Abstract

Objectives

To assess if a multi-strategy intervention effectively increased weekly minutes of structured physical activity (PA) implemented by classroom teachers at 12 months and 18 months.

Methods

A cluster randomised controlled trial with 61 primary schools in New South Wales Australia. The 12-month multi-strategy intervention included; centralised technical assistance, ongoing consultation, principal’s mandated change, identifying and preparing school champions, development of implementation plans, educational outreach visits and provision of educational materials. Control schools received usual support (guidelines for policy development via education department website and telephone support). Weekly minutes of structured PA implemented by classroom teachers (primary outcome) was measured via teacher completion of a daily log-book at baseline (October–December 2017), 12-month (October–December 2018) and 18-month (April–June 2019). Data were analysed using linear mixed effects regression models.

Results

Overall, 400 class teachers at baseline, 403 at 12 months follow-up and 391 at 18 months follow-up provided valid primary outcome data. From baseline to 12-month follow-up, teachers at intervention schools recorded a greater increase in weekly minutes of PA implemented than teachers assigned to the control schools by approximately 44.2 min (95% CI 32.8 to 55.7; p<0.001) which remained at 18 months, however, the effect size was smaller at 27.1 min (95% CI 15.5 to 38.6; p≤0.001).

Conclusion

A multi-strategy intervention increased mandatory PA policy implementation. Some, but not all of this improvement was maintained after implementation support concluded. Further research should assess the impact of scale-up strategies on the sustainability of PA policy implementation over longer time periods.

Trial registration number

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12617001265369).

Keywords: school, physical activity, children, implementation, intervention effectiveness

Background

To improve child physical activity (PA) levels, the WHO recommended schools adopt policies that support children’s daily PA.1 Interventions that increase opportunities for regular PA during the school day effectively increased children’s moderate-vigorous physical activity (MVPA).2 In addition to teaching physical education (PE), a number of countries including Australia,3 China,4 Denmark,5 England6 and several Canadian provinces7 and US states8 9 have policies or guidelines regarding the minimum amount of time that primary schools schedule structured PA each week. Despite their existence, most schools fail to implement such policies.9–11 For example, in a study of Canadian elementary school teachers, only 43% implemented the mandatory 30 min/day PA policy that required organised in-class opportunities for children to be active.12 An Australian study (2017) found that only 24% were meeting the recommended 150 min of weekly PA.13 To enhance the potential to achieve broad public health benefits, school PA policies and strategies are needed to assist schools overcome barriers to their implementation and scale-up. We also need to identify whether schools’ continue to implement policies (implementation maintenance) once support is removed, as this encourages implementation in the first place and maximises benefits at scale-up.

There is limited research of strategies that facilitate schools’ implementation of health innovations.14 A Cochrane review14 identified only one controlled trial in primary schools that aimed to implement PA guidelines.15 This quasi-experimental study in seven US schools provided: on-site training, ongoing technical assistance, modelling, audit and feedback, resources and coalition building support.15 Improvements in the implementation of PE congruent with national guidelines were found, but effects were not sustained at 2 years. In 2017, we undertook a pilot cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) in 12 Catholic primary schools. We aimed to determine the efficacy of a 9-month strategy to improve teachers’ implementation of the New South Wales (NSW) Sport and Physical Activity Policy, which requires schools to schedule 150 min of moderate, with some vigorous, PA per week for students in kindergarten to grade 10.3 The 150 min may include: PE (which in Australia is typically taught by generalist classroom teachers), sport and other structured activities such as energisers16 (ie, 3–5 min structured classroom PA breaks) or active lessons (eg, integrating PA into maths lessons).17 Intervention schools received: executive support, training for in-school champions, ongoing support, tools and resources.13 Immediately following the intervention, teachers in intervention schools scheduled significantly more minutes of PA per week than teachers in control schools (36.6 min, 95% CI 2.7 to 70.5, p=0.04).13 The extent to which these effects were maintained following cessation of implementation support or factors important for interpreting implementation findings (eg, a description of implementation context and processes) were not assessed.

The primary objective of this study was to assess whether a multi-strategy intervention effectively increased weekly minutes of structured PA implemented by classroom teachers at 12 months and 18 months. Our secondary objective was to describe the types of activities teachers implemented to achieve PA policy adherence (eg, PE, energisers, sport and integrated lessons).

Methods

A trial protocol has been published.18 This paper reports primary trial outcomes only. The study adheres to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials19 and Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (STARI)20 guidelines.

Study design and setting

An RCT was undertaken in 62 primary schools (31 per group), in the Hunter New England (HNE) region, of NSW Australia. The HNE is geographically large (130 000 km2) with a demographically and socioeconomically diverse population residing in metropolitan, urban and suburban areas, regional centres and rural and isolated remote communities.21 There are approximately 427 primary schools in this region of which 324 (76%) are government and 65 (15%) are Catholic.

Participants, recruitment, randomisation and blinding

Government and Catholic schools in the HNE were eligible if they were not participating in another PA trial and only enrolled primary school students who did not require specialist care. Following baseline data collection, schools were randomised to intervention or control by an independent statistician using a computer-based random number generator. Allocation was stratified by the schools’ geographic location (rural vs urban) and type (government, Catholic).7 Data collectors were blinded to group allocation. All surveys were deidentified prior to data entry. Due to the nature of the intervention, school and programme staff were not blinded.

Multi-strategy implementation intervention

The protocol includes a detailed description of the development of the intervention.18 The intervention was designed, using Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW)22 and Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF).23 Following extensive formative research which included (i) literature reviews; (ii) interviews with 76 primary school teachers using an adapted TDF survey and (iii) observations of teachers’ delivery of PE, sport and the school environment, the recommended process described by Michie et al 23 was undertaken to map the identified barriers to the BCW and TDF. In consultation with an advisory group, strategies were purposefully selected to address known barriers to policy implementation.11 The intervention, described in table 1, was delivered over one school year (ie, four school terms) November 2017–November 2018.

