Abstract

It is widely acknowledged that cancer affects not only patients but also their friends and family members who provide informal, and typically unpaid, care. Given the dual impact that cancer often has on patients and their informal caregivers (i.e., family members, partners, or friends), an expanded dyadic framework that encompasses a range of health and psychosocial outcomes and includes primary caregivers with a range of relationships to the patients is critically needed. Moreover, an emphasis on the role of social and contextual factors may help the framework resonate with a broader range of patient-caregiver relationships and allow for the development of more effective dyadic interventions. This article describes the development of the Dyadic Cancer Outcomes Framework, which was created to guide future research and intervention development. Using an iterative process, we conducted a conceptual review of currently used dyadic and/or caregiving models and frameworks and developed our own novel dyadic framework. Our novel Dyadic Cancer Outcomes Framework highlights individual and dyad-level predictors and outcomes, as well as incorporating the disease trajectory and the social context. This framework can be used in conjunction with statistical approaches including the Actor Partner Interdependence Model to evaluate outcomes for different kinds of partner-caregiver dyads. This flexible framework can be used to guide intervention development and evaluation for cancer patients and their primary caregivers, with the ultimate goal of improving health, psychosocial, and relationship outcomes for both patients and caregivers. Future research will provide valuable information about the framework’s effectiveness for this purpose.

Keywords: Cancer, Caregiving, Patient-reported outcomes, Dyadic research, Social determinants of health, Family

1. Introduction

More than 1 in 3 people in the United States will develop cancer in their lifetimes (American Cancer Society, 2019). There are almost 17 million cancer survivors in the U.S., and this number is expected to swell to over 22 million by 2030 (Miller et al., 2019). Cancer, like other serious illnesses, has a ripple effect through a patient’s social network. There are aspects of the cancer experience that make it distinct from other chronic diseases: the complex, multimodal treatment regimens patients undergo, often with substantial side effects; the increased delivery of care in home or outpatient settings, which can burden caregivers; substantial financial impacts of treatment for patients and families; and ongoing worries about recurrence even if patients reach long-term survivorship (Badr et al., 2019; Kent et al., 2016). Because cancer affects not only patients but also their family and friends (Institute of Medicine, 2005), most Americans will be touched by cancer at some point in their lives.

In 2020, over 53 million American adults were estimated to be serving as informal caregivers, with nearly 3 million providing care specifically to a person with cancer (American Association for Retired Persons NAFC, 2020). Informal cancer caregivers are family members, partners, or friends of the patient who provide unpaid support in a variety of ways, including multiple domains of social support, assistance with daily living, and clinical care tasks (Kent et al., 2019). Some individuals care alone, while others are part of a network of caregivers organized around the care recipient (Pinquart and Duberstein, 2010). The number and depth of supportive care tasks, time spent caring, financial impact of caring, and burden experienced by caregivers vary by the severity of the patient’s illness, the patient-caregiver relationship prior to diagnosis, and other individual caregiver and patient characteristics (e.g., caregiver gender, or type of treatment the patient receives) (Coumoundouros et al., 2019; Kent et al., 2019). Cost estimates are one way of valuing caregivers’ worth; far more compelling are the stories of patients and caregivers about the impact of cancer on their lives.

1.1. Terminology

For the sake of simplicity, we use the terms patient and caregiver to differentiate between the person diagnosed with cancer and the person providing support, but these terms will not necessarily resonate for every dyad. Some have argued for describing people with cancer as survivors from diagnosis onward, but many people with cancer do not identify with that designation, especially during active treatment (Cheung and Delfabbro, 2016). At the same time, people who have completed active treatment may be less likely to identify with the term patient (Costa et al., 2019). The term caregiver has become standard in English language research studies, and we use it because it is inclusive of a range of relationships. It is important to note, however, that caregivers themselves may not identify with this language and may, for example, identify more strongly with their role in relationship to the patient (e.g., husband, daughter). The dyadic relationship context may affect the readiness with which a caregiver identifies not only with the term but also with the associations that the term carries. Developing a caregiver identity rests on role perceptions, family and gender norms, and other critical psychosocial factors (Eifert et al., 2015). Although the terms patient and caregiver are conceptually useful for researchers, it is important for clinicians and researchers to carefully consider the terms that will best apply to their populations of interest.

1.2. Rationale

The purpose of this paper was to incorporate insights from two separate lines of research: caregiving literature, and literature of the effects of cancer on dyads. Our aim was to integrate prior conceptual work into a broad framework that can be used to guide research and intervention development for dyads of cancer patients and their primary caregivers.

Given the increasing number of individuals with cancer and their caregivers, it is critical to understand how cancer affects both members of a cancer-caregiver dyad and how their health and psychosocial outcomes may be interrelated (Berry et al., 2017). A dyadic focus is useful because the process of caregiving, like many dyadic processes, is inherently relational and takes place in an interpersonal context (Kenny et al., 2006). Although the broader social network of cancer patients and their caregivers is undoubtedly important (Kroenke, 2018), we focus here on the interpersonal relationship between the patient and one primary caregiver who provides substantial care and support to the patient. Dyadic interventions for patients with cancer and their caregivers have been developed to address the needs of the patient, the caregiver, and the relationship simultaneously, but such interventions have, for the most part, shown small to moderate effects and are rarely implemented in clinical care (Badr et al., 2019).

Much previous dyadic work examined the effects of cancer on spousal pairs (Hagedoorn et al., 2008; Manne and Badr, 2008). Given that over 40% of American adults are currently unpartnered, however (Fry, 2017), and that partnership patterns vary widely based on factors such as education and racial/ethnic background (Horowitz et al., 2019), it is important to examine other types of supportive relationships. A report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine recommended explicitly and consistently addressing the needs of families that are diverse along a variety of dimensions when developing supports and policies for caregivers (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine., 2016). An expanded dyadic model of cancer caregiving that acknowledges the nuances of this relationship context may yield a framework that resonates with a wider set of caregivers and allow for the development of more effective and tailored interventions.

2. Methods

To create our expanded framework, we conducted a conceptual review of the literature on these topics (McGregor, 2018; Shankardass et al., 2019). The process of framework development was iterative, with members of the research team discussing elements of prior models and incorporating them into and refining our new model. Framework development took place from January 2020–April 2021, first through an in-person discussion and thereafter through Zoom meetings with the entire U.S.-based authorship team. Because we did not collect human subject data, Institutional Review Board approval was not needed.

Our work integrates key insights from a group of prior models and frameworks (described below) that focus on different aspects of the patient-caregiver relationship. The first three models are explicitly dyadic and focus on a close relationship between a patient and a significant other; these models can be used with statistical methods such as the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (Kenny et al., 2006), which accounts for the interdependence of dyadic data in order to examine mental and physical health outcomes for both members of a pair. The second set of models address the social context of caregiving. We point out differences in scope and focus of prior models below. We sought to integrate their diverse strengths into a general, flexible model of how a cancer diagnosis can affect outcomes for both a patient and a primary caregiver.

Berg and Upchurch’s Developmental-Contextual Model of Couples Coping with Chronic Illness Across the Adult Lifespan (2007) focuses on chronic illnesses in general, but much of the empirical work the authors draw from involves cancer patients. The model posits that dyadic appraisal affects dyadic coping, which in turn affects the couple’s adjustment. The focus is on spousal relationships, and the dyad is the unit of analysis. The model includes both the sociocultural context (including culture and gender) and the proximal context, including marital quality and characteristics of the chronic illness. Time is incorporated into the model in several ways: in terms of historic time periods, people’s developmental changes across their lifespans, the progression of chronic illnesses, and the day-to-day time in which spouses interact with one another. The model involves primarily psychological outcomes and does not incorporate individual outcomes (e.g., an individual’s physical health).

