Abstract

Trichomonad parasites such as Tritrichomonas foetus produce large amounts of putrescine (1,4-diaminobutane), which is transported out of the cell via an antiport mechanism which results in the uptake of a molecule of spermine. The importance of putrescine to the survival of the parasite and its role in the biology of T. foetus was investigated by use of the putrescine analogue 1,4-diamino-2-butanone (DAB). Growth of T. foetus in vitro was significantly inhibited by 20 mM DAB, which was reversed by the addition of exogenous 40 mM putrescine. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of 20 mM DAB-treated T. foetus revealed that putrescine, spermidine, and spermine levels were reduced by 89, 52, and 43%, respectively, compared to those in control cells. The DAB treatment induced several ultrastructural alterations, which were primarily observed in the redox organelles termed hydrogenosomes. These organelles were progressively degraded, giving rise to large vesicles that displayed material immunoreactive with an antibody to β-succinyl-coenzyme A synthetase, a hydrogenosomal enzyme. A protective role for polyamines as stabilizing agents in the trichomonad hydrogenosomal membrane is proposed.

Trichomonad parasites are common causative agents of vaginitis and cervicitis in humans and other species. Human trichomoniasis is the most prevalent sexually transmitted disease of a nonviral etiology, annually accounting for 2 million to 3 million infections in the United States and over 250 million infections worldwide (26a). Trichomonas vaginalis is implicated in preterm labor, low birth weight, premature rupture of placental membranes, infertility, cervical cancer, and enhanced human immunodeficiency virus transmission (for reviews, see references 12 and 20). Similarly, infection with Tritrichomonas foetus may lead to early embryonic death and pyometra in cattle, sometimes followed by transient or permanent sterility (21), resulting in significant economic losses to farmers. The metabolic pathways of these parasites show considerable similarity; hence, it is likely that drugs with microbicidal effects upon either one of these organisms may also be effective against other trichomonads.

Like other parasitic protozoa, such as Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, Leishmania donovani, and Trypanosoma sp. (1), trichomonads produce large amounts of polyamines both in vitro and in vivo (1, 5, 16, 27, 29). Polyamines are ubiquitous polycations and have been implicated in pivotal cellular activities such as macromolecular synthesis, cell growth, and differentiation (17, 19). The role of polyamines in cell growth and differentiation prompted numerous studies with compounds that inhibit polyamine biosynthesis in patients undergoing chemotherapy for cancer (18) as well as chemotherapy for parasitic diseases such as African trypanosomiasis (1). The lead enzyme of polyamine biosynthesis of many cells is ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), which forms putrescine. In T. vaginalis the putrescine formed by ODC is not metabolized further but is exported with the simultaneous uptake of spermine. 1,4-Diamino-2-butanone (DAB) is a competitive inhibitor of ODC in several cells (22, 24). In several yeast and fungal cell lines it has been shown that depletion of intracellular polyamines by DAB prevents dimorphic transition without affecting growth (9, 14). Furthermore, it has been shown that stage-specific synthesis of mycotoxins such as sterigmatocystin and aflatoxin was also disrupted by polyamine depletion with DAB (10, 11). In all cases the effects of DAB on cell transformation could be reversed by the addition of exogenous putrescine (10, 11, 14). The roles of putrescine and higher polyamines in the control of the dimorphic transformation of yeast and fungal cells have been proposed to be at the level of control of DNA methylation.

In this study, we examined the effects of the putrescine analogue DAB upon the in vitro growth of T. foetus. Consistent with its proposed mode of action, DAB caused a significant decrease of intracellular polyamines. Coincident with the reduction of polyamines were morphological changes in the ultrastructure of the trichomonad redox organelle, the hydrogenosome. We propose that the destruction of the hydrogenosomes is a major contributing factor in the biological activity of DAB toward trichomonads. The possible implications of polyamine deprivation are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites.

The K strain of T. foetus was maintained in TYM (7) medium supplemented with 10% bovine serum (Gibco Life Technologies) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Trophozoites were harvested at the exponential growth phase and were washed twice by centrifugation at 1,400 × g for 15 min in 0.01 M sodium phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2).

