This cross-sectional study examines the reporting of participant race and ethnicity in published pediatric clinical trials from 2011 to 2020.

Key Points

Question

How did participant race and ethnicity in pediatric clinical trials published from 2011 to 2020 compare with the corresponding US populations?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 612 articles published from 2011 to 2020 in leading pediatric and general medical journals with 565 618 total participants, Black/African American children were enrolled proportionally more than the US population of Black/African American children; Hispanic/Latino children were enrolled commensurately with the population of Hispanic/Latino children; and American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, and Native American/Pacific Islander children were enrolled less than the respective US populations of these groups. White children were enrolled less than expected but represented 46.0% of participants.

Meaning

The findings suggest that disparities exist in pediatric clinical trial enrollment of Black/African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, and Native American/Pacific Islander pediatric populations in the US.

Abstract

Importance

Equitable representation of participants who are members of racial and ethnic minority groups in clinical trials enhances inclusivity in the scientific process and generalizability of results.

Objective

To assess participant race and ethnicity in pediatric clinical trials published from 2011 to 2020.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study examined articles reporting pediatric clinical trials conducted in the US published in 5 leading general pediatric and 5 leading general medical journals from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Reporting of participant race and ethnicity and comparison of enrolled participants vs US census populations of pediatric racial and ethnic groups in published clinical trials.

Results

The study included 612 articles reporting pediatric clinical trials during the study period, with 565 618 total participants (median per trial, 200 participants [IQR, 90-571 participants]). Of the 612 articles, 486 (79.4%) reported participant race and 338 (55.2%) reported participant ethnicity. From 2011 to 2020, relative rates of reporting of participant race increased by 7.9% per year (95% CI, 0.2%-16.3% per year) and reporting of ethnicity increased by 11.4% per year (95% CI, 4.8%-18.4% per year). Among articles reporting race and ethnicity, the method of assignment was not reported in 261 of 511 articles (51.1%) and 207 of 359 articles (57.7%), respectively. Black/African American children were enrolled proportionally more than the US population of Black/African American children (odds ratio [OR], 1.88; 95% CI, 1.87-1.89). Hispanic/Latino children were enrolled commensurately with the US population of Hispanic/Latino children (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01-1.03). American Indian/Alaska Native (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.79-0.85), Asian (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.55-0.57), and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.61-0.72) children were enrolled significantly less compared with the respective US populations of these groups. White children were enrolled less than expected (OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.84-0.85) but represented 188 156 (46.0%) of participants in trials reporting race or ethnicity.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cross-sectional study revealed that the proportion of published pediatric clinical trials that reported participant race and ethnicity increased from 2011 to 2020, but participant race and ethnicity were still underreported. Disparities existed in pediatric clinical trial enrollment of American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander children. The greater representation of Black/African American children compared with the US population suggests inclusive research practices that could be extended to other historically disenfranchised racial and ethnic groups.

Introduction

Clinical trials provide the highest level of evidence for assessment of the safety, comparative effectiveness, and efficacy of medications and interventions that guide clinical care.1 However, results from clinical trials that lack racial and ethnic minority participants may not be generalizable to all populations that may benefit from trial results.2,3 Race is a social construct reflecting the “impact of unequal social experiences on health,”4,p872 and ethnicity refers to social groupings based on culture and language.4,5 The National Institutes of Health and the US Food and Drug Administration mandate the planned inclusion of participants from multiple racial and ethnic groups when applying for support.6,7

Nevertheless, studies have shown that participants’ race and ethnicity are often not reported in clinical trial results.8,9,10,11 Studies evaluating enrollment in pediatric clinical trials for hematologic malignancies have demonstrated that Black/African American participants12,13 and Hispanic/Latino participants14,15 have been underrepresented. In a 2003 study, Walsh and Ross16 reviewed articles published in 3 general pediatric journals during a single year and demonstrated that Black participants were included more than expected and White participants and Hispanic/Latino participants were included less than expected in clinical trials; Black/African American and Hispanic children were underrepresented in therapeutic research.16

Understanding trial enrollment patterns by race and ethnicity is necessary to ensure that pediatric clinical trials address, rather than exacerbate, health care inequities. Characterization of participant race and ethnicity in trial enrollment may inform future recruitment strategies and requirements. Our objective was to assess participant race and ethnicity reported in published pediatric clinical trials and to evaluate rates and trends in race and ethnicity published in general pediatric and medical journals. We hypothesized that children in racial and ethnic minority groups would be underrepresented in published clinical trials.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional study of articles reporting results of pediatric clinical trials published in 5 leading general pediatric journals and 5 leading general medical journals from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2020. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines. The Boston Children’s Hospital institutional review board exempted this study from review because all data were publicly available. No participant consent was needed for this analysis because all data were obtained from published articles.

