ABSTRACT

The intrinsic mechanism of the thermotolerance of Kluyveromyces marxianus was investigated by comparison of its physiological and metabolic properties at high and low temperatures. After glucose consumption, the conversion of ethanol to acetic acid became gradually prominent only at a high temperature (45°C) and eventually caused a decline in viability, which was prevented by exogenous glutathione. Distinct levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), glutathione, and NADPH suggest a greater accumulation of ROS and enhanced ROS-scavenging activity at a high temperature. Fusion and fission forms of mitochondria were dominantly observed at 30°C and 45°C, respectively. Consistent results were obtained by temperature upshift experiments, including transcriptomic and enzymatic analyses, suggesting a change of metabolic flow from glycolysis to the pentose phosphate pathway. The results of this study suggest that K. marxianus survives at a high temperature by scavenging ROS via metabolic change for a period until a critical concentration of acetate is reached.

IMPORTANCE Kluyveromyces marxianus, a thermotolerant yeast, can grow well at temperatures over 45°C, unlike Kluyveromyces lactis, which belongs to the same genus, or Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is a closely related yeast. K. marxianus may thus bear an intrinsic mechanism to survive at high temperatures. This study revealed the thermotolerant mechanism of the yeast, including ROS scavenging with NADPH, which is generated by changes in metabolic flow.

KEYWORDS: thermotolerant yeast, thermotolerance, transcriptome analysis, reactive oxygen species, NADPH, acetic acid, Kluyveromyces marxianus

INTRODUCTION

Kluyveromyces marxianus, a thermotolerant yeast, can grow well at temperatures over 45°C, unlike Kluyveromyces lactis, which belongs to the same genus, or Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is a closely related yeast in hemiascomycetous yeasts. K. marxianus may thus have an intrinsic mechanism to survive at high temperatures in addition to its efficient fermentation ability with various sugars and its short doubling time (1–3). The thermotolerance of K. marxianus enables high-temperature fermentation (HTF), which can provide benefits, including reductions of cooling costs and the prevention of contamination by other microbes (4–6), and attention has therefore been given to K. marxianus for industrial applications (3).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can induce oxidative stress, are mainly generated by the leakage of electrons from the respiratory chain in mitochondria (7). In S. cerevisiae, electron leakage is enhanced at high temperatures due to the structural instability of the mitochondrial membrane (8) or by an increase in the respiration rate (9). Low levels of ROS are scavenged by nonenzymatic and enzymatic antioxidizing agents such as glutathione (GSH), thioredoxin (TRX), superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidases, but high levels of ROS cause the oxidation of intracellular components such as DNA, protein, and lipid and induce apoptosis (10, 11). Oxidative stress is a trigger of mitophagy (12, 13) and is also involved in heat-induced cell death (14). Under oxidative stress conditions, cells activate the production of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) that is required for the regeneration of GSH or a reduced form of TRX (15), which is mainly produced by the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) (16). NADP+/NADPH is thus used as an indicator of oxidative stress and cell death (17, 18).

The mitochondrion, which is an organelle that is responsible for various important tasks, including oxidative phosphorylation in eukaryotes, exhibits two types of morphology, fusion and fission, which are regulated by several vital genes (19) in response to nutrient depletion or stress (20). Damaged mitochondria are segregated in fission and degraded by mitophagy, by which mitochondrial homeostasis is maintained (20–22).

In S. cerevisiae, high temperature causes the accumulation of acetic acid and trehalose (23, 24). The former induces mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis (25, 26), and the latter contributes to protein stabilization and inhibits apoptosis (27, 28). In K. marxianus, several genes for enzymes in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle are downregulated and oxidative stress response genes are upregulated at a high temperature (29), indicating the possibility that mitochondrial metabolism is adapted to high-temperature conditions to avoid suffering from oxidative stress. However, the physiological and metabolic differences between low and high temperatures remain to be elucidated.

To understand the strategy of K. marxianus for survival at high temperatures, we first investigated cell growth, metabolites, and intracellular antioxidants in detail under long-term and short-term cultivation conditions. Under the former conditions, acetate that accumulated above a critical concentration caused a decline in cell survival, and the trigger of the drastic event was investigated by focusing on ROS, GSH, and NADPH levels. Under the latter conditions, changes in the dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration (DOC) and mitochondrial morphology were focused on. Temperature upshift experiments were also carried out, and the results revealed that the accumulation of ROS within a short time after the temperature shift caused a remarkable increase in the ratio of the fission form to the fusion form of mitochondria. On the basis of these findings and transcriptomic and enzymatic data, the metabolic change after a temperature upshift is discussed.

RESULTS

HTF and effect of acetic acid on K. marxianus.

K. marxianus bears capabilities for growth and fermentation at a high temperature as well as at a low temperature. To understand the fermentation ability of K. marxianus under different temperature conditions, the cell growth and metabolites of K. marxianus DMKU 3-1042 were compared in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium at 30°C and 45°C for 72 h as a long-term cultivation (Fig. 1A to D). The cell turbidity, consumption of glucose, and ethanol production at 45°C were lower than those at 30°C. The concentration of ethanol peaked at 10 to 12 h and then gradually decreased under both temperature conditions, and the decrease was faster at 45°C until 36 h and then slowed down. Concomitantly, the concentration of acetate increased at 45°C until 48 h, and the concentration was then maintained at 0.5% (wt/vol). In agreement with the accumulation of acetate, the pH of the culture medium greatly dropped (Fig. 1E). At 30°C, the level of ethanol continuously decreased, but the level of acetate was not as high as that at 45°C. Notably, the number of CFU sharply decreased at 45°C after the accumulation of acetate became about 0.4% (wt/vol) but did not decrease at 30°C (Fig. 1F).

FIG 1.

Ethanol fermentation of K. marxianus in long-term cultivation at 30°C and 45°C. Cells were cultivated in 2% YPD medium at 30°C (open circles) and 45°C (open triangles) under shaking conditions. (A) The cell density was estimated by measuring the turbidity at the OD660. (B to D) Concentrations of glucose (B), ethanol (C), and acetate (D) were determined by HPLC. (E and F) pH (E) and CFU (F) were also determined as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars represent standard deviations (SD) for triplicate experiments.

The decrease in the number of CFU suggested that the accumulation of acetate over a critical concentration caused cell death. To investigate this possibility, acetic acid and HCl were exogenously added to the culture medium at 45°C (Fig. 2). The number of CFU was greatly decreased and the level of ROS was increased by the addition of 0.2% or 0.4% (wt/vol) acetic acid but was not changed by the addition of HCl, which decreased the pH to 4.2, being pH equivalent to 0.4% (wt/vol) acetic acid. Therefore, the results suggested that exogenous acetic acid enhances the elevation of the level of ROS and the decrease in the number of CFU and that cell death is caused by the accumulation of acetate but not by a pH reduction of the culture medium.

FIG 2.

Effects of acetic acid on cell viability and cellular levels of ROS of K. marxianus at 45°C. Cells were cultivated in 2% YPD medium supplemented with acids at 45°C under shaking conditions at 160 rpm. Six hours after inoculation, acids, including 0.118% (wt/vol) HCl (open circles), 0.2% (wt/vol) acetic acid (closed squares), and 0.4% (wt/vol) acetic acid (open squares), were added or not added (closed circles). (A and B) CFU (A) and pH (B) were determined as described in the legend of Fig. 1. (C) Relative cellular levels of ROS were measured at log phase (6 h) as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars represent SD for triplicate experiments. *, P value of <0.05.

Levels of ROS, GSH, and NADPH under high-temperature conditions.

