. However, female patients of male spouse caregivers were found to be more likely to use social support as a coping style than male patients with female spouse caregivers (t = 1.99, p < 0.05). Male patients also reported significantly higher satisfaction with their relationships with their caregivers than did female patients (t = 7.872, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Our first goal was to identify potential differences in the amount of time and type of caregiving provided by males and females. We found no gender differences, which is consistent with other findings (Neal, Ingersoll-Dayton, & Starrels, 1997; Ussher & Sandoval, 2008). However, our results stand in contrast to other research which has reported that women spend more time caregiving and take on more caregiving tasks (Gaugler et al., 2008; Morgan et al., 2016; Navaie-Waliser et al., 2002). One potential reason for the lack of observed gender differences in the amount of time spent caregiving is that there were no significant differences in the employment status of male and female caregivers. Men are generally more often employed outside the home (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019), but the relatively similar employment rates in our sample, combined with the low rates of full-time work across genders, could lead to more equitable amounts of time available to spend providing care. However, the overall reported amount of time spent caregiving, along with number of caregiving tasks, was relatively low. Although the patients in our study were selected to be relatively high-functioning, the low amount of time reported caregiving is somewhat surprising given that patients were all in an advanced stage of cancer. National statistics indicate that cancer caregivers report spending, on average, approximately 33 h caregiving per week (National Alliance for Caregiving, 2016). Spouse caregivers in this study reported spending an average of 11.2 h per week on caregiving activities, yet a wide range was also reported (0–70 h per week). This may be due to the proximity of the “time spent caregiving” question to the question about caregiving tasks, which were specifically focused on ADLs and IADLs. In a study of informal caregivers of people with chronic illnesses (55% of the sample cared for their spouse/partner), which evaluated and measured ways of recording informal care tasks, participants reported spending 5.8 h per day performing ADLs, IADLs, and housework (Van den Berg & Spauwen, 2006). However, caregiving tasks can also encompass emotional work, such as providing emotional support, or tasks such as information-seeking, communicating updates or coordinating visits from friends and family, and logistics, such as scheduling appointments. Spouses, and maybe wives in particular, may include these caregiving tasks in their normal expectations of being a spouse (Williams, Giddings, Bellamy, & Gott, 2017). This is echoed by research that shows that spouses often do not identify as caregivers (Allen, Goldscheider, & Ciambrone, 1999; Williams et al., 2017).

Our second goal was to examine how gender influences caregiver stress, burden, anxiety, and depression as well as patient psychosocial outcomes. We found that, despite no significant differences in reported amount of caregiving, female spouse caregivers reported more stress, depression, and anxiety compared with male spouse caregivers. Prior studies demonstrate mixed findings as to gender differences in the caregiver experience (Li & Loke, 2013; Li et al., 2013). Yet, our findings align with numerous prior studies indicating females experience more stress, anxiety, and depression (Barnoy et al., 2006; Dumont et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2006; Langer et al., 2003; Pinquart & Duberstein, 2005). It is not clear if this gender difference exists due to primary stressors, such as patient illness related factors, or secondary stressors, such as role change or financial distress (Fletcher et al., 2012).

This finding may have direct impacts on our third goal, which was to explore if caregiver gender influenced coping styles. Although we found no gender differences in caregiver coping strategies, this may suggest that the impact of caregiving on women is more complicated than what was assessed with our measures; this calls for a closer look at cognitive and behavioral responses to a cancer diagnosis and caregiving through the lens of gender (Fletcher et al., 2012). Considering our results that female patients of male spouse caregivers were more likely to use social support as a coping style than male patients with female spouse caregivers, more work is needed to untangle the ways in which gender affects caregivers and coping.

