Abstract

We assessed the effects of hydroxyurea (HU) at a concentration of 50 μM on the in vitro activities of 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine (ddI), 9-[2-(phosphonylmethoxy)ethyl]adenine (PMEA), and 9-[2-(phosphonylmethoxy)propyl]adenine (PMPA) against a wild-type human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 (HIV-1) laboratory isolate and a panel of five well-characterized drug-resistant HIV isolates. Fifty micromolar HU significantly increased the activities of ddI, PMEA, and PMPA against both the wild-type and the drug-resistant HIV-1 isolates. In fixed combinations, both ddI and PMEA were synergistic with HU against wild-type and drug-resistant viruses.

The experimental human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitors 9-[2-(phosphonylmethoxy)ethyl]adenine (PMEA) and 9-[2-(phosphonylmethoxy)propyl]adenine (PMPA) are acyclic phosphonate analogs of AMP (3, 26, 32). Although they already contain a single phosphate, PMEA and PMPA, like other nucleoside analogs, rely on intracellular kinases for phosphorylation to their active diphosphate forms (27, 28). The diphosphates of PMEA and PMPA and the triphosphate of 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine (ddI) (ddATP) compete with the cellular nucleotide dATP for the active binding sites on the RT enzyme (1, 8). Therefore, the antiretroviral activities of PMEA, PMPA, and ddI are dependent on two factors: (i) the activities of intracellular phosphorylating enzymes and (ii) the ratio of the amount of phosphorylated drug to the amount of competing intracellular nucleoside triphosphate pools.

The anticancer agent hydroxyurea (HU) is used for the treatment of myleoproliferative disorders (9, 34). HU is a potent inhibitor of the cellular enzyme ribonucleotide reductase, which catalyzes the reduction of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides (14). Cells exposed to HU show measurable reductions in several deoxynucleotide pools, with the reduction of dATP pools being the most pronounced (4, 10–12, 24). These decreases in deoxynucleotide pools effectively block cellular DNA synthesis (4).

HU increases the anti-HIV activities of ddI and 2′-β-fluoro-2′,3′-dideoxyadenosine, probably due to the favorable shift in the ratio of adenosine drug triphosphates versus competing cellular dATP pools which favors the binding of drug triphosphates to RT (4, 10–13, 18, 24). Due to these promising in vitro results, several clinical trials of ddI in combination with HU have been initiated (5–7, 17, 35, 36).

In the present study, we investigated the effects of HU on the anti-HIV activities of the three adenosine analogs PMEA, PMPA, and ddI. We assessed the interaction of HU with these drugs against wild-type HIV and versus a panel of drug-resistant HIV strains. We also analyzed the cytotoxicity of HU alone and in combination with PMEA, PMPA, or ddI.

HIV-1 strains.

The antiviral activities of the drugs and drug combinations were assessed against six different HIV type 1 (HIV-1) strains: a wild-type laboratory isolate (HIVNL4-3), three recombinant isolates containing ddI resistance mutations (HIVK65R, HIVL74V, and HIVL74V, M184V), one molecularly constructed multinucleoside-resistant strain (HIVV75I, F77L,F116Y, Q151M) (15), and a recently reported multidrug-resistant clinical isolate containing six major RT mutations (HIVM41L, D67N, M184V, L210W, T215Y, K219N) (30).

Sequence analysis of HIV-1 strains.

A 1.3-kb fragment of cDNA encompassing HIV-1 protease and the first 300 codons of RT was sequenced from each cultured supernatant as described previously (38). Briefly, purified viral RNA (Qiagen Viral RNA Extraction Kits Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.) was reverse transcribed and amplified by PCR with the Superscript-One-Step-RT-PCR Reagent (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) and two primers, MAW-26 and RT21 (23). A 5-μl aliquot of the first PCR product was used for a second-round nested PCR with primers PRO-1 (29) and RT20 (23). Approximately 70 ng of the 1.3-kb product was sequenced by dye-labelled dideoxyterminator cycle sequencing (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Isolate sequences were compared to both patient plasma sequences and the consensus B sequence from the Los Alamos HIV Sequence Database (21).

Drug susceptibility assays.

