Abstract

Purpose:

Understanding the motivations and concerns of patients from diverse populations regarding participation in implementation research provides needed evidence about how to design and conduct studies to facilitate access to genetics services. Within a hereditary cancer screening study assessing a multi-faceted intervention, we examined primary care patients’ motivations and concerns about participation.

Methods:

We surveyed and interviewed study participants after they enrolled, surveyed those who did not complete enrollment, and used descriptive qualitative and quantitative methods to identify motivations and concerns regarding participation

Results:

Survey respondents’ most common motivations included a desire to learn about their future risk (81%), information that may help family (58%), and a desire to advance research (34%). Interviews revealed three additional important factors: affordability of testing, convenience of participation, and clinical relationships supporting research decision-making. Survey data for those who declined enrollment showed reasons for declining including concerns about privacy (38%), burdens of research (19%), and their ability to cope with the genetic information (19%).

Conclusion:

Understanding the facilitating factors and concerns that contribute to decisions about research may reveal ways to improve equity in access to care and research that could lead to greater uptake of genomic medicine across diverse primary care patient populations.

Keywords: motivations, concerns, decliners, genetics, primary care, cancer, risk assessment

INTRODUCTION

As clinical genomics implementation research continues to integrate screening and genetic testing into clinical practice, the inclusion of patients from diverse backgrounds and care settings is critical to ensuring that research findings are translated equitably into clinical care. Equitable testing and follow-up care of genetic diseases such as hereditary cancer syndromes will rely on knowledge gained from implementation research in settings that provide care for patient populations traditionally underrepresented in research, such as low income, low literacy, and marginalized populations. With proposals to implement genomic screening and testing programs in healthy adult populations1, it is particularly important that traditionally underrepresented populations have a voice in how these programs are incorporated into their care. Understanding what motivates individuals to join implementation studies and what concerns them about participating is an important step toward ensuring studies are designed in a way that facilitates access to participation, and thereby access to services, across diverse populations and care settings.

Efforts to increase inclusion in genomics research are important for increasing access, reducing disparities, and increasing uptake of genomic services2. To do so, researchers should aim to recruit participants from a variety of care settings, including primary care. Primary care patients often include those for whom potential genetic disease is unknown because they are asymptomatic. Reaching out to patients in the primary care setting is particularly important in the context of screening for hereditary cancer as that is where family history screening is likely to first take place.

Prior research has consistently found that participants are interested in translational genomics research based on a desire to learn more about the genetic risks to their health and an altruistic desire to contribute to research3–6. These findings have been replicated in recent studies with participants from specific populations that are underrepresented in genomics research, including racial and ethnic minority groups, people who are LGBTQ+, and people who were adopted as children7–9. Studies examining concerns about testing have found that, in general, participants worry about the adverse psychological impact of results (especially around untreatable disorders), the reproductive implications of the results, and the privacy of their information10,11. These concerns, as well as issues related to time commitment and study logistics, have also been identified in the literature as barriers to participation for individuals who decline to participate in clinical genomic sequencing implementation studies12,13.

In this analysis, we sought to expand on this prior work to understand what motivations and concerns are salient for patient-participants in the context of genomic services research that is integrated into primary care settings where the services are accessible to a more diverse patient population. Using a mixed-methods approach, we examined the motivations and concerns of primary care patients in a clinical genomics implementation study to assess why some patients decided to join the study, what concerns they had about the study, and why some patients declined participation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overview

We surveyed and interviewed participants in a clinical genomics implementation study, Cancer Health Assessments Reaching Many (CHARM), about their reasons for and concerns about participating. Additionally, we surveyed individuals who declined to participate in the study to learn why they decided not to join. Study recruitment took place between August 2018 and March 2020, with all sequencing and result disclosure completed by August 2020.

