Abstract

Fathers’ high-quality parenting behaviors support the development of positive social and emotional adjustment in children. However, a complete understanding of individual differences in fathers’ parenting quality requires considering multiple precursors to parenting in the same model. This study examined associations of three classes of predictors with fathers’ parenting quality: personal (i.e., personality, intuitive parenting behavior, and progressive beliefs), contextual (i.e., supportive coparenting, romantic relationship quality, job satisfaction), and child characteristics (i.e., temperament). These predictors of observed parenting quality (i.e., sensitivity, emotional engagement, positive regard) were examined among 182 fathers who transitioned to parenthood in 2008-2010. Results from structural equation modeling analyses indicated that fathers who showed higher-quality parenting behavior with their 9-month-old infants were those who demonstrated greater intuitive parenting behavior prior to their child’s birth, reported greater conscientiousness, reported greater openness to experience, and had more supportive coparenting relationships with their partners at 3 months postpartum. Implications for future research on fathers’ parenting and applications to prevention and intervention programs for expectant and new parents are discussed.

Keywords: father-child relationship, parenting, coparenting, intuitive parenting, temperament

Multiple factors have the potential to influence fathers’ parenting (Belsky, 1984; Cabrera, Fitzgerald, Bradley, & Roggman, 2014). Fathers report higher levels of involvement in childrearing when the coparenting relationship, or the extent to which parents operate as a team, is supportive (Carlson & McLanahan, 2006), their children have more sociable temperaments (McBride, Schoppe, & Rane, 2002), and mothers hold nontraditional beliefs about parent and gender roles (Zvara, Schoppe-Sullivan, & Dush, 2013). Although this research provides important insight into the underpinnings of fathers’ quantity of involvement, less is known about predictors of fathers’ parenting quality. This is a critical gap because father-child interactions characterized by positive parenting behaviors, such as sensitivity, warmth, and emotional engagement, are associated with children’s better social, emotional, and cognitive functioning (Sarkadi, Kristiansson, Oberklaid, & Bremberg, 2008). Thus, fathering experts have emphasized the importance of focusing on the quality of fathers’ involvement rather than the quantity of involvement alone (Adamsons & Johnson, 2013; Palkovitz, 2019; Schoppe-Sullivan & Fagan, 2020). Existing studies of predictors of fathers’ parenting quality, however, have rarely examined personal, contextual, and child characteristics in the same model, used observations of fathers’ parenting quality, and employed longitudinal designs.

Father-child relationships are formed across the transition to parenthood—a stressful period of time where new fathers often report feeling like bystanders, have access to limited resources, and experience challenges in navigating the transition with their romantic partners (Deave & Johnson, 2008). Moreover, parenting patterns established during the months following childbirth typically remain stable over time (Dallaire & Weinraub, 2005). Thus, to support fathers’ parenting quality, it is important to identify factors that are associated with high-quality parenting in the early months of parenthood. To better understand the underpinnings of fathers’ high-quality parenting behaviors at 9-months postpartum, the present study considered three classes of predictors: personal characteristics (i.e., personality, intuitive parenting, and progressive beliefs) measured prenatally, contextual factors (i.e., supportive coparenting, romantic relationship quality, job satisfaction) measured at 3-months postpartum, and child characteristics (i.e., temperament) measured at 3-months postpartum.

Fathers’ Parenting Quality: A Conceptual Framework

Although there is not a single universal theory, framework, or measure of fathers’ parenting (Cabrera et al., 2014; Palkovitz, 2019; Schoppe-Sullivan & Fagan, 2020), scholars concur regarding the importance of considering fathers’ ecological context. Belsky’s Multidimensional Model of the Determinants of Parenting (1984) provides a useful conceptual framework for considering the roles of personal, contextual, and child characteristics as precursors to fathers’ parenting quality. Cabrera and colleagues (2014) applied findings from recent research to expand Belsky’s (1984) model and more fully consider how various personal, contextual, and child factors predict fathers’ parenting quality longitudinally. However, surprisingly few studies have applied these theoretical frameworks to comprehensively examine predictors of multiple aspects (i.e., sensitivity, emotional engagement, and positive affect) of observed fathers’ parenting quality with their infants. Understanding individual differences in new fathers’ parenting quality can only be fully achieved when simultaneously considering the three theoretically informed classes of predictors—personal, contextual, and child characteristics—in the same model.

Personal Characteristics

Personality.

Fathers’ personality is considered a central determinant of parenting in both Belsky’s (1984) and Cabrera and colleagues’ (2014) model. Well-adjusted parents are typically higher in extraversion (i.e., intensity of interpersonal interaction, activity level, and capacity for joy), conscientiousness (i.e., well-organized, thorough, goal-oriented), and openness to experience (i.e., imaginative, enjoys new experiences, has broad interests) (Prinzie, Stams, Deković, Reijntjes, & Belsky, 2009). However, associations between personality and parenting have most commonly been examined among mothers. A few cross-sectional studies including fathers have reported that those higher in openness exhibit greater shared positive emotionality with their infants (Kochanska, Friesenborg, Lange, & Martel, 2004) and use less negative control with toddlers (Karreman, van Tuijl, van Aken, & Deković, 2008b). In their meta-analysis, Prinzie and colleagues (2009) emphasized the need for longitudinal studies examining associations between personality and parenting behavior. Thus, this study builds upon previous work by examining longitudinal associations between multiple aspects of fathers’ personality and observations of new fathers’ parenting quality.

Prenatal intuitive parenting.

Although largely understudied in the context of Belsky’s (1984) and Cabrera and colleagues’ (2014) models, intuitive parenting emerges during the third trimester of pregnancy and might be linked to postnatal parenting quality. Rooted in evolutionary theory, Papoušek and Papoušek (2002) suggested that parents engage in both conscious, controlled and non-conscious, automatic parenting behaviors. They coined the term intuitive parenting to capture the nonconscious behaviors, which include “a rich repertoire of adaptive activities lying between very fast and rigid innate reflexes and relatively slow, highly flexible, often culturally determined, rational behavior” (Papoušek & Papoušek, 2002, p. 189). Although newborns are biologically predisposed to cope with environmental stress, they rely heavily on caregivers to regulate their physical and emotional needs (see Koester & Lahti-Harper, 2010). Parents who exhibit greater intuitive parenting have additional cognitive resources to allocate toward environmental demands (i.e., protecting the child from danger). From this perspective, a parent can enjoy an interchange with their infant, responding meaningfully to their infant, and at the same time consider threats to the child’s safety.

