Abstract

A total of 387 clinical strains of erythromycin-resistant (MIC, ≥1 μg/ml) Streptococcus pyogenes, all isolated in Italian laboratories from 1995 to 1998, were examined. By the erythromycin-clindamycin double-disk test, 203 (52.5%) strains were assigned to the recently described M phenotype, 120 (31.0%) were assigned to the inducible macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin B resistance (iMLS) phenotype, and 64 (16.5%) were assigned to the constitutive MLS resistance (cMLS) phenotype. The inducible character of the resistance of the iMLS strains was confirmed by comparing the clindamycin MICs determined under normal testing conditions and those determined after induction by pregrowth in 0.05 μg of erythromycin per ml. The MICs of erythromycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin, josamycin, spiramycin, and the ketolide HMR3004 were then determined and compared. Homogeneous susceptibility patterns were observed for the isolates of the cMLS phenotype (for all but one of the strains, HMR3004 MICs were 0.5 to 8 μg/ml and the MICs of the other drugs were >128 μg/ml) and those of the M phenotype (resistance only to the 14- and 15-membered macrolides was recorded, with MICs of 2 to 32 μg/ml). Conversely, heterogeneous susceptibility patterns were observed in the isolates of the iMLS phenotype, which were subdivided into three distinct subtypes designated iMLS-A, iMLS-B, and iMLS-C. The iMLS-A strains (n = 84) were highly resistant to the 14-, 15-, and 16-membered macrolides and demonstrated reduced susceptibility to low-level resistance to HMR3004. The iMLS-B strains (n = 12) were highly resistant to the 14- and 15-membered macrolides, susceptible to the 16-membered macrolides (but highly resistant to josamycin after induction), and susceptible to HMR3004 (but intermediate or resistant after induction). The iMLS-C strains (n = 24) had lower levels of resistance to the 14- and 15-membered macrolides (with erythromycin MICs increasing two to four times after induction), were susceptible to the 16-membered macrolides (but resistant to josamycin after induction), and remained susceptible to HMR3004, also after induction. The erythromycin resistance genes in 100 isolates of the different groups were investigated by PCR. All cMLS and iMLS-A isolates tested had the ermAM (ermB) gene, whereas all iMLS-B and iMLS-C isolates had the ermTR gene (neither methylase gene was found in isolates of other groups). The M isolates had only the macrolide efflux (mefA) gene, which was also found in variable proportions of cMLS, iMLS-A, iMLS-B, and iMLS-C isolates. The three iMLS subtypes were easily differentiated by a triple-disk test set up by adding a josamycin disk to the erythromycin and clindamycin disks of the conventional double-disk test. Tetracycline resistance was not detected in any isolate of the iMLS-A subtype, whereas it was observed in over 90% of both iMLS-B and iMLS-C isolates.

Target site modifications due to methylase activity, i.e., the most common and most extensively investigated mechanism of erythromycin resistance, usually result in coresistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin B (MLS) antibiotics (12, 23, 24). It has been known for a long time that in gram-positive cocci MLS resistance can be expressed either constitutively (cMLS phenotype) or inducibly (iMLS phenotype) (8, 12, 22). Unlike staphylococci, in which resistance is dissociated between 14- and 15-membered macrolides, which are inducers, and 16-membered macrolides and lincosamides, which are not, in streptococci there is cross-resistance between MLS antibiotics, which are efficient inducers (12). This feature of streptococci may explain previous data about the diversity of the resistance patterns observed by agar diffusion (7) and zonal resistance to lincomycin (6, 13). In Streptococcus pyogenes, MLS resistance can be mediated by two classes of methylase genes, i.e., the conventional ermAM (ermB) determinant (12) and the recently described ermTR determinant (19). By means of an erythromycin-clindamycin double-disk test, a novel macrolide resistance pattern characterized by susceptibility to lincosamides, also after induction, and 16-membered macrolides has been recognized in S. pyogenes isolates (18). This new resistance pattern (M phenotype) has also been observed in Streptococcus pneumoniae and has been shown to be mediated by an efflux system (21). A gene (mefA) that encodes a membrane protein responsible for this efflux-mediated resistance has been characterized (3).

