Abstract

Objective

In surgery, dysfunctional teamwork is perpetuated by a ‘silo’ mentality modelled by students. Interprofessional education using high-fidelity simulation-based training (SBT) may counteract such modelling. We sought to determine whether SBT of interprofessional student teams (1) changes long-term teamwork attitudes and (2) is an effective form of team training.

Design

A quasiexperimental, pre/postintervention comparison design was employed at an academic health sciences institution. High-fidelity simulation-based training of 42 interprofessional teams of third year surgery clerkship medical students and senior undergraduate nursing students was undertaken using a two-scenario format with immediate after action debriefing. Pre/postintervention TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitudes questionnaires (5 subscales, 30 items, Likert type) were given to the medical student and undergraduate nursing student classes. Pre/postsession Readiness for Inter-Professional Learning (RIPL; 19 items, Likert type) surveys and postscenario participant-rated and observer-rated Teamwork Assessment Scales (3 subscales, 11 items, Likert type) were given during each training session. Mean TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire, RIPL and Teamwork Assessment Scales scores were calculated; matched pre/postscore differences and trained versus non-trained TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire scores were compared using paired t-test or analysis of variance.

Results

Both student groups had 10 significantly improved RIPL items as well as TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire (TTAQ) mutual support subscales. Medical students had a significantly improved TTAQ team structure subscale. Over a simulation-based training session, each observer-rated Teamwork Assessment Scales subscale and two self-rated Teamwork Assessment Scales subscales significantly improved. Trained students had significantly higher TTAQ team structure subscales than non-trained students.

Conclusions

Interprofessional education using high-fidelity simulation-based training of students is effective at teaching teamwork, changing interprofessional attitudes and improving long-term teamwork attitudes.

Keywords: simulation, inter-professional education, teamwork, surgery, undergraduate medical education

Introduction

The ‘hidden curriculum’ remains a subversive force in healthcare professional education with students modelling the interprofessional friction and ‘silo mentality’.1 Students, therefore, learn to work ‘with’ each other as a ‘team of experts’ rather than ‘for’ each other as an ‘expert team’.2 3 Healthcare educators have attempted to counteract this pernicious effect by increasing opportunities for interprofessional education (IPE) among the different undergraduate student populations. IPE does impact positively students’ attitudes towards team-working skills4 and has positive effects in the clinical environment.5 The Lucien Leape Institute has emphasised more IPE with simulation-based training (SBT) to foster better teamwork and innovative healthcare redesign.6 In fact, interprofessional collaborative practice is now recognised as a critical component of modern-day healthcare.7 8 The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) has identified four such domains: (1) values/ethics for interprofessional practice, (2) roles/responsibilities, (3) interprofessional communication and (4) teams and teamwork.9

High-fidelity SBT provides a safe learning environment in which students can learn from ‘mistakes’ without repercussions.10 It draws on Kolb’s theory of experiential learning11 to allow learners to (1) undergo a concrete experience via a simulated clinical scenario, (2) reflect on that experience in the postaction debriefing, (3) draw abstract lessons as a result of the reflective debriefing and (4) apply the knowledge, skills and attitudes (KSAs) learnt to actual clinical practice. When applied to teamwork in an IPE setting, participants have the opportunity to model and experience positive team-based KSAs. This high-fidelity SBT also incorporates aspects of Vygotsky’s theory of social constructivism12 in which learning is enhanced by collaboration with peers and near peers. Accurate assessment of participants’ own abilities, therefore, is crucial for optimising learning. Professional students, however, do poorly with self-appraisal,13 an incongruity noted among senior students undergoing SBT as operating room (OR) teams.14

Challenges to successful IPE implementation are manifold and include, among other things, curricular issues related to timing, scheduling and content.15 As a result, successful integration of IPE courses into the curricula of different health professional schools can become complicated quickly, resulting in less than ideal solutions such as large-scale mass training events16 or other projects.17 18 In fact, a lack of structured team-based curricula embedded in training has been identified as a gap in surgical simulation research.19 In addition, logistical issues have been cited as a major problem in implementation of surgical simulation research.19 With this research, we have attempted to address both topics. At LSU Health New Orleans, we integrated high-fidelity SBT in teamwork using IPE into the curricula of two existing course structures at the Schools of Medicine and Nursing to determine whether such interprofessional, student-based SBT changed behaviour over the course of the academic year by impacting teamwork attitudes. Secondarily, we wanted to determine whether SBT was an effective form of student team training for learning key KSAs related to team-based competencies and breaking down preconceived biases.

Methods

Study design

A quasiexperimental pre/postintervention comparison design was used. Students completed evaluations before and after the educational intervention. Prior exempted institutional review board approval was obtained.

Training setting

Training occurred at a large, urban academic health sciences centre.20 A full-scale, computer-operated human patient simulator manikin (CAE, Montreal, Canada) was used. Equipment for trauma resuscitation was present. Sessions were recorded using METI Vision (CAE, Montreal, Canada).

