Abstract

Background

The need for healthcare workers (HCWs) to have skills and knowledge in non-cancer palliative care has been recognised. Simulation is increasingly being used for palliative care training, offering participants the opportunity to learn in a realistic environment and fully interactive way.

Objective

The aim of this systematic review was to summarise and critically appraise controlled studies on simulation training in non-cancer palliative care for HCWs.

Selection

Medline, CINAHL, PubMed and Cochrane Library databases were searched using palliative care and simulation terms. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomised RCTs and controlled before-and-after (CBA) studies were included. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts and undertook full article review using predefined selection criteria. Studies that met the inclusion criteria had data extracted and risk of bias assessed using the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care risk of bias criteria.

Findings

Five articles were included: three RCTs and two CBA studies. All studies assessed learners’ palliative care communication skills, most studies evaluated learners’ perception of change in skills and one study assessed impact on patient outcomes and learners’ change in behaviour when applied in practice. There was variation in intervention content, intensity and duration, outcome measures and study design, making it difficult to compare and synthesise results.

Conclusion

There is a paucity of evidence to support simulation training to improve non-cancer palliative care. This review highlights the need for more robust research, including multicentre studies that use standardised outcome measures to assess clinician skills, changes in clinical practice and patient-related outcomes.

Keywords: Literature Review, Simulation Training

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care is an approach that focuses on optimising the quality of life for a person (and their families) with a progressive, life-limiting illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering. 1 Three trajectories of chronic progressive illness have been described: cancer, chronic organ failure, and frail elderly or dementia. 2 Unlike cancer, which entails a fairly predictable ‘short period of evident decline’ in physical health, the trajectories of chronic organ failure, frailty and dementia can be variable and often unpredictable. The unpredictable nature of non-cancer conditions can make prognostication and timely recognition of dying challenging. This can impact on initiation of palliative care and the quality of palliative care for patients with non-cancer conditions, which several studies have reported to be lower than the quality for cancer patients. 3 4

These issues highlight the need for healthcare workers (HCWs) to understand the different illness trajectories and to have the skills to recognise when a palliative care approach is needed for patients with non-cancer conditions, to ensure timely and appropriate care and support is provided. 5 Further, with the ageing population and growing demand on palliative care services, a model in which all HCWs are trained in basic palliative care skills has been recommended. 6 One type of educational method—simulation—offers unique educational opportunities for experiential learning with no risk to patients. 7 Simulation is an immersive technique that allows learners to participate in realistic tasks and experiences in authentic settings. 8 It is being increasingly used for healthcare education and training, across multiple disciplines, and in many clinical areas but is relatively new within palliative care.

Meta-analyses studies have shown technology-enhanced simulation training to have large effects on learner knowledge, skills and behaviour, and to have small-to-moderate effects on patient outcomes, in particular in surgical or procedural specialities, compared to no training. 9 10 Similarly, simulation using virtual reality technology has been shown to improve learner knowledge and skills compared to traditional education or online and offline digital education. 11 Although these results are promising, none of the studies included in these meta-analyses covered the clinical topic of palliative care.

To our knowledge, there has not been a systematic review addressing the efficacy of simulation-based training on non-cancer palliative care for HCWs that focusses on improving learner knowledge, skills, behaviour or patient outcomes. The aim of this systematic review was to critically evaluate the controlled studies on simulation-based palliative care training for HCWs providing palliative and end-of-life (EOL) care to patients with progressive life-limiting illnesses other than cancer and to assess the impact on learners’ knowledge and skills, and patient outcomes such as healthcare use, and satisfaction with care.

METHODS

This review was planned, conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). 12

Eligibility criteria for this review

Types of studies

The review considered randomised controlled trial (RCT), controlled before-and-after (CBA) and non-randomised controlled trial study designs for inclusion. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) study design definitions were used as a reference. 13

Types of participants (targeted learners)

Studies with participants that included HCWs who provided EOL or palliative care were considered for inclusion. This included qualified medical, nursing, allied health professionals and care attendants, who work in healthcare settings such as hospitals, residential care (nursing home and long-term care) and hospice care. Studies aimed at undergraduate student training only, such as nursing or medical students, were excluded. Where studies included both undergraduate students and HCWs, these were included if the results from each group were reported or could be derived separately.

