Abstract

Background

Community pharmacists are one of the most accessible healthcare providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Whilst playing a vital role in medication supply and patient education, exposure to the pandemic demands and prolonged stressors increase their risk of burnout.

Objectives

Using the Job Demands-Resources model, this study aims to understand the factors that led to community pharmacists’ burnout and to identify their coping strategies and perceived recommendations on interventions to mitigate burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A qualitative phenomenological approach was used with focus groups and interviews of community pharmacists in Qatar who were recruited using purposeful, convenience, and snowballing sampling methods. Interviews were conducted between February and April 2021, were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Using thematic analysis methodology, manual inductive and deductive (based on the model) codes from the interviews were used for synthesis of themes. 11 themes emerged from six focus groups, six dyadic interviews and mini focus groups, and four individual interviews with community pharmacists.

Results

The contributing factors to community pharmacists’ burnout have been identified as practical job demands, and emotional demands including fear of infection. On the other hand, government and workplace-specific resources, personal characteristics such as resiliency and optimism, as well as the implementation of coping strategies, have reduced their stress and burnout.

Conclusions

The use of the Job Demands-Resources model was appropriate to identify the contributing factors to community pharmacists’ burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on these factors, individual, organizational, and national strategies can be implemented to mitigate burnout in community pharmacists during the pandemic and future emergencies.

Keywords: Community pharmacist, COVID-19, Pandemic, Burnout, Stress, Organization

Abbreviations: COVID-19, The Coronavirus Disease-2019; HCPs, healthcare providers; JD-R, Job Demands-Resources

1. Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19), caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020.1 As the virus has spread throughout the world, healthcare providers (HCPs) have been fighting on the frontlines, keeping the overburdened healthcare system afloat and confronting the risk of infection. Facing different demands and challenges can increase the risk of negative mental health consequences in HCPs.2 A systematic review and meta-analysis exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of 33,062 HCPs has reported 23.21% and 22.8% pooled prevalence of anxiety and depression respectively.2

Among healthcare providers at risk of mental health consequences are community pharmacists.3 As one of the most accessible HCPs in the community, the first point of contact in the healthcare system, and being exposed to a high patient influx, community pharmacists have a noticeable and crucial role in times of disasters.3, 4, 5 In fact, experts agree that pharmacists have more than 40 different roles across the disaster management continuum: prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery (PPRR).6 The COVID-19 pandemic is not different. Evidence suggests that community pharmacists are required to support the public, deliver health services, such as minor ailments' triage, and referral, participate in COVID-19 evaluation and vulnerable groups’ identification, public education, infection control implementation, and medications supply.7 , 8

Burnout has been defined by Maslach as a psychological syndrome occurring in response to prolonged exposure to work-related stress.9 It is characterized by emotional exhaustion (i.e., feelings of overextension and depletion of emotional and physical resources), depersonalization (i.e., distant attitudes towards service's clients or work) and reduced self-efficacy or personal accomplishment (i.e., feeling of incompetence or lack of work-related achievement and productivity).7, 8, 9 Burnout is costly to organizations as much as to individuals as it increases employees' turnout and absenteeism and can affect their productivity.10 The counterpart of burnout, referred to as ‘engagement’, is an opposing positive work-related state that has been defined as experiencing vigour, dedication, and absorption.11

The interaction between the two outcomes of burnout and engagement, and the factors from which they originate are explained by the Job Demands-Resources model (JD-R).10 The JD-R is one of several occupational stress models that explore the wellbeing of employees.12 For instance, the Demand-Control model argues that job stress stems from the combined effects of job demands and the responsibility given to the worker to control these demands.13 Alternatively, the Effort-Reward Imbalance model focuses on how strain is the consequence of an imbalance between high efforts exerted and low rewards received at work.14 While these two models explore the occupational factors that can possibly lead to burnout, they are simplistic in that they reduce the complexities of organizations, and hence are rendered inapplicable in various settings, including healthcare organizations.10 On the other hand, the “JD-R model” has been shown to provide an equilibrium between demands and resources. This model states that every occupation has its unique set of physical, psychological, social and/or organizational factors that can affect stress. It also acknowledges personal and individual factors that might affect the outcomes of interest, burnout and engagement. These factors combined can be categorized into the 4 domains: job demands, job resources, personal demands, and personal resources.12 , 15 , 16 By acknowledging all these factors and their consequences, the JD-R model is an overarching model that may be applied to various occupational settings, irrespective of their unique demands and resources12 Additionally, the model can be used to explore burnout in HCPs during COVID-19 and other epidemics, because it can highlight how pandemic-related work demands and other traditional work stressors can lead to health impairment and negative mental health outcomes including burnout.17

Prior to the pandemic, pharmacists have been shown to be at risk of burnout symptoms which are associated with their exposure to demanding job conditions.18, 19, 20 Moreover, during the pandemic, studies have shown that community pharmacists are experiencing negative mental health consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic.21 , 22 However, while the level of burnout was assessed, the factors that have led to burnout were not examined through a theoretically derived framework. Identifying these factors is vital for implementing tailored strategies to prevent negative mental health outcomes in community pharmacists.3 Qatar was impacted by this pandemic when both its public and private medical service centers were diverted to care for COVID-19 patients, with the number of daily cases peaking to 2355 cases in May 2020.23 , 24 Community pharmacists, in turn, were exposed to a new set of challenges where they had to take on the role of educating individuals on COVID-19.25 This study aims to use qualitative methodology to explore burnout in Qatar's community pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic. The objectives of this research are:

-

•

To provide an understanding of the factors that lead to burnout in community pharmacists during the pandemic as explained by the JD-R model

-

•

To identify the coping strategies implemented by community pharmacists to mitigate burnout during the pandemic, and

-

•

To address the factors that contribute to communy pharmacists' burnout during the pandemic by making recommendations on interventions that can mitigate burnout.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This is a research project that utilized qualitative methodology to explore Qatar community pharmacists' experiences and perceptions of burnout resulting from working during the COVID-19 pandemic. Qualitative methodology would allow for a deep understanding of the pharmacists' experiences during this challenging time as compared to a quantitative methodology.26 Using the JD-R model as a theoretical framework, these experiences were utilized to explore factors affecting the pharmacists' burnout. The study originally planned to use focus groups to obtain a deep understanding of the participants' experiences, capitalize on group dynamics, generate rich discussions in a short duration of time, and allow participants to relate and reflect on others’ experiences27 However, only a few participants attended in each scheduled focus group. As a result, in addition to the focus groups (including 4 participants or more), we conducted mini focus groups (3 participants),28 dyadic interviews (2 participants), and individual interviews (one participant each) depending on the number of participating pharmacists. While this was a deviation from the initial plan of solely holding focus groups, the mini-focus groups and dyadic interviews, while hosting a smaller number of participants, still retained the dynamic nature of focus groups.29