Training format

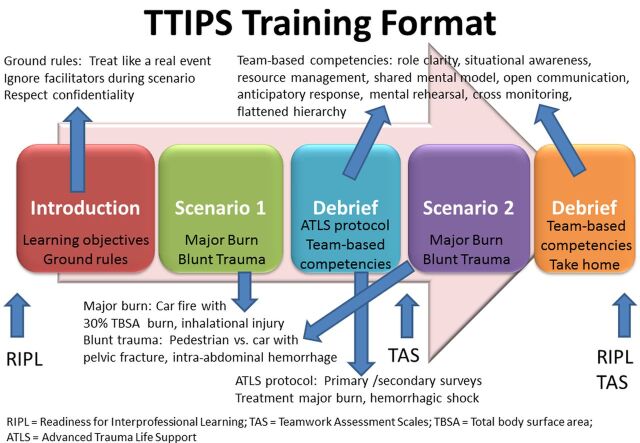

The training format was similar to prior in situ21 and ex cura14 (ie, centre-based) high-fidelity SBT curricula at LSU Health New Orleans (figure 1). It utilised a 2-hour dual scenario format with immediate structured debriefing employing several techniques.22–26 It stressed the management of major trauma patients and nine team-based competencies (ie, shared mental model, role clarity, situational awareness, anticipatory response, resource management, open communication, cross monitoring, flattened hierarchy and mental rehearsal). The summary elicited a commitment from each participant to practise/adopt at least one of these competencies in clinical practice.

Figure 1.

TTIPS training format. TTIPS, Team Training of Inter-Professional Students.

Three instructors typically led each session. One instructor (VR) operated the computer-based manikin; two (DG, JP) facilitated the debriefings. Instructors also served as raters of team-based behaviours immediately after each scenario (DG, JP). A second rating was obtained using video review of the scenario if only one facilitator was present at the original training session.

Training participants

Third year medical students on their surgery clerkship and senior undergraduate nursing students taking an intensive care course participated. Teams had three to eight students with at least two undergraduate nursing students and one medical student, comprising 213 members in 42 teams. Due to the incongruous schedules of the Schools of Medicine and Nursing and the large size of the nursing classes, not all third year medical and senior undergraduate nursing students were able to participate in the SBT interprofessional team training.

Each team member assumed one of five main roles during the scenario: (1) primary nurse; (2) medication nurse; (3) chief resident; (4) airway physician and (5) intern physician. For teams with greater than five members, an attending physician role, an additional resident role and another intern role were added. For teams with less than five members, the intern and airway roles were dropped for teams of four and three members, respectively. Roles would be reversed among the undergraduate nursing students and interchanged among the medical students after the first scenario.

Training scenarios

Two authentic, standardised trauma resuscitation training scenarios were adapted from the existing third year medical student surgery clerkship SBT curriculum for the team training. Scenario 1 involved resuscitation of a 30% total body surface area burn victim. Scenario 2 involved a blunt trauma victim with intra-abdominal haemorrhage and pneumothorax. These scenarios used a software algorithm developed inhouse.14 21

Evaluation

Evaluation followed Kirkpatrick’s model of training effectiveness.27 Level 1 (ie, participant reaction) effectiveness was evaluated qualitatively via inquiry of participants at the conclusion of each training session. Questioning focused on whether the SBT was worthwhile, why or why not, and how to improve it.

Level 2 (ie, participant learning) effectiveness was evaluated in two ways. First, individual team-based and overall performance was assessed using the Teamwork Assessment Scales (TAS), a tool with evidence of generalisabilty14 and convergent validity.28 The TAS is an 11-item, two-scale instrument using a Likert-type rating system (1 = definitely no to 6 = definitely yes). The first scale comprises a five-item multisource evaluation (MSE) for team-based behaviours (TBB); the second scale is an overall teamwork evaluation divided into a three-item shared mental model (SMM) subscale and a three-item adaptive communication and response (ACR) subscale. Participants performed self-based, peer-based and overall team-based evaluations after each scenario using the TAS. Peer-based evaluations involved participants rating every other member of the team using the MSE TBB scale. Two observers rated individual-based and team-based performances after each scenario (ie, after both the first and second scenario for each training session). Ratings were either real time, or, in cases with only one facilitator, the second was completed via video review. Mean subscale scores were calculated for observer and participant ratings. If participants attended more than one SBT during the period, the first training episode was used. Differences between mean calculated observer-rated and participant-rated performances after each scenario were evaluated using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Second, interprofessional attitudes were evaluated before and immediately after each training session using the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning (RIPL) questionnaire,29 a 19-item instrument employing a Likert-type scale that has undergone modification.30 31 Students completed the RIPL just prior to each training session and immediately following the completion of the after-action debriefing of the second scenario. Mean subscale scores were calculated for each RIPL item. If participants attended more than one SBT during the period, the first training episode was used. Matched pre/post-training item scores were compared using paired t-test with Bonferroni correction.

