Abstract

We treat health as a form of human capital and hypothesize that women with more human capital face stronger incentives to make costly investments with future payoffs, such as avoiding abusive partners and reducing drug use. To test this hypothesis, we exploit the unanticipated introduction of an HIV treatment, HAART, which dramatically improved HIV+ women’s health. We find that after the introduction of HAART HIV+ women who experienced increases in expected longevity exhibited a decrease in domestic violence of 15% and in drug use of 1520%. We rule out confounding via secular trends using a control group of healthier women.

Keywords: Domestic Violence, Drug Use, Risky Behavior, Health, Human Capital, Medical Innovation, HIV/AIDS

Keywords: I1, J12, J24, O39

I. Introduction

Domestic violence is tragic, rampant, and costly. In the U.S., there are about 4.5 million instances of domestic violence each year, and about 22% of women will be physically assaulted by an intimate partner at least once in their lives (Tjaden and Thoennes, 2000). The annual cost of domestic violence—including direct medical expenditures and losses to productivity— is estimated at $5.8 billion.1

Counting productivity losses as well as direct healthcare expenditures highlights two important relationships. The first is the well-established relationship between domestic violence and poor labor market outcomes. This relationship reflects how factors such as low education or drug abuse can increase the likelihood of violence and simultaneously discourage successful employment. Previous literature has shown that it also reflects causality in both directions. Abuse can deter human capital accumulation or undermine a woman’s success at work, and women with few resources, poor labor market prospects or low earnings have fewer options outside violent partnerships (Browne et al., 1999; Swanberg and Macke, 2006; Aizer, 2010).

Less understood is the relationship between health and domestic violence. Poor health and chronic illness have been shown to be associated with abuse, once again reflecting how underlying factors (e.g., lack of education and drug abuse) contribute to both (Black et al., 2011). Mechanically, this relationship is also causal, at least in one direction: violence, by its nature, potentially damages health. However, scant attention has been paid to the causal effect of health on a woman’s likelihood of suffering abuse.

This paper studies the impact of the introduction of an unanticipated breakthrough medical innovation, Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Therapy (HAART), on domestic violence among a sample of women who are infected with HIV (HIV-positive, henceforth HIV+).2 A threshold question is why we might expect HAART to reduce violence. As we explain below, our analysis focuses on women who were HIV+, but not yet symptomatic. For these women, HAART had no immediate impact on symptoms, but instead improved expected health and lengthened expected lifespans, which incentivized them to make costly upfront investments with future payoffs. We treat the avoidance of domestic violence, including exiting an abusive relationship, as such an investment. While the benefits are obvious, the immediate costs of avoiding domestic violence may include temporary homelessness or escalated threats of physical harm when a woman attempts to leave an abusive partner.3 More broadly, we view health as a form of human capital that not only increases longevity, but also improves the quality of life and increases labor market productivity (Grossman, 1972; Becker, 2007). Viewed in this way, HAART enhanced women’s expected future well-being and economic resources, such as income, further improving options outside of violent partnerships. Following similar logic, we assess the effect of HAART on another investment with upfront costs and future payoffs: reducing the use of illicit drugs. Upfront costs include withdrawal symptoms and depression, while benefits include better future health and fewer barriers to employment. Consistent with the view that a medical innovation can incentivize these types of investments, we find that HAART led to decreases in both domestic violence and illicit drug use among HIV+ women.

Our paper uses data from a longitudinal study, the Women’s Intra-Agency HIV Study (henceforth, WIHS ), which provides rich information on health, sociodemographic characteristics, domestic violence and illicit drug use. Women in the sample are predominantly black and report lower income and education attainment than average U.S. women. This is an appropriate sample for our study since U.S. women with these characteristics are disproportionately affected by HIV (Pellowski et al., 2013).4 Moreover, three key features of HIV make it an appropriate setting for our study. First, the severity of HIV infection coupled with the effectiveness of HAART resulted in effect sizes large enough to detect the nuanced causal effects of an unanticipated medical innovation on domestic violence and drug use. Untreated HIV leads to immune system deterioration (known as AIDS) after which fairly routine infections cause grave symptoms, illness and death.5 HAART effectively transformed HIV infection from a virtual death sentence into a manageable, chronic condition, reducing mortality rates by over 80% within two years of its introduction (Bhaskaran et al., 2008).6 Second, because the introduction of HAART was unanticipated, it provides a quasi-experiment that allows us to identify causal effects of a positive shock to expected health and longevity. Third, we observe an objective, time-varying, continuous measure of underlying immune system health— the CD4 count, defined as the number of white blood cells per cubic millimeter of blood. Crucially, women participating in the study are informed of their CD4 count and can therefore respond to it. We exploit this to develop our identification strategy.

To identify causal effects of HAART on domestic violence and illicit drug use, we could simply compare HIV+ women before and after the introduction of HAART. However, this approach could confound the causal impact of HAART with other secular trends unrelated to the introduction of HAART. Instead, we estimate causal effects using difference-in-differences, comparing women with similar physical symptoms, but differences in their pre-HAART CD4 counts.7 Our treatment and control groups allow us to test our hypothesis that longer expected survival incentivizes costly upfront investments. This implies that HAART should lead to larger shifts in such investments among women with lower pre-HAART CD4 counts, who experienced larger increases in expected survival. Following this logic, our treatment group consists of HIV+ women who, prior to HAART introduction, exhibited CD4 counts low enough that medical guidelines suggest they commence treatment. Our control group consists of women with higher CD4 counts, whose immune systems had not yet begun to decline; these women faced longer pre-HAART expected survival and thus smaller HAART-induced increases in their expected survival.8 A concern is that differences in CD4 counts between these two groups are endogenous. To address this concern, we omit women from our treatment group with CD4 counts that are so low that they might have already experienced the symptoms of compromised immune systems (AIDS). Omitting these women helps ensure that women in the treatment group and control group are comparable: they are distinguished by a CD4 count cutoff, but are similar on other dimensions, including a lack of physical symptoms.

Both our identification strategy and the conceptual framework we develop to explain why HAART affected violence and drug use rely on the assumption that HAART affected behavior by shifting incentives to make costly investments with future payoffs. However, there is an important distinction between the two. Our identification strategy relies on the assumption that HAART affected the incentives and, hence, the behavior of sicker HIV+ women relatively more than healthier HIV+ women. This assumption motivates our focus on two groups of relatively similar women distinguished by a CD4 count cutoff. Our conceptual framework suggests that all HIV+ women potentially respond to HAART, including the high-CD4 count HIV+ women, who comprise our control group, although they are predicted to respond less than the HIV+ women with lower CD4 counts, who comprise our treatment group.9 A drawback of our identification strategy is therefore that we may miss some portion of the true causal impact of HAART by including high-CD4 count women who were potentially “treated” by HAART in our control group. This implies that our estimates of the impact of HAART on domestic violence and drug use are likely to be biased downward, so we interpret them as lower bounds of true causal effects.

Using the identification strategy described above, we show that HAART led to reductions in domestic violence of roughly 15% for the treatment group relative to the control group. We also assess the effect of HAART on the use of illicit drugs, in particular, cocaine and heroin.10 We show that the medical breakthrough we study led to decreases in illicit drug use of about 1520%. Our results are robust when considering domestic violence and the use of heroin. Our cocaine results are weaker and sensitive to the specification and therefore must be interpreted with caution. More broadly, and because we focus on women without symptoms of HIV, our findings provide support for the following claim: health innovations can affect people not only by making them feel better (e.g., by reducing their physical symptoms), but also by improving their expected future health, which incentivizes them to make costly investments. On this point, our work relates to Oster et al. (2013), who provide another example of how individuals’ investments in their own human capital respond to new information about their future health even in the absence of discernible changes in their immediate health.

After providing evidence that HAART introduction substantially reduced violence and illicit drug use, we turn to exploring mechanisms. First, we investigate whether HAART affected violence and drug use independently or affected one of these solely through its effect on the other. Though it is difficult to say definitively with the data we have, we provide some evidence that HAART affected both outcomes even after we control for the correlation between domestic violence and drug use via joint estimation.

Second, we examine whether our results are explained by contemporaneous changes in mental health (measured as depressive symptoms) or physical symptoms (measured as physical ailments, such as fever, night sweats and weight loss, associated with AIDS). While treatment group women exhibited relatively large increases in CD4 count, they did not experience relatively large improvements in their mental and physical health due to HAART. These findings show that the estimated effects of HAART on domestic violence and drug use are not attributable to immediate improvements in mental or physical health, but to better expected health and longer expected lifespans.11

Third, we explore whether the effect of HAART on violence and drug use can be explained by changes in labor market outcomes. We show evidence of increases in employment among women in the treatment group relative to the control group after the introduction of HAART. Improvements in labor market outcomes are consistent with the view that HAART led to an upward shift in expected health, which in turn improved women’s outcomes on a variety of dimensions, including violence, drug use, and employment.

