Abstract

Obesity-associated insulin resistance plays a central role in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. A promising approach to decrease insulin resistance in obesity is to inhibit the protein tyrosine phosphatases that negatively regulate insulin receptor signaling. The low molecular weight protein tyrosine phosphatase (LMPTP) acts as a critical promoter of insulin resistance in obesity by inhibiting phosphorylation of the liver insulin receptor activation motif. Here we report development of a novel purine-based chemical series of LMPTP inhibitors. These compounds inhibit LMPTP with an uncompetitive mechanism and are highly selective for LMPTP over other protein tyrosine phosphatases. We also report generation of a highly orally bioavailable purine-based analog that reverses obesity-induced diabetes in mice.

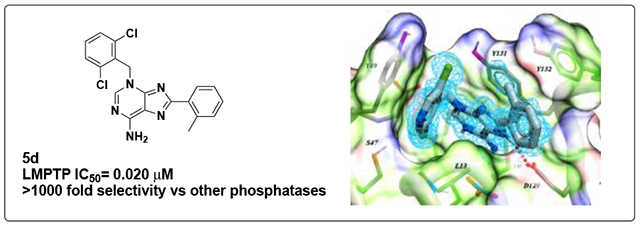

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) respond poorly to insulin, a condition known as insulin resistance1–2. Insulin resistance is the underlying defect at the core of metabolic syndrome/pre-diabetes that can develop into T2DM, and is commonly found in obese and overweight individuals 1–2 Although currently there are multiple anti-diabetic agents available, glycemic control is not sustained in many T2DM patients on these treatments3. Thus, there is a major unmet medical need for insulin-sensitizing agents that would enable improved glycemic control in obese and overweight patients with T2DM.

Once insulin engages the insulin receptor (IR) on the surface of cells, the IR triggers a network of signal transduction path-ways inside the cell through phosphorylation of itself and other substrates4–5. These actions can be reversed by protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) that regulate insulin signaling by dephosphorylating the IR. Thus, a proposed strategy for devel-oping insulin sensitizers has been to target these PTPs6–7. It has long been suggested that targeting the protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B), which dephosphorylates the activation motif of the IR, would relieve insulin resistance and restore glucose tolerance7. However, despite extensive validation of this and other PTPs, several structural features of these enzymes –including a small, highly charged and well-conserved active-site–have rendered them notoriously difficult to drug8. In efforts to overcome this problem, novel approaches are being pursued, such as development of bidentate inhibitors of SH2 domaincontaining phosphatase 2 (SHP2)9 and non-competitive allosteric inhibitors of PTP1B10, SHP211, and lymphoid phosphatase (LYP)12.

Several lines of evidence suggest that the low molecular weight protein tyrosine phosphatase (LMPTP) is a key driver of insulin resistance in obesity. LMPTP is a small (18 kDa), ubiquitously expressed cytosolic PTP encoded by the ACP1 gene13. Among the PTPs, LMPTP and the recently reclassified SSU72 are the only members of the class II subfamily of PTPs14–15. ACP1 encodes two isoforms – LMPTP-A and LMPTP-B –, which are expressed as a result of alternative splicing of the same transcript16. Genetic evidence in humans suggests LMPTP promotes T2DM and insulin resistance, since ACP1 alleles encoding low LMPTP enzymatic activity are associated with lower glycemic levels in diabetic and nondiabetic subjects17–21. Knockdown of LMPTP expression by antisense oligonucleotides was reported to decrease insulin resistance in diet-induced obese (DIO) C57BL/6 (B6) mice and enhance IR phosphorylation in mouse hepatocytes and adipocytes22. Through use of global and tissue-specific LMPTP deletion in mice, we reported that LMPTP drives obesity-induced diabetes through an action on the liver and that LMPTP deletion increases liver IR phosphorylation in response to insulin23.

Since LMPTP inhibitors would be highly valuable for studying the role of LMPTP in insulin resistance and other biological processes, we have sought to develop selective, orally bioavailable LMPTP chemical inhibitors. We previously reported the first orally bioavailable inhibitor of LMPTP activity, compd 23, that alleviates insulin resistance in DIO mice23. Here, we report development of a novel, purine-based chemical series of LMPTP inhibitors that display substantially improved potency over the previously reported series, and maintain high selectivity (>1000-fold) for LMPTP over other PTPs. Enzymatic studies and co-crystallization reveal that these compounds inhibit LMPTP through an uncompetitive mechanism of action by binding at the opening of the active-site pocket. Structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies around this structure led to an orally bioavailable derivative with low nanomolar potency that, upon oral administration to DIO mice, increased liver IR phosphorylation and alleviated diabetes. Our findings reveal a novel chemical structure to inhibit LMPTP that can be utilized for biological studies and potentially for drug development efforts against this target.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of novel LMPTP inhibitor scaffold.

