Summary

Nuclear hybrid energy systems (NHES) are a viable option to provide clean power by combining renewable energy sources such as wind and solar. This study analyzes two types of NHES that use small modular reactors (SMR) and wind turbines to produce clean energy and water. The first system uses freeze desalination (FD) and the second system uses reverse osmosis (RO) to produce clean water. Both systems are optimized using net present value at two case locations. The FD system can better meet the energy demand using the stored thermal energy to boost the power during peak hours, which allows less capital investment on its design compared to the RO system. However, the results from the two cases reveal that the RO system can be more economic when water price is more than $1.50/m3. A sensitivity analysis also identified the critical system parameters on the net present value of the systems.

Subject areas: Energy policy, Energy systems

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Two nuclear hybrid energy systems are evaluated to deliver clean energy and water

-

•

The freeze desalination system shows better net present value with power-boosting

-

•

The reverse osmosis system is more economically attractive when water is more valuable

-

•

A penalty function is introduced to account for mismatch of energy demand and supply

Energy policy; Energy systems

Introduction

More than half of the world’s electrical energy needs are currently covered by conventional fossil fuel power plants whose efficiency for a single cycle power plant is significantly lower than that of other plants, such as combined cycle power plants (CCPPs). CCPPs combine two or more thermodynamic cycles, such as a gas turbine with a heat recovery steam generator, enabling an attractive higher efficiency (up to 60%) and providing a reduction in pollutant emissions (Watson, 1996). Coupled with low-cost shale gas, CCPPs have become more and more common over the last decade. At the same time, renewable energies such as wind and solar have seen tremendous growth. With further penetration of renewable energy, it poses a great challenge for traditional power plants as their demands fluctuate considerable within hours. Using the solar energy in CA, US, as an example, the phenomenon has become known as the “duck curve” as shown in Figure 1. During the day when plenty of solar energy is available, it depresses the power generation from traditional power plants. After sunset, the ramp rate required for meeting the energy needs puts tremendous stress on traditional power generation systems (Jones-Albertus, 2017). This requires power plants to be more flexible in meeting the power demands.

Figure 1.

The ‘Duck Curve’ published by CAISO in 2013 shows how solar energy can cause the net load on the power grid to fluctuate throughout the day

To keep the efficiency of the power plant as high as possible and to decrease the thermo-mechanical fatigue, it is desirable to maintain the power generation at full capacity (Benato et al., 2016, pp. 76–85). The challenge is to store the energy that the power plant generates during off-peak hours to then be used during peak hours to reduce the stress on the power plant during peak hours. This requires a dynamic control strategy that can respond to the variable working conditions to store as much energy as possible during off-peak hours and then release the stored energy at the optimal time and rate during peak hours to reduce the stress on the power plant.

One way to increase the reliability of systems using renewable energy and decrease the influence of energy fluctuations is to use a hybrid energy system (HES). Hybrid energy systems combine two or more forms of renewable energy sources, as well as energy storage, to improve system performance and energy reliability, and to overcome limitations inherent in single energy sources. The operator of hybrid energy systems decides on the optimal scheduling of its resources and trading power with the main grid in an optimal way (Taghizadeh et al., 2020). A more specific type of HES is the Nuclear Hybrid Energy System (NHES). NHESs have the potential to produce commodities such as electricity and hydrogen and allow for electricity grid load following (Pinsky et al., 2020). A benefit of using an NHES is that the reactor can continuously operate at full capacity, so the fluctuation in power output is not as large as compared to a system that only relies on wind or solar power. Also, this system can potentially provide carbon-free energy production. Ongoing research has looked into the use of NHES and the apprehensions of the public (Suman, 2018, pp. 166–177), the use of small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs) in system design (Bragg-Sitton, 2021, pp. 323–356), and adding other power sources, such as solar, along with water desalination to improve economic and system efficiency (Wang et al., 2021).

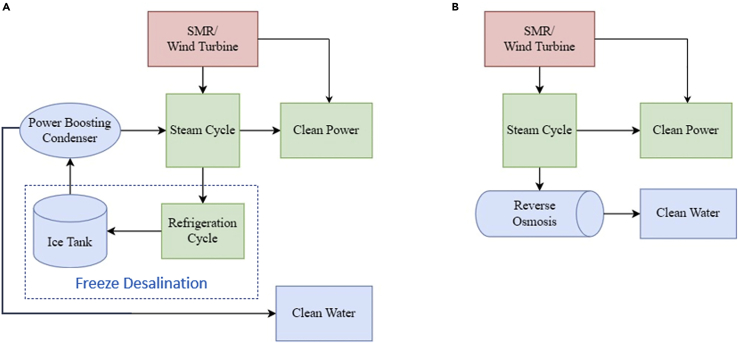

In this study, two NHESs that can meet the power demand of a given region cost effectively while producing clean water have been designed and optimized. The first NHES uses freeze desalination (FD) to both store thermal energy to boost power production during peak hours and produce clean water. This optimized system is compared to the second NHES that uses excess power to run a Reverse Osmosis (RO) system to generate clean water. The sizing of the components and the number of components is optimized to avoid over-producing while meeting the power demands. The schematic diagrams of both NHES designs are shown in Figure 2. For the FD system, when there is excess power from the SMRs and wind turbines (usually during low power demand periods), the refrigeration cycle is turned on to produce ice out of the seawater (or salt water in general). When the power demand exceeds the total power outputs from the SMRs and wind turbines (i.e., peak energy demand periods), the stored ice is used to lower the steam cycle condensing temperature/pressure through the power-boosting condenser, and increase the steam cycle efficiency and power output. After utilizing its latent heat, the thawed water becomes a source of clean water. In contrast, the RO system is a simpler system. It produces clean water when there is excess power from the SMRs and wind turbines. However, it does not provide the energy storage and power boosting functions. In comparing these two systems, the Net Present Value (NPV) is used to see which system is more advantageous for a given power demand, air temperatures and wind profiles.

Figure 2.

A high-level schematic of two integrated clean energy-water systems modeled

(A) includes a refrigeration cycle and ice tanks for thermal storage and power boosting.

(B) uses reverse osmosis to produce clean water.

Recent research has been done on the dynamic modeling of combined-cycle power plants, specifically those with a gas turbine unit coupled to a heat recovery steam generator (Casella and Colonna, 2012, pp. 91–111; Casella and Pretolani, 2006; Casella et al., 2011, pp. 9549–9554). The Modelica language has been used to model the dynamics of these power plants and investigate the stresses on them during start up. Work has also been done using Modelica to optimize the control of a combined-cycle power plant to reduce the stresses during fluctuations in power demand. This is of growing importance as the fluctuation of power demand for power plants continues to increase.

