Abstract

Background

The Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS) programme is an evidence-based approach to teamwork training. In-person education is not always feasible for medical student education. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of online, interactive TeamSTEPPS simulation versus an in-person simulation on medical students’ TeamSTEPPS knowledge and attitudes.

Methods

Fourth-year medical students self-selected into an in-person or online training designed to teach and evaluate teamwork skills. In-person participants received didactic sessions, team-based medical simulations and facilitated debriefing sessions. The online group received an equivalent online didactic session and participated in an interactive software-based simulation with immediate, personalised performance-based feedback and scripted debriefing. Both trainings used three iterations of a case of septic shock, each with increasing medical complexity. Participants completed a demographic survey, a preintervention/postintervention TeamSTEPPS Benchmarks test and a retrospective preintervention/postintervention TeamSTEPPS teamwork attitudes questionnaire. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics and repeated measures analysis of variance.

Results

Thirty-one students (18 in-person, 13 online) completed preintervention/postintervention surveys, tests and questionnaires. Gender, age and exposure to interprofessional education, teamwork training and games were similar between groups. There were no statistical differences in preintervention knowledge or teamwork attitude scores between in-person and online groups. Postintervention knowledge scores increased significantly from baseline (+2.0% p=0.047), and these gains did not differ significantly based on whether participants received in-person versus online training (+1.5% vs +2.9%; p=0.49). Teamwork attitudes scores also showed a statistically significant increase with training (+0.9, p<0.01) with no difference in the effect of training by group (+0.8 vs +1.0; p=0.64).

Conclusions

Graduating medical students who received in-person and online teamwork training showed similar increases in TeamSTEPPS knowledge and attitudes. Online simulations may be used to teach and reinforce team communication skills when in-person, interprofessional simulations are not feasible.

Keywords: teamwork training, pediatric simulation, interprofessional teams, simulation for teamwork training

What is already known on this subject.

Communication failure is a leading cause of patient harm.

Teamwork training improves team performance and patient outcomes.

What this study adds.

An asynchronous, individual online simulation-based training for fourth-year medical students is associated with similar increases in Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety knowledge and attitudes compared with in-person training sessions.

Introduction

Communication failure is the leading cause of inadvertent patient harm, accounting for up to 70% of sentinel events, near misses and close calls.1 2 Individual and systemic factors must be addressed in order to improve patient safety outcomes. Previous studies have identified shared mental models, mutual respect and trust, and closed-loop communication as the underpinning conditions required for effective teams.3 Effective communication and teamwork skills are thus essential for graduating medical students. The ability to engage effectively with the interprofessional team is one key factor that differentiates the resident who struggles and the one who succeeds in making the transition to residency.

Teamwork training improves team performance and patient outcomes.4 5 The Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS) programme was developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) as an evidence-based approach to teamwork training. It is built on five key principles identified as essential for teams: leadership, team structure, situation monitoring, communication and feedback.6–8 It is taught through didactic sessions, simulation and/or case-based discussions. In-person simulation-based training supports the acquisition of TeamSTEPPS communication and teamwork skills and has been shown to improve attitudes related to team communication and structure, situation monitoring, mutual support, motivation, self-efficacy and role clarity.9–11

The University of Washington (UW) School of Medicine’s Capstone course, Transition to Residency Series, is a brief course for graduating students intended as a final preparation for students as they graduate. Every year, UW medical, nursing and pharmacy students are offered a half-day training session on interprofessional communication and teamwork based on the TeamSTEPPS programme. Ten half-day sessions (six internal medicine, three paediatrics and one obstetrics) are offered each year. The sessions feature an introductory lecture followed by specialty-specific clinical simulations facilitated by over 30 faculty members with the assistance of four simulation technologists. Simulation-based education is thought to support the acquisition and practice of knowledge and skills through Kolb’s learning cycle by allowing students to actively engage in concrete experience, reflection, conceptualisation and experimentation.12 Medical students have reported that the course is valuable in preparation for residency training in previous course evaluations collected immediately after participation.

While in-person simulations have been well received by learners, they are time-intensive and personnel-intensive and not widely accessible to all students. Faculty and space constraints limit half of participants to the observer role, which may impact learning. Additionally, there is a significant investment of time and effort required by faculty. Despite the efforts of faculty, many students are still unable to attend the sessions due to geographic and scheduling limitations.