Setting

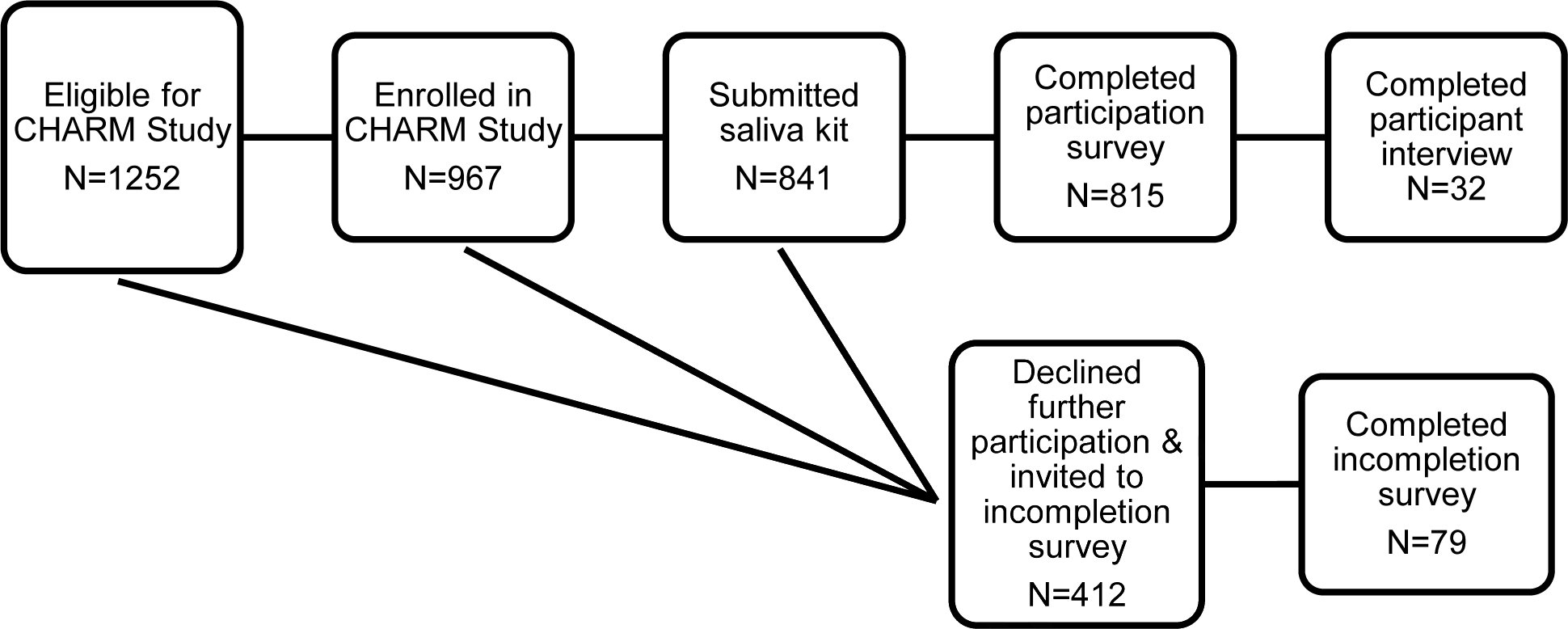

The CHARM study is part of the Clinical Sequencing Evidence-generating Research (CSER) consortium funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Cancer Institute, and National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The goal of CHARM is to study ways to increase access to evidence-based genetic testing for hereditary cancer in low income, low literacy, and marginalized populations by evaluating key laboratory, clinical, behavioral interventions and modifications in a diverse primary care setting. CHARM offered clinical exome sequencing for hereditary cancer syndromes and optional additional findings to primary care patients at Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW) and Denver Health (DH) who use either English or Spanish and were age18–50 years at the time of consent. Participants completed an electronic patient-facing family history assessment for Lynch syndrome and Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer syndrome. Those at increased risk for these syndromes, or who had insufficient family history information to make a risk determination, were invited to participate in the study. Study procedures involved participants submitting a saliva kit, receiving results by phone or letter from a study genetic counselor, having their health record reviewed, completing surveys, and, for a subset of participants, being invited to complete one or more qualitative interviews. For more information about the CHARM study design see Mittendorf et al. (2021)14. Figure 1 illustrates the study flow including when individuals were surveyed and interviewed.

Figure 1.

CHARM Participation Study Flow diagram

CHARM Participation Survey

Immediately after consenting for the genetic testing portion of the study, participants completed an online survey that assessed demographics and perspectives on health care, genetics, and study participation (subsequently referred to as “participation survey”). This manuscript reports on two open-ended and two closed-ended questions, which asked respondents to describe in their own words then select up to three reasons for and three concerns about joining the study (Appendix 1). Response options were developed based on prior literature on motivations and concerns for genetics research participation. Survey data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at KPNW15,16. Respondents were offered $30 as an incentive for completing the survey and returning their saliva sample.

Incompletion Survey

Individuals who were eligible to receive genetic testing through the CHARM study but declined (actively or passively) prior to consenting or who consented but did not send in a saliva sample were asked to complete a survey (subsequently referred to as “incompletion survey”) that asked them to describe in their own words then select up to three reasons (from a list of options based on prior literature) why they decided not to join (Appendix 1). Initially respondents were not incentivized for completing the survey, but a $10 incentive was added shortly after the study started to increase response rate.

Interviews with Participants

We invited a subset of CHARM participants to complete a 30-minute semi-structured phone interview after they joined the study and provided a saliva sample but before they received genetic testing results. We used a purposive sampling approach which involved recruiting roughly an equal number of participants from each study site with a focus on engaging participants from diverse socioeconomic and educational backgrounds, and oversampling participants whose stated preferred language for communication is Spanish. We reviewed available demographics of potential participants as they become eligible to participate in the interviews to ensure we captured a broad range of perspectives and experiences. Interview sampling and recruitment are described in further detail elsewhere17. Interviewees were offered $20 as an incentive for participating. Interview questions addressed why and how participants decided to participate and their reflections on the CHARM consent process (Appendix 1). Interviews were audio recorded, professionally transcribed, translated into English (for interviews conducted in Spanish) by a certified translator, de-identified, and uploaded to the cloud-based qualitative analysis platform Dedoose (dedoose.com) for data management.

Analysis

Closed-ended questions in both surveys were summarized using descriptive statistics. Open-ended responses from both surveys were categorized by two authors (DD (English), AR (Spanish)), independently reviewed by a second author (SK or KP), and discrepancies discussed until consensus was reached. Some open-ended responses were omitted from analysis due to ambiguity in the respondent’s answer.