One of the main challenges in using a hybrid energy system effectively is optimizing it for size and cost. Much research has been done and is continuing to be done on optimization techniques for HES (Sanajaoba, 2019, pp. 655–666; Duman and Guler, 2018, pp. 107–126; Gharibi and Askarzadeh, 2019, pp. 25428–25441). When using Modelica to model a system, there are multiple choices of software available for optimization. One option is to load the model in MATLAB and use it for optimization (Tica et al., 2012, pp. 256–265). Another software that has been used to optimize a Modelica model is CasADi (Shitahun et al., 2013, pp. 446–451). Some other software that is designed specifically for Modelica and for dynamic optimization is Optimica and JModelica.org (Akesson et al., 2010, pp. 1737–1749). Another important aspect when modeling a system using Modelica is to make sure that it is as simplified as possible to reduce the compilation time. It is important to have a powerful solver, especially when optimizing a complex dynamic system as it can dramatically decrease the time needed to run the model (Cafferkey and Provan, 2015, pp. 210–215). One such possible solver, developed by the Idaho National Laboratory, is RAVEN. It can perform adaptive samplings of large input spaces and can create reduced order models representative of the input space (Rouxelin et al., 2020).

RAVEN stands for Risk Analysis and Virtual Environment. It is a multipurpose probabilistic and uncertainty quantification framework, capable of communicating with any system code, implemented with an integrated validation methodology involving several different metrics (Narcisi et al., 2019, pp. 419–432). It is a useful tool for analyzing systems as it can integrate the system code with various plugins that are available to RAVEN to perform system optimization and economic analysis. One such plugin for economic analysis in RAVEN is TEAL. RAVEN communicates with other software code, such as OpenModelica, through XML files. RAVEN can be used to run multiple iterations of a simulation with the prescribed variables being altered to see how the system responds. Outputs from the simulation can be saved and plots can be generated by RAVEN to visualize the results. The outputs from the simulations can also be used by other plugins, such as TEAL, to perform economic analysis. TEAL stands for Tool for Economic AnaLysis. It is a RAVEN plugin that is used to deploy economic analysis for RAVEN workflows. TEAL can compute economic metrics such as NPV (Net Present Value).

Water desalination techniques

As demand for clean water increases, generating clean water from excess power production is becoming more common. There are currently many possible techniques available for the desalination of seawater. Among these are Reverse Osmosis (RO) (Di Martino et al., 2011), Freeze Desalination (FD) (Shin et al., 2019, pp. 68–74), Forward Osmosis (FO) (Zhang and Liu, 2021), Membrane Distillation (MD) (Bandar et al., 2021) and Capacitive Deionization (CDI) (Pawlowski et al., 2020). Although Reverse Osmosis is currently the most widely adopted technique, some of these other emerging technologies offer significant advantages over RO, such as higher salt rejection (CDI, MD), higher recovery of water (MD), fewer pre-treatment stages (MD, FO) and the ability to use low-grade energy (MD, FO). Currently, stand-alone technologies cannot compete with RO until certain challenges are addressed, such as high energy consumption (Skuse et al., 2021).

Ice-based Freeze Desalination (FD) is a technique to recover fresh water from seawater that has been receiving increased interest over the years (Sahu et al., 2020). It involves the cooling of saline water below freezing whereas the salt remains in the solution. The ice crystals can subsequently be separated from the concentrated brine, washed and melted to obtain clean water (Shi et al., 1990, pp. 316–328). Some of the advantages of FD is that the energy required to freeze water is only 1/7 of its latent heat of vaporization, which means FD can be more effective on energy utilization than the distillation process. Also, corrosion and scaling can be negligible during the heat exchange because of the low operating temperature. An added benefit is that there is no discharge of hazardous chemicals into the environment (Xie et al., 2018, pp. 293–300). Although FD is a promising desalination technique and the process could potentially be coupled with energy storage, effective separation produced ice and brine in order to achieve acceptable salinity level has been challenging. Reverse Osmosis is an effective approach toward molecular separation and is widely used commercially for desalination of seawater (Vatanpour and Zoqi, 2017, pp. 1478–1489). It works by using a partially permeable membrane to push pressurized water through, while preventing larger particles, such as salt, through the membrane. An advantage of reverse osmosis over some of the other desalination techniques is higher energy efficient, which leads to lower levelized cost of water (Okampo and Nwulu, 2021). Some of its drawbacks include membrane degradation because of fouling or corrosion. However, research is currently being done to improve the membrane, allowing for enhanced desalination, anti-fouling and durability properties (Liu et al., 2021).

Modeling

In this work, OpenModelica has also been chosen as the dynamic modeling tool to simulate the processes of the two NHES systems (for detailed information of the FD and RO systems, please refer to a recent publication (Hills et al., 2021)). The OpenModelica models leverage some of the components already developed in the open-sourced Modelica libraries and ThermoPower library. Compared to other dynamic modeling tools such as Matlab/Simulink, Modelica as an object-oriented programming language allows the modelers to focus on the physical process modeling with little concern about the optimal/efficient solution algorithms. Figure 3 shows the overall OpenModelica model of the FD system, including the steam cycle, the refrigeration cycle, the wind turbines, the ice/water tanks and the cooling tower, along with the inputs and connections for those components. There is a legend at the top that shows what the icon is for each of the major parts in the system.

Figure 3.

Overall model in OpenModelica

The NHES was modeled using OpenModelica, making use of some of the component models already in the Modelica and ThermoPower libraries. The overall OpenModelica model of the NHES is shown in Figure 3. It shows the major parts of the system: the steam cycle, the refrigeration cycle, the wind turbines, the ice/water tanks and the cooling tower. The legend at the top shows what the icon is for each of the major parts in the system. The steam cycle and refrigeration cycle shown in Figure 3 can be expanded to display the individual components that make up both cycles. Note that an in-depth explanation on how the components in the system were modeled can be found in a recent publication (Hills et al., 2021).

Figure 4 shows the OpenModelica model for the steam cycle with its major components. The cycle is simplified compared to a more complex real-life steam cycle it represents. It has a power-boosting condenser (PBC) as shown to further cool down the cooling tower return water. The turbine has a lumped efficiency equivalent to a system with regeneration. Inputs to the steam cycle are the mass flow rate, thermal power from the reactor, the return water mass flow rate and temperature from the cooling tower and the ice water mass flow rate from the ice/water tank. Outputs from the steam cycle are the water outlet temperatures from the PBC and main condenser, as well as the cycle efficiency and power output.