This study is the first to provide evidence that interventions that increase women’s expected health and longevity or otherwise augment their human capital can reduce both domestic violence and illicit drug use. The potential policy relevance of our findings is amplified by the fact that it is not always clear which policies most effectively reduce these behaviors. In the case of domestic violence, for example, there have been large declines over time, which are not yet fully understood (Black et al., 2011). Earlier work has suggested that increases in women’s earnings relative to men’s have contributed to this decline, which implies a role for women’s labor market human capital (Aizer, 2010).12 We are cautious about extrapolating our results to other types of health shocks (or to shifts in other forms of human capital) since HIV is a specific chronic condition and the introduction of HAART was an unusually large and unanticipated pharmaceutical innovation. However, the introduction of HAART provides a unique opportunity to test whether a particular type of exogenous increase in health human capital could also play a role in reducing violence and illicit drug use.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the data set used in this project and presents a preliminary data analysis. Section 3 discusses how we link health to domestic violence and illicit drug use, first conceptually and then empirically. Section 4 presents our main econometric results concerning the effect of HAART on violence and drug use. Section 5 examines some possible mechanisms explaining our main results, including reductions in physical symptoms and depression and increases in employment. Section 6 speculates on the broader implications of our results and concludes.

II. Data

In this section, we introduce the data set we use in our analysis and discuss construction of our analytic sample.

A. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study

We employ a unique data set from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). The study was initiated to investigate the impact of HIV on women in the United States, and the sample was selected to include both HIV+ and uninfected or HIV-negative (henceforth: HIV–) women.13 Women in the WIHS study are predominately black and low-income and exhibit low levels of education. This reflects efforts to create a sample of women who are representative of U.S. women with HIV. Participants were recruited from a variety of venues, including: HIV primary care clinics, hospital-based programs, research programs, community outreach sites, women’s support groups, drug rehabilitation programs, HIV testing sites and referrals from enrolled participants (Barkan et al., 1998). The study began in 1994, and a second cohort was added to the sample in 2001–2002. Each woman in the sample was enrolled in one of six clinical consortia, located in: Bronx/Manhattan, New York; Washington, DC; San Francisco/Bay Area; Los Angeles/Southern California/Hawaii; Chicago, IL; and Brooklyn, New York. Semi-annual interviews are ongoing. Women were compensated for participation with monetary remuneration, gift packs, bathing and laundry facilities, meals, transportation and access to dental care at some sites. In addition, services such as HIV counseling, health assessments, health education and referral to clinical trials, primary care and social services were provided. For more information on the WIHS, see Barkan et al. (1998).14

The WIHS data set is well-suited for use in assessing the causal effect of medical innovation on domestic violence and illicit drug use. First, because the WIHS started interviewing women in October 1994, before HAART became widely available in late 1996, we observe women before and after the unanticipated medical innovation and can compare women based upon their pre-treatment characteristics. For women in our main analysis, there were about four visits before the introduction of HAART. Second, there was an additional cohort added in 2001–2002, after the introduction of HAART. Although not included in our main sample, we use this additional cohort in a series of robustness checks to assess the potential effects of participation in the study. Simply participating in WIHS can be beneficial to the participants, and we use the additional cohort to separate the effect of being a WIHS participant from the effect of medical innovation.15 Third, the data set includes a rich set of behavioral, sociodemographic and health variables. Information is elicited on employment, income, housing, relationship and marital status, sexual behaviors, illicit drug use, and medication use.16

To quantify health, we use a standard measure of immune system functionality, CD4 count, defined as the number of white blood cells per mm3 of blood. CD4 count is measured using plasma samples, which are collected by medical professionals. Thus, the health measure that we use is objective rather than self-reported. Importantly, after each measure was taken, study participants were informed of their CD4 count. For healthy HIV– individuals, average CD4 counts range between 500 and 1,500. For HIV+ individuals, lower counts indicate that immune system deterioration has commenced, with counts below 200 signaling high susceptibility to common illnesses (a condition known as AIDS). Guidelines recommend starting HAART as CD4 counts decrease, generally once the CD4 count reaches 350 (Mocroft and Lundgren, 2004; AIDSinfo, 2014). Monitoring CD4 cells allows individuals to track their immune system health, with lower CD4 reflecting a weaker immune system, sometimes known as immunosuppression. For example, a woman with a CD4 count of 400 is extremely unlikely to experience symptoms of immunosuppression, but because she has been told her CD4 count, she is likely to be aware that her immune system health has begun to decline and that her chances of long-run survival are therefore lower than those women whose CD4 count is still within the 500–1500 range typical among HIV– women.

Our measure of domestic violence indicates whether women reported experiencing any of three forms of violence in the six months prior to their interview: physical abuse, sexual abuse, or coercion by an intimate partner or spouse. These data are thus uniquely rich in including several forms of violence and not just one or two. We classify the woman as having experienced coercion if a partner threatened to hurt or kill her or prevented her from leaving or entering her home, seeing friends, making telephone calls, getting or keeping a job, continuing her education, or seeking medical attention. Moreover, we do not require that women report being in a relationship in order to report domestic violence. Indeed, many women report not being in a relationship at visits t and t+1 and also report domestic violence between the same two visits. This might occur if a woman has a short-term intimate partner who abuses her. Because we do not condition experiencing domestic violence on being in a relationship, we bypass problems that arise if HAART affected selection into a long-term partnership such as marriage or cohabitation.

B. Construction of the Analytic Sample

The main analytic sample includes all women from the first WIHS cohort who were HIV+ and answered questions about outcomes including domestic violence, illicit drug use and employment, as well as all of the controls that we include.17 The first cohort of the WIHS data set includes 2,071 HIV+ women who participated in the study for up to 33 visits, between October of 1994 and April of 2010. This amounts to 47,149 person-visits. Observations are excluded from the analytic sample for a number of reasons. First, starting in the 10th visit, questions about domestic violence were only asked every other visit. Once we account for the change in timing, we are left with 2,065 individuals and 30,135 person-visits.18 Second, we exclude 53 women who were in the study for just one visit before their death. Third, for women who died during the study period, the last “visit” is a record of their death; when we drop these “visits,” we are left with 2,012 individuals and 29,492 person-visits. Fourth, we drop observations that are missing basic information such as date of visit, CD4 count before the introduction of HAART, or age, leaving us with 23,215 observations from 1,995 individuals.19 Last, we trim observations that are missing information about domestic violence, drug use, employment, income or relationship status, leaving us with 13,948 person observations from 1,055 individuals.20 Although we use an unbalanced panel, 73% of our sample stayed in the study for all 33 visits.21

A legitimate concern is the large number of missing observations. Reassuringly, we do not find evidence that observations are missing differentially for treatment versus control groups. To evaluate whether individuals are non-randomly missing from our sample, we perform two main tests. First, we show that demographics, being in the treatment group, and experiencing violence pre-HAART are not related to the likelihood of leaving the sample or the number of visits that one stays in the sample. We construct an indicator variable for ever leaving the sample and estimate logit regressions where the outcome is leaving the sample for any reason and explanatory variables are being in the treatment group, race, age, site of visit, and experiencing violence pre-HAART. No controls are significantly correlated with leaving the study. As a complementary test, we also regress the number of visits that the woman stayed in the study and find no evidence that any control variable is correlated with this outcome. Results from these estimates can be found in Appendix Table A1.

In our second test, we also regress an indicator variable for missing each outcome (domestic violence, cocaine use, heroin use, or employment) on race indicators, age, age squared, site indicators, logged CD4 count, and an interaction between the treatment group and logged CD4 count.22 The coefficient of the interaction term between the treatment group and logged CD4 count will tell us if women from the treatment group exhibit patterns of “missingness” that differ from those of the other women in the study. Women are included in this regression if they made the first three trims of the data as described above. We focus on this subsample because they are the women for whom we have information about basic sociodemographics. While we do find that women who are less healthy in terms of a lower CD4 count are more likely to be missing observations, as shown in Appendix Table A2, the actual changes in the probability of missing data for these outcomes are quite small. A 10% increase in CD4 count decreases the probability of nonresponse by roughly 0.2 percentage points. Further, and more importantly, there is no difference between the treatment and control groups in terms of how CD4 count affects the probability of having a missing outcome. Thus, we find that, while health may affect the probability of an individual having a missing outcome, it does not do so differentially across our treatment and control groups.