Manne and Badr’s Intimacy and Relationship Process Model (2008) is a dyadic model that centers on cancer in particular, again in the context of the marital relationship, and again with the couple as the unit of analysis. In this model, partners’ relationship-enhancing behaviors (e.g., partner responsiveness) or relationship-compromising behaviors (e.g., criticism) affect their relationship intimacy, which in turn affects the couple’s psychological and marital adaptation; there are also direct pathways from relationship behaviors to a couple’s adaptation. Although this addresses couples in which one member faces cancer, it emphasizes the pair’s relationship as spouses or intimate partners, rather than conceptualizing one person as a patient and the other as a caregiver, and it depicts their relationship as a resource they both can draw on. Although the authors acknowledge that physical, sociodemographic, or medical variables likely affect outcomes for the couple as well, these are not explicitly incorporated into the model.

Pietromonaco et al. (2013) created a theoretical framework grounded in Attachment Theory to describe how each person’s relationship orientation (i.e., attachment style) affects processes within the dyad (e.g., relationship behaviors such as support-seeking), which in turn affect proximal outcomes (such as affect, physiology, health behaviors) and then distal health and disease outcomes. This model has several important innovations. One unique feature of the model is that it considers a range of relationships, not only intimate partner relationships. Although the authors focus primarily on intimate partners in their empirical examples, in their conceptual model dyad members are described simply as Partner A and Partner B. Although it does address caregiving in a broad sense—encompassing both support provision in the context of an illness and emotional responsiveness in daily interactions—this framework does not emphasize the social context or incorporate factors specific to cancer.

Fletcher et al. (2012) developed a model of cancer family caregiving that illustrates the effect of stressors on a caregiver’s well-being. This model, which takes the caregiver as the unit of analysis, focuses on how the stress process affects caregiver health and wellbeing, including negative effects such as caregiving strain and positive effects such as personal growth and life satisfaction. This model provides a nuanced examination of the illness trajectory, from the patient’s initial diagnosis and treatment through either end-of-life care/bereavement or cancer-free survival. It also includes the personal, sociocultural, economic, and health care contexts. Although the model includes the effect of patient illness-related factors (e.g. type of treatment) on the caregiver, it does not specifically address the effects of the caregiver on the patient’s health. The authors note that an important next step for caregiving theory will be incorporating a dyadic perspective into caregiving models and a more in-depth examination of the social context, including disparities in accessing care, culture, and socioeconomic factors.

Young et al. (2020) also emphasize the social context of caregiving in the Heterogeneity of Caregiving Model. This model is consistent with multilevel ecological models in that it depicts multiple levels of the caregiving experience and context. The caregiver (referred to as the carer) is at the center, along with characteristics of the caregiver such as age, sexual orientation, and gender. The next level includes the person receiving care, as well as characteristics of the care recipient such as disease/condition and functional/cognitive status. The third level includes caregiving characteristics such as length of caregiving and the strength of the social network, and the final level includes the broader caregiving context, such as financial and community resources. This model centers caregivers and their context; it does not focus on caregiver outcomes or relational processes. A key takeaway from this model is that, in light of caregiver heterogeneity, a tailored approach to intervention that is responsive to caregiver factors may be more effective than a one-size-fits-all approach.

Marshall et al. (2011) draw on family systems theory and sociocultural frameworks in their model of Culture and Social Class for Families Facing Cancer. This model, which includes caregivers as one unit of analysis but does not have an explicitly dyadic focus, is designed to facilitate health promotion and psychosocial intervention among families that are diverse in culture and social class. It depicts the person with cancer as embedded in a social context that includes the family, one or more caregivers, and a broader social network. This model is useful because it examines how cancer affects an entire family and can inform how strengths-based interventions are developed and later adapted for different populations.

3. Results: introducing the Dyadic Cancer Outcomes Framework

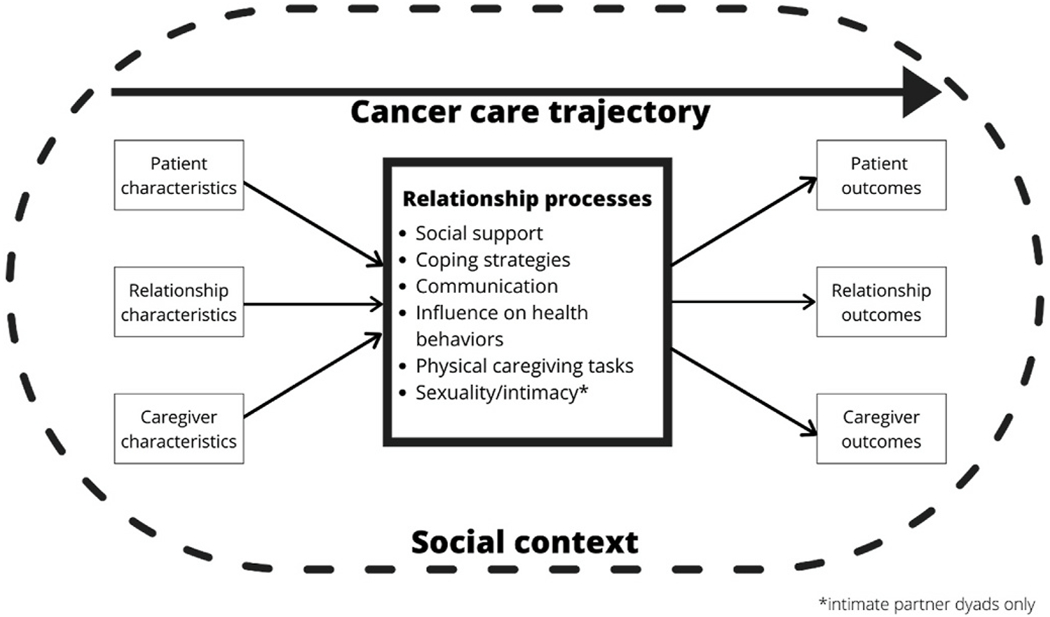

Cancer spans all race/ethnicities, age groups, gender identities, household incomes, and levels of educational attainment, making the experience ubiquitous but not uniform. Our new Dyadic Cancer Outcomes Framework (Fig. 1) builds on prior theoretical work and accounts for a range of factors that affect the experiences and outcomes of the dyad. The Dyadic Cancer Outcomes Framework highlights the relationship context of the dyad, the broad social context, and a wide range of dyadic and individual-level outcomes. Here, we describe the individual components of the framework, followed by implications for intervention development and clinical practice. Citations to support the components of this framework are meant to be illustrative rather than exhaustive; wherever possible, we refer to systematic reviews and other syntheses of the literature.

Fig. 1.

The Dyadic Cancer Outcomes Framework.

3.1. Patient characteristics

Characteristics of patients and caregivers affect outcomes not only for themselves but also the other member of the dyad. Many individual-level patient characteristics have been associated with outcomes for patients and their caregivers. Patient demographic and social characteristics such as self-described gender and race/ethnicity, age, education, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, health literacy, social support, and insurance status have been associated with outcomes including mortality, mental and physical health, quality of life, and unmet needs (Brandão et al., 2017; Gordon et al., 2019; Halbach et al., 2016; Kelley et al., 2019; Marshall et al., 2011; Puts et al., 2012; Siegel et al., 2020; Syrowatka et al., 2017). In research among heterosexual couples in which one person has cancer, for example, women tend to exhibit greater levels of distress than men, regardless of role (i.e., patient or partner) (Hagedoorn et al., 2008), and older patients often report less distress (Brandão et al., 2017; Streck & LoBiondo-Wood, 2020; Syrowatka et al., 2017). Financial toxicity has been associated with negative psychosocial health outcomes including anxiety and depression in patients (Chan et al., 2019).