It may be argued that quantitative measures are not accurately capturing the caregiver experience. How do we reconcile our female participants’ reported anxiety, depression, and stress with their relative lack of reported caregiver burden? The broader health literature suggests that women’s traditional orientation to a more communal (“other-focused” versus “self-focused”) self-representation and increased sensitivity to relationship cues may impact their caregiving experience and increase their risk for negative health outcomes, such as depression (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). Although there were no differences in male and female caregiver self-reported relationship satisfaction, we did not assess relationship expectations. The way people think about their relationships can have an important impact on their health and well-being (Robles, 2014). Because caregiving is part of an expected social role that women are assumed to perform, there is a decreased desire to describe caregiving as burdensome, similar to the underreporting of some behaviors due to perceived social stigma and the desire to portray oneself positively (Bharadwaj, Pai, & Suziedelyte, 2017). Role theory suggests “humans act in varying and predictable ways based on the expectations and conditions of the social role they are assuming” (Bastawrous, 2013, p. 435; Biddle, 1986). The Caregiver Burden Scale may not accurately reflect actual burden because women understand their social role and do not wish to be seen as unhappy with their “expected and natural” social role. In other words, societal expectations can impact a person’s perceptions of what is normal and acceptable, and the scales we used may be assessing perceived versus actual burden. Measures such as ADLs and IADLs may capture more traditionally “male” tasks such as transferring and walking (requiring physical strength on the part of the caregiver) or managing finances (Campbell & Carroll, 2007; Mott et al., 2019). However, in research on household division of labor, women have been found to bear more of the “mental load,” as they are responsible for not only completing more tasks, but also managing, planning, and organizing the household tasks (Lachance-Grzela & Bouchard, 2010). Female spouse caregivers may be similarly shouldering a greater mental load in caregiving, impacting their psychosocial outcomes. Future research should capture both physical and emotional caregiving tasks and use multiple methods to avoid self-report bias, particularly because objectively measured behaviors explained considerably more of the variance than self-report data among women compared with men (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001).

Interestingly, in our analysis of patient data we found that, consistent with assumed U.S. gender roles, female patients used social support as a coping mechanism more than male patients did. One limitation of our study is that we did not assess the larger caregiving network that normally surrounds a person, and instead focused on one primary caregiver. Female patients’ greater use of social support may lower the caregiving demand on male spouse caregivers. Women tend to have a larger, female-oriented social network, which may decrease burden on their primary male caregiver (Sims-Gould, Martin-Matthews, & Rosenthal, 2010). This would potentially reflect the greater levels of stress, anxiety, and depression that were found in female spousal caregivers, as their spouses rely primarily on them for support rather than a wider network of people. This could also indicate that female patients of male spouse caregivers may not be receiving the “social” aspect of caregiving, which is reflected in the work of male caregivers focusing on the “masculine” aspects of caregiving (Mott et al., 2019).

Limitations

This study was a secondary analysis of data. As a result, important variables such as role change, utilization of support resources, and social identity were not captured. Additionally, this study did not have enough power to assess if some measures either explain (e.g., mediate) or alter (e.g., moderate) the effect gender may have on these outcome measures. Furthermore, our sample consists of heterosexual, racially-homogeneous, and mostly mid-life to older adults drawn from a single institution and may not be generalizable to more diverse samples. Future studies in advanced cancer caregiving should focus on other subpopulations to understand the vast array of lived experiences.

Conclusion

Our study is one of the first to assess potential gender differences in caregiving activities, psychosocial outcomes, and coping among spouse caregivers in an advanced cancer population. The importance of understanding differential caregiver experience along the cancer trajectory is important, and our findings have clinical implications for the health system more broadly and those treating cancer patients more specifically. Our findings echo previous research that indicates that cancer caregivers report high levels of distress (Girgis et al., 2013; Sklenarova et al., 2015). Caregiving stress has been shown to impact psychological and physiological health and even mortality (Teixeira, Remondes-Costa, Graça Pereira, & Brandão, 2019); further, the mechanisms by which stress impacts men and women may differ (Espnes & Byrne, 2008; Taylor et al., 2000). Thus, it is important for health systems to attend to those providing care, especially as the numbers of family caregivers increase with an aging population. More specifically, providers of advanced cancer patients should focus on caregivers stress given that caregiver well-being also predicts patient perception of quality of care (Litzelman, Kent, Mollica, & Rowland, 2016) and increased patient hospital admission and longer hospital stays, often due to inability to manage patient symptoms (Ankuda et al., 2017; Bonin-Guillaume et al., 2015; Dionne-Odom et al., 2016). Female caregivers, in particular, may need additional screenings or psychological support to address their increased levels of stress, anxiety, and depression experienced during the caregiving process. Caregiver stress can also be distressing for patients and have impacts on their health, so interventions designed to improve caregiver health should be included in holistic patient care (Kim, Carver, Shaffer, Gansler, & Cannady, 2015; Litzelman & Yabroff, 2015; Waldron, Janke, Bechtel, Ramirez, & Cohen, 2013). We urge researchers to consider gender more explicitly when assessing cancer caregivers and to use measures that more accurately assess potential differences. Just as biomedical researchers have begun to understand the impact that sex can have on disease phenotypes in animal research, and thus the need to explicitly state sex in their materials and methods (Flórez-Vargas et al., 2016), social science researchers must not assume that gender makes no difference in caregiving. A movement towards gender-sensitive models of both research and interventions and away from generalized models is needed (Gabriel, Beach, & Bodenmann, 2010). In moving forward, we echo the work of Fletcher et al. (2012) who call for the stress process and cancer trajectory to be embedded within the larger context of cancer caregiving. To accomplish this methodological and theoretical aim, researchers should employ multiple methods to fully understand the caregiver experience.