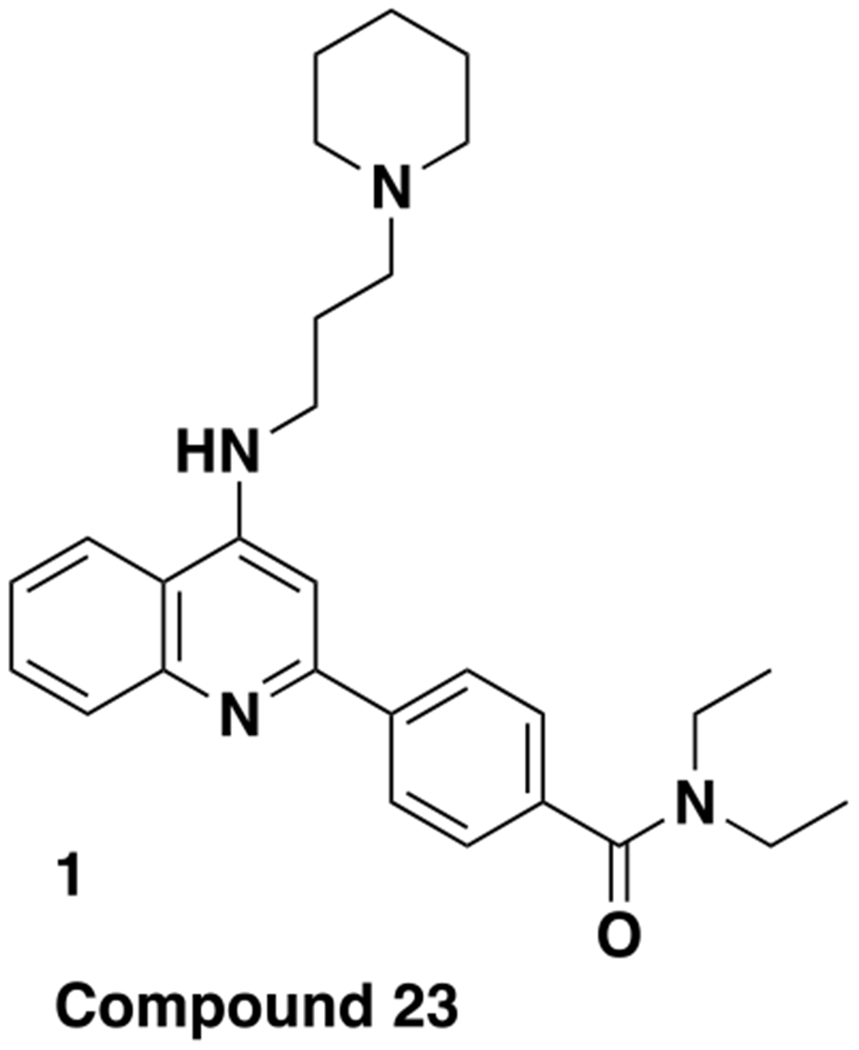

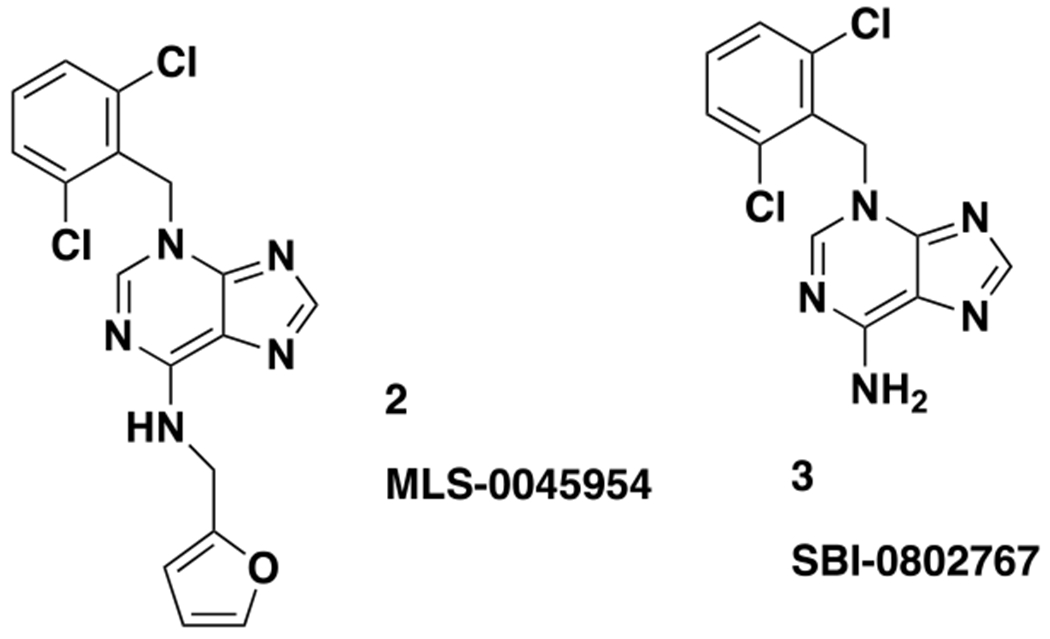

We previously reported a novel chemical series of LMPTP inhibitors, exemplified by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) probe ML400 and orally bioavailable derivative compd 23 (1; Fig. 1)23–24. This series was derived from a quinoline core-based scaffold that emerged from high-throughput screening (HTS) of small-molecule compounds from the NIH Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository23–24. From this HTS, we also identified additional hit MLS-0045954 (2; Fig. 2), which had an unrelated, purine-based scaffold23. Interestingly, LMPTP has previously been reported to be activated by purine biomolecules such as adenine and cyclic guanosine monophosphate13. Since 2 displayed high selectivity for LMPTP over PTPs LYP and vaccinia H1-related phosphatase (VHR) in our HTS workflow23, we decided to explore further development of this scaffold.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of previously reported LMPTP inhibitor compd 23 (1).

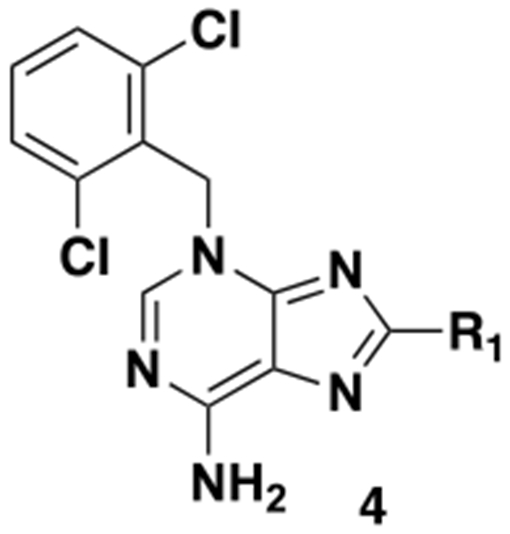

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of purine-based LMPTP inhibitors

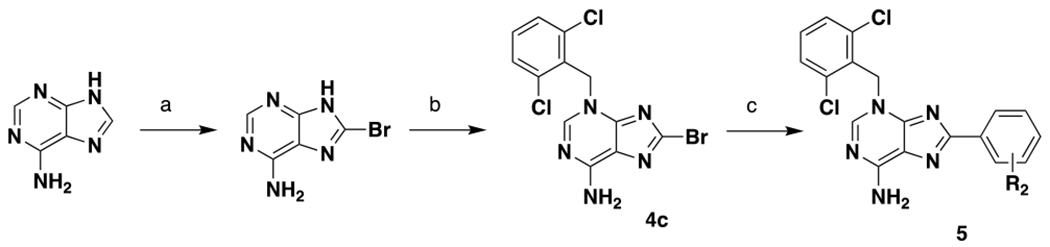

Chemistry.

The compounds described in this paper consist of a purine core structure with an N-linked benzyl group off the 3 position and (in most cases) substitution at the 8 position. A representative synthesis is shown in Scheme 1. Starting from 6-aminopurine, bromination was followed by benzylation to give 4c. In the case of unsubstituted aminopurines, a mixture of benzylation products was obtained, from which intermediates such as 4c could be readily separated albeit in lower yields. For larger scale syntheses, we first protected the free NH2 with a PMB group. Benzylation of the PMB-protected aminopurine proceeded regioselectively and in high yield. Compd 4c could be coupled with the appropriate boronic acid to give a range of final compounds (for full synthetic details see Supporting Information).

Scheme 1.

Representative synthesis of purine compounds aReagents and conditions: (a) Br2. H2O, rt, 60%; (b) K2CO3, DMF, rt, 36%; (c) Pd(dppf)Cl2, dioxane/H2O, 90 °C, 22-55%

SAR.

For our primary SAR-driving assay, we used the same biochemical assay that was deployed for the HTS23. Counterscreens against VHR and LYP were performed routinely; in all cases we saw no cross reactivity. Our preliminary SAR around 2 showed that substitution off the 6-amino group was not preferred (data not shown). Indeed, the unsubstituted 3 was >10 fold more potent than 2 and therefore became our starting point for additional SAR studies (Fig. 2 and Table 1). We assessed the selectivity of 3 against a panel of PTPs, including LMPTP and class I tyrosine-specific and dual-specific PTPs. This compound was remarkably selective for LMPTP, as at a concentration of 40 μM (more than 100X the IC50) no other PTP tested was inhibited by 50% (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Structures and LMPTP activities of analogs 4

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Compd # | R1 | IC50, μMa |

| 3 | H | 0.239 ± 0.053 (72) |

| 4a | −CH3 | 0.306 ± 0.017 (2) |

| 4b | −Ph | 0.104 ± 0.013 (4) |

| 4c | −Br | 17.6 ± 3.3 (2) |

| 4d | −Cl | 27.8 ± 6.8 (2) |

Mean±SEM (n)

We initially focused on exploring substitution off the 8 position (Table 1). Halogens were not well tolerated (4c and 4d). Similar potency to 3 was observed with a methyl group (4a). A significant increase in potency was seen with phenyl substitution (4b), so we therefore decided to fully explore phenyl substitution (Table 2).

Table 2.

Structures and LMPTP activities of analogs 5

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Compd # | R2 | IC50, μMa |

| 5a | 2-Cl | 0.171 ± 0.010 |

| 5b | 3-Cl | 0.380 ± 0.053 |

| 5c | 4-Cl | 0.288 ± 0.008 |

| 5d | 2-CH3 | 0.020 ± 0.005 |

| 5e | 3-CH3 | 0.087 ± 0.003 |

| 5f | 4-CH3 | 0.119 ± 0.014 |

| 5g | 2-F | 0.147 ± 0.037 |

| 5h | 3-F | 0.239 ± 0.008 |

| 5i | 4-F | 0.117 ± 0.008 |

| 5j | 2-OCH3 | 0.106 ± 0.006 |

| 5k | 2-CN | 0.245 ± 0.050 |

Mean±SEM (n=4)

Most phenyl substituents were tolerated, but improved potency over the unsubstituted analog is observed in only one case (the ortho-methyl analog 5d). In general, there is a slight (~2-4 fold) preference for ortho substitution over meta and para (see, for example, 5a vs 5b/c, 5d vs 5e/f and 5g vs 5h) with the exception being the para-fluoro analog 5i.

