Abstract

Background and Aims:

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease Type 1A (CMT1A) is caused by duplication of the PMP22 gene and is the most common inherited peripheral neuropathy. Although CMT1A is a dysmyelinating peripheral neuropathy, secondary axon degeneration has been suggested to drive functional deficits in patients. Given that SARM1 knockout is a potent inhibitor of the programmed axon degeneration pathway, we asked whether SARM1 knockout rescues neuromuscular phenotypes in CMT1A model (C3-PMP) mice.

Methods:

CMT1A mice were bred with SARM1 knockout mice to generate CMT1A/SARM1 −/− mice. A series of behavioral assays were employed to evaluate motor and sensorimotor function. Electrophysiological and histological studies of the tibial branch of the sciatic nerve were performed. Additionally, gastrocnemius and soleus muscle morphology were also evaluated histologically.

Results:

Although clear behavioral and electrophysiological deficits were observed in CMT1A model mice, SARM1 knockout conferred no significant improvement. Nerve morphometry revealed predominantly myelin deficits in CMT1A model mice and SARM1 knockout yielded no improvement in all nerve morphometry measures. Similarly, muscle morphometry deficits in CMT1A model mice were not improved by SARM1 knockout.

Interpretation:

Our findings demonstrate that programmed axon degeneration pathway inhibition does not provide therapeutic benefit in CMT1A model mice. Our results indicate that the clinical phenotypes observed in CMT1A mice are likely caused primarily by prolonged dysmyelination, motivate further investigation into mechanisms of dysmyelination in these mice and necessitate the development of improved CMT1A rodent models that recapitulate the secondary axon degeneration observed in patients.

Keywords: CMT1A, SARM1, Behavior, Electrophysiology, Histology

Introduction

Peripheral neuropathies (PN) are debilitating disorders caused by damage to the peripheral nervous system that affect 2.4% of the total population and 8.0% of the advanced age population1. Several types of PN have been identified and are classified based on the mode of acquisition (inherited or acquired), the type of nerves affected (sensory, motor and/or autonomic) and the type of cell affected (neuron or Schwann cell). Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 1A (CMT1A), most common inherited PN, is a progressive dysmyelinating polyneuropathy that is caused by duplication of a 1.5 Mb region (17p11.2-p12) containing the Peripheral Myelin Protein 22 (PMP22) gene2. CMT1A patients experience sensory and motor deficits that dramatically affect their quality of life and burden the healthcare system2. However, only palliative treatments are currently available to help patients cope with their symptoms.

Although CMT1A is a dysmyelinating disease, secondary axon degeneration has been suggested to be the leading cause of functional deficit in these patients3. Therefore, inhibiting axon degeneration may be a beneficial strategy for treating CMT1A patients. We have recently gained a greater appreciation for a pathway that is required to execute an autonomous axon degeneration program, sometimes referred to as Wallerian-like degeneration but here termed the programmed axon degeneration pathway, which makes this approach feasible. Briefly, reduction of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Adenylyl Transferase 2 (NMNAT2) and the consequent reduction of Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD+) activates Sterile Alpha and TIR Motif Containing 1(SARM1) leading to a further depletion of NAD+ levels due to SARM1 NADase activity and eventually triggers ATP loss, energetic failure and Calpain-mediated proteolysis of axon structural proteins4. The programmed axon degeneration pathway has been interrogated for its involvement in the pathogenesis of several neurological diseases most often by introducing the Wallerian degeneration slow (WldS) transgene, which encodes a fusion protein containing an NMNAT2 ortholog4, or knocking out SARM1. WldS expression is neuroprotective in several disease models including Chemotherapy Induced Peripheral Neuropathy5, 6, Glaucoma7–9, Multiple Sclerosis10, Parkinson’s disease11–13, Progressive Motor Neuronopathy14 and Traumatic Brain Injury15, 16. Additionally, SARM1 knockout is neuroprotective in several disease models including 5Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis17, Chemotherapy Induced Peripheral Neuropathy18–20, Traumatic Brain Injury21, 22 and Retinal Degeneration23, 24. Interestingly, SARM1 knockout was able to prevent axon degeneration in NMNAT2 deficient mice whereas WldS merely delayed it suggesting that SARM1 is the optimal target for inhibiting this pathway25.

The contribution of the programmed axon degeneration pathway to CMT1A pathogenesis has previously been evaluated by expressing the WldS transgene in CMT1A model rats (CMT1A/WldS +/− rats). Introducing WldS rescued the modest reduction in the number of tibial nerve axons observed in 13-week-old CMT1A rats and partially rescued tail compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitudes and nerve conduction velocities (NCV) of 10-week-old CMT1A rats26. Additionally, muscle function was evaluated by forelimb grip strength, but the results were less clear. The change in grip strength from 5 to 13 weeks was reported to account for the reduced body weight observed in WldS +/− control rats. Results revealed that grip strength increased in CMT1A/WldS +/− rats as compared to wildtype rats but CMT1A rats did not exhibit reduced grip strength as compared to wildtype26. These findings suggest that WldS expression delays the modest axon degeneration observed in young CMT1A model rats, which results in moderate increases in nerve and potentially muscle function. However, questions remained about the ability of programmed axon degeneration inhibition to rescue CMT1A pathogenesis in mature animals where axon degeneration is likely more prominent and whether knocking out SARM1 would provide enhanced neuroprotection.

