Abstract

Gastric cancer (GC), one of the most lethal malignant tumors, is highly aggressive with a poor prognosis, while the molecular mechanisms underlying it remain largely unknown. Although advanced imaging techniques and comprehensive treatment facilitate the diagnosis and survival of some GC patients, the precise diagnosis and prognosis are still a challenge. The present study used publicly available gene expression profiles from The Cancer Genome Atlas and Gene Expression Omnibus datasets including mRNA, micro (mi)RNA and circular (circ)RNA of GC to establish a competing endogenous RNA network (ceRNA). Further, the present study performed least absolute shrinkage and selector operator regression analysis on the hub RNAs to establish a prediction model with mRNA and miRNA. The ceRNA network contained 109 edges and 56 nodes and the visible network contains 13 miRNAs, 9 circRNAs and 34 mRNAs. The five mRNA-based signature were CTF1, FKBP5, RNF128, GSTM2 and ADAMTS1. The area under curve (AUC) value of the diagnosis training cohort was 0.9975. The prognosis of the high-risk group (RiskScore >4.664) was worse compared with that of the low-risk group (RiskScore ≤4.664; P<0.05) in the training cohort. The five miRNA-based signature were miR-145-5p, miR-615-3p, miR-6507-5p, miR-937-3p and miR-99a-3p. The AUC value of the diagnosis training cohort was 0.9975. The prognosis of the high-risk group (RiskScore >1.621) was worse compared with that of the low-risk group (RiskScore ≤1.621; P<0.05) in the training cohort. The validation cohorts indicated that both five mRNA and five miRNA-based signatures had strong predictive power in diagnosis and prognosis for GC. In conclusion, a ceRNA network was established for GC and a five mRNA-based signature and a five miRNA-based signature was identified that enabled diagnosis and prognosis of GC by assigning patient to a high-risk group or low-risk group.

Keywords: gastric cancer, competing endogenous RNA, least absolute shrinkage and selector operator, diagnosis, prognosis

Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) has a highly aggressive clinical course making it one of the most lethal malignant tumors with a discouraging prognosis. Comparing published data by GLOBOCAN in 2012, the updated 2018 edition data showed an increase in incidence and mortality with 1,033.7 thousand new patients and 782.7 thousand deaths per year worldwide (1,2). More advanced gastric endoscopic imaging provides an opportunity for clinicians to detect the precancer lesions and treat the tumor at an endoscopically curable stage. The strategy of early detection and endoscopic resection has lowered morbidity in the countries with a high prevalence of GC, including Japan and South Korea (3–5). However, in other regions, a shortage of properly trained endoscopy operators and inconsistencies in diagnosis between pathologists contribute to the fact that a significant proportion of patients are diagnosed at advanced stage. Accurate diagnosis, especially for those who cannot be biopsied, is an urgent problem that must be overcome for treatment of GC.

Although individual treatments, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and molecular targeted therapy, have made great improvements, those with advanced-stage GC still have a poor 5-year survival rate (6). These poor outcomes have resulted in research focusing on identifying prognostic related factors, including age, gender, tumor grade and pathological molecular subtypes (7,8). In addition, accumulating studies identify non-coding RNAs including micro (mi)RNA, circular (circ)RNA and long-noncoding RNA as having prognostic value. Although studies highlight the value of biomarkers, some limitations cannot be ignored, such as conclusions based on a single research cohort, inadequate multi-center validation, single marker, and small sample sizes (9–12). Therefore, new biomarkers with high accuracy and specificity are needed to improve the diagnosis and prognosis of GC.

The present study used publicly available gene expression profiles from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets including mRNA, miRNA and circRNA of GC to establish a competing endogenous (ce)RNA network. The prediction models based on 5-mRNA signature and 5-miRNA signature were generated by least absolute shrinkage and selection operation (LASSO) penalized regression. The prediction models showed a good capacity for diagnosis and prognosis in both internal validation groups and external validation sets. Thus, the present study identified and validated new candidate genes to diagnose and prognose GC by assigning a patient to high-risk or low-risk group.

Materials and methods

Patients and datasets

All the gene expression profiles were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) database or Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx; http://gtexportal.org/home/) project. The information of all selected datasets including sample size and sequencing form are listed in Table I. GTEx data was used to verify the diagnostic model as a supplement to normal samples.

Table I.

Datasets used in this study and their sample distribution.

| Dataset | Experiment type | RNA type | Tumor | Normal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA | RNA-seq | mRNA | 375 | 32 |

| GSE54129 | Expression profiling by array | mRNA | 111 | 21 |

| GTEx | RNA-seq | mRNA | - | 207 |

| TCGA | miRNA-Seq | miRNA | 436 | 41 |

| GSE106817 | Non-coding RNA profiling by array | miRNA | 115 | 2,759 |

| GSE112264 | Non-coding RNA profiling by array | miRNA | 50 | 41 |

| GSE83521 | Non-coding RNA profiling by array | circRNA | 6 | 6 |

| GSE93541 | Non-coding RNA profiling by array | circRNA | 3 | 3 |

TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GTEx, Genotype-Tissue Expression; miRNA, microRNA; circRNA, circularRNA.

Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

DEGs, including mRNA, miRNA and circRNA were identified from the aforementioned datasets. Significant DEGs (|log2FC| > 2, adjusted P-value <0.05) were identified by using the Limma package (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html) of R 4.0.3 (13,14).

Weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA)

Hub genes were identified using WGCNA. WGCNA networks were constructed for mRNA, miRNA and circRNA using the GSE54129, GSE106817 and GSE93541 datasets, respectively. First, the similarity matrix was constructed based on the expression data by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient between two genes, the top 20% differentially expressed mRNA, the top 50% of miRNA and the top 75% of circRNA were chosen for further study. Next, clustering detection was performed to exclude outlier samples. Also, an appropriate power of β was adopted as a soft-thresholding parameter through network topological analysis to construct scale-free networks. An adjacency matrix was next transformed into a topological overlap matrix (TOM), 1-TOM was used as the distance to cluster the genes and a dynamic pruning tree was built to identify the modules. Finally, the correlation between phenotypes (tumor or normal tissue) and modules was calculated to recognize the most clinically significant ones (15).

Construction of ceRNA network

RNAhybrid (https://bibiserv.cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de/rnahybrid) was used to predict the interaction between circRNA and miRNA (16). miRWalk 3.0 (http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/) was used to predict the interaction between mRNA and miRNA (17), while the circRNA-miRNA-mRNA network was built using Cytoscape 3.8.2 (18).

Functional annotation of hub mRNA

Node mRNAs in ceRNA network was conducted to Gene Ontology (GO) molecular function enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment using clusterProfiler package of R4.0.3 (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html). P<0.05 was defined as the threshold of statistically significance (19).

Screening diagnostic and prognostic signature

To screen diagnostic and prognostic signatures, LASSO regression analysis was performed using the glmnet (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glmnet/index.html) package of R 4.0.3 in TCGA dataset. After 10-fold cross validation, the top 5 mRNA and miRNA ranked by absolute value of regression coefficient were token as diagnostic and prognostic signature for further study (20).

Construction of support vector machine (SVM) diagnostic model

SVM diagnostic model was constructed to predict carcinoma and non-carcinoma by using scikit-learn package supplied by python v3.8 (https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-3812/) (21,22). Grid search with 3-fold cross validation was conducted to test all parameters values shown in Table II, then the diagnostic model was constructed based on best parameter combination. Finally, the model was verified by 10-fold cross validation and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was drawn to evaluate the classification efficiency of the model (23).

Table II.

Support vector machine model parameter options.

| Parameter name | Parameter value range |

|---|---|

| Penalty C | 0.01-30 |

| Gamma | 1×10−10−1 |

| Kernel | rbf, linear |

Construction of prognostic model

The prognostic model was used to predict prognosis based on RiskScore value. RiskScore values were calculated using a linear combination of gene expression values weighted by univariate Cox regression coefficients. The standard form was defined as RiskScore=∑(βi × Xi), where i is the number of prognostic signatures, β is the correlation coefficient of prognostic signatures in univariate Cox regression analysis and X is the expression value of prognostic signatures (24).

Results

Differential expression analysis

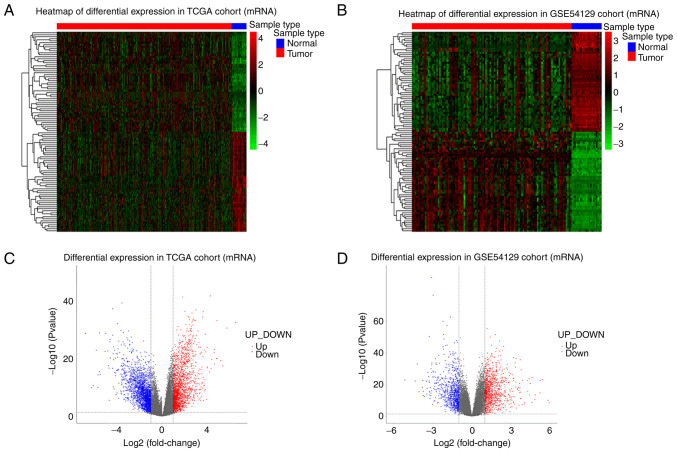

The expression data between cancerous and non-cancerous samples were compared and DEGs were defined according to the standard of |log2FC| >2 and adjusted P-value <0.05. The number of DEGs in each dataset were summarized in Table III, the detail information about up and downregulated RNAs can be viewed in Tables SI,SII,SIII,SIV,SV,SVI,SVII. The log2FC and P-value distribution of top 100 differentially expressed mRNAs were shown by heatmaps and volcano plot (Fig. 1). The heatmaps and volcano plots for miRNAs and circRNAs were presented in Figs. S1 and S2. The expression level of DEGs in homogenous samples were consistent as seen in heatmaps and the RNA expression levels in GC and normal tissue were significantly different, indicating samples used in this cohort had good uniformity and the DEGs screened were reliable. Volcano plots illustrated the log2FC values of all differentially expressed mRNAs were distributed between −6 and 6, with the majority being distributed between −3 and 3. For miRNA, log2FC values were distributed between −5 and 5 and most distributed between −1 and 1. For circRNA, log2FC values were distributed between −8 and 8, with most being distributed between −2 and 2.

Table III.

Summary of the number of DEGs in this study.

| Dataset | Type | UP_DEGs | DOWN_DEGs |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA | mRNA | 2,087 | 2,322 |

| GSE54129 | mRNA | 998 | 830 |

| TCGA | miRNA | 72 | 81 |

| GSE106817 | miRNA | 569 | 428 |

| GSE112264 | miRNA | 602 | 428 |

| GSE83521 | circRNA | 70 | 80 |

| GSE93541 | circRNA | 202 | 216 |

DEGs, differentially expressed genes; UP_, upregulated; DOWN_, downregulated; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; miRNA, microRNA; circRNA, circularRNA.

Figure 1.

