SYNOPSIS

Objective.

The present study aimed to enhance understanding of continuity and stability of positive parenting of infants, across age and different settings in women with a history of depression who are at elevated risk for postpartum depression.

Design.

Mothers (N = 103) with a history of major depression and their infants were observed during 5-min play and feeding interactions when their infants were 3, 6, and 12 months of age. Summary scores representing mothers’ positive parenting were computed separately for each age and context based on ratings of five parenting behaviors. Mothers’ depressive symptom levels were assessed at each infant age.

Results.

Continuity (consistency of level) and stability (consistency of rank order) were assessed across age and context at both the group and individual level. Across-age analyses revealed continuity in the play context and discontinuity in the feeding context, albeit only at the group level, as well as weak to moderate stability. Across-context analyses revealed higher positive parenting scores in play than feeding at all time points as well as weak to moderate stability. Variations in positive parenting across age and context were independent of mothers’ postpartum depressive symptom levels.

Conclusions.

Findings based on normative samples may not generalize to women with a history of depression, who may benefit from interventions aimed at enhancing their positive parenting over the course of infancy, regardless of postpartum depressive symptom level. Results also underscore the importance of assessing parenting at multiple age points and across varying contexts.

Keywords: Parenting, Continuity, Stability, Depression

INTRODUCTION

As is widely understood, infancy is a sensitive period during which infants are highly dependent on and susceptible to the caregiving environment. Thus, it is not surprising that the quality of mothers’ interactions with their infants is strongly associated with their children’s later psychological development (Bornstein, 2019). In particular, mothers’ more positive interactions, also referred to as sensitive, responsive, and stimulating parenting of their infants, have been positively associated with children’s secure attachment (De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997), early achievement of language milestones (Nicely et al., 1999), and social-emotional and cognitive development generally (Landry et al., 2006; Page et al., 2010). Although negative interactions matter too (i.e., intrusive, harsh parenting), researchers find inconsistent support for associations between negative parenting and various child outcomes, in contrast to consistent support for associations between positive parenting and child outcomes (McFadden & Tamis-LeMonda, 2013). Further support for an emphasis on positive parenting comes from knowledge that a hallmark of depression, even relative to anxiety, is low positive mood (Watson et al., 1995). Thus, we focus on positive parenting.

Although much of the literature just cited is based on studies of parenting observed at one point in time and under one context, typically a play interaction, researchers have increasingly recognized the importance of studying parenting in terms of its consistency and change over time and across contexts (Bornstein et al., 2017; Bornstein et al., 2020). We build on this literature by addressing questions about mothers’ consistency and change in positive parenting in more than one context over the first year of their infant’s life and specifically among women at risk for depression, defining risk as a history of depression. We further build on this literature by examining consistency and change at the group level, as is typically done. We also consider consistency and change at the individual level, with the aim of providing additional information.

Compared to women without a history of depression, women with such a history are at greater relative risk of postpartum depression (Silverman et al., 2017). Indeed, most women with postpartum depression are found to also have been depressed during pregnancy (Heron et al., 2004). Whether or not they manifest depression during their infant’s first year, depression history is associated with vulnerabilities such as sensitivity to stress and reactivity to sad mood (Segal et al., 2006) and, specifically, with providing less optimal parenting regardless of current depression status (Lovejoy et al., 2000). A focus on women with a history of depression is further justified given the prevalence of depression among women with infants (Abel et al., 2019) and well-established associations between depression and both less positive parenting of infants (Field, 2010) and their children’s higher levels of psychopathology and other problems in development (Goodman & Halperin, 2020). Moreover, less positive parenting has been implicated as one mechanism through which depression in mothers may be related to adverse child outcomes (Goodman et al., 2020). Thus, it would be informative to explore consistency and change in positive parenting in a sample of mothers with a history of depression.

Two Ways of Tracking Consistency and Change in Development: Continuity and Stability

Within general population samples (not selected for risk of depression), researchers have studied two aspects of the consistency of parenting over time: continuity and stability (for more detailed discussion, see Bornstein et al., 2017; Holden & Miller, 1999). Continuity—the consistency of the average level of parenting over time—and stability—the consistency of an individual’s rank order within a group over time—each provides unique insights into the developmental course of parenting. Evaluating the continuity of parenting over time allows for an understanding of the variation in parenting, exploring whether, on average across individuals, certain aspects of parenting increase, decrease, or remain constant over time (Bornstein et al., 2017). By contrast, evaluating whether mothers maintain their relative rank within a sample over the child’s infancy is critical to understanding the extent to which individual mothers who show parenting deficits relative to others early in infancy continue to show those relative deficits later in infancy (Bornstein et al., 2020).

The same two aspects apply when considering the consistency of parenting across contexts: continuity, the consistency of the level of parenting across contexts, and stability, the consistency of an individual’s rank order within a group across contexts. For contexts, continuity addresses whether the level of parenting in mothers remains constant across contexts or whether particular contexts are associated with elevated (or diminished) levels of certain parenting. In contrast, stability provides insight into the question of whether mothers who show strengths or weaknesses in parenting in one context are also likely to show those same strengths or weaknesses in another context—for example, when playing with their infant or during feeding, the two contexts that we explore here.

Continuity (relative to discontinuity) is typically analyzed by testing for differences in group means across age or context (e.g., paired-samples t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test for two measures, repeated-measures analysis of variance [ANOVA] or Friedman’s ANOVA by ranks for three or more measures), whereas stability (relative to instability) is typically analyzed using correlations (e.g., Pearson’s r, Spearman’s ρ, β; Bornstein et al., 2017). However, as Bornstein and colleagues (2017) have commented, interpretation of such group-level statistical approaches can be problematic. Both continuity and instability predict small or near-zero differences or correlations, effects that are likely not statistically significant—which, given that sample sizes vary, highlights the importance of reporting and emphasizing the magnitude of the effects (Bakeman, 2006; Wilkinson & Inference, 1999).

Moreover, the typical group-level analytic approaches, because they provide evidence of consistency at the group level, fail to provide information about individual cases. Doing so, as we demonstrate here, can be informative both for theory and practice.

Continuity of Parenting in Relation to Depression

Across Age.

We turn now to the literature on mothers’ depression in relation to continuity and stability of their parenting of their infants. We found only a few published studies that took depression in mothers into consideration regarding the consistency of parenting during infancy, most of which examined across-age continuity (we discuss the studies of across-age stability in a later section). In those studies, one which measured depression diagnostic status and the others of which measured depressive symptom level, results were mixed as to whether depression was associated with parenting continuity over time. That is, in one study (Campbell et al., 1995), positive parenting increased over the course of infants’ first year of life, independent of mothers’ depression diagnostic status or context (face-to-face, play, or feeding interactions). In another study (Mills-Koonce et al., 2008), more elevated depression symptom levels were associated with decreases in sensitivity during play over time, but only for mothers of infants who were later found to have disorganized attachment. Mothers with elevated depression and securely attached infants showed the same increases in sensitivity over time as mothers with no depression. In a third study (Campbell et al., 2007), sensitivity during play decreased over infancy only for women with chronic depressive symptoms and remained stable for the group whose depression was moderately increasing, both of which were small subgroups; for all other women, sensitivity increased. Thus, findings across these three studies, other than small subgroups associated with children’s disorganized attachment or mothers’ chronic or worsening depression trajectory, are in line with findings from studies in which the general population was sampled, with parenting during a face-to face play interaction showing a small to moderate tendency to become more positive over the course of infancy (Cox et al., 2004; Dallaire & Weinraub, 2005). Only Campbell et al. (1995) reported data on feeding, with parenting during feeding showing no significant changes over time during infancy. Further, it should be noted that Mills-Koonce et al. (2008), Cox et al. (2004), Dallaire and Weinraub (2005), and Campbell et al. (2007) all relied on the NICHD Study of Early Child Care, which, despite the numerous strengths of the study, imposes some constraints on drawing conclusions given sampling of the general population and the same sample providing data for all these publications.