Finally, Level 3 (ie, change in participant behaviour) effectiveness was measured via administration of the TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitude Questionnaire (TTAQ) to the entire third year medical student and senior undergraduate nursing classes at the beginning and end of their academic years. In this manner, changes in teamwork attitudes would reflect behavioural changes removed from the immediate SBT experience. For medical students, the survey was completed at the time of their annual registration meeting for matriculation as third year students (ie, June 2011) and fourth year students (ie, June 2012). For senior undergraduate nursing students, the TTAQ was administered at the start of their senior year of training (ie, August 2011 or January 2012) and at the end of their senior year (ie, April 2012 or December 2012). The TTAQ is a 30-item survey using a Likert-type scale divided into five subscales of six questions each: (1) team structure; (2) leadership; (3) situation monitoring; (4) mutual support and (5) communication. It has undergone extensive psychometric testing.32 Mean matched TTAQ subscale pre/postscores were calculated for all students. Pre/postsubscale scores for students undergoing the SBT were calculated for each professional group. In addition, the differences in matched pre/postsubscale scores were calculated for those students who underwent SBT and those who did not and compared using one-way ANOVA. In this manner, students who did not undergo SBT due to logistical reasons cited under the Training participants section served as a control group for measuring teamwork attitudes over time.

For all data analysis, an ad hoc method was employed in which any incomplete paired data set was discarded prior to comparison.

Results

Participant breakdown

Overall, 42 SBT sessions were held: 20 sessions in the fall semester and 22 in the spring semester. For the fall sessions, the number of medical students for each session ranged from one to four (one student—one session; two students—five sessions; three students—10 sessions; four students—four sessions). For the spring sessions, the number of medical students for each session ranged from one to six (one student—one session; two students—four sessions; three students—10 sessions; four students—six sessions; five students—no sessions; six students—one session). Two senior undergraduate nursing students participated in every session for both semesters of training. Data were available for analysis of 187 first time participants, of which 103 were first-time training medical students, 76 were first-time training undergraduate nursing students, and four were unidentified based on professional status.

Participant reaction

Participating medical students and undergraduate nursing students affirmed that the SBT experience was worthwhile when queried orally at the end of a training session. Comments related to its worthwhile nature centred around three themes: (1) clinical experience; (2) autonomy and (3) interprofessional collaboration. Students appreciated the opportunity to practise clinical KSAs related to performing the resuscitation of a major trauma patient according to the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol. They felt that this experience revealed gaps in learning that could be addressed prior to the actual treatment of a trauma patient. In addition, they liked being ‘put in charge’ of the care of a patient. This autonomy in the SBT revealed the difference between passive care involvement of a patient versus actively ‘calling the shots.’ Finally, students expressed a satisfaction in working with members of another healthcare profession as part of their curricular programme in their respective school. They felt that it helped build bridges and clarify roles.

Participant learning—Teamwork Assessment Scales

Matched observer ratings of both scenarios were available for 168 TBB scores and 151 overall teamwork scores. Matched self-assessment ratings were available for 101 TBB scores and 99 overall teamwork scores. Matched peer assessment scores were available for 509 TBB and overall teamwork scores.

Self-based, peer-based, and observer-based mean scores and differences for components of the TAS are listed in tables 1–3, respectively. Mean scores were higher on self-based and peer-based ratings compared with observer-based scores. Observer-based ratings of participants demonstrated a statistically significant improvement on every subscale from scenario 1 to scenario 2.

Table 1.

Summary of participant self-rated TAS subscale analysis for simulation-based Team Training of Inter-Professional Students: scenario 1 versus scenario 2

| TAS subscales | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | ||||||||

| N | Mean* | SD | Cronbach’s alpha | N | Mean* | SD | Cronbach’s alpha | Change† | p Value‡ | |

| TBB§ | 101 | 5.16 | 0.81 | 0.750 | 101 | 5.31 | 0.75 | 0.950 | 0.16 | 0.067 |

| SMM** | 99 | 4.64 | 1.01 | 0.947 | 99 | 5.42 | 0.70 | 0.938 | 0.78 | <0.001 |

| ACR¶ | 99 | 4.46 | 1.20 | 0.712 | 99 | 5.20 | 0.84 | 0.502 | 0.75 | <0.001 |

*Mean combined score of third year medical and senior undergraduate nursing students.

†Scenario 2—scenario 1.

‡One-way ANOVA.

§TBB, Team-Based Behaviors, subscale assessing individual performance (five items; multisource evaluation).

**SMM, Shared Mental Model, subscale of overall teamwork (three items).

¶ACR, Adaptive Communication and Response, subscale of overall teamwork (three items).

ANOVA, analysis of variance; TAS, Teamwork Assessment Scale; TBB, Team-Based Behaviour.

Table 2.

Summary of participant peer-rated TAS subscale analysis for simulation-based Team Training of Inter-Professional Students: scenario 1 versus scenario 2

| TAS subscales | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | ||||||||

| N | Mean* | SD | Cronbach’s alpha | N | Mean* | SD | Cronbach’s alpha | Change† | p Value‡ | |

| TBB§ | 509 | 6.09 | 4.86 | 0.725 | 509 | 5.89 | 2.39 | 0.473 | −0.20 | 0.400 |

| SMM** | 509 | 4.70 | 1.02 | 0.952 | 509 | 5.49 | 0.67 | 0.937 | 0.79 | <0.001 |

| ACR¶ | 509 | 5.51 | 6.86 | 0.713 | 509 | 5.74 | 3.95 | 0.505 | 0.24 | 0.443 |

*Mean combined score of third year medical and senior undergraduate nursing students.

