Abstract

A Klebsiella pneumoniae strain resistant to oxyimino cephalosporins was cultured from respiratory secretions of a patient suffering from nosocomial pneumonia in Kiel, Germany, in 1997. The isolate harbors a bla resistance gene located on a transmissible plasmid. An Escherichia coli transconjugant produces a β-lactamase with an isoelectric point of 7.7 and a resistance phenotype characteristic of an AmpC (class 1) β-lactamase except for low MICs of cephamycins. The bla gene was cloned and sequenced. It encodes a protein of 386 amino acids with the active site serine of the S-X-X-K motif at position 64, as is characteristic for class C β-lactamases. Multiple alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence with 21 other AmpC β-lactamases demonstrates only very distant homology, reaching at maximum 52.3% identity for the chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase of Serratia marcescens SR50. The β-lactamase of K. pneumoniae KUS represents a new type of AmpC-class enzyme, for which we propose the designation ACC-1 (Ambler class C-1).

Resistance of bacterial pathogens to β-lactam antibiotics is frequently mediated by β-lactamases. bla genes located on transmissible plasmids have been observed for Ambler class A β-lactamases since 1963 (TEM-1 [15]). In contrast, bla genes coding for class C β-lactamases (class 1 in the classification by Bush et al. [12]) are primarily chromosomally located. Plasmid-borne transmissible ampC genes were first discovered about 25 years after the plasmidic class A bla genes (MIR-1 in 1988 [32] and CMY-1 in 1989 [4]). Since then, plasmid-borne ampC genes have been detected in many regions of the world (2, 6, 8, 10, 11, 16, 18, 19, 22, 27, 37, 38). They contribute to the spread of multidrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and other Enterobacteriaceae.

We report the first plasmid-encoded AmpC-type β-lactamase originating in Germany (Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein, 1997). The gene designated blaACC-1 (Ambler class C) has a unique nucleotide sequence with only distant homology of its deduced amino acid sequence with known AmpC β-lactamases and an unusual resistance phenotype due to its low activity against cephamycins. It therefore presents a new and so far solitary type among the AmpC β-lactamases.

(Part of this work was presented at the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Diego, Calif., 24 to 27 September 1998.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case history. (i) Clinical background.

K. pneumoniae KUS was isolated in 1997 from a 31-year-old male patient. The patient was diabetic and had been admitted to the Kiel University Hospital because of convulsive seizures due to hypo-osmolaric coma. He developed multiple pulmonary complications that necessitated mechanical ventilation for a total of 8 weeks. After 3 months of hospitalization, the patient had recovered and was transferred to a rehabilitation center.

(ii) Bacteriological findings and antibiotic therapy.

Early onset pneumonia was caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, which was eradicated by therapy with tazobactam. Consecutively, a late-onset pneumonia caused by K. pneumoniae was treated by combined antibiotic therapy of imipenem plus ciprofloxacin for 3 weeks. As K. pneumoniae was not eradicated, therapy was changed to meropenem plus ciprofloxacin and continued for another 20 days. Although K. pneumoniae persisted in throat and skin cultures, antibiotic treatment was discontinued as signs and symptoms of inflammation were no longer diagnosed.

Bacterial strains and vectors.

Strains and vectors used in this study are characterized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Plasmid | Characteristics | pI(s) of β-lactamases |

|---|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae KUS | pMVP-8 | Clinical isolate from sputum, Kiel, Germany | 5.4, 7.7 |

| E. coli C600 | Rifampin resistant | None | |

| E. coli MV1190 | lac− | None | |

| E. coli C600 | pMVP-8 | Transconjugant of KUS | 5.4, 7.7 |

| E. coli MV1190 | pBC | Chloramphenicol-resistant cloning vector | None |

| E. coli MV1190 | Transformant of KUS containing a 2.3-kb fragment cloned into pBC | 7.7 |

Antibiotics.

The following antibiotics were obtained from the indicated manufacturers: ceftazidime (Cascan GmbH & Co. KG, Wiesbaden, Germany); cefotaxime, cefpirome, and tetracycline (Hoechst AG, Frankfurt on the Main, Germany); clavulanate and BRL 42715 (SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, London, United Kingdom); sulbactam (Pfizer, Karlsruhe, Germany); tazobactam (Lederle, Münster, Germany); cefepime and aztreonam (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Munich, Germany); cefoxitin and imipenem (Merck Sharp & Dohme, Munich, Germany); cefoteten and meropenem (Zeneca GmbH, Plankstadt, Germany); Ro 47-8284, sulfamethoxazole, and trimethoprim (Hoffmann-La Roche Inc., Basel, Switzerland); moxalactam and tobramycin (Lilly Deutschland GmbH, Bad Homburg, Germany); flomoxef (Shionogi, Düsseldorf, Germany); and chloramphenicol (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). Combinations of ceftazidime or cefotetan with β-lactamase inhibitors were used at the following proportions: clavulanate, 1/4; sulbactam, 1/2; tazobactam, 1/8; and BRL 42715 (14) and Ro 47-8284 (53) at a constant concentration of 4 μg/ml.

