Abstract

Unlike many reactions of their six-membered-ring counterparts, the reactions of chiral seven-membered-ring enolates are highly diastereoselective. Diastereoselectivity was observed for a range of substrates, including lactam, lactone, and cyclic ketone derivatives. The stereoselectivity arises from torsional and steric interactions that develop when electrophiles approach the diastereotopic π-faces of the enolates, which are distinguished by subtle differences in the orientation of nearby atoms of the ring.

Keywords: enolates, diastereoselectivity, seven-membered-rings, torsional strain, conformational analysis

Graphical Abstract

The diastereoselective reactions of chiral seven-membered-ring enolates have been systematically investigated. Diastereoselectivity was found to be general for ε-lactams, ε-lactones, and cycloheptanones with various substituent patterns. Computational investigations provided insight into the origin of diastereoselectivity. A model for predicting the stereochemistry of seven-membered-ring enolate alkylations is proposed.

The stereoselective synthesis of cyclic carbonyl compounds is often achieved using reactions of enolates to form carbon–carbon and carbon–heteroatom bonds.[1] Reactions of chiral endocyclic enolates can be useful in the cases of four-[2] and five-membered[3]-rings and for macrocyclic systems (eight-membered and larger rings[4]), but predicting the stereochemical outcomes of reactions of six-membered and seven-membered-rings is more challenging. Reactions of six-membered-ring enolates are often unselective,[5] which is believed to be the result of particularly early transition states that do not allow for differentiation of the diastereofaces.[6] The reactions of seven-membered-ring enolates, which are complicated by the many conformations available to seven-membered-rings,[7] have received less attention,[7b] although the few examples reported were diastereoselective.[8] Considering that seven-membered-ring enolates could be useful for the syntheses of biologically active natural products and synthetic drugs,[9] it would be valuable to know whether reactions of seven-membered-ring enolates are generally stereoselective.

In this Communication, we demonstrate that the enolates of many substituted seven-membered-ring compounds undergo reactions with high diastereoselectivity. Experimental results and computational investigations show that stereoselectivity can be explained by considering the different steric and torsional interactions that arise when electrophiles approach the diastereotopic π-faces of these enolates. These data suggest that an early, enolate-like transition state is not responsible for the lack of stereoselectivity in six-membered-ring enolates.

Initial observations focused on the alkylations of seven-membered ε-lactam substrates. These reactions represent model systems for the synthesis of azepane-containing alkaloids.[9e,10] Treatment of C4-substituted lactam 1 with lithium diisopropylamide followed by alkylation with allyl bromide furnished product cis-2a as a 96:4 mixture of diastereomers (eq 1). The use of THF as the solvent proved to be optimal with respect to the yield of the reaction. The use of other solvents (toluene, diethyl ether, n-hexane, and methyl tert-butyl ether) gave similar stereoselectivities but poorer conversion to product. Analysis by X-ray crystallography[11] revealed that the electrophile was installed on the same face as the tert-butyl substituent.[12] This observation indicates that the remote substituent does not interfere directly with the approach of the electrophile to the intermediate. Instead, inherent torsional changes must occur in the transition state to control stereoselectivity. By contrast, alkylation of the enolate of the six-membered-ring lactam 3 was not stereoselective (eq 2), just as these reactions are not generally stereoselective for other types of six-membered-ring enolates.[5] These different outcomes indicate that, in contrast to the accepted explanation for lack of selectivity in six-membered-ring alkylations,[6] it is not likely that the position along the reaction coordinate determines the diastereoselectivity of reactions of cyclic enolates.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