Growth studies.

For proliferation measurements, trophozoites (4.4 × 105 cells ml−1) were inoculated in fresh TYM medium in the presence or absence of 20 mM DAB. Growth and motility were assessed every 4 h by visual monitoring under a light microscope and were measured by direct counting of mobile trophozoites in a Neubauer chamber. The reversibility of the effects of DAB was checked by reinoculation of either DAB-treated or -untreated parasites into fresh medium. Forty millimolar putrescine was added to 20-h cultures when indicated. Putrescine alone did not affect the viability of trophozoites at the concentrations used (1, 20, and 40 mM).

Polyamine analysis by HPLC.

DAB-treated and untreated parasites were adjusted to 107 cells ml−1 with 6% (vol/vol) ice-cold perchloric acid. Proteins were removed by centrifugation (14,000 × g), and aliquots were neutralized with KOH at a final concentration of 6%. Polyamines were separated by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis with a Perkin-Elmer LC 410 pump (North American Instruments Division, New Hyde Park, N.Y.) coupled to a C18 10-μm column (4.5 by 250 mm) at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1, as described elsewhere (31). The derivatized samples were detected by fluorescence with an excitation wavelength of 320 nm and an emission wavelength of 455 nm. Areas under the peaks were quantitated with a β-RAM computer program (IN/US Systems, Inc., Fairfield, N.J.).

Transmission electron microscopy.

Parasites were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) for 60 min and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide–0.8% potassium ferricyanide–1 mM CaCl2 in the same buffer for 30 min. After washing, the cells were dehydrated with an acetone series and were embedded in Epon. Thin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and were observed under a Zeiss 900 electron microscope.

Generation of β-SCS antiserum.

The β-succinyl-coenzyme A synthetase (β-SCS) antiserum was obtained by immunization of rabbits with purified, recombinant β-SCS protein as described previously (13).

Immunocytochemistry.

Trophozoites were fixed overnight at 4°C in 1% grade I glutaraldehyde–4% paraformaldehyde–0.2% picric acid–0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2). Free aldehyde groups were quenched in a 0.1 M glycine solution for 60 min, and the cells were then dehydrated with a cold methanol series and were embedded in hydrophilic resin (Lowicryl K4M) (3). Nonspecific protein binding sites in thin sections were blocked in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 8.0) containing 3% bovine serum albumin and 0.01% Tween 20 and were incubated with β-SCS antiserum followed by incubation with 10-nm gold-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G. The grids were then stained with uranyl acetate and were observed under a Zeiss 902 CEM transmission electron microscope. Studies with negative controls were carried out by omission of β-SCS antiserum or by the use of a nonrelated antibody. No labeling was observed under such conditions.

Chemicals.

HPLC-grade buffer reagents and thin-layer chromatography solvents were obtained from Fisher Scientific. Ornithine, arginine, alanine, and lysine HPLC standards were from Fluka Chemicals AG, Buchs, Switzerland; putrescine, spermine, spermidine, and cadaverine HPLC standards were from Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.; all other reagents including DAB were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.

