Introduction

Understanding how human factors can impact on healthcare outcomes requires consideration of the complex interplay between organisational culture, people and the working environment, across domains such as teamwork, leadership, prioritisation, decision-making, communication skills and situational awareness.1

In the context of healthcare and patient safety, deficiencies in human factors skills often lead to clinical errors.2 Training in human factors has demonstrable benefits for clinical teams, yet exposure to such training for medical students is difficult to achieve and inconsistent.3 The transitional period for newly qualified doctors starting work also has a fraught reputation for patient safety events, with many junior doctors reporting a feeling of unpreparedness.4

The aim of this educational workshop was to improve medical student confidence and awareness of human factors, in the weeks immediately prior to commencing their first employment as junior doctors.

Methods

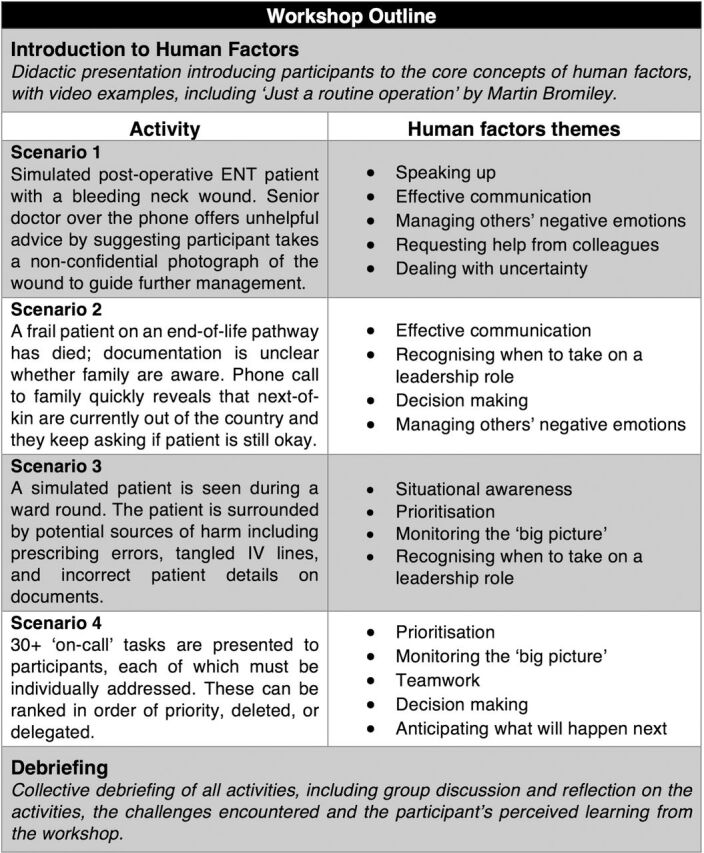

A half-day interactive workshop was designed, combining elements of low-fidelity simulation with traditional didactic teaching methods to focus on promoting awareness of non-technical skills related to core human factors themes, and consideration of how these may impact the delivery of safe patient care (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Outline of the half-day workshop. ENT, ear, nose and throat.

Participants

Attendees were final year medical students from a UK medical school during their final clinical placements, which were undertaken after having passed their finals examinations. This clinical placement serves as a preparatory period immediately prior to commencing employment as junior doctor.

Workshop structure

A brief introductory lecture introducing human factors concepts and their relation to the provision of healthcare was followed by four simulation-based activities, which were individually followed by collective debriefing and discussion.

Scenarios

Each activity was designed to encourage reflection and discussion around key human factors themes and were tailored to remove focus away from clinical skills and acumen, in order to encourage awareness of key non-technical skills. Debriefing then followed completion of each activity.

A prioritisation task undertaken in pairs involved organising a job list for a prospective ‘on-call’ shift. This was followed by a task assessing situational awareness, which required participants to assess a mock patient in the clinical environment to identify latent potential threats to their safety (eg, incorrectly disposed of sharps) and formulate appropriate responses.

Two simulated patient case vignettes involved the use of telephone discussions with colleagues and family members in difficult scenarios. Teamwork skills were challenged through a scenario requiring the participant to respond to a senior clinician who was advocating an unethical course of action, and the importance of communication skills was highlighted in a scenario necessitating the breaking of bad news in a suboptimal environment.

Results

A total of 44 students took part in the workshops in groups of four or five throughout the months of April and June 2019. The Human Factors Skills for Healthcare Instrument (HuFSHI) was utilised preworkshop and postworkshop to collect perceptions of self-reported confidence across statements related to human factors themes.5 There are 12 statements within the HuFSHI tool, each directly addressing a concept encompassed within the broader term ‘human factors’. These include constructively managing negative emotions, communicating effectively, prioritisation and ‘speaking up’. This tool is validated for use in multidisciplinary settings, as well as with simulation.

The mean total HuFSHI confidence score prior to starting our workshop was 5.89 (95% CI 5.44 to 6.33). Immediately after the workshop and debriefing sessions, the mean total confidence score was 6.62 (95% CI 6.22 to 7.02) with the paired sample t-test p value ≤0.001.

Across each of the 12 domains, students reported a mean increase in confidence postworkshop. The domains with the greatest self-reported improvement were in ‘prioritising when many things are happening at once’ and ‘monitoring the “big picture” during a complex clinical situation’. The area where students reported the least improvement in confidence was in ‘involving colleagues in your decision making process’.

Discussion

This workshop represented a low-cost and efficient means by which to train nearly qualified doctors in human factors, with the added benefit of improving confidence across a number of core domains relevant to providing safe patient care.

Our workshop was novel in that it maintained an explicit focus on human factors as a grouped concept, and the activities were not solely dependent on clinical acumen or expertise. This was purposefully designed into the workshops in order to provide participants with an explicit opportunity to focus their actions and subsequent reflections during debrief, on the potential role that human factors skills and deficiencies may take during their imminently forthcoming transition to clinical practice.

The results of this evaluation may be utilised to inform curriculum design and delivery at earlier stages in medical student curriculum, such as highlighting areas where students are self-reporting low levels of confidence.

However, from this educational evaluation it is evident that a short and focused human factors training workshop is effective and well-received by medical students. Further evaluation may be required in order to ascertain whether this improved awareness and confidence in human factors skills may translate into clinical practice change, or subsequent patient benefit.

Footnotes

Contributors: RLL designed and delivered the workshops in collaboration with SZ-V. RLL drafted the manuscript, which was reviewed by SZ-V. Both authors approved the manuscript for publication.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hollnagel E. Safety-I and safety-II: the past and future of safety management. CRC Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in A . To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Backhouse A, Malik M. Escape into patient safety: bringing human factors to life for medical students. BMJ Open Qual 2019;8:e000548. 10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sukcharoen K, Everson M, van Hamel C. A novel approach to junior doctor induction: a near-peer based curriculum developed and delivered by outgoing Foundation year doctors. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2014;3. 10.1136/bmjquality.u203556.w1603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reedy GB, Lavelle M, Simpson T, et al. Development of the human factors skills for healthcare instrument: a valid and reliable tool for assessing interprofessional learning across healthcare practice settings. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn 2017;3:135–41. 10.1136/bmjstel-2016-000159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]