Cancer-related factors such as cancer site, stage at diagnosis, and treatment modalities also affect patient and caregiver outcomes (Brandão et al., 2017; Siegel et al., 2020; Syrowatka et al., 2017). Among survivors, the most prevalent cancers are breast, uterine, and colorectal for women, and prostate, colorectal, and melanoma for men (Miller et al., 2019); these cancers all have very different prognoses and trajectories.

Psychological and physical health factors such as mental health, physical health status, and comorbidities have also been associated with outcomes in patients and/or caregivers (Brandão et al., 2017; Sarfati et al., 2016; Streck et al., 2020). Chronic conditions are more common with age; the majority of cancer survivors are 65 years of age or older, with comorbidity burden increasing with age (Bluethmann et al., 2016). Although health behaviors such as smoking and physical activity are often modeled as mediators of more distal health outcomes, they can also be analyzed as predictors (Syrowatka et al., 2017).

3.2. Caregiver characteristics

Caregiver characteristics also affect the experiences of the dyad; many of these overlap with the patient characteristics describe above, but some are distinctive. A majority (58%) of cancer caregivers in the U.S. are female, with an average age of 53.1, and about 2/3 are married or partnered (Hunt et al., 2016). Family structure, competing demands, and social support can both add to and buffer against caregiving stressors (Baider and Surbone, 2014). For example, caregivers “sandwiched” between raising minor children, employment, and caring for an elderly family member with cancer might feel exhausted and overwhelmed but also fulfilled and provided with enough social connections for support (Kim et al., 2006). Furthermore, cultural norms around the value, importance, and opportunity costs of caregiving can affect expectations and actual experiences (Penrod et al., 2012). The familism-to-individualism spectrum is multidimensional and intersectional (Knight and Sayegh, 2010). Caregiving norms can manifest through cultural drives to care for family members and through the pull of obligation, leading caregivers to cope by asking for or rejecting additional help (Knight and Sayegh, 2010). Finally, differences in healthcare literacy (Bevan and Pecchioni, 2008) and interactions with healthcare systems (Wolff et al., 2020) are associated with caregiver stress and burden, in turn affecting patient and relationship outcomes.

3.3. Relationship characteristics

Relationship characteristics can be measured at two levels of analysis: individual or dyadic. Researchers can, for example, examine concordance between both members of the dyad on individual-level variables such as communication (Siminoff et al., 2020), assessment of the patient’s symptoms (Silveira et al., 2010), mental health (Lee and Lyons, 2019), health behaviors (Doyle et al., 2020; Regan et al., 2012; Weaver et al., 2011) and cancer-related concerns (Martinez et al., 2020). Relationship-level variables include length of relationship (Jose and Alfons, 2007), frequency of interaction, stage of relationship, communication, and conflict (Thompson and Walker, 1982). Relationship quality is another factor that can affect health outcomes. Marital quality, for example, is related to better health in general, including a lower risk of mortality (Robles et al., 2014). In cancer caregivers, better relationship quality has been associated with better family functioning and less social stress (Litzelman et al., 2016).

The type of relationship between patient and caregiver can affect the caregiving experience (Romito et al., 2013; Streck et al., 2020). The most frequently studied type of relationship is spousal, often assumed to be heterosexual (Hagedoorn et al., 2008; Kent et al., 2019; Ochoa et al., 2020). Sexual minority couples often face different challenges and stressors than heterosexual couples (Kimberly and Williams, 2017; Newcomb, 2020; Suter et al., 2006), but dyadic research about the effects of cancer on the relationships of sexual minority people with cancer (Newcomb, 2020; Thompson et al., 2020) as well as interventions (Kamen et al., 2016) has been sparse. Caregiver relationships other than intimate partnerships include parent-child, siblings, and friends, but research on how these specific types of relationships affect cancer caregiving has been lacking (Streck et al., 2020).

Geographical proximity between caregiver and care recipient also affects the caregiving experience. Tennstedt et al. (1993) hypothesized that co-residence, rather than spousal kinship tie, is more important to reported patterns of caregiving for older adults who are disabled; indeed, they found that spouses and other co-residing caregivers exhibit similar patterns of care and formal service use. The small body of work examining distance caregivers has shown that such caregivers face unique challenges and stressors (Cagle and Munn, 2012) including lack of support from and interaction with the health care team, and few opportunities to benefit from psychosocial and educational interventions (Douglas et al., 2016). Increasingly, research on distance caregiving examines the ways in which telehealth and technology-mediated interventions have the potential to help caregivers support patients from a distance (Chi and Demiris, 2015; J. Y. Shin et al., 2018).

3.4. Relationship processes

The Dyadic Cancer Outcomes Framework reflects the fact that the interdependence seen between patients and caregivers unfolds through a series of relationship processes (Manne and Badr, 2008). Several key relationship processes are described below.

Social support.

Social support is a multidimensional construct that includes provision or perceptions of emotional, informational, practical assistance, and companionship (Thoits, 2011; Uchino, 2009). This support often comes from significant others such as family members, friends, or coworkers (Kelley et al., 2019; Sherbourne and Stewart, 1991; Thoits, 2011). Among married couples, for example, social support can provide physiological and psychosocial benefits, although there may be negative consequences of mismatched or unwanted support (Kiecolt-Glaser and Wilson, 2017). Social support may also influence physiological factors related to cancer progression (Lutgendorf and Sood, 2011). In both cancer patients and caregivers, social support can play an important role in reducing psychosocial distress and improving quality of life (Bigatti et al., 2011; Hasson-Ohayon et al., 2010). Among dyads in which one person has cancer, a person’s own perception of social support has been found to be most strongly associated with their own health outcomes; partner effects of social support, however, may differ based on factors such as time since diagnosis or cancer site (Kelley et al., 2019).

Coping strategies.

Stress and coping models have guided caregiving research and suggest several intervention targets: primary and secondary stressors, appraisal, and coping strategies (Fletcher et al., 2012). Many patients and caregivers cope together as a dyad when facing cancer (Badr and Acitelli, 2017; Li and Loke, 2014b; Manne and Badr, 2008). According to stress and coping models, the two main goals of dyadic coping are reducing distress for both people in the dyad and maintaining or improving of relationship functioning (Bodenmann, 2005). A review of the dyadic coping literature found that cancer patients and caregivers employ coping strategies that include cognitive (e.g., cognitive restructuring, mindfulness) and behavioral (e.g., problem solving, behavioral activation); emotional/physiologic (e.g., relaxation practices); and existential/spiritual (e.g., engaging in religious practices) (Badr and Acitelli, 2017; Greer et al., 2020). Reviews of couple-based interventions have identified strategies for improving coping; these include couple-based communication (Li et al., 2020); psychoeducation, skills training, and therapeutic counseling (Li and Loke, 2014a); and emotion-focused therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and behavioral marital therapy (Badr and Krebs, 2013).

Communication.

Communication processes are important in the management of both cancer and the relationship (Badr, 2017; Li and Loke, 2014b). Open communication within the dyad improves both physical and mental health outcomes, including quality of life and relationship satisfaction (Porter et al., 2017; Song et al., 2012). Manne and Badr (2008) base their relationship intimacy model on relationship-enhancing versus relationship-compromising communication processes. Other researchers have used the developmental-contextual model from Berg and Upchurch (Berg and Upchurch, 2007) to describe how communication facilitates the management of chronic illnesses between couples, specifically though dyadic communication efficacy (Magsamen-Conrad et al., 2015). Communication patterns can change throughout the cancer trajectory and may be affected by factors such as social support and symptoms (Song et al., 2012). Communication analyses have also examined specific factors such as resilience (Lillie et al., 2018), caregiver preparedness (Otto et al., 2020), avoidance and protective buffering (Langer et al., 2009; Shin et al., 2016), and coping (Falconier and Kuhn, 2019).