RESULTS

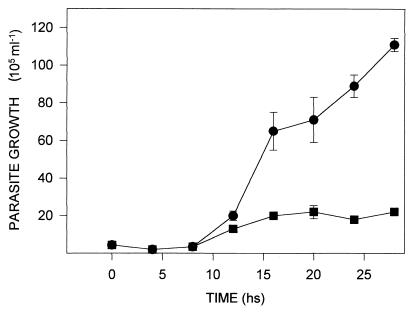

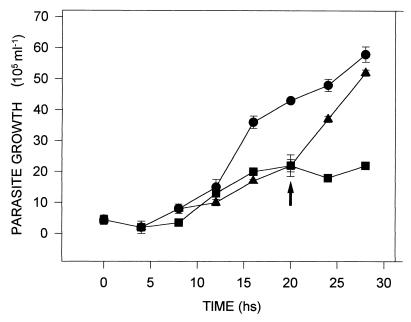

The addition of 20 mM DAB to the culture medium inhibited the growth of T. foetus (Fig. 1) but did not appear to affect motility. Growth inhibition was reversed when the DAB-treated parasites were seeded into fresh medium after 28 h (data not shown). Since putrescine is the major polyamine produced by the parasite, 40 mM putrescine was added to 20-h cultures of control and DAB-treated parasites. It was observed that putrescine rapidly restored the growth of DAB-treated parasites (Fig. 2) but had no effect upon the growth of control cells. The effect of DAB on polyamine biosynthesis by the parasites was assessed by HPLC analysis of intracellular polyamine levels, and these levels were compared to those in untreated control cells (Table 1). DAB-treated parasites had significantly reduced levels of putrescine, spermidine, and spermine compared to the levels in control cells (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Altered T. foetus growth by putrescine analogue. Parasite trophozoites were grown in TYM medium in the presence (■) or absence (●) of 20 mM DAB. Cell growth was quantified for 26 h as described in the Materials and Methods. Results are means ± standard deviations for one representative of four independent assays that yielded similar results.

FIG. 2.

Putrescine reverts the inhibitory effect of DAB on T. foetus growth. Putrescine (40 mM) was added to 20-h cultures of 20 mM DAB-treated cells (▴). The control were untreated cells (●) and cells treated with 20 mM DAB ■ 20 mM DAB-treated cells (■) to which no exogenous putrescine was added. The arrow indicates the addition of putrescine to the cultures. Results are representative of three independent assays that yielded similar results.

TABLE 1.

HPLC analysis of the polyamine content of normal and 20 mM DAB-treated T. foetus

| Cell | Content (nmol/107 cells [nmol/mg of protein])a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Putrescine | Spermidine | Spermine | |

| Control cells | 79.0 (56.0) ± 11.0 | 23.0 (16.0) ± 8.0 | 42.0 (30.0) ± 2.0 |

| DAB-treated | 8.5 (6.0) ± 12.0 | 11.0 (7.7) ± 6.6 | 24.0 (17.0) ± 2.0 |

| % Reduction | 89 | 52 | 43 |

Values are means ± standard deviations for duplicate experiments.

