Abstract

Takayasu's arteritis is an autoimmune inflammatory disease of large arteries. We report a case of postcardiac surgery pseudoaneurysm. Anesthetic concerns, high risk related to surgery, necessary anesthetic preparations, and considerations will be mentioned here.

Keywords: Aortic pseudoaneurysm, cardiopulmonary bypass, deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, Takayasu's arteritis

INTRODUCTION

Aortic root pseudoaneurysm is a rare complication after aortic surgery (0.5%). Anesthesiologist's key role is to perform a good perioperative assessment, applying proper intraoperative monitoring, preparation of inotropes, and adequate blood and blood products.

CASE REPORT

We report this rare pseudoaneurysm operation which was performed in our center. This is a case report of a 36-year-old female patient who has the following medical history:

The patient had the following previous surgeries: aortic valve replacement, coronary artery superior vena cava (SVC) to right coronary artery, and left anterior descending (LAD) dilatation. As well as, modified Bentall procedure for ascending aorta and aortic root aneurysm was done. Then, mitral valve replacement and permanent pacemaker were done. The patient had acute decompensated heart failure with low ejection fraction and LAD intervention was performed. The patient was stable until recently, as she complained of palpitation

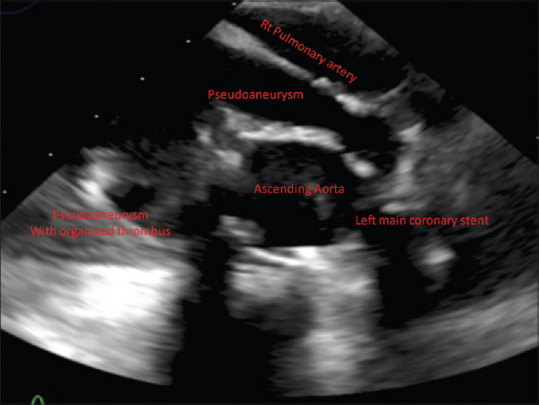

Echocardiography showed an echolucent mass extending anterior to the ascending aortic graft, no flow was visualized in the transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), and this mass is extending inferiorly into the right atrium with mass effect [Figure 1]

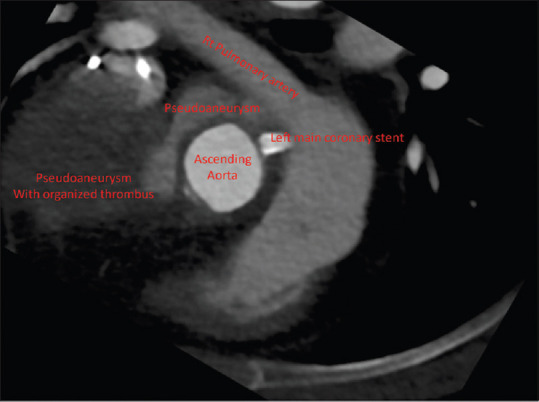

Computed tomography (CT) coronary angiography showed large pseudoaneurysm arising from the aortic root which is partially thrombosed, encircling the aorta with mass effect on SVC, and occupying the right anterior mediastinum [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Transesophageal echocardiogram upper esophageal short-axis view at the level of coronary artery showing pseudoaneurysm with organized thrombus

Figure 2.

Computerized tomography angiogram. The image was rotated to match the view seen on transesophageal echocardiogram

Planned surgery

Resection of the pseudoaneurysm, possibility of ascending aortic replacement or Bentall procedure.

The patient was informed about the high-anesthetic risk related to the procedure.

In preparation for surgery 10 units of packed red blood cell (RBC), 10 units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP), 10 units of platelets, and 10 units of cryoprecipitates were arranged. Blood bank has been informed about the risk of excessive bleeding; further blood and blood products might be required.

Pre induction, radial arterial line and big-bore peripheral line were inserted. Anesthetic induction was done with etomidate, fentanyl, and muscle relaxation with rocuronium.

Right internal jugular vein was cannulated, then second big-bore peripheral line and femoral arterial line were inserted. As pulmonary artery pressure was not expected to be high, a pulmonary artery catheter was not inserted.

Aorta was very much adherent to the posterior surface of the sternum. Therefore, there was an increased risk of injuring the aorta during sternotomy, which may lead to fatal bleeding. Femoral artery and femoral vein were cannulated, then Femoro-Femoral CPB=Femoro-Femoral Cardio Pulmonary Bypass has been started.

The patient was cooled to bring the core temperature to 18°C. As a result, deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) was started before opening the aorta.

A new aortic graft was reconstituted with end-to-end anastomosis. On rewarming, 2 units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) were given, and inotropes have been started (epinephrine and norepinephrine) both. As the patient's temperature reached 36°C, the patient was weaned off CPB.

Due to excessive bleeding (about 2000 ml) after separation from CPB, a cell saver was started, and transfusion of 8 units of packed RBCs, 10 units of fresh frozen plasma, 6 units of cryoprecipitates, and 15 units of platelets was performed. In addition, 90 units/kg of recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) were given. After surgery, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit intubated with stable hemodynamics and mild chest drain output.

On the 1st postoperative day due to bleeding from the chest (blood loss 500 ml), chest exploration was done.

The patient was hemodynamically stable and extubated on the 2nd postoperative day. She was transferred to the stepdown unit on 6th postoperative day and discharged home in a very good condition on the 22nd postoperative day.

DISCUSSION

Risk factors for developing pseudoaneurysms after cardiac surgery

Risk factors for developing pseudoaneurysms after cardiac surgery are mediastinitis, aortic graft infection, and progressive aortic wall disease (such as Marfan syndrome and Takayasu's arteritis), which is an autoimmune disease leading to inflammation of the arterial walls, mainly aorta, and large arteries.

