Abstract

Parents are the important implementers on appropriate/inappropriate use of antibiotics, especially in the pediatric population. Limited studies have associated poor knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) among parents with antibiotics misuse. Therefore, this study was conducted to determine the parents’ KAP and factors associated with inappropriate use of antibiotics among Tanzanian children. A hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted in 14 regional referral hospitals (RRHs) in Tanzania between June and September 2020. KAP was estimated using a Likert scale, whereas KAP factors were determined using logistic regression models. A total of 2802 parents were enrolled in the study. The median age (interquartile range) of parents was 30.0 (25–36) years where 82.4% (n = 2305) were female parents. The majority of the parents had primary education, 56.1% (n = 1567). Of 2802 parents, only 10.9% (n = 298) had good knowledge about antibiotics, 16.4% (n = 455) had positive attitude whereas 82.0% (n = 2275) had poor practice on the appropriate use of antibiotics. Parents' education level, i.e., having a university degree (aOR: 3.27 95% CI 1.62–6.63, p = 0.001), good knowledge (aOR: 1.70, 95% CI 1.19–2.23, p = 0.003) and positive attitudes (aOR: 5.56, 95% CI 4.09–7.56, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with the appropriate use of antibiotics in children. Most parents had poor knowledge, negative attitude, and poor practice towards antibiotics use in children. Parents’ education level, employment status, knowledge on antibiotic use, and good attitude contributed to the appropriate use of antibiotics in children attending clinics at RRHs.

Subject terms: Immunology, Microbiology, Diseases, Health care, Medical research

Introduction

Antibiotic misuse contributed by either antibiotic abuse, overuse or sub-optimal use has potential serious effects on health including development of antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics resistance (AR) is an inherent nature of the bacteria as a means of survival1. The impacts of AR are immense and broad; for instance, AR can result into prolonged hospital stay, financial burden, morbidity and mortality2. In 2019 World Health Organization (WHO) report estimated that AR resulted in around 700,000 annual deaths worldwide3 and by 2030 AR is estimated to contribute 10 million deaths worldwide4. The situation in low and middle-income countries (LMCIs), including Tanzania, is expected to be worse due to poverty, poor health care system, inadequate water supply and sanitation, and high human-animal interaction, which facilitate the emergence and spread of resistant strains5.

Several measures, such as rational use of antibiotics, need to be implemented to mitigate resistant bacteria2. Sub-optimal exposure to antibiotics due to poor adherence, underdose, and wrong indications elicits selection pressure and the emergence of resistant strains6. In recognition of this global public health threat, surveillance and dedicated implementational research may enable timely prevention and control of this emerging problem7. The strategies have to consider a holistic approach taking into account the key stakeholders including policy makers, scientists, donors/funders and implementers such as healthcare providers and community, including parents/guardians8. At implementation levels, some of the strategies include AR stewardship programs that promote antibiotics' rational use, antibiotic use evaluation and monitoring in health facilities, healthcare providers' training, creating community awareness, and one health initiative9.

On the other hand, when a patient, especially a child (outpatient), exit the hospital settings, instructions from the attending physician on rational antibiotic use need to be implemented by his/her parents8. In this note, parents or guardians are proxy to appropriate/inappropriate use of antibiotics, especially in the pediatric population10. In several studies, antibiotics misuse has been associated with poor knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP)11–13. Parents have been reported to provide children with antibiotics for symptomatic treatment of common cold, cough, fever, or respiratory diseases14. Therefore, a study was conducted to determine the parents/guardians’ KAP and factors associated with inappropriate use of antibiotics among Tanzanian children.

Methods

Study design and population

A hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the level of KAP and factors associated with the inappropriate use of antibiotics in pediatric patients among parents at 14 regional referral hospitals (RRHs) in Tanzania Mainland; Temeke, Tumbi, Ruvuma, Lindi, Geita, Sekoutoure, Dodoma, Singida, Njombe, Sumbawanga, Iringa, Songwe and Arusha. These hospitals have beds capacity between 300 and 50015. This study was conducted between June and September 2020. Study areas were categorized into seven administrative zones of Tanzania mainland. Within each zone, two RRHs were selected to represent each zone. The selection of hospitals within each zone was based on community economic activities15 such as business, manufacturing, tourism, livestock keeping, farming and mining. Economic activities were associated with the inappropriate use of antibiotics in community settings16. Additionally, RRHs were chosen as study sites because, according to the national action plan on antimicrobial resistance8, RRHs are listed as one of the implementers of the plan. Tanzania RRHs offer a range of clinical services such as pediatrics, outpatient and inpatient, emergency services, diagnostic (laboratory, radiology and imaging), pharmaceutical supply, internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynecology17. The study population constituted of parents/guardians attending clinic at the respective RRHs.

Sample size and sampling techniques

The sample size of parents/guardians interviewed was calculated using the formula; n = Z2*P (1 − P)/d2. Where n was the sample size, p (47.7%) was prevalence from the study conducted among Tanzanian parents18, (1 − α) = 0.95, Z(1-α) = 1.96 for 95% confidence level, and the absolute error/precision (d) was assumed to be 0.022. A minimum sample size of 730 was required as previously described by Simon and Kazaura18.

Since the RRHs in Tanzania attend both primary and referred patients17, the consecutive sampling technique was used when enrolling parents or guardians so that both primary and referred patients were evenly selected. Each hospital contributed almost an equal number of participants.

Data collection

Development and validation of a questionnaire.

The questionnaire was developed after a comprehensive literature review of the studies highlighting the influence of KAP on the irrational use of antibiotics in pediatric patients19–22. Some of the questions were adopted23 while other questions were customized to suit parents (assuming that most of the parents were non-medical professionals). The questionnaire was prepared in English and translated to Kiswahili language for convenient and accurate data collection. Ten individuals with a firm command of both languages checked the accuracy and meaning of the translated content. The questionnaire was first validated and tested to answer the study's objectives by a random selection of 10 pediatric parents in a pilot study conducted in Dar es Salaam region between 1 and 5 June 2020.

