Abstract

Cannabis use peaks in adolescence, and adolescents may be more vulnerable to the neural effects of cannabis and cannabis-related harms due to ongoing brain development during this period. In light of ongoing cannabis policy changes, increased availability, reduced perceptions of harm, heightened interest in medicinal applications of cannabis, and drastic increases in cannabis potency, it is essential to establish an understanding of cannabis effects on the developing adolescent brain. This systematic review aims to: (1) synthesize extant literature on functional and structural neural alterations associated with cannabis use during adolescence and emerging adulthood; (2) identify gaps in the literature that critically impede our ability to accurately assess the effect of cannabis on adolescent brain function and development; and (3) provide recommendations for future research to bridge these gaps and elucidate the mechanisms underlying cannabis-related harms in adolescence and emerging adulthood, with the long-term goal of facilitating the development of improved prevention, early intervention, and treatment approaches targeting adolescent cannabis users (CU). Based on a systematic search of Medline and PsycInfo and other non-systematic sources, we identified 90 studies including 9441 adolescents and emerging adults (n = 3924 CU, n = 5517 non-CU), which provide preliminary evidence for functional and structural alterations in frontoparietal, frontolimbic, frontostriatal, and cerebellar regions among adolescent cannabis users. Larger, more rigorous studies are essential to reconcile divergent results, assess potential moderators of cannabis effects on the developing brain, disentangle risk factors for use from consequences of exposure, and elucidate the extent to which cannabis effects are reversible with abstinence. Guidelines for conducting this work are provided.

Subject terms: Neuroscience, Addiction

Introduction

Cannabis use is extremely common [1–3], particularly among youth [e.g., reported by 38.3% of US 12th graders [4]. While there is substantial evidence that use is associated with harmful outcomes for a subset of cannabis users (CU) [5–11], many use without negative consequences. Cannabis has recently been decriminalized and/or legalized in many US states [12], and a bill to decriminalize cannabis was recently passed in the House of Representatives. In addition, cannabinoids have been proposed to have therapeutic potential [13]. However, current understanding of the effects of cannabis on brain and behavior—including neural mechanisms underlying cannabis-related harms—remains limited, particularly effects during neural development.

Cannabis use typically begins during adolescence and peaks in adolescence/emerging adulthood [14, 15]. Critically, adolescents may be more vulnerable to neural cannabis effects and cannabis-related harms due to ongoing brain development during this period [5, 16]. However, few studies have directly compared effects of cannabis between adolescents and adults, and results are mixed [17, 18]. Recent reviews and meta-analyses support cognitive deficits among adolescent relative to adult CU, and also suggest that these deficits may be reversible with abstinence [17, 19, 20]. Adolescence is a unique period characterized by the most substantial neural change aside from the perinatal period [21]. In particular, large-scale changes in neural architecture are thought to support the development of higher-order cognitive and emotional processes necessary for adaptive functioning in adulthood [22–25]. Therefore, effects of cannabis on the brain during adolescence may have important implications for long-term development.

Altered structure and function of brain regions implicated in executive functioning, emotion, reward, and memory have been reported among CU relative to nonusers [19, 26, 27], which may represent potential mechanisms of cannabis-related harms. However, the extant literature on neural correlates of cannabis use has been inconsistent [26, 28]. Many factors likely contribute to mixed results, including methodological differences, small sample sizes, inconsistencies in cannabinoid composition and potency, developmental timing of cannabis use, and various moderators of cannabis effects on the brain, such as sex and different patterns of use [16, 29, 30]. To address these limitations, this review seeks to: (1) review and synthesize extant literature on structural and functional neural correlates of cannabis use during adolescence and emerging adulthood; (2) identify gaps in the literature that critically impede our ability to accurately assess the effects of cannabis on adolescent brain function and development; and (3) provide recommendations for future research to bridge these gaps and elucidate the mechanisms underlying cannabis-related harms in adolescence and emerging adulthood. Strong data on the neural correlates of adolescent cannabis use is essential to facilitate the development of improved prevention, early intervention, and treatment approaches targeting adolescent CU.

Materials and methods

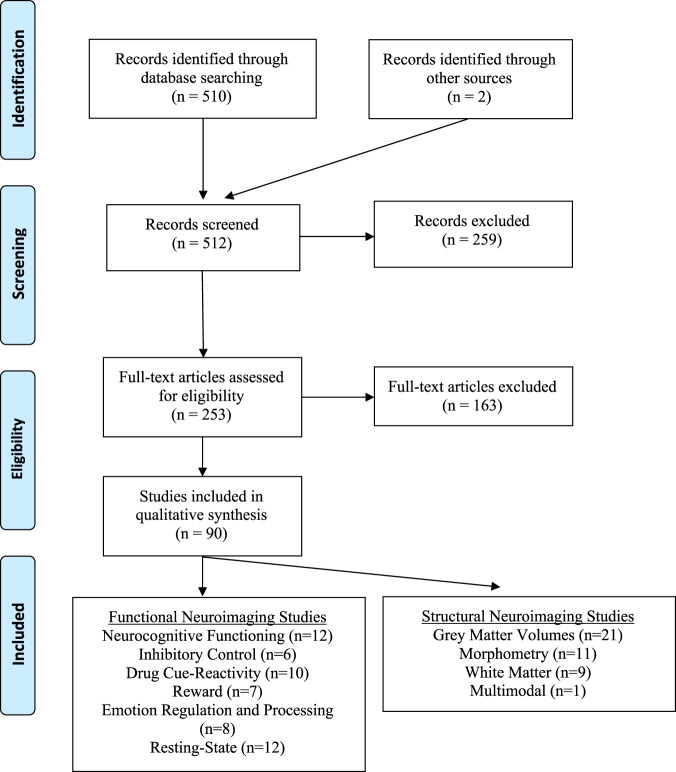

A systematic literature search of Medline and Psychinfo was conducted on June 10th, 2019 with 25 search terms encompassing the following parameters: adolescen* (OR young, youth, pubertal, puberty, minors, emerging adult, development) and cannabis (OR cannabidiol, cannabinoid, cbd, marijuana, thc) and mri (OR diffusion imaging, dti, fmri, fractional anisotropy, functional connectivity, magnetic resonance, microstructure, neuroimaging, resting state, white matter (WM)). This produced 510 studies (see Fig. 1 for PRISMA flowchart). Adolescence refers to the developmental epoch between childhood and adulthood, yet precise definitions vary [31]. While adolescence is traditionally considered to begin at puberty, the appropriate endpoint of adolescence remains debated. While many define adolescence as spanning from age 10–19 [32], it has been argued that an expanded definition of adolescence extending into the mid-20s is more consistent with neurodevelopmental trajectories, as well as the timing of major role transitions associated with adulthood [31]. In line with this expanded view, we define adolescence as extending until age 25, but have used the terms adolescence and emerging adulthood to accommodate the various definitions in the literature. Accordingly, inclusion criteria for the current review were as follows: mean age ≤ 25, minimum sample of 15 participants per group, and participants with personal cannabis use histories. THC administration studies in healthy volunteers and studies of prenatal cannabis exposure were excluded.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flowchart.

A systematic literature search of Medline and Psychinfo was conducted on June 10th, 2019, with 25 search terms, encompassing the following parameters: adolescen* and cannabis and mri. This produced 510 studies. 2 additional studies were identified during peer review. Studies were screened based on inclusion criteria: (1) participants with personal cannabis use histories (THC administration studies in healthy volunteers and studies of prenatal cannabis exposure were removed), (2) mean age ≤ 25, and (3) minimum cell size of 15 participants, and 90 studies were identified for inclusion in the current review. Note that studies that include multiple fMRI tasks or assess multiple structural characteristics are included in multiple sections, as appropriate.

The search strategy was developed by authors SDL, NM, and SWY. Author NM took the lead on screening manuscripts for inclusion, and all eligibility questions were resolved in consultation with SDL and SWY. SDL, NM, and SWY then divided the remaining 88 manuscripts into sections based on their primary methods and assigned sections to co-authors who conducted the literature review and drafted the accompanying table for their section. Two additional studies were identified during peer review, for a final total of 90 studies. To ensure that the information summarized in each table accurately reflects the published literature, each table was cross reviewed for accuracy by a second author, with points of discrepancy resolved by the first author (SDL; see Author Contributions).

Results

Sample characteristics

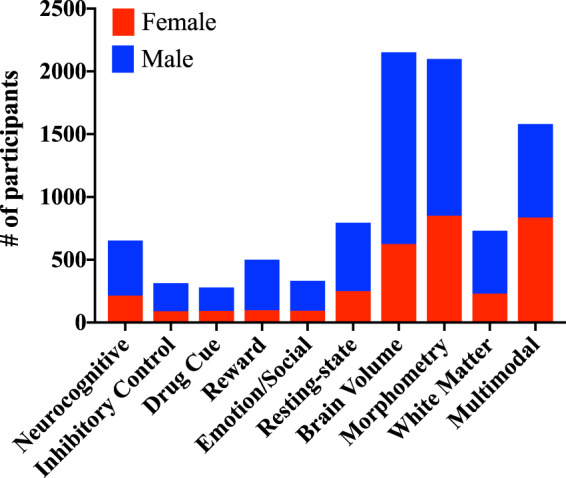

Ninety studies were selected for inclusion and further categorized into functional MRI studies using neurocognitive, inhibitory control, drug cue reactivity, reward, social/emotion, and resting-state paradigms, and structural studies of brain volumes, morphometry, and WM microstructure, as well as multimodal studies (see Fig. 1 for PRISMA flowchart). Together, these studies are comprised of data from 9441 adolescents and emerging adults (n = 3,924 CU, n = 5517 non-CU). Prevalence estimates for lifetime use are similar for male and female adolescents in the United States [33], yet 12 studies included solely male participants and no study included only females. Across all studies, only 35.9% of participants were women (see Fig. 2). Key findings and areas of convergence/divergence are summarized in the main text below and results of each study are detailed in accompanying tables.

Fig. 2. Prevalence of male and female participants across reviewed study domains.

Across all studies, only 35.9% of participants were female. Figure 2 displays the number of male and female participants included in each category reviewed.

Functional MRI literature

Neurocognitive functioning

As summarized in Table 1A, findings from cross-sectional studies generally indicate differences within corticolimbic and frontoparietal regions during memory task performance among youth with CU relative to non-users. However, the direction of these alterations has differed across studies and may be age-dependent, with increased activity reported among younger adolescents [34–36] and decreased activity reported among older adolescents and emerging adults [37, 38]. Whereas multiple studies using n-back tasks have not reported significant differences in neural activation during working memory performance between CU and non-users [39, 40], two studies found that working memory-related neural activation prospectively predicts initiation [41] or escalation [39] of use during spatial working memory [41] and n-back [39] tasks, respectively. In particular, increased frontoparietal [39, 41] and decreased visual and precuneus [41] engagement predicted cannabis use 6 months [39] and 3 years [41] later. Together, longitudinal data indicate limited effects of cannabis use on working memory function and raise the possibility that working-memory-related neural differences may precede cannabis use [39–41].