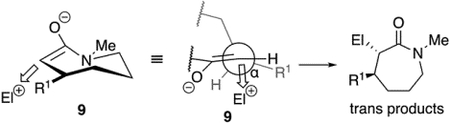

Systematic exploration on the scope of diastereoselectivity in seven-membered-ring alkylations began with exploring the reactions of C3-substituted ε-lactams. Alkylation of C3-substituted lactam 5 with allyl bromide furnished product trans-6 as a single diastereomer (eq 3). Lower diastereoselectivity was observed in the formation of trans-8a (eq 3). The observed preference for anti-alkylation is consistent with what was observed with other endocyclic enolates that bear β-alkyl substituents, regardless of ring size.[2a,3c,3d,8b,13] The favored conformer of the enolate 9 would position the substituent pseudoequatorially, leaving the peripheral face exposed (eq 4). The dependence of stereoselectivity on the size of the substituent suggests that attack from the opposite face is disfavored by a developing steric interaction between the substituent and the incoming electrophile.

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

The importance of the C3 substituent is illustrated by the reactions of seven-membered-ring lactam 10 (eq 5) and lactones 12 and 14 (eq 6). The propensity for alkylation to be controlled by the substituent at C3 appears to supersede any influence on stereoselectivity provided by a remote substituent. This hypothesis is consistent with what has been reported in the alkylations of more highly substituted seven-membered-ring enolates.[8b,13g,13h,14]

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

Alkylations of C4-substituted ε-lactams were generally diastereoselective for various substrates (eq 7). The magnitude of stereoselectivity depended on a number of factors, however. Stereoselectivity decreased as the size of the substituent at C4 decreased across the series t-Bu > Ph > Me (Table 1, cis-2a > cis-17a > cis-19a).[12] The size of the substituent likely determines the magnitude of the conformational preference of the enolate and the first-formed product of alkylation, thus exerting an influence on stereoselectivity. The same trend was observed for the alkylation with MeI, although the diastereoselectivities were generally lower with this electrophile. The decreased selectivities with MeI suggest that steric interactions in the diastereomeric transition states play some role in stereoselectivity, although, unlike for the C3-substituted enolate, these interactions are not likely to be solely responsible for stereoselectivity.[15]

|

(7) |

Table 1.

Alkylations of C4-substituted ε-lactams.

| R1 | Electrophile | Product | dr[a] | Yield[b] (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-Bu | H2C=CHCH2Br | cis- 2a | 96:4 | 77 |

| Ph | H2C=CHCH2Br | cis- 17a | 92:8 | 61 |

| Me | H2C=CHCH2Br | cis- 19a | 83:17 | 68 |

| t-Bu | MeI | cis- 2b | 89:11 | 53 |

| Ph | MeI | cis- 17b | 72:28 | 75 |

| Me | MeI | cis- 19b | 52:48 | 33[c] |

Determined by 13C{1H} analysis of the crude reaction mixture.[16]

Isolated yield of purified product.

Reaction was ceased at 63% conversion to suppress competing di-alkylation.

The diastereoselective alkylations of C4-substituted enolates from the same face as the substituent[12] were general for other electrophiles and substrates (Scheme 1). Benzyl, allyl, and ethyl electrophiles reacted with high stereoselectivity. Addition of the enolate to an aldehyde was also stereoselective for attack from the same face as the substituent, although the facial selectivity on the aldehyde was low, as anticipated for similar endocyclic lithium enolates.[17] Acylation with methyl benzoate[18] afforded cis-2g stereoselectively. The nature of the alkyl substituent on the nitrogen atom did not influence selectivity, as seen with formation of the substituted product cis-21. Even in the case of a substrate with a relatively small alkoxy group at C4, the reaction was diastereoselective (lactam cis-23). Stereoselectivity was not limited to lactam-derived enolates. Similar diastereoselectivity was seen upon alkylation of the enolate of C4-substituted ε-lactone cis-24 (eq 8). The conditions employed in this case were modified to improve the yield of alkylation of this lactone-derived enolate, which was sensitive to decomposition.[19] This example reinforces the distinction between seven-membered-ring enolates and six-membered-ring enolates because alkylations of C4-substituted six-membered-ring lactones proceed with low stereoselectivity.[5a–c]

|

(8) |

Scheme 1.