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply grateful to the participants of this study.

Funding

American Cancer Society ACS MRSG 13-234-01-PCSM; PI: Reblin.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Dana Ketcher, Ryan Trettevik, Susan T. Vadaparampil, Richard E. Heyman, Lee Ellington, Maija Reblin declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (Chesapeake IRB, Pro00015311) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

References

- Accius J (2017). Breaking stereotypes: Spotlight on male family caregivers. AARP Public Policy Institute, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Allen SM (1994). Gender differences in spousal caregiving and unmet need for care. Journal of Gerontology, 49, S187–S195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen SM, Goldscheider F, & Ciambrone DA (1999). Gender roles, marital intimacy, and nomination of spouse as primary caregiver. The Gerontologist, 39, 150–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andershed B (2006). Relatives in end-of-life care–part 1: A systematic review of the literature the five last years, January 1999–February 2004. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15, 1158–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankuda CK, Maust DT, Kabeto MU, McCammon RJ, Langa KM, & Levine DA (2017). Association between spousal caregiver well-being and care recipient healthcare expenditures. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 10.1111/jgs.15039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Greenlick MR, & Harvath T (1990). Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Research in Nursing and Health, 13, 375–384. 10.1002/nur.4770130605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J (1992). Women’s sense of responsibility for the care of old people: “But who else is going to do it?”. Gender and Society, 6, 8–29. [Google Scholar]

- Baider L, Ever-Hadani P, Goldzweig G, Wygoda MR, & Peretz T (2003). Is perceived family support a relevant variable in psychological distress? A sample of prostate and breast cancer couples. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55, 453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnoy S, Bar-Tal Y, & Zisser B (2006). Correspondence in informational coping styles: How important is it for cancer patients and their spouses? Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 105–115. 10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bastawrous M (2013). Caregiver burden: A critical discussion. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50, 431–441. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj P, Pai MM, & Suziedelyte A (2017). Mental health stigma. Economics Letters, 159, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle BJ (1986). Recent developments in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 12, 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, & Neckelmann D (2002). The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52, 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonin-Guillaume S, Durand A-C, Yahi F, Curiel-Berruyer M, Lacroix O, Cretel E, et al. (2015). Predictive factors for early unplanned rehospitalization of older adults after an ED visit: Role of the caregiver burden. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 27, 883–891. 10.1007/s40520-015-0347-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019). Employment characteristics of families—2018. (USDL-19-0666). Retrieved May 25, 2019, from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/famee.pdf