Efforts to capture intuitive parenting prenatally began with the development of a novel 5-minute play procedure, the Prenatal Lausanne Trilogue Play (PLTP; Carneiro, Corboz-Warnery, & Fivaz-Depeursinge, 2006). In the PLTP, expectant parents are asked to imagine that they are meeting their baby for the first time and to play individually and together with a gender-neutral doll that represents the baby. The PLTP focuses on assessing the prenatal family alliance, or relationship between expectant parents, and predicts postnatal family interaction quality (Altenburger, Schoppe-Sullivan, Lang, Bower, & Kamp Dush, 2014; Favez, Frascarolo, Lavanchy Scaiola, & Corboz-Warnery, 2013). One of the scales in the PLTP coding system, the Intuitive Parenting Scale, focuses on six key parent behaviors toward the “baby”: holding in “en face” orientation, dialogue distance, baby talk and/or smiles, caresses and/or rocking, exploration of the baby’s body, and concern with the baby’s well-being (Carneiro et al., 2006; Papoušek & Papoušek, 2002).

The prenatal period provides a window into the development of parenting. During this time, parents psychologically prepare themselves and develop expectations for life with their child (Vreeswijk, Maas, Rijk, & van Bakel, 2014). Prior research has indicated associations between expectant fathers’ intuitive parenting behavior and fathers’ self-reports of engagement with their infants, but only when mothers’ intuitive parenting behavior was low (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2014). No prior study has examined expectant fathers’ intuitive parenting behavior as a predictor of fathers’ parenting quality, which is more centrally linked to positive child outcomes. Such an association would offer an opportunity for practitioners to identify expectant fathers with the greatest risk for exhibiting low-quality parenting behavior—before new fathers’ first child is born.

Progressive beliefs.

Both Belsky’s (1984) and Cabrera and colleagues’ (2014) models of parenting highlight the role of personal characteristics as predictors of parenting. Fathers who believe men and women should have equal power, responsibility, and involvement in children’s lives might exhibit higher-quality parenting. Prior research demonstrated associations between fathers’ progressive beliefs and competence interacting with their 3.5-month-old children (Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2008). However, less is known about the role of fathers’ progressive beliefs in predicting multiple aspects of fathers’ parenting quality (i.e., sensitivity, positive regard, and emotional engagement). This study expands upon prior work by examining longitudinal associations between fathers’ beliefs and behavior across the transition to parenthood.

Contextual Factors

Interparental relationship quality.

The larger context of father-child relationships also may support or impede fathers’ parenting (Belsky, 1984). One aspect of this context is the interparental relationship. The interparental relationship includes the quality of the romantic relationship between parents, which is considered a central determinant of parenting in Belsky’s (1984) process model and Cabrera and colleagues’ (2014) expanded model. Reduced romantic relationship quality has been associated with decreased fathers’ parenting quality and involvement in caregiveng (Grych, 2002). Related to, but distinct from, romantic relationship quality is the quality of the coparenting relationship (Schoppe-Sullivan, Mangelsdorf, Frosch, & McHale, 2004), defined as “the ways that parents and/or parental figures relate to each other in the role of parent” (Feinberg, 2003, p. 96). Coparenting relationship quality is hypothesized as an even more proximal predictor of parenting quality than romantic relationship quality (Feinberg, 2003), and especially important to high-quality parenting may be supportive coparenting behavior characterized by frequent warm, cooperative behavior between parents, and the relative absence of displeasure or hostility (Van Egeren & Hawkins, 2004). Scholars have identified positive associations between supportive coparenting and fathers’ sensitivity and responsiveness toward the child (Brown, Schoppe-Sullivan, Mangelsdorf, & Neff, 2010) and observed relative involvement and competence (Schoppe-Sullivan, Brown, Cannon, Mangelsdorf, & Sokolowski, 2008). The present study builds upon prior work on relations between interparental relationships and fathers’ parenting quality by examining associations within a structural equation modeling framework. Creating latent factors for supportive coparenting and fathers’ parenting quality accounts for measurement error (Palkovitz, 2019). Furthermore, our study considered longitudinal associations between observed supportive coparenting and fathers’ parenting quality, whereas both Brown and colleagues (2010) and Schoppe-Sullivan and colleagues (2008) examined cross-sectional associations.

Work.

Belsky (1984) and Cabrera and colleagues (2014) both considered fathers’ experiences in the context of work as potential predictors of parenting quality. Fathers who are not satisfied with their jobs might struggle to engage in high-quality parenting practices. Some theorists propose that fathers’ low job satisfaction might alter parenting behaviors by affecting fathers’ energy, time, and mood (Cabrera et al., 2014). Of the limited studies that have considered fathers’ work experiences as a predictor of their parenting quality, Cooklin et al. (2016) reported that Australian fathers with higher work-family conflict exhibited irritable, less warm, and more inconsistent parenting with 4- to 5-year-old children.

Child Temperament

Child temperament, defined as physiologically-based individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation (Rothbart, Ahadi, & Evans, 2000), includes a set of child characteristics likely to affect parenting (Belsky, 1984). Negative emotionality, characterized by fear, anger/frustration, discomfort, and sadness, is a core dimension of temperament (Belsky, Hsieh, & Crnic, 1998) and part of the difficult temperament construct. The few studies that have included fathers indicate fathers’ responsiveness, involvement, and affection suffer (Goldberg, Clarke-Stewart, Rice, & Dellis, 2002), and fathers’ negativity increases (Padilla & Ryan, 2019), in the presence of an infant with a difficult temperament. An additional component of temperament, orienting and regulatory capacity, is characterized by infants’ ability to sustain attention for long periods of time and enjoy low-stimulation activities (i.e., being read to) (Eisenberg, Hofer, & Vaughan, 2007). Although largely understudied, individual differences in infants’ orienting and regulatory capacity are likely to be associated with fathers’ parenting quality. For instance, fathers of infants with orienting and regulatory capacity difficulties might have decreased patience and greater difficulty responding sensitively in a parent-child interaction. However, infants with greater orienting and regulatory capacity might increase the opportunity for parents to engage sensitively and express positive emotions. Consistent with this perspective, prior research has reported an association between lower orienting and regulatory capacity during infancy and more negative maternal parenting at 18 months (Bridgett et al., 2009). Building upon prior work, this study examined associations between infant temperament and fathers’ parenting quality longitudinally, considered infant orienting and regulatory capacity in addition to negative emotionality, and focused on fathers’ perceptions of infant temperament, which are likely more closely linked to fathers’ parenting quality than mothers’ perceptions of temperament.