III. Conceptual Framework and Research Design

A. Conceptual Framework

We begin with the premise that health is a form of human capital that not only extends life, but also improves well-being and increases productivity (Grossman, 1972). Because our sample consists of women without symptoms, our focus is on the impact of increases in expected health and longevity. Consider a woman in an abusive partnership or addicted to drugs. She could take a costly step, such as leaving her abusive partner or getting off drugs, reaping the benefits in the future. Since the costs of these actions are incurred in the present and the benefits accrue in the future, we treat these actions as investments. Longer expected lifespans mean women have a longer time to enjoy the benefits of these investments. Better expected health can also improve future productivity and raise expected earnings. This could further incentivize women to leave abusive partners or to stop using drugs in an effort to increase their likelihood of being employed. In the context of HIV, HAART increased expected health and longevity of HIV+ women. We thus hypothesize that HAART leads to lower levels of domestic violence and illicit drug use among HIV+ women.

A potential problem with this conceptual framework is that it presumes that women have some ability to control both violence and drug use. In the case of illicit drug use, addiction may mean that women are unable to change their behavior even in the face of a strong shift in incentives, such as a large positive shock to future health and longevity. Rooted in rational addiction (Becker and Murphy, 1988), we assume that women make rational choices regarding their drug use, weighing the benefits of continued use against the costs. This assumption is supported by clinical evidence showing that illicit drug use is responsive to shifts in incentives (Hart et al., 2000).23 Robins (1993), who documented the rapid recovery from heroin addiction among Vietnam veterans upon their return home, provides earlier evidence in favor of control or agency in the context of addiction. One interpretation of her findings consistent with our conceptual framework is that these veterans faced stronger incentives to avoid heroin following a positive shock to their lifespan.

The application of our conceptual framework to domestic violence is more delicate. The assumption that women can “choose” to end abuse perpetrated by a violent partner can erroneously be perceived as “blaming the victim” for her own abuse. That is not the case. Assessing women’s choices in this context sheds light on the difficult tradeoffs abused women face, their lack of alternatives and the types of interventions that can reduce violence. In our case, we relate violence to health human capital. To do this, we draw upon the resource theory of domestic violence. Often attributed to Gelles (1976), the claim is that women with more resources have better options outside of abusive partnerships and are therefore more likely to leave violent partners, which could incentivize the partner to be less violent. For example, if a woman’s outside option is safe and comfortable, she is more likely to leave a violent partner. The resource theory helps to explain why women with higher education or income are more likely to avoid domestic violence. The theory has been used to motivate bargaining theories of domestic violence. In bargaining models, women with better outside options have higher threat points. Because of this, they can credibly threaten to leave partners and therefore experience less violence. Resource and bargaining theories of domestic violence have been used to explain why no-fault divorce has reduced domestic violence (Stevenson and Wolfers, 2006), why cash transfers to poor women can reduce abuse (Bobonis et al., 2013; Angelucci, 2008; Pronyk et al., 2006), and why abuse is associated with poor labor market outcomes (Bowlus and Seitz, 2006; Anderberg and Rainer, 2013) and a larger gender wage gap (Aizer, 2010).24 We take no position on intra-partnership bargaining. Rather, we argue simply that HAART increased women’s expected health and longevity, thus strengthening their incentives to leave, to threaten to leave or to avoid violent partners. Our next task is to test this hypothesis by identifying the causal impact of HAART on these outcomes.

B. Identifying the Impact of HAART on Violence and Drug Use

Our aim is to identify how HAART-induced increases in expected health and longevity affected domestic violence or illicit drug use. One possibility is to examine HIV+ women before and after HAART, but this would not allow us to separate secular time trends or other contemporaneous shifts in the impact of HAART. For example, between 1993 and 2010, domestic violence was trending downward (Catalano, 2012). To achieve identification, our approach exploits variation in health status at the time of HAART introduction along with the fact that HAART was an unanticipated innovation. The passage of time from the pre- to the post-HAART era affects our outcomes (domestic violence and illicit drug use) through the impact of HAART availability on expected health and longevity.

Formally, we compute the difference-in-differences, relying on variation in how women respond to exogenous shifts in medical technology depending on their health status at the time of the innovation. Our treatment group consists of women who were beginning to exhibit HIVinduced immune system deterioration, which typically precedes full-blown AIDS, but who had not yet exhibited AIDS-level CD4 counts. These are women whose minimum CD4 count prior to HAART was between 300 and 399. Medical guidelines recommend beginning HAART when the CD4 count reaches 350, and our treatment group encompasses this number. However, since women in the treatment group have yet to reach CD4 counts where they would experience physical illness due to AIDS, they are more comparable to healthier women, whom we use as controls. The control group consists of women in relatively good health: HIV+ women with high CD4 counts that never dipped below 400 prior to HAART introduction. Of those eligible to be included in our analysis, 166 women, with a total of 2,477 person-visits, are in the treatment group, and 269 women, with a total of 4,192 person-visits, are in the control group.25

Our identification strategy assumes that sicker women respond more strongly to HAART than healthier women. We explain this assumption in the case of domestic violence, but the explanation for illicit drug use is analogous. We envision women facing a dynamic tradeoff when deciding whether or not to avoid abuse. Avoiding abuse entails immediate upfront costs (e.g., leaving an abusive partner and potentially facing homelessness (Zorza, 1991)), but also confers benefits in the form of lower abuse in the future. In this sense, avoiding abuse is similar to an investment with upfront costs and future benefits. Women with lower survival probabilities face a shorter expected lifespan and thus a shorter period during which to enjoy the returns from their investment. As a result, larger increases in survival probability incentivize larger shifts in costly behaviors with long-run payoffs.26 In response to HAART, women in the treatment group should experience larger increases in survival probability than women in the control group for two reasons. First, medical guidelines regarding commencement of HAART mean that women in the control group are less likely to use it compared to women in the treatment group. Second, women in the treatment group are likely to experience increases in their survival probabilities sooner than those in the control group. HAART does not raise the survival probabilities of women in the treatment group above those of women in the control group, but simply raises them to the same level. Starting from a lower level and ending at the same level, the women in the treatment group experience a larger change in survival probabilities. This implies that women in the treatment group face larger HAART-induced shifts in incentives to make costly investments in their human capital compared to women in the control group and, hence, the effects would be larger for women in the treatment group.

We note, however, that because healthier women were likely to experience CD4 declines soon, they were also potential beneficiaries from HAART and may have also changed their behavior in response to the innovation. To the extent that healthier HIV+ women also reacted to the introduction of HAART, using them as a control group leads us to underestimate the effect of HAART.

C. Descriptive Statistics

Before assessing the validity of our approach, we present summary statistics for the treatment and control groups. We also discuss how the women in our sample compare to other women in the U.S., including HIV+ women, a comparison that is important when assessing the external validity of our results. Table 1 provides summary statistics for our treatment group and control group in Columns 1 and 2. In Column 3, we test that the means are equal across the treatment and control groups.

Table 1:

Summary Statistics

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment group | Control group | Equal means p-value | |

|

| |||

| Average age | 42 | 41 | 0.23 |

| African American | 67 | 64 | 0.41 |

| Hispanic | 20 | 22 | 0.68 |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 12 | 12 | 0.95 |

