Epidemiological studies over three decades have identified associations between the dementia-Alzheimer syndrome and an array of putative risk factors. Numerous randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have tested the efficacy of interventions suggested by these associations. The uniformly disappointing results of those efforts were reviewed in a recent large article.1 For convenience, a Perspectives article in this journal summarized these findings and suggested methodological pitfalls, gaps in current knowledge, and other ways to improve future trial designs.2 Three familiar explanations for the trials’ disappointing results are: 1. Trials are necessarily of short duration; they cannot test interventions on associations that evolve over decades, typically beginning in middle life. 2. Trial populations are often enriched for the probability of their specified outcome; consequently results may not generalize broadly. 3. Risk factor intervention trials generally use outcomes (e.g., cognitive decline) that differ from the categorical outcomes typical in observational studies (e.g., dementia incidence, “conversion” from MCI to dementia.) We also suggest a fourth issue that may be less widely appreciated: These trials typically rely on randomization to control for lifestyle and psycho-social variables (true for all seven of intervention efforts discussed in reference1). But such randomization prevents consideration of the one risk factor intervention strategy – modification of lifestyle factors – that has had some success in modifying cognitive outcomes (viz. FINGER studies).

We suggest that these methodological concerns cannot address the most important aspect of the dementia-Alzheimer syndrome, the variability of its symptoms, cognitive and behavioral, that produce its disabilities and burden of care. Surely, the most important “target” for any therapeutic or preventive intervention is mitigation of such symptoms. But here we must confront our ignorance about their genesis in the clinico-pathological entity known variously as Senile Dementia of the Alzheimer Type (SDAT), Dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease (DAD), Alzheimer’s dementia (AD), etc. We therefore offer several suggestions that reflect our view that several common assumptions about the dementia-Alzheimer syndrome may be misguided and, in some instances, represent descriptions masquerading as explanations.

1. “Exceptions that prove the rule?” Should not the disparity in observational study vs. trial results challenge prevailing notions about AD pathobiology and symptoms?

The phrase “exceptions that prove the rule” traces to Cicero’s exceptio probat regulam in casibus non exceptis. The Latin verb probare (from which “prove” and “proof” are derived) means to test, verify, or validate. Consider the derived English words probe (inquire deeply, explore, test), probate (court verification of prescribed disposition of estate), probative (investigating or demonstrating verifiability), probity (trustworthiness, truthfulness, usually of an individual).

The recurrent mismatch of trial and observational studies brings to mind W. Bateson’s admonition that we should “treasure (these) exceptions,”3 that can challenge prevailing hypotheses or reinforce them. Consider, for example, the puzzling “exceptions” to John Snow’s hypothesis that the infamous Broad Street pump was the source of London’s 1854 cholera epidemic. Several stricken households in districts not served by the pump appeared initially to impeach Snow’s hypothesis; but in the end Snow discovered that they too drew their water from the (distant) pump because they preferred its taste (25). In like manner, should we not be vigilant for lessons hidden in the repeated “exceptions” to hypothesized results of risk factor intervention trials?

2. The dementia-Alzheimer syndrome as a conceptual model of the ‘disease’.

Here as elsewhere, the term syndrome refers to a familiar combination of symptoms (here, cognitive and behavioral abnormalities) with or without an associated neuropathology. But anomalies specific to the dementia-Alzheimer syndrome include, first, a neuropathology that is far from homogeneous, and second (and perhaps more perplexing), an association of such pathology with symptoms that is far from uniform.