Types of patients

Studies where the training was about providing palliative care for adult patients with a chronic, progressive life-limiting illness or end-stage disease other than cancer, such as advanced heart disease, chronic lung disease or advanced dementia, were included.

Types of interventions

In this systematic review, all forms of simulation methodologies as described by Gaba (2004) 8 were included: use of verbal role-play, simulated (standardised) patient (actor), part-task trainer, computer patient and electronic patient (manikin-based or virtual reality simulator).

Studies were included if the intervention was simulation-based non-cancer palliative care training or the training included a component of simulation, and; interventions where the palliative or EOL care training topics included knowledge and skill development in: a palliative care approach, recognising when a patient is approaching EOL, the needs of patients and their families as they approach EOL, including symptom assessment and management such as pain, breathlessness, and terminal delirium, and how to have EOL conversations with patients and their families.

Studies were excluded where the training solely involved one of do-not-resuscitate orders, limitation on medical treatment, advance care planning or withdrawal of treatment decision-making.

Types of controls or comparators

Comparators included no training, access to standard or usual training opportunities, or an alternative training intervention without simulation.

Types of outcomes

-

Learner (HCWs) outcomes.

Knowledge and skills in palliative or EOL care—objectively assessed or self-reported.

Perceived or reported self-efficacy and confidence in providing palliative or EOL care.

Behaviour in healthcare or clinical setting.

-

Patient outcomes:

Healthcare use—such as transfers to hospital, hospital admissions, hospital length of stay and outpatient care.

Place of death.

Quality of EOL care.

Patient and/or carer satisfaction with care.

Article characteristics

Articles were included if they were published in English and reported original work. Commentary or editorial pieces, discussion papers and methodology articles were excluded. There was no limitation set for year of publication.

Information sources

Medline Ovid, PubMed, CINAHL EBSCO and Cochrane library databases were searched. Searches were conducted in March and April 2018, and an update of the search was conducted in April 2019.

Search strategy

The search strategy was broad and included palliative care terms (such as palliative, palliative care, terminal care and end-of-life care) in combination with simulation terms (such as simulation education, patient simulation and standard patient). Boolean operators (OR and AND) were used to combine search terms. An outline of the Ovid Medline search strategy is provided in box 1. In addition, (1) the reference lists and citations of included articles and identified systematic reviews were searched for potentially relevant articles and (2) a Title Abstract Keyword search for simulation and palliative was performed for Cochrane reviews in the Cochrane Library.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review (n=5)

| Author, year | Methods | Participants | Intervention | Outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study type | Study period | Country | Location/setting | Participants and sample size | Programme name, clinical topic & simulation technology | Structure and content of training | Control | Primary outcome and main findings | Secondary outcome/s | KLL | |

| Bodine JL, 2017 | CBA | Not stated | USA | ED: 70-bed ED at a level I trauma centre in central California | 53 ED nurses; 25 intervention and 28 control group; 79% female, 6.2 years mean ED experience. Convenience sample, non-randomised. |

End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC). EOL care in ED for patients with terminal chronic illness. Simulated family member and clinician portrayed by ED resident with scripted roles, and a high-fidelity patient.

|

Didactic lectures/presentations 1 of 2 Simulations Debriefing: facilitated debriefing Feedback: no Facilitator: not listed Simulation scenario—dying homeless man Duration (total): 24 hours 3× 8-hour sessions |

Lecture only course consisted of same 6 module presentations case study discussion and video clips | Knowledge of EOL care (abbreviated ELNEC Knowledge Assessment Test). No between-group difference in mean scores from baseline to post-intervention. |

N/A | 2 |

| Brown CE, 2018 | RCT | 2007–2012 | USA | University of Washington and Medical University of South Carolina |