To analyze the interview data, we developed a qualitative codebook by incorporating the topic areas of the interview guide along with inductive codes from initial transcript review and discussion among the qualitative analysis team. After test coding and incorporating modifications until coders consistently reached consensus, we systematically coded all transcripts. Each transcript was coded by two of three coders (DD, KS, and KP) and unresolved discrepancies were reviewed by the third coder. After all data were coded, the qualitative analysis team summarized excerpts coded in categories of motivations and concerns about research participation and discussed the findings as a group to iteratively identify key findings.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

The CHARM study enrolled 967 participants, of whom 815 (84%) completed the participation survey. Additionally, 79 (19%) of the 412 eligible individuals completed the incompletion survey. We also invited 58 CHARM participants to be interviewed and completed interviews with 32 participants (55% response rate). Demographic information is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Interviewees | Participation Survey Respondents | Incompletion Survey Respondents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=32 | (%) | N=815 | (%) | N=79 | (%) | |

| Recruitment site | ||||||

| Denver Health | 17 | (53) | 261 | (32) | 3 | (4) |

| Kaiser Permanente Northwest | 15 | (47) | 554 | (68) | 76 | (96) |

| Preferred language | ||||||

| English | 20 | (62) | 696 | (85) | 73 | (92) |

| Spanish | 12 | (38) | 119 | (15) | 6 | (8) |

| Mean age (range) | 34 (22–48) | 36 (18–50) | 36 (19–49) | |||

| Sex assigned at birth | ||||||

| Female | 27 | (84) | 644 | (79) | 60 | (76) |

| Male | 5 | (16) | 171 | (21) | 19 | (24) |

| Gender identity | ||||||

| Female | 26 | (81) | 580 | (71) | 53 | (67) |

| Male | 3 | (9) | 154 | (19) | 17 | (22) |

| Non-binary/Genderqueer | 1 | (3) | 14 | (2) | 1 | (1) |

| Transgender female | 0 | (0) | 1 | (0) | 0 | (0) |

| Transgender male | 0 | (0) | 5 | (1) | 1 | (1) |

| Unknowna | 2 | (6) | 61 | (7) | 7 | (9) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Asian | 2 | (6) | 36 | (4) | 6 | (8) |

| Black | 4 | (13) | 36 | (4) | 5 | (6) |

| Hispanic | 15 | (47) | 217 | (27) | 23 | (29) |

| Middle Eastern | 0 | (0) | 6 | (1) | 1 | (1) |

| Native American | 0 | (0) | 13 | (2) | 0 | (0) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 | (0) | 2 | (0) | 0 | (0) |

| White | 9 | (28) | 341 | (42) | 24 | (30) |

| Selected > 1 category | 2 | (6) | 92 | (11) | 8 | (10) |

| Unknowna | 0 | (0) | 72 | (9) | 12 | (15) |

| Highest level of education | ||||||

| Some high school or less | 5 | (16) | 97 | (12) | 2 | (3) |

| High school or associate college degree | 13 | (41) | 352 | (43) | 34 | (43) |

| Bachelors or graduate degree | 12 | (37) | 313 | (38) | 38 | (48) |

| Unknowna | 2 | (6) | 53 | (7) | 5 | (6) |

| Annual household income | ||||||

| <$39,999 | 14 | (44) | 296 | (36) | 21 | (27) |

| $40,000–79,999 | 11 | (34) | 266 | (33) | 23 | (29) |

| >$80,000 | 4 | (13) | 194 | (24) | 28 | (35) |

| Unknowna | 3 | (9) | 59 | (7) | 7 | (9) |

Unknown = Missing response or response of “Prefer not to answer” or “Unknown”

Participation Survey

In the closed-ended questions, respondents most frequently cited the following motivations for joining the study: wanting to know their future risk of cancer (n=664, 81%), wanting information that may help their family (n=476, 58%), knowing their risk for genetic conditions could affect how they take care of themselves (n=384, 47%), wanting to advance research (n=280, 34%), and knowing their risk for genetic conditions may change their healthcare (n=236, 29%). Table 2 shows the complete distribution of motivation- and concern-related closed-ended responses for participants.

Table 2.

CHARM Participation and Incompletion Survey Responses

| Number of closed-ended responses (%) | Representative Open-ended Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Motivations (up to 3 could be selected) | ||

| I want to know my future risk for cancer | 664 (81%) |

“It would be beneficial for me to know what potential problems I am likely to encounter. With this knowledge I can potentially take any known preemptive measures, or be better prepared mentally (not blindsided) if a health condition such as cancer occurs.”

“To learn more about my health and potential risk factors.” |

| I want information that may help my family | 476 (58%) |

“To help the research study and learn more about genetic testing and risks to myself and children”

“Improved Health Outcomes for myself and family based on information to inform healthily living options.” |

| Knowing my risk for genetic conditions may change how I take care of myself (e.g., diet and exercise) | 384 (47%) |

“I believe it give me a good sense of knowledge if the results come back stating i have a possibility of getting cancer. It will also allow me to look into how to treat certain cancers early on.”

“I think is very useful to be able to take preventive action if you find out you are prone to a certain type of cancer.” |

| I want to advance research | 280 (34%) |

“My best friend was recently diagnosed with thyroid cancer and had her thyroid removed. I’m scared for how young we are. She is now in recovery. I have lost both grandfathers and a first cousin to cancer as well. I want to be as prepared as possible for any health issues that may occur. I want to be able to help other people through early detection like my best friend just experienced. It saved her life.”

“I understand how important research is in general with contributing to knowledge, advancements in medicine, etc. I also feel strongly about preventive care and it seems this research may contribute to that cause.” |

| Knowing my risk for genetic conditions may change my healthcare | 236 (29%) |

“To learn about the chance of getting cancer or any other health problem in the near future.”

“Interested in learning more about my genetics and what cancers I’m prone to. This will help inform preventative health care measures.” |

| I like to use the most up-to-date technology | 107 (13%) |

“I’m interested in knowing health info, and genetic tests fascinate me.”

“Curious about my medical chances of cancer and free dna test.” |

| My doctor encouraged me to join | 32 (4%) |

“I was curious as to having genetic testing due to cancer history in my family. My physician referred me to this study and I was very interested.”

