Abstract

Background

Prediction tools without patient-reported symptoms could facilitate widespread identification of OSA.

Research Question

What is the diagnostic performance of OSA prediction tools derived from machine learning using readily available data without patient responses to questionnaires? Also, how do they compare with STOP-BANG, an OSA prediction tool, in clinical and community-based samples?

Study Design and Methods

Logistic regression and machine learning techniques, including artificial neural network (ANN), random forests (RF), and kernel support vector machine, were used to determine the ability of age, sex, BMI, and race to predict OSA status. A retrospective cohort of 17,448 subjects from sleep clinics within the international Sleep Apnea Global Interdisciplinary Consortium (SAGIC) were randomly split into training (n = 10,469) and validation (n = 6,979) sets. Model comparisons were performed by using the area under the receiver-operating curve (AUC). Trained models were compared with the STOP-BANG questionnaire in two prospective testing datasets: an independent clinic-based sample from SAGIC (n = 1,613) and a community-based sample from the Sleep Heart Health Study (n = 5,599).

Results

The AUCs (95% CI) of the machine learning models were significantly higher than logistic regression (0.61 [0.60-0.62]) in both the training and validation datasets (ANN, 0.68 [0.66-0.69]; RF, 0.68 [0.67-0.70]; and kernel support vector machine, 0.66 [0.65-0.67]). In the SAGIC testing sample, the ANN (0.70 [0.68-0.72]) and RF (0.70 [0.68-0.73]) models had AUCs similar to those of the STOP-BANG (0.71 [0.68-0.72]). In the Sleep Heart Health Study testing sample, the ANN (0.72 [0.71-0.74]) had AUCs similar to those of STOP-BANG (0.72 [0.70-0.73]).

Interpretation

OSA prediction tools using machine learning without patient-reported symptoms provide better diagnostic performance than logistic regression. In clinical and community-based samples, the symptomless ANN tool has diagnostic performance similar to that of a widely used prediction tool that includes patient symptoms. Machine learning-derived algorithms may have utility for widespread identification of OSA.

Key Words: artificial neural network, electronic medical record, kernel support vector machine, machine learning, OSA, prediction model, random forest

Abbreviations: ANN, artificial neural network; AUC, area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve; EMR, electronic medical record; IRB, Institutional Review Board; KSVM, kernel support vector machine; LOG, logistic regression; Plog, predicted probability of logistic regression model; PSG, polysomnography; RF, random forests; ROC, receiver-operating characteristic

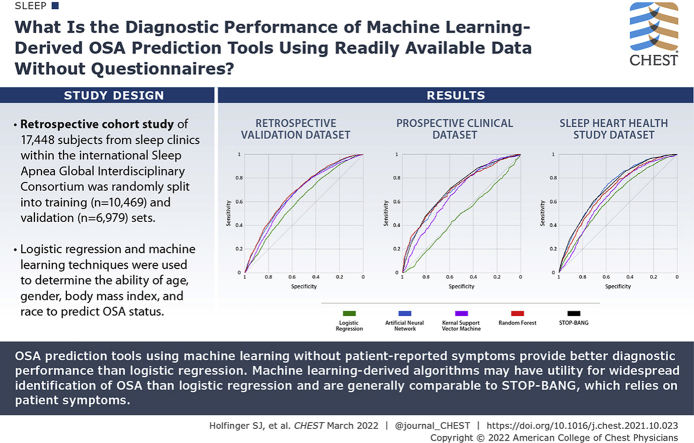

Graphical Abstract

Take-home Points.

Research Question: What is the diagnostic performance of machine learning-derived OSA prediction tools using readily available data without patient responses to questionnaires, and how do they compare to the STOP-BANG tool in clinical and community-based samples?

Results: OSA prediction tools using machine learning without patient-reported symptoms provide better diagnostic performance than the LOG model. In clinical and community-based samples, the symptomless ANN tool has similar diagnostic performance to the STOP-BANG questionnaire, a widely used prediction tool that includes patient symptoms.

Interpretation: Machine learning-derived algorithms may have utility for a more widespread identification of OSA.

Prediction tools that determine the likelihood of OSA generally include patient-reported symptoms.1, 2, 3, 4 However, responses to symptom questionnaires may be unavailable or inaccurate. For example, individuals whose livelihood will be negatively affected by an OSA diagnosis, such as commercial truck drivers, may be less likely to report symptoms accurately.5 In addition, patient-reported symptoms are unlikely to be available for OSA identification in large groups of individuals using electronic medical records (EMRs) and may not be harmonized across institutions. Thus, novel OSA prediction tools that do not require patient-reported symptoms would fill a critical gap in the identification of OSA risk.

Toward this end, previous studies have shown that a symptomless prediction score using age, sex, and BMI as inputs to a logistic regression (LOG) model has some utility in risk stratification for OSA.6 Moreover, using data from 40,432 elective inpatient surgeries, we have shown that this score correlates with higher risk for selected postoperative complications.7

Machine learning algorithms offer advantages in detecting more complex, nonlinear relationships among predictors and outcomes compared with LOG.8,9 These algorithms devise a set of rules from training data with known input (eg, age, sex, BMI) and output (eg, presence or absence of OSA) values and apply the rules to a new set of data.8 Our group previously published that an OSA prediction tool using an artificial neural network (ANN) that included symptom responses provided better diagnostic performance compared with LOG.4 Whether machine learning prediction models that do not include patient-reported symptoms perform as well as those with symptoms has not been studied, to our knowledge, in large clinical and community-based samples.

Using a big data approach, our first aim was to develop a novel prediction tool for moderate to severe OSA risk without requiring patient-reported symptoms using three machine learning methods (ANN, random forests [RFs], and kernel support vector machine [KSVM]). We sought to compare the diagnostic performance of the prediction tools vs a symptomless LOG model in a large retrospective dataset from the international Sleep Apnea Global Interdisciplinary Consortium (SAGIC).10, 11, 12, 13 We hypothesized that these machine learning methods would outperform LOG. Our second aim was to assess the diagnostic performance of the machine learning models and compare them vs a widely used OSA prediction tool that includes patient-reported symptoms (STOP-BANG)14 within a large independent prospective clinical sample from SAGIC and a large community-based sample from the Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS).15 We hypothesized that the symptomless machine learning models would have similar or greater diagnostic accuracy than the STOP-BANG questionnaire in both clinical and community-based samples.

Study Design and Methods

Additional details regarding the study methods are provided in e-Appendix 1.

