The COVID-19 pandemic has created unprecedented challenges for healthcare teams. In addition to placing a complicated set of demands on governments, health systems, hospitals and individual healthcare workers, this outbreak also serves as ‘an opportunity to gain important information, some of which is associated with a limited window of opportunity’.1 In rapidly evolving pandemics, the imperative to improve performance creates an urgent need for what Amy Edmondson has described as ‘Execution-as-Learning’, a framework in which teams of front-line providers problem solve on the fly, rather than waiting for answers from leadership.2 For many front-line care providers, this threat has created unique challenges, including rapidly evolving information about presentation and management of disease, surges of patients who are critically ill, shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) and other resources and risks to personal safety. While all of us have cared for the ill and dying, and faced the fact that our actions as individuals or teams contribute to our patients’ survival, many feel more personally at risk during the COVID-19 crisis. The development of solutions and innovations that come directly from front-line providers needs to be fostered. To help healthcare workers and their leaders gather and process information about teamwork, medical management and crisis resource management for COVID-19, while also providing support to colleagues, we created Debriefing In Suspected COVid-19 to Encourage Reflection & Team Learning (DISCOVER-TooL, figures 1 and 2).

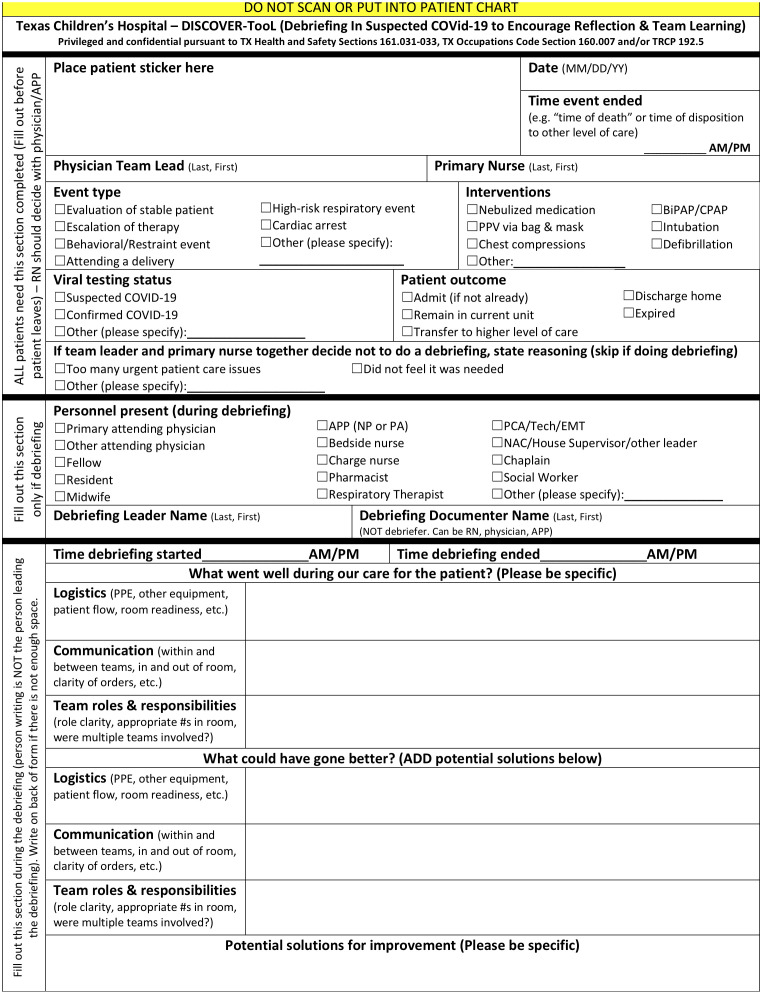

Figure 1.

Debriefing In Suspected COVid-19 to Encourage Reflection & Team Learning (DISCOVER-TooL) clinical event debriefing form, page 1.

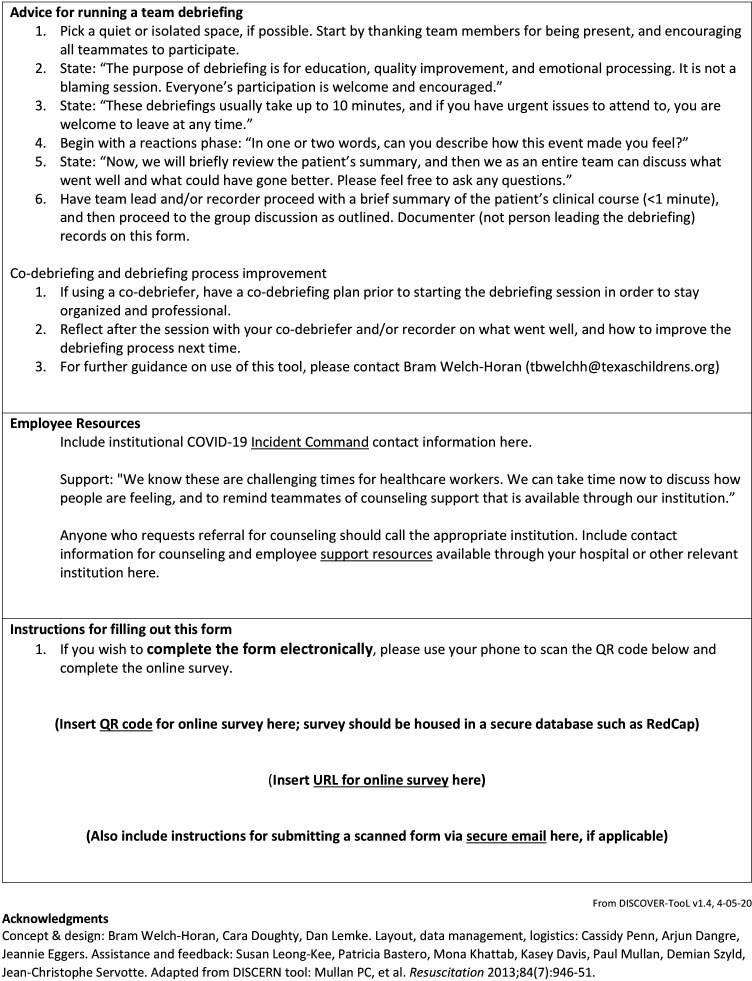

Figure 2.