Influence on health behaviors.

Another way that patients and caregivers can affect each other’s health outcomes is by influencing each other’s health behaviors (e.g., diet, exercise, and alcohol consumption). Intimate partners, in particular, have been shown to attempt to improve each other’s health by using a range of social influence/social control tactics, such as reasoning with a partner or dropping hints about healthy behavior (Lewis et al., 2006; Umberson et al., 2018). Partners can also have negative influence on health behaviors as well as positive ones (e.g., by modeling or encouraging certain eating habits) (Reczek, 2012). Intimate partners also tend to demonstrate both concordance in behaviors and convergence over time (Kiecolt-Glaser and Wilson, 2017). In cancer patient-caregiver dyads, health behaviors including diet and exercise may be interrelated and influenced by characteristics of both members of the dyad (Ellis et al., 2017; Shaffer et al., 2016). Health behaviors such as smoking—or discordance in smoking behaviors—may be associated with quality of life in patient-caregiver dyads (Weaver et al., 2011).

Physical caregiving tasks.

In addition to other relationship processes, caregivers often perform physical tasks when providing care. Both clinical care tasks and assistance with activities of daily living are conducted by a significant number of cancer caregivers. In the National Alliance for Caregiving 2016 comparison of cancer and non-cancer caregivers, cancer caregivers were significantly more likely to assist with activities such as bed and chair transfers (57% vs. 42%), toileting (46% vs. 26%), dressing (42% vs. 31%), and feeding (39% vs. 22%) (Hunt et al., 2016). In a study of lung and colorectal cancer patients, 68% of caregivers reported assisting with monitoring for side effects, and the mean number of all care tasks assisted with over a 2-week period was 6.3 (van Ryn et al., 2011). The care and intimacy involved with such interactions is likely to affect not only patient health outcomes, but also the dyadic relationship itself.

Sexuality/intimacy.

Maintaining a sexual relationship is important but challenging for many intimate partner dyads facing cancer. Treatment for most common cancers often leads to side effects that can impact sexual functioning (Abbott-Anderson and Kwekkeboom, 2012; Harrington et al., 2010; Stulz et al., 2020), and caregiving can present challenges that affect sexual expression (Badr et al., 2019). In intimate partner dyads in which one person has cancer, sexual functioning has been correlated with factors including relationship satisfaction, quality of life, and depression (Kayser et al., 2018; Santos-Iglesias et al., 2020; Streck & LoBiondo-Wood, 2020). The effect of cancer on sexual functioning in patients can vary by factors such as cancer site and treatment modality (Hamilton et al., 2016; Maiorino et al., 2016). A systematic review of patient-physician communication found that sexual issues are not discussed with many cancer patients, especially women (Reese et al., 2017). Interventions have been developed to address sexual functioning in intimate partner dyads with cancer, with some focused primarily on sexuality and others including that as a component of a broader dyadic intervention (Kang et al., 2018; Li and Loke, 2014a).

3.5. Patient outcomes

To use Actor Partner Interdependence Models or similar types of statistical analyses, parallel outcomes must be assessed in both patients and caregivers. Common outcome measures in caregiver-patient dyads include distress, anxiety, depression, stress, physical and mental quality of life, and sleep (Kayser et al., 2018; Streck et al., 2020). Although dyadic influence on health behaviors is a mediator in our framework, health behaviors may also be studied as outcomes in themselves (Ellis et al., 2017; Shaffer et al., 2016). Depending on the research questions and modeling techniques used, is also possible to examine similar types of outcomes in patients only, or to assess patient-specific outcomes such as mortality, performance status, symptom burden, or unmet needs (Aizer et al., 2013; Harrington et al., 2010; Puts et al., 2012; Siegel et al., 2020; Streck et al., 2020). Although examining patient-only or caregiver-only outcomes may be appropriate for a particular intervention or research topic, true dyadic research includes dyadic, relationship, or interdependent outcomes.

3.6. Caregiver outcomes

Research focusing on caregiver-specific outcomes has found that while some caregivers report benefits from providing care (Girgis et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2013), caregivers also experience negative outcomes including high stress, unmet needs, poor health, and symptoms of anxiety and depression (Girgis et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013; Northouse et al.,2012). Physical health consequences experienced by caregivers may include sleep difficulties and fatigue (Berger et al., 2005; Girgis et al.,2013), poor immune functioning (G. E. Miller et al., 2008; Rohleder et al., 2009), and cardiovascular disease and stroke (Ji et al., 2012). Research on cancer caregivers’ health behaviors has been mixed; while many caregivers report positive behaviors in terms of physical activity, diet, and sleep, some report negative health behaviors that have been linked to negative coping styles (Litzelman et al., 2018; Ross et al., 2013).

3.7. Relationship outcomes

Relationship-level outcomes can also be evaluated in the context of cancer. In the Relationship Intimacy Model, for example, dyadic outcomes include couples’ relationship intimacy and couples’ relationship and psychological adaptation (Manne and Badr, 2008). The Developmental-Contextual Model also focuses on relationship-level outcomes: dyadic appraisal affects dyadic coping, which in turn affects the couple’s adjustment (Berg and Upchurch, 2007). A systematic review of dyadic coping and relationship functioning and found that supportive behaviors, open communication, and positive dyadic coping were related to better relationship functioning (Traa et al., 2015b). Researchers have also assessed sexual, marital, and general life function among intimate partner dyads (Traa et al., 2015a).

3.8. Cancer care trajectory

Cancer affects patients, caregivers, and dyads in different ways during diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship (Kent et al., 2019; Ochoa et al., 2020). Most of the processes described here unfold over time (Berg and Upchurch, 2007). Although some research involving caregivers has examined change over time (Kim et al., 2013; Lee and Lyons, 2019; Shaffer et al., 2017) most studies have been cross-sectional (Kent et al., 2019). Although the Actor Partner Interdependence Model can be used with cross-sectional data, the terminology (“actor effects” and “partner effects”) implies causal processes that are more appropriately modeled longitudinally. Around the time of diagnosis, the often-abrupt transition to illness may have a strong impact on both members of the dyad. Though the experience is well-described for patients, the impact on patient-caregiver dyads is less often captured and reported (Kim and Given, 2008). As patients move into treatment, support for the patient, patient-caregiver dyad, and immediate family may be highest. However, at the end of treatment and into survivorship, assistance in its many forms can wane (Merluzzi et al., 2016), leaving both members of the dyads insufficiently supported (Given et al., 2011). Well-functioning dyads with strong social support may be more resilient to these transitions, however (Lim et al., 2014). Continued investment in longitudinal research can help researchers better understand how dyad members affect each other over time, as well as their unmet needs at various points in the illness trajectory.

3.9. Social context

Illness and caregiving are situated within a social context. Our model rests on a foundation that acknowledges the effects of broad social factors on both members of the dyad, as well as their relationship processes. We discuss here the health policy environment and social determinants of health in particular, but we acknowledge that other macro-level factors—including the legal landscape, politics, and cultural factors—affect the dyadic system as well.

Health policy environment.

The fragmented, decentralized health care system in the U.S. affects patients across the cancer continuum and often impedes delivery of high quality care (Yabroff et al., 2019). The Affordable Care Act of 2010 expanded access to health insurance, especially in states that expanded Medicaid, but many patients remain uninsured or underinsured, with dire financial consequences (Yabroff et al., 2019). The Family and Medical Leave Act, passed in 1993, benefits many patients and caregivers; it allows patients, or people caring for a child, spouse, or parent, to take 12 weeks of leave if they have worked for a covered employer for at least a year (U.S. Department of Labor, 2015). This leave is unpaid, however, and does not apply to caregiving relationships that are not spousal or parent-child; in addition, many employees of small businesses are not covered (U.S. Department of Labor, 2015).