In summary, there is some support for patterns of change in parenting across infancy being independent of depressive diagnosis or symptomatology level other than for extreme groups. In the current study, we build on these findings by examining parenting continuity in women at elevated risk for perinatal depression (in relation to their history of depression). In addition to selecting women at elevated risk being highly justified, as noted above, and given differences found in the positive parenting of a community sample with elevated depression symptoms (e.g. Campbell et al., 1995), questions arise as to whether findings from community samples can be generalized to a high-risk population. Because a history of depression often predicts postpartum depression—which suggests that many women with depression in the postpartum have been depressed in the past—it is important to characterize positive parenting in this group with recurrent depression (Campbell et al., 1995). With this in mind—and consistent with the literature on both depressed and non-depressed samples—we hypothesized that across the first year of their infant’s life women at elevated risk for postpartum depression would demonstrate discontinuity in the level of positive parenting during play but continuity during feeding (Hypothesis 1). We considered the feeding hypothesis to be more tentative given the reliance on a single small study.

Across Context.

We found only one published study that addressed depression in mothers regarding across-context continuity of parenting infants, albeit only indirectly. Seifer and colleagues (1992) compared naturalistically occurring interactions with 4- and 12-month-old infants by mothers with psychopathology (about one-third had depression; others had schizophrenia or personality disorders) with controls. They found that context and mental illness severity interacted, such that being severely mentally ill was associated with the lowest level of maternal responsiveness during a context in which mothers were close to the infant but not engaging in feeding or caregiving behaviors, as compared to a feeding or caregiving context, particularly with 4-month-old infants. Overall, this study supports the conclusion that mental illness, albeit not depression specifically, is associated with mothers’ positive parenting of their infant having less across-context continuity relative to women with no mental illness.

We build on this finding by focusing on depression and examining potential differences in quality of positive parenting across common parenting tasks, specifically feeding and play. Common parental contexts may be especially differentiated for depressed women’s quality of positive parenting, as playing with an infant imposes more social demands on mothers than feeding an infant and may thus be more influenced by depression. To this end, we hypothesized that the level of positive parenting would differ between play and feeding (i.e., demonstrate discontinuity; Hypothesis 2).

Stability of Positive Parenting Across Time and Across Context

We found only one published study that considered women’s depression regarding across-time stability and none on across-context stability of parenting. In terms of the one study on across-time stability, Murray, Halligan, Goodyer, and Herbert (2010) examined postnatally depressed and well mothers and found a moderate degree of stability from 2 to 9 months for positive parenting in a play context. With regard to across-context stability, given that we found no studies that considered women’s depression, we relied on studies of positive parenting in the general population, which have found moderate to strong stability across common parenting contexts such as play, diaper change, and bath time in infancy (Maas et al., 2013; Masur & Turner, 2001). To this end, we expected that the rank order of positive parenting would be stable across the first year of life and across play and feeding (Hypothesis 3).

Further support for Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 comes from knowledge that: (1) mothers’ depressive symptom levels tend to be stable across the first year postpartum (Beeghly et al., 2002; McCall-Hosenfeld et al., 2016); (2) even psychotherapy driven decreases in depression in mothers are associated with only a small change in parenting (Cuijpers et al., 2015); and (3) residual effects of prior depression are associated with current parenting quality (Lovejoy et al., 2000).

Change in Positive Parenting and Postpartum Depressive Symptom Severity

For the reasons discussed in the previous section, we expected that patterns of change in positive parenting across the first year of life would be independent of postpartum depressive symptom severity (Hypothesis 4), but that patterns of change across free play and feeding would be larger for mothers with more severe postpartum depressive symptomatology (Hypothesis 5).

This Study

Taken together, the literature on the consistency of mothers’ positive parenting quality with their infants leaves critical questions unanswered regarding the continuity and stability of positive parenting across age and context among women at risk for postpartum depression. We addressed these questions by testing five specific hypotheses:

The level of positive parenting will change across the first year of life during play (i.e., demonstrate discontinuity) but not during feeding (i.e., demonstrate continuity).

The level of positive parenting will differ between play and feeding (i.e., demonstrate discontinuity).

Positive parenting will demonstrate rank-order stability across the first year of life and across play and feeding.

Change in positive parenting across the first year of life will be independent of depressive symptom severity.

Differences between play and feeding will be larger for mothers with more severe depressive symptomatology at each age.

To address these hypotheses, we drew data from women who had experienced a major depressive episode prior to pregnancy and had participated in a longitudinal, prospective study of mothers’ parenting quality as observed during play and feeding interactions when their infants were 3, 6, and 12 months of age.

METHOD

Participants

For this report we selected 158 women and their infants from a larger project, Perinatal Stress and Gene Influences: Pathways to Infant Vulnerability, a prospective, longitudinal investigation of women at risk for perinatal depression due to previous mood difficulties (clinically significant depression and/or anxiety). Pregnant women were recruited from several sources, including a women’s mental health program in a university psychiatry department, local obstetrical and mental health practitioners, and media announcements. Women were eligible for this project if they were less than 16 weeks gestation based on their last menstrual period and between the ages of 18 and 45. At enrollment, lifetime history of depression diagnoses was assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis 1 Disorders (SCID; First et al., 1995). Women were excluded for exhibiting active suicidality or homicidality, having psychotic symptoms, meeting DSM‐IV criteria for bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, an active eating disorder, an active substance use disorder within 6 months before the last menstrual period, or a positive urine drug screen, and/or having an illness requiring treatment that could influence infant outcomes (e.g., epilepsy, asthma, autoimmune disorders, anemia, or abnormal thyroid stimulating hormone concentrations).

Other studies have drawn data from this project (Davis et al., 2019; Laurent et al., 2018; Lusby et al., 2016). Like Lusby et al., we began with the 234 mothers who had participated in one or more laboratory visits (selecting one infant randomly from each of 8 twin pairs). Crucially for this study, and like Davis et al., we then excluded 42 mothers who did not meet the inclusion criterion of lifetime Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) or Depressive Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (DD-NOS). Because this report concerns continuity, we also excluded an additional 34 dyads with data for only one of the three visits. This left us with a sample of 158, 103 of whom had complete data for all three visits and 55 who had data for two visits.

Mothers with complete versus incomplete data, respectively, were typically married (90% vs. 84%), European American (92% vs. 85%), educated (80% vs. 75% had completed 16 years of education), of similar socioeconomic status (mean Hollingshead Four-Factor Index scores were 51 vs. 50, SD = 8.1 vs. 10.3, which reflects broadly middle socioeconomic status; Hollingshead, 1975), and of similar age (33.6 vs. 34.1 years at delivery, SD = 4.2 vs. 4.7). Differences between the two groups were near zero or small. For marital status, ethnicity, and education, respectively, φs = .11, .06, and .10; ps = .18, .47, and .22 (thresholds for small, medium, and large correlations are .10, .30 and .50 absolute; Cohen, 1988). And for socioeconomic status and age, respectively, standardized mean differences (Cohen’s d) were 0.12 and 0.15, ps = .47 and .37 (thresholds for small, medium, and large ds are 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80; Cohen, 1988).

Procedures and Measures

Mother-Infant Interaction Tasks.

We invited mothers to participate in laboratory visits when their infants were 3, 6, and 12 months of age. Visits included several different tasks; two 5-min face-to-face interaction tasks, which occurred in a fixed order, are the focus of the current study. The first task, feeding, varied somewhat across infant ages. At 3 and 6 months, infants were either breastfed or bottle-fed in their mothers’ laps. At 12 months, mothers fed their infants in a highchair with a bottle, sippy cup, spoon, or finger food. During the second task, play, we gave mothers a standard set of age-appropriate toys, such as a truck, rattle, and a puppet, and asked them to engage with the infant as they normally would at home. At 3 and 6 months of age, for the play segment, infants sat in an infant seat on a table across from their mother and at 12 months infants sat in a highchair directly across from their mothers. All interactions were video recorded and later rated on the quality of parenting behaviors.