In vitro drug susceptibility assays were performed by a modified AIDS Clinical Trials Group–U.S. Department of Defense consensus method (virology manual for ACTG HIV laboratories, 1997). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were preinfected with titrated viral stocks for 4 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Each microtiter plate well contained 100,000 preinfected PBMCs and eight serial drug dilutions in cell media of ddI, PMEA, PMPA, 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine (AZT), 2′-deoxy-3′-thiacytidine (3TC), or indinavir (IDV) in the presence or absence of 50 μM HU. A 50 μM concentration of HU was used since it is in the range of the average steady-state HU concentration in serum during HIV treatment (35 to 56 μM) (37). An 8:1 series of combinations of ddI and HU or PMEA and HU was also analyzed. The drug dilutions were chosen to span the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of each single drug (2, 3, 25, 26, 32). The drugs were combined in fixed clinically achievable ratios, based on the relative potencies of the drugs, by the median-effect method of analyzing drug interactions. Control wells containing cells and virus were coincubated on each plate.

To enable assay standardization and comparison, the 50% tissue culture infective dose of each isolate was maintained at between 30 and 100. After a 7-day incubation at 37°C and in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, viral growth was determined by a p24 antigen assay with supernatants (Dupont Pharmaceuticals, Wilmington, Del.). The percent inhibition of viral growth compared to the viral growth in the control wells without drugs was calculated. Results were expressed as the mean IC50 of four to six values obtained in two to three different experiments per isolate.

The results for the two-drug combinations were calculated by using a computer program that follows the median-effect principle. The computer constructs a median-effect plot of log fraction affected/fraction unaffected against the log of the dose of the two separate drugs and the dose of the combination. A combination index (CI), which compares the amount of drug which gives a 50% effect when used in combination with that which gives a 50% effect when the drug is used alone, is calculated. A CI of <1 indicates synergy, and a CI of >1 indicates antagonism. However, in accordance with variation in raw data, CIs of between 0.8 and 1.2 were considered to represent additivism.

Cytotoxicity assays.

Thymidine uptake analyses were used to assess the effects of the drugs on cellular DNA synthesis. Phytohemagglutinin-stimulated PBMCs were plated at 100,000 cells per well and exposed to 3.1, 12.5, and 50 μM concentrations of ddI, PMEA, or PMPA in the presence or absence of HU at concentrations of 25 to 500 μM. Control cells, without drugs, were coincubated on each plate and were used for comparison when measuring inhibition of cellular DNA synthesis by the drugs. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 7 days. Sixteen hours prior to cell harvest, 50 μCi of [3H]thymidine was introduced into all wells. The cells were harvested onto preprinted filter paper with rinsings of water and 95% ethanol. After drying at 37°C, scintillant was added and the counts on the filters were determined with a Wallac beta counter (LKB Wallac, Turku, Finland).

The presence of 50 μM HU decreased the IC50s of ddI in vitro, which enhanced the anti-HIV activity of ddI against all viral strains analyzed (Table 1). The IC50 of ddI for many of the ddI-resistant viral strains was reduced to less than the range for the wild type in the presence of HU. These observations are consistent with previous studies showing that HU at concentrations of 50 to 100 μM increased the activity of ddI (11, 12). Moreover, recent clinical studies have shown that patients who respond to ddI and HU therapy may harbor ddI-resistant viral strains (7). Further in vitro analysis found that these resistant strains are phenotypically sensitive to inhibition by ddI and HU (19). Similar to ddI, the IC50s of the acyclic adenosine derivatives PMEA and PMPA were decreased by the presence of 50 μM HU for all viruses analyzed, including five drug-resistant strains: HIVK65R, HIVL74V, HIVL74V, M184V; HIVV75I, F77L, F116Y, Q151M; and HIVM41L, D67N, M184V, L210W, T215Y, K219N.

TABLE 1.

Effect of HU on antiviral activities of ddI, PMEA, and PMPA against a wild-type laboratory isolate and drug-resistant HIV-1 strains

| Viral strain or isolate and presence of HU | IC50 (μM)a in

culture

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ddI | PMEA | PMPA | |

| HIV-1NL4-3 | |||

| Without HU | 0.38 ± 0.06 | 3.1 ± 0.77 | 1.3 ± 0.02 |

| With 50 μM HU | <0.05 (>8)b | 0.37 ± 0.12 (8) | <0.05 (>26) |

| HIV-1K65Rc | |||

| Without HU | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 13.4 ± 1.3 | 4.9 ± 0.9 |