†Scenario 2—scenario 1.

‡One-way ANOVA.

§TBB, Team-Based Behaviors, subscale assessing individual performance (five items; multisource evaluation).

**SMM, Shared Mental Model, subscale of overall teamwork (three items).

¶ACR, Adaptive Communication and Response, subscale of overall teamwork (three items).

ANOVA, analysis of variance; TAS, Teamwork Assessment Scales.

Table 3.

Summary of observer-rated TAS subscale analysis for simulation-based Team Training of Inter-Professional Students: scenario 1 versus scenario 2

| TAS subscales | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | ||||||||

| N | Mean* | SD | Cronbach’s alpha | N | Mean* | SD | Cronbach’s alpha | Change† | p Value‡ | |

| TBB§ | 168 | 2.81 | 0.68 | 0.957 | 168 | 3.96 | 0.74 | 0.958 | 1.14 | <0.001 |

| SMM** | 151 | 2.47 | 0.82 | 0.944 | 151 | 3.73 | 0.76 | 0.928 | 1.26 | <0.001 |

| ACR¶ | 151 | 2.16 | 0.73 | 0.944 | 151 | 3.31 | 0.82 | 0.936 | 1.15 | <0.001 |

*Mean combined score of third year medical and senior undergraduate nursing students.

†Scenario 2—scenario 1.

‡One-way ANOVA.

§TBB, Team-Based Behaviors, subscale assessing individual performance (five items; multisource evaluation).

**SMM, Shared Mental Model, subscale of overall teamwork (three items).

¶ACR, Adaptive Communication and Response, subscale of overall teamwork (three items).

ANOVA, analysis of variance; TAS, Teamwork Assessment Scales.

Participant learning—RIPL questionnaire

A total of 146-149 matched pre/post-training RIPL scores were available for each item. Differences between mean pretraining to post-training scores for each item are listed in table 4. After Bonferroni correction, statistically significant improvements were noted in 10 of 19 items.

Table 4.

Summary of participant RIPL pre/post-training score analysis for simulation-based TTIPS

| RIPL questionnaire item* | N (matched) | Presession Score† | Postsession Score† | ∆ (post— pre)† | p Value‡ |

| Learning with other students will help me become a more effective member of a healthcare team | 149 | 4.57 (0.54) | 4.77 (0.43) | 0.19 (0.55) | 0.000§ |

| Patients would ultimately benefit if healthcare students worked together to solve patient problems | 149 | 4.68 (0.48) | 4.79 (0.42) | 0.10 (0.49) | 0.013 |

| Shared learning with other healthcare students will increase my ability to understand clinical problems | 148 | 4.50 (0.60) | 4.77 (0.44) | 0.27 (0.55) | 0.000§ |

| Learning with other healthcare students before qualification would improve relationships after qualification | 149 | 4.48 (0.61) | 4.77 (0.44) | 0.30 (0.58) | 0.000§ |

| Communication skills should be learnt with other healthcare students | 149 | 4.60 (0.54) | 4.78 (0.45) | 0.18 (0.53) | 0.000§ |

| Shared learning will help me think positively about other professionals | 148 | 4.45 (0.62) | 4.76 (0.43) | 0.31 (0.63) | 0.000§ |

| Teamworking skills are essential for all healthcare students to learn | 149 | 4.64 (0.51) | 4.79 (0.41) | 0.14 (0.49) | 0.001§ |

| Shared learning will help me to understand my own limitations | 149 | 4.44 (0.68) | 4.73 (0.53) | 0.29 (0.67) | 0.000§ |

| I do not want to waste my time learning with other healthcare students | 149 | 1.57 (0.85) | 1.41 (0.93) | −0.16 (0.88) | 0.027 |

| It is not necessary for undergraduate healthcare students to learn together | 149 | 1.71 (0.84) | 1.48 (0.94) | −0.23 (0.95) | 0.004 |

| Clinical problem-solving skills can only be learnt with students from my own department | 148 | 1.73 (0.90) | 1.61 (1.07) | −0.11 (1.08) | 0.200 |

| Shared learning with other healthcare students will help me communicate better with patients and other professionals | 149 | 4.40 (0.67) | 4.56 (0.86) | 0.15 (1.02) | 0.066 |

| I would welcome the opportunity to work on small-group projects with other healthcare students | 148 | 4.16 (0.86) | 4.61 (0.75) | 0.46 (0.80) | 0.000§ |

| Shared learning will help to clarify the nature of patient problems | 149 | 4.29 (0.69) | 4.70 (0.55) | 0.41 (0.68) | 0.000§ |

| Shared learning before qualification will help me become a better teamworker | 146 | 4.43 (0.61) | 4.73 (0.46) | 0.29 (0.60) | 0.000§ |

| The function of nurses and therapists is mainly to provide support for doctors | 147 | 2.38 (1.13) | 2.40 (1.40) | 0.02 (1.38) | 0.858 |

| I’m not sure what my professional role will be | 148 | 2.34 (1.09) | 2.29 (1.24) | −0.05 (1.03) | 0.524 |

| I have to acquire much more knowledge and skills than other healthcare students | 149 | 3.05 (1.09) | 2.78 (1.25) | −0.27 (1.06) | 0.002 |

*Scale: 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree.