The Present Study

The present study applied Belsky (1984) Multiple Determinants of Parenting Model and Cabrera and colleagues’ (2014) expanded model of father-child relationships to examine personal characteristics (i.e., personality, intuitive parenting, and progressive beliefs), contextual characteristics (i.e., supportive coparenting, romantic relationship quality, and job satisfaction), and children’s characteristics (i.e., temperament) as predictors of new fathers’ parenting quality. By including these three categories of theoretically-informed predictors in the same model, the present study was designed to take a comprehensive approach in examining predictors of fathers’ parenting quality. Fathers’ age and education level were included as control variables as theoretical models have suggested these factors might play a role in fathers’ parenting quality (Cabrera et al., 2014). Indeed, prior research has indicated associations between parents’ greater educational attainment and higher-quality parenting behaviors (Davis-Kean, 2005). The present study also controlled for infant sex. Feldman (2003) argued that same-sex infant-parent dyads might develop more synchronous interactions than different-sex infant-parent dyads.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were drawn from a longitudinal study of 182 dual-earner couples transitioning to parenthood. Recruitment occurred at childbirth education classes, pregnancy health centers, and through the use of advertisements posted online, at doctors’ offices, and in newspapers. Eligible participants were required to be married or cohabiting, at least 18 years of age, expecting their first biological child, able to read and speak English, currently employed full-time and planning to return to work post-birth at least part time. To comply with procedures dictated by the Behavioral and Social Sciences Institutional Review Board, informed consent was obtained from each partner at each phase of the study.

Of the 182 participating fathers, the median education level was a bachelor’s degree. Sixty-five percent of fathers reported having at least this level of education. The median household income during the third trimester of pregnancy was $78,218. On average, fathers were 30.20 years of age (SD = 4.81) and mothers were 28.24 years of age (SD = 4.02). Of fathers who reported a race, 86% identified as White, 7% as Black, 3% as Asian, 4% as other races, and 1 % as multi-racial. Of mothers who reported a race, 85% identified as White, 6% as Black, 3% as Asian, 2% as other races, and 4% as multi-racial. Additionally, 2% of fathers and 4% of mothers identified as Hispanic. Eighty-six percent of fathers who reported a relationship status were married. Among fathers who reported their baby’s sex at 3-months postpartum, 52.8% of children were male.

Data collection occurred in four waves from October 2008 through October 2010 during the third trimester of pregnancy and 3, 6, and 9 months postpartum. The current study focused on data that were collected during the third trimester of pregnancy, 3-months, and 9-months postpartum, as observations of fathers’ intuitive parenting, supportive coparenting, and fathers’ parenting quality were collected at these time points. Fathers also completed questionnaires, reporting on various demographic, personal, contextual, and child characteristics.

Measures

Prenatal

Personality.

Fathers’ personality was assessed using the NEO – Five Factor Inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1992), a valid and reliable measure of personality. This measure required fathers to report the extent to which they agreed with 36 various statements on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), which were designed to assess fathers’ openness to experience (12 items), conscientiousness (12 items), and extraversion (12 items). Cronbach’s alphas for each dimension of personality included in this study ranged from .74 to .82.

Intuitive parenting.

Expectant fathers’ intuitive parenting behavior was assessed during the third trimester of pregnancy using the Prenatal Lausanne Trilogue Play procedure (Carneiro et al., 2006). During this procedure, both expectant parents were presented with a gender-neutral doll and asked to imagine the first moment they will meet their child and to play individually and together with the “baby”. Two trained research assistants independently coded the frequency and intensity of six different types of intuitive parenting behaviors directed toward the “baby.” These behaviors included holding or facing the baby, dialogue distance, “baby talk” and /or smiling at the baby, caressing and rocking, exploring the baby’s body, and preoccupation with the baby’s well-being. In the original coding system, fathers received 1 point for the presence or absence of each of the six different intuitive parenting behaviors, with total scores for intuitive parenting behavior ranging from 0 to 6 (Carneiro et al., 2006). However, to account for both the quantity and intensity of intuitive parenting behaviors, the present study used a modified version of the Intuitive Parenting Scale (see Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2014) to assign scores. This ordinal scale ranged from 1 (i.e., parent displays no intuitive parenting behavior and may seem to have little knowledge of how to approach the baby or appear entirely disinterested in the task) or 2 (i.e., parent displays 1 to 2 intuitive parenting behaviors, but they are not consistently present throughout the entire episode, and the parent does not appear to be confident/comfortable in his/her actions) to 5 (i.e., parent displays 5 to 6 intuitive parenting behaviors and these are consistently maintained/repeated throughout the episode and the parent is comfortable/natural using them). Interrater reliability between trained coders (γ =.76) was acceptable as indicated by a Gamma statistic. Coders overlapped on 33% of the total number of cases.

Progressive beliefs.

Fathers’ progressive beliefs were assessed using the Beliefs Concerning the Parental Role Scale (Bonney & Kelley, 1996), from which fathers rated their agreement (1 = disagree strongly, 5 = agree strongly) with 26-items concerning the role of the mother (i.e., “when a child becomes ill at daycare/school it is primarily the mother’s responsibility to leave work or make arrangements for the child”) and father (i.e., “it is equally as important for a father to provide financial, physical, and emotional care to his children”). Items were reverse-scored as necessary. Individual items were averaged to create a progressive beliefs variable. Higher scores indicated more progressive beliefs about parental roles (α = .85).

Three Months Postpartum

Supportive coparenting behavior.

Observations of supportive coparenting behavior were obtained at 3-months postpartum from 5-minute mother-father-infant free play interactions. In these episodes, parents were given an infant-toddler play gym and instructed to play together with their child as they normally would if they had a few extra minutes in their day. The task was designed to elicit various types of coparenting behaviors, including displays of supportive and cooperative behavior between parents. Two trained research assistants assessed the videos for various aspects of supportive coparenting behavior using ordinal scales originally developed by Cowan and Cowan (1996) and used to examine coparenting behavior in prior research (Altenburger et al., 2014). Supportive coparenting scales ranged from 1 (low frequency and intensity behaviors) to 5 (high frequency and intensity behaviors). The scales used as indicators of supportive coparenting were cooperation (i.e., parents support one another and build off of each other in their parenting approach), pleasure (i.e., parent exhibits signs of joy in their coparenting partner’s interaction with the child), and warmth (i.e., parent directs affectionate behaviors toward their coparenting partner in relation to their partner’s interaction with the child). Pleasure and warmth were scored separately for mothers and fathers. Reliability for supportive coparenting subscales was acceptable, with gamma statistics ranging from 0.72 to 0.87. Coders overlapped on 50.6% of cases.

Romantic relationship quality.

