Abstract

We have previously described the activity of low-dose clindamycin in extended-interval dosing regimens by determination of bactericidal titer in serum. In this study, we used a one-compartment in vitro dynamic infection model to compare the pharmacodynamics of clindamycin in three intravenous-dosing regimens (600 mg every 8 h [q8h], 300 mg q8h, and 300 mg q12h) against three clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus and two clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Test organisms were added to the central compartment of the model to yield a starting inoculum of 106 CFU/ml. Clindamycin was injected as a bolus into the central compartment at appropriate times over 48 h to simulate the q8h or q12h dosing regimens. Drug-free culture medium was then pumped through the system to mimic a half-life of 2.4 h. At predetermined time points during the experiment, samples were removed from the central compartments for colony count determination and drug concentration analysis. The rates of killing did not significantly differ among the three clindamycin dosing regimens against either S. aureus or S. pneumoniae (P = 0.88 or 0.998, respectively). Likewise, no significant differences in activities were detected among the three regimens against staphylococci (P = 0.677 and 0.667) or pneumococci (P = 0.88 and 0.99). Against an S. aureus isolate exhibiting inducible macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance, none of the three clindamycin regimens prevented regrowth of the resistance phenotype in the model. In this model, clindamycin administered at a low dose in an extended-interval regimen (300 mg q12h) exhibited antibacterial activity equivalent to that of the 300- or 600-mg-q8h regimen.

Despite over 25 years of widespread clinical use, clindamycin retains potent activity against many aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens. Moreover, clindamycin remains the drug of choice for pulmonary infections caused by anaerobic pathogens (3). Since its introduction, the optimal dosing regimen for clindamycin has been a subject of considerable debate. Intravenous clindamycin is typically administered at a dose of 600 mg every 6 to 8 h (q6–8h), although regimens employed in clinical trials have ranged from 300 mg q8h to 1,200 mg q12h for both intra-abdominal and pulmonary infections (17).

Debate regarding the optimal dosing of clindamycin has persisted, in part, because the pharmacodynamic characteristics of this agent have been poorly defined. With an improved understanding of clindamycin pharmacodynamics over the last decade, the necessity of administering relatively large doses (>600 mg) at frequent intervals (q6–8h) has been questioned (1, 14, 17). Time-kill studies of clindamycin against both aerobic gram-positive cocci and anaerobic gram-negative rods have shown that the rate and extent of clindamycin antibacterial activity are maximized as drug concentrations approach one to four times the MIC (13). Clindamycin has also demonstrated a prolonged postantibiotic effect in vitro against a variety of bacterial species (9, 19). Considering these characteristics, it may be feasible to administer relatively lower doses of clindamycin (<600 mg) over extended dosing intervals (8 to 12 h) without loss of efficacy against aerobic or anaerobic bacteria.

Because of their ability to simulate an antibiotic concentration-time profile that occurs in humans, dynamic in vitro models are useful tools for comparing the activities of different doses of antimicrobial agents (4). The purpose of this study was to use an in vitro infection model capable of simulating the pharmacokinetic profiles of intravenous-clindamycin regimens in human serum to evaluate the activities provided by a standard dose (600 mg q8h), a low dose (300 mg q8h), and a low dose in an extended-interval regimen (300 mg q12h) against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae.

(This research was presented at the American College of Clinical Pharmacy Annual Meeting in Phoenix, Ariz., in 1997.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Three clinical strains of S. aureus (23-309-A, 24-C, and 4-A) and one penicillin-intermediate (3-56) (MIC = 0.12 μg/ml) and one penicillin-resistant (4-54) (MIC = 2 μg/ml) isolate of S. pneumoniae were used for experiments performed with the model. All isolates were initially fully susceptible to clindamycin.

Antimicrobial agents.

Analytical-grade clindamycin hydrochloride (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was used to prepare a stock solution (2.7 mg/ml) in sterile water.

Media.