†Mean (SD).

‡Paired two-tailed t-test.

§Statistically significant after Bonferroni adjustment.

RIPL, Readiness for Interprofessional Learning; TTIPS, Team Training of Inter-Professional Students.

Participant behaviour change—‘yearly’ TTAQ

Overall, 472 medical students and undergraduate nursing students completed either a pre-TTAQ, post-TTAQ or a pre-TTAQ and post-TTAQ questionnaire. Of this number, a total of 247–251 students (118–122 medical students, 129 undergraduate nursing students) had matched pre/post-TTAQ forms for analysis. Of this number, 106 students (57 medical students, 49 undergraduate nursing students) had participated in the team training scenarios over the course of the year. Of the non-trained students with matched pre-/post-TTAQ forms, 65 were medical students and 80 were undergraduate nursing students.

TTAQ pre/postintervention scores for overall, trained and trained versus non-trained student groups are given in table 5. Overall, for matched combined trained and non-trained, medical students and undergraduate nursing students both demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in the mutual support subscale of the TTAQ over the course of their time in clinical training. In addition, medical students demonstrated improvement in the team structure subscale. Among matched trained students, medical students demonstrated statistically significant improvements in the team structure subscale. For matched trained undergraduate nursing students, a trend towards improvement in the team structure subscale was apparent. This same subscale was found to be statistically significantly more improved in trained versus non-trained students.

Table 5.

Summary of TTAQ subscale analysis for simulation-based TTIPS

| TTAQ subscales* | N, matched | Pretraining score, 2011† | Post-training score, 2012† | ∆: Post—pre TTAQ† | p Value‡ |

| Medical students | |||||

| Team structure | 122 | 4.46 (0.36) | 4.55 (0.37) | 0.10 (0.43) | 0.012 |

| Leadership | 122 | 4.68 (0.38) | 4.72 (0.35) | 0.04 (0.50) | 0.326 |

| Situation monitoring | 121 | 4.44 (0.45) | 4.45 (0.50) | 0.01 (0.53) | 0.896 |

| Mutual support | 119 | 3.20 (0.62) | 3.47 (0.75) | 0.26 (0.72) | 0.000 |

| Communication | 118 | 4.07 (0.40) | 4.14 (0.47) | 0.08 (0.49) | 0.086 |

| Undergraduate nursing students | |||||

| Team structure | 129 | 4.40 (0.43) | 4.55 (0.45) | 0.05 (0.47) | 0.218 |

| Leadership | 129 | 4.69 (0.34) | 4.70 (0.34) | 0.01 (0.33) | 0.836 |

| Situation monitoring | 129 | 4.44 (0.40) | 4.49 (0.40) | 0.05 (0.42) | 0.210 |

| Mutual support | 129 | 6.07 (0.80) | 6.45 (1.16) | 0.37 (1.36) | 0.002 |

| Communication | 129 | 4.03 (0.40) | 3.97 (0.41) | 0.06 (0.49) | 0.172 |

| Trained versus non-trained students | |||||

| N, matched§ | Trained ∆† | Non-Trained ∆† | Total ∆† | p Value | |

| Team structure | 472 (251) | 0.15 (0.49) | 0.02 (0.45) | 0.07 (0.45) | 0.023 |

| Leadership | 472 (251) | 0.05 (0.36) | 0.01 (0.35) | 0.02 (0.42) | 0.457 |

| Situation monitoring | 472 (250) | 0.09 (0.53) | −0.02 (0.43) | 0.03 (0.48) | 0.176 |

| Mutual support | 472 (248) | 0.20 (1.08) | 0.40 (1.18) | 0.31 (1.14) | 0.085 |

| Communication | 472 (247) | 0.03 (0.48) | −0.07 (0.43) | −0.03 (0.44) | 0.070 |

*Scale: 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree.

†Mean (SD).

‡Paired two tail t-test.

§Total number (trained).

¶Analysis of variance.

TTAQ, TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitude Questionnaire; TTIPS, Team Training of Inter-Professional Students.