At 3-months postpartum, fathers reported their adjustment in their romantic relationship using the brief Dyadic Adjustment Scale (brief DAS; Sabourin, Valois, & Lussier, 2005). Fathers rated on a scale of 1 (never) to 6 (all of the time) how frequently three situations occurred in their relationship (i.e., “How often do you discuss or have you considered divorce, separation, or terminating your relationship?”). Fathers were additionally asked to rate their overall happiness in the relationship from 0 (extremely unhappy) to 6 (perfect). Reliability for this measure was acceptable (α = .74).

Job satisfaction.

Fathers responded to a single question—“All in all, how satisfied would you say you are with your job?”—on a scale from 1 (very satisfied) to 4 (not at all satisfied). This measure was reverse scored, so higher scores indicated greater job satisfaction.

Infant temperament.

Father-reported infant negative emotionality and orienting and regulatory capacity were obtained using the Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire—Very Short Form (Rothbart & Gartstein, 2000) at three months postpartum. Each item required fathers to rate the extent to which their infant exhibited a particular behavior during the past week on an ordinal scale of 0 to 7, where 0 means the behavior does not apply, 1 means that the parent has never observed their infant exhibiting the described behavior, and 7 means the behavior has been very frequently observed. Twelve negative emotionality items (i.e., “When tired, how often did your baby show distress?”) were averaged to indicate a total negative emotionality score (α = .82). Twelve orienting and regulatory capacity items (i.e., “How often during the last week did the baby play with one toy or object for 5-10 minutes?”) were averaged to yield a total orienting and regulatory capacity score (α = .72).

Nine Months Postpartum

Fathers’ parenting quality.

Fathers’ parenting quality was assessed in a 5-minute dyadic play when children were 9 months old, using the Parent-Child Coding Manual (adapted from Cox & Crnic, 2002). Fathers were asked to try to teach their baby to play with either a shape sorter or stacking rings; the toy for the interaction was selected randomly. Trained coders independently coded three parenting dimensions: sensitivity (i.e., parent observes and responds appropriately to the child’s social gestures, expressions, and signals), detachment (i.e., parent is uninvolved and lacks engagement), and positive regard (i.e., parent expresses positive feelings toward the child, such as speaking in a warm tone, laughing with the child, or smiling). All dimensions were assessed on a 5-point rating scale ranging from 1 (very low) to 5 (very high). Gamma statistics indicated that reliabilities for each parenting quality subscale, including sensitivity (γ = .77), detachment (γ = .70), and positive regard (γ = .83) were acceptable. Coders overlapped on 100% of the cases.

Results

Analysis Plan

First, descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among variables of interest were calculated. Structural equation modeling analyses (SEM) with maximum likelihood estimation were conducted in Mplus, version 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Fathers’ personal (i.e., personality, intuitive parenting behavior, and progressive beliefs), contextual (i.e., supportive coparenting, romantic relationship quality, job satisfaction), and child characteristics (i.e., temperament) were estimated as predictors of observed fathers’ parenting quality at nine months postpartum. Fathers’ age, education, and child sex were included as control variables.

To determine the extent to which the hypothesized model was an adequate fit for the data, a number of fit indices were considered, including a non-significant chi-square test, RMSEA of .06 or lower, and a CFI and TLI of .95 or higher (McDonald & Ho, 2002). The fit of the measurement models for supportive coparenting at 3-months postpartum and fathers’ parenting quality at 9-months postpartum were evaluated before the general structural model was tested. Prior to data analysis, data were assessed for missingness at the third trimester of pregnancy and at 3- and 9- months postpartum. In examining the usable missing values of interest, there was a modest amount of missingness at the prenatal time point (1.6% - 5.5%), a modest amount of missingness at 3- months postpartum (5.5%-12.6%), and a moderate percentage of missingness at 9-months postpartum (15.9%). The pattern of missing responses was arbitrary. Fathers who participated at 3-months and 9-months postpartum did not statistically significantly differ from fathers who did not participate on variables of interest. The results of Little’s MCAR test were nonsignificant: χ2(1795) =1835.06, p > .10. To handle missing data, the model was estimated using full-information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML). Outcomes are modeled conditional on predictors and the only way to avoid listwise deletion for cases with missingness on these variables is to include them in the model (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Thus, variances for predictors were estimated to address missing data via FIML.

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations.

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for all variables of interest are shown in Table 1. Intercorrelations revealed associations of fathers’ personal characteristics, contextual factors, and child characteristics with fathers’ parenting quality at 9-months postpartum. Namely, greater sensitivity was observed when fathers held progressive beliefs, scored higher on openness, exhibited greater prenatal intuitive parenting, had supportive coparenting relationships, and reported greater romantic relationship quality. Fathers showed greater detachment when they experienced less supportive coparenting, perceived lower romantic relationship quality, and exhibited lower prenatal intuitive parenting. Finally, fathers exhibited greater positive affect with their infants when coparenting was more supportive, infants were higher in orienting and regulatory capacity, and fathers’ exhibited greater prenatal intuitive parenting.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations and descriptive statistics among variables of interest

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. | 17. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Intuitive parenting behavior | - | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Progressive beliefs | .13 | - | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Openness | −.02 | .28*** | - | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Conscientiousness | .02 | .02 | −.20** | - | |||||||||||||

| 5. Extraversion | .04 | .03 | −.01 | .06 | - | ||||||||||||

| 6. Relationship quality | .06 | .10 | −.09 | .19* | .13 | - | |||||||||||

| 7. Cooperation | .05 | .01 | .09 | −.08 | −.01 | .11 | - | ||||||||||

| 8. Warmth_m | .10 | .02 | .12 | −.09 | .10 | .13 | .60*** | - | |||||||||

| 9. Warmth_f | .14 | .06 | .10 | −.06 | .12 | .16* | .63*** | .78*** | - | ||||||||

| 10. Pleasure_m | .04 | .07 | .14 | −.14 | −.01 | .13 | .61*** | .69*** | .64*** | - | |||||||

| 11. Pleasure_f | .10 | .12 | .17* | −.17* | .01 | .11 | .63*** | .66*** | .70*** | .75*** | - | ||||||

| 12. Job satisfaction | .04 | .06 | −.05 | .10 | .17* | .004 | −.05 | .09 | .01 | −.03 | −.003 | - | |||||

| 13. ORC | −.05 | .09 | .10 | .15 | .13 | .10 | −.04 | −.01 | .01 | −.06 | −.01 | .08 | - | ||||

| 14. NEG | −.02 | −.05 | .16* | −.02 | −.14 | −.26*** | .05 | .04 | .06 | .09 | .04 | −.06 | −.21** | - | |||

| 15. Sensitivity | .31*** | .21* | .22** | .09 | .10 | .17* | .27** | .30*** | .33*** | .28*** | .30*** | .02 | .13 | −.02 | - | ||