DEmRNAs in gastric cancer. (A) Heatmap plot of top 100 DEmRNAs identified from TCGA dataset. Blue represents normal samples and red represents gastric cancer patients. (B) Heatmap plot of top 100 DEmRNAs identified from GSE54129 dataset. Colors as in A. (C) Volcano plots of mRNAs identified from TCGA dataset. Red and blue dots indicated up- and down-regulated mRNAs. (D) Volcano plots of mRNAs identified from GSE54129 dataset. DEmRNAs, differentially expressed mRNAs; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

WGCNA analysis

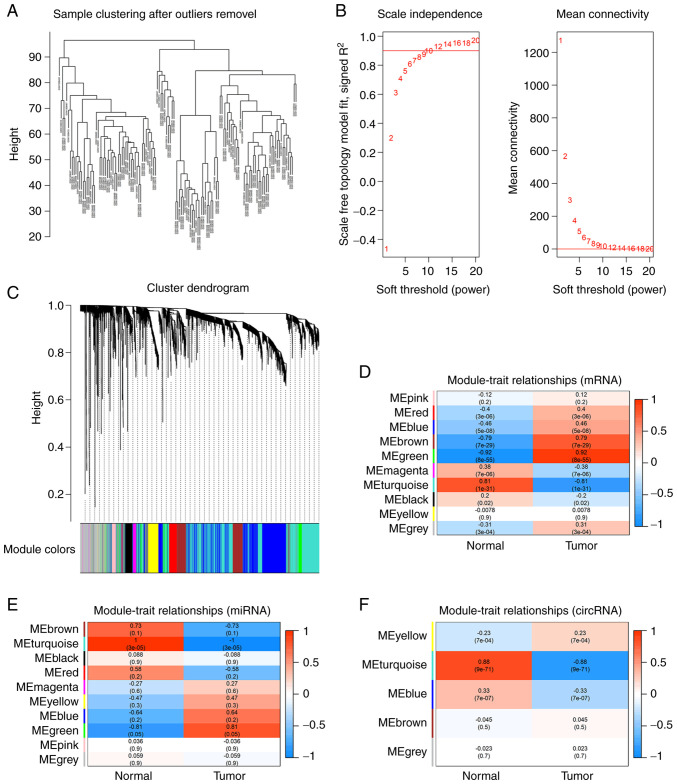

A total of 4,193 mRNAs (the top 20%) were identified in GES54129 dataset ranked by the Pearson correlation coefficient. Sample clustering analysis showed three obvious outlier samples with heights >100, the remaining samples after pruning (cutHeight=100) were reserved for following analysis. Network topological analysis indicated the appropriate power of β was 9 (Fig. 2B) and mRNAs with similar expression levels were categorized into the same module. Finally, the dataset was divided into 10 modules (Fig. 2C). The correlation analysis between phenotypes and modules indicated that green and turquoise modules were the most clinically significant (|R|>0.8, P<0.05; Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Identification of modules associated with gastric cancer by weighted correlation network analysis from GSE54129 dataset. (A) Sample clustering after outlier samples removal. (B) Screening the appropriate power of β. (C) Distribution of average mRNA significance and errors in the modules associated with gastric cancer. (D) Distribution of average mRNA significance and errors in the modules. (E) Distribution of average miRNA significance and errors in the modules. (F) Distribution of average circRNA significance and errors in the modules.

The top 50% of miRNAs (1,282) were identified in the GSE106817 dataset. Sample clustering analysis showed there were no outlier samples. Topological analysis indicated the appropriate power of β was 3. All candidate miRNAs were categorized into 5 modules (Fig. S3A-C) and turquoise was the most clinically significant (|R|>0.8, P<0.05; Fig. 2E).

The top 75% of circRNAs (1,313) were observed in GSE93541 for further analysis. Sample clustering analysis showed that there were no outlier samples. Topological network analysis showed the appropriate power of β was 7. circRNAs were classified into 10 modules (Fig. S3D-F) and turquoise was the most clinically significant module (|R|>0.8, P<0.05; Fig. 2F). The number of mRNA, miRNA and circRNA in each module were listed in Table IV.

Table IV.

Number of RNAs contained in each module in weighted correlation network analysis.

| Module | GSE54129 (mRNA) | GSE106817 (miRNA) | GSE93541 (circRNA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black | 130 | - | 49 |

| Blue | 1,110 | 87 | 312 |

| Brown | 395 | 55 | 141 |

| Green | 183 | - | 76 |

| Grey | 423 | 544 | 5 |

| Magenta | 66 | - | 35 |

| Pink | 70 | - | 45 |

| Red | 164 | - | 52 |

| Turquoise | 1,410 | 550 | 507 |

| Yellow | 242 | 46 | 91 |

miRNA, microRNA; circRNA, circularRNA.

Candidate RNAs screening

To promote the reliability and applicability of the ceRNA network, the present study took the RNAs obtained from WGCNA analysis intersected with the DEGs in TCGA and GEO datasets. The DE mRNAs in turquoise and green modules were intersected with DEGs from GSE54129 and TCGA, the DE miRNAs in the turquoise modules were intersected with GSE106817, GSE112264 and TCGA datasets. Similarly, the DE circRNAs in turquoise were intersected with GSE93541 and GSE83521 datasets. 72 mRNAs (43 upregulated and 29 downregulated), 17 miRNAs (5 upregulated and 12 downregulated) and 10 circRNAs (3 upregulated and 7 downregulated) were obtained as candidate RNAs to construct ceRNA in next step (Fig. 3). The DEGs after intersection are shown in Tables SVIII-SX.

Figure 3.