Table 1.

Description of multi-strategy implementation intervention* and fidelity to and satisfaction with the intervention

| Implementation strategy (timeframe strategy was delivered) |

Implementation strategy description | Barrier addressed | BCW and (TDF domain) | Process measures | |

| % of schools that received and or engaged with the implementation strategy | % very satisfied with (N=35 school champions; N=158 teachers)† |

||||

| Centralise technical assistance and provide ongoing consultation (Terms 1–Term 4) |

Project officers (a PE teacher and health promotion practitioner) provided technical assistance to schools throughout the study period, to support policy implementation by working directly with schools and school champions to collaborate to overcome barriers and provide expertise support and resources. Project officers provided ongoing consultation to in-school champions via telephone, email or if needed face-to face to support implementing the intervention. The focus of these meetings was to help school champions brainstorm solutions to barriers as they arose, review progress teachers were making with the school’s implementation plan and, if necessary, modify and reset goals. |

Teachers knowledge, ability or competence Lack of time Perceived priority of the policy in the schools |

Psychological capability (beliefs about capabilities; knowledge) Opportunity—social (environmental context and resources) Motivation—reflective (goals) |

100% of schools were allocated a project officer and all received ongoing consultation | 89% of school champions were very satisfied with the ongoing consultation support they received from the project officer |

| Identify and prepare champions (Term 1) |

Each school nominated up to three in-school champions (existing teachers at the school) who drove the implementation of the intervention in their school and, with support from project officers, overcome indifference/ resistance that the intervention provoked in the school. The number of school champions was dependent on the size of the school with 3 schools nominating 1 champion, 13 nominating 2 champions and 14 schools nominating 3 champions). To prepare in-school champions for their role they completed a 1 day (5 hours) face-to-face training workshop run by project officers which included; education about the policy, instruction and demonstration of energisers and PE lessons, time to begin action planning including identification of barriers/ facilitators, to implementation and possible solutions to overcome these via a ‘if-then-what’ plan. The inclusion of this contingency planning was an adaptation from the pilot study where it had been identified that if teachers had physical activity scheduled but unexpected events occurred in the school, for example, special assemblies or wet weather they did not adapt their schedule for the day to include the physical activity elsewhere. The training was accredited by the state educational authority and provides time towards teachers continuing professional development hours. | Lack of time in the curriculum Teachers knowledge, ability or competence |

Opportunity—social (environmental context and resources) Psychological and physical capability (beliefs about capabilities) |

100% schools had at least 1 nominated school champion 97% of school champions attended the training workshop |

100% of school champions were very satisfied with the training they received 73% of teachers were very satisfied with the support they received from their school champion |

| Conduct educational outreach visits. (Term 2–4) |

Project officers met with all teachers (face-to-face) as a group in each school for 1–2 hours where they:

|

Teachers knowledge, ability or competence | Psychological and physical capability (beliefs about capabilities) |

97% of schools accepted an educational outreach visit 70%–100% of staff in these schools attended the educational outreach visit |

100% of school champions and 81% of teachers were very satisfied with the educational outreach visit |

| Mandate change (Term 1) |

To gain school executives ‘‘buy-in’ for the policy so that they would mandate change to their staff, project officers met face to face with principals and school executives to communicate the importance and benefits of policy implementation. The school executive was asked to demonstrate support for the implementation of the policy through the development of a ‘Sport and Physical Activity Procedures document’ (as required by the policy) and to mandate change by communicating to staff (eg, via newsletters, assemblies and staff meetings) that the implementation of the policy was a priority and that there was an expectation for it to be implemented by all staff. | Support from school boards Physical activity considered a lower priority than other subjects |

Opportunity—social (social influences) Motivation—reflective (goals) |

100% of schools developed a school policy 81% of principals mandated change for policy implementation during the educational outreach visit |

Not assessed |

| Develop a formal implementation blueprint. (Term 1) |

School champions were supported to develop a plan for the implementation of the policy in their school. The plan identified what the school was aiming to achieve, the strategies to do so and by when, the resources available or required to implement the plan. The plan was segmented into school terms to allow school champions to break up some of the more complex policy requirements into achievable tasks. | Perceived priority of the policy in the schools | Motivation—reflective (goals) |

100% of schools developed a formal implementation blueprint | 100% of school champions were satisfied with the support they received to develop their implementation blueprint |

| Develop and distribute educational materials (Term 1–4) |

In-school champions received an ‘intervention manual’ which included policy and timetable templates, exemplar physical activity timetables and physical education curriculum schedules. Classroom teachers received various educational materials including practical games and strategies for increasing physical activity in lessons. These materials were available in print and via an online portal. The portal also contained professional learning videos for all teachers (including school champions) which reinforced the information they received via face-to-face training. School champions were asked to view the videos and to organise a time for their staff to watch them during a staff meeting or to provide access for staff to watch individually. | Teachers knowledge, ability or competence | Psychological capability (beliefs about capabilities; knowledge) | 100% of schools were provided the intervention manual 78% of school champions viewed the professional learning videos on the online portal 59% of school champions organised staff viewing of the professional learning videos at staff meetings 68% of school champions used the online portal to access educational resources |

