Abstract

The Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris 11 chromosome encodes a periplasmic β-lactamase of 30 kDa. Gene replacement and complementation confirmed the presence of this enzyme. Its deduced amino acid sequence shows identity and conserved domains between it and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia L2 and other Ambler class A/Bush group 2 β-lactamases. Southern hybridization detected a single homologous fragment in each of 12 other Xanthomonas strains, indicating that the presence of a β-lactamase gene is common among xanthomonads.

Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris is a gram-negative phytopathogenic bacterium causing black rot in crucifers (25). In a previous study it was found that among 86 strains of X. campestris pv. campestris isolated in Taiwan, 81 were resistant to ampicillin at a level of 50 μg/ml (12a). Antibiotic resistance can be transferred by a bacterium through a variety of mechanisms, including transduction, conjugation, or transfection, and once a resistance gene is transferred, it may be incorporated into the genome or plasmids of the recipient bacterium (16). Since the genus Xanthomonas inhabits soil, infected plants, plant debris, and asymptomatic plants near acutely infected plants, the possibility of widespread ampicillin resistance in this genus raises environmental concerns. In this study, a periplasmic β-lactamase was detected in X. campestris pv. campestris strain 11. The amino acid sequence deduced from the bla gene revealed a high degree of similarity between the β-lactamase of strain 11 and the L2 serine β-lactamase of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (22).

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and DNA techniques.

X. campestris pv. campestris strains 11, 11A, and 17 have been described (26). The other Xanthomonas strains were provided by S.-T. Hsu. Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and L agar (13) were used as general-purpose media with or without ampicillin (50 μg/ml). X. campestris was cultivated at 28°C. The DNA techniques employed were those described by Sambrook et al. (18). DNA sequences were determined by the method of Sanger et al. (19).

Detection of β-lactamase in strain 11.

To determine the cellular location of the β-lactamase, strain 11 cells were fractionated by the method of Osborn and Munson (15), with minor modifications. Proteins from different fractions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Detection of β-lactamase activity in situ was carried out with benzylpenicillin (100 μg/ml) as the substrate, as described by Tai et al. (21). A single protein band in the periplasmic fraction was found to contain β-lactamase activity and was not detected in cytoplasmic, membrane, and extracellular fractions (data not shown). This enzyme, with a molecular mass of 30 kDa as determined by gel electrophoresis, has a size similar to those of other class A β-lactamases detected in gram-negative organisms (3, 8, 20, 22), suggesting that the 30-kDa protein is indeed a β-lactamase.

Antibiotic sensitivity of strain 11.

We carried out MIC determinations according to the microdilution method recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, using β-lactams purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). The MICs determined were as follows (in micrograms per milliliter): cephaloridine, 128; cephalothin, 256; penicillin, 64; ampicillin, 128; carbenicillin; 128; cefotaxime, 8; cefoxitin, 16; oxacillin, 256; and piperacillin, 128. Results indicated that strain 11 was highly resistant to the penicillins and narrow-spectrum cephalosporins used in this study, was less resistant to cefoxitin (an expanded-spectrum cephalosporin), and was susceptible to cefotaxime (a broad-spectrum cephalosporin).

Cloning and sequencing of the strain 11 bla gene.

