Abstract

Background

Goal setting is considered a key component of rehabilitation for adults with acquired disability, yet there is little consensus regarding the best strategies for undertaking goal setting and in which clinical contexts. It has also been unclear what effect, if any, goal setting has on health outcomes after rehabilitation.

Objectives

To assess the effects of goal setting and strategies to enhance the pursuit of goals (i.e. how goals and progress towards goals are communicated, used, or shared) on improving health outcomes in adults with acquired disability participating in rehabilitation.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, four other databases and three trials registers to December 2013, together with reference checking, citation searching and contact with study authors to identify additional studies. We did not impose any language or date restrictions.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cluster‐RCTs and quasi‐RCTs evaluating the effects of goal setting or strategies to enhance goal pursuit in the context of adult rehabilitation for acquired disability.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently reviewed search results for inclusion. Grey literature searches were conducted and reviewed by a single author. Two authors independently extracted data and assessed risk of bias for included studies. We contacted study authors for additional information.

Main results

We included 39 studies (27 RCTs, 6 cluster‐RCTs, and 6 quasi‐RCTs) involving 2846 participants in total. Studies ranged widely regarding clinical context and participants' primary health conditions. The most common health conditions included musculoskeletal disorders, brain injury, chronic pain, mental health conditions, and cardiovascular disease.

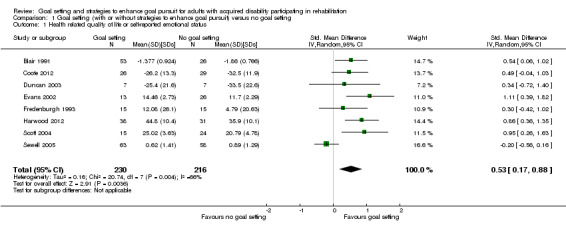

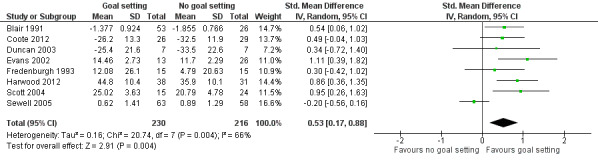

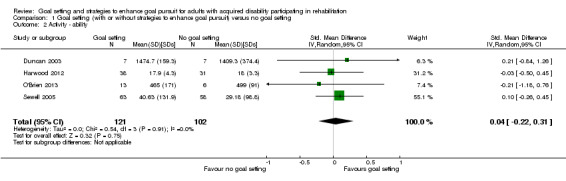

Eighteen studies compared goal setting, with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit, to no goal setting. These studies provide very low quality evidence that including any type of goal setting in the practice of adult rehabilitation is better than no goal setting for health‐related quality of life or self‐reported emotional status (8 studies; 446 participants; standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.53, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.17 to 0.88, indicative of a moderate effect size) and self‐efficacy (3 studies; 108 participants; SMD 1.07, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.49, indicative of a moderate to large effect size). The evidence is inconclusive regarding whether goal setting results in improvements in social participation or activity levels, body structure or function, or levels of patient engagement in the rehabilitation process. Insufficient data are available to determine whether or not goal setting is associated with more or fewer adverse events compared to no goal setting.

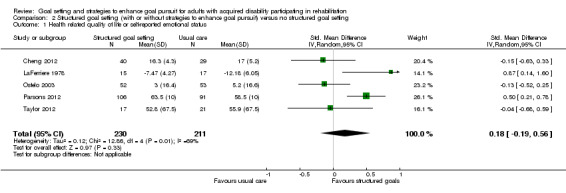

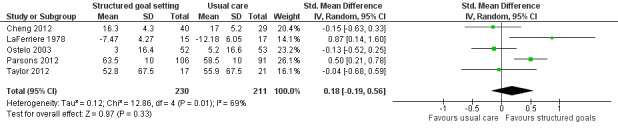

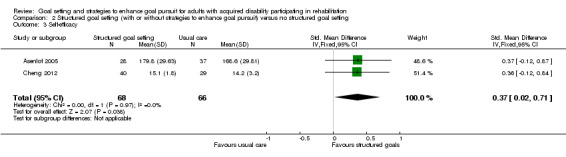

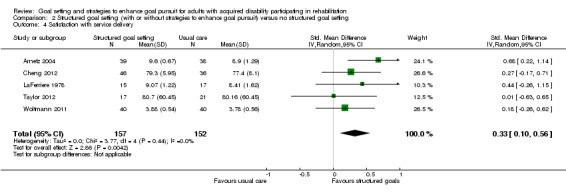

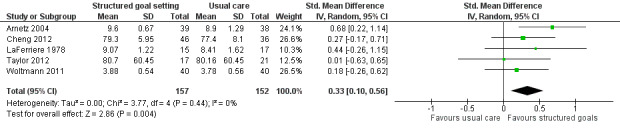

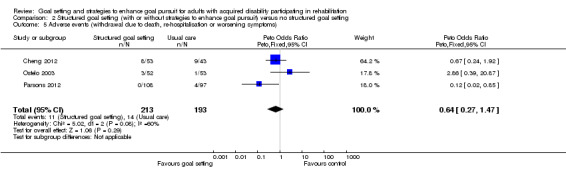

Fourteen studies compared structured goal setting approaches, with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit, to 'usual care' that may have involved some goal setting but where no structured approach was followed. These studies provide very low quality evidence that more structured goal setting results in higher patient self‐efficacy (2 studies; 134 participants; SMD 0.37, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.71, indicative of a small effect size) and low quality evidence for greater satisfaction with service delivery (5 studies; 309 participants; SMD 0.33, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.56, indicative of a small effect size). The evidence was inconclusive regarding whether more structured goal setting approaches result in higher health‐related quality of life or self‐reported emotional status, social participation, activity levels, or improvements in body structure or function. Three studies in this group reported on adverse events (death, re‐hospitalisation, or worsening symptoms), but insufficient data are available to determine whether structured goal setting is associated with more or fewer adverse events than usual care.

A moderate degree of heterogeneity was observed in outcomes across all studies, but an insufficient number of studies was available to permit subgroup analysis to explore the reasons for this heterogeneity. The review also considers studies which investigate the effects of different approaches to enhancing goal pursuit, and studies which investigate different structured goal setting approaches. It also reports on secondary outcomes including goal attainment and healthcare utilisation.

Authors' conclusions

There is some very low quality evidence that goal setting may improve some outcomes for adults receiving rehabilitation for acquired disability. The best of this evidence appears to favour positive effects for psychosocial outcomes (i.e. health‐related quality of life, emotional status, and self‐efficacy) rather than physical ones. Due to study limitations, there is considerable uncertainty regarding these effects however, and further research is highly likely to change reported estimates of effect.

Plain language summary

Goal setting for adults receiving clinical rehabilitation for disability

Background

Goal setting is considered a key part of clinical rehabilitation for adults with disability, such as in rehabilitation following brain injuries, heart or lung diseases, mental health illnesses, or for injuries or illnesses involving bones and muscles. Health professionals use goals to provide targets for themselves and their clients to work towards. In this review we summarise studies that have investigated what effect, if any, goal setting activities have on achieving good health outcomes following rehabilitation.

Results

This review found 39 studies published before December 2013, involving a total of 2846 participants receiving rehabilitation in a variety of countries and clinical situations. The studies used a wide range of different approaches to goal setting and tested the effectiveness of these approaches in a number of different ways. Overall these studies provide very low quality evidence that goal setting helps patients achieve a higher quality of life or sense of well‐being and a higher belief in their own ability to achieve goals that they choose to pursue. There is currently no consistent evidence that goal setting improves people's functional abilities after rehabilitation or how hard they try with therapeutic interventions during rehabilitation.

Insufficient information exists to say whether goal setting increases or reduces the risk of adverse events (such as death or re‐hospitalisation) for people involved in rehabilitation. Because of the variety of approaches to studying goal setting in rehabilitation and because of limitations in the design of many studies completed to date, it is very possible that future studies could change the conclusions of this review. We also need more research to improve our understanding of how components of the goal setting process (such as how difficult goals are, how goals of therapy should be selected and prioritised, how goals are used in clinical practice, and how feedback on progress towards goals should be provided) contribute or do not contribute to better health outcomes.