2.2. Participants and recruitment

To collect rich and comprehensive data, recruitment of participants was done through a combination of purposeful, convenience, and snowballing sampling methods from various community pharmacies in Qatar.30 To be included in the study, participants were required to be community pharmacists working in Qatar, and to have worked during the pandemic. The participating pharmacists were not offered any incentives for participation. Participants were invited by phone, and were mainly recruited from a population of community pharmacists who had registered their interest in participation in the focus groups/interviews in a survey conducted to assess community pharmacists’ burnout, depression, anxiety, stress, and resilience in Qatar in an earlier study done by the study primary investigator MH, and from a database of community pharmacists obtained from the Ministry of Public Health in Qatar. Since the recruitment process was ongoing as the focus groups and interviews were held, recruited participants were encouraged to invite other colleague pharmacists to participate. The original plan was to recruit 12 to 15 community pharmacists in each focus group to account for possible no-shows and dropouts and to eventually reach the recommended number of 4–8 participants in each focus group.31

2.3. Focus group/interview guide development

The focus group/interview guide was developed ad-hoc based on the JD-R model. While ad-hoc development may create possibility of lowering the methodological rigor of the study, the guide was developed based on a literature review of the JD-R models' domains: job demands and resources, personal demands and resources, and outcomes: burnout and engagement. Additionally, recommendation-specific questions were added to the guide to identify the more significant and pressing issues perceived by pharmacists.32 To consider pandemic-specific factors, previous literature on HCPs’ work during the H1N1 flu virus and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemics was also reviewed.33 , 34

To ensure validity, the interview guide was reviewed by faculty in pharmacy practice with expertise in qualitative research and by a purposive sample of 3 pharmacists. This was followed by pilot interviews with two pharmacists who were excluded from the qualitative phase. Suggested changes were made to the final version of the guide.

Questions within the guide were a mixture of open and closed-ended questions to allow for probing and emergence of themes. The questions’ arrangement in each domain followed a funnel approach; the guide started with a general question, followed by more specific and closed-ended questions.35 (see attached supplementary file: focus group guide).

2.4. Data generation

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and to adhere to social distancing restrictions, all focus groups, and interviews were conducted and recorded through Microsoft Teams™.

Each focus group session/interview was approximately 120 min in duration. Each session involved one to two moderators, and one recorder. The research team included MH: female faculty member and project leader, PharmD degree holder with experience in pharmacy practice research, HM and SA: BSc (Pharm) degree holders and female student researchers. The researchers did not have any established relationships with the participants and have been trained in qualitative research.

Although the use of Microsoft Teams™ platform might come with challenges such as the inability to discern participants' body language and inaudible statements due to connection issues,31 many steps were taken to ensure high engagement between the focus groups’ facilitators and participants. For instance, Microsoft PowerPoint© slideshows were used to display questions and the team members turned on their cameras during each session to add familiarity and comfort. Although participants were encouraged to turn on theirs as well, they were not obligated to. Moreover, this online platform allowed a shared-moderating style including a main moderator asking questions, and another taking notes and asking probing questions.

Sessions were conducted in English, as English is widely used as a communication language in Qatar, transcribed verbatim using Otter® transcribing software with Arabic statements translated into English as per International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures.36 Transcripts were verified by the research team and shared with participants for any potential feedback. Sessions were held until data saturation was reached.37, 38, 39

2.5. Data analysis

Qualitative data analysis was carried out in parallel with data collection. The data from all types of interviews was combined into one data set. Thematic analysis followed a hybrid inductive-deductive approach, using both a set of priori codes (based on the JD-R model and its four domains), and postpriori codes created as analysis went along. This allowed the use of the JD-R model as a theoretical framework while gaining the flexibility of including new codes not included in the model. MAXQDA Analytics Pro® was used for storing and for the process of manually coding the data. The nodes within the program also allowed for visualizing the intersections of codes to further collate them and generate the themes and subthemes.

After transcription, two study investigators (HA and SE) familiarized themselves with the data through multiple reviews of the transcripts and notes. Then, they independently and manually generated codes, and collated them into themes and subthemes while assuring intercoder reliability and dependability.40

Themes and subthemes were compared for similarities and differences between team members and were reviewed by the study principal investigator. Consensus was achieved through consultation. The study results and transcripts were shared with the study participants through email in case they wanted to offer any feedback. No changes were warranted.

The study is conducted and reported in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ).41

Ethical approval

This research was ethically approved by Qatar University's Institutional Review Board (QU-IRB (QU-IRB 1319-EA/20.).

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ demographics

Between February 1st and April 3rd, 2021, a total of 677 community pharmacists were contacted for recruitment and, of those, 135 agreed to participate. 45 pharmacists eventually attended. A total of 6 focus groups, 2 mini focus groups, 4 dyadic interviews and 4 individual interviews were conducted. Table 1 outlines the characteristics of participants.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

| Number of participants | Code | Gender | Country of Origin | Years of experience in Qatar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FG1 | 6 | FG1-01 | Male | India | 12 |

| FG1-02 | Female | India | 5 | ||

| FG1-03 | Male | Egypt | 5 | ||

| FG1-04 | Female | Egypt | 5 | ||

| FG1-06 | Male | India | 1.5 | ||

| FG1-07 | Male | Egypt | 8 | ||

| FG2 |

4 | FG2-01 | Female | Egypt | 7 |

| FG2-02 | Male | India | 23 | ||

| FG2-03 | Female | Egypt | 10 | ||

| FG2-04 | Male | India | 19 | ||

| FG3 | 5 | FG3-01 | Male | India | 1 |

| FG3-02 | Male | Egypt | 15 | ||

| FG3-03 | Male | Egypt | 7 | ||

| FG3-04 | Female | Syria | 3 | ||

| FG3-05 | Male | Egypt | 11 | ||

| FG4 | 4 | FG4-01 | Male | Pakistan | 4 |

| FG4-02 | Male | Egypt | 13 | ||

| FG4-03 | Male | India | 14 | ||

| FG4-04 | Male | India | 10 | ||

| FG5 | 4 | FG5-01 | Male | India | 4 |

| FG5-02 | Male | India | 7 | ||

| FG5-03 | Male | India | 6 | ||

| FG5-04 | Female | India | 5 | ||

| FG6 | 4 | FG6-01 | Male | India | 5 |

| FG6-02 | Male | India | 5 | ||

| FG6-03 | Female | Lebanon | 8 | ||

| FG6-04 | Female | Egypt | 3 | ||

| mFG1 | 3 | mFG1-01 | Male | Sudan | 2 |

| mFG1-02 | Male | India | 6 | ||

| mFG1-03 | Male | India | 6 | ||

| mFG2 | 3 | mFG2-01 | Male | Egypt | 16 |

| mFG2-02 | Male | India | 12 | ||

| mFG2-03 | Female | Egypt | 6 | ||

| D_Int1 | 2 | D_Int1-01 | Female | Egypt | 2 |

| D_Int1-02 | Male | India | 1.5 | ||

| D_Int2 | 2 | D_Int2-01 | Male | India | 5 |

| D_Int2-02 | Male | Egypt | 6 | ||

| D_Int3 | 2 | D_Int3-01 | Male | India | 10 |

| D_Int3-02 | Female | Sudan | 8 | ||

| D_Int4 | 2 | D_Int4-01 | Male | India | 7 |

| D_Int4-02 | Female | Egypt | 3 | ||

| Int1 | 1 | Int1-01 | Male | India | 18 |

| Int2 | 1 | Int2-01 | Female | Jordan | 7 |

| Int3 | 1 | Int3-01 | Female | Egypt | 8 |

| Int4 | 1 | Int4-01 | Male | India | 9 |

“Abbreviations: FG: focus group (4 participants or more), mFG: mini focus group (3 participants), D_Int: dyadic interview (2 participants), Int: interview (1 participant)”.

