Abstract

Antifungal azoles (e.g., fluconazole) are widely used for prophylaxis or treatment of Candida albicans infections in immunocompromised individuals, such as those with AIDS. These individuals are frequently treated with a variety of additional antimicrobial agents. Potential interactions between three azoles and 16 unrelated drugs (antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal, and antiprotozoal agents) were examined in vitro. Two compounds, tested at concentrations achievable in serum, demonstrated an antagonistic effect on azole activity against C. albicans. At fluconazole concentrations two to four times the 50% inhibitory concentration, C. albicans growth (relative to treatment with fluconazole alone) increased 3- to 18-fold in the presence of albendazole (2 μg/ml) or sulfadiazine (50 μg/ml). Antagonism (3- to 78-fold) of ketoconazole and itraconazole activity by these compounds was also observed. Since azole resistance has been correlated with overexpression of genes encoding efflux proteins, we hypothesized that antagonism results from drug-induced overexpression of these same genes. Indeed, brief incubation of C. albicans with albendazole or sulfadiazine resulted in a 3-to->10-fold increase in RNAs encoding multidrug transporter Cdr1p or Cdr2p. Zidovudine, trimethoprim, and isoniazid, which were not antagonistic with azoles, did not induce these RNAs. Fluphenazine, a known substrate for Cdr1p and Cdr2p, strongly induced their RNAs and, consistent with our hypothesis, strongly antagonized azole activity. Finally, antagonism was shown to require a functional Cdr1p. The possibility that azole activity against C. albicans is antagonized in vivo as well as in vitro in the presence of albendazole and sulfadiazine warrants investigation. Drug-induced overexpression of efflux proteins represents a new and potentially general mechanism for drug antagonism.

In recent decades there has been a dramatic increase in the incidence of infection by various Candida species, with Candida albicans accounting for >75% of all cases. This increase can be attributed to the increasing numbers of immunocompromised patients. Indeed, mucosal candidiasis is the most common opportunistic fungal infection in AIDS patients (19, 29).

Several azole antifungals, which inhibit the enzyme lanosterol 14-demethylase in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway, are currently used to treat candidal infections. Fluconazole is the most widely used azole for systemic candidiasis due to its high solubility, low toxicity, and wide tissue distribution (19). It is also widely used prophylactically in high-risk immunocompromised individuals. However, treatment failures are increasing, especially in AIDS patients, where the isolation of fluconazole-resistant C. albicans is occurring more frequently (4, 26, 45). Resistance to one azole is usually associated with cross-resistance to other azoles (2, 13).

Several studies have shown that clinical isolates of azole-resistant C. albicans from AIDS patients express high levels of RNAs encoding the multidrug resistance proteins Cdr1p, Cdr2p, and Mdr1p (18, 36, 44, 45). Cdr1p and Cdr2p are members of the ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. These transporters use the energy from ATP hydrolysis to pump substrates out of the cell. Mdr1p (formerly called BenR) is a member of the major facilitator superfamily and transports substrates across a membrane in exchange for H+ ions. Deletion of CDR1 and CDR2 results in hypersusceptibility to several azole antifungals, directly supporting their role in azole resistance, while overexpression of MDR1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae confers fluconazole resistance (34–36).

Immunocompromised patients are frequently treated either therapeutically or prophylactically with diverse combinations of antibacterial, antiviral, antiprotozoal, and antifungal agents. We examined the in vitro effects of 16 such agents on the anticandidal activity of azoles and identified two antagonistic interactions. RNA analysis was performed to test the hypothesis that antagonism of azole activity resulted from the transcriptional induction of multidrug transporter genes.

(This work was presented in part at the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Diego, Calif., 1998 [10].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

C. albicans 24433 and 90028 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md. C. albicans CAF2.1 (ura3::imm434/URA3) and its isogenic derivative DSY448 (cdr1::hisG-URA3-hisG/cdr1::hisG) were obtained from D. Sanglard (35). YPD medium contained 1% yeast extract (Difco), 2% Bacto Peptone (Difco), and 2% dextrose; pH was 6.3. RPMI 1640 medium, with l-glutamate but without sodium bicarbonate (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), was supplemented with 2% dextrose and 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS), and pH was adjusted to 7.0. Strains 24433, 90028, and CAF2.1 have normal azole susceptibility, with fluconazole MICs of 1 μg/ml using the standard National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) M27-A protocol (25).

Antimicrobial agents.

All drugs were obtained from Sigma, with the following exceptions: azithromycin (Pfizer, Groton, Conn.), ciprofloxacin (Miles, West Haven, Conn.), fluconazole (Pfizer), itraconazole (Janssen, Piscataway, N.J.), and ketoconazole (Janssen). Compounds were dissolved in 0.9% saline (fluconazole), ethanol (pyrimethamine), water (cycloheximide, 5-flucytosine, foscarnet, isoniazid, lincomycin, pyrizinamide, streptomycin, sulfadiazine, and zidovudine), or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (all others).

Effects on azole activity.