Table 1.

Primary findings from functional MRI studies of adolescent and young adult cannabis users.

| Ref | Design | CU (N, Fn) | NC (N, Fn) | Age (mean)a | Inclusion | Status | Abstinence | Task | Analysis method (including ROI or WB) | MC | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A) Neurocognitive studies | |||||||||||

| Padula [34] | CS | 17, 3F | 17, 5F | CU: 18.1 NC: 17.9 |

CU Mean lifetime use: 477.1 NC Mean lifetime use: 0.5 |

AB | ≥28 days | Spatial WM task | WB | k > 50 voxels, p corrected < 0.05, using MCS |

CU > NC (SWM v. vigilance): claustrum, caudate, putamen, thalamus, globus pallidus, insula, precuneus, postcentral gyrus, SPL Group × performance interaction: Positive association w/performance for CU and negative association for NC in the temporal gyrus and uncus, uncus and parahippocampal gyrus, thalamus and pulvinar |

| Schweinsburg [35]1 | CS | 15, 4F | 17, 5F | CU: 18.1 NC: 17.9 |

CU: Mean lifetime use: 480.7 NC Mean lifetime use: 0.5 |

AB | ≥28 days | Spatial WM task | WB | k > 1328 μl, p < 0.05 |

CU > NC (SWM > vigilance): SPL NC > CU (SWM > vigilance): MFG NC > CU (vigilance > SWM): cuneus, lingual gyrus |

| Jager [36] | CS | 21, 0F | 24, 0F | CU: 17.2 NC:16.8 |

CU: ≥200 lifetime uses; mean lifetime no. of joints = 4006^ NC: ‘non-using controls’; mean lifetime no. of joints = 1.8^ |

l | 5.1 weeks ± 4.2 |

Verbal WM; Pictorial AM Baseline + 7 day FU |

WB + ROI (group activation map) | WB: pFWE < 0.05; ROI: mean BOLD extracted and compared in SPSS |

WM task: WB: ns ROI: CU > NC (novel > practice): IFG, ACC, PCC, DLPFC AM task: WB and ROI: ns |

| Carey [37] | CS | 15, 2F | 15, 4F | CU: 22.4 NC: 23.3 |

CU: Current use (5–7 days/week for previous 2 years)b & lifetime use>500 joints & positive Utox NC: no use |

C | n.r. | Paired assoc. learning |

WB + ROI (group activation map) |

Bonferroni correction <0.05 k > 142 μL |

NC > CU (Corrected vs. repeated error): ITG, SPL, IPL, hippocampus, dACC, thalamus, putamen, PoCG and SMG Group × error type interactions: CU > NC (corrected errors vs. repeated errors): R thalamus NC > CU (corrected errors): supramarginal gyrus, IPL NC > CU (corrected errors vs. repeated errors): dACC, hippocampus, ITG, thalamus, temporal pole, SOG and putamen |

| Dager [38]1 | CS | 27, 15F | 33, 22F | CU: 18.3 NC: 18.4 |

CU: Past 3-month use NC: no use in past 3 months |

C | No Alch or other drugs | Figural Memory Task | WB + ROI (IFG, hippocampus) | ROI: mean BOLD extracted and compared in SPSS |

NC > CU (recognition ‘hits’): hippocampus, IFG Exploratory uncorrected sex × group interaction: NC > CU (men only): IFG, hippocampus; no significant differences in womenc |

| Cousijn [39] | PA | 32d, 11F | 41, 15F | CU: 21.4, NC: 22.0 |

CU: use >10 days/month for 2 years. NC: lifetime use <50 joints and none past year |

C | ≥24 h | N-back Baseline + 6 month FU | Tensor ICA (WM network) + ROI (WM network) |

Bonferroni correction <0.05, Spatial map threshold, Z > 2.3 pTFCE<0.05 |

No baseline differences between NC and CU in WM network. ↑ baseline WM network engagement ↑ cannabis use at 6 months (no association w/ baseline cannabis use). |

| Cousijn [40] | PA | 22, 7F | 23, 9F | CU: 21.0 NC: 22.1 |

CU: Use >10 days/month for 1.5 years NC: lifetime use <50 joints and none past year |

C | ≥24 h | N-back Baseline + 3-year FU | Tensor ICA (WM network) + ROI (WM network) | pTFCE < 0.05, Z > 2.3 | No main effects of time or group interactions between time and group. No sig. interaction between reaction time, accuracy, and group. |

| Tervo-Clemmens [41] | PA | 22, 10F | 63, 34F |

CU: 12.67 NC: 12.77 |

No use at age 12 (1st scan) CU: Lifetime use by age 15 (2nd scan) NC: No lifetime use by age 15 |

f + l | None |

Spatial WM, Baseline + 3 year FU |

WB |

AFNI 3dClustSIM (with -acf) k > 11 pFDR < 0.05 |

Baseline: CU > NC: MFG, IPL, paracentral lobule, cingulate gyrus, pre-SMA, occipital gyrus NC > CU: lingual gyrus, precuneus, occipital gyrus Follow-up: NC > CU: cuneus |

| Becker [42] | CS | 43, 9F (26 EOU, 17 LOU) | n/a | EOU: 21.0 LOU: 24.5 | Min. life use>10 g EOU: <16 years. | l | n.r. | N-back | WB + ROI (dlPFC & SPL) |

ROI: k > 20, pFWE < 0.05, SVC; WB correlations: k > 20, uc p < 0.001 |

ROI: EOU > LOU (2-back vs 0-back): left SPL WB: Across all participants, ↓ age of onset ↑ BOLD in IFG, SFG, STG, insula (1-back), precuneus, SPL, MFG, IFG, paracentral (2-back), putamen (n.r.) |

| Aloi [43]* | CS | 49, 19F | 33, 12F | 16.1 |

CU: Lifetime MJ or Alch NC: no lifetime MJ or Alch |

AB | ≥4 weeks | Affective Stroop | WB + ROI (amygdala) | AFNI 3dClustSIM (with acf) WB: k > 19 p < 0.001 ROI: > 5, p < 0.02 | CUDIT × task condition interaction: PCC, precuneus, IPL, MiTG, culmen, cerebellum: ↑ CUDIT score associated w/ incongruent > congruent > control |

| Becker [44] | CS | 42, 9F | n/a | 22.5 | Min. life use>10 g | l | 86.52 ± 235.66 days | Paired assoc. learning | WB + ROI (hippocamp., parahippocamp.) | ROI: k > 20, pFWE < 0.05, SVC; WB: k > 20, pFWE < 0.05 | No difference between EOU and LOU groups; no difference based on duration of use (median split); Median split of high-frequency users (versus low frequency) indicated increased BOLD activation of left parahippocampal gyrus during encoding |

| Sagar [144] | CS | 49e, 8F (EOU: 24, LOU:25) | 33f, 13F | CU: EON 23.7, LON 24.4 NC: 24.5 |

CU: ≥2500 lifetime uses & ≥5 days past week & pos Utox & DSM-IV MJ dependence. NC: <15 lifetime uses of MJ or any other illicit drug |

C | ≥12 h | Stroop | Whole-brain analysis +ROI (ACC) | WB: p < 0.0001 uncorrected k > 10 | Within-group analyses of task effects indicated qualitatively different patterns of activity among CU vs NC, but no between-group statistical comparisons reported. |

| B) Inhibitory control studies | |||||||||||

| Gruber [45] | CS | 23, 7F | 16, 9F | CU: 22.43 NC: 22.75 |

CU: Min 2500 lifetime MJ uses; min 5 days of MJ use in last 7 days; positive utox for MJ; met criteria for cannabis abuse or dependence NC: <15 lifetime uses of MJ or any other illicit drug; negative utox |

C | 12 h | MSIT | ROI: ACC | FDR p < 0.05, k > 14 |

CU > NC (interference vs control): L mid cingulum EOU > LOU (interference vs control): R mid cingulum LOU > EOU (interference vs control): L anterior mid cingulum |

| Tapert [46] | CS | 16, 4F | 17, 5F | CU: 18.1 NC: 17.9 |

CU: Min 60 lifetime MJ uses NC: <5 lifetime MJ uses |

AB | 58.4 days ± 52.8 | Go/No-Go | WB | p < 0.05, k > 22 |

CU > NC (No-Go vs baseline): bilateral anterior MFG & SFG, R superior MFG extending to the anterior insula, mPFC, bilateral PPC, R lingual gyrus CU > NC (Go vs baseline): R IFG & anterior insula, R SFG, R SPL, R IPL, medial precuneus |

| Behan [47]** | CS | 17, 1F | 18, 1F | CU: 16.5 NC: 16.1 |

CU: Currently in treatment for cannabis dependence NC: n = 4 reported lifetime MJ use (avg estimated lifetime use = 13 joints); n = 3 reported past month MJ use (avg 3 joints) |

T | Night before scanning | Go/No-Go | WB + ROI (22 regions of “response inhibition network”) | p < 0.05 corrected (t = 3.01, p ≤ 0.005, k > 277 μl based on MCS) Connectivity Analysis: p < 0.001 |

No group differences in WB or ROI analysis Exploratory connectivity analysis CU > NC (correlation between ROI time courses): L & R IPL, L tuber of cerebellum; R IFG, L IPL, L tuber of cerebellum |

| Claus [48]g | CS | 39, 11F | 37, 17F | CU: 15.97 NC: 16.05 |

CU: >1 MJ use in past month NC: ≤1 MJ use is past month & endorse “never” or “occasional” MJ use on Risky Behavior Questionnaire |

P | 24 h | BART | WB | voxel z > 2.3, cluster p < .025 | MJ + Alc > CU (linear risk vs linear control): L PoCG/SPL |

| Filbey [49] | CS | CUD: 44, 10F CU: 30, 9F | - |

CUD: 23.7 CU: 24.8 |

Min 4x/week for min past 6 months (both groups); positive utox for MJ | C | 3.38 days | SST | 7 network ROIs: basal ganglia, right frontal, SN/STN, orbital, pre-SMA and precentral gyrus, parietal, medial orbital | FWE p < 0.007 |

No group differences for stop success vs baseline PPI analysis CUD > CU (stop success vs baseline; right frontal seed): SN/STN network |

| Martz [50]*** | PA | 36, 9F | 21, 7Fh | HR: 19.88 Res: 20.68 |

HR: Min 2x/week binge drinking and/or monthly MJ from age 17-26 Res: Classified within the low MJ use trajectory group and report no monthly use from age 17-26 |

HR | 48 h | Go/No-Go | WB | Voxelwise FDR p < 0.05, cluster-forming threshold FWE p < 0.05 |