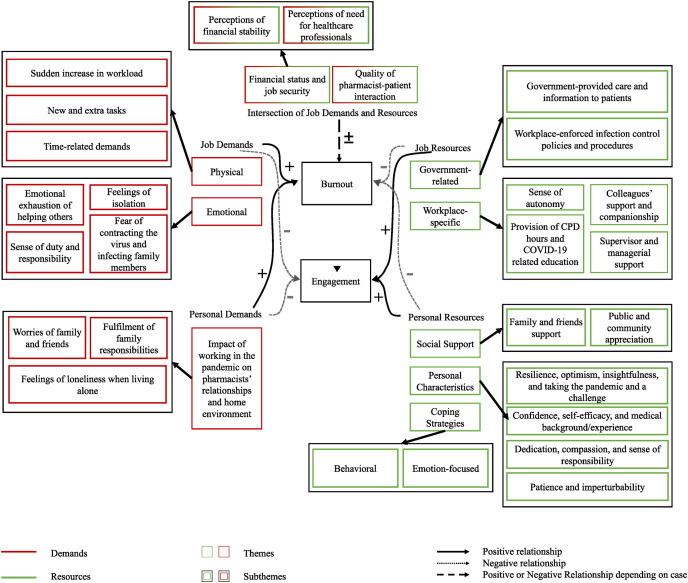

A total of 11 themes emerged with 10 themes mapped to the JD-R model's domains in addition to one theme that highlighted the recommendations made by community pharmacists to mitigate burnout. These themes are summarized in Fig. 1 and Table 2 .

Fig. 1.

Themes imagine based on the JD-R Model.

Table 2.

Themes, Subthemes, and Illustrative Quotes mapped against the JD-R Model.

| Domain | Theme | Subtheme | Quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Job demands | The physical demands on community pharmacists | Sudden increase in pharmacist workload | “Most of the staff are quarantined, and we are doing more work in a single shift. As [other participants] said, the number of patients has increased at the beginning of the pandemic. Whatever they feel, even for small problems, they visit the pharmacy to get medications. They're afraid to go to the hospital. So … compared to [before the pandemic], the number of patients has doubled, or even tripled. At the same time, the number of pharmacy staff has reduced. Together, we have to handle all these patients and we feel more stress. So this has affected our performance and our productivity” - FG6-01 |

| Pharmacist new and extra tasks | “I was from the chosen pharmacists who were handling the home delivery service. And this is not a part of my work here. But this was extra, an extra work for me to run the business.” -FG3-03 | ||

| Time related demands | “Yeah. Many of our colleagues are getting COVID during the pandemic, so we need to make sure we cover them or cover their hours. Other colleagues were trapped outside of the country. So sometimes we work continuously for 10 days or more and sometimes we work for more than 8 h. Of course, this will make us under stress” -mFG1-01 | ||

| The emotional demands of working during the pandemic | Pharmacist feelings of isolation | “I would say … I feel exhausted. When everything was closed, I would say a lot. I mean, the entire mall would be like, dark. And we're in the only place with lights on. you'd feel like, okay, like, you can't even walk around. Like, during, if you take a small break, break to the bathroom, it's just empty. And everyone's like, at home. So when that was going on, I say you feel [exhausted] pretty much every day.” -D_Int1-01 | |

| Pharmacist emotional exhaustion of helping patients | “… And also stress.. for a long time during the pandemic, we dealt with the customers or the patients who were very stressed about the pandemic and they didn't know enough about the pandemic. And we did all.. I think we spent a lot of our power to try to deliver the right information to each one of them.” – D_Int2-02 | ||

| Pharmacist sense of duty and responsibility | “So, you are in a grey area. Do I go or not go? but the power of your responsibility as a healthcare provider would outweigh the concept of being a stay-at-home and take the risk of loss. I want to go home, I will stay at home but for how long? It's not one day or two days or three days; [it's] Unlimited. You are one of the healthcare team. You have to take the risk as well as.. just like doctors in the hospitals you need to be brave and to encourage other pharmacists as well to do the same for you and to approach the patient. So the cycle will be closed and pandemic will be limited from this point. If we are taking the risk, we have to help each other to go out from this area.” -FG3-05 “No, really, it was very, very demanding. As you know, community pharmacy is a self-sustaining organization. It's a commercial organization. So when people come to ask for vitamins, or minerals, they might buy it for the whole family in four or five or six boxes or 10 boxes. But when it came to the pandemic situation, we had to limit the things. So for the first time, in the pharmacy practice, we had to say no to people when they asked for more, so for the first time, in the history of community pharmacy, we had to say no to people, and saying no, for a commercial organization, is a very difficult task.” - Int1-01 |

||

| Pharmacist fear of contracting the virus and infecting their family members | “For us, it's more stress because people don't take care or precautions. [We are] not motivated, because we are afraid that we transmit the virus to our family at home. We want to be safe. Maybe if we deal with any patient, we will get COVID-19. Sometimes if we have patients coming to us with COVID symptoms. Like, they come sneezing, we feel some stress during this moment. Sometimes they … to describe their case, sometimes they cough in out face. It's like, in this situation, we will feel stressed” – mFG2-03 | ||

| Job Resources | Government-related support | Government infection-control-related communications, policies and procedures implemented in the workplace | “We had all the access to sanitizers, masks, and Ehteraz. One big thing was Ehteraz … I want to appreciate our Qatari government for installing Ehteraz because Ehteraz did wonders … this kept people inside their houses also to prevent spreading the infection. So I think this was one of the best things which has happened in the world to control a pandemic. This application has its own role in here. I think everywhere … I am from India, and India also had same applications. But how effective was it? We don't know. But here in Qatar, I feel this app did wonders” - FG2-04 |