“Suggested by PCP that I may qualify based on family history and I am interested in learning everything the study can show. I am fascinated by genetics in medicine.” |

| My family encouraged me to join | 20 (2%) |

“My sister, who is 31, was just diagnosed with breast cancer and tested positive for BRAC1 [sic]. My grandma on my father’s side died of breast cancer when she was 31. We were told to all get tested as a result of this.”

“Wife recommended it because my mother had cancer.” |

| Concerns | ||

| I do not have any concerns | 278 (40%) | “I don’t really have any concerns about joining this study.” |

| I am worried that my genetic test result may be used against me (e.g., by an employer, health insurance company, etc.) | 249 (31%) | “I also have some concerns that this will make it hard to get life insurance if the results are abnormal.” |

| I am worried about how I will cope with the genetic information I will receive | 212 (26%) | “That my anxiety it’s going to be out of control.” |

| I have concerns about my privacy | 198 (24%) |

“Having this information used against me in some way.”

“I’m concerned about having genetic information in a study database, but I am satisfied with how the information is being protected in this case.” |

| It may be hard for me to do the things the study is asking me to do | 64 (8%) |

“I’m not sure the length of time of the research and how long I would need to participate. I’m currently not on any medications except for a b6 supplement. I don’t like taking medications and don’t know if taking medications will be part of the study.”

“I have some mild logistical concerns. I live about an hour from my nearest [hospital system] facility and I have a very full schedule. Time commitment is tricky for me.” |

| I have concerns about participating in research | 34 (4%) |

“What people do with my information and genes.”

“I’m concerned I might find information that is harmful to my health. And that the information may not be accurate.” “There seems to be an open ended use of my results for other research studies and it doesn’t seem like there’s any way of requiring consent for this.” “Having my data collected and stored. I’m somewhat concerned about results indicating I may be developing cancer or another health condition.” |

| Reasons for Declining | ||

| I have concerns about my privacy | 30 (38%) | “Because I do not want to be discriminated against by insurance companies now or in the future based on these results. I realize that currently our laws do not support denying health insurance based on preexisting conditions but there is no guarantee that this will not change in the future. It is too risky to have the results of this test in a persons [sic] medical record.” |

| The things I needed to do to be in the study didn’t work well for me | 15 (19%) |

“I am very limited on personal time and worry that it would be too much of a commitment.”

“I had a death in the family, then a huge family vacation, new job, and moved to a new house over the last 3 months. I just couldn’t get it together to complete the study.” |

| I’m worried about how I will cope with the genetic information I might receive | 15 (19%) |

“Scared to find out results.”

“I’m scared of knowing too much about my health because I don’t want to feel paranoid all the time.” |

| I am not interested in participating in research | 12 (15%) | “It was not something I was interested in at this time.” |

| My current health condition is all I want to focus on right now | 11 (14%) | “I am on a lot of medication already.” |

| I don’t want genetic research results from this study | 11 (14%) | “I decided I don’t want to know.” |

In the open-ended responses about motivations, most respondents (n=773, 95%) described an interest in their personal or family’s health, citing goals that included understanding their family history, improving their health, and making decisions for themselves and their current or future children. Respondents also cited altruistic motivations to help others or contribute to science. Some respondents indicated general curiosity, interest, and/or a desire for knowledge about medical research and other health issues. A small number of respondents also specifically mentioned incentives, that the study was available to them at no cost, and the study’s efforts at improving diversity as reasons for joining. Three responses were omitted due to ambiguity and 17 respondents provided no open-ended response.

In the closed-ended questions about concerns about joining the study, 40% (n=278) of respondents indicated that they had no concerns at all. Others indicated concerns about their results including that their genetic test result might be used against them (n=249, 31%), how they would cope with the genetic information they would receive (n=212, 26%), and privacy (n=198, 24%).

In the open-ended responses about concerns (n=771, 95%), most responses were about the possibility of receiving high-risk results. Some of these respondents specifically noted concerns about passing their genes on to their children. A second set of concerns was about the accuracy, reliability, and/or legitimacy of the study, test, and/or results. Some respondents questioned the accuracy of providing a sample at home or whether their family history was sufficient to get a reliable result. Other common themes included concerns about data use, privacy, insurance, and downstream effects of the study results on their healthcare. Additionally, one respondent noted a concern that they might not understand their results. One response was omitted due to ambiguity and 49 respondents provided no open-ended response.

Incompletion Survey

In the closed-ended questions, respondents most frequently cited concerns about their privacy (n=30, 38%), that the things they needed to do to be in the study didn’t work well for them (n=15, 19%), and/or that they were worried about how they would cope with the information (n=15, 19%) as reasons for not joining. Additional reasons are shown in Table 2.

In the open-ended responses, all respondents (n=79, 100%) commented on priority and timing. Respondents noted that other life events were more urgent, and they didn’t have the time. Some respondents who were recruited in early 2020 specifically indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic had made participating in subsequent study activities a low priority. Other common themes among these respondents included having previously received genetic testing, and concerns about others, such as insurers, having access to their health information. Some respondents raised questions about their suitability for the study, commenting that the study was not the “right fit” for them or vice versa. A few respondents indicated the questions were confusing, there was difficulty interpreting screening results, or they preferred to get testing through their doctor.