A significant increase in the percentage of erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes strains was reported in Italy in the mid-1990s (2, 5). The present study describes the distribution of recently isolated Italian strains of S. pyogenes into the recognized phenotypes and focuses on the phenotypic heterogeneity of inducibly resistant strains, which were subdivided into three distinct subtypes. Erythromycin resistance genes ermB, ermTR, and mefA were investigated by PCR in several isolates of the different groups. A triple-disk assay (erythromycin and clindamycin plus josamycin) which easily differentiates, in addition to the known major phenotypes, the different subtypes within the iMLS phenotype is also described.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 387 clinical isolates of erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes (the vast majority of which were from cultures of throat swabs from children) were collected from several Italian laboratories between October 1995 and June 1998. Multiple isolates from the same patient were avoided. Strain identification was confirmed in our laboratory with bacitracin disks (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and by a latex agglutination assay (Streptex; Wellcome, Dartford, United Kingdom), and erythromycin resistance (MIC, ≥1 μg/ml) was confirmed by the broth microdilution method (see below). The strains were maintained in glycerol at −70°C until all isolates were collected and were subcultured twice on blood agar before susceptibility testing.

Erythromycin-clindamycin double-disk test.

The erythromycin-clindamycin double-disk test was carried out by a modification of the assay described by Seppälä et al. (18). Commercial disks (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) of erythromycin (30 μg) and clindamycin (10 μg) were used. Preliminary tests indicated that the results obtained with these disks were fully comparable to those obtained by Seppälä et al. (18) with disks with larger amounts of drug. The disks were placed 15 to 20 mm apart on Mueller-Hinton II agar (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) supplemented with 5% sheep blood, which had been inoculated with a swab dipped into a bacterial suspension with a turbidity equivalent to that of a 0.5 McFarland standard. After 18 h of incubation at 37°C, the absence of a significant zone of inhibition around the two disks was taken to indicate constitutive resistance (cMLS phenotype), blunting of the clindamycin zone of inhibition proximal to the erythromycin disk was taken to indicate inducible resistance (iMLS phenotype), and susceptibility to clindamycin with no blunting of the zone of inhibition around the clindamycin disk was taken to indicate the M phenotype.

Antibiotics.

Erythromycin and clindamycin were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). The other antibiotics were obtained as follows: clarithromycin, Abbott Laboratories (Abbott Park, Ill.); azithromycin, Pfizer Inc. (New York, N.Y.); josamycin, ICN Biomedicals (Costa Mesa, Calif.); spiramycin, Rhône-Poulenc Rorer (Paris, France); and HMR3004, Hoechst Marion Roussel (Romainville, France).

Susceptibility tests.

MICs were determined by the broth microdilution method (15) with Mueller-Hinton II broth (BBL Microbiology Systems) supplemented with 3% lysed horse blood as the test medium. The inoculum was 5 × 105 CFU/ml. The antibiotics were tested at final concentrations (prepared from twofold dilutions) that ranged from 0.015 to 128 μg/ml. S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 was used for quality control. The MIC breakpoints suggested by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (17) were considered for erythromycin, clindamycin, and clarithromycin (susceptible, ≤0.25 μg/ml; intermediate, 0.5 μg/ml; resistant, ≥1 μg/ml) and for azythromycin (susceptible, ≤0.5 μg/ml; intermediate, 1 μg/ml; resistant, ≥2 μg/ml). The MIC breakpoints suggested by the French Society for Microbiology (4) were considered for spiramycin and josamycin (susceptible, ≤1 μg/ml; intermediate, 2 μg/ml; resistant, ≥4 μg/ml). In the absence of established interpretive standards, the MIC breakpoints unofficially proposed for HMR3647, another ketolide (susceptible, ≤1 μg/ml; intermediate, 2 μg/ml; resistant, ≥4 μg/ml) (1), were tentatively applied to HMR3004, too.

