Abstract

Debriefings should promote reflection and help learners make sense of events. Threats to psychological safety can undermine reflective learning conversations and may inhibit transfer of key lessons from simulated cases to the general patient care context. Therefore, effective debriefings require high degrees of psychological safety—the perception that it is safe to take interpersonal risks and that one will not be embarrassed, rejected or otherwise punished for speaking their mind, not knowing or asking questions. The role of introductions, learning contracts and prebriefing in establishing psychological safety is well described in the literature. How to maintain psychological safety, while also being able to identify and restore psychological safety during debriefings, is less well understood. This review has several aims. First, we provide a detailed definition of psychological safety and justify its importance for debriefings. Second, we recommend specific strategies debriefers can use throughout the debriefing to build and maintain psychological safety. We base these recommendations on a literature review and on our own experiences as simulation educators. Third, we examine how debriefers might actively address perceived breaches to restore psychological safety. Re-establishing psychological safety after temporary threats or breaches can seem particularly daunting. To demystify this process, we invoke the metaphor of a ‘safe container’ for learning; a space where learners can feel secure enough to work at the edge of expertise without threat of humiliation. We conclude with a discussion of limitations and implications, particularly with respect to faculty development.

Keywords: debriefing, simulation-based education, psychological safety, communication, faculty development

Introduction

Debriefings drive learning during simulation-based training.1–4 These facilitated conversations among learners and faculty explore the relationships among events, actions, thoughts, feelings and outcomes.1 2 5 6 Effective debriefings help learners make sense of events and through reflection, encourage the transfer of learning from simulated cases to the general patient care context.7–9

Learners make mistakes, particularly when learning includes new habits and skills. Educators should enable them to reflect on these mistakes.10 However, organisational culture tends to regard mistakes as something to avoid; employees are usually rewarded for making no mistakes at all or correcting them quickly.11 As a consequence, employees experience fear, anxiety and embarrassment when they make mistakes and when they ask for help and seek feedback.10 12 Many employees engage in ‘protective strategies’13 such as face-saving actions: withdrawal, reluctance to ask for help and disclose errors and obscuring critique.10 12 14 This culture may suppress reflection in some debriefings,15 limiting feedback effectiveness in healthcare team trainings.16 Learning-oriented behaviours like speaking up, asking for help, admitting one is wrong or sharing assumptions, require participants to overcome feelings of defensiveness in discussing suboptimal performance.17–19 Debriefers are tasked with managing a dynamic balancing act among their learners: between feelings of fear, defensiveness and the desire to openly share, reflect and discuss for purposes of performance improvement. This sense of safety that enables effective learning conversations is called psychological safety.10 12

This paper provides a review of evidence for the importance of psychological safety for debriefing conversations and, most importantly, recommendations for establishing, maintaining and restoring psychological safety in debriefings. For this purpose, we follow the format of a hybrid review in which we combine the evidence from various streams of literature (ie, research on organisational behaviour, teams, emotions, safety, simulation and education, couple interaction and psychotherapy) with our extensive collective experience as simulation educators. We aim to add to the current understanding of psychological safety in simulation by providing simulation educators actionable knowledge on how to establish, maintain and even restore psychological safety during debriefings. Building on innovative work by Rudolph et al on establishing psychological safety prior to debriefing,14 17 20 we focus on the time of when the debriefing starts until it is finished. These strategies contribute to the interplay of learners’ emotional state and their cognitive processes during the debriefing, which impact learning.18 21 22

To achieve our aim, first we provide a detailed definition of psychological safety and justify its importance for debriefings. Second, we build on research to identify actions debriefers can take from start to finish of the debriefing that contribute to psychological safety. We also draw selected behavioural anchors and categories from existing instruments to assess debriefing performance:

The Debriefing Assessment for Simulation in Healthcare (DASH).19–21 We especially drew on element 2 of the DASH rater handbook, which addresses maintaining an engaging learning environment;

The Objective Structured Assessment of Debriefing;23

DE-CODE: a coding scheme to assess debriefing interactions.24

We differentiate explicit from implicit actions based on team science. Explicit actions are verbal, clear, directive and overt. Implicit actions are mostly non-verbal, tacit, subtle, discreet and sometimes more attitudinal than behavioural. Third, we examine how a debriefer might actively manage perceived breaches to restore psychological safety. We conclude with a discussion of limitations and implications, particularly with respect to faculty development.

Psychological safety

Psychological safety is a perception of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks in a given context.25 In a particular team, for example, psychological safety is high when team members perceive ‘a sense of confidence, that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up. This confidence stems from mutual respect and trust among team members’ (p. 354).12 Psychological safety is not stable, but rather a dynamic and fragile perception. Particularly in interprofessional and interdisciplinary contexts, not all members of a team may experience the same degree of psychological safety at any one time.26 For example, physicians involved in a team debriefing may have a stronger sense of psychological safety among each other compared with the nurses or vice versa.

