Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignancy of plasma cells accounting for approximately 12% of hematological malignancies. In this study, we report the fabrication of a high-content in vitro MM model using a coaxial extrusion bioprinting method, allowing formation of a human bone marrow-like microenvironment featuring an outer mineral-containing sheath and the inner soft hydrogel-based core. MM cells were mono-cultured or co-cultured with HS5 stromal cells that could release interleukin-6 (IL-6), where the cells showed superior behaviors and responses to bortezomib in our 3D models than in the planar cultures. Tocilizumab, a recombinant humanized anti-IL-6 receptor (IL-6R), was investigated for its efficacy to enhance the chemosensitivity of bortezomib on MM cells cultured in the 3D model by inhibiting IL-6R. More excitingly, in a proof-of-concept demonstration, we revealed that patient-derived MM cells could be maintained in our 3D-bioprinted microenvironment with decent viability for up to 7 days evaluated, whereas they completely died off in planar culture as soon as 5 days. In conclusion, a 3D-bioprinted MM model was fabricated to emulate some characteristics of the human bone marrow to promote growth and proliferation of the encapsulated MM cells, providing new insights for MM modeling, drug development, and personalized therapy in the future.

Keywords: multiple myeloma, bioprinting, coaxial extrusion, bortezomib, tocilizumab

The Table of Content Entry

The fabrication of a high-content in vitro multiple myeloma (MM) model using a coaxial extrusion bioprinting method is reported, allowing formation of a human bone marrow-like microenvironment featuring an outer mineral-containing sheath and the inner soft hydrogel-based core. MM cells were mono-cultured or co-cultured with HS5 stromal cells to study their chemosensitivity to therapeutic agents. This model emulates some characteristics of the human bone marrow to promote growth and proliferation of the encapsulated MM cells, providing new insights for MM modeling, drug development, and personalized therapy in the future.

1. Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most common malignant hematologic disease, and is incurable, with an incidence rate of 4-5 cases per 100,000 per year.[1–3] MM arises in the hematopoietic bone marrow and is reflected by the over-proliferation of abnormal plasma cells derived from B cells. MM presents with four main features: bone destruction, renal dysfunction, hypercalcemia, and anemia.[4] Although the administration of certain therapeutics such as immunomodulatory agents, proteasome-inhibitors, and autologous stem cell transplants (ASCTs) markedly improve MM treatment and survival, nearly all patients will eventually relapse.[5, 6] One of the challenges in the treatment of this deadly disease lies in the fact that it is very difficult to eliminate residual MM cells, even when high-dose chemotherapy is applied followed by ASCT.[7, 8]

In 2004, when the first proteasome-inhibitor bortezomib (BTZ) was introduced, it dramatically changed the landscape of MM treatment; now almost all myeloma patients will receive BTZ during their course of treatment.[9] BTZ can induce deeper responses, lead to higher response rates, and extend the survival of patients with newly diagnosed MM or relapsed MM than other agents.[6, 10] The primary mechanism of action of BTZ is inhibition of the chymotrypsin-like site of the 20S proteolytic core within the 26S proteasome, which induces apoptosis and affects the tumor microenvironment by blocking cytokine interactions, cell activities, as well as angiogenesis.[11, 12] Unfortunately, BTZ has also been associated with some toxic side effects, such as hemopenia, fatigue, gastrointestinal discomfort, and peripheral neuropathy. Even worse, nearly all patients will develop drug-resistance to BTZ.[13] Therefore, to improve the treatment of MM, BTZ drug-resistance must be characterized, investigated, and ultimately resolved.

Tumors grow and develop within microenvironments with specialized microdomains termed “niches” that regulate cancer cell functions and affect their survival and drug sensitivity.[14] MM almost exclusively develops within the bone marrow niche, where the myeloma cells establish close interactions with the extracellular matrix (ECM), which in turn produces pro-survival and anti-apoptotic signals, conferring undesired drug-resistance.[15] Thus, the tumor microenvironment stands as an extremely essential factor in MM biology and accordingly, also a rational target for the development of novel therapeutics.[16] Conventional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures may not mimic the natural physiology of the tumor microenvironment, and may affect measurement of the responses to drugs. Given this fact, three-dimensional (3D) models of MM cells inside native-mimicking microenvironments display unique advantages in terms of establishing proper cell functions and associated signaling pathways, making the evaluations of drug effects more efficient and accurate in a (patho)physiologically relevant context.[17–19]

Recently, 3D bioprinting has been explored extensively for forming well-organized volumetric structures of human tissues and organs,[20] which has also found increasing utility in tumor modeling in vitro.[21, 22] For example, we[23–28] and others[29–31] have previously reported the multichannel coaxial extrusion systems for bioprinting multilayered tubular tissues for various application scenarios. We thus hypothesized that, this unique tool permits generation of cannular constructs to mimic the bone marrow cavity, in which MM cells can be cultivated for screening antitumor drugs in a high-content manner (Scheme 1). Because the outer layer of the bone marrow is the hard tissue (cortical bone), our MM model was designed to further contain nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA), a primary mineral component of our skeletal system, in the sheath. nHA has shown favorable cyto/biocompatibility, bioactivity, as well as mechanical properties in previous demonstrations.[32–34]

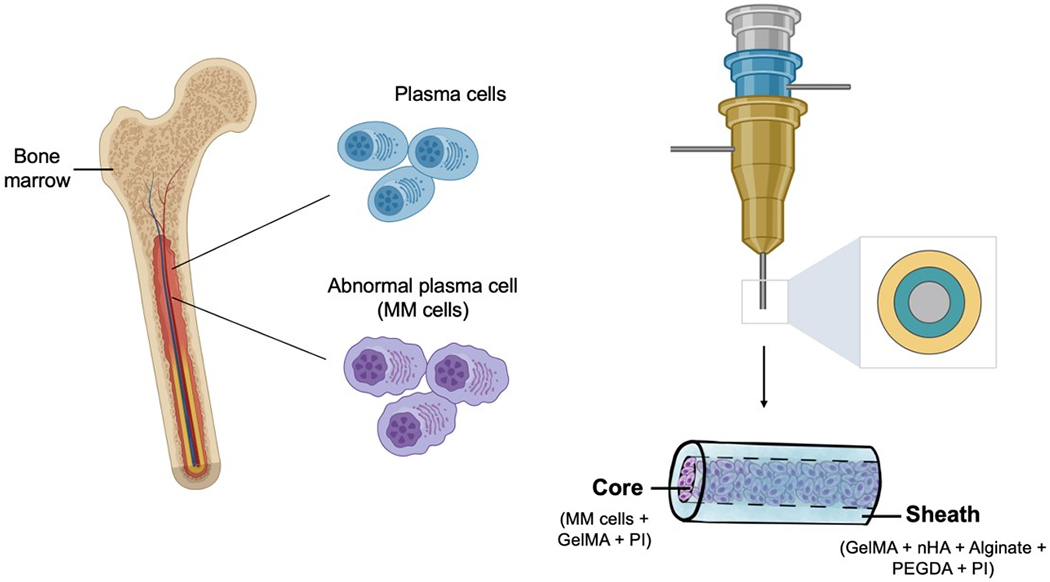

Scheme 1.

Schematics showing MM in vivo and the use of coaxial bioprinting for high-content in vitro modeling of MM.

On the other hand, interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a pathogenetically important cytokine in MM disease.[35] It is also a potent stimulator of osteoclastogenesis and the tumor microenvironment in the bone marrow of patients bearing MM.[36] It has been shown that adhesion of myeloma cells to other components within its native niche, such as the stromal cells in the bone marrow, triggers cytokine-mediated survival, growth, and drug-resistance of these tumor cells.[7, 37] Therefore, the bone marrow niche where myeloma cells reside in is critical for the understanding of MM pathophysiology, which also equally important to allow development of new therapeutic strategies for the treatment of the disease. Tocilizumab (TOC), an humanized anti-IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) antibody, has proven to be an effective and safe treatment option for inflammatory rheumatic diseases.[38] Therefore, we speculated that TOC blockade of the IL-6 pathway can be therapeutically useful for combating cell adhesion-mediated drug-resistance in MM.