Tetracycline and chloramphenicol susceptibilities were determined by a standard agar diffusion test (16) with commercial disks (Oxoid) containing 30 μg of either antibiotic. The zone diameter breakpoints (17) were as follows: for tetracycline, susceptible, ≥23 mm; intermediate, 19 to 22 mm; and resistant, ≤18 mm; for chloramphenicol, susceptible, ≥21 mm; intermediate, 18 to 20 mm; and resistant, ≤17 mm.

Induction of MLS resistance.

Induction of MLS resistance was evaluated by pregrowth (3 h at 37°C) in erythromycin at a subinhibitory concentration (0.05 μg/ml), as described previously (13). The culture was then washed and the cells were used to prepare the inoculum for MIC testing by the usual broth microdilution method.

Detection of erythromycin resistance genes.

The ermB gene was detected by PCR with the oligonucleotide primer pair reported by Sutcliffe et al. (20) (the expected PCR product was 639 bp). The ermTR gene was detected with the primers designated III8 and III10 by Seppälä et al. (19) (the expected PCR product was 208 bp). The mefA gene was detected with the primer pair reported by Sutcliffe et al. (20) (the expected PCR product was 348 bp). DNA preparation and amplification and electrophoresis of PCR products were carried out by established procedures (9, 19, 20).

RESULTS

Identification of macrolide resistance phenotypes.

On the basis of the erythromycin-clindamycin double-disk test, 203 (52.5%) of the 387 strains of erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes tested were assigned to the M phenotype, 120 (31.0%) were assigned to the iMLS phenotype, and 64 (16.5%) were assigned to the cMLS phenotype (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Determination of the macrolide resistance phenotype in 387 throat isolates of erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes by the double-disk test and correlation with clindamycin susceptibility

| Phenotype of macrolide resistance | No. (%) of strains | Susceptibility to clindamycin (MIC [μg/ml])

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Without induction | After induction | ||

| cMLS | 64 (16.5) | All highly resistant (>128) | All highly resistant (>128) |

| iMLS | 120 (31.0) | Susceptible (≤0.015 to 0.25) (n = 117); intermediate (0.5) (n = 3) | All highly resistant (>128) |

| M | 203 (52.5) | All susceptible (≤0.015 to 0.12) | All susceptible (≤0.015 to 0.12) |

The inducible character of the resistance of the strains assigned to the iMLS phenotype by the double-disk test was confirmed by comparing the clindamycin MICs determined under normal testing conditions and those determined after induction by pregrowth in 0.05 μg of erythromycin per ml. Without induction, clindamycin MICs were in the range of susceptibility for all except three iMLS isolates, for which the MICs (0.5 μg/ml) were consistent with intermediate susceptibility; after induction, the clindamycin MICs for the iMLS isolates invariably exceeded 128 μg/ml. By the same method, all the isolates previously assigned to the cMLS phenotype were found to be highly resistant to clindamycin (MICs, >128 μg/ml) without induction, whereas those assigned to the M phenotype remained susceptible even after induction (Table 1).

Patterns of susceptibility to MLS antibiotics.

The MICs of two 14-membered (erythromycin and clarithromycin), one 15-membered (azythromycin), and two 16-membered (josamycin and spiramycin) macrolides and of the ketolide HMR3004 were determined and compared.

Homogeneous susceptibility patterns were observed among the isolates of the cMLS phenotype (with one exception) and those of the M phenotype, whereas among the isolates of the iMLS phenotype patterns were heterogeneous (Table 2). For 63 of the 64 cMLS strains, the MICs of HMR3004 ranged from 0.5 to 8 μg/ml, while those of the other drugs tested exceeded 128 μg/ml. The remaining cMLS strain was highly susceptible to HMR3004 (MIC, ≤0.015 μg/ml) and was resistant to the macrolides (MIC range, 2 to 32 μg/ml). For the M-phenotype isolates, resistances were recorded only to the 14- and 15-membered macrolides (MIC range, 2 to 32 μg/ml). For the isolates of the iMLS phenotype, the susceptibilities of the 16-membered macrolides ranged from susceptibility to high-level resistance values, those of HMR3004 ranged from susceptibility to resistance, and those of the 14- and 15-membered macrolides ranged from low-level resistance (or intermediate susceptibility to clarithromycin in three isolates) to high-level resistance.