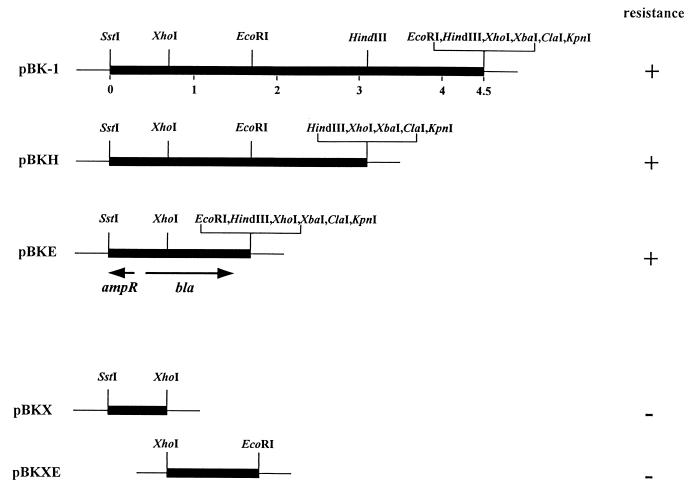

The strain 11 bla gene was cloned, by conferring ampicillin resistance in E. coli DH5α, from a genomic library constructed with pBK-CMV. Deletion mapping located the bla gene in the 1.7-kb SstI-EcoRI fragment (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Localization of the β-lactamase gene of X. campestris pv. campestris strain 11. Plasmid pBK-1 contains a 4.5-kb Sau3A1 insert cloned into the multiple cloning sites of vector pBK-CMV. For deletion mapping, the 3.1-kb SstI-HindIII fragment, the 1.7-kb SstI-EcoRI fragment, the 0.8-kb SstI-XhoI fragment, and the 0.9-kb XhoI-EcoRI fragment from the pBK-1 insert were subcloned into the compatible sites of pBK-CMV to generate pBKH, pBKE, pBKX, and pBKXE, respectively. +, transformants resistant to ampicillin; −, transformants sensitive to ampicillin.

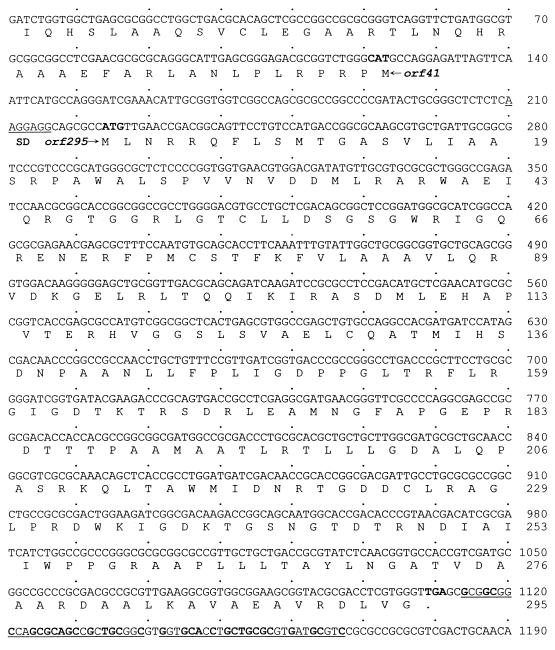

Sequence analysis of this 1.7-kb fragment revealed two open reading frames, orf295 and orf41, with opposite orientations (Fig. 2). orf295 (nucleotides [nt] 224 to 1111) potentially encoded a protein of 295 amino acids with an estimated molecular weight of 31,810. A Shine-Dalgarno sequence (AAGGAGG) was found 8 nt upstream of the orf295 initiation codon. Downstream from the orf295 termination codon (nt 1114 to 1167) were two inverted repeat sequences resembling a transcriptional termination signal (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence (1,190 bp) of the upstream region of the pBKE insert. The deduced amino acids are represented by one-letter codes. Initiation and stop codons are boldfaced. The underlined regions (bp 1114 to 1139 and bp 1142 to 1167) are inverted repeats which potentially form a stem-loop structure resembling a transcription termination signal. Boldfaced letters in the repeats (16 out of 26 nucleotides in each region) represent the complementary bases. SD, ribosome-binding sequence.

orf41 (nt 1 to 123) is an incomplete open reading frame (Fig. 2). Its deduced amino acid sequence (41 residues) had 51% identity to the N-terminal regions of the AmpR proteins (required for the induction of β-lactamases) from Citrobacter freundii (11), Enterobacter cloacae (14), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (12), and Proteus vulgaris (6). Based on the sequence identity, we predicted that orf41 was the 5′ portion of the strain 11 ampR. The intergenic region between orf295 and orf41 (100 nt) did not contain the consensus sequences that are typical of the −35 and −10 regions of an Escherichia coli promoter (Fig. 2).