In this study, we first established a 3D-bioprinted MM model using a customized bioink consisting of combinations of gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA), alginate, polyethylene glycol-diacrylate (PEGDA), nHA, and MM cells (Scheme 1). The hollow tubular construct was composed of the outer sheath and the inner core; the sheath was used to mimic the cortical bone surrounding while MM cells were cultivated in the inner core filled with a low-concentration GelMA representing the soft bone marrow. Finally, the use of TOC was investigated for its ability to enhance the chemosensitivity of BTZ on MM cells cultured in the 3D MM model.

2. Methods

Cells and Materials

MM1S and RPMI-8226 human myeloma cells (ATCC, USA) and their culture conditions have been previously described.[39] HS5 stromal cells (ATCC) were cultured using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, ThermoFisher, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (ThermoFisher). CaCl2, ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), PEGDA, and photoinitiator (PI, 2-hydroxy-4’-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropiophenone; purity: 98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity kit, and CellTracker™ Blue CMAC dye were purchased from ThermoFisher. Needles of different sizes (14G, 18G, and 25G) were purchased from BD Biosciences, USA. BTZ and TOC (Selleck, USA) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma-Aldrich) and stored at −20 °C.

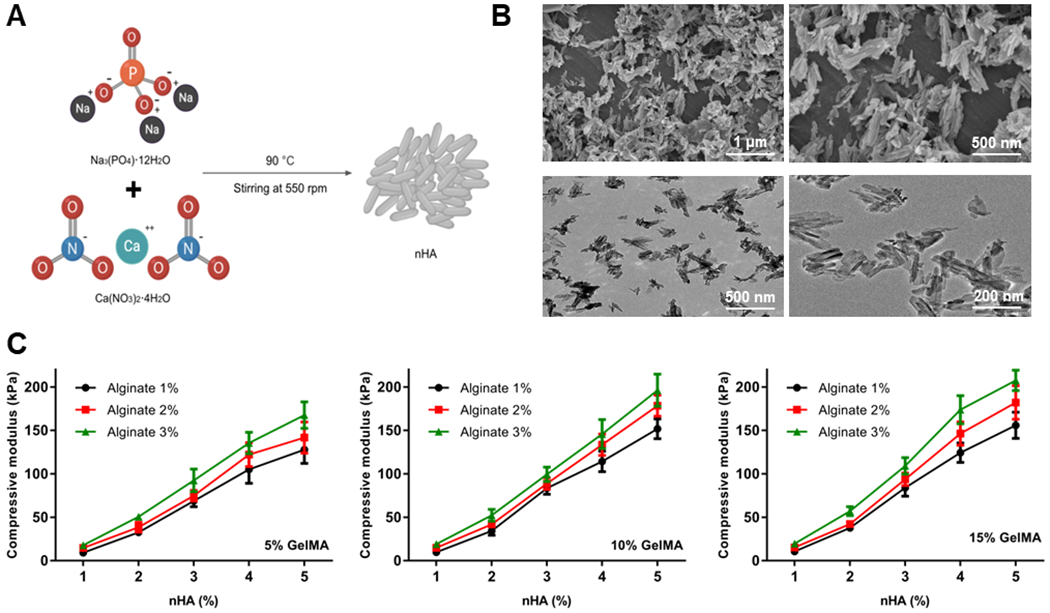

nHA Synthesis and Characterizations

We formed nHA by mixing Ca(NO3)2·12H2O and Na3(PO4)·4H2O together, then stirring overnight at 550 rpm and 90 °C (Figure 1A).[40] The surface morphologies of the nHA particles were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; XL30, PHILIPS, the Netherlands) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Hitachi, Japan).

Figure 1.

Characterizations of the sheath bioink. (A) Schematic diagram showing the preparation procedure of nHA. (B) SEM (top) and TEM (bottom) images of the nHA. (C) Compressive moduli of the hydrogels derived from different compositions of the bioinks. nHA, nano-hydroxyapatite; SEM, scanning electron microscopy; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Preparation of Bioinks

According to our previous bioprinting experiences in similar configurations,[23, 25, 26, 28, 41] the sheath bioinks were prepared by mixing different concentrations of GelMA, nHA, alginate, and PEGDA, and then added with 0.5 w/v% PI. All solutions were filtered with 0.22-μm syringe filters to sterilize. Meanwhile, the core bioink was prepared with 5 w/v% GelMA and 0.25 w/v% PI,[24] and then encapsulated with MM cells. This core bioink formulation was selected due to its low stiffness in the range of few kPa,[42] which is relevant to the bone marrow microenvironment.

Bioprinting Procedure

The bioprinting procedure largely followed our previously reported protocols.[23–26, 28, 41] A custom-designed coaxial nozzle device containing three injection channels with different needle sizes was manufactured. Briefly, needles of 25G, 18G, and 14G were used for delivering the inner core, the sheath, and the outer layer, respectively. The junction points were sealed permanently using epoxy glue (Devcon, USA). The needles were connected to three separate pumps for delivery via polyvinyl chloride tubes. The sheath bioink was delivered through the middle layer, while 0.33-M CaCl2 solution was delivered from the exterior to immediately crosslink the alginate component of the bioink and thereby yield the tubular structure. At the same time, the core bioink was delivered through the inner core to obtain the bone marrow-like environment. UV light was illuminated at 8.0 mW cm−2 for 40 s post-bioprinting for covalent crosslinking of the GelMA (both sheath and core bioinks) and PEGDA (sheath bioink) components. When necessary, the sheath/core bioinks were incorporated with fluorescence microbeads (Createxcolors, USA) prior to bioprinting to aid microscopic visualization.

Bioink Optimizations

We determined the mechanical properties of sheath bioinks having different compositions utilizing compression, rheology and printability assessments. To prepare the test samples, different concentrations of GelMA (5%, 10%, and 15% w/v), alginate (1%, 2%, and 3% w/v), and nHA (1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, and 5% w/v) were dissolved to form the variety of bioinks.

For the compression tests of the samples, the bioinks were both ionically crosslinked and photocrosslinked, similar to the case of bioprinting. The bioinks were then pipetted to a prepared cubic polydimethylsiloxane mold (5 × 5 × 5 mm3) and soaked in CaCl2 solution for 2 min, followed by exposure to 6.9 mW cm−2 of UV light for 40 s. During the testing, the compressive strengths of the samples were assessed at a cross speed of 30 mm s−1 and a 60% strain level according to previously reported procedures[23] using a mechanical testing machine (Instron Model 5542, USA).

The printability mapping of the bioinks was based on whether the bioinks could be smoothly extruded to form uniform tubular structures via the coaxial nozzle. Note that the feeding speeds of the CaCl2 solution and the sheath bioinks both determined the printability of the tubular structures. Once the feeding rates of these two solutions were set, the inner and outer diameters of the bioprinted core-sheath structures could be adjusted by the feeding rates of bioink of the core.

The rheological property of the final optimal sheath bioink was measured using a hybrid rheometer (HR-3, Waters, USA), as reported in our previous studies.[42, 43]

Cell Viability Assay

For 2D mono-culture, 5 × 104 MM1S or RPMI-8226 cells per well were seeded in 24-well plates; for 2D co-culture, 1 × 105 HS5 cells per well were stained with CellTracker and then seeded in 24-well plates, after which 5 × 104 MM1S or RPMI-8226 cells per well were seeded. For 3D mono-culture, MM1S or RPMI-8226 cells were mixed with the core bioinks, and then immediately bioprinted into tubes via the coaxial nozzle device; for 3D co-culture, similarly, HS5 cells were stained with 5-μM CellTracker and mixed with the core bioink together with MM1S or RPMI-8226 cells. For both 2D and 3D cultures, the initial cell numbers for the respective cell types were maintained roughly the same to allow fair comparisons. The concentration of MM1S or RPMI-8226 cells was accordingly set at 1× 105 mL−1 and it was 2× 105 mL−1 for HS5 cells. On different days (days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9), the cells were stained with the Live/Dead cell viability kit and observed using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Japan). Three samples per group and 5 fields of each sample were imaged and used to count and calculate the cell viability by using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

Dose-Responses of BTZ

BTZ was serially diluted to 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, and 1 nM and used as specified in each experiment. The 2D/3D mono- and co-cultures were prepared as indicated above. After the MM1S or RPMI-8226 cells were treated with different concentrations of BTZ (0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 nM) for 24 h, the Live/Dead cell viability kit was used to assess cell viability following the manufacturer’s instructions, and images were observed by a fluorescence microscope.