| With 50 μM HU | <0.05 (>46) | 0.10 ± 0.1 (134) | 0.08 ± 0.1 (61) |

| HIV-1L74V | |||

| Without HU | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.5 |

| With 50 μM HU | <0.05 (>24) | 0.29 ± 0.03 (14) | <0.05 (>34) |

| HIV-1L74V, M184V | |||

| Without HU | 3.9 ± 0.06 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| With 50 μM HU | <0.05 (>78) | <0.05 (>32) | <0.05 (>22) |

| HIV-1V75I, F77L, F116Y, Q151M | |||

| Without HU | 38 ± 3.9 | 8.7 ± 0.3 | 6.4 ± 0.58 |

| With 50 μM HU | 1.7 ± 0.45 (22) | 1.9 ± 0.39 (5) | 0.2 ± 0.06 (32) |

| HIV-1M41L, D67N, M184V, L210W, T215Y, K219N | |||

| Without HU | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 5.1 ± 0.64 | 2.6 ± 0.72 |

| With 50 μM HU | 0.2 ± 0.15 (18) | 1.4 ± 0.42 (4) | 0.4 ± 0.02 (7) |

Results are expressed as the means ± standard deviations of four to six values obtained in two to three different experiments.

Values in parentheses are the fold decrease in IC50 of each compound in the presence of HU. The HU-induced decrease in drug IC50s were statistically significant (P < 0.001; two tailed t test).

Subscripts are resistance mutations of the RT gene.

The HU-induced reductions in IC50s of ddI, PMEA, and PMPA for the wild-type isolate were from 8- to >26-fold (Table 1), whereas in parallel experiments the reduction in IC50s of AZT, 3TC, and IDV for the wild type were between 2- and 5-fold (data not shown). The HU-induced fold decrease in IC50s of these drugs for the wild-type strain could be ranked as PMPA ≥ ddI > PMEA > AZT > 3TC > IDV. The differences of these drug IC50s may be attributed to the effects of HU, a known inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase, upon intracellular nucleotide pools (4, 10–12, 24). Cells exposed to HU experience a severe loss in dATP pools. After 5 days of continuous exposure to HU, the levels of dATP pools remain lower than those in control cells not exposed to HU (11). In contrast, studies show that natural dTTP and dCTP pools and the thymidine and deoxycytidine phosphorylating enzymes are elevated in cells exposed to HU (4, 10–12, 24). Consequently, in HU-treated cells, the ratio of phosphorylated adenosine analogs (ddATP, PMEA diphosphosphate, or PMPA diphosphate) to natural dATP may be substantially higher than the ratios of AZT-triphosphate/dTTP or 3TC-triphosphate/dCTP. The shift of the phosphorylated adenosine analogs/dATP ratio favors the binding of the analog to RT and is the probable cause of the more pronounced effect of HU on the anti-HIV activities of the adenosine analogs (ddI, PMEA, and PMPA) versus AZT and 3TC. The anti-HIV activity of IDV is independent of intracellular nucleotide levels, which may explain the limited effect of HU upon the activity of this protease inhibitor. Furthermore, HU at a concentration of 50 μM was found to inhibit viral growth by approximately 30%, or 0.3-fold; therefore, the fold decreases in drug IC50s were not overly influenced by the inherent anti-HIV activity of HU.

The HU-induced decreases in drug IC50s were greatest for the HIVK65R, HIVL74V, and HIVL74V, M184V recombinant isolates (Table 1). Recent studies have shown that the specific activity is diminished for mutant RT enzymes containing ddI-resistant mutations including enzymes with K65R or L74V mutations (20, 31). The combination of reduced specific activity and HU-induced reduction in cellular nucleotide pools may cause the increased susceptibilities of these recombinants to inhibition by antiretroviral drugs in the presence of HU.

The IC50s of HU remained relatively constant (approximately 83 μM) for wild-type and resistant viral strains. These observations suggest that the RT gene mutations of the viral strains in this study have little effect on the inherent anti-HIV activity of HU (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Antiviral susceptibilities of a laboratory HIV-1 isolate and drug-resistant isolates to two-drug combinations

| Isolate and drug | IC50

(μM)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ddI | PMEA | HU | |

| HIV-1NL4-3 | |||

| Single drugs | 0.38 | 3.1 | 89 |

| ddI-HU (1:8) | 0.24 | 2.0 | |

| PMEA-HU (1:8) | 1.3 | 10 | |

| HIV-1V75I, F77L, F116Y, Q151Mb | |||

| Single drugs | 38 | 8.7 | 83 |

| ddI-HU (1:8) | 5.1 | 41 | |

| PMEA-HU (1:8) | 3.0 | 24 | |

| HIV-1M41L, D67N, M184V, L210W, T215Y, K219N | |||

| Single drugs | 3.5 | 5.1 | 76 |

| ddI-HU (1:8) | 1.2 | 9.7 | |

| PMEA-HU (1:8) | 1.9 | 15 | |

All experiments were performed at least twice. The variations in the raw data were <20%.