The UW School of Medicine trains physicians to care for patients and communities in the states of Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana and Idaho (WWAMI) through the WWAMI regional medical education programme. The large geographical area covered by the programme creates logistical and travel challenges that leave many students without an opportunity to participate in in-person TeamSTEPPS training sessions that are only available at the main campus located in Seattle, Washington, USA. Computer-based simulations may overcome these barriers to interprofessional teamwork training by providing an alternative learning strategy to engage students in Kolb’s learning cycle, allowing the asynchronous acquisition and practice of communication and teamwork skills through interactive cases requiring identification and implementation of communication skills and response-specific feedback.

Previous studies have shown online training in teamwork skills to be comparable in effectiveness to in-person simulation. This training modality offers a convenient, realistic approach to interprofessional simulation that is well received by learners and improves teamwork attitudes.13–15 Given the promise of online, computer-based simulation and its potential to benefit health professional students across the WWAMI region, the current pilot study had three aims:

Provide learners with the TeamSTEPPS framework.

Provide learners with the opportunity to practice using TeamSTEPPS tools using an online simulation built with software compatible with learning management systems.

Evaluate the knowledge and attitudes of learners participating in the online simulation.

Methods

Study design

This was a prospective pilot study comparing a novel, online didactic session and interactive simulation-based module with a standard, in-person didactic session and simulation-based course. The study population was a convenience sample of fourth-year medical students in their capstone course who participated in either the standard, in-person training or a novel, online educational session. Students from all campus sites including the primary campus, who had been accepted into paediatric residencies, were required to participate in one of the educational sessions as part of their course requirements (n=31) and were also invited to participate in the research study by completion of the preintervention and postintervention surveys, tests and questionnaires. Participation in the educational activities and study was optional for students who matched into family medicine (n=37) and emergency medicine (n=20). The educational sessions focused on using TeamSTEPPS principles in the care for a paediatric patient with neutropenia and septic shock.

Standard educational intervention

Historically, UW medical, nursing, pharmacy and physician assistant students have participated in a half-day training session on interprofessional communication and teamwork based on the TeamSTEPPS programme. This course uses an experiential learning theory framework, which allows participants to reflect on concrete experiences and apply new skills and strategies during subsequent iterations. The objectives of the course were to identify and demonstrate TeamSTEPPS tools and principles while working as part of an interprofessional team. Sessions specifically using a simulated paediatric patient were offered to students who were entering into paediatric, family medicine or emergency medicine residencies.

The traditional course required in-person attendance to a session offered only at the main campus in Seattle, Washington, USA on an annual basis. It included a 40 min long interactive didactic session introducing and reviewing TeamSTEPPS principles and a 10-min lecture on the management of septic shock. Students were then separated into three teams, each consisting of medical, nursing and pharmacy students. Each team participated in simulations within a simulated emergency department room using a combination of a SimJunior patient simulator (Laerdal Medical; Stavanger, Norway) and a trained standardised parent. Each scenario began with the same stem involving a child with known neutropenia secondary to chemotherapy and new-onset fever. With each iteration, the case became more medically complex, requiring more medical interventions including a greater number of fluid boluses and initiation of vasoactive medications in order to stabilise the patient. Cases were designed to require the use of specific TeamSTEPPS communication tools and behaviours (table 1). All students functioned within their professional roles, and a faculty facilitator for each profession was available at the bedside to help provide any technical guidance related to role-specific equipment. Students not actively participating in the simulation observed remotely and participated in the facilitated, structured debriefings led by simulation and TeamSTEPPS experts.

Table 1.

Progressive levels of complexity in teamwork skills targeted by in-person and online simulations

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| SBAR | Brief | Two-challenge rule |

| Checkback | Huddle | CUS |

| Call out |

CUS, concerned, uncomfortable, safety issue; SBAR, situation, background, assessment, recommendation.