Figure 4.

Steam cycle model in OpenModelica

Figure 5 shows the refrigeration cycle model in OpenModelica. As with the steam cycle, the refrigeration cycle model is a simplified version of the real-life system. The main inputs for the cycle are the water temperature and mass flow rate to the condenser from the cooling tower, the ice water temperature and mass flow rate from the tank and the power available to run the cycle. The outputs from the cycle are the water temperature going back to the cooling tower and the amount/fraction of ice produced going into the tank. The equations used for modeling the components, along with assumptions and simplifications, and the logic used for the controllers are described in the following sections.

Figure 5.

Refrigeration cycle model in OpenModelica

Component costing models

Cost models were created for the different parts of the system in the RAVEN plugin TEAL and are broken down into two main parts, capital costs and recurring costs. Capital costs include the initial purchasing price for the component or system. Recurring costs include the costs for operation and maintenance, as well as revenue generated by producing things such as clean water or electrical power. The following general equations show how the capital cost and recurring cost/revenue were calculated using TEAL.

where is a multiple of the number of components/systems, is the reference size of the component/system, is the driver size of the component/system, is the cost for the reference size, is the scaling factor and is the sum of the recurring yearly costs/revenues.

Steam cycle cost model

The capital cost for the steam cycle was based on an article on the cost for the NuScaleSMR (Black et al., 2019, pp. 348–258). In the article, it gives an estimate for the cost of a NuScaleSMR as $3465.72 per Kilowatt. Using this information and the expected size of the SMR to be 60 MW, the capital cost for one SMR, which includes the primary side reactor system and the secondary side energy conversion system (e.g., turbine, condenser, pump and cooling tower), is modeled to be a little under $210 million. A report from 2017 titled “The Economics of Small Modular Reactors” was the basis for calculating the recurring costs from operation and maintenance (The Economics of Small Modular Reactors, 2017). It gives estimates for the fixed ($135/kW-yr) and variable ($3/MWh) O&M, as well as an estimate for the cost of fuel ($8.5/MWh), with the fuel disposal cost included.

Refrigeration cycle cost model

The capital cost of the refrigeration cycle is mostly made up of the cost of the compressor. To estimate the cost of the compressor for a given size, an article on compressor installation prices was used as a basis (Almasi, 2014). The capital cost for a 10 MW compressor is modeled to cost $6 million and the cost is projected to increase as the size of the compressor increases, with a scaling factor of 0.5. The yearly O&M costs for the refrigeration cycle are based on the size of the compressor. It is modeled to increase linearly as the compressor size increases, with a 10 MW compressor requiring $10 million for O&M annually.

Ice/water tanks cost model

The capital cost of the water tanks was based on an article about the cost of water storage tanks [38]. The model predicts that a 1.5-million-gallon tank would cost $3 million and that the price increases as the tank size increases with a scale factor of 0.5. The O&M for the tank is lumped in with the revenue generated for clean water, so that approximately each gallon generates about half a penny of revenue.

Wind turbine cost model

The capital cost of each 2 MW wind turbine was modeled to be about $2 million, assuming some government incentive, and an article on O&M costs for wind turbines was the basis for an estimation for the annual cost to be about $90,000 (US wind O&M costs estimated at $48,000/MW; Falling costs create new industrial uses: IEA, 2017).

Reverse osmosis system cost model

Cost models for RO systems can be very complex and involve a lot of things to consider, such as the costs involved with intake and discharge of water, pre-treatment of water, as well as the construction costs and power costs to run the system (Seawater Desalination Power Consumption, 2011). The cost model used for the RO system lumps together the capital costs and operating costs into one large single cost, which is based on the levelized cost of water. The overall cost for a 15 MW system with a 20-year lifespan was set at $225 million and increases with a scale factor of 0.5 as the size of the RO system increases.

Electrical power revenue/penalty cost model

During peak hours the rate for electricity was $0.22 per kWh and during off peak hours the rate was $0.07 per kWh (Utah Rates and Tariffs, 2019). To calculate the penalty cost for over-producing or not meeting the power demand, a quadratic cost function was used. The following equation helps describe the cost function.

is the sum of the costs, is the current rate for electricity, is the power produced and is the predicted power production. This approach to calculating the penalty was selected so that the cost would be symmetric about the demand and increase greatly the farther the system was from meeting the demand. This helped to ensure that the system would be better fit to meet the power demand.

Net present value calculation

The Net Present Value (NPV) for the NHES was calculated by using the RAVEN plugin TEAL (TEAL, 2021). Using the economic models for the different components/systems listed, TEAL can calculate the NPV at the end of the system’s life cycle. The life span for most of the components was set to 40 years, with the refrigeration cycle and RO system having an expected life span of only 20 years before being replaced.

The systems were evaluated using OpenModelicav1.14.1 (64-bit) with OMSimulatorv2.1.0. RAVEN v. 2.0 was used to run multiple cases for each of the systems to find the optimal system sizing for highest net present value.

Optimization process

Five design parameters have been identified for the FD system as they are associated with the size of its key subsystems, including 1) number of SMRs; 2) number of wind turbines; 3) size of the compressor for the refrigeration cycle; 4) size of the ice storage tanks; 5) size of the power boosting condenser. For the RO system, in addition to the number of SMRs and number of wind turbines, the size of the RO system is included as one of the three design parameters for the optimization.