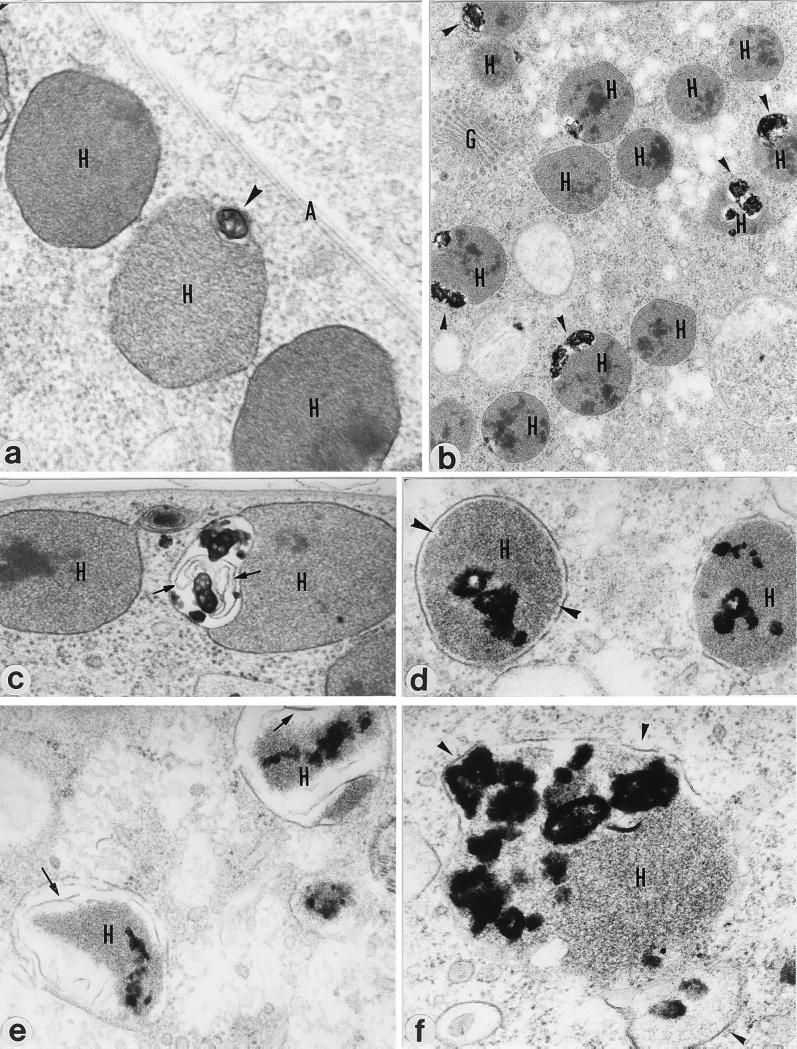

Transmission electron microscopic observations of DAB-treated and untreated T. foetus cells revealed the presence of several ultrastructural alterations in treated cells. The primary effects of DAB occurred in the parasite hydrogenosomes, which, contrary to control cells (Fig. 3a), presented grossly enlarged peripheral vesicles and a heterogeneous electron-dense matrix (Fig. 3b). In some cells the peripheral vesicles presented luminal membrane profiles (Fig. 3c).

FIG. 3.

T. foetus showing normal hydrogenosomes (H) in association with the cytoskeletal axostyle (A). (a) Note the presence of small peripheral vesicles (arrowhead). (b) DAB treatment induced a striking enlargement of the organelle’s peripheral vesicles, which have electron-dense precipitates (arrowheads). Organelles often have a heterogeneous electron density in the matrix. (c) Free membrane profiles (arrows) can be observed in the lumens of hydrogenosome (H) peripheral vesicles in a DAB-treated parasite. (d) Many hydrogenosomes presented matrix retraction and, consequently, displacement from the organelle membranes. (e and f) Compartments (H) that exhibited material rather similar to the hydrogenosomal matrix were observed after DAB treatment. Occasionally, membrane profiles were also observed (panel e, arrow) and the organelle membranes were extraordinarily distorted (panel f, arrowheads). Magnifications: panel a, ×60,000; panel b, ×20,400; panel c, ×48,000; panel d, ×36,000; panel e, ×39,000; panel f, ×75,000.

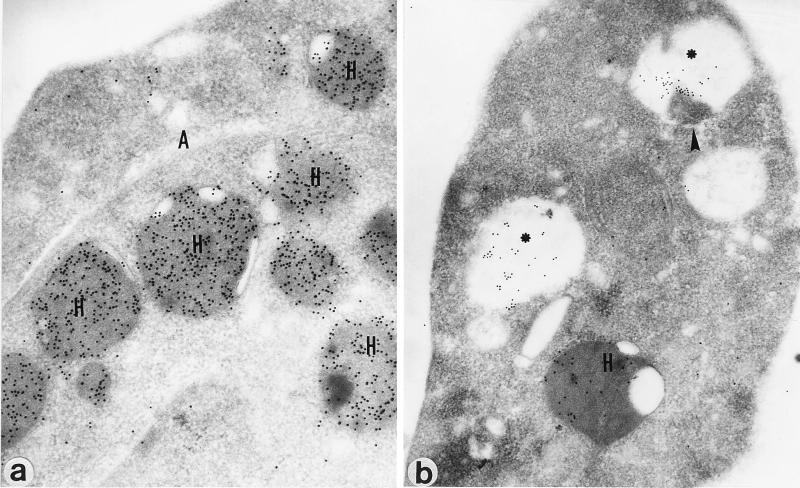

At more advanced stages, the hydrogenosomal matrix was retracted and was therefore displaced from the organelle membranes (Fig. 3d and e), which were frequently drastically damaged (Fig. 3e) and distorted (Fig. 3f). Many cells presented large vesicles containing amorphous, electron-dense material as well as large membrane profiles (data not shown). To confirm these structures (Fig. 3e and f) as degraded hydrogenosomes, immunolocalization studies with β-SCS, a hydrogenosomal marker, were undertaken. Untreated parasites displayed numerous well-preserved immunogold-labeled hydrogenosomes (Fig. 4a), whereas DAB-treated parasites had reduced numbers of these organelles as well as large gold-labeled electron-translucent vesicles that sometimes displayed amorphous electron-dense and immunoreactive material (Fig. 4b).