Summary of findings

Background

Goal setting is considered an essential part of clinical rehabilitation. It has been described as a core practice within rehabilitation (Wade 2009), a requirement for effective interdisciplinary teamwork (Schut 1994), and an activity that specifically characterises both rehabilitation services and those who provide them (Barnes 2000; Scobbie 2009; Wade 1998). In clinical practice there has been growing emphasis on the need for interventions with patients to be goal oriented. Goal terminology is becoming integral to discussions of guidelines, policies and professional requirements at both regional and international levels (e.g. Duncan 2005; Evans 2001; Randall 2000; RCP 2003; RCP 2004; Rothstein 2003).

Some authors have suggested that evidence for the effectiveness of goal setting in improving patient outcomes has already been firmly established, and that this evidence can now direct how goal setting in rehabilitation should be implemented (Black 2010; Marsland 2010; Wilson 2008). However, a systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) concluded that the evidence regarding any generalisable effect of goal setting on patient outcomes following rehabilitation was inconsistent at best, and greatly limited by the quality of studies published at the time (Levack 2006a). Given that this review is now over nine years old, there is a need to update this work.

Description of the condition

This review focuses on the application of goal setting in the context of rehabilitation for adults with acquired disability. The term 'disability' is defined according to the World Health Organization's (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as an 'umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations or participation restrictions' (WHO 2001a, p.3) that result from interactions between a person (with a health condition) and that person's contextual factors (environmental factors and personal factors). For the purposes of this review, the term 'acquired disability' is used to refer more specifically to disability that arises during a person's adult life (i.e. after 16 years of age) following an accident, illness or development of a health condition. This term therefore excludes disability associated with health conditions arising prenatally or in childhood.

Description of the intervention

Reviews of literature on goal setting in rehabilitation are complicated by a number of factors, one of which is the difficulty that exists in describing what might (or might not) constitute 'goal setting' in a rehabilitation context. The terms 'goals', 'goal setting' and 'goal planning' have been used to refer to many different constructs with little current consensus around key terminology (Levack 2006b; Playford 2009). A range of different approaches to goal setting has been described in the literature, with various similarities and differences in the recommended process and content of each. These include (but are not limited to):

Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS) (Kiresuk 1968; Turner‐Stokes 2009);

goal setting based on the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) (Pendleton 2005; Phipps 2007; Trombly 2002; Wressle 2002; Wressle 2003);

'SMART' goal planning (Barnes 2000; Bovend'Eerdt 2009; Mastos 2007; McLellan 1997; Monaghan 2005; Schut 1994);

'RUMBA' goal planning (Barnett 1999);

Self‐Identified Goal Assessment (Melville 2002);

Goal Management Training (Levine 2000);

approaches to goal planning from the Wolfson Neurorehabilitation Centre (McMillan 1999)

contractually‐organised goal setting (Powell 2002);

Collaborative Goal Technology (Clarke 2006);

goal setting as part of the Progressive Goal Attainment Programme (Sullivan 2006);

patient‐centred functional goal planning (Randall 2000); and

goal setting based on the Patient Goal Priority Questionnaire or Patient Goal Priority List (Asenlöf 2009).

Note: 'SMART' and 'RUMBA' are not abbreviations, but mnemonic acronyms for key components of goal setting, promoted by various authors. Interpretations of these acronyms differ (McPherson 2014; Wade 2009). One interpretation of the 'SMART' acronym is that it stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time‐limited goals (Barnes 2000). Similarly, it is suggested that 'RUMBA' refers to Relevant, Understandable, Measurable, Behavioural, and Achievable goals (Barnett 1999).

While these different approaches to goal setting frequently include common features, such as having measurable goals, or patient involvement in goal selection, few such features are universal to all recommended approaches. Indeed, all approaches to goal setting in rehabilitation differ from one another across a number of variables, including:

the group intended to use the approach (i.e. for use by a single, specific profession or for use by an interprofessional team);

the intended patient population for the approach;

the process by which goals are selected (e.g. who is involved; how goals are identified and prioritised);

the recommended characteristics of the actual goals set (i.e. how goals are written; whether they need to be phrased in a certain way);

the recommended content of goals set (i.e. what is considered an acceptable topic for a goal; whether goals need to be set at a particular level of the ICF);

the way the goals are subsequently used in clinical environments (e.g. the way goals are used in team meetings or meetings with patients; how feedback on progress towards goals is presented and used in clinical interactions); and

the intended purpose(s) of setting and having goals.

Even for individually‐named approaches to goal setting, opinions can differ in terms of how each approach should be implemented. For instance, multiple variations on the original GAS approach (Kiresuk 1968) exist, such as: involving greater patient participation in goal selection (Cytrynbaum 1979; LaFerriere 1978; Malec 1999; Turner‐Stokes 2009); having the treating therapist rather than an independent third party select and re‐evaluate the GAS goals (Cytrynbaum 1979; Turner‐Stokes 2009; Willer 1976); using a different number of 'levels' of goal achievement and a different scoring system than was originally proposed (LaFerriere 1978; Turner‐Stokes 2010; Willer 1976), or using standardised rather than individualised wording to indicate the extent of goal achievement (Turner‐Stokes 2009). Similarly, there is no one agreed 'SMART' approach to goal setting; the 'SMART' acronym has been interpreted to refer to a range of goal‐related concepts, and there is no consensus regarding the 'correct' interpretation of this approach (McPherson 2014; Wade 2009).

Goal setting is also often presented as a core component of a whole programme of intervention (e.g. Stuifbergen 2003). However, a systematic review of research into the effectiveness of goal setting needs to be able to separate out the independent effects of goal setting from those of other variables associated with these programmes of intervention (e.g. the amount of therapeutic activity, amount of additional education and information, or other behavioural interventions that are not related to the setting of rehabilitation goals). For more information on the history of goal setting and its application in rehabilitation please refer to Levack 2014a.

Definition of 'rehabilitation goal'

Within the field of psychology there is an enormous body of literature describing and analysing goal constructs from many perspectives. In this context, the term 'goals' has been defined as 'internal representations of desired states, where states are broadly construed as outcomes, events, or processes' (Austin 1996, p.338). This definition allows for goals that are consciously set as well as goals which are not; goals for individuals as well as goals for whole organisations or populations of people; biological goals (such as to change one's body temperature or reproduce); complex cognitive or aesthetic goals (such as to live a moral life or achieve a career objective); goals that relate to a moment in time and goals that relate to a lifespan. From this perspective, all human behaviour is goal directed.

In the context of rehabilitation however, the term 'goal' is generally used to mean something much more specific, and more explicitly linked to clinical work. For the purpose of this review we use the term 'rehabilitation goal' to refer to the concept of a 'goal' set for the purposes of clinical work in rehabilitation, in order to make a clear distinction between this type of goal and colloquial use of the term 'goal' or broader definitions of 'goals' from psychology.

One proposed definition of the term 'rehabilitation goal' has been 'a future state that is desired and/or expected. The state might refer to relative changes or to an absolute achievement. It might refer to matters affecting the patient, the patient's environment, the family or any other party. It is a generic term with no implications about time frame or level' (Wade 1998, p.273). Other authors, focusing on describing an approach to goal setting intended for a particular patient population or for use by one professional group, have been more specific in their definition of goals for rehabilitation. For example, Randall 2000 defined a 'functional goal' within the context of physical therapy as 'the individually meaningful activities that a person cannot perform as a result of an injury, illness, or congenital or acquired condition, but wants to be able to accomplish as a result of physical therapy' (p.1198).

In contrast, many 'goals' in the psychological sense of the word are implicit (i.e. goals which are implied without being directly stated or even necessarily consciously set). For example, the act of reaching for a cup is a motor activity with an implicit goal. Asking a patient to reach for a cup versus reaching into mid‐air is an example of using implicit goals to influence behaviour (Trombly 1999). However, using such activities as a clinical intervention (e.g. for exercise therapy after a stroke) is not an example of 'goal setting' in rehabilitation in its usual sense. While (as stated above) all human behaviour is arguably goal directed and rehabilitation cannot therefore occur without having 'goals' of some kind, it is not true that all goals are 'rehabilitation goals' in the sense usually intended by rehabilitation teams.