| 16. Detachment | −.32*** | −.15 | −.06 | −.14 | −.03 | −.16* | −.16* | −.15 | −.24** | −.14 | −.17* | −.02 | −.08 | .07 | −.71*** | - | |

| 17. Positive affect | .23** | .10 | .13 | .09 | .10 | .11 | .17* | .15 | .28*** | .18* | .22** | −.003 | .16* | .02 | .73*** | −.62*** | - |

| Mean | 3.22 | 4.25 | 3.31 | 3.81 | 3.47 | 5.20 | 3.36 | 3.00 | 2.81 | 3.05 | 2.79 | 3.16 | 5.21 | 3.47 | 3.12 | 2.68 | 2.78 |

| SD | .96 | .42 | .55 | .50 | .50 | .57 | .96 | .79 | .82 | .89 | .89 | .75 | .66 | .94 | .55 | .62 | .77 |

p < .05

p <.01

p < .001 ; m= mother, f= father, ORC = orienting and regulatory capacity, NEG = negative emotionality

Construction of latent variables.

Patterns of intercorrelations (Table 1) supported the construction of a latent variable representing supportive coparenting at 3-months postpartum, as well as a latent variable representing fathers’ parenting quality at 9-months postpartum. At 3-months postpartum, cooperation, as well as individual measures of mothers’ and fathers’ coparenting warmth and pleasure, were included as indicators of a latent supportive coparenting behavior factor. Additionally, at 9-months postpartum, fathers’ sensitivity, detachment, and positive regard were included as indicators of a latent fathers’ parenting quality factor. The cooperation and fathers’ sensitivity parameters were both set to 1.0, in their respective latent factors. This scaling ensures the scale of the latent factor is the same as the scale of the observed indicator, but it does not change the interpretation of standardized factor loadings (Kelloway, 2015). Both sets of latent variables were tested simultaneously. The initial measurement model, however, did not have acceptable fit. The chi-square test was significant χ2(19) = 41.239, p = .002. Other indices of model fit revealed moderately acceptable fit: TLI = .96; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .081.

Modification indices were evaluated to examine where model fit could be improved. Modification indices recommended correlating the errors between fathers’ warmth and mothers’ warmth and correlating the errors between fathers’ pleasure and mothers’ pleasure. The addition of these correlated errors was justified because the unique variance between parents’ warmth and pleasure (unaccounted for by coparenting relationship quality) could be because one parent’s expression of pleasure or warmth might elicit warmth or pleasure from the other parent. With this addition, model fit was acceptable χ2(17) = 22.41, p = .17, and TLI = .99; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .042, 90% CI [.000, .085]. All factor loadings were statistically significant and standardized loadings ranged in absolute value from .75 to .93. Squared multiple correlations (SMC) for indicators of latent variables ranged from .56 to .86, with all but two SMCs above .60.

Structural Model Test

Next, the structural model including fathers’ personal characteristics (i.e., personality, intuitive parenting, and progressive beliefs), contextual factors (i.e., supportive coparenting, romantic relationship quality, and job satisfaction), and child characteristics (i.e., temperament) were assessed as predictors of fathers’ parenting quality at 9-months postpartum. The structural model also included child sex, fathers’ education level, and fathers’ age as control variables. The chi-square test was non-significant: χ2(89) = 79.08, p = .77. Other indices of model fit were acceptable: TLI = 1.02; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .000, 90% CI [.000, .029].

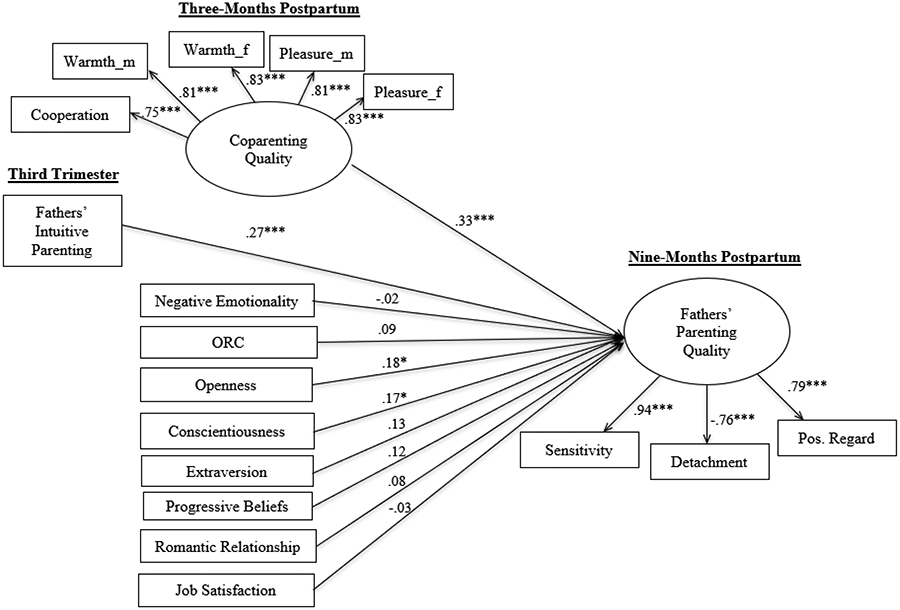

Standardized results for the final structural model are depicted in Figure 1. Greater fathers’ intuitive parenting behavior (β = 0.27, p < 0.001), greater openness (β = 0.18, p < 0.05), and greater conscientiousness (β = 0.17, p < 0.05) measured prenatally predicted fathers’ higher-quality parenting at 9-months postpartum. Additionally, greater supportive coparenting behavior at 3-months postpartum predicted fathers’ higher-quality parenting at 9-months postpartum (β = 0.33, p < 0.001). Fathers’ extraversion, progressive beliefs, and child temperament did not emerge as statistically significant predictors. Control variables (i.e., fathers’ education level, fathers’ age, and child sex) were also not significantly associated with fathers’ parenting quality. The model explained 37% of the variance in fathers’ parenting quality.

Figure 1. Predictors of fathers’ parenting quality.

Note. Correlated errors not depicted; χ2(89) = 79.08. p = 0.77; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.02; RMSEA = .000; SRMR = .027. *p < .05; ***p < .001.

Fathers’ age, education level, and child gender not depicted.