Combined BTZ/TOC Effects

Because TOC is known to block the IL-6 pathway and reverse the cell aggregation induced by BTZ, 2-μM tocilizumab was added to the 2D/3D mono- and co-culture systems together with different concentrations of BTZ (0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 nM). After determining the viability of cells treated with different concentrations of BTZ, we chose the optimal concentrations for the combined therapy. To detect the synergistic effect of BTZ and TOC, the combination indices (CIs) were calculated, for which the value of less than 1 indicates synergy.[44]

ELISA

The supernatants from the different cultures were collected, centrifuged, and stored at −20 °C. The level of IL-6 production in each group was assessed with a human IL-6 ELISA kit (R&D Systems, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Bioprinting with Patient-Derived MM Cells

Primary cells from two MM patients were obtained after informed consent was provided, in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board approved protocol, where the patient’s MM cells were isolated as described previously.[39, 45] Patient samples were de-identified prior to their use in experiments. We cultured these cells in the 2D and 3D culture systems, and treated with BTZ/TOC as described above. Due to the preciousness of the patient cells, a relatively low collective density at 1 × 105 mL−1 of the cells (likely a mixture of MM and stromal cells) were loaded into the core bioink and then bioprinted.

Statistical Analyses

All experiments were performed with at least three replicates per group except for the patient-derived MM cells. Data are representative of these experiments and are shown as the means ± standard deviations (SDs). Two treatment groups were compared by t-test, and multiple group comparisons were performed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post-hoc test. Statistical significance was declared as p<0.05.

3. Results and Discussions

nHA Morphology

We synthesized nHA with Ca(NO3)2·12H2O and Na3(PO4)·4H2O by the method of chemical precipitation (Figure 1A).[40] As shown in Figure 1B, SEM and TEM images displayed the nanoscale dimensions and shapes of the produced nHA, which had a length of 200-500 nm, a diameter of 20-30 nm, and an aspect ratio of 15-20. It is obvious that the surface of sheath bioink was rough and uneven (Figure S1), and this feature suggested that the nHA-containing bioink is suitable as a bone-mimicking material. The inorganic component of the human body is composed of hydroxyapatite [Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2] crystals and synthetic hydroxyapatite has been identified as a promising biomimetic bone mineral.[46, 47] To mimic the composition of the cortical bone surrounding the marrow, nHA is a good candidate as an appetite-substitute, because it is osteoconductive and provides sufficient mechanical strength. For example, composites consisting of nHA and hydrogel biomaterials, such as GelMA, have attracted increasing interest due to their potential in restoring structural and biological functions of damaged skeletal tissues, such as those of the cortical bone.[48]

Mechanical Properties of Bioinks

To optimize the performances of the sheath bioink, various concentrations of GelMA, alginate, and nHA were examined, with determinations of the compressive moduli and printability.

To measure the mechanics of the crosslinked bioinks, compression tests were conducted. Vacuum decompression was used to remove the air bubbles trapped inside the bioinks prior to testing.[49, 50] The results illustrated that that the compressive moduli of the crosslinked bioinks were elevated by increasing the concentrations of nHA and alginate (Figure 1C), although it should be noted that, these values might slightly differ from those of the actual bioprinted tubes due to the possible minor variations in crosslinking conditions when producing these samples. The enhanced mechanical strengths of the hydrogels could sufficiently support the shape fidelity of the hollow tubular constructs post-bioprinting and provide a bone-like microenvironment for the cells in the marrow area.

The apparent viscosities of the sheath bioinks increased compared to those of their individual components as shown by a slope test (Figure S2). Both GelMA and alginate could flow down the slope rapidly and exhibited very low viscosities, whereas the bioinks containing nHA exhibited slightly higher viscosity values with no noticeable movements even at the perpendicular surface.

Bioprinting of the Core-Sheath Structures

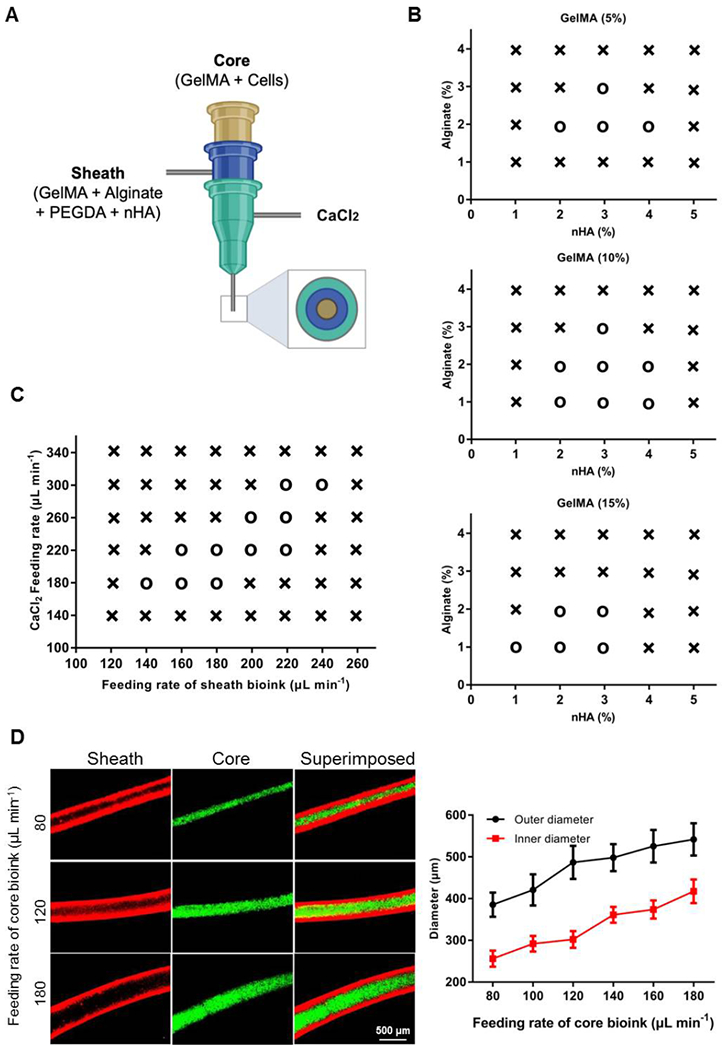

As shown in Figure 2A, we included nHA in our basic sheath bioink containing alginate, GelMA, and PEGDA, while GelMA and cells in the core bioink to formulate a 3D-bioprinted MM model. Printability evaluations of the bioinks of different compositions were performed by identifying generation of continuous fibers using a coaxial nozzle. For example, 2 w/v% alginate combined with 2 w/v% or 3 w/v% of nHA, together with any concentration of GelMA, could be smoothly bioprinted (Figure 2B). The hollow tubes could be produced continuously when the flow rate of the outer CaCl2 solution was equal to or slightly faster than that of the sheath bioink, when the flow rate of the inner (sheath) bioinks was set at a constant value (160 μL min−1, Figure 2C). Moreover, the inner/outer diameters of the bioprinted core-sheath structures exhibited a positive dependency on the feeding rate of the core bioink, when that of the sheath bioink was maintained at 160 μL min−1 (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Optimization of the bioinks and bioprinting conditions. (A) Schematic diagram showing the coaxial nozzle for bioprinting. (B) Printability mapping showing the effect of different concentrations of alginate/GelMA/nHA of the sheath bioinks. (C) Printability mapping showing the effect of feeding rates of the CaCl2 solution and the sheath bioink; the sheath bioink had a composition of GelMA, alginate, PEGDA and nHA, and the core bioink had a feeding rate of 120 μL min−1. (D) Modulation of inner/outer diameters of the bioprinted core-sheath structures as a function of the feeding rate of the core bioink; the sheath bioink had a composition of GelMA, alginate, PEGDA and nHA, and a feeding rate of 160 μL min−1. o: printable, ×: non-printable. nHA, nano-hydroxyapatite.

