Abstract

Background

Emerging data from longitudinal studies suggest that preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm), defined by proportionate reductions in FEV1 and FVC, is a heterogeneous population with frequent transitions to other lung function categories relative to individuals with normal and obstructive spirometry. Controversy regarding the clinical significance of these transitions exists (eg, whether transitions merely reflect measurement variability or noise).

Research Question

Are individuals with PRISm enriched for transitions associated with substantial changes in lung function?

Study Design and Methods

Current and former smokers enrolled in the Genetic Epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study with spirometry available in phases 1 through 3 (enrollment, 5-year follow-up, and 10-year follow-up) were analyzed. Postbronchodilator lung function categories were as follows: PRISm (FEV1 < 80% predicted with FEV1/FVC ratio ≥ 0.7), Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease grade 0 (FEV1 ≥ 80% predicted and FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.7), and obstruction (FEV1/FVC < 0.7). Significant transition status was affirmative if a subject belonged to two or more spirometric categories and had > 10% change in FEV1 % predicted and/or FVC % predicted between consecutive visits. Ever-PRISm was present if a subject had PRISm at any visit. Logistic regression examined the association between significant transitions and ever-PRISm status, adjusted for age, sex, race, FEV1 % predicted, current smoking, pack-years, BMI, and ever-positive bronchodilator response.

Results

Among subjects with complete data (N = 1,775) over 10.1 ± 0.4 years of follow-up, the prevalence of PRISm remained consistent (10.4%-11.3%) between phases 1 through 3, but nearly one-half of subjects with PRISm transitioned into or out of PRISm at each visit. Among all subjects, 19.7% had a significant transition; ever-PRISm was a significant predictor of significant transitions (unadjusted OR, 10.3; 95% CI, 7.9-13.5; adjusted OR, 14.9; 95% CI, 10.9-20.7). Results were similar with additional adjustment for radiographic emphysema and gas trapping, when lower limit of normal criteria were used to define lung function categories, and when FEV1 alone (regardless of change in FVC % predicted) was used to define significant transitions.

Interpretation

PRISm is an unstable group, with frequent significant transitions to both obstruction and normal spirometry over time.

Clinical Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov; No.: NCT000608764; URL: www.clinicaltrials.gov

Key Words: COPD, epidemiology, lung function, restrictive spirometry

Abbreviations: BDR, bronchodilator response; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPDGene, Genetic Epidemiology of COPD study; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; LLN, lower limit of normal; PRISm, preserved ratio impaired spirometry; TLV, total lung volume

Take-home Points.

Study Question: Are individuals with preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm), defined by proportionate reductions in FEV1 and FVC, enriched for transitions to other lung function categories (normal and obstructed) associated with substantial changes in lung function?

Results: Among 1,775 ever smokers with longitudinal data over 10.1 ± 0.4 years of follow-up, PRISm at any time point was a significant predictor of significant transitions, defined as a change in lung function category and > 10% change in FEV1 % predicted or FVC % predicted between consecutive study visits.

Interpretation: Among ever smokers, PRISm is an unstable group enriched for significant transitions to both obstruction and normal spirometry over time.

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT, SEE PAGE 593

Preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm), defined as proportionate reductions in FEV1 and FVC,1 has a cross-sectional prevalence of 6% to 24.3%2, 3, 4, 5 globally and is associated with increased respiratory symptoms6, 7, 8 and mortality.4,5,9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Emerging data from independent longitudinal studies suggest that PRISm represents a transitional state in a significant proportion of individuals, with subsets either progressing to airflow obstruction or reverting to normal spirometry over time.13,15,16

Potential contributors to the transitions observed in PRISm include artifacts due to variability in spirometry testing17 as well as clinically meaningful changes in lung function. To explore this topic, we examined transitions between categories associated with substantial changes in lung function, defined as > 10% change over 5 years in postbronchodilator FEV1 and/or FVC % predicted. We hypothesize that individuals who demonstrate these significant transitions will be enriched for PRISm relative to subjects with Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) grade 0 and obstructive spirometry (GOLD grades 1 through 4) and examine data from current and former smokers enrolled in the Genetic Epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study with approximately 10 years of follow-up. Some of the results presented have been previously reported in the form of an abstract.18

Study Design and Methods

Cohort

Subjects are participants in COPDGene, an observational study of non-Hispanic White and Black current and former smokers throughout the United States.19 Institutional review board approval was obtained at each site, and all subjects provided written informed consent. At baseline (phase 1, 2008-2011), subjects were 45 to 80 years of age with ≥ 10 pack-years of cigarette smoking. Subjects enrolled in phase 1 were invited to participate in 5-year (phase 2, 2012-2016) and 10-year (phase 3, 2017-present) follow-up visits. For this analysis, data from smokers with spirometry available at all three visits (phases 1, 2, and 3) were analyzed.

Subjects completed questionnaires, spirometry before and after inhaled albuterol, 6-min walk test, and inspiratory and expiratory chest CT scanning at all study visits. Methods of ascertaining quantitative emphysema, gas trapping, and Pi10 on chest CT scan are specified in the Supplementary Methods. Total lung volume (TLV) % predicted was derived using CT scan-assessed lung volume and prediction equations for individuals in the supine position.20 Pectoral muscle area was measured (in cm2) from inspiratory chest CT scans at the level of the aortic arch using an automated technique.21

Variable Definitions

Lung function categories were defined using postbronchodilator spirometry as follows: PRISm (FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.7 and FEV1 < 80% predicted), GOLD grade 0 (FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.7 and FEV1 ≥ 80% predicted), and obstruction (FEV1/FVC < 0.7). Simple transitions between lung function categories were present if an individual belonged to a different lung function category between two consecutive visits. Significant transition status was affirmative if a subject changed lung function categories and had > 10% change in FEV1 % predicted and/or FVC % predicted between the corresponding visits. Ever-PRISm was considered present if a subject had PRISm on spirometry at any visit. Bronchodilator response (BDR) was positive if an increase of ≥ 12% and ≥ 200 mL in FEV1 or FVC after inhaled albuterol was present. Comorbid conditions (eg, diabetes, congestive heart failure [CHF], chronic kidney disease [CKD], physician-diagnosed asthma) and medication use were self-reported.

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate comparisons were made using χ2 or Fisher exact test (categorical) and Student t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test (continuous). Multivariable-adjusted logistic regression examined the association between significant transitions (dependent variable) and ever-PRISm status (independent variable) while adjusting for ever having a positive BDR, baseline age, sex, race, current smoking status, pack-years, FEV1 % predicted, and BMI. A secondary model included additional adjustment for quantitative emphysema and gas trapping. All analyses were conducted using R statistical software (version 3.4.3; The R Project for Statistical Computing).