Neuropathologic studies, for example, have shown that only a small proportion of brains from persons with dementia show “pure” AD pathology (viz., amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles).4 Usually, there is also large vessel or microvascular pathology, or presence of Lewy bodies or synuclein strands, or hippocampal sclerosis, or TDP-43 accumulation, or suggestion of white matter disruption, and so on. For this reason, it is difficult to grade the extent of “AD pathology”, because the available grading systems generally overlook these “co-morbidities”. But we know in fact that several of them can have substantial effects on symptom expression. Strokes and microvascular lesions, when present, tend to exaggerate cognitive symptoms.5–7 Other data suggest that various forms of innate immune activity can modify both the biological pathogenesis of the disease 8,9 and its tendency to provoke symptoms.10 We wonder, in fact, whether the relative paucity of “pure” AD pathology in brains of persons with dementia reflects a reality that such pathology may in itself have a limited capacity to provoke cognitive symptoms and dementia. But our understanding of the association of AD pathology and its co-morbid features with the important cognitive outcomes is meager at best. Small wonder, then, that the characteristic cognitive decline of “Alzheimer’s disease” has long been observed to correlate weakly with amyloid pathology, and only moderately with tau burden.11

Here may lie the greatest shortcomings of current efforts to reduce the morbidity of the syndrome. Our field has, over the past decade or so, shown a distinct change in emphasis away from cognitive symptoms and toward the more basic biology of the “disease.” Thus, while the widely used A/T/N classification of Alzheimer’s disease holds considerable value in clarifying the degree of “classic” AD pathology, it does not (by its nature) consider the aforementioned pathological “co-morbidities” or their potential effect on symptom expression. Nor does it consider an array of data suggesting that symptoms may be modulated by other features. Even psycho-social factors such as anxiety, stress, depression, loneliness or trait “neuroticism” can be associated with exaggeration of symptoms for a given level of “AD pathology”.12,13 At present, our field has only a rudimentary understanding of the mechanisms by which these non-biological features influence symptom expression, but, we suggest, we ignore them at our peril.