No group differences observed. Hierarchical Multivariable Logistic Regression High-risk youth displayed lower R dlPFC activation during correct inhibition |

| C) Drug cue reactivity studies | |||||||||||

| Karoly [51] | CS | 40, 19F | - | 18.83 | “Regular” cannabis use (~5x/week) | C | 12 h | Cue reactivity | WB GLM ROI (bilateral amygdala, VS, OFC) | cluster-corrected p < 0.05, z > 4.3 |

Cannabis > Control cues: bilateral fusiform, PCC, cuneus, parahippocampal gyrus, & ITG; L MFG, SFG, thalamus, precuneus, & MOG No significant correlations between ROI (cannabis > non-cannabis cues) and cannabis self-report measures |

| Filbey [52]2 | CS | 38, 7F | - | 23.74 | Min 4x/week MJ use for past 6 months | C | 72 h | Cue reactivity | WB GLM | cluster-corrected p < 0.05, z > 2.3 |

Cannabis>Control (neutral) cues: cluster in R PoCG, L fusiform gyrus, L cerebellum, R precentral gyrus and L IPL; cluster in R IFG, R insula, R lateral OFC, R STG Correlations (n = 25; clusters identified from above contrast) ↑ MPS ↑ cannabis-cue reactivity: bilateral medial OFC, R ACC, NAc |

| Charboneau [53] | CS | 16, 11F | - | 23.7 | Current CUD; utox positive for cannabis | CUD | ≥8 h (13.5 ± 2.1) | Cue reactivity | WB GLM to identify regions of significant (de)activation to cannabis cues (vs baseline); regions identified used as ROIs for add’l analyses | voxel threshold p < 0.001, extent k = 30, FWE-corrected p = 0.05 |

Cannabis cues main effect: inferior OFC, posterior cingulate gyrus, parahippocampal gyrus, hippocampus, amygdala, superior temporal pole, occipital cortex Cannabis>Control cues: inferior occipital gyrus, fusiform gyrus, hippocampus, amygdala Correlations ↑ craving ↑ cannabis cues main effect during first fMRI run: occipital cortex, parahippocampal gyrus, thalamus, hippocampus, superior temporal pole, middle occipital gyrus (p < 0.044–0.02) |

| de Sousa Fernandes Perna [54] | CS | 21, 6F | 20, 10F | 22.5 |

CU: MJ use 3-10x/week during the previous year NC: No current MJ use; experimental MJ use > 1 year prior allowed |

C | 1 week | Cue reactivity | ROI: striatum (bilateral putamen, caudate and globus pallidus) | pFWE‐corrected at cluster level <0.05 |

Sobriety: Cannabis group; Cannabis>Control (neutral) marketing cues: increased striatal ROI (p < 0.001) Intoxication: Treatment with cannabis > placebo decreased striatal ROI (p < 0.001); and cannabis marketing>control (neutral) cues increased striatal ROI (p = 0.014) |

| Vingerhoets [55]3 | PA | 23, 7F | - | 20.9 | MJ use >10 days/month for at least 2 years | C | 24 h | Cue reactivity |

Hierarchal multiple regression: baseline cue-induced ROI activation predicting cannabis use and problem severity at 3-year follow-up; ROIs: ACC, OFC, VTA, amygdala, striatum |

None |

Neither cannabis nor control cues in any ROI predicted weekly cannabis use (g) at 3-year follow-up ↑ baseline Cannabis > Control cues: L striatum (putamen; p < 0.001) ↑ CUDIT at 3-year follow-up |

| Filbey [56]2 | CS | 71, 16F | - | 24.46 (approx.) | Min 4x/week MJ use for past 6 months | C | ~72 h | Cue reactivity | PPI with 7 seeds: amygdala, ACG, NAc, OFC, hippocampus, VTA, insula | cluster-corrected p < 0.007, z = 2.3; between-group analyses: cluster-corrected p < 0.007, z = 1.96 |

CUD > NONDEP (Cannabis > Control cues): ↑ FC w amygdala seed & right MFG, right IFG, bilateral STG; ↑ FC w ACG seed & left SPL, IPL, precuneus, bilateral PoCG NONDEP > CUD (Cannabis > Control cues) ↑ FC w NAc seed & bilateral PoCG, left IPL and SPL, and right SFG; ↑ FC w OFC seed & right preCG, PoCG, SFG; ↑ FC w hippocampus seed & bilateral precuneus Cannabis>Control cues (N = 71): Greater functional connectivity between NAc seed and right cerebellum, bilateral caudate and ACG |

| Feldstein Ewing [57]4 | PA | 43, 7F | - | 16.09 | MJ use >7 of the past 30 days | JJ | 24 h | Cue reactivity following change talk (CT) or counter change talk (CCT) regarding MJ use | WB GLM | uc p < 0.001, extent threshold ≥20 voxels | ↑ activation in both CT and CCT for cannabis vs. control cues; CT > CCT, Cannabis > Control cues: STG, PoCG, claustrum, MFG, insula |

| Filbey [58]2 | CS | 37, 8F | - | 23.27 | Min 4×/week MJ use for past 6 months | C | 72 h | Cue reactivity | WB GLM: group comparisons by genotype |

CNR1: cluster-corrected p < 0.05, z > 1.7 FAAH: cluster-corrected p < 0.05, z > 1.9 Risk Alleles: cluster-corrected p < 0.05, z > 1.9 |

CNR1 rs2023239 G/A (n = 10)>A/A (n = 24) (Cannabis > Control cues): OFC, IFG, insula, dACG FAAH rs324420 C/C (n = 17)>A/A and A/C (n = 20) (Cannabis > Control cues): OFC, IFG, ACG, striatum, VTA Greater number of risk alleles (CRN1 G, FAAH C); Cannabis > Control (neutral) cues: OFC, striatum, cingulate, occipital and cerebellum |

| Feldstein Ewing [59]4 | CS | 41, 7F | - | 16.09 | MJ use >7 of the past 30 days | JJ | 24 h | Cue reactivity following presentation of unique CT or CCT statements | WB GLM: group comparisons by genotype | uc p < 0.001, extent threshold>20 voxels |

5-HT2A rs6311: C/C (n = 22)>C/T and T/T (n = 19) (Cannabis > Control cues after CT): MFG, SFG, temporo-occipital lobe, and parietal lobe/precuneus SLC6A4 rs2020936: A/A (n = 27)>A/G and G/G (n = 14) (Cannabis > Control cues after CT): ns |

| Cousijn [60]3 | PA | 33, 12F | 36, 13F | CU: 21.3 NC: 22.2 |

CU: MJ use > 10 days/month for 2 years; no history of treatment for cannabis use NC: MJ use < 50 joints in lifetime; no past-year use |

C | 24 h | Cue reactivity during approach/avoidance blocks | WB GLM | cluster-corrected p < 0.05, z > 2.3 |

Cannabis approach bias (approach block (approach-cannabis & avoid-control) > avoid block (avoid-cannabis & approach- control)): vmPFC and posterior cingulate gyrus CU > NC (Cannabis approach bias): ns Correlations (within CU group): ↑ lifetime cannabis use ↑ cannabis approach bias: amygdala, insula, IFG, vmPFC, parahippocampal gyrus ↑ cannabis problem severity at 6 months ↑ cannabis approach bias*: dlPFC, ACC *held when controlling for craving |

| D) Reward studies | |||||||||||

| Martz [50]*** | PA | HR: 36, 9F | Res: 21, 7F | HR: 19.88 Res: 20.68 |

HR: Min 2×/week binge drinking and/or monthly MJ from age 17–26 Res: Classified within the low marijuana use trajectory group and report no monthly use from age 17-26 |

f | 48 h | Modified MID | WB GLM ROI (dlPFC, IOFG, VS) HMLR | WB: cluster pFWE < .05 | ↑ VS activity (reward anticipation) ↑ MJ use |

| Martz [61] | LN | 108, 39F | - |

Time 1: 20.1 Time 2: 22.1 Time 3: 23.8 |

Ever used | f | 48 h | Modified MID | ROI (NAc) CLM | - | ↑ MJ use ↓ future NAc (reward anticipation) |

| Jager [62] | CS | 21, 0F | 24, 0F |

CU: 17.2 NC: 16.8 |

CU: ≥ 200 lifetime uses NC: ≤15 lifetime MJ uses |

l | 24 h | MID | WB GLM ROI (CN & Put) GLM | WB: pFWE < 0.05 |

WB: ns ROI: CU > NC (neutral anticipation): L CN Within MJ: ↑ R CN activity ↓ MJ use age of onset |

| Cousijn [63] | PA | 32, 11F | 41, 15 F |

CU:21.4 CU 6-mo FU: 21.9 NC: 22.2 NC 6-mo FU: 22.7 |

CU: >10 days/month, ≥ 2 years NC: <50 lifetime uses, no use in last 5 years |

f | 24 h | Iowa Gambling Task | WB GLM | Corrected cluster PFWE < .05 |

CU > NC (win vs loss): OFC, insula, posterior STG Within MJ: ↑ weekly use ↑ activity (win vs loss) in insula, caudate, VLPFC; ↑ weekly use ↑ activity (disadvantageous vs advantageous) in frontal pole, MiTG, STG and ↑ activity (win vs loss) in SFG |

| DeBellis [64] | CS | 15, 0F |

NC: 18, 0F PP: 23, 0F |

CU: 16.4 PP: 15.4 NC: 16.0 |

CU: CUD in full remission PP/NC: No CUD diagnosis All Groups: Negative saliva and urine toxicology screen |

Past CUD | >4 weeks | Decision-Reward Uncertainty Task | WB GLM (Post-hoc ROI of WB clusters: SPL & OFC) | Corrected cluster pFWE = 0.05 |

CU > NC & PP (behavioral risk): L SPL NC & PP > CU (reward minus no-reward): L OFC Within MJ: ↓ OFC (reward minus no-reward) ↑ likelihood of relapse |

| Lichenstein [65] | PA |

SH: 11, 0F E: 36, 0F |

SL: 111, 0F |

SH: 20.09 E: 20.07 SL: 20.10 |

Frequent usei | f | None | Card-guessing game |

ROI (NAc & mPFC) FC |

mPFC: cluster pFWE < 0.05 |

SL > E (win vs loss): negative NAc & mPFC FC in E, positive FC in SL Negative FC correlates with poor psychosocial outcomes |

| Ford [66] | CS |

CU: 15, 5F MDD + CU: 14, 4F |

NC: 17, 11F MDD 15, 13F |

MJ: 20.2 MDD + MJ: 19.9 NC: 20.0 MDD: 19.7 |

CU: ≥4 times/week, ≥ past 3 months MDD/NC: < 4 times/month in past year |

C | None | Music Listening Paradigm | WB GLM |

WB: pFDR < 0.05 WB MJ usej: p < 0.01, FDR-cluster WB BDI: p < 0.01, FDR-cluster |