95% of school champions and 96% of teachers were very satisfied with the professional learning videos 75% of school champions and 68% of teaches were very satisfied with the online portal resources |

| Capture and share local knowledge (Term 2–4) |

Project officers developed ‘case studies’ from other intervention schools on how school champions and teachers made ‘something work’ in their setting. This was used during project officers ongoing consultation meetings with in-school champions and included on the online portal as an ‘infocus school’. | Teachers knowledge, ability or competence Lack of time in the curriculum |

Opportunity—social (social influences) Motivation—reflective (belief about consequences) |

100% of case studies were provided to schools | Not assessed |

| Change physical structure and equipment (Term 1) |

Schools were provided with one basic physical activity equipment pack which included bean bags, balls, hoops, etc which school champions were shown how to use through classroom energisers and integrated lessons. School champions were encouraged to develop ‘physical activity packs’ for all teachers to keep in each classroom which included a class set of similar equipment from the schools existing sports equipment enabling teachers to implement PA more easily. | Availability of equipment | Opportunity— physical (environmental context and resources) |

68% of schools accepted an equipment pack 64% of school champions organised purchasing of equipment packs for all classrooms |

84% of school champions and teachers were very satisfied with the equipment packs |

*Please see the protocol paper for more detailed explanation of the hypothesised mechanisms of action via the BCW and TDF.

†NB proportions are those who completed the survey, that is, 35 school champions and 158 teachers.

BCW, Behaviour Change Wheel; PA, physical activity; PE, physical education; TDF, Theoretical Domains Framework.

Control group

Control schools had access to ‘usual’ implementation support from the NSW government which included: access to information and resources such as example policies and templates via a website as well as telephone support if requested by the school. The delivery of the multi-strategy intervention was under the control of the research team and not provided to control schools during the study period.

Data collection and measures

Baseline data (0 months) were collected between October 2017 and February 2018 and final data collection (12 months post baseline) were collected October–November 2018. Maintenance data were collected approximately 18 months post baseline (April–June 2019) that is, 6 months with no active implementation support.

Primary trial outcome: weekly minutes of structured PA implemented by classroom teachers at 12 and 18 months

As per the pilot study,13 the mean weekly minutes of PA implemented by teachers was measured via a daily log-book that teachers completed during a 1-week period at baseline, 12 and 18 months. The log-book included the time and type (ie, PE, sport, energisers or active lessons) of PA implemented. As we aimed to assess weekly PA implementation, teacher data were valid if they provided responses across the entire school week (ie, 5 days) and did not exceed 250 min. Values above 250 min were deemed by the project partners unlikely given Department of Education’s (DoE’s) guidance of minimum time required for scheduling other subjects.24 Only teachers with valid data were included in the analysis sample. Teacher log-books are successfully used in classroom-based obesity prevention interventions13 25 26 with high response rates (ie, >80%)25 and established reliability.8 26

Secondary outcome: weekly minutes of PE, energisers, sport and integrated lessons implemented by classroom teachers at 12 and 18 months

The mean weekly minutes of PE, sport, energisers and active lessons implemented were also collected from teacher log-books (as per the primary outcome).

School and participant characteristics

Detail regarding school type, postcode and school size was obtained from websites. Principals and teachers were invited to complete a paper survey which asked their; sex, age (years), years teaching experience, grade level taught, employment status and if they were a specialist PE teacher.

Process measures

To contextualise the study findings measures, recommended by Proctor et al,27 were assessed within intervention schools at follow-up.

Acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of the policy

Validated self-report measures28 were included in the teacher’s pen-and-paper surveys. They were asked to report (using a five-point Likert scale from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree), their perceptions as to whether the policy was: (i) welcomed, appealing, liked and met their approval (Acceptability of Intervention Measure); (ii) a good fit, suitable, applicable and compatible within the context of their school (Intervention Appropriateness Measure) and (iii) possible, easy, do-able and implementable (Feasibility of Intervention Measure). A total score for each domain was calculated by averaging the item responses.29

Fidelity to and satisfaction with the multi-strategy implementation intervention

Project records as well as postintervention surveys completed by school champions were used to determine the proportion of schools that received and engaged with each of the implementation strategies. School champions and teachers were asked how satisfied they were with each of the implementation strategies.

Sample size

The average primary school had 13 classrooms. Using a conservative 70% response rate estimate and assuming 20% loss-to-follow-up, a sample of 31 schools per group would provide a sample of approximately 450 classes (225 per group) at follow-up. Based on pilot data an SD of 45 min, and a conservative Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) of 0.2, the sample was sufficient to detect an absolute difference of 18.0 min of weekly minutes of PA, with 80% power and alpha 0.05.

Statistical analysis

Analyses of the study outcomes were performed under an intention to treat framework, with teacher responses analysed according to the experimental group their school was originally randomised to. Class (nested within a school) was the unit of analysis. Differences between the intervention and control group with regards to changes in the primary outcome and types of PA implemented (ie, PE, energisers, sport and integrated lessons) from baseline to each of the follow-up time-points, were assessed using linear mixed effects regression models. Linear mixed models estimate and account for the correlation of data within clusters (ie, schools) through the inclusion of random effects, thus accounting for the lack of independence of observations from cluster trials such as this one. Linear mixed models also use all available data, regardless of missing outcome data, assuming data are missing at random. A separate model was conducted for each outcome, and included fixed effects for treatment group (intervention vs control), time (baseline, 12-month and 18-month follow-up), a time by group interaction term and variables prognostic of the outcome (school type, geographic and socioeconomic location of the school).7 The model included a random intercept for school to allow for the clustered design, a random intercept for teacher (nested within school) to account for repeated measurement of some teachers, as well as a random slope. Descriptive statistics described the process measures reported by the intervention group.