- Burke PJ, & Stets JE (2009). Identity theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JI, Franche R-L, Cheung AM, & Stewart DE (2002). Lifestyle interference and emotional distress in family caregivers of advanced cancer patients. Cancer, 94, 521–527. 10.1002/cncr.10212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LD, & Carroll MP (2007). The incomplete revolution: Theorizing gender when studying men who provide care to aging parents. Men and Masculinities, 9, 491–508. 10.1177/1097184x05284222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cancian FM, & Oliker SJ (2000). Caring and gender. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, House JS, Wortman C, Nesse R, & Kessler RC (2001). Psychological adjustment to sudden and anticipated spousal loss among older widowed persons. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56, S237–S248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Neilands TB, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, & Folkman S (2006). A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 421–437. 10.1348/135910705X53155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S (1988). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In Oskamp SSS (Ed.), The social psychology of health (pp. 31–67). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-d’Argemir D, & Soronellas M (2019). Men as carers in long-term caring: Doing gender and doing Kinship. Journal of Family Issues, 40, 315–339. 10.1177/0192513x18813185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dionne-Odom JN, Ejem D, Wells R, Barnato AE, Taylor RA, Rocque GB, et al. (2019). How family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer assist with upstream healthcare decision-making: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 14, e0212967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionne-Odom JN, Hull JG, Martin MY, Lyons KD, Prescott AT, Tosteson T, et al. (2016). Associations between advanced cancer patients’ survival and family caregiver presence and burden. Cancer Medicine, 5, 853–862. 10.1002/cam4.653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont S, Turgeon J, Allard P, Gagnon P, Charbonneau C, & Vezina L (2006). Caring for a loved one with advanced cancer: Determinants of psychological distress in family caregivers. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 9, 912–921. 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espnes GA, & Byrne D (2008). Gender differences in psychological risk factors for development of heart disease. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 24, 188–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR, & Mazanec P (2009). Family caregivers. In Hurria A & Balducci L (Eds.), Geriatric oncology (pp. 135–155). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzell A, & Pakenham KI (2010). Application of a stress and coping model to positive and negative adjustment outcomes in colorectal cancer caregiving. Psycho-Oncology, 19, 1171–1178. 10.1002/pon.1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming PJ, & Agnew-Brune C (2015). Current trends in the study of gender norms and health behaviors. Current Opinion in Psychology, 5, 72–77. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher BS, Miaskowski C, Given B, & Schumacher K (2012). The cancer family caregiving experience: an updated and expanded conceptual model. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, 387–398. 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flórez-Vargas O, Brass A, Karystianis G, Bramhall M, Stevens R, Cruickshank S, et al. (2016). Bias in the reporting of sex and age in biomedical research on mouse models. Elife, 5, e13615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk JL, & Rogge RD (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel B, Beach SR, & Bodenmann G (2010). Depression, marital satisfaction and communication in couples: Investigating gender differences. Behavior Therapy, 41, 306–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Given WC, Linder J, Kataria R, Tucker G, & Regine WF (2008). Work, gender, and stress in family cancer caregiving. Supportive Care in Cancer, 16, 347–357. 10.1007/s00520-007-0331-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis A, Lambert S, Johnson C, Waller A, & Currow D (2013). Physical, psychosocial, relationship, and economic burden of caring for people with cancer: A review. Journal of Oncology Practice, 9, 197–202. 10.1200/jop.2012.000690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden-Kreutz DM, Browne MW, Frierson GM, & Andersen BL (2004). Assessing stress in cancer patients: A second-order factor analysis model for the Perceived Stress Scale. Assessment, 11, 216–223. 10.1177/1073191104267398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldzweig G, Hubert A, Walach N, Brenner B, Perry S, Andritsch E, et al. (2009). Gender and psychological distress among middle- and older-aged colorectal cancer patients and their spouses: an unexpected outcome. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 70, 71–82. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JM, Diebels KJ, & Barnow ZB (2011). The reliability of relationship satisfaction: A reliability generalization meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov EK, Dahl AA, Moum T, & Fosså SD (2005). Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in caregivers of patients with cancer in late palliative phase. Annals of Oncology, 16, 1185–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, Clinch J, Reyno L, Earle CC, et al. (2004). Family caregiver burden: Results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 170, 1795–1801. 10.1503/cmaj.1031205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tuinstra J, & Coyne JC (2008). Distress in couples coping with cancer: A meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 1–30. 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht LM (2001). Role conflict and role overload: Different concepts, different consequences. Sociological Inquiry, 71, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson P (2004). Positive aspects and challenges associated with caring for a dying relative at home. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 10, 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2017). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (version 25.0). Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Shin DW, Choi JE, Sanjo M, Yoon SJ, Kim HK, et al. (2013). Factors associated with positive consequences of serving as a family caregiver for a terminal cancer patient. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 564–571. 10.1002/pon.3033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler ER, Moss A, Eckhardt SG, Laudenslager ML, Kilbourn K, Mauss IB, et al. (2014). Distress among caregivers of phase I trial participants: A cross-sectional study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22, 3331–3340. 10.1007/s00520-014-2380-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, & Newton TL (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 472–503. 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Carver CS, Shaffer KM, Gansler T, & Cannady RS (2015). Cancer caregiving predicts physical impairments: Roles of earlier caregiving stress and being a spousal caregiver. Cancer, 121, 302–310. 10.1002/cncr.29040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Loscalzo MJ, Wellisch DK, & Spillers RL (2006). Gender differences in caregiving stress among caregivers of cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 15, 1086–1092. 10.1002/pon.1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, & Schulz R (2008). Family caregivers’ strains: Comparative analysis of cancer caregiving with dementia, diabetes, and frail elderly caregiving. Journal of Aging and Health, 20, 483–503. 10.1177/0898264308317533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachance-Grzela M, & Bouchard G (2010). Why do women do the lion’s share of housework? A decade of research. Sex Roles, 63, 767–780. [Google Scholar]