472 participants, 232 intervention and 240 controls stratified by study site, discipline (nurse or medical) and year of training. Internal medicine residents, medical fellows, nurse practitioner trainees, community-based advanced practice nurses. 248 completed both baseline and follow-up questionnaires; 59% female and mean age 30.6 years. |

Codetalk: Simulation-based Palliative Care Communication Skill. Adapted from Oncotalk. Palliative care and EOL care for patients with life threatening or chronic illness. Simulated patients, family members and clinicians portrayed by actors.

|

Didactic lectures/presentations 2 Simulations Debriefing: reflective discussions Feedback: no Facilitator: trained facilitators—nurse educator and physician Simulation scenario—2 patient stories from diagnosis to death Duration (total): 32 hours 8× 4-hour sessions |

No intervention | Self-assessed competence in palliative care communication skills (questionnaire developed for the study). The intervention was associated with an improvement in self-assessed competence in communication skills compared to the control group (p<0.001). |

N/A | 2 |

| Curtis JR, 2013 | RCT | 2007–2013 | USA | University of Washington and Medical University of South Carolina |

391 internal medicine and 81 nurse practitioner trainees, 232 intervention and 240 controls; 58% female. | Codetalk: Simulation-based Palliative Care Communication Skill. Adapted from Oncotalk. Palliative care and EOL care for patients with life threatening or chronic illness. Simulated patients, family members and clinicians portrayed by actors.

|

Didactic lectures/presentations 2 Simulations Debriefing: reflective discussions Feedback: no Facilitator: trained facilitators—nurse educator and physician Simulation scenario—2 patient stories from diagnosis to death Duration (total): 32 hours 8× 4-hour sessions |

No intervention | Patient-reported quality of communication (QOC). The intervention was not associated with changes in QOC or quality of EOL care for patients (p=0.15; p=0.34) or families (p=0.81; p=0.88). |

Patient-reported quality of EOL care and depressive symptoms (Personal Health Questionnaire); family reported QOC and quality of EOL care. Clinician evaluators rated trainees’ quality of EOL care |

3 & 4 |

| Pekmezaris R, 2011 | CBA | Not stated | USA | Northeastern metropolitan area of New York State | 150 physicians in training (residents), mainly postgraduate year 1: 77 intervention and 73 controls; 50% female | An intensive training programme on ACP, MOLST, delivery of bad news and communication near the EOL. EOL care for older patients. Simulated patients portrayed by an actor.

|

Didactic lectures/presentations Online modules 1–3 Simulations Debriefing: no Feedback: feedback given by moderator/facilitator; reflection during timeouts on possible ways to proceed Facilitator: moderator—communication expert Simulation scenario—details not provided Duration (total): 12 hours 6× 2-hour sessions |

No intervention | Self-rated competence with EOL care using the Abbreviated Palliative Medicine Comfort and Confidence survey. Results are presented based on baseline scores. There were no between-group differences in difference in mean scores for 3 of the 4 stratifications. |

Attitudes toward Death Survey | 2 |

| Szmuilowicz MD, 2010 | RCT | Fall 2006 to Spring 2007 | USA | Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston | 49 internal medicine residents, mainly postgraduate year 2; 23 intervention and 26 controls. | Skills building retreat, in which breaking bad news and discussing direction of care created the framework for the scenarios. EOL care for patients with life-threatening illness Simulated patient (no further details provided).

|

Didactic lectures/presentations Small group discussion 4 Simulations—each learner participated in at least one Debriefing: group debrief with review of key concepts Feedback—feedback given after individual practice by facilitator Facilitators: trained member from Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care Simulation scenario—details not provided Duration (total): 5 hours over 1 day |

No intervention | Communication competence in carrying out EOL conversations assessment of recoded conversations with simulated patient. After training, the intervention group had significantly higher scores for skills in breaking bad news compared to the control group (p=0.046), but no differences for other communication competence items. |

Responses to emotional cues; self-assessed confidence; participant satisfaction |