The strain 11 bla gene had a G+C content of 68.2%, and G and C were likely to appear in the third positions of the codons. The similarities between it and other X. campestris chromosomal genes (4) confirm that the strain 11 bla gene is indigenous.

Computer analysis indicated that the strain 11 β-lactamase has a signal peptide (17) of 22 residues (Fig. 2), consistent with the observation that the enzyme is a secretory protein destined for the periplasm and that, after processing, with the cleaved region being between Phe 22 and Ala 23, the mature protein would consist of 273 amino acids with a pI of 8.2 and a molecular weight (29,408) similar to that observed after sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (data not shown).

Sequence comparison and classification of the strain 11 β-lactamase.

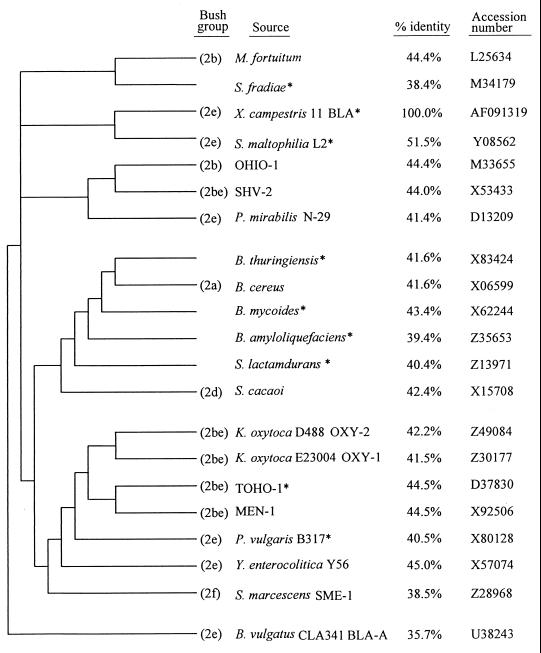

Several schemes have been proposed for the classification of bacterial β-lactamases. Ambler (1) suggested a scheme containing four classes of β-lactamases based on primary amino acid sequences. The most recent functional scheme by Bush et al. (5) considered the inhibition characteristics, substrate profiles, and molecular structures of the enzymes. Based on these parameters, they constructed a dendrogram showing relationships among 88 β-lactamases. In this study, we constructed a dendrogram that clusters the strain 11 β-lactamase with 20 other related sequences, including sequences which were not included in the dendrogram of Bush et al. (5). The highest degree of relatedness to the strain 11 β-lactamase was found in the L2 serine β-lactamase from S. maltophilia, an Ambler class A enzyme which falls in group 2e of the Bush scheme (Fig. 3). Consistent with this finding, the strain 11 β-lactamase has the highest degree of identity (51.5%) with S. maltophilia L2 (22) and lower degrees with several other class A/group 2 enzymes: Yersinia enterocolitica BLA-A (45.0%), E. coli TOHO-1 (44.5%), and E. coli MEN-1 (44.5%) (2, 3, 8, 20) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Dendrogram of β-lactamases based on the sequence similarity between the strain 11 β-lactamase and the 20 other sequences most closely related. The signal sequences were not included for comparison. Asterisks indicate the sequences not included in the dendrogram of Bush et al. (5). The Genetics Computer Group package was used for the construction.