Discussion

In this study, a 2-hour, high-fidelity SBT session integrated into the existing curricula of third year medical students and senior undergraduate nursing students demonstrated effectiveness on three of four Kirkpatrick Levels.27 Students had a very positive reaction to the SBT experience (level 1); they learnt team-based KSAs (level 2) and developed more positive attitudes towards each other’s profession (level 2) and they incorporated improvements in attitudes related to team structure over the course of the clinical training period measured (level 3). The levels 1 and 2 findings are consistent with our prior work using high-fidelity SBT to train interprofessional teams of healthcare students.14 28 33 Improvement in team-based behaviours34 35 and attitudes16–18 36 has also been demonstrated by other authors conducting IPE sessions focusing on teamwork. Learning KSAs regarding effective team-based competencies might mitigate the negative impact of the surgical work culture, helping students resist the tendency towards ‘tribalism'.37 The fact that students who underwent the high-fidelity SBT seemed to incorporate key attitudes towards team structure compared with non-trained students over the course of their clinical experience suggests that positive modelling in a SBT setting might in fact overcome some pernicious aspects of the hidden curriculum. This finding is particularly interesting since many of the RIPL items that demonstrated statistical significant improvements immediately after the training intervention were related to IPE helping promote better teamwork and team-based skills for participants (see items 1, 4, 6, 7, 15 (table 5)). Although the TTAQ measures attitudinal change, often cited as a level 2 change, the fact that a significant improvement was observed in trained versus non-trained students over a year suggests that these students incorporated this attitude into their everyday clinical activities. Such a level 3 finding of attitudinal behavioural change highlights the power of the Kolb’s experiential learning using SBT. By fostering interprofessional collaboration and altering attitudes towards the team over time, this training could help overcome the silo mentality so prevalent in the clinical environment.

Improving teamwork in the clinical setting requires breaking down long-held professional attitudes and beliefs that are deep-seated and arise out of a work environment characterised by a silo mentality.1 To break down such barriers to effective teamwork, therefore, educators must intervene early in training to try to promote interprofessional attitudes that foster collaboration and understanding. The social constructivism of SBT allows for such a targeted intervention. The improved RIPL items emphasised the positive consequences of working with other professional students in an IPE endeavour. In this manner, they were creating positive interprofessional attitudes and beliefs in lieu of the detrimental ones often exhibited in the clinical environment.1 37 38

IPE has been defined by the WHO as bringing two or more professions together to learn with, from and about each other.39 Clearly, the experiential, shared learning of high-fidelity SBT allows for just such an educational experience. By engaging in a joint-simulated patient experience, the students are then able to reflect together, learn about each other’s roles and responsibilities, identify strengths and weaknesses, draw lessons from one another and then apply them in clinical practice. Thus, as the students work together through Kolb’s learning cycle, the SBT addresses all four key IPEC domains related to interprofessional competencies. Given the increasing emphasis on the incorporation of IPE into undergraduate healthcare professional education,7–9 integrating SBT activities into existing curricula to bring together students from two or more healthcare professions, as was successfully done in this study, provides a potential solution to the challenges to conducting IPE at this level of training. Nonetheless, logistical challenges still exist using this seemingly straightforward solution. In this study, the differing academic schedules of the Schools of Medicine and Nursing and the disproportionate sizes of the classes prevented all students from participating in the IPE SBT pilot.

Due to the TAS’ MSE design, comparison of self-based, peer-based and observer-based ratings is possible. In this study, participants overestimated self-based and team-based performance during the scenarios compared with observer-based ratings. This inflated rating was over two scale points higher after the first scenario and over one scale point higher after the second scenario compared with observer scores. In addition, SD for the overall teamwork scales after the first scenario were above one scale point, suggesting that individuals had difficulty with judging team performance accurately. This overestimation of one’s own ability related to team-based competencies is consistent with findings from our prior work related to interprofessional student OR high-fidelity SBT.14 It dovetails with literature demonstrating a tendency to inflate one’s own perceived performance among professional degree students,40 surgical residents41 and OR clinicians.42

Clearly, self-ratings need to be taken with a ‘grain of salt’, but they should not be discarded. Since the most egregious overestimations are committed by individuals with the least insight and/or skill,43 such ratings could serve a formative function by demonstrating the ‘practice gap’ between the perceived and actual performance, thereby providing the crucial ‘need to know’ of adult learning.44 The fact that the students’ self-rated overall team performance demonstrated statistically significant improvements with smaller SD from the first to the second scenario suggests a degree of learning and calibration of at least team evaluation. Nonetheless, overestimation of self-performance by clinically inexperienced learners is an important finding, since it can help facilitators of debriefings calibrate remarks and evaluations to promote student learning by accurately reflecting performance to them.

The participant peer assessments tended to overestimate TBB, SMM and ACR compared with observer-based ratings. Average scores for each subscale were actually higher than the self-determined ratings of performance. Thus, in this circumstance, participant raters gave colleagues the benefit of the doubt in relation to their performance during the SBT sessions. The SMM subscale did produce a statistically significant improvement in peer-rated scores from the first to the second scenario, implying that the debriefings gave students a better sense of team-based competencies. Additional training, acquisition of team-based KSAs and repeated use of the TAS (or other team assessment tools) could lead to a better appreciation of team-based competencies with more accurate assessment of peer performance.