Screening hub RNAs. (A) Upset plot for mRNAs screened by differential expression analysis and weighted correlation network analysis. The red line represented upregulate hub mRNAs and the blue line represented downregulate hub mRNAs. (B) Upset plot for miRNAs. (C) Upset plot for circRNAs. circRNAs, circular RNAs; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

Construction of ceRNA network

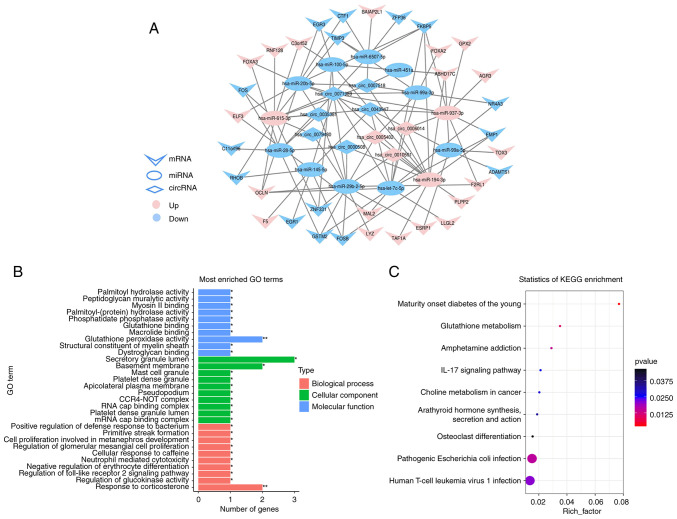

The interaction relationship between hub circRNAs, miRNAs and mRNAs were predicted. Next, the interacting connections among hub RNAs were imaged by Cytoscape software. The GC ceRNA network contained 109 edges and 56 nodes, including 13 miRNAs, 9 circRNAs and 34 mRNAs (Fig. 4A), the details of 56 node RNAs are shown in Table SXI.

Figure 4.

The ceRNA network of circRNA-miRNA-mRNA in gastric cancer and functional annotation of hub mRNA in ceRNA. (A) The view of ceRNA network which include 13 miRNAs, 9 circRNAs and 34 mRNAs. (B) The top 10 most enriched GO terms of hub mRNAs (P<0.05). (C) KEGG pathway enrichment of hub mRNAs (P<0.05). ceRNA, competing endogenous RNA; circRNAs, circular RNAs; miRNA, microRNA; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Functional annotation of hub mRNAs

GO and KEGG analyses were performed on node mRNAs identified in ceRNA network. GO enrichment analysis indicated that biological processes mainly involved in metabolism, immunity, cell proliferation and development. For cellular component, it mainly participated in the formation of transcription complex, platelet and lateral plasma membrane, etc. Molecular function mainly involved in the activity of enzymes and the binding of substances (Fig. 4B). For KEGG, there were 8 significantly enriched pathways (P<0.05), which mainly involved in metabolism and immune-related pathways, such as glutathione metabolism, pathogenic Escherichia coli infection and IL-17 signaling pathway, etc. (Fig. 4C).

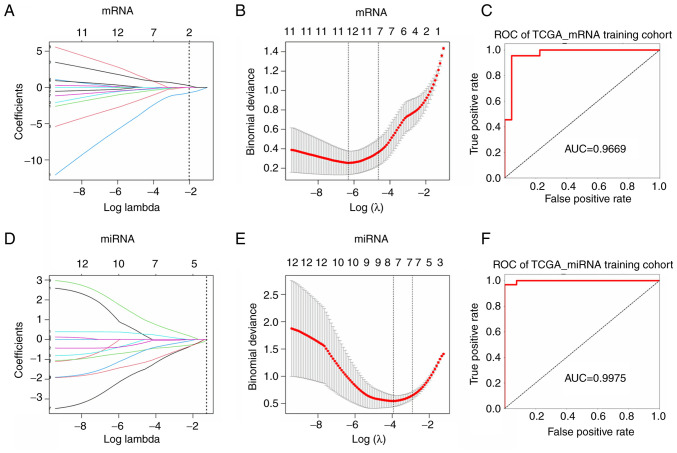

Diagnostic and prognostic signature identification

Referencing the mRNAs and miRNAs in ceRNA network, LASSO regression analysis was performed on TCGA to further screen diagnostic and prognostic signature of mRNA (Fig. 5A and B) and miRNA (Fig. 5D and E). The top 5 mRNAs were CTF1, FKBP5, RNF128, GSTM2 and ADAMTS1, the top 5 miRNA were miR-145-5p, miR-615-3p, miR-6507-5p, miR-937-3p and miR-99a-3p. The value of LASSO regression coefficient is listed in Table V.

Figure 5.

Diagnostic and prognostic signature identification and diagnostic model construction. (A) LASSO coefficient profiles of the hub mRNAs in ceRNA network. The vertical blue dotted lines are plotted at the value selected in B. (B) Selection of the tuning parameter (lambda) in the LASSO model by tenfold cross-validation based on minimum criteria for OS. the lower X axis shows log (lambda) and the upper X axis shows the average number of hub mRNAs. (C) ROC curve analysis for diagnostic model (mRNA) in TCGA training cohort. (D) LASSO coefficient profiles of the hub miRNAs in ceRNA network. (E) Selection of the tuning parameter (lambda) in the LASSO model by tenfold cross-validation based on minimum criteria for OS. the lower X axis shows log (lambda) and the upper X axis shows the average number of hub miRNAs. (F) ROC curve analysis for diagnostic model (miRNA) in TCGA training cohort. LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operation; ceRNA, competing endogenous RNA; OS, overall survival; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; miRNA, microRNA; AUC, area under curve.

Table V.

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operation regression coefficient absolute value of the top 5 RNAs.

| A, mRNA | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Symbol | β |

| GSTM2 | −3.513723131 |

| ADAMTS1 | −1.606401793 |

| FKBP5 | 1.462560621 |

| RNF128 | 1.065936307 |

| CTF1 | −0.587182395 |

|

| |

| B, miRNA | |

|

| |

| Symbol | β |

|

| |

| hsa-miR-615-3p | −0.63417029 |

| hsa-miR-937-3p | −0.58439658 |

| hsa-miR-99a-3p | 0.39320561 |

| hsa-miR-6507-5p | −0.35158869 |

| hsa-miR-145-5p | −0.18756029 |

miRNA/miR, microRNA.

