Abstract

Aim of the study

To assess performance in a simulated resuscitation after participating in either an interprofessional learning (IPL) or uniprofessional learning (UPL) immediate life support (ILS) training course.

Introduction

The Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM) is routinely used in Resuscitation Council (UK) Advanced Life Support courses. This study used the psychometrically validated tool to assess if the delivery of an IPL ILS to final year medical and nursing students could improve overall behavioural performance and global TEAM score.

Methods

A randomised study of medical (n=48) and nursing (n=48) students, assessing performance in a simulated resuscitation following the IPL or UPL ILS courses. Postcourse completion participants were invited back to undertake a video-recorded simulated-resuscitation scenario. Each of these were reviewed using the TEAM tool, at the time by an experienced advanced life support instructor and subsequently by a clinician, independent to the study and blinded as to which cohort they were reviewing.

Results

Inter-rater reliability was tested using a Bland-Altman plot indicating non-proportional bias between raters. Parametric testing and analysis showed statistically significant higher global overall mean TEAM scores for those who had attended the IPL ILS courses.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate that an IPL approach in ILS produced an increased effect on TEAM scores with raters recording a significantly more collaborative team performance. A postscenario questionnaire for students also found a significantly improved experience within the team following the IPL course compared with those completing UPL training. Although this study shows that team behaviour and performance can change and improve in the short-term, we acknowledge further studies are required to assess the long-term effects of IPL interventions. Additionally, through this type of study methodology, other outcomes in regard to resuscitation team performance may be measured, highlighting other potential benefit to patients, at level four of Kirkpatrick’s hierarchy.

Keywords: interprofessional learning, teamwork performance, cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Introduction

Standardised resuscitation courses, such as advanced life support (ALS) and immediate life support (ILS) are commonly used throughout the world to teach a range of healthcare providers how to recognise and treat deteriorating patients and perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).1 Higher education institutions (HEIs) delivering undergraduate healthcare curricula are committed to training professionals who are able to work as part of an effective team and in increasingly complex clinical environments, with many using a variety of simulation-based educational (SBE) activities to enhance the experience of the students and assist in their situational awareness and clinical decision making. Within the contexts of recognition and management in the deteriorating patient, it has been suggested that teamwork and leadership should form the cornerstone of good practice.2 It is therefore surprising that, despite the complex interprofessional interactions required for this to be effective, less than one-third of these educational programmes deliver an interprofessional learning (IPL) approach.3

Historically, undergraduate healthcare professionals’ education has been delivered by HEIs through a discipline-specific or uniprofessional learning (UPL) approach. This, it is now recognised, has been limited in the capability to equip new healthcare graduates with appropriate skills, knowledge and attitudes for working interprofessionally as part of a multidisciplinary team.4 5 Concurrently however, many of these same HEIs recognise the potential benefits that IPL can have, on the individuals themselves and importantly in improving healthcare delivery and patient safety.6 Nevertheless, despite the support for IPL as a key component of health professional education, some areas such as those in resuscitation, there still remains a lack of evidence as to its effectiveness.7

Recent systematic reviews of the literature reported that the majority of research undertaken with regard to IPL, predominantly focused on participants self-reporting on views, perceptions and attitudes. Furthermore, that studies designed to research Kirkpatrick’s educational outcomes at level 3 (behavioural change) did so through qualitative interviews to gain the perceptions of participants. However, there was evidence that the use of simulation technology in team training for resuscitation scenarios did produce more favourable results, especially in regard to improved process and skill development.8–10

In designing this study, it was hypothesised that by the observation and recording of participants using the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM),11 quantitative data could be collected and analysed. This would then demonstrate as to whether the intervention of an interprofessionally delivered resuscitation course could lead to any measurable change in team performance within a multidisciplinary group of medical and nursing students.

Ethical approval

This study included approval for limited disclosure to minimise any perceptual bias regarding IPL. In this way, all participants were blinded as to the study objectives regarding the effect on the team performance/interaction during a simulated resuscitation. Participants were however made aware that it was a study to evaluate the teaching of ILS to final year medical and nursing students.

Two weeks prior to the courses, students who had accepted the invitation to take part in the study were provided with an ILS manual and a participant information sheet, outlining the course and the requirements, that is, the undertaking of a recorded resuscitation scenario approximately 2 weeks after the learning.