Retrospective Dataset

The retrospective dataset consisted of de-identified data and sleep study variables from subjects who underwent in-laboratory polysomnography (PSG) for clinical suspicion of OSA in five SAGIC sleep centers (The Ohio State University, University of Pennsylvania [Penn], Western Australia [Perth], Sydney, and Taiwan). The retrospective study obtained approval from The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board (IRB protocol number 2014H0389).

PSGs were recorded and scored at each site following the guidelines of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and using locally available equipment. Hypopneas used a nasal pressure signal excursion drop by ≥ 30% from baseline associated either with a ≥ 4% desaturation (Ohio site) or a ≥ 3% desaturation and/or an arousal (Penn, Perth, Sydney, and Taiwan sites). Of the 17,731 individuals in the retrospective dataset, those with complete data for analysis (N = 17,448) were randomly split into a training dataset with 60% of the subjects (n = 10,469) and a validation dataset with the remaining 40% (n = 6,979).10

Prospective Cohorts

Data from two previously collected, independent prospective cohorts (clinical and community-based) were used for testing of the trained machine learning predictions derived from the retrospective dataset, as described in the following sections.

Clinical Dataset

An independent sample of prospective subjects was recruited from the SAGIC sleep centers. The inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 years, suspicion of OSA, and conduct of an in-laboratory PSG according to standard procedures. Sleep parameter scoring is as described for the retrospective dataset; hypopneas in all sleep centers were scored by using a 4% desaturation criteria.16 We previously published data showing a strong inter-rater agreement among the SAGIC centers for PSG scoring of sleep and respiratory events.17 The prospective study protocol was approved by the IRB at the University of Pennsylvania (IRB protocol number 820563), and additional IRB approvals were obtained at each site. Informed consent was obtained from all prospective participants.

Of the 1,618 subjects in the prospective SAGIC cohort, 1,613 had complete data and were included. A STOP-BANG score was computed for all subjects using previously described methods.3,14 Briefly, the score for the STOP-BANG was calculated by assigning a score of 1 for each positive answer to snoring, tiredness, being observed to stop breathing during sleep, high BP, BMI > 35 kg/m2, age > 50 years, neck circumference > 40 cm, and male sex. A positive STOP-BANG was determined as a score of ≥ 3.14

Community-Based Dataset

Data from 5,804 adults who completed an in-home PSG in SHHS were downloaded with permission from the National Sleep Research Resource (https://sleepdata.org/).15 Details of the SHHS methodology have been previously described.15,18 Of the 5,804 potential subjects, 5,599 (96.5%) had data needed for both the STOP-BANG analysis and machine learning predictive models. The SHHS included patients aged ≥ 40 years enrolled between November 1, 1995, and January 31, 1998, from nine sites within the United States. PSG scoring followed American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines, and the apnea-hypopnea index was calculated using hypopneas associated with a ≥ 4% desaturation.

Race in the SHHS was reported as white, black, or other. Too few Asian participants were enrolled to allow anonymous reporting per the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute data repository guidelines, and these patients were therefore grouped in the other category.19 We computed a STOP-BANG score for all subjects as described earlier using surrogate variables from the SHHS intake questionnaire to approximate the STOP-BANG questions, as previously published.20

Symptomless OSA Prediction Models

Symptomless OSA prediction models were developed by using the retrospective dataset, with age, sex, BMI, and race as inputs. The outcome was OSA status, with a case defined as an apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 15 events/hour given our focus on determining moderate to severe OSA risk.

LOG-predicting OSA status was fit to the retrospective SAGIC training set, including age, sex, BMI, and race, as well as pairwise interactions between age, sex, and BMI.2,7 The logistic model predicted probability (Plog) was calculated as: Plog = eX/(1 + eX), where X = −3.681 + 0.091 × (BMI) + 0.047 × (age) + 0.328 × (sex: 0 = female, 1 = male) – 0.000328 (age∗BMI) + 0.001 (age∗male) – 0.026 (BMI∗male) + 0.00 × Caucasian + 0.468 × African American + 0.221× Asian + 0.136 × Other. Thus, Plog ranges from 0 to 1, with larger values indicating a higher predicted probability of OSA. SPSS version 25 (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation) was used to derive the coefficients for the LOG model.

For the ANN, we used a neural network based on the cascade correlation algorithm of Fahlman (NeuroShell Classifier, Ward Systems Group Inc.).4,21,22 Cascade correlation starts with a simple neural network that progressively adds hidden nodes when improvement in network training stalls. Each hidden node captures the prior state of the model by connecting with and freezing the weights of predictive variables and previous nodes, followed by restarting training and adding subsequent hidden nodes. This process progressively adds depth to the ANN, as each hidden node adds a new feature detector.

We also used RF,23 an ensemble algorithm that leverages collections of decision tree models. During each iteration, each tree node is split according to the values of predictor variables, and the prediction performance (“out-of-bag” error) is evaluated in an independent subset of the training data. The predictions of each decision tree are aggregated by majority vote. We optimized prediction performance using a random grid search strategy for relevant hyper-parameters and 10-fold cross-validation in the training data. Our optimized model included 527 trees, terminal nodes with at least two observations, and a maximum node depth of 7. The R package randomForestSRC24 was used to train the RF models. These analyses were implemented in R (version 3.5.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and managed by using the package mlr.25

Finally, a KSVM discriminative classifier with a Gaussian radial basis function as the kernel function was used to predict OSA status. KSVM outputs an optimal hyperplane in an N-dimensional space, where N is the number of predictors that separates observations according to training examples.26 In this technique, a 10-fold cross-validation was used to optimize model parameters with the regularization term, C = 0.5, the inverse kernel width, sigma = 10, and tolerance of termination criterion, tol = 0.011, then used to train the SVM. The R package kernlab27 was used to train the KSVM. These analyses were implemented in R (version 3.5.1) and managed by using the package mlr.25

Statistical Analysis

To understand model discrimination, we constructed a receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve from the pairs of model output and actual OSA status (1 = with OSA; 0 = no OSA). As the primary analyses, the area under the ROC (AUC) and CIs were calculated and compared by using the pROC plug-in for R (www.r-project.org), a package specifically dedicated to ROC analysis.28 AUCs of the machine learning tools (ANN, RF, and KSVM) were compared vs the results of LOG in the retrospective SAGIC dataset. Without further training of the machine leaning tools, their AUCs in the prospective testing datasets (SAGIC and SHHS) were compared vs those of the STOP-BANG questionnaire. The STOP-BANG questionnaire was chosen as a comparator given its wide clinical use and the availability of relevant questions in both the SAGIC and SHHS datasets.