Based on these assessments, the optimum printability was decided at 10 w/v% GelMA, 2 w/v% alginate, and 3 w/v% nHA, which together with 1 w/v% PEGDA was formulated as the sheath bioink. The rheological behavior of this bioink is shown in Figure S3. Accordingly, the feeding rates of the core bioink (120 μL min−1), the sheath bioink (160 μL min−1), and the CaCl2 solution (180 μL min−1) were adopted in subsequent experiments. As such, the resulting fibrous constructs had an outer diameter of 486.84 ± 39.77 μm and an inner diameter of 291.70 ± 18.87 μm. The unique feature of our 3D strategy lies in its ability to fabricate hollow bone marrow-mimicking tubes with a mineral-containing, cortical bone-like sheath and a suitable core microenvironment for cell proliferation.[24] Indeed, it was shown that the distribution of nHA in the sheath of the tube seemed to be sufficiently uniform (Figure S4). It is also likely due to the shear effect the nHA particles could have adopted some degree of anisotropy during the bioprinting process,[51] which however, would require further analysis. Of note, while the sizes of the bioprinted tubes may not be directly relevant to the actual dimensions of the human cortical bones, they are supportive of convenient in vitro assays. As a matter of fact, such a model while high-content, can also be readily produced at scale, where meter-long fibers are easily obtained in minutes of bioprinting. Arbitrary 2D and 3D patterns are also possible,[23] yet there was no need for such additional complexity in this particular work.

In addition, we examined the swelling behaviors of the bioprinted tubular constructs. Observing from Figure S5, it was clear that the swelling was relatively obvious in the first 24 h at approximately 10%, which gradually plateaued at roughly 15% over time until 7 days tested. This result suggested decent stability of the bioprinted structures for the purpose of constructing our MM models.

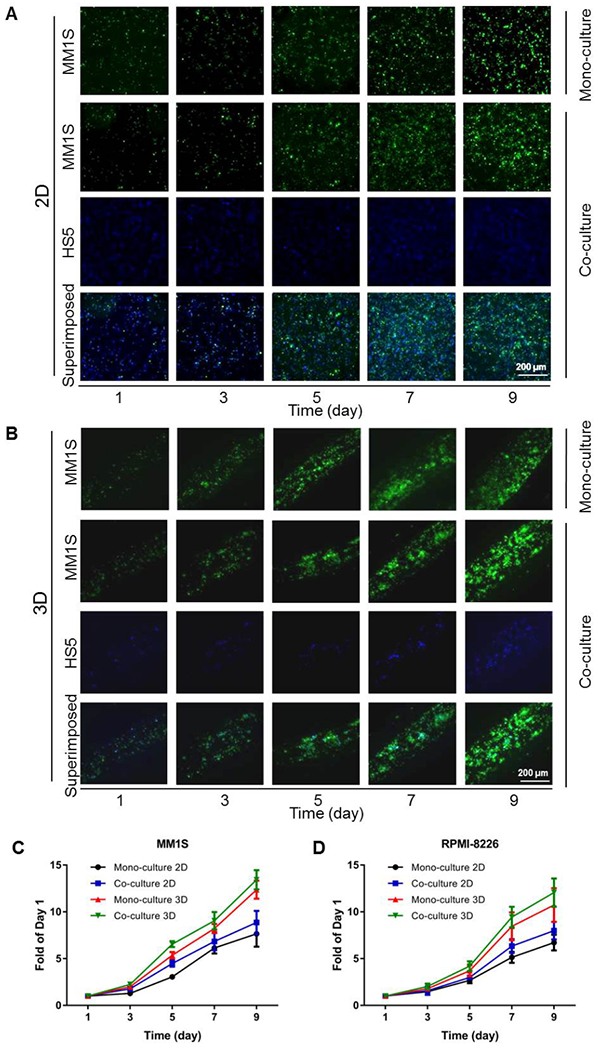

3D Cultures Promote MM Cell Proliferation Better Than 2D, and Co-Cultures Enhance Proliferation Compared to Mono-Cultures

HS5 stromal cells, which constitute the microenvironment for MM cells, secrete multiple cytokines to promote the anti-apoptosis and cell proliferation of hemopoietic progenitors.[52, 53] Figure 3A and B show the cell growth after culturing for up to 9 days in 2D and 3D culture systems, respectively, in both mono-cultures of MM1S cells and co-cultures of MM1S cells with HS5 cells. In the 2D culture system, the numbers of MM cells multiplied to 7.66 ± 1.37 times and 8.87 ± 1.24 by day 9 in mono-culture and co-culture, respectively, with only few dead cells present over the course of culture. The proliferation of co-cultured MM1S cells with HS5 cells was more obvious than that of mono-cultured MM1S cells after culturing for 3 days; similarly, this trend also appeared in the 3D culture system, i.e., in co-culture of MM1S cells and HS5 cells, the adherence of the MM1S cells to the HS5 cells was likely promoted, subsequently inducing the proliferation of the MM1S cells (Figure 3C). The qualification of the cell growth profiles of the other cell line RPMI-8226 verified this conclusion as well (Figure 3D), with the corresponding micrographs of cell proliferation displayed in Figure S6. In the 3D culture system, the numbers of cells proliferated to more than 10 times by day 9 (12.37 ± 0.96 times and 13.43 ± 1.03 in mono-culture and co-culture, respectively), significantly higher than fold-expansions in the corresponding 2D culture groups. Possibly due to the confined space and the 3D configuration in the bioprinted models, the MM cells also became more aggregated than those in 2D cultures. Yet similarly, few cells were observed to be dead during this culture period.

Figure 3.

MM cell proliferation in the 2D and 3D culture systems. (A) Fluorescence micrographs showing the growth of MM1S cells co-cultured with HS5 cells in 2D. (B) Fluorescence micrographs showing the growth of MM1S cells co-cultured with HS5 cells in 3D. (C) Growth curves of the MM1S mono- and co-cultures in both 2D and 3D. (D) Growth curves of RPMI-8226 mono- and co-cultures in both 2D and 3D.

Stromal cells, an important cellular population of the bone marrow, support MM cell survival, growth, and chemo-resistance.[7, 54] As such, 3D microtissue-based in vitro models were previously established to reproduce the development of MM cells inside the bone marrow microenvironment for investigating MM pathogenesis, progression, and drug-resistance.[55] The MM cell growth in our models has proven the potential advantages of using 3D rather than 2D systems in terms of emulating the MM behaviors. Moreover, co-culture was imperative in both 2D and 3D platforms in the promotion of MM cell proliferation.