Subgroup and Secondary Analyses

To examine features potentially associated with significant transitions among subjects with PRISm, we compared selected baseline and longitudinal characteristics of individuals who experienced (1) significant transition into PRISm and (2) significant transition out of PRISm relative to the remainder of the analysis cohort. We also examined the association between ever-PRISm and significant transitions (1) using > 10% change in FEV1 alone (irrespective of change in FVC), (2) using > 15% change in either FEV1 or FVC to denote significant transitions, and (3) associated with either > 10% increase or > 10% decrease in lung function separately. Exploratory analyses examined whether transitions associated with significant increases or decreases in lung function were associated with changes in TLV % predicted. Selected analyses were repeated using the lower limit of normal (LLN)22 to define the following lung function categories: PRISmLLN (FEV1/FVC ≥ LLN and FEV1 < LLN), GOLD 0LLN (FEV1/FVC ≥ LLN and FEV1 ≥ LLN), and obstructiveLLN (FEV1/FVC < LLN).

Results

The prevalence of PRISm among all current and former smokers with lung function data available at phase 1 (n = 10,132), phase 2 (n = 5,621), and phase 3 (1,933) was 12.5%, 12.5%, and 12%, respectively. A total of 1,775 subjects had spirometry data available at all three study visits over an average of 10.1 ± 0.4 years of follow-up (e-Fig 1); subjects not included in the analysis dataset were similar in age and BMI at enrollment, but had worse lung function, greater cumulative smoking, and a higher proportion of current smokers, men, individuals of Black race, and individuals with PRISm at baseline. The prevalence of PRISm within this analysis cohort was 10.4% (phase 1), 10.8% (phase 2), and 11.3% (phase 3); baseline characteristics of the analysis cohort by lung function category are shown in Table 1. Individuals with PRISm at baseline had the highest rates of simple and significant transitions.

Table 1.

Cohort Characteristics by Baseline Lung Function Categories

| Characteristic | PRISm (n = 185) | PRISm vs GOLD Grade 0 P Value | GOLD Grade 0 (n = 884) | GOLD Grade 0 vs Obstructed P Value |

Obstructed (n = 706) | PRISm vs Obstructed P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 103 (55.7) | .71 | 476 (53.8) | .003 | 327 (46.3) | .03 |

| Race (Black) | 72 (38.9) | .08 | 283 (32.0) | < .001 | 136 (19.3) | < .001 |

| Age, y | 57.0 ± 8 | .58 | 57.4 ± 8.1 | < .001 | 62.0 ± 7.9 | < .001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.9 ± 7.1 | < .001 | 29 ± 5.6 | < .001 | 28 ± 5.6 | < .001 |

| Current smoking | 102 (55.1) | .06 | 416 (47.1) | .001 | 274 (38.8) | < .001 |

| Pack-years | 44.2 ± 24.5 | < .001 | 36.1 ± 19.8 | < .001 | 48.8 ± 24.4 | .02 |

| FEV1 % predicted (postbronchodilator) | 70.6 ± 7.9 | < .001 | 97.8 ± 11.1 | < .001 | 65.5 ± 21.6 | .002 |

| FVC % predicted (postbronchodilator) | 72.3 ± 9.2 | < .001 | 96.8 ± 11.4 | < .001 | 88.5 ± 18.9 | < .001 |

| Bronchodilator responsive (baseline) | 29 (15.8) | < .001 | 61 (7.0) | < .001 | 230 (32.9) | < .001 |

| Percent emphysemaa | 2.0 ± 3.5 | .04 | 2.5 ± 3.0 | < .001 | 10 ± 10.5 | < .001 |

| Percent gas trappingb | 9.9 ± 8.1 | .42 | 10.5 ± 8.4 | < .001 | 30.9 ± 17.8 | < .001 |

| Pi10c | 2.4 ± 0.6 | < .001 | 2 ± 0.4 | < .001 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | .19 |

| Total lung volume % predicteda | 90.1 ± 14.6 | < .001 | 103.2 ± 15.4 | < .001 | 112.2 ± 16.6 | < .001 |

| Pectoralis muscle area, cm2,d | 43.9 ± 15.7 | .33 | 42.5 ± 15.9 | < .001 | 39.5 ± 14.0 | .001 |

| SGRQ total score | 25.9 ± 21.7 | < .001 | 14.4 ± 16.6 | < .001 | 27.5 ± 21.1 | .35 |

| 6-min walk distance, m | 409.2 ± 111.2 | < .001 | 472.5 ± 111.1 | < .001 | 428.6 ± 110.5 | .04 |

| Chronic bronchitis | 29 (15.7) | .11 | 99 (11.2) | < .001 | 142 (20.1) | .21 |

| Coronary artery disease (baseline) | 14 (7.6) | .08 | 37 (4.2) | .02 | 50 (7.1) | .95 |

| Hypertension (baseline) | 80 (43.2) | .047 | 311 (35.2) | .06 | 282 (40.0) | .48 |

| Congestive heart failure (baseline) | 9 (4.9) | < .001 | 8 (0.9) | .47 | 10 (1.4) | .009 |

| Diabetes (baseline) | 33 (17.8) | .001 | 83 (9.4) | >.99 | 66 (9.3) | .002 |

| Asthma, physician-diagnosed (baseline) | 38 (20.5) | .001 | 100 (11.3) | < .001 | 154 (21.8) | .78 |

| Oral steroid use (baseline) | 3 (1.6) | .30 | 5 (0.6) | .001 | 19 (2.7) | .57 |

| Inhaled steroid use (baseline) | 31 (16.8) | < .001 | 49 (5.5) | < .001 | 236 (33.4) | < .001 |

| Inhaled bronchodilators (baseline) | 55 (29.7) | < .001 | 100 (11.3) | < .001 | 370 (52.4) | < .001 |

| Any inhaled medication (baseline) | 56 (30.3) | < .001 | 102 (11.5) | < .001 | 374 (53.0) | < .001 |

| Respiratory exacerbations (year prior to enrollment) | 0.3 ± 0.8 | < .001 | 0.1 ± 0.5 | < .001 | 0.5 ± 1 | .11 |

| Respiratory hospitalization (yes/no, year prior to enrollment) | 24 (13.0%) | < .001 | 21 (2.4) | < .001 | 89 (12.6) | .99 |

| Years of follow-up | 10 ± 0.4 | .003 | 10.1 ± 0.4 | .04 | 10.1 ± 0.4 | .08 |

| Simple transition (ever) | 125 (67.6) | < .001 | 283 (32.0) | < .001 | 126 (17.8) | < .001 |

| Significant transition (ever) | 71 (38.4) | < .001 | 179 (20.2) | .001 | 99 (14.0) | < .001 |