Debriefing In Suspected COVid-19 to Encourage Reflection & Team Learning (DISCOVER-TooL) clinical event debriefing form, page 2.

Clinical event debriefing allows teams to reflect on high-risk events, identify safety threats and potential solutions and begin processing emotionally challenging events. The Debriefing In-Situ Conversation after Emergent Resuscitation Now (DISCERN) tool was initially developed for use in our paediatric emergency department (ED),3 and has subsequently been modified for broader use in hospital systems.4 The DISCERN tool emphasises psychological safety and creating a safe learning container, multidisciplinary participation and use of a scripted Plus-Delta debriefing methodology to assist teams in debriefing resuscitation events. By adapting the structure of the DISCERN tool to include additional elements specific to COVID-19 concerns, we created a novel clinical debriefing form specifically for COVID-19-related events.

Like DISCERN, the DISCOVER-TooL is intended to aid teams in holding a self-guided debriefing after a clinical event. It includes scripting on how to establish a safe learning container, as well as a Plus/Delta structure to organise a 5–10 min debriefing. Because of the need to disseminate both solutions found and problems encountered in a particular clinical situation to the rest of our institution, data about the event are gathered for quality improvement purposes. Furthermore, the form specifically invites suggestions from clinical team members that can be disseminated to clinical and quality improvement leaders. With the immediate need for timely and practical solutions in mind, DISCOVER-TooL explicitly prompts discussion of logistical issues (such as PPE usage and availability), communication within and between teams, team dynamics (such as role clarity) and psychological distress specific to COVID-19. Such quality improvement conversations carry inherent legal protections in our state, but may vary in other jurisdictions. DISCOVER-TooL also provides information about how team members can self-refer for counselling if they are experiencing psychological distress, and we encourage colleagues elsewhere to point teammates to locally available resources. The form also includes instructions on how to upload data to our secure, online database, as well as how to contact our hospital’s incident command centre for COVID-19; we urge teams elsewhere to consider what data collection and reporting mechanisms would be most effective in their own clinical settings.

DISCOVER-TooL can be used in several ways. A ‘hot debriefing’ could be conducted at the level of one episode of care for one patient, for example, that patient’s time in the ED, within minutes to hours of the completion of that care. Alternatively, the tool could be used for daily postshift huddle debriefings, after the care of one or more patients with COVID-19. Additionally, it could be used for a weekly ‘cold debrief’ in which interconnected teams, such as ED plus intensive care unit, discuss cases in which the teams’ activities intersected. In our institution, our emergency centres have used the DISCOVER-TooL for both ‘hot’ debriefing of single patient episodes of care as well as postshift huddles after multiple patient episodes. Our paediatric intensive care units have used it for both ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ debriefings of single episodes of care, depending on staff availability and competing patient care priorities.

We believe that structured clinical event debriefing practices, such as those using the DISCOVER-TooL, can be used in multiple healthcare contexts. We invite others to adapt the tool and share their work with the global medical community. In recent years, ‘virtual communities of practice’ have expanded throughout healthcare and medical education, facilitating rapid innovation and creative problem solving.5 A bright spot in the otherwise bleak landscape of the COVID-19 crisis has been the growth of social media-based communities rapidly exploring problems such as translational simulation while maintaining physical distancing; the development of new workflows for high-risk clinical activities such as intubation; and educational materials for the rapid orientation of staff deployed outside of their usual clinical areas. Structured clinical event debriefing using forms such as the DISCOVER-TooL could encourage rapid learning both within and across institutions in another example of virtual communities of practice. We encourage healthcare teams to pursue ‘Execution-as-Learning’ while endeavouring to keep themselves and their patients safe in the COVID-19 era.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kelly Wallin, Royanne Lichliter, Joan Shook, Eric Williams, Trudy Leidich and Paul Mullan for their support of this work.

Footnotes

Twitter: @DrBramPedsER, @pemdoc, @caradoughty1

Contributors: The idea for this project was conceived by TBWH and CBD. All authors contributed substantially to the design and execution of the project, as well as to the drafting and revision of the manuscript, including the aforementioned authors, as well as DSL, PB, SLK, MK, JE, CP and AD. All have approved the final version for publication.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Fauci AS, Lane HC, Redfield RR. Covid-19 - Navigating the Uncharted. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1268–9. 10.1056/NEJMe2002387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Edmondson AC. The competitive imperative of learning. Harv Bus Rev 2008;86:60–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mullan PC, Wuestner E, Kerr TD, et al. Implementation of an in situ qualitative Debriefing tool for resuscitations. Resuscitation 2013;84:946–51. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zinns LE, Welch-Horan TB, Moore TA, et al. Implementation of an innovative, Multiunit, Postevent Debriefing program in a children's Hospital. Pediatr Emerg Care 2019. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001898. [Epub ahead of print: 19 Jul 2019]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chan AKM, Nickson CP, Rudolph JW, et al. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia 2020. 10.1111/anae.15057. [Epub ahead of print: 30 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]