Furthermore, the concept of a 'rehabilitation goal' usually refers to a relationship between an individual patient and an individual or group of health professionals (and/or others). This excludes goals set at an organisational level (e.g. in the case of health service management) or community level (e.g. in the case of public health policy) from the definition of 'goal setting' in a rehabilitation context. In other words, while goals such as 'to reduce the incidence of falls in hospital' may be an important key performance indicator for a particular rehabilitation service, these types of organisational goals are not what is usually being discussed in the literature on goal setting in rehabilitation.

Therefore, for the purpose of this review, we define 'rehabilitation goal' as: a desired future state to be achieved by a person with a disability as a result of rehabilitation activities. Rehabilitation goals are actively selected, intentionally created, have purpose and are shared (wherever possible) by the people participating in the activities and interventions designed to address the consequences of acquired disability.

Definition of 'goal setting'

From a literal perspective, the term 'goal setting' refers solely to the selection of goals. For the purposes of this review, we define 'goal setting' more broadly as: the establishment or negotiation of rehabilitation goals. Consistent with other clinical researchers publishing in this area (Wade 1998), we will consider 'goal setting' to be synonymous with 'goal planning'.

Definition of 'goal pursuit'

In addition to the establishment or negotiation of rehabilitation goals, there are a number of activities related to how rehabilitation goals are communicated, used or shared that are intended to enhance how effective or successful people are in working towards those goals. For the purposes of this review we will use the term 'goal pursuit' to refer to these additional goal‐related activities. These activities include: development of a plan or strategy to achieve stated rehabilitation goals, provision of explicit feedback (oral or written) on a person's progress towards their rehabilitation goals, and use of strategies to maintain or enhance commitment to set goals (such as peer discussion of progress toward an individual's rehabilitation goals, or use of posters and electronic diaries reminding people about their rehabilitation goals). As the behavioural effects of having a goal are often moderated by a number of factors (e.g. people's ability to develop a plan to reach their goal, their awareness of how their current abilities or performance compares with that required to achieve their goal, and their level of commitment to specific goals) it is important not to exclude these factors from a systematic review of the therapeutic effects of goal setting in rehabilitation contexts.

How the intervention might work

Goal setting has been attributed with multiple purposes (or functions). Levack 2006b presents a brief typology of purposes from the clinical literature, and Levack 2006c provides an overview of purposes attributed to goal setting by health professionals working in rehabilitation environments for people with acquired brain injury. These papers highlight a number of reasons why rehabilitation professionals might believe goal setting is important in clinical practice.

-

Goal setting might improve patient outcomes, by:

improving the patient's motivation to engage in therapeutic activities;

improving clinical teamwork (providing teams with shared direction; focusing collaborative interprofessional practice);

enhancing the working relationship between patients, families and health professional (e.g. through development of a shared language and shared understanding of a health condition and the rehabilitation process);

improving the patient's ability to self‐regulate desirable behaviour (e.g. by retraining self‐awareness or addressing goal neglect in patients with problems in those areas);

assisting patients (and their family) to adapt psychologically to the consequences of disability; or

enhancing specificity of training (e.g. focusing therapy for an individual on performance of a specific activity in a specific environment relevant to that individual's daily life).

Goal setting might enhance patient self‐determination (i.e. autonomy) – considered by some to be an important reason to undertake goal setting regardless of other outcomes achieved or not achieved in terms of health and functioning.

The degree of goal attainment might be a useful measure of health outcome.

Goal setting is a contractual or legislative requirement of service delivery.

While clinicians, patients or family members may have different opinions about the main reason for undertaking goal setting in rehabilitation, for this review the improvement of patient outcomes is of greatest interest. One important point here is that goal setting as an intervention for improving health outcomes for patients should be considered separately from goal setting for the purpose of outcome evaluation (where 'outcomes' are evaluated in terms of 'goal achievement'). In other words, goal setting as an intervention (i.e. as a way of engaging with people with acquired disability) may be effective in terms of achieving higher levels of improvement in a person's functional abilities (to pick just one type of outcome) without the specific goals of rehabilitation for that person necessarily being reached.

In terms of how goal setting might influence patient motivation or self‐regulation in clinical environments in order to achieve improvements in patient outcomes, a number of additional theories from psychology have been suggested as relevant to rehabilitation, including:

Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory;

Locke and Latham's Goal Setting Theory;

Schwarzer's Health Action Process Approach;

Aspin and Taylor's Proactive Coping Theory;

Leventhal's Self‐Regulation Model of Illness Behaviour; and

Carver and Scheiers' Control‐Process Model of Self‐Regulation.

An overview of these theories and their application to rehabilitation has been given elsewhere (Scobbie 2009; Siegert 2004; Siegert 2014a). Broadly speaking, these theories describe: how people use and respond to goals in order to monitor, alter or adapt their behaviour; how emotional responses to goals or progress toward goals influence future goal‐oriented behaviour; how perceptions of illness and perceptions of the effect of interventions influence goal‐oriented behaviour; and how the effects of goals can be moderated by various factors such as personal goal commitment, beliefs in one's ability to achieve a goal (self‐efficacy), task complexity, and the way goals are presented or worded.

In clinical practice, several other variables may influence the success of goal setting interventions. These include how meaningful the goals are to the individual patient (how committed patients are to the goals; how well they relate to their higher‐order life priorities) and how involved patients are in the selection of goals, factors that might reasonably be considered to contribute to the 'person‐centredness' of the goal‐setting approach (Wilson 2008). Also, how 'reasonable' or 'realistic' a goal is to achieve (Wilson 2008) and how involved family members and significant others are in the selection of goals have been considered important (Levack 2009; McMillan 1999; Visser‐Meily 2006; Wade 1999a). Lastly, some researchers and clinicians have proposed that goal setting is likely to be more successful when goals are set at the level of 'activity' and 'participation' than when goals are established to address impairments at the level of body structure and body function (Marsland 2010; Randall 2000). For example, a goal to be able to transfer independently from a wheelchair to a toilet (an activity‐level goal) or to return to paid employment (a participation‐level goal) would be considered, in general, more effective for improving patient outcomes than a goal to improve muscle strength of the quadriceps by 150% (a goal set at the level of body structure and body function).

Why it is important to do this review

There is extensive research from education (Boekaerts 2000; Pintrich 2000), industrial‐organisational psychology (Latham 2007; Locke 2002), cognitive psychology (Austin 1996; Custers 2010; Moskowitz 2009) and sport psychology (Burton 2010; Hall 2001; Wilson 2006) which has demonstrated the effect that goals can have on human behaviour. It seems reasonable to assume that goal setting could have a similar type of effect in populations of people participating in clinical rehabilitation. However, what this broad body of research has also demonstrated is that the effectiveness of goal setting and the mechanism by which goals achieve these effects can be highly dependent on context. For instance, it has been found that theories of goal setting from industrial‐organisational psychology are not as effective when applied to goal setting in the context of sport psychology, leading to the development of new theories of goal setting specific to the sport environment (Hall 2001).

As highlighted above, multiple approaches to goal setting in rehabilitation exist and several different mechanisms are suggested by which goals might affect patient outcomes. Furthermore, there is debate about the evidence for the effectiveness of goal setting for improving patient outcomes, and the most recent systematic review of this literature is now several years old (Levack 2006a). There is a need for a Cochrane review regarding the effects of goal setting or strategies to enhance goal pursuit to influence patient outcomes in rehabilitation for adults with acquired disability. This review is beneficial for determining whether the evidence shows that goal setting or strategies to enhance goal pursuit are effective interventions, as well as providing possible directions for future research into the use of rehabilitation goals in clinical work.

Objectives

To assess the effects of goal setting, and strategies to enhance goal pursuit, on health outcomes in adults with acquired disability participating in rehabilitation. To test the following comparisons:

a structured approach to goal setting, with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit versus no goal setting;

a structured approach to goal setting, with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit versus 'usual care' that may involve some goal setting but where no structured approach was followed;

interventions to enhance goal pursuit versus no interventions to enhance goal pursuit; and

one structured approach to goal setting and/or strategies to enhance goal pursuit versus another structured approach to goal setting and/or strategies to enhance goal pursuit.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cluster‐RCTs, or quasi‐RCTs (where allocation to study groups was by a method that was not truly random, such as alternation, assignment based on date of birth, case record number or date of presentation, or due to use of stratification or minimisation).