Two recent caregiving policies in the U.S. target caregivers in general but stand to benefit cancer caregivers as well. In 2014, the American Association for Retired Persons developed a model bill called the Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable (CARE) Act, which was designed to help caregivers as their loved ones go into the hospital and then as the patients transition home again (Reinhard and Ryan, 2017). As of this writing, the CARE act has been passed or enacted by 42 states and Puerto Rico. In 2018, Congress passed the Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage Family Caregivers (RAISE) Act to ensure the development of a national caregiving strategy that will give unpaid caregivers adequate access to workplace benefits, respite care, and health care (American Association for Retired Persons, 2019). The RAISE Act addresses a broad range of activities with the potential to help caregivers, including improving respite care options; providing family-centered care; addressing workplace issues and financial security; providing support for training programs and other education; and creating assessment plans to help caregivers manage their love ones’ care transitions and care coordination (American Association for Retired Persons, 2019). In conjunction with the RAISE Act, the National Academy for State Health Policy was given funding from the John A. Hartford Foundation to develop a comprehensive resource and dissemination center to help state policymakers develop and implement policies that will support family caregivers (National Academy for State Health Policy, 2019).

Additional system-level and policy-related factors that affect dyads include a lack of systematic screening and referral mechanisms for patients and caregivers experiencing high distress and/or unmet needs (Alfano et al., 2019), as well as difficulty funding caregiver interventions and integrating them into clinical care (Kent et al., 2016).

Social Determinants of Health and Social Needs.

In addition to health policy and health systems, other elements of the broader social context affect the caregiver-patient dyad as well. Link and Phelan (1995) argued that factors such as socioeconomic status are fundamental causes of a host of downstream health outcomes. These social determinants of health (SDoH) include factors such as income, education, and racism (Link and Phelan, 1995; Phelan and Link, 2015) that shape the experiences of patients and caregivers as they navigate cancer together. SDoH, which affect everyone in a population, may also lead to more proximal unmet social needs (e.g., for food, housing, or money to pay bills) (Castrucci and Auerbach, 2019). Unmet social needs among caregivers and patients may have a direct impact on the patient’s ability to carry out a care plan, as well as implications caregiving as well (Hastert et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2020). A recent review found, however, that much caregiving research to date has not addressed caregiver heterogeneity related to social determinants of health (e.g., socioeconomic status), which can impede efforts to promote health equity through caregiver screening, support, and education (Young et al., 2020). Given the overlap between many SDoH, dyadic interventions may benefit from targeting social and economic circumstances that impact overall quality of life and wellbeing for dyads while also informing more broad cultural and system-level changes.

4. Discussion, clinical applications, and call for research

The Dyadic Cancer Outcomes Framework has implications for both research and practice. Table 1 provides a list of questions suggested by the framework that can guide observational studies and intervention development.

Table 1.

Using the Dyadic Cancer Outcomes Framework to inform research and intervention development: sample questions suggested by the framework.

| Model Component | Questions for Research and Intervention Development |

|---|---|

| Patient and caregiver characteristics | What is known about the social and demographic characteristics of your patient and caregiver population? What cancer-specific factors (prognosis, treatment, etc.) are especially relevant to this population? Are there cultural factors that are important to incorporate, or key differences within your expected sample? |

| Relationship characteristics | What type of relationship do you expect most patients and caregivers in your population to have? Will there be heterogeneity across sociodemographic groups? If so, how will needs of different kinds of caregivers be addressed (e.g., caregivers who are not coresident, or who may not have a defined legal relationship to the patient)? |

| Relationship processes | What relationship process(es) does your intervention target? Do you expect those processes to be different across types of dyads? |

| Patient and caregiver outcomes | What are the primary patient and caregiver outcomes of interest? Will they be measured the same way for both members of a dyad? |

| Relationship outcomes | Are there relationship-level outcomes? How will they be assessed (observation, patient/caregiver self-report)? |

| Cancer care trajectory | Where in the cancer care trajectory will the patient be? Will there be heterogeneity among dyads, or is the intervention designed for patients at a particular time point (e.g., around the time of diagnosis, during the transition to long-term survivorship)? What is the expected course/timing of illness for most patients? Will the time points for data collection allow you to detect key changes over time? |

| Social context | What contextual factors are especially important for this population? How do policy factors affect the resources available to the dyad? How are broad social determinants of health likely to affect both dyad members? |

Observational studies.

Our framework centers the dyadic relationship, which has implications for how observational studies are designed and conducted. For example, studies using this framework should include data from both patients and caregivers. In order to use the Actor Partner Interdependence Model (Kenny et al., 2006) or other similar techniques, it is important to use the same measures for both members of the dyad, although individual-level factors (e.g., cancer stage) can be included as covariates. Our framework implies processes that unfold over time, which means that longitudinal research with multiple waves of data collection is important for understanding how patient and caregiver outcomes evolve. Techniques that use intensive longitudinal data may be especially useful for determining the time intervals over which specific changes take place.

Dyadic interventions and clinical care.

Our focus on the dyadic and social context also has implications for intervention. There has been a growing acknowledgement of the importance of screening both patients and caregivers for distress and unmet needs (Alfano et al., 2019; Badr et al., 2019); such screeners could also assess important aspects of relationships and guide clinicians in suggesting appropriate care. Our framework suggests that clinicians should pay careful attention to the social context, including different types of patient-caregiver relationships that can entail different roles, expectations, ability to provide care, access to paid time off, and access to health insurance. Beyond relationship type, relationship quality and duration also affect patient and caregiver outcomes. Acknowledging that caregiving may be remote, for example, may necessitate flexible methods of intervention delivery (e.g., telehealth). Designing dyadic interventions for heterogeneous types of dyads may be challenging because some topics (e.g., sexual functioning) maybe be very important for some dyads but not appropriate for others, but if patients can nominate the caregivers who are most important to them that may increase the real-world impact of interventions (Rush et al., 2015; Young et al., 2020)

4.1. Limitations of the framework

Although the Dyadic Cancer Outcomes Framework is designed to be flexible and apply to a range of relationships and social contexts, there are limits to its scope. It is designed to apply to adults rather than dyads that include a minor child. We have included many types of predictor and outcome variables in the framework to acknowledge the range of factors being studied among patient-caregiver dyads, but it is unlikely that any one observational or intervention study would include all the potential predictors, outcomes, or processes included here. Instead, this framework can be used to help intervention developers consider which specific elements of the social context or dyadic relationship are most important to focus on. In addition, patients may draw on support from many different family and friends, and thus there may be contexts in which the dyad is not the most appropriate unit of analysis or target for intervention.

5. Conclusion

Caregiver-patient relationships take many forms, and the pathways through which patients and caregivers affect each other’s health are varied and complex. Although this heterogeneity provides challenges for researchers, it can also be a source of strength for patients as they choose which key relationships to rely on for support during active treatment and into long-term survivorship. The Dyadic Cancer Outcomes Framework, which draws on past theoretical work that recognizes the importance of the dyad in adaptation to cancer, is designed to apply to a range of relationship types. We include several predictors and outcomes, as well as contextual factors such as culture, the policy landscape, and social determinants of health that affect the care and resources available to patients and caregivers. Our hope is that this framework will help generate research and interventions to improve the lives of people with cancer and their caregivers.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Thompson was supported by a Mentored Research Scholar Grant from the American Cancer Society (MRSG-19-086-01-CPPB, PI: Thompson). Dr. Ketcher was funded through the National Cancer Institute (5T32CA090314-16). Dr. Gray was supported by the Cambia Health Foundation Sojourns Scholar Leadership Program and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholars Program. The authors would like to acknowledge the Harvard Research Methods in Supportive Oncology Workshop (NCI R25 CA 181000), where they developed the idea for this paper.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Abbott-Anderson K, Kwekkeboom KL 2012. A systematic review of sexual concerns reported by gynecological cancer survivors. Gynecol. Oncol 124, 477–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizer AA, Chen M-H, McCarthy EP, Mendu ML, Koo S, Wilhite TJ, et al. , 2013. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol 31, 3869–3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfano CM, Leach CR, Smith TG, Miller KD, Alcaraz KI, Cannady RS, et al. ,2019. Equitably improving outcomes for cancer survivors and supporting caregivers: a blueprint for care delivery, research, education, and policy. CA A Cancer J. Clin 69, 35–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association for Retired Persons, 2019. RAISE Family Caregivers Act Promises Federal Help. https://www.aarp.org/politics-society/advocacy/caregiving-advocacy/info-2015/raise-family-caregivers-act.html.