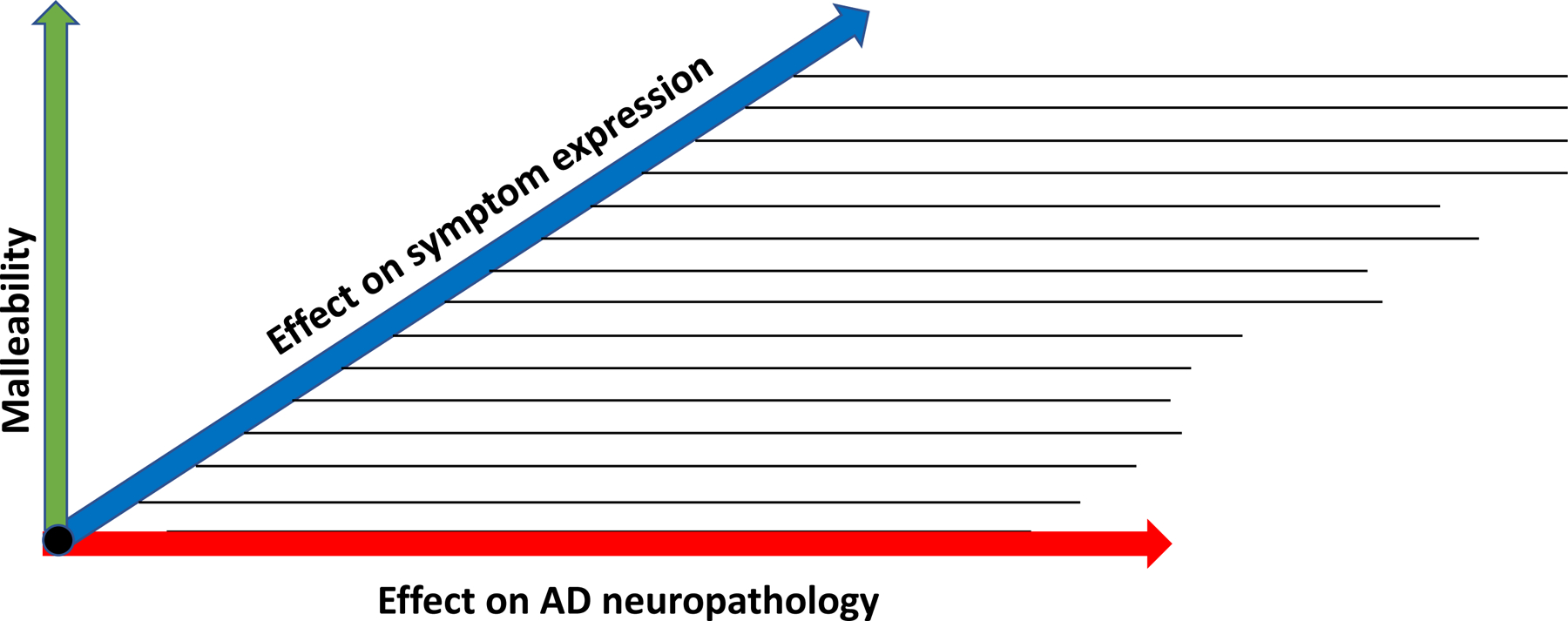

3. A proposed triaxial structure for classification of factors that may modify outcomes in the dementia – Alzheimer Syndrome.

We suggest that the figure below may be useful when thinking about these topics.

On the horizontal axis is a given risk factor’s influence on characteristic Alzheimer neuropathology itself. This neuropathology is (by definition) a requirement of the dementia-Alzheimer syndrome. As noted, it is not homogeneous, and numerous co-morbid pathologic features can modify its likely association with concurrent cognitive or behavioral symptoms. But we also know that (in pure form at least) AD neuropathology often does not provoke symptoms. It has long been evident that some 25% of elderly persons whose autopsied brains meet customary criteria for (diagnosable) “AD” were not known to have had cognitive symptoms (or at least dementia symptoms) ante mortem.14–17 It follows that at least some “risk” factors that accelerate or retard expression of the disease biology would have little or no cognitive effect in these persons.

On the receding axis of Figure 1 we suggest that some environmental (or at least non-intrinsic or biologic) risk factors can influence symptom formation, conditioned on the presence of the pathology. Here we might think of risk modifiers such as exercise, diet, cardiopulmonary conditioning, or stress reduction, but we could also include notions such as “cognitive reserve”, indicating the brain’s ability to withstand greater or lesser amounts of neurodegenerative change before functional loss becomes apparent. In general, as we learn more about which risk factors exert the greatest influence on symptom formation (related to pathological severity), we should be positioned to choose more carefully among various candidate interventions.

Figure 1.

Proposed triaxial classification of factors that may modify outcomes in the dementia–AD syndrome

To some extent, the choice of such strategies may also be driven by the degree to which interventions can affect the specific factor one is trying to modify. We call this attribute “malleability” and show it on a third, vertical axis in Figure 1. But, at risk of repetition, we again emphasize that a given risk factor may be malleable and have strong effects on symptom expression relative to a given degree of “AD pathology” but have no effect on the progression of the “disease biology” (read A/T/N).

Unfortunately, even more perplexing challenges may lie before us. Consider again, that the estimated cumulative incidence of dementia-Alzheimer symptoms reaches something like 70% by age 100. This number that can be estimated using survival analytic techniques from individual studies,18 or by integration of the well-known “Brookmeyer equation” through age 100 years.19 We observe, further, that this proportion is likely an underestimate, because population surveys almost always suffer from ascertainment bias in which persons with disability are less likely to be discovered. But ignoring this last point, if 70% of people will develop dementia-AD symptoms if they live long enough, and another 25% will have typical “AD neuropathology” without dementia, then where does that leave us? Are we dealing with a universal human characteristic that is (inexplicably, for now) symptomatically silent in a minority of persons? We don’t mean to be nihilistic; rather we raise this point in keeping with the old adage that it is better to “know your enemy.” We don’t know (but would surely like to know) what accounts for the good fortune of the ~25% who can withstand “AD pathology” without showing symptoms. The factors that seem to protect these favored persons should, it seems to us, be given the highest priority as we investigate this syndrome in hopes of its (symptomatic) prevention. And, conversely, we suggest that study of disease pathobiology and its determinants, without consideration to symptomatic effects, is less important than seems to be widely assumed.