Assays were performed in flat-bottomed 96-well microtiter plates. A 100-μl volume of YPD medium containing a 2× concentration of the test compound (see Table 1) was added to a series of wells, except for the initial well, to which 200 μl was added. Control series received YPD alone or YPD plus 0.5% DMSO. Azole (5 μl) was added to the initial well to twice the maximum concentration tested (i.e., 8 μg/ml for fluconazole and 0.2 μg/ml for itraconazole and ketoconazole), and twofold serial dilutions were made by transferring 100 μl of this solution to subsequent wells. The final well in each series received no azole and served as a growth control. Mid-log-phase cultures of C. albicans 24433, 90028, CAF2.1, or DSY448 were diluted in YPD and 100 μl was added to each well to give a final density of 104 cells/ml. Plates were sealed with parafilm and incubated for 18 h with shaking at 30°C except where noted otherwise. Susceptibility assays were also performed in RPMI 1640 medium according to the published NCCLS M27-A protocol (25). In initial studies (Table 1), growth was examined by measuring absorbance at 492 nm in a microplate reader. Subsequently, cells were counted with a hemocytometer. The azole concentration that reduced the cell number to 50% of azole-free controls (IC50) was estimated from plots of cell number versus azole concentration. Fold increases were calculated by comparing cell numbers in azole plus test compound versus azole alone.

TABLE 1.

Effects of various anti-infective compounds on the activity of fluconazole against C. albicans

| Compound | Indicationa | Change in absorbanceb | Concentration tested (μg/ml)c | Referencec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albendazole | Microsporidia | +0.752 | 2 | 24 |

| Amphotericin B | Systemic fungi | −0.122 | 0.5 | 43 |

| Azithromycin | Mycobacteria | −0.090 | 2 | 15 |

| Ciprofloxacin | Mycobacteria | −0.093 | 2 | 32 |

| Doxycycline | Mycobacteria | −0.113 | 6 | 16 |

| 5-Flucytosine | Systemic fungi | −0.124 | 0.5e | 28 |

| Foscarnet | Herpesvirus | −0.082 | 150 | 39 |

| Isoniazid | Mycobacteria | −0.103 | 5 | 40 |

| Lincomycind | Mycobacteria | −0.059 | 8 | 22 |

| Pyrimethamine | Toxoplasma | −0.032 | 0.2 | 27 |

| Pyrazinamide | Mycobacteria | −0.102 | 40 | 42 |

| Rifampin | Mycobacteria | −0.106 | 9 | 21 |

| Sulfadiazine | Toxoplasma | +0.660 | 50 | 30 |

| Sulfamethoxazole | Pneumocystis | −0.146 | 50 | 3 |

| Trimethoprim | Pneumocystis | −0.047 | 5 | 3 |

| Zidovudine | HIV | −0.047 | 1 | 33 |

Pathogen or pathogens listed represent the primary target(s) for that compound in AIDS patients and other immunocompromised patients.

Absorbance readings (492 nm) were taken from cultures of C. albicans ATCC 24433 treated with fluconazole (1 μg/ml) and the compounds listed at the concentrations indicated for 18 h in YPD medium at 30°C. Units listed are the deviations from cultures treated with fluconazole (1 μg/ml) alone (A492, 0.303). Values shown are the averages of two experiments.

Compounds were tested at concentrations approximating their average or peak serum levels as reported in the listed reference.

Closely related to the more commonly used clindamycin.

Concentration tested was below average serum level (80 μg/ml) which would be highly inhibitory and therefore obscure any effect on fluconazole activity.

RNA induction and isolation.

Cultures (2 ml) of log-phase C. albicans in YPD (3 × 107 to 5 × 107 cells/ml) were exposed to test compounds at the indicated concentrations for 30 min at 30°C with gentle shaking. Controls received an equivalent amount of DMSO or were untreated. RNA was extracted by a modification of the procedure described by Schmitt et al. (37) as follows. Treated cultures were transferred to 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes on ice, centrifuged briefly at 16,000 × g, and washed twice in ice-cold 50 mM sodium acetate–10 mM EDTA buffer (pH 5.0). After the last wash, the pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of ice-cold sodium acetate-EDTA buffer followed by the addition of 200 μl of acid-treated glass beads (diameter, 0.3 mm), 10 μl of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 200 μl of phenol (saturated with sodium acetate-EDTA buffer and prewarmed to 65°C). Cells were disrupted by periodic vigorous vortexing with incubation at 65°C for a total of approximately 8 min. Samples were cooled for 5 min on ice and centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000 × g. The aqueous phase containing the RNA was transferred to a new tube containing an equal volume of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) and vortexed briefly. After centrifugation, the aqueous phase was transferred to a tube containing 2.5 volumes of cold 95% ethanol and 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.3). The chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction was omitted when RNA was isolated for slot blot analysis.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR.

Ethanol-precipitated RNA was washed in 70% ethanol after centrifugation and resuspended in RNase-free water. The absorbance at 260 nm was measured to determine concentration. CDR1-CDR2 and MDR1 cDNAs were prepared with Moloney murine leukemia virus (Mo-MuLV) reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs) as recommended by the manufacturer, using 3 μg of total RNA and primers complementary to nucleotides +1388 to +1408 of CDR1 (equivalent to +1378 to +1398 of CDR2) and nucleotides +1023 to +1041 of MDR1 (8, 31, 34). Each reaction had a parallel reaction lacking Mo-MuLV reverse transcriptase to confirm that the PCR product was derived from cDNA rather than genomic DNA contaminants. PCR was then performed by using nested reverse primers (i.e., immediately upstream of the original primers) in conjunction with forward primers specific for CDR1 nucleotides +903 to +923 (equivalent to +894 to +914 of CDR2) and MDR1 nucleotides +453 to +471. Three independent amplifications were conducted for 20, 22, and 25 cycles to ensure that amplification during the logarithmic phase was obtained. Cycling conditions were 94°C for 1 min, 65°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. Controls examined C. albicans actin RNA (+319 to +829 of ACT [20]). PCR products were compared by gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining.