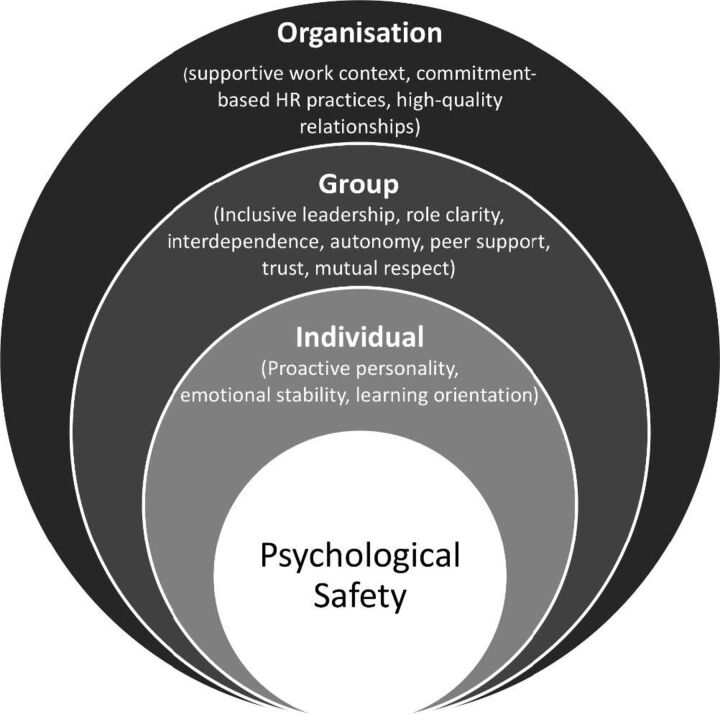

Research in organisational behaviour has revealed that psychological safety depends on the interaction of various factors. These factors are embedded in three levels (figure 1): the individual person, the team (eg, unit, operating room team, training team) and the organisation (eg, hospital; emergency department).25 For example, antecedents of psychological safety at individual and team levels include25 27:

- Individual level:

- Team level:

- Inclusive leadership (ie, leaders’ words and actions inviting and appreciating others’ contributions)31;

- Work design characteristics such as role clarity, interdependence, autonomy;

- Peer support;

- Trust and mutual respect.

Figure 1.

Antecedents of psychological safety.

While we will not discuss the comprehensive research on inputs and outputs of psychological safety, we have highlighted these factors and levels because they demonstrate the complexity of this topic. This is important for debriefings: since psychological safety is a very complex, subjective perception, we must remember that we cannot automatically ‘turn on’ psychological safety or decree that certain environments are ‘safe spaces’. In this paper, we will highlight the actions that simulation educators can take to contribute to intentionally strengthening or inadvertently weakening psychological safety.

Psychological safety in debriefings

Research has demonstrated that psychological safety supports a variety of outcomes such as creativity, engagement, performance, information sharing, speaking up and learning.25 27 Consequently, we view psychological safety as a necessary condition for effective debriefings.17 However, this necessity stands in sharp contrast to typical organisational practice. Organisational culture—in healthcare as in other industries—tends to implicitly view mistakes as a ‘crime’ to be punished, or something to be avoided. In some healthcare settings, for example, people may joke about the ABCs of learning (abuse, belittle, criticise), the ‘Mean Girls’ club in nursing education and dread morbidity and mortality conferences as a place of ‘shame and blame’ rather than learning.32 Employers typically reward employees for making no mistakes at all or correcting them quickly, but not for speaking up about them.11 As a consequence, when employees do make mistakes, ask for help, and or seek feedback, they understandably may experience fear, anxiety and embarrassment.10 12 They tend to engage in face-saving actions such as withdrawal, reluctance to ask for help and disclose errors and obscuring critique.10 12 14 Especially when learners already feel anxious, breaches of psychological safety can make it more likely that ambiguous stimuli will be viewed as threats since emotion frames how people process information.21 22 33 34 These findings help explain why innocent and seemingly innocuous actions on the part of debriefers may inadvertently trigger defensiveness, withdrawal or combativeness. Learners’ continued engagement in a debriefing may depend on how educators address reticence, fear, reluctance to engage or more dramatic breaches to psychological safety. Learners must feel safe to be vulnerable and engage in risk-taking, such as admitting they do not know something or made a mistake. Without this honesty in the service of learning, educators may fail to elicit important reasons behind gaps in performance. Psychological safety encourages learners to willingly ‘try and err at the edge of expertise where knowledge and skills may or may not be sufficient to avoid mistakes’.17

The tension between a desire for psychological safety to nurture learning conversations on the one hand and organisational culture or norms that suppress psychological safety on the other poses a challenge for many debriefers. Rather than simply reinforcing practices that exist elsewhere in the organisation, debriefers can sometime feel they have to create an island of psychological safety during debriefings. This makes their work harder, but may motivate educators to identify strategies to enhance psychological safety during debriefings. In this paper, we discuss actions that work in concert to minimise potential ambiguity and increase psychological safety during debriefings.