4. Descriptions masquerading as explanations: potential for a “new epidemiology” built around observations in humans.

The past two decades have witnessed astonishing laboratory and technological advances in research on the dementia-Alzheimer syndrome. And yet, we suggest, our field remains fundamentally ignorant about the root causes of this extremely common human frailty. Our intuitive assumption is that the cognitive failure of the dementia-Alzheimer syndrome will prove in some way to arise from the loss of synaptic connectivity that has long been observed in the brain’s regions that support cognition. Such failure might result from loss of neurons, or (as the late Robert Terry would remind us) from reduction in a typical neuron’s loss of synaptic connections, or perhaps no reduction in synaptic number but a decrease in the efficiency of synaptic connections.20 If our assumption is correct, then the fundamental challenge for any theory of AD pathogenesis will be its ability to explain this ultimate loss of synaptic connectivity.21

As to specific mechanisms: notwithstanding huge efforts to understand the pathophysiology of alterations in the Aβ peptide and its metabolism, we are impressed that tau pathology is more strongly associated with cognitive deficit.11 This suggests that derangements in tau structure and function may have a more proximate connection with cognitive failure. But, outside of in vitro or in vivo animal models (and their associated limitations), we understand little about the causes or even the consequences of AD tauopathy. We also wonder why vascular insufficiency in its several forms seems strongly to potentiate the appearance of cognitive symptoms. Even more mysteriously, how can neuroticism, emotional distress or depression reduce numbers of synapses or, instead, reduce the frequency or efficiency of synaptic transmission? An important role for inflammatory or immune processes in AD pathogenesis now seems beyond doubt;8 but it remains unclear whether such processes initiate pathological changes, exacerbate them, or perhaps mitigate them or modify their symptomatic expression.22

The above are all “how” or “what” questions, rather than “why” questions. Given the complex maze of such potential mechanistic pathways, there remains a grand challenge to map the interactions that may result in a “final common pathway” of synaptic failure (if that is indeed the cause of the symptoms) or (if not) the real reasons for symptom severity. We have noted previously that this sort of complexity likely will require higher-order analytic techniques of systems biology for explanation.23,24 If these are not successful, then at the least research into causal mechanism should rely on longitudinal observations (with or without interventions) in humans. The siren call of enhanced laboratory technology is hard to resist (!) but cross-sectional observations, especially those that rely on non-human models, are ill-suited to causal inference. We suggest that such cross-sectional or even longitudinal observations in non-human research regularly bring a sense of satisfaction in the generation of descriptive knowledge of disease phenomena. But mechanistic and dynamic explanation (not description) of symptom-generating mechanisms is what one needs to provide crucial clues to achieve prevention or mitigation of clinical burden. We urge especially that our field resist the temptation to regard ever-finer pathological description of the dementia-Alzheimer syndrome as an explanation for its morbid effects.

Acknowledgement

This work is partly supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P30AG066518 (in support of HHD’s work) and by Pfizer Canada, the Government of Canada, and McGill University (support for JCSB).

Disclosure

Hiroko H. Dodge is supported by NIH funding and serves as a consultant for Biogen, Inc.

ZSK is Editor-in-Chief of Alzheimer’s & Dementia, he has grants, contracts, or subawards from the Alzheimer’s Association, Berkman Charitable Trust, Arizona State University, consulting fees from Renew Research, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Biogen, and has leadership/fiduciary roles for Prevent Alzheimer’s Disease 2020 and is an employee of KAI.

ASK is Executive Editor of Alzheimer’s & Dementia, Alzheimer’s & Dementia Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, Alzheimer’s & Dementia Diagnosis, Assessment and Disease Monitoring, he has grants, contracts, or subawards from the Alzheimer’s Association, Berkman Charitable Trust, Arizona State University, consulting fees from Renew Research, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Biogen, and has leadership/fiduciary roles for Prevent Alzheimer’s Disease 2020, Care Weekly and is an employee of KAI.