TABLE 2.

Susceptibilities of 387 isolates of erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes, subdivided into the three recognized phenotypes of macrolide resistance, to MLS antibiotics

| Phenotype of macrolide resistance (no. of strains) | Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | ||

| cMLS (64) | Erythromycin | 2–>128 | >128 | >128 |

| Clarithromycin | 4–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Azithromycin | 8–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Josamycin | 16–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Spiramycin | 32–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| HMR3004 | ≤0.015–8 | 1 | 4 | |

| Clindamycin | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| iMLS (120) | Erythromycin | 1–>128 | >128 | >128 |

| Clarithromycin | 0.5–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Azithromycin | 4–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Josamycin | 0.03–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Spiramycin | 0.12–>128 | >128 | >128 | |

| HMR3004 | ≤0.015–8 | 0.5 | 4 | |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.015–0.5 | 0.12 | 0.25 | |

| M (203) | Erythromycin | 2–32 | 8 | 16 |

| Clarithromycin | 2–16 | 8 | 8 | |

| Azithromycin | 2–32 | 4 | 8 | |

| Josamycin | ≤0.015–0.12 | 0.03 | 0.12 | |

| Spiramycin | 0.25–1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| HMR3004 | ≤0.015–0.25 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.015–0.12 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |

50% and 90%, MICs at which 50 and 90% of isolates are inhibited, respectively.

With the inducibly resistant strains, the MICs of erythromycin, josamycin, and HMR3004 were also determined after induction with erythromycin, by the same pregrowth procedure used previously for clindamycin susceptibility tests. Three distinct patterns of resistance to MLS antibiotics were recognized among these isolates (Table 3). The most frequently observed pattern, observed for 84 (70%) inducibly resistant strains and designated iMLS-A, was characterized by high-level resistance to the 14-, 15-, and 16-membered macrolides (MICs, >128 μg/ml) and reduced susceptibility to low-level resistance to HMR3004 (MICs, 0.5 to 8 μg/ml without induction and 1 to 16 μg/ml after induction). The second pattern, observed for 12 (10%) inducibly resistant strains and designated iMLS-B, was characterized by high-level resistance to the 14- and 15-membered macrolides (MICs, >128 μg/ml), susceptibility to the 16-membered macrolides but high-level resistance to josamycin (MICs, >128 μg/ml) after induction, and susceptibility to HMR3004 without induction but intermediate susceptibility or resistance (MICs, 2 to 8 μg/ml) after induction. The third pattern, observed for the remaining 24 (20%) inducibly resistant strains and designated iMLS-C, was characterized by resistance to the 14- and 15-membered macrolides (with MICs not exceeding 16 μg/ml and erythromycin MICs increasing two to four times after induction), susceptibility to the 16-membered macrolides but resistance to josamycin after induction (MICs, 4 to 16 μg/ml), and susceptibility to HMR3004, also after induction.

TABLE 3.

Susceptibilities of 120 isolates of S. pyogenes with the iMLS phenotype to MLS antibiotics and their subdivision into three subtypes

| Subtype of iMLS resistance (no. of strains) | Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | ||

| iMLS-A (84) | Erythromycin | All >128 | >128 | >128 |

| Erythromycin (ind.)b | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Clarithromycin | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Azithromycin | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Josamycin | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Josamycin (ind.) | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Spiramycin | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| HMR3004 | 0.5–8 | 1 | 4 | |

| HMR3004 (ind.) | 1–16 | 2 | 8 | |

| Clindamycin | 0.03–0.5 | 0.12 | 0.25 | |

| Clindamycin (ind.) | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| iMLS-B (12) | Erythromycin | All >128 | >128 | >128 |

| Erythromycin (ind.) | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Clarithromycin | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Azithromycin | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Josamycin | 0.03–0.12 | 0.03 | 0.12 | |