Methods

This was a quantitative study, using the TEAM,11 a psychometrically validated tool,12 13 to explore the differences in performance, following either a uniprofessional or interprofessional ILS resuscitation course. The TEAM is routinely used in Resuscitation Council (UK) Advanced Life Support courses by instructors and candidates and although primarily designed for generic assessment of team performance in a resuscitation scenario it has also been used for self-assessment by individuals within the team.14 The assessment comprises 11 items, scoring on a 4-point scale over three domains: leadership, teamwork and task management. It also has a global overall rating, on a 10-point scale, for the team’s non-technical performance.13

Advice was sought, from the department of medical statistics at the University of Aberdeen (UoA), in regard to both the required sample size and the subsequent methods of analysis for the assessment tools being used. These would include Shapiro-Wilk test and inspection of Q-Q plots to determine normal distribution of data, along with independent-sample t-testing to identify any statistically significant differences.

Sample

Following statistical advice, it was proposed that, as the final recorded scenarios for analysis would be eight ‘teams’ of six students from both the UPL baseline (n=48 students) and IPL interventional (n=48 students) cohorts, the total required sample size would be n=96. A power analysis was performed for sample size estimation. The effect size in this study was considered medium, 0.3 using Cohen’s (1988) criteria, with an α=0.05 and a Power=0.9, the projected sample size needed with G*power 3.1 software was n=88, for this between-group comparison. Thus, our proposed sample of n=96 was more than adequate for the objectives of this study.

Final year medical students from the UoA and final year nursing students from Robert Gordon University (RGU) were invited via emails from the respective establishments, to participate in a study evaluating the teaching of ILS for final year healthcare students.

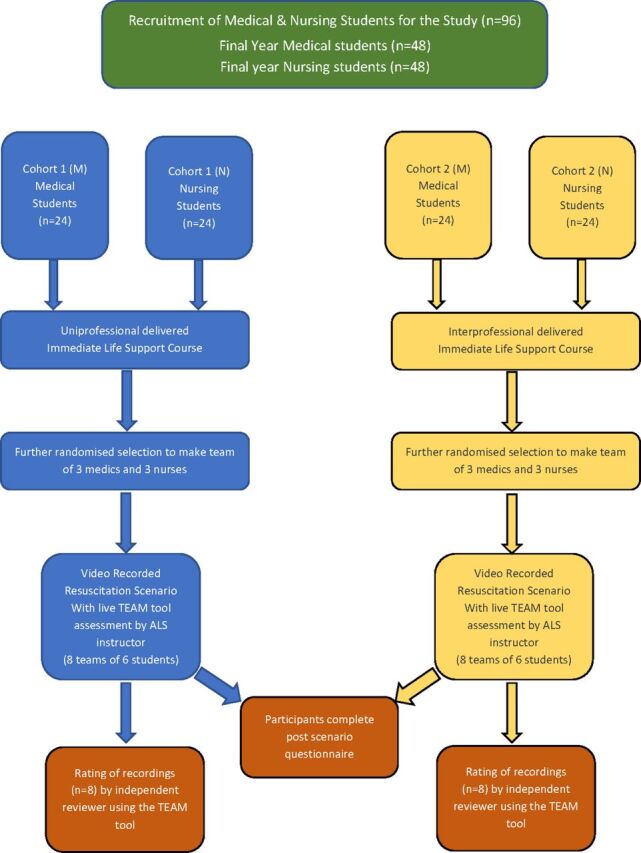

To ensure an equality of both professions in the final ‘student resuscitation teams’, comprising three nursing and three medical students, a total of 48 nursing students and 48 medical students were recruited for the study. These consenting students from each profession were subsequently block randomly selected to either the UPL courses held at both UoA and RGU, or the IPL courses held at the UoA (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Breakdown of the study participant, cohorts and design flow diagram. ALS, advanced life support; TEAM, Team Emergency Assessment Measure.

All courses were conducted in accordance with Resuscitation Council (UK) guidelines by the same ALS/ILS instructors ensuring standardisation of teaching and adhered to the standard programme. Students received two facilitated discussions with workshops, on airway management, manual defibrillation/defibrillator safety and high-quality CPR. In the final six simulated cardiac arrest scenarios, each student took it in turn to assume the role of team leader. Following each scenario, instructors held a learning conversation with the group discussing the salient points raised for both technical and non-technical skills. All students successfully passed the courses and subsequently received an ILS certificate.