Since it was previously shown that the levels of ROS remarkably increase under high-temperature conditions in S. cerevisiae (30), cellular and mitochondrial levels of ROS were determined in the log phase (6 h) and in the acetate accumulation phase (36 h) at 30°C and 45°C (Fig. 3A and B). At 6 h, the cellular and mitochondrial levels of ROS at 45°C were 4.0-fold and 10.9-fold higher than those at 30°C, respectively. At 36 h, the cellular and mitochondrial levels of ROS at 45°C were 5.9-fold and 3.1-fold higher than those at 30°C, respectively. The levels of ROS were significantly higher in the acetate accumulation phase, during which the number of CFU was decreasing. These results suggest that heat stress increases cellular and mitochondrial levels of ROS. On the other hand, the cellular GSH and glutathione disulfide (GSSG) levels in the log phase at 45°C were lower than those at 30°C, and the levels in the acetate accumulation phase at 45°C were much lower (Fig. 3C to E), although the ratios of GSH to GSSG at 45°C in both phases were almost the same as those at 30°C, indicating that the sum of the GSH and GSSG values at 45°C is low compared to that at 30°C. Therefore, it is likely that either low synthesis or high degradation of GSH occurs at a high temperature in comparison to that at a low temperature, although the ratio of GSH/GSSG is maintained.

FIG 3.

Cellular and mitochondrial levels of ROS and levels of glutathione and NADPH of K. marxianus at 30°C and 45°C. Cells were cultivated in 2% YPD medium at 30°C and 45°C under shaking conditions for 6 h or 36 h. (A and B) Cellular (A) and mitochondrial (B) levels of ROS at 6 h or 36 h were estimated as described in the legend of Fig. 2. White and gray columns represent levels of ROS at 30°C and 45°C, respectively. (C to H) GSH (C), GSSG (D), the GSH/GSSG ratio (E), NADP+ (F), NADPH (G), and the NADPH/NADP+ ratio (H) were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars represent SD for triplicate experiments. *, P value of <0.05.

Since the enzymatic conversion of ethanol to acetic acid generates NADPH as a source of reducing equivalents for the regeneration of GSH, it is assumed that acetic acid is produced to generate NADPH for the removal of ROS. To examine this assumption, NADPH and NADP+ levels of the cells were determined in the log and acetate accumulation phases at 30°C and 45°C (Fig. 3F to H). In both phases, the NADPH levels at 45°C were higher than those at 30°C. Notably, at 45°C, the ratio of NADPH/NADP+ in the acetate accumulation phase was lower than that in the log phase, presumably indicating the requirement for a larger amount of NADPH in the acetate accumulation phase for the removal of ROS. However, considering a report by Zhang et al. (31), the ratio of NADPH/NADP could be low, so it cannot be denied that the method used in this study underestimated the amount of NADPH.

Effects of exogenous GSH on acetate accumulation and cell viability under high-temperature conditions.

To reduce the oxidative stress level in cells, GSH was added to the culture medium, and ethanol consumption, acetate accumulation, and cell viability were examined (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The maximum concentration of acetate in the presence of 4 mM GSH was 0.16% (wt/vol), which was much lower than that in the presence of 0 or 1 mM GSH. The addition of 4 mM GSH kept the CFU at a high level and reduced the ethanol consumption speed compared to those with the addition of 0 or 1 mM GSH. These results indicate that exogenous GSH slows ethanol consumption, limits acetate accumulation, and prevents cell death at 45°C. Taken together, the results of the experiments with long-term cultivation suggest that the high temperature of 45°C causes the accumulation of ROS, which leads to the oxidation of ethanol to provide NADPH, resulting in the accumulation of acetate, which in turn leads to damage and death of cells. The provision of NADPH via ethanol oxidation may contribute to the prevention of ROS-induced cell death until the concentration of acetate reaches a critical level.

Analysis of fermentation at the early phase and mitochondrial morphology.

To further understand metabolic differences at high and low temperatures, short-term cultivation was also performed (Fig. 4 and 5 and Fig. S2). At 30°C, the dissolved oxygen concentration (DOC) decreased to the minimum level within 4 h, with almost no consumption of glucose added, followed by increasing and decreasing waves with a peak at around 17 h (Fig. 4A). The DOC goes to zero before glucose starts to be consumed, which could be due to the respiration of intracellular reserves, including glycogen or trehalose. Glucose consumption continued until 10 h with the maximum ethanol concentration at 10 h (Fig. 5B and C). The increase in the DOC at 30°C at about 14 h presumably represents the diauxic lag when the cells have ceased respirofermentative catabolism of glucose (at 10 h) but do not start to respire ethanol until after 12 h and then only slowly. At 45°C, the decrease in the DOC was much slower than that at 30°C, and no wave was observed (Fig. 4A and Fig. 5E). Ethanol fermentation appeared to be different at low and high temperatures in response to DOCs (Fig. 5C and E). Obvious glucose consumption and ethanol accumulation were observed after the DOC decreased to a minimum level at 30°C, while glucose was fermented at a relatively high DOC at 45°C (Fig. 5B, C, and E). The former could be due to the respiration of intracellular glycogen or trehalose.

FIG 4.

Distinct characteristics of K. marxianus at 30°C and 45°C. Cells were cultivated in 2% YPD medium at 30°C and 45°C under shaking conditions. (A) The DOC was measured by a DO sensor (open circles, 30°C; open triangles, 45°C). (B) NADH oxidase activity was determined with samples taken at 6 h and 24 h. Error bars represent SD for triplicate experiments. *, P value of <0.05.

FIG 5.

Ethanol fermentation of K. marxianus during short-term cultivation at 30°C and 45°C and effects of temperature upshift on K. marxianus. Cells were cultivated in 2% YPD medium at 30°C (open circles), 45°C (open triangles), or 30°C to 45°C (temperature upshift) (open squares) under shaking conditions. The temperature upshift was performed by transferring flasks from a 30°C incubator to a 45°C incubator 4 h after incubation at 30°C. (A to D) Cell density (A) and concentrations of glucose (B), ethanol (C), and acetate (D) (percent, wt/vol) were determined as described in the legend of Fig. 1. (E) The DOC was measured by a DO sensor. Error bars represent SD for triplicate experiments.

Surprisingly, the distinct mitochondrial morphologies at 30°C and 45°C were observed at 3 h, 6 h, and 24 h (Fig. S2), but mitochondria were not clearly visible at 48 h under the conditions at 45°C (data not shown), at which time the number of CFU declined. NADH oxidase activities at 6 h and 24 h at 45°C were found to be higher than those at 30°C (Fig. 4B), possibly being related to morphological changes of mitochondria and/or a greater accumulation of ROS at 45°C. Notably, there was almost no difference in the concentrations of acetate until 8 h at 30°C and 45°C, although the glucose and ethanol levels were different (Fig. 5), indicating the possibility that the acetate level in the culture medium may not be responsible for the accumulation of ROS or for the generation of the mitochondrial fission form.

Effects of temperature upshift on cell growth and metabolism.

To further understand the metabolic differences at 30°C and 45°C, cell growth and metabolites were examined when the cultivation temperature was increased to 45°C after a 4-h cultivation at 30°C and compared with those under constant temperature conditions at 30°C and 45°C (Fig. 5). This temperature upshift or the transfer of cells pregrown at 30°C to medium at 45°C may cause a heat shock response, which triggers changes in transcription and metabolism. Oxygen consumption was delayed almost immediately after the temperature upshift, and the profile was closer to that under the 45°C constant conditions, but the profiles of cell turbidity, glucose consumption, and ethanol accumulation were almost the same as those under the 30°C constant conditions. Therefore, the temperature upshift may affect oxygen consumption without having negative effects on cell growth, glucose uptake, and ethanol production. The high DOC immediately after the temperature upshift may be due to a brief pause in shaking during the transfer of flasks from a 30°C incubator to a 45°C incubator.