| Josamycin (ind.) | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| Spiramycin | 0.25–0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| HMR3004 | All ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | |

| HMR3004 (ind.) | 2–8 | 2 | 8 | |

| Clindamycin | 0.03–0.5 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |

| Clindamycin (ind.) | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

| iMLS-C (24) | Erythromycin | 1–8 | 2 | 4 |

| Erythromycin (ind.) | 4–16 | 8 | 8 | |

| Clarithromycin | 0.5–16 | 1 | 2 | |

| Azithromycin | 4–16 | 8 | 16 | |

| Josamycin | 0.03–0.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| Josamycin (ind.) | 4–16 | 8 | 16 | |

| Spiramycin | 0.12–1 | 0.25 | 1 | |

| HMR3004 | All ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | ≤0.015 | |

| HMR3004 (ind.) | 0.03–0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.015–0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | |

| Clindamycin (ind.) | All >128 | >128 | >128 | |

See footnote a of Table 2.

ind., after induction by pregrowth in 0.05 μg of erythromycin per ml.

Erythromycin resistance genes.

The presence of the erythromycin resistance genes ermB, ermTR, and mefA in 100 isolates (20 cMLS, 42 iMLS-A, 6 iMLS-B, 12 iMLS-C, and 20 M) was investigated by PCR (Table 4). All cMLS and iMLS-A isolates tested had the ermB gene, whereas all iMLS-B and iMLS-C isolates had the ermTR gene (neither methylase determinant was found in isolates of the other groups). All M-phenotype isolates had the mefA gene, which was also found in several isolates of the cMLS (40%) and iMLS (31% iMLS-A, 100% iMLS-B, and 92% iMLS-C) phenotypes.

TABLE 4.

Distribution of erythromycin resistance genes ermB, ermTR, and mefA among 100 erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes isolates of different phenotypes and subtypes of macrolide resistance

| Phenotype and iMLS subtype of macrolide resistance | No. of strains tested | No. of strains with the following gene:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ermB | ermTR | mefA | ||

| cMLS | 20 | 20 | 8 | |

| iMLS | 60 | 42 | 18 | 30 |

| iMLS-A | 42 | 42 | 13 | |

| iMLS-B | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| iMLS-C | 12 | 12 | 11 | |

| M | 20 | 20 | ||

Susceptibility to tetracycline and chloramphenicol.

The susceptibilities to two non-MLS antibiotics (tetracycline and chloramphenicol) were determined by agar diffusion. Chloramphenicol resistance was not encountered in any of the erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes test strains. Tetracycline resistance (Table 5) was detected in the majority of isolates of the cMLS (71.9%) and M (69.5%) phenotypes. An overall incidence of tetracycline resistance of 27.5% recorded in the iMLS isolates resulted, in fact, from the uniform susceptibility observed among the iMLS-A strains and the greater than 90% incidence of resistance observed among both iMLS-B and iMLS-C strains.

TABLE 5.

Susceptibilities of 387 isolates of erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes, subdivided into phenotypes and iMLS subtypes of macrolide resistance, to tetracycline

| Phenotype and iMLS subtype of macrolide resistance (no. of strains) | No. (%) of strains with indicated susceptibilitya to tetracycline:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| S | I | R | |

| cMLS (64) | 12 (18.7) | 6 (9.4) | 46 (71.9) |

| iMLS (120) | 86 (71.7) | 1 (0.8) | 33 (27.5) |

| iMLS-A (84) | 84 (100) | ||

| iMLS-B (12) | 1 (8.3) | 11 (91.7) | |

| iMLS-C (24) | 2 (8.3) | 22 (91.7) | |

| M (203) | 54 (26.6) | 8 (3.9) | 141 (69.5) |

S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

Triple-disk test.