ORC = Orienting and regulatory capacity

Discussion

The goal of this study was to apply Belsky’s (1984) and Cabrera and colleagues (2014) models to consider personal, contextual, and child characteristics as predictors of new fathers’ observed parenting quality. Given that fathers are more involved in parenting than ever before, and that the quality of fathers’ parenting is more critical to children’s development than the sheer quantity of their involvement, it is important to identify factors associated with new fathers’ parenting quality as early as possible. Associations between theoretically-informed predictors and fathers’ parenting quality were examined in a sample of new fathers because the transition to parenthood is a stressful period of time in which new patterns of parenting are established. Better understanding the underpinnings of fathers’ parenting quality during this time has the potential to inform new fathers’ optimal parenting practices, which will ultimately support a secure infant-father attachment bond (Brown et al., 2010) and positive father-child relationships across the life span. Furthermore, we considered associations between predictors of parenting and multiple aspects of fathers’ parenting behavior (i.e., sensitivity, emotional engagement, and positive regard) within the same model to comprehensively examine predictors of fathers’ parenting quality. Study results provided evidence for direct effects of fathers’ personal and contextual characteristics as predictors of fathers’ parenting quality.

Personal Characteristics

The aspects of personality examined in this study were fathers’ extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. When fathers reported higher levels of conscientiousness and openness to experience prenatally, they exhibited higher quality parenting at 9-months postpartum. Fathers’ conscientiousness, or the extent to which they are well-organized, thorough, and goal-oriented, might be a beneficial to their adjustment to a new parenting role. Fathers who score high on this aspect of personality might also attempt to be thorough and have high standards for their parenting, be more organized and practical, and thus feel less overwhelmed by parenting tasks (De Haan, Prinzie, & Deković, 2009). Fathers’ openness to experience captures the extent to which a person enjoys new experiences, is inventive, and imaginative. Because the transition to parenthood is a new experience, fathers high on this dimension might be especially likely to adjust well in their new roles and exhibit positive parenting behaviors. When interacting with their child, open fathers might be more creative and imaginative in their approaches (De Haan et al., 2009). Although both conscientiousness and openness appear to be assets for new fathers, it is noteworthy that they were negatively correlated in this sample. That is, fathers higher on conscientiousness tended to be lower in openness to experience.

Fathers’ extraversion did not predict their parenting quality at 9-months postpartum. This is somewhat surprising, as fathers high on extraversion are likely to show higher levels of positive affect and sociability. However, perhaps the nature of the task (i.e., teaching) and the young age of the child could explain the non-significant association. Extraverted fathers might have more of an opportunity to engage in high-quality parenting practices in a play task with older children. Future research should consider the possibility that the nature of the parenting situation and age of the child might affect the associations of extraversion (and other aspects of parent personality) with parenting quality.

Fathers’ prenatal intuitive parenting was also considered as a predictor of postnatal parenting quality in this study. Although not explicitly stated in Belsky’s (1984) and Cabrera and colleagues’ (2014) models, fathers’ intuitive parenting is a personal characteristic that can be captured during the prenatal period. Results indicated that greater intuitive parenting behavior during the third trimester of pregnancy predicted higher-quality parenting in fathers at nine months postpartum even when accounting for multiple additional theoretically informed predictors and covariates. This finding suggests that expectant fathers’ intuitive parenting behavior, as assessed in the Prenatal Lausanne Trilogue Play (Carneiro et al., 2006), might be an early indicator of fathers’ high-quality parenting behavior postpartum, and demonstrates the validity and utility of the PLTP as a window into the development of fathers’ parenting quality. Future research should continue to explore factors that underlie fathers’ intuitive parenting behavior and the extent to which prenatal representations and attachment to the fetus (Habib & Lancaster, 2010; Theran, Levendosky, Bogat, & Huth-Bocks, 2005) might be linked to individual differences in intuitive parenting. The present study points to the utility of the PLTP as a tool for identifying fathers who exhibit low-quality intuitive parenting behavior and, thus, might be at greater risk of developing low-quality parenting behavior. Perhaps interventions similar to those that have been implemented to improve the coparenting relationship across the transition to parenthood (see Cowan, Cowan, Kline Pruett, & Pruett, 2007; Feinberg, 2003) could also be used to educate and prepare expectant fathers to engage in high-quality parenting behaviors during the early months following childbirth.

Fathers’ progressive beliefs did not predict their parenting quality. It should be noted that the present sample included only families where both parents were working full time outside of the home. Perhaps associations might have been detected had families that conform to more “traditional” work-family roles (i.e., mother stays at home and father is primary breadwinner) been included. Future research should consider this possibility.

Contextual Characteristics

Results also indicated that higher levels of observed supportive coparenting at 3-months postpartum predicted fathers’ higher-quality parenting behaviors at 9-months postpartum. Findings continue to support the notion that high-quality coparenting relationships, characterized by cooperation, warmth, and pleasure between parents, positively support fathers’ parenting quality (Brown et al., 2010; Carlson & McLanahan, 2006). However, the current study’s finding bolsters the existing evidence by finding longitudinal support for this association, and utilizing multiple indicators of observed coparenting support and observed fathers’ parenting quality. It is worth noting that this study focused exclusively on supportive coparenting as a predictor of fathers’ parenting quality. Future research should expand this focus to also consider the consequences of undermining coparenting for fathers’ parenting quality.

Efforts to ensure the coparenting relationship is characterized by high-quality interactions (i.e., cooperation, warmth, and pleasure) should be an important component of prenatal education classes and other efforts to bolster family relationship quality (Cowan et al., 2007; Feinberg, 2003). Perhaps clinicians can utilize observations of mother-father-child interactions to provide video feedback to parents about which types of coparenting behaviors are most important in supporting father-child relationships, as fathers appear to be particularly susceptible to coparenting relationship quality (Brown et al., 2010). Strengthening the coparenting relationship by encouraging supportive, cooperative, and positive behaviors might provide an optimal foundation for strong father-child relationships, and, in turn, positive child social and emotional adjustment. Furthermore, researchers have extended research on intuitive parenting behaviors to intuitive coparenting behaviors (Darwiche, Fivaz-Depeursinge, & Corboz-Warnery, 2016). However, the consequences of prenatal intuitive coparenting behavior for fathers’ parenting quality postpartum are unknown.

Fathers’ satisfaction with work and perceptions of romantic relationship quality did not predict their parenting quality with their 9-month-old children. Thus, supportive coparenting emerged as the contextual factor that most strongly predicted fathers’ parenting quality. It is possible that supportive coparenting might be more proximally related to parenting than romantic relationship quality (Feinberg, 2003). Future research should continue to consider the role of work in fathers’ parenting quality. It is a limitation that our study only included a single item assessing job satisfaction. The inclusion of a more nuanced measure of work-family dynamics would be beneficial. It is also possible that fathers’ job satisfaction might play a more significant role as children get older and fathers to try to maintain optimal work-life balance.