Novel educational intervention

The online training was designed to be used remotely, independently and asynchronously by learners. We developed a 30 min recorded lecture on TeamSTEPPS principles and a 10 min review of the medical care of neutropenia and septic shock in a paediatric patient in alignment with the teaching given during in-person didactic sessions. This was followed by a software simulation designed to teach and evaluate specific teamwork skills. The online simulation was developed using Storyline e-learning software (Articulate; New York, New York City, USA) using instructional design principles with identified learning objectives and an iterative design process applied in previous work.13 Similar to the in-person simulation, learners participated in three iterations of a simulated case requiring the management of a paediatric patient with septic shock, each with an increased level of medical and communication-related complexity. Non-player characters served as interprofessional team members for participants to interact with, receive information from, and to join in the debriefing. Standardised scripted team members represented nurses, a parent, pharmacist and attending physician. While the child character did not interact with the learner, he was represented by a child-sized mannequin with interchangeable overlays including relevant medical equipment requested by the learner. Learners were required to select medical interventions, identify TeamSTEPPS-specific skills and behaviours in the scripted communication between characters, and demonstrate leadership behaviours by engaging in collaborative communication with their team. The software programme provided the learners with immediate performance-based feedback after each case based on their medical and communication selections during the scenario and a prescripted summary of the key concepts focused on with the iteration (figure 1a and b). The software programme also compiled deidentified aggregate user metrics such as time of access and total time spent interacting with the software.

Figure 1.

Examples from Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety online simulation. SBAR, situation, background, assessment, recommendation.

Initial pilot data were collected from four graduating medical students in the 2016–2017 academic year during a trial phase. Usability data were collected from three additional volunteer medical students prior to rollout, and the module was revised based on participant feedback.

Evaluation

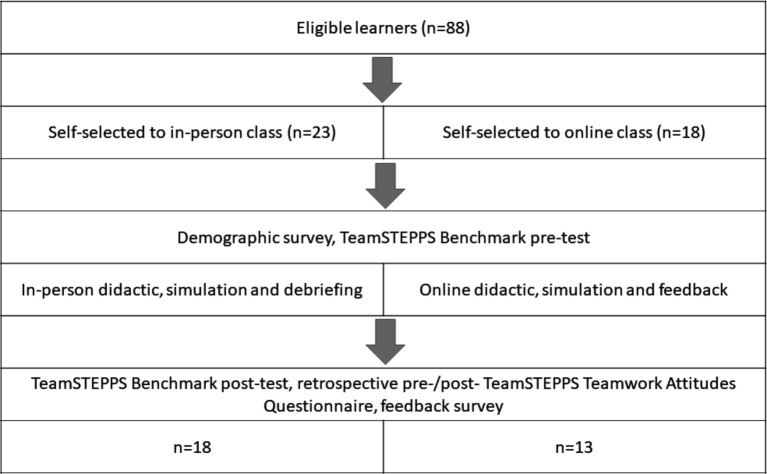

Participants in both groups were asked to complete surveys, questionnaires and tests online before and after participation in the educational sessions. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at UW.16 Consent was obtained electronically at the start of the initial survey. Self-reported demographic data were collected from all learners in the preintervention survey. All participants were asked to complete the TeamSTEPPS Benchmarks test before and after participation in the learning sessions. This 23-item knowledge-based, multiple choice test is part of the AHRQ TeamSTEPPS training curriculum.17 They were also asked to complete the TeamSTEPPS teamwork attitudes questionnaire (T-TAQ) as a retrospective preintervention/postintervention test after completing the sessions. The T-TAQ is a previously validated 30-item questionnaire that measures individuals' attitudes towards teamwork behaviours related to patient care and safety by assessing agreement with statements related to the five core domains of TeamSTEPPS (team structure, leadership, situation monitoring, mutual support and communication). This tool was created by AHRQ and has been used to assess teamwork attitudes in practicing health professionals and students.18 19 After participation, learners also rated their agreement using a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 3=neutral, 5=strongly agree) with statements regarding the quality of different components of the sessions and their opinion as to whether participating had educational value. Students participating in the online simulation rated their agreement with additional statements related to the ease of use and perceived quality of the programme. Students in both groups rated their agreement with statements assessing whether they would use the training modality again and whether the session contributed to the enhancement of understanding other professions’ roles and responsibilities. They also had the opportunity to answer open-ended questions and comment on the sessions. See figure 2 for an overview of the study design.

Figure 2.

Study flow diagram. TeamSTEPPS, Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety.

Data analysis

Demographics and participants’ feedback data are summarised by group (online vs in-person) using descriptive statistics, including counts and percentages for categorical data and means and SD for continuous data.