To answer these questions, we bred CMT1A model mice (C3-PMP, which contains three copies of the human proximal CMT1A duplication region including the complete PMP22 gene in addition to the endogenous mouse PMP22 genes)27 with SARM1 knockout mice28 and evaluated rescue of behavioral, electrophysiological and histological phenotypes in three- and six-month-old mice to determine if SARM1 knockout improves CMT1A deficits. Although CMT1A mice exhibited clear deficits in motor and sensorimotor behavioral assays and by electrophysiological assessment, there was no rescue at either three or six months with SARM1 knockout. Furthermore, there was not a significant reduction in the number of axons in the sciatic nerve and significant denervation was not observed in the soleus muscle indicating that the behavioral and electrophysiological deficits in CMT1A mice are largely driven by prolonged dysmyelination rather than axonal degeneration. The poor recapitulation of secondary axon degeneration in CMT1A mice motivates further investigation into mechanisms of dysmyelination in these mice and suggests that improved CMT1A rodent models need to be developed.

Materials and Methods

Animal husbandry and testing scheme

All experiments were conducted with the approval of the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee. C3-PMP mice (B6.Cg-Tg(PMP22)C3Fbas/J, referred to as CMT1A mice) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory, expanded by mating CMT1A females with wildtype males (C57BL/6J) and genotyped according to the suggested protocol. SARM1 knockout mice (B6.129X1-Sarm1tm1Aidi/J) were also obtained from the Jackson Laboratory and genotyped according to the suggested protocol. CMT1A/SARM1+/− mice were generated by first mating CMT1A mice with SARM1 knockout mice and then mating CMT1A/SARM1+/− mice with wildtype/SARM1 +/− mice. A balanced representation of male and female mice aged approximately three and six months were assessed by SHIRPA and inverted holding test three times per day for three consecutive days (days 1–3) followed by evaluation with an accelerating rotarod assay and grip strength test three times per day for three consecutive days (days 4–6) and nerve electrophysiology and tissue harvest was performed on day 7. The Hargreaves test was performed on a separate batch of three-month-old mice.

Behavioral assays

Animals were randomized and the investigator was blinded to their genotypes during data collection and the same investigator performed all functional testing to avoid inter-examiner variability. Mice were first assessed with a modified neuromuscular Smith Kline Beecham, MRC Harwell, Imperial College, the Royal London Hospital phenotype assessment (SHIRPA) protocol29 and an inverted four limb wire grid holding test30. The modified SHIRPA protocol included fourteen non-invasive assessments in order to grossly assess functional neuromuscular phenotypes. Body position, spontaneous activity and tremor were scored with the mouse in the viewing jar. Transfer arousal, gait, pelvic elevation, tail elevation and touch escape were scored with the mouse in the arena. Positional passivity, trunk curl, limb grasping, toe pinch and hanging grasp were scored with the mouse above the arena. The maximum possible score was 49 which indicated that an animal was maximally affected whereas a score of 0 indicated that an animal was unimpaired. The inverted four limb 8 wire grid holding test assesses the ability of an animal to produce sustained limb muscle tension as a readout of skeletal muscle strength. The mouse was placed in hollow cylinder (20cm diameter) with wire mesh stretched across the bottom, the cylinder was inverted, and the time elapsed before the animal falls was recorded. Performance on this test was reported as holding impulse which is the hanging time in seconds multiplied by the body weight in Newtons. Both tests were performed three times per day for three consecutive days with sufficient rest time separating trials and the scores subsequently averaged for data analysis.

Mice were subsequently evaluated with an accelerating rotarod assay31 and a forelimb grip strength test32 to assess motor coordination and balance and skeletal muscle strength, respectively. Mice were given a training period on the rotarod followed by the data collection period with an initial speed of 4 rpm, which increased by 0.5 rpm every 10 seconds to a maximum speed of 40 rpm. Latency to fall was recorded. Forelimb grip strength was evaluated by quantifying the peak pull force in grams using a vertical force transducer apparatus to minimize variability. Both tests were performed three times per day for three consecutive days with sufficient rest time separating trials and the scores subsequently averaged for data analysis.

The Hargreaves test was performed to evaluate sensory function following an established protocol33. Briefly, a light source emitting heat increasing from 10% to 35% of the maximum intensity was focused on the medial plantar surface of the hind left foot and the time taken to lift the paw in seconds was recorded eight times with sufficient rest time separating trials.

Nerve electrophysiology

Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and the hair was removed from their hind quarters. Animals were then gently secured to the working surface; body temperature was maintained at 37° C using a heating pad and isoflurane anesthesia was continuously administered (flow rate 2 L/min). The sciatic nerve was exposed by making a 1–2 cm incision from the sciatic notch to above the knee and gently separating the gluteus maximus and biceps femoris. Recording electrodes were placed in the foot pad with the cathode 2 mm distal to the anode and stimulating electrodes were first placed near the sciatic notch with the cathode 2 mm proximal to the anode (proximal stimulation). A ground electrode was placed in the flank in between the stimulating and recording 9 electrodes. The nerve was stimulated with PowerLab (ADInstruments) using increasing voltage until supramaximal stimulation was achieved, with two to three minutes of rest allowed between stimulations to allow the nerve to return to baseline. The stimulating electrodes were then positioned 1 cm closer to the recording electrodes and the nerve was stimulated following the same protocol (distal stimulation). LabChart Reader (ADInstruments) was used to quantify CMAP latency (delay from stimulation to response onset), CMAP amplitude (peak to peak from the strongest recorded response) and motor nerve conduction velocity (1 cm divided by the difference in time between the onset of positive peaks) were quantified for each animal.