Subscripts are resistance mutations of the RT gene.

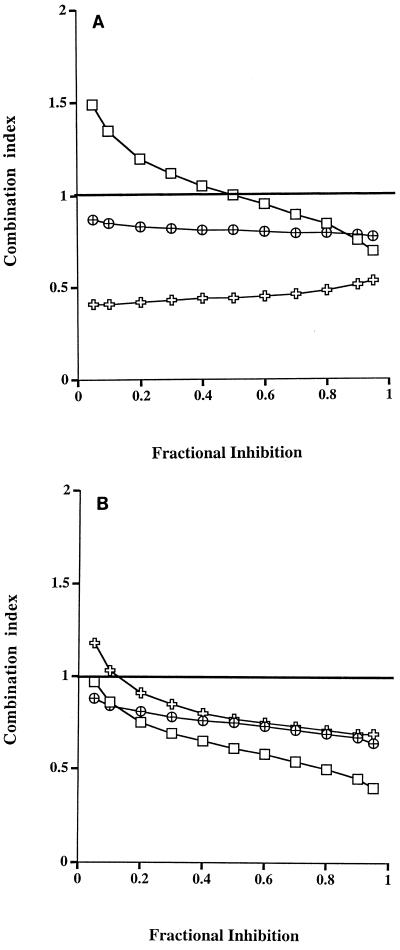

At clinically achievable concentrations, the combinations ddI-HU (1:8) and PMEA-HU (1:8) synergistically inhibited the two drug-resistant viral strains tested, whereas the combination of ddI-HU synergistically inhibited the wild-type isolate at high concentrations of drug (Fig. 1). The mechanism for the synergistic interactions is unknown and may reflect the different modes of action of HU (decreasing cellular nucleotides) and the nucleoside and nucleotide analogs (RT inhibition) (16, 33).

FIG. 1.

Inhibition of HIV-1 isolates, a wild-type strain (HIVNL4-3 [□]) and two drug-resistant strains (HIVV75I, F77L, F116Y, Q151M [ ] and HIVM41L, D67N, M184V, L210W, T215Y, K219N [⊕]), by the combinations ddI-HU (A) and PMEA-HU (B). The variations in the raw data were <20%.

Analysis of thymidine uptake assay results revealed a reduction in cellular DNA synthesis in the presence of HU (Table 3). Although the measurements of thymidine uptake may be affected by the HU-induced increase in intracellular dTTP pools and the extended half-life of these pools in the presence of HU, this observation suggests that HU has a cytostatic effect on cells (4, 22).

TABLE 3.

Effects of ddI, PMEA, and PMPA on the thymidine uptake of PHA-stimulated PMBCs in the presence or absence HU at designated concentrations

| Drug and drug concn (μM) | Counts per minute

(104)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 HU | 25 μM HU | 50 μM HU | 100 μM HU | 500 μM HU | |

| ddI | |||||

| 0 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.08 | 0.86 ± 0.07 | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.04 ± 0.006 |

| 3.1 | 1.3 ± 0.07 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.03 | 0.5 ± 0.04 | 0.03 ± 0.006 |

| 12.5 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.08 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.03 ± 0.007 |

| 50 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.009 | 0.8 ± 0.09 | 0.5 ± 0.05 | 0.03 ± 0.006 |

| PMEA | |||||

| 0 | |||||

| 3.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.06 | 0.6 ± 0.06 | 0.4 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.006 |

| 12.5 | 0.9 ± 0.09 | 0.8 ± 0.03 | 0.6 ± 0.04 | 0.4 ± 0.04 | 0.03 ± 0.003 |

| 50 | 0.5 ± 0.03 | 0.5 ± 0.06 | 0.5 ± 0.04 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.005 |

| PMPA | |||||

| 0 | |||||

| 3.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.05 | 0.8 ± 0.02 | 0.5 ± 0.06 | 0.04 ± 0.003 |

| 12.5 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.06 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.04 ± 0.003 |

| 50 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.02 | 0.5 ± 0.03 | 0.04 ± 0.005 |