References

- 1.Peters R, Breitner J, James S, et al. Dementia risk reduction: why haven’t the pharmacological risk reduction trials worked? An in-depth exploration of seven established risk factors. Alzheimer’s & dementia : translational research & clinical interventions. 2021;7(1):e12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peters R, Dodge HH, James S, et al. The epidemiology is promising, but the trial evidence is weak. Why pharmacological dementia risk reduction trials haven’t lived up to expectations, and where do we go from here? Alzheimers Dement. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cock A, Forsdyke DR. Treasure Your Exceptions: The Science and Life of William Bateson. New Yrok: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69(24):2197–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabinovici GD, Carrillo MC, Forman M, et al. Multiple comorbid neuropathologies in the setting of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology and implications for drug development. Alzheimer’s & dementia : translational research & clinical interventions. 2017;3(1):83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toledo JB, Arnold SE, Raible K, et al. Contribution of cerebrovascular disease in autopsy confirmed neurodegenerative disease cases in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centre. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2013;136(Pt 9):2697–2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodge HH, Zhu J, Woltjer R, et al. Risk of incident clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease-type dementia attributable to pathology-confirmed vascular disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(6):613–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heneka MT, Carson MJ, El Khoury J, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(4):388–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suarez-Calvet M, Araque Caballero MA, Kleinberger G, et al. Early changes in CSF sTREM2 in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease occur after amyloid deposition and neuronal injury. Science translational medicine. 2016;8(369):369ra178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer P, Savard M, Poirier J, Breitner J. Submitted.

- 11.Arriagada PV, Marzloff K, Hyman BT. Distribution of Alzheimer-type pathologic changes in nondemented elderly individuals matches the pattern in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1992;42(9):1681–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson RS, Arnold SE, Schneider JA, Li Y, Bennett DA. Chronic distress, age-related neuropathology, and late-life dementia. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(1):47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Mendes de Leon CF, Bienias JL, Morris MC, Evans DA. Distress proneness and cognitive decline in a population of older persons. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(1):11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crystal H, Dickson D, Fuld P, et al. Clinico-pathologic studies in dementia: nondemented subjects with pathologically confirmed Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1988;38(11):1682–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katzman R, Terry R, DeTeresa R, et al. Clinical, pathological, and neurochemical changes in dementia: a subgroup with preserved mental status and numerous neocortical plaques. Ann Neurol. 1988;23(2):138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aizenstein HJ, Nebes RD, Saxton JA, et al. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Archives of neurology. 2008;65(11):1509–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sonnen JA, Santa Cruz K, Hemmy LS, et al. Ecology of the aging human brain. Archives of neurology. 2011;68(8):1049–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breitner JC. What should we do if we were wrong and Alzheimer was right? Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(1):3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brookmeyer R, Evans DA, Hebert L, et al. National estimates of the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(1):61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alzheimer’s Association Calcium Hypothesis W. Calcium Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease and brain aging: A framework for integrating new evidence into a comprehensive theory of pathogenesis. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(2):178–182 e117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khachaturian ZS, Mesulam MM, Khachaturian AS, Mohs RC. The Special Topics Section of Alzheimer’s & Dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(11):1261–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer PF, Savard M, Poirier J, Morgan D, Breitner J, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Hypothesis: cerebrospinal fluid protein markers suggest a pathway toward symptomatic resilience to AD pathology. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(9):1160–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geerts H, Dacks PA, Devanarayan V, et al. Big data to smart data in Alzheimer’s disease: The brain health modeling initiative to foster actionable knowledge. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(9):1014–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haas M, Stephenson D, Romero K, et al. Big data to smart data in Alzheimer’s disease: Real-world examples of advanced modeling and simulation. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(9):1022–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Principles of Epidemiology in Public Health Practice. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated May 18, 2021. Accessed February 1, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson1/section2.html