RNA hybridization analysis.

For Northern analysis, ethanol-precipitated RNA was washed in 70% ethanol after centrifugation and treated, electrophoresed, and blotted as described previously (1). For slot blot analysis, purified RNA was dissolved in 500 μl of H2O and denatured by the addition of 300 μl of 20× SSPE (3.6 M sodium chloride, 0.2 M sodium phosphate, 20 mM EDTA [pH 7.0]) and 200 μl of 37% formaldehyde for 15 min at 65°C with occasional vortexing. Either 50 μl (for ACT probing) or 200 μl (for other probes) of denatured RNA was applied to nylon membrane under vacuum by using a Bio-Dot SF apparatus (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). Membranes were rinsed in 2× SSPE and UV crosslinked. Northern and slot blots were hybridized at 42°C overnight to random primed (Promega, Madison, Wis.) 32P-labeled PCR products specific for C. albicans ACT (as above), CDR1 (−184 to +261), CDR2 (−187 to +259), and MDR1 (+453 to +1041). The hybridization buffer contained 50% formamide, 5× SSPE, 5× Denhardt’s reagent, 0.1% SDS, and 100 μg of denatured herring sperm DNA/ml. Blots were washed under high-stringency conditions (0.1× SSPE–0.1% SDS at 65°C) and exposed to film for 13 to 48 h.

Fluphenazine disk diffusion assay.

A log-phase culture of C. albicans 24433 was diluted to 2 × 107 cells/ml in YPD and used to inoculate YPD agar plates (with or without fluconazole at indicated concentrations) with a cotton swab. Sterile paper disks were applied to the plates to which 20 or 40 μg of fluphenazine or DMSO vehicle was added (total volume, 8 μl). Plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 h (0 and 1 μg of fluconazole/ml), 36 h (2 μg of fluconazole/ml), or 48 h (4 μg of fluconazole/ml).

RESULTS

Selected antimicrobial agents antagonize fluconazole activity against C. albicans in vitro.

Sixteen compounds used to treat bacterial, viral, fungal, or protozoal infections in immunocompromised patients were screened for in vitro effects on fluconazole activity versus C. albicans 24433 in YPD medium. The concentrations tested were based on average or peak serum concentrations in vivo, where known (see Table 1 for references). Two compounds, 5-flucytosine and amphotericin B (both at 0.5 μg/ml), had inhibitory activity against C. albicans by themselves; the remainder were inactive at the concentrations tested. However, 2 of the 16 compounds, albendazole (2 μg/ml) and sulfadiazine (50 μg/ml), demonstrated antagonistic activity when tested in combination with fluconazole (Table 1).

Antagonism of fluconazole activity by albendazole and sulfadiazine extends to a second C. albicans strain and to other azoles.