Scope of stereoselectivity[a] of alkylations of C4-substituted ε-lactam enolates with various electrophiles.

[a] Determined by 13C{1H} analysis of the crude reaction mixture.[16] [b] Isolated yield of purified product. [c] Product of the reaction of 1 with benzaldehyde. The ratio of syn- to anti-aldol adducts was 67:33.

The observed diastereoselectivity of reactions of C4-substituted seven-membered-ring enolates is the result of avoiding both unfavorable steric and torsional interactions upon approach of the electrophile. Calculations[20] using a simplified computational model of the enolate[20] showed that seven-membered-ring enolate 26 adopts a chair conformation[21] in which the tert-butyl substituent occupies a pseudoequatorial position and the nitrogen atom is tetrahedral[22] (Figure 1a). Approach of an electrophile from the peripheral β-face, which would lead to the major product, would be less hindered compared to approach from the non-peripheral α-face (as shown in the Newman projection of 26, Figure 1b, 1c).[4a,23]

Figure 1:

C4-substituted ε-lactam enolates. a) Transition state geometries of TS-26α and TS-26β. b) Enlarged Newman projections of enolate 26, TS-26α and TS-26β, viewing along the C2–C3 bond. c) Schematic depictions of Figure 1b.

Transition-state calculations illustrate more subtle interactions that cause attack from the different faces to have such different energies. Attack from the favored peripheral β-face would enable the transition state to avoid having the vicinal protons at C2 and C3 pass through an eclipsed transition state, as illustrated in the conversion of 26 to TS-26β (Figure 1b, 1c). [24] Conversely, attack from the disfavored α-face through transition state TS-26α would require the H–C2–C3–H torsional angle to pass through an eclipsed conformer on the way to the product (Figure 1b, 1c).[25] This transition state TS-26α also suffers from a developing gauche interaction between the incipient bond to the electrophile and the C3–C4 bond of the seven-membered ring (CMe–C2–C3–C4 dihedral = 50°, Figure 1b, 1c). This interaction, which is accompanied by steric interactions with the C4 and C6 methylene groups (Figure 1a), would become more destabilizing with the larger electrophile.[20] This observation is consistent with calculations using a larger electrophile, allyl chloride, as the electrophile (Figure 1c) and with experimental results (Table 1).

The calculations also provide an explanation for why six-membered-ring lactam enolates do not react stereoselectively (eq 2). In neither transition state TS-27α and TS-27β must the enolate pass through an eclipsed conformer. Both faces of the enolate are also sterically accessible; neither mode of attack develops destabilizing steric interactions. Consequently, the energy difference between the two modes of attack are similar, leading to low stereoselectivity (Figure 2b, 2c).

Figure 2:

C4-substituted δ-lactam enolates. a) Transition state geometries of TS-27α and TS-27β. b) Enlarged Newman projections of enolate 27, TS-27α and TS-27β, viewing along the C2–C3 bond. c) Schematic depictions of Figure 2b.

The reactions of enolates of C5-substituted seven-membered lactams illustrate how small changes in the structure of the ring can exert large influences on stereoselectivity. These enolates did not react diastereoselectively with electrophiles, regardless of the size of the substituent at C5 (eq 9).

|

(9) |

These low diastereoselectivities for the C5-substituted enolate are consistent with the analysis used to explain the high stereoselectivity of the C4-substituted enolates (Figure 1). In contrast to the enolate with a substituent at C4, substitution at the C5 position causes the seven-membered ring to flatten in the vicinity of the enolate to accommodate the large substituent.[20] This flattening of the ring changes the orientation of the carbon–carbon double bond with respect to the ring, as illustrated in the Newman projection of 34 viewing along the C2–C3 bond (Figure 3b, 3c). This change results in the torsional interactions being minimized in one transition state, TS-34α, but steric interactions being minimized in the other (TS-34β, Figure 3b, 3c). As a result, the two modes of attack are more similar in energy, resulting in low diastereoselectivity.[20]

Figure 3:

C5-substituted ε-lactam enolates. a) Transition state geometries of TS-34α and TS-34β. b) Enlarged Newman projections of enolate 34, TS-34α and TS-34β, viewing along the C2–C3 bond. c) Schematic depictions of Figure 3b.