For experiments with S. aureus, cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB; PML Microbiologicals, Wilsonville, Oreg.) was used as the growth medium. For S. pneumoniae, CAMHB supplemented with 5% lysed horse blood (PML Microbiologicals) was used to support growth in the model. Blood agar plates (Remel, Lenexa, Kans.) were used for plating experimental samples for colony count determination.

Susceptibility testing.

The MIC for each isolate was determined prior to, and concurrent with, each experimental run with E-test strips (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) containing clindamycin, erythromycin (for induction and determination of macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B [MLSB] resistance), and penicillin (Fig. 1) (5, 18). MICs were rechecked if regrowth was noted in the model during experimental runs.

FIG. 1.

E-test detection (arrow) of the inducible MLSB resistance of S. aureus 4-A.

In vitro infection model.

A one-compartment in vitro infection model similar to models described previously (4, 11) was used to simulate the pharmacokinetics of clindamycin in human serum. The model consisted of four central glass chambers (250 ml each) containing a magnetic stirbar for continuous mixing and sealed ports for aseptic sampling of the central chamber. These chambers were maintained at 37°C by immersion in a heated water bath. Sterile drug-free CAMHB (S. aureus) or CAMHB supplemented with lysed horse blood (S. pneumoniae) was pumped through the central compartments via a peristaltic pump (Masterflex 7524) at a fixed rate to simulate a 2.4-h half-life (t1/2) in vivo (2). After the desired flow rate was established, a bacterial suspension was prepared from a 24-h culture plate and standardized to a 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard (108 CFU/ml). The standardized suspension was then injected into the central compartments to yield a starting inoculum in each compartment of approximately 106 CFU/ml.

Three intravenous regimens of clindamycin (600 mg q8h, 300 mg q8h, and 300 mg q12h) plus a control regimen (no drug) were simulated with the model. Clindamycin was administered into the central compartment as a bolus to rapidly achieve target steady-state pharmacokinetic parameters (Table 1). To account for the potential reduction of clindamycin activity due to protein binding (78%), a low-dose (22% of 300 mg q12h) regimen was also tested over 48 h and the results were compared to the results of the standard regimens listed above (10).

TABLE 1.

Median MICs for E-test isolates

| Isolate | MIC(s) (μg/ml) of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clindamycin | Erythromycin | Penicillin | |

| S. aureus 4-A | 0.19, >256a | >256a | |

| S. aureus 23-309-A | 0.12 | 0.25 | |

| S. aureus 24-C | 0.12 | 0.25 | |

| S. pneumoniae 3-56 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.12 |

| S. pneumoniae 4-54 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 2.0 |

MIC after clindamycin exposure.

Prior to experimentation, sampling procedures were tested to determine the lower limit of quantitation of samples recovered from the model and the potential of antibiotic carryover during the plating process by a modification of methods proposed by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (15). The lower limit of accurately detectable CFU per milliliter was determined for each isolate by preparing a 0.5 McFarland standardized suspension (108 CFU/ml) in sterile water. These suspensions were then serially diluted to produce bacterial concentrations of approximately 500, 100, 50, and 30 CFU/ml for each isolate. Samples (10 μl) were then removed from each suspension and plated on blood agar plates for colony count determination. Plates were incubated at 37°C, and viable colonies were counted at 24 h. All procedures were performed in quintuplicate. The lower limit of reproducibly detectable CFU per milliliter was defined as the most dilute suspension that enabled viable-colony counting with a reproducibility coefficient of variation of <25%.

Antibiotic carryover experiments were conducted by preparing a standardized suspension (0.5 McFarland) of each isolate as described above. The suspension was then diluted to a standardized inoculum of approximately 103 CFU/ml. A sample (100 μl) of the standardized suspension for each isolate was then added to 900 μl of either sterile water alone or sterile water plus clindamycin (6 or 12 μg/ml), resulting in a starting inoculum of 102 CFU/ml. Immediately following the addition of the bacterial suspension to the aqueous solutions, aliquots (10 and 30 μl) were removed and streaked across blood agar plates for colony count determination. Colonies were counted as described above. All tests were performed in quintuplicate. Antibiotic carryover was defined as a reduction in colony counts from a drug-bacteria suspension of >25% compared to the colony count from a control sample (no drug).