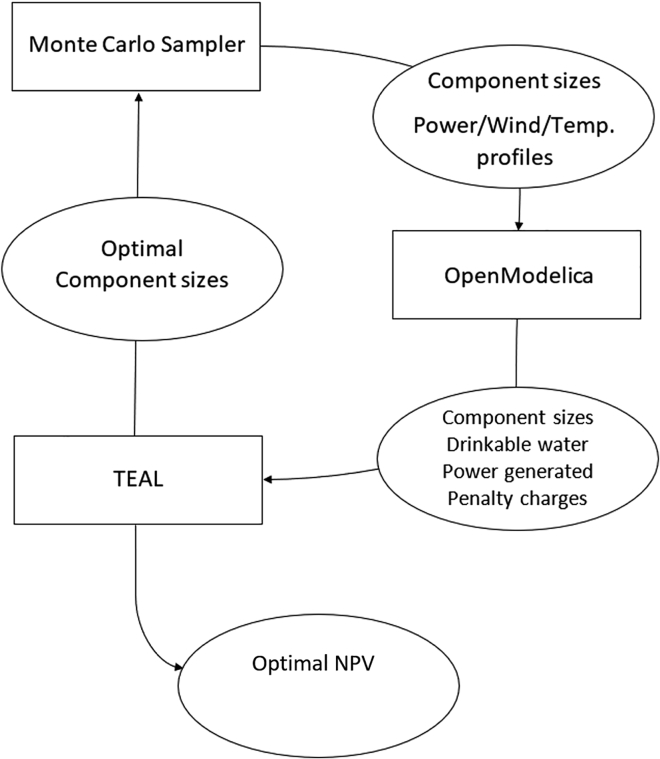

The optimization process to find the optimal sizing of the system to meet the power demand with the highest NPV is shown in Figure 6. It is broken down into two main parts. The first part is when the Monte Carlo sampler is run in RAVEN to explore the design space for the design parameters of each system. The sampler runs multiple cases of the OpenModelica model, changing the following variables (depending on the system): (1) Number of SMRs; (2) number of wind turbines; (3) size of the compressor for the refrigeration cycle; (4) size of the tanks; (5) size of the power boosting condenser; and (6) size of the RO system. It produces the following outputs, which will be used in the second part: (1) The component sizes for the simulation; (2) the amount of drinkable water produced; (3) the amount of power generated; and (4) the penalty charges. The second part of the optimization process uses the outputs from the sampled simulations to perform an economic analysis using TEAL. TEAL then calculates the net present value (NPV) for the sampled systems. These results are used to refine the sampling space. This process will be repeated multiple times to reach an optimal system sizing. Then the NPV of the optimized system can be computed. The optimized systems using reverse osmosis and freeze desalination can then be compared and the best system for the given inputs can be determined.

Figure 6.

Optimization workflow

Results

This section discusses the results from optimizing both OpenModelica models, the Freeze Desalination (FD) system and the Reverse Osmosis (RO) system for two locations. The locations chosen were Salt Lake City, UT and San Diego, CA.

Case study one: Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City was chosen as it has a lower fresh water supply and to see how each system would meet the demands of a hot summer day. The population estimate used to estimate the power demand (1.16 million) came from the United States Census Bureau data for Salt Lake County (QuickFacts United States, 2021).

Input profiles

Figure 7 shows the input profiles (power demand, air temperature and wind speed) used to run the models. The data was taken from a hot summer day in July as it represents typical variable load and relatively high power demand in the afternoon.

Figure 7.

Input profiles for Salt Lake City

(A) Power demand (W).

(B) Temperature (C).

(C) Wind speed (m/s).

The power demand data for Salt Lake City came from the US Energy Information Administration (Hourly Electric Grid Monitor, 2019). A plot of its profile for the given day is shown in Figure 7A. The data for the air temperature came from Weather Underground (Weather History, 2021). It has records of hourly data for air temperature. Figure 7B shows the air temperature profile for the chosen summer day in Salt Lake City. The data for the wind speed came from a wind farm outside of Salt Lake City, in Milford, UT. This location was chosen as it was near Salt Lake and is a windy location where wind turbines would realistically be located. The data came from the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory wind prospector tool (Wind Prospector, 2020). Data was not available for the year 2019 (from which the power demand and air temperatures come), so the data was taken from the same day in 2012 instead. Figure 7C shows the wind speed profile for the summer day.

Optimization process

To get a good estimate of the sizing search space to use for the number of SMRs, the OpenModelica model was run a few times with the number of SMRs varied until the power generation was close to the power demand. Then a Monte Carlo analysis was performed with a relatively large sample space. The performance of each of the runs was ranked by NPV and the sizing of the best runs was used to narrow the search space for a second Monte Carlo analysis. This process was repeated with the search space decreasing for each iteration until the optimal solution was found.

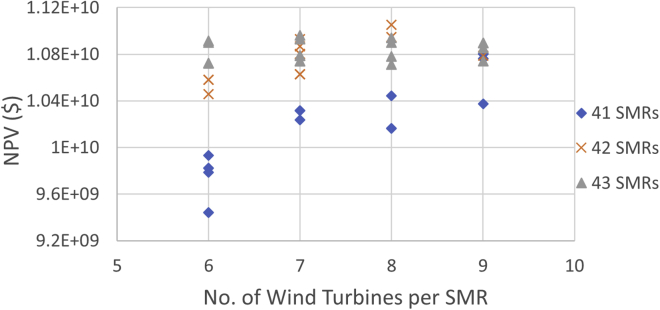

Freeze desalination system

The optimal solution for the Freeze Desalination system had the following inputs: 42 SMRs, 84 wind turbines, 20 MW compressor, 1.8 million-gallon tanks, and a max flow rate for the power boosting condenser of 1400 kg/s. The calculated net present value (NPV) for this case was $1.51e10 after 40 years. Figure 8 shows the results of the optimization process. Each symbol represents a potential system design. As shown, designs with 42 SMRs and 2 wind turbines per SMR give relatively higher NPV.

Figure 8.

Fdoptimization results

Figures 9 and 10 show how the FD system operates for the optimal case. Figure 9 shows how the system meets the power demand, with the power also being broken down into two types, power from the SMRs and power from the wind turbines. Notice how the system meets or exceeds the power demand from hours 0–19 and 22–24. Figure 10A shows the power available for the compressor to run the refrigeration cycle. From about hours 3–5 the power available is a little more than the 20 MW size of the compressor. From about hours 13–22 the compressor is turned off as there is no excess power to run the refrigeration cycle. Figure 10B display the percent of ice in the tank throughout the day. The ice percentage builds up to about 75% by hour 13 and then decreases to zero a little after hour 19 as the ice is used up in order to boost power output through the power-boosting condenser. Figure 10C shows the efficiency of the steam cycle and how the use of the power boosting condenser from hours 13–22 improves it. Notice how the efficiency is boosted when the PBC is turned on at hour 13, with the boosting decreasing from hours 19–22 as the tank runs out of ice. Figure 10D shows the accumulation of penalty energy throughout the day. Notice that there is a penalty from hours 3–5 when the system is producing more power than the compressor can use for the refrigeration cycle. Also, from hours 19–22 there is more significant penalty when the system does not meet the power demand.

Figure 9.

Power generation of SLCFDsystem

Figure 10.

Results from freeze desalination system in Salt Lake City

(A) Power for Refrigeration Cycle.