Child Characteristics

In examining child characteristics as predictors of fathers’ parenting quality, neither infant orienting and regulatory capacity nor infant negative emotionality emerged as statistically significant predictors. Prior empirical research examining the link between infant negative emotionality and fathers’ quality and quantity of involvement has shown mixed results. For example, prior research has suggested that fathers report higher levels of engagement in childcare with 3-month-old infants high in negative emotionality (Goldberg et al., 2002), while other studies have reported that fathers exhibit more negativity in response to infant negative emotionality (Padilla & Ryan, 2019). Furthermore, the sample included in this study was low-risk and nonclinical. Thus, infants had relatively low levels of negative emotionality, and fathers had resources to cope with challenging infants. It is possible that in a higher-risk sample, a significant association between infant negative emotionality and fathers’ parenting quality would be detected (Crockenberg & Leerkes, 2000).

Research examining the role of infant orienting and regulatory capacity (ORC) in parenting quality has primarily focused on mothers and indicated that infants with regulatory difficulties were at the greatest risk for experiencing maternal negative parenting (Bridgett et al., 2009). In early childhood, however, researchers have reported associations between fathers’ parenting quality—both observed and reported—and child effortful control, such that reduced effortful control in preschoolers was associated with fathers’ negatively controlling behavior (i.e., intrusiveness, punishment) (Karreman, Van Tuijl, Van Aken, & Deković, 2008a). It is notable that both of these studies focused on negative aspects of parenting, while the present study considered positive aspects of parenting. Perhaps associations between infant ORC and parenting quality might be detected if measures of negative parenting behaviors were examined (i.e., intrusiveness, negative affect). It is also possible that the associations between fathers’ parenting quality and infant ORC are not fully apparent until the child is of preschool age. Future research should continue to examine associations between multiple aspects of infant temperament and fathers’ parenting quality in diverse samples across the first few years of life.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study’s sample consisted of dual-earner, different-sex couples, who were largely middle-class and White. Thus, the findings might not apply to other populations of new fathers, including nonresident fathers or those in same-sex relationships. Furthermore, although observations of fathers’ parenting quality provide rich insight into the types of behaviors fathers exhibit when interacting with their children, the father-child observations were relatively brief (five minutes). It is possible that more robust associations between predictors and fathers’ parenting quality would be uncovered if observations had lasted longer or had occurred in different contexts (e.g., play versus child care). Future research should utilize more in-depth and longer observations to consider predictors of fathers’ parenting quality among more diverse families. Additionally, new research should examine bidirectional relations between coparenting, infant temperament, and fathers’ parenting quality, as fathers’ involvement in play activities predicts more supportive coparenting a year later (Jia & Schoppe-Sullivan, 2011) and the associations of personal, contextual, and child characteristics with fathers’ parenting quality may be reciprocal (Cabrera et al., 2014).

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study has yielded important insight into factors linked to three aspects of fathers’ parenting quality (i.e., sensitivity, emotional engagement, and positive regard) and took a comprehensive (although not exhaustive) approach to considering multiple predictors. The transition to parenthood is a critical point in time for the establishment of the family system, as the romantic relationship expands to include other family subsystems: coparenting, mother-child, and father-child relationships. Fathers who successfully navigate the transition to parenthood are better positioned to maintain sustained patterns of high-quality parental involvement postpartum (Dallaire & Weinraub, 2005). Thus, for practitioners working with expectant and new fathers, understanding factors that predict fathers’ parenting quality is critical. Perhaps practitioner support targeted at strengthening intuitive parenting behavior and coparenting relationship quality would serve to bolster fathers’ emerging parenting skills and better prepare fathers-to-be and new fathers for their parenting roles.