At predetermined time points during each experimental run (0, 2, 4, 8, 10, 12, 16, 24, 26, 30 and 48 h), samples (500 μl) were removed from the central compartment, serially diluted in sterile water, and plated (10 μl) on blood agar plates for colony count determination. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h before colonies were counted. All experiments were run for 48 h to evaluate the effect of multiple-antibiotic dosing. Each experiment was performed in duplicate. Data from duplicate runs were averaged and plotted on a logarithmic scale as CFU per milliliter versus time for each time point. Graphs were then analyzed to characterize bacteriostatic (<99.9% reduction in CFU/ml) or bactericidal (≥99.9% reduction in CFU/ml) reductions by methods proposed by Pearson et al. (16). Additionally, the ratio of the maximum concentration of a drug in serum (Cmax) to the MIC, the ratio of the area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC0–24) to the MIC, and the percentage of time each clindamycin concentration remained above the MIC for each dosing interval were extrapolated from the pharmacokinetic data for each experimental isolate.

Clindamycin assay.

Clindamycin concentrations were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) by previously validated methods (6). The HPLC system consisted of a Waters 717 plus autosampler (Millipore Co.), a Waters 501 HPLC pump, an Alltech Inertsil octyldecyl silane 2 column (150 by 4.6 mm; beads, 5 μm in diameter), a Waters 486 tunable multiwavelength detector, and a CR501 Chromatopac integrator (Shimadzu). The monitor wavelength was set at 204 nm. Samples were diluted in the mobile phase (0.05 M phosphate buffer–acetonitrile–tetrahydrofuran, 76.5:23:0.5 [vol/vol/vol], pH 5.5) and analyzed by direct injection (30 μl) into the HPLC system. Propranolol served as the internal standard. The standard curve of clindamycin covered the range from 0.05 to 20.0 μg/ml.

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

Samples (500 μl) were acquired from the central chambers at 0, 2, 4, 8, 8.5, 16, 24, and 24.5 h during each experimental run for determination of clindamycin concentrations and stored at −70°C until analysis by HPLC. The peak (Cmax), trough (the minimum concentration of the drug in serum), the AUC0–24, and t1/2 were calculated from the concentration-time plot with a noncompartamental model for intravenous bolus administration (WinNonLin Software; Scientific Consulting Inc., Cary, N.C.).

Statistical analysis.

The change in inoculum over 48 h (expressed as the percent reduction in the inoculum from the starting inoculum [time zero]), the time to 99.9% reduction in CFU per milliliter, and the rate of reduction in CFU per milliliter were determined by linear-regression analysis. The rate of killing was defined as the slope of the killing curve from the start of the experiment to the time of maximal reduction in the log10 CFU per milliliter. The changes in inoculum and killing rate were compared between dosing regimens by analysis of variance with Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. For all comparisons, a P value of ≤0.05 indicated statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed with the Sigmastat Statistical Software Package (version 2.0; Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, Calif.).

RESULTS

Susceptibility testing.

Median MICs determined by E-test are presented in Table 1. S. aureus 4-A was retested after demonstrating regrowth (Fig. 2) in the model and was determined to be an inducibly MLSB-resistant isolate for which the clindamycin MIC was >256 μg/ml. MLSB resistance was confirmed by E-test by placing an erythromycin strip next to a clindamycin strip 6 mm apart at the low-concentration ends (0.016 μg/ml) and 25 mm apart at the high-concentration ends (256 μg/ml) (5, 17) (Fig. 1).