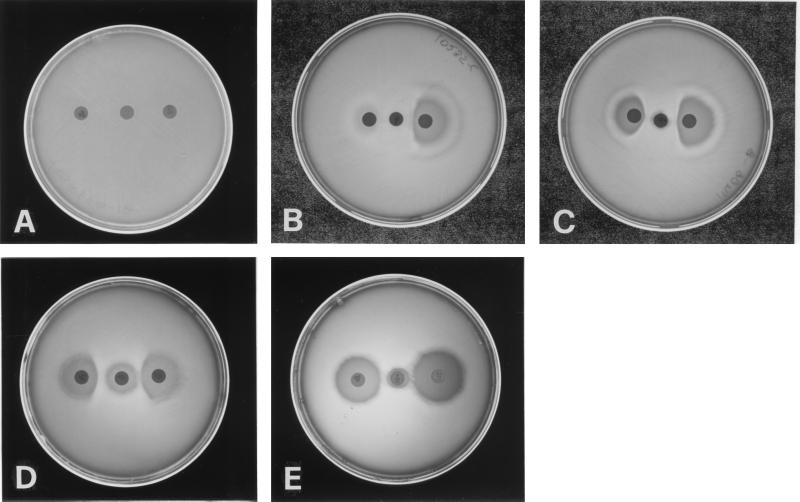

Considering the crucial importance of the 16-membered macrolides in discriminating the three subtypes of inducibly resistant S. pyogenes strains, a triple-disk test was set up by adding a josamycin disk (30 μg; Oxoid) to the erythromycin and clindamycin disks of the conventional double-disk test. The erythromycin disk was placed at the center of the agar plate, with the clindamycin and josamycin disks placed 15 to 20 mm apart on either side. All strains were tested by this triple-disk assay.

While the clindamycin zone of inhibition proximal to the erythromycin disk was uniformly blunted among the iMLS strains, in agreement with the inducible nature of the resistance in these strains, blunting of the josamycin zone of inhibition proximal to the erythromycin disk was taken to indicate inducible resistance to the 16-membered macrolides. As shown in Fig. 1, the iMLS-A strains were characterized by the absence of any zone of inhibition around both the erythromycin and the josamycin disks (in line with their high-level resistance to both drugs). The iMLS-B and iMLS-C strains were both characterized by blunting of the josamycin zone of inhibition proximal to the erythromycin disk. However, no zone of inhibition was seen around the erythromycin disk in the case of the iMLS-B strains (in agreement with their high-level erythromycin resistance), whereas a restricted zone of inhibition (not exceeding 15 mm in diameter) was visible in the case of the iMLS-C strains (in line with their lower-level erythromycin resistance).

FIG. 1.

Phenotypes and iMLS subtypes of erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes isolates determined by the triple-disk test. The erythromycin disk (30 μg) is at the center, with the clindamycin disk (10 μg) on the right and the josamycin disk (30 μg) on the left. (A) cMLS phenotype. (B) iMLS phenotype (subtype iMLS-A). (C) iMLS phenotype (subtype iMLS-B). (D) iMLS phenotype (subtype iMLS-C). (E) M phenotype.

S. pyogenes strains of both the cMLS phenotype (characterized by the absence of a zone of inhibition around the clindamycin disk) and the M phenotype (characterized by no blunting of the clindamycin zone of inhibition) were identified by the triple-disk test as easily as by the double-disk test.