Nerve morphometry

Immediately following electrophysiological examination, animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and tissues were harvested bilaterally. Sciatic nerves were immediately immersion fixed and processed for light microscopy following an established protocol34. Tiled images of the entire nerve cross section were acquired on a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 with a 63X oil objective. Axons were evaluated from four randomly placed squares of equal area in the tibial branch of the sciatic nerve. Myelin sheaths and axons were manually traced and counted using ImageJ and axon diameters and g-ratios were calculated from axon and axon plus myelin sheath areas. Total axon counts were calculated by measuring the total area of the tibial nerve cross section and multiplying the selected area axon counts by the total area/selected area factor.

Muscle morphometry

Gastrocnemius and soleus muscles were also harvested. Gastrocnemii were weighed and the mass was recorded. The muscles were then flash frozen, cryosectioned and immunostained for laminin following an established protocol35. Tiled images of the entire muscle cross section were acquired on a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 with a 20X objective. Myofiber area and maximum Feret diameter were quantified from three randomly placed squares of equal area and individual fibers were manually traced using ImageJ. Soleus muscles were fixed, cryoprotected, cryosection and free-floating cryosections were immunostained with anti-β-III-Tubulin and α-Bungarotoxin following an established protocol36. Muscle regions were imaged on a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal with a 40X objective. Neuromuscular junction innervation was evaluated qualitatively using Zeiss Zen Blue37.

Sample Size and Statistics

All experiments included three groups: wildtype, CMT1A and CMT1A/SARM1−/−. Therefore, groups were compared by one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s post-hoc test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Samples sizes were determined based on data variability and reduced samples sizes were utilized when appropriate to reduce animals and effort. Sample sizes were as follows (wildtype, CMT1A and CMT1A/SARM1−/−), behavior: three month (6, 3, 12), six month (5, 9, 8), electrophysiology: three month (7, 8, 7), six month (8, 6, 5), nerve morphometry: three month (4, 4, 4), six month (3, 3, 3), three month gastrocnemius mass (4, 6, 5), three month gastrocnemius area and Feret (3, 4, 3) and three month soleus neuromuscular junctions (2, 3, 4).

Results

Behavioral rescue assessment

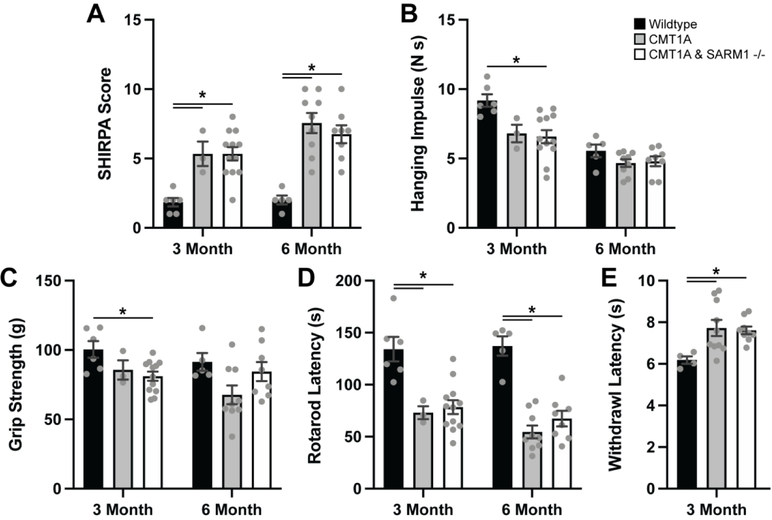

The CMT1A mouse model C3-PMP was utilized for our studies given that the genetic mutation closely resembles the human condition. Three- and six-month-old mice heterozygous for the C3-PMP transgene and homozygous for SARM1 knockout (CMT1A/SARM1−/−) along with wildtype (C57BL/6J) and CMT1A mice were evaluated with a series of behavioral assays. Neuromuscular SHIRPA was performed as an overall assessment of neuromuscular function. Scores were significantly increased in CMT1A mice at both ages as compared to wildtype controls and scores in CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice were comparably elevated (Fig. 1A). Inverted four limb wire grid holding test and forelimb grip strength test were employed to evaluate skeletal muscle strength. These assays were less sensitive for CMT1A; a significant deficit was not detected at either age with the inverted holding test and CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice performed similarly (Fig. 1B–C). An accelerating rotarod assay was used to assess motor coordination and balance. Latency to fall was significantly shorter in CMT1A mice at both ages as compared to wildtype controls and CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice were comparably affected (Fig. 1D). The Hargreaves test was performed on three-month-old mice to evaluate sensory function. CMT1A mice demonstrated a delayed withdrawal latency as compared to wildtype controls and CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice were similarly affected (Fig. 1E). These findings reveal that genetic deletion of SARM1 does not rescue behavioral deficits in CMT1A mice.

FIGURE 1: SARM1 knockout does not rescue CMT1A behavioral deficits.

Three- and six-month-old wildtype, CMT1A and CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice were evaluated by (A) neuromuscular SHIRPA, (B) inverted four limb wire grid holding test, (C) forelimb grip strength test, (D) accelerating rotarod assay and (E) Hargreaves test. n=3–12 animals per condition, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-hoc, *p<0.05.