Partner and end-user involvement

The DoE and Catholic Schools Office (CSO) (authors JB and BD) identified the research question. The DoE were partner investigators on the grant. The intervention and study materials were designed following extensive formative research and consultation with principals, teachers, DoE and CSO representatives. Participant burden was assessed during school ethical approvals. An Advisory Group, which included DoE and CSO, oversaw all aspects of the study. Data have been shared with DoE and CSO and will be presented at their principal and teacher forums.

Deviations from registered protocol

None.

Results

School and participant characteristics

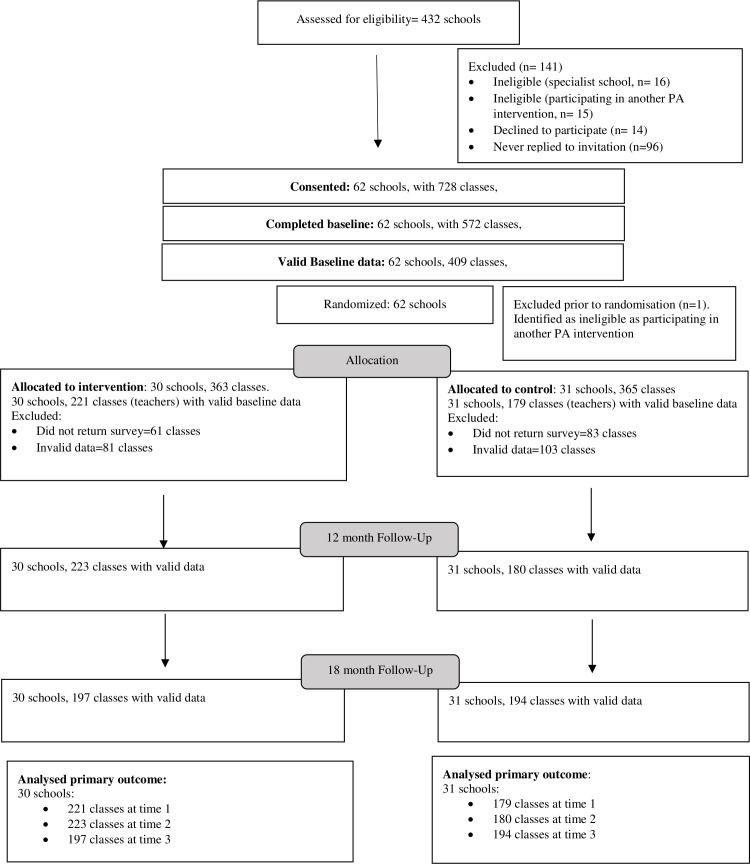

Figure 1 presents a flowchart of the eligible and participating schools in the study. Four hundred and thirty-two schools were assessed for eligibility, with 62 schools meeting inclusion criteria and consenting to participate. One school was excluded prior to randomisation because it was participating in another PA intervention. There were no differences in the baseline characteristics of schools (table 2), with 42% of schools from intervention and 39% of control groups from inner/outer regional areas and 58% from major cities (table 2). Overall, 44% of schools from major city areas were classified as most disadvantaged, compared with 88% of schools from inner/outer regional areas. School size (data not shown) ranged from 40 to 900 students, with the mean size slightly higher in the intervention group compared with the control group (300.3 vs 261.6, respectively). Of the remaining 61 schools, 3 provided invalid data (ie, no surveys with 5 days of data ≤250 min), leaving a total of 58 schools contributing valid data at 12-month and 18-month follow-up, from a total of 403 and 391 teachers, respectively. Across all three time points loss of data due to reporting of PA above 250 min represented a 4% loss of data. The characteristics of all teachers providing valid data across each of the three time points was similar across both intervention and control groups (see table 3).

Figure 1.

Time schedule of participant enrolment, data collection and intervention delivery. PA, physical activity.

Table 2.

Baseline school characteristics by experimental group

| Characteristics | Control N=31 |

Intervention N=31 |

| School type | ||

| Catholic | 5 (16%) | 5 (16%) |

| Government | 26 (84%) | 26 (84%) |

| Size | ||

| Mean (SD) | 261.6 (101.2) | 300.3 (182.6) |

| SEIFA (based on school address) | ||

| Most disadvantaged | 19 (61%) | 20 (64%) |

| Least disadvantaged | 12 (39%) | 11 (36%) |

| Remoteness (based on school address) | ||

| Inner regional Australia | 12 (39%) | 13 (42%) |

| Major cities of Australia | 18 (58%) | 18 (58%) |

| Outer regional Australia | 1 (3%) | 0 |

SEIFA, socio-economic indexes for areas.

Table 3.

Teacher characteristics by experimental group

| Characteristic | Control | Intervention | ||||

| Baseline | 12 months | 18 months | Baseline | 12 months | 18 months | |

| School type teaching at | N=179 | N=180 | N=194 | N=221 | N=223 | N=197 |

| Catholic/independent | 62 (35%) | 72 (40%) | 58 (30%) | 66 (30%) | 67 (30%) | 57 (29%) |

| Government | 117 (65%) | 108 (60%) | 135 (70%) | 155 (70%) | 156 (70%) | 140 (71%) |

| Age of class teacher | N=173 | N=158 | N=171 | N=202 | N=197 | N=152 |

| Mean (SD) | 38.0 (11.1) | 38.3 (11) | 39.3 (11) | 40.0 (11) | 39.8 (11) | 40.1 (11) |

| Sex | N=174 | N=175 | N=188 | N=210 | N=219 | N=176 |

| Female—n (%) | 148 (85%) | 149 (85%) | 160 (85%) | 183 (87%) | 189 (86%) | 150 (85%) |