Susceptibility testing.

For determination of MICs, a standard procedure described by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards was followed (29). E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as the MIC reference strain.

Transfer of resistance determinants.

The procedure for conjugation experiments was described previously (8). Transconjugants were selected on MacConkey agar (Unipath GmbH, Wesel, Germany) supplemented with rifampin (128 μg/ml) and ceftazidime (2 μg/ml).

Inducibility of the synthesis of ACC-1.

Inducibility of ACC-1 production was tested by a double disk test with cefoxitin as the inducing compound. An Enterobacter cloacae strain producing an inducible AmpC β-lactamase was used as a reference.

Identification of the isoelectric point (pI) of ACC-1.

Sonicates of strains were prepared as described previously (5). For isoelectric focusing of their β-lactamases, the procedure of Matthew et al. (28) was modified (5). After isoelectric focusing, the polyacrylamide gel was covered by a 0.75% tryptic soy agar (TSA) (Difco, Augsburg, Germany) overlay containing the β-lactam to be tested for inactivation and incubated for 2 h at 35°C. A second TSA layer with a strain (1.2 × 107 CFU/ml) susceptible to the β-lactam used was then applied. After overnight incubation at 35°C, growth of the indicator strain on the gel identifies the position at which the β-lactam had been inactivated.

Kinetic analysis of the ACC-1 β-lactamase.

The ACC-1 β-lactamase for the kinetic analysis was obtained from the transformant strain MV1190 T+. Bacteria from a 1-liter overnight culture of tryptic soy broth (TSB) supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin/ml were harvested by centrifugation and washed with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of 0.2 M sodium acetate, and subjected to five freeze-thaw cycles. ACC-1 was partially purified by Sephadex G-100 chromatography in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Fractions containing nitrocefin-hydrolyzing activity were precipitated with 90% ammonium sulfate; pellets were resuspended in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and dialyzed in the same buffer overnight at 4°C. Initial hydrolysis rates were measured on a Shimadzu UV-1601 spectrophotometer at 25°C in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Km and Vmax values were obtained by using Lineweaver-Burk, Eadie-Hofstee, Hanes-Woolf, and direct linear plot analyses. Substrates were assayed on at least two separate days, with cephaloridine included as a reference each day. Due to the slow hydrolysis rate detected with ceftazidime, a Ki value was determined: cephaloridine was used as the substrate and ceftazidime was used as the competing substrate following a 5-min preincubation of enzyme with ceftazidime to establish a steady state.

Plasmid DNA preparation.

Cells were grown overnight in 150 ml of TSB (Oxoid, Wesel, Germany) supplemented with ceftazidime (1 μg/ml). DNA preparation was performed by alkaline lysis (9). Plasmid DNA in the lysate was purified with an anion exchange column (tip 100; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the recommendations of the manufacturer.

Cloning and sequencing of the blaACC-1 gene.

Cloning experiments were performed by following standard procedures (35). The plasmid DNA of an E. coli transconjugant strain carrying the blaACC-1 gene was partially digested with SauIIIa and subsequently ligated into vector pBC. DNA fragments were purified with the QIAquick purification kit (Qiagen). For ligation, vector and insert DNA were mixed in ratios of 1:3 and 1:6. Ligation buffer and 1 U of T4 ligase were added, and the mixture was incubated at 16°C overnight. The ligase was then inactivated at 70°C for 10 min. Cells of E. coli MV1190 were transformed by electroporation. Transformants were selected on TSA containing 2 μg of ceftazidime/ml, 20 μg of X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside)/ml, and 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). After overnight incubation at 37°C, white colonies were isolated and screened for inserts in vector pBC. From two transformants, inserts of 2.0 or 2.3 kb were sequenced. Sequencing was performed with consecutive primers by the dideoxy chain termination procedure of Sanger (36) with an automatic sequencer (model 373A; Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany).

Sequence analysis.