Types of participants

People receiving rehabilitation for disability acquired in adulthood (e.g. after 16 years of age).

For the purposes of this review 'disability' was defined according to the ICF as an 'umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations or participation restrictions' (WHO 2001a, p.3) that result from interactions between a person (with a health condition) and that person's contextual factors (environmental factors and personal factors). Thus, we excluded studies investigating the application of goal setting to health interventions for non‐disabled people (e.g. in public health or obstetric contexts). More specifically, this review included people with disability arising from injuries, illnesses or disorders, as categorised by the WHO (WHO 1992), involving:

the musculoskeletal system or connective tissue;

the skin or subcutaneous tissue;

the cardiac system (including the cerebrovascular system);

the respiratory system;

the nervous system;

the sensory system (e.g. eye, ear etc);

the endocrine, nutritional or metabolic system;

the genitourinary system; and

mental or behavioural function.

For the purposes of this review 'rehabilitation' was defined as 'a process aimed at enabling persons with disabilities to reach and maintain their optimum physical, sensory, intellectual, psychiatric and/or social functional levels, thus providing them with the tools to change their lives towards a higher level of independence. The rehabilitation process does not, however, involve initial medical care' (WHO 2001b, p.290). Thus, we excluded studies investigating the effects of goal‐directed decision‐making by medical staff in emergency or intensive care settings, or in the management of acute medical conditions such as sepsis.

Types of interventions

We included studies that investigated the effects of establishing and negotiating rehabilitation goals, with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit. For the purposes of this review, the term 'rehabilitation goals' refers to an actively selected and desired future state to be achieved by a person with a disability as a result of rehabilitation activities.

We included studies that investigated:

a structured approach to goal setting with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit in comparison to no goal setting; or

a structured approach to goal setting with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit in comparison to 'usual care' that may involve some goal setting but where no structured approach was followed; or

interventions to enhance goal pursuit in comparison to no interventions to enhance goal pursuit; or

one structured approach to goal setting and/or strategies to enhance goal pursuit in comparison to another structured approach to goal setting and/or strategies to enhance goal pursuit.

For the purposes of this review, approaches to goal setting were considered to differ if they involved different methods for:

identification, negotiation, or selection of rehabilitation goals; or

documentation of rehabilitation goals; or

involvement of health professionals, patients, family members or other significant people in the selection of rehabilitation goals.

Approaches to enhancing goal pursuit were considered to differ if they involve different methods for:

developing a plan on how to attain rehabilitation goals;

providing feedback to patients on their performance towards rehabilitation goals; or

enhancing patient commitment to attain rehabilitation goals.

We excluded studies investigating approaches to goal setting as an intervention compared to some other intervention intended to influence human cognition or behaviour (e.g. priming for pain attention in the case of Stenstrom 1994). We excluded any study that did not adequately control for additional treatment variables separate to the goal setting intervention. Hence we excluded studies in which goal setting formed only part of a whole programme of rehabilitation, where the outcomes of the intervention could not be specifically attributed to goal setting or to components of the goal setting process (e.g. Glasgow 2000).

Types of outcome measures

We excluded studies investigating only the immediate effects of goal setting. Studies were categorised as investigating the immediate effects of goal setting if they involved implementation of goal setting and collection of data on the effects of goal setting (e.g. in terms of immediate improvements in effort or performance on a set task) during only one session for each study participant, carried out over the course of less than one day (e.g. Gauggel 2001).

We prioritised the following outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Secondary outcomes

Outcomes at the level of body structure and function as defined by the ICF (WHO 2001a).

Patient self‐belief and engagement in rehabilitation, e.g. adherence, patient motivation, self‐efficacy.

Individual goal attainment.

Evaluation of care, e.g. satisfaction with care.

Service delivery level, e.g. cost of care, length of stay.

Adverse outcomes, e.g. complications, morbidity, mortality, readmission rate.

N.B. Individual goal attainment was not included as a primary outcome measure in this review as achievement of individualised goals is in part based on changes in health status achieved by rehabilitation patients, and in part based on the level of difficulty of the individually‐selected goals. It is possible therefore for two people to achieve the same degree of functional recovery (or gain in other outcomes) following rehabilitation, but score differently on measures based on achievement of individualised goals. As there is scope for debating what such differences in individualised goal attainment mean, we chose to select individual goal attainment as a secondary outcome.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases in September 2012, with an updated search conducted in January 2014 for articles published to the end of December 2013.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2013, Issue 12).

MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1950 to December 2013).

EMBASE (OvidSP) (1988 to December 2013).

PsycINFO (OvidSP) (1967 to December 2013).

CINAHL (EBSCOhost) (1981 to December 2013).

AMED (OvidSP) (1985 to December 2013).

Proquest Dissertations and Theses database (1673 to December 2013).

Detailed search strategies are presented in Appendices 1 to 7. We did not impose any language restrictions.

We searched the ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database for grey literature. We also searched databases in the WHO Clinical Trial Search Portal (www.who.int/trialsearch), Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (http://www.anzctr.org.au/), and Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com) to identify ongoing or recently completed studies (Appendix 8).

Searching other resources

We contacted experts in the field and authors of included studies for advice as to other relevant studies. We also searched reference lists of relevant studies and personal collections of articles. We sought full research reports of any potentially eligible studies that were published as abstracts or conference proceedings only. We included studies only published as abstracts or conference proceedings in the review where sufficient information about the study methods and data could be extracted from the abstract, published proceedings, or poster presentation, supplemented by author communication, with all sources of information noted in the section in Included studies. Where sufficient information could not be uncovered on potentially eligible studies, we excluded these studies, giving lack of information as the reason for this in the section in Excluded studies.

Data collection and analysis

The data collection and analysis methods were described in the review protocol (Levack 2012).

Selection of studies

Two review authors (WL and RS) independently screened all search results (titles and abstracts) for possible inclusion, and those selected by either or both authors were subject to full‐text assessment. The two review authors then independently assessed the selected articles for inclusion. The same two review authors resolved differences in the first instance by discussion, and then by input from a third review author from the review team. The whole review team debated particularly difficult decisions regarding inclusion. Any studies thus excluded but considered near the boundary for possible inclusion have been reported in Characteristics of excluded studies with the reason for exclusion given. We also present relevant ongoing studies in Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Data extraction and management

We used a standard data extraction form adapted from the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group's Data Extraction Template for all included studies. Two review authors (WL and RS) independently assessed the risk of bias in included studies and independently extracted data for each study. The two review authors resolved differences in the first instance by discussion, and then by input from a third author from the review team. Review authors were not blinded to the names of study authors, journals or institutions.

For included studies, we extracted data on the intervention aims, study aims, study design, methods used, characteristics of participants (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, principal health condition, inclusion of people with multimorbidities), characteristics of the study setting (e.g. geographic location, specific clinical context, co‐interventions being provided alongside goal setting), characteristics of the approach(es) to goal setting and strategies to enhance goal pursuit under investigation, outcome measures used, and reported findings.

Data extracted to categorise the approach to goal setting or goal pursuit under investigation included (if specified in the study's method):

the name of the approach to goal setting (e.g. GAS, SMART, COPM);

the health professional(s) involved in goal setting;

the training of health professionals for their involvement in goal setting;

the level of patient and/or family involvement in goal selection (e.g. whether goals were: prescribed with no input from study participants; selected through discussion and negotiation with the patient; selected through discussion and negotiation with the patient and their family; or selected by the study participants with no involvement of other parties);

the type of communication used for making selected goals explicit (e.g. written, oral);

whether or not the intervention involved an explicit process for developing a plan to achieve the stated goal(s), and if so what this was;

whether or not goals for study participants were made public to others (e.g. other patients);

whether or not study participants were reminded about their goals during the course of rehabilitation;

whether or not study participants were provided with feedback on their progress towards goals during the course of rehabilitation;

whether or not there was the development of written 'contracts' with participants to pursue specified goals;

assessment of the participants' level of commitment to attain their goals;

the level of goal difficulty (and how this was specified or quantified by the researchers); and

the targeted level of functioning for specific goals (e.g. if goals were set at the level of body structure and body function, activity, or participation, as defined by the ICF, WHO 2001a).