| Government-provided care and information to patients | “But here in Qatar, everything is there, Education and giving the information to the public … They implemented a toll-free number for support (24/7) for patients in case they had symptoms for example where they have to go, where they have to test, and when the ambulance will come, which is the nearest healthcare center to go, and a checkup, like this, all information is available 24 h from the government …. the government accepted all people like all nationalities even if they didn't have health cards …” -FG3-01 | ||

| Work-place specific resources and supportive environment | Sense of autonomy due to taking part in decision-making and providing feedback | “Yes, staff safety, was one of few important things in our company. So we were given permission to take our own decisions, whatever we like to do in our pharmacy at that time. … We would suggest to the company, and they will do what we want to. We were given permission to take our own decision to keep ourselves safe.” -FG4-03 | |

| Supervisor and managerial support | “Our managing director, came on a video conference call and he motivated us, and he gave us emergency contact numbers of various doctors, counselling sessions were provided to all things helped us a lot. They gave us mental support during this pandemic, and helped us with coping with burnout”– Int4-01 “You know, when we work hard, and someone comes and just touches our shoulder, yes, that will give us more strength. But working is also completely our responsibility. We also need the money. We are leaving our families and we are staying for this.”-FG5-01 |

||

| Colleagues' support and companionship | “If it wasn't for us taking care of each other, mentally and physically, we would've probably collapsed. But we were giving each other motivation to continue to work hard … All of us one way or another, helping each other get over the stressful time.” -FG6-03 | ||

| Provision of CPD hours and COVID-19 related education | “Yeah, there are many CPD opportunities that were considered a great resource. Because [there are] many public discussions during this period. Many webinars are about COVID, and how to deal with it. For example, COVID in asthmatic patients.… You know more, and try to reflect more on your role, and on how to solve any problem you face with COVID. We didn't know anything about COVID before. We needed information as a healthcare provider, we needed to know for the community … what's wrong and what's is right. We needed also to get information from the perfect source.” -mFG1-01 | ||

| Intersection of job demands and resources | Financial status and job security | Pharmacists' perceptions of their financial stability | “Surely, especially the reduction in salary, but our salary is not too much to take from it.. not big. So when they told us they will not reduce anything or take from our salary anything, we felt comfort.” -Int02-01 |

| Pharmacists' perceptions of need for HCPs | “Our job is there. We felt some insecurity [as] we were afraid to lose our job as a result of the global economic crisis. We've already seen some of our friends and relatives losing their jobs. But [now], career wise, we feel safe; Because we are healthcare providers, we are needed”-FG3-01 | ||

| Quality of pharmacist- patient interactions |

“Yeah, I think that at that time, we had very good relationships with our patients, because they are now depending on us. We are trying to answer their questions and provide out of stock items. We would even call them when items are available to collect them …. and they appreciated that we are trying to help them, that anything they needed, we would make available for them …. I think it minimized our stress a little bit, because of course you would feel happy when someone is telling you ‘thank you very much, you really helped me.’ So it minimized our stress even though we were overstressed.”- FG2-03 “Yeah, I do have many negative experiences to be honest with you. When I tell a patient that, okay, you must go to the doctor, they will sometimes shout on us, you know, "what do you think? that I have COVID? You're asking me to go to the hospital?" … most of the people, will tell you ‘where is Corona?’ we have people that tell you there is no Corona at all. They believe it's just … it's just not real, denying it's there …”-FG5-02 “So actually, it was like, before we were able to get close to the patients when we talk to them. Now, there is a barrier. There is a barrier in between us [and] the patient. So, it is not good. People always feel free to come to us because they could speak with us directly. So this barrier is actually a hindrance for everything. We are actually struggling a lot.”-FG5-04 |

||

| Personal Demands | The impact of working during the pandemic on pharmacists' relationships with others and on their home environment | Worries of pharmacists' family and friends | “My husband, …. has nothing to do with the medical field. He was just like panicking each time a patient came to see me. Whenever I go home, he wants to disinfect me before I get into the house …. I feel like people were always looking at me like I am coming from a place that is full of COVID and I am about to spread it … and my neighbors … the neighbors [they even told] their kids … don't play with her kids. It's a bit difficult” – FG6-03 |

| Pharmacists' fulfilment of their family responsibilities | “Every day, I feel guilty that my son is studying online alone. My daughter is alone in the house because we both work. The father and I and he's there alone ….. it was more stressful than at work. So, this was actually the very hard part for me that I am going to the pharmacy and leaving my kid he is online with his school and he doesn't know how to deal with the teacher or even open his mic or open your camera or just to sit properly and.. and really it was very very hard for us” – FG6-03 | ||

| Feelings of loneliness in pharmacists living alone | “Because I am living alone in this country, I didn't feel I needed to do effort to balance my responsibility. My responsibility is my practice, and my work. But in Egypt I have to support them [my family]. [If I had my family around] I wouldn't be worried for them because they are far away from me, and when I go home, I would find another [family] member talking [to me], and I would tell them what happened in my work. It would've been a different life.” – Int3-01 | ||

| Personal Resources | Social support | Support from family and friends | “No, see, this was one of the good things which happened in everybody's life. You found yourself spending time with your family more. You found everybody sitting and having dinner together, lunch together. You were watching TV together. So, I Think, worldwide, the family values got much better. And this was one of the stress busters. You could share your problems within the family … You had a small talk and you could laugh it off.” -Int01-01 |

| Appreciation from public and community | “From my patients, yeah, they would appreciate what I do … because many people are sitting at home during this pandemic, but you have to do [your job] every day, you have to go your duty … Sometimes when in the beginning of lockdown … when the policeman stopped me, and learnt that I am a pharmacist he prayed to God for me, it was great” – FG4-02 | ||

| Personal characteristics | Resilience, optimism, insightfulness, and taking the pandemic as a challenge | “The choice to stay at home because of fear and because of me not willing to go, wasn't available. I was exhausted, tired. But I have to move on..”– FG3-02 | |

| Confidence, self-efficacy, and having medical background and experience | “See, as a pharmacist, we are the most tolerant of all the people we are great listeners. we are even … we can take pressure, and we are the people who are doing a lot of jobs, right from purchasing, dispensing, then maintaining records. Everything, we are doing. So I think we are more stressed and we are the people who can handle stress better.” -FG2-04 | ||

| Dedication, compassion, and sense of responsibility | “If you said burnout, we had the situation, but we overcame it. It's our utmost duty, it's our conscious duty as a pharmacist, as a fraternity for healthcare, to take care of the customers, especially during the pandemic situation. it is up to us to tutor the patients regarding COVID situations and everything. So I think our consciousness makes us much better and more resilient … Definitely we feel the abrasion and the burnout, but we need to stop it actually … We carry on with satisfaction, the inner gratification that we served the humanity … I think that is the most [important] thing. Yeah, we have felt it. But we have we have come out of this actually” -D_Int2-01 | ||

| Patience, and imperturbability | “I'm very cool. I will not be that much, you know, eagerly waiting for something where … even the critical situation I feel I'm very cool, I'm not that much anxious. So, maybe that coolness … is the one characteristic for me that subsided stress from this COVID situation.” – D_Int3-01 | ||