- Langer S, Abrams J, & Syrjala K (2003). Caregiver and patient marital satisfaction and affect following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A prospective, longitudinal investigation. Psycho-Oncology, 12, 239–253. 10.1002/pon.633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li QP, & Loke AY (2013). A spectrum of hidden morbidities among spousal caregivers for patients with cancer, and differences between the genders: A review of the literature. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17, 578–587. 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li QP, Mak YW, & Loke AY (2013). Spouses’ experience of caregiving for cancer patients: A literature review. International Nursing Review, 60, 178–187. 10.1111/inr.12000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litzelman K, Kent EE, Mollica M, & Rowland JH (2016). How does caregiver well-being relate to perceived quality of care in patients with cancer? Exploring associations and pathways. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22, 1–2. 10.1200/jco.2016.67.3434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litzelman K, & Yabroff KR (2015). How are spousal depressed mood, distress, and quality of life associated with risk of depressed mood in cancer survivors? Longitudinal findings from a national sample. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers, 24, 969–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews BA, Baker F, & Spillers RL (2004). Family caregivers’ quality of life: Influence of health protective stance and emotional strain. Psychology and Health, 19, 625–641. 10.1080/0887044042000205594 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moen P, Robison J, & Dempster-McClain D (1995). Caregiving and women’s well-being: A life course approach. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 259–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RJV, Gonyea JG, & Hooyman NR (1985a). Caregiving and the experience of subjective and objective burden. Family Relations, 34, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RJV, Stull DE, & Borgatta EF (1985b). Measurement and the analysis of burden. Research on Aging, 7, 137–152. 10.1177/0164027585007001007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan T, Ann Williams L, Trussardi G, & Gott M (2016). Gender and family caregiving at the end-of-life in the context of old age: A systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 30, 616–624. 10.1177/0269216315625857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott J, Schmidt B, & MacWilliams B (2019). Male caregivers: Shifting roles among family caregivers. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 23, E17–E24. 10.1188/19.CJON.E17-E24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015 report. Retrieved May 25, 2019, from https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/2015_CaregivingintheUS_Final-Report-June-4_WEB.pdf

- National Alliance for Caregiving. (2016). Cancer caregiving in the US: An intense, episodic, and challenging care experience. Retrieved May 25, 2019, from https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CancerCaregivingReport_FINAL_June-17-2016.pdf