Data are presented as No. (%), mean ± SD, or as otherwise indicated. Lung function categories were defined as follows: PRISm (FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.7 and FEV1 < 80%), obstructed (FEV1/FVC < 0.7), and GOLD grade 0 (FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.7 and FEV1 ≥80%). Bronchodilator response was considered positive if ≥ 200 mL and ≥ 12% increase in either FEV1 or FVC was observed after administration of albuterol. GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; SGRQ = Saint George's Respiratory Questionnaire; PRISm = preserved ratio impaired spirometry; Significant transition = change in lung function category plus > 10% change in FEV1 % predicted or FVC % predicted between consecutive study visits (phase 1 to phase 2 or phase 2 to phase 3); Simple transition = change in lung function category between consecutive study visits.

n = 1,670; Percent emphysema defined as low attenuation areas < −950 Hounsfield units on inspiratory CT scan.

Defined as voxels < −856 Hounsfield units on expiratory CT scan (n = 1,489).

Defined as the square root of the wall area of a hypothetical airway with an internal perimeter of 10 mm (n = 1,670).

Measured at the level of the aortic arch (n = 1597).

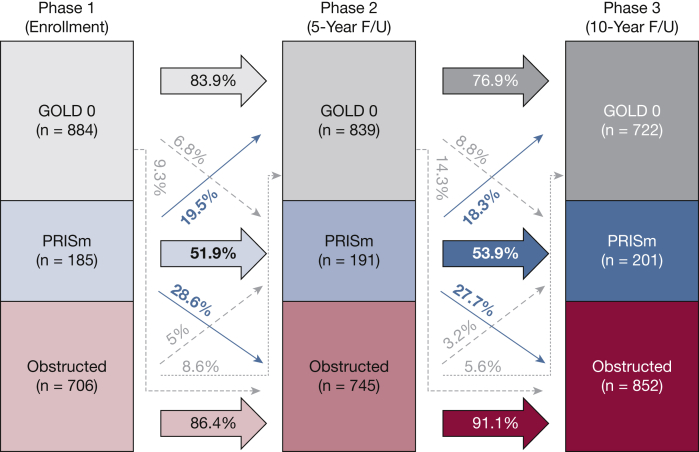

Average rates of change in FEV1 % predicted and FVC % predicted between visits for the cohort and for the subgroup who were consistently GOLD grade 0 at all three visits are shown in e-Table 1. Rates of simple transitions between lung function categories at each phase are illustrated in Figure 1. While subjects with GOLD grade 0 and obstructed spirometry demonstrated high rates of remaining in their respective lung function categories during follow-up (76.8%-91.1%), only approximately one-half (51.9%-53.9%) of subjects with PRISm remained in the same lung function category at each follow-up visit. Therefore, although the cross-sectional prevalence of PRISm at each visit remained relatively consistent, individual membership within PRISm was variable over time.13 The prevalence of significant transitions was 19.7%. Characteristics by significant transition status are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Rates of simple transitions between lung function categories by study visit among subjects with spirometry data at all three visits in COPDGene (N = 1,775). Lung function categories were defined as follows: PRISm (FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.7 and FEV1 < 80% predicted), obstructed (FEV1/FVC < 0.7), and GOLD grade 0 (FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.7 and FEV1 ≥ 80% predicted). F/U = follow-up; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; PRISm = preserved ratio impaired spirometry.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Individuals by Significant Transition Status

| Characteristic | Had Significant Transition During Follow-up? |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 1,436) | Yes (n = 349) | ||

| Sex (female) | 717 (50.3) | 189 (54.2) | .216 |

| Race (Black) | 351 (24.6) | 140 (40.1) | < .001 |

| Age, y | 59.4 ± 8.3 | 58.2 ± 8.3 | .019 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.7 ± 5.7 | 29.6 ± 6.5 | .010 |

| Current smoker | 598 (41.9) | 194 (55.6) | < .001 |

| Pack-years | 42.1 ± 23.0 | 41.4 ± 23.1 | .609 |

| FEV1 % predicted | 81.4 ± 23.7 | 85.1 ± 15.3 | .005 |

| FVC % predicted | 91.0 ± 16.6 | 90.5 ± 15.9 | .612 |

| Percent emphysemaa | 6.0 ± 8.5 | 3.0 ± 4.6 | < .001 |

| Percent gas trappingb | 20.1 ± 17.3 | 13.1 ± 11 | < .001 |

| Pi10a | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | .845 |

| Total lung volume % predicteda | 106.3 ± 17.0 | 101.9 ± 17.1 | < .001 |

| Pectoralis muscle area, cm2,c | 41 ± 14.7 | 43.2 ± 17 | .018 |

| SGRQ | 20.7 ± 19.8 | 21.3 ± 21.2 | .652 |

| 6MWD, m | 449.4 ± 111.1 | 444.8 ± 123.0 | .500 |

| Chronic bronchitis | 225 (15.8) | 45 (12.9) | .207 |

| Bronchodilator response (baseline) | 246 (17.4) | 74 ± 21.6 | .089 |

| Bronchodilator response (ever) | 541 (38.8) | 158 (45.8) | .021 |

| Asthma (baseline) | 234 (16.4) | 58 (16.6) | .989 |

| Asthma (ever) | 297 (20.8) | 81 (23.2) | .367 |

| Oral steroids (baseline) | 23 (1.6) | 4 (1.1) | .693 |

| Inhaled steroids (baseline) | 273 (19.1) | 43 (12.3) | .004 |

| Inhaled bronchodilator (baseline) | 443 (31.1) | 82 (23.5) | .007 |

| Respiratory exacerbation (year prior to enrollment) | 0.29 ± 0.8 | 0.26 ± 0.8 | .583 |

| Respiratory hospitalization (yes/no, year prior to enrollment) | 107 (7.5) | 27 (7.7) | .972 |