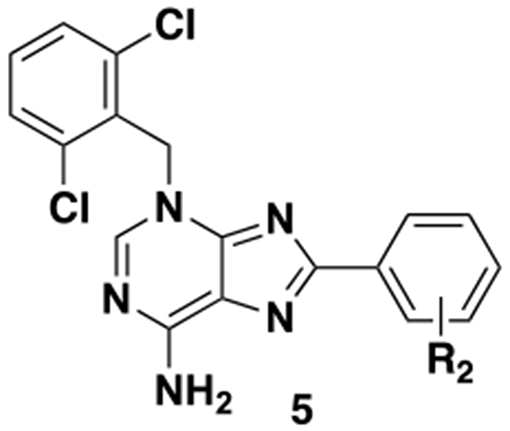

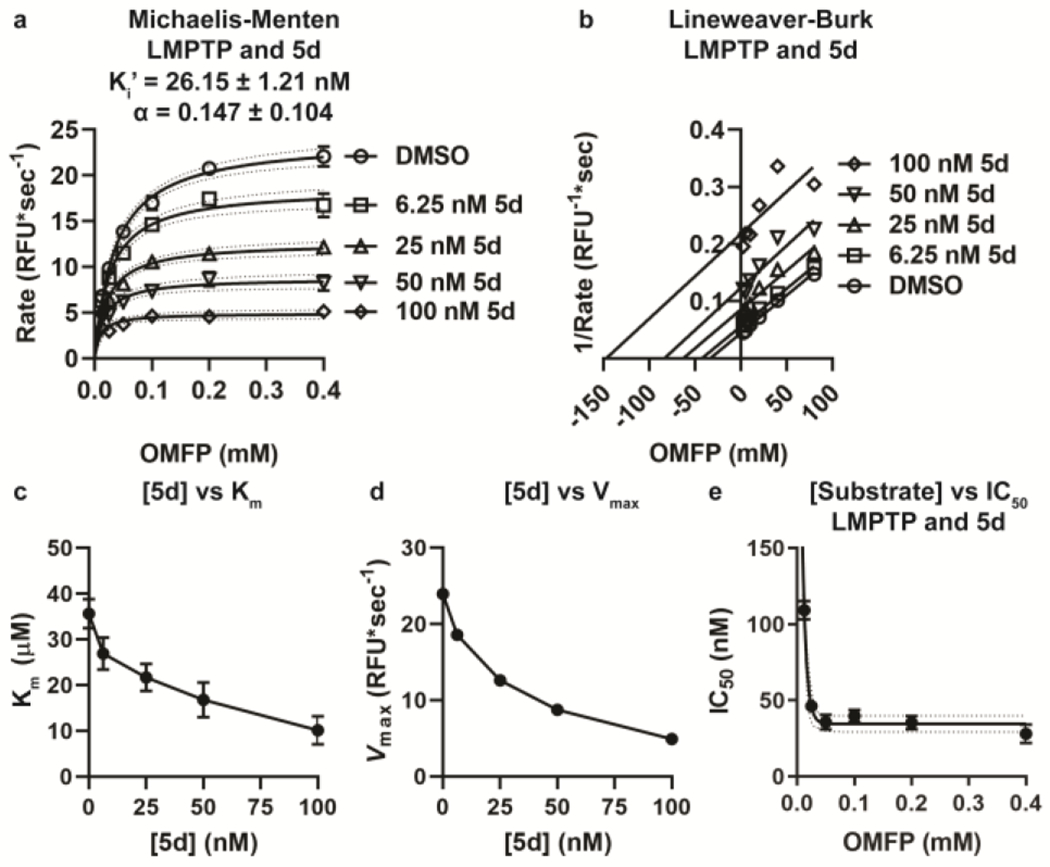

Lastly, we examined substitution of the benzyl substituent off the 3-position (Table 3). 2,6-bisubstitution was highly preferred compared to decreased potency with an unsubstituted ring (6a), mono-Cl derivatives (6b, 6d or 6e) or 2,4-dichloro substitution (6c). 2-6-dimethyl is tolerated (6f) albeit with a 10-fold loss in potency. A wide range of other substitutions was examined with complete loss of LMPTP inhibition in most cases (data not shown). One exception was nitrogen incorporation in the ring (6g), which gives a 3-fold boost in potency. Combining this finding with the ortho-methylphenyl group (6h) gives an additional boost in potency.

Table 3.

Structures and LMPTP activities of analoes 6

|

Mean±SEM (n=4 unless otherwise noted)

We assessed the selectivity profile of 5d, the most potent of the analog 5 compounds. We observed the same remarkable selectivity for LMPTP, even at a concentration of 40 μM 5d) (Supplemental Fig. 2). These data indicate that 5d is >1,000X selective for LMPTP over all other PTPs tested.

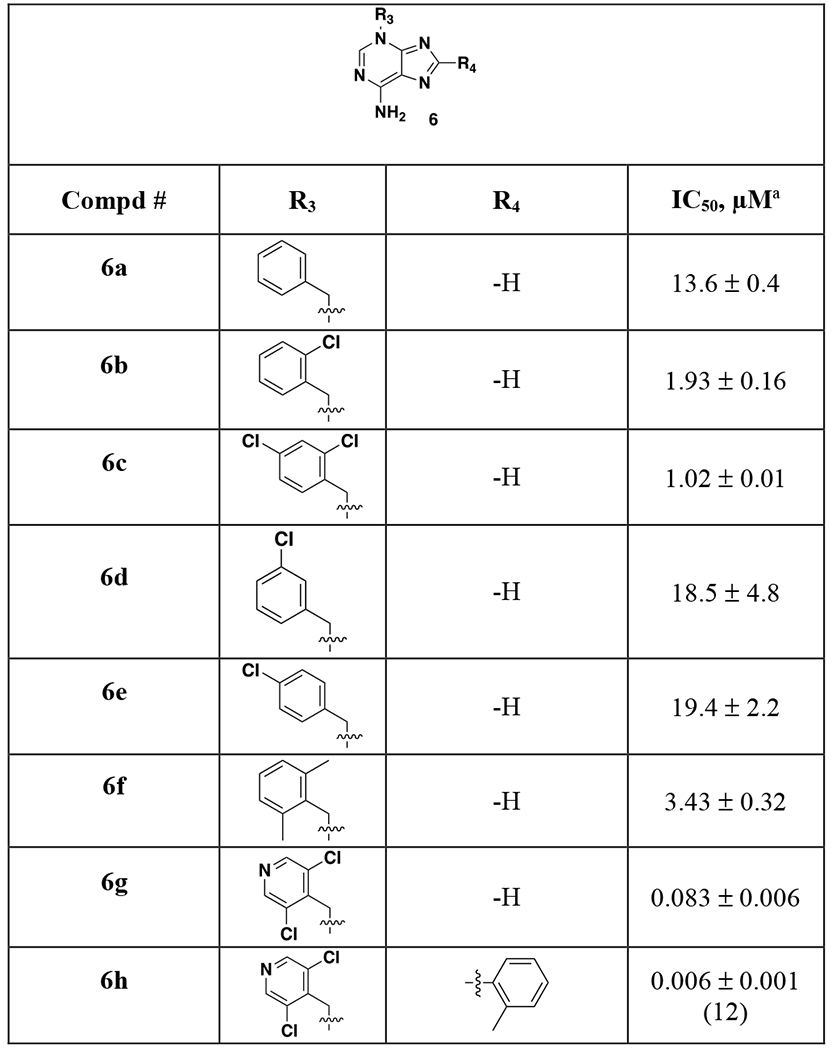

Mechanism of action (MOA).

We examined the inhibitory MOA of 5d on LMPTP using in vitro kinetic analysis in the presence of increasing concentrations of inhibitor. As shown in Fig. 3, our data reveal an uncompetitive mechanism of inhibition. Fitting to a Mixed Model Inhibition equation revealed a higher affinity of 5d for substrate-bound LMPTP than free LMPTP, as evidenced by the Ki’/Ki ratio (μ) of 0.147 ± 0.104, indicative of an uncompetitive binding mechanism (Fig. 3a)25–26. Concomitant with this, Lineweaver-Burk analysis of the data resulted in the parallel plots characteristic of uncompetitive inhibition (Fig. 3b)25–26. In further support of this, hydrolysis of substrate by LMPTP exhibited decreasing Vmax and decreasing Kmin the presence of increasing 5d concentrations (Fig. 3c–d). Finally, since uncompetitive inhibitors exhibit increased inhibitory potency in the presence of increasing substrate27–28, we assessed the potency of 5d at varying substrate concentrations. Consistent with an uncompetitive mechanism, 5d exhibited enhanced potency in the presence of increasing substrate (Fig. 3e).

Figure 3.