1 & 2 |

ACP, advance care plan/directive; CBA, controlled before-and-after study; ED, emergency department; ELNEC, End of life Nursing Education Consortium; EOL, end of life; GOC, goals of care; KLL, Kirkpatrick’s levels of learning evaluation; MOLST, Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment; N/A, not applicable; QOC, quality of care; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Study selection

After search results were merged and duplicates discarded, two reviewers (JT, RB) independently screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved articles to identify potential studies based on the above eligibility criteria, except for study design which was assessed in the full article review. In the event of insufficient information in the abstract, the full text of potential articles was reviewed. The two reviewers then met to compare results. Articles were excluded if they were classified by both review authors as ‘exclude’. Where the reviewers had varied results, disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Following title and abstract review, potential articles then underwent full article review to ensure they met the criteria for inclusion independently by the two reviewers. Both reviewers met again and compared results using the same method described above.

Data extraction

Eligible articles were then reviewed for data collection and analysis. A data extraction document and spreadsheet were developed. The data extracted for each study included details about the study methods, a description of the participants (learners) and sample size, clinical topic or patient group, study design, interventions, control, outcomes and key findings relevant to the systematic review question. Data was entered onto an excel spreadsheet.

Risk of bias assessment

The ‘Suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews’ was used to guide the assessment of risk of bias in included studies. 13 Robustness of findings was assessed by reviewing the difference in the assumptions in study designs and the observed effect sizes of the primary outcome or outcomes for each of the included studies.

Data synthesis

Statistical pooling of quantitative findings for meta-analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of interventions, methods and outcomes used. The findings, therefore, have been summarised and presented in narrative form.

For each study, Kirkpatrick’s levels of learning evaluation (box 2) have been presented 14 , and Gaba’s (2004) dimensions of simulation applications (box 3) have been used as a guide to summarise the included studies. 8

Table 2.

Included articles by Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care( risk of bias criteria

| Author (year) | Study design | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Baseline outcome measurements similar | Baseline characteristics similar | Incomplete outcome data | Knowledge of allocated interventions prevented | Protection against contamination | Selective outcome reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bodine, JL(2017) | CBA | High risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Brown, CE (2018) | RCT | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Curtis, JR (2013) | RCT | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Pekmezaris, R (2011) | CBA | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Szmuilowicz, MD (2010) | RCT | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

CBA, controlled before-and-after study; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Box 1 Strategy used for MEDLINE database search.

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to Present>. Search Strategy:-------------------

Palliative care.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

Terminal care.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

End-of-life care.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

Hospice care.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

Terminally ill.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 (84 920).

Simulat*.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

Virtual.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

Patient simulation.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

Standard patient.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

Simulation education.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

Simulation training.mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12.

6 and 13

Box 2 Kirkpatrick’s 4 levels of learning evaluation 14 .

Level 1—Reaction: measures how those who participate in the training react to it (satisfaction and feedback).

Level 2—Learning: measures participants’ change in attitudes, improves knowledge and/or increases skills as a result of the training.

Level 3—Behaviour: the extent to which change in behaviour in the workplace/clinical setting has occurred as a result of participating in training.

Level 4—Results: did results occur because participants attended the training. Includes improved quality, benefits to patients, improved clinical outcomes and cost benefits.

Box 3 Gaba’s dimensions of simulation applications 8 .

The purpose and aims of the simulation activity

The unit of participation in the simulation

The experience level of the simulation participants (details will be provided under participants)