Alkylations of seven-membered-ring lactam enolates with substituents at C6, like the C3-substituted ones, were highly anti-selective (eq 10). The alkylation of C6-substituted lactam 35 with allyl bromide provided product trans-36a as a 97:3 mixture of isomers.[12] This stereoselectivity is consistent with what has been reported for alkylations of similarly substituted six-membered lactam enolates.[26] Just as observed for the C3-substitued lactams, an enolate with a smaller substituent (37) reacted with lower stereoselectivity. Computational analysis revealed that C6-substituted seven-membered lactam enolates prefer geometries with pseudoaxial substituents to minimize allylic strain[27] between the C6 substituent and the alkyl group on the nitrogen atom (39b, Scheme 2). This computational prediction is supported by the fact that a crystal structure of substituted lactam trans-36b (eq 11) shows that the tert-butyl group adopts a pseudoaxial orientation.[12]

|

(10) |

|

(11) |

Scheme 2.

Enolates of C6-substituted seven-membered-rings.

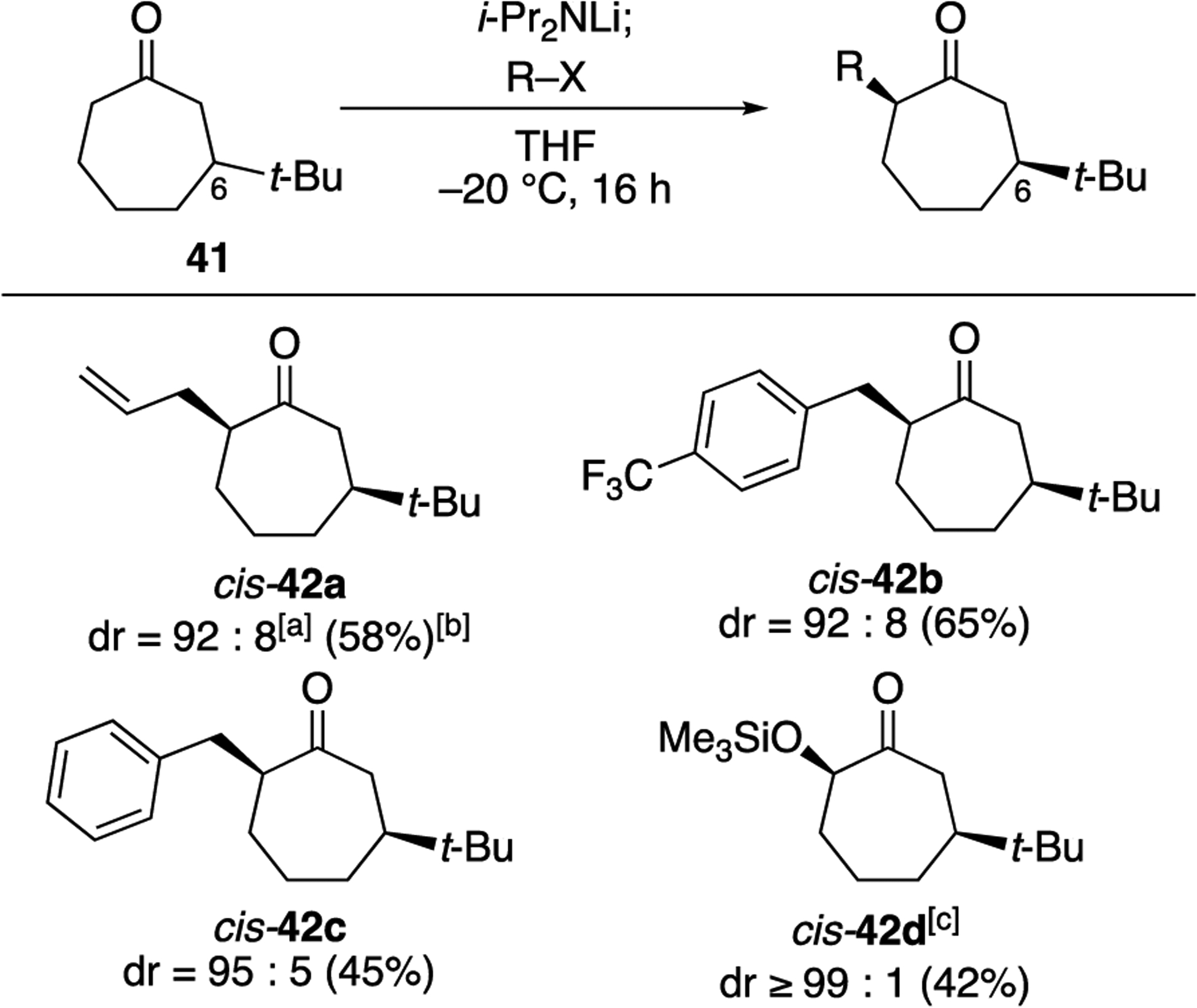

The importance of allylic strain in determining the stereoselectivity shown in Scheme 2 is reinforced by the allylations of a C6-substituted cycloheptanones. Regioselective deprotonation of ketone 41 at the less sterically hindered position followed by alkylation occurred with high syn diastereoselectivity for several electrophiles (Scheme 3). Additionally, trapping of the silicon enolate of 41 with MCPBA[28] occurred with complete facial selectivity, suggesting that the stereochemical outcomes of reactions of seven-membered-ring enolates may also apply more generally to cycloheptenes. The apparent reversal in stereoselectivity compared to the selectivities observed with lactams 35 and 37 can be understood by examining the conformational preferences of the enolate of ketone 35 (Scheme 2). In contrast to the lactam substrates, the lowest energy conformer