Analog 5d inhibits LMPTP with an uncompetitive MOA. (a–b) Activity of 20 nM human LMPTP-A on increasing concentrations of OMFP in the presence of increasing concentrations of 5d. (a) Mean±SEM reaction rate vs. OMFP concentration is shown. Lines show fitting to the Michaelis-Menten equation with 95% confidence interval. Mean±SEM Ki’ and α are shown. (b) Lineweaver-Burk plot of data from (a). Lines show fitting to a linear regression, (c-d) Mean±SEM Km (c) and Vmax (d) values for each concentration of inhibitor from the Michaelis-Menten curves in (a) are shown, (e) IC50 values were calculated for 5d on 20 nM human LMPTP-A-catalyzed hydrolysis of increasing concentrations of OMFP. Mean±SEM IC50 from 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate is shown. Lines show fitting to the one-phase decay equation with 95% confidence interval shown, (a-e) Data from 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate is shown.

Co-crystallization and structure of 5d bound to LMPTP.

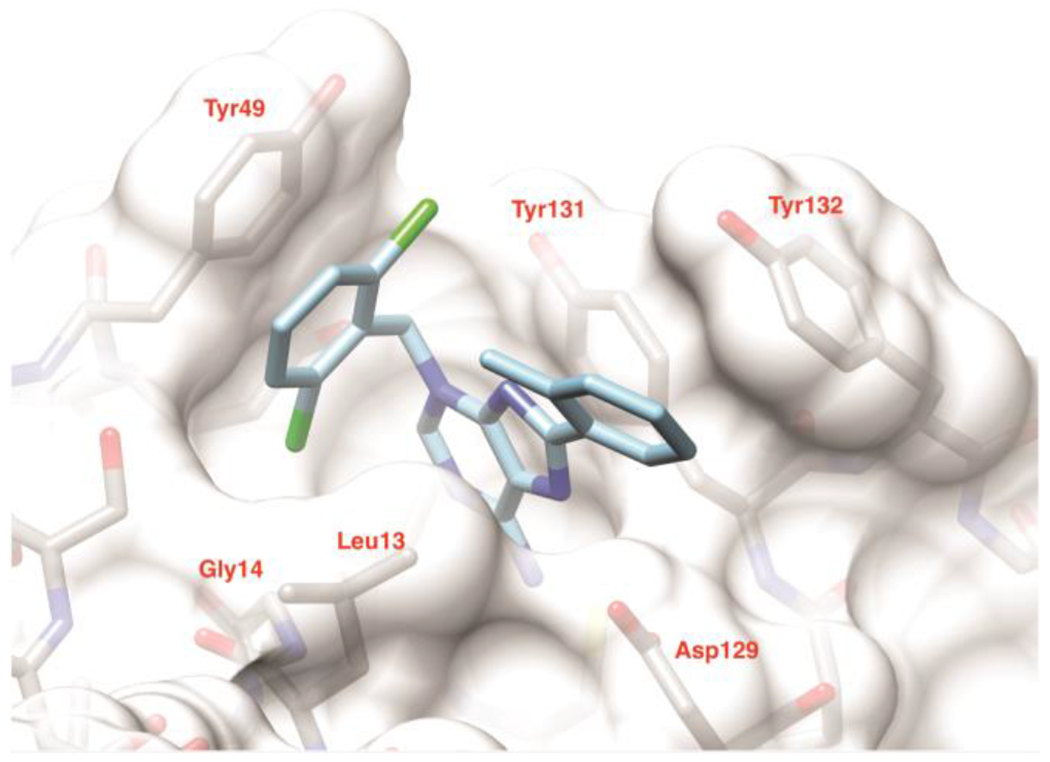

We co-crystallized 5d with human LMPTP and solved the crystal structure of the complex to a resolution of 1.3 Å by molecular replacement. Crystals belong to Space Group P212121 (see Experimental section) with two LMPTP molecules per asymmetric unit, related by a pseudo-dyad. They adopt similar conformations, with a root mean square deviation of 0.86 Å (all atoms) between them. Interpretable electron density was present for 5d and for 155 residues in each of the two molecules, as detailed in the Experimental section. 5d could be unambiguously modeled, except for the o-tolyl group, which exists in two roughly equally populated conformations generated by a rotation of ~60° around the C8-C bond (Supplemental Fig. 3); as for one of them (shown in Fig. 4) two copies could not simultaneously co-exist due to serious steric clashes across the non-crystallographic dyad, it is assumed to be the preferred one in solution and will be used in the discussion below.

Figure 4.

Crystal structure of 5d with human LMPTP. Model of 5d in the substrate binding site of LMPTP. The ligand is shown in light blue. The protein is shown as solvent accessible surface and stick representation (gray). Only one conformation of the o-tolyl group is shown for clarity. The figure was generated using Chimera29. PDB: 7KH8.

Compd 5d binds at the entrance of the catalytic pocket of LMPTP, with its aminopurine moiety approximately occupying the same region of space as the quinoline core in the previous crystal structure of a derivative of compd 18 bound to LMPTP23. When compared to compd 18 (PDB ID 5JNW), the aminopurine system still provides the bulk of the contacts with LMPTP by making a π-π aromatic stacking interaction with the side-chain of Tyr131 on one face, a hydrophobic interaction with Leu13 on the other, and a hydrogen bond with the carboxylate group of Asp129 via its N7; however, the presence of the primary amino group at position 6 adds a second hydrogen bond to the latter interaction (dashed lines in Supplemental Fig. 3). Unlike the aminopropyl piperidine group in 18, the dichlorobenzyl ring binds tightly to a distal part of the active site, lying on a plane perpendicular to that of the purine group and displacing Tyr49 from a position it often occupies in other LMPTP structures. Here, it contributes a novel extensive π-π stacking interaction with the aromatic ring of Tyr49, while one of the chlorine atoms inserts into a pocket formed by Gly14 and the side-chains of Leu13, Ser47, Tyr49, Glu50 and the 5d aminopurine ring (Supplemental Fig. 3), rationalizing the loss of potency upon its removal (Table 3). As expected from the SAR data, and likely as a consequence of constraints imposed by the dichlorobenzyl group, the o-tolyl ring is more solvent exposed or involved in crystal contacts when compared to the cyanophenyl group in 18 (Supplemental Fig. 3). Its interaction with the protein is limited to one edge of the aromatic ring at Van der Waals distance from the side chains of Tyr132 and Asp129. Its methyl group however approaches the face of the dichlorophenyl group at a distance of 3.5 Å, which might explain the preference for ortho-substitution (Table 2). A nitrate ion from the crystallization buffer takes the place of the VO3 group in 5JNW and mimics the presence of a phosphocysteine, consistent with the uncompetitive mechanism we observe (Supplemental Fig. 3). Interestingly, the mode of binding of 5d closely resembles that of the LMPTP activator adenine in the yeast homolog LTP130 but with opposite effects due to a 180° rotation around the axis that runs through the center of the aromatic rings. While the adenine N3 points towards the active site and stabilizes a water molecule that is believed to be the nucleophile that attacks the phosphocysteine intermediate, the rearrangement we see in 5d instead leads N6 to obstruct access to the active site, thus protecting the phosphocysteine from hydrolysis.

Pharmacokinetics (PK).

We examined a range of analogs for their rodent PK properties, with the results for 3, 5d, 6g and 6h shown in Table 4 and the Supporting Information. The compounds without substitution on the 8 position (3 and 6g) showed low to moderate clearance and good oral bioavailability with modest (0.71 hr for 6g) or good (4.71 hr for 3) half-lives. In contrast, the two ortho-methylphenyl analogs (5d and 6h) showed high clearance and modest to low oral bioavailability. In addition, 6g showed only moderate plasma protein binding (88% and 89% bound in human and mouse plasma, respectively) and good microsomal stability (>90% remaining after 1 hr incubation in human and mouse liver microsomes). Due to the combination of potency and bioavailability, 6g was selected for further in vitro and in vivo pharmacological profiling.

Table 4.