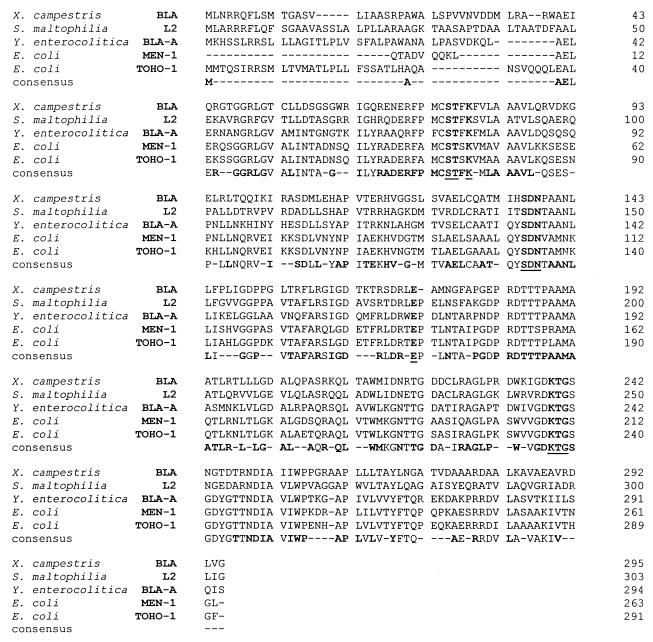

The conserved sequences present in the class A enzymes, including the consensus sequences STXK, SDN, and KTG and the highly conserved glutamic acid residue located 34 residues downstream from the SDN loop, are also found in the strain 11 β-lactamase (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of the class A β-lactamases from gram-negative bacteria S. maltophilia L2 (22), Y. enterocolitica BLA-A (20), E. coli TOHO-1 (8), and E. coli MEN-1 (2, 3). The consensus line displays the residues conserved in the sequences, with the boldfaced letters indicating the residues conserved in the strain 11 β-lactamase. The consensus sequences STXK, SDN, KTG and the glutamic acid residue located 34 residues behind the SDN loop are underlined. The Genetics Computer Group package was used in these analyses.

Northern blot analysis.

The 317-bp XhoI-NotI fragment (bp 734 to 1050; Fig. 2) within the strain 11 bla gene was used as the probe for Northern hybridization with the RNA prepared from strain 11 cells grown in LB medium and treated with ampicillin 30 min prior to RNA extraction (24). A hybridization band of ca. 980 nt, with smearing in the lower area of the gel, was detected (data not shown). This transcript, having a size similar to that of the bla gene, appears to be monocistronic.

Construction of the bla mutant strain 11bla::Tc and complementation test.

Mutation in strain 11 bla was performed according to Lee et al. (10). A 2.0-kb tetracycline resistance (Tcr) cartridge from mini-Tn5Tc (7) was inserted into the SmaI site of the pBKE insert. The interrupted bla gene was electroporated into strain 11 (23), followed by replacement of the chromosomal wild-type version. One of the tetracycline-resistant (15 μg/ml) and ampicillin-sensitive mutants (strain 11bla::Tc) thus obtained was verified by Southern hybridization to have undergone double crossover.

The 1.7-kb SstI-EcoRI fragment containing the complete bla sequence was cloned into the broad-host-range vector pRK415 (9), resulting in pRKSE. Strain 11bla::Tc carrying pRKSE regained ampicillin resistance, indicating that the 1.7-kb SstI-EcoRI fragment indeed encodes a β-lactamase.

Distribution of bla gene among xanthomonads.

Thirteen other strains of X. campestris, representing eight pathovars and one Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae strain, were tested for resistance by being grown on LB agar containing ampicillin. All strains except X. campestris pv. mangiferaeindicae strain 38 were found to be ampicillin resistant. Southern hybridization revealed that for each of the EcoRI fragments of chromosomal DNA from these X. campestris strains, except strain 38, for which no signal was observed, a single band was detected. A 3.8-kb fragment was detected in X. campestris pathovars campestris (strains 2, 6, 11A, 17, and 85), begoniae (strain 59), dieffenbachiae (strain 65), and phaseoli (strain 73); a 10-kb fragment was detected in pathovars citri (strain 60), glycines (strain 69), and vesicatoria (strain 64); and a 5.5-kb fragment was detected in X. oryzae pv. oryzae (strain 21). Since only one fragment was detected, it is likely that only one copy of the bla gene is present in each of these Apr strains. These results indicate that the bla genes are highly homologous and widespread among xanthomonads.

Conclusion.

In this study, we have identified a novel β-lactamase from X. campestris, a plant-pathogenic bacterial species presently not involved in human or animal pathology. In addition, the presence of a β-lactamase gene has been demonstrated to be widespread among xanthomonads. It is thought that unusual β-lactamases produced by human pathogens are acquired from some other sources; the occurrence of this enzyme in the botanical world suggests one of the possible novel origins.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence determined here has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF091319.