(B) Ice in tank.

(C) Efficiency of steam cycle.

(D) Penalty energy throughout the day.

Figure 11 shows the temperature of the waters in the power boosting condenser. Although the outlet temperature of the water from the tank is always set to 1° below the inlet temperature of the water from the cooling tower, the mass flow of the water from the tank is effectively zero from hours 0–13 as power boosting is not needed and 22–24 as the stored latent heat in the ice/water tanks is depleted. This can be inferred as the temperature difference between the inlet and outlet water from the cooling tower is zero over the same time period.

Figure 11.

Slcpower boosting condenser water temperatures

Reverse osmosis system

The optimal solution for the reverse osmosis system had the following inputs: 42 SMRs, 336 wind turbines, and an RO system with a max power input of 19 MW. The NPV for the optimal case was $1.12e10 after 40 years Figure 12 shows the optimization results. As shown, designs with 42 SMRs and 8 wind turbines per SMR give relatively higher NPV.

Figure 12.

Rooptimization results

Figures 13 and 14 show how the RO system operates for the optimal case. Figure 13 shows how the system meets the power demand. Notice that the system oscillates around the power demand during the peak hours from 15–21 as the wind turbines' power output fluctuates more, which requires the larger number of wind turbines. Figure 14A shows how much power is available to run the reverse osmosis process. Notice that from hours 2.5–5.5 there is excess power that can’t be used by the 19 MW RO system. Figure 14B shows the amount of clean water that has been generated throughout the day by the RO process. Most of the water is generated in the first 12 h. The amount of penalty energy incurred by the system throughout the day is shown in Figure 14C. Notice the penalty from over-production from hours 2.5–5.5 and then penalties from underproduction for the rest of the day.

Figure 13.

Power generation of SLCROsystem

Figure 14.

Results from the optimal reverse osmosis system in salt lake city

(A) Power available to RO.

(B) Clean water generated throughout the day.

(C) Penalty Energy.

Case study two: San Diego

San Diego was chosen as it currently has the largest desalination plant (using RO) in the US. Also, San Diego, and CA in general, consistently experience droughts and have high demand for fresh water.

Input profiles

The following figure shows the input profiles (Power Demand, Air Temperature and Wind Speed) used to run the models. The data again was taken from a hot summer day. The day was chosen as it had a relatively high power demand for the given season. The power demand data for San Diego also came from the US Energy Information Administration (Hourly Electric Grid Monitor, 2019). Power demand data for San Diego was created by using the power demand for CA for the given days and scaling it to the number of households in San Diego. The power demand for San Diego for the given summer day is shown in Figure 15A. The data for the air temperature came from Weather Underground. Figure 15B shows the air temperature profiles for the chosen summer day in San Diego. The data for the wind speed came from a wind farm outside of San Diego, in Boulevard, CA. This location was chosen as it was near San Diego and a windy location where wind turbines would realistically be located. The data also came from the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory wind prospector tool. Again, the data was not available for the year 2019 (from which the power demand and air temperatures come), so the data was taken from the same days in 2012. Figure 15C shows the wind speed profiles for the given summer day.

Figure 15.

Input profiles for San Diego

(A) Power demand.

(B) Temperature.

(C) Wind speed.

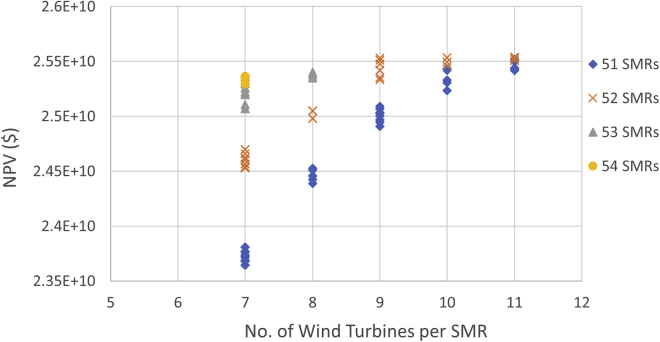

Freeze desalination system

The optimal solution for the Freeze Desalination system had the following inputs: 52 SMRs, 520 wind turbines, 16 MW compressor, 2 million-gallon tanks, and a max flow rate for the power boosting condenser of 1000 kg/s. The calculated net present value (NPV) for this case was $2.67e10 after 40 years. Figure 16 shows the results of the optimization process. Figures 17 and 18 show how the FD system operates for the optimal case. Figure 17 shows how the system meets the power demand, with the power also being broken down into two types, power from the SMRs and power from the wind turbines. Notice how the system meets or exceeds the power demand from approximately hours 0–17.5 and 21.5–24.

Figure 16.

Fdoptimization results after sixth iteration

Figure 17.

Power generation of SDFDsystem

Figure 18.

Results from freeze desalination system in San Diego

(A) Power for Refrigeration Cycle.

(B) Ice in tank.

(C) Efficiency of steam cycle.

(D) Penalty energy throughout the day.

Figure 18A shows the power available for the compressor to run the refrigeration cycle. From about hours 11–14 and 17–22 the compressor is turned off as there is no excess power to run the refrigeration cycle. For the last hour of the day the power available is more than the 16 MW size of the compressor. Figure 18B show the percent of ice in the tank. The ice percentage reaches a maximum of about 29% by hour 11 and then decreases to zero by hour 19. Figure 18C shows the efficiency of the steam cycle and how it is boosted by the power boosting condenser. Notice how the boosting decreases from hours 17.5–22 as the tank ran out of ice. Figure 18D shows the accumulation of penalty energy throughout the day. Notice that most of the penalty is from hours 18–21 when the system does not meet the power demand. There is also a little penalty during the last hour when too much power is generated. Figure 19 shows the temperatures of the waters in the power boosting condenser. Notice how the temperature of the water at the outlet to the steam condenser decreases from the inlet from the cooling tower when the power boosting condenser is on.

Figure 19.

Sdpower boosting condenser water temperatures

Reverse osmosis system

The optimal solution for the reverse osmosis system had the following inputs: 52 SMRs, 780 wind turbines, and an RO system with a max power input of 15 MW. The NPV for the optimal case was $2.33e10 after 40 years Figure 20 shows the results of the optimization process. Figures 21 and 22 show how the RO system operates for the optimal case. Figure 21 shows how the system meets the power demand. Notice that the system is able to meet the demand for the first 17.5 h as the wind turbines' power output matches the demand fairly well. Figure 22A shows how much power is available to run the reverse osmosis process. Notice that the RO system is turned off from hours 17.5–21.5. Figure 22B is an integration of the clean water generated throughout the day. Notice that a lot of the water is generated in the first 10 h, with some more water generated from hours 14–17 by increased power production from the wind turbines. There is also a rise in water production near the end of the day when the power demand falls. Figure 22C shows the integration of the amount of penalty energy incurred by the system throughout the day. The penalty from hours 18–21 is because of not meeting the power demand. The penalty from hours 22.5–24 is because of excess power exceeding the size of the 15 MW RO system.