Diagnostic model construction and validation

Considering the cancer and para-cancer sample imbalance in TCGA (375 vs. 32), para-cancer samples were all retained, and 32 cancer samples were randomly selected from 375, then 64 samples were randomly assigned to training group (44 samples) and internal validation group (20 samples) according to ratio of 7:3. The expression data of the top 5 mRNAs from training group were entered into the training model. Following 5-fold cross validation, the optimal penalty C was set as 3.0702, gamma was set as 1.2648 and kernel was set as rbf. Model accuracy (ACC) was 0.91 and area under curve (AUC) value was 0.9669 (Fig. 5C). Then the internal validation showed ACC was 0.95 and the AUC value was 1.0000 (Fig. S4A). To further validate the robustness of the model and diagnostic ability of candidate mRNAs, 21 pairs of cancerous and non-cancerous samples from the GSE54129 dataset and all samples from GTEx and TCGA datasets were used as external data to further verify the model. The results showed ACC and AUC values of these two datasets are both greater than 0.8 (Fig. S4B and C). The above results indicated that the 5 characteristic mRNA had strong ability to distinct gastric cancer from non-cancer.

For miRNA, 41 cancer samples from TCGA GC dataset (41/436) were selected randomly to balance 41 para-cancer samples, 82 samples were randomly assigned to the training group (57 samples) and the internal validation group (25 samples) according to ratio of 7:3. The expression data of the 5 signature miRNAs from the training group were entered into the model for training and the optimal penalty C was set as 3.0702, gamma was set as 1.2648 and kernel was set as rbf. Results indicated ACC was 0.93 and AUC value was 0.9975 (Fig. 5F). Internal validation group indicated the ACC was 0.92 and AUC value was 0.9733 (Fig. S4D). GSE106817 and GSE112264 datasets were used as external validation data and results showed that the ACC and AUC values of these two datasets are both more than 0.8 (Fig. S4E and F) (25,26).

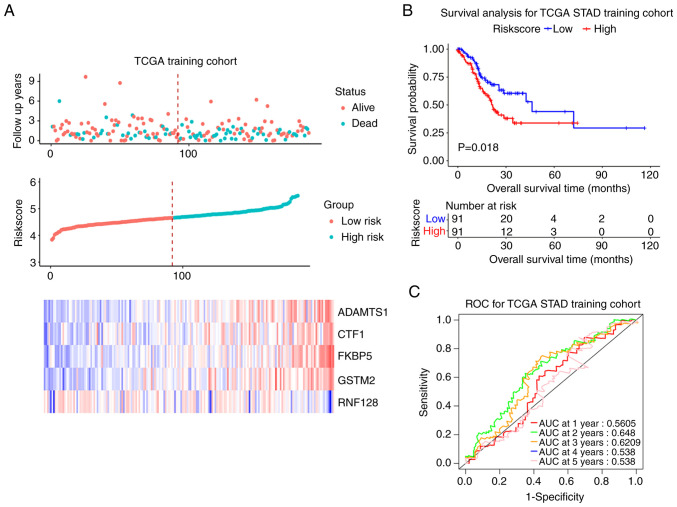

Prognostic model construction and validation

Patients with both overall survival (OS) information and expressed data of the 5 candidate mRNAs were selected and finally 375 cases were recruited. The results of Univariate Cox regression analysis are summarized in Table VI. The 375 samples were randomly divided into training and test cohort (188 vs. 187). In training cohort, the median RiskScore value was taken as the cutoff point (4.664). Patients with RiskScore >4.664 were defined as a high-risk group (94 cases) and those with RiskScore ≤4.664 were defined as a low-risk group. The survival status, RiskScore, candidate genes expression levels and the survival curves of training cohort were shown in Fig. 6A. The prognosis of the high-risk group was worse compared with that of low-risk group (P<0.05; Fig. 6B). The ROC curve showed that the signature had good prognosis accuracy for 1–5 years in the training test, the AUC values were >0.5 (Fig. 6C). The same trend was seen from both the test set and the entire set (P<0.05; AUC >0.5; Figs. S5 and S6).

Table VI.

Univariate Cox regression analysis of RNAs.

| Symbol | β | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Wald test | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADAMTS1 | 0.065 | 1.1 (0.94-1.2) | 0.94 | 0.33 |

| CTF1 | 0.054 | 1.1 (0.95-1.2) | 1 | 0.31 |

| FKBP5 | 0.15 | 1.2 (0.99-1.4) | 3.4 | 0.067 |

| GSTM2 | 0.13 | 1.1 (0.97-1.3) | 2.5 | 0.11 |

| RNF128 | 0.056 | 1.1 (0.94-1.2) | 0.93 | 0.34 |

| miR-145-5p | 0.13 | 1.1 (1-1.3) | 6.8 | 0.0091 |

| miR-615-3p | −0.045 | 0.96 (0.88-1) | 1.1 | 0.29 |

| miR-6507-5p | 0.2 | 1.2 (0.93-1.6) | 2.1 | 0.14 |

| miR-937-3p | −0.054 | 0.95 (0.86-1) | 1.2 | 0.28 |

| miR-99a-3p | 0.11 | 1.1 (1-1.2) | 5.9 | 0.015 |

Figure 6.

Prognostic model (mRNAs) construction in TCGA training cohort. (A) The overall survival status, RiskScore, five-mRNAs-based prognostic signature expression levels. (B) Survival curve of low- and high-risk groups in training cohort. (C) Time-dependent ROC curve comparison of the TCGA training cohort. AUCs at 1–5 years were calculated. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under curve; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma.