| Ever-PRISm (phase 1 to phase 3) | 159 (11.2) | 197 (56.4) | < .001 |

| Change in BMI (phase 1 to phase 2) | −0.1 ± 2.8 | −0.2 ± 3.7 | .755 |

| Change in BMI (phase 2 to phase 3) | 0.4 ± 2.8 | 0.6 ± 2.7 | .343 |

| Change smoking status (phase 1 to phase 2) | 195 (13.7) | 60 (17.2) | .110 |

| Change smoking status (phase 2 to phase 3) | 117 (8.2) | 30 (8.6) | .897 |

| Change in pectoralis muscle area (phase 1 to phase 2) | −2.1 ± 7.4 | −2.6 ± 8.7 | .564 |

| Ever congestive heart failure | 66 (4.6) | 12 (3.4) | .409 |

| Ever chronic kidney disease | 67 (4.7) | 15 (4.3) | .859 |

Data are presented as No. (%) or mean ± SD. Lung function categories were defined as follows: PRISm (FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.7 and FEV1 < 80%), obstructed (FEV1/FVC < 0.7), and GOLD grade 0 (FEV1/FVC ≥ 0.7 and FEV1 ≥ 80%). SGRQ = St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire; 6MWD = 6-min walk distance; Asthma (baseline) = self-reported physician-diagnosed asthma at enrollment; Asthma (ever) = affirmative responses to asthma either at baseline, phase 2 or phase 3 visits; Significant transition = change in lung function category plus > 10% change in FEV1 % predicted or FVC % predicted between consecutive study visits (phase 1 to phase 2 or phase 2 to phase 3).

n = 1,670.

n = 1,489.

n = 1,597.

Subjects who experienced significant transitions were younger, enriched for Black race, had higher baseline FEV1 % predicted, had lower TLV % predicted, had lower rates of inhaled corticosteroid and bronchodilator use at baseline, and had an increased proportion who were ever-PRISm or ever had a positive BDR during the study period. Although subjects with significant transitions had higher baseline BMI, no significant association between spirometric transitions with change in BMI was observed. Similarly, although subjects with significant transitions had a higher rate of current smoking at baseline, there were no significant differences in changes in smoking status during follow-up. Ever-PRISm was a significant predictor of significant transitions in both unadjusted and multivariable-adjusted models (Table 3). In exploratory analyses with additional covariates (inhaled corticosteroid, bronchodilator use, pectoralis muscle area at baseline), none were independent predictors of significant transitions. Results were also similar when individuals with conditions associated with fluid shifts which could impact pulmonary function (eg, CHF, CKD) were excluded. PRISm at baseline was also significantly associated with prospective significant transitions (e-Table 2).

Table 3.

Effect Estimates of Ever-PRISm Status as a Predictor of Significant Transitions in COPDGene

| Predictor: Ever-PRISm (phase 1 to phase 3) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Unadjusted | 10.3 (7.9-13.5) |

| Clinical predictors | 14.9 (10.9-20.7) |

| Clinical and radiographic predictors | 14.3 (9.9-21) |

Clinical predictors included sex, Black race, baseline age, baseline FEV1 % predicted, current smoking status at baseline, BMI, pack-years, and ever having a positive bronchodilator response. Radiographic predictors included percent emphysema and percent gas trapping at baseline. PRISm = preserved ratio impaired spirometry; Significant transition = change in lung function category plus > 10% change in FEV1 % predicted or FVC % predicted between consecutive study visits (phase 1 to phase 2 or phase 2 to phase 3).

Subgroup Analyses

Significant transitions With Either > 10% Increase or > 10% Decrease in Lung Function

When transitions were subdivided by whether a > 10% increase or > 10% decrease in lung function was observed (e-Table 3), ever-PRISm remained a significant predictor for both types of transitions (e-Table 4). Notably, 41 subjects experienced both a significant improvement and deterioration (or vice versa) over the study period. Ever-PRISm was significantly associated with experiencing both significant increases followed by decreases (or vice versa) in unadjusted models (OR, 10.4; 95% CI, 5.4-21.3), models adjusted for clinical variables (OR, 17.5; 95% CI, 7.8-42.8), and adjusted models with clinical and radiographic variables (OR, 14.7; 95% CI, 6.0-38.7).

The average change in TLV % predicted was lower among the group with transitions associated with > 10% decrease (e-Table 5), whereas a trend toward higher TLV % predicted was noted for those with > 10% increase.

Defining Significant Transitions by > 10% Change in FEV1 Only

Of 349 subjects who met the original definition of significant transition, 115 (33%) qualified based on FVC % predicted criteria only, 79 (22.6%) qualified based on FEV1 % predicted only, and 155 (44.4%) qualified based on changes in both. When significant transitions were defined by > 10% change in FEV1 alone (e.g., disallowing changes in FVC to count toward significant transition status), the prevalence of significant transitions was 13.2%. Ever-PRISm remained significantly associated with significant transitions (e-Table 6).

Requiring > 15% Change in FEV1 or FVC for Significant Transitions

When a minimum > 15% change in FEV1 or FVC was used to denote significant transition status, ever-PRISm and ever-PRISmLLN remained highly significant predictors in both unadjusted and multivariable-adjusted models (e-Table 7).

Transitions Into and Out of PRISm

There were 133 subjects who experienced a significant transition into PRISm (67 during phase 1 to phase 2, 66 during phase 2 to phase 3), with most (71.4%, binomial P <.001) originating from GOLD grade 0 (e-Fig 2A). Ninety-one subjects had significant transitions out of PRISm (48 during phase 1 to phase 2, 43 during phase 2 to phase 3) (e-Fig 2B), with 64.8% transitioning to obstruction (binomial P = .002). The number of subjects who experienced both significant transitions into and out of PRISm (n = 29) was greater than expected by chance (Fisher exact P <.001), with most (n = 20, 69%) demonstrating an [X]→PRISm→[X] pattern and the remainder (n = 9, 31%) demonstrating a PRISm → [X] → PRISm pattern. Characteristics of individuals with significant transitions into PRISm and out of PRISm are shown in e-Table 8.

LLN Analysis

When we used LLN criteria to define lung function categories, the prevalence of PRISmLLN among all subjects with lung function data was 10.7% (phase 1, n = 10,132), 10.6% (phase 2, n = 5,621), and 9.6% (phase 3, n = 1,933). Approximately one-half (53.1%-55.1%) of subjects with PRISmLLN remained in the same lung function category, whereas subjects with GOLD 0LLN and obstructedLLN spirometry demonstrated high rates (82.5%-90.5%) of remaining within their respective lung function categories (e-Fig 3). The prevalence of significant transitions between LLN-defined lung function categories was 17.1%. Ever-PRISmLLN was strongly associated with significant transitions (e-Table 9), and with transitions associated with significant increases and decreases in lung function separately (e-Table 10).