In conclusion, the presence of HU at low, clinically tolerated concentrations enhances the anti-HIV activities of ddI, PMEA, and PMPA. This HU-induced increase in the activities of ddI, PMEA, and PMPA against HIV is also observed in clinical isolates that are resistant to one or more of these compounds. The two-drug combinations ddI-HU and PMEA-HU synergistically inhibited drug-resistant viral strains. This study provides evidence that supports the need for clinical trials with HU (i) in combination with ddI against ddI-resistant patient isolates and (ii) in combination with two recently developed adenosine analogs, PMEA and PMPA. Moreover, the strategy of combining highly specific HIV inhibitors with relatively nonspecific inhibitors is an approach to drug resistance that should be tested clinically.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gilead Sciences, Foster City, Calif., for the kind gifts of PMEA and PMPA. We especially thank Darcy Levee and Kristi Cooley for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arts E J, Wainberg M A. Preferential incorporation of nucleoside analogs after template switching during human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcription. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1008–1016. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.5.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balzarini J, Naesens L, Slachmuylders J, Niphuis H, Rosenberg I, Holy A, Schellekens H, De Clercq E. 9-(2-Phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine (PMEA) effectively inhibits retrovirus replication in vitroand simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus monkeys. AIDS. 1991;5:21–28. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199101000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balzarini J, Vahlenkamp T, Egberink H, Hartmann K, Witvrouw M, Pannecouque C, Casara P, Nave J F, De Clercq E. Antiretroviral activities of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates [9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine, 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)guanine, (R)-9-(2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)adenine, and MDL 74,968] in cell cultures and murine sarcoma virus-infected newborn NMRI mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:611–616. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bianchi V, Pontis E, Reichard P. Changes of deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate pools induced by hydroxyurea and their relation to DNA synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:16037–16042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biron F, Lucht F, Peyramond D, Fresard A, Vallet T, Nugier F, Grange J, Malley S, Hamedi-Sangsari F, Vila J. Anti-HIV activity of the combination of didanosine and hydroxyurea in HIV-1-infected individuals. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;10:36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biron F, Lucht F, Peyramond D, Fresard A, Vallet T, Nugier F, Grange J, Malley S, Hamedi-Sangsari F, Vila J. Pilot clinical trial of the combination of hydroxyurea and didanosine in HIV-1 infected individuals. Antivir Res. 1996;29:111–113. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00931-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Antoni A, Foli A, Lisziewicz J, Lori F. Mutations in the pol gene of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in infected patients receiving didanosine and hydroxyurea combination therapy. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:899–903. doi: 10.1086/516511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Clercq E. HIV inhibitors targeted at the reverse transcriptase. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8:119–134. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donehower R C. An overview of the clinical experience with hydroxyurea. Semin Oncol. 1992;19(Suppl. 9):11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao W-Y, Cara A, Gallo R C, Lori F. Low levels of deoxynucleotides in peripheral blood lymphocytes: a strategy to inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8925–8928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao W-Y, Johns D G, Chokekijchai S, Mitsuya H. Disparate actions of hydroxyurea in potentiation of purine and pyrimidine 2′,3′-dideoxynucleoside activities against replication of human immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8333–8337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao W-Y, Johns D G, Mitsuya H. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity of hydroxyurea in combination with 2′,3′-dideoxynucleosides. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:767–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao W Y, Mitsuya H, Driscoll J S, Johns D G. Enhancement by hydroxyurea of the anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 potency of 2′-beta-fluoro-2′,3′-dideoxyadenosine in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:274–276. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00106-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurta R A, Wright J A. Amplification of the genes for both components of ribonucleotide reductase in hydroxyurea resistant mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;167:258. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91759-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iversen A K N, Shafer R W, Wehrly K, Winters M A, Mullins J I, Chesebro B, Merigan T C. Multidrug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains resulting from combination antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 1996;70:1086–1090. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1086-1090.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johns D G, Gao W Y. Selective depletion of DNA precursors: an evolving strategy for potentiation of dideoxynucleoside activity against human immunodeficiency virus. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:1551–1556. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00664-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lori F, Jessen H, Foli A, Lisziewicz J, Matteo P S. Long-term suppression of HIV-1 by hydroxyurea and didanosine. JAMA. 1997;277:1437–1438. . (Letter.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lori F, Malykh A, Cara A, Sun D, Weinstein J N, Lisziewicz J, Gallo R C. Hydroxyurea as an inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 replication. Science. 