- American Association for Retired Persons, N.A.F.C., 2020. Caregiving in the United States 2020 (Washington, DC: ). [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society, 2019. Cancer Facts and Figures. American Cancer Society, Atlanta. [Google Scholar]

- Badr H, 2017. New frontiers in couple-based interventions in cancer care: refining the prescription for spousal communication. Acta Oncol. 56, 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr H, Acitelli LK, 2017. Re-thinking dyadic coping in the context of chronic illness. Current Opinion in Psychology 13, 44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr H, Bakhshaie J, Chhabria K, 2019. Dyadic interventions for cancer survivors and caregivers: state of the science and new directions. Semin. Oncol. Nurs 35, 337–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr H, Krebs P, 2013. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for couples coping with cancer. Psycho Oncol. 22, 1688–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baider L, Surbone A, 2014. Universality of aging: family caregivers for elderly cancer patients. Front. Psychol 5, 744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CA, Upchurch R, 2007. A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychol. Bull 133, 920–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger AM, Parker KP, Young-McCaughan S, Mallory GA, Barsevick AM, Beck SL, et al. , 2005. Sleep/wake disturbances in people with cancer and their caregivers: state of the science. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 32, E98–E124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry LL, Dalwadi SM, Jacobson JO, 2017. Supporting the supporters: what family caregivers need to care for a loved one with cancer. Journal of Oncology Practice 13, 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan JL, Pecchioni LL, 2008. Understanding the impact of family caregiver cancer literacy on patient health outcomes. Patient Educ. Counsel 71, 356–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigatti SM, Wagner CD, Lydon-Lam JR, Steiner JL, Miller KD, 2011. Depression in husbands of breast cancer patients: relationships to coping and social support. Support. Care Canc 19, 455–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, 2016. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Edpidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 25, 1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, 2005. Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In: Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G (Eds.), Couples Coping with Stress: Emerging Perspectives on Dyadic Coping. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Brandão T, Schulz MS, Matos PM, 2017. Psychological adjustment after breast cancer: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Psycho Oncol. 26, 917–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagle JG, Munn JC, 2012. Long-distance caregiving: a systematic review of the literature. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 55, 682–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrucci B, Auerbach J, 2019. Meeting individual social needs falls short of addressing social determinants of health. Health Affairs Blog 10. [Google Scholar]

- Chan RJ, Gordon LG, Tan CJ, Chan A, Bradford NK, Yates P, et al. , 2019. Relationships between financial toxicity and symptom burden in cancer survivors: a systematic review. J. Pain Symptom Manag 57, 646–660 e641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung SY, Delfabbro P, 2016. Are you a cancer survivor? A review on cancer identity. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 10, 759–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi N-C, Demiris G, 2015. A systematic review of telehealth tools and interventions to support family caregivers. J. Telemed. Telecare 21, 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa DSJ, Mercieca-Bebber R, Tesson S, Seidler Z, Lopez AL, 2019. Patient, client, consumer, survivor or other alternatives? A scoping review of preferred terms for labelling individuals who access healthcare across settings. BMJ Open 9, e025166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coumoundouros C, Ould Brahim L, Lambert SD, McCusker J, 2019. The direct and indirect financial costs of informal cancer care: a scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community 27, e622–e636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas SL, Mazanec P, Lipson A, Leuchtag M, 2016. Distance caregiving a family member with cancer: a review of the literature on distance caregiving and recommendations for future research. World J. Clin. Oncol 7, 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle KL, Toepfer M, Bradfield AF, Noffke A, Ausderau KK, Andreae S, 2020. Systematic review of exercise for caregiver–care recipient dyads: what is best for spousal caregivers—exercising together or not at all? Gerontol. 10.1093/geront/gnaa043 gnaa043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eifert EK, Adams R, Dudley W, Perko M, 2015. Family caregiver identity: a literature review. Am. J. Health Educ 46, 357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis KR, Janevic MR, Kershaw T, Caldwell CH, Janz NK, Northouse L, 2017. Engagement in health-promoting behaviors and patient–caregiver interdependence in dyads facing advanced cancer: an exploratory study. J. Behav. Med 40, 506–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconier MK, Kuhn R, 2019. Dyadic coping in couples: a conceptual integration and a review of the empirical literature. Front. Psychol 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher BS, Miaskowski C, Given B, Schumacher K, 2012. The cancer family caregiving experience: an updated and expanded conceptual model. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs 16, 387–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry R, 2017. The share of Americans living without a partner has increased, especially among young adults. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/10/11/the-share-of-americans-living-without-a-partner-has-increased-especially-among-young-adults.

- Girgis A, Lambert S, Johnson C, Waller A, Currow D, 2013. Physical, psychosocial, relationship, and economic burden of caring for people with cancer: a review. Journal of Oncology Practice 9, 197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Given BA, Sherwood P, Given CW, 2011. Support for caregivers of cancer patients: transition after active treatment. Canc. Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 20, 2015–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JR, Baik SH, Schwartz KT, Wells KJ, 2019. Comparing the mental health of sexual minority and heterosexual cancer survivors: a systematic review. LGBT Health 6, 271–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer JA, Applebaum AJ, Jacobsen JC, Temel JS, Jackson VA, 2020. Understanding and addressing the role of coping in palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. J. Clin. Oncol 38, 915–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tuinstra J, Coyne JC, 2008. Distress in couples coping with cancer: a meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol. Bull 134, 1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbach SM, Ernstmann N, Kowalski C, Pfaff H, Pfoertner T-K, Wesselmann S, et al. , 2016. Unmet information needs and limited health literacy in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients over the course of cancer treatment. Patient Educ. Counsel 99, 1511–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton LD, Van Dam D, Wassersug RJ, 2016. The perspective of prostate cancer patients and patients’ partners on the psychological burden of androgen deprivation and the dyadic adjustment of prostate cancer couples. Psycho Oncol. 25, 823–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, Todd BL, Feuerstein M, 2010. It’s not over when it’s over: long-term symptoms in cancer survivors-a systematic review. Int. J. Psychiatr. Med 40, 163–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson-Ohayon I, Goldzweig G, Braun M, Galinsky D, 2010. Women with advanced breast cancer and their spouses: diversity of support and psychological distress. Psycho Oncol. 19, 1195–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastert TA, McDougall JA, Strayhorn SM, Nair M, Beebe-Dimmer JL, Schwartz AG, 2021. Social needs and health-related quality of life among African American cancer survivors: results from the Detroit Research on Cancer Survivors study. Cancer 127, 467–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz J, Graf N, Livingston G, 2019. Marriage and Cohabitation in the U.S. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/11/PSDT_11.06.19_marriage_cohabitation_FULL.final_.pdf.