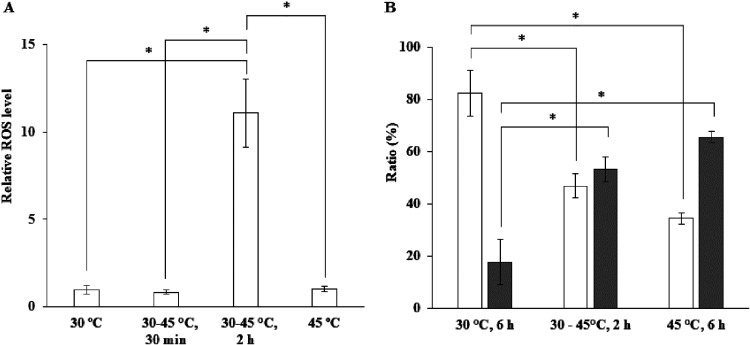

On the other hand, no significant effect of the temperature upshift on acetate accumulation was observed until 4 h after the upshift, and its profile was similar to the profiles under the 30°C and 45°C constant conditions, but an increase in ROS occurred until 2 h after the upshift, and the level of ROS at 2 h was 11-fold higher than that under the 45°C constant conditions (Fig. 6A). Therefore, it is assumed that ROS generated by the upshift are removed by means other than the process of conversion of ethanol to acetic acid.

FIG 6.

Effects of temperature upshift on cellular levels of ROS and mitochondrial morphology. Cells were cultivated in 2% YPD medium at 30°C, 45°C, or 30°C to 45°C under shaking conditions. The temperature upshift was performed as described in the legend of Fig. 5. (A) Relative levels of ROS were determined 30 min (30-45°C, 30 min) or 2 h (30-45°C, 2 h) after the temperature upshift. (B) Mitochondrial morphology was observed 2 h (30-45°C, 2 h) after the temperature upshift, and the ratios were determined by observation of 250 cells. White and gray columns represent fusion and fission forms of mitochondria, respectively. Determination of the cellular levels of ROS and observation of mitochondrial morphology were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars represent SD for triplicate experiments. *, P value of <0.05.

Observations of mitochondrial morphology in addition to measurements of ROS were carried out 2 h or 3 h after the temperature upshift following a 4-h cultivation at 30°C (Fig. 6B and Fig. S3). Surprisingly, the temperature upshift caused an increase in fission mitochondria, and fusion and fission forms of mitochondria in cells were 47% and 53%, respectively. The ratio of fission to fusion forms remarkably increased compared to that under the 30°C constant conditions and was close to that under the 45°C constant conditions (Fig. 6B).

Transcriptome analysis at the transition from a low temperature to a high temperature.

The greatly altered profiles of ROS and DOCs and the change in mitochondrial morphology at the transition phase of temperature (Fig. 5 and 6) motivated us to perform genome-wide gene expression analysis (RNA sequencing [RNA-Seq]) under two different conditions. Under one condition, cells were grown in YPD medium at 30°C for 4 h and further grown at 45°C for 30 min (4H30-30M45) or 2 h (4H30-2H45). Under the other condition, cells were grown in YPD medium at 30°C for 6 h (6H30). The RPKM (reads per kilobase of exon per million) value of each gene was estimated as transcript abundance. The difference in the expression of each gene in 4H30-30M45 or 4H30-2H45 from that in 6H30 was reflected as the ratio of the RPKM value in 4H30-30M45 or 4H30-2H45 to that in 6H30. To further explore the transcriptional changes, analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was conducted on the basis of the RNA-Seq data. DEGs showed significant changes at the transcription level with a log2 fold change of greater than 1 and a log2 fold change of less than −1 and an adjusted P value (Padj) of less than 0.05 (Fig. S4). DEGs in 4H30-30M45 consisted of 2,069 genes, including 1,076 upregulated and 993 downregulated genes. DEGs in 4H30-2H45 consisted of 2,119 genes, including 1,054 upregulated and 1,065 downregulated genes. In the up- and downregulated DEGs, 817 genes and 773 genes, respectively, were shared between the 4H30-30M45 and 4H30-2H45 conditions (Fig. S5). These data for DEGs were used for gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis (Tables S1 to S12).

In 4H30-30M45, 62 DEGs were highly significantly upregulated (>4 log2). They included genes for heat shock proteins, cochaperone proteins, and many hypothetical or uncharacterized proteins (Table S1). GO enrichment analysis of DEGs (>2 log2) showed that genes for ribonucleoprotein complex biogenesis, ribosome biogenesis, rRNA processing, the rRNA metabolic process, and maturation of single-subunit (SSU) rRNA as the top five were significantly enriched in the biological process (Table S2). KEGG pathway analysis revealed that pathways for protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, the spliceosome, the biosynthesis of secondary metabolism, the biosynthesis of antibiotics, the meiosis and MAPK signaling pathway, and the peroxisome were in the top ranks (Table S3). Moreover, pathways for lipid metabolism (glycerolipid, sphingolipid, glycerophospholipid, and fatty acid), GSH metabolism, and mitophagy were also listed. On the other hand, 89 DEGs were highly significantly downregulated (less than −4 log2), including genes for ribosomal proteins and transporters (Table S4). GO enrichment analysis revealed that many terms were related to biosynthetic processes and metabolic processes (Table S5). In the KEGG pathway analysis, pathways for the ribosome, the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, the biosynthesis of antibiotics, the biosynthesis of amino acids, and carbon metabolism were highlighted (Table S6). In addition, pathways for glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, steroid biosynthesis, the cell cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, fatty acid metabolism, and autophagy were listed.

In 4H30-2H45, 60 DEGs were highly significantly upregulated (>4 log2). They included genes for heat shock proteins, cochaperone proteins, and many hypothetical proteins (Table S7), and 47 of these genes were included in the list of 4H30-30M45 (Table S1). Seven out of eight genes for heat shock proteins and cochaperone proteins in 4H30-30M45 were shared with those in 4H30-2H45. GO enrichment analysis showed that the top 20 terms were nearly the same as those of upregulated DEGs in 4H30-30M45 (Table S8). In the KEGG pathway analysis, all pathways except for one pathway (one-carbon pool by folate) were listed in those of the upregulated DEGs in 4H30-30M45 (Table S9). On the other hand, 31 DEGs were highly significantly downregulated (less than −4 log2). They included genes for carbon metabolism (Table S10), and 15 of these genes were also listed as downregulated DEGs in 4H30-30M45 (Table S4). Only 1 of the 50 genes for ribosomal proteins that were listed as downregulated DEGs in 4H30-30M45 (Table S4) was found in the list of 4H30-2H45. GO enrichment analysis showed that the top 18 terms except for 1 term were included in the top 34 downregulated DEGs in 4H30-30M45 (Table S11). In the KEGG pathway analysis (Table S12), 32 pathways in the table were also listed as downregulated DEGs in 4H30-30M45 (Table S6). Therefore, upregulated and downregulated DEGs in 4H30-30M45 overlapped those of 4H30-2H45 well, except for many downregulated genes for ribosomal proteins in 4H30-30M45.