FIG. 4.

Immunogold detection of β-SCS in sections of control (a) and DAB-treated (b) T. foetus cells embedded in Lowicryl K4M (see Materials and Methods). Note that besides hydrogenosomes (H), the gold labeling was also detected in vesicles (∗) in drug-treated parasites. These vesicles usually presented immunoreactive, amorphous material with an electron density similar to that of the hydrogenosome matrix (arrowhead). A, cytoskeletal axostyle. Magnifications, ×48,000.

DAB-treated T. foetus cells often displayed swollen smooth and rough endoplasmic reticulum cisternae and internalized anterior and recurrent flagellum profiles in association with the marginal lamellae of the undulating membrane (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Polyamines are essential, low-molecular-weight organic cations that have been implicated in the biosynthesis of nucleic acids and proteins (25). In anaerobic parasitic protozoa, ornithine, the precursor of putrescine biosynthesis, is the product of the energy-generating arginine dihydrolase pathway. In T. vaginalis, and possibly other trichomonads, putrescine is not metabolized further and can therefore be considered the end product of an energy-generating pathway. Putrescine may also have a role in buffering of the pH and in oxidative stress, in addition to suppression of the host inflammatory response that ultimately can determine the outcome of infection (28–30).

Exposure of T. foetus to DAB caused a significant increase in the generation time of the parasite. Although the growth of T. foetus was significantly reduced, parasite motility was not affected. This is similar to the cytostatic effects reported for α-dl-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO), an enzyme-activated, irreversible inhibitor of ODC, on T. vaginalis in a semidefined medium (28) and also for trypanosomes (1). In previous studies we found that the growth of T. vaginalis in complex medium was not inhibited by 4 mM DFMO (28). Consequently, DFMO was ineffective in experimental infections, although it was able to block T. vaginalis cytotoxicity in vitro and delay subcutaneous abscess formation (4). In contrast to DFMO, DAB was able to reduce significantly not only the levels of putrescine but also those of other polyamines in a complex medium, resulting in the observed cytostatic effects. Therefore, DAB-related compounds can offer new possibilities for the rational design of novel agents for the treatment of trichomoniasis.

It has previously been shown that T. vaginalis will transport putrescine, spermidine, and spermine with increasing affinity (30). Furthermore, it was demonstrated that spermine uptake occurred via a spermine-putrescine antiporter, which effectively results in the efflux of two molecules of putrescine with the cotransport into the cell of a single spermine molecule, thus maintaining the overall charge balance (30). On the basis of previous studies it is likely that the effect of DAB on the higher polyamines is the result of its inhibition of ODC and the depletion of putrescine, which is then unavailable to cotransport exogenous spermine into the cell. The ability of putrescine to reverse the growth-inhibitory effects of DAB are most likely the result of competition with DAB for transport into the cell and the resultant restoration of the putrescine-spermine antiporter. The fact that double the concentration of putrescine (40 mM) compared to the concentration of DAB (20 mM) is necessary to reverse the effects of DAB supports the idea that putrescine competes with DAB for transport into the cell and by mass action is able to overcome the effects of DAB.

The electron microscopic studies indicate distinct ultrastructural differences in DAB-treated cells, most notably, the presence of large numbers of vesicles which were coincident with the reduction of hydrogenosome numbers. Immunogold analysis with antibodies to β-SCS demonstrated that some of these structures presented amorphous material with electron densities similar to that of the normal hydrogenosomal matrix and were recognized by the anti-β-SCS antibody, confirming that these structures are hydrogenosomal remnants.