The optimal cut-point for predicting OSA status was defined as the point closest to the top left of the ROC curve for the LOG model (Plog ≥ 0.6); 0.5 for the ANN, RF, and KSVM models; and a score of ≥ 3 for the STOP-BANG questionnaire. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio, and negative likelihood ratio were also calculated and compared in secondary analyses. To test the equality of multiple sensitivities and specificities of the prediction tools, we used Cochran’s Q applied to patients with or without OSA. The alternative hypothesis was that at least two sensitivities (or specificities) were different. The rejection of the Cochran’s Q null hypothesis was followed by pairwise comparisons using McNemar’s test. The comparisons of the positive and negative predictive values were based on the method of Moskowitz and Pepe.29 The positive and negative likelihood ratios were compared by using the method of Nofuentes and de Dios Luna Del Castillo when more than two binary diagnostic tests were applied to the same sample.30 All secondary analyses were accomplished by using BDT comparator software (http://code.google.com/p/bdtcomparator/),4,31, 32, 33 and all P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons by using the Holm’s procedure.34 Unless otherwise noted, continuous variables were summarized by using means and SDs, and categorical variables were summarized by using frequencies and percentages.

Decision curves are useful for determining clinical utility of prediction models.35,36 The threshold probability is a subjectively determined cutoff based on risks and benefits of further testing vs not testing. In this context, a 10% threshold probability would mean that a patient would choose to undergo PSG if there is a ≥ 10% chance that they have moderate to severe OSA. The net benefit is a representation of the expected benefits (true positives) vs harms (false negatives adjusted by Pt).35 Net benefit analysis of the models35 at the optimal cut-points and calibration plots37 were created by using MATLAB (R2020a Update 2; MathWorks). Details of calibration plots are included in e-Appendix 1.

Results

Except for very minor differences in age, subjects in the retrospective training (n = 10,469) and validation (n = 6,979) datasets had similar characteristics (Table 1). The subjects were, on average, middle-aged and obese, with near-equal sex distribution (48% male). The race distribution was also similar in both groups. Importantly, the occurrence of moderate to severe OSA was similar in both groups.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Subjects in the Retrospective Dataset Used for Machine Learning Model Training and Validation

| Variable | Retrospective Dataset |

P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Set | Validation Set | ||

| No. | 10,469 | 6,979 | |

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 50.6 ± 14.4 | 51.1 ± 14.4 | .025 |

| BMI, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 32.7 ± 8.6 | 32.6 ± 8.5 | .450 |

| Male sex | 5,026 (48.0%) | 3,372 (48.3%) | .709 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 8,008 (76.5%) | 5,341 (76.5%) | .948 |

| African American | 1,131 (10.8%) | 743 (10.6%) | .948 |

| Asian | 891 (8.5%) | 608 (8.7%) | .948 |

| Other | 439 (4.2%) | 287 (4.1%) | .948 |

| AHI, mean ± SD, events/h | 26.8 ± 28.1 | 26.7 ± 27.8 | .817 |

| OSA prevalence AHI ≥ 15 events/h | 53.5% (n = 5,597) | 53.2% (n = 3,710) | .709 |

AHI = apnea-hypopnea index.

P value from the Student t test (for continuous data), two-proportion z test (for categorical data), or a χ2 test (race). P value in bold if < .05.

For the prospective testing datasets, the clinical SAGIC population was also on average middle-aged (50.1 ± 14.1 years) and obese (BMI, 30.9 ± 8.1 kg/m2) but predominately male (64.0%) (Table 2). Similar to other clinical datasets from SAGIC, about one-half of the subjects had moderate to severe OSA. Most were Caucasian (45.3%), with a higher percentage of Asian subjects (43.1%) compared with the other datasets. In comparison, the community-based SHHS was relatively older (63.3 ± 11.2 years), less overweight (BMI, 28.2 ± 5.1 kg/m2), and had a greater proportion of female subjects (52.8%). The majority were Caucasian (85.4%), followed by African American (8.1%), and Other (6.5%), which included a small proportion of Asian subjects. As expected, the occurrence of moderate to severe OSA in the SHHS dataset (21.2%) was less than the prospective SAGIC group (53.5%). A comparison of demographic data between those with and without moderate to severe OSA is presented in e-Table 1.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Subjects in the Prospective Datasets Used for Machine Learning Model Testing and Comparison With STOP-BANG

| Variable | Prospective Dataset |

P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAGIC | SHHS | ||

| No. | 1,613 | 5,599 | |

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 50.1 ± 14.1 | 63.3 ± 11.2 | < .001 |

| BMI, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 30.9 ± 8.1 | 28.2 ± 5.1 | < .001 |

| Male sex | 1,033 (64.0%) | 2,673 (47.7%) | < .001 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 730 (45.3%) | 4,783 (85.4%) | < .001 |

| African American | 87 (5.4%) | 454 (8.1%) | < .001 |

| Other | 100 (6.2%) | 362 (6.5%) | < .001 |

| Asian | 693 (43.1%) | NAb | … |

| AHI, mean ± SD, events/h | 27.7 ± 28.5 | 10.2 ± 13.6 | < .001 |

| OSA prevalence AHI ≥ 15 events/h | 53.5% (n = 863) | 21.2% (n = 1,189) | < .001 |

AHI = apnea-hypopnea index; SAGIC = Sleep Apnea Global Interdisciplinary Consortium.

P value from Student t test (for continuous data), two-proportion z test (for categorical data), or a χ2 test (race).

Not applicable (NA). Small proportion of Asian subjects automatically classified as Other in the Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS) to avoid identifiable information.