Postintervention (between 2 and 3 weeks later) participants from both cohorts were allocated a time to attend the simulation suite at the UoA medical school and participate in a video-recorded resuscitation scenario. Within each of the intervention-specific cohorts (IPL/UPL), participants were further randomly assigned to form a ‘resuscitation team’ consisting of three medical and three nursing students. It was this randomisation, specifically to the UPL cohort, that provided a baseline on which to measure the study’s primary outcome, ‘the intervention of an IPL ILS course’, and met one of the previously reported study’s limitations.11

Each team of students were asked to self-allocate their roles within the ‘resuscitation team’, including the team-leader and in all but three of the 16 teams this was a medical student. To ensure consistency across all teams, the same resuscitation scenario was used and followed the same format as in the original ILS courses (a patient who deteriorates quickly into a VF cardiac arrest and the need for timely defibrillation).

During all the recorded scenarios, an experienced ALS instructor/course director, skilled in using the TEAM assessment tool, observed and completed a scoring sheet before facilitating a learning conversation with each of the ‘resuscitation teams’. At the end of each learning conversation, participants were asked to perform a self-assessment of the team in the simulated resuscitation they had just performed. To analyse the results from both observers and participants, while the ALS instructor and independent reviewer completed the full assessment tool, students were asked to complete a postscenario questionnaire using an amended TEAM tool. In this student amended self-assessment, item two (the team leader maintained a global perspective) was omitted as the focus was on the individual’s perception as how the team not the leader had performed. The text was amended into a personal tense and also included a section for free text and comments to expand and elicit, each individual’s perception, on how their team performance.

To ensure consistency in scoring of all of the groups, each of the recorded simulated resuscitations were subsequently independently reviewed by a single reviewer, experienced both as an ALS instructor/medical director and in the use of the TEAM tool. To minimise any potential bias, the reviewer was blinded as to which course each of the groups had previously received.

Data generated by the TEAM scores of both the independent reviewer and ALS instructor, along the participant’s questionnaire, were then entered into SPSS V.24 statistical software for quantitative analysis using parametric testing.

Results

As the primary aim of the study was to observe if the intervention of an IPL ILS course could lead to a change in team performance, analysis of the data focused on the global overall rating of the TEAM scores.

Data were tested for normality through the Shapiro-Wilk test with both independent reviewer (p=0.025) and ALS instructor (p=0.039) demonstrating normal distribution. Quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots were further used to assist in visualising and examination of the data (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots for independent observer and advanced life support (ALS) instructor.

Independent reviewer

Inspection of the Q-Q plots revealed that the overall TEAM scores were normally distributed for both groups and there was homogeneity of variance as assessed by Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances. An independent-samples t-test, with a 95% CI for the mean difference was conducted to compare the mean global overall TEAM performance score from the IPL and UPL teams. There was a significant difference in the scores for the IPL (M=8.38, SD=1.06) and the UPL (M=6.25, SD=2.25) teams; t(2.415)=14, p=0.03 with a mean difference of 2.125 (95% CI 0.237 to 4.013).

ALS instructor

As previously, an examination of the Q-Q plots showed that the overall TEAM scores were normally distributed and there was consistency as assessed by Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances. The independent-samples t-test conducted on the instructor’s data found further significant difference in the global overall rating TEAM scores between the IPL (M=7.875, SD=1.73) and UPL (M=5.38, SD=1.19) teams; t(2.500)=14, p=0.005 with a mean difference of 2.500 (95% CI 0.911 to 4.089).

Inter-rater reliability

To ensure inter-rater reliability, between the independent reviewer and the ALS instructor, a Bland-Altman plot was created and assessed for any non-proportional bias. This was conducted by using the mean global overall rating TEAM scores, with the difference and mean between the two scores being calculated as new variables within the data set. These were then subjected to a one sample t-test with ‘difference’ as the test variable. This yielded a mean of −0.688, an SD of 1.702 and a non-statistically significance of p=0.127 allowing for the progression to calculating the upper and lower levels of agreement based on a 95% CI. These were then inserted on to the Bland-Altman plot indicating that all 16 groups, scored by both raters, were within the range and levels of agreement (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Bland-Altman plots of independent observer and advanced life support instructor global overall mean Team Emergency Assessment Measure scores.