Rating Mother-Infant Interactions.

Trained research assistants rated mother-infant face-to-face interactions using standardized rating scales taken from Clark (1985) and Campbell and colleagues (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1999). The rating scales assess various aspects of parenting behaviors known to be associated with depression in mothers; each takes into consideration the quality and quantity or intensity of the measured behavior. Based on Lovejoy and colleagues’ (2000) criteria, we selected five items to use for this report to represent positive parenting: sensitivity/responsiveness to nondistress, positive regard for the child, warmth, quality of verbalizations, and structures and mediates environment. Two additional items, sensitivity to distress and stimulation of development, although they are indicative of positive parenting, were not included in the summary score because stimulation of development was not rated for the feeding segments and sensitivity to distress was missing for most infants, as many did not demonstrate distress during the 5-min interactions. Raters assigned scores separately for the play and feeding contexts at the three ages without knowledge of other information on mothers or babies.

To assess observer agreement, a second observer rated 22% of the videos, randomly selected, without observers’ awareness of which segments were selected for reliability checks. Raters agreed within 1 scale point 94% of the time or better for the five items. Weighted kappas were .68, .94, .78, .88, and .77, respectively. To produce kappas of this magnitude for these items, raters would need to be 92%, 98%, 94%, 95%, and 94% accurate, respectively (computed by the KappaAcc program; see Bakeman, 2018).

We computed a summary score representing mothers’ positive parenting. This summary score, computed for each context at each age, was the mean of sensitivity/responsiveness to nondistress, positive regard for the child, warmth, quality of verbalizations, and structures and mediates environment. Before computing, the first two items, which had been rated 1–4, were rescaled 1–5 to make them comparable to the last three 1–5 items. Cronbach’s alphas for the summary scores were .81, .86, and .84 at 3, 6, and 12 months for play and .93, .89, and .89 for feeding, respectively.

Coding Infant Positive Affect.

As an exploratory matter, a separate team of observers coded the same videorecorded play and feeding segments for infant affect using modified versions of Osofsky’s (1987) Global Affect Scales (as described in Dawson et al., 1999). We examined the total percentage of time that the infant was coded as displaying positive affect. For additional coding details see Davis et al. (2019).

Mothers’ Depressive Symptom Severity.

Mothers completed the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1997) when their infants were 3, 6, and 12 months old. The BDI-II, a self-report measure, consists of 21-items rated 0 – 3. Higher scores—the score is the sum of the items— indicate more severe depression (Beck et al., 1997; Ji et al., 2011). The mothers’ scores ranged from 0 to 42 with a median of 7 at all three visits; 20%, 24%, and 21% of women had scores of 14 or more at the 3-, 6-, and 12-month visits, respectively, indicating at least mild depression severity.

Analytic Plan

As mentioned previously, of the 158 dyads with mother behavior ratings for at least two of the three visits, only 103 had ratings for all three visits. Of the other 55, 29%, 9%, and 64% were missing data for the 3-, 6-, and 12-months visits, respectively. Consequently, 32% were missing data for the 3- to 6-month shift and 68% were missing data for the 6- to 12-month shift. Given this pattern of missing data, techniques that impute missing data did not seem warranted. The required assumption of data missing at random does not seem tenable, and statistics describing continuity and stability across age and context would be based on differing amounts of imputed data, complicating interpretation. Consequently, the analyses we report are based on the 103 dyads with complete data.

To assure ourselves that doing so would not produce dramatically different results, we ran analyses on the sample of 158 that allowed for missing data using Generalized Estimating Equations, SPSS Version 27. These analyses gave comparable p values as the analyses with 103 dyads, and their estimated means reflected the means computed for the smaller sample, suggesting that nothing substantive was lost by analyzing the sample without missing data. Additionally, differences between the two samples on key variables were small or near zero. Cohen’s ds at 3-, 6-, and 12-months for the BDI means and for parent positive behavior during play and during feeding, respectively, were: 0.26, 0.14, 0.27; ~0, 0.28, 0.28; and 0.07, 0.01, 0.13.; ps = .14, .41, .25; .99, .11, .24; and .69, .98, .58.

Throughout we report effect sizes, usually correlations and Cohen’s d. This is especially important for predictions of no effects, which would be supported by near-zero effects sizes.

RESULTS

Continuity Across Age and Context (Hypotheses 1 and 2)

Group-Level Continuity.

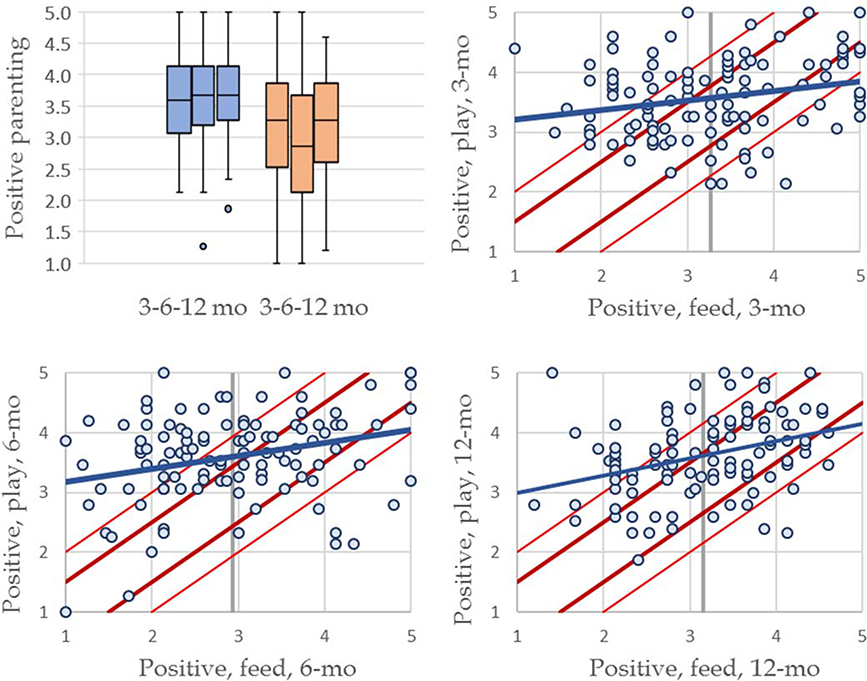

Figure 1 shows box-and-whisker plots for mean positive parenting ratings. These plots show that mean ratings were well distributed (only two extreme scores, one each during play at 6 and 12 months, standardized skews = 0.17–2.13) and suggest group-level continuity across age for feeding but not play, and group-level discontinuity across contexts.

Figure 1.

Box-and-whisker plots and across-context scattergrams for positive parenting, N = 103. For the box-and-whisker plots, the box includes scores from the 25th to the 75th percentile. The whiskers indicate the lowest and highest scores that are not extreme. Extreme scores, defined as scores greater than 1.5 times the interquartile range below the 25th or above the 75th percentile, are indicated with circles. For the scattergrams, the heavier parallel lines enclose cases whose score changed by no more than one-half point and the lighter lines enclose cases whose score changed by no more than one point (defined as continuity). Horizontal and vertical lines indicate group means. The heavy line is the best-fit line; its slope is b, the regression coefficient.