The ‘safe container’

The metaphor of a psychologically safe ‘container’ or ‘holding environment’ originates from psychoanalytic disciplines and helps simulation educators understand how to support learners’ risk-taking in the service of learning.35–37 Rudolph et al described this container for debriefing as a ‘context where difficult conversations, emotions or potentially threatening feedback can be tolerated and transformed into generative material in the learning process’.17 In this space, learners should ideally feel safe to be uncomfortable, or trust that they will have help managing difficult feelings and anxiety—an important feature of nurturing experiential learning.38 39 Reducing threats to professional and social identity is increasingly recognised as absolutely essential for learning in groups.12 17 40

Enablers of the ‘safe container’

Unfortunately, the literature sheds little light on many aspects of psychological safety: how it develops, what promotes or threatens it and what may irreparably damage it.25 To identify actions that contribute to psychological safety during debriefings, we expanded our literature review beyond organisational behaviour to include research on teams, simulation-based education, emotion, psychotherapy and couples’ interaction. In addition, we reflected on our own and collective experience as simulation educators in Europe, Australia, Asia and North America.

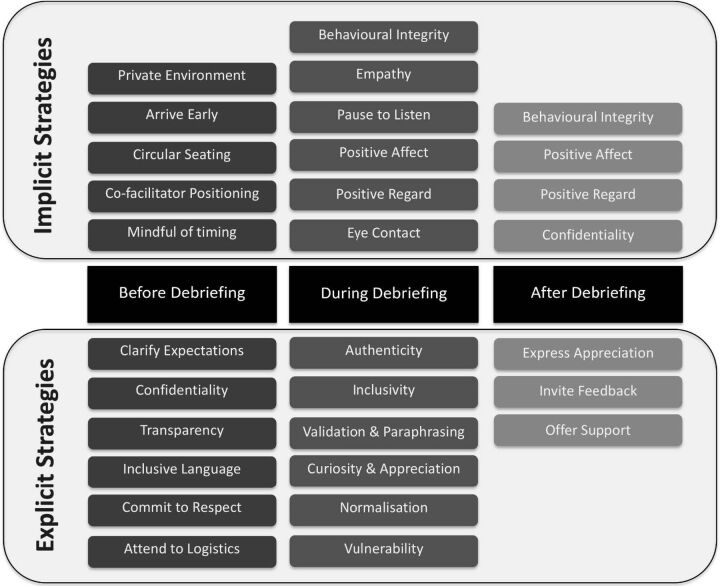

We draw particularly on teamwork literature41–43 to differentiate explicit from implicit strategies (figure 2): whereas explicit actions are typically verbal, clear, directive and overt, implicit actions are mostly non-verbal, tacit, subtle, discreet and sometimes more attitudinal than behavioural. We consider this distinction between explicit and implicit important because they each describe a distinct set of efforts; neither alone is sufficient for creating and maintaining psychological safety.

Figure 2.

Explicit and implicit debriefer strategies contributing to psychological safety before, during and after debriefing. Some strategies (eg, positive regard, behavioural integrity) are important at many times during a debriefing and thus appear more than once.

While explicitness and implicitness go beyond verbal and non-verbal, respectively, they may entail contradictory actions and thoughts. That contradiction may threaten the perception of psychological safety. In debriefings, explicit and implicit actions should usually complement rather than contradict each other. As educators involved in faculty development, we have experienced debriefing situations where debriefers (including ourselves!) do not ‘walk our talk’. For example, debriefers may state that they appreciate the learner and invite them openly share their thoughts (explicit), while at times conveying disinterest by not pausing after a question and interrupting or talking over learners (implicit).

The distinction between explicit and implicit actions allows us to emphasise the need for behavioural integrity or congruence between explicit and implicit messages. As debriefers, we should be consistent between what we say (“I am interested in your thoughts”) and what we do (pausing, listening).17 For example, declarations of curiosity could be accompanied by appropriate eye contact, an open-ended form of questions, pausing, listening and potentially paraphrasing and asking additional open-ended questions.

While factors that influence learners’ perceptions of psychological safety certainly extend beyond debriefers’ actions (figure 1), in this article we focus on how debriefers can contribute to establishing, maintaining and restoring psychological safety. In doing so, we consider the debriefer and potential co-debriefers part of a debriefing system. In a such a debriefing system, debriefers’ actions may influence learners’ sense of psychological safety while at the same time debriefers’ sense of psychological safety may in influence their actions as well.44 Furthermore, many simulation educators lead debriefings with learners from the same institutions. Therefore, we must assume that organisational culture impacts both debriefers’ and learners’ sense of psychological safety.

Establishing psychological safety

For debriefings, work by Rudolph et al describes how to establish a ‘safe container’ for learning in prebriefings before simulation and its debriefings.14 17 20 We extend this important work and provide recommendations for establishing, maintaining and regaining psychological safety during debriefings. Since detailed advice on establishing it prior to debriefing is already available,14 17 20 we particularly focus on the time from the beginning to the end of the debriefing.

Establishing psychological safety prior to debriefing

The prebriefing before simulation-based training represents an ideal moment to engage in actions that contribute to establishing psychological safety. These actions have been described in detail elsewhere.17 45 46 In line with this literature and based on our own experience, we emphasise the importance of explicit actions for establishing psychological safety, however implicit actions such as the tone of voice, pacing, facial expression, inclusion of learners’ point of view and having high regard for the learners are important at this stage as well.