Types of data collected

Data were collected using structured questionnaires. Each questionnaire consisted of five sections. Section A: collected data on socio-demographic information of the study participants (parents), which included age, gender, family type, number of children, education qualification, marital status, and residence, plus some socio-demographic information of the child such as age and sex. Section B: consisted of questions on knowledge about the use of antibiotics. Section C: comprised of questions on the influence of attitude on the use of antibiotics. Section D: consisted of questions assessing parental practice on the appropriate use of antibiotics. The grading used a Likert scale with choices from strongly disagree to strongly agree for knowledge and attitude, and always to never for practice. Section E consisted of questions on the parents’ sources of information about antibiotics (Additional file 1).

Data analysis

Data were collected using Open Data Kit (ODK software, USA) and then exported to Microsoft Excel Sheet (Redmond, WA). Data coding and analysis were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 25 (SPSS Software, Chicago Inc., USA). Categorical variables such as sex, education level and marital status were presented using frequencies and percentages. Means and standard deviations were used in summarizing normal distributed variable while medians and interquartile ranges were used when variables were not normal distributed. A particular question was categorized as correct/uncertain/not correct for knowledge during data presentation, whereas yes/uncertain/no for attitude and yes/no for practice. Yes, was for strongly agree and agree responses while no was for strongly disagree, disagree, and uncertain for practice and attitude responses.

The overall knowledge, attitude and practice were estimated as previously described elsewhere13,24. Briefly, to every individual question, the correct response was given a score of 1, while incorrect response and uncertainty were given 0. Strongly agree and agree were merged as agree while strongly disagree and disagree merged as disagree. Depending on the score, knowledge was termed as poor, moderate, and good, while attitude was categorized as negative, uncertain, and positive. Poor/negative was given a score of 0–49%, moderate/uncertain 50–79% and good/positive 80–100%. Always and often were merged as agree, whereas sometimes/seldom/never were merged as disagree. For this research, questions on practice were used to measure appropriate/inappropriate use of antibiotics. The percentage score for practice was inappropriate (misuse) if the score was 0–79% and appropriate (good use) if the score was 80–100%.

The score was determined as the percentage of correct responses to the total asked questions in each category (K/A/P). An ordinal logistic regression model was used to determine factors associated with positive attitude and knowledge. The primary outcome of this study was the inappropriate use of antibiotics whereby, the binary logistic regression model was used to determine factors associated with misuse of antibiotics in children. The measure of associations was the crude odds ratio (cOR) for univariate analysis and adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for multivariate analysis. Multivariate analysis was done to all factors that showed statistics p < 0.2 in the univariate analysis. The p-value of less than 0.05 at the confidence interval of 95% (95%CI) indicated the statistical significance.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval to conduct this study was obtained from Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences Ethical Review Board (Reference number: MUHAS-REC-3-2020-109). Permission to conduct the study at the pediatric departments were requested from the Medical Officer In-charges. Written informed consents after explaining the purpose of the study were requested from parents before enrollment. Addition, this study was conducted with accordance to the law and regulation of Tanzania.

Results

Participants’ sociodemographic characteristics

A total of 2802 parents and 2793 children attending clinics in the selected RRHs in Tanzania were included in this study. The median age (interquartile range) of parents was 30.0 (25–36) years, while the median age for their children attending the clinic was 2.0 (1–4) years. About half of the parents (50.6%) were in the age between 25 and 35 years (n = 1408) whereas children with age less than 5 years were the majority 88.1% (n = 2460), and 82.4% (n = 2305) were female parents. About 81% (2259) were married whilst 56.1% (n = 1567) had attained primary education, 63.8% (n = 1782) lived in a nuclear family type and 45.7% (n = 1276) of the parents had more than 2 children. Almost half of the parents 46.8% (n = 1307) were self-employed and 51.2% (n = 1428) had low income. Most of the children were males 53.3% (n = 1484) whereas 68.3% (n = 1823) of their parents lived in urban areas (Table 1).

Table 1.

Parents’ and children’s sociodemographic information.

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent’s age (years) | < 25 | 621 | 22.3 |

| 25–35 | 1408 | 50.6 | |

| 36–45 | 612 | 22.0 | |

| > 45 | 142 | 5.1 | |

| Parent’s sex | Male | 493 | 17.6 |

| Female | 2305 | 82.4 | |

| Marital status | Married | 2259 | 81.0 |

| Not married | 530 | 19.0 | |

| Parent’s education level | Illiterate | 271 | 9.7 |

| Literate | 418 | 15.0 | |

| Primary | 1567 | 56.1 | |

| Secondary | 213 | 7.6 | |

| Certificate | 100 | 3.6 | |

| Diploma | 122 | 4.4 | |

| Graduate | 101 | 3.6 | |

| Postgraduate | 3 | 0.1 | |

| Employment status | Employed | 576 | 20.6 |

| Self employed | 1307 | 46.8 | |

| Not employed | 909 | 32.6 | |

| Family type | Nuclear family | 1782 | 63.8 |

| Single parent family | 511 | 18.3 | |

| Extended family | 499 | 17.9 | |

| Number of children | 1 | 723 | 25.9 |

| 2 | 794 | 28.4 | |

| ≥ 3 | 1276 | 45.7 | |

| Child’s sex | Male | 1484 | 53.3 |

| Female | 1300 | 46.7 | |

| Child’s age (years) | < 5 | 2460 | 88.1 |

| 5–9 | 276 | 9.9 | |

| ≥ 10 | 57 | 2.0 | |

| Family monthly incomea ($) | Low | 1428 | 51.2 |

| Middle | 1133 | 40.6 | |

| High | 228 | 8.2 | |

| Place of residence | Urban | 1823 | 68.3 |

| Rural | 847 | 31.7 |

aThe classification of family income used a world bank definition of poverty of population living on less than $1.25 per day.

