Abstract

We examined partner-seeking and sexual behaviors among a representative sample of U.S. adults (N=1,161) during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Approximately 10% of survey respondents sought a new partner, with age and sexual identity being associated with partner seeking behavior. Approximately 7% of respondents had sex with a new partner, which marks a decrease as compared to a pre-pandemic estimate from 2015 – 2016 in which 16% of U.S. adults reported having sex with a new partner during the past year. Among respondents who had in-person sex with a new partner during the first year of the pandemic, public health guidelines for in-person sexual activity were infrequently followed.

Keywords: Sexual minority, coronavirus, social-distancing, sexual health

Short Summary

A sexual behavior study found that 10% of sampled U.S. adults sought out a new partner during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public health guidelines for in-person sexual activity had low compliance.

The World Health Organization (WHO) characterized the COVID-19 outbreak as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (1). Within days, stay-at-home orders swept across the U.S. to slow the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 (2). Vaccines were not available for most U.S. adults until Spring 2021; thus, during March 2020 – March 2021, COVID-19 prevention measures relied heavily on advising the public to minimize close contacts outside the home (3). This extended period of physical distancing had profound effects on human relationships (4), including romantic and/or sexual partnerships (5). Clinic closures also led to interruptions in sexual health services, including HIV/STD testing and care (6).

In March 2020, the New York City Health Department (NYC HD) released guidance called “Sex and Coronavirus Disease” (7), with an updated version available in June 2020 called “Safer Sex and COVID-19” (8). These documents acknowledged that people would continue to have sex during the extended public health emergency and offered strategies to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission during sex. Within several months, other public health agencies issued similar recommendations for minimizing COVID-19 risks during sex (9, 10). Overall, these guidelines urged the public to discuss precautions and/or get tested for SARS-CoV-2 before in-person sex with someone from outside their household. They also advised precautions during sexual activity with someone from another household, such as washing before/after, avoiding kissing, wearing face masks, and being creative with sexual positions and physical barriers to reduce face-to-face contact.

While a handful of studies across several countries showed a decrease in sexual activity early in the pandemic (5, 11), both in frequency (12, 13) and number of all sexual partners (12), less is understood about how U.S. adults navigated new romantic/sexual partnerships or whether recommended sexual health precautions during the pandemic were put into practice. We examined partner seeking and sexual behavior, including COVID-19 precautions taken, among a representative sample of American adults during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Quantifying the public’s behavior will help understand possible STD prevention implications in the post-COVID era and inform planning around addressing sexual health in the next pandemic. Our survey was administered to 1,161 U.S. adults between February 10 and March 22, 2021, via the National Opinion Research Center’s (NORC) nationally representative, probability-based AmeriSpeak panel (14). Results are presented as weighted percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Additional methodological information is available in the Supplementary Materials.

When asked about existing relationships at the start of the pandemic, 63% (CI: 59–66%) of respondents with a valid response (N=1,152) reported being in a romantic/sexual relationship with a main partnera in mid-March 2020. Higher percentages of middle-aged adults reported main partnerships (30–44 years: 81%, CI: 76–86%; 45–59 years: 74%, CI: 66–80%) as compared to younger (18–29 years: 47%, CI: 38–57%) and older respondents (60+ years: 48%, CI: 41–55%). Of those with a main partnership at the start of the pandemic and a valid survey response (N=741), 87% (CI: 83–89%) reported living with their partner.

Approximately 10% (CI: 8–13%) of respondents (N=1,157) reported seeking/meeting ≥1 new partner(s)b for dating/sex during March 2020-March 2021, with 45% (CI: 33–57%) of those who sought a new partner being respondents who had a main partner at the start of the pandemic vs. 55% (CI: 43–67%) who did not. Respondent demographic information by partner seeking behavior is shown in Table 1. Among respondents who reported kissing or having sex with someone from outside their home during the past month, the mean number of non-household partners kissed during the past month was 2.3 (range: 1–30; median: 1), and the mean number of sexual partners from a different household during the past month was 2.4 (range: 1–100; median: 1).

Table 1.