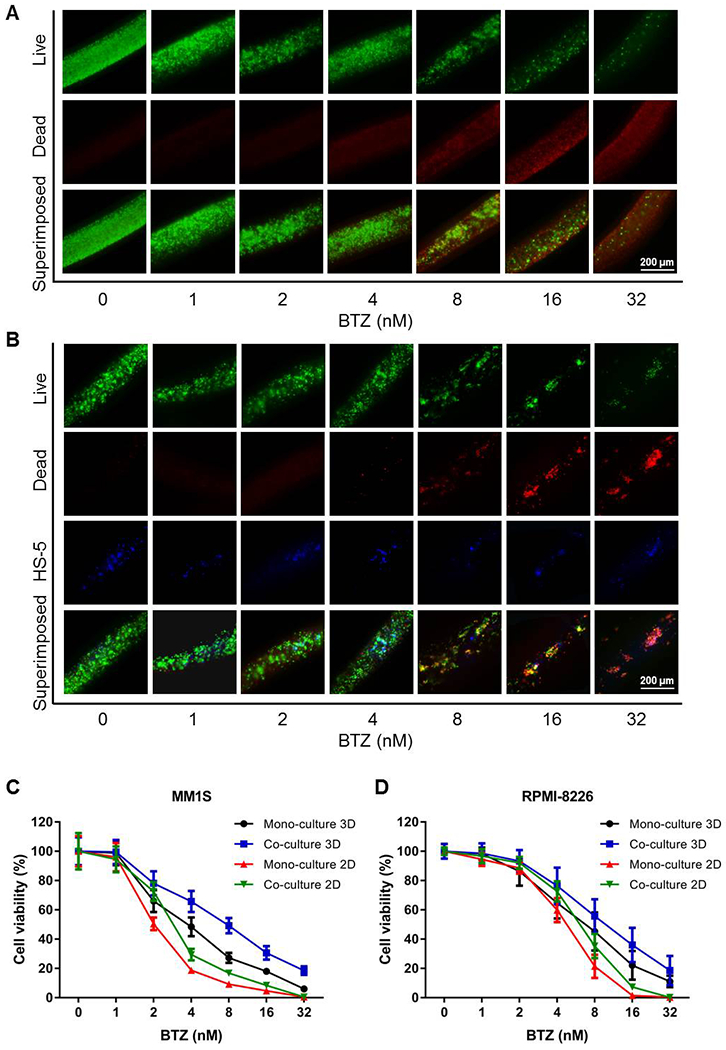

3D Culture Protects MM Cells from BTZ-Induced Cell Death

BTZ has been suggested to inhibit the proliferation of MM cells in a dose-dependent manner.[56] Indeed, Figure 4A and B show that incubation of the 3D co-culture model of MM1S cells and HS5 cells with 8 nM of BTZ for 24 h significantly decreased cell viability, as compared with the mono-culture of MM1S cells (cell viabilities: 49.21 ± 5.27% vs. 27.21 ± 3.39% at 8-nM BTZ; 30.61 ± 4.61% vs. 18.01 ± 2.13% at 16-nM BTZ; and 18.51 ± 2.97% vs. 6.00 ± 0.69% at 32-nM BTZ; p<0.05 in all cases; Figure 4C). Similarly, it was also confirmed that BTZ significantly inhibited RPMI-8226 cell proliferation at the concentrations of 8 nM and above in our 3D model compared between co-culture and mono-culture (Figure 4D and Figure S7). The cell viability values in the co-culture and mono-culture systems were 55.75 ± 7.46% vs. 35.26 ± 4.99% at 8 nM of BTZ; 39.03 ± 5.72% vs. 22.19 ± 2.83% at 16 nM of BTZ; and 18.61 ± 2.91% vs. 7.10 ± 0.93% at 32 nM of BTZ (p<0.05 in all cases). In 2D cultures, the concentrations of BTZ of more than 8 nM almost completely abolished MM1S cell proliferation for either mono-culture or co-culture (Figure 4C and Figure S8). To compare, the lethal concentration of BTZ for RPMI-8226 cells was approximately 16 nM (Figure S9). Nevertheless, 2D cultures indicated higher toxicity of BTZ than 3D cultures irrespective if it was mono-culture or co-culture. A similar trend was observed for the estimated half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values (Table 1). These results could be possibly attributed to the differential effective doses (governed by diffusion) seen by the cells in the two configurations, as we previously demonstrated in similar bioprinted models[26, 57], again suggesting the potential improvement in physiological relevancy of our 3D-bioprinted constructs in modeling MM compared to 2D cultures.

Figure 4.

BTZ inhibits MM cell proliferation. (A) Live/dead staining of MM1S 3D mono-culture treated with different concentrations of BTZ. (B) Live/dead staining of MM1S and HS5 3D co-culture treated with different concentrations of BTZ. (C) Cell viability curves of MM1S mono- and co-cultures treated with different concentrations of BTZ. (D) Cell viability curves of RPMI-8226 mono- and co-cultures treated with different concentrations of BTZ. BTZ, bortezomib.

Table 1.

Estimated IC50 values of BTZ for MM cells in mono-cultures and co-cultures in 2D and 3D, corresponding to the plots shown in Figure 4C and D.

| BTZ IC50 (nM) | 3D mono-culture | 3D co-culture | 2D mono-culture | 2D co-culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM1S | 4.46 | 7.69 | 2.53 | 3.94 |

| RPMI-8226 | 6.93 | 10.58 | 4.94 | 6.39 |

In literature, Zhou et al. revealed that BTZ exhibited decent antiproliferative activities on the MM cell lines, i.e., RPMI-8226, U266, and KM3, with corresponding IC50 values calculated at 6.66, 4.31, and 10.1 nM, respectively.[58] The assay conducted by Zhang et al. indicated that BTZ treatment reduced cell viabilities in three MM cell lines, i.e., ARH77, U266, and SKO-007 (IC50 values of 2.83, 4.37, and 1.91 nM, respectively).[59] The data generated from the present study therefore showed good accordance with other findings.

BTZ directly inhibits proliferation as well as induces apoptosis of MM cells by various mechanisms, such as suppressing activation of the NF-κB pathway[60] and regulation of STAT3/Akt and ERK kinase.[61] In the present study, comparing mono-cultured MM cells or those co-cultured, the HS5 stromal cells secreting IL-6 might have promoted the biologically growth and survival of the MM cells.

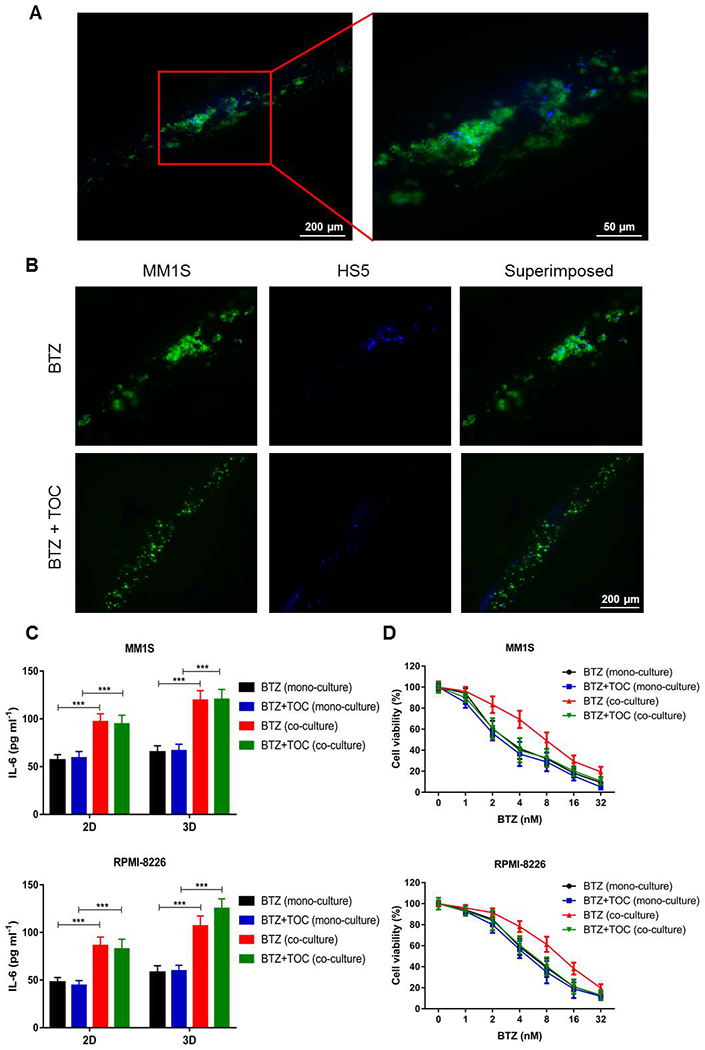

TOC Inhibits Cell Aggregation by Blocking IL-6R

As shown in Figure 5A, the cells in the co-culture group became highly aggregated after BTZ treatment likely due to that the presence of HS5 cells secreted IL-6, which promoted cellular adherence and aggregation of MM cells.[62, 63] Intriguingly, this phenomenon was effectively reversed with the administration of TOC, which could inhibit IL-6R bonding with IL-6 derived from HS5 cells, significantly reducing MM cell gathering (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

TOC inhibits MM cell aggregation and potentiates BTZ efficacy. (A) Under high magnification in the 3D co-culture group after BTZ treatment, the MM1S cells were observed to become more aggregated. (B) Fluorescence micrographs showing TOC inhibiting aggregation of MM1S cells in 3D co-culture after BTZ treatment. (C) ELISA quantification showing the levels of secreted IL-6 in mono- and co-cultures in both 2D and 3D. ***p<0.001. (D) Cell viability curves of mono- and co-cultures treated with different concentrations of BTZ in the absence or presence of TOC in 3D. BTZ, bortezomib; TOC, tocilizumab; IL-6, interleukin-6; IL-6R, IL-6-receptor.