The healthcare domain in which the simulation is applied

The healthcare discipline of personnel participating in the simulation

The type of knowledge, skill, attitudes or behaviour addressed in simulation

The age of the patient being simulated

The technology applicable or required for simulations

The site of simulation participation

The extent of direct participation in simulation

The feedback method accompanying simulation

RESULTS

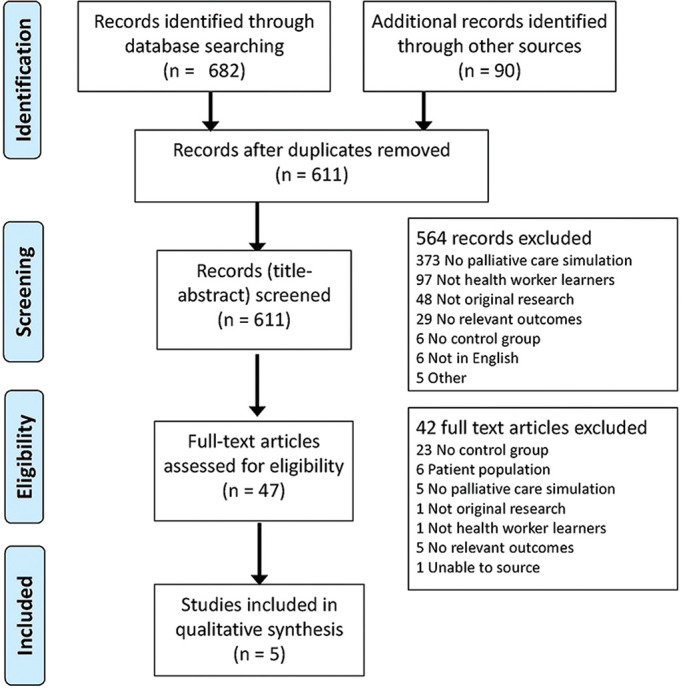

Study selection

Figure 1 summarises the study selection process. The initial search identified 611 articles. Following title-abstract review, 47 articles went on to have full-text review. Forty-two of these articles did not meet the inclusion criteria, the main reason being the lack of an included control group. The remaining five studies, three RCTs 15–17 and two CBA studies, 18 19 were included. The articles by Brown et al (2018) and Curtis et al (2013) are related to the same study but were both included as they reported on different outcomes.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the five included studies have been summarised in table 1. All studies were published between 2010 and 2018 and conducted in the USA.

The purpose and aims of the simulation activity were to improve the education, knowledge and basic skills in palliative and EOL care, and training in tasks and work to be performed, such as communication skills training of the learners (Gaba dimensions 1 and 6). All studies addressed technical skills and conceptual understanding during simulation. The simulation training in four studies focused on developing communication skills, including breaking bad news and discussing directions or goals of care. 15–17 19 The simulation training in the study by Bodine et al (2017) aimed to develop pain and symptom management skills in addition to communication techniques. 18

The unit of participation was the individual HCW (Gaba dimension 2) in all studies. Participants (Gaba dimensions 3 and 5) varied across studies and included internal medicine fellows and residents, nurse practitioner trainees, registered nurses and emergency department (ED) nurses.

The healthcare domain or setting (Gaba dimension 4) for which simulation was applied was in-hospital ward-based care for four studies 15–17 19 and the ED for one study. 18 All studies involved simulations with adult patients, one of which portrayed an older person 19 and three included simulations of family members (Gaba dimension 7).

Details of the simulation scenario were not provided in two of the articles. The study by Bodine and colleagues (2017) used a simulation scenario of a dying homeless man, and Curtis et al (2013) and Brown et al (2018) included scenarios of two patients with a life-threatening chronic disease. In addition, there was variation in duration of the training, ranging from 5 hours run over 1 day to 42 hours run as eight 4-hour sessions.

Participants were involved in hands-on participation in simulation (Gaba dimension 10) and used a feedback method accompanying the simulation (Gaba dimension 11) in all studies. Four studies included real-time critique in the form of postsimulation feedback by coparticipants and/or facilitators, 15–17 19 and one study used in-depth debriefing. 18

The technology applicable or required for simulations varied (Gaba dimension 8). Simulated patients and family were portrayed by actors in four studies, and Bodine et al (2017) used a high-fidelity patient (mannequin) and medical residents with scripted roles to portray simulated family members. The site of simulation participation (Gaba dimension 9) has been summarised in table 1 under location and setting.

Reaction (Kirkpatrick’s level 1)

One RCT assessed participants’ reaction to the training programme using a participant satisfaction survey. The authors reported the training was well-received and participants overwhelmingly agreed that the training was helpful and endorsed the idea of making the training mandatory; however, further details were not provided.