| Coping strategies | Behavioural coping strategies | “Yeah, there are strategies that we adopted during the current COVID time, normally, I used to do a little bit exercise, during COVID I used to do regular exercise. I also joined with so many people, not only in Qatar, but around the many parts of the world, you know, India, some of the Asians, my friends in UK- everywhere.We created a group, daily, [for a] push up challenge …. So people were watching and they were encouraging each other. So their mood was always, you know, always positive …. I was eating more fruits and vegetables during these sessions. Before, I was not eating much veggies and fruits. …. I feel this was good for us, for the body. You feel more fresh and get more immune. I even tell my colleagues and advise my patients to do the same. Protect yourself, use masks and apply social distancing. So these are the strategies we used. Especially exercise and physical fitness that are the most important to fight against the virus.” -mFG2-02 | |

| Emotion-focused coping strategies | “I am actually in this in this domain, personally, the religion helped me a lot. Islam helped me a lot. It was always a thing which helped me … which pushed me to do good. Whatever we could do, [we did it], like speaking to friends, online video calls, so we switched our group meetings and hangouts to online meetings. These helped us a lot, speaking to our family of patents in India or here. In these situations we need to do whatever we can to keep going during this pandemic and do our job. We told ourselves that [there's] no need to panic, it's.. it's okay, so we can handle it. We are all in this together. We can handle this pandemic. This is what we said to ourselves” -Int4-01 | ||

| Recommendations | Recommendations to reduce burnout on an individual, organizational, and national level | Pharmacists' recommendations to their organizations: emotional support, infection prevention procedures and organizational changes | “We used to get a lot of patients customers and more than usual. So, if we had more than one pharmacist that would have made the situation easier to handle, because we were we were getting a huge crowd inside the pharmacy. The company has to be ready to face any kind of situation like we have to keep enough stock of masks, sanitizers and all the precautionary items, gloves and we have to be ready for the customers.” – D_int4-01 |

| Pharmacists' recommendations to the government: vaccinations, public education, and workplace monitoring | “And I request one thing ma'am, as the vaccine has come, so vaccination should be given to all the medical frontline workers, ma'am. Whether they are in the private or governmental sector. So when we receive this COVID vaccine, we will feel safe, psychologically” -FG5-01 | ||

| Pharmacists' recommendations to their peers: COVID-19 preventative measures and behavioural or emotion-focused coping strategies | “We can't sit at home for a long time like before. We must take caution and increase awareness between people, and at home in our families, and take caution by wearing the masks and gloves.” -FG1-04 “The most important thing is that you love your job. Do it with 100% sincerity, you know, without looking out for results. Results are given are provided by the course of time. And your appreciation also will come as a course of time. But keep yourself motivated for choosing this profession, and then do stress busting meditations every day, or prayers if you can …. These things will help you to keep yourself motivated”- Int01-01 |

3.2. Job demands

Theme 1: The physical demands on community pharmacists.

The pharmacists faced several physical demands during COVID-19 pandemic. They are summarized under the following subthemes:

Subtheme: Sudden increase in pharmacist workload. Pharmacists reported an increase in workload due the high influx of patients to community pharmacies. A contributing factor to this high workload was shortage of personnel. Since COVID-19-response was diverted to medical centers including tertiary, secondary and primary care, and community pharmacists were the main suppliers of medications and consumables (i.e. masks, gloves, and sanitizers), patients were directly accessing community pharmacies to receive medical care.

Subtheme: Pharmacist new and extra tasks. Pharmacists had new and extra tasks outside their scope of practice which increased their workload leading to role ambiguity and stress. These new tasks included telepharmacy services, implementation of precautionary measures within the pharmacy, COVID-19-related public education, and management of patients’ acute and chronic conditions.

Subtheme: Time related demands. The pharmacists added that they experienced increased time-related demands such as time pressures, working overtime, and working extra shifts. Moreover, off-days and vacation days were sacrificed. Pharmacists, again, highlighted that shortage of personnel was a contributing factor for these demands.

Theme 2: The emotional demands of working during the pandemic.

Pharmacists also experienced emotional demands as summarized in the subthemes below:

Subtheme: Pharmacist feelings of isolation. While a total lockdown led most professionals to work from home, pharmacists were of the few healthcare professionals who had to turn up to their physical place of work which increased their feelings of isolation.

Subtheme: Pharmacist emotional exhaustion of helping patients. Pharmacists reported that they experienced emotional exhaustion due to an inability to help patients or provide them with the necessary products, at the beginning of the pandemic. Patients’ stress, panic and fear further exacerbated this emotional exhaustion.

Subtheme: Pharmacist sense of duty and responsibility. Community pharmacists' sense of duty and responsibility and their worries for their organization's operations and profits forced them to push themselves beyond their limits.

Subtheme: Pharmacist fear of contracting the virus and infecting their family members. Pharmacists experienced their fear of getting infected and infecting their family members.

Despite the presence of infection control procedures in place, some pharmacists felt these were not implemented adequately. Increased contact with a high number of patients, and patients’ non-adherence to precautionary measures were all factors aggravating such fears.

3.3. Job resources

Theme 1: Government-related support.

Subtheme: Government infection-control-related communications, policies and procedures implemented in the workplace. Governmental infection control communications, policies and procedures implemented in the workplace decreased the community pharmacists’ stress by reducing the fear factor. Namely, pharmacists praised the Ehteraz application, a governmental contact tracing application which became mandatory for Qatar citizens and residents on May 22nd, 2020.42 , 43

Subtheme: Government-provided care and information to patients. Participants appreciated government-provided public care and education, expressing that it created a ripple effect by decreasing the load on them and eventually decreasing their stress and fear of infection.

Theme 2: Workplace-specific resources and supportive environment.

The presence of a supportive environment and resources in the workplace helped pharmacists in mitigating burnout. These are summarized under the following subthemes.

Subtheme: Sense of autonomy due to taking part in decision making and providing feedback. Working in an environment that encouraged provision of feedback and allowed pharmacists to partake in decision making, including infection control procedures, stimulated a sense of autonomy for pharmacists.

Subtheme: Supervisor and managerial support. Pharmacists’ supervisor support and appreciation helped in coping with stress. For example, one company provided counselling services to its employees. While management appreciation motivated pharmacists, many pharmacists felt that monetary rewards were still needed.

Subtheme: Colleagues’supportand companionship. Pharmacists expressed that having support from colleagues helped in mitigating burnout.

Subtheme: Provision of Continuous Professional Development (CPD) hours and COVID-19 related education. Pharmacists reported that they were offered educational opportunities which helped in coping with the stress.

3.4. Intersection of job demands and resources

Pharmacists identified two factors that were considered to act as both job demands and resources. They are discussed in the themes and subthemes below.

Theme 1: Financial status and job security.