β-Lactamase relatedness was investigated by comparison with EMBL and Swissprot databases (Fasta). Multiple alignment was calculated with Clustal V (20, 21).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper will appear in the EMBL database under accession no. AJ133121.

RESULTS

Phenotypic characterization of the ACC-1 β-lactamase of K. pneumoniae KUS.

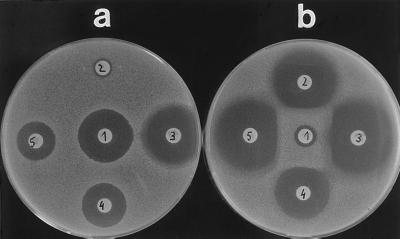

The blaACC-1 gene was conjugated into an E. coli recipient strain together with the blaTEM-1 gene. The expression of the blaACC-1 gene in transconjugant and transformant strains significantly increased the MICs (equal to or above fourfold) of a variety of different β-lactam structures, namely oxyimino cephalosporins (ceftazidime and cefotaxime, 64- to 128-fold), 7-methoxy-cephalosporins (cefotetan, moxalactam, and flomoxef, four- to eightfold), dipolar cephalosporins (cefepime and cefpirome, four- to eightfold), the monobactam aztreonam (eightfold), and piperacillin (512-fold in the transconjugant, 64-fold in the transformant). No increase of MICs by acquisition of the blaACC-1 gene was detectable against cefoxitin, the 6-methoxy-penicillin temocillin, and the carbapenems (Table 2). MICs of transformants were reduced only by β-lactamase inhibitors active against class C β-lactamases (BRL 42715 [14], Ro 47-8284 [33], 8- to 32-fold). Tazobactam reduced the MICs of piperacillin of the wild type and the transconjugant strains but not of the transformant strain, as blaTEM-1 was not cloned into the transformant. Inducibility of ACC-1 synthesis could not be demonstrated by a double-disk test, in which AmpC production of an Enterobacter cloacae was induced by cefoxitin (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Antibiotic susceptibilities of the wild-type K. pneumoniae KUS, the transconjugant E. coli C600 R+, the transformant E. coli MV1190 T+, and the recipient E. coli C600 R−

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) for:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type K. pneumoniae KUS | Transconjugant E. coli C600 R+ | Recipient E. coli C600 R− | Transformant E. coli MV1190 T+ | Host E. coli MV1190 T− | |

| Ceftazidime | 64 | 16 | 0.13 | 32 | 0.06 |

| Plus clavulanate | 32 | 16 | 0.13 | 16 | 0.06 |

| Plus sulbactam | 32 | 16 | 0.13 | 16 | 0.06 |

| Plus tazobactam | 32 | 16 | 0.13 | 32 | 0.06 |

| Plus BRL 42715 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 1 | 0.06 |

| Plus Ro 47-8284 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 0.5 | 0.06 |

| Cefotaxime | 16 | 4 | 0.06 | 8 | 0.03 |

| Cefotetan | 4 | 1 | 0.13 | 2 | 0.06 |

| Plus clavulanate | 4 | 1 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.06 |

| Plus sulbactam | 4 | 1 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.06 |

| Plus tazobactam | 4 | 1 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.06 |

| Plus BRL 42715 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.06 |

| Plus Ro 47-8284 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.06 |

| Cefoxitin | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Moxalactam | 1 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.13 |

| Flomoxef | 2 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.13 |

| Cefpirome | 4 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.03 |

| Cefepime | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.016 | 0.25 | 0.016 |

| Aztreonam | 2 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.06 |

| Piperacillin | 512 | 256 | 0.5 | 32 | 0.5 |

| Plus tazobactam | 64 | 16 | 0.5 | 32 | 0.5 |

| Temocillin | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Imipenem | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.25 |

| Meropenem | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

FIG. 1.

Double-disk test to check inducibility of ACC-1 synthesis. (a) Inducibility test with K. pneumoniae KUS. (b) Inducibility test with Enterobacter cloacae WG7250. Disks: 1, cefoxitin; 2, ceftazidime; 3, cefotaxime; 4, cefotetan; 5, aztreonam.