MDD + CU > CU, NC, & MDD (preferred vs neutral music): increased activity in right MFG, right claustrum, dorsal ACC ↑ activity in mOFC, ACC ↑ MJ useb ↑ insula activity ↓ BDI scores |

| E) Emotion regulation and social processing studies | |||||||||||

| Zimmermann [67] | CS | 19, 2F | 18, 2F |

CU: 23.8 NC: 24.1 |

CU: DSM-IV criteria for MJ dependence NC: Lifetime use below 10 g |

C | >28 days | Emotion Processing Task | ROI level analysis, followed by gPPI within emotion processing networks using seed of maximal increase | PFWE < 0.05 (SVC) |

CU > NC (negative emotional stimuli): R mOFC CU > NC (gPPI: negative emotional stimuli): mOFC-DS FC, mOFC-amygdala FC NC > CU (gPPI: negative emotional stimuli): within-OFC FC CU > NC (gPPI: rest): R mOFC - L DS FC |

| Aloi [43]* | CS | 29, 7F | 33, 11F | CUD: 16.2 NC: 15.6 |

CUD: Cannabis Use Disorder (CUDIT ≥ 8) NC: CUDIT < 8 |

T | >4 Weeks | Affective Stroop Task | GLM analysis: whole brain and amygdala ROI | FWE, Amygdala—p < 0.02; WB—p < 0.001 |

CUD severity not associated with amygdala activity ↑ CUD severity ↑ activity in PCC, Precuneus, IPL |

| Spechler [68] | CS | 70, 20F | 70, 29F |

CE: 14.8 NC: 14.6 |

CE: >1 lifetime use NC: No lifetime use |

CE | Not reported | Affective Face Processing Task | GLM; Amygdala; Clusters that discriminated between angry and neutral faces, pooled across groups | WB—p < 0.005, k > 112 voxels (Estimated by 3dClustSim) |

CE > NC (angry faces): amygdala NC > CE (neutral faces): temporal parietal junction, dlPFC |

| Heitzeg [69] | PA | 20, 8F | 20, 6F |

CU: 19.8 NC: 20.5 |

CU: >100 lifetime uses NC: ≤10 lifetime MJ uses |

l | 48 h | Emotion-Arousal Word Task | GLM; WB; Amygdala | WB – p < 0.005, k > 77 voxels (Estimated by AlphaSim) |

NC > CU (negative words): R MFG, dorsolateral SFG, MiTG, STG, & calcarine fissure; insula, amygdala NC > CU (positive words): amygdala Mediation Analysis in CU: Caudal dlPFC activation during negative words mediated later negative emotionality; Cuneus/lingual gyrus activation during negative words mediated later resiliency |

| Gilman [71]5 | CS | 20, 11F | 23, 12F | CU: 20.6 NC: 21.6 |

CU: >1 once/week but not CUD NC: <5 lifetime uses |

C | Night before scanning | Social Influence Task | WB; Caudate; NAc | WB—p < 0.05 |

CU > NC (peer information): caudate* *associated with susceptibility to influence |

| Gilman [72]5 | CS | 20, 10F | 20, 10F |

CU: 20.4 NC: 21.4 |

CU: > 1 once/week but not CUD NC: <5 lifetime uses |

C | Night before scanning | Task Based: Social Influence Task | WB; NAc ROI | WB—p < 0.05 | CU > NC (social vs scramble): NAc* *correlated with reported cannabis use |

| Zimmermann [73] | CS | 23, 0F | 20, 0F | CU: 21.2 NC: 21.1 |

CU: > 200 lifetime uses; 3 days/week past year NC: <10 lifetime uses; No use in last 28 days |

C | 48 h | GLM—Event-related cognitive reappraisal; Seed-based (amygdala) connectivity | WB; Amygdala | PFWE < 0.05 |

CU > NC (negative affect reappraisal): bilateral frontal network (precentral, middle cingulate, supplementary motor) and amygdala; NC > CU (negative affect reappraisal): amgydala-dlPFC FC |

| Feldstein Ewing [74] | PA | 30, 5F | - | 16.1 | ≥ 7 past-month cannabis use episodes | C | 24 h | gPPI analysis of connectivity during change talk (CT)/sustain talk (ST) task | OFC – identified by conjunction analysis | FDR p < 0.05, k > 50 |

CT > baseline (OFC seed): IFG, precentral gyrus, anterior and posterior cingulate gyrus, SMA, superior frontal gyrus, pallidus, caudate, parahippocampal gyrus Baseline>CT (OFC seed): precuneus, superior/middle frontal gyrus, parahippocampal gyrus, thalamus, IPL, cingulate gyrus ↑ OFC-anterior cingulate/medial frontal gyrus FC ↑ post-treatment cannabis problems |

| F) Resting-state fMRI studies | |||||||||||

| Ref | Design | CU (N, Fn) | NC (N, Fn) | Age (mean) | Inclusion | Status | Abstinence | rsfMRI Analysis | Seed (if applicable) | MC | Findings |

| Camchong [76] | LN | 22, 8F | 43, 20F |

BL: CUD: 17.6 NC: 16.5 FU: CUD:18.6 NC: 17.4 |

CU: CUD; cannabis is drug of choice; >50 cannabis exposures; no abuse or dependence on other drugs (except alcohol abuse & nicotine dependence) NC: >5 lifetime exposures to any illicit drug |

T | n.r. | Seed-based | 5 ACC seeds: caudal, dorsal, rostral, perigenual, subgenual | Threshold from MCS: Family-wise α = 0.025; voxelwise p < 0.005; 3928 μL minimum cluster volume for cumulative MJ effect; 2352 μL minimum cluster volume for group × time interaction |

Time 2, controlling for time 1: NC > CU (caudal ACC seed): DLPFC, SFG, OFC Longitudinal results - group x time interaction: caudal ACC seed – dlPFC & SFG CUD (not NC): significant decrease in caudal ACC-dlPFC FC from time 1 to time 2 NC (not CUD): significant increase in caudal ACC-SFG FC from time 1 to time 2 Longitudinal results – predicting interscan use: Lower caudal ACC-OFC FC at time 1 predicted more cannabis use during interscan interval |

| Lopez-Larson [77]6 | CS | 43, 3F | 31, 7F | CU: 18 NC: 17.2 |

CU: ≥100 smoking events in last year; >15 lifetime uses of any other illicit drug and other drug/alcohol dependence during prior 2 months excluded NC: No DSM-IV Axis 1 dx |

C | n.r. | Seed-based | L and R OFC | FDR p < .05, k > 100 |

CU > NC (R OFC): L anterior and middle cingulate, precentral, R medial, middle, and superior frontal (L OFC): R MFG |

| Subramaniam [145]6 | CS | 43, 3F | 31, 7F |

CU: 18 NC: 17.2 |

CU: ≥100 smoking events in last year; >15 lifetime uses of any other illicit drug excluded NC: No DSM-IV Axis 1 dx |

C | n.r. | Seed-based | L and R OFC | FDR p < 0.05, k > 100 |

Within CU group: ↑ depression symptoms ↑ L OFC - L inferior parietal & L angular FC; ↑ anxiety symptoms ↓ bilateral OFC - R occipital & L OFC – R temporal FC |

| Pujol [78]7 | LN | 28, 0F | 29, 0F |

CU: 21 NC: 22 |

CU: Cannabis use onset before 16; current use >14x/week for min past 2 yrs; positive utox for cannabis and negative utox for other illicit drugs; >5 uses of illicit drugs and lifetime alcohol abuse/dependence excluded NC: <15 lifetime experiences with cannabis (none in the past month); negative utox |

C | Baseline: 12 h Follow-up: 28 days | Seed-based | PCC, anterior insula, hippoicampus | p < 0.005, k > 106; satisfies FWE correction per MCS |

CU > NC (PCC seed): ventral PCC; anticorrelation with areas of insula network (insula seed): L anterior insula, bilateral supramarginal gyri; anticorrelations with DMN areas: ventral PCC, medial frontal cortex, right angular gyrus NC > CU (PCC seed): dorsal PCC/precuneus (insula seed): ACC, superior brainstem (hippocampus seed): R hippocampus Longitudinal results CU > NC (PCC seed): regions of DMN (insula seed): regions of insula network NC > CU (PCC seed): regions of DMN |

| Blanco-Hinojo [79]7 | LN | 28, 0F | 29, 0F |

CU: 21 NC: 22 |

CU: Cannabis use onset before 16; current use >14x/week for min past 2 yrs; positive utox for cannabis and negative utox for other illicit drugs; >5 uses of illicit drugs and lifetime alcohol abuse/dependence excluded NC: <15 lifetime experiences with cannabis (none in the past month); negative utox |

C |

Baseline: 12 h Follow-up: 28 days |

Seed-based | 4 striatal seeds (R and L): dorsal & ventral caudate, dorsal & ventral putamen | p < 0.005, k > 129; satisfies FWE correction per MCS |

CU > NC (dorsal caudate seed; R): occipital. (dorsal putamen seed; R & L): precuneus, brainstem/cerebellum, inferior temporal. (ventral caudate seed; R & L): occipital, hippocampus, fusiform (ventral putamen seed; R & L): fusiform, superior parietal, cerebellum. NC > CU (dorsal caudate seed; R & L): ACC, SMA, medial frontal/ACC, premotor. (dorsal putamen seed; L): premotor. (ventral caudate seed; R & L): ACC, medial frontal/ACC, PCC, PFC, precuneus (ventral putamen seed; L): ACC, PFC Longitudinal results Baseline group differences no longer significant after 1-month supervised abstinence |

| Houck [80] | CS | HU: 36, 13F | LU: 33, 10Fk |

HU: 16 LU: 16.3 |

HU: Marijuana Use Scale score 21-47 LU: Marijuana Use Scale score 1–20 | C | n.r. | ICA: frontotemporal network | n.a. | p < 0.005, cluster >1200 mm3 | HU > LU: L MFG |

| Osuch [81]l | CS | 19, 7F | 19, 11F | CU: 19.9 NC: 20.2 |

CU: ≥4x/week for ≥3 months before study NC: Negative MJ urine screens; no current or past psychiatric dx |

C | n.r. | ICA: default mode network | n.a. | p < 0.01; TFCE |

Main effects of group (4 group analysis): R MFG, L culmen/fusiform, R caudate/temporal gyrus/parahippocampal gyrus. Post-hoc analyses: CU & CU + MDD > NC: right caudate/temporal gyrus/parahippocampal gyrus CU + MDD > NC, MDD, & CU: L culmen/fusiform CU < NC: R MFG Early (before 17)-onset (n = 36) > late-onset/non-user (n = 37): R temporal/fusiform/culmen/precuneus/bilateral occipital, R ACC, L temporal/occipital/fusiform, L SFG |

| Orr [82]8 | CS | 17, 1F | 18, 1F | CU: 16.5 NC: 16.1 |

CU: Currently in treatment for CUD NC: n = 4 reported lifetime MJ use (avg estimated lifetime use = 13 joints); n = 3 reported past month MJ use (avg 3 joints) |