- Navaie-Waliser M, Spriggs A, & Feldman PH (2002). Informal caregiving: Differential experiences by gender. Medical Care, 40, 1249–1259. 10.1097/01.MLR.0000036408.76220.1F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal MB, Ingersoll-Dayton B, & Starrels ME (1997). Gender and relationship differences in caregiving patterns and consequences among employed caregivers. The Gerontologist, 37, 804–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse LL, Templin T, & Mood D (2001). Couples’ adjustment to breast disease during the first year following diagnosis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 24, 115–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse LL, Williams A-L, Given B, & McCorkle R (2012). Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30, 1227–1234. 10.1200/jco.2011.39.5798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oechsle K, Goerth K, Bokemeyer C, & Mehnert A (2013). Anxiety and depression in caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients: Impact on their perspective of the patients’ symptom burden. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 16, 1095–1101. 10.1089/jpm.2013.0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil JM (2015). Men’s gender role conflict: Psychological costs, consequences, and an agenda for change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Palos GR, Mendoza TR, Liao K-P, Anderson KO, Garcia-Gonzalez A, Hahn K, et al. (2011). Caregiver symptom burden: The risk of caring for an underserved patient with advanced cancer. Cancer, 117, 1070–1079. 10.1002/cncr.25695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkerson GR Jr., Broadhead WE, & Tse CK (1991). Validation of the duke social support and stress scale. Family Medicine, 23, 357–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkerson GR Jr., Michener JL, Wu LR, Finch JN, Muhlbaier LH, Magruder-Habib K, et al. (1989). Associations among family support, family stress, and personal functional health status. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 42, 217–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perz J, Ussher JM, Butow P, & Wain G (2011). Gender differences in cancer carer psychological distress: An analysis of moderators and mediators. European Journal of Cancer Care (English Language Edition), 20, 610–619. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01257.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peus D, Newcomb N, & Hofer S (2013). Appraisal of the Karnofsky performance status and proposal of a simple algorithmic system for its evaluation. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 13, 72. 10.1186/1472-6947-13-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, & Duberstein PR (2005). Optimism, pessimism, and depressive symptoms in spouses of lung cancer patients. Psychology and Health, 20, 565–578. 10.1080/08870440412331337101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, & Beck CT (2008). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Cherlin E, Chen JH, Kasl SV, Hurzeler R, & Bradley EH (2003). The Stressful Caregiving Adult Reactions to Experiences of Dying (SCARED) Scale: A measure for assessing caregiver exposure to distress in terminal care. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11, 309–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reblin M, Heyman RE, Ellington L, Baucom BRW, Georgiou PG, & Vadaparampil ST (2018). Everyday couples’ communication research: Overcoming methodological barriers with technology. Patient Education and Counseling, 101, 551–556. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF (2014). Marital quality and health: Implications for marriage in the 21st century. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23, 427–432. 10.1177/0963721414549043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi Ferrario S, Cardillo V, Vicario F, Balzarini E, & Zotti AM (2004). Advanced cancer at home: Caregiving and bereavement. Palliative Medicine, 18, 129–136. 10.1191/0269216304pm870oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpold T, Schur S, Amering M, Kirchheiner K, Masel E, Watzke H, et al. (2016). Informal caregivers of advanced-stage cancer patients: Every second is at risk for psychiatric morbidity. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24, 1975–1982. 10.1007/s00520-015-2987-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R (2007). Men doing “Women’s Work:” Elderly men caregivers and the gendered construction of care work. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sims-Gould J, Martin-Matthews A, & Rosenthal CJ (2010). Family caregiving and helping at the intersection of gender and kinship. In Martin-Matthews A & Phillips JE (Eds.), Aging and caring at the intersection of work and home life: Blurring the boundaries (p. 312). London: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sklenarova H, Krumpelmann A, Haun MW, Friederich HC, Huber J, Thomas M, et al. (2015). When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer, 121, 1513–1519. 10.1002/cncr.29223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg U, Ruland CM, & Miaskowski C (2010). Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 19, 1013–1025. 10.1002/pon.1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetz KM (1987). Caregiving demands during advanced cancer: The spouse’s needs. Cancer Nursing, 10, 260–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinkels J, Tilburg TV, Verbakel E, & Broese van Groenou M (2019). Explaining the gender gap in the caregiving burden of partner caregivers. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74, 309–317. 10.1093/geronb/gbx036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, Gruenewald TL, Gurung RAR, & Updegraff JA (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107, 411–429. 10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira RJ, Remondes-Costa S, Graça Pereira M, & Brandão T (2019). The impact of informal cancer caregiving: A literature review on psychophysiological studies. European Journal of Cancer Care, 28, e13042. 10.1111/ecc.13042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussher JM, & Sandoval M (2008). Gender differences in the construction and experience of cancer care: The consequences of the gendered positioning of carers. Psychology and Health, 23, 945–963. 10.1080/08870440701596585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg B, & Spauwen P (2006). Measurement of informal care: An empirical study into the valid measurement of time spent on informal caregiving. Health Economics, 15, 447–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner CD, Bigatti SM, & Storniolo AM (2006). Quality of life of husbands of women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 15, 109–120. 10.1002/pon.928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron EA, Janke EA, Bechtel CF, Ramirez M, & Cohen A (2013). A systematic review of psychosocial interventions to improve cancer caregiver quality of life. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 1200–1207. 10.1002/pon.3118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LA, Giddings LS, Bellamy G, & Gott M (2017). ‘Because it’s the wife who has to look after the man’: A descriptive qualitative study of older women and the intersection of gender and the provision of family caregiving at the end of life. Palliative Medicine, 31, 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf MS, Chang CH, Davis T, & Makoul G (2005). Development and validation of the Communication and Attitudinal Self-Efficacy scale for cancer (CASE-cancer). Patient Education and Counseling, 57, 333–341. 10.1016/j.pec.2004.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WT, Ussher J, & Perz J (2009). Strength through adversity: Bereaved cancer carers’ accounts of rewards and personal growth from caring. Palliative and Supportive Care, 7, 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]