Abstract

Head and neck cancer involving the carotid artery is usually unresectable. Such involvement often leads to exposure of the carotid artery and the risk of its blow-out. Carotid covered stent placement may be effective in preventing carotid blow-out; however, thus far, there are few published reports of this procedure. We here present a 65-year-old man who developed neck node recurrence of laryngeal cancer involving the carotid artery, which eventually resulted in exposure of that artery and its impending blow-out. A balloon occlusion test was performed to confirm that the circle of Willis was complete. A covered stent was inserted simultaneously into the affected carotid, enabling us to perform en block resection of the tumor and involved carotid artery as an elective procedure. The patient remained alive and disease-free with no complications or sequelae 10 years after this operation. Despite carotid blow-out being considered imminent, insertion of an endovascular covered stent into the affected carotid artery allowed us to investigate the feasibility of carotid resection while simultaneously preventing that artery’s rupture. Aggressive surgical resection may lead to maintenance of quality-of-life and long-term survival in selected patients.

Keywords: Case report, Head and neck cancer, Neck dissection, Surgical procedure, Carotid artery, Stents

Introduction

Advanced head and neck cancers in which more than 270° of the circumference of the carotid artery is involved are generally considered to be unresectable [1]. In these cases, there is a high risk of carotid artery rupture, so-called carotid blow-out syndrome (CBS), as the disease progresses. In addition to direct tumor invasion, absence of the integument of the carotid arterial wall makes it prone to necrosis, causing CBS. Placement of a protective endovascular covered stent can potentially prevent sudden death from CBS [2–4]. However, there are few published reports of this procedure in such situations. Here, we present a case of recurrent laryngeal cancer involving and exposing the carotid artery, deterring an attempt at radical surgery. This patient was eventually treated successfully by placing an endovascular covered stent in the affected artery, confirming the cerebral circulation was intact by Matas and Allock tests, and then performing en bloc resection of the tumor and carotid artery. At a 10-year follow-up, the patient was alive with no serious complications or sequelae.

Case report

We here report a 65-year-old man whose early left glottic laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (T1aN0) had originally been treated by radiotherapy of 70 Gy. After this treatment, he developed local recurrence and underwent a total laryngectomy. He subsequently developed a refractory pharyngo-cutaneous fistula and underwent multiple surgeries, including construction of a pectoralis major myocutaneous flap and bilateral deltopectoral flaps. A subsequent left cervical nodal recurrence was also managed surgically.

During follow-up, he was found to have a local left upper neck recurrence (Fig. 1a) that was verified by aspiration cytology and imaging studies. Computed tomography (CT) revealed that the recurrence surrounded the entire circumference of the left carotid artery and had formed irregular soft tissue structures (Fig. 1b), suggesting that the tumor had already extended along the carotid adventitia. Findings of positron emission tomography–CT (PET–CT) performed around the same time showed significant fluorodeoxyglucose uptake, as shown in Fig. 1c.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative clinical and radiographic findings. a Neck findings: necrotic adventitia of the carotid wall is visible. b Computed tomography findings: the left carotid artery is surrounded by irregular masses (small arrowheads) and exposed to the exterior (white arrow). c Positron emission tomography with computed tomography findings: marked fluorodeoxyglucose accumulation completely surrounds the carotid artery