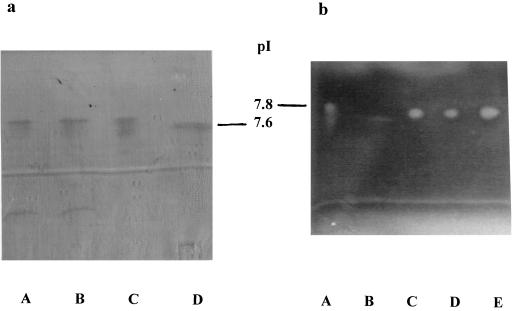

Isoelectric focusing of crude homogenates demonstrated two bands at pIs of 5.4 and 7.7 for the K. pneumoniae KUS wild type and the transconjugant strain and only one band at 7.7 for the transformant strain (Fig. 2A). Ceftazidime, cefotetan, and cefoxitin were inactivated only at the pI 7.7 band as demonstrated by growth of the susceptible indicator strain (Fig. 2B) at this position. So the hydrolytic activity of the β-lactamase ACC-1 was assigned to the band focusing at pI 7.7.

FIG. 2.

Isoelectric focusing of β-lactamase ACC-1. The ACC-1 producing wild-type, transconjugant, and transformant strains revealed a band at a pI lower than 7.8 (SHV-4) but slightly above 7.6 (SHV-2), at about 7.7 (a). This band was able to inactivate ceftazidime, as shown by a bioassay (b). Lanes for panel a: A, K. pneumoniae KUS producing ACC-1; B, E. coli C600 R+ producing ACC-1; C, E. coli DH5α T+ producing ACC-1; D, E. coli R+ producing SHV-2. Lanes for panel b: A, E. coli R+ producing SHV-4; B, E. coli R+ producing SHV-2; C, K. pneumoniae KUS producing ACC-1; D, E. coli C600 R+ producing ACC-1; E, E. coli DH5α T+ producing ACC-1.

Kinetic data of the ACC-1 β-lactamase.

Measurable hydrolysis rates were not observed for cephalosporins except for cephaloridine and nitrocefin; however, in a competitive assay, slow hydrolysis of ceftazidime was detectable (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Kinetic data for ACC-1

| Substrate | Vmax (nmol of substrate/ min/μg of protein) | Relative Vmax | Km (μM) | Vmax/Km |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cephaloridine | 30.7 ± 3.0 | 100 | 122 ± 16 | 0.25 |

| Nitrocefin | 63.7 ± 2.2 | 208 | 28 ± 3.7 | 2.3 |

| Piperacillin | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 0.55 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 0.12 |

| Ceftazidime | <0.025 | ≤0.1 | 17a | <0.01 |

| Cefotaxime | <0.01 | <0.02 | NDb | ND |

| Cefotetan | <0.001 | <0.01 | ND | ND |

| Cefoxitin | <0.002 | <0.01 | ND | ND |

Ki value was determined by using cephaloridine as substrate.

Rates were too slow to determine a Km from steady-state hydrolysis rates.

Characterization of the blaACC-1 gene.

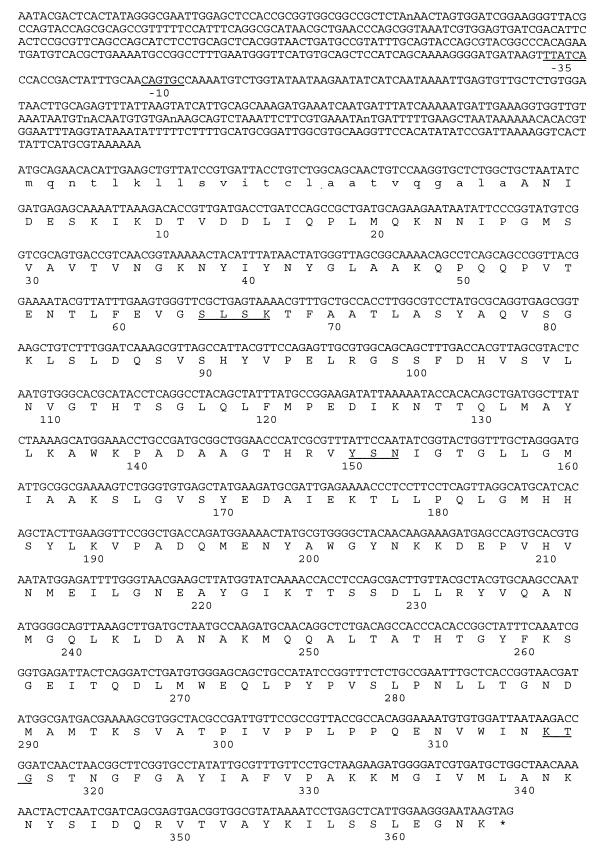

A 2,263-bp DNA fragment excised from plasmid DNA of a transconjugant strain was cloned into E. coli MV1190 (pBC) and sequenced. An open reading frame of 1,161 nucleotides encoding a protein of 386 amino acids could be identified (Fig. 3). The deduced amino acid sequence carries the catalytic residues S-X-X-K (here serine-leucine-serine-lysine) with the initial serine at position 64 as is typical of class C β-lactamases, the motif Y-S-N (tryptophan-serine-asparagine) at position 150, and the K-T-G (lysine-threonine-glycine) motif at position 315. In the 639-bp nucleotide sequence upstream of the start codon no ampR motif could be detected. This finding is concordant with the noninducibility of ACC-1 β-lactamase synthesis.