To understand the metabolic change around the central metabolic pathway caused by a temperature upshift, transcriptomic data related to glycolysis, the PPP, the TCA cycle, and cellular and mitochondrial oxidative stress responses were focused on (Fig. 7A and B and Fig. S6A and B). RAG2, RAG5, PFK1, PFK2, FBA1, TPI1, GAP1, GAP3, PGK, GPM1, ENO, and PYK1 for glycolysis and CIT1, ACO2b, LSC1, LSC2, FUM1, and MDH1 for the TCA cycle were downregulated in 4H30-30M45 and/or 4H30-2H45. In contrast, GLK1, FBP1, and GPM3 for glycolysis; SOL1 and RKI1 for the PPP; ADH1, KLMA_40624 (ADH), and ADH6 for catalysis between ethanol and acetaldehyde in the cytosol; ADH4a, ALD4, and ACS1 for catalysis between ethanol and acetyl-CoA in mitochondria; and CIT3, IDP1, and SDH4 for the TCA cycle were upregulated in 4H30-30M45 and/or 4H30-2H45. On the other hand, genes for the oxidative stress response were upregulated (Fig. S6A and B) as expected, probably reflecting the accumulation of ROS under the conditions tested.

FIG 7.

Transcriptome analysis of the effect of temperature upshift on K. marxianus. Cells were cultivated in YPD medium at 30°C for 4 h under shaking conditions, and flasks were transferred from a 30°C incubator to a 45°C incubator for further culture for 30 min (4H30-30M45) (orange) or 2 h (4H30-2H45) (red). The control was the culture at 30°C for 6 h under shaking conditions (6H30) (yellow). Total RNA was then isolated, purified, and subjected to RNA-Seq analysis. The y axis of each graph represents the reads per kilobase of exon per million (RPKM) of each gene under the indicated conditions. Data for central metabolism (A) and the TCA cycle (B) are shown. The RPKM value of each gene represents the average value from two independent experiments. G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; F6P, fructose-6-phosphate; FDP, fructose 1,6 bisphosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; DHA, dihydroxyacetone; GAP, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; 1,3-DPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; 2PG, 2-phosphoglycerate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PYR, pyruvate; 6P1,5R, 6-phospho-D-glucono-1,5-lactone; 6PG, 6-phosphogluconate; Ru5P, ribulose-5-phosphate; R5P, ribose-5-phosphate; Xu5P, xylulose-5-phosphate; E4P, erythrose-4-phosphate; S7P, sedoheptulose-7-phosphate; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NADP, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; Q, quinone; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ADP, adenosine diphosphate.

Since a mitochondrial morphological change that is crucial for the maintenance of functional mitochondria under stress conditions (20) was observed following the temperature upshift, genes for mitophagy and autophagy were focused on. As mitophagy-related genes, ATG32 and FIS1 were upregulated in both 4H30-30M45 and 4H30-2H45, and SSK1, WSC3, and SLG1 were downregulated in 4H30-2H45 (Tables S13 and S14). As autophagy-related genes, RAS2, GCN4, and PCL5 were downregulated in 4H30-30M45 (Table S14). Gcn4 regulates nonselective autophagy activity through ATG transcription; for example, Gcn4 activates the expression of ATG1, ATG13, and ATG14 during amino acid starvation (32, 33). Such uncoordinated expression of genes for mitophagy and downregulation of genes for autophagy may contribute to the endurance of K. marxianus at a high temperature, which is discussed below. In addition, the longevity-regulating pathway in both 4H30-30M45 and 4H30-2H45 (Tables S3 and S9) was listed. This pathway commonly consists of 5 genes, SSA3, HSP78, and HSP104 for heat shock proteins and SOD1 and SOD2 for superoxide dismutase, reflecting the requirement for protection from heat shock and oxidative stress at high temperatures.

Activity of several enzymes at the transition from a low temperature to a high temperature.

As several lines of evidence described above have shown, higher NADPH levels at 45°C than those at 30°C, the downregulation of most genes for glycolysis by a temperature upshift, and the upregulation of some genes for gluconeogenesis and the PPP imply metabolic changes. To confirm these metabolic changes, the activity of several enzymes in glycolysis and the PPP was determined using supernatants after the ultracentrifugation of cell extracts (Fig. 8). The change in the activity of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase after the temperature upshift was almost consistent with the change in the transcription of its gene, although the decrease in activity was delayed compared to that of transcription. The activity patterns of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase were also in good agreement with their transcription patterns. Notably, the activities of fructose-1,6-diphosphatase in 4H30-2H45 and 6H45 were higher than that in 6H30, and the activity level of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase was constant even after the temperature upshift. These findings suggest a metabolic flow to the PPP under elevated-temperature conditions. On the other hand, the activity of phosphoglucose isomerase was slightly decreased after the temperature upshift or at 45°C, although its transcription sharply declined, indicating the possibility that the enzyme is relatively stable, which may contribute to gluconeogenesis.

FIG 8.

Enzyme activity analysis of the effect of temperature upshift on K. marxianus. Cells were cultivated in YPD medium at 30°C for 4 h under shaking conditions, and flasks were transferred from a 30°C incubator to a 45°C incubator for further culture for 30 min (4H30-30M45) or 2 h (4H30-2H45). Cells were also cultivated in YPD medium at 30°C for 6 h (6H30) or at 45°C for 6 h (6H45) under shaking conditions. Cells were then harvested, and ultracentrifugation supernatants were prepared for enzyme assays as described in Materials and Methods. The activities of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (A) and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (B) in the PPP, of phosphoglucose isomerase (C) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (D) in glycolysis, and of fructose-1,6-diphosphatase in gluconeogenesis (E) were determined spectrophotometrically. Error bars represent SD for triplicate experiments. *, P value of <0.05.

DISCUSSION

In contrast to the physiological properties at 30°C, the acetate concentration at 45°C increased during long-term cultivation and exceeded a critical concentration of around 0.4% (wt/vol), which eventually resulted in a large reduction in the number of CFU (Fig. 1). Acetic acid, which is permeable to the cytoplasmic membrane as an undissociated acid, dissociates to protons and acetate anions inside cells, and the accumulation of protons lowers the intracellular pH, thereby leading to a great reduction of metabolic activity and, eventually, cell death (34, 35). The finding that exogenous GSH prevented the emergence of distinct properties of acetate accumulation and the reduction in the number of CFU (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) suggests that the accumulation of ROS is the cause of these properties. Considering the evidence that acetic acid induces programmed cell death depending on ROS (36), acetate accumulation may be a crucial factor responsible for the CFU reduction (Fig. 1). On the other hand, acetic acid production from ethanol by enzymatic reactions provides NADPH, which is involved in protection against the toxicity of ROS (15). Therefore, it is assumed that K. marxianus produces acetic acid from ethanol after glucose depletion in response to the accumulation of ROS at high temperatures, keeping the levels of ROS below toxic levels (Fig. 9A and B).

FIG 9.

Models of metabolic flow at a high temperature (HT) in K. marxianus. (A) Log phase, in which glucose is present in the culture. (B) Acetate accumulation phase, in which there is no glucose in the culture.

In S. cerevisiae, the intracellular formation of ROS increases when the temperature rises to 42°C (30), and GSH decreases with exposure to H2O2 (37). Similarly, in K. marxianus, cellular and mitochondrial levels of ROS in the log phase at 45°C were higher than those at 30°C (Fig. 3A and B), and GSH concentrations in both the log and acetate accumulation phases were lower at 45°C than at 30°C, and the difference between GSH concentrations at 45°C and 30°C in the acetate accumulation phase was much larger than that in the log phase (Fig. 3C). The low level of GSH at 45°C appeared to be related to the increase in ROS because GSH is required for the repair of oxidative damage. These results suggest that the high temperature is responsible for the increases in the cellular and mitochondrial levels of ROS and the decrease in GSH in K. marxianus. Probably to compensate for the decrease in GSH, NADPH levels in both the log and acetate accumulation phases at 45°C were higher than those at 30°C (Fig. 3G).