Establishing psychological safety at the beginning of debriefing

At the beginning of the debriefing, educators can explicitly reiterate many of the actions taken to establish psychological safety prior to the debriefing, particularly if some participants are not familiar with debriefings:

Explain the debriefing process and the role of facilitators, participants and any potential observers.17 47

Explicitly invite participants to actively participate, self-reflect and discover and appreciate them for doing it.31 41 47 48

Convey a commitment to respecting participants and understanding their perspective.17 47 49

In our experience, being clear and setting the appropriate tone for the conversation is particularly important at the beginning of the debriefing. Especially in interprofessional and interdisciplinary settings, learners likely have very different experiences with group reflections and restating boundary conditions reaffirms a shared understanding within the group.

Implicit actions can additionally convey respect and curiosity, such as arriving early enough to welcome learners and be attentive to them50 and holding participants and co-debriefers in positive regard.17 47 49 51 In our experience as simulation educators, we consider additional steps as important ways contributing to learners’ psychological safety:

Find a quiet and private debriefing space (if possible);

Arrange the debriefing space to promote discussion (eg, chairs for everybody in a circle or around table rather than classroom seating order, ‘ongoing debriefing’ sign outside the door to avoid unwanted interruptions);

Sit down at eye level and take a position among the participants rather at head of table;

In co-facilitation situations, sit separately among the participants rather than beside each other, allowing to attend to important non-verbal cues8;

Sitting next to a potentially vulnerable learner serves as a way of protecting them if they felt threatened during the scenario;

When choosing where to sit, make sure that you will be able to keep eye contact with everybody and have access to a clock.

In our view, this additional time and preparation is always worthwhile because it emphasises the verbalised commitment to respect.

Maintaining psychological safety

Even seemingly basic debriefing principles collectively play an important role in contributing to psychological safety. These basics work in concert with a variety of other explicit and implicit actions that contribute to psychological safety. While some of them reflect principles of selected debriefing approaches1 52 53 (eg, sharing one’s thoughts), others have not yet been discussed in the debriefing literature. Since the perception of psychological safety is dynamic, and at times, fragile, apparently minor disrespectful behaviours (eg, snapping at a co-debriefer in jest for not handling the video playback efficiently) can negatively impact participants’ feeling of psychological safety.54 In table 1, we list explicit and implicit approaches contributing to psychological safety during debriefing, which are based on evidence from multiples disciplines as well as on our experience. Some of these approaches have particular importance towards the end of the debriefing, an underestimated time period to maintain the safe container. A hasty conclusion to the debriefing may impair psychological safety.

Table 1.

Explicit and implicit contributions to psychological safety during debriefings

| Explicit contributions | Implicit contributions |

|

|

So far we have highlighted behaviours and attitudes that can contribute to nurturing or undermining psychological safety. We have also outlined the dynamic and fragile nature psychological safety and how it can vary among team members.

Identifying breaches to psychological safety

We now discuss potential breaches to the safe container that may threaten the psychological safety of debriefings and ultimately impact learning. Debriefers are often able to recognise these breaches, which seem to suck the air out of the room and make it difficult for anyone to concentrate. Online supplementary table 1 provides an example of recognising and responding to a threat to psychological safety. The table represents a ‘two-column case’ based on work by Argyris et al,13 Senge55 and Rudolph et al.14 The right-hand column outlines the dialogue and non-verbal aspects of the interaction and the left-hand column provides insights to the debriefer’s contemporaneous thinking.

bmjstel-2019-000470supp001.pdf (117.2KB, pdf)

When psychological safety is threatened or breached, the conversation takes on a false or hollow feeling, which becomes unpleasant to all parties involved in the debriefing. In our view, potential indicators of breaches to psychological safety include:

Learners who are typically engaged and conversant become quiet, sharing only brief statements on request;

Learners exhibit closed body language, leaning back with arms folded across their chest and facial expressions that signal discontent;

Learners offer ‘defensive’ or even hostile verbal comments and respond to debriefers’ inquiries with ‘yes-but’ or taunting questions such as “Why are you asking me this?”;

Learners ‘complain’ about realism, arguing that they would have acted differently in real life;

Learners suddenly stop making eye contact, staring at the floor or elsewhere;

Learners argue or criticise each other.

In our experience, it is both important and challenging for debriefers to recognise these breaches and resist the tendency to blame the learner, and instead recognise their own potential contributions to threats to psychological safety. Co-facilitators may voice complaint about the ‘quiet group’ or ‘defensive learners’ during breaks and assign blame to the learners. We think it is normal for debriefers to get upset, too, and to respond to unexpected learner behaviours, which may trigger emotional reactions such as frustration, disappointment, genuine surprise or defensiveness. For example, complaints about realism can be particularly galling when educators spent hours or even days designing and piloting a new simulation. Comments about a simulation being ‘unfair’ can lure debriefers into an argument about how the simulation was, in fact, real. Such arguments can quickly amplify threats to psychological safety; they invalidate learners’ legitimate perceptions and place educators and learners on opposing sides rather than framing them as partners working to co-create new knowledge.

Research on group, family and dyadic dynamics56–60 as well as our experience suggests that many learner reactions reflect how they feel treated by us educators and others. Educators can develop the discipline to assume the learners’ behaviour is a rational response to something the educator may have done and then to reframe learners’ reactions/behaviours during the debriefing as information on how to address this threat or breach to psychological safety. Learners rarely have defensive personalities; they may become quiet or respond with defensiveness when they do not feel psychologically safe.