Discussion

In this work, we have (1) confirmed that membership in PRISm is dynamic, with large subsets moving into and out of PRISm over time; and (2) presented evidence that PRISm is enriched for transitions associated with substantial changes in lung function. Our concept of the significant transition, which is predicated on the inclusion of a minimum percent change in lung function, is supported by studies of short-term (days to weeks) within-person variability and consensus statements presented on year-to-year variability which report thresholds of 5% to 15% as denoting significant changes in normal and obstructed populations.23, 24, 25, 26 We assert that our threshold of > 10% change over a 5-year period reduces the impact of artifactual transitions due to measurement variability or proximity to lung function category cutoffs17 and enriches for transitions which likely reflect time-varying pathologic processes.

A fundamental premise examined in this work—that PRISm is enriched for individuals who exhibit increased instability and are more prone to transitions—may appear to contradict previous work conducted in COPDGene that identified no transitions to GOLD grade 0 and a transition rate of 35.8% to GOLD grades 2 through 4 over 5 years among 179 subjects with PRISm at baseline.17 In the work by Young et al,17 which used data from COPDGene phases 1 and 2, but not phase 3, individuals with FEV1 % predicted values within 15.7% of the 80% predicted threshold and within 10.5% of the FEV1/FVC ratio threshold of 0.7 were removed from analysis. The discordant findings after removal of individuals close to the GOLD-delineated thresholds may be attributable to retaining only individuals with advanced disease in the Young et al17 analyses. Individuals close to the GOLD-delineated thresholds were not excluded in the current work. In post hoc analyses of our phase 1 to phase 2 data after applying the criteria used by Young et al,17 we confirmed increased rates of both simple (33.4% vs 8.2%) and significant transitions (18.3% vs 7.5%) among subjects who were excluded relative to those included in the Young et al17 analyses. Therefore, individuals with mild to moderate spirometric impairments may be at increased risk for accelerated lung function decline27,28 due to ongoing, and potentially intervenable, disease processes (e.g., airway inflammation) and may be a particularly attractive group for future therapeutic trials.

Underlying time-varying processes that may contribute to the enrichment of significant transitions among PRISm beyond airway inflammation remain largely uncharacterized. The relationship between body mass and PRISm has historically warranted and continues to deserve careful consideration. In this cohort, increased baseline BMI was associated with future significant transitions, and quantitative changes in BMI between study visits (phase 1 to phase 2, phase 2 to phase 3) were weakly correlated with changes in FEV1 % predicted and FVC % predicted (Pearson r = −0.1 to Pearson r = −0.2, respectively; data not shown). However, the magnitude of lung function changes associated with longitudinal changes in BMI were modest and were not significantly different by significant transition status (Table 2). These findings are consistent with previous literature which supports that absolute changes in FEV1 and FVC attributable to weight change are small (< 30 mL/kg).29 Even in cases of extreme weight loss (eg, bariatric surgery populations), average change in FEV1 % predicted and FVC % predicted values ranged from 4.1% to 7.6%.30,31 Therefore, the majority of significant transitions within this cohort are unlikely to be solely attributable to changes in body mass.

A second time-varying process which deserves consideration is change in smoking status. Approximately 20% of the analysis cohort had a change in smoking status during follow-up. Individuals who experienced a significant transition into PRISm were enriched for a change in smoking status between phase 1 and phase 2; the vast majority of individuals who changed smoking status between phase 1 and phase 2 quit smoking (data not shown). However, within the overall cohort, changes in smoking status were not differentially distributed by significant transition status. In post hoc analyses examining transitions associated with significant increases or decreases in lung function, and separately by quitting or resuming smoking at phase 1 to phase 2 or phase 2 to phase 3 separately, no significant associations were observed. These data are consistent with previous reports where changes in smoking status are typically associated with changes in lung function well below the ± 10% in % predicted values32, 33, 34 used to denote significant transitions in our analysis. A healthy smoker effect, in which individuals resistant to the effects of smoking on lung function may be more likely to continue smoking, may have limited our ability to detect an association with current smoking. However, we assert that factors other than changes in smoking status likely underly significant spirometric transitions in this cohort.

Comorbid conditions which predispose to fluid shifts (eg, CHF, CKD) may contribute to significant transitions. Individuals with CHF and CKD are known to have an increased prevalence of both PRISm and obstruction on spirometry35,36 with some reports of lung function abnormalities antedating the clinical diagnosis of cardiac and renal disease.35,37 In advanced stages, significant accumulation and shifts in corporeal fluid have been shown to be correlated with changes in spirometry.38,39 However, within this cohort, CHF and CKD at any time point were not associated with significant transitions, and associations with ever-PRISm remained robust after exclusion of individuals with CHF and/or CKD. We acknowledge limitations because of the self-reported nature of comorbidities and lack of clinical assessment of volume status during study visits; these topics should be explored in independent cohorts with more rigorous characterization of these conditions.

Individuals with significant spirometric transitions did not have differential rates of physician-diagnosed asthma, but were enriched for ever having a positive BDR during the study. Analogous to PRISm, BDR varies over time; while the cross-sectional prevalence of BDR remained consistent at each visit (∼18%), individual membership in the BDR responsive group was variable at each visit. Only one-third of individuals with a positive BDR at phase 1 or phase 2 demonstrated a BDR on consecutive visits, and only 6.4% of individuals with a positive BDR at any point demonstrated consistent BDR at all three visits. These findings are consistent with previous work in COPD populations where BDR was found to vary over time and was a poor predictor of clinical outcomes (mortality, acute exacerbations).40 Likewise, conflicting reports regarding the clinical impact of BDR on future lung function exist, with one study demonstrating no differences in the rate of FEV1 decline by BDR over 11 years of follow-up,41 and another study reporting attenuation of lung function decline among individuals with BDR.42 Most studies have, however, focused on the relationship between BDR and obstructive lung disease, rather than PRISm. In our analysis, the overlap between individuals positive for ever-BDR and ever-PRISm demonstrated a trend toward enrichment (P = .10, data not shown), but ever-PRISm remained a significant predictor of significant transitions independent of ever-BDR. Emerging work has suggested that the traditional definition of BDR may be relatively insensitive to associations with respiratory symptoms, functional capacity, quality of life, radiographic features, and clinical outcomes43,44; future studies using graded levels of BDR or examining BDR separately in FEV1 and FVC may allow for additional insights.