We anticipated that positive parenting would demonstrate discontinuity during play but continuity during feeding over the infant’s first year of life (Hypothesis 1) and discontinuity between play and feeding at each age (Hypothesis 2). Counter to Hypothesis 1, we found support for continuity of positive parenting during play and discontinuity of positive parenting during feeding across infant ages. Supporting Hypothesis 2, we found discontinuity across contexts. We employed paired-samples t-tests to examine these hypotheses, first comparing 3- to 6-month scores and 6- to 12-month scores (Hypothesis 1) and then play to feeding scores at 3, 6, and 12 months (Hypothesis 2). Across ages effect sizes for play were near zero, not even meeting the criterion for a small effect for Cohen’s dz and were not statistically significant. In contrast, effect sizes for feeding, although small, were statistically significant (see Table 1, group-level continuity, across age). Across contexts, means for positive parenting in the play context were higher than in the feeding context, moderately so at 3 months and strongly so at 6 and 12 months, all statistically significant (see Table 1, group-level continuity, across context). Likewise, the age effect from a repeated-measures ANOVAs was near-zero for play but small for feeding, η2G = .0011 and .023, ps = .77 and .003—see Bakeman (2005) and Olejnik and Algina (2003)—but we reported separate t-tests here for their greater descriptive value.

Table 1.

Statistics for group-level and individual continuity and stability of positive parenting across age and context.

| Across Age |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Play | Feeding | Across Context | |||||

|

|

|||||||

| Statistic | 3–6 mo | 6–12 mo | 3–6 mo | 6–12 mo | 3 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo |

|

| |||||||

| Group-level continuity | |||||||

| Cohen’s dz (p value) | 0.07 (.48) | 0.01 (.95) | 0.34 (.001) | 0.22 (.027) | 0.29 (.004) | 0.65 (<.001) | 0.53 (<.001) |

| Individual continuity | |||||||

| % change ≤ one pointa | 83 | 78 | 60 | 66 | 63 | 56 | 70 |

| z score (p value) | 7.93 (<.001) | 6.94 (<.001) | 3.36 (<.001) | 4.56 (<.001) | 3.96 (<.001) | 2.57 (.005) | 5.35 (<.001) |

| % change ≤ half pointb | 47 | 49 | 39 | 41 | 32 | 31 | 36 |

| z score (p value) | 5.55 (<.001) | 6.02 (<.001) | 3.69 (<.001) | 4.15 (<.001) | 2.06 (.020) | 1.83 (.034) | 2.99 (.001) |

| Group-level stability | |||||||

| Pearson r (p value) | .43 (<.001) | .27 (.006) | .48 (<.001) | .31 (.001) | .22 (.023) | .18 (.064) | .34 (<.001) |

| Spearman ρ (p value) | .35 (<.001) | .26 (.008) | .44 (<.001) | .31 (.002) | .24 (.016) | .16 (.096) | .36 (<.001) |

Note. N = 103. Group-level continuity dz and p values were determined by repeated-measures t-tests, group-level stability by correlation coefficients. Individual stability and continuity zscores and one-tailed p values were determined by binomial tests comparing the observed frequency to that expected by chance. Group-level continuity is supported by nonsignificant p values, whereas individual continuity (like group-level and individual stability) is supported by significant p values.

45 expected by chance; see text for details.

24 expected by chance; see text for details.

Individual-Level Continuity.

The results just reported tested Hypotheses 1 and 2 based on group-level continuity, as is typical, but did not consider individual-level continuity—and individual-level analyses need not necessarily support the same conclusion. True, if individuals’ scores changed little, thus showing continuity, the group-level finding—whether for continuity or discontinuity—would change little. But if individuals’ scores changed more, thus showing discontinuity, the group-level finding could be either continuity or discontinuity. Although done infrequently, describing individual-level continuity is warranted.

To describe individual-level continuity we considered scattergrams based on the positive parenting scores across age (Hypothesis 1; Figure 2) and context (Hypothesis 2; Figure 1). If we arbitrarily say that a shift of no more than half a scale point (or one scale point) represents continuity, we can compute the number of cases that shifted one half or less (or one or less)—recognizing that these cut points are arbitrary—and then state the number and percentage of cases that demonstrated continuity according to a specific criterion.

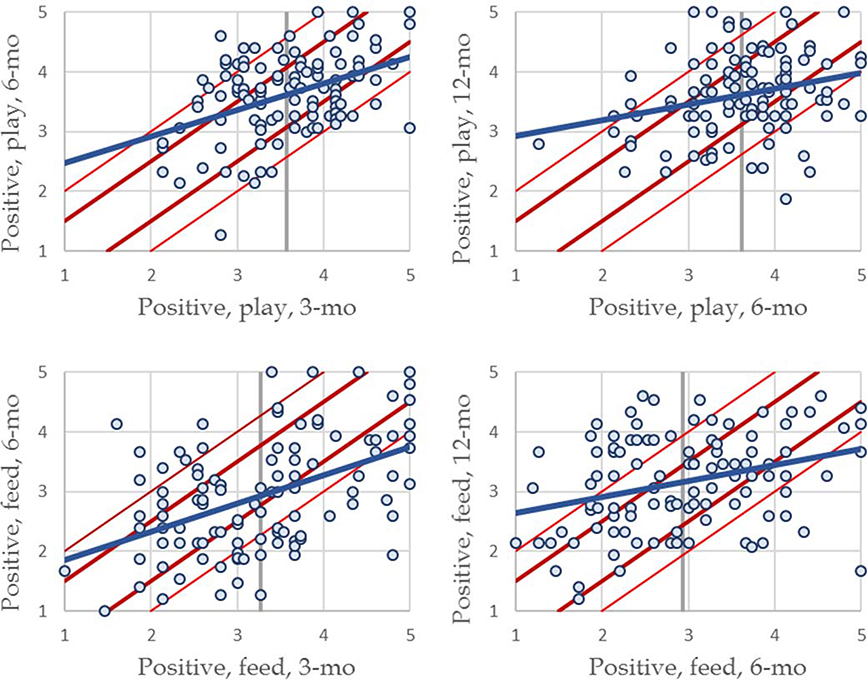

Figure 2.

Across-age scattergrams for positive parenting, N = 103. The heavier parallel lines enclose cases whose score changed by no more than one-half point and the lighter lines enclose cases whose score changed by no more than one point (defined as continuity). Horizontal and vertical lines indicate group means. The heavy line is the best-fit line; its slope is b, the regression coefficient.

We can also compare that number to the number that would fall within the specified range randomly in the absence of continuity. Because in our case scores are continuous, real numbers that vary from 1 to 5, the total scattergram (Figures 1 and 2) is 42 square units ([5 − 1]2). For the one-point criterion, the expected frequency of shifts of one or less by chance alone is 45—½ × 32 units would fall outside the thinner parallel lines at the upper left and lower right in the figures, thus the area within the parallel lines is (42 – 32) ÷ 42 or 44% (so 45 of 103). For the one-half-point criterion, the area within the thicker parallel lines is (42 – 3.52) ÷ 42 or 23% and the expected frequency of shifts no greater than one-half point by chance alone is 24.

Both across age (Hypothesis 1) and across context (Hypothesis 2) individual continuity was the rule. By chance we would have expected 44% of the mothers to show shifts no greater than one and 23% to show shifts no greater than half a point. In fact, actual percentages were greater, all significantly so except for context continuity at 6 months (see Table 1). Individual continuity was strongest for age shifts during play, somewhat less for age shifts during feeding and across context, with results generally somewhat weaker for the half-point than the one-point criterion.

We had predicted across-age discontinuity during play and continuity during feeding. As reported earlier, group-level analyses found the opposite. The individual analyses just reported agree with the group-level analyses for play, likewise finding continuity, but disagree with the group-level analyses for feeding, finding continuity as hypothesized. Examining the distribution of data points in Figure 2 explains the disagreement. For the 3–6 and 6–12 month age shifts for feeding, ratios for the number of mothers whose scores increased more than decreased by a scale point were 10:31 and 25:10. The differences reflect the decrease in the feeding group medians from 3–6 and the increase from 6–12 months (see Figure 1). Thus, the individual analysis adds information to the group-level one. It shows continuity at the individual level—more mothers than expected changed scores by no more than one scale point—but for those who did change, decreases were more likely from 3 to 6 months and increases were more likely from 6 to 12 months, resulting in the discontinuity in group means that we saw with the group-level analyses (results were similar for the half-point criterion).