The performance of the triple-disk test did not substantially change when a spiramycin disk (100 μg; Oxoid) was used instead of the josamycin disk.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate that, among the erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes strains which have increasingly arisen in Italy over the last few years (2, 5), the M phenotype is encountered for over one-half (52.5%) of the strains and the iMLS phenotype is encountered for almost one-third (31.0%) of the strains, while the cMLS phenotype is encountered less frequently (16.5%). Interestingly, the iMLS strains, although easily and sharply distinguishable from isolates of the cMLS and M phenotypes on the basis of the inducible character of their resistance, were found to be homogeneous in their response to clindamycin (with all strains turning from susceptible or, occasionally, intermediate without induction to highly resistant after induction) but heterogeneous in their susceptibility to the macrolides and the ketolide. On the basis of this phenotypic heterogeneity, three distinct subtypes of inducibly resistant strains (designated iMLS-A, iMLS-B, and iMLS-C) were distinguished. Susceptibility to the 16-membered macrolides was of particular importance in discriminating the three subtypes: the iMLS-A strains were highly resistant to josamycin, and this was also the case without induction; and the iMLS-B and iMLS-C strains were josamycin susceptible but became high-level and low-level resistant, respectively, after induction. A triple-disk test, which was set up by adding a josamycin disk to the erythromycin and clindamycin disks of the conventional double-disk test, enabled us to distinguish easily not only the three known phenotypes of erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes (cMLS, iMLS, and M) but also the three iMLS subtypes (iMLS-A, iMLS-B, and iMLS-C). As for the non-MLS antibiotics, the acquisition of resistance to tetracycline and/or chloramphenicol has been considered a prerequisite for S. pyogenes resistance to macrolides (14). While chloramphenicol resistance was not detected in our test strains—as among Finnish isolates collected in 1990 (18), whereas resistance was reported in 3% of the iMLS isolates collected in Finland in 1994 and 1995 (11)—variable rates of tetracycline resistance were associated with the different phenotypes of macrolide resistance. In particular, among the iMLS strains, tetracycline resistance was not observed in the isolates of the predominant subtype iMLS-A, whereas it was recorded in over 90% of both iMLS-B and iMLS-C isolates.

Some particular or atypical resistance patterns have been reported previously in macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes strains (10, 18); however, correspondence with our findings appears to be only partial. In our study the sole cMLS isolate that was highly susceptible to HMR3004 and that had low-level resistance to the macrolides is likely to correspond to a subtype of the cMLS phenotype previously described by Seppälä et al. (18), which accounted for over half of the cMLS strains among Finnish isolates. Other atypical subtypes of cMLS strains, characterized by susceptibility or low-level resistance to clindamycin, described among Swedish isolates (10) were not encountered in our experience. The subtypes of the iMLS strains characterized by high-level resistance to erythromycin and inducible resistance to clindamycin described by Seppälä et al. (18) and Jasir and Schalén (10) probably correspond to our iMLS-A or iMLS-B strains, depending on their susceptibilities to 16-membered macrolides. On the other hand, the prevalence of the recognized phenotypes of erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes may also vary from area to area and over time. Indeed, although the M phenotype was the most frequent in our study as well as among erythromycin-resistant S. pyogenes isolates collected in 1994 and 1995 in the United States, Ireland, and Sweden (21) and from 1980 to 1990 in Sweden (10), its frequency was second to that of the iMLS phenotype among the Finnish isolates collected in 1990 (18). Even more strikingly, in Sweden inducibly resistant strains were absent from 1980 to 1990, and constitutively resistant strains were absent from 1980 to 1985 (10).

It seems that the whole matter of phenotypic diversity in macrolide-resistant S. pyogenes strains is still far from being settled and that its comprehension must pass through a careful correlation of phenotypic and genotypic characteristics. However, the knowledge of erythromycin resistance determinants in S. pyogenes also seems far from complete to date. Only recently have a gene (mefA) encoding a membrane protein responsible for efflux-mediated resistance (3) and a methylase gene (ermTR) other than ermAM (ermB) (19) been characterized. Among our strains, ermB was invariably detected in cMLS and iMLS-A isolates, and the same was true of ermTR for iMLS-B and iMLS-C isolates and of mefA for M isolates. However, while the two methylase determinants were not found in isolates of different groups, mefA was also present in less than half of cMLS and iMLS-A isolates and in all or the vast majority of iMLS-B and iMLS-C isolates. It is worth noting that, in a recent survey of erythromycin resistance genes among Finnish isolates of S. pyogenes, Kataja et al. (11) detected only ermTR in 24 iMLS isolates. Most of the Finnish iMLS isolates might, however, fall in our iMLS-B and iMLS-C subtypes (which possess ermTR), as suggested by the reported 93% incidence of tetracycline resistance in these strains (11) (all of our iMLS-A isolates, which all possess ermB, are susceptible to tetracycline). On the other hand, the mefA determinant, which has been found in all or the vast majority of our iMLS-B and iMLS-C isolates, was not detected among the Finnish isolates of iMLS S. pyogenes tested (11).

