Abstract

Introduction

The transition from medical student to doctor has long been a source of concern, with widespread reporting of new graduates’ lack of preparedness for medical practice. Simulation has been suggested as a way to improve preparedness, particularly due to the difficulties in allowing full autonomy for patient care for undergraduate medical students. Few studies look at simulation alone for this purpose, and no studies have compared different simulation formats to assess their impact on preparedness.

Methods

This mixed-method study looked at two different simulation courses in two UK universities. Data were collected in two phases: immediately after the simulation and 3–4 months into the same students’ postgraduate training. Questionnaires provided quantitative data measuring preparedness and interviews provided a more in-depth analysis of experiential learning across final year and how this contributed to preparedness.

Results

There were no significant differences between the two courses for overall preparedness, stress or views on simulation, and no significant differences in opinions longitudinally. Although the study initially set out to look at simulation alone, emergent qualitative findings emphasised experiential learning as key in both clinical and simulated settings. This inter-relationship between simulation and the student assistantship prepared students for practice. Longitudinally, the emphasis on experiential learning in simulation was maintained and participants demonstrated using skills they had practised in simulation in their daily practice as doctors. Nevertheless, there was evidence that although students felt prepared, they were still scared about facing certain scenarios as foundation doctors.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that simulation may positively affect students’ preparedness for practice as doctors. Simulation will never be a replacement for real clinical experience. However, when used prior to and alongside clinical experience, it may have positive effects on new doctors’ confidence and competence, and, therefore, positively impact patient care.

Keywords: medical education research, medical simulation, medical student, undergraduate education, simulation based education

What is already known on this subject.

Numerous studies have suggested that new medical graduates are unprepared for the transition to professional practice, with various methods suggested to improve preparedness.

Simulation has been suggested as an intervention to improve preparedness, but until now, few studies have explored the relationship between simulation and preparedness across the transition, nor compared simulation formats.

What this study adds.

Our study suggests that simulation positively impacts student’s perceptions of their preparedness for the transition to professional practice, but that there are no differences between the two simulation formats studied.

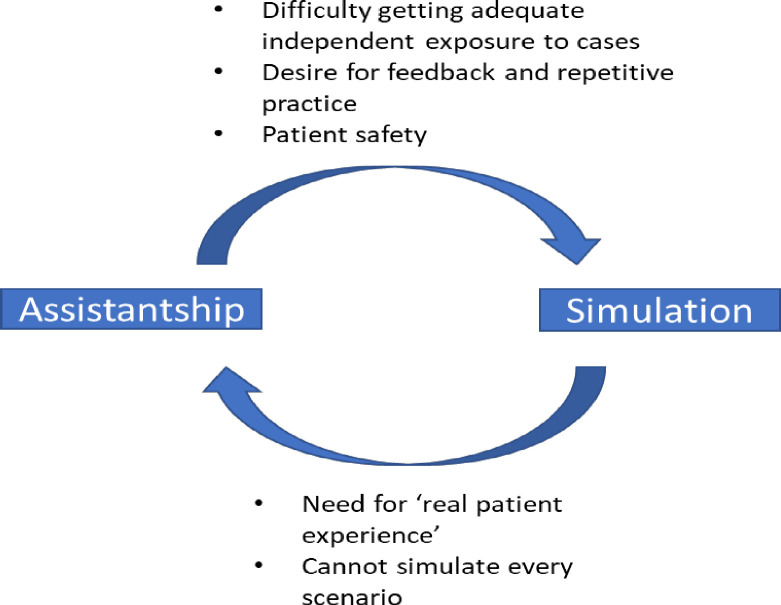

Experiential learning was highlighted as key to students’ preparedness and our data suggest a symbiotic relationship between simulation and the student assistantship; both provide important elements that the other cannot.

Medical schools should focus on integrating different simulation formats alongside other preparedness interventions to ensure new graduates feel prepared to face this key transition.

Introduction

The transition from medical student to doctor is one of the most significant in a trainee doctor’s career. In the UK, all new graduates start their foundation year 1 (FY1) placement on the first Wednesday of August; nicknamed ‘Black Wednesday’, due to evidence that patient mortality increases.1 The shift from sheltered undergraduate level to independent practice, with direct responsibility for patients’ lives adds pressure and expectation, and unsurprisingly levels of anxiety and stress are high.2–4 Patient safety is a priority, but it is also important to protect new doctors’ physical and mental health.5 6 The magnitude of this transition, and the resulting stress, highlights the ongoing challenge in finding ways to prepare for practice.7

Preparation for practice is a complex concept; in 2014, the General Medical Council (GMC)8 defined ‘professionalism, employability, competence, readiness, fitness for purpose and fitness to practice’ as key to preparedness.9 Preparedness is based not only on knowledge or competence but also on previous clinical experiences.8