of the enolate would position the tert-butyl substituent in a pseudoequatorial position (40a, Scheme 2), leading to preferential formation of cis-disubstituted products. Similar to what was observed for the C4-substituted enolate 26 (Figure 1) the C2 carbon atom of the enolate of 35 is slightly twisted in the same direction as the peripheral face of the enolate (H–C–C–H dihedral = +–5°),[20] which likely accounts for the observed high syn diastereoselectivity.

Scheme 3.

Alkylations of C6-substituted cycloheptanones.

[a] Determined by 13C{1H} analysis of the crude reaction mixture.[16] [b] Isolated yield of purified product. [c] Product was synthesized by oxidation of the trimethylsilyl enol ether of 41.

The diastereofacial preference for alkylation of ε-lactam substrates allows for the selective construction of α-carbon quaternary stereocenters (Scheme 4).[10a,29] C3-substituted alkylation product trans-8a was alkylated a second time with benzyl bromide to afford the product trans-8b with high diastereoselectivity at the α-quaternary stereocenter.[30] The alkylation of C4-substituted cis-2a with benzyl bromide afforded product cis-2h as a single diastereomer. The synthesis of other diastereomer, trans-2h, was achieved with high diastereoselectivity by alkylating the α-benzyl compound cis-2c with allyl bromide. The acylation of cis-2a with methyl benzoate occurred with similarly high selectivity to afford cis-2i. The alkylation of C6-substituted product trans-25a was only moderately selective, indicating that diastereoselectivity may be eroded in cases where the α-carbon atom is highly congested. The stereoselective synthesis of the fully substituted products in Scheme 4 provide evidence that the alkylations are under kinetic control because equilibration of these products by deprotonation and reprotonation is not possible.

Scheme 4:

Construction of α-carbon quaternary stereocenters.

[a] The reaction was performed at −20 °C.