Figure 20.

SdROoptimization results after fifth iteration

Figure 21.

Power generation of SDROsystem

Figure 22.

Results from the optimal reverse osmosis system in San Diego

(A) Power available to RO.

(B) Clean water generated throughout the day.

(C) Penalty Energy.

Discussion

This section provides some discussions and explanation of the results shown in the previous section. A sensitivity analysis of relevant system variables was conducted first, which was then followed by analyzing the results for both the FD and RO systems and what make one system better suited than the other.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed using the data for Salt Lake City. The variables that were used in the sensitivity analysis were: SMR number, wind turbine number, tank size, compressor size, PBC max size, RO size, steam heat transfer coefficient in main condenser, the turbine isentropic efficiency and the price of energy during peak hours. To calculate the sensitivity of each variable, the system was first run at the optimal solution (i.e. for FD system: 42 SMRs, 2 wind turbines per SMR, 1.8 million gallon tank, 20 MW compressor, 1,400 kg/s max flow for PBC, 5000 W/(m2K) steam heat transfer coefficient, 0.85 isentropic efficiency of turbine and $0.22/kWh for electricity during peak hours). Then each individual variable was varied by 2.5%, first by increasing, then by decreasing the variable. The NPV for each case was calculated and the variation from the optimal solution was calculated as shown in the following equation:

The sensitivity of each variable was then calculated by taken the average of the absolute value of the two NPV variations. The results of the sensitivity analysis are shown in Figure 23. It shows that the NPV calculation is most sensitive to a change in the turbine isentropic efficiency. A 2.5% change in the value of the isentropic efficiency of the turbine resulted in about a 4.5% change in the NPV as compared to the optimal solution. This impact is so large as it affects the overall efficiency of the steam cycle for its entire life cycle. The next closest variable was the SMR, which changed the NPV by a little less than 2%. This impact is lower as it mostly affects the capital cost. The only other variable that was able to change the NPV by more than 1% was the RO size. The remaining variables had minimum change on the NPV. This shows how important it is to have a good estimate of the turbine performance.

Figure 23.

Sensitivity of NPV to 2.5% input variable changes

Case studies (Salt Lake City and San Diego)

For Salt Lake City, the optimal FD system resulted in a higher NPV ($1.51e10) than the optimal RO system ($1.12e10). The FD system is also able to meet the power demand with a lower amount of penalty energy. However, the amount of clean water generated by the RO system was about six times larger than the FD system (i.e., 1.3 million m3 vs. 215,000 m3). In order for the NPV of the RO system to equal the FD system the price of water would need to rise from $1.25 per m3 to $1.55 per m3. Thus, the higher the water price, the more advantageous it is to have the RO system. Nevertheless, the RO system has much higher penalty energy – unmet power demand. To avoid any penalty for unmet power demand using the same set of input variables, the FD system would need one more SMR (i.e., 43 SMRs) and two more wind turbines (i.e., 86 wind turbines). The NPV for this case is reduce slightly to $1.49e10. However, if the penalty for unmet power were substantially higher than the penalty function used in this study, this system configuration could be more desirable.

Similarly, for San Diego, the study has shown the optimal FD system resulted in a higher NPV ($2.67e10) than the optimal RO system ($2.33e10). In this case, the RO system did a better job in meeting the power demand with a lower amount of penalty energy. The amount of clean water generated by the RO system was about twelve times larger than the FD system (about 1.37 million m3 to about 113,500 m3), which could be more advantageous given San Diego’s need for a large amount of clean water. In order for the NPV of the RO system to equal the FD system, the price of water would need to rise from $1.25 per m3 to $1.52 per m3. In performing the same hypothetical case without penalty energy, the FD system now requires 55 SMRs (increased from 52 of the optimal case) and 555 wind turbines (increased from 520 of the optimal case). The NPV for this case was also slightly lowered to be 2.63e10. Although this system would have a larger initial capital cost and a lower NPV based on the penalty function used, this system would be more advantageous if the penalty for not meeting the power demand were increased.

One possible way to find a more optimal solution would be to uncouple the number of wind turbines with the number of SMRs. For simplicity, the number of wind turbines was linked with the number of SMRs. This made it difficult to refine the number of wind turbines when there were a large number of SMRs. It was also noted that the NPV would continue to increase with an increasing max size of the power-boosting condenser (PBC). One reason for this is that the cost of the PBC was assumed to be small in relation to the other component costs. Thus, setting the limit of the PBC size in this study may have impeded the FD system potential.

Based on this study, both the cost of water and cost of the penalty energy play important roles in deciding which system is more economically viable. As the cost of water increases, the value of the RO system rises as it produces more clean water. As the cost of the penalty energy increases, the FD system would be preferred. It is also important to note that the economic models used in this study are rather simplified. Thus, more detailed cost models for the key system components would more accurately reflect the costs of real-life systems.

Conclusion

This article provided an analysis of the fit of two types of nuclear hybrid energy systems (NHES) for delivering clean energy and water. Both systems couple small modular reactors (SMR) with wind turbines to provide clean power and drive either a freeze desalination (FD) or a reverse osmosis (RO) system for clean water. The FD system was able to boost power production of the SMR using the produced ice, whereas the RO system was able to generate more clean water with the requirement of more wind turbines to better meet the power demand.

Both systems were modeled in OpenModelica leveraging various component models in its libraries. System optimization and NPV analysis were performed using RAVEN and its plugin TEAL. RAVEN performs Monte Carlo analyses over the sample space of each design variable to find the optimal component sizes for each system. A quadratic penalty cost function was used for unmet power and excess power to help with finding the optimal system size.

Based on the two case studies using Salt Lake City and San Diego, the results reveal that the FD system can better meet the power demand, thus less penalty energy. This is attributed to the power-boosting capability of the freeze desalination system. During the peak hours of power demand, the FD system increases its power production by about 12% by operating the steam cycle more efficiently. According to the economic figures, as long as the water price is below $1.50/m3, it is more economic for the FD system. Thus, when water price rises above $1.50/m3, the RO system could be more advantageous as it generates substantially more clean water. Although the aforementioned general findings are likely held for other similar cities, the optimal design of each system (FD or RO) can change from location to location based on the respective input datasets (demand, costs of energy and water).