Learning (Kirkpatrick’s level 2)

Four of the included studies evaluated participants’ acquisition in palliative and EOL care knowledge, skills or change in attitudes. 16–19 One low-quality CBA study assessed learners’ knowledge acquisition and found no effect on participants’ knowledge of EOL care, 18 and another low-quality CBA study reported improved attitudinal change towards death and comfort. 19 Both these studies had substantial methodological limitations and were the only studies to assess change in participants’ knowledge or attitudes making it difficult to draw any conclusions.

Three studies reported on communication skills acquisition with mixed results. 16 17 19 In their RCT of moderate-quality, Brown et al reported those who participated in the palliative care simulation training showed improvement in self-assessed competence in communication compared to the control group, 17 whereas the CBA study by Pekmezaris et al reported no between-group differences in self-rated competence with EOL care, including confidence in EOL communication. 19

Further, one moderate-quality RCT found participants in the intervention group had improvements in communication scores for breaking bad news but no differences in communication scores related to the direction of care or overall responding to emotion score relative to the control group. 16 This was the only study to use trained evaluators to objectively assess participants’ communication skills, the aforementioned studies used self-report which has been shown to inflate improvement. 20 Therefore, there is inconclusive evidence to show that simulation-based training improves acquisition of communication skills for HCWs working in non-cancer palliative care.

Behaviour (Kirkpatrick’s level 3)

One moderate-quality RCT assessed learners’ change in behaviour, with clinician-evaluators rating trainees’ quality of communication and quality of care in the clinical setting. 15 Clinician-evaluators used a validated questionnaire to measure quality of clinician (trainee) skill at providing EOL care in the clinical setting but were unable to demonstrate a positive change. These findings were consistent with the family-rated and patient-rated measures of clinician quality of communication suggesting that skills learnt in the training are not being transferred into practice. A further explanation could be due to the clinician-based evaluations occurring in the 10 months following the training and the skills not being sustained over this length of time.

Patient and clinical outcomes (Kirkpatrick’s level 4)

This same RCT assessed patient and family outcomes, using validated questionnaires to measure quality of communication (primary outcome), quality of EOL care, patient depressive symptoms and functional status. 15 They reported no association between the intervention and patient-rated or family-rated quality of communication scores, quality of EOL care scores or functional status scores. However, they found that the intervention was associated with increased depression scores among patients of intervention group trainees with a mean score of 10.0 compared to patients of control group trainees mean score of 8.8 (adjusted effect=2.2, p=0.006). The authors suggest that these findings may be a result of the intervention itself where the patient has greater awareness of their prognosis and this triggers negative experiences, but this requires further investigation. A further explanation is that the study may have lacked the power to measure this change. Although numbers of trainees included in the randomisation met the sample size calculation, 68% of intervention trainees and 52% of control trainees were not included in the final analysis of the patient evaluations, leading to risk of attrition bias. This could potentially have influenced the statistical power of the study and balance of confounders between the groups.

Risk of bias assessment (table 2 )

The RCTs were assessed as low to moderate risk of bias, and the two CBA studies were assessed as moderate to high risk of bias. All three RCTs reported use of random allocation of participants, described the random sequence generation methods used and were single-blinded with outcome assessors but participants were not blinded to group assignment. None of the RCTs reported allocation concealment methods. All studies had unclear risk or high risk of bias for one or more criteria.

The CBA studies by Bodine et al (2017) and Pekmezaris et al (2011) were assessed as high risk of bias due to the non-randomised study design, lack of power analysis and lack of detail of statistical analyses of baseline characteristics, baseline outcome measures and between-group results.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

This systematic review highlights the limited evidence base to support the use of simulation in palliative care training for HCWs in non-cancer care. Five studies were identified and included in the review. All studies had training interventions with the primary aim of improving HCW palliative and EOL care communication skills; however, the studies were heterogeneous in terms of the intensity of the training, the type of simulation used in the training and their outcome measurements, making it difficult to synthesise the results.