Weighted prevalence (%) of partner seeking behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic, by respondent characteristics1 — COVID-19 Sexual Behavior Survey2, United States

| A. Respondents who sought out or met a new partner for dating and/or sex during March 2020–March 20213 | B. Respondents who kissed someone that lived outside their home during the past month4 | C. Respondents who had sexual activity5 with someone that lived outside their home during the past month | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | N6 | n | % | CI | P | N | n | % | CI | P | N | n | % | CI | P |

| Sex | 0.538 | 0.199 | 0.616 | ||||||||||||

| Female | 604 | 55 | 9.28 | 6.61—12.87 | 605 | 100 | 16.36 | 12.82—20.65 | 602 | 58 | 9.77 | 7.12—13.27 | |||

| Male | 553 | 67 | 10.74 | 7.71—14.77 | 553 | 88 | 12.94 | 9.83—16.86 | 552 | 58 | 8.66 | 6.03—12.29 | |||

| Age | < 0.001 | 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| 18–29 | 193 | 44 | 24.30 | 16.89—33.65 | 194 | 47 | 23.29 | 16.25—32.22 | 193 | 37 | 18.05 | 11.94—26.35 | |||

| 30–44 | 353 | 52 | 12.20 | 8.63—16.98 | 352 | 67 | 17.18 | 12.72—22.81 | 353 | 52 | 15.30 | 10.88—21.09 | |||

| 45–59 | 273 | 13 | 4.95 | 2.62— 9.16 | 273 | 33 | 10.13 | 6.67—15.09 | 270 | 15 | 3.91 | 2.13— 7.05 | |||

| 60+ | 338 | 13 | 2.36 | 1.17— 4.70 | 339 | 41 | 10.44 | 7.04—15.22 | 338 | 12 | 2.28 | 1.11— 4.63 | |||

| Sexual identity | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Sexual minority7 | 91 | 23 | 26.84 | 16.22—41.01 | 92 | 28 | 34.01 | 21.69—48.96 | 92 | 20 | 22.32 | 12.95—35.70 | |||

| Heterosexual8 | 1061 | 97 | 8.63 | 6.60—11.21 | 1061 | 158 | 13.15 | 10.79—15.95 | 1057 | 95 | 8.25 | 6.33—10.68 | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.139 | 0.552 | 0.234 | ||||||||||||

| Multiple, non-Hispanic | 33 | 5 | 18.20 | 5.99—43.73 | 34 | 9 | 16.87 | 7.22—34.60 | 34 | 3 | 3.78 | 1.01—13.13 | |||

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 21 | 2 | 9.12 | 1.94—33.73 | 21 | 3 | 13.31 | 3.66—38.28 | 20 | 1 | 3.38 | 0.41—23.08 | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 153 | 23 | 9.26 | 5.46—15.25 | 153 | 29 | 14.37 | 8.64—22.97 | 151 | 22 | 12.83 | 7.35—21.46 | |||

| Hispanic | 195 | 25 | 16.31 | 9.74—26.03 | 196 | 35 | 19.03 | 12.68—27.56 | 194 | 26 | 12.45 | 7.54—19.88 | |||

| Other, non-Hispanic | 20 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00— 0.00 | 20 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00— 0.00 | 19 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00— 0.00 | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 735 | 67 | 8.43 | 6.18—11.40 | 734 | 112 | 14.01 | 11.06—17.60 | 736 | 64 | 8.55 | 6.21—11.66 | |||

| Education | 0.735 | 0.259 | 0.214 | ||||||||||||

| Less than HS | 56 | 6 | 12.48 | 4.74—29.00 | 56 | 6 | 9.55 | 3.69—22.52 | 56 | 4 | 3.94 | 1.19—12.19 | |||

| HS grad or equivalent | 192 | 21 | 11.28 | 6.91—17.87 | 193 | 37 | 18.99 | 13.21—26.53 | 192 | 24 | 12.66 | 8.04—19.37 | |||

| Other post-HS training9 | 509 | 64 | 10.48 | 7.82—13.91 | 509 | 91 | 15.09 | 11.83—19.06 | 507 | 55 | 8.95 | 6.50—12.20 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 228 | 17 | 8.75 | 5.03—14.79 | 228 | 30 | 11.49 | 7.53—17.15 | 227 | 16 | 8.78 | 4.82—15.47 | |||

| Post grad | 172 | 14 | 6.73 | 3.53—12.45 | 172 | 24 | 13.79 | 8.51—21.57 | 172 | 17 | 7.52 | 4.21—13.07 | |||

Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

Table shows weighted overall row percentages and corresponding 95% CIs, and P-values based on chi-square tests. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Survey questions available in Supplementary Materials

Data collection occurred during Feb – Mar 2021. Respondents who participated in Feb 2021 provided data for March 2020-Feb 2021; respondents who participated in March 2021 provided data for March 2020–March 2021.