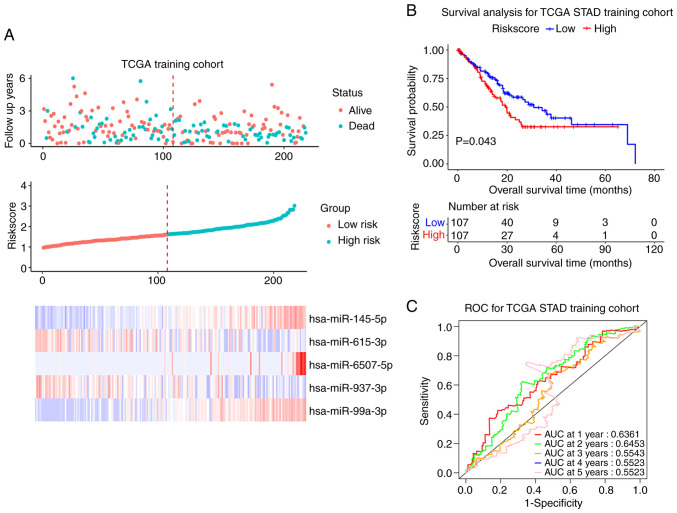

For miRNA, the present study used the same validation method as for mRNA; 436 patients with OS information were finally recruited. The results of Univariate Cox regression analysis are summarized in Table VI. The 436 samples were randomly divided into the training set and the test set (218 vs. 218) according to ratio of 1:1. The median value of RiskScore was 1.621. The training cohort was divided into a high-risk group (RiskScore >1.621) and a low-risk group (RiskScore ≤1.621). Survival status, RiskScore value, candidate miRNAs expression levels and the survival curve in the training cohort are shown in Fig. 7A. The prognosis of high-risk patients was worse compared with that of low-risk patients (P<0.05; Fig. 7B). The ROC curve showed that the miRNA signature had good prognosis accuracy for 1–5 years in the training test, the AUC values were >0.5 (Fig. 7C). The same conclusion was also obtained from the test set and the entire sample set (Figs. S7 and S8).

Figure 7.

Prognostic model (miRNAs) construction in TCGA training cohort. (A) The overall survival status, RiskScore, five-miRNAs-based prognostic signature expression levels. (B) Survival curve of low- and high-risk groups in training cohort. (C) Time-dependent ROC curve comparison of the TCGA training cohort. AUCs at 1–5 years were calculated. miRNA, microRNA; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under curve; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma.

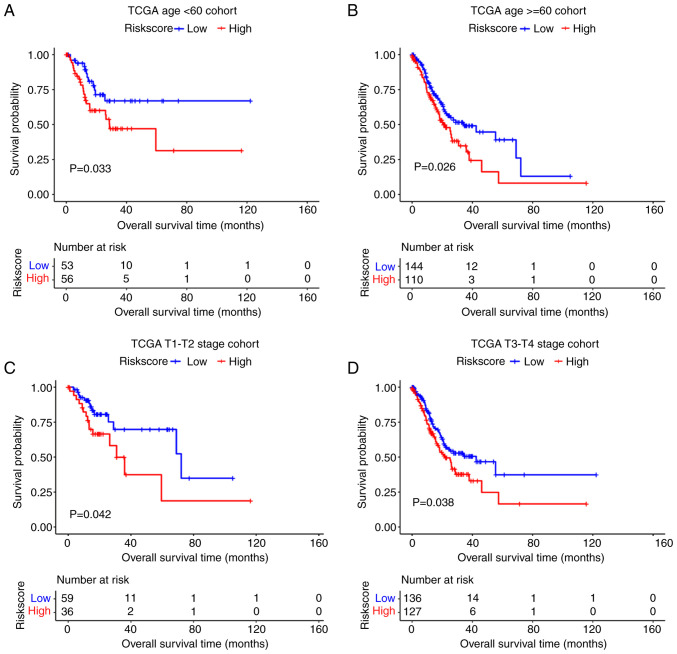

Stratified analysis of the prognostic signature

The present study investigated the predictive power of the mRNA prognostic model in different clinical subgroups in TCGA dataset. The results showed that the prognostic model had good predictive power t in subgroups <65 and ≥65, T1-T2 and T3-T4 (P<0.05; Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Stratified analysis of prognostic model (mRNAs) in the TCGA dataset. The high-risk group showed a poor prognosis than the low-risk group in several clinical stratification such as (A and B) age and (C and D) T stage. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma.

Discussion

Accumulating high-throughput sequencing evidence has revealed that global transcriptome deregulation is associated with tumorigenesis and the development of GC. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying gastric carcinogenesis remain to be elucidated. The present study explored the circRNA-miRNA-mRNA interacting axis by constructing ceRNA network. Finally, the visible network contained 109 edges and 56 nodes, of which 34 mRNAs, 13 miRNAs and 9 circRNAs were included. Several promising interacting axes, such as circ_0007518/ circ_0071989-miR-6507-5p-CTF1 were further identified and the RNAs, including circRNA, miRNA and mRNA, identified in these axes provided a basis and direction for further mechanism research.

Based on the hub RNAs involved in ceRNA, LASSO regression analysis was performed to screen the prediction model of mRNA signature and miRNA signature. This indicated that both the 5 mRNA-based signature (CTF1, FKBP5, RNF128, GSTM2 and ADAMTS1) and 5 miRNA-based signature (miR-145-5p, miR-615-3p, miR-6507-5p, miR-937-3p and miR-99a-3p) had good prediction capacity of diagnosis and prognosis for GC patients. The use of LASSO regression analyses allowed for more automated setting of weights to zero, which was needed for this high-dimensional data. Additionally, LASSO allowed for easy interpretation of the data that enabled the present study to screen quickly for the most crucial information in the model (27,28). Yan et al (29) successfully built a more extensive ceRNA network for hepatocellular carcinoma and identified 4 gene-based signatures (PBK, CBX2, CLSPN and CPEB 3) using a LASSO regression model, which predicted the overall survival of hepatocellular carcinoma effectively. Li et al (30) also used LASSO regression analysis to screen an immune-related prognostic signature involving 24 genes to predict the OS and immune status in colorectal cancer, which was conducive to better stratification and more precise immunotherapy for patients.