Restoring psychological safety

We now outline several actions debriefers can take once they have identified potential threats to psychological safety. Again, we draw on our collective experience as simulation educators as well as on research on reflective practice.18 61–63 As we see some chronological order in these actions, we will list them as follows:

Recognising breaches to psychological safety;

Reframing ‘difficult learners’ or ‘defensive behaviour’ as a logical consequence of breaches of psychological safety;

Focusing on ‘first-line’ treatments of breaches to psychological safety on changes in educator behaviour (rather than on the learners);

- Using the above explicit and implicit actions while holding the learner in positive regard17 49 to restore psychological safety, including14 64:

- Conveying positive affect (eg, making eye contact)65;

- Validating and normalising learner concerns;

- Apologising to learners when they express frustration about realism and feelings that they were tricked that they feel may have caused them to underperform;

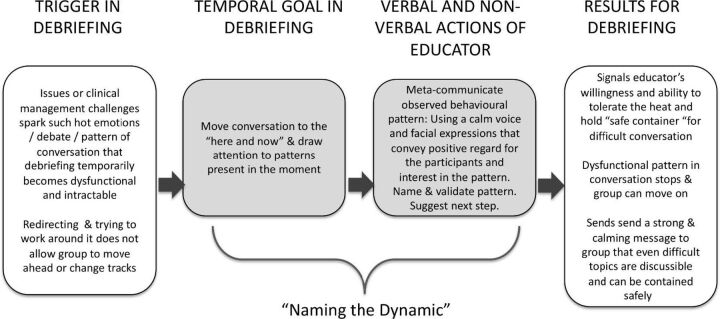

- If appropriate: name the action, dynamic or circumstance that has triggered the breach. This is an advanced yet powerful move of metacommunication to describe a potentially dysfunctional conversational pattern, highlight its limits and signal a way out,38 58 66 which is illustrated in figure 3; examples are provided in table 2.

Figure 3.

Naming the dynamic’ to regain psychological safety.

Table 2.

Examples of ‘naming the dynamic’

| Trigger in debriefing | Examples for educators’ conversational strategies to ‘name the dynamic’* |

| Learners or co-debriefers arguing heatedly about the best way to manage a clinical situation |

Name, initiate reflection on positions

44 66: “Hang on, Franz and Eve, may I press pause for a moment, I think you are talking about something both important and critical. But I am worried we are a bit stuck. Franz I see you are passionate about the importance of a low dose of X whereas Eve you seem to think that approach is wrong-headed. We’ve gone back and forth on this two or three times so I now think I see where you each end up but I don’t yet see—and I doubt others see—how you each got there. I’d like to propose we just slow this down and take a deeper dive into how you arrived at your conclusions. Then I think we will all be able to understand the pros and cons of each approach better. I will act a bit of a mediator here and ask each of you to share your thoughts while we record them on the white board. Okay with you?” |

| Learners criticising each other |

Name, normalise, reframe useful aspects and initiate reflection on positions

44 66: “Thank you for your comment(s)—I would like to press pause for a moment. I think it is interesting how easy it is to see potential errors or warning signals when one is outside the simulation and how difficult/noisy/overwhelming it is inside the simulation and therefore easy to miss things that seem obvious to those outside. This is why we have simulation! I would like us to explore why that is, what it has to do with something called situation awareness, and how we can use this phenomenon in clinical practice. Let’s do this after we have heard from everybody else who was in the simulation how they felt during the sim and agreed on the medical facts of this case”. Or “Thank you for your comment(s)—I would like to press pause for a moment. I think it is somewhat unexpected and fascinating that we can all see the same thing differently. This happens a lot in simulation. It is very common to see things from one’s own perspective or one’s own profession’/disciplines’ perspective and assume others see things like we do. Highlighting this important difference in how we see the same thing differently is a useful aspect of interprofessional simulation. I would like us to explore why that is and we can make use of this variety of expertise, particularly in clinical practice. Let’s do this after we have heard from everybody else who was in the simulation how they felt during the sim and agreed on the medical facts of this case”. |

| Co-debriefers arguing with each other |

Name, pause, restart:

“Ugh! We are arguing! We both care about this topic so much we got overly wound up in this. Let’s pause and rewind. Sorry everyone. Okay let’s see if we can learn something from this”. (Going to the white board to make it more cerebral and ‘cool it down’.) “I think it is crucial to do the X procedure first but Sally thinks it is best to do Y first. Let’s explore the pros and cons of each approach”. |

| Learner seems upset |

Name, validate, provide options:

“Stefan, I see you are getting quieter and quieter and looking at the floor, it seems to me like you might be upset at the moment (pausing, giving time to react). That is perfectly normal. Let’s figure out what would work for you: would you like to have minute to yourself and step in when you feel like it? Do you feel like sharing what’s on your mind—now or in a couple of minutes? Whatever option is fine”. |

| Learner seems angry |

Name, validate, reframe and invite to reformulate a rebuke as a request

77: “I hear you! From what I just heard you say, it sounds to me like you are getting angry at the moment. I understand this, I sometimes get angry when I am very passionate about something. I appreciate that you share your point of view and I think that being able to figure things out together is important for patient safety. I am curious—and I assume others might be too—if you were to put what you have just said as a request or wish, what would that include?” |

| Debriefer losing their temper |

Name and apologise:

“Okay, sorry everyone! I lost my cool! That is not okay. I am so passionate about this issue that I let my feelings get the better of me. Let me rewind. Here is what was going on for me. The last time I had a family meeting like that, things did not go well. That does not justify my behaviour now. If you all are willing, I still think it would be good to explore the steps of a family meeting like this”. |

| Content expert (not trained in debriefing) hectoring or lecturing learners |

Match intensity, then name, normalise and step in:

“Hang on Francisco! I can see you have a strong view on the best way to manage ECMO in that context! (with a friendly but strong/loud voice). However (lowering the volume and intensity of speaker’s voice), everyone here is trying their best and it is my job to allow everyone a chance to talk and share what they were trying to accomplish. Could I ask you to hold your thoughts for a few minutes? We will have a chance to explore the XYZ management challenges shortly. (Also, consider a short break to re-establish rules of engagement with content expert.)” |

*In ‘naming the dynamic’ the educator cannot just say, ‘Rashi and Mandua are mean and petty for treating each other in a mean and petty way!’ The goal is to name the limits of a current, dysfunctional behaviour pattern in a way that raises the conversation to another level.

Debrief the debriefing

In our view, managing threats to psychological safety is an advanced debriefing skill because it requires reflection both in the heat of the moment as well as post hoc.18 61–63 We have benefited from regularly debriefing the debriefing, especially when we have perceived a debriefing as challenging. It provides the opportunity to explore frames and discuss potential mismatch among intentions and effects.14 18 67 68 In the debriefing of the debriefing, we have found it useful to reflect on our own feeling of psychological safety while working with this learner group and this co-facilitator and on how this might be linked to our ability to convey psychological safety as educators.

Conclusion

Research from organisational, psychological, educational and simulation science offers insights into how educators can contribute to establishing, maintaining and regaining psychological safety in debriefings. Psychological safety is a complex, fragile perception influenced by multiple factors interacting on organisational, team and individual level. Some antecedents of psychological safety may lie outside of the debriefing itself, such as the learner’s personality or their experience in the simulation scenario. Even with respect to simulation-based training, our field needs more research on how to manage threats to psychological safety beyond the prebriefing and debriefing, for example, during the simulation scenario.

While this paper focuses specifically on debriefing as part of simulation-based training, most of these insights apply to clinical event debriefing in the workplace. Our recommendations should inform faculty development efforts. We encourage debriefers to seek feedback and reflect on their own debriefing—and on their own sense of psychological safety—to become more aware of how they manage psychological safety and identify their contribution to it.18