Studies have shown repeatedly that new graduates do not feel prepared for professional practice.10 11 In 2000, just 36% of graduates felt that their medical school prepared them well for practice.11 By 2014, 69.8% of students reported feeling prepared; perceptions of preparedness have since remained static (69.9% in 2018).12 Substantial differences in reported preparedness can be seen between medical schools.8

Preparedness for particular situations, such as assessing a medical emergency, is vital to professional practice. If a patient is deteriorating, decisions must be made quickly; delayed management due to underconfidence may have catastrophic outcomes. FY1 doctors are often the first to assess such patients and it is imperative that they feel confident and competent to do so. Evidence suggests that while new FY1s feel prepared for history taking and examining patients,9 13 14 they feel unprepared for emergencies.14–16 Other essential skills for new graduates include prioritisation, time management and team working; poor performance in these areas can lead to clinical error. Again, previous studies have shown that new FY1s do not feel prepared for using such skills.2 4 17

There is some evidence that simulation training may improve preparedness.18 19 It is associated with improved knowledge, skills and confidence in dealing with medical emergencies.20–22 Simulation allows students to practice autonomous decision-making without causing patient harm. However, gaps in the literature remain, which may account for the lack of improvements in reported preparedness. Few studies look longitudinally, to assess whether the skills and confidence associated with simulation are maintained over time. In simulation, all decision-making is limited, as it does not place the student in independent practice. Therefore, understanding the interaction between simulation and clinical placement may provide evidence of how to improve preparedness. Few studies have directly compared different simulation courses to establish if the type of simulation affects preparedness.

This study evaluates the effects of two different types of simulation (‘ward’ and ‘pager/bleep’) on perceptions of preparedness and stress surrounding the transition from undergraduate to practice, exploring interaction with other educational interventions.

Simulation courses

In ‘ward simulation’, students rotate around a simulated ward environment encountering different scenarios with simulated patients or mannequins (online supplemental appendix 1).23 24 In the simulation reported here, the focus was on skills including communication, time management and situation awareness. Similar ward simulation is described in the literature.23 25

bmjstel-2020-000836supp001.pdf (338KB, pdf)

For ‘pager/bleep simulation’, students spend time ‘on call’ and are bleeped with various tasks, including prescriptions, interpreting blood results and assessing a medical emergency (online supplemental appendix 1). The simulation reported here was designed to introduce prioritisation, time management and dealing with uncertainty.26 27

Methods

A mixed-method study was designed to investigate simulation interventions currently in use at two UK universities. Quantitative data collection investigated: (a) differences between the simulation courses and (b) longitudinal impact of simulation. Qualitative data explored why those differences occurred and how simulation interacted with other educational interventions.

Participants

Participants were final year medical students from two UK universities, who graduated in academic years 2016/2017 and 2017/2018. Participation in the study was voluntary, with written consent and participants were recruited via their institutions. Simulation type was determined by the institution. All participants undertook ward simulation (standard simulation in year 5 at institution 1) or bleep simulation (standard simulation at institution 2) as part of their curriculum.

Ethics

The Lancaster University Faculty of Health and Medicine Research Ethics Committee (FHMREC) gave ethical approval for the study (ref: FHMREC16037, 2017-01-03) with NHS Health Research Authority (HRA) approvals (ref: 17/HRA/0083, 2017-02-16) and NHS Research and Development (R&D) approvals also secured. Two minor amendments to improve study recruitment procedures were approved.

Data collection

Questionnaire

Two questionnaires were designed based on the GMC’s ‘Outcomes for Graduates’ (OfG) 2015 framework,28 one for students, and one for those same students as FY1s (online supplemental appendix 2). Questions included: preparedness for OfG’s clinical components; stress; overall preparedness; how simulation affected preparedness. The two questionnaires were almost identical, with extra questions relevant to FY1 in the second. Most questions were Likert scale, with some free-text responses. The questionnaires were pilot tested and amended accordingly, then distributed via online survey platform Qualtrics and in paper format. The initial questionnaire was completed immediately after the simulation; the FY1 questionnaire was sent out after 3–4 months FY1 experience. Between February 2017 and June 2018, 216 medical students were invited to participate; 80 student participants gave consent to be followed up 4 months into FY1 training (November 2017 to January 2019).

Interviews

Students were invited to participate in interviews via the questionnaires, with interviews conducted via telephone or face-to-face. Interview questions were asked about the effects of the simulation course and perceptions of preparedness (online supplemental appendix 3). All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and anonymised. The lead researcher conducted all the interviews. Twelve student interviews took place between June 2017 and June 2018 and 6 FY1 were interviewed between November 2017 and January 2019.