| Job share | N=173 | N=168 | N=184** | N=209 | N=211 | N=165** |

| Yes—n (%) | 53 (301%) | 48 (29%) | 54 (29%) | 48 (22%) | 49 (23%) | 30 (18%) |

| Employment status | N=172 | N=170 | N=185 | N=209 | N=209 | N=167 |

| Permanent full-time | 104 (60%) | 88 (52%) | 101 (55%) | 113 (54%) | 111 (53%) | 99 (59%) |

| Temporary full-time | 50 (29%) | 62 (36%) | 60 (32%) | 71 (34%) | 67 (32%) | 48 (29%) |

| Permanent part-time | 7 (4%) | 11 (6%) | 14 (8%) | 14 (7%) | 15 (7%) | 14 (8%) |

| Temporary part-time | 6 (3%) | 5 (3%) | 10 (5%) | 8 (4%) | 13 (6%) | 6 (4%) |

| Casual | 5 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Number of years teaching | N=172 | N=167 | N=184 | N=209 | N=207 | N=165 |

| Mean (SD) | 13.0 (11) | 12.5 (10) | 13.6 (10) | 14.6 (10) | 13.8 (10) | 14.0 (10) |

| Specialist PDHPE teacher | N=173 | N=168 | N=182 | N=211 | N=210 | N=167 |

| Yes—n (%) | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 6 (3%) | 3 (2%) |

**P<0.01.

PDHPE, personal development, health and physical education.

Primary outcome: weekly minutes of structured PA implemented by classroom teachers at 12 months and 18 months

At 12-month intervention teachers increased their overall implementation of PA per week by an average of 44.2 min (95% CI 32.8 to 55.7; p<0.001) more than the control group (table 4). This was maintained at 18 months, with the intervention group increasing their implementation from baseline to 18 months by an average of 27.1 min (95% CI 15.5 to 38.6; p≤0.001) more than the control. The difference in the change from 12-month to 18-month follow-up between the two experimental groups was statistically significant (−17.2 min (95% CI –28.8 to –5.64; p=0.004)), with the intervention group recording a within group change of - 1.3 min (95% CI −9.3 to 6.6; p=0.74), compared with the usual care group which recorded an increase of 15.9 min (95% CI 7.4 to 24.3; p<0.001).

Table 4.

Changes in weekly minutes of physical activity implemented from baseline to 12-month and 18-month follow-up

| Control | Intervention | Between group differences change from baseline to 12 months | Between group differences change from baseline to 18 months | ICC | |||||||

| Baseline mean (SD) or % (n) | 12-month follow-up mean (SD) or % (n) | 18-month follow-up mean (SD) or % (n) | Baseline mean (SD) or % (n) | 12-month follow-up mean (SD) or % (n) | 18-month follow-up mean (SD) or % (n) | Adjusted mean diff. (95% CI) or OR (95% CI) |

P value | Adjusted Mean diff. (95% CI) or OR (95% CI) |

P value | ||

| N=179 | N=180 | N=194 | N=221 | N=223 | N=197 | ||||||

| Total weekly minutes of all PA implemented | 110.2 (SD=53.6) | 95.7 (SD=42.4) | 116.9 (SD=44.3) | 115.6 (SD=50.9) | 148.5 (SD=44.1) | 146.7 (SD=40.3) | 44.2 (32.8 to 55.7) |

<0.001 | 27.1 (15.5 to 38.6) |

<0.001 | 0.07 |

| % meeting the 150 min PA policy | 31.3 (n=56) |

17.2 (n=31) |

29.9 (n=58) |

31.7 (n=70) |

61.9 (n=138) |

59.4 (n=117) |

OR: 7.56 (3.88 to 14.7) |

<0.001 | OR: 3.62 (1.93 to 6.79) |

<0.001 | 0.07 |

| Changes in the weekly minutes for the different types of PA implemented | |||||||||||

| Total weekly minutes of PE | 42.2 (SD=41.3) | 29.5 (SD=34.2) | 44.9 (SD=32.5) | 47.6 (SD=40.0) | 48.4 (SD=34.0) | 50.8 (SD=31.3) | 10.4 (1.89 to 18.8) |

0.008 | 2.43 (−6.10 to 11.0) |

0.57 | 0.15 |

| Total weekly minutes of energisers | 17.0 (SD=26.2) | 10.8 (SD=19.7) | 13.6 (SD=22.4) | 18.1 (SD=23.9) | 35.4 (SD=24.4) | 39.0 (SD=28.3) | 23.1 (16.5 to 29.6) |

<0.001 | 23.4 (16.9 to 30.0) |

<0.001 | 0.11 |

| Total weekly minutes of sport | 43.4 (SD=26.0) | 53.4 (SD=21.7) | 51.8 (SD=27.5) | 44.1 (SD=33.3) | 57.2 (SD=26.7) | 50.9 (SD=26.7) | 3.81 (−3.13 to 10.8) |

0.28 | 0.39 (−6.60 to 7.38) |

0.91 | 0.10 |

| Total weekly minutes of integrated lessons | 7.60 (SD=17.0) | 1.89 (SD=7.15) | 6.65 (SD=14.7) | 5.86 (SD=14.6) | 7.48 (SD=13.1) | 5.98 (SD=13.4) | 6.96 (3.15 to 10.8) |

<0.001 | 1.27 (−2.57 to 5.10) |

0.51 | 0.03 |

Boldface indicates statistical significance (P < .05).

ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; PA, physical activity; PE, physical education.

The proportion of teachers in the intervention group meeting the mandated 150 min of PA per week was 61.9% (n=138) at 12 months and 59.4% (n=117) at 18 months compared with the control group which had 17.2% (n=31) and 29.9% (n=58) at 12 months and 18 months, respectively. The difference in the change in proportion of teachers scheduling 150 min of PA per week between intervention and control was significantly different from baseline to 12 months (OR: 7.56; 95% CI 3.88 to 14.7, p<0.001) and from baseline to 18 months (OR: 3.62; 95% CI 1.93 to 6.79, p≤0.001).