Presenting symptoms of pseudoaneurysm can be

Presenting symptoms of pseudoaneurysm can be chest pain, heart failure, SVC syndrome, and signs and symptoms of compression of the trachea or surrounding organs, and anemia.

Surgical plan for sternotomy depends on the distance between the aneurysm and sternum. If this distance is <2 cm, then CPB should be started before sternotomy. However, if the distance is more than 2 cm, also in the posterior position of pseudoaneurysm, sternotomy can be done safely.[1]

Another etiology of developing ascending aortic pseudoaneurysm is trauma on the chest.[2]

Specific anesthetic considerations in this case

Since this is a reoperation on the heart (two previous cardiac surgeries), there were several issues to be taken into consideration for this patient:

Possibility of sudden massive bleeding due to adhesions of pseudoaneurysm to the sternum

Direct injury to the heart, aorta, lung, or any other vital organ during opening the chest

Expected increased cardiopulmonary bypass time due to the nature of surgery. Consequently, increased blood and blood products requirements after CPB

Possibility of undergoing DHCA. DHCA is known to induce coagulopathy due to the destruction of clotting factors and platelets.

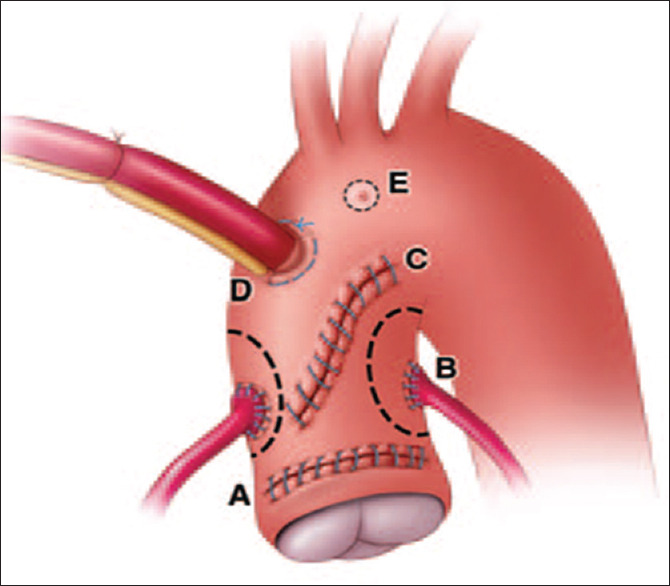

False aneurysms have the general tendency to grow irrespective of their location, and this will always end in rupture. Figure 3 shows the most common locations of postoperative aortic pseudoaneurysms.[3]

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram shows common locations for postoperative aortic root pseudoaneurysms. A: Graft anastomosis site, B: Coronary artery, anastomosis site, C: Aortotomy site, D: Aortic cannulation site, E: Needle vent site. (Reprint with permission from Fishman et al.[3]

In a retrospective study of Malvindi et al., 43 patients with postcardiac surgery pseudoaneurysm were included. In this study, about 50% of the patients were detected through routine yearly postoperative CT even without symptoms. Inhospital mortality was 6.9% (3 patients), and the postoperative course was complicated in 17 cases (39%). Survival rates at 1, 5, and 10 years were 94%, 79%, and 68%, respectively.[4]

In the retrospective study of Atik et al., they reported about 60 patients who underwent repair of aortic pseudoaneurysm over 12 years, and 83% of them underwent previous cardiac surgery. Pseudoaneurysm was located in the ascending aorta in 70% of cases.

Etiologies were:

Graft infection in ascending aorta pseudoaneurysm

Trauma in descending aorta pseudoaneurysm.

Hospital mortality was 6.7% (n = 4). Re-exploration for bleeding was required in 8.3%, and 3.3% had a postoperative stroke. At 30 days, 5 years, and 10 years, survival was 94%, 74%, and 60%, and freedom from reoperation was 95%, 77%, and 67%, respectively.[5]

In a case reported by Ingoglia et al., the patient had repeatedly unexplained chest pain, in addition to chills and low-grade fever.

Ascending aortic pseudoaneurysm happened as a complication to pericarditis (methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus) and repeated pericardial surgeries. Ascending aortic root pseudoaneurysm can happen as an early complication, or maybe seen as late as 20 years or more after the original surgery.

It was recommended that chest CT, magnetic resonance imaging, aortography, and transesophageal echocardiogram are very reliable in detecting aortic pseudoaneurysm, unlike the trans thoracic echocardiography (TTE).[6]

CONCLUSION

Aortic pseudoaneurysm is a rare complication after cardiac surgery.

Successful results depend on good planning, skillful anesthetic, surgical, and cardiology management.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient (s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initial s will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Settepani F, Muretti M, Barbone A, Citterio E, Eusebio A, Ornaghi D, et al. Reoperation for aortic false aneurysms: Our experience and strategy for safe resternotomy. J Card Surg. 2008;23:216–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2008.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsatli RA, Samarkandi AH, Al-Boukai AA, Zahraa JN. Traumatic aortic pseudoaneurysm. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2004;17:1143–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu LC, Cameron DE, Johnson PT, Fishman EK. MDCT evaluation of postoperative aortic root pseudoaneurysms: Imaging pearls and pitfalls. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:W84–90. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malvindi PG, van Putte BP, Heijmen RH, Schepens MA, Morshuis WJ. Reoperations for aortic false aneurysms after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:1437–43. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.06.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atik FA, Navia JL, Svensson LG, Vega PR, Feng J, Brizzio ME, et al. Surgical treatment of pseudoaneurysm of the thoracic aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:379–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ingoglia M, Pani S, Britton L, Hanakova M, Raja A, El-Mohtar K, et al. Ascending aortic pseudoaneurysm. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2011;25:1098–100. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]