Limitations of the study

Like any system design optimization, the results are largely based on the design inputs. This work is no difference. Although the study covers two locations to assess the two optimal NHES designs in providing clean energy and water, its findings are largely dependent on the input datasets. Specially, the energy demand and weather data collected. In order to have more robust design comparison and optimization, synthetic time-series datasets generated from reliable data sources would be one of the focuses of the work going forward.

Nomenclature

- Acronyms

- CCPP Combined cycle power plant

- CDI Capacitive deionization

- FD Freeze desalination

- FO Forward osmosis

- GWe Gigawatt electrical

- GWth Gigawatt thermal

- HES Hybrid energy system

- IRR Internal rate of return

- MD Membrane distillation

- NHES Nuclear hybrid energy system

- NPV Net present value

- PI Profitability index

- PBC Power boosting condenser

- SD San Diego

- SLC Salt Lake City

- SMR Small modular reactor

- RAVEN Risk analysis and virtual environment

- RO Reverse osmosis

- TEAL Tool for economic analysis

- Variables

- Cost for the reference size

- Driver size of the component/system

- N Multiple number

- Reference size of the component/system

- Scaling factor

- Sum

- Total power produced by system [W]

- Expected total power production by system [W]

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Deposited data | ||

| The Wind Prospector | National Renewable Energy Laboratory | https://maps.nrel.gov/wind-prospector/?aL=0&bL=clight&cE=0&lR=0&mC=40.21244%2C-91.625976&zL=4 |

| Weather Underground | The Weather Company, IBM | https://www.wunderground.com/history/daily/us/ca/san-diego/KSAN |

| Hourly Electric Grid Monitor | US Energy Information Administration | https://www.eia.gov/electricity/gridmonitor/dashboard/electric_overview/US48/US48 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| OpenModelica | Open Source Modelica Consortium | https://www.openmodelica.org/ |

| RAVEN (TEAL) | Idaho National Laboratory | https://github.com/idaholab/TEAL#readme |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Hailei Wang (hailei.wang@usu.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not use or generate any materials.

Experimental model and subject details

This study does not use experimental models.

Method details

OpenModelica has also been chosen as the dynamic modeling tool to simulate the processes of the two NHES systems. The OpenModelica models leverage some of the components already developed in the open-sourced Modelica libraries and ThermoPower library.

Cost models for the key components were created using the RAVEN plugin TEAL. The costs are broken down into two main parts, capital costs and recurring costs. Capital costs include the initial purchasing price for the component or system. Recurring costs include the costs for operation and maintenance, as well as revenue generated by producing things such as clean water or electrical power. To calculate the penalty cost for over-producing or not meeting the power demand, a quadratic cost function was used.

The optimization process to find the optimal sizing of the system to meet the power demand with the highest NPV can be broken down into two main parts. The first part uses the Monte Carlo sampler in RAVEN to explore the design space for the design parameters of each system. The sampler runs multiple cases of the OpenModelica model, changing the following variables: (1) Number of SMRs; (2) number of wind turbines; (3) size of the compressor for the refrigeration cycle; (4) size of the tanks; (5) size of the power boosting condenser; and (6) size of the RO system. The following outputs: (1) the component sizes for the simulation; (2) the amount of drinkable water produced; (3) the amount of power generated; and (4) the penalty charges will be fed into the second part of the optimization process to perform an economic analysis using TEAL. TEAL then calculates the net present value (NPV) for the sampled systems. These results are used to refine the sampling space. This process will be repeated multiple times to reach an optimal system sizing. Then the NPV of the optimized system can be computed. The optimized systems using reverse osmosis and freeze desalination can then be compared and the best system for the given inputs can be determined.

Quantification and statistical analysis

This study does not include statistical analysis or quantification.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the financial support provided by Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) through the Award No. 31310019M0014.

Author contributions

SH: Modeling, software, manuscript preparation. SD: RO system modeling, manuscript preparation, editing. HW: System concepts and designs, model and result discussions, manuscript review and editing.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: April 15, 2022

Data and code availability

-

•

This paper analyzes existing, publicly available data. These accession numbers for the datasets are listed in the key resources table.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- Akesson J., Arzen K.-E., Gafvert M., Bergdahl T., Tummescheit H. Modeling and optimization with optimica and JModelica.org–languages and tools for solving large-scale dynamic optimization problems. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2010;34:1737–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.compchemeng.2009.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almasi A. How much will your compressor installation cost? 2014. https://www.chemicalprocessing.com/articles/2014/how-much-will-your-compressor-installation-cost/ Retrieved from chemical processing.

- Bandar K.B., Alsubei M.D., Aljlil S.A., Darwish N.B., Hilal N. Membrane distillation process application using a novel ceramic membrane for brackish water desalination. Desalination. 2021;500 doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2020.114906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benato A., Bracco S., Stoppato A., Mirandola A. Dynamic simulation of combined cycle power plant cycling in the electricity market. Energ. Convers. Manag. 2016;107:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2015.07.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black G.A., Aydogan F., Koerner C.L. Economic viability of light water small modular nuclear reactors: general methodology and vendor data. Renew. Sustain.Energy Rev. 2019;103:248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2018.12.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bragg-Sitton S.M. Second Edition. Woodhead Publishing; 2021. Hybrid Energy Systems Using Small Modular Nuclear Reactors (SMRs). Handbook of Small Modular Nuclear Reactors; pp. 323–356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cafferkey N., Provan G. An analysis of performance-critical properties of modelica models. IFACPapers Online. 2015;48:210–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ifacol.2015.05.122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casella F., Colonna P. Dynamic modeling of IGCC power plants. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2012;35:91–111. doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2011.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casella F., Pretolani F. Fast start-up of a combined-cycle power plant: a simulation study with Modelica. Modelica Conference. 2006;4:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Casella F., Donida F., Akesson J. Object-oriented modeling and optimal control: a case study in power plant start-up. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2011;44:9549–9554. doi: 10.3182/20110828-6-IT-1002.03229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Martino M., Avraamindou S., Cook J., Pistikopoulos E.N. An optimization framework for the design of reverse osmosis desalination plants under food-energy-water nexus considerations. Desalination. 2011;503 doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2021.114937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duman A.C., Guler O. Techno-economic analysis of off-grid PV/wind/fuel cell hybrid system combinations with a comparison of regularly and seasonally occupied households. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018;42:107–126. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2018.06.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gharibi M., Askarzadeh A. Size and power exchange optimization of a grid-connected diesel generator-photovoltaic-fuel cell hybrid energy system considering reliability, cost and renewability. Int. J. Hydro.Energy. 2019;44:25428–25441. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hills S., Dana S., Wang H. Modeling and simulation of nuclear hybrid energy systems using OpenModelica. Energy. Convers. Manag. 2021;247 doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2021.114724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hourly Electric Grid Monitor (2019). Retrieved from U.S. Energy Information Administration: https://www.eia.gov/electricity/gridmonitor/dashboard/electric_overview/US48/US48