Participant Interviews

Motivations

Analysis of interviewees’ responses to questions of why they joined identified several key themes including: (1) personal and family health, (2) altruism or a desire to contribute to research, (3) general curiosity or interest in medicine and research, (4) trust in or the role of their doctor or the healthcare institution, (5) the convenience and affordability of study participation, and (6) the desire to improve representation of underrepresented populations in research. While we oversampled participants with a Spanish language preference, no differences in the key themes were identified. Exemplar quotes are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Interview Quotes from CHARM Participants

| Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Motivations | |

| Personal and family health |

“I guess just to see whether I have a genetic risk for cancer. And if that kind of-- well, if there is a genetic risk, then I would like to be able to share that with my family, my other family members so that they can also get tested and see.”

“Now my grandmother died of cancer, so I’m like, “Do I have cancer too?” I want to know because I just had a baby. I don’t want to leave my baby alone early. If I do have that gene, I want to make sure I do everything to detect it early.” “Because my family-- I thought about the fact that no one in my family gets tested, so many people in my family die of some kind of pain, or have died due to some unknown ache or pain where no one knows what happened. I think it could have been some type of cancer, or I don’t know. So part of it was just as a preventive for my family.” |

| Altruism and desire to contribute to research |

“I work in the medical field, so anything to help contribute to whatever, I’m totally open to. So I was very interested when I got the email and was open to do it.”

“If there’s something that can make the system better and easier for other people, including myself, then why not.” |

| Curiosity and interest | “I’m really interested in DNA, and genealogy, and stuff like that, so I thought it would be-- aside from random blood, like CBCs and stuff, it can tell you on a deeper level what your genome says.” “I’m applying to study epidemiology next year so I was overall interested in that in general.” |

| Trust and role of doctor or institution |

“I’m glad that my doctor was able to find the information [about the study] and was able to tell me about it because I’m not sure if I would’ve been able to-- not necessarily I wouldn’t necessarily never found it on my own, but I’m not sure if I would’ve ever thought about it.” “It’s important since I trust [my healthcare system]. They’re my providers, well, I consider them having my best interests. So since the representative was from [my healthcare system], well, I imagine that she’s someone trustworthy, responsible and all that” “I saw the institutions that were participating, so they all have fairly good reputations when it comes to protecting data. I wasn’t aware of any too major breaches, so that’s what led me to participate.” |

| Convenience and affordability |

“She told me that that form that I was going to complete was free. Because I said, ‘The thing is that I don’t have any money. I don’t have a job. I don’t have the resources to pay for that bill’.” “Because I’m almost always working. I never have a fixed schedule or anything. So when I had the chance, I read it. I mean, they told me people could take the time to do it over the phone or tell the doctor. Right now, everything seems good, but for me the option they gave me was very good.”

“So it didn’t seem to be like it was going to be a ton of time. And it was either I can do it at my next appointment, or you guys could send out the kit to me, so it was relatively easy… It was just easy.” “I mean, the gift cards are a nice perk.” |

| Improving representation of underrepresented groups |

“I was thinking about what populations might be represented in the study and who might be underrepresented and how that might be helpful for me to participate as having multiple underrepresented statuses.”

“[I]t seemed to me very important. Any study is important for our community. Right? For the Latinos, to learn more, because Latinos come from countries that are, well, less developed than the United States, the majority. So, this country, well, gives more information.” “It’s like a big reason why I want to do it to see what this process is like for me so that I can kind of share this experience with other people in the foster care community in [the state].” |

| Concerns | |

| Information access and use |

“I guess the only thing that might make me a little uncomfortable is having my information out there for everybody and anybody. But that’s just what you face these days. Whether you sign up for a study or you sign up with Facebook, everything about you is everywhere, so it might as well be for a good cause, right?”

“I guess you could say that we know that preexisting conditions, at the moment, can’t be held against you and I think it’s just better to know what might be a possibility than not do it because you think some entity will have information about your preexisting condition. So I think that that outweighs the concern in my opinion.” “Right, it didn’t worry me… It seems fine, since it’s medical and not governmental.” “Several [doctors or researchers] were going to share the results and talk about my case… I imagine that as long as there are more opinions, it’s better.” |

| Privacy protections |

“I suppose that the main concern would be that that information could fall into the hands of… people that want to sell it to other folks that want to use it to somehow harm [others]… I think that if the privacy protections weren’t robust-- so, basically, to my understanding, if it weren’t robust for me, I would not have participated.”

“No. Because it said that they were going to share the results, but without identifying people. And if it’s a study and it’s free, well, it doesn’t matter [laughter].” |

1. Personal and family health

Almost all interviewees cited personal and/or family health reasons when reflecting on why they joined the CHARM study. Most wanted to learn their personal risk for cancer and preventative health strategies, with some wondering about their genetic make-up and some citing a distinct fear of cancer. Most also noted their strong family history of cancer spurred them to learn more about their own personal risk, while others wanted to understand their risk because of their personal history of other health problems or lack of knowledge about their family history. For example, one interviewee commented on how the foster system had not provided them with adequate knowledge of their family’s health history.

Many specified that knowing about their risk could help them protect themselves and their families. Some participants mentioned experiencing some anxiety but opted to continue with the study, explaining that they saw it as a tradeoff between the benefit of learning about concerning health information that they could potentially act upon versus being surprised by bad news later, at a point when possibly nothing could be done. A few noted some family members had passed away from unknown causes, which inspired them to join the study to help their families and themselves learn whether hereditary cancers exist within their families.

2. Altruism and desire to contribute to research

About half of interviewees made comments suggesting some sense of altruism or desire to contribute to research. Many of these comments indicated altruistic motivations more broadly and a general wish to help others. Some interviewees spoke specifically about contributing to research, often mentioning how their participation could improve the healthcare system and make things easier for future patients.