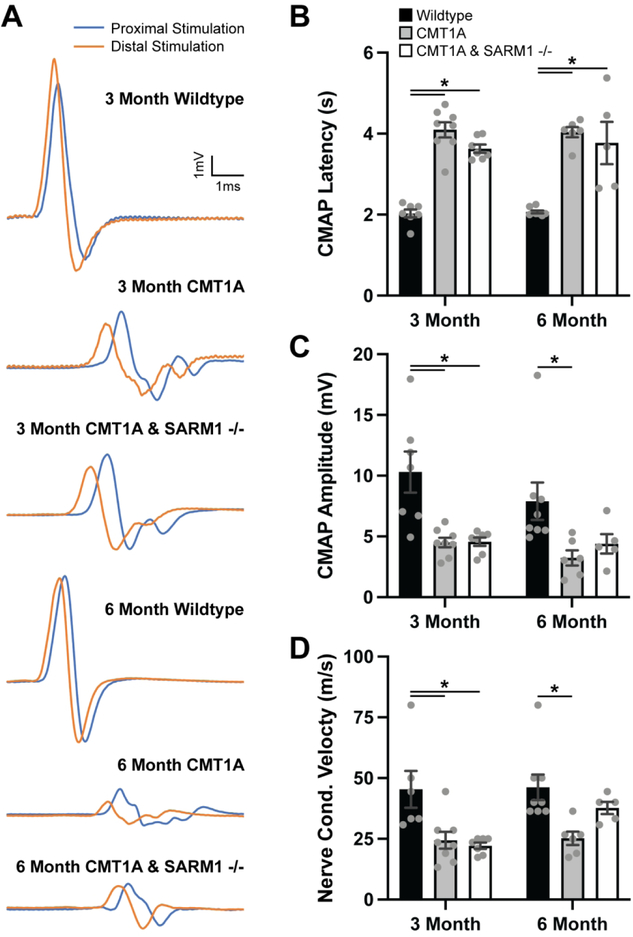

Electrophysiological rescue assessment

Evoked motor responses were recorded from tibial nerve-innervated intrinsic foot muscles in three- and six-month-old wildtype, CMT1A and CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice. CMT1A mice exhibited delayed CMAP latencies, reduced CMAP amplitudes and slowed conduction velocities at both ages as compared to wildtype controls (Fig. 2A–D). There was no statistically significant rescue of any of the electrophysiological outcome measures in either three- and six-month-old CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice (Fig. 2A–D).

FIGURE 2: SARM1 knockout does not rescue CMT1A electrophysiological deficits.

(A) Representative traces of evoked motor responses recorded from tibial nerve-innervated intrinsic foot muscles in three- and six-month-old wildtype, CMT1A and CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice. Quantification of (B) CMAP latency, (C) CMAP amplitude and (D) nerve conduction velocity are displayed. n=5–8 animals per condition, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-hoc, *p<0.05.