In conclusion, reactions of seven-membered-ring enolates with electrophiles generally occur with high diastereoselectivity, in contrast to observations with six-membered-ring enolates. The conformation of a seven-membered-ring enolate, unlike for a six-membered-ring enolate, causes the two diastereotopic faces of the enolate to be differentiated, resulting in diastereoselective reactions. Diastereoselectivity was observed for reactions of seven-membered-ring enolates derived from lactams, lactones, and ketones, and these reactions can be used to control stereoselectivity at quaternary carbon stereocenters. The patterns of selectivity suggest that conformational preferences and torsional effects determine selectivity. The major products of alkylations of endocyclic seven-membered-ring enolates can be readily predicted by establishing the preferred conformation of the enolate and considering torsional and steric interactions that develop upon approach of the electrophile.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1R01GM129286). The authors acknowledge New York University’s Shared Instrumentation Facility and the support provided by National Science Foundation Grant CHE-01162222 and NIH Grant S10-OD016343. The authors thank Dr. Chin Lin (New York University) and Dr. Chunhua (Tony) Hu (New York University) for their help with NMR and X-ray data, respectively.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- [1].Evans DA, in Asymmetric Synthesis, Vol. 3 (Ed.: Morrison JD), Academic Press, New York, 1984, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Mulzer J, Kerkmann T, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1980, 102, 3620–3622; [Google Scholar]; b) Lee SH, Bull. Korean Chem. Soc 2013, 34, 121–127; [Google Scholar]; c) Baldwin JE, Adlington RM, Gollins DW, Schofield CJ, Tetrahedron Lett 1990, 46, 4733–4748; [Google Scholar]; d) Meiries S, Marquez R, J. Org. Chem 2008, 73, 5015–5021; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Lin YC, Ribaucourt A, Moazami Y, Pierce JG, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 9850–9857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Dostie S, Prévost M, Mochirian P, Tanveer K, Andrella N, Rostami A, Tambutet G, Guindon Y, J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 10769–10790; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Miyaoka H, Hara Y, Shinohara I, Kurokawa T, Yamada Y, Tetrahedron Lett 2005, 46, 7945–7949; [Google Scholar]; c) Soulieman A, Gouault N, Roisnel T, Justaud F, Boustie J, Grée R, Hachem A, Synlett 2019, 30, 2258–2262; [Google Scholar]; d) Johnson TA, Jang DO, Slafer BW, Curtis MD, Beak P, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 11689–11698; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) McAtee JJ, Schinazi RF, Liotta DC, J. Org. Chem 1998, 63, 2161–2167; [Google Scholar]; f) Wångsell F, Gustafsson K, Kvarnström I, Borkakoti N, Edlund M, Jansson K, Lindberg J, Hallberg A, Rosenquist Å, Samuelsson B, Eur. J. Med. Chem 2010, 45, 870–882; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Reddy CR, Dharmapuri G, Rao NN, Org. Lett 2009, 11, 5730–5733; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Konas DW, Coward JK, J. Org. Chem 2001, 66, 8831–8842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Still WC, Galynker I, Tetrahedron 1981, 37, 3981–3996; [Google Scholar]; b) Larsen EM, Chang CF, Sakata-Kato T, Arico JW, Lombardo VM, Wirth DF, Taylor RE, Org. Biomol. Chem 2018, 16, 5403–5406; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Paquette LA, Efremov I, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 4492–4501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Morgans DJ, Tetrahedron Lett 1981, 22, 3721–3724; [Google Scholar]; b) White JD, Somers TC, Reddy GN, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1986, 108, 5353–5354; [Google Scholar]; c) Pinyarat W, Mori K, Biosci. Biotech. Biochem 2014, 57, 419–421; [Google Scholar]; d) Abels F, Lindemann C, Schneider C, Chem. Eur. J 2014, 20, 1964–1979; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Coe D, Drysdale M, Philps O, West R, Young DW, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1 2002, 2459–2472. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bare TM, Hershey ND, House HO, Swain CG, J. Org. Chem 1972, 37, 997–1002. [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Groenewald F, Dillen J, Struct. Chem 2011, 23, 723–732; [Google Scholar]; b) de Oliveira KT, Servilha BM, de CL. Alves A. L. Desiderá, Brocksom TJ, in Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, Vol. 42 (Ed.: Atta-ur-Rahman), Elsevier, 2014, pp. 421–463; [Google Scholar]; c) Entrena A, Campos JM, Gallo MA, Espinosa A, ARKIVOC 2005, vi, 88–108; [Google Scholar]; d) Entrena A, Campos JM, Gómez JA, Gallo MA, Espinosa A, J. Org. Chem 1997, 62, 337–349; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Espinosa A, Gallo MA, Entrena A, Gómez JA, J. Mol. Struct 1994, 323, 247–256. [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Posner GH, Babiak KA, Loomis GL, Frazee WJ, Mittal RD, K. IL, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1980, 102, 7498–7505; [Google Scholar]; b) Lee SJ, Beak P, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 2178–2179; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Nakamura T, Hirota H, Takahashi T, Chem. Pharm. Bull 1986, 34, 3518–3521; [Google Scholar]; d) Mehta G, Krishnamurthy N, Rao Karra S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1991, 113, 5765–5775. [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Burgey CS, Paone DV, Shaw AW, Deng JZ, Nguyen DN, Potteiger CM, Graham SL, Vacca JP, Williams TM, Org. Lett 2008, 10, 3235–3238; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Crimmins MT, Mans MC, Rodríguez AD, Org. Lett 2010, 12, 5028–5031; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Sizun G, Dukhan D, Griffon JF, Griffe L, Meillon JC, Leroy F, Storer R, Sommadossi JP, Gosselin G, Carbohydr. Res 2009, 344, 448–453; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Torssell S, Wanngren E, Somfai P, J. Org. Chem 2007, 72, 4246–4249; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) White KN, Tenney K, Crews P, J. Nat. Prod 2017, 80, 740–755; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Xu DD, Waykole L, Calienni JV, Ciszewski L, Lee GT, Liu W, Szewczyk J, Vargas K, Prasad K, Repič O, Blacklock TJ, Org. Process Res. Dev 2003, 7, 856–865. [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Ramli RA, Lie W, Pyne SG, J. Nat. Prod 2014, 77, 894–901; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Huang S-Z, Kong F-D, Ma Q-Y, Guo Z-K, Zhou L-M, Wang Q, Dai H-F, Zhao Y-X, J. Nat. Prod 2016, 79, 2599–2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].The CCDC Deposition Numbers 2116556, 2116557, 2116558, 2116559, and 2116560 contain crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