Selected mouse PK parameters for compounds

| Compda | Clpb (mL/min/kg) | Vdb (L/kg) | Cmaxc (ng/mL) | AUCc (ng*h/mL) | t1/2c (h) | F% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 3 | 5.8 | 3.01 | 5018 | 18544 | 4.71 | 66 |

| 5d | 69 | 2.75 | 134 | 312 | 1.35 | 19 |

| 6g | 18 | 0.81 | 8220 | 9501 | 0.71 | 100 |

| 6h | 103 | 4.04 | 17 | 38 | 1.55 | 3 |

Compounds dosed 2 mpk IV and 10 mpk PO

IV

PO

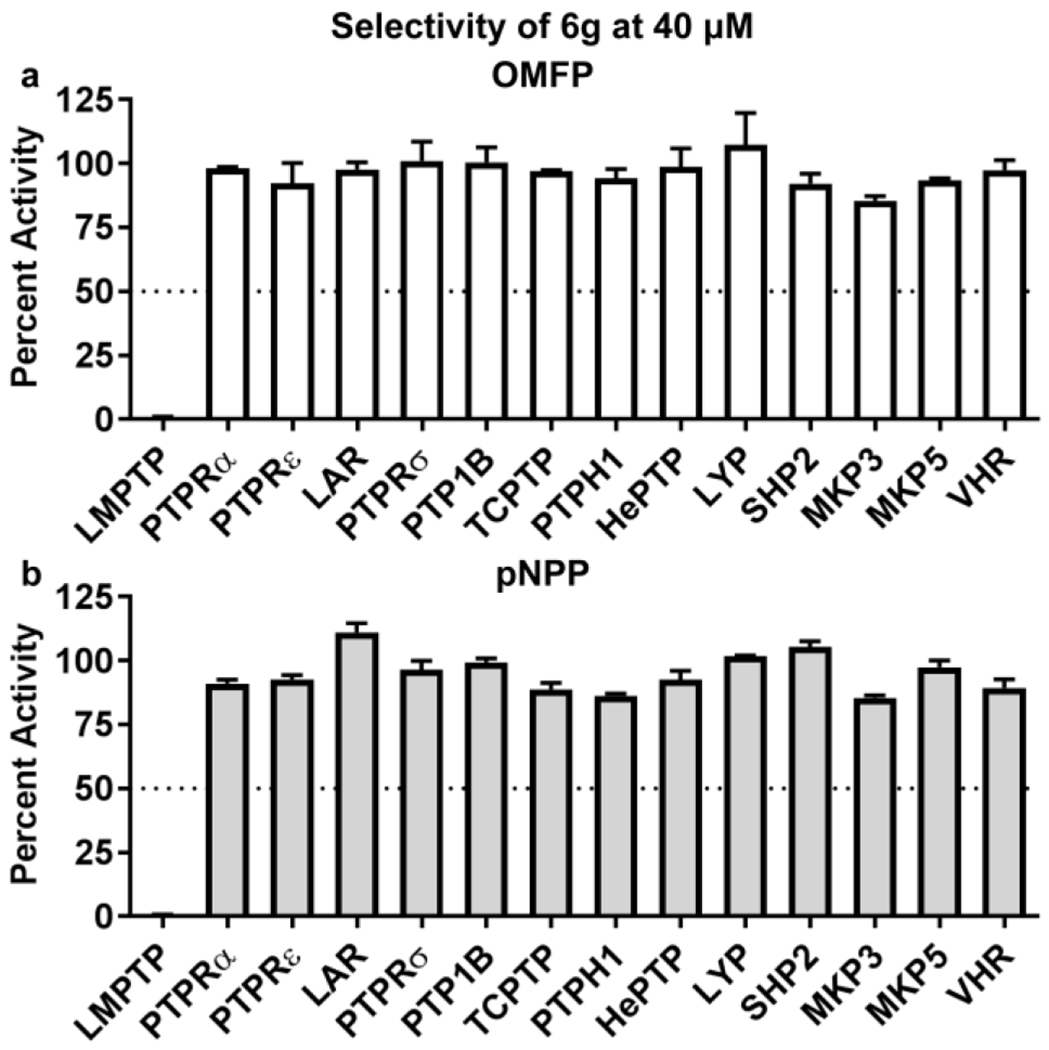

We confirmed that 6g retains high selectivity (Fig. 5) for LMPTP and an uncompetitive mechanism of LMPTP inhibition (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Figure 5.

Selectivity of analog 6g. (a-b) PTPs were incubated with (a) 0.4 mM 3-O-methylfluorescein phosphate (OMFP) or (b) 5 mM para-nitro-phenylphosphate (pNPP) in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 40 μM 6g. Mean±SEM % activity of PTPs incubated with inhibitors compared to DMSO is shown. Dotted line indicates 50% activity. Data from 2 independent experiments perfonned in triplicate is shown.

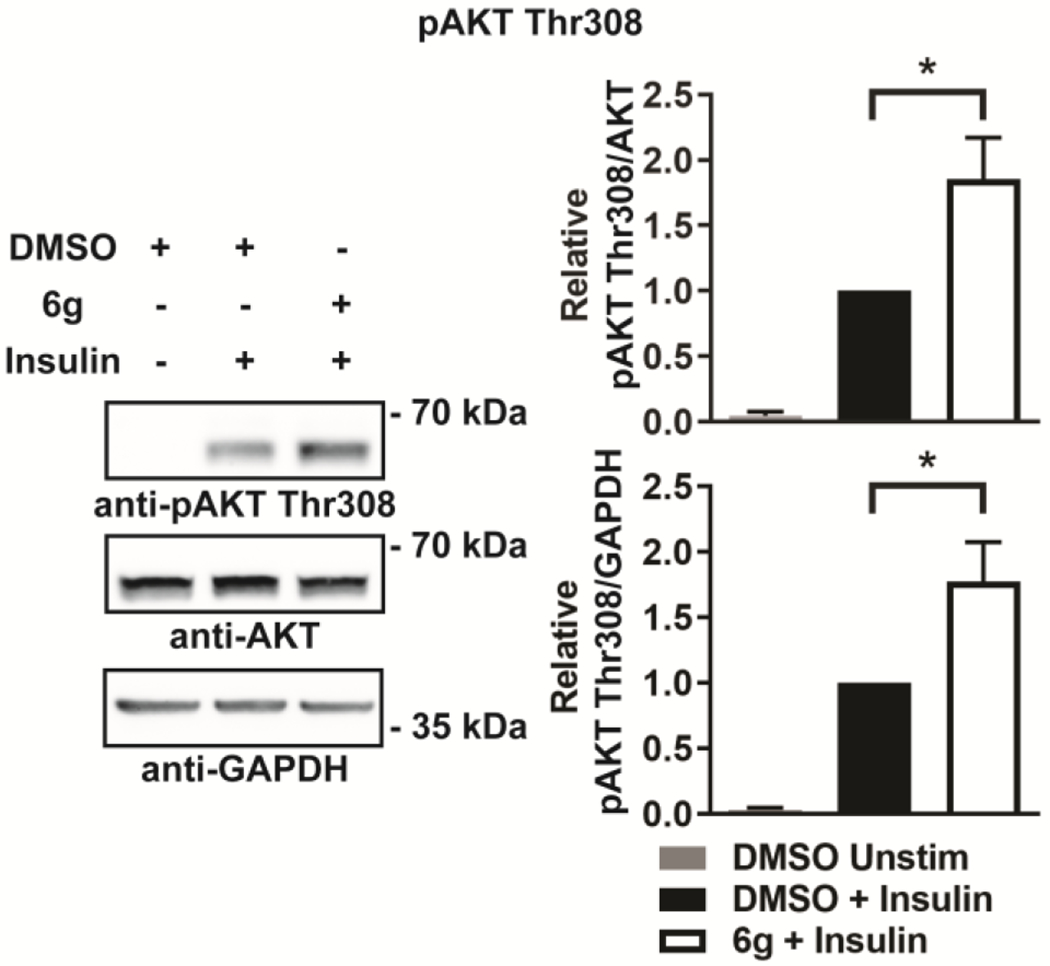

Hepatocyte insulin signaling.

We next examined the efficacy of 6g at inhibiting intracellular LMPTP activity. Since LMPTP inhibits insulin signaling in hepatocytes, we used phosphorylation of IR effector protein kinase B (PKB)/AKT on activating residue Thr308 as a readout for LMPTP inhibition in human HepG2 hepatocytes. Treatment with 500 nM 6g substantially increased HepG2 AKT Thr308 phosphorylation after insulin stimulation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Compd 6g augments insulin-stimulated AKT phosphorylation in hepatocytes. HepG2 hepatocytes were incubated overnight with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 500 nM 6g solubilized in DMSO and stimulated with 10 nM insulin for 5 min or left unstimulated (Unstim). Left, representative Western blots (cropped) of phospho-AKT (pAKT) Thr308 from HepG2 cell homogenates. Right, quantification of pAKT Thr308/AKT and pAKT Thr308/GAPDH from 8 independent experiments. Mean±SEM is shown. *, p<0.05. two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction.