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide sequence of the blaACC-1 gene (pMVP-8). The deduced amino acid sequence of ACC-1 is shown in the line below the nucleotide triplets. Amino acids of the signal peptide are written in small letters. The β-lactamase active site S-L-S-K, the conserved triad K-T-G, and the class C-typical motif Y-X-N are underlined. The putative −10 and −35 promoter regions upstream of the start codon are underlined. The asterisk indicates the stop codon.

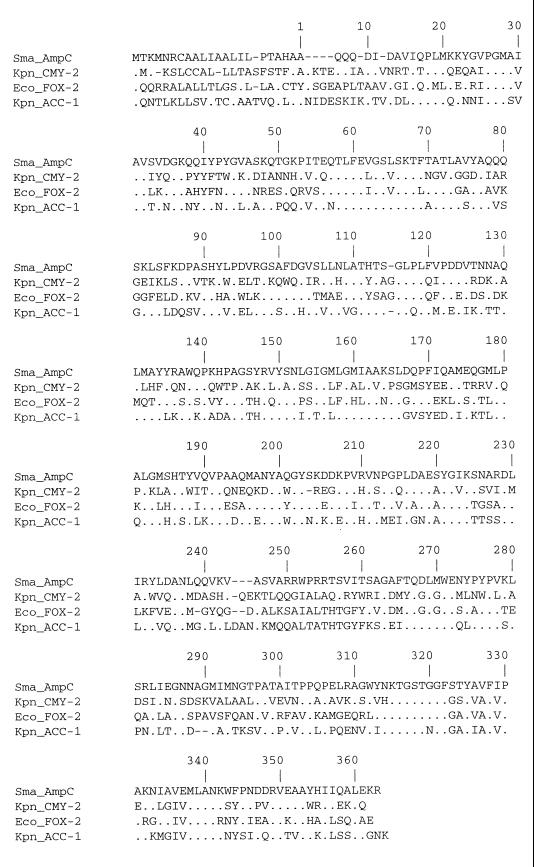

The deduced amino acid sequence of the enzyme was compared with that of other chromosomal or plasmid-encoded AmpC β-lactamases. The percentage of amino acid identity was below 50% for all β-lactamases included except for the chromosomal Serratia marcescens SR50 AmpC β-lactamase (31) with 52.3% (Table 4). Multiple alignment of the amino acid sequence of AmpC β-lactamases demonstrates enzyme-specific amino acid fingerprints as well as amino acid positions conserved in all enzymes (Fig. 4).

TABLE 4.

Identity of amino acid sequences of ACC-1 to other class C β-lactamases

| β-Lactamase (reference)a | % Identity with:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC-1 | S. marcescens AmpC | FOX-2 | CMY-1 | P. aeruginosa AmpC | C. freundii AmpC | E. coli AmpC | Enterobacter cloacae AmpC | M. morganii AmpC | |

| ACC-1 | 100 | 52.3 | 46.4 | 43.9 | 43.7 | 39.5 | 38.8 | 37.9 | 37.2 |

| S. marcescens AmpC (31) | 100 | 45.6 | 44.5 | 44.9 | 38.3 | 38.9 | 41.5 | 39.8 | |

| FOX-2 (8) | 100 | 74.9 | 53.7 | 41.8 | 42.0 | 43.9 | 46.3 | ||

| CMY-1 (7) | 100 | 54.4 | 41.2 | 41.1 | 43.1 | 43.5 | |||

| P. aeruginosa AmpC (26) | 100 | 41.9 | 42.7 | 44.1 | 54.4 | ||||

| C. freundii AmpC (25) | 100 | 76.7 | 73.2 | 57.2 | |||||

| E. coli AmpC (24) | 100 | 69.8 | 57.9 | ||||||

| Enterobacter cloacae AmpC (17) | 100 | 55.1 | |||||||

| M. morganii AmpC (1) | 100 | ||||||||

One representative of each group of the seven AmpC types (Fig. 5) was selected for comparison.