- [12]. Details of stereochemical proofs are provided as Supporting Information.

- [13].a) Soorukram D, Panmuang J, Tuchinda P, Kuhakarn C, Reutrakul V, Pohmakotr M, Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 7577–7583; [Google Scholar]; b) Bartrum HE, Jackson RFW, Synlett 2009, 14, 2257–2260; [Google Scholar]; c) Galeazzi R, Martelli G, Mobbili G, Orena M, Rinaldi S, Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2003, 14, 3353–3358; [Google Scholar]; d) Patterson JW, Fried JH, J. Org. Chem 1974, 39, 2506–2509; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Tomioka K, Kawasaki H, Yasuda K, Koga K, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1988, 110, 3597–3601; [Google Scholar]; f) Weber K, Gmeiner P, Synlett 1998, 8, 885–887; [Google Scholar]; g) Hennig R, Metz P, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 1157–1159; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Zhao N, Yin S, Xie S, Yan H, Ren P, Chen G, Chen F, Xu J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 3386–3390; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Daniewski AR, Warchol T, Liebigs Ann. Chem 1992, 965–973; [Google Scholar]; j) Grayson DH, Wilson JRH, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1984, 1695–1696. [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Funk RL, Olmstead TA, Parvez M, Stallman JB, J. Org. Chem 1993, 58, 5873–5875; [Google Scholar]; b) Lansbury PT, Galbo JP, Springer JP, Tetrahedron Lett 1988, 29, 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Volp KA, Harned AM, J. Org. Chem 2013, 78, 7554–7564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Otte DA, Borchmann DE, Lin C, Weck M, Woerpel KA, Org. Lett 2014, 16, 1566–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Majewski M, Gleave DM, Tetrahedron Lett 1989, 30, 5681–5684. [Google Scholar]