Such observations were validated by the ELISA assay, which revealed that IL-6 levels released in the culture media were remarkably upregulated when the MM cells were co-cultured with HS5 cells in both 2D and 3D configurations (Figure 5C), again indicating the significant differences with mono-cultures. In the 3D models, we further assessed the proliferation of MM cells treated with the same gradient concentrations of BTZ as aforementioned. Based on the qualification of cell viability values, the use of TOC combined with BTZ significantly inhibited the growth of MM cells in the co-cultures, but there were no significant differences in the mono-cultures (Figure 5D). In other words, the administration of TOC although was not able to reduce the concentrations of IL-6 since these were determined by the existence of HS5 cells, it likely synergistically potentiated the effect of BTZ treatment through inhibiting IL-6R binding with IL-6 for the MM cells, and this synergistic effect was only clearly observable in our unique 3D system. The corresponding IC50 values identified for these different experimental groups are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Estimated IC50 values of BTZ for MM cells in mono-cultures and co-cultures in 3D, in the absence and presence of TOC, corresponding to the plots shown in Figure 5D. Note that the slight differences in IC50 values of BTZ in the absence of TOC in comparison with those in Table 1 were likely due to experimental errors.

| BTZ IC50 (nM) | BTZ mono-culture |

BTZ + TOC mono-culture |

BTZ co-culture |

BTZ + TOC co-culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM1S | 4.24 | 3.88 | 8.15 | 3.27 |

| RPMI-8226 | 6.68 | 6.23 | 11.54 | 5.04 |

As shown in Figure S10A, the CIs were further calculated for MM1S mono- and co-cultures treated with different concentrations of BTZ in the absence or presence of TOC in 3D. Only in the co-culture configuration, the concentrations of BTZ increased with CIs dropping to below 1 (BTZ: 4 nM, CI = 0.963; BTZ: 8 nM, CI = 0.826; BTZ: 16 nM, CI = 0.823; BTZ: 32 nM, CI = 0.801), which not only confirmed the synergistic effect of BTZ and TOC, but also suggested that the suppressing efficacy of TOC on the growth of MM1S cells could not work without the presence of HS5 co-culture. The RPMI-8226 cells showed the similar responses (Figure S10B).

The importance of IL-6 signaling in MM survival and growth is well-acknowledged.[64], where IL-6 binds to IL-6R forming the IL6–IL-6R complexes that further transduces signaling.[65] Thus, the blockage of IL-6 signaling possibly allows new therapeutic strategies for MM, as well as other possible types of diseases such as autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Mitsiades et al. had found that TOC not only decreased cellular adherence between MM cells and bone marrow stromal cells, but also suppressed the associated NF-κB induction of IL-6 secretion by the stromal cells.[66] Herein, we have validated, using our bioprinted model, the mechanism of TOC action and its potential use in MM therapy where elevated IL-6 signaling plays a key role.

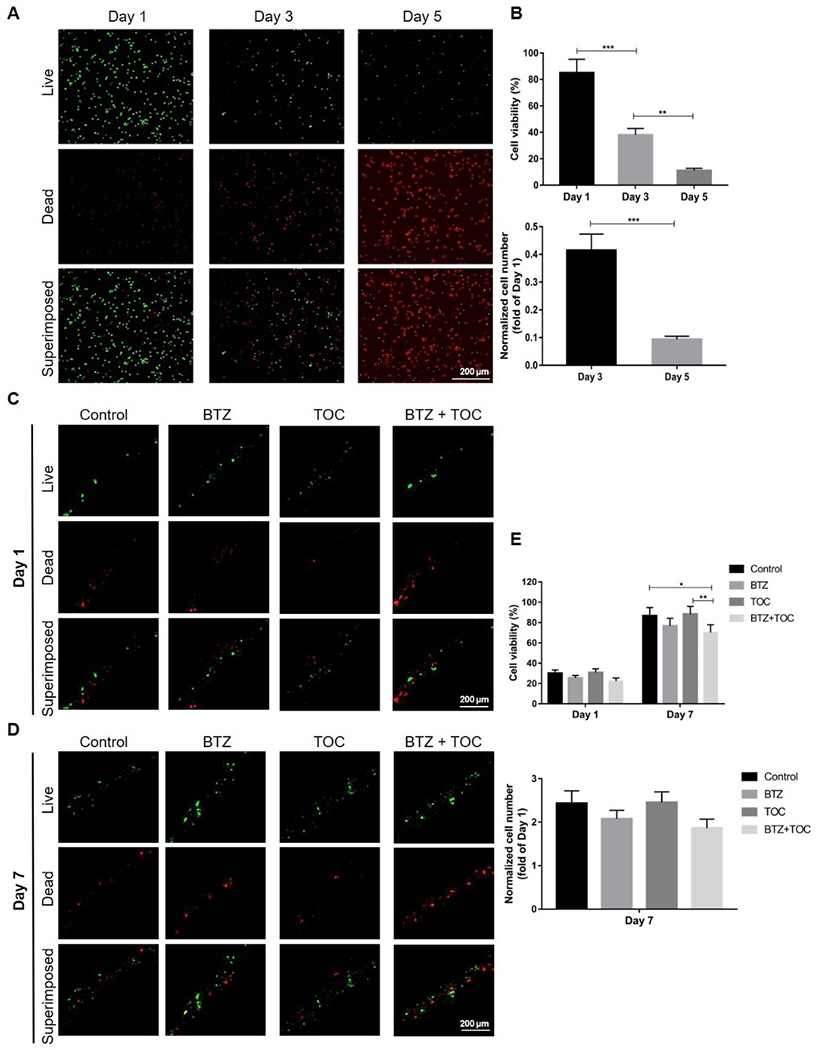

3D-Bioprinted Model Prolongs Survival of Patient-Derived MM Cells

As the patients’ MM cells cannot efficiently survive ex vivo,[67] there is a pressing need to devise reliable in vitro or ex vivo models to reproduce the native-like niches to enable more realistic mimicry of functions of these cells in a more realistic manner, for both disease modeling and drug screening applications. The efficacy of our 3D-bioprinted MM model in culturing MM cell lines have been proven, and whether the patients’ MM cells could survive and grow in a similar way still requires verification.

Consistent with literature reports[68] as well as our own experiences, Figure 6A and B show that patient-derived MM cells were almost all dead after only 5 days of culture in 2D on the surfaces of plastic wells. On the contrary, the same cells in our bioprinted 3D hydrogel-based, bone marrow-emulating model were still surviving after 7 days of culture (Figure 6C–D), with both viability and proliferation (normalized as fold of change to day 1) significantly higher than those at day 5 in 2D culture (Figure 6E vs. Figure 6B). Such inspiring results suggested that the 3D-bioprinted MM model could provide a microenvironment, perhaps endowed by the bone marrow-mimicking stiffness and the volumetric nature of the matrix, to effectively prolong the survival of MM cells ex vivo. As discussed, ex vivo culturing of patient-derived primary MM cells is still a key challenge due to the lack of suitable models. Primary MM cells could survive for more than 7 days cultured in our core-sheath configuration, while 2D cultures or other reported commercially available 3D systems did not seem to promote the proliferation of the primary samples.[69] Typically, stroma is required to recreate tumor-stroma interactions and accompanying signaling, with either MM cell lines or primary MM cells, which are lost in conventional 2D cultures.[18] The outcomes from our bioprinted model therefore indicated that a properly configured 3D microenvironment of the human bone marrow may represent an enabling platform for MM modeling, studies of tumor-stroma interactions, drug testing, and importantly, expansion of patient-derived primary MM cells.

Figure 6.

3D-bioprinted model prolongs patient-derived MM cell survival. (A) Live/dead staining and (B) viability/cell number quantification of patient-derived MM cells cultured in 2D at 1, 3, and 5 days of culture. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. (C, D) Live/dead staining of patient-derived MM cells cultured in 3D along with those treated with BTZ or/and TOC at 1 and 7 days of culture. (E) Viability and cell number quantification of patient-derived MM cells cultured in 3D under different conditions. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. BTZ, bortezomib; TOC, tocilizumab.

Four groups of drug testing were finally set as no intervention (control), BTZ, TOC, and BTZ/TOC combined. Similar to our results obtained with cell lines, the use of TOC in tandem with BTZ inhibited the primary MM cell growth more significantly than the administration of BTZ alone, and the synergistic effect of the two drugs on decreasing primary MM cell viability was more obvious than that of BTZ alone (Figure 6C–E).