| Other race | 1 | 3 | 0.13 |

|

| |||

| Education: | |||

| LT high school | 37 | 41 | 0.51 |

| High school grad | 30 | 30 | 0.94 |

| Some college | 23 | 22 | 0.82 |

| College grad | 10 | 7 | 0.34 |

|

| |||

| Pre-HAART Income: | |||

| ≤ 6000 | 17 | 17 | 0.97 |

| 6001–12000 | 33 | 33 | 0.93 |

| 12001–18000 | 13 | 14 | 0.72 |

| 18001–24000 | 11 | 10 | 0.64 |

| 24001–30000 | 7 | 9 | 0.33 |

| > 30000 | 19 | 17 | 0.60 |

|

| |||

| Employed pre HAART | 38 | 43 | 0.25 |

| Married pre-HAART | 32 | 25 | 0.11 |

| Lived w kids baseline | 51 | 47 | 0.38 |

|

| |||

| Risky Behaviors Pre-HAART (Ever): | |||

| Used crack | 22 | 23 | 0.79 |

| Used pwd. cocaine | 17 | 21 | 0.34 |

| Used cocaine | 28 | 31 | 0.52 |

| Used stimulants | 28 | 31 | 0.52 |

| Used heroin | 18 | 16 | 0.50 |

|

| |||

| Symptoms Pre-HAART (Ever): | |||

| Memory problems | 31 | 36 | 0.22 |

| Numbness | 39 | 42 | 0.61 |

| Weight loss | 33 | 27 | 0.23 |

| Mental confusion | 17 | 20 | 0.50 |

| Night sweats | 35 | 41 | 0.22 |

|

| |||

| Ever Experienced Pre-HAART Domestic Violence: | |||

| Sex abuse | 5 | 10 | 0.09 |

| Physical abuse | 17 | 19 | 0.65 |

| Coercion | 26 | 28 | 0.59 |

| Domestic violence | 27 | 34 | 0.14 |

|

| |||

| Observations | 166 | 269 | |

| Person-Visits | 2477 | 4192 | |

The full sample includes all women from the first cohort who answered questions about domestic violence, employment, and illicit drug use, as well as all controls used. The treatment group is defined as having a minimum pre-HAART CD4 count between 300 and 399. High CD4 refers to minimum pre-HAART CD4 count greater than or equal to 400. Income is measured as yearly household income. Cocaine is defined as crack or powdered cocaine use. Stimulants are defined as crack, cocaine, (illicit) methadone, or methamphetamine. Domestic violence is defined as physical or sexual abuse or coercion by an intimate partner or spouse. Coercion indicates that the partner threatened to hurt or kill the subject or prevented her from: leaving or entering her home, seeing friends, making telephone calls, getting or keeping a job, continuing her education, or seeking medical attention. Column (3) shows p-values from the tests of differences in means between the treatment group and the control group.

1. Treatment vs Control Group

According to Table 1, treatment and control groups are quite similar in terms of demographics, including race and education, and pre-HAART characteristics such as risky behaviors, symptoms, and experience with violence. About 67% of the treatment group is black, 20% is Hispanic, and 12% is non-Hispanic white (henceforth simply white). This is roughly equivalent to the control group, where these percents are 64, 22, and 12 respectively. Our samples are also similar in terms of education: 30% of each group graduated high school, 22–23% attended some college, and 10% of the treatment group and 7% of the control group graduated college. Pre-HAART incomes are also comparable across groups. While the high CD4 count women were somewhat more likely to have been employed (43% vs 38%) and less likely to have been married prior to the introduction of HAART (32% vs 25%) we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the means are equal.

Overall rates of violence pre-HAART are similar across the treatment and control groups. In particular, 27% of the treatment group experienced domestic violence before the introduction of HAART compared to 34% of the women in the control group. Women in the control group were more likely to suffer sexual abuse, physical abuse, and coercion than our treatment subsample, but the only significantly different form of abuse is sexual abuse. Turning to illicit drug use, we find that, prior to the introduction of HAART, 28% of the treatment group had used cocaine, compared to 31% of women in the control group. Heroin use prior to HAART was very similar between the two groups: 18% for the treatment group and 16% for the control group. Mean differences in outcomes between the groups do not threaten the validity of using a difference-indifferences approach to estimating causal effects as long as the trends in domestic violence and other outcomes are similar. We discuss the parallel trends of our main outcomes in the following subsection.

2. External Validity

Our sample is quite similar to the statistics that the CDC reports about the HIV+ population of women living in the United States and, hence, is an appropriate starting point for studying links between health, domestic violence and illicit drug use. The majority of women in our sample are low-income, under-employed, and non-white— sociodemographic groups most likely to experience domestic violence and use illicit drugs. For example, it is estimated that of the total number of women living with diagnosed HIV, 61% are black (CDC, 2015), compared to about 65% for our sample. Additionally, in a sample of individuals living in high poverty areas, the CDC found that the likelihood of being HIV+ was negatively associated with completed education and income (Denning and DiNenno, 2010), which we also observe in our sample. Drug statistics for our sample are also more similar to those exhibited by HIV+ women than to U.S. women in general. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that about 16% of individuals who had been diagnosed with HIV reported using an intravenous drug in their lifetime, which is extremely close to the 17% reported by our sample.

Finally, in our main analyses, we present results separately for black women. The black women in our sample have, on average, less education than the white women. They also come from less well-off households: 49% had maximal pre-HAART incomes below $12,000 compared to 25% of white women. Black women are more likely than white women to report domestic violence. Lifetime prevalence of rape, physical violence, and/or stalking are estimated to be 43.7% for black women and 34.6% for white women (Black et al., 2011). Black women also suffer domestic violence at higher rates than the white women in our sample: 30% of black women reported experiencing domestic violence between one year prior to the start of the survey and the introduction of HAART, compared to 23% of white women. Patterns of drug use by black women in our sample compared to other women are more nuanced. For example, 28% of black women reported having used cocaine (either crack or powdered) prior to the introduction of HAART, compared to 23% of white women. However, 12% of the black women in the sample reported having used heroin during this time period, compared to 17% of the white women.

D. Research Design and Internal Validity

In this section, we discuss the validity of our empirical approach to estimating causal effects. Identification using the difference-in-differences approach requires that the path of the outcome variables for the treatment group and the control group would not be systematically different in the absence of HAART introduction. Specifically, this means that the introduction of HAART should be the only factor that drove the treatment group to experience a change in an outcome variable, such as domestic violence, relative to the control group. To confirm this, we study pre-HAART trends in our outcome variables and show that they are not different for our treatment group and our control group.

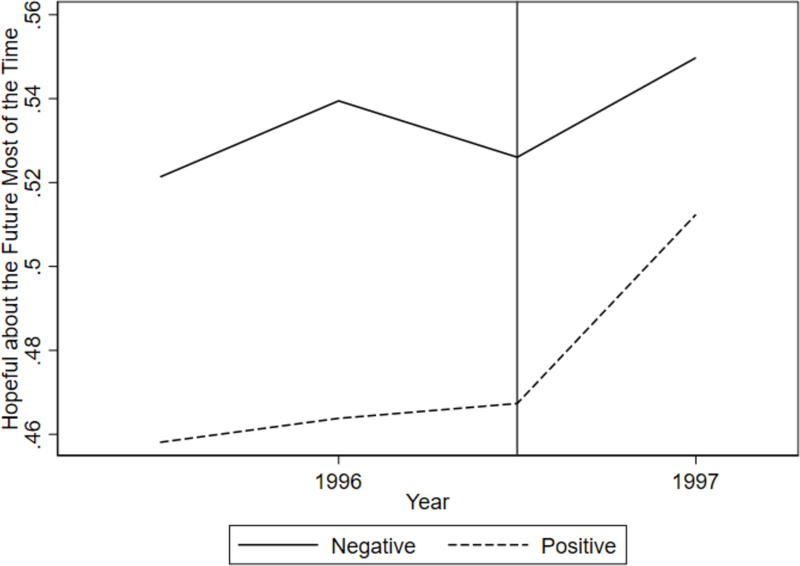

The validity of our research design relies on HAART being an unanticipated innovation. For evidence of this within our sample, we turn to questions used to compute the CES-D scale, which is used to assess whether women are likely to be depressed.27 One question asks whether respondents were hopeful about the future in the week leading up to their interview. We consider the probability that women in the sample answered “most or all of the time” to this question, and plot this before and after the introduction of HAART in Figure 1. There are two reasons why this figure suggests that HAART was not anticipated. First, before the introduction of HAART, the percentage of HIV+ women who reported being hopeful was relatively flat. They experienced a jump in hopefulness right at the introduction of HAART. If they had anticipated HAART, they might not have reported a jump in hopefulness coinciding with HAART introduction. Second, HIV– women did not experience such a jump. If some other factor drove the increase in hopefulness, then this would be reflected by a jump in the hopefulness of HIV– women.

Figure 1:

This figure shows the probability of reporting being hopeful about the future most of the time the week before the visit for HIV+ and HIV− women.