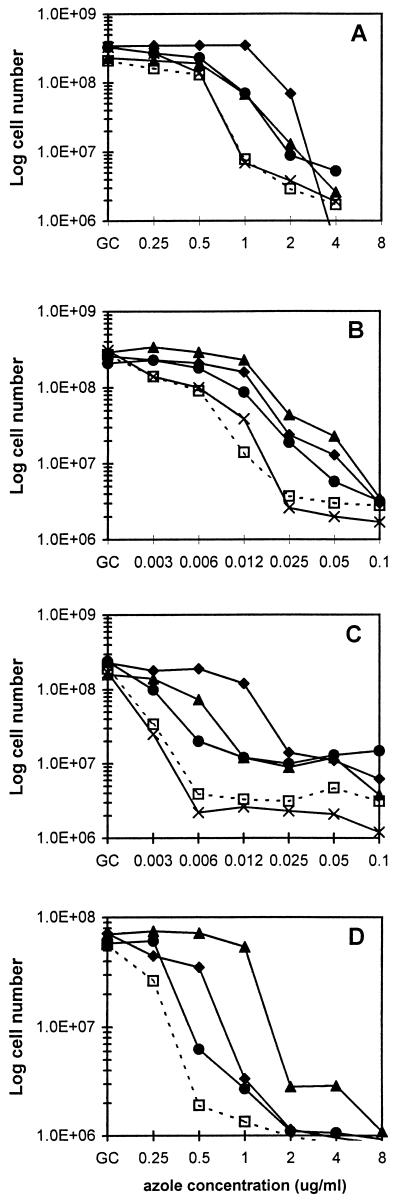

To quantitate the antagonism of azole activity, the assays were repeated and cell numbers were determined. The results for C. albicans 90028 are presented in Fig. 1A to C; comparable results were obtained with strain 24433, as summarized in Table 2. In YPD medium, albendazole and sulfadiazine demonstrated antagonistic activity at fluconazole concentrations of 1 to 4 μg/ml (Fig. 1A). Maximal antagonism was observed at 1 μg of fluconazole/ml, with albendazole or sulfadiazine addition increasing the cell number ninefold. Both compounds similarly antagonized the activity of itraconazole (6-to-16-fold-increased growth at 12 ng of itraconazole/ml; Fig. 1B) and ketoconazole (5-to-19-fold-increased growth at 6 ng/ml; Fig. 1C). In all three cases, antagonism was maximal at azole concentrations of two to four times the IC50 for that azole. Also, antagonism was observed at albendazole concentrations as low as 0.5 μg/ml (not shown). The effects of albendazole and sulfadiazine on the IC50 were relatively modest: fold increases of 1.6 to 8.8 for albendazole and 1.0 to 2.5 for sulfadiazine were observed (Table 2). For comparison, the compounds isoniazid (Fig. 1A to C and Table 2), zidovudine, and trimethoprim (not shown) had little effect on azole activity.

FIG. 1.

Antagonism of azole activity against C. albicans by selected compounds. C. albicans 90028 was cultured 18 h at 30°C in YPD medium with fluconazole (A), itraconazole (B), or ketoconazole (C) at the indicated concentrations, with the addition of DMSO vehicle (□, 0.5%), albendazole (▴, 2 μg/ml), fluphenazine (⧫, 20 μg/ml), sulfadiazine (●, 50 μg/ml), or isoniazid (×, 5 μg/ml). (D) C. albicans 24433 was cultured for 48 h in RPMI 1640 medium with fluconazole at the indicated concentrations and with the addition of DMSO or a second drug as above. For panels A to D, data points represent the averages from two independent experiments performed in triplicate. Note that cell numbers are expressed on a log scale. GC, azole-free growth control.

TABLE 2.

Effects of selected compounds on the activity of different azoles against two strains of C. albicans

| Compound (concentration) | Azole | Strain | IC50a (μg/ml) | Fold increase in IC50 | Maximum fold increase in cell number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Fluconazole | 24433 | 0.50 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 0.21b | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| 90028 | 0.60 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Itraconazole | 24433 | 0.0047 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 90028 | 0.0029 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Ketoconazole | 24433 | 0.0025 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 90028 | 0.0019 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Albendazole | Fluconazole | 24433 | 0.95 | 1.9 | 9.5 |

| (2 μg/ml) | 0.48b | 2.3 | 18 | ||

| 90028 | 0.98 | 1.6 | 9.0 | ||

| Itraconazole | 24433 | 0.018 | 3.8 | 4.5 | |

| 90028 | 0.015 | 5.2 | 16 | ||

| Ketoconazole | 24433 | 0.022 | 8.8 | 6.5 | |

| 90028 | 0.0057 | 3.0 | 19 | ||

| Sulfadiazine | Fluconazole | 24433 | 0.75 | 1.5 | 4.9 |

| (50 μg/ml) | 0.36b | 1.7 | 3.3 | ||

| 90028 | 0.63 | 1.1 | 9.0 | ||

| Itraconazole | 24433 | 0.010 | 2.1 | 78 | |

| 90028 | 0.0072 | 2.5 | 6.2 | ||

| Ketoconazole | 24433 | 0.0025 | 1.0 | 2.9 | |

| 90028 | 0.0025 | 1.3 | 5.2 | ||

| Fluphenazine (20 μg/ml) | Fluconazole | 24433 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 15 |

| 1.3b | 6.2 | 40 | |||

| 90028 | 1.8 | 3.0 | 45 | ||

| Itraconazole | 24433 | 0.012 | 2.6 | 20 | |

| 90028 | 0.0086 | 3.0 | 11 | ||

| Ketoconazole | 24433 | 0.018 | 7.2 | 20 | |

| 90028 | 0.013 | 6.8 | 49 | ||

| Isoniazid | Fluconazole | 24433 | 0.39 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| (5 μg/ml) | 90028 | 0.50 | 0.8 | 1.3 | |

| Itraconazole | 24433 | 0.0049 | 1.0 | 1.2 | |

| 90028 | 0.0020 | 0.7 | 1.7 | ||

| Ketoconazole | 24433 | 0.0030 | 1.2 | 1.5 | |

| 90028 | 0.0017 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

Unless otherwise noted, values were obtained after an 18-h incubation in YPD medium with shaking at 30°C.

Values are data obtained in RPMI 1640 medium at 48 h.

Antagonism of fluconazole activity is not time, temperature, or medium dependent.

The results presented above were generated with an incubation time of 18 h, an incubation temperature of 30°C, and undefined YPD medium. However, antagonism was observed up to 40 h (not shown); with longer incubations antagonism was obscured by the “trailing effect” (C. albicans growth at inhibitory azole concentrations). Selected experiments (involving fluconazole and strain 24433) were repeated with an incubation temperature of 37°C, and comparable antagonism was obtained (not shown). Finally, this same set of experiments was repeated using the defined medium RPMI 1640 according to the NCCLS M27-A protocol (25); again, comparable results were obtained (Fig. 1D and Table 2).

Antagonism is correlated with induction of multidrug resistance genes.