In the temperature upshift experiments, a delay in oxygen consumption similar to that under the 45°C constant conditions was observed immediately after the upshift, but the patterns of cell proliferation, glucose consumption, and ethanol production were hardly changed from those under the 30°C constant conditions (Fig. 5B and C). The temperature transition resulted in a change of mitochondrial morphology with an increase in the fission form ratio and in an elevation of the level of ROS to a level about 11-fold higher than that under the 30°C constant conditions (Fig. 6). Given the results of studies showing that mitochondria tend to change their morphology with several stresses (20) and that ROS induce mitochondrial fission (38), it is assumed that the accumulation of ROS is the cause of the mitochondrial morphological change in K. marxianus. Moreover, the fission form ratio was close to that under the 45°C constant conditions, although the levels of ROS were very different (Fig. 6A and B). Another candidate for triggering the mitochondrial morphological change is acetic acid, but for about 4 h after the temperature upshift, there was almost no difference in the acetate concentration in the culture medium from that under the 30°C constant conditions (Fig. 5D). Therefore, these findings imply that the mitochondrial morphological change is caused not by acetate accumulation but by exposure to ROS. Notably, given that respiratory-active fusion mitochondria may generate more ROS than fission mitochondria (20), fission mitochondria could be a beneficial form for the yeast at high temperatures in terms of keeping ROS levels low.

K. marxianus was able to ferment with glucose at 45°C to an extent close to that at 30°C despite a high level of ROS and the mitochondrial morphological change. These facts led us to conduct transcriptome analysis with samples obtained under temperature upshift conditions to further understand the mechanism of survival at high temperatures and the differences between low- and high-temperature metabolisms. The highly significant response to the temperature upshift appeared to be a general heat shock, that is, the upregulation of genes for heat shock proteins and chaperones and the downregulation of genes for ribosomal proteins and rRNA processing-related metabolism (Tables S1, S4, S7, and S10). Such downregulation of genes for ribosomal proteins has been reported for Escherichia coli at a critical high temperature (39), which may be for saving energy. As a significant response, genes for the pathways of GSH biosynthesis and lipid metabolism were upregulated, and genes for the pathways of amino acid synthesis, glycolysis, the TCA cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, and the PPP were downregulated (Tables S3, S6, S9, and S12). Considering the fact that the cells are able to grow and survive at 45°C after inoculation of cells precultured at 30°C and the fact that the tendency for the upregulation and downregulation of genes for the central metabolic pathway is in close agreement with that of a 6-h culture at 45°C (29), such an alteration in transcription in response to a temperature upshift may reflect metabolic changes that are presumably required for the growth and survival of K. marxianus at 45°C.

In mitochondrial metabolism, ADH4a, ALD4, and ACS1 for catalysis between ethanol and acetyl-CoA and CIT3 and IDP1 for the TCA cycle, some of which encode enzymes to generate NADPH, were upregulated at the temperature upshift (Fig. 7B) or under 6-h 45°C constant conditions (29). In the cytosol, downregulation of RAG2, PFK1, and PFK2 and upregulation of GLK1, FBP1, and SOL1, most of which were significantly changed 2 h after the temperature upshift, were found (Fig. 7A). Especially, the strong negative and positive regulations of RAG2 for glucose-6-phosphate isomerase and FBP1 for fructose-1,6-diphosphatase, respectively, might have an impact on metabolic flow, nearly equivalent to that of a RAG2 (PGI1)-disrupted mutant (40), and lead to a reduction in the flow of glycolysis and, consequently, an increase in the flow of the PPP despite the moderately decreased expression of many genes for the PPP under the temperature upshift conditions. These expression changes of genes for glycolysis, the PPP, and gluconeogenesis roughly agreed with the activity changes of the corresponding enzymes tested in these pathways. In particular, the activity of fructose-1,6-diphosphatase in gluconeogenesis was increased, the activity of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in the PPP was maintained, and the activity of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was reduced, suggesting enhanced metabolic flow to the PPP and a pentose phosphate cycle consisting of the PPP and a reverse reaction in glycolysis from glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate to glucose-6-phosphate. The switch of the metabolic flow allows cells to produce NADPH as a reducing power for the removal of ROS. On the other hand, ALD4 in mitochondria, but not ALD in the cytosol, was upregulated in the temperature upshift experiments, while ALD2 and ALD6 in the cytosol, but not ALD in mitochondria, were upregulated under the 45°C constant conditions, implying that the mitochondrial Ald(s) and cytosolic Ald(s) are involved in the production of NADPH immediately after and shortly after a temperature rise, respectively.

K. marxianus, which is a Crabtree-negative species, produces a low level of ethanol in the presence of sufficient glucose under aerobic conditions, in contrast to S. cerevisiae, which is a Crabtree-positive species (41). However, at 45°C, glucose consumption and ethanol accumulation started with a relatively high DOC, and the ethanol level became nearly equivalent to that at 30°C (Fig. 5). Such Crabtree-positive-like fermentation at 45°C, at least at the beginning of fermentation (later, the DOC became very low), may be due to the regulation of the expression of specific genes. S. cerevisiae produces a high level of ethanol even under aerobic conditions via the reduction of the acetyl-CoA synthetic pathway and the inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase (42). Similarly, ADH2 and ALD2 for the acetyl-CoA synthetic pathway and PDA1 and PDB1 for pyruvate dehydrogenase were downregulated at 45°C (Fig. 7A and B). This downregulation and the reduced expression of FUM1, MDH1, and CIT2 for the TCA cycle contribute to the accumulation of pyruvate, thereby increasing ethanol production at a high temperature.

In conclusion, this study was conducted to understand the mechanism of thermotolerance that is distinct from that at a low temperature in K. marxianus. The yeast was exposed to relatively high levels of ROS at a high temperature but maintained levels of CFU for about 36 h. The accumulation of ROS up to a level that threatens cell survival may be prevented by the ROS-scavenging pathway with NADPH, which is generated mainly by the PPP in the presence of glucose and subsidiarily by the catalytic reactions of Adhs-Alds. Relatively high NADH oxidase activity and an increase in the fission form of mitochondria, which may allow dispersal inside cells, might reduce the intracellular oxygen concentration to suppress the generation of ROS. On the other hand, maintenance of the DOC at the lowest level was observed after about 9 h at 45°C. When glucose is consumed and the production of NADPH by the PPP ceases, catalytic reactions of Adhs-Alds may become the main NADPH supplier because of the presence of a sufficient amount of ethanol. However, insufficient oxygen and the downregulation of vital genes for the TCA cycle may reduce the oxidation of acetic acid so that acetic acid accumulates to more than a critical level. At 45°C, ethanol consumption started when glucose was almost consumed, and concomitantly, acetate accumulation was promoted (Fig. 1), suggesting that glucose is a crucial factor for avoiding acetic acid accumulation and CFU reduction in addition to ethanol consumption. Therefore, ethanol production by HTF for industrial applications may require maintaining at least low levels of glucose (sugar) in the medium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strain, medium, and cultivation.

The yeast strain used in this study was K. marxianus DMKU 3-1042 (43), which has been deposited in the NITE Biological Resource Center (NBRC) under deposit numbers NITE BP-283 and NBRC 104275. Cells were precultured in YP (1% yeast extract and 2% peptone) medium containing 2% glucose (YPD) at 30°C for about 12 h under reciprocally shaking conditions at 160 rpm. The preculture was inoculated at 1% into YPD medium, and culture was carried out under reciprocally shaking conditions at 160 rpm.