Subtheme: Pharmacists' perceptions of their financial stability. Pharmacists’ perceptions of their financial stability and job security influenced whether these two factors were considered as demands or resources. Pharmacists, who perceived their financial status to be unstable due to inadequate salaries or salary cuts, experienced increased stress. On the other hand, pharmacists who perceived their salaries as stable felt a sense of gratitude, as they compared themselves to other professionals who experienced financial instability.

Subtheme: Pharmacists’ perceptions of need for HCPs. In the initial days of the pandemic, pharmacists were worried about their job security. However, with time, these worries were alleviated due to their realization of the need of HCPs during this pandemic.

Theme 2: Quality of pharmacist-patient interactions.

Pharmacists who had unpleasant patient interactions, patient blame and dissatisfaction, or interacted with patients who did not adhere to precautionary measures had increased levels of stress. On the other hand, pharmacists who had pleasant interactions were motivated to work.

3.5. Personal demands

Theme 1: The impact of working during the pandemic on pharmacists' relationships with others and on their home environment.

Pharmacists’ work during the pandemic impacted their personal lives negatively as shown by the following subthemes.

Subtheme: Worries of pharmacists' family and friends. Pharmacists reported stress and emotional exhaustion because their relatives and friends were worried that they would contract the virus and transmit it to them. Pharmacists also felt isolation and avoidance from friends, who feared contracting the infection from them.

Subtheme: Pharmacists' fulfilment of their family responsibilities. Pharmacists' physical and mental exhaustion affected their relationships with their families and their fulfilment of responsibilities towards them. These demands included decreased physical contact with family members and an inability to be involved in children's schooling or transportation.

Subtheme: Feelings of loneliness for pharmacists living alone. Pharmacists who lived alone expressed that although they did not experience stress because of the fear of infecting those around them, they had increased feelings of loneliness.

3.6. Personal resources

Theme 1: Social Support.

Social support was a personal resource for pharmacists and enabled them to cope. This support included:

Subtheme:Supportfrom family and friends. Community pharmacists’ support from their social circle, including family and friends, helped in coping with the stressors of working during the pandemic.

Subtheme: Appreciation from the public and community. Pharmacists felt that the appreciation that the “white army”, which is the name given to HCPs fighting the pandemic, received during the pandemic, reduced their stress.

Theme 2: Personal characteristics and experience.

Pharmacists identified several factors which helped them cope with pandemic stressors.

Subtheme: Resilience, optimism, insightfulness, and taking the pandemic as a challenge. Those who took the pandemic as a challenge and those who had an insight into the big picture of pain that the pandemic brought, remained optimistic and resilient.

Subtheme: Confidence, self-efficacy, and having medical background and experience. Pharmacists reported that other personal characteristics that they used as a resource to cope were their confidence, and self-efficacy which in turn were boosted by their professional experience.

Subtheme: Dedication, compassion, and sense of responsibility. The pharmacists’ dedication, compassion, and sense of responsibility to patients and to their organizations were also identified as a personal resource that mitigated stress.

Subtheme: Patience, and imperturbability helped in coping. Pharmacists cited patience and imperturbability as characteristics that helped in coping.

Theme 3: Coping strategies.

Subtheme: Behavioural coping strategies. Pharmacists implemented behavioural coping strategies to address the stressors of working during the pandemic. Those strategies were COVID-19-directed such as implementing healthy lifestyles, including exercise and a healthy diet, infection control measures, raising awareness among patients to limit the spread of the virus, and self-education about COVID-19 as lack of information and inability to answer patients’ questions were stressors. Other non-COVID-19 related strategies were distraction by seeking pharmacy practice updates and hobbies.

Subtheme: Emotion-focused coping strategies. Emotion-focused coping strategies were also implemented such as detachment from stressors through distraction by seeking spiritual beliefs, and practices, use of positive affirmations, and use of self-help and counselling services.

3.7. Recommendations to mitigate burnout

Theme 1: Recommendations to reduce burnout on an individual, organizational, and national level.

Pharmacists proposed several recommendations to reduce burnout. These could be implemented on the personal, organizational, and national level.

Subtheme: Pharmacists' recommendations to their organizations. Pharmacists’ recommendations to their organizations included offering support to pharmacists on an emotional level in times of infection, and constantly communicating with pharmacists by providing and receiving feedback. They also recommended logistical resources and support by increasing the number of pharmacy staff, giving pharmacists greater opportunities for breaks and vacations, providing educational opportunities, and establishing separate departments for different pharmacy services including telepharmacy services. Lastly, they emphasized the importance of organizational efforts to implement more adequate infection prevention policies such as glass barriers.

Subtheme: Pharmacists’ recommendations to the government: vaccinations, public education, and workplace monitoring. On a national level, in addition to expressing their eagerness to be included in the vaccination scheme, and their desire for the country to continue educating the public about precautionary measures and vaccinations, pharmacists recommended that the government should educate the public about the rights of HCPs and should monitor organizational implementation of policies and operations.

Subtheme: Pharmacists' recommendations to their peers. Pharmacists’ recommendations to their peers fell into two categories: COVID-19 infection prevention, including self- and public-education about the virus and maintaining precautionary measures; and emotion-focused coping strategies including self-appreciation of pharmacist role in the community and adopting behavioural coping mechanisms including spending time with family, implementing and prioritizing activities that would improve wellbeing, and providing support to colleagues and patients.

4. Discussion

This is one of the first studies that highlighted the intricate experiences of community pharmacists in the front lines and that explored the factors related to burnout using the JD-R model as the theoretical framework.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its burden on the healthcare system has altered the lives and mental health of HCPs, including this study's participants who emphasized the effect of the physical and emotional job demands on burnout. The community pharmacists' sudden increase in workload due to the increased patient-to-pharmacist ratio and time-related demands, left them with no time to rest as they had to forgo their vacations and off-days to fulfil their duties. Those stressors, in turn, resulted in burnout features including physical and emotional exhaustion. Indeed, these findings are in line with those of community pharmacists in other countries who experienced burnout due to urgent and high demand for consumables, prescription medications and counselling.44 Low number of staff was highlighted in this study as a major contributor to job demands in line with a study of hospital HCPs' burnout during the pandemic.45 Precautionary measures, telepharmacy and increased management of patients' medical conditions increased role ambiguity which in turn is known to be an antecedent of burnout.46

A significant emotional demand identified by this study and other HCPs across the globe was fear of infection. Since community pharmacists are the first point of contact for the public with the health system, they are exposed to large numbers of people, some of whom may not adhere to precautionary measures, resulting in a fear of infection. This fear has also been highlighted as a major emotionally taxing demand in other HCPs during the pandemic.17 , 47

Overall, the job demands identified in this study and their relationships with burnout is consistent with that of other studies.14 , 37 , 48 However, the scope of this study did not extend to community pharmacists and their unique role during the pandemic.