- Hunt GG, Longacre ML, Kent EE, Weber-Raley L, 2016. Cancer Caregiving in the U.S.: an Intense, Episodic, and Challenging Experience. National Alliance for Caregiving. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, 2005. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Ji J, Zöller B, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, 2012. Increased risks of coronary heart disease and stroke among spousal caregivers of cancer patients. Circulation 125, 1742–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose O, Alfons V, 2007. Do demographics affect marital satisfaction? J. Sex Marital Ther 33, 73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamen C, Heckler C, Janelsins MC, Peppone LJ, McMahon JM, Morrow GR, et al. , 2016. A dyadic exercise intervention to reduce psychological distress among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual cancer survivors. LGBT Health 3, 57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HS, Kim H-K, Park SM, Kim J-H, 2018. Online-based interventions for sexual health among individuals with cancer: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res 18, 167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Shin DW, Choi JE, Sanjo M, Yoon SJ, Kim HK, et al. , 2013. Factors associated with positive consequences of serving as a family caregiver for a terminal cancer patient. Psycho Oncol. 22, 564–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser K, Acquati C, Reese JB, Mark K, Wittmann D, Karam E, 2018. A systematic review of dyadic studies examining relationship quality in couples facing colorectal cancer together. Psycho Oncol. 27, 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley DE, Kent EE, Litzelman K, Mollica MA, Rowland JH, 2019. Dyadic associations between perceived social support and cancer patient and caregiver health: an actor-partner interdependence modeling approach. Psycho Oncol. 28, 1453–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL, 2006. Dyadic Data Analysis. The Guilford Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Kent EE, Mollica MA, Buckenmaier S, Smith AW, 2019. The characteristics of informal cancer caregivers in the United States. Semin. Oncol. Nurs 35, 328–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, Litzelman K, Chou WYS, Shelburne N, et al. , 2016. Caring for caregivers and patients: research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer 122, 1987–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Wilson SJ, 2017. Lovesick: how couples’ relationships influence health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol 13, 421–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Baker F, Spillers RL, Wellisch DK, 2006. Psychological adjustment of cancer caregivers with multiple roles. Psycho Oncol. 15, 795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Carver CS, Rocha-Lima C, Shaffer KM, 2013. Depressive symptoms among caregivers of colorectal cancer patients during the first year since diagnosis: a longitudinal investigation. Psycho Oncol. 22, 362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Given BA, 2008. Quality of life of family caregivers of cancer survivors: across the trajectory of the illness. Cancer 112, 2556–2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly C, Williams A, 2017. Decade review of research on lesbian romantic relationship satisfaction. J. LGBT Issues Couns 11, 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Knight BG, Sayegh P, 2010. Cultural values and caregiving: the updated sociocultural stress and coping model. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci 65B, 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke CH, 2018. A conceptual model of social networks and mechanisms of cancer mortality, and potential strategies to improve survival. Translational Behavioral Medicine 8, 629–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer SL, Brown JD, Syrjala KL, 2009. Intrapersonal and interpersonal consequences of protective buffering among cancer patients and caregivers. Cancer 115, 4311–4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Lyons KS, 2019. Patterns, relevance, and predictors of dyadic mental health over time in lung cancer. Psycho Oncol. 28, 1721–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, McBride CM, Poliak KI, Puleo E, Butterfield RM, Emmons KM, 2006. Understanding health behavior change among couples: an interdependence and communal coping approach. Soc. Sci. Med 62, 1369–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Chan CWH, Chow KM, Xiao J, Choi KC, 2020. A systematic review and meta-analysis of couple-based intervention on sexuality and the quality of life of cancer patients and their partners. Support. Care Canc 28, 1607–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Loke AY, 2014a. A systematic review of spousal couple-based intervention studies for couples coping with cancer: direction for the development of interventions. Psycho Oncol. 23, 731–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Mak YW, Loke A, 2013. Spouses’ experience of caregiving for cancer patients: a literature review. Int. Nurs. Rev 60, 178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li QP, Loke AY, 2014b. A literature review on the mutual impact of the spousal caregiver-cancer patients dyads: ‘communication’, ‘reciprocal influence’, and ‘caregiver-patient congruence’. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs 18, 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillie HM, Venetis MK, Chernichky-Karcher SM, 2018. “He would never let me just give up”: communicatively constructing dyadic resilience in the experience of breast cancer. Health Commun. 33, 1516–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JW, Shon EJ, Paek M, Daly B, 2014. The dyadic effects of coping and resilience on psychological distress for cancer survivor couples. Support. Care Canc 22, 3209–3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J, 1995. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J. Health Soc. Behav 80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litzelman K, Kent EE, Rowland JH, 2016. Social factors in informal cancer caregivers: the interrelationships among social stressors, relationship quality, and family functioning in the CanCORS data set. Cancer 122, 278–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litzelman K, Kent EE, Rowland JH, 2018. Interrelationships between health behaviors and coping strategies among informal caregivers of cancer survivors. Health Educ. Behav 45, 90–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK, 2011. Biobehavioral factors and cancer progression: physiological pathways and mechanisms. Psychosom. Med 73, 724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magsamen-Conrad K, Checton MG, Venetis MK, Greene K, 2015. Communication efficacy and couples’ cancer management: applying a dyadic appraisal model. Commun. Monogr 82, 179–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiorino MI, Chiodini P, Bellastella G, Giugliano D, Esposito K, 2016. Sexual dysfunction in women with cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis of studies using the Female Sexual Function Index. Endocrine 54, 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Badr H, 2008. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer 112, 2541–2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall CA, Larkey LK, Curran MA, Weihs KL, Badger TA, Armin JG, Francisco, 2011. Considerations of culture and social class for families facing cancer: the need for a new model for health promotion and psychosocial intervention. Fam. Syst. Health 29, 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez YC, Ellington L, Vadaparampil ST, Heyman RE, Reblin M, 2020. Concordance of cancer related concerns among advanced cancer patient–spouse caregiver dyads. J. Psychosoc. Oncol 38, 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor S, 2018. Conceptual and theoretical papers. Understanding and Evaluating Research: A Critical Guide. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, California, pp. 497–528. [Google Scholar]

- Merluzzi TV, Philip EJ, Yang M, Heitzmann CA, 2016. Matching of received social support with need for support in adjusting to cancer and cancer survivorship. Psycho Oncol. 25, 684–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Sze J, Marin T, Arevalo JM, Doll R, et al. , 2008. A functional genomic fingerprint of chronic stress in humans: blunted glucocorticoid and increased NF-κB signaling. Biol. Psychiatr 64, 266–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, et al. , 2019. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA A Cancer J. Clin 69, 363–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine., 2016. In: Families Caring for an Aging America. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academy for State Health Policy, 2019. The RAISE Family Caregiver Resource and Dissemination Center. From. https://www.nashp.org/the-raise-family-caregiver-resource-and-dissemination-center/.