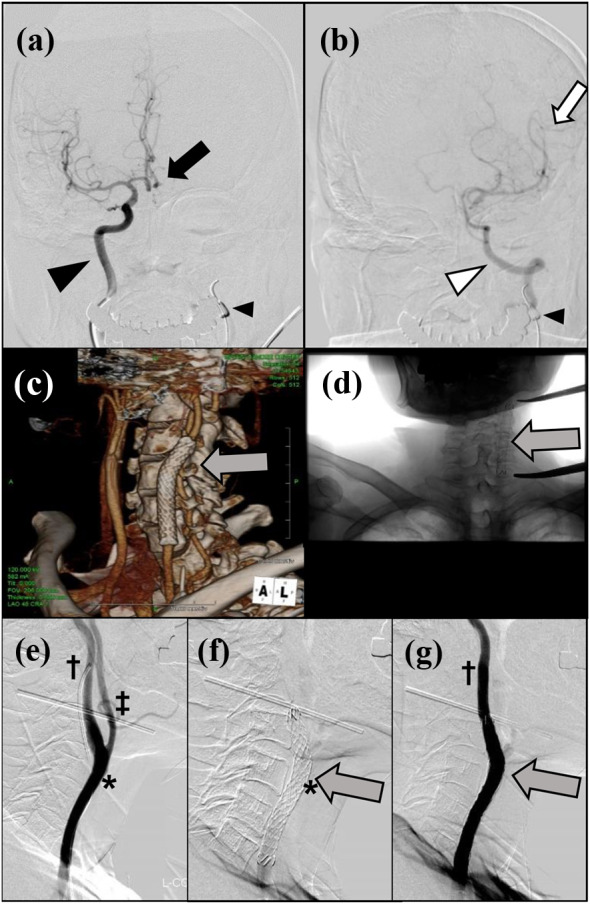

Given that CBS was considered imminent, we decided to attempt to prevent this by inserting an endovascular covered stent into the carotid artery. We considered that simultaneous surgical management of the recurrent tumor together with the carotid artery would then be a valid option. To assess the likely sequelae of sacrificing the carotid artery, we conducted both Matas and an Allcock tests to assess the cerebral circulation. A balloon catheter was used for internal carotid artery occlusion (Hyperform™, 7 × 7 mm, Medtronik, Carlsbad, CA, USA). No symptoms occurred during these tests. The left anterior cerebral artery was visualized via the right internal carotid artery (Fig. 2a) and the left middle cerebral artery via the left vertebral artery (Fig. 2b), the findings indicating that the circle of Willis was complete. An endovascular neurosurgeon then placed a covered stent (Niti-S Biliary Covered Stent, 8 mm × 6 cm; Century Medical, Shinagawa, Japan) endovascularly into the carotid artery without any complications (Fig. 2c–g). After determining the affected area of the carotid artery from the surface, a stent was inserted to reinforce the relevant area. The cranial side of the stent was located in the internal carotid artery, approximately 25 mm from the bifurcation of the common carotid artery (Fig. 2e, f). Angiography performed after expansion of the stent showed that adequate patency of the common and internal carotid arteries had been achieved and there was no leakage into the external carotid artery (Fig. 2g). Immediately prior to the balloon occlusion test and stent insertion, anticoagulation therapy was started. This comprised 5000 units of heparin intravenously, oral aspirin 200 mg, cilostazol 200 mg, and clopidogrel 300 mg as loading doses. From the day after stenting until 14 days before the scheduled surgery, the patient continued to receive cilostazol 100 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg orally daily.

Fig. 2.

Preoperative investigations. a Matas test: balloon occlusion of the left carotid artery (small arrowhead). The black arrowhead indicates the right carotid artery and the black arrow the left anterior cerebral artery visualized via the right internal carotid artery. b Alcock test: balloon occlusion of the left carotid artery (small arrowhead). The white arrowhead indicates the left vertebral artery and the white arrow the left middle cerebral artery visualized via the left vertebral artery. c Three-dimensional reconstructed CT image and d plain radiographic findings. The gray arrow indicates the endovascular covered stent. e Contrast image of the left common carotid artery just before insertion of a covered stent. *, assumed area of carotid artery involvement; †, internal and ‡, external carotid arteries. f A covered stent was inserted from the left common carotid artery to the left internal carotid artery (gray arrow). The distal end of the stent is approximately 25 mm cranial to the carotid bifurcation. g Carotid angiographic findings after stenting. The internal carotid artery is well visualized, whereas the external carotid artery is not

Following the patient’s temporary discharge, elective excision of the tumor accompanied by resection of the left common, internal, and external carotid arteries, vagus nerve, and skin was performed (Fig. 3a–e). The skin was reconstructed using a local flap from the back (Fig. 3f, g). The total time for resection was 2 h 40 min and blood loss 50 mL, the overall total operation time being 4 h 5 min with total blood loss 90 mL. Partial necrosis of the tip of the local flap occurred. This improved with local treatment and the patient was discharged home 3 weeks postoperatively. Histopathological examination of the operative specimen revealed a tumor with scirrhous invasion along the carotid adventitia (Fig. 3h).

Fig. 3.

Neck dissection with carotid artery resection. a Skin incision line. The arrowhead indicates the exposed wall of the carotid artery. b, c Intraoperative findings during carotid resection. The black arrowhead indicates the sacrificed vagal nerve, the white arrowhead the preserved hypoglosus nerve, and the black arrow the inferior end of endovascular covered stent. d, e Excised specimen. The black arrowhead indicates the exposed intravascular covered stents and carotid wall, the white arrowhead the intra-carotid covered stent, and the white arrow the perforated carotid wall. f, g Skin reconstruction. A local flap from the back was employed. h Photomicrograph of an Elastica-Masson stained section showing scirrhous tumor invasion (arrowheads) of the carotid adventitia (white arrow). Scale bar: 500 μm

The patient later developed other nodal metastases in the lateral posterior region and on the contralateral side; however, these were controlled by surgical resection alone or surgery plus postoperative chemo-radiotherapy confined to a hemi-neck field. The patient was alive without recurrence 11 years after carotid resection and 10 years after the final treatment.