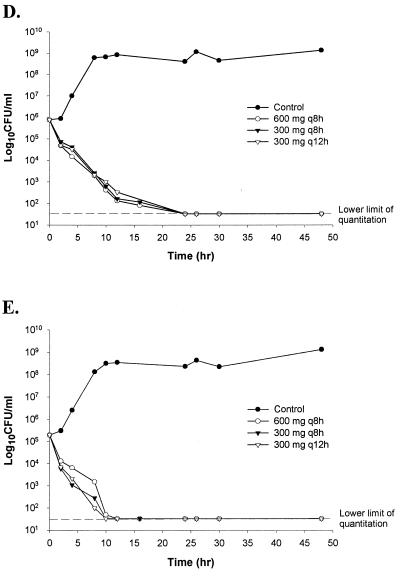

FIG. 2.

Time-kill plots of clindamycin regimens against S. aureus and S. pneumoniae. (A) S. aureus 4-A, exhibiting inducible MLSB resistance; (B) S. aureus 23-309-A; (C) S. aureus 24-C; (D) S. pneumoniae 4-54; (E) S. pneumoniae 3-56.

Clindamycin assay.

The lower limit of detection for clindamycin concentrations was 0.1 μg/ml. Repeated measurements of clindamycin concentrations were reproducible, with mean intraday coefficients of variation for the assay ranging from 2 to 8%.

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

Target and actual pharmacokinetic parameters achieved in the model are presented in Table 2. Overall, the actual pharmacokinetic parameters achieved in the model were similar to target pharmacokinetic parameters.

TABLE 2.

Simulated and actual pharmacokinetic parameters for the in vitro model

| Clindamycin regimen | Simulated (actual) resulta for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (μg/ml) | Cmin (μg/ml) | t1/2 (h) | AUC0–24 (μg · h/ml) | |

| 600 mg q8h | 12.0 (12.3) | 1.0 (1.1) | 2.4 (2.0) | 116 (136) |

| 300 mg q8h | 6.0 (5.4) | 0.5 (1.1) | 2.4 (3.2) | 62 (69) |

| 300 mg q12h | 6.0 (6.2) | 0.25 (0.82) | 2.4 (2.1) | 46 (43) |

Concentrations of total clindamycin. Cmin, minimum concentration of the drug in serum.

Pharmacodynamic analysis.

No antibiotic carryover was noted with the employed sampling methodology. The lowest reproducibly quantifiable concentration of bacteria was 50 CFU/ml. Plots of CFU per milliliter versus time for the three clindamycin regimens against S. aureus 4-A, 23-309-A, and 24-C and S. pneumoniae 3-56 and 4-54 are presented in Fig. 2. Control (no-drug) regimens exhibited a 2-log10-unit increase in CFU per milliliter by 8 h, supporting the viability of both S. aureus and S. pneumoniae in this model. With both Staphylococcus and Streptococcus isolates, clindamycin exhibited bactericidal activity (≥99.9% reduction) in all three regimens. The rates of clindamycin antibacterial activity did not significantly differ among the three dosing regimens for staphylococci or streptococci (Fig. 2B to E) (P = 0.80 or 0.998, respectively). No significant difference was noted among the extents of antibacterial activity in the three regimens against S. aureus 23-309-A and 24-C (Fig. 2B and C) (P = 0.677 and 0.667, respectively), or isolates of S. pneumoniae (Fig. 2D and E) (P = 0.88 and 0.99). None of the three clindamycin regimens prevented regrowth of the MLSB-resistant isolate S. aureus 4-A (Fig. 2A). Similar to results with other regimens, the low-dose regimen that accounted for protein binding of clindamycin (78%) exhibited bactericidal activity at 24 h without regrowth of the test isolates (graph not shown).

Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic parameters achieved in the model are presented in Table 3. All three dosing regimens resulted in clindamycin concentrations that exceeded the MIC for 100% of the dosing interval.

TABLE 3.