Benchmarks test scores (% correct out of 23-item assessment) were summarised by time period (preintervention vs postintervention) and by group using means and SD. T-TAQ responses were summarised by aggregate score and domain by time and group using means and SD. For in-person participants, the question ‘Teams that do not communicate effectively significantly increase their risk of committing errors’ was omitted from the communication domain scoring as no response data were collected for this question due to an error in the questionnaire collection tool. Within-subject and between group differences in Benchmarks test and T-TAQ scores preintervention versus postintervention for online and in-person participants were assessed using repeated measures analysis of variance. The interaction between group membership and time was also assessed. An α of 0.05 was used for significance testing. Participant agreement to statements was expressed as a mean Likert Score with SD.

Results

A total of 41 learners participated in the learning activities, 31/31 (100%) of those entering into paediatrics, 8/37 (22%) entering family medicine and 2/20 (10%) entering into emergency medicine. Twenty-three students (56%) opted for the in-person session while 18 (44%) participated in the online group. Eighteen of the 23 (78%) students in the in-person session completed all of the preintervention and postintervention surveys, questionnaires and tests while 12 of the 18 (67%) of the online participants completed the preintervention and postintervention Benchmarks test. One additional student in the online group completed the preintervention and postintervention surveys and T-TAQ but not the Benchmarks test. Participant demographics were similar between groups with the exception being that the online group contained a higher proportion of students pursuing a career in family medicine (table 2).

Table 2.

Demographics of study participants

| In-person (n=18) | Online (n=13) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 27.9 (2.0) | 28.7 (2.0) |

| Gender (% female), n (%) | 14 (77.8%) | 8 (61.5%) |

| Site, n (%) | ||

| Seattle, Washington | 7 (38.9%) | 7 (53.9%) |

| Spokane, Washington | 5 (27.8%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| Anchorage, Alaska | 2 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Bozeman, Montana | 3 (16.7%) | 3 (23.1%) |

| Moscow, Idaho | 1 (5.6%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| Type of residency accepted into, n (%) | ||

| Paediatrics | 17 (94.4%) | 6 (50.0%) |

| Family medicine | 1 (5.6%) | 5 (38.5%) |

| Emergency medicine | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| Interprofessional education sessions in past year, n (%) | ||

| None | 3 (16.7%) | 4 (30.8%) |

| 1–2 | 7 (38.9%) | 5 (38.5%) |

| 3–4 | 4 (22.2%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| 5–9 | 3 (16.7%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| ≥10 | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Time since last teamwork training course, n (%) | ||

| <6 months | 4 (22.2%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| 6–12 months | 7 (38.9%) | 5 (38.5%) |

| >12 months | 7 (38.9%) | 6 (46.2%) |

| No previous teamwork training | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| Frequency of computer game use, n (%) | ||

| 5 or 6 times a week | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| A couple of times a month | 3 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Less than once a month | 2 (11.1%) | 4 (30.8%) |

| Never | 13 (72.2%) | 8 (61.5%) |

For the online group, 54% (n=7) of participants participated in the same city as the main medical school campus while 46% (n=6) of the learners participated remotely from other sites within the WWAMI region. Most of the 18 students who selected the online simulation session (66.7%, n=12) accessed the module outside of standard classroom hours (17:00–08:00). The mean time spent engaging with the online simulation was 28.2 min (SD 19.0).

TeamSTEPPS Benchmarks test scores increased significantly from preintervention to postintervention (in-person: 92.5%–94.0%; online: 91.7%–94.6%; overall 92.2%–94.2% p=0.047). The effect of the intervention did not differ based on whether it was delivered in-person versus online (p=0.5).

One item from the communication domain of the T-TAQ contained missing data, and we were therefore unable to analyse this item. Aggregate scores (out of 29) improved for participants overall (in-person: 22.4–23.2; online: 22.6–23.6; overall 22.5–23.4, p<0.001) with no statistically significant difference in improvement by group (p=0.6). Although we were unable to assess changes in the communication domain, there was improvement seen across all remaining domains of the T-TAQ in both groups. There was no difference in the amount of change between groups (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Presession and postsession Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS) teamwork attitudes questionnaire (T-TAQ) scores for in-person and online groups. ‡Significant change in preintervention and postintervention T-TAQ scores for both groups.