T | Night before scanning | Voxelwise fALFF; VMHC | n.a. | fALFF: t = 3.00, p ≤ 0.005, k > 80 based on MCS; VMHC: t = 2.03, p ≤ 0.05, k > 481 |

fALFF CU > NC: R superior parietal gyrus, R SFG VMHC CU > NC: supramarginal gyrus NC > CU: pyramis of cerebellum, SFG |

| Jacobus [83] | LN | 23, 6F | 23, 4F | CU:17.7 NC: 17.5 |

CU: >200 lifetime MJ use days NC: <4 lifetime MJ use days |

C | 1–17 days (M = 5.1) at baseline | ASL: CBF | n.a. | p < 0.05, k > 13 based on MCS |

NC > CU: L superior and middle temporal gyri, L insula, MFG, L supramarginal gyrus CU > NC: R precuneus Longitudinal results No group differences after 28 days of abstinence |

| Behan[47]8** | CS | 17, 1F | 18, 1F |

CU: 16.5 NC: 16.1 |

CU: Currently in treatment for CUD NC: n = 4 reported lifetime MJ use (avg estimated lifetime use = 13 joints); n = 3 reported past month MJ use (avg 3 joints) |

T | Night before scanning | Seed-based | 2 networks derived from fMRI analysis: bilateral parietal-cerebellar and frontal-parietal-cerebellar | n.r. (replication of exploratory task-based fMRI finding) | CU > NC: bilateral IPL and L tuber of the cerebellum |

| Buchy [146]m | CS | 59, 46F | 208, 116F | 19.4 |

CU: Any use in last month NC: Cannabis naïve |

CHR/C | n.r. | Seed-based; 5 ROIs: R lPFC, anterior cingulate gyrus, cerebellum, L & R sensory/motor | Thalamus | p < 0.01 following Bonferroni correction for 5 ROIs for post-hoc analyses | No significant differences between current users and non-users in thalamic FC |

| Thijssen [147] | CS | 180, 0F | - | 17.2 | None | I | 30 days minimum | ICA: 15 components | n.a. | p < 0.05; FDR correction (only corrected for number of networks w/ significant effects) |

↑ duration of cannabis use ↓ executive control-auditory FNC; executive control - sensorimotor FNC, executive control – dorsal attention FNC; DMN-right frontoparietal FNC; salience-medial visual FNC; precuneus-auditory FNC; precuneus-primary visual FNC; ↑ duration of cannabis use ↑ right frontoparietal-sensorimotor FNC |

The ‘Inclusion’ column summarizes inclusion criteria for the CU and NC groups (where applicable) with regard to cannabis use. The ‘Findings’ column summarizes the primary results of each study that are relevant to each domain (i.e. for studies reporting results from multiple imaging modalities, only those results that pertain to the current domain will be included). Group comparisons are reported first, with additional analyses reported after (where applicable). Within each domain, articles are listed in the order they are discussed in the corresponding section of the main body of the text.

AB abstinent cannabis users, ACC anterior cingulate cortex, acf autocorrelation function, ACG anterior cingulate gyrus, AFNI Analysis of Functional NeuroImages software, Alch alcohol, AM associative memory, ASL arterial spin labeling, assoc. association, BART modified balloon analogue risk task, BDI beck depression inventory, C current cannabis user, CBF cerebral blood flow, CCT counter change talk, CE cannabis experimenters, CHR clinical high risk, CLM cross-lagged model, CN caudate nucleus, CS cross-sectional (single timepoint for imaging and clinical data), CT change talk, CU cannabis user, CUD cannabis use disorder, CUDIT Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test, dACC dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dlPFC dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, DMN default mode network, DS dorsal striatum, dx diagnosis, E escalating, EOU early-onset users (before age 16), f future use, F female, fALFF fractional amplitude of the low-frequency fluctuations, FC functional connectivity, FDR false discovery rate, FNC functional network connectivity, FU follow-up, FWE family-wise error correction, GLM general linear model, gPPI Generalized Psychophysiological Interaction, HMLR hierarchical multivariate logistic regression, HR participants with positive family history of substance use disorder classified as high risk based on adolescent pattern of binge drinking and/or MJ use, HU high cannabis use group, I incarcerated, ICA independent component analysis, IFG inferior frontal gyrus, IOFG inferior orbitofrontal gyrus, IPL inferior parietal lobule, ITG inferior temporal gyrus, JJ juvenile justice center-based recruitment, l lifetime cannabis user, L left, LN longitudinal neuroimaging (multiple neuroimaging timepoints), LOU late-onset users (age 16+), LU low cannabis use group, MC multiple comparison correction, MCS Monte Carlo simulation, MDD major depressive disorder, MFG middle frontal gyrus, MI monetary incentive delay, MiTG middle temporal gyrus, MJ marijuana; MOG medial occipital gyrus, mPFC medial prefrontal cortex, MPS Marijuana Problems Scale, MSIT Multi-Source Interference Task, N/A not applicable, NAc nucleus accumbens, NC non-cannabis user, NONDEP non-cannabis dependent, n.r. not reported, ns not significant, OFC orbitofrontal cortex, P recruited through an alternative to incarceration program, PA prospective associations (single timepoint of neuroimaging, longitudinal clinical data), PCC posterior cingulate cortex, PFWE pairwise family-error correction, PoCG postcentral gyrus, PP psychopathology, PPC posterior parietal cortex, PPI psychophysiological interaction, preCG precentral gyrus, pre-SMA presupplementary motor area, Put putamen, R Rright, Ref Reference, Res Resilient, ROI region of interest, SFG superior frontal gyrus, SH stable-high, SL stable-low, SMA supplementary motor area, SMG supramarginal gyrus, SN substantia nigra, SOG superior occipital gyrus, SPL superior parietal lobe, SST stop signal task, ST sustain talk, STG superior temporal gyrus, STN subthalamic nucleus, SVC small volume correction, SWM spatial working memory, T treatment-seeking cannabis user, TFCE threshold-free cluster enhancement, uc uncorrected; vlPFC ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, VMHC voxel mirrored homotopic connectivity, vmPFC ventromedial prefrontal cortex, VS ventral striatum, VTA ventral tegmental area, WB whole brain, WM working memory.

*Included in both neurocognitive and emotion regulation and social processing sections.

**Included in both inhibitory control and resting-state fMRI sections.

***Included in both inhibitory control and reward section.

^Descriptive information, not part of formal inclusion criteria.

1–8Overlapping samples.

aFor longitudinal studies, age at baseline reported here.

b8 subjects did not use cannabis for ≥4 weeks before scan.

cFound sex diffs but no interactions w/group.

dN = 30 at 6 moth follow-up.

eReflects updated N-size for fmri scan exclusion.

fCurrent cannabis users that do not meet DSM-IV criteria for cannabis dependence.

gStudy also included an alcohol (Alc) only (n = 23; M age = 16.35), and MJ + Alc group (n = 90; M age = 16.31).

hFH + resilient: participants have a positive family history of substance use disorder (maternal or paternal lifetime alcohol or substance use disorder), but minimal personal history of binge drinking or cannabis use during adolescence (age 17–26).

i Average frequency trajectory: SH = consistent, high frequency use, E = increasing frequency of use, SL = infrequent or no use.

j In last 28 days.

k“Low cannabis” group: youth with scores of 1–20 on the Marijuana Use Scale.

l Also included a MDD only (n = 18; M age = 19.6), and MDD + CU group (n = 16; M age = 19.8).

mCHR & Controls; current cannabis users and non-users were compared within the CHR and controls groups separately.

Several studies have also used dimensional (i.e., regression) or within-group (e.g., median split) analysis approaches to assess the effects of cannabis use characteristics (e.g., frequency, severity, age of initiation) on patterns of neural function during cognitive tasks. These data suggest that increased activation across several regions (i.e., frontoparietal, cingulate, insular, subcortical, and cerebellar) during neurocognitive processes may be linked to individual differences in cannabis use, including earlier age of initiation [42], and severity [43]/frequency of use [44]. Collectively, these data provide preliminary evidence for altered corticolimbic and frontoparietal activation among adolescent CU during neurocognitive task performance and suggest that these alterations may represent a risk factor for use rather than a consequence of exposure. Nonetheless, differences in cannabis inclusion criteria (e.g., lifetime vs. past-month use, as summarized in Table 1A) and task type (e.g., spatial working memory vs. n-back vs. associative learning tasks, as summarized in Table 1A) may contribute to variation in findings across studies.

Inhibitory control

Findings from studies of inhibitory control processing are summarized in Table 1B. Several studies converge in reporting significantly increased brain activation [45, 46] and/or functional connectivity [47] among CU relative to controls during successful inhibition, primarily within prefrontal, parietal, cingulate, and cerebellar areas. However, several other studies found no significant group differences [47–49]. Notably, increased neural activation among CU was coupled with comparable [45, 46, 48–50] or worse [47] behavioral task performance, suggesting possible compensatory patterns of neural response. Conversely, one study examining individuals at high familial risk for substance use found that lower right DLPFC activation was characteristic of those with personal cannabis/alcohol use during adolescence [50]. Given that this study combined adolescents with alcohol and cannabis use histories, it is difficult to reconcile these findings with the other studies reviewed. Overall, these data provide mixed evidence for altered frontoparietal, cingulate and cerebellar activation during inhibitory control performance among adolescent CU.

Drug cue reactivity

Findings from studies assessing neural response to cannabis cues are summarized in Table 1C. Among these, three compared cannabis to control cues [51–53] or tested a main effect of cannabis cues [53] in CU and reported greater cue reactivity to cannabis cues in brain regions involved in reward, incentive salience, and visual attention. Overlap (i.e., similar brain region reported in ≥2 studies) was found in the superior frontal gyrus, medial frontal gyrus, fusiform gyrus, inferior and middle occipital gyrus, inferior parietal lobule, precuneus, parahippocampal gyrus, hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus. Additionally, acute cannabis administration reduced striatal cue reactivity for CU compared to non-substance users [54].

Two studies investigated whether cannabis cue-reactivity relates to cannabis dependence and/or addiction severity by comparing dependent and non-dependent CU and found no group differences in activation [55] or reward-related functional connectivity [56]. Nonetheless, cue exposure was associated with heightened functional connectivity between the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) and the anterior cingulate gyrus, caudate, and cerebellum across all CU [56], and cue-reactivity in the left putamen prospectively predicted problem severity at 3-year follow-up [55]. Another study of treatment-seeking adolescent CU [57] found a prospective association between increased striatal and cerebellar activation while participants were concurrently exposed to cannabis cues and their own change talk (statements in favor of reducing their cannabis use) and reduced frequency of use at a 1-month follow-up, suggesting clinical relevance. Two studies examined whether genetic variation may impact cannabis cue-reactivity and found modest effects of risk alleles for the genes that encode the cannabinoid receptor 1 and fatty acid amide hydrolase [58], as well as variants of the serotonin 2A receptor gene [59]. Finally, one study directly compared cue-reactivity between CU and matched controls [60] and found no group differences, though associations with lifetime and future use were noted among CU.