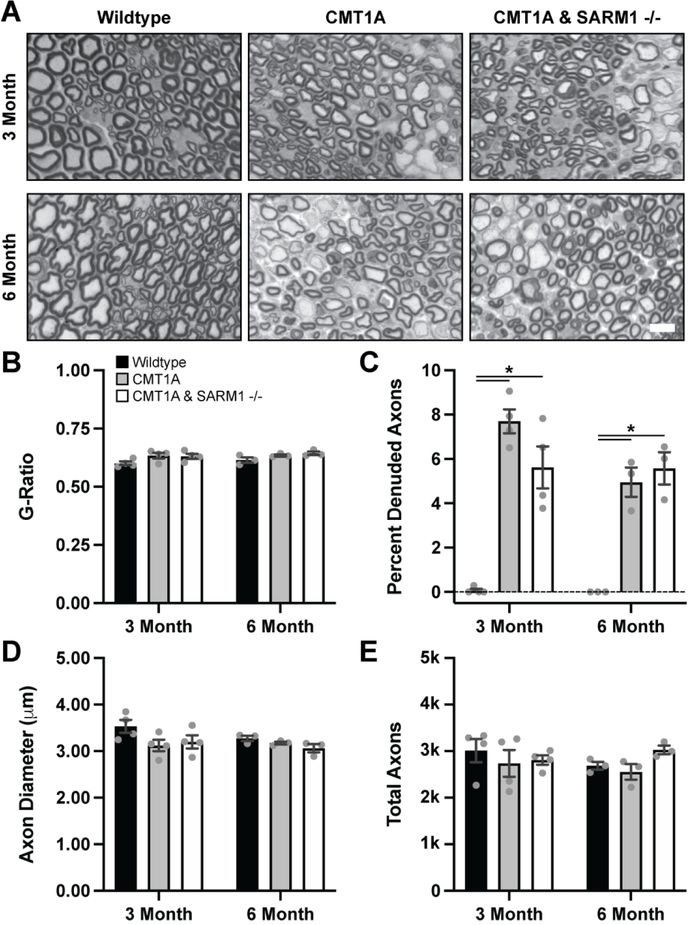

Histological rescue assessment

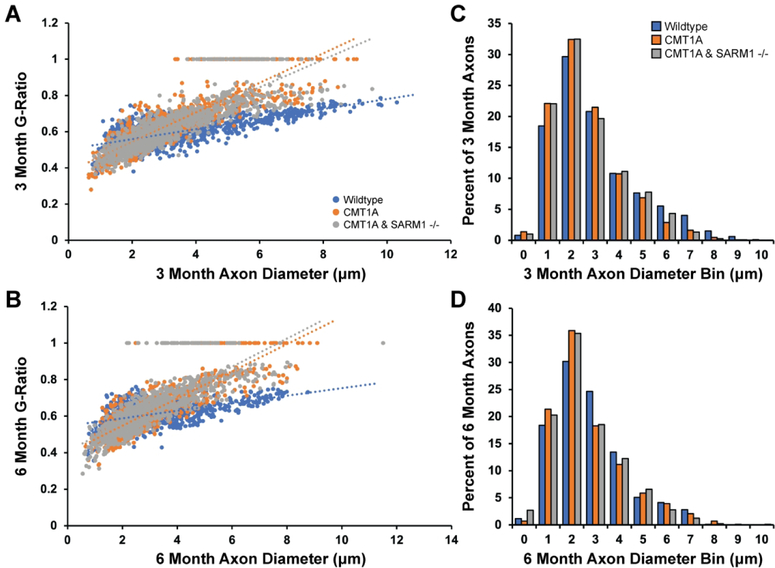

Histological analysis of the tibial branch of the sciatic nerve by light microscopy was performed to evaluate nerve morphology. Given that SARM1 knockout did not rescue the behavioral and electrophysiological deficits in CMT1A mice, we used reduced sample sizes for this experiment. Clear myelin deficits were visible qualitatively in CMT1A mice but average G-Ratios were not significantly altered as compared to wildtype controls or CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice at both ages (Fig. 3A–B). However, the percent of denuded axons was significantly increased in CMT1A mice as compared to wildtype controls at both ages (Fig. 3C). Percent denuded axons was also increased in CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice, comparably to CMT1A mice at both ages (Fig. 3C). Average axon diameter and total axon counts were not significantly altered as compared to wildtype controls or CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice at both ages (Fig. 3D–E). However, further analysis clearly demonstrates myelin and axonal deficits in CMT1A mice. Trendlines for G-Ratio against axon diameter plots demonstrate that G-Ratios were more consistent across different axon calibers in wildtype mice but exhibited a positive correlation between the two variables in CMT1A and CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice at both ages (Fig. 4A–B). This finding indicates that small caliber axons are hypermyelinated and large caliber axons are hypomyelinated in CMT1A mice, as reported previously in CMT1A rats26, and CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice at both ages. Additionally, axon diameter histograms revealed a loss of large caliber myelinated axons in CMT1A mice as compared to wildtype controls at three months and a further loss of larger caliber myelinated axons at six months (Fig. 4C–D). CMT1A/SARM1−/− axon diameters were shifted comparably to CMT1A at both ages; the percent of axons with large diameters was reduced and the percent of axons with smaller diameters was increased (Fig. 4C–D). These findings demonstrate that genetic deletion of SARM1 does not rescue nerve morphology deficits in CMT1A mice.

FIGURE 3: SARM1 knockout does not rescue CMT1A nerve morphology deficits.

Sciatic nerves were harvested from three- and six-month-old wildtype, CMT1A and CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice and plastic sections were prepared for light microscopy. (A) Representative images, scale bar 10 μm. Nerve morphometry was performed and average (B) G-Ratios, (C) percent denuded axons, (D) axon diameter and (E) total axons are displayed. n=3–4 animals per condition (>240 axons per animal), one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-hoc, *p<0.05.

FIGURE 4: SARM1 knockout does not improve CMT1A myelin and axon caliber deficits.

Data from Figure 3 were further analyzed by (A, B) plotting G-Ratio against axon diameter and (C, D) creating axon diameter histograms.

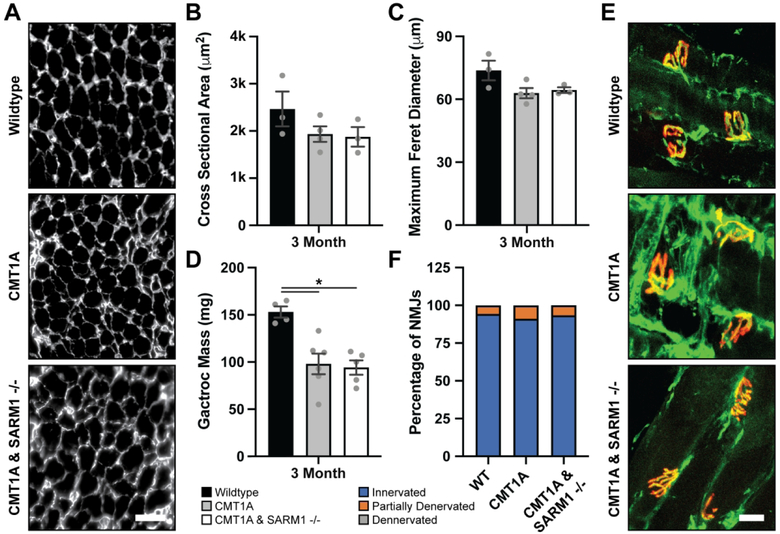

Histological analysis of gastrocnemius and soleus muscles by fluorescence microscopy was performed to evaluate muscle morphology. Reduced sample sizes were also used for these experiments due to the lack of rescue observed above. Average gastrocnemius muscle mass was significantly reduced in CMT1A mice as compared to wildtype controls, and CMT1A/SARM1−/− muscle mass was comparably reduced (Fig. 5D). Although average gastrocnemius muscle fiber cross sectional area and maximum Feret diameter exhibited a trend towards reduction in CMT1A mice as compared to wildtype controls, there were no statistically significant differences across groups at three months (Fig. 5A–C). Soleus muscle neuromuscular junction innervation was scored as innervated, partially denervated and denervated. There were no significant differences across groups at three months. (Fig. 5E–F). These results demonstrate that genetic deletion of SARM1 does not rescue muscle morphology in CMT1A mice.