Model Analysis in Retrospective Data

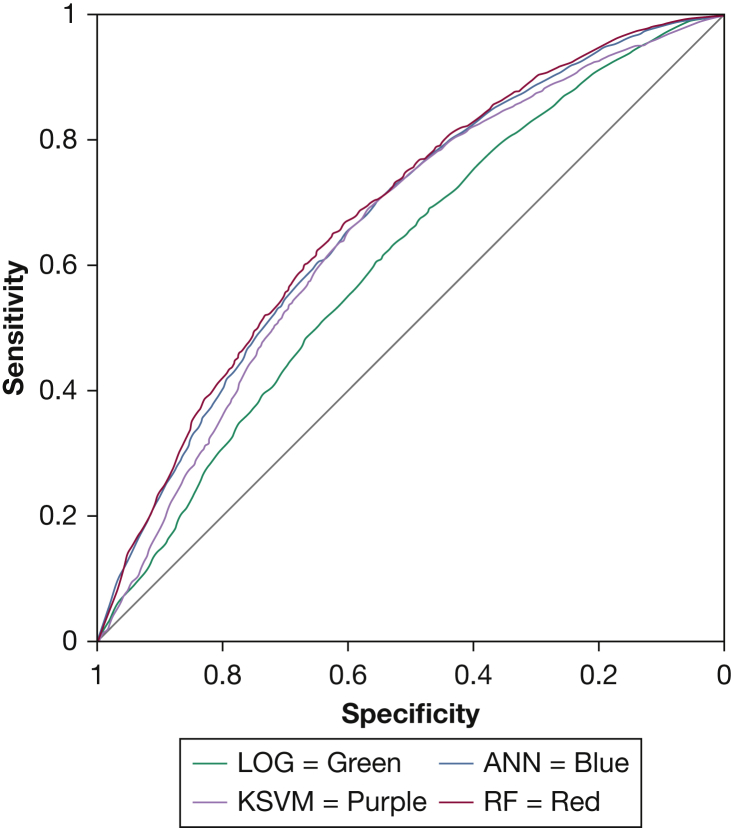

We observed statistically significant improvements in model performance using ANN, RF, and KSVM compared with logistic regression in both the training (e-Table 2) and validation (Fig 1, Table 3) datasets. In the retrospective validation dataset, the AUC of logistic regression (AUC [95% CI], 0.61 [0.60-0.62]) was lower compared with that of ANN (0.68 [0.66-0.69]; P < .001), RF (0.68 [0.67-0.70]; P < .001), and KSVM (0.66 [0.65-0.67]; P < .001). The improvement in predictive characteristics with machine learning models was mostly produced by higher sensitivities and gains in both positive and negative likelihood ratio values. Similar results were observed in the retrospective training dataset (e-Table 1).

Figure 1.

Receiver-operating characteristic curve of machine learning models and LOG model in the retrospective validation dataset. ANN = artificial neural network; KSVM= kernel support vector machine; LOG = logistic regression; RF= random forest.

Table 3.

Diagnostic Performance of Machine Learning Models and Logistic Regression in the Retrospective Validation Dataset (n = 6,979)

| Characteristic | Estimate (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOG | ANN | RF | KSVM | |

| Sensitivity | 0.65 (0.64-0.67) | 0.74 (0.73-0.76)a | 0.73 (0.71-0.74)a | 0.73 (0.72-0.75)a |

| Specificity | 0.51 (0.49-0.52) | 0.51 (0.49-0.53) | 0.53 (0.52-0.55) | 0.52 (0.50-0.54) |

| Positive predictive value | 0.60 (0.59-0.62) | 0.63 (0.62-0.65)a | 0.64 (0.62-0.65)a | 0.63 (0.62-0.65)a |

| Negative predictive value | 0.56 (0.54-0.58) | 0.64 (0.62-0.66)a | 0.63 (0.61-0.65)a | 0.63 (0.61-0.65)a |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 1.32 (1.27-1.38) | 1.51 (1.45-1.57)a | 1.55 (1.49-1.62)a | 1.52 (1.46-1.59)a |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.69 (0.65-0.73) | 0.50 (0.47-0.54)a | 0.52 (0.49-0.55)a | 0.52 (0.49-0.55)a |

| AUC | 0.61 (0.60-0.62) | 0.68 (0.66-0.69)a | 0.68 (0.67-0.70)a | 0.66 (0.65-0.67)a |

ANN = artificial neural network; AUC = area under receiver-operating characteristic curve; KSVM = kernel support vector machine; LOG = logistic regression; RF = random forest.

Represents a P value of < .05 compared with LOG model.

Model Analysis in Prospective Data

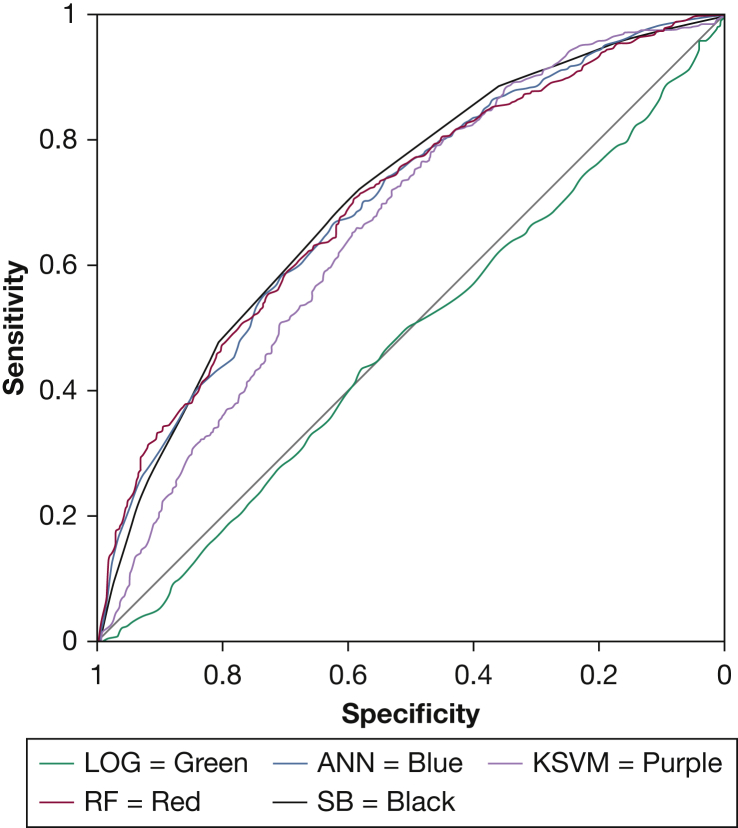

In the prospective SAGIC clinical sample, two of the machine learning algorithms, ANN and RF, performed similarly to the STOP-BANG (Fig 2, Table 4). Compared with the STOP-BANG questionnaire (AUC [95% CI], 0.71 [0.68-0.72]), there was no statistically significant difference in AUC values for the ANN (0.70 [0.68-0.72]; P = .505) or the RF (0.70 [0.68-0.73]; P = .544) models. However, the KSVM model (0.67 [0.64-0.69]) performed statistically significantly worse (P = .001) than the STOP-BANG questionnaire, although the AUC difference was small. The machine learning techniques showed higher specificity but lower sensitivity compared with the STOP-BANG. The LOG model was significantly worse than all other models in this dataset.