Limitations to this study do exist. First, it is single institution involving a convenience sample of a limited number of students. Second, data reconciliation revealed gaps for all instruments used. Only about 100 participants adequately completed first and second scenario TAS forms for evaluation. This fact might reveal a reticence on the behalf of individuals to rate themselves or confusion over instructions as to how the TBB form should be filled out. Matched RIPL forms were available for approximately 78% of the students participating in the pilot. Matched TTAQs were available for approximately 53% of all students who completed them. Of those students who participated, approximately 57% matched TTAQs were available. Although less than complete, these values represent acceptable response rates for surveys in the literature. In lieu of conducting unmatched analyses of presurveys and postsurveys that would allow a larger number of participants to be included, the authors opted to conduct the more useful matched analyses with the numbers available. Third, the target learner group was very specific, making findings narrow in scope. Fourth, the unequal team sizes may have biased results. For example, larger sized teams might have functioned less smoothly; smaller sized teams might have been overburdened with tasks. The average team member size over the 42 sessions was 5, however, suggesting the impact of either extreme was blunted. Fifth, many of the subscales did not demonstrate improvement. Given that the intervention was limited to one session for most of the students involved, the fact that attitudes did not change over the course of a year would not be necessarily surprising, and, in fact, might be expected. The fact that one subscale, the team structure subscale, improved and that this correlated with RIPL improvements in items related to teamwork and team structure makes this finding even more interesting and worth mentioning. Sixth, the Cronbach’s alpha were lower than 0.7 for the scenario 2 adaptive communication and response subscales for peer assessment and self-assessment and for scenario 2 team-based behaviours for self-assessment. Nonetheless, overall, the internal consistency of the subscales was generally good. Finally, the RIPL and TAS data were only collected during each educational session, preventing longitudinal follow-up of these attitudes and skills. The TTAQ data, however, provided some longitudinal follow-up regarding the impact of the training.

Future directions include following students as they complete their studies and enter clinical practice to determine if the behavioural changes seen continue to persist and influence the work culture. In addition, expanding the scope and scale of the training to include more students is also a goal. Finally, examining the effectiveness of debriefing in relation to student learning would help determine the best manner to teach this form of SBT.

Conclusion

In summary, high-fidelity SBT of interprofessional teams composed of third year medical students and senior undergraduate nursing students using trauma-based emergency department resuscitation scenarios is well received by students, appears to improve students’ performance in individual and overall team-based competencies as well as attitudes towards interprofessional learning in the simulation-based setting. Students tend to overestimate their own individual as well as their peers’ team-based performances during these SBT sessions. Such inflation of scores, however, might be overcome by additional training, acquisition of team-based KSAs and use of team evaluation tools. Most importantly, such SBT appears to foster behavioural change by altering students’ attitudes towards team structure over the course of their clinical experience. As with other forms of SBT of interprofessional student teams, such training has the potential of helping to transform the surgical work culture to promote highly reliable team function.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the students who participated in the training sessions for this project.

Footnotes

Contributors: Concept and design: JP; acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: JP, QY, VR; drafting of manuscript: JP, DG, QY; critical revision of manuscript: JP, DG, QY, VR.

Funding: 2011 - 2012 Educational Enhancement Grant from the LSUHSC-NO Academy for the Advancement of Educational Scholarship

Competing interests: John T. Paige: royalties from Oxford University Press as co-editor for Simulation in Radiology;research funding from Acell, Inc. (wound healing), LSU Board of Regents (software development), HRSA (inter-professional education and team training), SGEA (tool development)Deborah Garbee and Qingzhao Yu: research funding from HRSA (inter-professional education and team training) and SGEA (tool development)Vadym Rusnak: consultant Simulab, Inc., research funding LSU Board of Regents (software development).

Ethics approval: LSU Health New Orleans Health Sciences Center IRB.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Correction notice: This paper has been amended since it was published Online First. Owing to a scripting error, some of the publisher names in the references were replaced with ’BMJ Publishing Group'. This only affected the full text version, not the PDF. We have since corrected these errors and the correct publishers have been inserted into the references.

References

- 1.Bleakley A. You are who I say you are: the rhetorical construction of identity in the operating theatre. J Workplace Learn 2006;18:414–25. 10.1108/13665620610692980 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleakley A, Boyden J, Hobbs A, et al. Improving teamwork climate in operating theatres: the shift from multiprofessionalism to interprofessionalism. J Interprof Care 2006;20:461–70. 10.1080/13561820600921915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke CS, Salas E, Wilson-Donnelly K, et al. How to turn a team of experts into an expert medical team: guidance from the aviation and military communities. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:i96–i104. 10.1136/qshc.2004.009829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horsburgh M, Lamdin R, Williamson E. Multiprofessional learning: the attitudes of medical, nursing and pharmacy students to shared learning. Med Educ 2001;35:876–83. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00959.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reeves S, Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, et al. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;1:CD002213. 10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leape L, Berwick D, Clancy C, et al. Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Safety Foundation. Transforming healthcare: a safety imperative. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:424–8. 10.1136/qshc.2009.036954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greiner AC, Knebel E. Institute of Medicine. Health Professions Education: a Bridge to Quality. Washington D.C: National Academies Press, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IOM (Institute of Medicine). Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: report of an expert panel. Washington, D.C: Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaubien JM, Baker DP. The use of simulation for training teamwork skills in health care: how low can you go? Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13 Suppl 1:i51–i56. 10.1136/qshc.2004.009845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kolb DA and Fry RE. Toward an applied theory of experiential learning. MIT Alfred P. Sloan School of Management, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vygotsky LS. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. New York, USA: Oxford University Press, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, et al. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA 2006;296:1094–102. 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paige JT, Garbee DD, Kozmenko V, et al. Getting a head start: high-fidelity, simulation-based operating room team training of interprofessional students. J Am Coll Surg 2014;218:140–9. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sunguya BF, Hinthong W, Jimba M, et al. Interprofessional education for whom? --challenges and lessons learned from its implementation in developed countries and their application to developing countries: a systematic review. PLoS One 2014;9:e96724. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobgood C, Sherwood G, Frush K, et al. Teamwork training with nursing and medical students: does the method matter? Results of an interinstitutional, interdisciplinary collaboration. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:e25. Epub. 10.1136/qshc.2008.031732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sigalet E, Donnon T, Grant V. Undergraduate students’ perceptions of and attitudes toward a simulation-based interprofessional curriculum. Simul Healthc 2012;7:353–8. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e318264499e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brock D, Abu-Rish E, Chiu CR, et al. Interprofessional education in team communication: working together to improve patient safety. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:414–23. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stefanidis D, Sevdalis N, Paige J, et al. Simulation in surgery: what’s needed next? Ann Surg 2015;261:846–53. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paige JT, Chauvin S. LSUHSC-(NO)Learning Center, an American College of Surgeons (ACS) accredited, comprehensive education institute. J Surg Educ 2010;67:464–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paige JT, Kozmenko V, Yang T, et al. High-fidelity, simulation-based, interdisciplinary operating room team training at the point of care. Surgery 2009;145:138–46. 10.1016/j.surg.2008.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thiagarajan S, Thiagarajan R, England J. Six phases of debriefing, in Play For Performance. 2004. http://www.thiagi.com/pfp/IE4H/february2004.html#Debriefing(accessed 27 Mar 2015).