Analytical methods.

Cells were precultured in YPD at 30°C for about 12 h, and 1% of the preculture was inoculated into YPD medium for cultivation at 30°C or 45°C. Cell growth and pH were determined by measuring the optical density at 660 nm (OD660) using a UV-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometer (Shimazu, Japan) and a pH meter (Horiba, Japan), respectively. Cell viability was determined as CFU by counting the number of colonies on YPD agar plates. During cultivation, samples were taken, diluted, spread onto plates, and subjected to incubation at 30°C, and the colonies that formed on the plates were enumerated after 48 h. Concentrations of glucose, ethanol, and acetate in the culture were determined on a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Hitachi, Japan) consisting of a Hitachi model D-2000 Elite HPLC system manager, column oven L-2130, pump L-2130, autosampler L-2200, and refractive index (RI) detector L-2490 equipped with a GL-C610H-S Gelpack column (Hitachi Chemical, Japan) or UV detector L-2400 equipped with a GL-C610-H Gelpack column (Hitachi Chemical, Japan). The dissolved oxygen concentration (DOC) was measured by using a DO sensor of Fibox 3 (PreSens Precision Sensing GmbH), and its sensor chip was set up at the center of the bottom of a 100-mL flask. NADH oxidase activity was measured as described previously (44, 45).

Determination of cellular and mitochondrial levels of ROS.

Cellular and mitochondrial levels of ROS were determined with the cell-permeant fluorescent probe 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) (Funakoshi, Japan) and dihydrorhodamine 123 (Wako, Japan), respectively (46). During cultivation, samples were taken and incubated with 10 μM H2DCFDA or 10 μM dihydrorhodamine 123/1 × 107 cells for 1 h before collecting cells. The collected cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 4 mL of the same buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail set IV (Wako, Japan). The cells were then disrupted by passage through a French pressure cell press (16,000 lb/in2) and centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 10 min, and the fluorescence of the supernatant was measured by a Powerscan HT microplate reader (BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). The protein concentration was determined by the Lowry method (47).

Determination of levels of GSH and glutathione disulfide.

Glutathione levels were determined by a modified method described previously (48). During cultivation, cells were harvested, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in 4 mL of 1% 5-sulfosalicylic acid containing protease inhibitor cocktail set IV. The cells were disrupted by a French pressure cell press (16,000 lb/in2) and centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was used for the determination of glutathione levels. Total glutathione was determined by the addition of 30 μL of the lysate to 450 μL of the assay mixture [0.1 M potassium phosphate (pH 7.0), 1 mM EDTA, 0.03 mg/mL 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid), and 0.12 U of glutathione reductase]. The samples were mixed and incubated for 5 min at room temperature, and 150 μL of NADPH (0.16 mg/mL) was added to the mixture. The formation of thiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) was measured spectrophotometrically at 420 nm over a 5-min period. A standard curve was generated for each experiment using 0 to 0.5 nmol of GSH in 1% 5-sulfosalicylic acid. To measure glutathione disulfide (GSSG) levels, 200 μL of a lysate sample was derivatized by the addition of 4 μL of 97% 2-vinylpyridine, and the pH was adjusted by the addition of 4 μL of 25% triethanolamine. The samples were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation, the treated lysate was added to 300 μL of the assay mixture and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Next, 100 μL of NADPH (0.16 mg/mL) was added, and the amount of thiobis formed was measured. GSSG standards (0 to 0.5 nmol) were also treated with 2-vinylpyridine in a manner identical to that for the samples. The amount of GSH in each sample was determined by subtracting the amount of GSSG in the lysate from the total amount of glutathione.

Determination of NADPH and NADP+ levels.

NADPH and NADP+ levels were determined by an EnzyChrom NADP+/NADPH assay kit (BioAssay Systems). During cultivation, cells were harvested, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in NADPH or NADP+ extraction buffer included in the kit. The sample was then incubated at 65°C for 30 min. The amounts of NADPH and NADP+ were determined according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Observation of mitochondrial morphology.

The shape of the mitochondrial network in live cells was observed by microscopy. One hundred microliters of the culture was collected and mixed with MitoTracker red CMXRos (Molecular Probes) at a final concentration of 0.4 μM. The mixture was incubated at 30°C for 10 min to 20 min and subjected to observation by using a BX53 fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan) with its green excitation light. Approximately 250 cells were observed to determine the ratio of fusion to fission forms of mitochondria. The fission or fusion form as a mitochondrial form was decided by the number of mitochondria; mitochondria in a cell that contains more than 4 mitochondria are of the fission form, and mitochondria in a cell that contains 4 or fewer than 4 mitochondria are of the fusion form.

RNA-Seq analysis.

For RNA preparation, cell growth was performed under three different conditions. Cells were grown in YPD medium at 30°C for 4 h, the temperature was then increased to 45°C, and the cells were further incubated for 30 min or 2 h or continuously incubated at 30°C for 6 h. Total RNA was then isolated as described previously (49) and purified by using the RNeasy mini plus kit (Qiagen) according to the instructions supplied by the company. All conditions were duplicated. The purified RNA was subjected to RNA-Seq analysis by the Illumina NextSeq system. For RNA-Seq analysis, the K. marxianus genome sequence (GenBank accession numbers AP012213 to AP012221) was used. Reads per kilobase of exon per million (RPKM) values were estimated using the CLC genomics workbench (Qiagen). Extraction of DEGs was based on unique exon read values from CLC genomics workbench outputs using the DESeq2 R package. The resulting P values were adjusted using Benjamin-Hochberg’s method for controlling the false discovery rate. Genes with adjusted P values of less than 0.01 (Padj < 0.05) and log2 fold change values of greater than 1 or less than −1 were assigned as significant DEGs. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of significant DEGs was performed using the topGO R package. GO terms with P values of less than 0.01 were considered significantly enriched. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway mapping with these significant DEGs was performed by using KEGG analysis tools (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/).

Enzyme assay.

Cells were grown in YPD medium at 30°C for 4 h, the temperature was then increased to 45°C, and the cells were further incubated for 30 min and 2 h or continuously incubated at 30°C for 6 h or at 45°C for 6 h. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 9,000 × g at 4°C, washed with saline, and resuspended in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (KPB) (pH 7.0). The resuspended cells were subjected to a French pressure cell press (catalog number IL61801; SLM Aminco SLM Instruments Inc.) at 24,000 lb/in2 four times, followed by centrifugation at 9,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The resultant supernatant was further subjected to centrifugation at 100,000 × g at 4°C for 1 h. The supernatant was used as an ultracentrifugation supernatant for enzyme assays. The activities of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, phosphoglucose isomerase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and fructose-1,6-diphosphatase were determined spectrophotometrically (U-2000A spectrophotometer; Hitachi) according to methods reported previously (50–54). Glucose-6-phosphate, 6-phosphogluconate, fructose-6-phosphate, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, sodium arsenate, fructose-1,6-diphosphate, NADP, and NAD were purchased from Oriental Yeast Co. Ltd. (Japan), Oriental Yeast Co. Ltd., Nacalai Tesque (Japan), Cayman (Japan), Nacalai Tesque, Cayman, Oriental Yeast Co. Ltd., and Oriental Yeast Co. Ltd., respectively. For the assay of phosphoglucose isomerase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Oriental Yeast Co. Ltd. was used. For the assay of fructose-1,6-diphosphatase, phosphoglucose isomerase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Nacalai Tesque and Oriental Yeast Co. Ltd., respectively, were used.