Data Sources

We reviewed articles reporting pediatric clinical trials in JAMA Pediatrics, The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, Pediatrics, the Journal of Adolescent Health, and the Journal of Pediatrics. We also reviewed articles reporting pediatric clinical trials in the New England Journal of Medicine, The Lancet, JAMA, BMJ, and PLoS Medicine. These were the leading general pediatric and general medical journals by impact factor.17

To compare trial enrollment by race and ethnicity with the US population, we used the 2019 annual estimate of population sizes from the US census at the national, state, and county levels for children and adolescents aged 0 to 18 years (aged 0 to 19 years at the county level).18 We defined clinical trials according to the National Institutes of Health definition.19

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included articles reporting results of clinical trials that exclusively enrolled participants 0 to 18 years of age or those in which the median or mean age of participants was less than or equal to 18 years. We excluded articles that did not report trial results, trials conducted outside the US, and secondary analyses of trials if the original trial was included.

Data Extraction and Variables

We queried PubMed to identify all published articles in the selected journals. Then using key search terms, we extracted articles likely to report pediatric clinical trials (eAppendix in the Supplement). After an initial training period, 1 of us (C.A.R., A.M.S., S.M., E.A., J.J., J.M., E.N.P., or E.W.F.) reviewed the abstract and full text of each article. We extracted the number of enrolled participants, participant age group or groups, race, ethnicity, how race and ethnicity were ascertained, whether participants’ primary language was reported, community stakeholders’ involvement, and participants’ reported socioeconomic data.20 We reviewed the instructions for authors of each journal to ascertain whether policies regarding the reporting of participant race and ethnicity existed. Data were collected and managed using the secure REDCap data capture platform.21 Any question about inclusion of an article or specific variables was discussed among us to achieve consensus.

Additional trial characteristics extracted included randomization, masking, trial phase, intervention type, disease or diseases studied, listed funding sources, and trial locations. All variables were extracted from the primary article, supplement information, or ClinicalTrials.gov. For articles without participants’ race and ethnicity, we sent a standardized email to corresponding authors to solicit this information up to 2 times.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the proportion of children enrolled in pediatric clinical trials by race and ethnicity compared with the US population. Race was classified according to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race as follows: American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and White.22 We recorded the number of participants who were documented as “other” race but excluded “other” from our analyses given the heterogeneity of this categorization. Ethnicity was categorized as Hispanic/Latino and treated as a separate category because of inconsistent reporting of participant race and ethnicity (ie, some trials listed Hispanic/Latino as an ethnicity [n = 217], and others listed it as a race [n = 168]). We recorded how participant race and ethnicity were ascertained in each trial.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics of trial characteristics and participant race and ethnicity. We calculated odds ratios (ORs) directly (not from models) using the cross-product ratio of the proportion of trial participants in each racial or ethnic group to the expected proportion (ie, children aged 0 to 18 years in the US census in each racial or ethnic group) with 95% CIs. Because most pediatric clinical trials were conducted in academic medical centers in urban areas, we additionally conducted a sensitivity analysis using counties in which trials were conducted as the census comparator. We conducted a subanalysis excluding trials that targeted specific racial or ethnic groups. To understand how reporting changed over time, we created a logistic regression model at the level of individual studies, with race reporting as the dependent variable and year as a linear term (ie, any value between 2011 and 2020) as the independent variable. We calculated the proportion of enrolled children by each racial and ethnic group by year and the mean diversity index of all trials by year using Poisson regression, with an offset for each trial’s log total sample size. Diversity was measured using the diversity index, ranging from 0 (no diversity) to 1 (equal representation of all possible groups).23,24,25 The diversity index was calculated using the formula D = 1 − [(∑ n × [n − 1])/(N × [N − 1])], where n is the number of children for each racial or ethnic group and N is the total number of children in all groups.

For trials conducted in a single state, we conducted an exploratory analysis using logistic regression to test bivariable associations between the outcome of high diversity (defined as trial diversity greater than or equal to that of the state) and covariates theoretically associated with high diversity. All associations with an overall 2-sided P < .20 were included in a multivariable model to assess characteristics associated with participant enrollment with high diversity. We mapped the diversity index of pediatric clinical trials by state and compared them with the respective state’s diversity index. All analyses were conducted using R, version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Trial Characteristics

Among 99 866 articles, 3782 were potentially related to pediatric clinical trials, and 612 reported results of pediatric clinical trials conducted in the US (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Of these 612 articles, 574 (93.8%) were randomized, 159 (26.0%) were nonblinded, and 153 (25.0%) were open-label (Table 1). There were 565 618 total participants (median per trial, 200 participants [IQR, 90-571 participants]). Behavioral interventions were most common (244 [39.9%]) (Table 1). A total of 193 197 participants (34.2%) were adolescents (Table 2).