- Newcomb ME, 2020. Romantic relationships and sexual minority health: a review and description of the dyadic health model. Clin. Psychol. Rev 82, 101924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse L, Williams A.-l., Given B, McCorkle R, 2012. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol 30, 1227–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa CY, Lunsford NB, Smith JL, 2020. Impact of informal cancer caregiving across the cancer experience: a systematic literature review of quality of life. Palliat. Support Care 18, 220–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto AK, Ketcher D, Heyman RE, Vadaparampil ST, Ellington L, Reblin M, 2020. Communication between Advanced Cancer Patients and Their Family Caregivers: Relationship with Caregiver Burden and Preparedness for Caregiving. Health Communication, pp. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod J, Baney B, Loeb SJ, McGhan G, Shipley PZ, 2012. The influence of the culture of care on informal caregivers’ experiences. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science 35, 64–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Link BG, 2015. Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annu. Rev. Sociol 41, 311–330. [Google Scholar]

- Pietromonaco PR, Uchino B, Dunkel Schetter C, 2013. Close relationship processes and health: implications of attachment theory for health and disease. Health Psychol. 32, 499–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, 2010. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol 75, 122–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Baucom DH, Olsen M, Zafar SY, Uronis H, 2017. A randomized pilot trial of a videoconference couples communication intervention for advanced GI cancer. Psycho Oncol. 26, 1027–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puts M, Papoutsis A, Springall E, Tourangeau A, 2012. A systematic review of unmet needs of newly diagnosed older cancer patients undergoing active cancer treatment. Support. Care Canc 20, 1377–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek C, 2012. The promotion of unhealthy habits in gay, lesbian, and straight intimate partnerships. Soc. Sci. Med 75, 1114–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese JB, Sorice K, Beach MC, Porter LS, Tulsky JA, Daly MB, et al. , 2017. Patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in cancer: a systematic review, 11, 175–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan TW, Lambert SD, Girgis A, Kelly B, Kayser K, Turner J, 2012. Do couple-based interventions make a difference for couples affected by cancer? A systematic review. BMC Canc 12, 279–2407, 2412-2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard SC, Ryan E, 2017. From home alone to the CARE Act: collaboration for family caregivers. American Association for Retired Persons. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2017/08/from-home-alone-to-the-care-act.pdf.

- Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, McGinn MM, 2014. Marital quality and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull 140–187, 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohleder N, Marin TJ, Ma R, Miller GE, 2009. Biologic cost of caring for a cancer patient: dysregulation of pro-and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways. J. Gin. Oncol 27, 2909–2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romito F, Goldzweig G, Cormio C, Hagedoorn M, Andersen BL, 2013. Informal caregiving for cancer patients. Cancer 119, 2160–2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A, Sundaramurthi T, Bevans M, 2013. A labor of love: the influence of cancer caregiving on health behaviors. Canc. Nurs 36, 474–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CL, Darling M, Elliott MG, Febus-Sampayo I, Kuo C, Muñoz J, et al. , 2015. Engaging Latina cancer survivors, their caregivers, and community partners in a randomized controlled trial: Nueva Vida intervention. Qual. Life Res 24, 1107–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Iglesias P, Rana M, Walker LM, 2020. A systematic review of sexual satisfaction in prostate cancer patients. Sexual Medicine Reviews 8, 450–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarfati D, Koczwara B, Jackson C, 2016. The impact of comorbidity on cancer and its treatment. CA A Cancer J. clin 66, 337–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer KM, Kim Y, Carver CS, Cannady RS, 2017. Effects of caregiving status and changes in depressive symptoms on development of physical morbidity among long-term cancer caregivers. Health Psychol. 36, 770–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer KM, Kim Y, Llabre MM, Carver CS, 2016. Dyadic associations between cancer-related stress and fruit and vegetable consumption among colorectal cancer patients and their family caregivers. J. Behav. Med 39, 75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankardass K, Robertson C, Shaughnessy K, Sykora M, Feick R, 2019. A unified ecological framework for studying effects of digital places on well-being. Soc. Sci. Med 227, 119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL, 1991. The MOS social support survey. Soc. Sci. Med 32, 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin DW, Shin J, Kim SY, Yang H-K, Cho J, Youm JH, et al. , 2016. Family avoidance of communication about cancer: a dyadic examination. Cancer Research and Treatment 48, 384–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JY, Kang TI, Noll RB, Choi SW, 2018. Supporting caregivers of patients with cancer: a summary of technology-mediated interventions and future directions. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 38, 838–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A, 2020. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA A Cancer J. Clin 70, 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira MJ, Given CW, Given B, Rosland AM, Piette JD, 2010. Patient-caregiver concordance in symptom assessment and improvement in outcomes for patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy. Chron. Illness 6, 46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siminoff LA, Wilson-Genderson M, Barta S, Thomson MD, 2020. Hematological cancer patient-caregiver dyadic communication: a longitudinal examination of cancer communication concordance. Psycho Oncol. 29, 1571–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Northouse L, Zhang L, Braun TM, Cimprich B, Ronis DL, et al. , 2012. Study of dyadic communication in couples managing prostate cancer: a longitudinal perspective. Psycho Oncol. 21, 72–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streck BP, LoBiondo-Wood G, 2020. A systematic review of dyadic studies examining depression in couples facing breast cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol 38, 463–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streck BP, Wardell DW, LoBiondo-Wood G, Beauchamp JE, 2020. Interdependence of physical and psychological morbidity among patients with cancer and family caregivers: review of the literature. Psycho Oncol. 10.1002/pon.5382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stulz A, Lamore K, Montalescot L, Favez N, Flahault C, 2020. Sexual health in colon cancer patients: a systematic review. Psycho Oncol. 29, 1095–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter EA, Bergen KM, Daas KL, Durham WT, 2006. Lesbian couples’ management of public-private dialectical contradictions. J. Soc. Pers. Relat 23, 349–365. [Google Scholar]

- Syrowatka A, Motulsky A, Kurteva S, Hanley JA, Dixon WG, Meguerditchian AN, et al. , 2017. Predictors of distress in female breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Breast Canc. Res. Treat 165, 229–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennstedt SL, Crawford S, McKinlay JB, 1993. Determining the pattern of community care: is coresidence more important than caregiver relationship? J. Gerontol 48, S74–S83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA, 2011. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav 52, 145–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L, Walker AJ, 1982. The dyad as the unit of analysis: conceptual and methodological issues. J. Marriage Fam 889–900. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson T, Heiden-Rootes K, Joseph M, et al. , 2020. The support that partners or caregivers provide sexual minority women who have cancer: a systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traa MJ, Braeken J, De Vries J, Roukema JA, Slooter GD, Crolla RM, et al. , 2015a. Sexual, marital, and general life functioning in couples coping with colorectal cancer: a dyadic study across time. Psycho Oncol. 24, 1181–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traa MJ, De Vries J, Bodenmann G, Den Oudsten BL, 2015b. Dyadic coping and relationship functioning in couples coping with cancer: a systematic review. Br. J. Health Psychol 20, 85–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor, 2015. Need Time? the Employee’s Guide to the Family Medical Leave Act. From. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/WHD/legacy/files/employeeguide.pdf.

- Uchino BN, 2009. Understanding the links between social support and physical health: a life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspect. Psychol. Sci 4, 236–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Donnelly R, Pollitt AM, 2018. Marriage, social control, and health behavior: a dyadic analysis of same-sex and different-sex couples. J. Health Soc. Behav 59, 429–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ryn M, Sanders S, Kahn K, van Houtven C, Griffin JM, Martin M, et al. , 2011. Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: a hidden quality issue? Psycho Oncol. 20, 44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Augustson E, Atienza AA, 2011. Smoking concordance in lung and colorectal cancer patient-caregiver dyads and quality of life. Canc. Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 20, 239–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL, Freedman VA, Mulcahy JF, Kasper JD, 2020. Family caregivers’ experiences with health care workers in the care of older adults with activity limitations. JAMA Network Open 3, e1919866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabroff KR, Gansler T, Wender RC, Cullen KJ, Brawley OW, 2019. Minimizing the burden of cancer in the United States: goals for a high-performing health care system. CA A Cancer J. clin 69, 166–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young HM, Bell JF, Whitney RL, Ridberg RA, Reed SC, Vitaliano PP, 2020. Social determinants of health: underreported heterogeneity in systematic reviews of caregiver interventions. Gerontol. 60, S14–S28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Jemal A, Tucker-Seeley R, Banegas MP, Han X, Rai A, et al. , 2020. Worry about daily financial needs and food insecurity among cancer survivors in the United States. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw 18, 315–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]