Since hydrogenosomes are the only redox organelle in trichomonads and under aerobic conditions these structures generate free radicals such as hydroxyl, peroxide, and superoxide, the antioxidant properties of polyamines such as putrescine (29) and spermine (26) can play a relevant protective role in parasite metabolism. Since the primary structural damage that results from DAB treatment of T. foetus is on the hydrogenosome, it is reasonable to suppose that oxygen free-radical generation under conditions of inhibited polyamine synthesis (Table 1) could lead to lipid peroxidation and protein cross-linking. The hydroxyalkenal molecules that form during polyunsaturated fatty acid peroxidation could then react with free sulfhydryl groups, generating thioether linkage-presenting adducts (23). The resultant protein cross-linking may be responsible at least in part for the hydrogenosomal matrix retraction and electron-dense precipitates observed after DAB treatment. In this regard it is noteworthy that, besides offering protection from oxidative stress, polyamines enhance membrane stability (25). That might explain the hydrogenosomal membrane disorganization observed here.

Interestingly, the inactivation of free sulfhydryl groups under conditions of lipid peroxidation can alter the intracellular Ca2+ distribution (8), and Ca2+ fluxes may be blocked by ODC inhibition (15). In this regard, it is important to mention that the T. foetus hydrogenosomes accumulate Ca2+, particularly within the peripheral vesicles (2, 6). Since the DAB-treated T. foetus cells were also postfixed in the presence of potassium ferricyanide, it is reasonable to suppose that the electron-dense precipitates observed here at least in part comprise Ca2+ deposits. The swollen endoplasmic reticulum cisternae in DAB-treated parasites can also be produced by the impaired Ca2+ homeostasis, since this organelle also accumulates this element in T. foetus (2). Alternatively, this alteration may be due to the dysfunction of osmoregulatory mechanisms and protein synthesis (25).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Fundação Universitária José Bonifácio, and Núcleo de Programas de Excelência (PRONEX/MCT) (to M.A.V.-S. and F.C.S.-F. and by the National Institutes of Health (grant AI-25361 [to N.Y.] and grant AI-27857 [to P.J.J.]). I. A. Reis was the recipient of an M.Sc. scholarship from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico.

We thank A. Martiny for valuable help with the micrographs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bacchi C J, Yarlett N. Polyamine metabolism. In: Marr J J, Muller M, editors. Biochemistry and molecular biology of parasites. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1995. pp. 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benchimol M, De Souza W. Fine structure and cytochemistry of the hydrogenosome of Tritrichomonas foetus. J Protozool. 1983;30:422–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1983.tb02942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendayan M, Naci A, Kan F W K. Effect of tissue processing on colloidal gold cytochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem. 1987;35:983–996. doi: 10.1177/35.9.3302022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bremner A F, Coombs G H, North M J. Antitrichomonal activity of a α-difluoromethylornithine. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987;20:405–411. doi: 10.1093/jac/20.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen K C S, Amsel R, Eschenbach D A, Holmes K K. Biochemical diagnosis of vaginitis: determination of diamines in vaginal fluid. J Infect Dis. 1982;145:337–345. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Souza W, Benchimol M. Electron spectroscopic imaging of calcium in the hydrogenosomes of Tritrichomonas foetus. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1988;20:619–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diamond L S. The establishment of various trichomonads of animals and man in axenic cultures. J Parasitol. 1957;43:488–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffin D S, Segall H J. Effects of the pyrrolizidine alkaloid senecionine and the alkenals trans-4-OH-hexenal and trans-2-hexenal on intracellular calcium compartmentation in isolated hepatocytes. Biochem J. 1989;38:391–397. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guevara-Olvera L, Calvo-Mendez C, Ruiz-Herrera J. The role of polyamine metabolism in dimorphism of Yarrowia lipolytica. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;193:485–493. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-3-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guzman-de-Pena D, Aguirre J, Ruiz-Herrera J. Correlation between the regulation of sterigmatocystin biosynthesis and asexual and sexual sporulation in Emericella nidulans. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1998;73:199–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1000820221945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guzman-de-Pena D, Ruiz-Herrera J. Relationship between aflatoxin biosynthesis and sporulation in Aspergillus parasiticus. Fungal Genet Biol. 1997;21:198–205. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1996.0945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heine P, McGregor J A. Trichomonas vaginalis: a reemerging pathogen. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1993;36:137–144. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199303000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lahti C J, D’Oliveira C E, Johnson P J. β-Succinyl-coenzyme A synthetase from Trichomonas vaginalis is a soluble hydrogenosomal protein with an amino-terminal sequence that resembles mitochondrial presequences. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6822–6830. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.21.6822-6830.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez J P, Lopez-Ribot J L, Gil M L, Sentandreu R, Ruiz-Herrera J. Inhibition of the dimorphic transition of Candida albicans by the ornithine decarboxylase inhibitor 1,4-diaminobutanone: alterations in the glycoprotein composition of the cell wall. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:1937–1943. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-10-1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marton L J, Morris D R. Molecular and cellular functions of the polyamines. In: McCann P P, Pegg A E, Sjoerdsma A, editors. Inhibition of polyamine metabolism: biological significance and basis for new therapies. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1987. pp. 79–105. [Google Scholar]