To further confirm the presence of a non-proportional bias, a regression analysis of the dependent variable (mean score) was performed. This showed an unstandardised coefficient of the mean (−0.060) and a non-statistically significant value (p=0.818) indicating that there was no proportional bias between the two raters.

Students

Analysis conducted by an independent-samples t-test on the mean global overall rating TEAM scores for the student teams similarly produced statistically significant results. With those undertaking the IPL courses recorded a mean of 7.85 (SD=1.73), while those undertaking the UPL courses recorded a mean of 7.00 (SD=1.09); t(3.166)=75, p=0.002 with a mean difference of 0.85 (95% CI 0.31 to 1.38).

Further analysis and inspection on the data constituting the three domains of TEAM (leadership, teamwork and task management), as well as the overall total TEAM score, further highlighted additional significant differences between the IPL and UPL cohorts (table 1).

Table 1.

Mean, SD and statistical significance of domains within the TEAM tool

| Category | Independent reviewer | ALS instructor | Student’s t-test | |||||||

| Mean | SD | P value | Mean | SD | P value | Mean | SD | P value | ||

| Leadership (total score of 8) | IPL | 6.38 | 1.51 | 0.106 | 6.38 | 1.69 | 0.001 | 3.39* | 0.67 | <0.001 |

| UPL | 4.36 | 1.31 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 2.11* | 0.80 | ||||

| Teamwork (total score of 28) | IPL | 22.50 | 4.78 | 0.266 | 25.13 | 3.27 | 0.010 | 24.74 | 2.86 | <0.001 |

| UPL | 20.00 | 3.77 | 20.50 | 2.88 | 20.58 | 2.72 | ||||

| Task management (total score of 8) | IPL | 6.75 | 1.49 | 0.119 | 6.38 | 1.51 | 0.376 | 6.38 | 1.27 | 0.010 |

| UPL | 5.25 | 2.05 | 5.88 | 0.35 | 5.66 | 1.15 | ||||

| Total TEAM score (total score of 44) | IPL | 35.63 | 7.41 | 0.150 | 38.89 | 6.77 | 0.007 | 34.62 | 4.20 | <0.001 |

| UPL | 29.63 | 8.31 | 29.88 | 3.44 | 28.32 | 4.10 | ||||

| Global overall rating of TEAM performance | IPL | 8.38 | 1.06 | 0.036 | 7.88 | 1.73 | 0.005 | 7.85 | 1.25 | 0.002 |

| UPL | 6.25 | 2.25 | 5.38 | 1.19 | 7.00 | 1.09 | ||||

*Question 1—‘The team leader maintained a global perspective?’ was omitted from the student questionnaire (total score of 4).

TEAM, Team Emergency Assessment Measure; IPL, interprofessional learning; UPL, uniprofessional learning.

Discussion

The historical approach of UPL and the inclusion of IPL in health and social care professions continues to rise both nationally and internationally. Through this ongoing modality of healthcare education, it is becoming more accepted that, when individuals from different professions learn together simultaneously, they ultimately work better together hopefully improving both service delivery and patient safety.10 Despite this, there still remains insufficient quantitative evidence to ascertain if interprofessional collaboration and learning has any effect on outcome, with further work needed to explore and improve our understanding regarding IPL interventions.9 10

The results confirmed the original hypothesis in demonstrating an educational experience through interprofessional ILS led to an observed improvement in overall collaboration. It is these observations that raise three main points for discussion.

First, the increase in global overall rating of mean TEAM scores was observed by both the independent reviewer (M=8.38, SD=1.06 vs M=6.25, SD=2.25, p=0.036) and the ALS instructor (M=7.88, SD=1.73 vs M=5.38, SD=1.19, p=0.005) indicated that the intervention of delivering an interprofessional ILS did have an effect on behaviour of the team and performance in working more collaboratively.

The ILS course used as the intervention for this study can be delivered to a wide range of health and allied healthcare professionals. Its primary outcome is that of recognition and treating the deteriorating patient and where necessary undertaking the skills of high-quality CPR and defibrillation until more advanced/experienced help is available.15 However, more recently and with an increased awareness of non-technical skills and human factors within resuscitation the course also addresses situational awareness and the participant’s evolving role as an effective team member.2 It has also been shown through the recorded observations, of both the independent observer and the ALS instructor, that those who had received the IPL ILS demonstrated a higher level of performance. Both in communication with each other throughout the simulated resuscitation, as well as working together to complete the tasks and adopting to the changing situations of the scenario.