Refers to the month prior to respondent’s survey date

Sexual activity was defined to respondents as oral, vaginal, or anal sex

Totals (N) are not equal across sections (A, B, C) due to missingness

Three separate categories from original questionnaire (“Lesbian or gay”, “bisexual,” or “something else”) were combined due to small sample sizes; the sexual minority category included 44 males and 48 females

Original questionnaire listed this category as “Straight, that is, not lesbian or gay”; category name simplified here for brevity

Original questionnaire listed this category as “Vocational/tech school/some college/ associates”; category name simplified here for brevity

There was a significant negative association between age and partner seeking during the pandemic (i.e., March 2020-March 2021; Table 1A) and with kissing/sex with a new partner during the past month (Table 1B and 1C, respectively). Respondents who identified as anything other than heterosexual (hereafter: sexual minority) were also significantly more likely to seek a new partner during the pandemic (Table 1A) and to kiss or have sex with someone from outside their home during the past month (Table 1B and 1C, respectively). These associations remained after adjusting for sex and age in logistic regressions, which showed that as compared to heterosexual persons, sexual minority persons had 2–3 times the odds of seeking or meeting a new partner outside their home during the pandemic (OR: 2.9, CI: 1.2–6.6, P=0.014), kissing someone outside their home during the past month (OR: 2.7, CI: 1.5–5.0, P=0.001), or having sex with someone outside their home during the past month (OR: 2.3, CI: 1.1–4.7, P=0.026, Supplementary Table 1). An important limitation of this cross-sectional study is that we did not collect behavioral data before the pandemic and therefore cannot quantify temporal changes within or across subgroups. These results should be interpreted cautiously given the small sample of sexual minority respondents in our study (N=92). However, we note our findings support previously raised concerns that stressors associated with social distancing may pose unique challenges for vulnerable populations, such as sexual minorities (11). In light of this and the CDC’s findings that comorbidities associated with severe COVID-19-related illness were more prevalent among sexual minority persons than heterosexual persons (15), further research should focus on how public health efforts can better support sexual minority persons during prolonged periods of social distancing and isolation.

Several reports have demonstrated that virtual dating, phone sex, and consumption of pornography increased across many countries during the early stages of the pandemic (11, 16). Among respondents who sought out or met a new partner during the pandemic (N=122), 70% (CI: 56–80%) reported using online/video platforms, 22% (CI: 13–34%) reported virtual sexual activity, and 83% (CI: 70–91%) reported having at least one in-person meetup. When asked to choose among multiple choice options for duration of time before an in-person meetup, most respondents who met a new partner in person (N=101) reported waiting “several weeks” to do so (34%, CI: 22–47%). Fewer respondents waited “several months” (24%, CI: 15–37%), “several hours” (14%, CI: 7–25%), or “several days” (13%, CI: 8–21%) before meeting a new partner in person; an additional 15% reported not knowing the duration.

Of the 122 respondents who sought out or met a new partner during the pandemic, 68% (CI: 56–79%) reported in-person sexual activity (defined as: kissing, masturbation, oral/anal sex). This equates to approximately 7% (CI: 5–9%) of our total sample (N=1,161) reporting a new partner during the first year of the pandemic. As a pre-pandemic comparison, approximately 16% of US adultsc reported having a new sexual partner in the previous year during 2015–2016 in a nationally representative survey using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (17). Our findings suggest a decrease in the percentage of U.S. adults who had sex with a new partner during the first year of the pandemic as compared to pre-COVID estimates.