Communicating well with patients and families is key to providing quality palliative care, and all studies included communication skills development as part of the training, with the aim of improving communication between the HCW and the patient. The three studies that reported on communication skills acquisition used different methods to measure this outcome, and results varied across the studies with one study showing benefits, one showing no difference and one showing mixed results depending on the communication skill being assessed. Further, one moderate-quality RCT assessed EOL communication skills in the clinical setting and from the perspective of the patient and family; however, they were unable to demonstrate any positive findings. The small number of studies, variation in outcome measures used and mixed results make it difficult to draw any conclusions and highlight the need for more research in this area.

Symptom management skills, in particular, excellent pain management skills are also required to provide high-quality palliative care; however, only one study included symptom management and EOL nursing care as part of the simulation intervention. They were unable to demonstrate any between-group differences in knowledge acquisition, and importantly, this review shows that research on simulation training that includes symptom management in non-cancer care is in its infancy, and more research in this area is needed.

Most of the included studies assessed at level 2 of Kirkpatrick’s levels of learning evaluation and small numbers assessed levels 1, 3 and 4. One study assessed participant reaction via a feedback survey (Kirkpatrick’s level 1) as well as learner acquisition of knowledge or skills (Kirkpatrick’s level 2), 16 three studies assessed learner acquisition of knowledge or skills only (Kirkpatrick’s level 2) 17–19 with each using a unique measure—none of which were validated. Only one study included in this review assessed change in skills applied in clinical practice (Kirkpatrick’s level 3) and patient-related outcomes (Kirkpatrick’s level 4) and were unable to demonstrate benefit. This not only highlights the need for more studies to assess transfer of knowledge and skills in the clinical setting and the impact this has on patient outcomes but also for studies assessing level 2 outcomes to use standardised and validated measures to allow for comparability.

There is limited information on the optimal content, amount or length of training required, and how best to design these interventions. Training duration and intensity varied across the studies ranging from one 5-hour session to eight 4-hour sessions or 42 hours in total. All studies used didactic lectures or presentations and simulations, but not all used debriefing, reflective discussions or feedback. Further four studies compared the intervention training to no training or usual access to training opportunities and only one study compared to a lecture-only course. This shows heterogeneity across the studies in training content, components and format. Finally, the methodological quality of the studies varied with the two CBA studies having high risk of bias and the RCTs being low to moderate in quality, some of which was due to incomplete reporting. It is likely that some of the research design issues identified in this review will be improved and future studies will have more detailed reporting following the guidelines published by Cheng et al (2016) that set out features of simulation-based educational studies. 21

Strengths and limitations of the review

Overall strengths of this review include a comprehensive search strategy with multiple databases and references of identified articles searched. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts and reviewed full articles for inclusion. PRISMA was used to guide the review and the EPOC risk of bias assessment used to assess quality of studies.

However, the review has a number of limitations, including the potential for articles to have been missed in the search and review process. This was minimised by searching multiple databases and having two reviewers assess for study eligibility. The search strategy was kept broad to include a range of simulation-based training interventions, outcomes and learner groups, which may have contributed to the heterogeneity of the included studies. Limiting studies to the clinical topic of non-cancer palliative care, only including controlled trials and excluding undergraduate healthcare students, narrowed the scope of the search and may have possibly limited the findings. Another potential limitation was the decision to include two articles from the same study. This decision was made as each article assessed and reported on different outcomes. Finally, meta-analysis was not possible due to the wide variation in training interventions and outcome measures.

CONCLUSIONS

There was weak evidence to suggest that simulation-based communication skills training improved learners’ acquisition of skills, but no evidence of transfer of skills into clinical practice or on patient outcomes. These findings highlight the need for more robust research to assess the effect of simulation training in non-cancer palliative care, including multicentre studies that use standardised outcome measures to assess HCW knowledge and skills in palliative care communication and symptom management, and the impact on clinical practice and patient-related outcomes.

Footnotes

Twitter: Debra Nestel @DebraNestel.