Figure 2.

Receiver-operating characteristic curve of machine learning models, LOG, and SB in the prospective clinical dataset from the Sleep Apnea Global Interdisciplinary Consortium. ANN = artificial neural network; LOG = logistic regression; KSVM = kernel support vector machine; RF = random forest; SB = STOP-BANG.

Table 4.

Diagnostic Performance of Machine Learning Models, LOG, and STOP-BANG in the Prospective Clinical Dataset From SAGIC (n = 1,613)

| Characteristic | Estimate (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STOP-BANG | ANN | RF | KSVM | LOG | |

| Sensitivity | 0.89 (0.87-0.91) | 0.80 (0.77-0.83)a | 0.77 (0.74-0.80)a | 0.79 (0.76-0.82)a | 0.39 (0.36-0.42)a |

| Specificity | 0.36 (0.33-0.40) | 0.46 (0.42-0.49)a | 0.49 (0.46-0.53)a | 0.46 (0.42-0.50)a | 0.63 (0.60-0.67)a |

| Positive predictive value | 0.62 (0.59-0.64) | 0.63 (0.60-0.66) | 0.64 (0.61-0.67)a | 0.63 (0.60-0.66) | 0.55 (0.51-0.59)a |

| Negative predictive value | 0.74 (0.69-0.78) | 0.67 (0.62-0.71)a | 0.65 (0.61-0.69)a | 0.66 (0.61-0.70)a | 0.47 (0.44-0.50)a |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 1.39 (1.31-1.48) | 1.47 (1.36-1.58) | 1.53 (1.41-1.65)a | 1.46 (1.36-1.58) | 1.05 (0.93-1.19)a |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.31 (0.25-0.38) | 0.44 (0.38-0.51)a | 0.46 (0.40-0.53)a | 0.46 (0.39-0.53)a | 0.97 (0.90-1.05)a |

| AUC | 0.71 (0.68-0.72) | 0.70 (0.68-0.72) | 0.70 (0.68-0.73) | 0.67 (0.64-0.69)a | 0.48 (0.45-0.51)a |

ANN = artificial neural network; AUC = area under receiver-operating characteristic curve; KSVM = kernel support vector machine; LOG = logistic regression; RF = random forest; SAGIC = Sleep Apnea Global Interdisciplinary Consortium.

Represents a P value of < .05 compared with STOP-BANG.

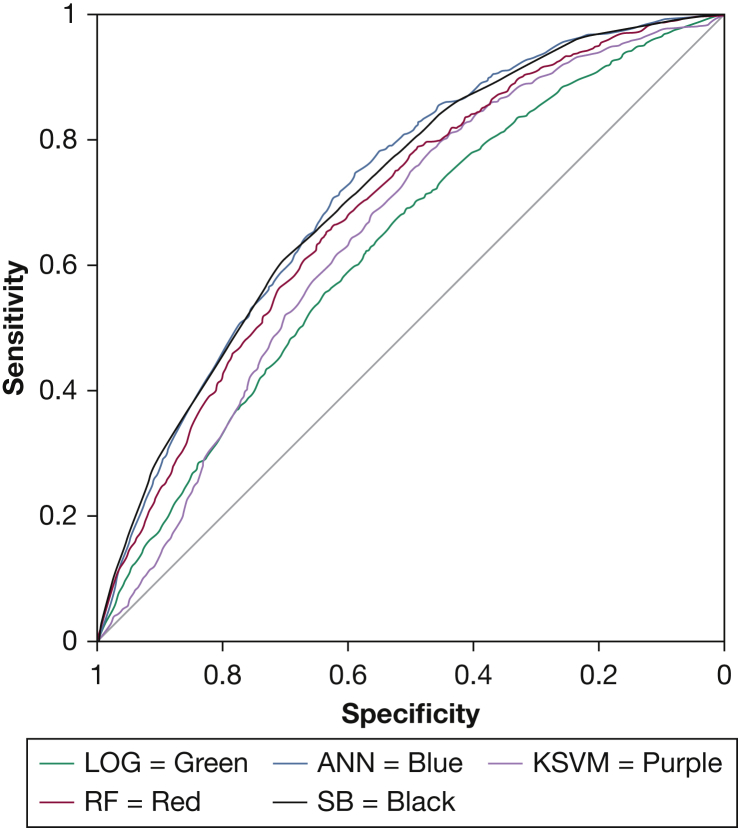

In the community-based SHHS sample, the ANN was the only machine learning model with performance similar to that of the STOP-BANG (Fig 3, Table 5). Specifically, the STOP-BANG (AUC [95% CI], 0.72 [0.70-0.73]) and ANN (0.72 [0.71-0.74]) had similar AUC statistics (P = .714), whereas the STOP-BANG statistically outperformed the RF (0.69 [0.68-0.71]; P = .006) and KSVM (0.65 [0.64-0.67]; P < .001), although again the differences are small. The LOG model again had the lowest AUC in this dataset.

Figure 3.

Receiver-operating characteristic curve of machine learning models, LOG, and SB in the community-based Sleep Heart Health Study dataset. ANN = artificial neural network; KSVM = kernel support vector machine; LOG = logistic regression; RF = random forest; SB = STOP-BANG.

Table 5.

Diagnostic Performance of Machine Learning Models, LOG, and STOP-BANG in the Community-Based Sleep Heart Health Study Dataset

| Characteristic | Estimate (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STOP-BANG | ANN | RF | KSVM | LOG | |

| Sensitivity | 0.86 (0.84-0.88) | 0.91 (0.89-0.92)a | 0.83 (0.80-0.85)a | 0.85 (0.83-0.87) | 0.81 (0.79-0.84)a |

| Specificity | 0.44 (0.42-0.45) | 0.37 (0.35-0.38)a | 0.42 (0.41-0.44)a | 0.39 (0.37-0.40)a | 0.36 (0.34-0.37)a |

| Positive predictive value | 0.29 (0.28-0.31) | 0.28 (0.26-0.29)a | 0.28 (0.26-0.29)a | 0.27 (0.26-0.29)a | 0.25 (0.24-0.27)a |

| Negative predictive value | 0.92 (0.91-0.93) | 0.94 (0.92-0.95)a | 0.90 (0.89-0.91)a | 0.90 (0.89-0.92)a | 0.88 (0.86-0.89)a |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 1.53 (1.47-1.58) | 1.43 (1.39-1.47)a | 1.43 (1.38-1.48)a | 1.38 (1.34-1.43)a | 1.26 (1.22-1.31)a |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.33 (0.28-0.38) | 0.25 (0.21-0.30)a | 0.41 (0.36-0.47)a | 0.40 (0.35-0.46)a | 0.52 (0.46-0.60)a |

| AUC | 0.72 (0.70-0.73) | 0.72 (0.71-0.74) | 0.69 (0.68-0.71)a | 0.65 (0.64-0.67)a | 0.63 (0.62-0.64)a |

ANN = artificial neural network; AUC = area under receiver-operating characteristic curve; KSVM = kernel support vector machine; LOG = logistic regression; RF = random forest.