- [18].The use of benzoyl chloride as an electrophile provided a complex mixture of products, presumably the result of this harder electrophile reacting through non-productive O-alkylation pathways.

- [19].a) Sullivan DF, Woodbury RP, Rathke MW, J. Org. Chem 1977, 42, 2038–2039; [Google Scholar]; b) Seebach D, Amstutz R, Laube T, Schweizer WB, Dunitz JD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1985, 107, 5403–5409. [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Density function theory calculations (B3LYP) were performed using Gaussian 16 with the 6–31+G(d) basis set using the CPCM model for THF. Details are in the Supporting Information.

- [21].a) Jiang W, Lantrip DA, Fuchs PL, Org. Lett 2000, 2, 2181–2184; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Allen FH, Trotter J, J. Chem. Soc. B 1970, 721–727; [Google Scholar]; c) Ogura K, Ishida M, Fujita M, Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 1989, 62, 3987–3993; [Google Scholar]; d) Pattabhi V, Pramana 1978, 11, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Meyers AI, Seefeld MA, Lefker BA, Blake JF, Willard PG, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 120, 7429–7438; [Google Scholar]; b) Laube T, Dunitz JD, Seebach D, Helv. Chim. Acta 1985, 68, 1373–1393. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Vedejs E, Gapinski DM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1983, 105, 5058–5061. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Csókás D, Siitonen JH, Pihko PM, Pápai I, Org. Lett 2020, 22, 4597–4601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ashby EC, Laemmle JT, Chem. Rev 1975, 75, 521–546. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Maldaner AO, Pilli RA, Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 13321–13332. [Google Scholar]

- [27].a) Seebach D, Lamatsch B, Amstutz R, Beck AK, Dobler M, Egil M, Fitzi R, Gautschi M, Herradón B, Hidber PC, Irwin JJ, Locher R, Maestro M, Maetzke T, Mouriño A, Pfammatter E, Plattner DA, Schickli C, Schweizer WB, Seiler P, Stucky G, Helv. Chim. Acta 1992, 75, 913–934; [Google Scholar]; b) Hoffmann RW, Chem. Rev 1989, 89, 1841–1860. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Rubottom GM, Vazquez MA, Pelegrina DR, Tetrahedron Lett 1974, 15, 4319–4322. [Google Scholar]

- [29].a) Cheng GG, Li D, Hou B, Li XN, Liu L, Chen YY, Lunga PK, Khan A, Liu YP, Zuo ZL, Luo XD, J. Nat. Prod 2016, 79, 2158–2166; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Xu R-S, Lu Y-J, Chu J-H, Iwashita T, Naoki H, Naya Y, Nakanishi K, Tetrahedron 1982, 38, 2667–2670; [Google Scholar]; c) Hirasawa Y, Morita H, Kobayashi J, 2002, 58, 5483–5488; [Google Scholar]; d) Ishiuchi K, Kubota T, Hoshino T, Obara Y, Nakahata N, Kobayashi J, Bioorg. Med. Chem 2006, 14, 5995–6000; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Behenna DC, Liu Y, Yurino T, Kim J, White DE, Virgil SC, Stoltz BM, Nat. Chem 2011, 4, 130–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Attempts to form quaternary centers on compounds with C3 tert-butyl substituents were complicated by the formation of undesired side products and starting material decomposition.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.