Quantification and statistical analyses.

All experiments were performed independently at least three times, except for fluorescence microscopy and RNA-Seq analyses. For morphology observation by a fluorescence microscope, we chose a typical image from at least 10 random images. RNA-Seq analysis and its data analysis are described above. All of the data obtained by the determination of ROS, GSH, GSSG, NADPH, NADP+, NADH oxidase activity, and fission and fusion mitochondria were used to conduct an F test together with Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistics software version 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability.

All of the data were deposited in the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/dra/index-e.html) under accession number DRA010932.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Advanced Low Carbon Technology Research and Development Program, which was granted by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JPMJAL1106) (T.K., M.M., and M.Y.), and the e-ASIA Joint Research Program, which was granted by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JPMJSC16E5) (T.K., M.M., and M.Y.); the Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education of the Republic of Indonesia; the Agricultural Research Development Agency of Thailand; and the Ministry of Science and Technology of Laos and was partially supported by Core to Core Program A Advanced Research Networks, which was granted by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the National Research Council of Thailand, the Ministry of Science and Technology in Vietnam, the National University of Laos, the University of Brawijaya, and the Beuth University of Applied Science Berlin (T.K., M.M., N.L., and M.Y.) and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, MEXT/JSPS Kakenhi (25250028 and 16H02485 to M.Y.).

We thank K. Matsushita, T. Yakushi, and N. Kataoka for their helpful discussion.

T.K. and M.Y. conceptualized the experiments. T.T. and S.N. performed and analyzed most of the experiments under the supervision of T.K. and M.Y. S.N., S.P., and M.M. performed experiments under long-term cultivation conditions. T.T. and N.L. performed experiments under short-term cultivation conditions. T.T. and S.P. under the supervision of I.M. performed the observation of mitochondrial morphology. T.T., S.P., T.K., and M.Y. were involved in transcriptome analysis. S.L. provided the parental strain and its physiological information. M.Y. wrote the original manuscript, with contributions from the other authors.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Mamoru Yamada, Email: m-yamada@yamaguchi-u.ac.jp.