Only the CTF1 gene identified in this cohort were reported in GC research, Pan et al (31) reported that CTF1 combining with BTN3A3 and ADA2 genes as a prognostic model to predict the survival state of GC patients with fluorouracil-bases chemotherapy and help clinicians develop personalized treatment. By contrast, studies on the pathogenesis of GC concerning the CTF1 gene have not been reported. The other mRNAs identified in the present study that have been reported in studies not related to GC include FK506 binding protein 5 (FKBP5); a regulatory protein of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which mainly has functions in various stress-related psychiatric disorders and which is seldom reported in GC (32). In in vitro experiments, Zou et al (33) demonstrated that GSTM2 might correlated with the cisplatin resistance of GC cells. A disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS) is a family of 19 secreted membrane-anchored proteases, Kilic et al (34) reported that ADAMTS1 protease was highly expressed in GC and nodal metastases, indicating important role in carcinogenesis and lymphatic metastasis, however the specific regulatory mechanism of ADAMTS1 has not been studied.

In the cohort of the present study, the combination of 5 miRNAs identified could distinguish GC patients from the healthy controls and predict survival when patients were placed into high-risk or low-risk groups according to their risk value. miRNAs are small endogenous non-coding regulatory RNAs, which take a vital part in the progression of tumor by depredating the target mRNA, while circRNA functions as an miRNA sponge to regulate selective splicing, expression and translation of host genes through endogenous competing miRNA (35–38). In GC, multiple miRNAs are differentially expressed and showed evidence of a function in tumorigenesis. Zhong et al (39) revealed that the expression levels of miR-145-5p are significantly decreased in GC cells and correlate with the expression of KCNQ1OT1 in tumors, which promotes disease progression through the miR-145-5p/ARF6 axis. Wang et al (40) report that miR-615-3p promotes GC proliferation and migration by deregulating CELF2 expression in vitro and in vivo. The visible competing network in the present study displayed the interacting control between hub RNAs and the specific regulatory link between the mentioned RNAs have not been reported as so far, which will be the direction for further research.

miRNAs are found in serum, plasma and other body fluids because of their ability to avoid degradation, therefore, they become an ideal noninvasive biomarker to diagnose and predict survival rates. The 5-miRNA signature reported in the present study has promising clinical application. The miRNA biomarker panel assay was also found by other studies, So et al (11) recently developed a valid risk assessment tool composed of 12 serum miRNAs able to detect GC. Similarly, Japanese studies by Abe et al (41) developed a novel combination of four serum miRNAs (miR-4257, miR-6785-5p, miR-187-5p and miR-5739) to discriminate early GC from normal tissue lesions with high accuracy. The present study performed a similar analysis on circRNA with the expectation of constructing a prediction model of it, but the limited sample size of the original circRNA datasets hampered the panel which did not display strong diagnostic and prognostic capacity. Although the present study designed internal and external validations, it also had some limitations, including the fact that all conclusions were obtained from already published bioinformatic data and the lack of in vitro validation experiments; the functional mechanism study was the main direction of the present study.

In conclusion, the present study constructed ceRNA network of gastric cancer using circRNA, miRNA and mRNA public datasets, and the interaction between hub RNAs provided the basis for the further molecular pathogenesis research. In addition, the present study developed and validated 5 mRNA-based signature and 5 miRNA-based signature that have the potential to be useful tools to diagnose GC in patients and to predict their survival rates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Science Foundation of Guangzhou First People's Hospital (grant no. M2019002).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

WD, HD designed the study and confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. WD drafted the manuscript, tables, and figures. LW, XL, LC, GL performed the bioinformatic analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Guangzhou First People's Hospital (approval no. K-2020-010-01)