The first author (WL) then entered the data into Review Manager (RevMan 2014), with another author (RS) checking the accuracy of data entry.

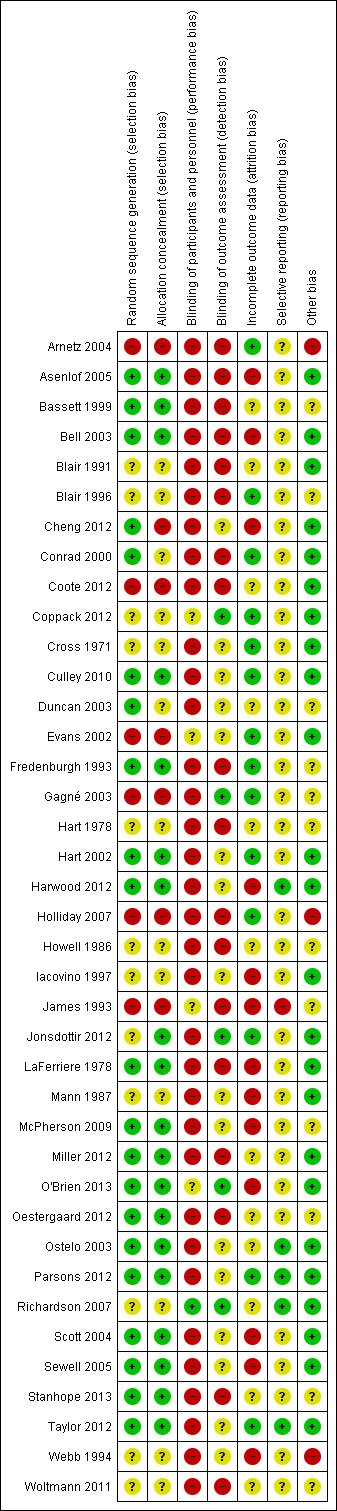

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed and reported on the risk of bias of included studies in accordance with the guidelines of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group (Ryan 2011), which recommends the explicit reporting of the following individual 'Risk of bias' elements for RCTs: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding (participants, personnel), blinding (outcomes assessment); incomplete outcome data (attrition bias; adequacy of intention‐to‐treat analysis); selective outcome reporting; other sources of bias (e.g. recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, loss of clusters, incorrect analysis, and comparability with RCT based on per person randomisation in the case of cluster‐RCTs; and suitability of cross‐over design, management of carry‐over effect, incorrect analysis, comparability of results with parallel‐group trials, treatment period effects, and randomisation of order of treatments in the case of cross‐over design RCTs).

We conducted 'Risk of bias' assessments in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), with risk of bias being rated as high risk, unclear risk or low risk for each element and for each study overall. We used the same criteria for assessment of risk of bias for quasi‐RCTs; these studies were rated as being at high risk of bias both for random sequence generation and allocation concealment.

In all cases, two authors (WL and RS) independently assessed the risk of bias in included studies. These two review authors resolved differences in the first instance by discussion, and then by input from a third author from the review team. We attempted to contact study authors for additional information about the included studies or for clarification of the study methods as required. In the case of studies where one of the study authors was also an author of this review (i.e. McPherson 2009 and Taylor 2012), another review author took the lead on the 'Risk of bias' assessment.

Measures of treatment effect

Three categories of primary outcomes were the focus of this review:

health‐related quality of life or self‐reported emotional status;

participation outcomes; and

activity outcomes, as defined by the ICF (WHO 2001a).

We adopted the approach used by Brennan 2009 and Horvat 2014 for selection and extraction of primary outcomes from included studies. We included any primary outcome identified by study authors that fell within the scope of the primary outcomes categories listed above. If multiple primary outcomes were identified within any category, we ranked the reported effect estimates for each of these outcomes and selected the outcome with the median effect estimate. If no primary outcome within our categories was specified, we adopted the following strategy. First we used any outcome within our categories specified in sample size calculations; then, if necessary, we ranked relevant intervention effect estimates, as reported, and selected the median effect estimate. If the number of outcomes was even (n), we included the outcome whose effect estimate was ranked n/2. We have reported in our results whether we used the primary outcome or the outcome with the median effect estimate. Where possible, we also verified whether the specified primary outcomes in included studies were consistent with those identified in trial protocols, trial registry entries or both.

We extracted the intervention effect estimate reported for all included outcomes (both primary and secondary outcomes) with the associated P value and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and the method of statistical analyses used to calculate them. For continuous data, where outcomes were measured in a standard way across studies, we reported the mean difference (MD) and 95% CI. Where outcomes were measured using different scales (e.g. for quality of life) we calculated a standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI. When calculating a SMD within each outcome category, we multiplied all mean values for reversed scored outcomes (where lower scores indicate a better outcome) by ‐1 to ensure that the direction of all scales (from better to worse outcomes) were consistent.

For dichotomous data, where outcomes were measured in a standard way we reported the risk ratio (RR) and 95% CI. For categorical outcomes (such as employment outcomes) we related the numbers reporting an outcome to the numbers at risk in each group to derive a RR. We dichotomised ordinal data (such as Likert scales for symptom improvement) and managed them as a categorical outcome. We treated GAS scores as ordinal rather than interval data, as recommended by Steenbeek 2007 and Tennant 2007, and we treated count data as continuous data.

Unit of analysis issues

The primary analysis was planned on the basis of per person randomisation. For all studies we considered the possibility of unit of analysis issues arising from the inclusion of cluster‐randomised designs, repeated measurements and studies with more than two treatment groups. When applicable, we dealt with unit of analysis issues by analysing the data according to recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). In cluster‐RCTs, we first sought to use effect estimates and standard errors that were adjusted for clustering, combining the studies using the generic inverse‐variance method. When analysis in a cluster‐RCT did not take account of clustering, then we attempted to approximate the cluster‐adjusted effect size and standard error based on available data if the unadjusted effect estimate, the number or size of clusters, and the intraclass correlations were provided. If the intraclass correlation coefficient could not be obtained then we endeavoured to use an estimate from similar studies. If none of these options were possible, we included the studies unadjusted for clustered in the analyses, but then tested the effect doing this by examining the results of analyses with these studies removed. In studies with repeat observations (collecting data using the same measures on participants at a number of different time points) we selected the longest follow‐up data from each study. If studies had more than two groups we combined all relevant experimental intervention groups of the study into a single group, and combined all relevant control intervention groups into a single control group.

Dealing with missing data

If data were missing from the relevant comparisons we attempted to contact the study authors to obtain the information. Where studies did not state that results were reported using an intention‐to‐treat analysis for primary outcomes, we contacted the study authors to request data to enable us to conduct such an analysis. If no response from authors was provided, we analysed results as reported.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Given the potential for clinical and methodological diversity in studies that might have been eligible for inclusion, it was important to consider heterogeneity in the data analysis. Clinical heterogeneity was determined before analysis of data by extracting and considering information on each study's patient populations, clinical contexts, approaches to goal setting, and outcome measures used.

We identified statistical heterogeneity in studies thought to be clinically and methodologically similar by visual inspection of forest plots and by using a standard Chi2 test and a significance level of alpha = 0.1, in view of the low power of such tests. We also examined heterogeneity with I2, where I2 values of 50% or more were deemed to indicate a substantial level of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). We used a random‐effects model to assess heterogeneity as, prior to conducting the review, we had anticipated finding substantive differences in the patient populations, rehabilitation settings and approaches to the selection and use of goals in the included studies.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed the extent of publication bias through visual inspection of asymmetry and running the regression‐based method for a funnel plot in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014). We considered other forms of reporting bias (e.g. multiple publication bias, location bias, language bias, outcome reporting bias) on review of the full papers for each included study. The possibility of reporting bias is presented in the results below.