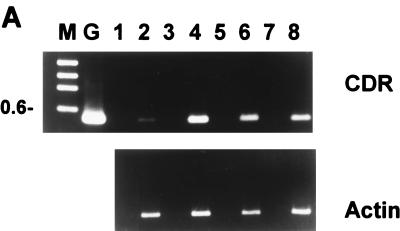

We hypothesized that antagonism of azole activity by albendazole and sulfadiazine resulted from their transcriptional induction of genes encoding multidrug resistance transporters which recognize azoles as substrates. This was initially tested by an RT-PCR assay. As shown in Fig. 2A, incubation of C. albicans 24433 with 2 μg of albendazole/ml for only 15 min resulted in a fourfold increase in the level of CDR1-CDR2 RNA. RNA levels then declined somewhat at 30 and 45 min. These results were confirmed by Northern analysis using a CDR1-specific probe (not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effects of selected antimicrobial agents on the expression of C. albicans multidrug transporter genes. (A) RT-PCR was used to determine the relative levels of CDR1-CDR2 or ACT (control) RNAs after exposure of cultures to 2 μg of albendazole/ml. Template cDNAs were prepared from cells treated for 0 (lanes 1 and 2), 15 (lanes 3 and 4), 30 (lanes 5 and 6), and 45 (lanes 7 and 8) min. PCR was conducted for 20 cycles, which was within the logarithmic phase of amplification as determined in control experiments. Reverse transcriptase-containing samples are in lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8, while controls without reverse transcriptase (to detect genomic DNA contamination) are in lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7; no contamination was detected. DNA size markers are in lane M; the 0.6-kbp band is indicated. Lane G is genomic DNA amplified with the CDR1-CDR2 primers. Comparable results were obtained in a second, independent experiment (not shown). (B) RNA slot blot hybridization analysis was used to determine the relative levels of ACT, CDR1, and CDR2 RNAs after 30-min exposure of cultures to the indicated drugs. Drug-free controls received vehicle only and are in the lanes labeled 5 (−DMSO) and 25 (+DMSO). Drug concentrations were 1, 5, and 25 μg/ml except for sulfadiazine, for which concentrations were 5, 25, and 50 μg/ml. Note that albendazole has low aqueous solubility, which would explain the observed decrease in CDR1 induction at 25 μg/ml. Comparable results were obtained in two to three independent experiments (not shown).

Subsequent assays employed RNA slot blots, which are more quantitative and capable of analyzing more samples. A 30-min incubation of C. albicans 24433 (Fig. 2B) or 90028 (not shown) with albendazole (1 and 5 μg/ml) or sulfadiazine (50 μg/ml) resulted in 3-to->10-fold increases in the levels of CDR1 or CDR2 RNAs. (The decreased induction by albendazole at 25 μg/ml is likely due to precipitation of this poorly soluble compound at this concentration). No increase in MDR1 (BenR) RNA was detected within 45 min by either slot blot or RT-PCR (not shown). Three drugs which were not antagonistic—zidovudine, isoniazid, and trimethoprim—did not induce expression of CDR1, CDR2, or MDR1 (Fig. 2B and data not shown).

Fluphenazine also induces multidrug transporter genes and antagonizes azole activity.

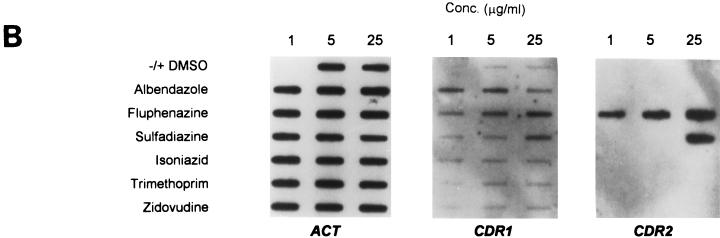

Fluphenazine is structurally and mechanistically unrelated to albendazole, sulfadiazine, and azoles but is a known substrate for Cdr1p and Cdr2p transport (34). It was of interest, therefore, to test its effects on multidrug resistance gene expression and azole activity. Fluphenazine strongly induced the expression of both CDR1 RNA (at 5 and 25 μg/ml) and CDR2 RNA (at 1, 5, and 25 μg/ml) (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, fluphenazine antagonized fluconazole, itraconazole, and ketoconazole activity up to 49-fold at azole concentrations two- to fourfold above the azole IC50 (Fig. 1 and Table 2). At higher azole concentrations (eightfold above the IC50), the antagonistic activity of fluphenazine was reproducibly replaced by additive or synergistic activity, as most readily visualized in a disk diffusion assay (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Disk diffusion assay to visualize effects of fluphenazine on azole activity. Fluphenazine (0, 20, or 40 μg) in 8 μl of DMSO was applied to paper disks placed on YPD plates swabbed with C. albicans. Plates contained either 0, 1, 2, or 4 μg of fluconazole/ml as indicated. Antagonism is indicated by the increased growth around the fluphenazine-containing disks on plates containing 1 and 2 μg of fluconazole/ml; synergistic or additive activity is indicated by the decreased growth around these disks on the 4-μg/ml fluconazole plate.