Table 1. Characteristics of 612 Pediatric Trials Published in Leading Pediatric and General Medical Journals From 2011 to 2020a.

| Characteristic | Trials, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Trial allocation | |

| Randomized | 574 (93.8) |

| Not randomized | 35 (5.7) |

| Not specified | 3 (0.5) |

| Trial masking | |

| Nonblinded | 159 (26.0) |

| Open-label | 153 (25.0) |

| Double-blind | 127 (20.8) |

| Single-blind | 98 (16.0) |

| Other | 27 (4.4) |

| Not specified | 48 (7.8) |

| Trial phase | |

| 1 | 17 (2.8) |

| 2 | 46 (7.5) |

| 3 | 73 (11.9) |

| 4 | 14 (2.3) |

| Not specified | 59 (9.6) |

| Not applicable | 403 (65.8) |

| Participant enrollment | |

| <100 | 172 (28.1) |

| 100-499 | 284 (46.4) |

| >500 | 156 (25.5) |

| Trial intervention | |

| Behavioral | 244 (39.9) |

| Drug or biologic agent | 195 (31.9) |

| Device or procedure | 75 (12.3) |

| Dietary supplement | 44 (7.2) |

| Health services | 21 (3.4) |

| Screening or referral | 26 (4.2) |

| Other | 7 (1.1) |

| Disease studiedb | |

| Infectious diseases | 95 (14.8) |

| Endocrine or metabolic diseases | 63 (9.8) |

| Lung diseases | 61 (9.5) |

| Neurologic disorders | 56 (8.7) |

| Developmental disorders | 53 (8.2) |

| Nutrition, obesity, and growth | 52 (8.1) |

| Neonatal disorders | 49 (7.6) |

| Cancer | 31 (4.8) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 29 (4.5) |

| Mental illness | 26 (4.0) |

| Substance use disorders | 25 (3.9) |

| Social determinants of health | 22 (3.4) |

| Sexual activity or pregnancy | 18 (2.8) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 16 (2.5) |

| Injuries or physical trauma | 9 (1.4) |

| Other | 38 (5.9) |

| Funding source | |

| Public | 345 (55.9) |

| Private | 114 (18.5) |

| Public and private | 128 (20.7) |

| None reported | 30 (4.9) |

| Recruitment sites | |

| 1 | 367 (64.3) |

| 2-4 | 79 (13.8) |

| >5 | 125 (21.9) |

| Participant primary language reported in article | 162 (26.4) |

| Article reported community stakeholder involvement | 59 (9.6) |

| Published in journal with race or ethnicity reporting statement | 425 (69.4) |

| Socioeconomic data reported in articlec | 296 (48.3) |

JAMA Pediatrics, The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, Pediatrics, Journal of Adolescent Health, The Journal of Pediatrics, New England Journal of Medicine, The Lancet, JAMA, BMJ, and PLoS Medicine.

In 31 trials, more than 1 disease category was studied.

Included insurance type or status, household income, community-level income, caregiver education, caregiver employment status, and receipt of social benefits.

Table 2. Characteristics of Participants Enrolled in Pediatric Trials Published in Leading Pediatric and General Medical Journals From 2011 to 2020.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) (N = 565 618) |

|---|---|

| Age group in article | |

| Neonate (0-30 d) | 51 860 (9.2) |

| Infant (31-365 d) | 29 360 (5.2) |

| Toddler (1-3 y) | 30 922 (5.5) |

| Preschool age (4-5 y) | 34 901 (6.2) |

| School age (6-12 y) | 88 507 (15.6) |

| Adolescent (13-18 y) | 193 197 (34.2) |

| All pediatric age groups enrolled | 136 921 (24.2) |

| Race or ethnicity | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2815 (0.5) |

| Asian | 11 869 (2.1) |

| Black/African American | 93 988 (16.6) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 105 770 (18.7) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 543 (0.1) |

| White | 188 156 (33.3) |

| Othera | 5579 (1.0) |

| Not reported | 156 898 (27.7) |

Other as defined in published trials.

Participant Race and Ethnicity

Of the 612 articles, 486 (79.4%) reported participant race and 338 (55.2%) reported participant ethnicity. Of the 126 and 274 articles that did not report race or ethnicity, respectively, corresponding authors provided race data for 25 (19.8%) and ethnicity data for 21 (7.7%). Of the 511 articles with participant race data available, 261 (51.1%) did not report how it was measured, 231 (45.2%) measured race through participant or caregiver report, 16 (3.1%) obtained race from electronic health records, and 3 (0.6%) reported that trial staff assigned participants’ race. Of the 359 articles with participant ethnicity data available, 207 (57.7%) did not report how it was measured, 139 (38.7%) measured ethnicity by participant or caregiver report, 9 (2.5%) obtained participant ethnicity from electronic health records, and 4 (1.1%) reported that trial staff assigned participant ethnicity. A total of 156 898 participants (27.7%) had no race or ethnicity reported (Table 2).