FIGURE 5: SARM1 knockout does not rescue CMT1A muscle morphology deficits.

Gastrocnemius muscles were harvested from three-month-old wildtype, CMT1A and CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice, weighed and processed for immunohistochemistry with an anti-Laminin antibody. (A) Representative images, scale bar 100 μm. Average (B) myofiber cross sectional area, (C) myofiber maximum Feret diameter and (D) muscle mass are displayed. (B, C) n=3–4 animals per condition (>390 myofibers per animal), (D) n=4–6 animals per condition, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post-hoc, *p<0.05. Soleus muscles were harvested from three-month-old wildtype, CMT1A and CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice and processed for immunohistochemistry with an anti-β-III-Tubulin (green) antibody and α-Bungarotoxin (red). (E) Representative images, scale bar 10 μm. (F) Neuromuscular junction innervation was scored as innervated, partially denervated and denervated and the percent of total in each group is displayed. n=2–4 animals per condition (>30 NMJs per animal), Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA, Dunn’s post-hoc.

Discussion

Targeting the programmed axon degeneration pathway has become an appealing therapeutic strategy for neurological disorders given the often-dramatic neuroprotective effects observed upon its inhibition4, 38, 39. SARM1 depletion or inhibition is particularly attractive due to the long-term protection conferred by its depletion25. Axon degeneration is a common theme in CMT, and secondary axon degeneration is widely believed to be the primary driver of functional deficits in CMT1A patients3, 40. This motivated interrogation of programmed axon degeneration pathway inhibition as a potential therapy for CMT1A. Rescue of behavioral, electrophysiological, and histological deficits in a rat model of CMT1A was previously evaluated by introducing the WldS transgene. The authors reported a potential improvement in forelimb grip strength and modest improvements in tail electrophysiology and tibial nerve axon numbers in 10- to 13-week-old mice26. This modest phenotype rescue brings into question the biological significance of this effect especially due to the unclear improvement in muscle function. To build upon these potentially promising results, we utilized genetic deletion of SARM1 to better inhibit the programmed axon degeneration pathway and performed a thorough evaluation of nerve and muscle function in mature mice.

Overall, our results indicate that genetic deletion of SARM1 does not provide any significant improvement of CMT1A deficits. Although some of our experiments were performed with reduced sample sizes, our results with CMT1A mice are consistent with a previous report27 and CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice consistently show no rescue of neuromuscular deficits. Neuromuscular SHIRPA has previously been reported to detect behavioral deficits in CMT1A mice and this finding is supported by our results27. We also detected deficits in CMT1A mice with an accelerating rotarod assay and the Hargreaves test. However, CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice did not perform better in any of these assays. The inverted holding test and forelimb grip strength test were less reliable at detecting deficits in these mice and may suggest that assays including forelimb function are less sensitive, likely due to the nature of CMT1A to initially affect the longer axons in hindlimbs. These results warrant the use of hindlimb grip strength assays for future studies with these mice. Our electrophysiological assessment of CMT1A mice was also consistent with a previous report27 but CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice did not show a significant rescue of any of the electrophysiological outcome measures. Our nerve morphometry analysis demonstrated there was not a significant reduction in the number of axons in the tibial branch of the sciatic nerve in three- and six-month CMT1A mice. However, a small amount of axon degeneration is likely occurring given the loss of large caliber myelinated axons in CMT1A mice as compared to wildtype controls. However, total axon numbers and all other nerve morphology deficits were not significantly rescued by genetic deletion of SARM1 in CMT1A mice. Additionally, muscle morphology deficits were not significantly rescued in CMT1A/SARM1−/− mice as compared to CMT1A mice.

Although our results suggest that SARM1 knockout does not rescue CMT1A deficits, there are several factors that require further consideration. C3-PMP mice and additional CMT1A rodent models40 exhibit dramatically reduced CMAP amplitudes and clinical phenotypes early on but our nerve and muscle morphometry do not support an abundance of secondary axon degeneration. Therefore, these phenotypes must be caused by prolonged dysmyelination and consequent conduction block. This revelation motivates further investigation into mechanisms of dysmyelination in C3-PMP CMT1A mice. More severe CMT1A rodent models, those containing additional PMP22 transgenes, may exhibit more axonal degeneration40 and thus SARM1 knockout may confer neuroprotection. However, it is unlikely that the severe behavioral deficits observed in these mice41 will be improved by SARM1 knockout given the dramatic contribution of prolonged dysmyelination to these phenotypes as demonstrated by our data with C3-PMP mice. Additionally, although CMT1A/WldS +/− rats only showed modest improvements, it may be worth considering that global overexpression of WldS may cause neuroprotective effects in non-neuronal cells (i.e. Schwann cells) that cannot be provided by SARM1 global knockout. Conversely, it is possible that programmed axon degeneration pathway inhibition does not contribute to the secondary axon degeneration observed in CMT1A patients and the modest axonal deficits in CMT1A mice. There are several studies that show no neuroprotection upon programmed axon pathway inhibition in other neurological disease models supporting the idea that alternative axon degeneration pathways exist38, 42, 43. However, studying secondary axon degeneration in CMT1A mice is currently limited due to the poor recapitulation of this pathogenic process. Our results and others therefore motivate the development of improved CMT1A rodent models.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Aysel Cetinkaya-Fisgin and Dr. Ruifa Mi for providing training for behavioral and electrophysiological assays. We would also like to acknowledge the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Behavioral Core for providing guidance and training for behavioral assays. Dr. Kathryn Moss is supported by the Maryland Stem cell Research Fund Postdoctoral fellowship. Dr. Ahmet Hoke is supported by Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation and NIHR01 NS091260.