Additionally, we had predicted discontinuity across contexts at all ages (Hypothesis 2), which, as reported earlier, was supported by group-level analyses. However, the individual analyses just reported disagree with the group-level analyses, finding continuity instead, thus not supporting the hypothesis. Examining the distribution of data points in Figure 2 explains this disagreement. For the shifts from feeding to play for the three ages, ratios for the number of mothers whose scores increased more than decreased by a scale point were 24:14, 39:6, and 27:4. These differences reflect the higher group medians for play than feeding (see Figure 1). Thus, the individual analysis adds information to the group-level one. It shows continuity at the individual level—more mothers than expected changed scores by no more than one scale point—but for those who did change, increases were more likely from feeding to play, resulting in higher group means for play (results were similar for the half-point criterion).

Stability Across Age and Context (Hypothesis 3)

Group-Level Stability.

We had anticipated that positive parenting would demonstrate stability over the first year of life and across different parenting contexts (Hypothesis 3). Supporting our hypothesis, we found weak to moderate support for stability across age and context. We assessed stability with correlations—specifically between 3- and 6-month and between 6- and 12-month scores for age and between play and feeding scores at 3, 6, and 12 months for context—computing correlations both for the positive parenting scores themselves (Pearson correlations) and for their ranks (Spearman rank-order correlations). All correlations were weak to moderate (see Table 1, group-level stability) and all were statistically significant with the exception of a marginally significant Spearman correlation (p = .096) across context at 6 months.

Individual-Level Stability.

The results just reported address group-level stability but do not address individual-level stability—although, unlike for continuity, the two generally go together. The definition of stability—that individual scores will be ordered approximately the same at one time or in one context as another—is inherently individual in a way that group-level continuity is not, and this is true whether group-level stability is assessed with the best-fit line for the raw scores (b, the regression coefficient), the standardized scores (r, the Pearson correlation coefficient), or their ranks (ρ, the Spearman correlation). Moreover, individual stability implies individual continuity and vice versa. If individuals demonstrate individual continuity—if their ranks or scores tend to change little—they will necessarily demonstrate rank-order stability.

Consider Figures 1 and 2. The slopes of the best-fit lines, as well as the related statistics r and ρ, gauge group-level stability, as just discussed, but do not provide information about individual cases—that is what the individual points do. The individual points show individual shifts. If there were no individual-level continuity and so no stability, the points would be scattered, and the slopes of the best-fit lines would be near zero. But if there were perfect individual-level continuity and so perfect stability, all points would fall on the diagonal lower-left to upper-right line. As a descriptive matter, points that fall near this diagonal (whatever criterion is used) represent both individual continuity (as discussed previously) as well as individual stability. Thus, the descriptive results given previously for individual continuity apply to individual stability as well; that is, we found support for Hypothesis 3 with both group-level and individual-level approaches to analyses. These results were based on changes in raw scores. When we applied the same procedures to ranks instead of raw scores, results were essentially the same.

Postpartum Depressive Symptoms and Change Across Age and Context (Hypotheses 4 and 5)

We had anticipated that change in positive parenting across the first year of life would be independent of depressive symptom severity (Hypothesis 4), but that differences between play and feeding would be larger for mothers with more severe depressive symptomatology (Hypothesis 5). We found support for Hypothesis 4. Employing multiple regression, we asked whether change in positive parenting from 3- to 6-months could be predicted from 3- and 6-month BDI-II scores and whether change in positive parenting from 6- to 12-months could be predicted from 6- and 12-month BDI-II scores. Only one effect was even marginal—b = .22, p = .07, for the association between the 6-month BDI-II score and change from 6- to 12-months during feeding; other effects were barely small or near zero (b = .006 to .11) with p values ranging from .44 to .96.

We failed to find support for Hypothesis 5. We asked whether differences between play and feeding at each age were correlated with the concurrent BDI score. Effects were just barely small or near zero (r = .04 to .13) with p values ranging from .21 to .72. (Note: six 6-month and three 12-month BDI-II scores were missing.)

Infant Positive Affect

As an exploratory matter, and absent any specific hypothesis, it seems possible that the stability and continuity of parent positive behavior could be affected by their child’s behavior as mothers respond in the momentary context of the interaction. We coded the percentage of time during the interaction that infants displayed positive affect and, as with depressive symptoms, found little support for any effects of infant positive affect. For age, again employing multiple regression, we asked whether change from 3- to 6-months could be predicted from 3- and 6-month infant positive affect and whether change from 6- to 12-months could be predicted from 6- and 12-month infant positive affect. Only two effects were even marginal—b = .17, p = .09, for the association between 3-month infant positive affect and change from 3- to 6-months during play and b = .19, p = .05, for the association between 12-month infant positive affect and change from 6- to 12-months during feeding. Other effects were just barely small or near zero with p values ranging from .20 to .91. For context, we asked whether differences between play and feeding at each age were correlated with concurrent infant affect for play and feeding. One effect was marginal—b =.20, p = .05, for the association between 12-month infant positive affect during feeding and the difference between 12-month play and feeding in positive parental behavior. Other effects were just barely small or near zero with p values ranging from .23 to .99. (Note: one 6-month play, one 6-month feeding, and two 12-month feeding positive affect scores were missing.)

DISCUSSION

We aimed to better understand the consistency of positive parenting of infants among women at high risk for postpartum depression given their history of depression, considering both continuity and stability across time and context.

Consistency Across Age

With respect to time, we examined whether positive parenting increased, decreased, or remained constant as infants mature (Bornstein et al., 2017). If, on average, positive parenting remains relatively constant over time, this suggests that mothers who show, for example, low positive parenting early in their infants’ lives will likely continue to show low positive parenting over the course of infancy. If, however, on average positive parenting shows even small to moderate increases over the time course of infancy, as has been shown in samples not selected for depression (Cox et al., 2004; Dallaire & Weinraub, 2005), then low positive parenting with very young infants might be expected to improve over the course of infancy.

Group- and Individual-Level Continuity Across Age (Hypothesis 1).

We had hypothesized that among women at elevated risk for postpartum depression positive parenting during play would demonstrate discontinuity—specifically, become more positive—whereas parenting during feeding would show continuity across the first year of life. Overall, our group-level test of continuity failed to support Hypothesis 1; rather, we found across-age continuity (i.e., consistent levels in positive parenting) during play and discontinuity during feeding. In contrast, our individual analyses revealed partial support for Hypothesis 1 in that, although we again found across-age continuity during play, the findings supported the predicted continuity for parenting during feeding. Taken together, the group- and individual-level analyses consistently failed to support the first part of Hypothesis 1, that positive parenting during play would become more positive over time. In contrast, the individual analysis, but not the group-level analysis, yielded support for the second part of Hypothesis 1, that parenting during feeding would show continuity over time. We discuss this pattern of findings further when discussing overall interpretation of consistency across age findings.

The discrepancy between the group- and individual-level results for continuity of positive parenting during feeding is instructive. In general, group-level analyses are likely to overestimate discontinuity—this is the lesson we draw from our results. As the individual analyses show, the scores of more mothers than expected by chance changed little—demonstrating continuity—but those that did change, the direction of change shifted over the course of infants’ first year. That is, those who did change did so by decreasing in positive parenting between 3 and 6 months and then increasing from 6 to 12 months, thus suggesting discontinuity when only group means are considered, as in typical group analyses.

Group- and Individual-Level Stability Across Age (Hypothesis 3).