Second, analysis of the mean scores of the three main domains (leadership, teamwork and task management) as well as the total team score, also indicated an improved rating from both the independent reviewer and the ALS instructor. Notably, statistical significance between the two was found in the scores of the ALS instructor (leadership p=0.001, teamwork p=0.010, total team score p=0.007). However, despite the IPE teams receiving a higher mean score in all categories, there were no significant differences found in the data of the independent reviewer. One possibility for this could be the loss of some of the nuances and subtle interactions, seen in the scenario by the ALS instructor in real-time, which were not as evident in the video recording reviewed by the independent observer. A concept which potentially could require further investigation as more routinely recordings of simulations and learning conversations are being used in peer review of faculty and simulation research in general.

Third, education is primarily for the students learning the experience to enhance their skills and improve their knowledge base. Many HEIs use course evaluation forms to highlight positive and negative feedback on teaching experiences from students. While predominantly designed as an objective measure of non-technical skills to assist in assessment and feedback, this study also used the TEAM to further investigate the three domains of leadership, teamwork and task management through the student’s self-assessment of their team’s performance. Analysis of the data revealed overwhelmingly that those who had experienced the interprofessional learning, had higher mean scores and statistical significance all four areas. Notably, leadership (M=3.39, SD=0.67 vs M=2.11, SD=0.80, p=0.001), teamwork (M=24.74, SD=2.86 vs M=20.58, SD=2.72, p=0.001) and total TEAM score (M=34.62, SD=4.20 vs M=28.32, SD=4.10, p=0.001), signifying that those that had undertaken the IPL courses felt more confident that they had communicated and performed better together in managing the situation than those who had undergone UPL courses.

Together these combined results from the independent observer, ALS instructor and the student’s self-assessment, suggest that undertaking IPL interventions have benefits including by learning together, separate professions, gained a clearer understanding of each other’s role. By undertaking IPL interventions, they were able to facilitate an enhanced level of communication between the team members, resulting in an improved collaborative performance.

At the onset of this study, it was hypothesised that by using IPL ILS and an independent reviewer it would be possible to see any improvement in the team’s behavioural change. What is most encouraging was that, as a secondary outcome, the students themselves, though blinded to the true purpose of the study (ie, improvement in team performance), also had a statistically significant increase in all of the domain scores. Furthermore, these findings were in-line with those observed by the trained observers, adding evidence that TEAM is an extremely versatile tool for both formal and self-assessment.

Currently, the training of ALS courses (resus council ALS) are delivered multiprofessionally with various grades of staff learning together to function as part of a team. Therefore, if it is commonplace for the more advanced level to use this IPL to enhance team performance, then this study demonstrates that providing IPL at an earlier stage of training can have a positive outcome on behavioural change at Kirkpatrick’s level 3.

Limitations to the study

The authors acknowledge that a potential limitation, as in a previous similar study,16 was the guarantee of no overlap or discussion between the participants from both groups; however, with the teams being blinded as to the assessment of ‘team performance’ in the simulations would have minimised any potential bias. Similarly, it may be perceived that these 12 teams are relatively small in number, compared with all healthcare professionals receiving ILS training and used in a full resuscitation team. However, both the team membership and number of students enrolled (n=96) are comparable with previous research, and indeed exceeds the number of participants reported in an evaluation of simulated resuscitation studies.9

The next steps

While in the participating universities it is a requirement for all final year medical students to have a valid ILS certificate on graduating, currently it is not mandated for nursing students. However, comments from the nursing participants suggest the inclusion of an ILS course in the final year of studies would provide confidence as they transition to qualified staff on the wards and as this study has shown, to do so using IPL has even more benefit.

As with any research, a positive outcome is just the start of implementing the results into practice. While there are often close links between universities in relation to IPL activities, these are primarily in the theoretical setting of classrooms and paper exercises, rather than through clinical-based IPL such as in the delivery of ILS. It is acknowledged that despite the positive findings of the study the practicalities in the delivery of IPL ILS courses to all medical and nursing students would have logistical challenges including timetabling and staffing.