Data synthesis

We began the data synthesis with a narrative overview of the findings in the form of a table. The review authors, as a team, considered the comparability of the participants, clinical contexts, approaches to goal setting, and types of outcome data in order to determine whether statistical pooling of results was appropriate. Where appropriate, we used meta‐analytical methods to pool outcome data from sufficiently homogeneous studies to calculate effects in the comparisons outlined in our Objectives. Following data extraction, but prior to data analysis, we made the post‐hoc decision to combine measures of self‐reported emotional status with self‐reported measures of health‐related quality of life. We did this because few studies reported measures of health‐related quality of life and because the two concepts were deemed to be sufficiently similar for the results of a meta‐analysis to be clinically meaningful: quality of life, for instance, often has an emotional health subscale. We conducted all analyses according to guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed quality of evidence using GRADE, and have presented a summary of the results of the data synthesis and assessment of the quality of the evidence in a 'Summary of findings' table. In 'Table 1' and in 'Table 2' we included summary information on the following: health‐related quality of life or self‐reported emotional status, participation outcomes, activity outcomes, outcomes at the level of body structure and function, patient engagement in rehabilitation, and self‐efficacy.

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Goal setting with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit compared to no goal setting for adults with acquired disability participating in rehabilitation.

| Goal setting with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit compared to no goal setting for adults with acquired disabilityparticipating in rehabilitation | |||||

| Patient or population: adults with acquired disability participating in rehabilitation Settings: inpatient, outpatient, and community‐based healthcare services Intervention: goal setting with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit Comparison: no goal setting | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| No goal setting | Goal setting (with or without strategiesto enhance goal pursuit) | ||||

| Health‐related quality of life or self‐reported emotional status Follow‐up: median 11.5 weeks | The mean Physical Component Summary Scores on the Short Form‐36 for the control group was 35.9 points (SD 10.1) (out of a possible score of 0‐100)1 | The mean Physical Component Summary Scores on the Short Form‐36 for the intervention group was 5.5 higher (1.7 to 8.9 higher)2 | 446 (8 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,5 | Higher scores indicate better outcomes. Scores estimated using a SMD of 0.54 (95% CI 0.17 to 0.88), indicative of an effect size that may range from small to large.Two additional studies with 142 participants however, reported no means or SD, but indicated that goal setting may lead to little to no difference in health‐related quality of life or self‐reported emotional status |

| Participation Follow‐up: median 3 months | See comment | See comment | 254 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,6 | Outcomes unable to be pooled due to lack of reporting of data and lack of similarities in the types of measures used. We are uncertain whether goal setting improves participation‐level outcomes |

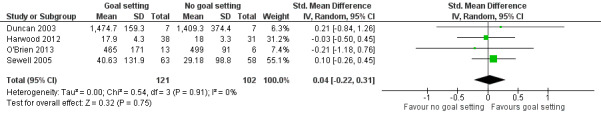

| Activity Follow‐up: median 18 weeks | The mean Barthel Index score for the control group was 18 points (SD 3.3) (out of a possible score of 0‐20)7 | The mean Barthel Index score for the intervention groups was 0.1 higher (0.7 lower to 1 higher)2 | 223 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,6 | Higher scores indicate better outcomes. Scores estimated using a SMD of 0.04 (95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.31). This evidence suggests that goal setting may not improve activity‐level outcomes |

| Body structure and body function Follow‐up: median 3 months | See comment | See comment | 235 (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low8, 9 | Unable to pool outcomes due to lack of similarities in the types of measures used. We are uncertain whether goal setting improves outcomes at the level of body structure and body function |

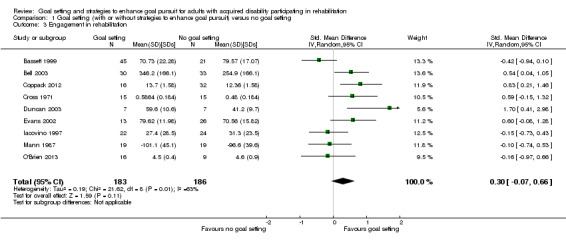

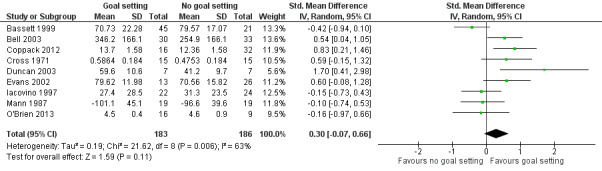

| Engagement in rehabilitation (motivation, involvement and adherence) Follow‐up: median 8.5 weeks | The mean number of hours worked on a 26‐week support work placement programme for the control groups was 255 hours of work (SD 166)10 | The intervention groups worked 50 hours more (12 hour less to 110 hours more)2 on a 26‐week support work placement programme | 369 (9 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low4,6,8,11 | Higher scores indicate better engagement. Scores estimated using a SMD of 0.30 (95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.66). One additional study with 27 participants reported no means or SD but indicated that goal setting may lead to little to no difference in engagement in rehabilitation. One further study with 367 participants measured medication regime adherence as a dichotomous variable, and reported that the odds for the goal setting group adhering was 1.13 times higher (95% CI 1.08 to 1.19) than that of the no goal setting group. Overall, we are uncertain whether goal setting improves engagement in rehabilitation |

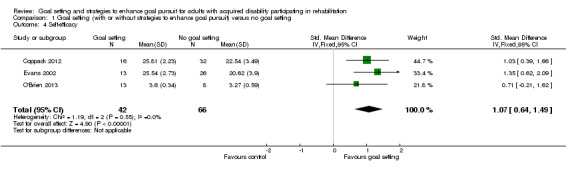

| Self‐efficacy Follow‐up: median 5 weeks | The mean Task Self‐efficacy score for the control groups was 3.3 points (SD 0.6) (out of a possible score of 1‐4)12 | The mean self‐efficacy in the intervention groups was 0.6 higher (0.4 to 0.9 higher)2 | 108 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low6,8 | Higher scores indicate better self‐efficacy. Scores estimated using a SMD of 1.07 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.49), indicative of a moderate to large effect size. One additional study with 88 participants reported no means or SD, but suggested that goal setting after rehabilitation may lead to little to no difference in self‐efficacy |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standard mean difference | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1 The Physical Component Summary Score on the Short Form‐36 was used for this illustrative comparative risk as this was deemed to be the most common, most general measure of quality of life used in the studies included in the meta‐analysis for this outcome. The data on assumed risk for the Physical Component Summary Score on the Short Form‐36 was taken from control group data in the study that used this measure (Harwood 2012). 2 The difference in the corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) was calculated by multiplying the SD for the assumed risk by the SMD from the meta‐analysis (and its 95% CI). 3 The GRADE rating was downgraded by one level, given overall unclear risk of bias. 4 The GRADE rating was downgraded due to the presence of substantial unexplained heterogeneity in the data. 5 The GRADE rating was downgraded due to imprecision, with the confidence interval for the SMD ranging from below 0.2 to above 0.8. 6 The GRADE rating was downgraded due to the small total number of participants in the included studies 7 The Barthel Index was used for this illustrative comparative risk as this was deemed to be the most common, most general measure of activity used in the studies included in the meta‐analysis for this outcome. The data on assumed risk for the Barthel Index was taken from control group data in the study that used this measure (Harwood 2012). 8 The GRADE rating was downgraded by two levels, given overall high risk of bias 9 The GRADE rating was downgraded due to the findings being based on descriptive analysis of a series of small studies that could not be pooled in a meta‐analysis, reaching different conclusions regarding treatment effect, 10 Hours worked on a support work placement was used for this illustrative comparative risk as this was deemed to be the most meaningful, most general measure of engagement used in the studies included in the meta‐analysis for this outcome. The data on assumed risk for the hours worked on a support work placement was taken from control group data in the study that used this measure (Bell 2003). 11 The GRADE rating was downgraded due to the 95% confidence interval crossing the line of no effect as well as reaching above an SMD of 0.5 12 Task Self‐efficacy was used for this illustrative comparative risk as this was deemed to be the most general measure of self‐efficacy used in the studies included in the meta‐analysis for this outcome. The data on assumed risk for Task Self‐efficacy was taken from control group data in the study that used this measure (O'Brien 2013).