REFERENCES

- 1.Barry A L, Fuchs P C, Brown S D. Program and abstracts of the 4th International Conference on the Macrolides, Azalides, Streptogramins and Ketolides. 1998. Tentative interpretive criteria for HMR 3647 disk diffusion tests, abstr. 1.01; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borzani M, De Luca M, Varotto F. A survey of susceptibility to erythromycin amongst Streptococcus pyogenes isolates in Italy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:457–458. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clancy J, Petitpas J, Dib-Hajj F, Yuan W, Cronan M, Kamath A V, Bergeron J, Retsema J A. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of a novel macrolide resistance determinant, mefA, from Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:867–879. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comité de l’Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie. Statement 1996 CA-SFM. Zone sizes and MIC breakpoints for non-fastidious organisms. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996;2(Suppl. 1):46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornaglia G, Ligozzi M, Mazzariol A, Valentini M, Orefici G, Fontana R the Italian Surveillance Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. Rapid increase of resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin in Streptococcus pyogenes in Italy, 1993–1995. Emerg Infect Dis. 1996;2:339–342. doi: 10.3201/eid0204.960410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon J M S, Lipinski A E. Infections with β-hemolytic Streptococcus resistant to lincomycin and erythromycin and observations on zonal-pattern resistance to lincomycin. J Infect Dis. 1974;130:351–356. doi: 10.1093/infdis/130.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horodniceanu T, Bougueleret L, Delbos F. Phenotypic aspects of resistance to macrolide and related antibiotics in β-haemolytic group A, B, C, and G streptococci. In: Facklam R, Laurell G, Lind I, editors. Recent developments in laboratory identification techniques. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Excerpta Medica; 1979. pp. 122–131. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyder S L, Streitfeld M M. Inducible and constitutive resistance to macrolide antibiotics and lincomycin in clinically isolated strains of Streptococcus pyogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1973;4:327–331. doi: 10.1128/aac.4.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hynes W L, Ferretti J J, Gilmore M S, Segarra R A. PCR amplification of streptococcal DNA using crude cell lysates. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;94:139–142. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90597-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jasir A, Schalén C. Survey of macrolide resistance phenotypes in Swedish clinical isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:135–137. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kataja J, Huovinen P, Skurnik M, Seppälä H the Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. Erythromycin resistance genes in group A streptococci in Finland. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:48–52. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leclercq R, Courvalin P. Bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics by target modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1267–1272. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.7.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malke H. Zonal-pattern resistance to lincomycin in Streptococcus pyogenes: genetic and physical studies. In: Schlessinger D, editor. Microbiology—1982. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1978. pp. 142–145. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyamoto Y, Takizawa K, Matsushima A, Asai Y, Nakatsuka S. Stepwise acquisition of multiple drug resistance by beta-hemolytic streptococci and difference in resistance pattern by type. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978;13:399–404. doi: 10.1128/aac.13.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed. Approved standard M7-A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, 6th ed. Approved standard M2-A6. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Eighth informational supplement M100-S8. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seppälä H, Nissinen A, Yu Q, Huovinen P. Three different phenotypes of erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes in Finland. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;32:885–891. doi: 10.1093/jac/32.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seppälä H, Skurnik M, Soini H, Roberts M C, Huovinen P. A novel erythromycin resistance methylase gene (ermTR) in Streptococcus pyogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:257–262. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutcliffe J, Grebe T, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sutcliffe J, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes resistant to macrolides but sensitive to clindamycin: a common resistance pattern mediated by an efflux system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1817–1824. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weisblum B. Inducible resistance to macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramin type B antibiotics: the resistance phenotype, its biological diversity, and structural elements that regulate expression—a review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985;16(Suppl. A):63–90. doi: 10.1093/jac/16.suppl_a.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weisblum B. Erythromycin resistance by ribosome modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:577–585. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weisblum B. Insights into erythromycin action from studies of its activity as inducer of resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:797–805. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.4.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]