Represents a P value of < .05 compared with STOP-BANG.

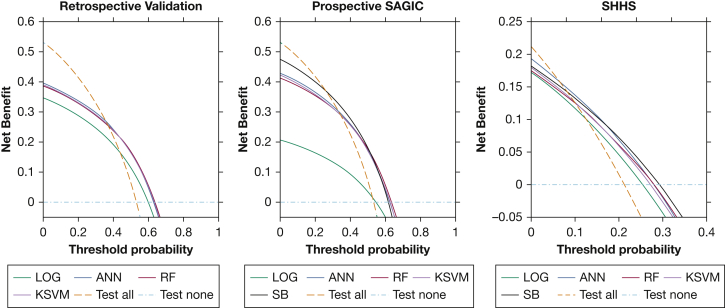

Net benefit analysis was evaluated by using decision curves (Fig 4).35 In the retrospective validation sample, the ANN, RF, and KSVM approaches were the preferred testing strategy between threshold probabilities of 37% to 63% because they offered the greatest net benefit. In the prospective SAGIC sample, the net benefit was greatest for the STOP-BANG at threshold probabilities between 26% and 50%, with the net benefit highest for the RF from 51% to 64%. In the SHHS sample, the net benefit was greatest for the ANN between 6% and 15%, whereas the STOP-BANG had the highest net benefit from 16% to 29%.

Figure 4.

Net benefit analysis decision curves. At different clinically defined threshold probabilities to proceed with polysomnography, the testing strategy with the highest net benefit is the preferred approach. Using polysomnogram to test all or none of the patients for moderate to severe OSA is also presented for reference. ANN = artificial neural network; LOG = logistic regression; KSVM = kernel support vector machine; RF = random forest; SB = STOP-BANG; SHHS = Sleep Heart Health Study.

Calibration plots are used to determine if model outputs (predicted probability) correlate with the actual probability of having the predicted outcome.38 The ANN is not as well calibrated as the other models in the clinical datasets, and all models suffer from overestimation of risks in the SHHS community sample (e-Fig 1).

Discussion

This study supports the utility of symptomless machine learning tools for predicting OSA status. First, we found that the symptomless ANN prediction tool had model performance similar to that of the commonly used STOP-BANG questionnaire, which also relies on patient-reported symptoms, in both prospective clinical and community-based testing samples. Second, the symptomless machine learning tools that incorporated four routinely collected clinic variables (age, sex, BMI, and race) outperformed a traditional LOG model in predicting moderate to severe OSA. Thus, using readily available data from the EMRs, machine learning algorithms may provide a more efficient way for large-scale identification of sleep apnea.

The prevalence of OSA is increasing globally, with the disease estimated to affect approximately 1 billion adults.37 The economic costs of undiagnosed OSA in the United States alone is upward of $149 billion.39 Furthermore, the global burden of untreated OSA is associated with medical comorbidities, poor workplace performance, and motor vehicle crashes.40 Although age, sex, and BMI are traditional risk factors used toward OSA identification, some studies, including work from our group, have also observed that ethnicity/race and craniofacial features are potential predictive factors.10,11,41,42 However, efficient identification of OSA remains problematic. Thus, there is a critical need for simple OSA prediction tools that could lead to widespread identification of the condition.

The ANN prediction tool was trained in an international clinic sample with multiple racial backgrounds and tested in large clinical and community-based samples. The performance of the trained model in the SHHS shows utility in community samples with a lower prevalence of OSA. Further validation in the prospective sample of international subjects in SAGIC showed consistent utility of the ANN in a more diverse sample, including a high proportion of Asian subjects.

We compared multiple machine learning methods against a LOG model to show their utility and illustrate differences in terms of accuracy. In this study, although RF and KSVM initially exhibited performance gains in model fitting, when expanded to alternative populations, the ANN showed more consistent results, albeit the differences were small. Within the diverse clinical prospective sample, the LOG model revealed an AUC of 0.48, indicating no predictive value. This finding further reinforces the importance of testing predictive models in varying populations with distinct characteristics (eg, clinical vs community-based).

There is not a well-defined threshold probability for determining if a PSG should be done to evaluate for sleep apnea, and therefore decision curves are useful for evaluating multiple testing scenarios. Depending on the threshold and population, the ANN, RF, KSVM, and STOP-BANG each had a range in which they were preferred over all or none of the testing strategies. When considering models for translation into practice, it is important to consider the different pretest probabilities (prevalence of OSA). The pretest probability of moderate to severe OSA was about 53% and 21% in the SAGIC clinical samples and the SHHS community sample, respectively; because all of the tested models do not strongly rule out sleep apnea when negative, they were found to be a less effective strategy than testing all patients if the threshold probability is lower than 25% (retrospective SAGIC), 37% (prospective SAGIC), or 6% (SHHS). Compared with the STOP-BANG, the ANN was a superior strategy between the threshold probability ranges of 51% to 64% in the prospective SAGIC clinic sample, but the STOP-BANG had a similar benefit and a wider range of clinical utility. The ANN had the highest net benefit from 6% to 15%, and the STOP-BANG was highest between 16% and 29% in the SHHS community sample, but the differences were small.

The current approach has several strengths. Symptomless models that perform similarly to symptom-based models indicate the ability to assess for OSA without patient-reported symptoms. This approach has clear advantages in facilitating individual patient screening, including in at-risk populations who may not divulge symptoms, as well as potential multilevel screening techniques using EMR to prompt OSA evaluation. Model development was enhanced by using data from the SAGIC cohort, a large, multicenter, ethnically diverse patient population across continents. Although there were differences in the desaturation criteria, this large dataset (N = 17,448) allowed for model development based on a generally uniform standard among all sites.10,12,17 The incorporation of data from varying ethnicities also adds to the generalizability of the prediction models. In addition, the data used in these models represent readily available information from most clinical encounters.