Responses from parents on the individual questions

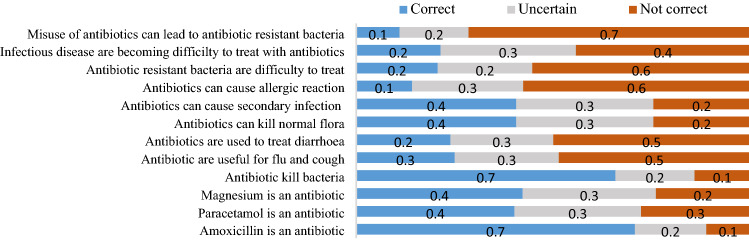

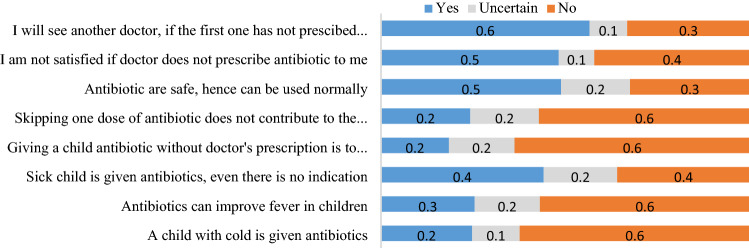

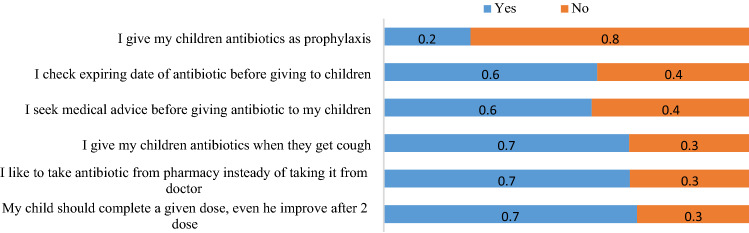

Figures 1, 2 and 3 highlight the responses from parents on knowledge, attitude and practice against the appropriate use of antibiotics for children.

Figure 1.

Knowledge on rational use of antibiotics in children among parents attending clinic at RRHs in Tanzania. In assessing the knowledge, 2726 participants responded to different questions whereby 42.3% and 40.1% knew that magnesium and paracetamol are not antibiotics, respectively. Few participants, 11% had the knowledge that misuse of antibiotics can lead to AR while 21.4% had adequate knowledge on AR.

Figure 2.

Parents’ attitude toward rational use of antibiotics among children. Among 2772 parents assessed for their attitude towards appropriate antibiotic use in children, 56.0% had a negative attitude to non-antibiotics prescriptions and were ready to seek another doctor who would prescribe an antibiotic for their children. The majority (63.8%) were ready to give their children antibiotics without a doctor’s prescription. Additionally, 44.1% could provide antibiotics for their children, even without an indication.

Figure 3.

Parental practice on the appropriate use of antibiotics in children. Of 2775 responded to the practice questions, 67.0% like to take medicine from pharmacies than doctors. Some parents (30.3%) were ready to stop giving antibiotics to their children when there were improvements. About 33% of parents gave antibiotics to their children when they had a cough. Regarding the expiry date, 41.7% reported that they don’t check the expiring dates of antibiotics before giving to their children.

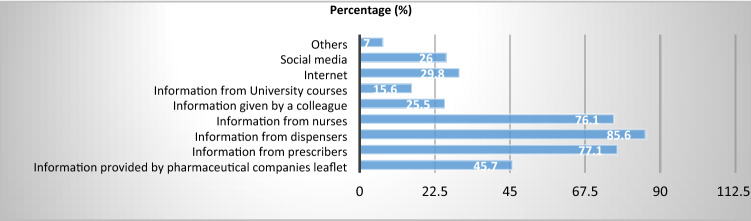

Parents’ sources of information about antibiotics

Majority of the parents obtained their information from dispensers 85.6% (n = 2385) followed by prescriber 77.1% (n = 2148) then nurses 76.1% (n = 2131). Few parents obtained the information about antibiotics from social media 26.0% (n = 724), colleague 25.5% (n = 706) and university courses 15.6% (n = 434) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Parents’ source(s) of information about antibiotics.

| Source | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Information provided by pharmaceutical companies leaflet | 1280 | 45.7 |

| Information from prescribers | 2148 | 77.1 |

| Information from dispensers | 2385 | 85.6 |

| Information from nurses | 2131 | 76.1 |

| Information given by a colleague | 706 | 25.5 |

| Information from University courses | 434 | 15.6 |

| Internet | 831 | 29.8 |

| Social media | 724 | 26.0 |

| Others | 196 | 7.0 |

A parent was able to choose more than one source. Hence, the total percentage is more than 100%.

Source(s) of information about antibiotics (Fig. 4)

Figure 4.

Parents’ source(s) of information about antibiotics. Of 2802 respondents, majority of the parents obtained their information from dispensers 85.6% followed by prescriber 77.1%) then nurses 76.1%. Few parents obtained the information about antibiotics from social media 26.0%, colleague 25.5% and university courses 15.6%.

Overall parents’ KAP on rational use of antibiotics in children

Out of 2802 parents who were assessed on the KAP, only 10.9% (n = 298) had good knowledge, 16.4% (n = 455) had a positive attitude and 82.0% (n = 2275), had poor practice on rational antibiotics use in children (Table 3).

Table 3.