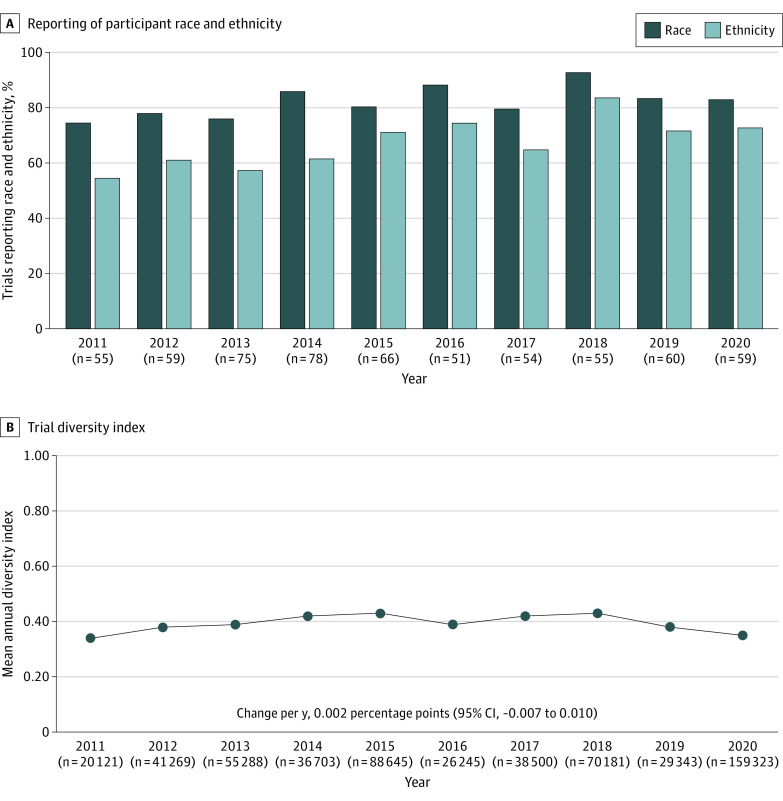

Trends in Reporting and Enrollment

There was a relative increase in reporting of participant race (7.9% per year; 95% CI, 0.2%-16.3% per year) and ethnicity (11.4% per year; 95% CI, 4.8%-18.4% per year) from 2011 to 2020 (Figure 1A). In 2020, there were 59 published pediatric trials, of which 49 (83.1%) reported participant race and 43 (72.9%) reported participant ethnicity. There was a decrease over time in the proportion of enrolled American Indian/Alaska Native (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.84; 95% CI, 0.83-0.85), Black/African American (IRR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.89-0.89), Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (IRR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.79-0.83), and White children (IRR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.97-0.97). The proportion of enrolled Asian children increased (IRR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.01-1.11), and the proportion of Hispanic/Latino children was similar over time (IRR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.00-1.01). The mean annual diversity index of pediatric clinical trials did not change during the study period (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Reporting of Participant Race and Ethnicity and the Trial Diversity Index in Pediatric Clinical Trials From 2011 to 2020.

A, The n values shown are the number of trials. B, The n values shown are the number of participants.

Expected Compared With Actual Trial Enrollment

In comparison with national US census data, Black/African American children were enrolled 88% more than expected (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.87-1.89), and Hispanic/Latino participants were enrolled at a rate commensurate with the US population of Hispanic/Latino children (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.01-1.03). American Indian/Alaska Native (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.79-0.85), Asian (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.55-0.57), and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.61-0.72) children were enrolled significantly less compared with the respective US populations of these groups (Table 3). In comparison with US census data in counties where trials were conducted, Black/African American children were enrolled proportionally more than expected (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.49-1.51), as were American Indian/Alaska Native (OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.11-1.20) and White children (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.23-1.25) (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Proportions of Participants Enrolled in Published Clinical Trials Compared With US Census Data by Race and Ethnicity.

| Race and ethnicitya | No. (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI)c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants enrolled | US census population aged 0-18 yb | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2815 (0.7) | 651 733 (0.8) | 0.82 (0.79-0.85) |

| Asian | 11 869 (2.9) | 3 911 472 (5.1) | 0.56 (0.55-0.57) |

| Black/African American | 93 988 (22.9) | 10 600 476 (13.7) | 1.88 (1.87-1.89) |

| Hispanic/Latinod | 105 770 (25.9) | 19 693 433 (25.5) | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 543 (0.1) | 155 292 (0.2) | 0.66 (0.61-0.72) |

| White | 188 156 (46.0) | 38 920 502 (50.4) | 0.84 (0.84-0.85) |

Comparison was done excluding participants whose race was not reported or whose race was reported as “other” because these categories are not available in the US census.

The US census racial groups included only data for non-Hispanic populations (ie, White, non-Hispanic).

Relative likelihood of being enrolled by race or ethnicity was calculated using a 2 × 2 table, with the 2 rows representing a given group (top row) and the sum of all other groups (bottom row) and columns representing trial enrollment counts (first column) and US census counts (second column). The cross-product ratio of the proportion of trial participants in each race or ethnicity group to the expected proportion (ie, children aged 0-18 years in the US census in each racial or ethnic group) was assessed.

The US census Hispanic groups included all children with ethnicity recorded as Hispanic regardless of racial category.

Trials that enrolled fewer than 100 participants and trials that enrolled 100 to 499 participants demonstrated lower Hispanic/Latino enrollment than expected (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Our subanalysis excluding trials that targeted specific racial or ethnic groups demonstrated comparisons between enrolled and expected participants that were similar to those in all trials (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Some differences in enrollment were observed in comparison with the US population by intervention type, but enrollment by intervention type did not differ from overall enrollment patterns (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Factors Associated With Diverse Trial Enrollment