- 16.North M J, Lockwood B C, Bremner A F, Coombs G H. Polyamine biosynthesis in trichomonads. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1986;19:241–249. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(86)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pegg A E. Recent advances in biochemistry of polyamines in eukaryotes. Biochem J. 1986;234:249–262. doi: 10.1042/bj2340249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pegg A E. Polyamine metabolism and its importance in neoplastic growth and as target for chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 1988;48:759–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pegg A E, McCann P P. Polyamine metabolism and function. Am J Physiol. 1982;243(Cell Physiol. 12):C212–C221. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1982.243.5.C212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrin D, Delgaty K, Bhatt R, Garber G. Clinical and microbiological aspects of Trichomonas vaginalis. Clin Microbiol Veter. 1998;11:300–337. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.2.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhyan J C, Stackhouse L L, Quinn W J. Fetal and placental lesions in bovine abortion due to Tritrichomonas foetus. Vet Pathol. 1988;25:350–355. doi: 10.1177/030098588802500503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sans-Blas G, San-Blas F, Sorais F, Moreno B, Ruiz-Herrera J. Polyamines in growth and dimorphism of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Arch Microbiol. 1996;166:411–413. doi: 10.1007/BF01682988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schauenstein E, Esterbauer H. Formation and properties of reactive aldehydes. Ciba Found Symp. 1978;67:225–244. doi: 10.1002/9780470720493.ch15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens L, McKinnon I M. The effect of 1,4-diaminobutanone on the stability of ornithine decarboxylase from Aspergillus nidulans. Biochem J. 1977;166:635–637. doi: 10.1042/bj1660635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tabor C W, Tabor H. 1,4-Diaminobutane (putrescine), spermidine, and spermine. Annu Rev Biochem. 1976;45:285–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.45.070176.001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tadolini B. Polyamine inhibition of lipoperoxidation. Biochem J. 1988;249:33–36. doi: 10.1042/bj2490033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.World Health Organization. Trichomoniasis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yarlett N. Polyamine biosynthesis and inhibition in Trichomonas vaginalis. Parasitol Today. 1988;4:357–360. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(88)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yarlett N, Bacchi C J. Effect of dl-α-difluoromethylornithine on polyamine synthesis and interconversion in Trichomonas vaginalis grown in a semidefined medium. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1988;31:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(88)90139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yarlett N, Bacchi C J. Polyamine metabolism in anaerobic protozoa. In: Coombs G H, North M J, editors. Biochemical protozoology. London, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis; 1991. pp. 458–468. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yarlett N, Bacchi C J. Parasite polyamine metabolism: targets for chemotherapy. Biochem Soc Trans. 1994;22:875–880. doi: 10.1042/bst0220875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yarlett N, Martinez M P, Moharrami M A, Tachezy J. The contribution of the arginine dihydrolase pathway to energy metabolism by Trichomonas vaginalis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;78:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02616-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]