1994;266:801–805. doi: 10.1126/science.7973634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lori F, Malykh A G, Foli A, Maserati R, De Antoni A, Minoli L, Padrini D, Degli Antoni A, Barchi E, Jessen H, Wainberg M A, Gallo R C, Lisziewicz J. Combination of a drug targeting the cell with a drug targeting the virus controls human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:1403–1409. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller M D, Lamy P D, Fuller M D, Mulato A S, Margot N A, Cihlar T, Cherrington J M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase expressing the K70E mutation exhibits a decrease in specific activity and processivity. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:291–297. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers G, Korber B, Foley B, Jeang K-T, Mellors J W, Wain-Hobson S. Human retroviruses and AIDS 1996: a compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos, N.M: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicander B, Reichard P. Relations between synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides and DNA replication in 3T6 fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:5376–5381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nijhuis M, Boucher C A B, Schuurman R. Sensitive procedure for amplification of HIV-1 RNA using a combined reverse transcriptase and amplification reaction. BioTechniques. 1995;19:178–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer S, Cox S. Increased activation of the combination of 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine and 2′-deoxy-3′-thiacytidine in the presence of hydroxyurea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:460–464. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer S, Harmenberg J, Cox S. Synergistic inhibition of HIV isolates (including 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine-resistant isolates) by foscarnet in combination with 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine or 2′,3′-dideoxycytidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1285–1288. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pauwels R, Balzarini J, Schols D, Baba M, Desmyter J, Rosenberg I, Holy A, De Clercq E. Phosphonylmethoxyethyl purine derivatives, a new class of anti-human immunodeficiency virus agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1025–1030. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.7.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robbins B L, Greenhaw J, Connelly M C, Fridland A. Metabolic pathways for activation of the antiviral agent 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine in human lymphoid cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2304–2308. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.10.2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robbins B L, Srinivas R V, Kim C, Bischofberger N, Fridland A. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity and cellular metabolism of a potential prodrug of the acyclic nucleoside phosphonate 9-R-(2-phosphonomethoxypropyl)adenine (PMPA), bis(isopropyloxymethylcarbonyl) PMPA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:612–617. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schapiro J M, Winters M A, Stewart F, Efron B, Norris J, Kozal M J, Merigan T C. The effect of high-dose saquinavir on viral load and CD4 T-cell counts in HIV-infected patients. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:1039–1050. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-12-199606150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shafer R W, Winters M A, Palmer S, Merigan T C. Multiple concurrent reverse transcriptase and protease mutations and multidrug resistance of HIV-1 isolates from heavily treated HIV-1 infected patients. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:906–911. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-11-199806010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma P L, Crumpacker C S. Attenuated replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with a didanosine-selected reverse transcriptase mutation. J Virol. 1997;71:8846–8851. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8846-8851.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith M S, Brian E L, De Clercq E, Pagano J S. Susceptibility of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in vitro to acyclic adenosine analogs and synergy of the analogs with 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1482–1486. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.9.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sommadossi J P. Nucleoside analogs: similarities and differences. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16(Suppl. 1):S7–S15. doi: 10.1093/clinids/16.supplement_1.s7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tracewell W G, Trump D L, Vaughan W P, Smith D C, Gwilt P R. Population pharmacokinetics of hydroxyurea in cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995;35:417–422. doi: 10.1007/s002800050256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vila J, Biron F, Nugier F, Vallet T, Peyramond D. 1-year follow-up of the use of hydroxycarbamide and didanosine in HIV infection. Lancet. 1996;348:203–204. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)66157-0. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vila J, Nugier F, Bargues G, Vallet T, Peyramond D, Hamedi-Sangsari F, Seigneurin J M. Absence of viral rebound after treatment of HIV-infected patients with didanosine and hydroxycarbamide. Lancet. 1997;350:635–636. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)24035-3. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villani P, Maserati R, Regazzi M B, Giacchino R, Lori F. Pharmacokinetics of hydroxyurea in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type I. J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;36:117–121. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1996.tb04176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winters M A, Schapiro J M, Lawrence J, Merigan T C. HIV-1 protease genotypes and in vitro protease inhibitor susceptibility from long-term saquinavir-treated individuals who switched to other protease inhibitors. J Virol. 1998;72:5303–5306. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5303-5306.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]