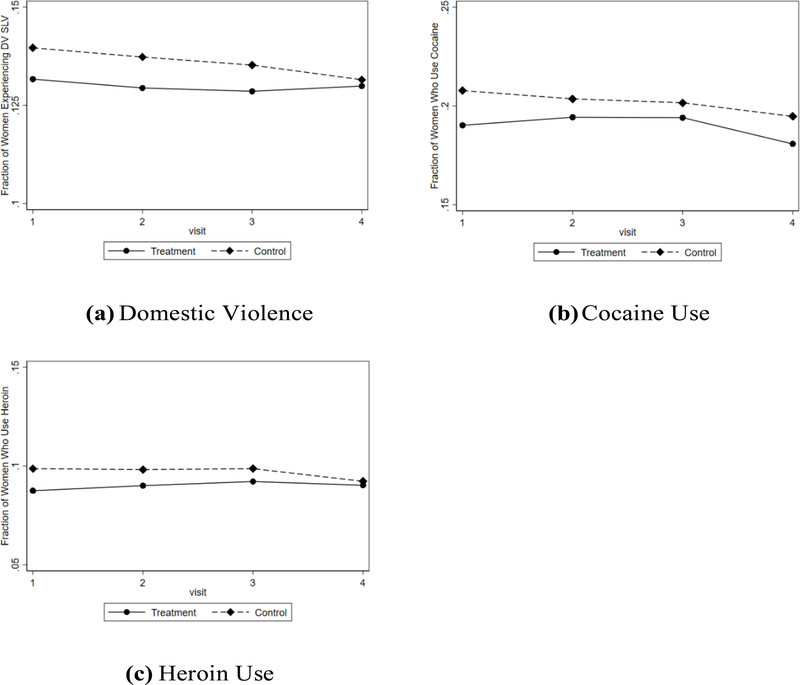

Next, we discuss pre-HAART trends among our treatment and control group. In Figure 2, we plot the pre-HAART trends in domestic violence (Panel 2a), cocaine use (Panel 2b), and heroin use (Panel 2c) for the treatment group and the control group. The plots show that trends for the treatment group and the control group were comparable prior to the introduction of HAART, which suggests that HAART is the driving force in the difference in outcomes. We also exploit the fact that we have multiple periods prior to the introduction of HAART to conduct a formal test of whether there are differences in trends between the treatment and control groups. For each outcome, we estimate the following probit models:

| (1) |

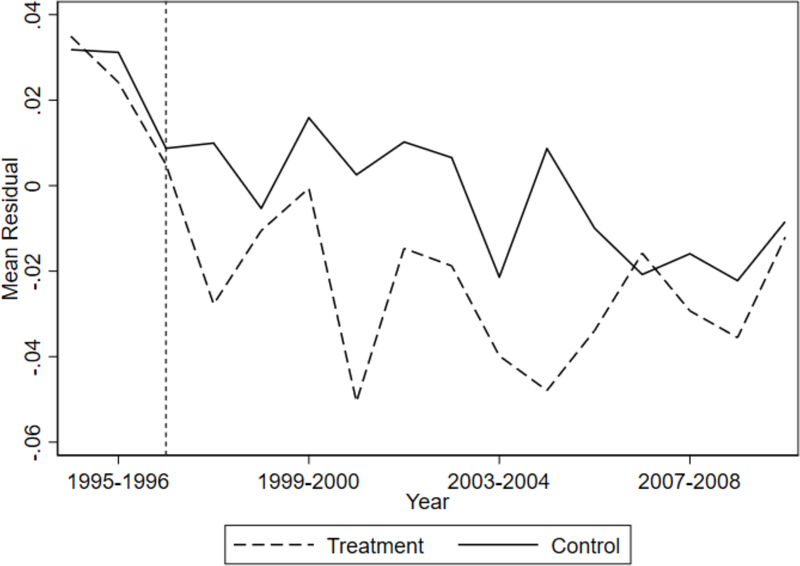

where Oit+1 is the outcome of interest (domestic violence, cocaine use, or heroin use) and Dt is an indicator for the date of visit bin such that D0 is the last period before HAART was introduced. Each bin is a six month period, and HAART is not available in the bins −3 through 0. Xit is a vector of controls, including age at visit, age squared, indicators for race, and indicators for site of visit. For each model, we test for pairwise parallel pre-HAART trends. Specifically, we test the null hypothesis that coefficients γ−3 through γ0 are equal. This essentially tests whether the trends in outcomes prior to HAART are parallel. In Table 2, we show that we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the coefficients are equal for both domestic violence and heroin use, suggesting that there is no difference in pre-HAART trends for these outcomes. For cocaine use, we estimate a p-value of 0.091, which is a borderline significant value. This suggests possible mean reversion, which could lead to an over-estimation of causal effects, so we must interpret our cocaine estimates with caution. Additionally, we test whether the pre-treatment trends in domestic violence, cocaine use, and heroin use are not jointly significant, and fail to reject the null hypothesis that there is no difference in trends (p=0.148). As we explain below, the p-value is 0.19 when we account for differences in observables using inverse probability weighting. In a related exercise, we plot the residuals from a probit model that regresses domestic violence on age, age squared, age cubed, race dummies, and site dummies. As shown in Figure 3, there is a clear break between the treatment group and the control group after the introduction of HAART, indicating that the introduction of HAART affected the two groups differently.

Figure 2:

This figure shows pre-HAART trends in outcomes.

Table 2:

Test of Equality of Pre-HAART Trends

| Outcome | p-value |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Domestic violence | 0.258 |

| Cocaine use | 0.091 |

| Heroin use | 0.307 |

|

| |

| Joint significance | 0.147 |

This table shows the p-values from tests that the pre-HAART trends in outcomes are parallel. For each outcome, we regress the outcome on age, age squared, race indicators, site of visit indicators, six-month time dummies, an indicator for being in the treatment group, and an interaction of the time bins and the treatment group. We then test that the pre-HAART interactions are zero.

Figure 3:

This figure shows residuals for the treatment group and the control group from a probit model of experiencing domestic violence, controlling for age, age squared, age cubed, race and site dummies.

We also conduct an event study to investigate whether pre-HAART trends are driving our results. Figure A1 in Appendix A shows the coefficient of the interaction for the periods before and after the introduction of HAART. Because there are so many more periods after HAART was introduced than before (16 versus 4 for domestic violence), we combine the post-HAART periods in this exercise. Periods prior to HAART introduction are one year in length, and periods after HAART was introduced are five years. For each outcome, we expect that coefficients on dummies for periods −2 and −1 (the periods prior to HAART) should not be significant and negative, because if they were, then declines in violence or drug use for the treatment group would have begun prior to the introduction of HAART. For domestic violence and heroin use, we find no difference in pre-HAART trends between the treatment group and the control group. For cocaine use, we find that the treatment group did exhibit a rising trend (relative to the control group) prior to HAART. This rise, however, is opposite to the direction we observe after HAART, which is reassuring because it suggests that post-HAART changes are not driven by trends beginning prior to HAART.

Finally, we discuss two additional concerns that might threaten the validity of our research design. First, one might be worried that another shift (e.g., a government program or policy change) had an impact on the treatment group, but not on the control group (or vice-versa). An obvious candidate is the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), which reformed welfare and was signed into law in August of 1996, just as HAART was introduced. However, given that the treatment and control groups have similar sociodemographic characteristics, including income and education, it is unlikely that welfare reform affected the control group differently than the education group.28 A second concern might be that domestic violence is drastically under-reported. By some measures, 50% of violent episodes go unreported (Greenfeld et al., 1998). However, this would affect our results only if there were a shift in under-reporting that differentially affected the treatment group and the control group and, moreover, if this shift coincided with the introduction of HAART. Though we cannot rule out this possibility, we believe that it is unlikely.

IV. Main Results

In this section, we present our main results. We show that the treatment group experienced reductions in domestic violence and illicit drug use that the control group did not. We also perform several robustness checks.

A. Expected Health and Domestic Violence

To test if the treatment group experienced a reduction in domestic violence after the introduction of HAART, we use a difference-in-differences approach. We estimate probit models where the dependent variable is an indicator of whether a woman experienced domestic violence since her last visit using the following specification:

| (2) |

where Vit+1 indicates if the woman reported violence at t + 1, which she experienced between periods t and t + 1. HAARTt is an indicator variable for HAART being available at time t.29 Treatmenti is a dummy variable indicating if the woman is in the treatment group and Xit is a vector of individual i’s characteristics at time t and includes basic controls: age, age squared, and age cubed at time t, as well as indicator variables for race and site of study.30 The coefficient of interest is γ, which indicates if the treatment group responded differently to the introduction of HAART than the control group. To control for serial correlation, all specifications are clustered at the individual level (Bertrand et al., 2004).

We report findings in two tables. Table 3 shows the estimated coefficients from the probit models, while Table 4 presents the marginal effects of the interaction term, which is the parameter of interest. We follow Puhani (2012) in calculating marginal effects of the interaction term.31 In each table, findings for domestic violence are shown in the first two columns. We show two specifications for both our main sample and the sample consisting of only black women. Column 1 (and all odd columns) includes the interaction but no other controls, and Column 2 (even columns) includes the basic controls described above.