The strengths of our study include a large, rigorously phenotyped cohort with quantitative CT imaging, use of postbronchodilator spirometry, inclusion of significant numbers of Black participants, and an extended duration of follow-up. Our results were robust regardless of whether fixed ratio or LLN criteria were used and when increasingly stringent definitions of significant transitions were applied. Limitations of our study include the large number of subjects who did not have complete longitudinal data, including subjects with worse lung function at baseline, which raises the possibility of survivorship bias. Notably, in post hoc analyses, individuals who demonstrated a significant transition at phase 1 to phase 2 were less likely to enroll in phase 3 relative to those without significant transitions (27.4% vs 32.4%, χ2 P = .009); similarly, individuals who were ever-PRISm at phase 1 to phase 2 were less likely to participate in phase 3 (27.4% vs 32.7%, χ2 P = .001). Given the association between significant transitions and ever-PRISm remained significant at phase 1 to phase 2 (data not shown), we think loss to follow-up likely introduced bias toward the null and that our estimates of the strength of association in the full phase 1 to phase 3 cohort are likely conservative. Because enrollment criteria for COPDGene included a minimum cumulative cigarette smoke exposure, the relationship between PRISm and significant transitions in nonsmokers or smokers with < 10 pack-years of exposure could not be assessed. Although our study included substantial numbers of Black participants, individuals of other races and ethnicities were not enrolled. Finally, although the period of follow-up was considerable, spirometry was assessed at only three time points during the study; therefore, changes in lung function which occur on a more acute timeline could not be assessed. Future studies in independent cohorts with shorter intervals between assessments are warranted.

Interpretation

Our work establishes that, contrary to previous conceptualizations of PRISm as a stable spirometric abnormality, individual membership in PRISm is fluid, with frequent transitions to both obstruction and normal spirometry associated with significant changes in lung function over time. The strong association between PRISm and significant transitions is independent of changes in body mass, history of BDR, and changes in smoking status. Future work examining the time-varying processes, including genomic, quantitative imaging, and functional risk factors which contribute to these significant transitions is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: E. S. W. and E. K. S. assume responsibility for all aspects of the work presented herein. E. S. W. and E. K. S. participated in the concept, design, and primary analyses. B. J. M., D. L. D., and E. A. R. participated in data acquisition. J. E. H., K. A. Y., and J. D. C. participated in the interpretation of data. All authors participated in the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript and approve of the final version.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: B. J. M. reports grants, nonfinancial support, and other support from Astra Zeneca, Sunovion, and Glaxo Smith Kline; nonfinancial support from Spiration; other support from Mt. Sinai, Web MD, National Jewish Health, Novartis, American College of Chest Physicians, Projects in Knowledge, Hybrid Communications, Verona, Medscape, Boehringer Ingelheim, Theravance, Ultimate Medical Academy, Catamount Medical, Science 24/7, Eastern VA Medical Center, Eastern Pulmonary Society, and Academy Continued Health Care Learning; grants from Pearl Research and National Institutes of Health (NIH)/NHLBI; nonfinancial support and other support from Circassia and Phillips; personal fees and nonfinancial support from Third Pole; personal fees from Takeda; and royalties from Wolters Kluwer Health (UpToDate); outside the submitted work. E. S. W. reports grant support from the US Department of Veterans Affairs. J. D. C. reports grants from the NIH. D. L. D. reports grants from the NIH and personal fees from Bayer and Novartis, outside the submitted work. E. K. S. reports grants from the NIH related to the submitted work, and grants from Bayer and GlaxoSmithKline, outside the submitted work. S. E. M. reports grant support from the Chest Foundation and consulting fees from Quantitative Imaging Solutions, unrelated to the submitted work. R. S. J. E. reports grants from the NIH, during the conduct of the study; grants from Boehringer Ingelheim; personal fees from Chiesi and Leuko Labs, outside the submitted work; and is also a founder and co-owner of Quantitative Imaging Solutions, which is a company that provides image-based consulting and develops software to enable data sharing. None declared (J. E. H., E. A. R., K. A. Y.).

Role of sponsors: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, or the US Department of Veterans Affairs. The funders had no role in the conduct of the study, analysis of results, drafting of the manuscript, or decision to submit for publication.