Discussions

In general, the vast majority of our knowledge regarding tumor pathogenesis and drug vulnerability has been accumulated through the use of conventional 2D cell culture models, which oftentimes fail to predict disease progression due to their inability to simulate the natural tissue-specific microenvironments. The bone marrow-specific niche provides an effective refuge for MM cloning due to presence of close stromal-tumor cell interactions, which as a result, lead to survival advantage of these cells and their chemoresistance. A breakthrough in the 3D modeling of MM was achieved by Kirshner et al., who using a 3D culture system enabled expansion of MM cells and evaluation of antitumor therapies.[17] Another hydrogel-based model by Silva et al. seemed effective as it allowed the parallel testing of a range of drugs, and the results could become available in less than 5 days.[70] Compared with the few reported 3D models, let alone those of 2D in nature, our core-sheath model likely provides an improved emulation of the complex functional composition as well as architecture of the bone/bone marrow microenvironments, through the incorporation of mineral nanoparticles in the sheath containing a soft core, in the cortical bone-like tubular configuration.

Moreover, many of the existing in vitro models often cannot simulate the interactions between MM cells and the other key cell populations in a physiologically relevant manner.[71] An effective model therefore, should not only provide a microenvironment for 3D growth of cells, but further allow desired cell-cell interactions to permit cancer progression.[22] Our model is one of the first to enable co-culture of MM cells with stromal cells, thus successfully reflecting the cellular heterogeneity of this deadly tumor type. Co-culture of MM cells with the HS5 stromal cells in 2D conferred higher resistance to BTZ, in comparison to MM cells cultured alone. Of significance, resistance to BTZ was even more evident when MM cells were cultured with HS5 cells in the bioprinted core-sheath model, again underlying the potential role of 3D architecture itself in determining the impact of drugs. As such, our unique ability to enable expansion of patient-derived primary MM cells was demonstrated, which was not possible at all in simple 2D cultures.

Conclusions

In summary, we have reported a 3D-bioprinted MM model to preliminarily mimic human’s bone marrow niche and supply the pathologically relevant tumor microenvironment for MM cells. The coaxial nozzle was able to bioprint the complex hollow tubular constructs with the outer sheath layer containing the bone mineral while the inner core layer laden with MM cells or/and the stromal cells, in a single step. This 3D model promoted the growth and proliferation of the MM cells, and this effect became more pronounced when the MM cells were co-cultured with the HS5 stromal cells, because IL-6 secreted from the HS5 cells induced aggregation of the MM cells. Moreover, the patients’ MM cells could be prolonged for their survival ex vivo in our 3D-bioprinted model. Moreover, while BTZ played an important role in inhibiting MM cell proliferation, the combination of TOC with BTZ enhanced such inhibition primarily in the 3D system, likely by blocking the binding of IL-6 and IL-6R. To the best of our knowledge, our strategy is the first report of using coaxial bioprinting for high-content MM modeling in vitro, which also provides a unique angle regarding the potential utilization of dual BTZ/TOC treatment in MM chemotherapy in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The grant support for this investigation was provided by National Institutes of Health Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) grants P50100707 (DC and KCA), R01CA207237 (DC and KCA), and R01CA050947 (KCA), as well as R00CA201603 (YSZ), R01HL153857 (YSZ), and Brigham Research Institute (YSZ). This work was also supported in part by Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation, and the Riney Family Multiple Myeloma Initiative. KCA is an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor. We thank Xin Xie and Sanwei Liu for assistance with SEM imaging.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available in a separate file.

Conflict of Interest

YSZ sits on advisory board of Allevi, Inc., which however, did not support or interfere with the study. KCA is on advisory board of Celgene, Millenium-Takeda, Gilead, Janssen, and Bristol Myers Squibb, and is a Scientific Founder of Oncopep and C4 Therapeutics. DC is consultant to Stemline Therapeutic, Inc., Oncopeptide AB, and Equity owner in C4 Therapeutics. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Di Wu, Division of Engineering in Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Zongyi Wang, Division of Engineering in Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Jun Li, Division of Engineering in Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Yan Song, LeBow Institute for Myeloma Therapeutics and Jerome Lipper Myeloma Center, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Manuel Everardo Mondragon Perez, Division of Engineering in Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Zixuan Wang, Division of Engineering in Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Xia Cao, Division of Engineering in Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Changliang Cao, Division of Engineering in Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Sushila Maharjan, Division of Engineering in Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Kenneth C. Anderson, LeBow Institute for Myeloma Therapeutics and Jerome Lipper Myeloma Center, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA

Dharminder Chauhan, LeBow Institute for Myeloma Therapeutics and Jerome Lipper Myeloma Center, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Yu Shrike Zhang, Division of Engineering in Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

References

- [1].Cowan AJ, Allen C, Barac A, Basaleem H, Bensenor I, Curado MP, Foreman K, Gupta R, Harvey J, Hosgood HD, Jakovljevic M, Khader Y, Linn S, Lad D, Mantovani L, Nong VM, Mokdad A, Naghavi M, Postma M, Roshandel G, Shackelford K, Sisay M, Nguyen CT, Tran TT, Xuan BT, Ukwaja KN, Vollset SE, Weiderpass E, Libby EN, Fitzmaurice C, JAMA oncology 2018, 4, 1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rollig C, Knop S, Bornhauser M, Lancet 2015, 385, 2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kumar SK, Rajkumar V, Kyle RA, Van Duin M, Sonneveld P, Mateos MV, Gay F, Anderson KC, Nature reviews. Disease primers 2017, 3, 17046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K, Nooka AK, Masszi T, Beksac M, Spicka I, Hungria V, Munder M, Mateos MV, Mark TM, Qi M, Schecter J, Amin H, Qin X, Deraedt W, Ahmadi T, Spencer A, Sonneveld P, Investigators C, The New England journal of medicine 2016, 375, 754.27557302 [Google Scholar]