Reflexivity

Reflexivity was key to ensuring data quality. As a medical doctor, the lead researcher had shared knowledge and experience of training with the participants, so they were aware that they could not be fully objective. As a facilitator in both simulation courses, the lead researcher was known to the participants. This may have discouraged participants from disclosing specific issues in interviews. Conversely, knowledge that participants and interviewer had shared experiences may have encouraged disclosure.29

Data analysis

All statistical data analysis was performed using SPSS V.14. Comparison analysis between simulation groups and between the student/FY1 phases was performed with χ2 with statistical significance set with a p value of <0.05. Qualitative and quantitative results were integrated following separate analysis as data were collected concurrently.

For ease of further statistical analysis, and consistency with the existing literature, all results are presented in a condensed three-point Likert scale. Combining strongly/somewhat agree, and somewhat/strongly disagree, with neutral responses remaining the same allowed for greater analytical power, as it highlighted the key differences in experiences and perceptions of preparedness.

As the research questions explore the relationship between simulation and preparedness, rather testing a hypothesis, it was not appropriate to adjust for multiple comparisons.30 While the results we present are descriptive and exploratory, we did carry out statistical tests within strata to explore some differences. However, these statistically significant results should be interpreted with caution and would need testing in further confirmatory studies.30

Anonymised interview transcripts were organised in QSR NVivo V.11. A grounded theory informed method was used for analysis.31 32 Transcripts were read and coded inductively by the lead researcher, with the coding tree being reviewed periodically by the other researchers. Transcripts were first coded line-by-line in an initial open-coding process. A constant comparison approach was taken to compare and contrast different codes, develop categories and themes and form links between codes. Subsequently, focused coding was performed on the more significant codes identified. Data were analysed as they were collected, allowing the interview schedule to be developed throughout the study. All participant groups were analysed together. New themes arising, including the difference between real/simulated patient experiences, were incorporated and/or revisited in subsequent interviews as part of the longitudinal data collection.

Results

One hundred and sixteen students were recruited across 2 years (from a student population of 216; 54% response rate) and completed the student questionnaire. Three participants only completed minimal sections; their responses were excluded, leaving 113 participant data sets. Participants who missed one or two answers were included in the analysis. Of the students recruited, 67 undertook the bleep simulation and 46 undertook the ward simulation.

Of the 80 students who consented to follow-up, 30 completed the follow-up questionnaire 4 months into their FY1 year (34% response rate). Two participants consented to participate but did not complete and were excluded from the analysis, leaving 28 participant data sets (bleep simulation: 16 FY1, ward simulation: 12 FY1).

Preparedness for OfG

Here, the focus is on the competencies that have previously been reported in the literature as concerns: preparedness for assessing medical emergencies and other skills including prioritisation, time management and dealing with uncertainty (table 1; see online supplemental appendix 4 for supplementary data).

Table 1.

Comparison table for assessing medical emergencies and other important skills, demonstrating total numbers, numbers from bleep and ward simulation, and p values for the χ2 statistical test

| At this moment in time, I feel my training has prepared me to; | Total % (n) | Bleep simulation % (n) | Ward simulation % (n) | P value | |||||||||

| N= | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | N= | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | N= | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | ||

| Adapt to changing circumstances and uncertainty | 111 | 67.6 (75) | 28.8 (32) | 3.6 (4) | 64 | 59.4 (38) | 35.9 (23) | 4.7 (3) | 47 | 78.7 (37) | 19.1 (9) | 2.1 (1) | 0.098 |

| Assess and recognise a medical emergency/ deteriorating patient. | 113 | 93.8 (106) | 6.2 (7) | 0 (0) | 66 | 95.5 (63) | 4.5 (3) | 0.0 (0) | 47 | 91.5 (43) | 8.5 (4) | 0.0 (0) | 0.389 |

| Lead a team | 113 | 66.3 (75) | 27.4 (31) | 6.2 (7) | 66 | 63.6 (42) | 30.3 (20) | 6.(4) | 47 | 70.2 (33) | 23.4 (11) | 6.4 (3) | 0.719 |

| Manage time appropriately and prioritise tasks | 113 | 79.6 (90) | 18.6 (21) | 1.8 (2) | 66 | 75.8 (50) | 21.2 (14) | 3.0 (2) | 47 | 85.1 (40) | 14.9 (7) | 0.0 (0) | 0.314 |

| Work in a multidisciplinary team | 113 | 98.2 (111) | 1.8 (2) | 0 (0) | 66 | 97.0 (64) | 3.0 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 47 | 100(47) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.229 |

| Work independently and autonomously, taking responsibility for decisions | 113 | 74.3 (84) | 23.0 (26) | 2.7 (3) | 66 | 68.2 (45) | 27.3 (18) | 4.5 (3) | 47 | 83.0 (39) | 17.0 (8) | 0.0 (0) | 0.123 |

Students felt most prepared for working in an MDT (98% agreed), and for assessing a medical emergency (94%) (table 1). Students felt less prepared for working independently (74%), adapting to changing circumstances and uncertainty (68%) and leading a team (66%).