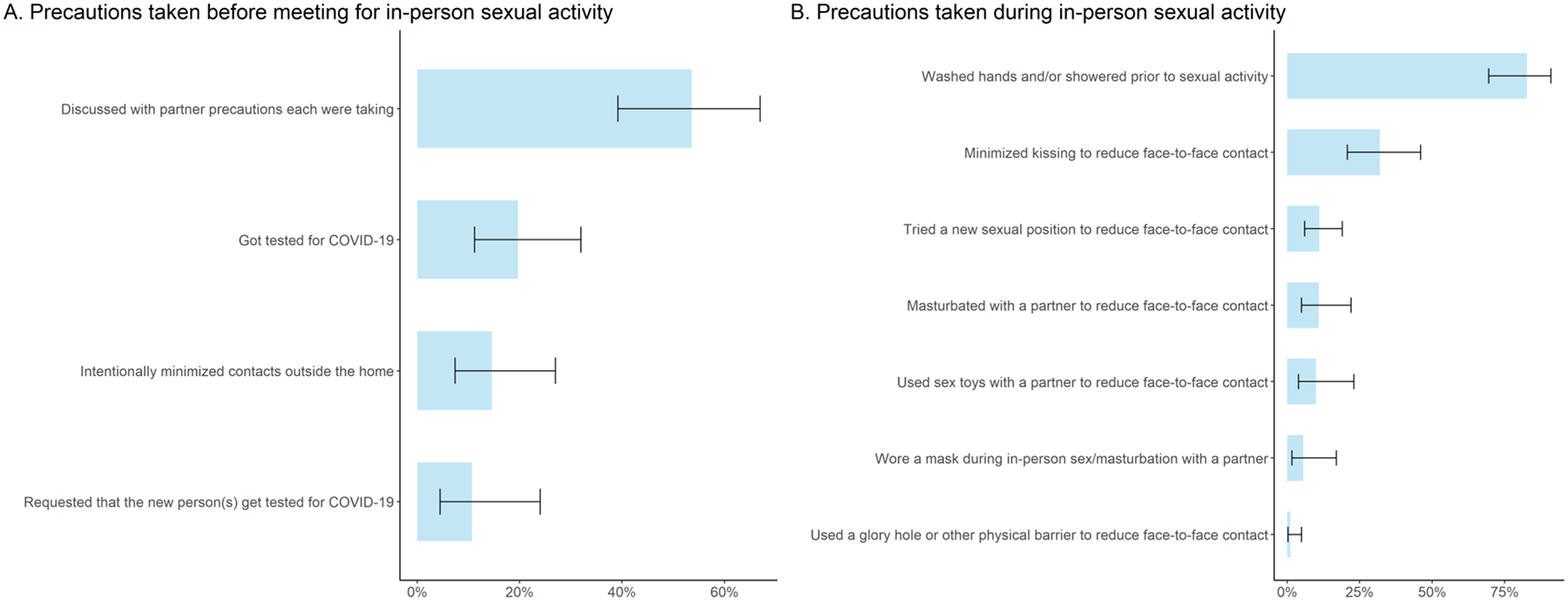

Respondents who had in-person sexual activity with a new partner (N=86) demonstrated considerable variation around precautions taken before an in-person meetup and during sex. Over half of respondents with a valid response (N=55) reported discussing with their partner COVID-19 precautions each person was taking before meeting, whereas 20% or fewer respondents took a COVID-19 test, asked their partner to take a COVID-19 test, or intentionally minimized contacts outside their home (Figure 1A). While these findings highlight challenges around encouraging the public to get tested and reduce contacts before meetups, they also indicate a general openness to discussing COVID-19 precautions with romantic partners. This can be viewed as a partial success, given that convincing the public to discuss HIV/STI risks and precautions with romantic partners remains a challenge (18).

Figure 1. Weighted percentage (%) with 95% confidence intervals of respondents who took precautions before meeting for sexual activity (A) or during in-person sexual activity (B) with a new partner at least once during the pandemic— COVID-19 Sexual Behavior Survey1, United States, March 2020–March 20212.

1Survey questions available in Supplementary Materials

2 Data collection occurred during Feb – Mar 2021. Respondents who participated in Feb 2021 provided data for March 2020-Feb 2021; respondents who participated in March 2021 provided data for March 2020–March 2021.

3 In Figure 1A, percentages are shown for respondents with a valid response (N = 55).

4 Precautions represented in Figure 1B were each presented to respondents as unique survey questions. There were N=86 valid responses to the question regarding “washing” and N=85 valid responses for all remaining precautions shown.