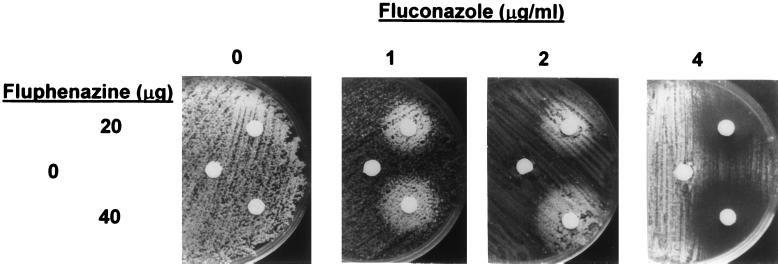

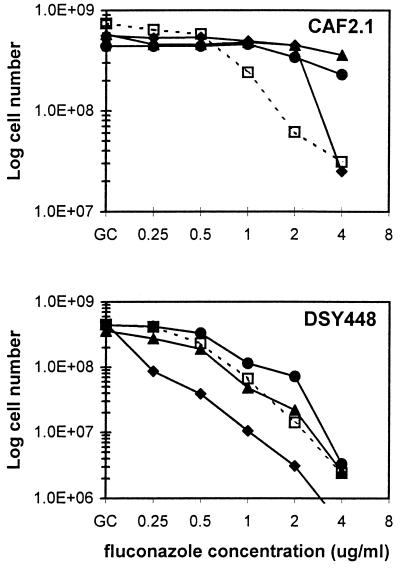

Antagonism requires a functional CDR1.

To further test the role of Cdr1p in the antagonism of azole activity, growth assays were repeated using a CDR1 null mutant (35). Although fluconazole hypersensitive, this mutant remains resistant to albendazole and sulfadiazine at high concentrations (20 and 200 μg/ml, respectively). While antagonism of fluconazole activity was reproduced in the parent strain CAF2.1, albendazole had no apparent effect on fluconazole activity in the CDR1 null mutant (Fig. 4). Antagonism due to sulfadiazine was also reduced in the mutant strain, although still detectable at 1 and 2 μg of fluconazole/ml; this may reflect induction of CDR2. At the concentrations tested, fluphenazine-fluconazole combinations were additive or synergistic in the CDR1 null mutant, consistent with its hypersensitivity to both compounds (35).

FIG. 4.

Role of CDR1 in antagonism of azole activity by albendazole, sulfadiazine, and fluphenazine. Growth of C. albicans CAF2.1 (CDR1+) and DSY448 (ΔCDR1) at different fluconazole concentrations was examined in the presence of DMSO (□, 0.5%), albendazole (▴, 2 μg/ml), fluphenazine (⧫, 20 μg/ml), or sulfadiazine (●, 50 μg/ml). Note that cell numbers are expressed on a log scale. GC, azole-free growth control. Data represent results of two independent experiments done in duplicate.

DISCUSSION

The treatment or prophylaxis of candidiasis in immunocompromised patients is potentially complicated by drug interactions, as these patients are often undergoing treatment or prophylaxis for other opportunistic infections in addition to their anti-human immunodeficiency virus therapy. We tested 15 diverse compounds that show little or no activity against C. albicans, as well as two antifungal compounds, for in vitro interactions with antifungal azoles. Albendazole and sulfadiazine (primary treatments for microsporidial and Toxoplasma gondii infections, respectively, in immunocompromised patients) along with fluphenazine (a calmodulin antagonist with weak antifungal activity) antagonized azole activity against C. albicans. Comparable results were obtained with three different C. albicans strains (24433, 90028, and CAF2.1), three different azoles (triazoles fluconazole and itraconazole and the imidazole ketoconazole), and different assay conditions (medium, temperature, and time).

To ensure standardized clinical laboratory reporting, antagonism between antifungal compounds has been defined as a ≥2-fold increase in MIC, or fractional inhibitory concentration of 2, relative to the compounds used alone (23). Our data are expressed in terms of IC50s and fold increases since these are more quantitative and less subjective measures than MIC, and consequently these definitions for antagonism cannot be directly applied. Nevertheless, a comparison of Fig. 1 and Table 2 suggests that the data presented for fold increases in IC50 would approximate the fold increases in MIC (using the standard definition of C. albicans MIC as 20% of control growth). Some of the fold increases in IC50 are <2, especially for sulfadiazine, and hence not antagonistic by the definition above. However, sulfadiazine-dependent reductions in azole activity were clearly significant (median, 5.2-fold) at higher azole concentrations. Since drug interactions are complex and may occur at different thresholds (as with sulfadiazine), the use of rigid definitions is not always appropriate.

The azoles are substrates for the C. albicans ABC transporters Cdr1p and Cdr2p as evidenced by the azole hypersensitivity associated with disruption of their genes (34, 35). RNA analysis following brief exposure to albendazole, sulfadiazine, and fluphenazine revealed that these compounds, but not three nonantagonistic control compounds, induced the expression of CDR1 alone or in combination with CDR2. Thus, the most likely explanation for the observed antagonism is azole efflux following induction of multidrug transporter genes by these unrelated compounds. The extent of antagonism was roughly correlated with the extent of induction: that of fluphenazine (which induced both CDR1 and CDR2) was greater than that of albendazole (which induced CDR1 only), which was comparable to that of sulfadiazine (which induced CDR1 weakly and CDR2 strongly). While antagonistic at lower fluconazole concentrations, at higher concentrations fluphenazine was paradoxically additive or synergistic. This could reflect the fact that fluphenazine is a known substrate for Cdr1p and Cdr2p (34, 35) and thus may compete with azoles for efflux; in addition, it is weakly active by itself (IC50, 50 μg/ml).