Feedback on both training modalities was positive. Most participants, 92% (n=12), reported that they would use the online module again, and 94% of the in-person participants who reported the same. When asked to quantify their agreement with the statement ‘The workshop enhanced my understanding of other professions' roles and responsibilities’, the average score for online participants was 3.8 (SD 0.8) and 4.4 (SD 0.5) for the in-person group. In the online group, 77% (n=10) reported no technical errors during the online simulation. Reported technical difficulties included inability to run on specific web browsers and lag time after making selections. See table 3.

Table 3.

Feedback from participants of online educational session (5-point Likert scale; 1=strongly disagree, 3=neutral, 5=strongly agree), n=13

| Statement | Mean Likert Score (SD) |

| The module was useful and practical. | 4.0 (0.8) |

| I learned new skills. | 4.0 (0.7) |

| I was sufficiently oriented to the technology. | 4.2 (0.9) |

| Enhanced my understanding of other professions’ roles and responsibilities. | 3.8 (0.8) |

| The scenarios were appropriate to my level of training. | 4.4 (0.7) |

| The lecture on pediatric septic shock was excellent. | 4.2 (0.6) |

| The lecture on TeamSTEPPS principles was excellent. | 4.0 (0.6) |

| The online simulation was easy to access. | 4.2 (1.2) |

| The online simulation was easy to navigate. | 3.4 (1.3) |

| The online simulation had realistic graphics. | 3.3 (1.1) |

| The online simulation provided valuable feedback. | 3.5 (1.1) |

TeamSTEPPS, Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety.

Discussion

In this study, we found that teamwork knowledge and attitude scores were similar between graduating medical students who received an in-person educational session, including group simulation-based training, compared with an online training using software-based simulations featuring a non-player character interprofessional team. With this novel educational intervention, learners were able to access content both after traditional in-class educational hours and from remote sites where in-person sessions were not available, offering an expanded group of students the opportunity to engage with the educational content and practice identifying and using TeamSTEPPS tools. This study demonstrated that online-asynchronous simulation-based training is a viable alternative to in person training to address knowledge and attitudes related to interprofessional teamwork.

Strong teamwork and communication skills are imperative for the delivery of safe patient care, especially in high-stakes situations. TeamSTEPPS was specifically developed to provide healthcare providers with evidence-based tools aimed at creating and supporting high performing teams in order to improve patient outcomes.20 However, there are challenges to efficient and effective teamwork training at the undergraduate medical student level. Students may not have the opportunity to practice or play active roles in acute situations requiring advanced communication and teamwork skills and are instead often assigned to an observatory or data-gathering role. When offered the opportunity to practice in simulation-based scenarios, other interprofessional members of the team may not be available, diminishing the realism in regards to role assignment, responsibility and communication. The large amount of resources it requires to offer interprofessional simulations to the entire student body may not be feasible.

While healthcare professionals function as members of an interdisciplinary team, they are often trained in silos. Interprofessional training for professional students leads to increased understanding of other team members’ roles and responsibilities.21 Simulation-based interprofessional education has been reported as the preferred approach for coeducation, and it has been shown to correlate with improved teamwork knowledge and attitudes with professional students.22 23 Having students train within their role gives them the opportunity to self-identify communication strategies that will aid them in their future working environment. Debriefing with students from other roles allows them to hear perspectives on how the team fits together and adds insight into the needs of other team members.

While many curricular methods may be employed to teach these skills and behaviours, deliberately practicing and reflecting on their use provides learners with the contextual experience needed for actual practice. In particular, Kolb’s experiential learning theory postulates that learning occurs through concrete experiences, reflection, abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation.12 Simulation, therefore, serves as an ideal method through which learners may engage in clinical experiences, reflect on their performance and gaps, strategises different approaches and implement these changes all without putting patients at risk. Simulation has, in fact, been shown to lead to improved patient outcomes in a variety of settings.24–29 When used for TeamSTEPPS training, it has also been shown to be associated with improved clinical outcomes.30 31

While interprofessional simulation-based training would ideally occur during in-person so that learners may actually practice skills face to face with members of the interprofessional care team, the use of immersive scenario-based simulation may not always be available. In low-resource settings or institutions where in-person interprofessional training may not be feasible, remote simulation facilitation and debriefings are possible.32 This, however, still requires simulation equipment, facilitators and a complete cadre of participants to be available at a designated time. Web-based simulations offer the ability of individual participants to engage from remote locations asynchronously and with only a computer and internet access for equipment.