Students undertaking the ward simulation felt significantly more prepared than students undertaking the bleep simulation for seven of the OfG core competencies. Although not all these skills were directly assessed in the simulation, they are core elements of overall preparedness, which was the focus of the wider study; their measurement contributed to the global assessment of student preparedness. Only interpretation of diagnostic tests was covered in simulation training, therefore, no significant differences can be attributed to the efficacy of the simulation courses in influencing students’ preparedness. There were no significant differences in preparedness across the student/FY1 transition (table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison table for assessing medical emergencies and other important skills, demonstrating total numbers of students and total number of FY1, and numbers from the FY1 follow-up and p values for the χ2 statistical test

| At this moment in time, I feel my training has prepared me to; | Student % (n) | FY1 % (n) | P value | ||||||

| N= | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | N= | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | ||

| Adapt to changing circumstances and uncertainty | 111 | 67.6 (75) | 28.8 (32) | 3.6 (4) | 28 | 64.3 (18) | 21.4 (6) | 14.3 (4) | 0.086 |

| Assess and recognise a medical emergency/ deteriorating patient. | 113 | 93.8 (106) | 6.2 (7) | 0 (0) | 28 | 89.3 (25) | 10.7 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.404 |

| Lead a team | 113 | 66.3 (75) | 27.4 (31) | 6.2 (7) | 28 | 71.4 (20) | 25 (7) | 3.6 (1) | 0.816 |

| Manage time appropriately and prioritise tasks | 113 | 79.6 (90) | 18.6 (21) | 1.8 (2) | 28 | 82.1 (23) | 10.7 (3) | 7.1 (2) | 0.210 |

| Work in a multidisciplinary team | 113 | 98.2 (111) | 1.8 (2) | 0 (0) | 28 | 92.9 (26) | 7.1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.125 |

| Work independently and autonomously, taking responsibility for decisions | 113 | 74.3 (84) | 23.0 (26) | 2.7 (3) | 28 | 67.9 (19) | 28.6 (8) | 3.6 (1) | 0.785 |

FY, foundation year.

The quantitative results suggest that participants felt prepared, but across the qualitative data, participants expressed concerns about facing certain scenarios as a new FY1 (box 1). This suggests that participants felt ‘prepared, but still scared’ for many of the competencies expected of them.

Box 1. Example quotes demonstrating being ‘prepared, but still scared’, *SFTQ=Student free-text questionnaire response.

Feeling out of depth re. making independent decisions about unwell patients. SFTQ*

Being first to the scene to assess a patient even though I feel like I know have the skills for it, I’m still nervous about it. Student 8, interview

Being on call/on a shift and having to prioritise patients and make decisions—feels like a lot of responsibility. SFTQ

Being asked to do stuff in the middle of the night and having to make those decisions and stuff like prescribing, having to quickly prescribe stuff I don’t feel that confident with that kind of stuff. Student 4, interview

Preparedness for the transition to practice

Despite mostly feeling confident and prepared for most OfG outcomes,28 when asked about the transition to FY1, students felt stressed and anxious. Overall, 71% felt stressed about becoming a doctor and 77% felt anxious about the transition to professional practice. However, 73% of students agreed that they felt prepared for their FY1 jobs. There was no significant difference between the two simulation courses for stress, anxiety or overall preparedness, nor were there differences following the transition from student to FY1.

Looking back as FY1s, participants continued to lend support to the concept of being ‘prepared but still scared.’ They gave examples of the same concerns that they had as students; dealing with sick patients, the day-to-day job and being on call independently. They also described the importance of support, both from seniors and their peers, and this helped them do their job and feel less stressed. Learning on the job was demonstrated, and this made the participants feel more confident in their role. Qualitative data highlighted significant concerns about taking on independent responsibility. FY1s commented that they regularly stayed late at work to deal with not only medical emergencies but also routine jobs, suggesting potential difficulties with time management and prioritisation.