Average results for pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic parameters achieved in the in vitro modela

| Organism | Regimen | Cmax/MIC | AUC0–24/MIC | % of dosing interval the clindamycin concn exceeded the MIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus 4-Ab | 600 mg q8h | <0.05 | <0.53 | 0 |

| 300 mg q8h | <0.02 | <0.27 | 0 | |

| 300 mg q12h | <0.02 | <0.17 | 0 | |

| S. aureus 23-309-A | 600 mg q8h | 103 | 1,133 | 100 |

| 300 mg q8h | 45 | 575 | 100 | |

| 300 mg q12h | 52 | 358 | 100 | |

| S. aureus 24-C | 600 mg q8h | 103 | 1,133 | 100 |

| 300 mg q8h | 45 | 575 | 100 | |

| 300 mg q12h | 52 | 358 | 100 | |

| S. pneumoniae 3-56 | 600 mg q8h | 49 | 544 | 100 |

| 300 mg q8h | 22 | 276 | 100 | |

| 300 mg q12h | 25 | 172 | 100 | |

| S. pneumoniae 4-54 | 600 mg q8h | 32 | 358 | 100 |

| 300 mg q8h | 14 | 182 | 100 | |

| 300 mg q12h | 16 | 113 | 100 |

All concentrations were calculated from concentrations of total (protein-bound plus non-protein-bound) clindamycin.

After clindamycin exposure.

DISCUSSION

Reevaluating antimicrobial dosing strategies through the application of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic principles has proven to be beneficial for other older antimicrobials (7). Using an in vitro infection model capable of simulating the concentration profile of clindamycin in human serum in vivo, we demonstrated the equivalency of the activity of a low dose of clindamycin in an extended-interval regimen (300 mg q12h) to the activity of clindamycin dosed at 300 or 600 mg q8h against clindamycin-susceptible S. aureus and S. pneumoniae. Although no single pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic parameter has been proposed as a predictor of efficacy for lincosamide antibiotics, some investigators have suggested that clindamycin concentrations must be maintained above the MIC for the infecting pathogen for greater than 50% of the dosing interval (8). In our model, all three regimens maintained clindamycin concentrations above the MIC for the susceptible bacteria for 100% of the dosing interval (Table 3). The two- to threefold lower Cmax/MIC and AUC/MIC ratios observed with the low-dose, extended-interval regimen did not result in a loss of antibacterial efficacy.

In vivo pharmacokinetic parameters, however, are often more variable than parameters achieved in a controlled in vitro system. Using bactericidal titers in the sera of healthy volunteers, Klepser and colleagues noted that an intravenous clindamycin regimen of 300 mg q12h produced measurable activity in serum for greater than 80% of the dosing interval against both S. pneumoniae and B. fragilis (13). For S. aureus, clindamycin dosed at 300 mg q12h or q8h resulted in bactericidal activity in serum for 50 or 90% of the dosing interval, respectively. Considering the prolonged postantibiotic effect (4 to 6 h) exhibited by clindamycin against staphylococci (9, 18) a 300-mg dose q12h may be adequate for treatment of infections caused by clindamycin-susceptible S. aureus; however, this possibility requires confirmation in vivo.