Secondary outcome: types of activities teachers implemented to achieve PA policy adherence (eg, PE, energisers, sport and integrated lessons)

At 12 months teachers in the intervention group had a significantly greater increase from baseline, in implementation of energisers (23.1 min; 95% CI, 16.5 to 29.6; p<0.001), PE (10.4 min; 95% CI 1.89 to 18.8; p=0.017) and integrated lessons (6.96 min; 95% CI 3.15 to 10.8; p≤0.001) (table 4). There were no differences between groups in the change in implementation of sport from baseline to 12 months. The significant between group difference was only maintained for energisers at 18 months, with the intervention group increasing their implementation from baseline, by an average of 23.4 min (95% CI 16.9 to 30.0; p≤0.001) more than the control.

Process measures

Perceived acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of the policy

Teacher’s mean scores (out of a total score of 5) for the perceived acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of the policy were; acceptability (mean 3.81, SD 0.70), appropriateness (mean 3.81, SD 0.67) and feasibility (mean 3.59, SD 0.82) indicating an overall moderate approval29 of the PA policy.

Fidelity to and satisfaction with the multi-strategy implementation intervention

Table 1 outlines the proportion of schools that received, engaged with and were satisfied with each of the implementation strategies. Most strategies were delivered to all schools except one school did not attend the school champion training workshop, one school did not attend the educational outreach meeting, and 10 schools advised that their school had adequate equipment and declined the equipment packs. Overall school champions and teachers were very satisfied with the multi-strategy implementation intervention with the proportion of school personnel very satisfied ranging from 68% to 100%.

Discussion

Why this study is important?

This is one of few implementation trials internationally to examine the impact of strategies to improve the implementation of school PA policies and is the largest to do so. The study used a comprehensive evaluation framework to report the effects of an implementation strategy that was developed using a theoretically guided process, undertaken in partnership with end-users and drew on considerable formative research. The study found that the strategy was effective in improving initial policy implementation, and that such improvements were maintained in part, at longer term follow-up. The findings have important implications for policy makers and practitioners interested in improving student PA in this setting.

How effective was the intervention?

The size of the intervention effect (47 min) on the mean minutes of PA implemented was larger than a quasi-experimental study by Cradock et al 8 in the USA (18 min) and a randomised trial by Naylor et al 30 31 Action Schools! BC (AS!BC) in Canada (10 min) that also sought to support schools implementation of a 150 min MVPA policy through scheduling PE, recess and integrated classroom PA. The absolute change in minutes scheduled by the intervention groups in these studies was, however, comparable (44.2 min vs 46.5 min vs 55.2 min/week). All three studies used similar implementation strategies, including: to identify and train school champions, provide equipment and curricular materials. Similar to others32 we trained generalist classroom teachers to deliver PA, as compared with other studies that trained PE teachers and school staff wellness champions to implement the policy.8 Given the well-documented barriers generalist classroom teachers report in implementing PA11 these findings are promising given the potential population reach classroom teachers have.

Characterising the effect of the intervention

The intervention effectively increased teacher’s willingness to deliver energiser breaks. Teacher’s initial and sustained implementation of energisers contributed to 52% and 85% of the intervention effect at 12 and 18 months, respectively. This is consistent with both AS!BC32 and a 3-year RCT which aimed to increase the adoption of energisers by classroom teachers as part of the US CATCH programme.33 Undertaken in 30 Texas middle-schools the study found at the end of year 1 approximately 40% of teachers had implemented energisers which increased to approximately 48% of teachers by the end of year 2. These findings and ours suggest that energisers are acceptable, and possibly sustainable, PA strategies for teachers. This may be because energisers are characteristically short, easily embedded within or between lessons and require minimal to no equipment. However, evidence from our studies13 and others34 suggest that despite their simplicity, teachers still require some support to implement energisers. While similar implementation strategies were employed in both CATCH and our study, the intensity of ongoing support and the resources provided to teachers differed. Compared with CATCH, which provided printed resources to teachers, we promoted teacher’s use of existing online energisers. In doing so we helped teachers overcome barriers related to confidence and competence to deliver PA.11 In turn, this may reduce the need for ongoing intensive implementation support to upskill teachers, thereby potentially providing a more cost-effective, scalable and sustainable intervention.

Maintaining intervention effects

In contrast, our findings suggest that once implementation support ended, the intervention was not effective at maintaining the modest improvements in teachers’ implementation of PE (despite this being a mandatory subject) and integrated lessons. While there is limited empirical evidence, sustainability frameworks suggest that organisational factors such as funding and leadership support, staff turnover, training and programme fit, are associated with the continued delivery of health programmes in schools.35 To ensure that such interventions are resilient to attenuation over time, prior to withdrawing implementation support, future studies may consider supporting schools to: identify ongoing funding sources, establish processes that enable the handover of programme knowledge to new staff and develop plans for how the programme may be able to adapt overtime while still retaining core components.