Overall parents’ KAP on rational use of antibiotics in children.

| Variable | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Poor | 1272 | 46.7 |

| Moderate | 1156 | 42.4 | |

| Good | 298 | 10.9 | |

| Attitude | Negative | 1485 | 53.6 |

| Uncertain | 832 | 30.0 | |

| Positive | 455 | 16.4 | |

| Practices | Poor | 2275 | 82.0 |

| Good | 500 | 18.0 |

Factors associated with knowledge of antibiotics use in children

Both univariate and multivariate analysis found an association between parents’ age and knowledge about antibiotics use in children. Parents with age between 36 and 45 years had 41% high odds (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 1.41, 95% CI 1.05–1.90, p = 0.021) of good knowledge about antibiotics use compared to those < 25 years. Employed parents had about 3 times more chance of having good knowledge than unemployed parents (aOR: 2.66, 95% CI 2.06–3.43, p < 0.001). Parents with a degree had good knowledge about antibiotics use in children compared to illiterate parents (aOR: 3.22, 95% CI 1.96–5.26, p < 0.001). Parents living in a nuclear family (father, mother, children) had poor knowledge when compared to those living in the extended family (aOR: 0.71, 95% CI 0.58–0.88, p = 0.002) while parents living in urban areas had 64% more chance to have good knowledge as compared to those from rural areas (aOR: 1.64, 95% CI 1.37–1.96, p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with parents’ good knowledge about antibiotics use in children.

| Variable | Categories | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cOR | 95% CI | P-value | aOR | 95% CI | P-value | ||

| Parents’ age (years) | > 45 | 1.41 | 0.99–2.01 | 0.054 | 1.55 | 1.02–2.36 | 0.041 |

| 36–45 | 1.60 | 1.28–1.99 | < 0.001 | 1.41 | 1.05–1.90 | 0.021 | |

| 25–35 | 1.47 | 1.22–1.77 | < 0.001 | 1.13 | 0.90–1.43 | 0.287 | |

| < 25 | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Number of children | ≥ 3 | 1.12 | 0.94–1.34 | 0.197 | 0.80 | 0.62–1.03 | 0.079 |

| 2 | 1.28 | 1.05–1.55 | 0.015 | 1.00 | 0.79–1.26 | 0.991 | |

| 1 | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Parents’ sex | Female | 0.96 | 0.80–1.16 | 0.698 | |||

| Male | Ref | ||||||

| Marital status | Married | 1.46 | 1.21–1.76 | < 0.001 | 1.15 | 0.86–1.54 | 0.351 |

| Not married | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Occupation | Employed | 3.81 | 3.09–4.69 | < 0.001 | 2.66 | 2.06–3.43 | < 0.001 |

| Self-employed | 1.33 | 1.13–1.57 | 0.001 | 1.21 | 1.002–1.45 | 0.048 | |

| Not employed | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Education level | Degree/Masters | 7.58 | 4.83–11.91 | < 0.001 | 3.22 | 1.96–5.26 | < 0.001 |

| Diploma | 3.90 | 2.56–5.93 | < 0.001 | 1.40 | 0.87–2.24 | 0.167 | |

| Certificate | 6.42 | 4.10–10.07 | < 0.001 | 2.87 | 1.76–4.66 | < 0.001 | |

| Advanced secondary | 1.20 | 0.84–1.73 | 0.317 | 0.68 | 0.46–1.02 | 0.065 | |

| Primary/secondary | 2.01 | 1.55–2.62 | < 0.001 | 1.41 | 1.06–1.88 | 0.018 | |

| Literate | 1.25 | 0.92–1.70 | 0.159 | 0.85 | 0.61–1.19 | 0.350 | |

| Illiterate | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Family type | Nuclear family | 0.86 | 0.71–1.04 | 0.133 | 0.71 | 0.58–0.88 | 0.002 |

| Single parent family | 0.58 | 0.46–0.74 | < 0.001 | 0.61 | 0.44–0.84 | 0.003 | |

| Extended family | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Place of residence | Urban | 2.06 | 1.75–2.45 | < 0.001 | 1.64 | 1.37–1.96 | < 0.001 |

| Rural | Ref | Ref | |||||

cOR crude odds ratio, aOR adjusted odds ratio, 95%CI 95% confidence interval, Ref reference category.

Factors associated with attitude on appropriate use of antibiotics in children

Univariate analysis found an association between positive attitude and parents’ age whereby parents aging between 25 and 45 years had 35% more chance to have a positive attitude as compared to those with age below 25 years (cOR: 1.35, 95% 95% CI 1.08–1.68, p = 0.07). However, there was no association on multivariate analysis (aOR: 1.16. 95% CI 0.91–1.49, p = 0.234). Female parents had negative attitude on antibiotics use in children compared to male parents (aOR: 0.76, 95%: 0.62–0.94, p = 0.01). Degree holder parents had five times more chance to have a positive attitude towards antibiotics use in children than illiterate parents (aOR: 5.3, 95% CI 3.24–8.65, p < 0.001). Patients living in urban areas were 2 times likely to have a positive attitude as compared to those from rural areas (aOR: 2.07, 95% CI 1.72–2.49, p < 0.001) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with parents’ positive attitude on appropriate use of antibiotic in children.

| Variable | Categories | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cOR | 95% CI | P-value | aOR | 95% CI | P-value | ||

| Parents’ age (years) | > 45 | 1.08 | 0.76–1.54 | 0.677 | 1.19 | 0.79–1.77 | 0.405 |

| 36–45 | 1.35 | 1.08–1.68 | 0.007 | 1.16 | 0.91–1.49 | 0.234 | |

| 25–35 | 1.33 | 1.10–1.60 | 0.003 | 1.10 | 0.90–1.35 | 0.357 | |

| < 25 | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Number of children | ≥ 3 | 1.07 | 0.90–1.28 | 0.447 | |||

| 2 | 1.20 | 0.99–1.46 | 0.063 | ||||

| 1 | Ref | ||||||

| Parents’ sex | Female | 0.81 | 0.68–0.98 | 0.029 | 0.76 | 0.62–0.94 | 0.010 |

| Male | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Marital status | Married | 1.28 | 1.06–1.54 | 0.010 | 1.03 | 0.77–1.38 | 0.844 |