Simulation and preparedness

Overall, 88.5% of students agreed that simulation had ‘set them up well’ for working as an FY1. No students disagreed with this statement. There were no statistically significant differences between views on simulation across the two sites; students across ward and bleep simulation felt that simulation had prepared them for working as a foundation doctor (bleep: 91% agree, ward: 85% agree, p=0.341). Following the transition from student to doctor, the levels of agreement were similar (88.5% students agreed, 88.9% FY1 agreed), showing that simulation was still seen as valuable even after a period of reflection on practice.

In qualitative data, several key themes were developed from the data. Comparison of themes across groups did not show between-group differences. First, students emphasised the importance of simulation to provide opportunities to independently manage patients and make decisions about their care (ability to practice autonomous decision-making and management). This closely aligned with the second theme, ’ability through simulation for repetition and deliberate practice’. Third, simulation also allowed students to ‘ensure they had a breadth of clinical experience’, exposing students to scenarios that they may not experience on the wards (table 3). Finally, and importantly, data showed that ‘standardisation of clinical experience’ within simulation was crucial in allowing all students to have equitable experience. Repeated exposure to scenario-based practice via simulation was felt to be particularly beneficial for preparing for medical emergencies, which are difficult to fully experience as an undergraduate; this key finding was emphasised throughout the qualitative data.

Table 3.

Students views on the benefits of simulation

| Quotes | Key themes covered |

| Certainly, it’s as real as it can be, so I don’t think it detracts from real patient’s experiences, it’s a different way of seeing something that you wouldn’t necessarily be able to guarantee to see on the wards. S11, interview | Standardisation of clinical experience Ensuring breadth of clinical experience |

| To feel confident, you need to feel comfortable, you need to do things repeatedly, so I would argue that they should make us do the most common scenarios faced by an F1 doctor more frequently. S6, interview | Repetition/deliberate practice |

| Because there were a lot of situations there that I’m sure happen all the time, but we’d never come across as a student, and I feel we’ve not really been prepared for. S5, interview | Ensuring breadth of clinical experience |

| Simulation allows you to think about patients on our own(…). Otherwise, I don’t think we get the opportunity to make our own decisions. S10, interview | Autonomous decision making and management |

| It puts you in a position that you don’t normally get to be in as a student, where your sort of in the thick of it, you’re normally in a sort of observer role as a student, which is understandable, and you don’t necessarily always come across these situations in clinical practice. S12, interview | Standardisation of clinical experience Ensuring breadth of clinical experience Autonomous decision making and management |

| I don’t know how you would possibly tackle acutely unwell patients unless you’d had a lot of opportunities to do it in a safe environment with decent feedback. You just don’t get feedback anymore,(…)every unwell patient you manage, they either become better, or they don’t, and if they don’t then you ask for help and they suggest something else, they rarely give you feedback. FYD4, interview | Autonomous decision making and management Repetition/deliberate practice Feedback |

| It exposes you to clinical scenarios that are common, but because we're never on the ward enough to find it common and having been exposed to those scenarios in simulation I think it prepared us a little bit more. FYD6, interview | Standardisation of clinical experience Ensuring breadth of clinical experience |

Positive views of simulation were supplemented by recognition of the importance of the student assistantship, where students were supervised to care for real patients. Both interventions led participants to describe becoming more confident in diagnostic reasoning, management and practical procedures. Students particularly felt that simulation was vital to have alongside clinical placements. We hypothesise a symbiotic relationship between the student assistantship and simulation, with both contributing to preparedness (figure 1). Simulation and assistantship were still seen as vital preparation for practice following experiences as an FY1. FY1 participants discussed difficulties they had experienced in their first few months of working; these difficulties directly linked to suggestions for developing medical curricula. For example, participants described worry about on call working, and suggested this be increased in the undergraduate course, both real and simulated.

Figure 1.

The symbiotic relationship between simulation and the student assistantship.

Discussion

Data on the transition to practice are often collected at the point of transition, rather than more longitudinally across the final year of study and first year of work. Here, we provide these more longitudinal insights.

Following rises in preparedness between 2009 and 2014 (49% to 69.9%),11 12 further improvements to reported preparedness rates have not been realised. If students feel prepared, they are likely to perform better than if they feel unprepared. FY1 doctors who feel unprepared for the transition to professional practice are more likely to have inadequate Annual Review of Competence Progression (ARCP) outcomes.8 Results here suggest that 72.5% of students felt prepared for practice, supporting evidence that levels of preparedness have not changed in 5 years, despite substantial developments in medical education.