Summary of findings 2. Structured goal setting with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit compared to 'usual care' that involved some goal setting but where no structured approach was followed for adults with acquired disability participating in rehabilitation.

| Structured goal setting with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit compared to 'usual care' that involved some goal setting but where no structured approach was followed for adults with acquired disabilityparticipating in rehabilitation | |||||

| Patient or population: adults with acquired disability participating in rehabilitation Settings: inpatient, outpatient, and community‐based healthcare services Intervention: structured goal setting with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit Comparison: 'usual care' that involved some goal setting but where no structured approach was followed | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| 'Usual care' | Structured goal setting (with or without strategiesto enhance goal pursuit) | ||||

| Health‐related quality of life or self‐reported emotional status Follow‐up: median 24 weeks | The mean Mental Component Summary Scores on the Short Form‐36 for the control group was 58.5 points (SD 10.0) (out of a possible score of 0‐100)1 | The mean Mental Component Summary Scores on the Short Form‐36 for the intervention group was 1.8 higher (1.9 lower to 5.6 higher)2 | 441 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | Higher scores indicate better outcomes. Scores estimated using a SMD of 0.18 (95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.56). One additional quasi‐RCT with 201 participants reported no means or SD, but indicated that usual care may lead to higher quality of life than structured goal setting. One further study with 122 participants reported that participants in the structured goal setting group were more likely to report being more satisfied or much more satisfied with their daily life compared to participants in the usual care group 3 months post intervention (RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.88), but not 2 years later (RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.70). Overall, this evidence suggests that structured goal setting in rehabilitation may result in little to no improvement in health‐related quality of life or self‐reported emotional status |

| Participation London Handicap Scale | See comment | See comment | 201 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5,6 | One quasi‐RCT reported no means or SDs for this outcome, but did not suggest that structured goal setting improves participation‐level outcomes. We are uncertain whether structured goal setting improves participation‐level outcomes |

| Activity Follow‐up: median 9 months | The mean Functional Indepdence Measure score in the control groups was 111.8 points (SD 19.8)7 | The mean Functional Independence Measure score in the intervention groups was 3.4 higher (3.0 lower to 9.7 higher)2 | 277 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low8,9 | Higher scores indicate better outcomes. Scores estimated using a SMD of 0.17 (95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.49). This evidence suggests that structured goal setting in rehabilitation may not improve activity‐level outcomes. One additional quasi‐RCT (201 participants) measured functional independence and reported no means or SD, and two further studies (118 participants) measured activity levels as ordinal data, but overall these studies also indicated that structured goal setting in rehabilitation may not improve activity‐level outcomes |

| Body structure and body function Follow‐up: median 15 months | See comment | See comment | 229 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5,10 | Unable to pool outcomes due to lack of similarities in the types of measures used. We are uncertain whether structured goal setting improves outcomes at the level of body structure and body function |

| Engagement in rehabilitation Follow‐up: median 5 weeks | See comment | See comment | 32 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5, 9 | One study reported data on patient motivation in rehabilitation. A small difference in favour of structured goal setting in comparison to usual care was reported in terms of patient‐rated motivation (MD 1.40 on a 10‐point scale of self‐reported motivation, 95% CI 0.43 to 2.37) but not for therapist‐rated score of motivation (MD 0.48 on an 8‐point scale of therapist‐rated patient motivation, 95% CI ‐0.41 to 1.37) |

| Self‐efficacy Follow‐up: 18 months | The mean self‐efficacy in the control groups was 168.6 points (SD 29.8) (on a scale of 0 to 200)11 | The mean self‐efficacy in the intervention groups was 11.0 higher (0.6 to 21.2 higher)2 | 134 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low5, 9 | Higher scores indicate better self‐efficacy. Scores estimated using a SMD of 0.37 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.71), indicative of an effect size that may range from small to large |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SD: standard deviation; SMD: standard mean difference | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1 The Mental Component Summary Score on the Short Form‐36 was used for this illustrative comparative risk as this was deemed to be the most common, most general measure of quality of life used in the studies included in the meta‐analysis for this outcome. The data on assumed risk for the Mental Component Summary Score on the Short Form‐36 was taken from control group data in the study that used this measure (Parsons 2012). 2 The difference in the corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) was calculated by multiplying the SD for the assumed risk by the SMD from the meta‐analysis (and its 95% CI). 3 The GRADE rating was downgraded due to the presence of substantial unexplained heterogeneity in the data. 4 The GRADE rating was downgraded due to the 95% confidence interval crossing the line of no effect as well as reaching above an SMD of 0.5. 5 The GRADE rating was downgraded by two levels due to high risk of bias. 6 The GRADE rating was downgraded due to there being no published information on effect size or variance 7 The Functional Independence Measure was used for this illustrative comparative risk as this was deemed to be the most common, most general measure of activity levels used in the studies included in the meta‐analysis for this outcome. The data on assumed risk for the Functional Independence Measure was taken from control group data in the study that used this measure (Taylor 2012). 8 The GRADE rating was downgraded by one level, given overall unclear risk of bias. 9 The GRADE rating was downgraded due to the small number of participants and high attrition rate. 10The GRADE rating was downgraded due to the findings being based on descriptive analysis of a series of small studies that could not be pooled in a meta‐analysis, reaching different conclusions regarding treatment effect, 11 The Self‐efficacy Scale was used for this illustrative comparative risk as this was deemed to be the most common, most general measure of self‐efficacy used in the studies included in the meta‐analysis for this outcome. The data on assumed risk for the Self‐efficacy Scale was taken from control group data in the study that used this measure (Asenlof 2005).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where there were sufficient data (i.e. at least 10 studies) and where it was appropriate in the context of the study, we planned to conduct subgroup analysis on the basis of four factors:

level of patient and/or family involvement in goal selection;

level on the ICF at which rehabilitation goals were set;

level of goal difficulty; and

presence of cognitive or psychiatric impairments in study populations.

However, we did not identify sufficient studies to permit any of these subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We undertook sensitivity analyses to examine the influence of risk of bias associated with including the studies in each meta‐analysis. We removed studies at the greatest risk of bias (i.e. those that failed to randomise adequately or failed to conceal random allocation) from the analysis in order to test the strength of evidence for the various effect estimates.

Consumer participation

We invited consumer referees to comment on the protocol and on the completed review through standard Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group editorial processes.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We ran searches in September 2012, and again in January 2014, generating 9019 records, after removing duplicates. We screened the titles and abstracts of all citations and identified 151 articles that were potentially eligible for inclusion. We reviewed these in full text against the selection criteria, and identified 39 studies that met the inclusion criteria. Seven of these 39 studies were reported in multiple publications (see Table 3).

1. Included studies reported in multiple publications.

| Study | Other papers reporting study |

| Asenlof 2005 | Asenlof 2006; Asenlof 2009 |

| Blair 1991 | Blair 1995 |

| Duncan 2003 | Duncan 2002 |

| Jonsdottir 2012 | Jonsdottir 2012b |

| Ostelo 2003 | Ostelo 2000; Ostelo 2004 |

| Scott 2004 | Ranta 2000; Setter‐Kline 2007; Watson 2001 |

| Sewell 2005 | Sewell 2001 |

Included studies

Thirty‐nine studies met the selection criteria for this review (see Characteristics of included studies).

Comparison groups

Comparison 1

Of the 39 trials, 18 compared a structured approach to goal setting, with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit, to no goal setting (Bassett 1999; Bell 2003; Blair 1991; Blair 1996; Coote 2012; Coppack 2012; Cross 1971; Duncan 2003; Evans 2002; Fredenburgh 1993; Harwood 2012; Howell 1986; Iacovino 1997; Mann 1987; O'Brien 2013; Scott 2004; Sewell 2005; Stanhope 2013).

Comparison 2

Fourteen trials compared a structured approach to goal setting, with or without strategies to enhance goal pursuit, to 'usual care' that may have involved goal setting but where no structured approach to goal setting was followed (Arnetz 2004; Asenlof 2005; Cheng 2012; Gagné 2003; Hart 1978; Holliday 2007; Jonsdottir 2012; LaFerriere 1978; McPherson 2009; Oestergaard 2012; Ostelo 2003; Parsons 2012; Taylor 2012; Woltmann 2011). Four of the studies in this comparison group were described by the authors as being pilot studies or feasibility studies (Gagné 2003; Jonsdottir 2012; McPherson 2009; Taylor 2012).

Comparison 3

Two trials investigated an intervention where the only difference to a control group was the use of a strategy to enhance goal pursuit (Culley 2010; Hart 2002).