- IEA . IEA; 2017. US Wind O&M Costs Estimated at $48,000/MW; Falling Costs Create New Industrial Uses. Retrieved from Reuters Events Renewables: https://www.reutersevents.com/renewables/wind-energy-update/us-wind-om-costs-estimated-48000mw-falling-costs-create-new-industrial-uses-iea. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Albertus B. Confronting the duck curve: how to address over-generation of solar energy. 2017. https://www.energy.gov/eere/articles/confronting-duck-curve-how-address-over-generation-solar-energy Retrieved from Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy.

- Liu M., He Q., Guo Z., Zhang K., Yu S., Gao C. Composite reverse osmosis membrane with a selective separation layer of double-layer structure for enhanced desalination, anti-fouling and durability properties. Desalination. 2021;499 doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2020.114838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narcisi V., Lorusso P., Giannetti F., Alfonsi A., Caruso G. Uncertainty quantification method for RELAP5-3D using RAVEN and application on NACIE experiments. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 2019;127:419–432. doi: 10.1016/j.anucene.2018.12.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okampo E.J., Nwulu N. Optimisation of renewable energy powered reverse osmosis desalination systems: a state-of-the-art review. Renew. Sustain.Energy Rev. 2021;140 doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2021.110712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowski S., Huertas R.M., Galinha C.F., Crespo J.G., Velizarov S. On operation of reverse electrodialysis (red) and membrane capacitive deionisation (MCDI) with natural saline streams: a critical review. Desalination. 2020;476 doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2019.114183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky R., Sabharwall P., Hartvigsen J., O'Brien J. Comparative review of hydrogen production technologies for nuclear hybrid energy systems. Prog. Nucl. Energy. 2020;123 doi: 10.1016/j.pnucene.2020.103317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quickfacts United States 2021. Retrieved from United States Census Bureau: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219.

- Rouxelin P., Alfonsi A., Ivanov K., Strydom G. Energy group search engine based on surrogate models constructed with the RAVEN/NEWT/PHISICS sequence. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2020;356 doi: 10.1016/j.nucengdes.2019.110356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu P., Krishnaswamy S., Pande N.K. Process intensification using a novel continuous U-shaped crystallizer for freeze desalination. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2020;153 doi: 10.1016/j.cep.2020.107970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanajaoba S. Optimal sizing of off-grid hybrid energy system based on minimum cost of energy and reliability criteria using firefly algorithm. Sol. Energy. 2019;188:655–666. doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2019.06.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seawater Desalination Power Consumption 2011. Retrieved from WateReuse Association: https://watereuse.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Power_consumption_white_paper.pdf.

- Shi Y., Liang B., Hartel R.W. ACS SymposiumSeries. Vol. 438. ACS Publications; 1990. Crystallization of ice from aqueous solutions in suspension crystallizers; pp. 316–328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H., Kalista B., Jeong S., Jang A. Optimization of simplified freeze desalination with surface scrape freeze crystallizer for producing irrigation water without seeding. Desalination. 2019;452:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2018.08.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shitahun A., Ruge V., Gebremedhin M., Bachmann B., Eriksson L., Andersson J., Fritzson P. Model-based dynamic optimization with OpenModelica and CasADi. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2013;46:446–451. doi: 10.3182/20130904-4-JP-2042.00166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skuse C., Gallego-Schmid A., Azapagic A., Gorgojo P. An emerging membrane-based desalination technologies replace reverse osmosis? Desalination. 2021;500 doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2020.114844. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suman S. Hybrid nuclear-renewable energy systems: a review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;181:166–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taghizadeh M., Bahramara S., Adabi F., Nojavan S. Optimal thermal and electrical operation of the hybrid energy system using interval optimization approach. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020;169 doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.114993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- TEAL 2021. https://github.com/idaholab/TEAL#readme Retrieved from GitHub.

- The Economics of Small Modular Reactors 2017. Retrieved from SMR Start: https://smrstart.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/SMR-Start-Economic-Analysis-APPROVED-2017-09-14.pdf.

- Tica A., Gueguen H., Dumur D., Faille D., Davelaar F. Design of a combined cycle power plant model for optimization. Appl. Energy. 2012;98:256–265. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2012.03.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Utah Rates and Tariffs. Retrieved from Rocky Mountain Power (2019): https://www.rockymountainpower.net/about/rates-regulation/utah-rates-tariffs.html

- Vatanpour V., Zoqi N. Surface modification of commercial seawater reverse osmosis membranes by grafting of hydrophilic monomer blended with carboxylatedmultiwalled carbon nanotubes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;396:1478–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.11.195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Yin J., Lin J., Chen Z., Hu P. Design and economic analysis of a novel hybrid nuclear-solar complementary power system for power generation and desalination. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021;187 doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2021.116564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson W.J. IEEE International Conference on Opportunities andAdvances in International Electric Power Generation. 1996. The ‘success’ of the combined cycle gas turbine; pp. 87–92. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weather History 2021. Retrieved from Weather Underground: https://www.wunderground.com/history/daily/us/ca/san-diego/KSAN.

- Wind Prospector 2020. Retrieved from National Renewable Energy Laboratory: https://maps.nrel.gov/wind-prospector/?aL=0&bL=clight&cE=0&lR=0&mC=40.21244%2C-91.625976&zL=4.

- Xie C., Zhang L., Liu Y., Lv Q., Ruan G., Hosseini S.S. A direct contact type ice generator for seawater freezing desalination using LNG cold energy. Desalination. 2018;435:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2017.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Liu Y. Integrated forward osmosis-absorption process for strontium-containing water treatment: pre-concentration and solidification. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021;414 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

-

•

This paper analyzes existing, publicly available data. These accession numbers for the datasets are listed in the key resources table.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.