Strengths and limitations

This is the largest cluster RCT to assess the effectiveness of a multi-strategy implementation intervention on schools implementation of a PA policy. We specifically selected implementation strategies and behaviour change techniques that addressed known barriers and were mapped against a robust theoretical framework. We assessed implementation processes and conducted a follow-up which is rarely done in school-based studies. Our study also had a number of limitations. The primary outcome relied on self-report via a log-book, a method selected on the basis of use in previous trials8 32 36 analogous evidence suggests such measures may represent a valid measure of implementation in this setting, and the pragmatics of undertaking research at such a large scale. However, such measures are at risk of social desirability and recall bias which likely lead to overestimates in the reported. Nonetheless, the use of more objective measures, that capture the fidelity to which strategies were implemented, may improve the internal validity of the trial and its findings. In addition, increasing the frequency that such data is collected throughout the study period could identify any seasonal impact on scheduling. Further, increased scheduling of PA does not guarantee that increased activity is delivered, delivered to a standard that increases students MVPA or that all students participate. For example, in our pilot study, despite an increase of 36 min in teachers weekly scheduling of PA, we saw only an approximately increase of 15 min in student weekly MVPA. The implementation strategy was developed using a theoretically guided process and drawing on considerable formative evaluation undertaken in the setting. However, the process may not have considered in sufficient detail the extent to which characteristics of schools may interact with core components of implementation intervention components and other contextual factors to enhance or impede implementation success. A more nuanced strategy development process articulating, and then assessing and reporting these interactions may have provided useful insights to guide future implementation efforts. Finally, a deeper understanding of what helped drive the intervention effect could have been explored more rigorously through a comprehensive approach such as that recommended by McKay et al 37 using both qualitative and quantitative measures.

Conclusion

School PA interventions must be effectively implemented at scale if we are to achieve public health benefit.37 However, a recent systematic review reported that scaled-up PA interventions lose up to 60% of their prescale effect.38 A primary impediment to the successful implementation at scale is the selection of interventions that are not amenable to scale-up. This trial exceeded the intervention effect from the pilot study suggesting that both the PA practices and the implementation intervention is amenable to scale. However, future studies are needed to determine the minimal intervention ‘dose’ required to sustain schools delivery of all intervention components and the cost to do so.

Key messages.

What are the findings?

The 12-month multi-strategy implementation intervention significantly increased teachers’ implementation of weekly minutes of physical activity (PA) and the proportion of teachers complying with a mandatory PA policy.

Teachers’ implementation of energisers contributed the most time to the intervention effect at 12 months and 18 months, suggesting they are amenable school PA practices for scale and sustainability.

The intervention had very little effect on teacher implementation or maintenance of other PA practices (ie, physical education, sport and integrated lessons).

How might it impact on clinical practice in the future?

Policy makers and researchers looking to support schools implement efficacious PA policies or programmes should consider the use of a theoretically designed, multi-strategy implementation intervention, targeting known barriers to implementation. This may help overcome the limited effects found in school-based PA programmes once they move from efficacy to scale.

Footnotes

Twitter: @NicoleKNathan, @Dr_Alix_Hall, @RachSutherland, @AdrianBauman, @AcademiCat, @adamjsmith_92, @luke.wolfenden1

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it published Online First. The results section, table 1 and contributor sections have been updated.

Contributors: NN led the development of this manuscript. NN, NM and RS LW conceived the intervention concept. LW, JW, AB, CR, NN, CO secured funding for the study. NN, PJN, ALC, RS, KG, BD, NM, JB, LW guided the piloting and design of the intervention. NN, AH, CL, LW, AB, CR, PJN, ALC, KH, AS, BE, CL guided the evaluation design and data collection. PR contributed to the development of data collection methods specific to the cost and cost-effectiveness measures. CO, AH and CLecathelinais developed the analysis plan. NN, JW, AB, CR, AS, CO, PJN, ALC, BD, SC, NM, KH, JB, LW are all members of the Advisory Group that oversaw the program. All authors contributed to developing the protocols and reviewing, editing, and approving the final version of the paper.

Funding: LW was supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (APP1128348), Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (101175) and a Hunter New England Clinical Research Fellowship; RS was supported by an NHMRC TRIP Fellowship (APP1150661).

Competing interests: Authors NN, RS, KG, NM, MP, RJ, VA, JW and LW receive salary support from Hunter New England Local Health District, which contributes funding to the project outlined in this study. Similarly, author CR and receive salary support from the New South Wales Health Office of Preventive Health which also contributed funding to this project. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests. The project is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Partnership Project grant (APP1133013). The NHMRC has not had any role in the design of the study as outlined in this protocol and will not have a role in data collection, analysis of data, interpretation of data and dissemination of findings. As part of the NHMRC Partnership Grant funding arrangement, the following partner organisations also contribute fund: Hunter New England Local Health District and the NSW Health Office of Preventive Health. Individuals in positions that are fully or partly funded by these partner organisations (as described in the Competing interests section) had a role in the study design, data collection, analysis of data, interpretation of data and dissemination of findings. At the time of this study NN was supported by an NHMRC TRIP Fellowship (APP1132450) and a Hunter New England Clinical Research Fellowship; LW was supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (APP1128348), Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (101175) and a Hunter New England Clinical Research Fellowship; RS was supported by an NHMRC TRIP Fellowship (APP1150661).