The question of why these three compounds and not others induced multidrug transporter genes, leading to azole antagonism, may not have a simple answer. Seelig (38) observed that compounds which were inducers of P-glycoprotein (the primary ABC transporter involved in mammalian multidrug resistance) shared electron donor groups within a certain spatial relationship, implying a structural basis for inducing activity. However, several benzimidazoles tested that are structurally related to albendazole did not induce CDR1 (not shown). Similarly, while sulfadiazine induced CDR1 and CDR2, the related sulfamethoxazole had no effect on expression of these genes (not shown) or on azole activity (Table 1). Furthermore, compounds that induced C. albicans multidrug transporter genes generated different patterns of induction: albendazole induced only CDR1 while fluphenazine and sulfadiazine induced both CDR1 and CDR2 to different extents, suggesting that the regulatory mechanisms involved are complex. Further studies examining the basis for transcriptional induction of multidrug resistance genes are clearly required.

Drug-induced expression of multidrug transporter genes has now been reported in the model fungi Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Aspergillus nidulans along with the opportunistic pathogen C. albicans (5–7, 11, 12, 14, 18). It is likely therefore that multidrug transporter induction leading to antagonism of azole activity operates in other clinically relevant fungi. A variety of compounds have been reported to antagonize azole activity against different fungi, such as Blastomyces dermatitidis (9) and more recently Candida glabrata (41). In addition, recent studies in our laboratory have demonstrated induction of ABC transporter genes and antagonism of azole activity in Candida krusei by albendazole and cycloheximide (17).