3. Curiosity and interest

Almost half of interviewees said their curiosity and interests motivated their participation in the study. Several mentioned a general interest in research and the study while others were curious about medicine and health technologies, particularly genetics. Others noted an interest or desire to educate themselves, including one interviewee who said the subject matter of the study was relevant to their formal education.

4. Trust and role of doctor or institution

Several interviewees said their trust in their doctor or healthcare institution contributed to their decision to participate in CHARM. A few specifically mentioned that they either learned about or were referred to the CHARM study by their doctor. A couple of interviewees mentioned that their healthcare institution’s involvement in the study was important to them and gave credibility to the study, while another commented that they had looked into the partnering institutions to verify their reputations.

5. Convenience and affordability

Some interviewees commented on how the convenience of study participation facilitated their engagement. A couple specifically commented on being able to move through the study at their own pace, another talked about how they would receive their genetic results quicker than through their healthcare system, and others appreciated that they could participate either at home or at another location that was more suitable for them. A few also talked about how participation was easy, whether that was based on the study procedures themselves or the limited time required.

Several interviewees talked about how important it was that study participation imposed no cost on them. These participants often remarked that it was not financially viable for them to pay for testing themselves. For these participants, having access to testing through the study, be it due to convenience, ease, or affordability, was an important motivational factor. Additionally, a few interviewees talked about the gift card incentives offered as a reason for participation.

6. Improving representation of underrepresented groups

A few interviewees talked about how improving representation of underrepresented groups in the study was a motivating factor. Another mentioned that they were curious about which populations would be represented in the study, which ones might be underrepresented, and how their participation might be helpful in strengthening diversity in the study population overall. Similarly, another spoke about how they believed their participation was important for providing more information that could be helpful for their community. Relatedly, an interviewee talked about how they felt that, as someone who went through the foster care system, their participation was important not only for themselves, but for others in the system as well.

Concerns

When asked if they had concerns about participating in the CHARM study, most interviewees reported no concerns. Those that did mostly spoke about privacy concerns regarding their health information but acknowledged that having information “out there” was a part of life now and, ultimately, they felt that the benefits of participation outweighed their concerns. Others noted that they were not concerned due to the protections spelled out in the study materials, for example noting that the promise of de-identification reassured them of their privacy and security, as well as the fact that the information was being collected by a medical institution rather than the government.

When we asked specifically about interviewees’ views on data sharing and privacy, almost all reported no major concerns about sharing their results. However, some did not remember reading about data sharing in the consent materials or did not recall the details; others’ comments suggested they may not have distinguished the concepts of data sharing and results disclosure. Several interviewees commented that they were happy to share their information because it was a necessary part of a research study, and in fact they would expect it would be shared among multiple medical or scientific professionals to ensure high quality results.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that while the primary care patients in our study have similar motivations as those previously identified in research, there are key factors that facilitated participation in the CHARM study. In addition to the desire to learn about personal and family health, an altruistic desire to contribute to research, and a general interest in advancements in medicine, all of which have been reported elsewhere3–9, CHARM participants cited affordability, convenience, and clinical relationships as factors important to their participation. These factors emerged organically through both the interviews and the open-ended responses of the participation survey, suggesting a need to specifically investigate the extent of their role in decision-making. Table 4 illustrates the overlap in motivations and concerns across the data collection methodologies. Further research is needed to better understand how these factors could disproportionately impact the participation of patients from different socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds.

Table 4.

Overlapping motivations and concerns across surveys and interviews

| Participation Survey | Incompletion Survey | Interviews | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivations | |||

| Personal and family health (e.g., future cancer risk; information for family; impact on diet, exercise, and/or healthcare; encouraged by family to join) | X | X | |

| Altruism and desire to contribute to research (e.g., advance research) | X | X | |

| Curiosity and interest (e.g., using the most up-to-date technology) | X | X | |

| Trust and role of doctor or institution (e.g., encouraged by doctor to join) | X | X | |

| Encouraged by family to join | X | ||

| Convenience and affordability | X | X | |

| Improving representation of underrepresented groups | X | X | |

| Incentives | X | ||

| Concerns/ Reasons for declining | |||

| No concerns | X | X | |

| Information access and use | X | X | |

| Privacy protections | X | X | X |

| Coping with genetic information | X | X | |

| Participation may be burdensome | X | X | |

| Receiving high-risk results | X | ||

| Accuracy, reliability, and/or legitimacy of the study, test, and/or results | X | ||

| Downstream effects of the study results on healthcare | X | ||

| Not interested in participating in research | X | ||

| Focusing on current health condition | X | ||

| Did not want genetic results from the study | X | ||

| Other priorities/timing | X |

Given that the CHARM study was embedded in a clinical setting, the identification of these facilitating factors could also prove useful to improving access to genomic medicine more broadly18. As practices are translated from the research setting to the clinical setting, this increased understanding of how these three factors impact the uptake of genomic medicine could lead to greater and more equitable access to care. Future research should continue to explore a range of issues related to these three factors, for example the role of insurance in addressing cost barriers, accessibility of genomic research studies, and the impact of varying degrees of trust and respect in clinical relationships on translational research.

Critical to ensuring that both research and genomic medicine are accessible are the elements of affordability and convenience. Some participants were acutely aware of the cost of such services and noted the importance of the study providing testing at no expense to the participant. This highlights the cost of genetic services through standard clinical avenues as a barrier, echoing previous findings of cost as a barrier to preventive cancer screening19–21. Importantly, cost and insurance coverage may also affect access to downstream healthcare and social services that may be recommended based on genetic screening results18. Efforts to address cost barriers are therefore needed not only at the point of screening, but also for the services that genetic screening facilitates.