Although quantitative data show that students feel well prepared to assess a medical emergency, qualitative data suggest that participants were still concerned about assessing a medical emergency, especially alone and out of hours/on call. This demonstrates the importance of a mixed-method approach, which can highlight important but nuanced perspectives on interventions under investigation. A rapid review of empirical data found that while 3 papers suggested students were prepared for managing medical emergencies, 10 papers suggested students were not prepared.9 This review described students feeling prepared for some aspects of dealing with medical emergencies such as the ABCDE approach and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR), but unprepared for others.9 They also reported that participants felt that simulation was of limited benefit in learning to deal with medical emergencies, which directly contradicts evidence presented here.9 Other authors describe students’ and supervisors’ concerns regarding managing medical emergencies; however, concern is interpreted as a lack of preparedness.10 Even well-prepared students may feel concerned about certain aspects of the FY1 role, which is reflected in the results of this study: ‘feeling prepared, but still scared’. The simulation courses under study here contributed to students’ preparedness for assessing a medical emergency, but in practice, dealing with a medical emergency was still viewed as scary. Furthermore, Lempp suggests that when FY1 doctors had support from seniors in managing medical emergencies, they felt prepared, but when they were unsupported, they felt unprepared.33 This suggests that preparedness is fluid and situational, and also that an FY1 can feel prepared, but still scared.

Evidence suggests that students may also feel unprepared for other important skills including dealing with uncertainty, prioritisation and time management.4 10 15 17 Data from this study were mixed; students felt less prepared for adapting to change and uncertainty, leading a team and working independently, but they felt better prepared for team working and prioritisation. This is in contrast to some findings across the wider literature, where new FY1s felt underconfident in prioritising a busy workload4 10 in addition to an increased responsibility and making decisions. Workload management is always associated with diverse factors (eg, understaffing, appropriate recompense for exceptional working patterns), but participants demonstrated their time management improving with more experience on the wards. The impact of these other factors makes it difficult to understand whether or not simulation has an effect on time management skills in particular.

Data here suggest that differing the format and frequency of simulation does not seem to make a difference to students’ views of their preparedness. Adapting approaches to simulation may mean that lower cost simulation can be used, which could particularly benefit lower income countries and in the UK where efficiencies in teaching and assessment methods are frequently sought.

A key finding is the interrelationship between simulation and the student assistantship. Authors, including Brennan and Illing, have reported the benefits of a student assistantship to make students feel more prepared for work, and others have reported improved preparedness following simulation.2 10 17 19 This study provides new evidence on the symbiotic relationship between simulation focused on preparation and the student assistantship. The skills focused on in this paper (table 1 and table 2) are areas that are particularly difficult to experience as an undergraduate, evidenced in the idea that ‘the final year of training left the students so peripheral to practice that they were having to consider time management and the prioritisation of patients and tasks for the first time when starting work’.10 Preparedness may ultimately be maximised by using simulation before and alongside the assistantship, to allow students to practise being an FY1 in simulation prior to supervised practising on their assistantship.

The repetition allowed by simulation in general was a key feature by which undergraduates learn from simulation from the results of this study. In the postgraduate simulation literature, feedback has been repeatedly named as the most important aspect.34 The emphasis place on repetition in this study, along with being able to have responsibility for management without senior support and being able to safely make mistakes without repercussions, highlights the different priorities for undergraduate learners compared with postgraduates. This gives further evidence for the importance of simulation for undergraduates, as this repetitive practice is not emulated in the clinical environment with such ease. Through the transition, participants emphasised the importance of both assistantship and simulation for preparedness, further highlighting their symbiotic relationship. This supports the idea that the transition is a ‘critically intensive learning period’35; support and the ability to learn on the job are vital to ensuring new FY1s have as smooth a transition as possible.

Students may feel unprepared due to their expectation of FY1 not reflecting the realities. Managing expectations in undergraduates is thus key to preparing for the transition. This may include real experience of the realities of independent working throughout medical curricula, integration of simulation with student assistantship and ensuring good support before, during and after the transition to enable FY1 doctors to continue to learn on the job.

There may be a ceiling of preparedness, evidenced in the concept of students feeling ‘prepared but still scared’, particularly concerning high-stakes situations such as assessing a medical emergency alone. Students will likely always be apprehensive about the transition to professional practice, even about situations that ‘on paper’ for which they feel prepared. These situations may always be scary no matter how prepared or experienced doctors are. In addition, students cannot experience every condition as an undergraduate, so they will always come across new situations, which may lead to feeling underprepared or scared.

FY1s are expected to learn on the job, and support in this critical transition is essential. However, while a healthy apprehension may motivate most new doctors, for some, that fear may lead to significant stress and anxiety. Elevated stress levels have been shown to affect performance on tasks and decision-making36 and are associated with increased levels of burnout, clinical anxiety and depression.37

Educators should still strive to improve preparedness, even if 100% preparedness is not achievable. Further work should focus on finding an alternative method of measuring preparedness, potentially combining multiple methods and informants to gain a more comprehensive view of preparedness. This would allow a better appreciation of whether interventions to improve preparedness are successful. Simulation should be integrated into a ‘preparedness for FY1’ focused final year with an emphasis on increasing students’ patient care responsibilities and incorporating resilience training.