- 23.Pearson M, Smith D. Debriefing in experience-based learning. In: Boud D, Keogh R, Walker D, Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning, 1985:69–85. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fanning RM, Gaba DM. The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simul Healthc 2007;2:115–25. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3180315539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paige JT. Principles of simulation. In, Robertson HJ, Paige JT, Bok LR eds, simulation in radiology. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2011:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paige JT, Arora S, Fernandez G, et al. Debriefing 101: training faculty to promote learning in simulation-based training. Am J Surg 2015;209:126–31. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirkpatrick DI. Evaluating training programs:the four levels, ed 2. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garbee DD, Paige J, Barrier K, et al. Interprofessional teamwork among students in simulated codes: a quasi-experimental study. Nurs Educ Perspect 2013;34:339–44. 10.5480/1536-5026-34.5.339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsell G, Bligh J. The development of a questionnaire to assess the readiness of health care students for interprofessional learning (RIPLS). Med Educ 1999;33:95–100. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00298.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McFadyen AK, Webster V, Strachan K, et al. The Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale: a possible more stable sub-scale model for the original version of RIPLS. J Interprof Care 2005;19:595–603. 10.1080/13561820500430157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thannhauser J, Russell-Mayhew S, Scott C. Measures of interprofessional education and collaboration. J Interprof Care 2010;24:336–49. 10.3109/13561820903442903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker DP, Krokos KJ, Amodeo AM. TeamSTEPPSTM Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire Manual. http://teamstepps.ahrq.gov/teamstepps_t-taq.pdf (accessed 17Jun 2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Garbee DD, Paige JT, Bonanno L, et al. Effectiveness of teamwork and communication education using an interprofessional high-fidelity human patient simulation critical care code. JNEP 2013;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jankouskas TS, Haidet KK, Hupcey JE, et al. Targeted crisis resource management training improves performance among randomized nursing and medical students. Simul Healthc 2011;6:316–26. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e31822bc676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sigalet E, Donnon T, Cheng A, et al. Development of a team performance scale to assess undergraduate health professionals. Acad Med 2013;88:989–96. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318294fd45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart M, Kennedy N, Cuene-Grandidier H. Undergraduate interprofessional education using high-fidelity paediatric simulation. Clin Teach 2010;7:90–6. 10.1111/j.1743-498X.2010.00351.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gillespie BM, Chaboyer W, Wallis M, et al. Why isn’t ’time out' being implemented? An exploratory study. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:103–6. 10.1136/qshc.2008.030593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carney BT, West P, Neily J, et al. Differences in nurse and surgeon perceptions of teamwork: implications for use of a briefing checklist in the OR. Aorn J 2010;91:722–9. 10.1016/j.aorn.2009.11.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. World Health Organization (WHO). Framework for action on interprofessional education & collaborative practice. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2010/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf (Accessed May 8, 2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Falchikov N, Boud D. Student self-assessment in higher education: a meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res 1989;59:395–430. 10.3102/00346543059004395 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moorthy K, Munz Y, Adams S, et al. Self-assessment of performance among surgical trainees during simulated procedures in a simulated operating theater. Am J Surg 2006;192:114–8. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paige JT, Aaron DL, Yang T, et al. Implementation of a preoperative briefing protocol improves accuracy of teamwork assessment in the operating room. Am Surg 2008;74:817–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, et al. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA 2006;296:1094–102. 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knowles MS, Holton EF III, Swanson RA. The adult learner, 5e. Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1998. [Google Scholar]