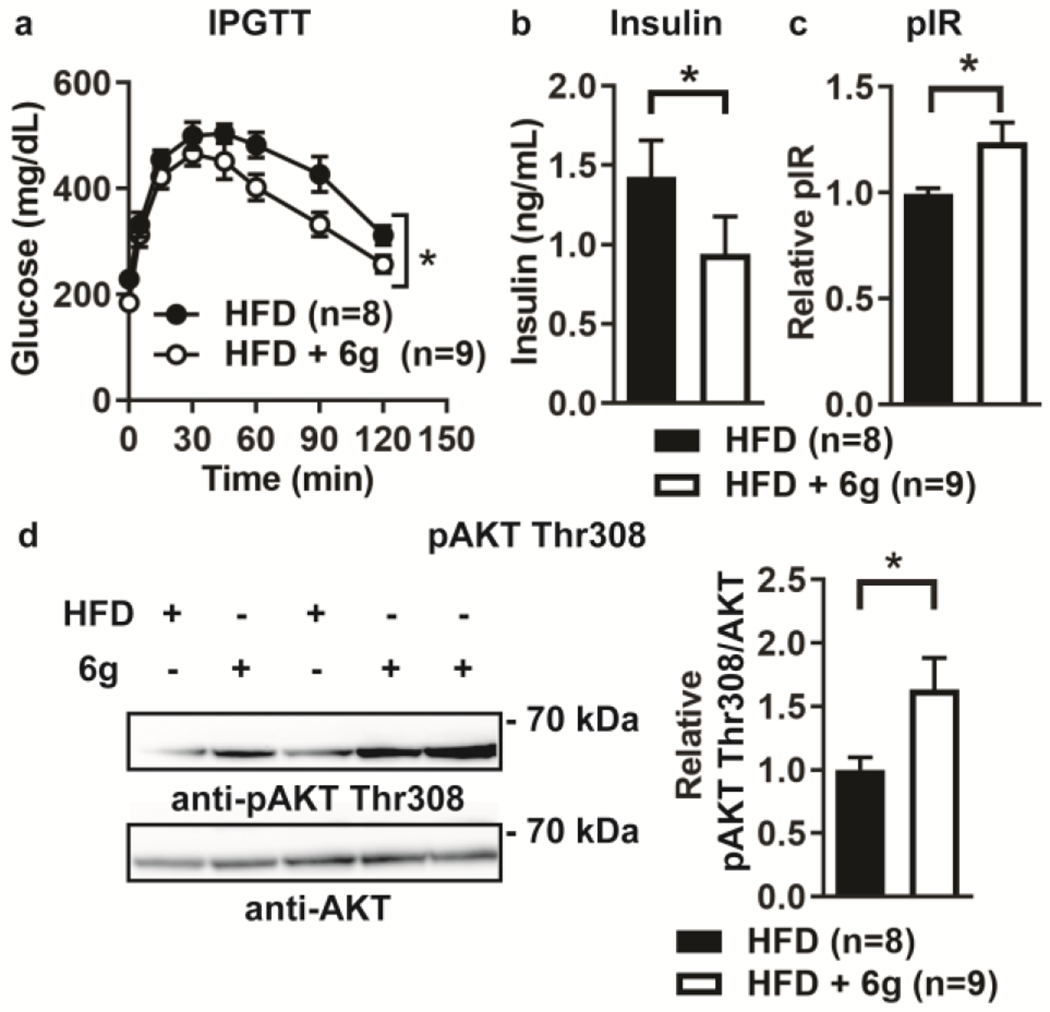

DIO diabetes model.

We next examined whether treatment with 6g would reverse high-fat diet-induced diabetes in mice. We administered 0.03% (roughly equivalent to 30 mg/kg/day) 6g in HFD chow to diabetic DIO mice for 2 weeks and assessed glucose tolerance and fasting insulin levels. Treatment with 6g significantly improved glucose tolerance and decreased fasting insulin levels of diabetic DIO mice (Fig. 7a–b). Concordantly, treatment with 6g also resulted in increased insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of the IR activation motif and increased phosphorylation of AKT Thr308 in the livers of DIO mice (Fig. 7c–d).

Figure 7.

Oral administration of 6g reverses diabetes and enhances liver insulin signaling in obese mice. Diet-induced obese (DIO) male B6 litter-mate mice were treated with 0.03% w/w 6g in high-fat diet or high-fat diet alone for 2 weeks, (a) Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT). (b) Fasting plasma insulin levels of mice as assessed by ELISA, (c-d) Mice were injected intraperitoneally with insulin and livers harvested after 10 min. (c) IR tyrosine phosphorylation in liver homogenates was assessed by phospho-IR (pIR) ELISA, (d) pAKT Thr308 was assessed by Western blotting of liver homogenates. Left, representative Western blots (cropped). Right, quantification of pAKT Thr308/AKT. (a-d) HFD. n=8; HFD + 6g, n=9. Mean±SEM is shown. *, p<0.05: (a) two-way ANOVA, (b) Mann-Whitney test, (c-d) two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we have optimized a series of purine-based LMPTP inhibitors to give potent and orally bioavailable compounds. In this process, we have maintained selectivity for LMPTP against other PTPs and a unique uncompetitive mechanism of action wherein the inhibitor binds to the opening of the LMPTP active-site to block completion of catalysis. This mechanism has not yet been reported for other PTPs. An orally bioavailable compound in this series attenuates insulin resistance and obesity-induced diabetes in mice, further substantiating the importance of LMPTP as a critical driver of insulin resistance and diabetes in obesity and the potential for LMPTP inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for treatment of T2DM.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

All compounds were purified to >95% as determined by LC-MS as well as 1H (and 13C in select cases) NMR and HRMS. Reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise noted. An example of a synthesis is shown below. The analytical methods, general chemistry, experimental information, and syntheses of all other compounds31 are supplied in the Supporting Information.

Synthesis of 8-(4-Chloro-phenyl)-3-(2,6-dichloro-benzyl)-3H-purin-6-ylamine (5c) Step a:

To a mixture of adenine (2.2 g, 16.3 mmol) in water (200 ml) was added bromine (6.0 ml, 17.7 mmol) dropwise at rt. The resulting mixture was then stirred for 2 days at rt. The solvent and volatiles were removed in vacuo. The residue was washed with water (15 mL x2) and ethyl acetate (15 mL x2) to give 8-bromo-9H-purin-6-ylamine (2.1 g, yield: 60.3%) as a yellow solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 8.90 (br, 2H), 8.46 (s, 1H). ESI: calculated for C5H4BrN5 =212.97. Observed m/z [M+H]+= 213.9 Step b: To a solution of 8-bromo-3H-purin-6-ylamine (3.1 g, 14.5 mmol) in DMF (20 mL) was added 1,3-dichloro-2-chloromethyl-benzene (2.8 g, 14.5 mmol) and K2CO3 (4.0 g, 29.0 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature under N2 overnight. Solvent was removed under vacuum. The residue was slurried with water (10 mL x3) and MeOH (10 mL x3), filtered and dried under vacuum to give 8-bromo-3-(2,6-dichloro-benzyl)-3H-purin-6-ylamine (4c) (1.91 g, yield: 36 %) as a yellow solid. ESI: calculated for C12H8BrCl2N5=370.93. Observed m/z [M+H]+= 372.3. Step c: A flask charged with 8-bromo-3-(2,6-dichloro-benzyl)-3H-purin-6-ylamine (100 mg, 0.27 mmol), 4-chlorophenylboronic acid (84.0 mg, 0.54 mmol), K2CO3 (111 mg, 0.81 mmol) and Pd(dppf)Cl2 (~20 mg, 20 % wt) in dioxane (5 mL)/H2O (1 mL) was degassed and filled with N2. The reaction mixture was heated at 90°C for 16 hr. Solvent was removed and the residue was purified by prep-HPLC to give 8-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-(2,6-dichloro-benzyl)-3H-purin-6-ylamine (25.0 mg, yield: 23%) as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 8.22 (s, 1H), 8.15 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 8.05 (brs, 2H), 7.56 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.48-7.43 (m, 3H), 5.78 (s, 2H). HRMS: calculated for C18H12N5Cl3 [M+H]+= 405.6884 Observed m/z [M+H]+ = 405.6881. HPLC Purity: 99%.