Where participants commented on convenience, they often noted how it was helpful to them that they could participate at their own pace, at any location, during a time that worked for them. The CHARM study did not require in-person visits at any step in the process. Our findings suggest that efforts to increase access through convenience, especially for those where time is a major constraint, may be aided by developing study or clinical procedures that are flexible, can accommodate schedules of varying types, and do not require face-to-face visits. This aligns with prior findings that lack of time or conflicting obligations serve as barriers to cancer screening22,23. Given the disproportionate impact of high costs and inaccessibility on underserved communities, improving access to genetic services through research studies by eliminating cost to participants and making participation accessible at a variety of times and locations could prove an important pathway to increasing diversity and improving care in underserved communities.

Participation was also facilitated by learning about or being referred to the study by their primary care clinicians. This finding aligns with prior research that demonstrated that screening uptake was related to patient-clinician communication24,25. While there may be ethical concerns about clinician involvement in research enrollment in some situations26, and many individuals may not have a strong, established relationship with a primary care clinician27,28, some participants pointed to the trusting relationship they had with their primary care clinician as a critical element to their participation. This suggests that working with clinicians to raise their patients’ awareness of relevant research studies or improve their ability to answer their patients’ questions may prove helpful in addressing the persistent issue of a lack of diverse representation in clinical genomic implementation research, at least for those patients who have existing relationships with a trusted clinician. These findings provide further evidence that in situations where participation in research approximates care received in a health care setting, many participants have a preference for their clinician’s involvement29–31. Our findings also support the need to address systemic issues in the medical system – for example, a lack of cultural humility, language services, and insurance coverage – that create and exacerbate disparities in which patients are able to develop long-term relationships with clinicians through which they may learn about research opportunities28.

While our results indicated some concerns about data usage and privacy, consistent with previous research10,12, these concerns were often allayed by the protections described in the consent materials, trust in the institutions conducting the research, or recognition of the realities of data and privacy in modern society. Despite specifically asking participants about their concerns about joining the study, most responded with concerns about their personal or family’s health, suggesting that for most of our participants health concerns superseded any concerns about study-specific risks. However, it should be noted that concerns about privacy was the key reason identified by those who declined to participate. As noted above, despite some interviewees acknowledging data and privacy concerns as a part of life in our increasingly technology-dependent world, survey responses from those who did not join suggest that privacy concerns remain salient for some. This illustrates the importance of ensuring that expectations for data sharing and privacy protections are described clearly and accessibly during the consent process to empower individuals to decline if they wish.

Limitations

The results of this study are limited by the characteristics of the CHARM cohort, which consists of individuals based at two clinical locations who use either English or Spanish. Future research should incorporate primary care patients from other cultural backgrounds and/or language groups to determine if the same set of motivations and concerns are salient across other groups. While we made efforts to ensure diverse representation in our interview sample, including offering interviews at a variety of times, we acknowledge the potential for self-selection bias as well as interview scheduling limitations. There is also potential for selection bias among those who responded to the survey of those who did not join the CHARM study. Additionally, we were not able to gain deeper insight into the perspectives of those who did not complete enrollment through interviews due to lack of response. Nevertheless, our mixed-methods approach allowed us to mitigate the limitations of any single method and appreciate the perspectives of a broad range of study participants.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that beyond the motivation to learn about genetic risks to one’s personal or family health and the altruistic desire to contribute to medical research, participation in genomics implementation research is also facilitated by study processes that reduce barriers related to accessibility and cost. Efforts to increase diverse representation in clinical genomics implementation research and increase access to genetic services through primary settings must consider individuals’ finances, their time and obligations, and their relationship with their primary care provider. Addressing these potential barriers could prove an important next step in improving representation in implementation research and advancing equity in uptake for early detection and intervention of hereditary disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the many members of the CHARM study team who contributed to this project. We would also like to acknowledge the invaluable input provided by our Patient Advisory Committees, our Patient Representatives, and all CHARM participants. This work was funded as part of the Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research (CSER) consortium funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute with co-funding from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The CSER consortium represents a diverse collection of projects investigating the application of genome-scale sequencing in different clinical settings including pediatric and adult subspecialties, germline diagnostic testing and tumor sequencing, and specialty and primary care. This work was supported by a grant from the National Human Genome Research Institute (U01HG007292; MPIs: Wilfond, Goddard), with additional support from U24HG007307 (Coordinating Center). The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The CSER consortium thanks the staff and participants of all 7 CSER studies for their important contributions. More information about CSER can be found at https://cser-consortium.org/.

Footnotes

Ethics Declaration

This study was approved by the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants as required by the IRB.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Availability