Acknowledgments

This article and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Science Foundation (NSF), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), Pennsylvania State University–Shenango, or The Ohio State University. Preliminary results from this study were presented at the Society for Research in Child Development Biennial Meeting in Austin, Texas, in April 2017. Preliminary findings were also presented as part of the first author’s dissertation research at The Ohio State University in March 2018. The New Parents Project was funded by the National Science Foundation (CAREER 0746548, Sarah J. Schoppe-Sullivan), with additional support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; 1K01HD056238, Kamp Dush), and The Ohio State University’s Institute for Population Research (NICHD R24HD058484) and program in Human Development and Family Science. We also acknowledge Claire M. Kamp Dush’s invaluable contributions to the design and execution of the New Parents Project. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Adamsons K, & Johnson SK (2013). An updated and expanded meta-analysis of nonresident fathering and child well-being. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(4), 589–599. doi: 10.1037/a0033786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altenburger LE, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Lang SN, Bower DJ, & Kamp Dush CM (2014). Associations between prenatal coparenting behavior and observed coparenting behavior at 9-months postpartum. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(4), 495–504. doi: 10.1037/fam0000012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55(1), 83–96. doi: 10.2307/1129836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Hsieh K-H, & Crnic K (1998). Mothering, fathering, and infant negativity as antecedents of boys' externalizing problems and inhibition at age 3 years: Differential susceptibility to rearing experience? Development and Psychopathology, 10(2), 301–319. doi: 10.1017/S095457949800162X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonney JF, & Kelley M (1996). Development of a measure assessing maternal and paternal beliefs regarding the parental role: The Beliefs Concerning the Parental Role Scale. Unpublished manuscript, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgett DJ, Gartstein MA, Putnam SP, McKay T, Iddins E, Robertson C, … Rittmueller, A. (2009). Maternal and contextual influences and the effect of temperament development during infancy on parenting in toddlerhood. Infant Behavior and Development, 32(1), 103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GL, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Mangelsdorf SC, & Neff C (2010). Observed and reported supportive coparenting as predictors of infant–mother and infant–father attachment security. Early Child Development and Care, 180(1-2), 121–137. doi: 10.1080/03004430903415015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Fitzgerald HE, Bradley RH, & Roggman L (2014). The ecology of father-child relationships: An expanded model. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 6(4), 336–354. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MJ, & McLanahan SS (2006). Strengthening unmarried families: Could enhancing couple relationships also improve parenting? Social Service Review, 80(2), 297–321. doi: 10.1086/503123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro C, Corboz-Warnery A, & Fivaz-Depeursinge E (2006). The prenatal Lausanne Trilogue Play: A new observational assessment tool of the prenatal co-parenting alliance. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27(2), 207–228. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooklin AR, Westrupp EM, Strazdins L, Giallo R, Martin A, & Nicholson JM (2016). Fathers at work: work–family conflict, work–family enrichment and parenting in an Australian cohort. Journal of Family Issues, 37(11), 1611–1635. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14553054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, & McCrae RR (1992). NEO PI-R Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, & Cowan PA (1996). Schoolchildren and their familes project: Description of co-parenting style ratings. Unpublished coding scales. University of California Berkeley, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA, Kline Pruett M, & Pruett K (2007). An approach to preventing coparenting conflict and divorce in low-income families: Strengthening couple relationships and fostering fathers' involvement. Family Process, 46(1), 109–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00195.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, & Crnic K (2002). Qualitative ratings for parent-child interactions at 3-12 months of age. Unpublished manuscript University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S, & Leerkes E (2000). Infant social and emotional development in family context. In Zeanah CH (Ed.), Handbook of infant mental health (pp. 60–90). New York, NY: Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- Dallaire DH, & Weinraub M (2005). The stability of parenting behaviors over the first 6 years of life. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 20(2), 201–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2005.04.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darwiche J, Fivaz-Depeursinge E, & Corboz-Warnery A (2016). Prenatal intuitive coparenting behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1662. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Kean PE (2005). The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: the indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 294–304. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deave T, & Johnson D (2008). The transition to parenthood: what does it mean for fathers? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 63, 626–633. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Haan AD, Prinzie P, & Deković M (2009). Mothers’ and fathers’ personality and parenting: The mediating role of sense of competence. Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1695–1707. doi: 10.1037/a0016121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Hofer C, & Vaughan J (2007). Effortful control and its socioemotional consequences. In Gross JJ (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 287–306). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Favez N, Frascarolo F, Lavanchy Scaiola C, & Corboz-Warnery A (2013). Prenatal representations of family in parents and coparental interactions as predictors of triadic interactions during infancy. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34(1), 25–36. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3(2), 95–131. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R (2003). Infant–mother and infant–father synchrony: The coregulation of positive arousal. Infant Mental Health Journal, 24(1), 1–23. doi: 10.1002/imhj.10041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg WA, Clarke-Stewart KA, Rice JA, & Dellis E (2002). Emotional energy as an explanatory construct for fathers' engagement with their infants. Parenting: Science and Practice, 2(4), 379–408. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0204_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH (2002). Marital relationships and parenting In Bornstein MH (Ed.), Handbook of Parenting: Social Conditions and Applied Parenting (Vol. 4, pp. 238–225). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Habib C, & Lancaster S (2010). Changes in identity and paternal–foetal attachment across a first pregnancy. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 28(2), 128–142. doi: 10.1080/02646830903298723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia R, & Schoppe-Sullivan SJ (2011). Relations between coparenting and father involvement in families with preschool-age children. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 106–118. doi: 10.1037/a0020802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karreman A, van Tuijl C, van Aken MA, & Deković M (2008a). Parenting, coparenting, and effortful control in preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(1), 30–40. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karreman A, van Tuijl C, van Aken MA, & Deković M (2008b). The relation between parental personality and observed parenting: The moderating role of preschoolers’ effortful control. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(3), 723–734. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.10.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway KE (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis. In Kelloway KE (Ed.), Using Mplus for structural equation modeling (pp. 52–90). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Friesenborg AE, Lange LA, & Martel MM (2004). Parents' personality and infants' temperament as contributors to their emerging relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(5), 744–759. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester LS, & Lahti-Harper E (2010). Mother-infant hearing status and intuitive parenting behaviors during the first 18 months. American Annals of the Deaf 155(1), 5–18. doi: 10.1353/aad.0.0134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride BA, Schoppe SJ, & Rane TR (2002). Child characteristics, parenting stress, and parental involvement: Fathers versus mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(4), 998–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00998.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, & Ho M-HR (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64–82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2017). Mplus user's guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla CM, & Ryan RM (2019). The link between child temperament and low-income mothers’ and fathers’ parenting. Infant Mental Health Journal, 40(2), 217–233. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovitz R (2019). Expanding Our Focus From Father Involvement to Father–Child Relationship Quality. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 11(4), 576–591. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papoušek H, & Papoušek M (2002). Intuitive parenting. In Bornstein MH (Ed.), Handbook of Parenting Volume 2 Biology and Ecology of Parenting (pp. 182–203). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Prinzie P, Stams GJJ, Deković M, Reijntjes AH, & Belsky J (2009). The relations between parents’ Big Five personality factors and parenting: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(2), 351–362. doi: 10.1037/a0015823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, & Evans DE (2000). Temperament and personality: origins and outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(1), 122–135. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, & Gartstein MA (2000). The Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire -- Very Short Form. Unpublished questionnaire. University of Oregon. Eugene, OR. [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin S, Valois P, & Lussier Y (2005). Development and validation of a brief version of the dyadic adjustment scale with a nonparametric item analysis model. Psychological Assessment, 17(1), 15–27. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkadi A, Kristiansson R, Oberklaid F, & Bremberg S (2008). Fathers' involvement and children's developmental outcomes: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatrica, 97(2), 153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00572.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Altenburger LE, Settle TA, Kamp Dush CM, Sullivan JM, & Bower DJ (2014). Expectant fathers’ intuitive parenting: Associations with parent characteristics and postpartum positive engagement. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35, 409–421. 10.1002/imhj.21468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Brown GL, Cannon EA, Mangelsdorf SC, & Sokolowski MS (2008). Maternal gatekeeping, coparenting quality, and fathering behavior in families with infants. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 389–398. 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, & Fagan J (2020). The evolution of fathering research in the 21st century: Persistent challenges, new directions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82, 175–197. 10.1111/jomf.12645 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Mangelsdorf SC, Frosch CA, & McHale JL (2004). Associations between coparenting and marital behavior from infancy to the preschool years. Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 194–207. 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theran SA, Levendosky AA, Bogat AG, & Huth-Bocks AC (2005). Stability and change in mothers' internal representations of their infants over time. Attachment & Human Devlopment, 7(3), 253–268. doi: 10.1080/14616730500245609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Egeren LA, & Hawkins DP (2004). Coming to terms with coparenting: Implications of definition and measurement. Journal of Adult Development, 11(3), 165–178 10.1023/B:JADE.0000035625.74672.0b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeswijk CM, Maas AJ, Rijk CH, & van Bakel HJ (2014). Fathers’ experiences during pregnancy: Paternal prenatal attachment and representations of the fetus. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15(2), 129–137. doi: 10.1037/a0033070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zvara BJ, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, & Dush CK (2013). Fathers' involvement in child health care: associations with prenatal involvement, parents' beliefs, and maternal gatekeeping. Family Relations, 62(4), 649–661. doi: 10.1111/fare.12023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]