Overall, these studies provide some evidence for heightened frontostriatal, frontoparietal, and frontolimbic activation to cannabis cues among CU, but findings are inconclusive regarding how neural cannabis cue-reactivity relates to cannabis use characteristics. Importantly, the 10 available studies represent only six independent samples (same or overlapping samples: [52, 55–60]), and most do not meet current minimum statistical standards, so findings should be considered preliminary.

Reward

Findings from studies assessing non-drug reward responses are summarized in Table 1D. Research using a Monetary Incentive Delay (MID) task reported greater cannabis use was associated with higher concurrent anticipatory reward signals in the striatum [50] and predicted lower striatal anticipatory reward signals two years later [61]. By comparison, a separate study reported greater striatal activity relative to controls during anticipation of neutral monetary outcomes that was inversely related to age of cannabis use onset [62]. Together, findings from MID tasks suggest that striatal anticipatory processing in adolescent CU may be sensitive to use patterns and trajectories.

Findings from reward task studies have been less consistent for cortical brain regions, possibly due to differences in reward paradigms. For example, both increases in orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) activity during Iowa Gambling Task performance [63] and decreases in OFC activity during a Decision-Reward Uncertainty task have been reported among CU relative to controls [64]. A separate study of individuals with escalating use reported negative functional connectivity between striatal and prefrontal regions during a card-guessing game [65], raising the possibility of disrupted coordination of reward responses. Cortical alterations have also been linked to use patterns and trajectories, with greater use linked to higher cortical reward responses [63, 66], and lower OFC responses predicting relapse [64]. Overall, the current literature suggests that adolescents with CU display altered non-drug reward processing in frontostriatal regions.

Emotion regulation and social processing

Findings from studies utilizing emotion regulation and social processing tasks are summarized in Table 1E. Four studies have compared neural response to emotionally valanced stimuli between adolescent CU and non-users [43, 67–69], with most finding increased activation among CU in multiple brain regions. One study [67] found CU displayed greater activation in the right medial OFC and increased medial OFC coupling to contralateral dorsal striatum and amygdala to negative emotional stimuli during an emotion processing task. Another study using an affective Stroop task found a positive association between cannabis use disorder (CUD) severity and activation in precuneus, posterior cingulate, and inferior parietal lobule [43]. A third study using an affective face processing task [70] reported greater activation to angry faces in amygdala, middle temporal gyrus, and inferior frontal gyrus among individuals reporting light cannabis experimentation compared to controls [68]. In contrast, a fourth study found that CU displayed less activation to negative words on an emotion-arousal word task in temporal, prefrontal, and occipital cortices, insula, and amygdala [69]. While numerous between-study differences may account for these inconsistent findings, one important factor may be duration of abstinence prior to scanning: the study with the shortest abstinence (48 h) found a decreased neural response [69], whereas studies with more prolonged abstinence (28 days) found increased neural responses [43, 67].

Two studies using social influence tasks found increased neural responses within the caudate and NAcc in response to peer information among CU [71, 72]. There has also been one study in which male CU exhibited higher frontal, cingulate and amygdala activity, as well as reduced connectivity between amygdala and dorsolateral PFC, compared to controls during reappraisal of negative affect, suggesting diminished top-down control over negative affect [73]. Finally, another study examined functional connectivity of the OFC when treatment-seeking CU were exposed to their own change talk statements from a recent motivational interviewing session [74]. Compared to baseline, the change talk condition was associated with both increases and decreases in OFC connectivity with a variety of frontal, parietal, and subcortical regions, and greater connectivity with the anterior cingulate/medial frontal gyrus was associated with more post-treatment cannabis problems. Together, these studies support increased connectivity among CU during active regulation of behavior, providing an important foundation for future work. Overall, these data suggest that adolescent CU display altered frontolimbic activation and connectivity during emotional processing, with most consistent evidence found for the OFC.

Resting state

While task-based fMRI paradigms examine patterns of neural activation during specific cognitive tasks, resting-state fMRI (rsfMRI) aims to characterize intrinsic connectivity patterns independent from any distinct mode of cognitive processing [75]. Findings from these studies are summarized in Table 1F. Overall, resting-state connectivity of frontal [76–83], parietal [47, 78, 79, 82, 83], and cingulate [76–79] regions has been most consistently implicated among adolescent CU. However, the direction of these effects varies. Nonetheless, frontal, cingulate, and parietal regions are each implicated in multiple canonical resting-state networks [84], so it is unsurprising that the relationship between cannabis exposure and functional connectivity in these areas would be complex, particularly during adolescence when refinement of functional architecture is still ongoing [24, 85, 86]. Future research with larger, independent samples and more consistent methods is urgently needed to replicate and extend extant findings.

Several of the studies reviewed here examined differences in resting-state connectivity following a period of abstinence [78, 79, 83]. These reports converge in reporting that group differences are attenuated [78] or no longer present [79, 83] following one month of abstinence. These findings provide preliminary evidence that alterations in functional connectivity may be reversible following discontinuation of use. Nonetheless, two studies reported on the same sample of individuals [78, 79], and all focused on different regions and/or neural characteristics (functional connectivity [78, 79], cerebral blood flow [83]). Overall, the rsfMRI literature suggests that frontoparietal connectivity is altered among current CU, and that these effects may be attenuated with abstinence.

Structural MRI literature

Brain volume

Findings from cross-sectional studies comparing gray matter volume (GMV) between adolescent CU and non-users are summarized in Table 2A [87–99]. Aggregate findings indicate smaller thalamic [87] and larger amygdala [98, 99] volume among adolescent CU. Alterations in cerebellar [87–89, 94, 99], PFC [93, 99], and hippocampal [95, 99] volume have also been reported, though the direction has not been consistent across studies. In addition, several studies have found no significant volumetric differences between CU and non-CU groups [90–92, 96, 97]. These inconsistencies may relate to between-study differences in key demographic features proposed to influence the link between cannabis use and GMV during adolescence, such as sex [93, 98], age of first use [95, 100], frequency of use [100], synthetic versus plant-derived cannabis [87] and genetic variation [92]. It may be necessary to account for these and other key moderators in future work.

Table 2.

Primary findings from structural MRI studies of adolescent and young adult cannabis users.

| Ref | Design | CU (N, Fn) | NC (N, Fn) | Age (mean) | Inclusion | Status | Abstinence | fMRI Analysis | ROI (if applicable) | MC | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A) Gray matter volume studies | |||||||||||

| Nurmedov [87] | CS | 20, 0F | 20, 0F |

SC: 23.95 NC: 25.85 |

SC: SC as drug of choice; 1 yr min duration of use OR current use >5x/week NC: No history of psychopathology or substance use | CSU | >7 days | WB VBM, independent samples t-test | N/A | FWE correction, p < 0.05 (cluster-forming threshold = 20 voxels) | NC > SC: bilateral thalamus, L cerebellum |

| McQueeny [98] | CS | 35, 8F | 47, 11F |

CU: 18 NC: 17.7 |

CU: Any cannabis use; max 30 lifetime uses of other illicit drugs NC: No history of substance use |

AB | 28 days | ROI multiple regression | AMY | None |

ns Cannabis × gender interaction CU > NC: R AMY; females only |

| Orr [99] | CS | 46, 16F | 46, 22F |

EL: 14.6 NC: 14.5 |

EL: 1–2 lifetime cannabis uses NC: No illicit substance use, including cannabis |

EL |

n.r. n = 6 used in last 7 days n = 10 used in last 30 days |

WB VBM | N/A | FWE p < 0.05, k ≤ 600, threshold determined with AFNI 3dTTest + + with the option – clustsim |

EL > NC: L temporal cluster, including frontal and temporal cortical regions, AMY, HPC, Put, Pd, IC, PHG, Cd; R temporal cluster, including temporal cortical regions, AMY, HPC, Put, Pd, PHG, IC; bilateral posterior cluster, including temporal, parietal, occipital, and cerebellar regions Behavioral Associations ↑ GMV in L & R temporal clusters ↓ perceptual reasoning ↑ GMV in L temporal cluster ↓ psychomotor speed (non-dominant hand) ↑ GMV in R temporal cluster ↑ generalized anxiety at 2 yr FU |

| Koenders [88] | LN | 20, 4F | 22, 5F |

Baseline: CU: 20.5 NC: 21.6 Follow-up: CU: 24.0 NC: 24.8 |

CU: Self-reported use for >2 years, >10 days per month with no tx history NC: <30 lifetime MJ uses, no use in the past year |

C | >24 h |

WB + ROI VBM, multiple regression |

OFC, ACC, insula, striatum, thalamus, AMY, HPC, cerebellum | ROIs: p < 0.001, FWE-corrected cluster probability of p < 0.05 adjusted for the small search volume WB: p < 0.001, whole-brain FWE-corrected cluster probability of p < 0.05. |

Baseline: CU > HC: cerebellum (ROI) Follow-up: ns Within CU group: ↑ quantity of use (gm/week) ↓ AMY/HPC, STG ↑ CUDIT ↓ L AMY |

| Cousijn [89] | CS | 33, 12F | 42, 16F |

CU: 21.3 NC: 21.9 |

CU: Cannabis use 10+ days in last month or > 240 days in last 2 years with no tx history. Mean CUDIT score of CU sample: 12.4 ± 5.7) NC: <50 lifetime uses of cannabis, no use in the past year |

C | >24 h | WB + ROI ANCOVA | OFC, ACC striatum, AMY, HPC, cerebellum | ROIs: p < .005, with FWE-corrected cluster probability of p < 0.05 adjusted for the small search volume. WB: p < 0.001, with WB FWE-corrected probability of p < 0.05 | CU > NC: anterior cerebellum (ROI) Within CU group: ↓ AMY, HPC ↑ amount of use/dependence |

| Medina [94]1 | CS | 16, 4F | 16, 6F | CU: 18 NC: 18 | CU: >60 lifetime uses, <25 lifetime uses of drug other than MJ, alcohol, nicotine, not meeting criteria for heavy drinking NC: <5 lifetime uses of cannabis, no use in past month. | AB | 4 weeks | ROI OLS multiple regression | Anterior, superior, posterior and inferior posterior vermis with cerebellar hemispheres (R = 5) | Not performed | AB > NC: posterior inferior vermis |

| Medina [93]1 | CS | 16, 4F | 16, 6F |

CU: 18.1 NC: 18 |

CU: >60 lifetime MJ uses, <25 lifetime uses of other drugs (except alcohol and nicotine), heavy drinking excluded NC: <5 lifetime uses of cannabis, no use in past month |