FIG. 4.

Multiple alignment of amino acid sequences of the chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase of S. marcescens (32), CMY-2 (6), FOX-2 (8), and ACC-1 (this study).

DISCUSSION

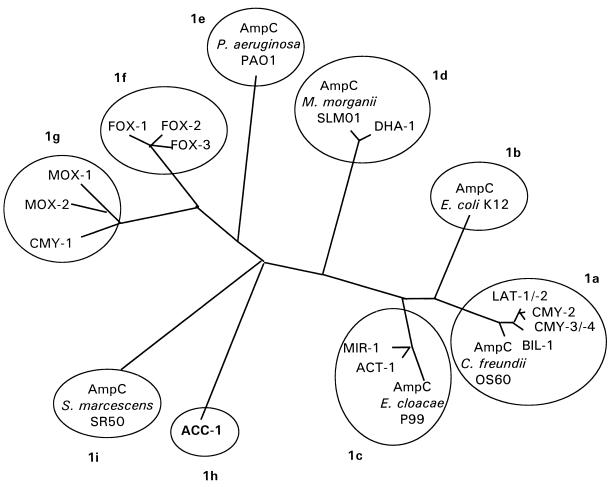

The majority of the plasmid-borne ampC genes have been described in K. pneumoniae (6, 7, 10, 11, 18, 19, 22, 23, 37). Many among them have close homology with chromosomal AmpC β-lactamases, e.g., of Citrobacter freundii (6, 18, 37), or Enterobacter cloacae (11, 23). So K. pneumoniae may have acquired these genes from other species at sites where K. pneumoniae lives close to the ecological neighborhood of ampC-carrying organisms, e.g., other Enterobacteriaceae, namely in the intestine. The degree of homology between some of the chromosomal and the plasmid-encoded β-lactamases appears to be high enough to assume a phylogenetic lineage. There remain, however, both chromosomal and plasmid-mediated AmpC enzymes without a currently identified counterpart, e.g., the chromosomal β-lactamase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (26) or the plasmid-encoded β-lactamases forming the CMY-1 cluster (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Dendrogram for 22 AmpC (group 1) β-lactamases (calculated by Clustal V using the neighbor-joining method of Saitou and Nei [34]). According to the identity of their amino acid sequences with CMY-2, the group 1 β-lactamases might be subclassified into 1a to 1i.

The enzyme described here as well is highly dissimilar to known AmpC β-lactamases (Table 4, Fig. 5). The closest amino acid sequence homology of the mature enzyme is with the chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase of S. marcescens (31). The degree of homology is very low (52.3%). There are altogether 181 amino acid substitutions between both enzymes (92 conservative, 89 nonconservative). Thus, the phylogenetic relationship of this enzyme to others remains unclear. The phenotypic characteristics of the β-lactamase (antibiotic susceptibilities and pI) as well indicate a distinct type of AmpC β-lactamase. In particular, the resistance phenotype expressed by blaACC-1-carrying strains is unusual among AmpC-type β-lactamases, as cefoxitin appears to be a poor substrate. The MIC of cefoxitin for transformants is elevated by a factor of only two, in comparison with a 64- to 128-fold increase for transformants producing CMY-1 (4), CMY-2 (6), FOX-2 (8), or ACT-1 (11). Accordingly, inactivation of cefoxitin as determined in the bioassay is lower in comparison with ceftazidime. To obtain an equivalent effect, the same homogenate has to be used undiluted (for cefoxitin) or at a dilution of 1:32 (for ceftazidime), indicating a good correlation between MICs and the inactivation of these substrates. This reaction proceeds at a rather low rate, while the affinity for binding appears to be high. Slow hydrolysis of cephamycins and third generation cephalosporins has been observed for chromosomal cephalosporinases (30).

The low inactivation level of cefoxitin by ACC-1 stimulates speculation on the role of amino acids at specific positions in the hydrolysis of cephamycins. We identified 11 positions with amino acids identical in all AmpC β-lactamases hydrolyzing cephamycins at which ACC-1 carries a different amino acid. Five of them (P 118 Q, Y 135 L, I 155 T, P 213 M, and G 214 E) are nonconservative exchanges and may be associated with structural modifications which impair the hydrolysis of methoxy-cephalosporins. The functional significance of the five nonconservative amino acid exchanges by site-directed mutagenesis is being analyzed.