Acknowledgments

We thank S.-T. Hsu for donating Xanthomonas strains and M.-T. Yang for providing the genomic bank of strain 11. We also thank S. T. Liu for a critical reading of the manuscript.

This study was supported by grant no. NSC-87-2311-B005-013-B15 from the National Science Council of the Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambler R P. The structure of β-lactamase. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 1980;289:321–331. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1980.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barthelemy M, Peduzzi J, Bernard H, Tancrede C, Labia R. Close amino acid sequence relationship between the new plasmid-mediated extended spectrum β-lactamase MEN-1 and chromosomally encoded enzymes of Klebsiella oxytoca. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1122:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(92)90121-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauernfeind A, Stemplinger I, Jungwirth R, Ernst S, Casellas J M. Sequences of β-lactamase genes encoding CTX-M-1 (MEN-1) and CTX-M-2 and relationship of their amino acid sequences with those of other β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:509–513. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradbury J F. Genus II. Xanthomonas Dowson 1939, 187.AL. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1984. pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush K, Jacoby G A, Medeiros A E. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1211–1233. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datz M, Joris B, Azab E A M, Galleni M, Van Beeumen J, Frere J-M, Martin H H. A common system controls the induction of very different genes. The class-A β-lactamase of Proteus vulgaris and the enterobacterial class-C β-lactamase. Eur J Biochem. 1994;226:149–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb20036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis K N. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishii Y, Ohno A, Taguchi H, Imajo S, Ishiguro M, Matsuzawa H. Cloning and sequence of the gene encoding a cefotaxime-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase isolated from Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2269–2275. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keen N T, Tamaki S, Kobayashi D, Trollinger D. Improved broad-host-range plasmids for DNA cloning in Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1988;70:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee T-C, Lin N-T, Tseng Y-H. Isolation and characterization of the recA gene of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;221:459–465. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindquist S, Lindberg F, Normark S. Binding of the Citrobacter freundii AmpR regulator to a single DNA site provides both autoregulation and activation of the inducible ampC β-lactamase gene. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3746–3753. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3746-3753.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lodge J M, Minchin S D, Piddock L J V, Busby S J W. Cloning, sequencing and analysis of the structural gene and regulatory region of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa chromosomal ampC β-lactamase. Biochem J. 1990;272:627–631. doi: 10.1042/bj2720627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12a.Mao, J.-R., and Y.-H. Tseng. Unpublished data.

- 13.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naas T, Nordmann P. Analysis of a carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A β-lactamase from Enterobacter cloacae and of its LysR-type regulatory protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7693–7697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osborn M J, Munson R. Separation of the inner (cytoplasmic) and outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1974;31:642–653. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(74)31070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitout J D D, Sanders C C, Sanders W E., Jr Antimicrobial resistance with focus on β-lactam resistance in gram-negative bacilli. Am J Med. 1997;103:51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pugsley A P. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seoane A, Garcia Lobo J M. Nucleotide sequence of a new class A β-lactamase gene from the chromosome of Yersinia enterocolitica: implications for the evolution of class A β-lactamases. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;228:215–220. doi: 10.1007/BF00282468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tai P C, Zyk N, Citri N. In situ detection of β-lactamase activity in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1985;144:199–203. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsh T R, MacGowan A P, Bennett P M. Sequence analysis and enzyme kinetics of the L2 serine β-lactamase from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1460–1464. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang T-W, Tseng Y-H. Electrotransformation of Xanthomonas campestris by RF DNA of filamentous phage φLf. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1992;14:65–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1992.tb00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weng S-F, Liu Y-L, Lin J-W, Tseng Y-H. Transcriptional analysis of the threonine dehydrogenase gene of Xanthomonas campestris. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240:523–529. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams P H. Black rot: a continuing threat to world crucifers. Plant Dis. 1980;64:736–742. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang B-Y, Tseng Y-H. Production of exopolysaccharide and levels of protease and pectinase activity in pathogenic and non-pathogenic strains of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Bot Bull Acad Sin. 1988;29:93–99. [Google Scholar]