Competing interests:

Dr. Hoke served on the Scientific Advisory Board of Disarm Therapeutics. Under a license agreement between AxoProtego Therapeutics LLC and the Johns Hopkins University, Dr. Hoke and the University are entitled to royalty distributions related to the technology described in the study and discussed in this publication. Dr. Hoke also is a founder and serves as the Chair of AxoProtego Therapeutics LLC’s, Scientific Advisory Board. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies.

Footnotes

Data and materials availability:

All the data is reported in the full manuscript. Mice used in the study are available from commercial sources and they are listed in the methods and materials section.

References

- 1.Martyn CN, Hughes RA. Epidemiology of peripheral neuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997; 62(4): 310–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennan KM, Bai Y, Shy ME. Demyelinating CMT--what’s known, what’s new and what’s in store? Neurosci Lett. 2015; 59614–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krajewski KM, Lewis RA, Fuerst DR, Turansky C, Hinderer SR, Garbern J, Kamholz J, Shy ME. Neurological dysfunction and axonal degeneration in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2000; 123 (Pt 7)1516–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman MP, Hoke A. Programmed axon degeneration: from mouse to mechanism to medicine. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2020; 21(4): 183–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang MS, Davis AA, Culver DG, Glass JD. WldS mice are resistant to paclitaxel (taxol) neuropathy. Annals of neurology. 2002; 52(4): 442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang MS, Fang G, Culver DG, Davis AA, Rich MM, Glass JD. The WldS protein protects against axonal degeneration: a model of gene therapy for peripheral neuropathy. Annals of neurology. 2001; 50(6): 773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beirowski B, Babetto E, Coleman MP, Martin KR. The WldS gene delays axonal but not somatic degeneration in a rat glaucoma model. Eur J Neurosci. 2008; 28(6): 1166–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell GR, Libby RT, Jakobs TC, Smith RS, Phalan FC, Barter JW, Barbay JM, Marchant JK, Mahesh N, Porciatti V, Whitmore AV, Masland RH, John SW. Axons of retinal ganglion cells are insulted in the optic nerve early in DBA/2J glaucoma. J Cell Biol. 2007; 179(7): 1523–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu Y, Zhang L, Sasaki Y, Milbrandt J, Gidday JM. Protection of mouse retinal ganglion cell axons and soma from glaucomatous and ischemic injury by cytoplasmic overexpression of Nmnat1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54(1): 25–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaneko S, Wang J, Kaneko M, Yiu G, Hurrell JM, Chitnis T, Khoury SJ, He Z. Protecting axonal degeneration by increasing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide levels in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis models. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006; 26(38): 9794–9804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng HC, Burke RE. The Wld(S) mutation delays anterograde, but not retrograde, axonal degeneration of the dopaminergic nigro-striatal pathway in vivo. Journal of neurochemistry. 2010; 113(3): 683–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasbani DM, O’Malley KL. Wld(S) mice are protected against the Parkinsonian mimetic MPTP. Experimental neurology. 2006; 202(1): 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sajadi A, Schneider BL, Aebischer P. Wlds-mediated protection of dopaminergic fibers in an animal model of Parkinson disease. Current biology : CB. 2004; 14(4): 326–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferri A, Sanes JR, Coleman MP, Cunningham JM, Kato AC. Inhibiting axon degeneration and synapse loss attenuates apoptosis and disease progression in a mouse model of motoneuron disease . Current biology : CB. 2003; 13(8): 669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox GB, Faden AI. Traumatic brain injury causes delayed motor and cognitive impairment in a mutant mouse strain known to exhibit delayed Wallerian degeneration. J Neurosci Res. 1998; 53(6): 718–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin TC, Voorhees JR, Genova RM, Davis KC, Madison AM, Britt JK, Cintron-Perez CJ, McDaniel L, Harper MM, Pieper AA. Acute Axonal Degeneration Drives Development of Cognitive, Motor, and Visual Deficits after Blast-Mediated Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice. eNeuro. 2016; 3(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White MA, Lin Z, Kim E, Henstridge CM, Pena Altamira E, Hunt CK, Burchill E, Callaghan I, Loreto A, Brown-Wright H, Mead R, Simmons C, Cash D, Coleman MP, Sreedharan J. Sarm1 deletion suppresses TDP-43-linked motor neuron degeneration and cortical spine loss. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019; 7(1): 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geisler S, Doan RA, Cheng GC, Cetinkaya-Fisgin A, Huang SX, Hoke A, Milbrandt J, DiAntonio A. Vincristine and bortezomib use distinct upstream mechanisms to activate a common SARM1-dependent axon degeneration program. JCI Insight. 2019; 4(17). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geisler S, Doan RA, Strickland A, Huang X, Milbrandt J, DiAntonio A. Prevention of vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy by genetic deletion of SARM1 in mice. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2016; 139(Pt 12): 3092–3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turkiew E, Falconer D, Reed N, Hoke A. Deletion of Sarm1 gene is neuroprotective in two models of peripheral neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2017; 22(3): 162–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henninger N, Bouley J, Sikoglu EM, An J, Moore CM, King JA, Bowser R, Freeman MR, Brown RH Jr. Attenuated traumatic axonal injury and improved functional outcome after traumatic brain injury in mice lacking Sarm1. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2016; 139(Pt 4): 1094–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ziogas NK, Koliatsos VE. Primary Traumatic Axonopathy in Mice Subjected to Impact Acceleration: A Reappraisal of Pathology and Mechanisms with High-Resolution Anatomical Methods. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2018; 38(16): 4031–4047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozaki E, Gibbons L, Neto NG, Kenna P, Carty M, Humphries M, Humphries P, Campbell M, Monaghan M, Bowie A, Doyle SL. SARM1 deficiency promotes rod and cone photoreceptor cell survival in a model of retinal degeneration. Life Sci Alliance. 2020; 3(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sasaki Y, Kakita H, Kubota S, Sene A, Lee TJ, Ban N, Dong Z, Lin JB, Boye SL, DiAntonio A, Boye SE, Apte RS, Milbrandt J. SARM1 depletion rescues NMNAT1 dependent photoreceptor cell death and retinal degeneration. bioRxiv. 2020; 2020.2004.2030.069385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilley J, Ribchester RR, Coleman MP. Sarm1 Deletion, but Not Wld(S), Confers Lifelong Rescue in a Mouse Model of Severe Axonopathy. Cell reports. 2017; 21(1): 10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer zu Horste G, Miesbach TA, Muller JI, Fledrich R, Stassart RM, Kieseier BC, Coleman MP, Sereda MW. The Wlds transgene reduces axon loss in a Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease 1A rat model and nicotinamide delays post-traumatic axonal degeneration. Neurobiology of disease. 2011; 42(1): 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verhamme C, King RH, ten Asbroek AL, Muddle JR, Nourallah M, Wolterman R, Baas F, van Schaik IN. Myelin and axon pathology in a long-term study of PMP22-overexpressing mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011; 70(5): 386–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim Y, Zhou P, Qian L, Chuang JZ, Lee J, Li C, Iadecola C, Nathan C, Ding A. MyD88–5 links mitochondria, microtubules, and JNK3 in neurons and regulates neuronal survival. J Exp Med. 2007; 204(9): 2063–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers DC, Fisher EM, Brown SD, Peters J, Hunter AJ, Martin JE. Behavioral and functional analysis of mouse phenotype: SHIRPA, a proposed protocol for comprehensive phenotype assessment. Mamm Genome. 1997; 8(10): 711–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlson CG, Rutter J, Bledsoe C, Singh R, Hoff H, Bruemmer K, Sesti J, Gatti F, Berge J, McCarthy L. A simple protocol for assessing inter-trial and inter-examiner reliability for two noninvasive measures of limb muscle strength. J Neurosci Methods. 2010; 186(2): 226–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curzon P, Zhang M, Radek RJ, Fox GB (2009). The Behavioral Assessment of Sensorimotor Processes in the Mouse: Acoustic Startle, Sensory Gating, Locomotor Activity, Rotarod, and Beam Walking. In: Methods of Behavior Analysis in Neuroscience. nd, Buccafusco JJ (Eds), Boca Raton (FL). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeshita H, Yamamoto K, Nozato S, Inagaki T, Tsuchimochi H, Shirai M, Yamamoto R, Imaizumi Y, Hongyo K, Yokoyama S, Takeda M, Oguro R, Takami Y, Itoh N, Takeya Y, Sugimoto K, Fukada SI, Rakugi H. Modified forelimb grip strength test detects aging-associated physiological decline in skeletal muscle function in male mice. Sci Rep. 2017; 742323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu J, Chen W, Mi R, Zhou C, Reed N, Hoke A. Ethoxyquin prevents chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity via Hsp90 modulation. Annals of neurology. 2013; 74(6): 893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheib JL, Hoke A. An attenuated immune response by Schwann cells and macrophages inhibits nerve regeneration in aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2016; 451–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ehmsen JT, Kawaguchi R, Mi R, Coppola G, Hoke A. Longitudinal RNA-Seq analysis of acute and chronic neurogenic skeletal muscle atrophy. Sci Data. 2019; 6(1): 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung T, Park JS, Kim S, Montes N, Walston J, Hoke A. Evidence for dying-back axonal degeneration in age-associated skeletal muscle decline. Muscle Nerve. 2017; 55(6): 894–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright MC, Mi R, Connor E, Reed N, Vyas A, Alspalter M, Coppola G, Geschwind DH, Brushart TM, Hoke A. Novel roles for osteopontin and clusterin in peripheral motor and sensory axon regeneration. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2014; 34(5): 1689–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conforti L, Gilley J, Coleman MP. Wallerian degeneration: an emerging axon death pathway linking injury and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014; 15(6): 394–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moss KR, Hoke A. Targeting the programmed axon degeneration pathway as a potential therapeutic for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Brain Res. 2020; 1727146539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moss KR, Bopp TS, Johnson AE, Hoke A. New evidence for secondary axonal degeneration in demyelinating neuropathies. Neurosci Lett. 2021; 744135595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huxley C, Passage E, Manson A, Putzu G, Figarella-Branger D, Pellissier JF, Fontes M. Construction of a mouse model of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A by pronuclear injection of human YAC DNA. Hum Mol Genet. 1996; 5(5): 563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peters OM, Lewis EA, Osterloh JM, Weiss A, Salameh JS, Metterville J, Brown RH, Freeman MR. Loss of Sarm1 does not suppress motor neuron degeneration in the SOD1G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2018; 27(21): 3761–3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peters OM, Weiss A, Metterville J, Song L, Logan R, Smith GA, Schwarzschild MA, Mueller C, Brown RH, Freeman M. Genetic diversity of axon degenerative mechanisms in models of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of disease. 2021; 155105368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]