AB | 28 days | ROI OLS multiple regression | Three PFC regions: posterior, anterior dorsal, anterior ventral; manually defined | None |

ns Cannabis x gender interaction CU > NC: PFC female only NC > CU: PFC male only |

| Lisdahl [95]* | CS | 55, 5F | 65, 17F |

CU + AD HD: 24.3 CU-AD HD: 23.6 NC + AD HD: 24.6 NC-AD HD: 23.4 |

CU: Minimum monthly cannabis use during past year NC: <4 MJ uses in past year | C/ADHDa | >36 h | ROI VBM, Standard least squares multiple regression Freesurfer cortical surface approach | Subcortical Freesurfer segmentation volumes | Benjamini Hochberg FDR correction for each hemisphere |

NC > CU: L HPC Early (< age 17)>Late CUO (age 17+): L NAc |

| Thayer [90]** | CS | 201, 52F | 238, 82F |

CU: 16 NC: 15.97 |

CU: Cannabis use in last 30 days; min weekly use NC: Cannabis use in last 30 days; <weekly |

JJ |

Alcohol: >24 h Cigarette Smoking: >2 h |

WB VBM, GLM | N/A | MCS, 5000 permuntations, Voxelwise TFCE ( ≥ 1000 contiguous voxels in VBM models) | ns |

| Weiland [91] | CS | 50, 9 F | 50, 14 F | CU: 16.65 NC: 16.77 | CU: Daily cannabis use on Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB) for past 60 days NC: No MJ use in past 60 days | C | n.r. | WB + ROI VBM, GLM | NAc, AMY, HPC, cerebellum | MCS, 5000 permutations. Voxelwise threshold using FSL randomize permutation, clusterwise correction t > 2.3 | ns |

| Batalla [92] | CS | 29, 0F | 28, 0F |

CU: 20.8, NC: 22.1 |

CU: Onset before 16, 14-28 joints/week currently and for minimum of last 2 years NC: <15 lifetime uses of cannabis, no use in past month |

C | n.r. | WB + ROI Two-sample t-test | PFC, neostriatum, ACC, HPC |

WB: p < .05 FWE-corrected; ROI: p < 0.05 FWE-corrected with small volume correction, also performed at p < 0.0001 uncorrected |

CU > NC: left postcentral gyrus Cannabis × COMT interaction ↑ val alleles ↓ caudate (CU only) ↑ val alleles ↑ caudate (NC only); ↑ val alleles ↑ L AMY (CU only) ↑ val alleles ↓ L AMY (NC only) |

| Koenders [96] | LN | 20, 6F | 23, 10F |

Baseline: CU: 20.63 NC: 21.79 FU: CU: 24.16 NC: 25.07 |

CU: Self-reported use for >2 years, >10 days per month with no tx history NC: <50 lifetime uses of cannabis, no use in past year |

C | >24 h | ROI; manually defined Repeated-measures ANCOVA | HPC | False discovery rate (FDR) correction | ns |

| Gilman [97]* | CS | 20, 11F | 20, 11F | CU: 21.3 NC: 20.7 |

CU: MJ use >1 time/week, no CUD NC: <5 lifetime uses of cannabis, no use in past year |

C | Day of study |

WB + ROI VBM; multivariate GLM |

NAc, AMY | Bonferroni correction, cluster threshold | ns |

| Battistella [100] | CS | 57, 0F | - | RU: 23 OU: 25 |

RU: >10 joints/ month OU: >1 joint/month & <1 joint/week, within last 3 months |

RU/OU | Not reported; urine and blood samples taken to establish THC concentration |

WB VBM |

N/A | FWE correction, k > 60 |

OU > RU: temporal pole, parahippocampal gyrus, L insula, L OFC RU > OU: 3 cerebellar clusters Correlation Analysis ↑ frequency of past 3-month use ↓ bilateral temporal pole, L sup orbital gyrus, L mid temporal gyrus, R precuneus, L insula, and L parahippocampal gyrus volumes Age of Onset Analysis Regular user (regardless of age of onset), and early-onset occasional users displayed ↓ GMVs in most regions, as compared to late-onset occasional users |

| Cheetham [102] | PA | 28, 16F | 93, 43F | Baseline: 12.7 Follow-up: 16.5 |

CU: Self-reported MJ use on Youth Risk Behavior Survey at FU (only 11% had 10+ lifetime uses) NC: No lifetime MJ use |

f |

BL: preceding use FU: Not reported |

ROI Logistic regression |

AMY, HPC, OFC, ACC | None |

NC > f (age 12): OFC Smaller OFC volume at age 12 predicted cannabis use initiation by age 16 |

| Padula [101]1 | CS | 22, 5F | - | 17.8 | Self-report, >200 lifetime MJ episodes | AB | 28 days | ROI Linear regression | AMY | None | ↓ AMY ↑ craving |

| Welch [103]2 | LN | 25, 10F | 32, 17F |

CHR CU: 21.76 CHR NC: 21.11 |

CU: Any MJ use during 2-year FU period NC: No MJ use during 2-year FU period |

CHR | n.r. continuous self-report |

ROI Repeated-measures ANOVA |

Thalamus, AMY/HCP complex | None | CHR CU > CHR NC: 2-year change (↓) in L & R thalamus |

| Welch [104]2 | LN | 23, 8F | 32, 17F | CHR CU: 21.8 CHR NC: 21.1 | CU: Any MJ use during 2-year FU period NC: No MJ use during 2-year FU period | CHR | n.r. continuous self-report |

WB + ROI TBM, GLM |

Thalamus, AMY/HCP, frontal lobes | FWE p < 0.05; small volume correction for ROIs | CHR CU > CHR NU: 2-year change (↓) in right anterior hippocampus and left superior frontal lobe (no longer significant following removal of participants with comorbid drug use) |

| Buchy [105] | CS | 132, 44F | 387, 161F |

CHR CU: 19.5 CHR NC: 18.4 |

CU: ≥2 on AUS/DUS severity scale NC: <2 on AUS/DUS severity scale |

CHR | n.r. AUS/DUS self-report |

ROI Linear Regression |

Thalamus, HPC, AMY | None |

CHR NC > CHR CU: amygdala* *Result was no longer significant after controlling for tobacco and alcohol use |

| Koenders [106] | CS | 80, 0F | 33, 0F (SZ-CUD) 84, 0F (NC) |

SZ + CUD:22.18 SZ-CUD: 22.15 NC: 23.19 |

CUD: DSM-IV diagnosis of cannabis abuse or dependence NC: No lifetime DSM-IV Axis-1 disorder, no current psychotropic drug use |

SZ + CUD/SZ-CUD/NC | n.r. |

ROI Linear regression |

HPC, AMY, thalamus, caudate, putamen, OFC, ACC, insula, parahippocampus and fusiform gyrus | p <0.01, Bonferroni-corrected for 11 ROIs |

SZ + CUD > SZ-CUD: putamen NC > SZ + CUD: insula |

| Haller [107]** | PA | 33, 4F | 17, 10F |

FEP CU: 22.7 FEP NC: 23.9 |

CU: >10 lifetime uses; Heavy: Near daily (or more) for at least 1 year Light: Less than daily NC: <10 lifetime cannabis uses |

FEP | n.r. | WB VBM, GLM | N/A | TFCE, p < 0.05 | ns |

| B) Morphometry Studies | |||||||||||

| Ref | Design | CU (N, Fn) | NC (N, Fn) | Age (mean) | Inclusion | Status | Abstinence | Analysis Method/ Software | Morphometry Metric(s) | MC | Findings |

| Jacobus [108] | LN | 30, 11 F | 38, 9 F | CU = 18.2 (BL), 19.6 (1.5 yr FU), 21.2 (3 yr FU) NC = 17.7 (BL), 19.1 (1.5 yr FU), 20.8 (3 yr FU) |

CU: >100 MJ episodes and <150 alcohol episodes at baseline NC: <10 MJ episodes and <150 alcohol episodes at baseline |

C + ALC | Monitored abstinence for 4 weeks | Freesurfer analysis of 34 independent standard neuroanatomical cortical regions in each hemisphere | CT | None |

CU + ALC > NC: 23 regions, predominantly within frontal and parietal cortices Correlations ↑ lifetime alcohol use ↓ CT (controlling for MJ use): L paracentral lobule pericalcarine cortex, postcentral gyrus, & precentral gyrus; R caudal ACC, fusiform, lingual gyrus, postcentral, & precentral CU group only* ↑ cumulative MJ use ↑ CT: L inferior temporal cortex, R entorhinal cortex ↓ age of regular MJ use onset ↑ CT: R entorhinal cortex *all controlling for alcohol use. |

| Lopez-Larson [109] | CS | 18, 2F | 18, 6F |

CU = 17.8 NC = 17.3 |

CU: At least 100 uses in the past year (“heavy MJ use”) NC: No MJ use |

C | n.r. | Freesurfer | CT | WB: Gaussian-simulation nonparametric inference testing (cluster-wise probability ≤ 0.001, initial cluster-forming threshold p = .05) |

CU > NC: bilateral lingual, R superior temporal, R inferior and superior parietal, and L paracentral regions (WB) NC > CU: R caudal middle frontal, bilateral insula & SFC (WB) Welch’s two-sample t-test Identified most ‘different’ ROIs from 156-region parcellation: L sulcal central insula, R sulcal calcarine, and L gyral superior-lateral temporal Correlations ↓ age of regular use ↑ R SFC thickness; ↑ urinary cannabinoid level ↓ R caudal middle frontal, R lingual, and L superior frontal gyrus |

| Mashhoon [110] | CS | 15, 2F | 15, 2F |

CUD = 21.8 NC = 22.3 |

CU: Minimum 1450 MJ uses (at least 500 in the past two years), minimum 5 times in the week prior to first visit, positive utox for cannabinoids on scan day, DSM-IV criteria for MJ abuse/dependence NC:<5 episodes of MJ use |

CUD | n.r. | Freesurfer: whole brain and ROIs: AMY, Th, HPC, Pd, Cd, Pu, and cerebellum | CT | Cluster-corrected p < 0.05 (MCS) |

ROI: NC > CUD: thalamus WB: NC > CUD: R fusiform gyrus |

| French [112]b | CS/LN | SYS: 313, 171F ALSPAC: 91, 0F IMAGEN: 82, 45F | SYS: 636, 319F ALSPAC: 204, 0F IMAGEN: 251, 143F | Baseline: SYS: 15.1 ALSPAC: 19.6 IMAGEN:14.5 |

CU: Cannabis use by age 16 NC: No cannabis use by age 16 |

C | n.r. | Mean CT | CT | N/A |

SYS: interaction between MJ use (never/ever) and genetic risk for schizophrenia score on age-adjusted cortical thickness: CT decreases with increasing risk score in MJ users but not in non-users) ALSPAC: (1) no difference in CT between those who never and those who ever used MJ in high- and low-risk groups. Within high-risk group: (2) difference in age-adjusted cortical thickness between never and most frequent users; (3) difference in age-adjusted CT between light and most frequent users. IMAGEN: (1) interaction between MJ use (never/ever) and risk score on change in cortical thickness (14.5 to 18.5 years old) (2) in females, a main effect of risk score, but not MJ use. |

| Epstein [111] | LN | CUD: 17, 8F EOS/CUD: 11, 1F | NC: 34, 18F EOS/NC: 17, 9F |