We are not aware of any evidence that albendazole or sulfadiazine antagonize azole activity in vivo; nevertheless, in light of our in vitro results, that possibility should be carefully considered. Furthermore, the 16 compounds tested here are a representative but clearly incomplete list of compounds that might be used clinically in combination with antifungal azoles. The testing of additional compounds for antagonistic activity, or induction of multidrug resistance genes, is therefore advisable.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Sanglard (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland) for providing C. albicans strains.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AI32433.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Short protocols in molecular biology. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1997. pp. 4-22–4-25. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barchiesi F, Colombo A L, McGough D A, Fothergill A W, Rinaldi M G. In vitro activity of itraconazole against fluconazole-susceptible and -resistant Candida albicans isolates from oral cavities of patients with human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1530–1533. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.7.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaser J, Joos B, Opravil M, Luthy R. Variability of serum concentration of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole during high dose therapy. Infection. 1993;21:206–209. doi: 10.1007/BF01728888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boken D, Swindells S, Rinaldi M. Fluconazole resistant Candida albicans. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:1018–1021. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.6.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delahodde A, Delaveau T, Jacq C. Positive autoregulation of the yeast transcription factor Pdr3p, which is involved in control of drug resistance. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4043–4051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edlind T D, Henry K W, Katiyar S K. Abstracts of the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Genetics of MDR-mediated azole resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, abstr. C-154; p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandes L, Rodrigues-Pousada C, Struhl K. Yap, a novel family of eight bZIP proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae with distinct biological functions. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6982–6993. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.6982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fling M E, Kopf A T, Dorman J A, Smith H A, Koltin Y. Analysis of a Candida albicans gene that encodes a novel mechanism for resistance to benomyl and methotrexate. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;227:318–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00259685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvey R P, Isenberg R A, Stevens D A. Molecular modifications of imidazole compounds: studies of activity and synergy in vitro and of pharmacology and therapy of Blastomycosis in a mouse model. Rev Infect Dis. 1980;2:559–569. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henry K W, Edlind T D. Abstracts of the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Induction of multidrug resistance genes in Candida albicans by antimicrobial agents leads to antagonism of azole activity, abstr. J-89; p. 476. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernaez M L, Gil C, Pla J, Nombela C. Induced expression of the Candida albicans multidrug resistance gene CDR1 in response to fluconazole and other antifungals. Yeast. 1998;14:517–526. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980430)14:6<517::AID-YEA250>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirata D, Yano K, Miyahara K, Miyakawa T. Saccharomyces cerevisiae YDR1, which encodes a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily, is required for multidrug resistance. Curr Genet. 1994;26:285–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00310491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson E M, Richardson M D, Warnock D W. In vitro resistance to imidazole antifungals in Candida albicans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1984;13:547–558. doi: 10.1093/jac/13.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanazawa S, Driscoll M, Struhl K. ATR1, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene encoding a transmembrane protein required for aminotriazole resistance. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:664–673. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.2.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karcioglu Z A, El-Yazigi A, Jabak M H, Choudhury A H, Ahmed W S. Pharmacokinetics of azithromycin in trachoma patients: serum and tear levels. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:658–661. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)94020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlsson M, Hammers S, Nilsson-Ehle I, Malmborg A S, Wretlind B. Concentration of doxycycline and penicillin G in sera and cerebrospinal fluid of patients treated for neuroborreliosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1104–1107. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katiyar S K, Edlind T D. Abstracts of the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. Identification of Candida krusei multidrug resistance genes: potential role in azole resistance, abstr. C-153; p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishnamurthy S, Gupta V, Prasad R, Panwar S L, Prasad R. Expression of CDR1, a multidrug resistance gene of Candida albicans—transcriptional activation by heat shock, drugs, and steroid hormones. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;160:191–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lortholary O, Dupont B. Antifungal prophylaxis during neutropenia and immunodeficiency. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:477–504. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.3.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Losberger C, Ernst J F. Sequence of the Candida albicans gene encoding actin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9488. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.22.9488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahajan M, Rohatgi D, Talwar V, Patni S K, Majahan P, Agarwal D S. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of rifampicin at two dose levels in children with tuberculous meningitis. J Commun Dis. 1997;29:269–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus S, Ziv G, Glickman A, Ozbonfil D, Bartoov B, Klein A. Lincomycin and spectinomycin in the treatment of breeding rams with semen contaminated with ureaplasmas. Res Vet Sci. 1994;57:393–394. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGinnis M R, Rinaldi M G. Antifungal drugs: mechanisms of action, drug resistance, susceptibility testing, and assays of activity in biological fluids. In: Lorain V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins Co.; 1986. p. 260. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moskopp D, Lotterer E. Concentrations of albendazole in serum, cerebrospinal fluid and hydatidous brain cyst. Neurosurg Rev. 1993;16:35–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00308610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Proposed standard M27-T. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng T T, Denning D W. Fluconazole resistance in Candida in patients with AIDS: a therapeutic approach. J Infect. 1993;26L:117–125. doi: 10.1016/0163-4453(93)92707-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Opravil M, Joos B, Lüthy R. Levels of dapsone and pyrimethamine in serum during once-weekly dosing for prophylaxis of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and toxoplasmic encephalitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1197–1199. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.5.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersen D, Demertziz S, Freund M, Schumann G. Individualization of 5-fluorocytosine therapy. Chemotherapy. 1994;40:149–156. doi: 10.1159/000239186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfaller M. Epidemiology and control of fungal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19(Suppl. 1):S8–S13. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.supplement_1.s8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pohlenz-Zertuche H O, Brown M P, Gronwall R, Kunkle G A, Merrit K. Serum and skin concentrations after multiple-dose oral administration of trimethoprim-sulfadiazine in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1992;53:1273–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prasad R, DeWergifosse P, Goffeau A, Balzi E. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel gene of Candida albicans, CDR1, conferring multiple resistance to drugs and antifungals. Curr Genet. 1995;27:320–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00352101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubio T T, Miles M V, Lettieri J T, Kuhn R J, Echols R M, Church D A. Pharmacokinetic disposition of sequential intravenous/oral ciprofloxacin in pediatric cystic fibrosis patients with acute pulmonary exacerbation. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:112–117. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199701000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahai J, Gallicano K, Ormsby E, Garber G, Cameron D W. Relationship between body weight, body surface area and serum zidovudine pharmacokinetic parameters in adult, male HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1994;8:793–796. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199406000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanglard D, Ischer F, Monod M, Bille J. Cloning of Candida albicans genes conferring resistance to azole antifungal agents: characterization of CDR2, a new multidrug ABC transporter gene. Microbiology. 1997;143:405–416. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-2-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanglard D, Ischer F, Monod M, Bille J. Susceptibilities of Candida albicans multidrug transporter mutants to various antifungal agents and other metabolic inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2300–2305. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanglard D, Kuchler K, Ischer F, Pagani J-L, Monod M, Bille J. Mechanisms of resistance to azole antifungal agents in Candida albicans isolates from AIDS patients involve specific multidrug transporters. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2378–2386. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitt M, Brown T A, Trumpower B L. A rapid and simple method for preparation of RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3091–3092. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.10.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seelig A. A general pattern for substrate recognition by P-glycoprotein. Eur J Biochem. 1998;251:252–261. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2510252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seidel E A, Koenig S, Polis M A. A dose escalation study to determine the toxicity and maximally tolerated dose of foscarnet. AIDS. 1993;7:941–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seth V, Seth S D, Beotra A, Semwal O P, D’monty V, Mukhopadhya S. Isoniazid and acetylisoniazid kinetics in serum and urine in pulmonary primary complex with intermittent regimen. Indian Pediatr. 1994;31:279–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siau H, Kerridge D. The effect of antifungal drugs in combination on the growth of Candida glabrata in solid and liquid media. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:357–366. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singhal K C, Varshney M K. Effect of simultaneous isoniazid administration on pharmacokinetics parameters of pyrazinamide. J Indian Med Assoc. 1991;89:227–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walsh T J, Whitcomb P, Piscitelli S, Figg W D, Hill S, Chanock S J, Jarosinski P, Gupta R, Pizzo P A. Safety, tolerance, and pharmacokinetics of amphotericin B lipid complex in children with hepatosplenic candidiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1944–1948. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White T C, Bowden R A, Marr K A. Clinical, cellular, and molecular factors that contribute to antifungal drug resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:382–402. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.2.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White T C. Increased mRNA levels of ERG16, CDR, and MDR1 correlate with increases in azole resistance in Candida albicans isolates from a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1482–1487. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]