The current study has several limitations. First, the calculation of the STOP-BANG score in this study was not based on direct assessment; nevertheless, this approach of estimating the score has been validated in prior studies.20 Second, in the retrospective dataset that was used for derivation and validation of the machine learning models, different definitions of hypopneas were used: ≥ 4% desaturation in the Ohio site (n = 5,833) and ≥ 3% desaturation and/or an arousal in the Penn, Perth, Sydney, and Taiwan sites (n = 11,615). This method could have affected the performance of the machine learning models, as only a ≥ 4% desaturation criterion was used in both the prospective datasets (SAGIC and SHHS). Third, although we found that the symptomless ANN prediction tool had model performance similar to that of the commonly used STOP-BANG questionnaire, both prediction tools suffer from low specificity. In community-based samples, the results suggest that the ANN prediction could be used to exclude the presence of sleep apnea given its high negative predictive value. Future studies need to determine whether additional information that is also readily available in EMRs (eg, comorbidities) would improve the specificity of the symptomless prediction tool. Fourth, use of machine learning in medicine presents its own challenges,43,44 including how to best implement results in clinical practice. Importantly, the ANN software (NeuroShell Classifier) used in our study includes an add-in feature that allows firing of the trained neural network from an Excel spreadsheet or from a Web page. This means that the ANN model can be deployed for use in the clinical setting because the algorithm can be embedded in EMR systems and automatically calculates the risk of OSA by using readily available data. Finally, although the AUC is a reliable indicator of model discrimination, the clinical usefulness of these models is dependent on the threshold probability of treating sleep apnea. This threshold has not been well established for moderate to severe sleep apnea and is subjectively defined. The models used a chosen “optimal” cut-point for prediction in the secondary analysis to calculate predictive characteristics such as sensitivity and specificity, which are clinically informative. If a cut-point is not used and the results are taken as a prediction of risk, model calibration is needed.36,38

Using a big data approach for OSA identification is timely. In 2017, the US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation statement for OSA concluded that there is insufficient evidence to “assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for OSA in asymptomatic adults […] including those with previously unrecognized symptoms.”45 The use of symptomless machine learning models lends itself to future studies investigating associations with adverse outcomes (eg, risk stratification) in large databases, as previously shown by Lyons et al.7 To facilitate more efficient use of clinical resources, the machine learning algorithm described here may be evaluated in future studies in a two-stage approach to efficiently identify patients who will require more in-depth testing for OSA.6,46,47,48

Interpretation

The machine learning-derived symptomless OSA prediction tool using ANN both outperformed the LOG approach and had a similar AUC to the STOP-BANG questionnaire, which requires patient-reported symptoms. This novel symptomless tool may have utility for widespread identification of OSA. With improved machine learning prediction algorithms based on routinely collected patient information, widespread identification of OSA risk could facilitate improved clinical care and patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: S. J. H., M. M. L., and U. J. M. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis; S. J. H., M. M. L., B. T. K., D. R. M., J. M., G. M., and U. J. M. were responsible for study concept and design; P. A. C., K. S., N. M., B. S., N.-H. C., T. G., T. P., F. H., Q. Y. L., R. S., A. I. P., and U. J. M. contributed to data acquisition; S. J. H., M. M. L., D. R. M., B. T. K., A. I. P., and U. J. M. were responsible for analysis and interpretation of data; and S. J. H., M. M. L., B. T. K., D. R. M., and U. J. M. prepared the manuscript draft. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: A. I. P. is the John Miclot Professor of Medicine, Division of Sleep Medicine/Department of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. The Miclot chair was provided by funds from Respironics Foundation. P. A. C. has an appointment to an endowed academic Chair at the University of Sydney that was created from ResMed funding; he receives no personal fees, and this relationship is managed by an Oversight Committee of the University. P. A. C. has received research support from ResMed, SomnoMed, Zephyr Sleep Technologies, and Bayer; is a consultant/adviser to Zephyr Sleep Technologies, ResMed, SomnoMed, and Signifier Medical Technologies; and has a pecuniary interest in SomnoMed related to a previous role in research and development (2004). None declared (S. J. H., M. M. L., B. T. K., D. R. M., J. M., G. M., K. S., N. M., B. S., N.-H. C., T. G., T. P., F. H., Q. Y. L., R. S., U. J. M.).

Role of sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design of the study, the acquisition and analysis of the data, or the drafting of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Appendix, e-Figure and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

Drs Holfinger and Lyons contributed equally to the manuscript.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: A. I. P. was supported by a Program Project Grant from the National Institutes of Health [P01 HL094307]. D. R. M. is funded by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Foundation [#194-SR-18]. The project was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences [Grant UL1TR001070]. The Sleep Heart Health Study was supported by Grants U01HL53916, U01HL53931, U01HL53934, U01HL53937, U01HL53938, U01HL53940, U01HL53941, and U01HL64360 from the National Institutes of Health. The National Sleep Research Resource was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [R24 HL114473 and 75N92019R0022].