- [5].Anderson KC, Alsina M, Atanackovic D, Biermann JS, Chandler JC, Costello C, Djulbegovic B, Fung HC, Gasparetto C, Godby K, Hofmeister C, Holmberg L, Holstein S, Huff CA, Kassim A, Krishnan AY, Kumar SK, Liedtke M, Lunning M, Raje N, Reu FJ, Singhal S, Somlo G, Stockerl-Goldstein K, Treon SP, Weber D, Yahalom J, Shead DA, Kumar R, Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN 2016, 14, 389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dimopoulos MA, Richardson PG, Moreau P, Anderson KC, Nature reviews. Clinical oncology 2015, 12, 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Tonon G, Richardson PG, Anderson KC, Nature reviews. Cancer 2007, 7, 585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Meads MB, Gatenby RA, Dalton WS, Nature reviews. Cancer 2009, 9, 665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chen D, Frezza M, Schmitt S, Kanwar J, Dou QP, Current cancer drug targets 2011, 11, 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Raab MS, Podar K, Breitkreutz I, Richardson PG, Anderson KC, Lancet 2009, 374, 324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tan CRC, Abdul-Majeed S, Cael B, Barta SK, Clinical pharmacokinetics 2019, 58, 157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Buac D, Shen M, Schmitt S, Kona FR, Deshmukh R, Zhang Z, Neslund-Dudas C, Mitra B, Dou QP, Current pharmaceutical design 2013, 19, 4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mateos MV, San Miguel JF, Therapeutic advances in hematology 2012, 3, 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lane SW, Williams DA, Watt FM, Nature biotechnology 2014, 32, 795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mcmillin DW, Negri JM, Mitsiades CS, Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2013, 12, 217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Li H, Fan X, Houghton J, Journal of cellular biochemistry 2007, 101, 805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kirshner J, Thulien KJ, Martin LD, Debes Marun C, Reiman T, Belch AR, Pilarski LM, Blood 2008, 112, 2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Belloni D, Heltai S, Ponzoni M, Villa A, Vergani B, Pecciarini L, Marcatti M, Girlanda S, Tonon G, Ciceri F, Caligaris-Cappio F, Ferrarini M, Ferrero E, Haematologica 2018, 103, 707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Braham MV, Deshantri AK, Minnema MC, Oner FC, Schiffelers RM, Fens MH, Alblas J, International journal of nanomedicine 2018, 13, 8105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jeong HJ, Nam H, Jang J, Lee SJ, Bioengineering 2020, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhang YS, Duchamp M, Oklu R, Ellisen LW, Langer R, Khademhosseini A, ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2016, 2, 1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Li J, Parra-Cantu C, Wang Z, Zhang YS, Trends in Cancer 2020, 6, 745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Jia W, Gungor-Ozkerim PS, Zhang YS, Yue K, Zhu K, Liu W, Pi Q, Byambaa B, Dokmeci MR, Shin SR, Khademhosseini A, Biomaterials 2016, 106, 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Liu W, Zhong Z, Hu N, Zhou Y, Maggio L, Miri AK, Fragasso A, Jin X, Khademhosseini A, Zhang YS, Biofabrication 2018, 10, 024102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pi Q, Maharjan S, Yan X, Liu X, Singh B, Van Genderen AM, Robledo-Padilla F, Parra-Saldivar R, Hu N, Jia W, Xu C, Kang J, Hassan S, Cheng H, Hou X, Khademhosseini A, Zhang YS, Adv. Mater 2018, 30, 1706913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cao X, Ashfaq R, Cheng F, Maharjan S, Li J, Ying G, Hassan S, Xiao H, Yue K, Zhang YS, Adv. Funct. Mater 2019, 29, 1807173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shi Z, Wang Q, Jiang D, Journal of translational medicine 2019, 17, 211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gong J, Shuurmans C, Cao X, Van Genderen AM, Li W, Cheng F, He JJ, López A, Huerta V, Manríquez J, Li R, Li H, Delavaux C, Sebastian S, Wang H, Xie J, Yu M, Masereeuw R, Vermonden T, Zhang YS, Nature Communications 2020, 11, 1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dolati F, Yu Y, Zhang Y, De Jesus AM, Sander EA, Ozbolat IT, Nanotechnology 2014, 25, 145101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhang Y, Yu Y, Akkouch A, Dababneh A, Dolati F, Ozbolat IT, Biomaterials science 2015, 3, 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gao G, Kim H, Kim BS, Kong JS, Lee JY, Park BW, Chae S, Kim J, Ban K, Jang J, Park H-J, Cho D-W, Applied Physics Reviews 2019, 6, 041402. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Szczes A, Holysz L, Chibowski E, Advances in colloid and interface science 2017, 249, 321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Eskitoros-Togay SM, Bulbul YE, Dilsiz N, International journal of pharmaceutics 2020, 590, 119933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Venkatesan J, Kim SK, Journal of biomedical nanotechnology 2014, 10, 3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sakai A, Oda M, Itagaki M, Yoshida N, Arihiro K, Kimura A, International journal of hematology 2010, 92, 598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kurzrock R, Redman J, Cabanillas F, Jones D, Rothberg J, Talpaz M, Cancer research 1993, 53, 2118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chauhan D, Uchiyama H, Akbarali Y, Urashima M, Yamamoto K, Libermann TA, Anderson KC, Blood 1996, 87, 1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Scott LJ, Drugs 2017, 77, 1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tai YT, Mayes PA, Acharya C, Zhong MY, Cea M, Cagnetta A, Craigen J, Yates J, Gliddon L, Fieles W, Hoang B, Tunstead J, Christie AL, Kung AL, Richardson P, Munshi NC, Anderson KC, Blood 2014, 123, 3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Li J, Chen Y, Yin Y, Yao F, Yao K, Biomaterials 2007, 28, 781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zhang YS, Pi Q, Van Genderen AM, Journal of Visualized Experiments 2017, 126, e55957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Liu W, Heinrich MA, Zhou Y, Akpek A, Hu N, Liu X, Guan X, Zhong Z, Jin X, Khademhosseini A, Zhang YS, Adv. Healthcare Mater 2017, 6, 1601451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Maharjan S, Alva J, Cámara C, Rubio AG, Hernández D, Delavaux C, Correa E, Romo MD, Bonilla D, Santiago ML, Li W, Cheng F, Ying G, Zhang YS, Matter 2021, 4, 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chou T-C, Pharmacol. Rev 2006, 58, 621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lin J, Zhang W, Zhao JJ, Kwart AH, Yang C, Ma D, Ren X, Tai YT, Anderson KC, Handin RI, Munshi NC, Blood 2016, 128, 249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chen G, Dong C, Yang L, Lv Y, ACS applied materials & interfaces 2015, 7, 15790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Shakir M, Jolly R, Khan MS, Iram N, Khan HM, International journal of biological macromolecules 2015, 80, 282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Haroun AA, Migonney V, International journal of biological macromolecules 2010, 46, 310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Schwab A, Levato R, D’este M, Piluso S, Eglin D, Malda J, Chemical reviews 2020, 120, 11028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cao X, Ashfaq R, Cheng F, Maharjan S, Li J, Ying G, Hassan S, Xiao H, Yue K, Zhang YS, Advanced functional materials 2019, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Sydney Gladman A, Matsumoto EA, Nuzzo RG, Mahadevan L, Lewis JA, Nat. Mater 2016, 15, 413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kawano Y, Moschetta M, Manier S, Glavey S, Gorgun GT, Roccaro AM, Anderson KC, Ghobrial IM, Immunological reviews 2015, 263, 160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Roecklein BA, Torok-Storb B, Blood 1995, 85, 997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Reagan MR, Ghobrial IM, Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2012, 18, 342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ferrarini M, Steimberg N, Boniotti J, Berenzi A, Belloni D, Mazzoleni G, Ferrero E, Methods in molecular biology 2017, 1612, 177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kim HY, Moon JY, Ryu H, Choi YS, Song IC, Lee HJ, Yun HJ, Kim S, Jo DY, Blood research 2015, 50, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Massa S, Seo J, Arneri A, Bersini S, Cha B-H, Antona S, Enrico A, Gao Y, Hassan S, Cox JPA, Zhang YS, Dokmeci MR, Khademhosseini A, Shin S-R, Biomicrofluidics 2017, 11, 044109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Zhou Y, Liu X, Xue J, Liu L, Liang T, Li W, Yang X, Hou X, Fang H, J Med Chem 2020, 63, 4701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zhang H, Pang Y, Ma C, Li J, Wang H, Shao Z, Oncol Res 2018, 26, 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Poulaki V, Chauhan D, Fanourakis G, Gu X, Bailey C, Joseph M, Libermann TA, Treon SP, Munshi NC, Richardson PG, Hideshima T, Anderson KC, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2002, 99, 14374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Hayashi T, Akiyama M, Mitsiades N, Mitsiades C, Podar K, Munshi NC, Richardson PG, Anderson KC, Oncogene 2003, 22, 8386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Furukawa M, Ohkawara H, Ogawa K, Ikeda K, Ueda K, Shichishima-Nakamura A, Ito E, Imai JI, Yanagisawa Y, Honma R, Watanabe S, Waguri S, Ikezoe T, Takeishi Y, The Journal of biological chemistry 2017, 292, 4280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Piddock RE, Marlein CR, Abdul-Aziz A, Shafat MS, Auger MJ, Bowles KM, Rushworth SA, Journal of hematology & oncology 2018, 11, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Treon SP, Anderson KC, Current opinion in hematology 1998, 5, 42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Rose-John S, International journal of biological sciences 2012, 8, 1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Richardson PG, Poulaki V, Tai YT, Chauhan D, Fanourakis G, Gu X, Bailey C, Joseph M, Libermann TA, Schlossman R, Munshi NC, Hideshima T, Anderson KC, Blood 2003, 101, 2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Papadimitriou K, Kostopoulos IV, Tsopanidou A, Orologas-Stavrou N, Kastritis E, Tsitsilonis O, Dimopoulos MA, Terpos E, Cancers 2020, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Jakubikova J, Adamia S, Kost-Alimova M, Klippel S, Cervi D, Daley JF, Cholujova D, Kong SY, Leiba M, Blotta S, Ooi M, Delmore J, Laubach J, Richardson PG, Sedlak J, Anderson KC, Mitsiades CS, Blood 2011, 117, 4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].De La Puente P, Muz B, Gilson RC, Azab F, Luderer M, King J, Achilefu S, Vij R, Azab AK, Biomaterials 2015, 73, 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Silva A, Silva MC, Sudalagunta P, Distler A, Jacobson T, Collins A, Nguyen T, Song J, Chen DT, Chen L, Cubitt C, Baz R, Perez L, Rebatchouk D, Dalton W, Greene J, Gatenby R, Gillies R, Sontag E, Meads MB, Shain KH, Cancer research 2017, 77, 3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Weilbaecher KN, Guise TA, Mccauley LK, Nature reviews. Cancer 2011, 11, 411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.