Table 3:

Health, Violence and Drug Use, Probit Coefficients

| Domestic Violence | Cocaine Use | Heroin Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | [5] | [6] | |

|

| ||||||

| Full Sample | ||||||

| HAART available | −0.365*** | −0.235*** | −0.203*** | −0.304*** | −0.163*** | −0.273*** |

| (0.075) | (0.085) | (0.052) | (0.058) | (0.058) | (0.068) | |

| Treatment Group | −0.061 | −0.023 | 0.043 | 0.071 | 0.091 | 0.122 |

| (0.116) | (0.116) | (0.098) | (0.099) | (0.113) | (0.114) | |

| Treatment × HAART | −0.202* | −0.213* | −0.171** | −0.129 | −0.276*** | −0.242** |

| (0.117) | (0.121) | (0.080) | (0.084) | (0.098) | (0.104) | |

| Obs. | 6669 | 6669 | 16265 | 16265 | 16261 | 16261 |

|

| ||||||

| Black Sample | ||||||

| HAART available | −0.411 *** | −0.315*** | −0.246*** | −0.361*** | −0.177** | −0.396*** |

| (0.092) | (0.098) | (0.068) | (0.073) | (0.081) | (0.085) | |

| Treatment Group | −0.004 | 0.041 | 0.085 | 0.150 | 0.086 | 0.126 |

| (0.140) | (0.141) | (0.126) | (0.129) | (0.147) | (0.155) | |

| Treatment × HAART | −0.273* | −0.291** | −0.165 | −0.135 | −0.267* | −0.193 |

| (0.145) | (0.148) | (0.105) | (0.109) | (0.139) | (0.147) | |

|

| ||||||

| Obs. | 4280 | 4280 | 9355 | 9355 | 9352 | 9352 |

| Basic Controls | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

This table shows difference-in-differences probit model estimates where the outcome variable is having experienced domestic violence, used cocaine, or used heroin since the last visit. Basic controls include age at visit, age squared, age cubed, race (Caucasian omitted), and site of visit (Chicago omitted). In all specifications, errors are clustered at the individual level.

Table 4:

Health, Violence and Drug Use, Marginal Effects

| Domestic Violence | Cocaine Use | Heroin Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | [5] | [6] | |

|

| ||||||

| Full Sample | ||||||

| Treatment × HAART | −0.015* | −0.017* | −0.029** | −0.022 | −0.022*** | −0.019** |

| (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.007) | (0.008) | |

| 0.068 | 0.063 | 0.027 | 0.109 | 0.003 | 0.011 | |

| Obs. | 6669 | 6669 | 16265 | 16265 | 16261 | 16261 |

|

| ||||||

| Pre-HAART | ||||||

| treatment group mean | 0.103 | 0.103 | 0.178 | 0.178 | 0.087 | 0.087 |

| Mean | 0.063 | 0.063 | 0.121 | 0.121 | 0.052 | 0.052 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.026 | 0.059 | 0.006 | 0.065 | 0.009 | 0.090 |

|

| ||||||

| Black Sample | ||||||

| Treatment × HAART | −0.021** | −0.024** | −0.034 | −0.028 | −0.022** | −0.016 |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.021) | (0.022) | (0.010) | (0.011) | |

| 0.044 | 0.034 | 0.103 | 0.201 | 0.037 | 0.151 | |

| Obs. | 4280 | 4280 | 9355 | 9355 | 9352 | 9352 |

|

| ||||||

| Pre-HAART | ||||||

| treatment group mean | 0.130 | 0.130 | 0.228 | 0.228 | 0.089 | 0.089 |

| Mean | 0.069 | 0.069 | 0.145 | 0.145 | 0.053 | 0.053 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.033 | 0.057 | 0.007 | 0.058 | 0.009 | 0.103 |

|

| ||||||

| Basic Controls | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

This table shows the marginal effects of the interaction term from the difference in difference probit models. Standard errors are presented in parenthesis, and p-values are found below. Basic controls include age at visit, age squared, age cubed, race (Caucasian omitted), and site of visit (Chicago omitted). In all specifications, errors are clustered at the individual level.

The first row of Table 3 shows that HAART availability is associated with a decline in domestic violence. This is consistent with secular declines in domestic violence during this time period (Catalano, 2012). Turning to difference-in-differences estimates, we find that the treatment group experienced a decrease in domestic violence that otherwise similar women in the control group did not. According to Table 4, which reports marginal effects, the relative decline was between 1.5–1.7 percentage points, depending on the specification. To put this number into context, if we divide it by the pre-HAART treatment group mean of 13% (shown in the table), it implies a 14–16% decline.32

When we restrict the sample to black women, we find similar results. Black women in the treatment group experienced a decline in domestic violence between 2.1–2.4 percentage points as compared to black women in the control group. This implies a decrease in violence of between 16 and 18%.33

In assessing the magnitude of these declines, it is difficult to find research that links medical innovation and domestic violence. Research on policy interventions have yielded mixed results. For example, Heaton (2012) finds that Sunday liquor laws have no effect on domestic violence, while Iyengar (2009) reports that mandatory domestic violence arrest laws actually lead to an increase in intimate partner homicides. More closely related to our study are changes to women’s earnings, both absolutely and relative to men’s. For example, Aizer (2010), shows that reductions in violence of about 9% are explained by a 20-year decline in the male-to-female wage gap. In a recent paper, Cesur and Sabia (2016) show that combat veterans are between three and six percentage points more likely to be violent than veterans who were not assigned to combat zones.34

B. Drug Use

Next, we analyze how the introduction of HAART affected use of cocaine and heroin. As with domestic violence, we estimate probit models of the following form:

| (3) |

where Bit+1 refers to individual i’s behavior (i.e., use of cocaine or heroin) reported at time t + 1. Again, HAARTt is an indicator for HAART availability at time t and Treatmenti indicates if individual i is in the treatment group. Xit includes the basic controls discussed above: age, age squared, age cubed, race and site indicators.

We find limited evidence that the treatment group decreased their use of cocaine compared to the control group. In Table 3 (Columns 3 and 4) we show probit coefficients and in Table 4 we show marginal effects from the interaction term γB from equation (3). We find that the interaction term is statistically significant only under the most basic specification. In this specification, we find a decrease in cocaine use of 2.9 percentage points, or about 16% starting from the pre-HAART treatment group mean of 17.8% Although γB is always negative when we restrict the sample to black women, we cannot rule out the possibility that there is no effect.

We find that the treatment group also decreased their use of heroin compared to the high CD4 count HIV+ women. The results, shown in Table 4 (Columns 5 and 6), are robust and the average effects are always significant at least at the 5% level. We find that heroin use decreased by 1.9–2.2 percentage points, or 22–25% when compared to the pre-HAART treatment group mean of 8.7%. However, when we restrict the sample to only include black women, we find that the decrease is only significant in the most basic specification.

Contextualizing our results is again challenging, in part because of the lack of findings on how policy affects drug use. The WIHS is very unusual in that it asks about illicit drug use over time. One related study, Corman et al. (2013), examines the effect of welfare reform on the drug use of women who are at risk of being on welfare. They find that self-reported illicit drug use in the past year (excluding marijuana) fell by about 18% after welfare reform, which changed work incentives for women.

C. Robustness Checks

In this section, we discuss two robustness checks. First, we test whether survival bias is driving our results. To do this, we restrict our sample to women who were in the study for at least 15 visits, which is about 7.5 years, and then repeat our main analyses using equations (2) and (3). Results are reported in Appendix Table A4, which shows marginal effects of our main findings with the restricted sample. We find that restricting the sample in this manner does not affect our results. If anything, our findings on drug use are stronger.35

The second robustness check that we perform uses propensity score matching. Following Imbens (2015), we construct normalized differences of our covariates in order to investigate the overlap between our treatment and control groups. To test whether baseline characteristics are similar between groups, Imbens (2015) suggests a rule of thumb that normalized differences be below 0.25. The majority of our coefficients are below 0.1, as shown in Appendix Table A5, which provides some evidence that the treatment and control group are comparable. Appendix Figure A2 shows that the propensity scores for the treatment group and the control group have substantial overlap.36 Looking at the figure, the average of the estimated propensity score is lower for the treatment group, which indicates that the two groups are not comparable, except after appropriate reweighing of the observations. We thus repeat our main analyses using inverse probability weights. Similar to our main specification checks, we jointly test that the pre-HAART trends in domestic violence, cocaine use, and heroin use are different and fail to reject the null hypothesis when using the inverse probability weights (p = 0.19). Thus, even when considering weighting by the inverse probability of being in the treatment group, there is little evidence that pre-HAART trends differed between the treatment and control groups. Turning to the main analysis, we find that there are no differences between the treatment group and the control group pre-HAART, as shown in Appendix Table A6. However, after the introduction of HAART, violence and heroin use fell for the treatment group compared to the control group. These findings are similar to those from our main difference-in-differences specifications.