∗COPDGene Collaborators: COPDGene Investigators – Core Units include the following: Administrative Center (James D. Crapo, MD [principal investigator]; Edwin K. Silverman, MD, PhD [principal investigator]; Barry J. Make, MD; and Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD); Genetic Analysis Center (Terri H. Beaty, PhD; Peter J. Castaldi, MD, MSc; Michael H. Cho, MD, MPH; Dawn L. DeMeo, MD, MPH; Adel El Boueiz, MD, MMSc; Marilyn G. Foreman, MD, MS; Auyon Ghosh, MD; Lystra P. Hayden, MD, MMSc; Craig P. Hersh, MD, MPH; Jacqueline Hetmanski, MS; Brian D. Hobbs, MD, MMSc; John E. Hokanson, MPH, PhD; Wonji Kim, PhD; Nan Laird, PhD; Christoph Lange, PhD; Sharon M. Lutz, PhD; Merry-Lynn McDonald, PhD; Dmitry Prokopenko, PhD; Matthew Moll, MD, MPH; Jarrett Morrow, PhD; Dandi Qiao, PhD; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD; Aabida Saferali, PhD; Phuwanat Sakornsakolpat, MD; Edwin K. Silverman, MD, PhD; Emily S. Wan, MD; and Jeong Yun, MD, MPH); Imaging Center (Juan Pablo Centeno, MSc; Jean-Paul Charbonnier, PhD; Harvey O. Coxson, PhD; Craig J. Galban, PhD; MeiLan K. Han, MD, MS; Eric A. Hoffman, PhD; Stephen Humphries, PhD; Francine L. Jacobson, MD, MPH; Philip F. Judy, PhD; Ella A. Kazerooni, MD; Alex Kluiber; David A. Lynch, MB; Pietro Nardelli, PhD; John D. Newell Jr, MD; Aleena Notary, MS; Andrea Oh, MD; Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD; James C. Ross, PhD; Raul San Jose Estepar, PhD; Joyce Schroeder, MD; Jered Sieren, MHA; Berend C. Stoel, PhD; Juerg Tschirren, PhD; Edwin Van Beek, MD, PhD; Bram van Ginneken, PhD; Eva van Rikxoort, PhD; Gonzalo Vegas Sanchez- Ferrero, PhD; Lucas Veitel, MBA; George R. Washko, MD; and Carla G. Wilson, MS); PFT QA Center, Salt Lake City, UT (Robert Jensen, PhD); Data Coordinating Center and Biostatistics, National Jewish Health, Denver, CO (Douglas Everett, PhD; Jim Crooks, PhD; Katherine Pratte, PhD; Matt Strand, PhD; and Carla G. Wilson, MS); Epidemiology Core, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO (John E. Hokanson, MPH, PhD; Erin Austin, PhD; Gregory Kinney, MPH, PhD; Sharon M. Lutz, PhD; and Kendra A. Young, PhD); Mortality Adjudication Core (Surya P. Bhatt, MD; Jessica Bon, MD; Alejandro A. Diaz, MD, MPH; MeiLan K. Han, MD, MS; Barry Make, MD; Susan Murray, ScD; Elizabeth Regan, MD; Xavier Soler, MD; and Carla G. Wilson, MS); and Biomarker Core (Russell P. Bowler, MD, PhD; Katerina Kechris, PhD; and Farnoush Banaei-Kashani, PhD). COPDGene Investigators – Clinical Centers include the following: Ann Arbor VA (Jeffrey L. Curtis, MD; and Perry G. Pernicano, MD); Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX (Nicola Hanania, MD, MS; Mustafa Atik, MD; Aladin Boriek, PhD; Kalpatha Guntupalli, MD; Elizabeth Guy, MD; and Amit Parulekar, MD); Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA (Dawn L. DeMeo, MD, MPH; Craig Hersh, MD, MPH; Francine L. Jacobson, MD, MPH; and George Washko, MD); Columbia University, New York, NY (R. Graham Barr, MD, DrPH; John Austin, MD; Belinda D’Souza, MD; and Byron Thomashow, MD); Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC (Neil MacIntyre Jr, MD; H. Page McAdams, MD; and Lacey Washington, MD); HealthPartners Research Institute, Minneapolis, MN (Charlene McEvoy, MD, MPH; and Joseph Tashjian, MD); Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD (Robert Wise, MD; Robert Brown, MD; Nadia N. Hansel, MD, MPH; Karen Horton, MD; Allison Lambert, MD, MHS; and Nirupama Putcha, MD, MHS); Lundquist Institute for Biomedical Innovation at Harbor UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA (Richard Casaburi, PhD, MD; Alessandra Adami, PhD; Matthew Budoff, MD; Hans Fischer, MD; Janos Porszasz, MD, PhD; Harry Rossiter, PhD; and William Stringer, MD); Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, Houston, TX (Amir Sharafkhaneh, MD, PhD; and Charlie Lan, DO); Minneapolis VA (Christine Wendt, MD; Brian Bell, MD; and Ken M. Kunisaki, MD, MS); Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA (Eric L. Flenaugh, MD; Hirut Gebrekristos, PhD; Mario Ponce, MD; Silanath Terpenning, MD; and Gloria Westney, MD, MS); National Jewish Health, Denver, CO (Russell Bowler, MD, PhD; and David A. Lynch, MB); Reliant Medical Group, Worcester, MA (Richard Rosiello, MD; and David Pace, MD); Temple University, Philadelphia, PA (Gerard Criner, MD; David Ciccolella, MD; Francis Cordova, MD; Chandra Dass, MD; Gilbert D’Alonzo, DO; Parag Desai, MD; Michael Jacobs, PharmD; Steven Kelsen, MD, PhD; Victor Kim, MD; A. James Mamary, MD; Nathaniel Marchetti, DO; Aditi Satti, MD; Kartik Shenoy, MD; Robert M. Steiner, MD; Alex Swift, MD; Irene Swift, MD; and Maria Elena Vega-Sanchez, MD); University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL (Mark Dransfield, MD; William Bailey, MD; Surya P. Bhatt, MD; Anand Iyer, MD; Hrudaya Nath, MD; and J. Michael Wells, MD); University of California, San Diego, CA (Douglas Conrad, MD; Xavier Soler, MD, PhD; and Andrew Yen, MD); University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA (Alejandro P. Comellas, MD; Karin F. Hoth, PhD; John Newell Jr, MD; and Brad Thompson, MD); University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI (MeiLan K. Han, MD, MS; Ella Kazerooni, MD, MS; Wassim Labaki, MD, MS; Craig Galban, PhD; and Dharshan Vummidi, MD); University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN (Joanne Billings, MD; Abbie Begnaud, MD; and Tadashi Allen, MD); University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA (Frank Sciurba, MD; Jessica Bon, MD; Divay Chandra, MD, MSc; and Joel Weissfeld, MD, MPH); and University of Texas Health, San Antonio, San Antonio, TX (Antonio Anzueto, MD; Sandra Adams, MD; Diego Maselli-Caceres, MD; Mario E. Ruiz, MD; and Harjinder Singh, MD).