In accordance with the JD-R model and previous findings on the buffering effect of job resources on burnout,9 the study results on job resources showed that governmental and organizational initiatives and efforts can mitigate the effects of job demands during the COVID-19 pandemic, alleviating burnout. These findings are not new; In fact, job resources, such as co-worker and supervisor support acted as protective factors from negative outcomes during the Ebola crisis.17 Moreover, counselling services reduced the probability of positively screening for mental health problems during the SARS epidemic.49

Interestingly, the study results highlighted that financial and job security, and the quality of patient interactions acted as either demands or resources. In comparison, 73% of pharmacists who participated in a national survey in Canada,50 experienced harassment from patients during the pandemic.50 This finding is expected as many studies demonstrated that an inappropriate demeanour of customers and patients can prevail in times of stress and uncertainty. This indicates the need for an orientation towards patient engagement as a protective factor from emotional exhaustion.33 Financial and job security were also viewed as either a job demand or a resource. Financial demands such as salary cuts or delays increased pharmacists’ stress and in comparison a study in USA has showed that 16% of 625 surveyed pharmacists experienced salary reduction during the pandemic contributing to their stress.51

Community pharmacists within this study were faced by stressors not only on a professional level but also at a personal level. Working during the pandemic impacted the community pharmacists’ relationships and home environment. On the other hand, although pharmacists who lived alone did not have to face the fear of infecting others, the loneliness and isolation they felt resonated with findings from the SARS epidemic, in which these feelings were factors that contributed to stress in nurses.52 , 53

As for personal resources, social support was provided by the small circle of family and friends, as well as from the public. Although previous studies conducted in medical residents indicated that family support could be a protective factor against burnout,52 it is unclear whether this type of support would be sufficient to mitigate burnout during this pandemic, considering that family worries and fear of infecting them also acted as stressors. The results of this study also showed that while familial support is constantly present, support from friends was conditional for some due to pharmacists being perceived as a source of infection. Learning from previous literature during the SARS epidemic, this feeling of isolation can lead to further psychological distress.54

Coping strategies in various forms were identified through this study as moderators of job demands effects, stress, and burnout. These strategies stemmed from the different demands influencing pharmacists’ stress. For instance, pharmacists mentioned that it would be imperative to implement infection prevention practices and raise awareness as coping mechanisms, since fear of infection had great impact on their mental health. Participants also believed that self- and public-education about COVID-19 would combat the dreadful sense of lack of information, and indirectly reduce the spread of the infection, stress, and burnout. Other strategies included engaging in hobbies or spiritual beliefs and prayers, seeking out counselling sessions or using self-help resources, and using positive affirmations.

4.1. Limitations

One of the limitations of the study was the low response rate since a total of 677 pharmacists were informed about the research but only a total of 45 pharmacists participated. However, the main advantage of focus groups was still present and the rich discussion that resulted from these interviews overcame this limitation.

4.2. Recommendations

The psychological impact of working as a frontline worker during the COVID-19 pandemic has been prominent and therefore strategies must be implemented on various levels. On an individual level, combating the pandemic can be achieved by behavioural coping mechanisms that address the main stressors such as continuing to adhere to precautionary measures to avoid the risk of infection. When such stressors cannot be addressed, the use of emotion-focused coping strategies such as spiritual practices, can be implemented.54

On an organizational level, our results demonstrate that organizations must support pharmacists through adequate staffing and implementation of separate departments for telepharmacy, to combat workload- and time-related demands. Psychological support must also be prioritized and can be provided through access to mental health services and self-help kits.

Finally, national strategies to mitigate burnout in community pharmacists, can be implemented through reducing fear of infection by including community pharmacists in the national vaccination scheme, and raising public awareness about precautionary measures and community pharmacists’ rights.

5. Conclusion

Community pharmacists have undoubtedly been essential front-liners in the COVID-19 pandemic. With their expanded role during this crisis and the sudden changes they have experienced, comes constant stress which, if prolonged enough, can cause burnout. The use of the Job Demands-Resources model in this study has been appropriate to reveal different interacting demands and resources influencing burnout of community pharmacists in Qatar during the pandemic, their coping strategies, and their recommendations to mitigate burnout.

The findings of this study can be used a stepping stone for other studies to identify the correlation and interaction between the job demands and resources, and the outcomes of burnout and engagement. Moreover, the tailored recommendations would improve the well-being of community pharmacists and help form organizational disaster preparedness perspective. Unfortunately, the fact that the pandemic's duration has extended to over a year suggests that even if it ceases to be, its effects can be everlasting. Therefore, future work should also address the long-term mental health consequences on community pharmacists.

Funding

This work was supported by a student grant (grant number QUST-1-CPH-2021-14) from Qatar University Office of Research and Graduate Studies. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of Qatar University.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.WHO. WHO . 2020. Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19.https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., Giannakoulis V.G., Papoutsi E., Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elbeddini A., Wen C.X., Tayefehchamani Y., To A. Mental health issues impacting pharmacists during COVID-19. J. Pharma. Policy Practice. 2020;13(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00252-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hess K., Bach A., Won K., Seed S.M. Community pharmacists roles during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pharm Pract. 2020;15 doi: 10.1177/0897190020980626. Published online December, 897190020980626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ung C.O.L. Community pharmacist in public health emergencies: quick to action against the coronavirus 2019-nCoV outbreak. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020;16(4):583–586. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson K.E., Singleton J.A., Tippett V., Nissen L.M. Defining pharmacists' roles in disasters: a Delphi study. PLoS One. 2019;14(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston K., O'Reilly C.L., Cooper G., Mitchell I. The burden of COVID-19 on pharmacists. J Am Pharmaceut Assoc. 2003;61(2):e61–e64. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2020.10.013. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadogan C.A., Hughes C.M. On the frontline against COVID-19: community pharmacists' contribution during a public health crisis. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):2032–2035. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maslach C., Jackson S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. doi: 10.1002/job.4030020205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chirico F. Job stress models for predicting burnout syndrome: a review. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2016;52(3):443–456. doi: 10.4415/ANN_16_03_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaufeli W. In: Employee Engagement in Theory and Practice. Truss C., Alfes K., Delbridge R., Shantz A., Soane E., editors. 2013. What is engagement? [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakker A.B., Demerouti E. The Job Demands‐Resources model: state of the art. J Manag Psychol. 2007;22(3):309–328. doi: 10.1108/02683940710733115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Jonge J., Dollard M.F., Dormann C., Le Blanc P.M., Houtman I.L.D. The demand-control model: specific demands, specific control, and well-defined groups. Int J Stress Manag. 2000;7(4):269–287. doi: 10.1023/A:1009541929536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegrist J. The Handbook of Stress and Health. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2017. The effort–reward imbalance model; pp. 24–35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waqas M., Anjum Z.U.Z., Basharat N., Anwar F. How personal resources and personal demands help in engaging employees at work? Investigating the Mediating role of Need Based Satisfaction. J. Manage. Sci. 2018;11:144–158. Published online July 6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fletcher D., Sarkar M. Psychological resilience: a review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur Psychol. 2013;18(1):12–23. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Britt T.W., Shuffler M.L., Pegram R.L., et al. Job demands and resources among healthcare professionals during virus pandemics: a review and examination of fluctuations in mental health strain during COVID-19. Appl Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/apps.12304. Published online December 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel S.K., Kelm M.J., Bush P.W., Lee H.J., Ball A.M. Prevalence and risk factors of burnout in community pharmacists. J Am Pharmaceut Assoc. 2021;61(2):145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2020.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durham M.E., Bush P.W., Ball A.M. Evidence of burnout in health-system pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(23 Supplement 4):S93–S100. doi: 10.2146/ajhp170818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calgan Z., Aslan D., Yegenoglu S. Community pharmacists' burnout levels and related factors: an example from Turkey. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(1):92–100. doi: 10.1007/s11096-010-9461-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lange M., Joo S., Couette P.A., de Jaegher S., Joly F., Humbert X. Impact on mental health of the COVID-19 outbreak among community pharmacists during the sanitary lockdown period. Ann Pharm Fr. 2020;78(6):459–463. doi: 10.1016/j.pharma.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin Z., Gregory P. Resilience in the time of pandemic: the experience of community pharmacists during COVID-19. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1867–1875. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.info Worldometers. Qatar COVID cases and deaths. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/qatar/