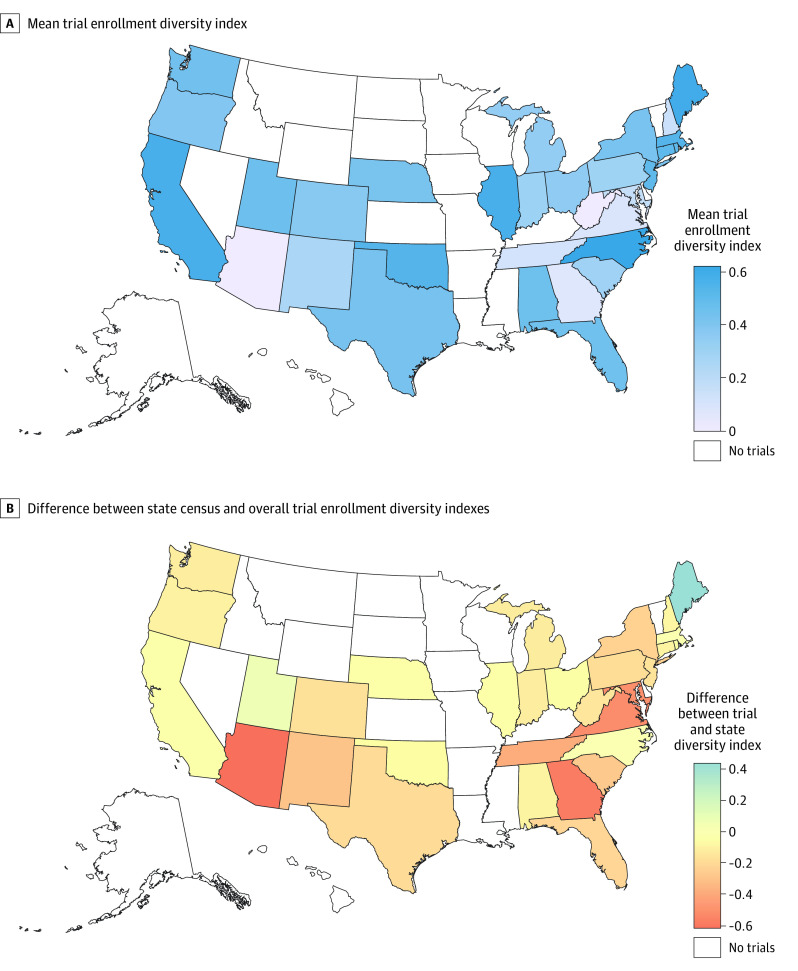

The mean diversity index of included pediatric clinical trials was 0.39 (95% CI, 0.38-0.41; range, 0-0.75). In bivariable analysis, trials with 500 or more participants had a diversity index of at least the level of the state where the research was conducted compared with trials that had fewer than 100 participants (OR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.11-4.70). Stakeholder involvement in the trial design was associated with lower odds of enrolling participants at least as diverse as in the state where the trial was conducted (adjusted OR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.10-0.90). Journal policy statements on reporting of race and ethnicity were not associated with a diversity index of at least the level of the state where the research was conducted (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Pediatric Trial Enrollment by State

Diversity indexes of pediatric clinical trials conducted in single states are shown in Figure 2A. The diversity indexes of trials conducted in Arizona, New Mexico, Georgia, Tennessee, Virginia, and Maryland were lower than the respective states’ pediatric diversity indexes (Figure 2B). Trials conducted in Maine were most diverse in comparison with the state’s diversity index. At the state level, Black/African American participants were included more than expected, and White participants were least represented compared with individual states’ respective populations (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Pediatric Clinical Trial Enrollment by State Among Trials Exclusively Conducted in a Single State.

Discussion

Equitable clinical trial enrollment is an actionable step that investigators can take to address health inequities in the US. In this cross-sectional study of 612 pediatric clinical trials with 565 618 children that were published from 2011 to 2020, the proportion of published pediatric clinical trials that reported participant race and ethnicity increased over time, but such data were still underreported. Black/African American children were enrolled 88% more than expected based on the US pediatric population, and Hispanic/Latino children were enrolled commensurately with the population of Hispanic/Latino children; however, children in other racial and ethnic minority groups were enrolled less than expected based on the respective US populations of these groups.

Studies in adult populations have reported that 27% to 83% of published articles did not report participant race or ethnicity.8,9,10,11 In the present study, 83.1% of trial articles published in 2020 reported participant race and 72.9% reported ethnicity, which is higher than the percentage reported in a study in 2003 (pediatric participant race and ethnicity reported in 67% of articles).16 The increased proportion of published pediatric clinical trials that reported participant race and ethnicity in the present study may be associated with the increased recognition of the importance of inclusive trial enrollment and journals’ increased requirement of reporting of participant race and ethnicity. There was significant heterogeneity in how race and ethnicity were measured, with fewer than half of articles reporting that race or ethnicity data were obtained from caregivers or participants. Accurate recording of participant race and ethnicity may be best achieved by asking guardians to report their child’s race and ethnicity according to standardized categories.26,27 Standardization of how race and ethnicity are measured and reported may reduce discrepancies.