V. Mechanisms

In this section, we further explore possible mechanisms explaining why HAART lowered domestic violence and illicit drug use. Section 5.1 considers the roles of both physical and mental health improvements. Section 5.2 examines the relationship between illicit drug use and violence. Section 5.3 studies potential HAART-induced improvements in labor market outcomes and whether they play a role in explaining our main estimates.

A. Physical and Mental Health Improvements

We begin by documenting that women in the treatment group experienced large increases in their immune system health (CD4 count) compared to our control group. In particular, in Table 5 we return to our difference-in-differences framework to show relative increases in CD4 count among women in the treatment group after HAART. This improvement in underlying health may have translated to improvements in how women felt after HAART, which might lead to declines in domestic violence or illicit drug use. In Table 6 (Columns 3 and 4), we assess whether women in the treatment group exhibit shifts relative to the control group in the probability of experiencing at least one symptom, where the symptoms we consider are: fever, memory problems, numbness, weight loss, mental confusion, and night sweats. We again return to the original difference-indifferences framework.37 We find little evidence of post-HAART relative declines in reporting at least one of these symptoms for women in the treatment group after HAART.38 This absence of changes in symptoms is not surprising since women in our sample are unlikely to have experienced symptoms attributable to HIV prior to HAART introduction.39

Table 5:

CD4 Count

| [1] | [2] | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Full Sample | ||

| HAART available | −79.940*** | −73.840*** |

| (12.824) | (13.338) | |

| Treatment Group | −252.501*** | −245.119*** |

| (14.061) | (14.442) | |

| Treatment × HAART | 137.740*** | 136.016*** |

| (21.814) | (21.613) | |

| Obs. | 6524 | 6524 |

|

| ||

| Pre-HAART treatment group mean | 424.4 | 424.2 |

| Mean | 560.1 | 560.1 |

| R2 | 0.069 | 0.090 |

|

| ||

| Black Sample | ||

| HAART available | −90.840*** | −85.041*** |

| (17.268) | (17.701) | |

| Treatment Group | −267.766*** | −265.419*** |

| (17.346) | (18.838) | |

| Treatment × HAART | 142.861*** | 139.667*** |

| (25.966) | (25.727) | |

| Obs. | 4189 | 4189 |

|

| ||

| Pre-HAART treatment group mean | 421.9 | 421.9 |

| Mean | 559.9 | 559.9 |

| R2 | 0.080 | 0.083 |

|

| ||

| Basic controls | N | Y |

This table shows estimates from OLS difference-in-differences models where the outcome variable is CD4 count. Basic controls include age at visit, age squared, age cubed, race (Caucasian omitted), and site of visit (Chicago omitted). In all specifications, errors are clustered at the individual level.

Table 6:

Depression Score and Symptoms

| CES-D Score | Any Symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | |

|

| ||||

| Full Sample | ||||

| HAART available | −2.734*** | −3.328*** | −0.017 | −0.080*** |

| (0.441) | (0.507) | (0.016) | (0.018) | |

| Treatment Group | −2.406*** | −2.507*** | −0.016 | −0.022 |

| (0.871) | (0.872) | (0.030) | (0.029) | |

| Treatment × HAART | 0.501 | 0.803 | 0.011 | 0.028 |

| (0.720) | (0.718) | (0.027) | (0.026) | |

| Obs. | 14324 | 14324 | 16765 | 16765 |

|

| ||||

| Pre-HAART treatment group mean | 16.55 | 16.55 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| Mean | 15.95 | 15.95 | 0.44 | 0.44 |

| R2 | 0.010 | 0.043 | 0.000 | 0.037 |

|

| ||||

| Black Sample | ||||

| HAART available | −3.478*** | −4.223*** | −0.004 | −0.068*** |

| (0.611) | (0.666) | (0.021) | (0.023) | |

| Treatment Group | −3.398*** | −3.074*** | 0.023 | 0.026 |

| (1.067) | (1.056) | (−.040) | (0.038) | |

| Treatment 00D7 HAART | 1.486 | 1.702* | −0.045 | −0.026 |

| (0.940) | (0.936) | (0.035) | (0.034) | |

| Obs. | 8205 | 8205 | 9608 | 9608 |

|

| ||||

| Pre-HAART treatment group mean | 15.97 | 15.97 | 0.48 | 0.48 |

| Mean | 15.69 | 15.69 | 0.44 | 0.44 |

| R2 | 0.014 | 0.053 | 0.001 | 0.050 |

|

| ||||

| Basic Controls | N | Y | N | Y |

This table shows estimates from OLS difference-in-differences models. The first outcome variable is CES-D Scale Score, where higher values mean depression is more likely. The second outcome is having any symptom (fever, memory problem, numbness, weight loss, mental confusion, or night sweats). Results for having any symptom are robust to a probit specification, and available upon request. Basic controls include age at visit, age squared, age cubed, race (Caucasian omitted), and site of visit (Chicago omitted). In all specifications, errors are clustered at the individual level.

These results suggest that improvements in how women feel, measured by a lack of physical symptoms, do not appear to be an important mechanism generating our main results.40 Instead, HAART is an example of a medical innovation that affected the behavior of asymptomatic individuals. Recall, women in the treatment group, despite lower CD4 counts at the time of HAART introduction, had yet to experience the symptoms of AIDS. Hence, HAART-induced reductions in domestic violence and illicit drug use do not appear to be driven by contemporaneous improvements in how they feel as measured by physical symptoms. Instead, our findings on symptoms suggest that much of the role of HAART in affecting violence and drug use operated through its effect on expectations of future physical health and survival.

Another possible mechanism is mental health. It might be the case that a positive shock in expected health that increases expected longevity leads to better mental health. If so, women may be better able to cope with the difficulties of leaving violent partnerships or be more likely to avoid illicit drug use.41 In Table 6 (Columns 1 and 2), we use the same difference-in-differences framework as in our main analysis to study depression as the outcome variable. To measure depression, we use the CES-D Score and find little evidence that mental health can explain the links between HAART introduction and domestic violence or illicit drug use.42 Again, our results suggest that contemporaneous changes to physical or mental health after HAART do not explain the impact of HAART on violence and drug use.

B. Relating Drug Use and Violence

Our finding that HAART reduced both violence and drug use is consistent with several possible mechanisms. One possibility is that HAART affected both independently. Another is that HAART only affected violence through its impact on drug use. Alternatively, HAART may have reduced violence, leading women to avoid drugs, perhaps experiencing less need for drugs to cope with violence. Although it is difficult to distinguish between these possibilities given available data, we believe that we can make some progress on the question.

First, we allow violence and drug use to be jointly determined. In effect, doing so controls for the correlation between violence and drug use. We show that our basic results are qualitatively similar even when we control for this correlation.43 In particular, even when we control for the correlation between the two outcomes, HAART appears to have independent effects on domestic violence and illicit drug use. In other words, neither one is simply a by-product of the other.44

Second, we exploit the fact that heroin and cocaine appear to have different relationships with abuse. In Table 7, we present results from a regression of violence on drug use, income, employment, and our usual set of controls. We instrument heroin and cocaine use with previous period drug use in order to avoid capturing drug use as a response to domestic violence (e.g., using drugs as a coping mechanism.) Importantly, we distinguish between heroin use and cocaine use. We find that, whereas use of cocaine is associated with more violence, use of heroin is associated with less violence. This result is consistent with the medical literature that studies the impact of drug use on violence and finds that heroin has a pacifying or sedating effect on users.45 The negative coefficient on heroin use strengthens the argument that HAART had independent effects on both violence and drug use. The reasoning is as follows. Suppose HAART only affected heroin use and had no impact on violence except through its correlation with heroin use. Then, we might expect violence to rise if heroin use went down. Instead, both decline. Though this evidence is somewhat speculative, these empirical patterns are consistent with the claim that HAART had independent effects on violence and illicit drug use.