Additional information: The e-Figures and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: The project described was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Awards U01 HL089897, U01 HL089856]. E. S. Wan is supported by a Career Development Award 2 from the US Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development [Award IK2RX002165]. R. San Jose Estepar is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Awards R01HL149877, R2HL140422] and the National Library of Medicine [Award R21LM013670]. COPDGene is also supported by the COPD Foundation through contributions made to an Industry Advisory Board that has included AstraZeneca, Bayer Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sunovion.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Wan E.S., Castaldi P.J., Cho M.H., et al. Epidemiology, genetics, and subtyping of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) in COPDGene. Respir Res. 2014;15(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0089-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Backman H., Eriksson B., Hedman L., et al. Restrictive spirometric pattern in the general adult population: methods of defining the condition and consequences on prevalence. Respir Med. 2016;120:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz A., Arnold N., Skinner B., et al. Preserved ratio impaired spirometry in a spirometry database. Respir Care. 2021;66(1):58–65. doi: 10.4187/respcare.07712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannino D.M., Buist A.S., Petty T.L., Enright P.L., Redd S.C. Lung function and mortality in the United States: data from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey follow up study. Thorax. 2003;58(5):388–393. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.5.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mannino D.M., McBurnie M.A., Tan W., et al. Restricted spirometry in the Burden of Lung Disease Study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(10):1405–1411. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerra S., Carsin A.E., Keidel D., et al. Health-related quality of life and risk factors associated with spirometric restriction. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(5) doi: 10.1183/13993003.02096-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcus B.S., McAvay G., Gill T.M., Vaz Fragoso C.A. Respiratory symptoms, spirometric respiratory impairment, and respiratory disease in middle-aged and older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(2):251–257. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaz Fragoso C.A., McAvay G., Van Ness P.H., et al. Phenotype of spirometric impairment in an aging population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(7):727–735. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201508-1603OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerra S., Sherrill D.L., Venker C., Ceccato C.M., Halonen M., Martinez F.D. Morbidity and mortality associated with the restrictive spirometric pattern: a longitudinal study. Thorax. 2010;65(6):499–504. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.126052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honda Y., Watanabe T., Shibata Y., et al. Impact of restrictive lung disorder on cardiovascular mortality in a general population: the Yamagata (Takahata) study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;241:395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scarlata S., Pedone C., Fimognari F.L., Bellia V., Forastiere F., Incalzi R.A. Restrictive pulmonary dysfunction at spirometry and mortality in the elderly. Respir Med. 2008;102(9):1349–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaz Fragoso C.A., Gill T.M., McAvay G., Yaggi H.K., Van Ness P.H., Concato J. Respiratory impairment and mortality in older persons: a novel spirometric approach. J Investig Med. 2011;59(7):1089–1095. doi: 10.231/JIM.0b013e31822bb213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wan E.S., Fortis S., Regan E.A., et al. Longitudinal phenotypes and mortality in preserved ratio impaired spirometry in the COPDGene study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(11):1397–1405. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201804-0663OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wijnant S.R.A., De Roos E., Kavousi M., et al. Trajectory and mortality of preserved ratio impaired spirometry: the Rotterdam Study. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(1) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01217-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iyer V.N., Schroeder D.R., Parker K.O., Hyatt R.E., Scanlon P.D. The nonspecific pulmonary function test: longitudinal follow-up and outcomes. Chest. 2011;139(4):878–886. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sood A., Petersen H., Qualls C., et al. Spirometric variability in smokers: transitions in COPD diagnosis in a five-year longitudinal study. Respir Res. 2016;17(1):147. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0468-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young K.A., Strand M., Ragland M.F., et al. Pulmonary subtypes exhibit differential global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease spirometry stage progression: the COPDGene® Study. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2019;6(5):414–429. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.6.5.2019.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wan E.S., Reglan M.F., Hokanson J.E., et al. Preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) is associated with increased rates of significant spirometric transitions among ever-smokers in the COPDGene study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(9):A4565. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Regan E.A., Hokanson J.E., Murphy J.R., et al. Genetic epidemiology of COPD (COPDGene) study design. COPD. 2010;7(1):32–43. doi: 10.3109/15412550903499522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffman E.A., Ahmed F.S., Baumhauer H., et al. Variation in the percent of emphysema-like lung in a healthy, nonsmoking multiethnic sample. The MESA lung study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(6):898–907. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-364OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mason S.E., Moreta-Martinez R., Labaki W.W., et al. Respiratory exacerbations are associated with muscle loss in current and former smokers. Thorax. 2021;76(6):554–560. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hankinson J.L., Odencrantz J.R., Fedan K.B. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(1):179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lung function testing: selection of reference values and interpretative strategies. American Thoracic Society. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144(5):1202–1218. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luoto J., Pihlsgard M., Wollmer P., Elmstahl S. Relative and absolute lung function change in a general population aged 60-102 years. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(3) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01812-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herpel L.B., Kanner R.E., Lee S.M., et al. Variability of spirometry in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from two clinical trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(10):1106–1113. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-975OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rozas C.J., Goldman A.L. Daily spirometric variability: normal subjects and subjects with chronic bronchitis with and without airflow obstruction. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142(7):1287–1291. doi: 10.1001/archinte.142.7.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhatt S.P., Soler X., Wang X., et al. Association between functional small airway disease and FEV1 decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(2):178–184. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201511-2219OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dransfield M.T., Kunisaki K.M., Strand M.J., et al. Acute exacerbations and lung function loss in smokers with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(3):324–330. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1014OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y., Horne S.L., Dosman J.A. Body weight and weight gain related to pulmonary function decline in adults: a six year follow up study. Thorax. 1993;48(4):375–380. doi: 10.1136/thx.48.4.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabrielsen A.M., Lund M.B., Kongerud J., et al. Pulmonary function and blood gases after gastric bypass and lifestyle intervention: a comparative study. Clin Obes. 2013;3(5):117–123. doi: 10.1111/cob.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hewitt S., Humerfelt S., Sovik T.T., et al. Long-term improvements in pulmonary function 5 years after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2014;24(5):705–711. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camilli A.E., Burrows B., Knudson R.J., Lyle S.K., Lebowitz M.D. Longitudinal changes in forced expiratory volume in one second in adults. Effects of smoking and smoking cessation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135(4):794–799. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.4.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lange P., Groth S., Nyboe G.J., et al. Effects of smoking and changes in smoking habits on the decline of FEV1. Eur Respir J. 1989;2(9):811–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu X., Weiss S.T., Rijcken B., Schouten J.P. Smoking, changes in smoking habits, and rate of decline in FEV1: new insight into gender differences. Eur Respir J. 1994;7(6):1056–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jankowich M., Elston B., Liu Q., et al. Restrictive spirometry pattern, cardiac structure and function, and incident heart failure in African Americans. The Jackson Heart Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(10):1186–1196. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201803-184OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Navaneethan S.D., Mandayam S., Arrigain S., Rahman M., Winkelmayer W.C., Schold J.D. Obstructive and restrictive lung function measures and CKD: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007-2012. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(3):414–421. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.03.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sumida K., Kwak L., Grams M.E., et al. Lung function and incident kidney disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(5):675–685. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chase S.C., Fermoyle C.C., Wheatley C.M., Schaefer J.J., Olson L.J., Johnson B.D. The effect of diuresis on extravascular lung water and pulmonary function in acute decompensated heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2018;5(2):364–371. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yilmaz S., Yildirim Y., Yilmaz Z., et al. Pulmonary function in patients with end-stage renal disease: effects of hemodialysis and fluid overload. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:2779–2784. doi: 10.12659/MSM.897480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albert P., Agusti A., Edwards L., et al. Bronchodilator responsiveness as a phenotypic characteristic of established chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2012;67(8):701–708. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anthonisen N.R., Lindgren P.G., Tashkin D.P., et al. Bronchodilator response in the Lung Health Study over 11 yrs. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(1):45–51. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00102604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park H.Y., Lee S.Y., Kang D., et al. Favorable longitudinal change of lung function in patients with asthma-COPD overlap from a COPD cohort. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0737-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fortis S., Comellas A., Make B.J., et al. Combined forced expiratory volume in 1 second and forced vital capacity bronchodilator response, exacerbations, and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(7):826–835. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201809-601OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansen J.E., Dilektasli A.G., Porszasz J., et al. A new bronchodilator response grading strategy identifies distinct patient populations. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(12):1504–1517. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201901-030OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.