Comparison 4

Nine trials compared one structured approach to goal setting and/or strategies to enhance goal pursuit to another structured approach to goal setting and/or strategies to enhance goal pursuit (Bassett 1999; Blair 1991; Blair 1996; Conrad 2000; James 1993; McPherson 2009; Miller 2012; Richardson 2007; Webb 1994). Four of these nine trials had more than two goal setting intervention groups, permitting their inclusion in more than one comparison in this review (Bassett 1999; Blair 1991; Blair 1996; McPherson 2009). For studies that had more than one intervention group, we only included the groups that met the inclusion criteria for analysis.

Communication with study authors

Of the 39 included studies, we found that 5 were reported in sufficient detail such that we required no further information about these studies for the purpose of this review (Hart 2002; Harwood 2012; James 1993; Ostelo 2003; Taylor 2012). We attempted to contact the authors of each of the other 34 studies to obtain additional information, and were successful with 19 (Arnetz 2004; Asenlof 2005; Bassett 1999; Bell 2003; Coote 2012; Conrad 2000; Culley 2010; Duncan 2003; Evans 2002; Holliday 2007; Jonsdottir 2012; LaFerriere 1978; McPherson 2009; Miller 2012; O'Brien 2013Parsons 2012; Scott 2004; Sewell 2005; Stanhope 2013), although full details were only available for 15 of these studies (Asenlof 2005; Bassett 1999; Coote 2012; Conrad 2000; Culley 2010; Duncan 2003; Evans 2002; Jonsdottir 2012; LaFerriere 1978; McPherson 2009; Miller 2012; O'Brien 2013; Parsons 2012; Sewell 2005; Stanhope 2013). We had at least one unanswered question about methods or outcome data for 24/39 (62%) of the included studies.

Types of studies

Unit of randomisation

Six studies used a cluster‐RCT design, randomising groups of participants clustered on the basis of the residential facility in which they lived (Blair 1991), the family physician with whom they were registered (Parsons 2012), the healthcare organisation or hospital providing their services (Cheng 2012; Stanhope 2013; Taylor 2012), or on the basis of the case manager who was managing their rehabilitation planning (Woltmann 2011). For three of these studies (Parsons 2012; Stanhope 2013; Taylor 2012) the effects of clustering on means and SDs in the outcome measures reported could be estimated from the information provided in the paper or from additional information provided by the study authors. For the other three studies (Blair 1991; Cheng 2012; Woltmann 2011) information on the effects of clusters on the data reported could not be accessed or estimated from other related publications. For these three studies we chose to include the data as reported in the published paper, but to report in our results where this occurred, and to test the influence of these decisions in our sensitivity analyses. For two other studies, randomisation occurred at the level of the participants' goals rather than at the level of the participant, with each participant having multiple goals being randomly allocated to either an intervention condition for enhancing goal recall or a control condition (Culley 2010; Hart 2002). For these two studies raw outcome data were available from the published paper or via author communication, so our analysis could be conducted at the same level as the unit of randomisation.

Sample sizes

Sample sizes ranged from 7 to 367, with a total of 2846 participants in the 39 studies addressing the 4 main comparisons in the review. Six of the included studies were reported as being pilot studies or feasibility studies (Gagné 2003; Jonsdottir 2012; McPherson 2009; Miller 2012; Richardson 2007; Taylor 2012) and therefore were not designed to have a sufficiently large sample size to detect statistically significant differences.

Types of settings

Seven of the included studies were conducted within inpatient hospital settings. This included three studies conducted within multidisciplinary units for people with neurological conditions (Holliday 2007; Jonsdottir 2012; Taylor 2012), one study conducted within a rheumatology unit (Arnetz 2004), two studies conducted within orthopaedic surgical units (Cross 1971; Oestergaard 2012), and one study conducted in a number of different hospital ward settings (Gagné 2003). An eighth study was conducted in both residential and outpatient‐based rehabilitation services for people with brain injury (Culley 2010). Eleven additional studies were conducted in outpatient or primary care settings, including four studies conducted within a cardiovascular rehabilitation service (Conrad 2000; Duncan 2003; Iacovino 1997; Mann 1987), one study conducted within a pulmonary rehabilitation service (Sewell 2005), one study conducted within an exercise laboratory (O'Brien 2013), four studies conducted within physiotherapy services (Asenlof 2005; Bassett 1999; Evans 2002; Ostelo 2003), and one study conducted within a cognitive behavioural therapy programme for chronic pain (James 1993). One additional study was undertaken in a short‐term residential rehabilitation unit for chronic pain (Coppack 2012).

The remaining 19 included studies were conducted in community and/or residential care settings. These included eight studies conducted within community‐based mental health services (Bell 2003; Coote 2012; Fredenburgh 1993; Hart 1978; Howell 1986; LaFerriere 1978; Stanhope 2013; Woltmann 2011), two studies conducted within residential care services for older adults (Blair 1991; Blair 1996), two studies conducted within community‐based diabetes services (Miller 2012; Richardson 2007), three studies conducted as part of home‐based nursing services (Cheng 2012; Parsons 2012; Scott 2004), three studies conducted within residential and home‐based service for people with brain injury (Hart 2002; McPherson 2009; Webb 1994), and one study conducted in people's homes after stroke (Harwood 2012).

Of the 39 included studies, 17 were conducted in the United States of America (USA) (Bell 2003; Blair 1991; Blair 1996; Cross 1971; Duncan 2003; Fredenburgh 1993; Gagné 2003; Hart 1978; Hart 2002; James 1993; LaFerriere 1978; Miller 2012; Richardson 2007; Scott 2004; Stanhope 2013; Webb 1994; Woltmann 2011), 7 in the United Kingdom (UK) (Coote 2012; Coppack 2012; Culley 2010; Evans 2002; Holliday 2007; Howell 1986; Sewell 2005), 6 in New Zealand (Bassett 1999; Harwood 2012; McPherson 2009; O'Brien 2013; Parsons 2012; Taylor 2012), 3 studies in Canada (Conrad 2000; Iacovino 1997; Mann 1987), 2 in Sweden (Arnetz 2004; Asenlof 2005), and 1 in each of Denmark (Oestergaard 2012), Switzerland (Jonsdottir 2012), Hong Kong (Cheng 2012), and the Netherlands (Ostelo 2003).

Types of participants

Participants (people receiving services) in the 39 included studies were adults receiving rehabilitation interventions for neurological conditions, including stroke in eight studies (Culley 2010; Hart 2002; Harwood 2012; Holliday 2007; Jonsdottir 2012; McPherson 2009; Taylor 2012; Webb 1994), musculoskeletal or chronic pain conditions in 10 studies (Arnetz 2004; Asenlof 2005; Bassett 1999; Coppack 2012; Cross 1971; Evans 2002; James 1993; O'Brien 2013; Oestergaard 2012; Ostelo 2003), mental health conditions in 8 studies (Bell 2003; Coote 2012; Fredenburgh 1993; Hart 1978; Howell 1986; LaFerriere 1978; Stanhope 2013; Woltmann 2011), cardiovascular conditions in 5 studies (Conrad 2000; Duncan 2003; Iacovino 1997; Mann 1987; Scott 2004), age‐related disability in 3 studies (Blair 1991; Blair 1996; Parsons 2012), diabetes in 2 studies (Miller 2012; Richardson 2007), and respiratory disorders in 1 study (Sewell 2005). The remaining 2 studies involved a mixed sample of patients with chronic disabling conditions (Cheng 2012; Gagné 2003).

Types of interventions

A range of different approaches to goal setting were employed in the included studies. Fifteen studies involved one or more named approaches to goal setting. Of these, seven employed GAS or a modified version of GAS as the method of goal setting under investigation (Arnetz 2004; Blair 1991; Blair 1996; Hart 1978; Howell 1986; LaFerriere 1978; Webb 1994). Three other studies investigated the effect of the COPM as a method of person‐centred goal setting (Oestergaard 2012; Sewell 2005; Taylor 2012). Five further studies investigated the effect of goal setting and strategies to enhance goal pursuit based on use of the 'ICF Rehab Cycle' (Jonsdottir 2012), the Patient Goal Priority Questionnaire (Asenlof 2005), the TARGET method of goal setting (Parsons 2012), Goal Management Training and Identity Oriented Goal Training (McPherson 2009), and the Goal Setting and Planning skills (GAP) programme (Coote 2012).