Contrary to our hypothesis, Black/African American children were enrolled more than expected and Hispanic/Latino children were enrolled proportionately based on the US population. These findings differ from work in adult populations demonstrating lower enrollment of Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino adults in clinical trials28,29,30,31,32,33 and may reflect greater focus on enrollment of Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino participants by pediatric clinical trialists. Trials that report race and ethnicity may have a greater focus on enrolling these populations. This higher rate of enrollment occurred despite prior evidence suggesting that caregivers of Black/African American children may have distrust of medical research34,35,36 because of the historical and current racism exhibited in medicine in the US.37,38,39 This finding aligns with those of the 2003 analysis of pediatric studies16 but differs from disease-specific studies assessing pediatric participant enrollment.12,13 The majority of pediatric clinical trials likely occurred in academic centers, which are often clustered in urban centers that have higher populations of children in racial and ethnic minority groups. Critical race theory allows examination of elements of structural racism that have led to the over- or underrepresentation of different racial and ethnic groups in these studies. It is possible that the overrepresentation of Black/African American children is associated with the history of redlining and other policies that led to the segregation of Black children in low-income neighborhoods, which frequently exist near academic medical centers.40 Structural racism has also been associated with high poverty rates41 and subsequent high Medicaid enrollment rates among Black/African American families,42 which may lead to the utilization of academic medical centers at higher rates among these families than among privately insured families.43 Our findings may also have been influenced by potential undercounting of children in racial and ethnic minority groups in the US census.44

Our study adds to the existing body of literature by demonstrating that, at the national level, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander children were enrolled less than expected. However, when the proportion of enrolled American Indian/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander children was compared with the population of each state, representation was approximately as expected. Thus, equitable representation may be associated not only with local recruitment but also with the geographic distribution of trial locations.

A recent analysis of trial enrollment among trials funded by the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act similarly demonstrated lower representation of Asian pediatric participants but otherwise commensurate enrollment for children of other races and ethnicities.25 Although the enrollment of diverse participant populations likely relies on multiple factors, there was no association between articles in journals that required reporting of participant race and ethnicity and the enrollment of diverse pediatric participants in single-state trials in our analysis. However, journals’ websites did not explicitly state when these policies were put into place. Articles reporting stakeholder involvement in trial design were less likely to enroll a diverse population in single-state studies; this finding may have been associated with the encouragement of greater representation of participants of racial and ethnic minority groups,45 which in turn may have led to lower diversity indexes.

Given the relatively low representation of some groups in pediatric clinical trials, modifications to current enrollment practices may be needed. Previous studies have suggested that Asian and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander participants may be more likely to enroll if translation is included in recruitment materials.46 Providing recruitment materials in participants’ preferred language and employing multilingual staff have been associated with improved enrollment rates among Hispanic/Latino populations.47,48,49,50 The creation of culturally sensitive materials to explain trial details may be associated with increased recruitment and retention of pediatric participants in trials.51 Beginning in 2022, Medicaid will provide coverage for “the routine costs associated with clinical trial participation”52; this coverage may be associated with greater enrollment among groups that otherwise would not participate because of additional costs.

Limitations

This study has limitations. The sample of published articles may not be representative of all pediatric clinical trials. We reviewed published articles to assess the trials with highest impact and to obtain as much detailed information about the trials as possible.34 The lack of standardized reporting of race and ethnicity among published articles may have led to over- or underestimation of enrollment of some groups. We excluded children categorized as “other” in both trials and the US census because this term had no clear meaning within or among studies. This exclusion may have led to underrepresentation of some groups that might have been categorized as “other” in some trial results. Some trials included populations with known higher rates of diseases, such as sickle cell disease and cystic fibrosis, which likely affected representation of racial and ethnic groups in those trials. However, our subanalysis excluding these trials demonstrated results consistent with those for the overall population. We did not record the reported efficacy of individual interventions by participant race and ethnicity. It is difficult to define catchment areas in clinical trials, particularly because they are reported in published articles and many clinical trials are conducted at academic medical centers in urban areas. We were not able to determine when journals enacted policies regarding the reporting of race and ethnicity.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional study revealed that the proportion of published pediatric clinical trials that reported participant race and ethnicity from 2011 to 2020 increased, but participant race and ethnicity were still underreported. Disparities existed in pediatric clinical trial enrollment among American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander children. The higher representation of Black/African American children compared with the US census population suggests that inclusive research practices could be extended to other historically and currently disenfranchised racial and ethnic groups.

eTable 1. Comparison of Proportion of Participants Enrolled in Published Clinical Trials Compared to United States Census at the County Level by Race and Ethnicity

eTable 2. Comparison of Proportion of Participants Enrolled in Published Clinical Trials Compared to United States Census by Race and Ethnicity Stratified by Trial Size

eTable 3. Comparison of Proportion of Participants Enrolled in Published Clinical Trials Compared to United States Census by Race and Ethnicity Excluding Trials That Were Race- or Ethnicity-Specific by Design

eTable 4. Comparison of Proportion of Participants Enrolled in Published Clinical Trials Compared to United States Census by Race and Ethnicity by Trial Type

eTable 5. Factors Associated With Pediatric Clinical Trial Enrollment With a Diversity Index at Least That of the State in Which the Trial Was Conducted

eFigure 1. Selection of Articles Included in the Analysis of Pediatric Clinical Trial Enrollment by Race and Ethnicity

eFigure 2. Difference in the Percentages of Trial Participants and State Child Population by State and Race Among Single-State Clinical Trials

eAppendix. PubMed Query to Identify Pediatric Clinical Trials Published in Leading Pediatric and General Medical Journals