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (no. 06/07/26/4.04), The University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2008-0343) and relevant school bodies.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020. Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Okely AD, Salmon J, Vella SA. A systematic review to inform the Australian sedentary behaviour guidelines for children and young people. In: Report prepared for the Australian Government Department of Health, ed, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. NSW Government . Rationale for change; sport and physical activity policy- revised 2015. In: NSW department of education and communities, ed. School Sport Unit, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen P, Wang D, Shen H, et al. Physical activity and health in Chinese children and adolescents: expert consensus statement (2020). Br J Sports Med 2020;54:1321–31. 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nørager Johansen DL, Neerfeldt Christensen BF, Fester M, et al. Results from Denmark's 2018 report card on physical activity for children and youth. J Phys Act Health 2018;15:S341–3. 10.1123/jpah.2018-0509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Public Health England . What works in schools and colleges to increase physical activity? London: PHE Publications, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olstad DL, Campbell EJ, Raine KD, et al. A multiple case history and systematic review of adoption, diffusion, implementation and impact of provincial daily physical activity policies in Canadian schools. BMC Public Health 2015;15:385. 10.1186/s12889-015-1669-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cradock AL, Barrett JL, Carter J, et al. Impact of the Boston active school day policy to promote physical activity among children. Am J Health Promot 2014;28:S54–64. 10.4278/ajhp.130430-QUAN-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thompson HR, Linchey J, Madsen KA. Are physical education policies working? A snapshot from San Francisco, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;10:E142. 10.5888/pcd10.130108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harrington DM, Belton S, Coppinger T, et al. Results from Ireland's 2014 report card on physical activity in children and youth. J Phys Act Health 2014;11 Suppl 1:S63–8. 10.1123/jpah.2014-0166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nathan N, Elton B, Babic M, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of physical activity policies in schools: a systematic review. Prev Med 2018;107:45–53. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mâsse LC, Naiman D, Naylor P-J. From policy to practice: implementation of physical activity and food policies in schools. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:71. 10.1186/1479-5868-10-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nathan NK, Sutherland RL, Hope K, et al. Implementation of a school physical activity policy improves student physical activity levels: outcomes of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Phys Act Health 2020:1009–18. 10.1123/jpah.2019-0595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wolfenden L, Nathan NK, Sutherland R, et al. Strategies for enhancing the implementation of school-based policies or practices targeting risk factors for chronic disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;11:CD011677. 10.1002/14651858.CD011677.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Alcaraz JE, et al. The effects of a 2-year physical education program (SPARK) on physical activity and fitness in elementary school students. sports, play and active Recreation for kids. Am J Public Health 1997;87:1328–34. 10.2105/AJPH.87.8.1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barr-Anderson DJ, AuYoung M, Whitt-Glover MC, et al. Integration of short bouts of physical activity into organizational routine a systematic review of the literature. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:76–93. 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Riley N, Lubans DR, Holmes K, et al. Findings from the easy minds cluster randomized controlled trial: evaluation of a physical activity integration program for mathematics in primary schools. J Phys Act Health 2016;13:198–206. 10.1123/jpah.2015-0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nathan N, Wiggers J, Bauman AE, et al. A cluster randomised controlled trial of an intervention to increase the implementation of school physical activity policies and guidelines: study protocol for the physically active children in education (PACE) study. BMC Public Health 2019;19:170. 10.1186/s12889-019-6492-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, et al. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012;345:e5661. 10.1136/bmj.e5661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. Standards for reporting implementation studies (STARI) statement. BMJ 2017;356:i6795. 10.1136/bmj.i6795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wiggers J, Wolfenden L, Campbell E. Good for Kids, Good for Life 2006-2010 Evaluation Report. In: NSW Ministry of Health, ed. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing. Sutton: Silverback Publishing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, et al. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol 2008;57:660–80. 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. NSW Government . K–6 curriculum requirements, 2020. Available: https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/portal/nesa/k-10/understanding-the-curriculum/k-6-curriculum-requirements [Accessed 15 Oct 2020].

- 25. Bessems KMHH, Van Assema P, Martens MK, et al. Appreciation and implementation of the Krachtvoer healthy diet promotion programme for 12- to 14- year-old students of prevocational schools. BMC Public Health 2011;11:909. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Nassau F, Singh AS, van Mechelen W, et al. Exploring facilitating factors and barriers to the nationwide dissemination of a Dutch school-based obesity prevention program “DOiT”: a study protocol. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1201. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci 2017;12:108. 10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Adrian M, Coifman J, Pullmann MD, et al. Implementation determinants and outcomes of a Technology-Enabled service targeting suicide risk in high schools: mixed methods study. JMIR Ment Health 2020;7:e16338. 10.2196/16338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Naylor P-J, Macdonald HM, Reed KE, et al. Action schools! BC: a socioecological approach to modifying chronic disease risk factors in elementary school children. Prev Chronic Dis 2006;3:A60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reed KE, Warburton DER, Macdonald HM, et al. Action schools! BC: a school-based physical activity intervention designed to decrease cardiovascular disease risk factors in children. Prev Med 2008;46:525–31. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Naylor P-J, Macdonald HM, Zebedee JA, et al. Lessons learned from Action Schools! BC--an 'active school' model to promote physical activity in elementary schools. J Sci Med Sport 2006;9:413–23. 10.1016/j.jsams.2006.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Delk J, Springer AE, Kelder SH, et al. Promoting teacher adoption of physical activity breaks in the classroom: findings of the central Texas catch middle school project. J Sch Health 2014;84:722–30. 10.1111/josh.12203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Raney M, Henriksen A, Minton J. Impact of short duration health & science energizers in the elementary school classroom. Cogent Education 2017;4:1399969. 10.1080/2331186X.2017.1399969 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shelton RC, Cooper BR, Stirman SW. The sustainability of evidence-based interventions and practices in public health and health care. Annu Rev Public Health 2018;39:55–76. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van Nassau F, Singh AS, van Mechelen W, et al. Exploring facilitating factors and barriers to the nationwide dissemination of a Dutch school-based obesity prevention program "DOiT": a study protocol. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1201. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McKay H, Naylor P-J, Lau E, et al. Implementation and scale-up of physical activity and behavioural nutrition interventions: an evaluation roadmap. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2019;16:102. 10.1186/s12966-019-0868-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lane C, McCrabb S, Nathan N, et al. How effective are physical activity interventions when they are scaled-up: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2021;18:16. 10.1186/s12966-021-01080-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.