Hideaki Nojiri, University of Tokyo.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rodrussamee N, Lertwattanasakul N, Hirata K, Suprayogi, Limtong S, Kosaka T, Yamada M. 2011. Growth and ethanol fermentation ability on hexose and pentose sugars and glucose effect under various conditions in thermotolerant yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 90:1573–1586. 10.1007/s00253-011-3218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lertwattanasakul N, Rodrussamee N, Suprayogi, Limtong S, Thanonkeo P, Kosaka T, Yamada M. 2011. Utilization capability of sucrose, raffinose and inulin and its less-sensitiveness to glucose repression in thermotolerant yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus DMKU 3-1042. AMB Express 1:20. 10.1186/2191-0855-1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nurcholis M, Lertwattanasakul N, Rodrussamee N, Kosaka T, Murata M, Yamada M. 2020. Integration of comprehensive data and biotechnological tools for industrial applications of Kluyveromyces marxianus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 104:475–488. 10.1007/s00253-019-10224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banat IM, Nigam P, Singh D, Marchant R, McHale AP. 1998. Ethanol production at elevated temperatures and alcohol concentrations. I. Yeasts in general. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 14:809–821. 10.1023/A:1008802704374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murata M, Nitiyon S, Lertwattanasakul N, Sootsuwan K, Kosaka T, Thanonkeo P, Limtong S, Yamada M. 2015. High-temperature fermentation technology for low-cost bioethanol. J Jpn Inst Energy 94:1154–1162. 10.3775/jie.94.1154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nitiyon S, Keo-Oudone C, Murata M, Lertwattanasakul N, Limtong S, Kosaka T, Yamada M. 2016. Efficient conversion of xylose to ethanol by stress-tolerant Kluyveromyces marxianus BUNL-21. Springerplus 5:185. 10.1186/s40064-016-1881-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan Y. 2011. Mitochondria, reactive oxygen species, and chronological aging: a message from yeast. Exp Gerontol 46:847–852. 10.1016/j.exger.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarrío N, García-Leiro A, Cerdán ME, González-Siso MI. 2008. The role of glutathione reductase in the interplay between oxidative stress response and turnover of cytosolic NADPH in Kluyveromyces lactis. FEMS Yeast Res 8:597–606. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2008.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbott DA, Zelle RM, Pronk JT, van Maris AJ. 2009. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of carboxylic acids: current status and challenges. FEMS Yeast Res 9:1123–1136. 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madeo F, Fröhlich E, Ligr M, Grey M, Sigrist SJ, Wolf DH, Fröhlich KU. 1999. Oxygen stress: a regulator of apoptosis in yeast. J Cell Biol 145:757–767. 10.1083/jcb.145.4.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scherz-Shouval R, Elazar Z. 2007. ROS, mitochondria and the regulation of autophagy. Trends Cell Biol 17:422–427. 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank M, Duvezin-Caubet S, Koob S, Occhipinti A, Jagasia R, Petcherski A, Ruonala MO, Priault M, Salin B, Reichert AS. 2012. Mitophagy is triggered by mild oxidative stress in a mitochondrial fission dependent manner. Biochim Biophys Acta 1823:2297–2310. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanki T, Furukawa K, Yamashita S. 2015. Mitophagy in yeast: molecular mechanisms and physiological role. Biochim Biophys Acta 1853:2756–2765. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson JF, Whyte B, Bissinger PH, Schiestl RH. 1996. Oxidative stress is involved in heat-induced cell death in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:5116–5121. 10.1073/pnas.93.10.5116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.López-Mirabal HR, Winther JR. 2008. Redox characteristics of the eukaryotic cytosol. Biochim Biophys Acta 1783:629–640. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruger NJ, von Schaewen A. 2003. The oxidative pentose phosphate pathway: structure and organization. Curr Opin Plant Biol 6:236–246. 10.1016/S1369-5266(03)00039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itsumi M, Inoue S, Elia AJ, Murakami K, Sasaki M, Lind EF, Brenner D, Harris IS, Chio II, Afzal S, Cairns RA, Cescon DW, Elford AR, Ye J, Lang PA, Li WY, Wakeham A, Duncan GS, Haight J, You-Ten A, Snow B, Yamamoto K, Ohashi PS, Mak TW. 2015. Idh1 protects murine hepatocytes from endotoxin induced oxidative stress by regulating the intracellular NADP+/NADPH ratio. Cell Death Differ 22:1837–1845. 10.1038/cdd.2015.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia W, Wang Z, Wang Q, Han J, Zhao C, Hong Y, Zeng L, Tang L, Ying W. 2009. Roles of NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH in cell death. Curr Pharm Des 15:12–19. 10.2174/138161209787185832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaw JM, Nunnari J. 2002. Mitochondrial dynamics and division in budding yeast. Trends Cell Biol 12:178–184. 10.1016/S0962-8924(01)02246-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Youle RJ, van der Bliek AM. 2012. Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress. Science 337:1062–1065. 10.1126/science.1219855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palikaras K, Tavernarakis N. 2014. Mitochondrial homeostasis: the interplay between mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis. Exp Gerontol 56:182–188. 10.1016/j.exger.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotiadis VN, Duchen MR, Osellame LD. 2014. Mitochondrial quality control and communications with the nucleus are important in maintaining function and cell death. Biochim Biophys Acta 1840:1254–1265. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thevelein JM. 1984. Regulation of trehalose mobilization in fungi. Microbiol Rev 48:42–59. 10.1128/mr.48.1.42-59.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woo JM, Yang KM, Kim SU, Blank LM, Park JB. 2014. High temperature stimulates acetic acid accumulation and enhances the growth inhibition and ethanol production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae under fermenting conditions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:6085–6094. 10.1007/s00253-014-5691-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludovico P, Sousa MJ, Silva MT, Leão CL, Côrte-Real M. 2001. Saccharomyces cerevisiae commits to a programmed cell death process in response to acetic acid. Microbiology (Reading) 147:2409–2415. 10.1099/00221287-147-9-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ludovico P, Rodrigues F, Almeida A, Silva MT, Barrientos A, Côrte-Real M. 2002. Cytochrome c release and mitochondria involvement in programmed cell death induced by acetic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 13:2598–2606. 10.1091/mbc.e01-12-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singer MA, Lindquist S. 1998. Thermotolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the Yin and Yang of trehalose. Trends Biotechnol 16:460–468. 10.1016/S0167-7799(98)01251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petitjean M, Teste MA, Léger-Silvestre I, François JM, Parrou JL. 2017. RETRACTED: a new function for the yeast trehalose-6P synthase (Tps1) protein, as key pro-survival factor during growth, chronological ageing, and apoptotic stress. Mech Ageing Dev 161:234–246. 10.1016/j.mad.2016.07.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lertwattanasakul N, Kosaka T, Hosoyama A, Suzuki Y, Rodrussamee N, Matsutani M, Murata M, Fujimoto N, Suprayogi, Tsuchikane K, Limtong S, Fujita N, Yamada M. 2015. Genetic basis of the highly efficient yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus: complete genome sequence and transcriptome analyses. Biotechnol Biofuels 8:47. 10.1186/s13068-015-0227-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang M, Shi J, Jiang L. 2015. Modulation of mitochondrial membrane integrity and ROS formation by high temperature in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Electron J Biotechnol 18:202–209. 10.1016/j.ejbt.2015.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, ten Pierick A, van Rossum HM, Seifar RM, Ras C, Daran JM, Heijnen JJ, Wahl SA. 2015. Determination of the cytosolic NADPH/NADP ratio in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using shikimate dehydrogenase as sensor reaction. Sci Rep 5:12846. 10.1038/srep12846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Natarajan K, Meyer MR, Jackson BM, Slade D, Roberts C, Hinnebusch AG, Marton MJ. 2001. Transcriptional profiling shows that Gcn4p is a master regulator of gene expression during amino acid starvation in yeast. Mol Cell Biol 21:4347–4368. 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4347-4368.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delorme-Axford E, Klionsky DJ. 2018. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of autophagy in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 293:5396–5403. 10.1074/jbc.R117.804641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Axe DD, Bailey JE. 1995. Transport of lactate and acetate through the energized cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng 47:8–19. 10.1002/bit.260470103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russell JB. 1991. Resistance of Streptococcus bovis to acetic acid at low pH: relationship between intracellular pH and anion accumulation. Appl Environ Microbiol 57:255–259. 10.1128/aem.57.1.255-259.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guaragnella N, Passarella S, Marra E, Giannattasio S. 2010. Knock-out of metacaspase and/or cytochrome c results in the activation of a ROS-independent acetic acid-induced programmed cell death pathway in yeast. FEBS Lett 584:3655–3660. 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manfredini V, Roehrs R, Peralba MC, Henriques JA, Saffi J, Ramos AL, Benfato MS. 2004. Glutathione peroxidase induction protects Saccharomyces cerevisiae sod1D sod2D double mutants against oxidative damage. Braz J Med Biol Res 37:159–165. 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wai T, Langer T. 2016. Mitochondrial dynamics and metabolic regulation. Trends Endocrinol Metab 27:105–117. 10.1016/j.tem.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murata M, Fujimoto H, Nishimura K, Charoensuk K, Nagamitsu H, Raina S, Kosaka T, Oshima T, Ogasawara N, Yamada M. 2011. Molecular strategy for survival at a critical high temperature in Escherichai coli. PLoS One 6:e20063. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang B, Ren L, Zeng S, Zhang S, Xu D, Zeng X, Li F. 2020. Functional analysis of PGI1 and ZWF1 in thermotolerant yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 104:7991–8006. 10.1007/s00253-020-10808-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fonseca GG, Heinzle E, Wittmann C, Gombert AK. 2008. The yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus and its biotechnological potential. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 79:339–354. 10.1007/s00253-008-1458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakihama Y, Hidese R, Hasunuma T, Kondo A. 2019. Increased flux in acetyl-CoA synthetic pathway and TCA cycle of Kluyveromyces marxianus under respiratory conditions. Sci Rep 9:5319. 10.1038/s41598-019-41863-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Limtong S, Sringiew C, Yongmanitchai W. 2007. Production of fuel ethanol at high temperature from sugar cane juice by a newly isolated Kluyveromyces marxianus. Bioresour Technol 98:3367–3374. 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sootsuwan K, Lertwattanasakul N, Thanonkeo P, Matsushita K, Yamada M. 2008. Analysis of the respiratory chain in ethanologenic Zymomonas mobilis with a cyanide-resistant bd-type ubiquinol oxidase as the only terminal oxidase and its possible physiological roles. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 14:163–175. 10.1159/000112598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lertwattanasakul N, Shigemoto E, Rodrussamee N, Limtong S, Thanonkeo P, Yamada M. 2009. The crucial role of alcohol dehydrogenase Adh3 in Kluyveromyces marxianus mitochondrial metabolism. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 73:2720–2726. 10.1271/bbb.90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pérez-Gallardo RV, Briones LS, Díaz-Pérez AL, Gutiérrez S, Rodríguez-Zavala JS, Campos-García J. 2013. Reactive oxygen species production induced by ethanol in Saccharomyces cerevisiae increases because of a dysfunctional mitochondrial iron-sulfur cluster assembly system. FEMS Yeast Res 13:804–819. 10.1111/1567-1364.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dulley JR, Grieve PA. 1975. A simple technique for eliminating interference by detergents in the Lowry method of protein determination. Anal Biochem 64:136–141. 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90415-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gajendra KA, Singh V, Mandal P, Singh P, Golla U, Baranwal S, Chauhan S, Tomar RS. 2014. Ebselen induces reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated cytotoxicity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae with inhibition of glutamate dehydrogenase being a target. FEBS Open Bio 4:77–89. 10.1016/j.fob.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nurcholis M, Murata M, Limtong S, Kosaka T, Yamada M. 2019. MIG1 as a positive regulator for the histidine biosynthesis pathway and as a global regulator in thermotolerant yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus. Sci Rep 9:9926. 10.1038/s41598-019-46411-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuby SA, Noltmann EA. 1966. Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (crystalline) from brewers’ yeast. Methods Enzymol 9:116–125. 10.1016/0076-6879(66)09029-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott WA, Abramsky T. 1975. 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase from Neurospora crassa. Methods Enzymol 41:227–231. 10.1016/s0076-6879(75)41052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Noltmann EA. 1966. Phosphoglucose isomerase. Methods Enzymol 9:557–565. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosen OM. 1975. Purification of fructose-1,6-diphosphatase from Polysphondylium palidum. Methods Enzymol 42:360–363. 10.1016/0076-6879(75)42141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amelunxen RE, Carr DO. 1975. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from rabbit muscle. Methods Enzymol 41:264–267. 10.1016/s0076-6879(75)41060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 to S6 and Tables S1 to S14. Download aem.02006-21-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.7 MB (1.7MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All of the data were deposited in the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive (https://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/dra/index-e.html) under accession number DRA010932.