Hypothesis 3 predicted, and both typical group-level and individual-level analyses supported, that the rank order of positive parenting would remain relatively consistent (stable) over time in both the play and feeding contexts. Thus, our findings add to the one published study we found that considered women’s depression with regard to across-time stability and found a moderate degree of positive parenting stability from 2 to 9 months in a play context among postnatal depressed and well mothers (Murray et al., 2010). We discuss implications of this finding for theory and practice in the next section.

Role of Severity of Postpartum Depressive Symptoms Across Age (Hypothesis 4 and 5).

Further, we found support for our hypothesis that the pattern of change in positive parenting across age would be independent of depressive symptom severity. No associations were significant in either play or feeding.

Overall Interpretation of Findings on Consistency Across Age.

The finding, from analyses of both continuity and stability, using both group- and individual-level analyses, that positive parenting during play did not increase over the course of infancy and that rank orders of positive parenting remained relatively stable across age, in both play and feeding contexts, is concerning. First, our results suggest that findings from general population samples that show increases in positive parenting over infancy (Cox et al., 2004; Dallaire & Weinraub, 2005) cannot be generalized to women whose history of depression elevates their risk for postpartum depression. Second, the findings from general population samples of an increase in positive parenting over infants’ first year of life are interpreted to reflect that parenting during play becomes more easy-going and rewarding and that infants are becoming more positive, with some data to support those interpretations (Cox et al., 2004). Our findings suggest that the same cannot be assumed for women with a history of depression. Considering the added knowledge from our findings on stability (rank order), along with knowledge that the average level of positive parenting during play shows continuity (level), we have strong support for this conclusion.

Future studies might explore the mother, infant, or other factors that might be associated with the failure of positive parenting to increase over the course of infancy for women with a history of depression. Our findings regarding severity of depressive symptoms suggest the need to consider maternal factors other than current or recent (postpartum) depressive symptom levels. Constructs that might be explored in future studies include parenting self-efficacy beliefs, worry, stress, and social support, all of which are associated with depression and with quality of parenting infants (see Law et al., 2019; Zhang & Jin, 2016). In terms of infant factors that future researchers might consider is infant’s tendency to express negative affect, studied either in an observational context designed to elicit infant distress (Leerkes et al., 2009) or as negative affectivity temperament (Rothbart & Hwang, 2002). Mother-infant quality of attachment may also be important to consider (Mills-Koonce et al., 2008). In terms of other factors that researchers might consider to explain patterns of change in positive parenting over infancy, Cox et al. (2004) found no support for marital factors or education being associated with change in positive parenting over time; having a low family income was related to slightly increasing positive parenting over time. Some support for consideration of fathers comes from a finding from a prior study in our laboratory that in the first half of the first year of infants’ lives mothers’ higher depression symptom levels were predictive of fathers’ greater parenting involvement, whereas the pattern reversed for the second half of infants’ first year (Goodman et al., 2014). Thus, it will be important for future studies to consider a role of changes in fathers’ involvement (in relation to mothers’ depression symptom levels) in consistency of mothers’ positive parenting among mothers with a history of depression.

Overall, it is reassuring that we found continuity and stability rather than decreases in positive parenting over the course of infancy for the play context. With data from the NICHD Early Childcare study’s large sample, two studies found that more elevated depression symptom levels were associated with decreases over time in positive parenting during play specifically among: (1) mothers whose infants were later categorized as having disorganized attachment (Mills-Koonce et al., 2008) and (2) the small subset of mothers whose depressive symptoms were chronic (Campbell et al., 2007). Although concerning, both contexts associated with decreases in positive parenting over time represent small portions of the population.

Similarly, it is reassuring that, for the feeding context, we found that the decrease in level of positive parenting was specific to the time between infants’ ages of 3 to 6 months in that mothers appeared to recover by 12 months (Hypothesis 1), as well as support for rank order stability (Hypothesis 3). We found only two studies that examined consistency over time in positive parenting during feeding (Campbell et al., 1995; Seifer et al., 1992). Both found no evidence of depression being associated with consistency of positive parenting during feeding, consistent with our finding.

Overall our findings of both continuity (group and individual level) and stability during both contexts, as well as our findings on the role of postpartum depressive symptom severity level, are consistent with knowledge that vulnerabilities associated with mothers’ depression history may matter more than their depressive symptom levels across the first year postpartum. Further, given knowledge that even psychotherapy driven decreases in depression in mothers are associated with only a small change in parenting interaction patterns such as sensitivity (Cuijpers et al., 2015) and that residual effects of prior depression are associated with current parenting quality (Lovejoy et al., 2000), our findings suggest that interventions need to target parenting at least as much as efforts to treat depression. This conclusion was also reached by a review of the literatures on depression and parenting interventions (Goodman & Garber, 2017).

Consistency Across Context

With respect to context, we focused on two ecologically valid parenting tasks: play and feeding. Like our questions about consistency across time, we asked theory- and practice-relevant questions such as: to what extent is the amount of positive parenting observed in one context typical of what might be observed in another context? Might the characteristics of certain contexts either enable or interfere with mothers’ positive parenting, despite their elevated risk for postpartum depression? Because most studies relied on a single context, typically play, there is limited understanding of these important questions about the role of context.

Group- and Individual-Level Continuity Across Context (Hypothesis 2).

We expected that mothers with a history of depression would demonstrate discontinuity in their level of positive parenting across contexts. We found support for this hypothesis in that group-level analyses revealed higher mean values of positive parenting in play than feeding, moderately so at 3 months and strongly at 6 and 12 months. This finding is consistent with the idea that certain contexts, in this case feeding, may be more challenging for mothers or, conversely, the play context may facilitate positive parenting. These findings suggest the importance of coaching mothers in positive parenting during feeding of their infants, and not solely during play interactions. Individual analyses, however, suggested continuity.

As we noted earlier, the discrepancy between the group-level and individual results is instructive. Here the individual analyses showed that the scores of more mothers than expected by chance changed little from feeding to play—demonstrating continuity—but mothers who did change were more likely to have higher scores for play. Continuity is not necessarily negative, of course; mothers in the upper-right hand quadrant for example (see Figure 1) had consistently high scores. If we could identify them, coaching interventions might more efficiently be directed to mothers in the other three quadrants, especially the lower-left.

Group- and Individual-Level Stability Across Context (Hypothesis 3).

We found weak to moderate support for our expected stability (consistency of rank order) across contexts, both with typical group and individual-level analyses. We based this hypothesis on studies of positive parenting that sampled the general population (Maas et al., 2013; Masur & Turner, 2001). Thus, our findings suggest that regarding across-context stability one can generalize findings from the general population to samples of women with a history of depression. Moreover, considering Hypotheses 2 and 3 together, even in the context of finding discontinuity—mean differences in levels of positive parenting across contexts—rank orders during play and feeding remained similar, thus showing stability across contexts. The finding that mothers tend to maintain their relative rank across contexts is promising, as it suggests that if they manage to engage in high levels of positive parenting in one context, they likely do so also in another context. Conversely, if they are low in positive parenting, that is likely to be true in multiple contexts. The latter implies that interventions targeting parenting skills in one context (e.g., play) have potential to translate to parenting behaviors in other contexts (e.g., feeding). It will be important for future research to test this implication; we are not aware of any studies having done so. Moreover, to our knowledge, we provide the first findings on across-context stability of parenting that considered women’s depression.

Role of Severity of Postpartum Depressive Symptoms Across Context (Hypothesis 4).

We expected across-context variation to be largest for those women with more severe postpartum depressive symptomatology. We failed to support this hypothesis. Our findings suggest that, rather than postpartum specific depressive severity, what matters is the history of depression that this sample of women had in common. It will be up to future studies to examine the vulnerabilities associated with depression history that relate to women’s positive parenting in different contexts. Future studies might also examine whether tasks that are even more demanding, such as soothing a distressed infant, relative to more routine caregiving tasks, might be more influenced by postpartum depression severity levels.