Contributors: JT, WKL, CAB and SKP conceived the systematic review scope. JT led the systematic review, drafted the manuscript and co-ordinated the writing of the review. JT and RB screened title and abstracts and conducted the full-text reviews for the systematic review selection criteria. All authors reviewed the draft manuscripts and contributed to editing and writing.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: SKP has acted as a consultant and/or speaker for Novartis, GI Dynamics, Roche, AstraZeneca, Guangzhou Zhongyi Pharmaceutical and Amylin Pharmaceuticals LLC. He has received grants in support of investigator and investigator-initiated clinical studies from Merck, Novo Nordisk, AstraZeneca, Hospira, Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi-Avensis and Pfizer. All other authors do not have any competing interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . WHO definition of palliative care. Available https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed 9 Aug 2019)

- 2. Lynn J, Adamson DM. Living well at the end of life: adapting health care to serious chronic illness in old age. White paper. RAND Health . 2003.

- 3. Hofstede JM, Raijmakers NJ, van der Hoek LS, et al. Differences in palliative care quality between patients with cancer, patients with organ failure and frail patients: a study based on measurements with the consumer quality index palliative care for bereaved relatives. Palliat Med 2016;30:780–8. 10.1177/0269216315627123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huijberts S, Buurman BM, de Rooij SE, de Rooij SE. End-of-life care during and after an acute hospitalization in older patients with cancer, end-stage organ failure, or frailty: a sub-analysis of a prospective cohort study. Palliat Med 2016;30:75–82. 10.1177/0269216315606010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stow D, Spiers G, Matthews FE, et al. What is the evidence that people with frailty have needs for palliative care at the end of life? A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Palliat Med 2019;33:399–414. 10.1177/0269216319828650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care-creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173–5. 10.1056/NEJMp1215620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gaba DM. The future vision of simulation in health care. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:i2–10. 10.1136/qshc.2004.009878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cook DA, Hatala R, Brydges R, et al. Technology-enhanced simulation for health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2011;306:978–88. 10.1001/jama.2011.1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zendejas B, Brydges R, Wang AT, et al. Patient outcomes in simulation-based medical education: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:1078–89. 10.1007/s11606-012-2264-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kyaw BM, Saxena N, Posadzki P, et al. Virtual reality for health professions education: systematic review and meta-analysis by the digital health education collaboration. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e12959. 10.2196/12959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA). PRISMA 2009 Checklist . 2009. Available: Available http://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed 14 Nov 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) . Suggested risk of bias criteria for EPOC reviews. EPOC resources for review authors. 2017. Available https://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/Resources-for-authors2017/suggested_risk_of_bias_criteria_for_epoc_reviews.pdf (accessed 13 Aug 2019)

- 14. Kirkpatrick JD, Kirkpatrick D. Evaluating training programs: the four levels . San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Curtis JR, Back AL, Ford DW, et al. Effect of communication skills training for residents and nurse practitioners on quality of communication with patients with serious illness: a randomized trial. JAMA 2013;310:2271–81. 10.1001/jama.2013.282081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Szmuilowicz E, el-Jawahri A, Chiappetta L, et al. Improving residents’ end-of-life communication skills with a short retreat: a randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med 2010;13:439–52. 10.1089/jpm.2009.0262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brown CE, Back AL, Ford DW, et al. Self-assessment scores improve after simulation-based palliative care communication skill workshops. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018;35:45–51. 10.1177/1049909116681972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bodine JL, Miller SA. Comparison of lecture versus lecture plus simulation educational approaches for the end-of-life nursing education consortium course. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2017;19:34–40. 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pekmezaris R, Walia R, Nouryan C, et al. The impact of an end-of-life communication skills intervention on physicians-in-training. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 2011;32:152–63. 10.1080/02701960.2011.572051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dickson RP, Engelberg RA, Back AL, et al. Internal medicine trainee self-assessments of end-of-life communication skills do not predict assessments of patients, families, or clinician-evaluators. J Palliat Med 2012;15:418–26. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheng A, Kessler D, Mackinnon R, et al. Reporting guidelines for health care simulation research: extensions to the CONSORT and STROBE statements. Simul Healthc 2016;11:238–48. 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]