Conclusions

Previous strategies to improve interprofessional collaboration between healthcare and social care professionals have demonstrated a slight improvement in an adherence to recommended practice and the use of healthcare resources. Yet, due to a lack of clear evidence, there still remains uncertainty whether the strategies employed have improved either a quality of care, continuity of care or enhanced collaborative working. The results of this study demonstrated that the intervention of using an IPL approach to resuscitation training can have an increased effect on the collaborative performance, communication and interaction within the team. Furthermore, from analysis of the data generated, the raters observed a more collaborative team performance by participants who had received the IPL intervention. The learners themselves reported an enhanced learning experience, following the IPL session compared, to those who had completed the UPL training.

As with the use of simulation in healthcare education, which we know intuitively can make a difference, the continued drive to encourage interprofessional education and measure its effect on behavioural change, remains hard to prove. This study demonstrates that, through the use of IPL and the measurement of collaborative performance using the TEAM tool, it is possible to identify that behaviour can be changed and improved. However, it is also acknowledged that further longitudinal studies are required to assess the long-term effects of the IPL intervention.

The future for using simulation to improve teamwork and eventually patient care through IPL looks increasingly promising. However, this can only be attained if those delivering the interprofessional education have strategies in place, to ensure both the longevity of IPL teaching and the available resources.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Kim Milne, Consultant Medical High Dependency Unit & Director of Medical Education, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Foresterhill, Aberdeen.

Footnotes

Contributors: JCM: participated in study design, student recruitment, simulation sessions, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and revising the manuscript and approved the final version. CWB: participated in study design, data interpretation, drafting and revising the manuscript and approved the final version. IM: participated in simulation sessions, drafting and revising the manuscript and approved the final version. CW: participated in study design, student recruitment, drafting and revising the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the School of Nursing Ethical Review Panel, Robert Gordon University and the College Ethics Review Board, College of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Aberdeen.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors are happy to share the data from the original piece of research to further the understanding and body of work surrounding interprofessional team working for the benefit of patient safety.

References

- 1. Resuscitation Council (UK). Course information. London: Resuscitation Council (UK), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Norris EM, Lockey AS. Human factors in resuscitation teaching. Resuscitation 2012;83:423–7. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Connell CJ, Endacott R, Jackman JA, et al. The effectiveness of education in the recognition and management of deteriorating patients: A systematic review. Nurse Educ Today 2016;44:133–45. 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garling PC. Final report of the Special Commission of Inquiry into Acute Care Services in NSW Public Hospitals. Sydney: State of NSW: NSW Government, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lapkin S, Levett-Jones T, Gilligan C. A systematic review of the effectiveness of interprofessional education in health professional programs. Nurse Educ Today 2013;33:90–102. 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brock D, Abu-Rish E, Chiu CR, et al. Interprofessional education in team communication: working together to improve patient safety. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:414–23. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Braithwaite J, Westbrook JI, Foxwell AR, et al. An action research protocol to strengthen system-wide inter-professional learning and practice [LP0775514]. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:144. 10.1186/1472-6963-7-144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reeves S, Fletcher S, Barr H, et al. A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME Guide No. 39. Med Teach 2016;38:656–68. 10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mundell WC, Kennedy CC, Szostek JH, et al. Simulation technology for resuscitation training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2013;84:1174–83. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reeves S, Pelone F, Harrison R, et al. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD000072. 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cooper S, Cant R, Porter J, et al. Rating medical emergency teamwork performance: development of the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM). Resuscitation 2010;81:446–52. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McKay A, Walker ST, Brett SJ, et al. Team performance in resuscitation teams: comparison and critique of two recently developed scoring tools. Resuscitation 2012;83:1478–83. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cooper SJ, Cant RP. Measuring non-technical skills of medical emergency teams: an update on the validity and reliability of the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM). Resuscitation 2014;85:31–3. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.08.276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hart PL, Brannan JD, Long JM, et al. Effectiveness of a structured curriculum focused on recognition and response to acute patient deterioration in an undergraduate BSN program. Nurse Educ Pract 2014;14:30–6. 10.1016/j.nepr.2013.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Resuscitation Council (UK). Immediate life support course. London: Resuscitation Council (UK), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bradley P, Cooper S, Duncan F. A mixed-methods study of interprofessional learning of resuscitation skills. Med Educ 2009;43:912–22. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03432.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]