References

- 1.Hartling L, Scott-Findlay S, Johnson D, et al. ; Canadian Institutes for Health Research Team in Pediatric Emergency Medicine . Bridging the gap between clinical research and knowledge translation in pediatric emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(11):968-977. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garg N, Round TP, Daker-White G, Bower P, Griffiths CJ. Attitudes to participating in a birth cohort study, views from a multiethnic population: a qualitative study using focus groups. Health Expect. 2017;20(1):146-158. doi: 10.1111/hex.12445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leiter A, Diefenbach MA, Doucette J, Oh WK, Galsky MD. Clinical trial awareness: changes over time and sociodemographic disparities. Clin Trials. 2015;12(3):215-223. doi: 10.1177/1740774515571917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amutah C, Greenidge K, Mante A, et al. Misrepresenting race—the role of medical schools in propagating physician bias. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):872-878. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2025768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones CP. Toward the science and practice of anti-racism: launching a national campaign against racism. Ethn Dis. 2018;28(suppl 1):231-234. doi: 10.18865/ed.28.S1.231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institutes of Health . NIH policy on reporting race and ethnicity data: subjects in clinical research. Published 2001. Accessed November 6, 2020. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/not-od-01-053.html

- 7.US Food and Drug Administration . Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials. Published 2016. Accessed November 6, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/75453/download

- 8.Patel P, Muller C, Paul S. Racial disparities in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease clinical trial enrollment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Hepatol. 2020;12(8):506-518. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v12.i8.506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Luca DG, Sambursky JA, Margolesky J, et al. Minority enrollment in Parkinson’s disease clinical trials: meta-analysis and systematic review of studies evaluating treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(4):1709-1716. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loree JM, Anand S, Dasari A, et al. Disparity of race reporting and representation in clinical trials leading to cancer drug approvals from 2008 to 2018. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(10):e191870. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canevelli M, Bruno G, Grande G, et al. Race reporting and disparities in clinical trials on Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;101:122-128. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faulk KE, Anderson-Mellies A, Cockburn M, Green AL. Assessment of enrollment characteristics for Children’s Oncology Group (COG) upfront therapeutic clinical trials 2004-2015. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0230824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winestone LE, Getz KD, Rao P, et al. Disparities in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia (AML) clinical trial enrollment. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60(9):2190-2198. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2019.1574002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aristizabal P, Singer J, Cooper R, et al. Participation in pediatric oncology research protocols: racial/ethnic, language and age-based disparities. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(8):1337-1344. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lund MJ, Eliason MT, Haight AE, Ward KC, Young JL, Pentz RD. Racial/ethnic diversity in children’s oncology clinical trials: ten years later. Cancer. 2009;115(16):3808-3816. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh C, Ross LF. Are minority children under- or overrepresented in pediatric research? Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):890-895. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Web of Science. Journal Citation Reports. Published 2019. Accessed November 18, 2020. https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/journal-citation-reports/

- 18.United States Census . American FactFinder. Published 2018. Accessed November 2, 2018. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?refresh=t

- 19.National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. NIH’s definition of a clinical trial. Published 2017. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://grants.nih.gov/policy/clinical-trials/definition.htm

- 20.Fayanju OM, Ren Y, Thomas SM, et al. A case-control study examining disparities in clinical trial participation among breast surgical oncology patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Cancer Spectr. 2019;4(2):pkz103. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkz103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Office of Management and Budget. Standards for the classification of federal data on race and ethnicity. Accessed November 9, 2020. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/fedreg_race-ethnicity

- 23.Simpson EH. Measurement of diversity. Nature. 1949;163:688. doi: 10.1038/163688a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ESRI . Methodology statement: 2019/2024. ESRI diversity index. Published 2019. Accessed March 20, 2021. https://downloads.esri.com/esri_content_doc/dbl/us/J10268_Methodology_Statement_2019-2024_Esri_US_Demographic_Updates.pdf