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Flemons W.W., Whitelaw W.A., Brant R., Remmers J.E. Likelihood ratios for a sleep apnea clinical prediction rule. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(5 pt 1):1279–1285. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.5.7952553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maislin G., Pack A.I., Kribbs N.B., et al. A survey screen for prediction of apnea. Sleep. 1995;18(3):158–166. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.3.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung F., Yegneswaran B., Liao P., et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(5):812–821. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31816d83e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teferra R.A., Grant B.J., Mindel J.W., et al. Cost minimization using an artificial neural network sleep apnea prediction tool for sleep studies. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(7):1064–1074. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201404-161OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyons M.M., Kraemer J.F., Dhingra R., et al. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea in commercial drivers using EKG-derived respiratory power index. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(1):23–32. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurubhagavatula I., Nkwuo J.E., Maislin G., Pack A.I. Estimated cost of crashes in commercial drivers supports screening and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Accid Anal Prev. 2008;40(1):104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyons M.M., Keenan B.T., Li J., et al. Symptomless multi-variable apnea prediction index assesses obstructive sleep apnea risk and adverse outcomes in elective surgery. Sleep. 2017;40(3) doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obermeyer Z., Emanuel E.J. Predicting the future—big data, machine learning, and clinical medicine. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(13):1216–1219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1606181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tu J.V. Advantages and disadvantages of using artificial neural networks versus logistic regression for predicting medical outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(11):1225–1231. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizzatti F.G., Mazzotti D.R., Mindel J., et al. Defining extreme phenotypes of OSA across international sleep centers. Chest. 2020;158(3):1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutherland K., Keenan B.T., Bittencourt L., et al. A global comparison of anatomic risk factors and their relationship to obstructive sleep apnea severity in clinical samples. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(4):629–639. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magalang U.J., Arnardottir E.S., Chen N.H., et al. Agreement in the scoring of respiratory events among international sleep centers for home sleep testing. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(1):71–77. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keenan B.T., Kim J., Singh B., et al. Recognizable clinical subtypes of obstructive sleep apnea across international sleep centers: a cluster analysis. Sleep. 2018;41(3) doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung F., Subramanyam R., Liao P., Sasaki E., Shapiro C., Sun Y. High STOP-Bang score indicates a high probability of obstructive sleep apnoea. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108(5):768–775. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quan S.F., Howard B.V., Iber C., et al. The Sleep Heart Health Study: design, rationale, and methods. Sleep. 1997;20(12):1077–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berry R.B., Brooks R., Gamaldo C., et al. AASM Scoring Manual Updates for 2017 (Version 2.4) J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(5):665–666. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magalang U.J., Chen N.H., Cistulli P.A., et al. Agreement in the scoring of respiratory events and sleep among international sleep centers. Sleep. 2013;36(4):591–596. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redline S., Sanders M.H., Lind B.K., et al. Methods for obtaining and analyzing unattended polysomnography data for a multicenter study. Sleep Heart Health Research Group. Sleep. 1998;21(7):759–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shahar E., Whitney C.W., Redline S., et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(1):19–25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva G.E., Vana K.D., Goodwin J.L., Sherrill D.L., Quan S.F. Identification of patients with sleep disordered breathing: comparing the four-variable screening tool, STOP, STOP-Bang, and Epworth Sleepiness Scales. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(5):467–472. doi: 10.5664/JCSM.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoehfeld M., Fahlman S.E. Learning with limited numerical precision using the cascade-correlation algorithm. IEEE Trans Neural Netw. 1992;3(4):602–611. doi: 10.1109/72.143374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fahlman S., Lebiere C. In: Touretzky D., editor. Vol 2. Morgan Kaufmann; San Mateo, CA: 1990. The Cascade-Correlation Learning Architecture; pp. 524–532. (Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breiman L. Random forests. Machine Learning. 2001;45(1):5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fast Unified Random Forests for Survival, Regression, and Classification (RF-SRC) [computer program]. Version 2.9.0. Accessed April 30, 2019. https://cran.r-project.org/package=randomForestSRC

- 25.Bischl B., Lang M., Kotthoff L., et al. “mlr: Machine Learning in R.”. J Machine Learning Res. 2016;17(170):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Platt J. In: Advances in Large Margin Classifiers. Smola A., Bartlett P., Schoelkopf B., Schuurmans D., editors. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2000. Probabilistic outputs for support vector machines and comparison to regularized likelihood methods. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karatzoglou A., Smola A., Hornik K., Zeileis A. kernlab—an S4 Package for Kernel Methods in R. J Statistical Software. 2004;11(9):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robin X., Turck N., Hainard A., et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moskowitz C.S., Pepe M.S. Comparing the predictive values of diagnostic tests: sample size and analysis for paired study designs. Clin Trials. 2006;3(3):272–279. doi: 10.1191/1740774506cn147oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nofuentes J.A.R., de Dios Luna Del Castillo J. Comparison of the likelihood ratios of two binary diagnostic tests in paired designs. Stat Med. 2007;26(22):4179–4201. doi: 10.1002/sim.2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fijorek K., Fijorek D., Wisniowska B., Polak S. BDTcomparator: a program for comparing binary classifiers. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(24):3439–3440. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jastrzebski M., Kukla P., Fijorek K., Sondej T., Czarnecka D. Electrocardiographic diagnosis of biventricular pacing in patients with nonapical right ventricular leads. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35(10):1199–1208. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2012.03476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arias-Loste M.T., Bonilla G., Moraleja I., et al. Presence of anti-proteinase 3 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (Anti-PR3 ANCA) as serologic markers in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45(1):109–116. doi: 10.1007/s12016-012-8349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vickers A.J., Van Calster B., Steyerberg E.W. Net benefit approaches to the evaluation of prediction models, molecular markers, and diagnostic tests. BMJ. 2016:352. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collins G.S., Reitsma J.B., Altman D.G., Moons K.G. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. J Br Surg. 2015;102(3):148–158. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benjafield A.V., Ayas N.T., Eastwood P.R., et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(8):687–698. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30198-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Calster B., McLernon D.J., Van Smeden M., Wynants L., Steyerberg E.W. Calibration: the Achilles heel of predictive analytics. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1466-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frost & Sullivan American Academy of Sleep Medicine Hidden health crisis costing America billions. Underdiagnosing and undertreating obstructive sleep apnea draining healthcare system. http://www.aasmnet.org/sleep-apnea-economic-impact.aspx

- 40.Lyons M.M., Bhatt N.Y., Pack A.I., Magalang U.J. Global burden of sleep-disordered breathing and its implications. Respirology. 2020;25(7):690–702. doi: 10.1111/resp.13838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu L., Keenan B.T., Wiemken A.S., et al. Differences in three-dimensional upper airway anatomy between Asian and European patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2020;43(5) doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho J.H., Choi J.H., Suh J.D., Ryu S., Cho S.H. Comparison of anthropometric data between Asian and Caucasian patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;9(1):1–7. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2016.9.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen J.H., Asch S.M. Machine learning and prediction in medicine—beyond the peak of inflated expectations. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(26):2507–2509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1702071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deo R.C. Machine learning in medicine. Circulation. 2015;132(20):1920–1930. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.001593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.US Preventive Services Task Force. Bibbins-Domingo K., Grossman D.C., et al. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2017;317(4):407–414. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gislason T., Almqvist M., Eriksson G., Taube A., Boman G. Prevalence of sleep apnea syndrome among Swedish men—an epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(6):571–576. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gislason T., Taube A. Prevalence of sleep apnea syndrome—estimation by two stage sampling. Ups J Med Sci. 1987;92(2):193–203. doi: 10.3109/03009738709178689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Platt A.B., Wick L.C., Hurley S., et al. Hits and misses: screening commercial drivers for obstructive sleep apnea using guidelines recommended by a joint task force. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55(9):1035–1040. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318298fb0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.