Footnotes

Contributors: AC and MK conceived the idea. MK wrote the first draft of manuscript. WE contributed to the two-column case to demonstrate key concepts in action. JR contributed to the concepts and text regarding ‘breaches’ of psychological safety and wrote first draft of section on naming the dynamic. All authors edited and revised manuscript, and approved of the final manuscript for submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: MK, WE, MM, VG, AC, HC and AC are faculty for the Debriefing Academy, which runs debriefing courses for healthcare professionals. MK is faculty at the Simulation Center of the University Hospital Zurich, also providing debriefing faculty development training. JR is faculty at the Center for Medical Simulation, providing debriefing faculty development training. WE receives salary support from the Center for Medical Simulation to teach on simulation educator courses; he also receives per diem honorarium from PAEDSIM e.V. to teach on simulation educator courses in Germany.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Rudolph JW, Simon R, Rivard P, et al. Debriefing with good judgment: combining rigorous feedback with genuine inquiry. Anesthesiol Clin 2007;25:361–76. 10.1016/j.anclin.2007.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fanning RM, Gaba DM. The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simul Healthc 2007;2:115–25. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3180315539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tannenbaum SI, Goldhaber-Fiebert S. Medical team debriefs: Simple, powerful, underutilized. In: Salas E, Frush K, eds. Improving patient safety through teamwork and team training. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013:249–56. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mullan PC, Kessler DO, Cheng A. Educational opportunities with postevent debriefing. JAMA 2014;312:2333–4. 10.1001/jama.2014.15741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Salas E, Klein C, King H, et al. Debriefing medical teams: 12 evidence-based best practices and tips. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2008;34:518–27. 10.1016/S1553-7250(08)34066-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eddy ER, Tannenbaum SI, Mathieu JE. Helping teams to help themselves: comparing two team-led debriefing methods. Pers Psychol 2013;66:975–1008. 10.1111/peps.12041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng A, Eppich W, Grant V, et al. Debriefing for technology-enhanced simulation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Educ 2014;48:657–66. 10.1111/medu.12432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng A, Palaganas J, Eppich W, et al. Co-debriefing for simulation-based education: a primer for facilitators. Simul Healthc 2015;10:69–75. 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ahmed M, Arora S, Russ S, et al. Operation debrief: a SHARP improvement in performance feedback in the operating room. Ann Surg 2013;258:958–63. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828c88fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schein EH. How can organizations learn faster? The challenge of entering the green room. Sloan Management Review 1993;34:85–92. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tucker AL, Edmondson AC. Why hospitals don’t learn from failures: organizational and psychological dynamics that inhibit system change. Calif Manage Rev 2003;45:55–72. 10.2307/41166165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Edmondson A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm Sci Q 1999;44:350–83. 10.2307/2666999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Argyris C, Putnam R, McLain Smith D. Action science: concepts, methods, and skills for research and intervention. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rudolph JW, Foldy EG, Robinson T, et al. Helping without harming: the instructor’s feedback dilemma in debriefing--a case study. Simul Healthc 2013;8:304–16. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e318294854e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kihlgren P, Spanager L, Dieckmann P. Investigating novice doctors’ reflections in debriefings after simulation scenarios. Med Teach 2015;37:437–43. 10.3109/0142159X.2014.956054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hughes AM, Gregory ME, Joseph DL, et al. Saving lives: a meta-analysis of team training in healthcare. J Appl Psychol 2016;101:1266–304. 10.1037/apl0000120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rudolph JW, Raemer DB, Simon R. Establishing a safe container for learning in simulation: the role of the presimulation briefing. Simul Healthc 2014;9:339–49. 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kolbe M, Rudolph JW. What’s the headline on your mind right now? How reflection guides simulation-based faculty development in a master class. BMJ Stel 2018;4:126–32. 10.1136/bmjstel-2017-000247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Allen JA, Reiter-Palmon R, Crowe J, et al. Debriefs: teams learning from doing in context. Am Psychol 2018;73:504–16. 10.1037/amp0000246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brett-Fleegler M, Rudolph J, Eppich W, et al. Debriefing assessment for simulation in healthcare: development and psychometric properties. Simul Healthc 2012;7:288–94. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3182620228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. LeBlanc VR. The relationship between emotions and learning in simulation-based education. Simul Healthc 2019;14:137–9. 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. LeBlanc VR, McConnell MM, Monteiro SD. Predictable chaos: a review of the effects of emotions on attention, memory and decision making. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2015;20:265–82. 10.1007/s10459-014-9516-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arora S, Ahmed M, Paige J, et al. Objective structured assessment of debriefing: bringing science to the art of debriefing in surgery. Ann Surg 2012;256:982–8. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182610c91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Seelandt JC, Grande B, Kriech S, et al. DE-CODE: a coding scheme for assessing debriefing interactions. BMJ Stel 2018;4:51–8. 10.1136/bmjstel-2017-000233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Edmondson AC, Lei Z. Psychological Safety: The History, Renaissance, and Future of an Interpersonal Construct. Annual Rev Org Psyc Organ Behav 2014;1:23–43. 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roussin CJ, MacLean T, Rudolph JW. The safety in unsafe teams: a multilevel approach to team psychological safety. Journal of Management 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Frazier ML, Fainshmidt S, Klinger RL, et al. Psychological safety: a meta-analytic review and extension. Pers Psychol 2017;70:113–65. 10.1111/peps.12183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bateman TS, Crant JM. The proactive component of organizational behavior: a measure and correlates. J Organ Behav 1993;14:103–18. 10.1002/job.4030140202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Costa PT, McCrae RR. Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: the NEO personality inventory. Psychol Assess 1992;4:5–13. 10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mindset DCS. The new psychology of success: How we can learn to fulfil our potential. New York: Ballantine, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J Organ Behav 2006;27:941–66. 10.1002/job.413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Orlander JD, Barber TW, Fincke BG. The morbidity and mortality conference: the delicate nature of learning from error. Acad Med 2002;77:1001–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Blanchette I, Richards A. Anxiety and the interpretation of ambiguous information: beyond the emotion-congruent effect. J Exp Psychol Gen 2003;132:294–309. 10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nabi RL. Exploring the framing effects of emotion: do discrete emotions differentially influence information accessibility, information seeking, and policy preference? Commun Res 2003;30:224–47. 10.1177/0093650202250881 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Freshwater D, Robertson C. Emotions and needs. Buckingham, UK and Philadlphia, USA: Open University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Winnicott D. The family and individual development. London: Tavistock Publishers, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rappoport A. The patient’s search for safety: The organizing principle in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 1997;34:250–61. 10.1037/h0087767 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. French RB. The teacher as container of anxiety: psychoanalysis and the role of teacher. J Manag Educ 1997;21:483–95. 10.1177/105256299702100404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gilmore S, Anderson V. Anxiety and experience-based learning in a professional standards context. Manag Learn 2012;43:75–95. 10.1177/1350507611406482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Edmondson A. The fearless organization. Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Weiss M, Kolbe M, Grote G, et al. We can do it! Inclusive leader language promotes voice behavior in multi-professional teams. Leadersh Q 2018;29:389–402. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wittenbaum GM, Stasser G, Merry CJ. Tacit coordination in anticipation of small group task completion. J Exp Soc Psychol 1996;32:129–52. 10.1006/jesp.1996.0006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kolbe M, Burtscher MJ, Manser T. Co-ACT--a framework for observing coordination behaviour in acute care teams. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:596–605. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. von Schlippe A, Schweitzer J. Systemic interventions. Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Roussin CJ, Larraz E, Jamieson K, et al. Psychological safety, self-efficacy, and speaking up in interprofessional health care simulation. Clin Simul Nurs 2018;17:38–46. 10.1016/j.ecns.2017.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Turner S, Harder N. Psychological safe environment: a concept analysis. Clin Simul Nurs 2018;18:47–55. 10.1016/j.ecns.2018.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Loo ME, Krishnasamy C, Lim WS. Considering face, rights, and goals: a critical review of rapport management in facilitator-guided simulation debriefing approaches. Simul Healthc 2018;13:52–60. 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Newman A, Donohue R, Eva N. Psychological safety: a systematic review of the literature. Hum Resour Manag Rev 2017;27:521–35. 10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rogers CR. The concept of the fully functioning person. Pastoral Psychol 1965;16:21–33. 10.1007/BF01769775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Allen JA, Yoerger MA, Lehmann-Willenbrock N, et al. Would you please stop that!?: The relationship between counterproductive meeting behaviors, employee voice, and trust. Int J Manag Dev 2015;34:1272–87. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kolbe M, Grande B, Spahn DR. Briefing and debriefing during simulation-based training and beyond: Content, structure, attitude and setting. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2015;29:87–96. 10.1016/j.bpa.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Eppich W, Cheng A. Promoting excellence and reflective learning in simulation (PEARLS): development and rationale for a blended approach to health care simulation debriefing. Simul Healthc 2015;10:106-15. 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kolbe M, Weiss M, Grote G, et al. TeamGAINS: a tool for structured debriefings for simulation-based team trainings. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:541–53. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Foulk T, Woolum A, Erez A. Catching rudeness is like catching a cold: The contagion effects of low-intensity negative behaviors. J Appl Psychol 2016;101:50–67. 10.1037/apl0000037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Senge P. The fifth discipline: the art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Billow R. Relational psychotherapy: from basic concepts to passion. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bowen M. Family therapy in clinical practice. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Epstein R. Keeping boundaries: maintaining safety and integrity in the psychotherapeutic process. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mitchell S. Relational concepts in psychoanalysis: an integration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sachse R, disorders P. A clarification-oriented psychotherapy treatment model. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rudolph JW, Simon R, Raemer DB, et al. Debriefing as formative assessment: closing performance gaps in medical education. Acad Emerg Med 2008;15:1010–6. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00248.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rudolph JW, Taylor SS, Foldy EG. Collaborative off-line reflection: a way to develop skill in action science and action inquiry. In: Reason P, Bradbury H, eds. Handbook of action research: concise paperback edition. London: Sage, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Taylor S, Rudolph JW, Foldy E. Teaching reflective practice in the action science/action inquiry tradition: Key stages, concepts, and practices. In: Reason P, Bradbury H, eds. The SAGE handbook of action research, participative inquiry and practice. London: Sage, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Grant VJ, Robinson T, Catena H, et al. Difficult debriefing situations: a toolbox for simulation educators. Med Teach 2018. 40:703–12. 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1468558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Coan JA, Gottman JM. The Specific Affect Coding System (SPAFF). In: Coan JA, Allen JJB, eds. Handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007:267–85. [Google Scholar]