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Bray F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:1941–1953. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young E, Philpott H, Singh R. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of gastric dysplasia and early cancer: Current evidence and what the future may hold. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:5126–5151. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i31.5126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang H, Leung C, Saito E, Katanoda K, Hur C, Kong CY, Nomura S, Shibuya K. Effect and cost-effectiveness of national gastric cancer screening in Japan: A microsimulation modeling study. BMC Med. 2020;18:257. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01729-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suh Y, Lee J, Woo H, Shin D, Kong SH, Lee HJ, Shin A, Yang HK. National cancer screening program for gastric cancer in Korea: Nationwide treatment benefit and cost. Cancer. 2020;126:1929–1939. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van Grieken NC, Lordick F. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2020;396:635–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Sethi NS, Hinoue T, Schneider BG, Cherniack AD, Sanchez-Vega F, Seoane JA, Farshidfar F, Bowlby R, Islam M, et al. Comparative molecular analysis of gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:721–735.e728. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimozaki K, Nakayama I, Takahari D, Kamiimabeppu D, Osumi H, Wakatsuki T, Ooki A, Ogura M, Shinozaki E, Chin K, Yamaguchi K. A novel clinical prognostic index for patients with advanced gastric cancer: Possible contribution to the continuum of care. ESMO Open. 2021;6:100234. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu C, Ren C, Han J, Ding Y, Du J, Dai N, Dai J, Ma H, Hu Z, Shen H, et al. A five-microRNA panel in plasma was identified as potential biomarker for early detection of gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2291–2299. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen D, Ping S, Xu Y, Wang M, Jiang X, Xiong L, Zhang L, Yu H, Xiong Z. Non-coding RNAs in gastric cancer: From malignant hallmarks to clinical applications. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:732036. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.732036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.So J, Kapoor R, Zhu F, Koh C, Zhou L, Zou R, Tang YC, Goo PC, Rha SY, Chung HC, et al. Development and validation of a serum microRNA biomarker panel for detecting gastric cancer in a high-risk population. Gut. 2021;70:829–837. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imaoka H, Toiyama Y, Okigami M, Yasuda H, Saigusa S, Ohi M, Tanaka K, Inoue Y, Mohri Y, Kusunoki M. Circulating microRNA-203 predicts metastases, early recurrence, and poor prognosis in human gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:744–753. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madar V, Batista S. FastLSU: A more practical approach for the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR controlling procedure for huge-scale testing problems. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1716–1723. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rehmsmeier M, Steffen P, Hochsmann M, Giegerich R. Fast and effective prediction of microRNA/target duplexes. RNA. 2004;10:1507–1517. doi: 10.1261/rna.5248604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sticht C, De La Torre C, Parveen A, Gretz N. miRWalk: An online resource for prediction of microRNA binding sites. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0206239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics. 2012;16:284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw. 2010;33:1–22. doi: 10.18637/jss.v033.i01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bac J, Mirkes EM, Gorban AN, Tyukin I, Zinovyev A. Scikit-Dimension: A python package for intrinsic dimension estimation. Entropy (Basel) 2021;23:1368. doi: 10.3390/e23101368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daberdaku S, Ferrari C. Antibody interface prediction with 3D Zernike descriptors and SVM. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:1870–1876. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baldi P, Brunak S, Chauvin Y, Andersen CA, Nielsen H. Assessing the accuracy of prediction algorithms for classification: An overview. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:412–424. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.5.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiong Y, Wang R, Peng L, You W, Wei J, Zhang S, Wu X, Guo J, Xu J, Lv Z, Fu Z. An integrated lncRNA, microRNA and mRNA signature to improve prognosis prediction of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:85463–85478. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yokoi A, Matsuzaki J, Yamamoto Y, Yoneoka Y, Takahashi K, Shimizu H, Uehara T, Ishikawa M, Ikeda SI, Sonoda T, et al. Int extracellular microRNA profiling for ovarian cancer screening. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4319. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06434-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urabe F, Matsuzaki J, Yamamoto Y, Kimura T, Hara T, Ichikawa M, Takizawa S, Aoki Y, Niida S, Sakamoto H, et al. Large-scale circulating microRNA profiling for the liquid biopsy of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:3016–3025. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren S, Huang S, Ye J, Qian X. Safe feature screening for generalized LASSO. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2018;40:2992–3006. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2017.2776267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waldmann P, Ferenčaković M, Mészáros G, Khayatzadeh N, Curik I, Sölkner J. AUTALASSO: An automatic adaptive LASSO for genome-wide prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2019;20:167. doi: 10.1186/s12859-019-2743-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan Y, Lu Y, Mao K, Zhang M, Liu H, Zhou Q, Lin J, Zhang J, Wang J, Xiao Z. Identification and validation of a prognostic four-genes signature for hepatocellular carcinoma: Integrated ceRNA network analysis. Hepatol Int. 2019;13:618–630. doi: 10.1007/s12072-019-09962-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li M, Wang H, Li W, Peng Y, Xu F, Shang J, Dong S, Bu L, Wang H, Wei W. Identification and validation of an immune prognostic signature in colorectal cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88:106868. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan J, Dai Q, Xiang Z, Liu B, Li C. Three biomarkers predict gastric cancer patients' susceptibility to fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. J Cancer. 2019;10:2953–2960. doi: 10.7150/jca.31120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang JI, Chung HC, Jeung HC, Kim SJ, An SK, Namkoong K. FKBP5 polymorphisms as vulnerability to anxiety and depression in patients with advanced gastric cancer: A controlled and prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:1569–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou M, Hu X, Xu B, Tong T, Jing Y, Xi L, Zhou W, Lu J, Wang X, Yang X, Liao F. Glutathione S-transferase isozyme alpha 1 is predominantly involved in the cisplatin resistance of common types of solid cancer. Oncol Rep. 2019;41:989–998. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kilic M, Aynekin B, Kara A, Icen D, Demircan K. Differentially regulated ADAMTS1, 8, and 18 in gastric adenocarcinoma. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2017;118:71–76. doi: 10.4149/BLL_2017_014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu L, Tian YC, Mao G, Zhang YG, Han L. MiR-675 is frequently overexpressed in gastric cancer and enhances cell proliferation and invasion via targeting a potent anti-tumor gene PITX1. Cell Signal. 2019;62:109352. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2019.109352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartel D. Metazoan microRNAs. Cell. 2018;173:20–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slack FJ, Chinnaiyan AM. The role of non-coding RNAs in oncology. Cell. 2019;179:1033–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dragomir M, Calin GA. Circular RNAs in cancer-lessons learned from microRNAs. Front Oncol. 2018;8:179. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhong X, Wen X, Chen L, Gu N, Yu X, Sui K. Long non-coding RNA KCNQ1OT1 promotes the progression of gastric cancer via the miR-145-5p/ARF6 axis. J Gene Med. 2021;23:e3330. doi: 10.1002/jgm.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40.Wang J, Liu L, Sun Y, Xue Y, Qu J, Pan S, Li H, Qu H, Wang J, Zhang J. miR-615-3p promotes proliferation and migration and inhibits apoptosis through its potential target CELF2 in gastric cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;101:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.02.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abe S, Matsuzaki J, Sudo K, Oda I, Katai H, Kato K, Takizawa S, Sakamoto H, Takeshita F, Niida S, et al. A novel combination of serum microRNAs for the detection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2021;24:835–843. doi: 10.1007/s10120-021-01161-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.