| Not married | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Occupation | Employed | 1.93 | 1.58–2.36 | < 0.001 | 1.20 | 0.94–1.55 | 0.148 |

| Self-employed | 1.19 | 1.01–1.40 | 0.040 | 0.96 | 0.80–1.15 | 0.634 | |

| Not employed | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Education level | Degree/masters | 8.79 | 5.60–13.82 | < 0.001 | 5.30 | 3.24–8.65 | < 0.001 |

| Diploma | 2.54 | 1.66–3.89 | < 0.001 | 1.38 | 0.85–2.23 | 0.187 | |

| Certificate | 4.92 | 3.15–7.70 | < 0.001 | 2.89 | 1.77–4.70 | < 0.001 | |

| Advanced secondary | 1.16 | 0.79–1.71 | 0.441 | 0.76 | 0.49–1.17 | 0.214 | |

| Primary/secondary | 2.73 | 2.06–3.60 | < 0.001 | 1.92 | 1.42–2.60 | < 0.001 | |

| Literate | 1.32 | 0.95–1.84 | 0.097 | 0.92 | 0.65–1.32 | 0.661 | |

| Illiterate | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Family type | Nuclear family | 1.22 | 1.004–1.48 | 0.046 | 1.08 | 0.87–1.33 | 0.493 |

| Single parent family | 0.81 | 0.64–1.04 | 0.093 | 0.81 | 0.59–1.13 | 0.224 | |

| Extended family | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Residence | Urban | 2.37 | 2.00–2.81 | < 0.001 | 2.07 | 1.72–2.49 | < 0.001 |

| Rural | Ref | Ref | |||||

cOR crude odds ratio, aOR adjusted odds ratio, 95%CI 95% confidence interval, Ref reference category.

Influence of sociodemographic, knowledge and attitude on the appropriate use of antibiotics in children

Factors for appropriate use of antibiotics in children were assessed. The univariate analysis found that employed parents were 3 times more likely to have good practice as compared to un-employed parents (cOR: 2.79, 95% CI 2.13–3.64, p < 0.001), but the multivariate analysis found no association (aOR: 1.18, 95% CI 0.78–1 78, p = 0.431). Parents' education significantly influenced the appropriate use of antibiotics in children, i.e., patients with at least a bachelor's degree had 3 times more chance of having good practice than non-educated parents (aOR: 3.27 95% CI 1.62–6.63, p = 0.001). Parents living in a nuclear family (father, mother and children) had 35% more chance of having a good practice compared to those from an extended family (father, mother, children and relatives) (cOR: 1.35, 95% CI 1.03–1.77, p = 0.032) while being an urban resident had 76% more chance of giving antibiotics to a child correctly (cOR: 1.76, 95% CI 1.39–2.23, p < 0.001). Regarding the knowledge and attitude toward the good practice of antibiotics use in children. Parents with a good knowledge had 70% more chance of having good practice (aOR: 1.70, 95% CI 1.19–2.23, p = 0.003); similarly, those with positive attitudes had about 6 times more chance (aOR: 5.56, 95% CI 4.09–7.56, p < 0.001) of practicing appropriately (Table 6).

Table 6.

Factors associated with appropriate use of antibiotics in children (good practice).

| Variable | Categories | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cOR | 95% CI | P-value | aOR | 95% CI | P-value | ||

| Parents’ age (years) | > 45 | 0.58 | 0.32–1.06 | 0.074 | 0.82 | 0.40–1.65 | 0.573 |

| 36–45 | 1.04 | 0.77–1.42 | 0.788 | 0.99 | 0.64–1.55 | 0.994 | |

| 25–35 | 1.37 | 1.07–1.77 | 0.014 | 1.05 | 0.76–1.46 | 0.769 | |

| < 25 | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Children’s (years) | ≥ 10 | 0.75 | 0.35–1.60 | 0.459 | |||

| 5–9 | 0.80 | 0.56–1.12 | 0.193 | ||||

| < 5 | Ref | ||||||

| Number of children | ≥ 3 | 0.70 | 0.55–0.88 | 0.003 | 0.66 | 0.46–0.94 | 0.023 |

| 2 | 0.94 | 0.73–1.21 | 0.627 | 0.82 | 0.59–1.12 | 0.212 | |

| 1 | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Parents’ sex | Female | 1.38 | 1.05–1.82 | 0.020 | 1.51 | 1.08–2.09 | 0.015 |

| Male | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Marital status | Married | 1.13 | 0.87–1.45 | 0.363 | |||

| Not married | Ref | ||||||

| Occupation | Employed | 2.79 | 2.13–3.64 | < 0.001 | 1.18 | 0.78–1.78 | 0.431 |

| Self-employed | 1.44 | 1.13–1.84 | 0.003 | 1.16 | 0.85–1.57 | 0.348 | |

| Not employed | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Monthly incomea ($) | High | 4.52 | 3.29–6.20 | < 0.001 | 2.02 | 1.29–3.16 | 0.002 |

| Middle | 2.35 | 1.90–2.92 | < 0.001 | 1.53 | 1.14–2.04 | 0.004 | |

| Low | Ref | ||||||

| Education level | Degree/Masters | 11.13 | 6.16–20.12 | < 0.001 | 3.27 | 1.62–6.63 | 0.001 |

| Diploma | 4.94 | 2.74–8.93 | < 0.001 | 2.10 | 1.05–4.22 | 0.036 | |

| Certificate | 5.06 | 2.73–9.39 | < 0.001 | 1.67 | 0.83–3.37 | 0.151 | |

| Advanced secondary | 2.17 | 1.21–3.87 | 0.009 | 1.10 | 0.56–2.14 | 0.791 | |

| Primary/secondary | 2.83 | 1.78–4.49 | < 0.001 | 1.46 | 0.88–2.41 | 0.145 | |

| Literate | 0.95 | 0.53–1.69 | 0.864 | 0.64 | 0.34–1.20 | 0.162 | |

| Illiterate | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Family type | Nuclear family | 1.35 | 1.03–1.77 | 0.032 | 1.19 | 0.86–1.65 | 0.296 |