- 66. McLain Smith D. The elephant in the room. How relationships make or break the success of leaders and organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 67. O’Shea CI, Schnieke-Kind C, Pugh D, et al. The Meta-Debrief Club: an effective method for debriefing your debrief. BMJ Stel 2019:bmjstel-2018-000419. 10.1136/bmjstel-2018-000419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Stone D, Patton B, Heen S. Difficult conversations. New York: Penguin Books, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Porath C. Mastering civility: A manifesto for the workplace. New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hicks JA, Schlegel RJ, Newman GE. Introduction to the special issue: authenticity: novel insights into a valued, yet elusive, concept. Rev Gen Psychol 2019;23:3–7. 10.1177/1089268019829474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Connelly CE, Turel O. Effects of team emotional authenticity on virtual team performance. Front Psychol 2016;7:1336–36. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Woolley AW, Chabris CF, Pentland A, et al. Evidence for a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science 2010;330:686–8. 10.1126/science.1193147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Brown B. Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. London: Penguin, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Krenz HL, Burtscher MJ, Kolbe M. “Not only hard to make but also hard to take:” Team leaders’ reactions to voice. Gruppe. Interaktion. Organisation. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Organisationspsychologie 2019;50:3–13. 10.1007/s11612-019-00448-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Cheng A, Morse KJ, Rudolph J, et al. Learner-Centered Debriefing for Health Care Simulation Education: Lessons for Faculty Development. Simul Healthc 2016;11:32–40. 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Porath CL, Foulk T, Erez A. How incivility hijacks performance: it robs cognitive resources, increases dysfunctional behavior, and infects team dynamics and functioning. Organ Dyn 2015;44:258–65. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Prior M. MiniMax Interventions: 15 simple therapeutic interventions that have maximum impact. Carmarthen, UK: Crownhouse, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjstel-2019-000470supp001.pdf (117.2KB, pdf)