Limitations

This was a pilot study looking at the feasibility and impact of an online, educational intervention including an interactive simulation representing the work of an interprofessional team and therefore, the overall number of participants was small. Due to logistical constraints, students self-selected into their experimental groups. While this created a potential for bias, with a possibility of differences between groups in their baseline characteristics, experiences, and motivation, geographically-remote students were the target audience for online training. We did observe a ceiling effect as both T-TAQ and Benchmarks test scores were high in both groups before the intervention. As T-TAQ scores were high in both groups to begin with, a difference of approximately 1 point was seen in both groups. Although small, we did see improvements of similar magnitudes for both learners in the in-person and online groups.

Learning teamwork as an individual has its obvious limitations, but our curriculum incorporated virtual, scripted team members to illustrate opportunities for interprofessional teamwork. Students received real-time feedback on their knowledge and skill, and instructors were able to review performance and engagement data in order to provide feedback either in real-time or at a more convenient time.

Next steps

Given the success for this initial pilot study, we look forward to expanding the distribution and application of the educational module and improving evaluation methods. With changes to the educational landscape due to the COVID-19 pandemic and constraints on in-person training, online and virtual simulation will likely have a larger role in the training of healthcare professionals. Additional research assessing whether participation in this online TeamSTEPPS training is associated with higher teamwork and communication scores in simulated and actual clinical practice is warranted. Future directions also include improving the preintervention/postintervention electronic evaluation tools and expanding access to other professional groups. This educational package could also potentially be used as a refresher tool for individuals who have participated in an in-person session previously. Finally, we may develop additional cases in order to allow for novel options for retraining and reinforcement of core TeamSTEPPS principles.

Conclusions

Graduating medical students who received in-person and online teamwork training showed a comparable increase in TeamSTEPPS knowledge and attitudes as assessed by the TeamSTEPPS Benchmarks test and T-TAQ. Online simulations may be used to teach and reinforce team communication skills when live, interprofessional simulations are not feasible or convenient. This methodology should be further explored as a means to expand the reach of important educational opportunities to areas without in-person simulation capacity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Genevieve Paglilauan, MD for her support in implementation and Sara Kim, PhD for her contributions to the curriculum.

Footnotes

Presented at: This work was presented in part at the 2018 International Meeting on Simulation in Healthcare, the 2018 American Heart Association Team Training National Conference, and the 2018 and 2019 International Pediatric Simulation Symposia and Workshops.

Contributors: RB, MG and RU made substantial contributions to the conception and design of work, as well as the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. DP made substantial contributions to the acquisition and analysis of data. AS made significant contributions to the conception and design of the work and acquisition of data. All authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and critical revision. All authors have approved the final version.

Funding: This project was supported by a grant from the University of Washington School of Medicine Center for Leadership and Innovation in Medical Education.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Deidentified participant data is not available for sharing outside of our institution.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the UW Institutional Review Board (approval #STUDY00001772).