Generation of recombinant PTPs.

Recombinant human LMPTP-A was purified as described23. Other PTPs used for selectivity assays were either purified or purchased as described in23.

Enzymatic assays.

Phosphatase assays were performed in buffer containing 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 6.0, 1 mM DTT and 0.01% Triton X-100 at 37°C. For assays conducted with 3-O-methylfluorescein phosphate (OMFP) as substrate, fluorescence was monitored continuously at λex=485 and λem=525 nm. For assays conducted with para-nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP) as substrate, the reaction was stopped by addition of 2X reaction volume of 1 M NaOH, and absorbance was measured at 405 nm. IC50 values were determined from plots of inhibitor concentration versus percentage of enzyme activity. For inhibitor selectivity assays, each PTP was incubated with either 0.4 mM OMFP or 5 mM pNPP in the presence of 40 μM compound or DMSO. Equal units of enzyme activity, comparable to the activity of 20 nM human LMPTP-A, were used.

Crystallization, structure solution and refinement.

Co-crystals of LMPTP 4-157 in complex with 5d grew by the sitting drop vapor diffusion method against a reservoir buffer containing 24-32% PEG 3350, 160 mM KNO3, 100 mM BisTris, pH 5.0. Crystals belong to Space Group P212121 with Unit Cell parameters a=55.0 Å, b=59.0 Å, c=95.1 Å and two molecules per Asymmetric Unit. A native dataset extending to 1.3 Å resolution and >99% complete to 1.4 Å was collected at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource beamline 12-2 and processed using HKL200032. The structure was solved by molecular replacement in PHASER33 with the structure of human LMPTP (PDB ID 5JNR) as the search model. Coot34 and refmace35 were used for manual model building and refinement respectively. The final model contains residues 3-157 and 1-106, 109-157 for molecules A and B, respectively, with 424 solvent molecules and no residues in disallowed regions of the Ramachandran plot as assessed by Rampage36. Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. PDB ID 7KH8.

AKT phosphorylation in HepG2 cells.

Human HepG2 cells (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC] catalog #HB-8065) were cultured in Eagle’s Minimal Essential Medium (ATCC) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were treated with DMSO or 500 nM 6g in serum starvation media (0.1% FBS) overnight, following which cells were stimulated with 10 nM bovine insulin (Sigma) for 5 min at 37°C in the presence of DMSO or 500 nM 6g. For detection of AKT phosphorylation by Western blotting, cells were lysed in 1X Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology; CST) with 1 mM phenylmethyl-sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Lysates were sonicated at 4°C for 15 intervals of 10-15 sec. Insoluble fractions were cleared by centrifugation. Prior to SDS-PAGE, protein concentrations of lysates were assessed using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). Detection of AKT phosphorylation by Western blotting was assessed using anti-pAKT Thr308 (#4056) and anti-panAKT (#4691) antibodies (CST). Western blotting quantification was performed using Imagej. Photo editing was performed using Adobe Photoshop.

Diabetes assessment in DIO mice.

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocol at the University of California, San Diego (#S16098). B6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (JAX #000664) and bred in-house. To generate DIO mice, male littermates were fed HFD chow containing 60 kcal % fat (Research Diets) for 3 months starting at 1-2 months of age. DIO littermates weighing ≥35 g were assigned to treatment (HFD formulated with 0.03% w/w 6g) or control (HFD alone) groups. After 2 weeks of treatment, mice were fasted overnight for 13 hours, and IPGTT was performed by administering 1 g glucose/kg body weight by IP injection. Tail ends were snipped 1 hr before glucose injection. Blood glucose levels were obtained from a small drop of blood from tail snip right before glucose injection and at the indicated time points after glucose injection using a OneTouch glucometer. For insulin levels, mice were fasted overnight for 13 hr and blood was collected from the facial vein. Plasma insulin levels were assessed using the Ultra Sensitive Mouse Insulin ELISA kit (Crystal Chem). To assess liver insulin signaling, fasted mice were injected IP with 10 U insulin (Eli Lilly)/kg body weight, and after 10 min mouse livers were harvested, flash-frozen, and homogenized in 1X Cell Lysis Buffer with 1 mM PMSF. Homogenates were sonicated at 4°C for 10 intervals of 30 sec. Insoluble fractions were cleared by centrifugation. IR tyrosine phosphorylation was assessed using the PathScan Phospho-Insulin Receptor β (Tyrl 150/Tyrl 151) Sandwich ELISA Kit (#7258, CST). AKT Thr308 phosphorylation was assessed by Western blotting as described above.

Statistical analysis.

All linear regressions, non-linear data fitting and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software, α values were determined by fitting of data to a mixed model of inhibition. Ki’ values were determined by fitting of data to an uncompetitive model of inhibition. The two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, and Mann-Whitney test were performed where appropriate as reported in the figure legends. A comparison was considered significant if p was less than 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Funding.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 DK106233 to N.B. and A.B.P. S.M.S. was supported by the American Diabetes Association Pathway to Stop Diabetes Grant 1-15-INI-13.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- ACP1

acid phosphatase 1

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- B6

C57BL/6

- BQL

below the quantification limit

- Cl

drug clearance

- Cmax

peak plasma concentration

- CST

Cell Signaling Technology

- DIEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- Fig

Figure

- HFD

high-fat diet

- HL

half-life

- IP

intraperitoneal

- IPGTT

intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test

- IR

insulin receptor

- LMPTP

low molecular weight protein tyrosine phosphatase

- LYP

lymphoid phosphatase

- MPK

mg/kg

- MRT

mean residence time

- ND

not detected

- OMFP

3-O-methylfluorescein phosphate

- pAKT

phospho-AKT

- pIR

phospho-insulin receptor/phospho-IR

- PKB/AKT

protein kinase B

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- pNPP

para-nitrophenylphosphate

- Prep-TLC

preparative thin layer chromatography

- Prep-HPLC

preparative high performance liquid chromatography

- PTP

protein tyrosine phosphatase

- PTP1B

protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B

- Rsq adj

r-squared adjusted

- SBP

Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute

- SD

standard deviation

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- SHP2

SH2 domain-containing phosphatase 2

- Tlast

time of last measurable concentration

- Tmax

time of maximum plasma concentration

- UCSD

University of California San Diego

- Unstim

unstimulated

- Vdss

volume of distribution (steady-state)

- Vz

volume of distribution (elimination)

- VHR

vaccinia H1-related phosphatase

Footnotes

The authors declare the following competing financial interest: patent applications covering the compounds have been filed by SBP. NB and SMS have equity interests in Nerio Therapeutics, a company that may potentially benefit from the research results, and receive income from the company for consulting. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by the University of California, San Diego in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

DEDICATION

This paper is dedicated to the memory of our friend and colleague Tarmo Roosild (1969-2019), an exceptional scientist and human being.

Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. Supporting Information includes experimental procedures and spectroscopic data for selected compounds and details of the PK studies, MOA and selectivity data for compd 6g, and details of the co-crystal structure (PDF).