| Single parent family | 1.06 | 0.76–1.50 | 0.729 | 1.03 | 0.67–1.58 | 0.905 | |

| Extended family | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Place of residence | Urban | 1.76 | 1.39–2.23 | < 0.001 | 0.82 | 0.62–1.09 | 0.170 |

| Rural | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Knowledge | Good | 4.44 | 3.31–5.95 | < 0.001 | 1.70 | 1.19–2.43 | 0.003 |

| Moderate | 1.85 | 1.47–2.31 | < 0.001 | 1.23 | 0.95–1.59 | 0.112 | |

| Poor | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Attitude | Positive | 7.51 | 5.78–9.77 | < 0.001 | 5.56 | 4.09–7.56 | < 0.001 |

| Uncertain | 3.28 | 2.57–4.19 | < 0.001 | 2.80 | 2.12–3.70 | < 0.001 | |

| Negative | Ref | Ref | |||||

aThe classification of family income used a world bank definition of poverty of population living on less than $1.25 per day.

Discussion

Due to many infectious diseases in developing countries like Tanzania, antibiotics use in children is widespread. This study surveyed 2802 parents KAP towards antibiotic use in children. To our knowledge, this is the first national-wide study to assess parents' KAP in Tanzania regarding the appropriate use of antibiotics in children. The evidence-based data provided from this study can be used to properly design the national interventional programs to improve children's general use of antibiotics.

This study explored different knowledge domains related to the identification of antibiotics, antibiotics' role, side effects of antibiotics, and antibiotic resistance. On average, the study found that only 10% of the parents had good knowledge of antibiotics. The reported proportion is extremely low compared to the recent findings (62.7%) reported in an urban area in Moshi, Northern Tanzania25. The difference observed is not surprising since the study conducted in Moshi consisted of a small sample size of participants residing in an urban area, with only 1.7% of participants not having formal education. In knowledge specific questions, the majority (65.9%) of the parents knew that antibiotics are used for bacterial infection. However, most of them were either uncertain or did not know that viruses could cause some types of upper respiratory infections and diarrhea in children. Therefore, in this case, antibiotics are not sufficient. The proportion reported in this study was higher than what was previously reported in India. Only 28% knew that the antibiotics are used for bacterial infections; the rest were confused about using antibiotics for bacteria or viruses26.

One of the critical problems of inappropriate use of antibiotics is the development of antibiotic resistance. Regarding parents' knowledge of antibiotic resistance issues in this study, only 11% of the patients knew that misuse of antibiotics could lead to antibiotic-resistant bacteria. About 20.7% of the parents knew that antibiotic-resistant bacteria are difficult to treat. The observed proportion is lower than what was reported in studies conducted in relatively more developed countries such as; in Greece 88%, Cyprus 90%, Israel 78% and Japan 43% of parents were aware that antibiotic misuse might cause antibiotic resistance27–30. The correct description of antibiotics was also assessed in this study, whereby 65.9% of the parents could recognize amoxicillin as an antibiotic. More than 50% of the parents didn't know or were uncertain that paracetamol and magnesium trisilicate are not antibiotics suggesting poor parents' knowledge of antibiotics identification. This observation is similar to what was previously reported in Moshi urban, Tanzania, and rural China, whereby some of the study participants could not correctly tell ampicillin is an antibiotic25,31.

Several factors associated with good parental knowledge about antibiotics use in children have been identified in this study. One is formal education, which was strongly associated with good knowledge about antibiotic use in children. The findings correlate with a previous study conducted in India and a review report. Out of 10 studies that examined the association between education and knowledge of antibiotic use, nine found a significant association14,26. This study also found that parents with older age had good knowledge about antibiotics use in children than the younger parents. Similar findings have been reported elsewhere28,32,33. Parents’ occupation was strongly associated with good knowledge of antibiotics use in children, whereby employed parents were two times more likely to have good knowledge about antibiotic use in children than non-employed parents. However, a previous study conducted in a much smaller area in Moshi urban, Tanzania, indicated that occupation does not affect adults' knowledge of antibiotic use25. The discrepancy observed here could be because the previous study involved people in the urban area only.

Regarding parents' sources of knowledge about antibiotic use in children, most parents reported obtaining their information from dispensers (85.6%) and prescribers (77.1%). These findings suggest that most people mainly get knowledge once they visit a health facility, especially when they have health problems; thus, most people in the community are left without information. The use of other means of conveying knowledge like TV, radio and the internet need to be considered when planning intervention programs.

Parents attitude towards antibiotics use has significant implications for the irrational use of antibiotics, leading to the development of antibiotic resistance in children34. More than half (56%) had a negative attitude to a non-antibiotic's prescription in assessing parents' attitudes. They were ready to seek another doctor who would prescribe an antibiotic for their children. The proportion of parents demanding such inappropriate prescription for antibiotics reported in this study is almost twice as high as that reported in the previous study35. Parental pressure and expectation have instigated pediatricians to prescribe antibiotics more often than required to satisfy their clients29,36. It is thought that most of the antibiotic prescriptions in pediatrics are dispensed for the treatment of virus-related infections37.

Other parents (63.8%) were ready to give their children antibiotics without a doctor's prescription and 67% preferred to obtain their antibiotics at the community pharmacies. In most countries, including Tanzania, the community can access antibiotics through community pharmacies. The ease of obtaining antibiotics at the pharmacy was reported in a previous study in Moshi, Tanzania using a simulated client's approach whereby out of 82 pharmacies which were visited, 92.3% of retailers dispensed antibiotics without prescriptions37. Therefore, healthcare providers' willingness to dispense antibiotics without prescription has made it easy for the community to obtain the medication, increasing irrational antibiotic use. This observation highlights the pharmacists' vital role in educating the community/parents about the safe and effective use of antibiotics.