The ensemble of phenotypic and genetic characteristics indicates that the enzyme produced by K. pneumoniae KUS represents a new type within class C β-lactamases. Nomenclature of plasmid-encoded AmpC β-lactamases—similar to that of TEM-β-lactamases (13)—has not been systematically standardized. They were designated mainly by their preferred substrates (the MOX, FOX, and CMY enzymes) or by the place where strains producing them were first isolated (MIR-1 or BIL-1). For the new enzyme, neither a preferred substrate nor an outbreak of infections caused by K. pneumoniae KUS was observed. We propose the designation Ambler class C, number 1 (ACC-1).

At this time, the number of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases that has been described is 17. For their classification, phenotypic characteristics such as preferred substrates and inhibitory compounds are of less discriminatory power than for class A enzymes (e.g., low MIC of ceftazidime of CMY-1, or of cefoxitin of ACC-1). However, the amino acid sequence data are available for all of them. This allows a genetic subclassification as proposed in Fig. 5. This tentative subclassification follows the degree of amino acid sequence identity with CMY-2 (3). Maximum discrimination of β-lactamases could be based on amino acid fingerprints. Positions in the enzyme occupied by amino acids not found in any other AmpC β-lactamase may be used to define the molecular individuality of the respective enzyme. The positions occupied with a unique amino acid describe the sequence individuality for an enzyme. CMY-2 and ACC-1 are located at the extreme ends on this scale. ACC-1 carries amino acids not found in any other AmpC β-lactamase at 83 positions. So, this β-lactamase is most distant from the comparable enzymes.