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABILITY

Chemistry

Selectivity of 3 & 5d

Crystal Structure of 5d

In Vivo Pharmacokinetics

MOA of 6g

PDB OF NEW CRYSTAL STRUCTURE

The coordinates and diffraction data for the co-crystal structure described in this study have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) with ID 7KH8. Authors will release the atomic coordinates upon article publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saltiel AR, Putting the Brakes on Insulin Signaling. N Engl J Med 2003, 349 2560–2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boucher J; Kleinridders A; Kahn CR, Insulin Receptor Signaling in Normal and Insulin-Resistant States. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein SA; Lamos EM; Davis SN, A Review of the Efficacy and Safety of Oral Antidiabetic Drugs. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2013, 12 153–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saltiel AR; Kahn CR, Insulin Signalling and the Regulation of Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. Nature 2001, 414 799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White MF; Shoelson SE; Keutmann H; Kahn CR, A Cascade of Tyrosine Autophosphorylation in the Beta-Subunit Activates the Phosphotransferase of the Insulin Receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry 1988, 263 2969–2980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musi N; Goodyear LJ, Insulin Resistance and Improvements in Signal Transduction. Endocrine 2006, 29 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson TO; Ermolieff J; Jirousek MR, Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1b Inhibitors for Diabetes. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2002, 1 696–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanford SM; Bottini N, Targeting Tyrosine Phosphatases: Time to End the Stigma. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2017, 38 524–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng LF; Zhang RY; Yu ZH; Li S; Wu L; Gunawan AM; Lane BS; Mali RS; Li X; Chan RJ; Kapur R; Wells CD; Zhang ZY, Therapeutic Potential of Targeting the Oncogenic Shp2 Phosphatase. J Med Chem 2014, 57 6594–6609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan N; Koveal D; Miller DH; Xue B; Akshinthala SD; Kragelj J; Jensen MR; Gauss CM; Page R; Blackledge M; Muthuswamy SK; Peti W; Tonks NK, Targeting the Disordered C Terminus of Ptp1b with an Allosteric Inhibitor. Nature chemical biology 2014,10 558–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerr DL; Haderk R; Bivona TG, Allosteric Shp2 Inhibitors in Cancer: Targeting the Intersection of Ras, Resistance, and the Immune Microenvironment. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2021, 62 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li K; Hou X; Li R; Bi W; Yang F; Chen X; Xiao P; Liu T; Lu T; Zhou Y; Tian Z; Shen Y; Zhang Y; Wang J; Fang H; Sun J; Yu X, Identification and Structure-Function Analyses of an Allosteric Inhibitor of the Tyrosine Phosphatase Ptpn22. The Journal of biological chemistry 2019, 294 8653–8663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caselli A; Paoli P; Santi A; Mugnaioni C; Toti A; Camici G; Cirri P, Low Molecular Weight Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase: Multifaceted Functions of an Evolutionarily Conserved Enzyme. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2016, 1864 1339–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alonso A; Sasin J; Bottini N; Friedberg I; Friedberg I; Osterman A; Godzik A; Hunter T; Dixon J; Mustelin T, Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases in the Human Genome. Cell 2004,117 699–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alonso A; Nunes-Xavier CE; Bayon Y; Pulido R, The Extended Family of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases. Methods Mol Biol 2016, 1447 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magherini F; Giannoni E; Raugei G; Cirri P; Paoli P; Modesti A; Camici G; Ramponi G, Cloning of Murine Low Molecular Weight Phosphotyrosine Protein Phosphatase Cdna: Identification of a New Isoform. FEES letters 1998, 437 263–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lucarini N; Antonacci E; Bottini N; Borgiani P; Faggioni G; Gloria-Bottini F, Phosphotyrosine-Protein-Phosphatase and Diabetic Disorders. Further Studies on the Relationship between Low Molecular Weight Acid Phosphatase Genotype and Degree of Glycemic Control. Dis Markers 1998,14 121–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bottini N; Bottini E; Gloria-Bottini F; Mustelin T, Low-Molecular-Weight Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase and Human Disease: In Search of Biochemical Mechanisms. Archivum immunologiae et therapiae experimentalis 2002, 50 95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gloria-Bottini F; Gerlini G; Lucarini N; Borgiani P; Amante A; La Torre M; Antonacci E; Bottini E, Phosphotyrosine Protein Phosphatases and Diabetic Pregnancy: An Association between Low Molecular Weight Acid Phosphatase and Degree of Glycemic Control. Experientia 1996, 52 340–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iannaccone U; Bergamaschi A; Magrini A; Marino G; Bottini N; Lucarelli P; Bottini E; Gloria-Bottini F, Serum Glucose Concentration and Acp1 Genotype in Healthy Adult Subjects. Metabolism 2005, 54 891–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bottini N; Gloria-Bottini R; Borgiani P; Antonacci E; Lucarelli P; Bottini E, Type 2 Diabetes and the Genetics of Signal Transduction: A Study of Interaction between Adenosine Deaminase and Acid Phosphatase Locus 1 Polymorphisms. Metabolism 2004, 53 995–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pandey SK; Yu XX; Watts LM; Michael MD; Sloop KW; Rivard AR; Leedom TA; Manchem VP; Samadzadeh L; McKay RA; Monia BP; Bhanot S, Reduction of Low Molecular Weight Protein-Tyrosine Phosphatase Expression Improves Hyperglycemia and Insulin Sensitivity in Obese Mice. The Journal of biological chemistry 2007, 282 14291–14299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanford SM; Aleshin AE; Zhang V; Ardecky RJ; Hedrick MP; Zou J; Ganji SR; Bliss MR; Yamamoto F; Bobkov AA; Kiselar J; Liu Y; Cadwell GW; Khare S; Yu J; Barquilla A; Chung TDY; Mustelin T; Schenk S; Bankston LA; Liddington RC; Pinkerton AB; Bottini N, Diabetes Reversal by Inhibition of the Low-Molecular-Weight Tyrosine Phosphatase. Nature chemical biology 2017,13 624–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ardecky RJ; Hedrick MP; Stanford SM; Bliss MR; Zou J; Gosalia P; Yamamoto R; Milewski M; Barron N; Sun Q; Ganji S; Mehta A; Sugarman E; Nguyen K; Vasile S; Suyama E; Mangravita-Novo A; Salaniwal S; Kung P; Smith LH; Sergienko E; Chung TDY; Pinkerton AB; Bottini N, Allosteric Small Molecule Inhibitors of LMPTP. In Probe Reports from the Nih Molecular Libraries Program, Bethesda (MD), 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coussens NP; Sittampalam GS; Guha R; Brimacombe K; Grossman A; Chung TDY; Weidner JR; Riss T; Trask OJ; Auld D; Dahlin JL; Devanaryan V; Foley TL; Mcgee J; Kahl SD; Kales SC; Arkin M; Baell J; Bejcek B; Gal-Edd N; Glicksman M; Haas JV; Iversen PW; Hoeppner M; Lathrop S; Sayers E; Liu HG; Trawick B; Mcvey J; Lemmon VP; Li ZY; McManus O; Minor L; Napper A; Wildey MJ; Pacifici R; Chin WW; Xia MH; Xu X; Lal-Nag M; Hall MD; Michael S; Inglese J; Simeonov A; Austin CP, Assay Guidance Manual: Quantitative Biology and Pharmacology in Preclinical Drug Discovery. Cts-Clin Transl Sci 2018,11 461–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strelow J; Dewe W; Iversen PW; Brooks HB; Radding JA; McGee J; Weidner J, Mechanism of Action Assays for Enzymes. In Assay Guidance Manual,Sittampalam GS; Coussens NP; Nelson H; Arkin M; Auld D; Austin C; Bejcek B; Glicksman M; Inglese J; Iversen PW; Li Z; McGee J; McManus O; Minor L; Napper A; Peltier JM; Riss T; Trask OJ Jr.; Weidner J, Eds. Bethesda (MD), 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ring B; Wrighton SA; Mohutsky M, Reversible Mechanisms of Enzyme Inhibition and Resulting Clinical Significance. Methods Mol Biol 2014,1113 37–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holdgate GA; Meek TD; Grimley RL, Mechanistic Enzymology in Drug Discovery: A Fresh Perspective. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018,17 115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pettersen EF; Goddard TD; Huang CC; Couch GS; Greenblatt DM; Meng EC; Ferrin TE, UCSF Chimera--a Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J Comput Chem 2004, 25 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S; Stauffacher CV; Van Etten RL, Structural and Mechanistic Basis for the Activation of a Low-Molecular Weight Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase by Adenine. Biochemistry 2000, 39 1234–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinkerton AB; Ardecky RJ; Zou J, PCT WO 2019136093 “Preparation of Aminopurine Derivatives as Inhibitors of Low Molecular Weight Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase (LMPTP) and Uses Thereof”. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otwinowski Z; Minor W, Processing of X-Ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. Methods Enzymol 1997,276 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCoy AJ; Grosse-Kunstleve RW; Adams PD; Winn MD; Storoni LC; Read RJ, Phaser Crystallographic Software. Journal of applied crystallography 2007, 40 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emsley P; Lohkamp B; Scott WG; Cowtan K, Features and Development of Coot. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 2010, 66 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murshudov GN; Vagin AA; Dodson EJ, Refinement of Macromolecular Structures by the Maximum-Likelihood Method. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography 1997, 53 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lovell SC; Davis IW; Arendall WB 3rd; de Bakker PI; Word JM; Prisant MG; Richardson JS; Richardson DC, Structure Validation by Calpha Geometry: Phi,Psi and Cbeta Deviation. Proteins 2003, 50 437–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.