During in-person sexual activity (N=86d), as seen in Figure 1B, most respondents reported washing before/after sex (83%, CI: 70–91%) and 32% (CI: 21–46%) minimized kissing to avoid face-to-face contact. These findings mirror previously documented washing and kissing-avoidance behaviors in Israel during the COVID-19 pandemic (11). Other proposed precautions for preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission during sex (8, Figure 1B) were not commonly practiced in our sample population (<12% of respondents who had in-person sexual activity). Although our sample size was small, our findings indicate that additional research on sexual risk reduction during a respiratory pandemic may be critical.

Since completing data collection in March 2021, COVID-19 vaccines have become widely available for U.S. adults (19). The NYC HD updated their guidance “Safer Sex and COVID-19” in June 2021, which encourages vaccination and proposes vaccine benefits for safer sex practices (20).

Given that younger respondents were more likely to seek a new partner for dating and/or sex during the pandemic, age-specific public health messaging might help reduce risks around dating in the COVID era. Additionally, tailoring public health messaging and establishing support mechanisms may be important for reducing transmission risks for vulnerable populations, such as sexual minority communities, during periods of prolonged social instability. In future pandemics, better understanding of risk avoidance motivators may be important for increasing compliance with public health messaging to prevent transmission of STIs and respiratory pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Poulami Maitra for assistance with analyses.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Defined as a partner that is “most important” but not necessarily exclusive

If a participant rekindled contact with someone who they knew prior to mid-March 2020, they were advised to consider this person to be a “new partner” for the purposes of this survey.

Among people aged 18 −59 who reported ever having sex

For precautions shown in Figure 1B, N=86 for washing; however, N=85 (with one missing response) for the remaining precautions shown

References

- 1.World Health Organization 2020;Pages. Accessed at https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Accessed June 12 2021.

- 2.Moreland A, Herlihy C, Tynan MA, et al. Timing of state and territorial COVID-19 stay-at-home orders and changes in population movement—United States, March 1–May 31, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(35):1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021;Pages. Accessed at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/social-distancing.html. Accessed 2021 June 12.

- 4.Saladino V, Algeri D, Auriemma V. The psychological and social impact of Covid-19: new perspectives of well-being. Front Psychol. 2020;11: 577684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehmiller JJ, Garcia JR, Gesselman AN, Mark KP. Less sex, but more sexual diversity: Changes in sexual behavior during the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Leisure Sciences. 2021;43(1–2):295–304. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez TH, Zlotorzynska M, Rai M, Baral SD. Characterizing the impact of COVID-19 on men who have sex with men across the United States in April, 2020. AIDS and Behav. 2020;24(7):2024–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NYC Health Department. Sex and Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020.

- 8.NYC Health Department. Safer Sex and COVID-19. 2020.

- 9.National Coalition of STD Directors and the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors. Sex and COVID-19: Partners Outside Your Home. 2020.

- 10.Oregon Health Authority. SEX in the time of COVID-19. 2020.

- 11.Shilo G, Mor Z. COVID-19 and the changes in the sexual behavior of men who have sex with men: results of an online survey. J Sex Med. 2020;17(10):1827–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W, Li G, Xin C, Wang Y, Yang S. Challenges in the practice of sexual medicine in the time of COVID-19 in China. J Sex Med. 2020;17(7):1225–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li G, Tang D, Song B, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on partner relationships and sexual and reproductive health: cross-sectional, online survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e20961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dennis J. Technical overview of the AmeriSpeak panel NORC’s probability-based household panel. NORC at the University of Chicago. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heslin KC, Hall JE. Sexual orientation disparities in risk factors for adverse COVID-19–related outcomes, by race/ethnicity—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2017–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(5):149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mestre-Bach G, Blycker GR, Potenza MN. Pornography use in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Behavl Addict. 2020;9(2):181–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Center for Health Statistics 2017;Pages. Accessed at Data file retreived from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/SXQ_I.htm. Accessed Oct 30 2021.

- 18.Bird JD, Eversman M, Voisin DR. “You just can’t trust everybody”: the impact of sexual risk, partner type and perceived partner trustworthiness on HIV-status disclosure decisions among HIV-positive black gay and bisexual men. Cult Health Sex. 2017;19(8):829–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keiser Family Foundation 2021;Pages. Accessed at https://www.kff.org/report-section/state-covid-19-data-and-policy-actions-policy-actions/. Accessed June 12 2021.

- 20.NYC Health Department. Safer Sex and COVID-19. 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.