The future evolution of plasmid-encoded AmpC β-lactamases might proceed at a rate comparable to that of the last decade where on average 1.5 new enzymes were identified per year (3). The novel β-lactamases were either closely related to already described enzymes (CMY-2 or CMY-1 groups) or solitary types (DHA-1, ACC-1). The selection of strains producing AmpC β-lactamases may be more effective in comparison with ESBL due to their additional resistance to cephamycins (except ACC-1). So, monitoring for AmpC β-lactamases by including a cephamycin in the panel of antibiotics used for susceptibility testing is of major clinical relevance. There is a risk of accumulation of additional resistance mechanisms in one strain, e.g., impaired expression of outer membrane proteins or enhanced efflux, which may add up to pleiotropic resistance including non-β-lactams (11).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Anne-Marie Queenan for performing the kinetic analysis of the ACC-1 β-lactamase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnaud G, Arlet G, Danglot C, Philippon A. Cloning and sequencing of the gene encoding the AmpC β-lactamase of Morganella morganii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;148:15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnaud G, Arlet G, Verdet C, Gaillot O, Lagrange P H, Philippon A. Salmonella enteritidis: AmpC plasmid-mediated inducible β-lactamase (DHA-1) with an ampR gene from Morganella morganii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2352–2358. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauernfeind A, Chong Y, Lee K. Plasmid-encoded AmpC β-lactamases: how far have we gone 10 years after their discovery? Yonsei Med J. 1998;39:520–525. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1998.39.6.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauernfeind A, Chong Y, Schweighart S. Extended broad spectrum β-lactamase in Klebsiella pneumoniae including resistance to cephamycins. Infection. 1989;17:316–321. doi: 10.1007/BF01650718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauernfeind A, Grimm H, Schweighart S. A new plasmidic cefotaximase in a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli. Infection. 1990;18:294–298. doi: 10.1007/BF01647010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauernfeind A, Stemplinger I, Jungwirth R. Characterization of the plasmidic β-lactamase CMY-2, which is responsible for cephamycin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:221–224. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauernfeind A, Stemplinger I, Jungwirth R, Wilhelm R, Chong Y. Comparative characterization of the cephamycinase blaCMY-1 gene and its relationship with other β-lactamase genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1926–1930. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauernfeind A, Wagner S, Jungwirth R, Schneider I, Meyer D. A novel class C β-lactamase (FOX-2) in Escherichia coli conferring resistance to cephamycins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2041–2046. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyer-Mariotte S, Raskine L, Hanau B, Philippon A, Sanson-Le Pors M J, Arlet G. Abstracts of the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Novel plasmid-mediated AmpC-type β-lactamase (MOX-2) in a clinical isolate of Klebsiella pneumoniae, abstr. C7; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradford P A, Urban C, Mariano N, Projan S J, Rahal J J, Bush K. Imipenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with the combination of ACT-1, a plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase, and the loss of an outer membrane protein. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:563–569. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bush K, Jacoby G A, Medeiros A A. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1211–1233. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bush K, Jacoby G. Nomenclature of TEM β-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39:1–3. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman K, Griffin D R J, Page J W J, Upshon P A. In vitro evaluation of BRL 42715, a novel β-lactamase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1580–1587. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Datta N, Kontomichalou P. Penicillinase synthesis controlled by infectious R factors in Enterobacteriaceae. Nature (London) 1965;208:239–241. doi: 10.1038/208239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fosberry A P, Payne D J, Lawlor E J, Hodgson J E. Cloning and sequencing analysis of blaBIL-1, a plasmid-mediated class C β-lactamase gene in Escherichia coli BS. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1182–1185. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.5.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galleni M, Lindberg F, Normark S, Cole S, Honoré N, Joris B, Frère J-M. Sequence analysis of three Enterobacter cloacae ampC β-lactamase genes and their products. J Biochem. 1988;250:753–760. doi: 10.1042/bj2500753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gazouli M, Tzouvelekis L S, Prinarakis E, Miriagou V, Tzelepi E. Transferable cefoxitin resistance in enterobacteria from Greek hospitals and characterization of a plasmid-mediated group 1 β-lactamase (LAT-2) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1736–1740. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez Leiza M, Perez-Diaz J C, Ayala J, Casellas J M, Martinez-Beltran J, Bush K, Baquero F. Gene sequence and biochemical characterization of FOX-1 from Klebsiella pneumoniae, a new AmpC-type plasmid-mediated β-lactamase with two molecular variants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2150–2157. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins D G, Bleasby A J, Fuchs R. CLUSTAL V: improved software for multiple sequence alignment. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992;8:189–191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins D G, Sharp P M. Fast and sensitive multiple sequence alignments on a microcomputer. CABIOS. 1989;5:151–153. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/5.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horii T, Arakawa Y, Ohta M, Sugiyama T, Wacharotayankum R, Ito H, Kato N. Characterization of a plasmid-borne and constitutively expressed blaMOX-1 gene encoding ampC-type β-lactamase. Gene. 1994;139:93–98. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90529-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacoby G A, Tran J. Sequence of the MIR-1 β-lactamase gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1759–1760. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaurin B, Grundström T. AmpC cephalosporinase of Escherichia coli K12 has a different evolutionary origin from that of β-lactamases of the penicillin type. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4897–4901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindberg F, Normark S. Sequence of the Citrobacter freundii OS60 chromosomal ampC β-lactamase gene. Eur J Biochem. 1986;156:441–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lodge J M, Minchin S D, Piddock L J V, Busby S J W. Cloning, sequencing and analysis of the structural gene and regulatory region of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa chromosomal ampC β-lactamase. Biochem J. 1990;272:627–631. doi: 10.1042/bj2720627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marchese A, Arlet G, Schito G C, Lagrange P H, Philippon A. Characterization of FOX-3, an AmpC-type plasmid-mediated β-lactamase from an Italian isolate of Klebsiella oxytoca. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:464–467. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthew M, Harris A M, Marshall M J, Ross G W. The use of analytical isoelectric focussing for detection and identification of β-lactamases. J Gen Microbiol. 1975;88:169–178. doi: 10.1099/00221287-88-1-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed., vol. 17, no. 2. Approved standard M7-A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nayler J H C. Resistance to β-lactams in Gram-negative bacteria: relative contributions of β-lactamase and permeability limitations. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987;19:713–732. doi: 10.1093/jac/19.6.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nomura K, Yoshida T. Nucleotide sequence of the Serratia marcescens SR50 chromosomal ampC β-lactamase gene. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;70:295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb13992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papanicolaou G A, Medeiros A A, Jacoby G A. Novel plasmid-mediated β-lactamase (MIR-1) conferring resistance to oxyimino- and α-methoxy β-lactams in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:2200–2209. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.11.2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richter H G, Angehrn P, Hubschwerlen C, Kania M, Page M G, Specklin J L, Winkler F K. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of 2 beta-alkenyl penam sulfone acids as inhibitors of β-lactamases. J Med Chem. 1996;39:3712–3722. doi: 10.1021/jm9601967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tzouvelekis L S, Tzelepi E, Mentis A F, Tsakaris A. Identification of a novel plasmid-mediated β-lactamase with chromosomal cephalosporinase characteristics from Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31:645–654. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.5.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verdet C, Arlet G, Ben Redjeb S, Ben Hassen A, Lagrange P H, Philippon A. Characterization of CMY-4, an AmpC-type plasmid-mediated β-lactamase in a Tunisian clinical isolate of Proteus mirabilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;169:235–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]