Data are available upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murray MF, Giovanni MA, Doyle DL, et al. DNA-based screening and population health: a points to consider statement for programs and sponsoring organizations from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2021;23(6):989–995. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-01082- [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hindorff LA, Bonham VL, Brody LC, et al. Prioritizing diversity in human genomics research. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19(3):175–185. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2017.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Facio FM, Brooks S, Loewenstein J, Green S, Biesecker LG, Biesecker BB. Motivators for participation in a whole-genome sequencing study: implications for translational genomics research. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(12):1213–1217. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gollust SE, Gordon ES, Zayac C, et al. Motivations and perceptions of early adopters of personalized genomics: perspectives from research participants. Public Health Genomics. 2012;15(1):22–30. doi: 10.1159/000327296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kauffman TL, Irving SA, Leo MC, et al. The NextGen Study: patient motivation for participation in genome sequencing for carrier status. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2017;5(5):508–515. Published 2017 Jul 2. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis KL, Heidlebaugh AR, Epps S, et al. Knowledge, motivations, expectations, and traits of an African, African-American, and Afro-Caribbean sequencing cohort and comparisons to the original ClinSeq® cohort. Genet Med. 2019;21(6):1355–1362. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0341-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baptista NM, Christensen KD, Carere DA, Broadley SA, Roberts JS, Green RC. Adopting genetics: motivations and outcomes of personal genomic testing in adult adoptees. Genet Med. 2016;18(9):924–932. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nuytemans K, Manrique CP, Uhlenberg A, et al. Motivations for Participation in Parkinson Disease Genetic Research Among Hispanics versus Non-Hispanics. Front Genet 2019;10:658. Published 2019 Jul 16. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owen-Smith AA, Woodyatt C, Sineath RC, et al. Perceptions of Barriers to and Facilitators of Participation in Health Research Among Transgender People. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):187–196. Published 2016 Oct 1. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanderson SC, Linderman MD, Suckiel SA, et al. Motivations, concerns and preferences of personal genome sequencing research participants: Baseline findings from the HealthSeq project [published correction appears in Eur J Hum Genet. 2016 Jan;24(1):153]. Eur J Hum Genet 2016;24(1):14–20. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scherr CL, Aufox S, Ross AA, Ramesh S, Wicklund CA, Smith M. What People Want to Know About Their Genes: A Critical Review of the Literature on Large-Scale Genome Sequencing Studies. Healthcare (Basel). 2018;6(3):96. Published 2018 Aug 8. doi: 10.3390/healthcare6030096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amendola LM, Robinson JO, Hart R, et al. Why Patients Decline Genomic Sequencing Studies: Experiences from the CSER Consortium. J Genet Couns. 2018;27(5):1220–1227. doi: 10.1007/s10897-018-0243-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilmore MJ, Schneider J, Davis JV, et al. Reasons for Declining Preconception Expanded Carrier Screening Using Genome Sequencing. J Genet Couns. 2017;26(5):971–979. doi: 10.1007/s10897-017-0074-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mittendorf KF, Kauffman TL, Amendola LM, et al. Cancer Health Assessments Reaching Many (CHARM): A clinical trial assessing a multimodal cancer genetics services delivery program and its impact on diverse populations. Contemp Clin Trials. 2021;106:106432. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2021.106432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kraft SA, Porter KM, Duenas DM, et al. Participant Reactions to a Literacy-Focused, Web-Based Informed Consent Approach for a Genomic Implementation Study. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2021;12(1):1–11. doi: 10.1080/23294515.2020.1823907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutierrez AM, Robinson JO, Outram SM, et al. Examining Access to Care in Clinical Genomic Research and Medicine: Experiences from the CSER Consortium. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science. 2021:1–43. doi: 10.1017/cts.2021.855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akinlotan M, Bolin JN, Helduser J, Ojinnaka C, Lichorad A, McClellan D. Cervical Cancer Screening Barriers and Risk Factor Knowledge Among Uninsured Women. J Community Health. 2017;42(4):770–778. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0316-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gakunga R, Kinyanjui A, Ali Z, et al. Identifying Barriers and Facilitators to Breast Cancer Early Detection and Subsequent Treatment Engagement in Kenya: A Qualitative Approach. Oncologist. 2019;24(12):1549–1556. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H, Roy S, Kim J, Farazi PA, Siahpush M, Su D. Barriers of colorectal cancer screening in rural USA: a systematic review. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19(3):5181. doi: 10.22605/RRH5181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung MY, Holt CL, Ng D, et al. The Chinese and Korean American immigrant experience: a mixed-methods examination of facilitators and barriers of colorectal cancer screening. Ethn Health. 2018;23(8):847–866. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2017.1296559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagelhout E, Comarell K, Samadder NJ, Wu YP. Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Racially Diverse Population Served by a Safety-Net Clinic. J Community Health. 2017;42(4):791–796. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0319-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dolan NC, Ramirez-Zohfeld V, Rademaker AW, et al. The Effectiveness of a Physician-Only and Physician-Patient Intervention on Colorectal Cancer Screening Discussions Between Providers and African American and Latino Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1780–1787. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3381-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kindratt TB, Dallo FJ, Allicock M, Atem F, Balasubramanian BA. The influence of patient-provider communication on cancer screenings differs among racial and ethnic groups. Prev Med Rep. 2020;18:101086. Published 2020 Apr 2. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morain SR, Joffe S, Largent EA. When Is It Ethical for Physician-Investigators to Seek Consent From Their Own Patients?. Am J Bioeth. 2019;19(4):11–18. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2019.1572811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doescher MP, Saver BG, Franks P, Fiscella K. Racial and ethnic disparities in perceptions of physician style and trust. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(10):1156–1163. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper LA, Beach MC, Johnson RL, Inui TS. Delving below the surface. Understanding how race and ethnicity influence relationships in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S21–S27. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00305.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho MK, Magnus D, Constantine M, et al. Attitudes Toward Risk and Informed Consent for Research on Medical Practices: A Cross-sectional Survey. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(10):690–696. doi: 10.7326/M15-0166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelley M, James C, Alessi Kraft S, et al. Patient Perspectives on the Learning Health System: The Importance of Trust and Shared Decision Making. Am J Bioeth. 2015;15(9):4–17. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2015.1062163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraft SA, Cho MK, Constantine M, et al. A comparison of institutional review board professionals’ and patients’ views on consent for research on medical practices. Clin Trials. 2016;13(5):555–565. doi: 10.1177/1740774516648907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.