Additionally, 44.1% could provide antibiotics for their children, even without an indication, whereby more than 50% of all parents agreed they would give antibiotics for treatment of fever or cold or cough. Similarly, previous KAP studies in Malaysia and Palestine also reported that most parents believed that antibiotics were helpful in the treatment of fever38,39. The incorrect use of antibiotics has also been documented elsewhere, whereby antibiotics have been used in self-limiting infections, especially upper respiratory tract illnesses, which do not require antibiotic treatment25,35.

Good attitudes and acceptable practices on antibiotics use would result in antibiotics' rational use and reduce antibiotic resistance. This study demonstrates that parents with good knowledge had 70% more chance of having a good practice; similarly, those with positive attitudes had 6 times more chance of practicing appropriately.

Good knowledge and positive attitude have also affected the parents' practice on antibiotics use in other studies25,35,40. Besides knowledge and parents' attitude, other factors affecting good practice on antibiotics use were parents' education level. Parents with at least a bachelor's degree had 3 times more chances of having good practice than non-educated parents. The effect of education in the knowledge, attitude and the ultimate practice on antibiotics use has been observed in previous studies in developing and developed countries25,41. Living in a nuclear family was also associated with a 35% more chance of having a good practice than an extended family. The reason for this is not apparent, but we speculate that having a large number of people in a home might make it difficult for the parent to make sure the child has to take the prescribed dose of the antibiotic. It may also influence the parent to get the medicine from the nearest pharmacy without taking the child to the hospital.

This study was conducted among parents found at clinics in the selected RRHs in Tanzania. The type of hospitals may influence the responses from the parents. RRHs have adequate specialists and facilities such as laboratories and well-equipped pharmacies which could contribute to the reduction of antibiotics misuse unlike the health centers and dispensaries where sometimes the nurse attendant can prescribe and dispense medications without proper indication and adequate counselling to parents/guardians on rational use of antibiotics. RRHs are currently implementing national action plan on antimicrobial resistance8. Additionally, to minimize professional bias, this study only assessed out-patients. The reason to only include outpatients’ is because in-patients drug dispensing and utilization is done under the supervision of nurses. Enrollment of an almost equal number of participants at each study site and data analysis not accounting for the variations in the hospital bed capacity existing among the selected hospitals are among the limitations to this study. Lastly, the conclusion from this study is limited to parents of children attending clinics at RRHs.

In conclusion, most parents had poor knowledge, negative attitude, and poor practice (KAP) towards antibiotics use in children. Factors such as education level, employment status, knowledge and attitude were significantly associated with the appropriate use of antibiotics among parents of children attending clinics at RRHs. Education on appropriate use of antibiotics especially in children should be sustainably provided through radio, tv, magazine and. Community based study on antibiotics use in children from their parents is warranted.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) acknowledges the support provided by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Tanzania, for the conceptualization and setting grounds for this work. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust [grant number: 216341/Z/19/Z] through UNICEF. We acknowledge Tanzania Pharmacy Council for their participation in conceptualization of the study and managing the disbursements of funds from UNICEF to MUHAS account. We recognize the cooperation from the Medical Officers in charge in referral regional hospitals and heads of the pediatric departments and pharmaceutical services. We would like to extend our gratitude to all the respondents from all hospitals who played a great role in making the data collection process possible. Lastly, we would like to thank all those who participated in the design of the study, data collection, data analysis and report writing.

Abbreviations

- aOR

Adjusted odds ratio

- AR

Antibiotics resistance

- cOR

Crude odds ratio

- KAP

Knowledge, attitude, practice

- MUHAS

Muhimbili university of health and allied sciences

- RRHs

Regional referral hospitals

- UNICEF

United Nations Children’s Fund

Author contributions

G.M.B., participated in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation and manuscript drafting. L.N. and U.K. in participated in study design, data collection, analysis and manuscript revision. WPM, MK, participated in study design, data collection and analysis. B.A.M., D.L.M., D.T.M., H.J.M. and F.F.F., participated in study design and data collection. R.F.M. and A.I.M. participated in data analysis, interpretation and drafting the manuscript. P.P.K. participated in data analysis and interpretation. P.N., G.S. and N.S. participated in revising the manuscript. A.N. participated in conceptualization, data collection and revising the manuscript. B.J.N. and H.P.N. participated in data analysis and revising the manuscript. R.S. participated in revising the manuscript. E.N. and R.S. participated in conceptualization, study design and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ritah F. Mutagonda, Lilian Nkinda, Upendo Kibwana and George M. Bwire.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-08895-6.

References

- 1.Kirchhelle C. Pharming animals: a global history of antibiotics in food production (1935–2017) Palgrave Commun. 2018;4:1–13. doi: 10.1057/s41599-018-0152-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan Y-H, et al. Antibiotics nonadherence and knowledge in a community with the world’s leading prevalence of antibiotics resistance: implications for public health intervention. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2012;40:113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jasovský D, Littmann J, Zorzet A, Cars O. Antimicrobial resistance—a threat to the world’s sustainable development. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2016;121:159–164. doi: 10.1080/03009734.2016.1195900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WB. Pulling Together to Beat Superbugs Knowledge and Implementation Gaps in Addressing Antimicrobial Resistance. (World Bank, 2019).

- 5.Zhang Y, Bi P, Hiller JE. Climate variations and Salmonella infection in Australian subtropical and tropical regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2010;408:524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukonzo JK, et al. Over-the-counter suboptimal dispensing of antibiotics in Uganda. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2013;6:303. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S49075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medernach RL, Logan LK. The growing threat of antibiotic resistance in children. Infect. Dis. Clin. 2018;32:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.URT. Tanzania National Antimicrobial Resistsnce Action Plan. (United Republic of Tanzania, 2017).