CU = 16.6 EOS/CU = 17.5 NC = 16.5 EOS/NC = 16.3 |

CU: >50 exposures to MJ by age 17 and no lifetime abuse or dependence on other drugs except for alcohol abuse or nicotine dependence. NC: ≤5 exposures to any illicit drug (except alcohol) |

CUD, EOS/CUD | Positive UA: At BL:CU = 4, EOS/CU = 4, NC = 0, EOS/NC = 0 At FU: CU = 8, EOS/CU = 5, NC = 2, EOS/NC = 1 | Freesurfer (CT in heteromodal association areas): SFG, inferior frontal regions (pars triangularis, orbitalis, and opercularis), IPC, SMG, and STG | CT | None |

EOS/NC, NC > EOS/CUD, CUD: 1.5-year change (↓) in L/R SMG, L/R IPC, R pars triangularis, L pars opercularis, L SFG and L STG. Correlations ↑ lifetime MJ exposure ↑ attenuation of CT changes in L/R SFG, R SMG, L IPC, R pars triangularis, L pars opercularis (controlling for BL CT) |

| Lisdahl [95]* | CS | CU: 18, 2F ADHD/CU: 37, 3F | ADHD/NC: 44, 10F NC: 21, 7F | CU = 23.6 ADHD/CU = 24.3 ADHD/NC = 24.6 NC = 23.4 |

CU: MJ used at least monthly during the previous year. NC: MJ used <4 times in the previous year |

C, ADHD/C | ≥24 h. prior to scanning | Freesurfer | CT | MCS for cluster-wise correction at p = 0.05 (cortical) FDR using Benjamini and Hochberg (subcortical) |

NC > CU: L SFS, ACC, PCC, R SFS, precentral gyrus NC > CU: left hippocampus Early CUO (age≤16)>Late CUO (age 17+): R superior frontal, postcentral (within ADHD groups only) |

| Gilman [97]* | CS | 20, 11F | 20, 11F |

CU = 21.3 NC = 20.7 |

CU: Used MJ at least once per week but were not dependent. NC: No MJ use in the past year and <5 times in lifetime |

C | Day of the study | VBM (GM density) of WB and L & R NAc and AMY; FSL FIRST (shape analysis) in L&R NAc and AMY | GMD, shape | Permuation-based nonparametric testing correct[ed] for multiple comparisons across space Bonferroni correction for the ROI analysis |

CU > NC (GMD): L NAc extending into SCC, HTh, SEA, and L AMY Correlations ↑ L NAcc and L AMY density ↑ smoking occasions/day (both) and joints/occasion (L NAc only). Shape analyses found differences between groups in R AMY and L NAc. |

| Weiland [91] | CS | 50, 9F | 50, 14F |

CU = 16.65 NC = 16.77 |

CU: Daily users – used MJ 90 days out of the last 90. NC: No MJ use in the last 90 days |

C | n.r. | VBM (modulated; GMD), and FSL FIRST (shape analysis) in NAc, AMY, HPC, cerebellum, and WB | GMD, shape | VBM: MCS cluster-wise threshold of t > 2.3 FSL FIRST: MCS cluster-wise threshold of F > 3.0 | ns |

| Bangalore [113] | CS | FES/CU 15, 6F | FES/NC: 24, 6F NC: 42, 18F |

FES = 24.3 (male), 25.7 (female) NC = 24.9 (male), 26.1 (female) |

CU: >10 lifetime uses NC: No MJ use |

FES/C | n.r. | VBM in CB1-rich ROIs: bilateral dlPFC, HPC, PCC, and cerebellum | GMD | FWE |

FES/NC > FES/CU: R PCC NC > FES/CU: R PCC |

| James [114]*** | CS | SZ/AB 16, 5F | SZ/NC: 16, 5F NC = 28, 10F | SZ/CU = 16.4 SZ/NC = 16.2 NC = 16.4 |

CU: Any MJ use NC: No MJ use |

SZ/AB | >28 days prior to scanning | Optimized VBM in FSL; subcortical volumetry and shape of AMY, HPC, Cd, Pu, Pd, NAc, Th | GMD, shape | TFCE, FDR |

SZ/NC > SZ/AB (GMD): TFG, PHG, VS, R MTG, IC, Pc, R PCG, dlPFC, L postcentral gyrus, lateral occipital cortex, cerebellum Shape analysis: ns |

| Shollenbarger [115] | CS | 33, 12F | 35, 20F |

CU = 21.21 NC = 21.14 |

CU: >25 joints in the past year and >50 lifetime joints. NC: ≤5 joints in the past year and <15 lifetime joints |

C | 7 days; verified based on decreased THC metabolites from time 1 to time 2 | Freesurfer in bilateral dlPFC, mPFC, frontal pole, vmPFC, vlPFC, inferior parietal | Gyrification, surface area | FDR p < .05 for each hemisphere separately |

HC > CU (gyrification): bilateral mPFC, bilateral frontal poles, bilateral vmPFC HC > CU (surface area): L vmPFC, L vlPFC* *p = 0.09 after FDR correction Brain-behavior correlations* ↑ letter-number sequencing performance ↑ gyrification in R mPFC, R vmPFC, R frontal pole * In CU group only |

| C) White matter studies | |||||||||||

| Ref | Design | CU (N, Fn) | NC (N, Fn) | Age (mean) | Inclusion | Status | Abstinence | WM Measure | Analysis Method (ROI vs WB) | MC | Findings |

| Gruber [117] | CS | 25, 7F | 18, 11F |

CU = 23.2 NC = 23.1 |

CU: Minimum of 2,500 MJ uses; use of MJ at least 5/7 previous days; positive utox cannabinoids; DSM-IV criteria for MJ abuse/dependence NC: No history of use |

C | 12 h prior to scan | DTI | ROI | n.r. |

CU > NC (MD): L & R genu of CC NC > CU (FA): L & R genu of CC; L IC Correlations ↑ BIS total attention and motor scores ↓ R genu FA ↑ BIS impulsivity ↓ L genu FA Early MJ onset group: ↑ impulsivity scores on all BIS subscales ↓ FA in L and R genu |

| Becker [118] | LN | 23, 7F | 23, 7F |

CU = 19.5 NC = 19.2 |

CU: Min 5x/week for 1 year; onset before age 17 NC: <5x in past year |

C | 24 h prior to scan | DTI | WB | FWE, input voxelwise height threshold of p < 0.01 |

CU > NC (FA): 2-yr positive change in L anterior CC, L WM adjacent to posterior thalamus CU > NC (RD): 2-yr positive change in R CST/SLF/posterior cingulum NC > CU (FA): 2-yr positive change in R & L SLF, L WM adjacent to SFG, L CST, R ATR, SFOF NC > CU (RD): 2-yr positive change in L CST Partial correlations ↑ total number of hits in past year ↓ change in FA in L CST, L SLF/CC. ↑ max hits frequency in past year ↓ change in R SLF/CST FA. |

| Thayer [90]c** | CS | 201, 52F | 238, 82F |

CU = 16.0 NC = 15.9 |

CU: Cannabis use in last 30 days; min weekly use NC: Cannabis use in last 30 days; <weekly |

C | n.r. | DTI | WB | MCS; TFCE | No sig. associations between WM indices and cannabis use or AUDIT score. |

| Medina [119] | CS | 16, 4F | 16, 5F |

CU = 18.0 NC = 18.0 |

CU: At least 60 times in lifetime NC: < 5 times in lifetime |

AB | At least 28 days prior to the scan | T1 (WM volume) | WB; HPC ROI | n.r. |

No group difference in overall WM volume Correlations w/ depression scores CU: ↓ WM volume ↑ BDI scores All adolescents: ↓ WM volume ↑ depressive symptoms on HAM-D |

| Shollenbarger [120] | CS | 33, 12F | 34, 20F |

CU = 21.2 NC = 21.1 |

CU: >50 lifetime joints & >25 joints in past year NC: 10 lifetime joints & ≤5 joints in the past year |

C | 7 days prior to scan | DTI | ROI | n.r. |

CU > NC (MD): FM, bilateral UF HC > CU (FA): bilateral UF, L ATR (marginally sig) CU × FAAH interaction: C/C cannabis users (n = 24, 13 F; mean age = 21.9) and A carrier controls (n = 43, 19 F; mean age = 20.7) had reduced FA in FM; C/C cannabis users had reduced FA in bilateral ATR Within CU group: ↑ depression symptoms ↓ FA in bilateral ATR & UF ↑ depression symptoms ↑ MD in L ATR. ↑ apathy ↓ FA in bilateral UF. |

| Epstein [121]d | LN | 19, 8F | 29, 16F |

CUD = 16.6 NC = 16.5 |

CUD: CUD; > 50 cannabis exposures by age 17 NC: <5 lifetime exposures to any illicit drug |

T | 0 days (recent use addressed as confound in analysis) | DTI | ROI | None |

HC > CUD (FA): 18-mo change in L ILF Within CUD: ↑ total days of cannabis exposure during interscan interval ↓ L ILF FA. |

| James [114]*** | CS | AOS/CU: 16, 5F |

AOS/NC: 16, 5F F; NC: 28, 10 F |

AOS/CU = 16.4 AOS/NC = 16.2 NC = 16.4 |

CU: >3 days/week for at least 6 months NC: No history of use |

AB | Minimum 28 days | DTI | WB | TFCE, significant clusters p < 0.05; FDR |

AOS/NC > AOS/CU (FA): L SLF, L CC, L posterior limb of InC, bilateral SCD NC > AOS (FA): SLF, ILF, FOF, CST, ATR, and posterior mid-section of CC. |

| Haller [107]* | CS | FEP/CU: 33, 4F (high dose: 15, 2F); low dose: 18, 2F) | FEP/NC: 17, 10F |

FEP/CU = 23.3 (heavy users) and 22.2 (light users) FEP/NC = 23.9 |

CU: Heavy users: min near daily use for min 1 year; light users: >10 lifetime uses, lower frequencies than heavy users; NC: ≤10 lifetime cannabis uses |

FEP/C | n.r. | DTI | Whole brain | TFCE, fully corrected p values <0.05 as significant |

CU vs. HC: No suprathreshold differences in FA, LD, RD, MD. Heavy users vs. light users, heavy users vs non-users, light users vs non-users: no suprathreshold differences in FA, LD, RD, MD. |

| Peters [122] | CS | SZ/CU: 24, 0F | SZ/NC: 11, 0F NC: 21, 0F |

SZ (w/ and w/o CU) = 22.4 NC = 22.6 |

CU: Cannabis use before age 17 NC: ≤ 25 lifetime joints | l | n.r. | DTI | ROI | n.r. | SZ/CU > NC (FA): anterior IC, UF, frontal WM SZ/NC before age 17 did not differ significantly from controls |

| D) Multimodal studies | |||||||||||