Limitations and Strengths

Overall, our findings should be considered in the context of some limitations. First, we conducted a large number of statistical tests for Hypothesis 3, thereby increasing the risk of identifying significant-by-chance effects. To address such concerns, Cohen (1990) and Wilkinson and the Task Force on Statistical Inference (1999) recommend that investigators interpret overall patterns of significant effects, not just individual ones; that they be guided by predictions ordered from most to least important; and above all, that they focus on effect sizes. Bakeman and Quera (2011) provided an even more comprehensive summary of this issue. This advice has considerable merit and informed our interpretation of the results.

Second, we observed interactions for only 5 min in each context, yielding a total of 10 min across the two contexts. Concern about length of observation is mitigated by Lovejoy et al.’s (2000) finding from meta-analytic review, that shorter length of observation (1 to 10 min), which characterized about one-third of the reviewed studies, was associated with a significantly stronger effect size than longer observations.

Third, we were able to follow infants in our sample only through 12 months of age. What do our findings imply about parenting from 12 months forward? Else-Quest and colleagues (2011) found that mothers’ interactive qualities with their 12-month-old infants predicted “similar or equivalent” constructs through adolescence, taking both homotypic and heterotypic continuity into account.

Fourth, our findings can only be generalized to women with a history of depression. However, given the risks associated with this history, our sampling strategy yielded a group that has high clinical and public health significance.

Fifth, our findings are limited to positive parenting and, thus, cannot be generalized to negative or harsh parenting. Indeed, Bornstein and colleagues (2020) found that mothers’ parenting “response types” showed substantial variability in stability. Nonetheless, we noted strong theoretical and empirical support for a focus on positive parenting.

These limitations should be considered in the context of several strengths. We examined consistency over time and across two highly ecologically valid contexts, considering both continuity (consistency of level) and stability (consistency of rank order). Another noteworthy strength was our analytic approach—comparing traditional group-based analyses with individual-level analyses—which provided a more nuanced view of consistency. We addressed theory- and practice-relevant questions regarding continuity and stability of positive parenting in relation to women at elevated risk for postpartum depression. Our study design was longitudinal and prospective, with three sets of observations over infants’ first year of life.

Conclusions

Overall, we draw four primary conclusions. First, findings based on normative samples may not generalize to women with a history of depression. Second, women with a history of depression may benefit from interventions aimed at enhancing their positive parenting over the course of infancy, regardless of current or recent (postpartum) depressive symptom level. Third, our results underscore the importance of assessing parenting at multiple time points and across varying contexts. Fourth, considering not just group-level evidence for continuity but individual-level as well can often be instructive. Group-level analyses may underestimate the amount of continuity at an individual level.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE AND THEORY

First, our findings on continuity suggest the potential benefits of interventions designed to enhance the rewarding qualities of parenting for women with histories of depression. Second, although researchers often interpret their findings as suggesting the need to intervene earlier, we offer specific support for that conclusion with our continuity finding that women who show low positive parenting early in their infants’ lives will likely continue to show low positive parenting over the course of infancy. Third, having observed parenting in two ecologically valid contexts, we found that certain contexts (e.g., feeding) may be more challenging for mothers or, conversely, other contexts (e.g., play) may facilitate positive parenting, suggesting the importance of coaching mothers in positive parenting during a variety of contexts. Moreover, our finding that mothers tend to maintain their relative rank across contexts suggests that interventions targeting parenting skills in one context have potential to translate to parenting behaviors in other contexts. Further, clinicians might reserve limited intervention resources to women who show low levels of positive parenting in two or more contexts. Fourth, our findings on depression symptom levels imply that interventions to enhance positive parenting in women with histories of depression might focus as much on enhancing positive parenting and reducing vulnerabilities associated with their depression history as on aiming to reduce depressive symptom levels. Fifth, our findings imply the need to extend theory to consider which mother, child, or contextual factors relate to mothers’ stability or continuity of positive parenting and through what mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

Zachary Stowe, D. Jeffrey Newport, and Bettina Knight were primarily responsible for recruitment and determining the women’s eligibility for participation. We appreciate Meaghan McCallum’s involvement at the initiation of this project. Earlier publications—Davis et al., 2019; Laurent et al., 2018; and Lusby et al., 2016—drew dyads from the same project, thus some of the procedural details are the same.

Funding

This work was supported by 1 P50 MH077928-01A1, Perinatal Stress and Gene Influences: Pathways to Infant Vulnerability.

Role of the Funders/Sponsors

None of the funders or sponsors of this research had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

Each author signed a form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No authors reported any financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to the work described.

Ethical Principles

The authors affirm having followed professional ethical guidelines in preparing this work. These guidelines include obtaining informed consent from human participants, maintaining ethical treatment and respect for the rights of human or animal participants, and ensuring the privacy of participants and their data, such as ensuring that individual participants cannot be identified in reported results or from publicly available original or archival data. All women participated in an informed consent procedure, and the Emory University Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Contributor Information

Sherryl Goodman, 36 Eagle Row, PAIS Building, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia 30322.

Roger Bakeman, Georgia State University.

Anna Milgramm, State University of New York at Albany.