Strengths and limitations

In common with other medical education research, no sample size calculation was undertaken, as the available population was small, meaning that the available sample may be inadequate to appropriately power a study.38 However, the addition of qualitative data strengthened the data set to draw more robust conclusions. Although the response rate for the student participants was satisfactory at 52%,39 there was substantial dropout between the student and doctor phases. Data were self-reported measures, which may not be an objective measurement of preparedness in actuality.

As the student questionnaire was completed immediately after the simulation, this may have affected views; nevertheless, as reported benefits of simulation were maintained into FY1, it is likely that student views were not overly influenced by the proximity of the simulation.

This research showed that both bleep and ward simulation are effective in helping to prepare students for practice. No previous studies have compared two diverse simulation courses and followed up participants longitudinally. Furthermore, the triangulation of methods and sites provides a strong data set on preparedness and simulation. It cannot be said with certainty that preparedness is directly the result of simulation. Other modalities such as experience on wards will also contribute. The data from this study suggest that assistantship alongside simulation improves preparedness.

Conclusion

Preparedness for professional practice is multifaceted and difficult to describe and measure, as there is no single definition and currently no validated tool to assess preparedness. Furthermore, it is also difficult to establish how simulation directly affects preparedness, due to the multitude of confounding factors within medical education. Nevertheless, this study suggests that simulation has a key role alongside the student assistantship, no matter the format, to help students feel more prepared for professional practice. Although the initial aim was a comparison of effectiveness, what this study adds is a greater understanding of how simulation supports development within the broader context of undergraduate medical training. More work should focus on the interaction between simulation and the assistantship, to establish what students gain from each to decide when and how simulation is best used. Efforts must continue to enable medical schools to produce safe, confident, resilient doctors who can cope with the demands of the modern National Health Service.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the students and doctors who took part in the research.

Footnotes

Contributors: CC, LB and GV designed the study. CC co-ordinated the study, collected and analysed the data. TK supervised CC performing the statistical analysis. CC led the drafting of the manuscript and LB, TK and GV revised it critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Individual participant data that underlie the results following deidentification is available indefinitely at https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/146459/1/2020CarpenterMD.pdf. The study protocol and other documents are available upon reasonable requestPlease address all enquires to c.carpenter1@nhs.net

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Jen MH, Bottle A, Majeed A, et al. Early in-hospital mortality following trainee doctors' first day at work. PLoS One 2009;4:e7103. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brennan N, Corrigan O, Allard J, et al. The transition from medical student to junior doctor: today's experiences of tomorrow's doctors. Med Educ 2010;44:449–58. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van Hamel C, Jenner LE. Prepared for practice? a national survey of UK Foundation doctors and their supervisors. Med Teach 2015;37:181–8. 10.3109/0142159X.2014.947929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kellett J, Papageorgiou A, Cavenagh P, et al. The preparedness of newly qualified doctors - Views of Foundation doctors and supervisors. Med Teach 2015;37:949–54. 10.3109/0142159X.2014.970619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paice E, Rutter H, Wetherell M, et al. Stressful incidents, stress and coping strategies in the pre-registration house officer year. Med Educ 2002;36:56–65. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bogg J, Gibbs T, Bundred P. Training, job demands and mental health of pre-registration house officers. Med Educ 2001;35:590–5. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00951.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bullock A, Fox F, Barnes R, et al. Transitions in medicine: trainee doctor stress and support mechanisms. J Workplace Learn 2013;25:368–82. 10.1108/JWL-Jul-2012-0052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. GMC . The state of medical education and practice in the UK. London; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Monrouxe LV, Bullock A. How prepared are UK medical graduates for practice? final report from a programme of research commissioned by the general medical Council; 2014. [Accessed 14 Jun 2014].