- 9.WHO. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. (World Health Organization, 2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Al-Niemat SI, Aljbouri TM, Goussous LS, Efaishat RA, Salah RK. Antibiotic prescribing patterns in outpatient emergency clinics at Queen Rania Al Abdullah II Children's Hospital, Jordan, 2013. Oman Med. J. 2014;29:250. doi: 10.5001/omj.2014.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuzuki S, et al. Factors associated with sufficient knowledge of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance in the Japanese general population. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60444-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarwar MR, Saqib A, Iftikhar S, Sadiq T. Knowledge of community pharmacists about antibiotics, and their perceptions and practices regarding antimicrobial stewardship: a cross-sectional study in Punjab, Pakistan. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018;11:133. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S148102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zajmi, D. et al. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding antibiotic use in Kosovo. Pharm. Practice (Granada)15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Cantarero-Arévalo L, Hallas MP, Kaae S. Parental knowledge of antibiotic use in children with respiratory infections: A systematic review. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2017;25:31–49. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.URT. 2012 Population and Housing Census Population Distribution by Administrative areas., (United Republic of Tanzania, 2012).

- 16.Reed SD, Laxminarayan R, Black DJ, Sullivan SD. Economic issues and antibiotic resistance in the community. Ann. Pharmacother. 2002;36:148–154. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MoHCDEC. Guideline for Regional Referral Hospital Advisory Board. (Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children, 2016).

- 18.Simon B, Kazaura M. Prevalence and factors associated with parents self-medicating under-fives with antibiotics in Bagamoyo District Council, Tanzania: A cross-sectional study. Patient Prefer. Adherence. 2020;14:1445. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S263517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sadasivam K, Chinnasami B, Ramraj B, Karthick N, Saravanan A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of paramedical staff towards antibiotic usage and its resistance. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2016;9:337–343. doi: 10.13005/bpj/944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Remesh A, Gayathri A, Singh R, Retnavally K. The knowledge, attitude and the perception of prescribers on the rational use of antibiotics and the need for an antibiotic policy—a cross sectional survey in a tertiary care hospital. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013;7:675. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5413.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buuml, S. C. Y. K. A. & Alhan, S. E. Knowledge and behavior of the pediatricians on rational use of antibiotics. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 4, 783–792 (2010).

- 22.Nair, M. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to antibiotic use in Paschim Bardhaman District: A survey of healthcare providers in West Bengal, India. PLoS One14, e0217818 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Thriemer, K. et al. Antibiotic prescribing in DR Congo: A knowledge, attitude and practice survey among medical doctors and students. PloS one 8, e55495 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Mouhieddine TH, et al. Assessing the Lebanese population for their knowledge, attitudes and practices of antibiotic usage. J. Infect. Public Health. 2015;8:20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mbwambo G, Emidi B, Mgabo MR, Sigall GN, Kajeguka DC. Community knowledge and attitudes on antibiotic use in Moshi Urban, Northern Tanzania: Findings from a cross sectional study. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2017;11:1018–1026. doi: 10.5897/AJMR2017.8583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agarwal, S., Yewale, V. N. & Dharmapalan, D. Antibiotics use and misuse in children: a knowledge, attitude and practice survey of parents in India. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR 9, SC21 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Vinker S, Ron A, Kitai E. The knowledge and expectations of parents about the role of antibiotic treatment in upper respiratory tract infection—a survey among parents attending the primary physician with their sick child. BMC Fam. Pract. 2003;4:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rouusounides A, et al. Descriptive study on parents’ knowledge, attitudes and practices on antibiotic use and misuse in children with upper respiratory tract infections in Cyprus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2011;8:3246–3262. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8083246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panagakou SG, et al. Antibiotic use for upper respiratory tract infections in children: A cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of parents in Greece. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyodo T, et al. Tandem paired nicking promotes precise genome editing with scarce interference by p53. Cell Rep. 2020;30:1195–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abbas Q, et al. Evaluation of antibiotic use in pediatric intensive care unit of a developing country. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2016;20:291. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.182197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuzujanakis M, Kleinman K, Rifas-Shiman S, Finkelstein JA. Correlates of parental antibiotic knowledge, demand, and reported use. Ambul. Pediatr. 2003;3:203–210. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0203:COPAKD>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bosley H, Henshall C, Appleton JV, Jackson D. A systematic review to explore influences on parental attitudes towards antibiotic prescribing in children. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018;27:892–905. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stivers T. Participating in decisions about treatment: overt parent pressure for antibiotic medication in pediatric encounters. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002;54:1111–1130. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faidah HS, et al. Parents’ self-directed practices towards the use of antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections in Makkah Saudi Arabia. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1376-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alumran A, Hurst C, Hou X-Y. Antibiotics overuse in children with upper respiratory tract infections in Saudi Arabia: Risk factors and potential interventions. Clin. Med. Diagn. 2011;1:8–16. doi: 10.5923/j.cmd.20110101.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung A, et al. Effect of antibiotic prescribing on antibiotic resistance in individual children in primary care: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2007;335:429. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39274.647465.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sa’ed, H. Z. et al. Parental knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding antibiotic use for acute upper respiratory tract infections in children: a cross-sectional study in Palestine. BMC Pediatr. 15, 1–9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Chan, G. & Tang, S. Parental knowledge, attitudes and antibiotic use for acute upper respiratory tract infection in children attending a primary healthcare clinic in Malaysia. (2013). [PubMed]

- 40.Awad, A. I. & Aboud, E. A. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards antibiotic use among the public in Kuwait. PloS one 10, e0117910 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.El Khoury G, Ramia E, Salameh P. Misconceptions and malpractices toward antibiotic use in childhood upper respiratory tract infections among a cohort of Lebanese parents. Eval. Health Prof. 2018;41:493–511. doi: 10.1177/0163278716686809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.