REFERENCES

- Abel KM, Hope H, Swift E, Parisi R, Ashcroft DM, Kosidou K, Osam CS, Dalman C, & Pierce M (2019). Prevalence of maternal mental illness among children and adolescents in the UK between 2005 and 2017: A national retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet Public Health, 4(6), e291–e300. 10.1016/s2468-2667(19)30059-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R (2005). Recommended effect size statistics for repeated measures designs. Behavior Research Methods, 37(3), 379–384. 10.3758/bf03192707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R (2006). Best practices in quantitative methods for developmentalists: VII. The practical importance of findings. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. https://doi.org/ISBN: 978-1-405-16941-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R (2018). KappaAcc: Deciding Whether Kappa is Big Enough by Estimating Observer Accuracy. Georgia State University website: http://bakeman.gsucreate.org/DevLabTechReport28.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, & Quera V (2011). Sequential Analysis and Observational Methods for the Behavioral Sciences. Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/cbo9781139017343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1997). Beck Depression Inventory: Second edition. The Psychological Corporation. 10.1037/t00742-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beeghly M, Weinberg MK, Olson KL, Kernan H, Riley J, & Tronick EZ (2002). Stability and change in level of maternal depressive symptomatology during the first postpartum year. Journal of Affective Disorders, 71(1–3), 169–180. 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00409-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH (2019). Parenting Infants. In Bornstein MH (Ed.), Handbook of Parenting. Vol. 1. Children and Parenting (3rd ed., pp. 3–55). Routledge. 10.4324/9780429440847-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, & Esposito G (2017). Continuity and Stability in Development. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), 113–119. 10.1111/cdep.12221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Hahn CS, Tamis-LeMonda CS, & Esposito G (2020). Stabilities of Infant Behaviors and Maternal Responses to Them. Infancy, 25(3), 226–245. 10.1111/infa.12326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Cohn JF, & Meyers T (1995). Depression in first-time mothers: Mother-infant interaction and depression chronicity. Developmental Psychology, 31, 349–357. 10.1037/0012-1649.31.3.349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Matestic P, von Stauffenberg C, Mohan R, & Kirchner T (2007). Trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and children’s functioning at school entry. Developmental Psychology, 43(5), 1202–1215. 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R (1985). The Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment: Instrument and manual. University of Wisconsin Medical School, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum. 10.2307/2290095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1990). Things I have learned (so far). American Psychologist, 45, 1304–1312. 10.1037/0003-066x.45.12.1304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Burchinal M, Taylor LC, Frosch C, Goldman B, & Kanoy K (2004). The transition to parenting: Continuity and change in early parenting behaviours and attitudes. In Continuity and change in family relations: Theory, method and empirical findings (pp. 201–239). [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Weitz E, Karyotaki E, Garber J, & Andersson G (2015). The effects of psychological treatment of maternal depression on children and parental functioning: a meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(2), 237–245. 10.1007/s00787-014-0660-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallaire DH, & Weinraub M (2005). The stability of parenting behaviors over the first 6 years of life. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 20(2), 201–219. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2005.04.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Goodman SH, Lavner JA, Maier M, Stowe ZN, Newport DJ, & Knight B (2019). Patterns of Positivity: Positive Affect Trajectories Among Infants of Mothers with a History of Depression. Infancy, 24(6), 911–932. 10.1111/infa.12314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Frey K, Panagiotides H, Yamada E, Hessl D, & Osterling J (1999). Infants of depressed mothers exhibit atypical frontal electrical brain activity during interactions with mother and with a familiar, nondepressed adult. Child Development, 70(5), 1058–1066. 10.1111/1467-8624.00078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wolff MS, & van IJzendoorn MH (1997). Sensitivity and Attachment: A Meta-Analysis on Parental Antecedents of Infant Attachment. Child Development, 68(4), 571–591. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb04218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, Clark R, & Owen MT (2011). Stability in Mother-Child Interactions from Infancy through Adolescence. Parenting: Science and Practice, 11(4), 280–287. 10.1080/15295192.2011.613724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T (2010). Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: a review. Infant Behavior & Development, 33(1), 1–6. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JBW (1995). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. American Psychiatric Press. 10.4135/9781412952644.n443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, & Garber J (2017). Evidence-Based Interventions for Depressed Mothers and Their Young Children. Child Development, 88(2), 368–377. 10.1111/cdev.12732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, & Halperin MS (2020). Perinatal Depression as an Early Stress: Risk for the Development of Psychopathology in Children. In Harkness K & Hayden EP (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Stress and Mental Health. Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190681777.013.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Lusby CM, Thompson K, Newport DJ, & Stowe ZN (2014). Maternal depression in association with fathers’ involvement with their infants: spillover or compensation/buffering? Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(5), 495–508. 10.1002/imhj.21469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Simon HFM, Shamblaw AL, & Kim CY (2020). Parenting as a Mediator of Associations between Depression in Mothers and Children’s Functioning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 10.1007/s10567-020-00322-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron J, O’Connor TG, Evans J, Golding J, & Glover V (2004). The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 80(1), 65–73. 10.1016/j.jad.2003.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, & Miller PC (1999). Enduring and different: a meta-analysis of the similarity in parents’ child rearing. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 223–254. 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AA (1975). Four-factor Index of Social Status. Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Ji S, Long Q, Newport DJ, Na H, Knight B, Zach EB, Morris NJ, Kutner M, & Stowe ZN (2011). Validity of depression rating scales during pregnancy and the postpartum period: impact of trimester and parity. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(2), 213–219. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Smith KE, & Swank PR (2006). Responsive parenting: establishing early foundations for social, communication, and independent problem-solving skills. Developmental Psycholology, 42(4), 627–642. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent H, Goodman SH, Stowe ZN, Halperin M, Khan F, Wright D, Nelson BW, Newport DJ, Ritchie JC, Monk C, & Knight B (2018). Course of ante- and postnatal depressive symptoms related to mothers’ HPA axis regulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(4), 404–416. 10.1037/abn0000348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law KH, Dimmock J, Guelfi KJ, Nguyen T, Gucciardi D, & Jackson B (2019). Stress, Depressive Symptoms, and Maternal Self-Efficacy in First-Time Mothers: Modelling and Predicting Change across the First Six Months of Motherhood. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 11(1), 126–147. 10.1111/aphw.12147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Nayena Blankson A, & O’Brien M (2009). Differential effects of maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress on social-emotional functioning. Child Development, 80(3), 762–775. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01296.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, & Neuman G (2000). Maternal depression and parenting behavior: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(5), 561–592. 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusby CM, Goodman SH, Yeung EW, Bell MA, & Stowe ZN (2016). Infant EEG and temperament negative affectivity: Coherence of vulnerabilities to mothers’ perinatal depression. Development and Psychopathology, 28(4pt1), 895–911. 10.1017/S0954579416000614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas AJ, Vreeswijk CM, & van Bakel HJ (2013). Effect of situation on mother-infant interaction. Infant Behavior & Development, 36(1), 42–49. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masur EF, & Turner M (2001). Stability and Consistency in Mothers’ and Infants’ Interactive Styles. Merrill Palmer Quarterly, 47(1), 100–120. 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2012.32.265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCall-Hosenfeld JS, Phiri K, Schaefer E, Zhu J, & Kjerulff K (2016). Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms Throughout the Peri- and Postpartum Period: Results from the First Baby Study. Journal of Women’s Health 25(11), 1112–1121. 10.1089/jwh.2015.5310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden KE, & Tamis-LeMonda CS (2013). Maternal Responsiveness, Intrusiveness, and Negativity During Play with Infants: Contextual Associations and Infant Cognitive Status in A Low-Income Sample. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34(1), 80–92. 10.1002/imhj.21376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills-Koonce WR, Gariepy JL, Sutton K, & Cox MJ (2008). Changes in maternal sensitivity across the first three years: are mothers from different attachment dyads differentially influenced by depressive symptomatology? Attachment & Human Development, 10(3), 299–317. 10.1080/14616730802113612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Halligan SL, Goodyer I, & Herbert J (2010). Disturbances in early parenting of depressed mothers and cortisol secretion in offspring: a preliminary study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 122(3), 218–223. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicely P, Tamis-LeMonda CS, & Grolnick WS (1999). Maternal responsiveness to infant affect: Stability and prediction. Infant Behavior and Development, 22(1), 103–117. 10.1016/s0163-6383(99)80008-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (1999). Child care and mother-child interaction in the first 3 years of life. Developmental Psychology, 35(6), 1399–1413. 10.1037/0012-1649.35.6.1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olejnik S, & Algina J (2003). Generalized eta and omega squared statistics: measures of effect size for some common research designs. Psychological methods, 8(4), 434. 10.1037/1082-989x.8.4.434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osofsky J (1987). Manual for coding maternal and infant global affect. Louisiana State University. [Google Scholar]

- Page M, Wilhelm MS, Gamble WC, & Card NA (2010). A comparison of maternal sensitivity and verbal stimulation as unique predictors of infant social-emotional and cognitive development. Infant Behavior & Development, 33(1), 101–110. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, & Hwang J (2002). Measuring infant temperament. Infant Behavior & Development, 25(1), 113–116. 10.1016/s0163-6383(02)00109-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Kennedy S, Gemar M, Hood K, Pedersen R, & Buis T (2006). Cognitive reactivity to sad mood provocation and the prediction of depressive relapse. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(7), 749–755. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifer R, Sameroff AJ, Anagnostopolou R, & Elias PK (1992). Mother-infant interaction during the first year: Effects of situation, maternal mental illness, and demographic factors. Infant Behavior & Development, 15(4), 405–426. 10.1016/0163-6383(92)80010-r [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman ME, Reichenberg A, Savitz DA, Cnattingius S, Lichtenstein P, Hultman CM, Larsson H, & Sandin S (2017). The risk factors for postpartum depression: A population-based study. Depression and Anxiety, 34(2), 178–187. 10.1002/da.22597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Clark LA, Strauss ME, & McCormick RA (1995). Testing a tripartite model: I. Evaluating the convergent and discriminant validity of anxiety and depression symptom scales. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(1), 3–14. 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson L, & Inference TF o. S. (1999). Statistical methods in psychology journals: Guidelines and explanations. American Psychologist, 54(8), 594. 10.1037/0003-066x.54.8.594 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, & Jin S (2016). The impact of social support on postpartum depression: The mediator role of self-efficacy. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(5), 720–726. 10.1177/1359105314536454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]