- 25.Abdel-Rahman SM, Paul IM, Hornik C, et al. Racial and ethnic diversity in studies funded under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act. Pediatrics. 2021;147(5):e2020042903. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-042903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walline JJ, Walker MK, Mutti DO, et al. ; BLINK Study Group . Effect of high add power, medium add power, or single-vision contact lenses on myopia progression in children: the BLINK randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(6):571-580. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flanagin A, Frey T, Christiansen SL, Bauchner H. The reporting of race and ethnicity in medical and science journals: comments invited. JAMA. 2021;325(11):1049-1052. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2720-2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rencsok EM, Bazzi LA, McKay RR, et al. Diversity of enrollment in prostate cancer clinical trials: current status and future directions. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(7):1374-1380. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-1616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webb Hooper M, Asfar T, Unrod M, et al. Reasons for exclusion from a smoking cessation trial: an analysis by race/ethnicity. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(1):23-30. doi: 10.18865/ed.29.1.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gopishetty S, Kota V, Guddati AK. Age and race distribution in patients in phase III oncology clinical trials. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12(9):5977-5983. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grant SR, Lin TA, Miller AB, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities among participants in US-based phase 3 randomized cancer clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst Cancer Spectr. 2020;4(5):pkaa060. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkaa060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flores LE, Frontera WR, Andrasik MP, et al. Assessment of the inclusion of racial/ethnic minority, female, and older individuals in vaccine clinical trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037640. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Natale JE, Lebet R, Joseph JG, et al. ; Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure (RESTORE) Study Investigators . Racial and ethnic disparities in parental refusal of consent in a large, multisite pediatric critical care clinical trial. J Pediatr. 2017;184:204-208.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajakumar K, Thomas SB, Musa D, Almario D, Garza MA. Racial differences in parents’ distrust of medicine and research. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(2):108-114. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw MG, Morrell DS, Corbie-Smith GM, Goldsmith LA. Perceptions of pediatric clinical research among African American and Caucasian parents. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101(9):900-907. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31037-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sacks TK, Savin K, Walton QL. How ancestral trauma informs patients’ health decision making. AMA J Ethics. 2021;23(2):E183-E188. doi: 10.1001/amajethics.2021.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goyal MK, Johnson TJ, Chamberlain JM, et al. ; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) . Racial and ethnic differences in emergency department pain management of children with fractures. Pediatrics. 2020;145(5):e20193370. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goyal MK, Kuppermann N, Cleary SD, Teach SJ, Chamberlain JM. Racial disparities in pain management of children with appendicitis in emergency departments. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(11):996-1002. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burdick KJ, Lee LK, Mannix R, Monuteaux MC, Hirsh MP, Fleegler EW. Racial & ethnic disparities in access to pediatric trauma centers in the US. Platform presentation at: American College of Emergency Physicians Annual Meeting; October 2021;. Boston, Massachusetts. [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Center for Education Statistics . Indicator 4 snapshot: children living in poverty for racial/ethnic subgroups. Published 2019. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_rads.asp

- 42.Brooks T, Gardner A. Snapshot of children with Medicaid by race and ethnicity, 2018. Georgetown University Health Policy Institute Center for Children and Families. July 2020. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Snapshot-Medicaid-kids-race-ethnicity-v4.pdf

- 43.Peltz A, Wu CL, White ML, et al. Characteristics of rural children admitted to pediatric hospitals. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20153156. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Hare W, Griffin D, Konicki S. Investigating the 2010 undercount of young children—summary of recent research. US Census Bureau ; 2019. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/program-management/final-analysis-reports/2020-report-2010-undercount-children-summary-recent-research.pdf

- 45.Chung A, Seixas A, Williams N, et al. Development of “Advancing People of Color in Clinical Trials Now!”: web-based randomized controlled trial protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9(7):e17589. doi: 10.2196/17589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly ML, Ackerman PD, Ross LF. The participation of minorities in published pediatric research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(6):777-783. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fischer SM, Kline DM, Min SJ, Okuyama S, Fink RM. Apoyo con cariño: strategies to promote recruiting, enrolling, and retaining Latinos in a cancer clinical trial. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(11):1392-1399. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.7005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanossian N, Rosenberg L, Liebeskind DS, et al. ; FAST-MAG Investigators and Coordinators . A dedicated Spanish language line increases enrollment of Hispanics into prehospital clinical research. Stroke. 2017;48(5):1389-1391. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.014745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kao B, Lobato D, Grullon E, et al. Recruiting Latino and non-Latino families in pediatric research: considerations from a study on childhood disability. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(10):1093-1101. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Curt AM, Kanak MM, Fleegler EW, Stewart AM. Increasing inclusivity in patient centered research begins with language. Prev Med. 2021;149:106621. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zamora I, Williams ME, Higareda M, Wheeler BY, Levitt P. Brief report: recruitment and retention of minority children for autism research. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(2):698-703. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2603-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takvorian SU, Guerra CE, Schpero WL. A hidden opportunity—Medicaid’s role in supporting equitable access to clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(21):1975-1978. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2101627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Comparison of Proportion of Participants Enrolled in Published Clinical Trials Compared to United States Census at the County Level by Race and Ethnicity

eTable 2. Comparison of Proportion of Participants Enrolled in Published Clinical Trials Compared to United States Census by Race and Ethnicity Stratified by Trial Size

eTable 3. Comparison of Proportion of Participants Enrolled in Published Clinical Trials Compared to United States Census by Race and Ethnicity Excluding Trials That Were Race- or Ethnicity-Specific by Design

eTable 4. Comparison of Proportion of Participants Enrolled in Published Clinical Trials Compared to United States Census by Race and Ethnicity by Trial Type

eTable 5. Factors Associated With Pediatric Clinical Trial Enrollment With a Diversity Index at Least That of the State in Which the Trial Was Conducted

eFigure 1. Selection of Articles Included in the Analysis of Pediatric Clinical Trial Enrollment by Race and Ethnicity

eFigure 2. Difference in the Percentages of Trial Participants and State Child Population by State and Race Among Single-State Clinical Trials

eAppendix. PubMed Query to Identify Pediatric Clinical Trials Published in Leading Pediatric and General Medical Journals