- 10. Illing JC, Morrow GM, Rothwell nee Kergon CR, et al. Perceptions of UK medical graduates' preparedness for practice: a multi-centre qualitative study reflecting the importance of learning on the job. BMC Med Educ 2013;13:34. 10.1186/1472-6920-13-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goldacre MJ, Lambert TW, Svirko E. Foundation doctors' views on whether their medical school prepared them well for work: UK graduates of 2008 and 2009. Postgrad Med J 2014;90:63–8. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. GMC . General Medical Council - National Training Surveys, 2019. Available: https://webcache.gmc-uk.org/analyticsrep/saw.dll?Dashboard

- 13. Gibbins J, McCoubrie R, Forbes K. Why are newly qualified doctors unprepared to care for patients at the end of life? Med Educ 2011;45:389–99. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03873.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Braniff C, Spence RA, Stevenson M, et al. Assistantship improves medical students' perception of their preparedness for starting work. Med Teach 2016;38:51–8. 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1045843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tallentire VR, Smith SE, Wylde K, et al. Are medical graduates ready to face the challenges of Foundation training? Postgrad Med J 2011;87:590–5. 10.1136/pgmj.2010.115659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lightman E, Kingdon S, Nelson M. A prolonged assistantship for final-year students. Clin Teach 2015;12:115–20. 10.1111/tct.12272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berridge E-J, Freeth D, Sharpe J, et al. Bridging the gap: supporting the transition from medical student to practising doctor--a two-week preparation programme after graduation. Med Teach 2007;29:119–27. 10.1080/01421590701310897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bartlett M, Gay SP, Kinston R, et al. Taking on the doctor role in whole-task simulation. Clin Teach 2018;15:236–9. 10.1111/tct.12678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stroben F, Schröder T, Dannenberg KA, et al. A simulated night shift in the emergency room increases students' self-efficacy independent of role taking over during simulation. BMC Med Educ 2016;16:177. 10.1186/s12909-016-0699-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cash T, Brand E, Wong E, et al. Near-peer medical student simulation training. Clin Teach 2017;14:175–9. 10.1111/tct.12558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. DeWaay DJ, McEvoy MD, Kern DH, et al. Simulation curriculum can improve medical student assessment and management of acute coronary syndrome during a clinical practice exam. Am J Med Sci 2014;347:452–6. 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182a562d7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ruesseler M, Weinlich M, Müller MP, et al. Simulation training improves ability to manage medical emergencies. Emerg Med J 2010;27:734–8. 10.1136/emj.2009.074518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harvey R, Mellanby E, Dearden E, et al. Developing non-technical ward-round skills. Clin Teach 2015;12:336–40. 10.1111/tct.12344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Joyal KM, Katz C, Harder N, et al. Interprofessional education using simulation of an overnight inpatient ward shift. J Interprof Care 2015;29:268–70. 10.3109/13561820.2014.944259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McGlynn MC, Scott HR, Thomson C, et al. How we equip undergraduates with prioritisation skills using simulated teaching scenarios. Med Teach 2012;34:526–9. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.668235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Watmough S, Box H, Bennett N, et al. Unexpected medical undergraduate simulation training (UMUST): can unexpected medical simulation scenarios help prepare medical students for the transition to foundation year doctor? BMC Med Educ 2016;16:110. 10.1186/s12909-016-0629-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rogers GD, McConnell HW, de Rooy NJ, et al. A randomised controlled trial of extended immersion in multi-method continuing simulation to prepare senior medical students for practice as junior doctors. BMC Med Educ 2014;14:90. 10.1186/1472-6920-14-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. GMC . Outcomes for graduates (Tomorrows doctors). London; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kitzinger J. Qualitative research. introducing focus groups. BMJ 1995;311:299–302. 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bender R, Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing--when and how? J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:343–9. 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00314-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data. 5th ed. Los Angeles: Los Angeles: SAGE, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd edition. London: SAGE, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lempp H, Seabrook M, Cochrane M, et al. The transition from medical student to doctor: perceptions of final year students and preregistration house officers related to expected learning outcomes. Int J Clin Pract 2005;59:324–9. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00438.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Motola I, Devine LA, Chung HS, et al. Simulation in healthcare education: a best evidence practical guide. AMEE guide No. 82. Med Teach 2013;35:e1511–30. 10.3109/0142159X.2013.818632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kilminster S, Zukas M, Quinton N, et al. Preparedness is not enough: understanding transitions as critically intensive learning periods. Med Educ 2011;45:1006–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04048.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. LeBlanc VR. The effects of acute stress on performance: implications for health professions education. Acad Med 2009;84:S25–33. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b37b8f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Willcock SM, Daly MG, Tennant CC, et al. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity in new medical graduates. Med J Aust 2004;181:357–60. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cook DA, West CP. Perspective: Reconsidering the focus on "outcomes research" in medical education: a cautionary note. Acad Med 2013;88:162–7. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827c3d78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nulty DD. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assess Eval High Educ 2008;33:301–14. 10.1080/02602930701293231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjstel-2020-000836supp001.pdf (338KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Individual participant data that underlie the results following deidentification is available indefinitely at https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/146459/1/2020CarpenterMD.pdf. The study protocol and other documents are available upon reasonable requestPlease address all enquires to c.carpenter1@nhs.net