References

- 1. Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13 Suppl 1:i85–90. 10.1136/qshc.2004.010033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med 2004;79:186–94. 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weller J, Boyd M, Cumin D. Teams, tribes and patient safety: overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgrad Med J 2014;90:149–54. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Umoren RA, Poore JA, Sweigart L, et al. TeamSTEPPS virtual teams: interactive virtual team training and practice for health professional learners. Creat Nurs 2017;23:184–91. 10.1891/1078-4535.23.3.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Umoren RA, Scott PJ, Sweigart L. A comparison of teamwork attitude changes with virtual TeamSTEPPS® simulations in health professional students. J Interprof Educ Prac 2018;10:51–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clancy CM, Tornberg DN. TeamSTEPPS: assuring optimal teamwork in clinical settings. Am J Med Qual 2007;22:214–7. 10.1177/1062860607300616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dingley C, Daugherty K, Derieg M. Improving patient safety through provider communication strategy enhancements. agency for healthcare research and quality. Advances in patient safety: new directions and alternative approaches 2016;3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sawyer T, Laubach VA, Hudak J, et al. Improvements in teamwork during neonatal resuscitation after interprofessional TeamSTEPPS training. Neonatal Netw 2013;32:26–33. 10.1891/0730-0832.32.1.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brock D, Abu-Rish E, Chiu C-R, et al. Republished: interprofessional education in team communication: working together to improve patient safety. Postgrad Med J 2013;89:642–51. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-000952rep [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tofil NM, Morris JL, Peterson DT. Interprofessional Im simulation course. J Hosp Med 2014;3:189–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robertson B, Kaplan B, Atallah H, et al. The use of simulation and a modified TeamSTEPPS curriculum for medical and nursing student team training. Simul Healthc 2010;5:332–7. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3181f008ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kolb DA. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sweigart LI, Umoren RA, Scott PJ, et al. Virtual TeamSTEPPS(®) Simulations Produce Teamwork Attitude Changes Among Health Professions Students. J Nurs Educ 2016;55:31–5. 10.3928/01484834-20151214-08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caylor S, Aebersold M, Lapham J, et al. The use of virtual simulation and a modified teamSTEPPS™ training for multiprofessional education. Clin Simulat Nurs 2015;11:163–71. 10.1016/j.ecns.2014.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Foronda CL, Swoboda SM, Hudson KW, et al. Evaluation of vSIM for Nursing™: a trial of innovation. Clin Simulat Nurs 2016;12:128–31. 10.1016/j.ecns.2015.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . TeamSTEPPS learning benchmarks. Available: https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/reference/learnbench.html [Accessed 8 Jul 2019].

- 18. TeamSTEPPS teamwork attitudes questionnaire. Available: https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/reference/teamattitude.html [Accessed 22 Apr 2020].

- 19. Baker DP, Amodeo AM, Krokos KJ, et al. Assessing teamwork attitudes in healthcare: development of the TeamSTEPPS teamwork attitudes questionnaire. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:e49. 10.1136/qshc.2009.036129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. TeamSTEPPS . Strategies and tools to enhance performance and patient safety. Available: https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/index.html [Accessed 22 Apr 2020].

- 21. Roy V, Collins LG, Sokas CM, et al. Student reflections on interprofessional education: moving from concepts to collaboration. J Allied Health 2016;45:109–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zechariah S, Ansa BE, Johnson SW, et al. Interprofessional education and collaboration in healthcare: an exploratory study of the perspectives of medical students in the United States. Healthcare 2019;7:117. 10.3390/healthcare7040117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jernigan S, Magee C, Graham E, et al. Student outcomes associated with an interprofessional program incorporating TeamSTEPPS®. J Allied Health 2016;45:101–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Draycott TJ, Crofts JF, Ash JP, et al. Improving neonatal outcome through practical shoulder dystocia training. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:14–20. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817bbc61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barsuk JH, Cohen ER, Feinglass J, et al. Use of simulation-based education to reduce catheter-related bloodstream infections. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1420–3. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McGaghie WC, Draycott TJ, Dunn WF, et al. Evaluating the impact of simulation on translational patient outcomes. Simul Healthc 2011;6 Suppl:S42–7. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e318222fde9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zendejas B, Brydges R, Wang AT, et al. Patient outcomes in simulation-based medical education: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:1078–89. 10.1007/s11606-012-2264-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Griswold-Theodorson S, Ponnuru S, Dong C, et al. Beyond the simulation laboratory: a realist synthesis review of clinical outcomes of simulation-based mastery learning. Acad Med 2015;90:1553–60. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cox T, Seymour N, Stefanidis D. Moving the needle: simulation's impact on patient outcomes. Surg Clin North Am 2015;95:827–38. 10.1016/j.suc.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Capella J, Smith S, Philp A, et al. Teamwork training improves the clinical care of trauma patients. J Surg Educ 2010;67:439–43. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Riley W, Davis S, Miller K, et al. Didactic and simulation nontechnical skills team training to improve perinatal patient outcomes in a community hospital. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2011;37:357–64. 10.1016/S1553-7250(11)37046-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ohta K, Kurosawa H, Shiima Y, et al. The effectiveness of remote facilitation in simulation-based pediatric resuscitation training for medical students. Pediatr Emerg Care 2017;33:564–9. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified participant data is not available for sharing outside of our institution.