Table 7:

Drug Use and Violence

| [1] | [2] | [3] | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Heroin use | −0.143*** | −0.141*** | −0.143*** |

| Cocaine use | 0.144*** | 0.142*** | 0.119*** |

| Age | −0.010 | −0.010 | −0.009 |

| Age squared | 0.00004 | 0.00005 | 0.00004 |

| Age cubed | 1.62e–07 | 1.54e–07 | 1.86e–07 |

| Yearly income 6001–12000 | . | −0.007 | −0.007 |

| Yearly income 12001–18000 | . | −0.009 | −0.009 |

| Yearly income 18001–24000 | . | −0.005 | −0.004 |

| Yearly income 24001–30000 | . | −0.015 | −0.015 |

| Yearly income > 30000 | . | 0.0001 | 0.0005 |

| Employed | . | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Yearly income 6001–12000, employed | . | −0.002 | −0.002 |

| Yearly income 12001–18000, employed | . | −0.002 | −0.002 |

| Yearly income 18001–24000, employed | . | −0.019 | −0.020 |

| Yearly income 24001–30000, employed | . | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| Yearly income > 30000, employed | . | −0.006 | −0.006 |

| Married | . | .0014* | 0.014* |

| Not married, lives with partner | . | 0.020*** | 0.020*** |

| Widowed | . | −0.012 | −0.012 |

| Divorced/Annulled | . | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| Separated | . | 0.009 | 0.008 |

| Other Marital Status | . | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| Used marijuana SLV | . | . | 0.018*** |

| Never smoker | . | . | 0.031 |

| Current smoker | . | . | 0.011 |

| Light (lt 3 drinks/wk) | . | . | −0.003 |

| Moderate (3–13 drinks/wk) | . | . | 0.005 |

| Heavier (gt 13 drinks/wk) | . | . | 0.026** |

| No. male sex partner SLV | . | . | 0.00005 |

| Obs. | 17906 | 17906 | 17906 |

| Mean | 0.056 | 0.056 | 0.056 |

This table shows estimates from regressions of violence on illicit drug use. The sample is restricted to women from the first cohort who answered questions about domestic violence, which is defined in Table 1. Each specification uses individual level fixed effects. SLV means “since last visit.”

C. Employment and Income

Lastly, we consider changes to labor market outcomes induced by HAART. Our hypothesis is that improved labor market prospects might help to explain why women perceive better options outside of violent partnerships or face stronger incentives to desist from drug use. Further, evidence of HAART-induced improvements in labor market outcomes supports our treatment of health as a form of human capital.

To assess HAART-induced differences in labor market outcomes, we return to our difference-in-differences framework. We treat employment at the time of visit as the labor market outcome of interest. The marginal effects are presented in Table 8. Estimates show that the treatment group became relatively more likely to be employed after HAART. Black women in the treatment group became much more likely to be employed relative to black women in the control group for all of our specifications. This amounts to an increase in the probability of employment for the treatment group of about 4.8–5.5 percentage points, or about 19–22%, for the full sample and 7.7–8.1 percentage points, or about 35%, for the black women subsample. Pre-HAART treatment group means are 25.3% for the full sample and 22.3% for the black sample.

Table 8:

Employment, Marginal Effects

| [1] | [2] | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Full Sample | ||

| Treatment × HAART | 0.055* | 0.048* |

| (0.030) | (0.029) | |

| 0.065 | 0.099 | |

| Obs. | 16348 | 16348 |

|

| ||

| Pre-HAART treatment group mean |

0.253 | 0.253 |

| Mean | 0.335 | 0.335 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.002 | 0.060 |

|

| ||

| Black Sample | ||

| Treatment × HAART | 0.081* | 0.077* |

| (0.041) | (0.040) | |

| 0.051 | 0.054 | |

| Obs. | 9407 | 9407 |

|

| ||

| Pre-HAART treatment group mean | 0.223 | 0.223 |

| Mean | 0.316 | 0.316 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.003 | 0.058 |

|

| ||

| Basic controls | N | Y |

This table shows the marginal effects of the interaction term from the difference in differences probit models. The outcome of interest is being employed at the time of visit. Standard errors are presented in parenthesis, and p-values are found below. Basic controls include age at visit, age squared, age cubed, race (Caucasian omitted), and site of visit (Chicago omitted). In all specifications, errors are clustered at the individual level.

Our findings on employment are broadly consistent with those in Goldman and Bao (2004), who also study HAART and employment. They show that HAART use increased the probability that HIV+ individuals kept working by 37%. Our results are smaller for at least two reasons. First, we do not condition on HAART use as they do but instead rely on HAART introduction (similar to an intent-to-treat analysis). Second, their finding conditions on working at the time of HAART introduction while ours does not. Indeed, individuals in our sample are not highly educated and do not exhibit strong ties to the labor market before the introduction of HAART. Perhaps more comparable to our setting, Goldman and Bao (2004) find no effect of HAART on the likelihood of returning to work, conditional on not working prior to HAART introduction. Compared to their estimates for non-workers, our findings on employment are relatively large.46

VI. Conclusion

We have presented evidence that HAART lowered domestic violence by about 15% and reduced illicit drug use by 15–20% among a group of low-income, predominantly black, HIV+ women. To explain the findings, we argue that the unanticipated introduction of a new medical technology constituted a positive shock to women’s human capital in the form of increased expected health and longevity. This shock strengthened women’s incentives to make long-run investments, such as avoiding violence or reducing drug use. The fact that HAART marked a massive improvement over previous HIV treatments, together with the seriousness of HIV, enables us to detect subtle effects of this pharmaceutical innovation on domestic violence and illicit drug use.

How far our results generalize to other groups, to negative health shocks, to other chronic illnesses and to behaviors other than domestic violence and drug use are, of course, open questions. We have studied a particular population and a particular medical condition that is accompanied by stigma, depression and physical deterioration in ways that other chronic illnesses are not.

Nevertheless, we cannot resist speculating on the broader implications of our findings. Our results illustrate how the benefits of medical innovation are not limited to direct effects on health or survival, but can also work through changes in outlooks, expectations and behavior. Our results also suggest that policies that provide better access to health care and, more generally, enhance women’s human capital can alleviate persistent and intractable social problems. Policies surrounding both domestic violence and illicit drug use often utilize criminal sanctions and attempt to change attitudes; policies directed specifically at women also attempt to provide support for those who have been abused. Our findings suggest a complementary approach focused on interventions that increase women’s human capital.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge helpful comments from: Anna Aizer, Elizabeth Ananat, David Bishai, Christopher Carpenter, John Cawley, Ying Chen, Stefanie Deluca, Kathryn Edin, Emmanuel Garcia, Seth Gershenson, Ali Khan, Gizem Kosar, Giulia La Mattina, Robert Moffitt, Daniel Rees, Victor Ronda, Wayne Roy-Gayle, Todd Stinebrickner, Erdal Tekin and Matthew Wiswall along with undergraduate students from Papageorge’s 2019 course, “Sex, Drugs and Dynamic Optimization,” along with participants at the IZA’s 6th Annual Meeting on the Economics of Risky Behaviors, Royal Holloway, the 2014 North American Summer Meetings of the Econometric Society, the 2015 ASSA meetings, and the 2015 Southern Economics Association meetings. The usual caveats apply. Domestic violence data used in this project are restricted, but can be obtained through an application process approved by the WIHS Executive Committee. See https://statepi.jhsph.edu/wihs/wordpress/investigator-how-tos/#proposing. The corresponding author (Nicholas Papageorge) is willing to assist researchers in obtaining the data used in this project for the purposes of replication.

Footnotes

Further costs accrue through spillover effects in classrooms (Carrell and Hoekstra, 2010), intergenerational persistence (Pollak, 2004), emotional duress and compromised quality of life. The above estimate does not include costs to the justice system or social service and so $5.8 billion is probably a gross under-estimation of the true economic costs of domestic violence.

HIV stands for Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Without treatment, a newly infected HIV+ individual lives an average of 11 years. There is no vaccine or cure for HIV, but HAART is the current standard treatment. In general, 1996 is marked as the year when two crucial clinical guidelines that comprise HAART came to be commonly acknowledged. First, protease inhibitors (made widely available towards the end of 1995) would be an effective component of HIV treatment. Second, several anti-retroviral drugs taken simultaneously would vastly increases survival rates of HIV+ individuals. HAART transformed HIV infection from a lethal to a chronic condition (Yeni, 2006).

Zorza (1991) provides evidence that fleeing domestic abuse is a key cause of homelessness among women.

In 2014, there were almost one million individuals with HIV in the United States, and about 230,000 were women (CDC, 2015).

AIDS stands for Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome.

Because of the effectiveness of HAART and the severity of HIV, the take-up of HAART was quite fast. For our sample of HIV+ women, over 55% had taken HAART within two years of the introduction and over 70% had within three years.

An alternative approach would be to focus solely on women who actually use HAART, though medication choice is endogenous. In results available from the corresponding author, we show that HAART usage reduces violence if we use HAART introduction as an instrumental variable for HAART usage. One benefit of our approach is that we do not focus exclusively on users, so we can capture how introduction of HAART affected.

Given how we construct them, an alternative description of the treatment and control groups might be the “Sooner Potential Benefit Group” and the “Later Potential Benefit Group,” respectively. To avoid unnecessarily introducing new terminology, we use the terms “treatment” and “control” groups.

Indeed, women who were not infected with HIV, but who faced a high risk of infection, could have responded to HAART because it improved expected health and survival conditional on becoming HIV+.