One unexpected finding of this study was the bactericidal activity (>99.9% reduction in CFU/ml from starting inoculum) exhibited by clindamycin in the model. Lincosamides have been described as both bacteriostatic and bactericidal antibiotics depending on the drug concentration and the MIC for the organism (2). In preliminary time-kill studies performed in our laboratory with the same isolates used in the model (unpublished data), we found clindamycin to exhibit bacteriostatic activity at 24 h even at concentrations of 128 times the MIC. It may be possible that some of the reduction in CFU per milliliter in the model is an artifact of dilution commonly seen with in vitro models (12). Because the model pump settings remained unchanged between the three dosing regimens throughout the experiments, we felt that it was unnecessary to apply a mathematical correction factor to account for this potential artifact. It is important to note that this artifact, whatever effect it may have had on the plots of bacterial killing (Fig. 2), did not obscure the growth of the control or detection of bacterial regrowth of the MLSB-resistance phenotype (Fig. 2A). Moreover, bactericidal activity was noted with even a low-dose regimen that accounted for protein binding of clindamycin.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that, in vitro, clindamycin given at a relatively low dose (300 mg) over extended intervals (q12h) provides antibacterial activity equivalent to those of clindamycin in traditional dosing strategies (300 and 600 mg q8h) against clindamycin-susceptible S. aureus and S. pneumoniae. With its excellent pharmacokinetic profile, availability of an oral formulation, and activity against gram-positive pathogens, clindamycin is likely to remain a useful component of future anti-infective therapy. The potential of using low-dose, extended-interval regimens should be investigated as a means of preserving the efficacy of and potentially lessening the adverse effects associated with this old, yet extremely useful, agent.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Joseph Miller and Lawrence Fleckenstein (University of Iowa College of Pharmacy) for HPLC work during this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ameer B A, Sesin P, Karchmer A W. Selecting clindamycin dosing regimens. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1987;44:2027–2028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Hospital Formulary Service. Clindamycin hydrochloride. In: McEvoy G V, editor. Drug information—1997. Bethesda, Md: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 1997. pp. 388–393. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett J G, Breiman R F, Mandell L A, File T M. Community-acquired pneumonia in adults: guidelines for management. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:811–838. doi: 10.1086/513953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaser J, Zinner S H. In vitro models for the study of antibiotic activities. Prog Drug Res. 1987;31:349–381. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-9289-6_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolmström A, Arvidson S, Ericsson M, Karlsson A. Programs and abstracts of the 28th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1988. A novel technique for direct quantitation of antimicrobial susceptibility testing of microorganisms, abstr. 1209; p. 325. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu-Min L, Chen Y, Yanng T, Hsiech S, Hung M, Lin E T. High performance liquid chromatographic determination of clindamycin in human plasma or serum: application to the bioequivalency study of clindamycin phosphate injections. J Chromatogr B. 1997;696:298–302. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)00241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craig W A. The future—can we learn from the past? Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;27:49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craig W A. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1–12. doi: 10.1086/516284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig W A, Gudmundsson S. Postantibiotic effect. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics and laboratory medicine. 4th ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1996. pp. 296–329. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flaherty J F, Gatti G, White J, Bubp J, Borin M, Gambertoglio J G. Protein binding of clindamycin in sera of patients with AIDS. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1134–1138. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grasson S, Meinardi G, de Carneri I, Tamassia V. New in vitro model to study the effect of antibiotic concentration and rate of elimination on antibacterial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978;13:570–576. doi: 10.1128/aac.13.4.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keil S, Wiedemann B. Mathematical corrections for bacterial loss in pharmacodynamic in vitro dilution models. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1054–1058. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.5.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klepser M E, Banevicius M A, Quintiliani R, Nightingale C H. Characterization of bactericidal activity of clindamycin against Bacteroides fragilis via kill curve methods. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1941–1944. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klepser M E, Nicolau D P, Quintiliani R D, Nightingale C H. Bactericidal activity of low-dose clindamycin administered at 8- and 12-hour intervals against Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Bacteroides fragilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:630–635. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents. Tentative standard M26-T. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearson R D, Steigbigel R T, Davis H T, Chapman S W. Method for reliable determination of minimal lethal antibiotic concentrations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;18:699–708. doi: 10.1128/aac.18.5.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rovers J P, Ilersich A L, Einarson T R. Meta-analysis of parenteral clindamycin dosing regimens. Ann Pharmacother. 1995;29:852–858. doi: 10.1177/106002809502900904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanchez M L, Barrett M S, Jones R N. The E-test applied to susceptibility tests of gonococci, multiply resistant enterococci, and Enterobacteriaceae producing potent beta-lactamases. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;15:459–463. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(92)90090-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xue I B, Davey P G, Phillips G. Variation in the postantibiotic effect of clindamycin against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus and implications for dosing of patients with osteomyelitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1403–1407. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.6.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]