Discussion

One review [4] reported an approximately 50% postoperative mortality rate after carotid resection for CBS. In another report of 77 cases of CBS, only 6.5% of patients survived disease-free for over 5 years without sequelae [5]. The prognosis of HNC with carotid artery invasion is extremely poor, the 5-year survival rates of patients who have undergone aggressive radical surgeries involving carotid resection followed by re-vascularization being only 12.9% [6]. Despite the CBS threatened by ongoing carotid invasion by the tumor, and hence our patient’s poor prognosis, a long-term survival of more than 10 years was achieved with an aggressive therapeutic approach.

The postoperative mortality rate after carotid resection is very high, as mentioned above. With emergency surgery, the risks of both stroke and postoperative mortality are known to be even higher [7]. Therefore, this procedure should only be performed in an elective setting. Protective endovascular stenting can reportedly be effective in preventing CBS in patients with advanced HNC with carotid invasion [2–4], as evidenced by the present case. In addition, carotid balloon occlusion tests can be performed to determine the state of Willis’ circle and any collateral flow, thus enabling evaluation of the feasibility of sacrificing the carotid artery. Balloon occlusion tests may also help in predicting the likelihood of life-threatening ischemia occurring in the event of an emergency condition, such as occlusion of a covered stent or development of CBS requiring urgent embolization of the internal carotid artery. In the present case, these procedures enabled us to perform en bloc carotid resection electively without an intervening CBS or cerebral morbidity or mortality from any other cause.

Five case series in which carotid artery invasion by HNC was resected after carotid artery stenting have been published [8]. The authors removed the wall of the involved carotid artery while preserving the covered stent. It is very important to identify any tumor invasion proximal or distal to the carotid stenting site because of the risk of CBS after stenting if an involved segment is left in situ [4]. In the present patient, the carotid artery was surrounded by a tumor with irregular margins, the full extent of which was very difficult to determine by imaging. We, therefore, concluded that both resection of the carotid artery and removal of the endovascular stent were necessary to ensure safe margins. Furthermore, if the arterial wall had been excised and the stent left in situ, there would have been a strong possibility of necrosis of the carotid artery developing on the proximal and/or distal sides of the stent, this risk being inferred on the basis of our patient’s previous refractory fistula. Suarez et al. have reported that carotid artery ligation, rather than stenting, is necessary in cases of impending CBS with fistula formation [4]. The carotid should be resected without preserving the stent when the extent of carotid artery involvement by the tumor is unclear and the risk of rupture, therefore, indeterminate.

In conclusion, in patients with recurrent HNC involving the carotid artery, endovascular placement of covered stents can prevent CBS and balloon occlusion tests can enable evaluation of the feasibility of carotid resection. Implementation of these procedures may broaden treatment options in patients without other metastasis. Aggressive surgical resection may lead to maintenance of quality-of-life and long-term survival in selected patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the help of Yasushi Matsumoto M.D., Department of Neuroendovascular Therapy, Kohnan Hospital, Sendai, Miyagi, Japan in performing carotid covered stenting and a balloon occlusion test in this patient.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s family for publication of this case report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Takayuki Imai, Email: imai-ta479@miyagi-pho.jp.

Yukinori Asada, Email: asada7@yahoo.co.jp.

Ko Matsumoto, Email: matsumoto510@gmail.com.

Ikuro Sato, Email: sato-ik510@miyagi-pho.jp.

Takahiro Goto, Email: goto-ta608@miyagi-pho.jp.

Kazuto Matsuura, Email: kmatsuur@east.ncc.go.jp.

References

- 1.Yousem DM, Hatabu H, Hurst RW et al (1995) Carotid artery invasion by head and neck masses: prediction with MR imaging. Radiology 195:715–720. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7754000/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Gaynor BG, Haussen DC, Ambekar S et al (2015) Covered stents for the prevention and treatment of carotid blowout syndrome. Neurosurgery 77:164–167. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25790070/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Simizu Y (2021) Endovascular Treatment of carotid blowout syndrome. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 30:105818. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28236928/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Suarez C, Fernandez-Alvarez V, Hamoir M et al (2018) Carotid blowout syndrome: modern trends in management. Cancer Manag Res 10:5617–5628. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30519108/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Razack MS, Sako K (1982) Carotid artery hemorrhage and ligation in head and neck cancer. J Surg Oncol 19:189–192. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7078171/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Nishinari K, Krutman M, Valentim LA et al (2014) Late surgical outcomes of carotid resection and saphenous vein graft revascularization in patients with advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Vasc Surg 28:1878–1884. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25106104/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Moore OS, Karlan M, Sigler L (1969) Factors influencing the safety of carotid ligation. Am J Surg 118:666–668. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5347083/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Markiewicz MR, Pirgousis P, Bryant C et al (2017) Preoperative protective endovascular covered stent placement followed by surgery for management of the cervical common and internal carotid arteries with tumor encasement. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 78:52–58. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28180043/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]