- 24.Doha News Team. One Year of Covid-19 in Qatar: A Timeline. Doha News. https://www.dohanews.co/one-year-of-covid-19-in-qatar-a-timeline/. Published March 17, 2021. Accessed June 12, 2021.

- 25.ElGeed H., Owusu Y., Abdulrhim S., et al. Evidence of community pharmacists' response preparedness during COVID-19 public health crisis: a cross-sectional study. J. Infect. Develop. Countries. 2021;15:40–50. doi: 10.3855/jidc.13847. 01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neubauer B.E., Witkop C.T., Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(2):90–97. doi: 10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stalmeijer R.E., Mcnaughton N., Van Mook W.N.K.A. Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 91. Med Teach. 2014;36(11):923–939. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.917165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan D. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. second ed. SAGE Publications Inc 10.4135/9781412984287. [DOI]

- 29.Morgan D.L., Eliot S., Lowe R.A., Gorman P. Dyadic interviews as a tool for qualitative evaluation. Am J Eval. 2016;37(1):109–117. doi: 10.1177/1098214015611244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeCarlo M. Scientific Inquiry in Social Work. Open Social Work Education; 2018. 10.2 Sampling in qualitative research.https://scientificinquiryinsocialwork.pressbooks.com/chapter/10-2-sampling-in-qualitative-research/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nyumba T.O., Wilson K., Derrick C.J., Mukherjee N. The use of focus group discussion methodology: insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods Ecol Evol. 2018;9(1):20–32. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bakker A.B., Demerouti E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev Int. 2008;13(3):209–223. doi: 10.1108/13620430810870476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barello S., Caruso R., Palamenghi L., et al. Factors associated with emotional exhaustion in healthcare professionals involved in the COVID-19 pandemic: an application of the job demands-resources model. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. Published online March. 2021;3:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00420-021-01669-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan A.O.M., Huak C.Y. Psychological impact of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on health care workers in a medium size regional general hospital in Singapore. Occup Med (Lond) 2004;54(3):190–196. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqh027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan D. Focus Groups and Social Interaction. 2012. pp. 161–176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wild D., Grove A., Martin M., et al. Principles of Good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8(2):94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hennink M.M., Kaiser B.N., Weber M.B. What influences saturation? Estimating sample sizes in focus group research. Qual Health Res. 2019;29(10):1483–1496. doi: 10.1177/1049732318821692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krueger R., Casey M.A. fifth ed. SAGE Publications Inc; 2021. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research.https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/focus-groups/book243860 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Francis J.J., Johnston M., Robertson C., et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2010;25(10):1229–1245. doi: 10.1080/08870440903194015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups, Int J Qual Health Care. https://academic.oup.com/intqhc/article/19/6/349/1791966#27217737 Oxford Academic, Volume 19 pages 349 - 357. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.EHTERAZ - Apps on Google Play https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.moi.covid19&hl=en&gl=US

- 43.Preventative measures. Government communications Office. https://www.gco.gov.qa/en/preventative-measures/

- 44.Jovičić-Bata J., Pavlović N., Milošević N. Coping with the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study of community pharmacists from Serbia | BMC Health Services Research | Full Text, BMC. https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-021-06327-1 Accessed June 5, 2021, Volume 21 page 304 - 311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Algunmeeyn A., El-Dahiyat F., Altakhineh M.M., Azab M., Babar Z.U.D. Understanding the factors influencing healthcare providers' burnout during the outbreak of COVID-19 in Jordanian hospitals. J. Pharmaceutical Policy Practice. 2020;13(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s40545-020-00262-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bakker A.B., Demerouti E., Sanz-Vergel A.I. Burnout and work engagement: the JD–R approach. Annu. Rev. Org. Psychol. Org Behav. 2014;1(1):389–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morgantini LA, Naha U, Wang H, et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid turnaround global survey. medRxiv. Published online May 22, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.05.17.20101915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Moreno-Jiménez J.E., Blanco-Donoso L.M., Chico-Fernández M., Belda Hofheinz S., Moreno-Jiménez B., Garrosa E. The job demands and resources related to COVID-19 in predicting emotional exhaustion and secondary traumatic stress among health professionals in Spain. Front Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.564036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tam C.W.C., Pang E.P.F., Lam L.C.W., Chiu H.F.K. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in 2003: stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol Med. 2004;34(7):1197–1204. doi: 10.1017/S0033291704002247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.COVID-19: information for pharmacists - English. https://www.pharmacists.ca/advocacy/issues/covid-19-information-for-pharmacists/

- 51.Jones AM, Clark JS, Mohammad RA. Burnout and secondary traumatic stress in health-system pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. Published online February 13, 2021. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxab051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Verweij H., van der Heijden F.M.M.A., van Hooff M.L.M., et al. The contribution of work characteristics, home characteristics and gender to burnout in medical residents. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2017;22(4):803–818. doi: 10.1007/s10459-016-9710-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maunder R.G., Lancee W.J., Rourke S., et al. Factors associated with the psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on nurses and other hospital workers in Toronto. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(6):938–942. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000145673.84698.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gavin B., Hayden J., Adamis D., McNicholas F. Caring for the psychological well-being of healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Ir Med J. 2020;113(4):51–53. https://repository.rcsi.com/articles/journal_contribution/Caring_for_the_psychological_well-being_of_healthcare_workers_in_the_COVID-19_pandemic_crisis_/12866114 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]