To the Editor:

Among adults ages 55 to 80 years with a history of substantial firsthand cigarette smoke exposure, lung cancer screening (LCS) with the use of annual low-dose CT (LDCT) reduces the relative risk of lung cancer death, is widely recommended, and is reimbursed by most insurance carriers.1 However, most eligible people do not receive an LDCT for screening or a shared decision-making interaction before an LDCT scan, as required by insurers.2 In particular, people from rural settings may have limited access to high-quality LCS processes compared with non-rural counterparts.3,4

Most facilities that offer LDCT for LCS use a decentralized referral process that relies on referring clinicians, usually primary care providers (PCPs), to have a decision interaction and to manage follow-up procedures after the LDCT.5 We conducted this study to determine (1) what aspects of high-quality LCS were provided by PCPs from rural and non-rural communities and (2) how PCPs viewed LDCT implementation and what processes might increase the number of patients who engage in LCS.

Methods

Survey and Recruitment

We developed a survey to assess Oregon PCPs’ (including physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) attitudes about LCS and practices in their clinic. To assure representation of rural PCPs, we partnered with the Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network.6 We serially tested the survey within our research group and five PCPs (average completion time, 7 minutes). The final survey included 30 items. The survey included questions regarding the PCP’s practice setting and what components of recommended high-quality LCS7 that they or their clinic staff provided. We used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to assess attitudes about LCS implementation, with questions reliant on individual perceptions.8 Finally, we developed questions regarding potential facilitators to increase the number of patients who engage in LCS by using a five-point scale from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree.” PCPs could complete a paper or online version of the survey.

There is no publicly available resource that includes all Oregon PCPs (estimated at approximately 5,000, based in 710 clinics in rural and non-rural settings9), so we used several methods to distribute the survey that included listserv software (L-Soft International Inc) distribution, outreach to professional organizations, and direct mailing from June to September 2020. We included links to the online version of the survey in digital newsletters and listservs from the following organizations: Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network (641 recipients); Oregon Academy of Family Physicians (2,000 recipients); Oregon Office of Rural Health (unknown recipients); American Cancer Society (unknown recipients); the Oregon Primary Care Association, which serves all 34 of Oregon’s Federally Qualified Health Centers (98 recipients); and the Oregon Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes Network (2,487 recipients). We requested that only PCPs complete the survey, but many listservs included nonclinician administrators and public health leaders. We also reached out to key personnel from Oregon’s Medicaid Health Plans and local public health authorities to send the surveys within their network.

The study was approved by the VA Portland Health Care System and Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board (#4005/18865). Participants assented to participate by completing the survey and were not reimbursed.

Analysis

We report descriptive statistics only. For questions that assess the degree of agreement, we combined responses of “Strongly Disagree” with “Disagree” and “Strongly Agree” with “Agree.” We classified facility zip codes using Oregon Health Department rurality designation data10 and condensed rural and frontier zip codes to “rural” with the remainder designated as “non-rural.”

Results

We received responses from 50 rural (65%) and 27 non-rural PCPs (Table 1), representing 62 unique clinics, which represents 9% of PCP clinics. One question had 14% missing responses (noted in Table 1); the remaining responses had < 10% missing. Most respondents (87%) referred patients for LDCT for LCS; 40% referred them outside their primary location. The top three reasons for referring outside were patient preference, closest location, and the patient’s insurance. More than one-half of respondents (65%) used electronic health record reminders/alerts to help determine patient eligibility.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 77)

| Characteristics | Rurala (n = 50) | Not Rurala (n = 27) |

|---|---|---|

| Credentials, No. (%)b | ||

| Advanced Practice Nurse | 18 (36) | 6 (22) |

| Physician | 24 (48) | 19 (70) |

| Physician Assistant | 7 (14) | 2 (8) |

| Other | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Racial background, No. (%) | ||

| Non-White | 7 (14) | 3 (12) |

| White | 40 (80) | 21 (81) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (6) | 2 (8) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Female | 30 (63) | 16 (59) |

| Male | 15 (31) | 8 (30) |

| Sex variant/nonconforming | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (6) | 2 (7) |

| Missing | 2 | 0 |

| Spanish, Hispanic, or Latino, No. (%) | ||

| Yes | 1 (2) | 0 |

| No | 43 (90) | 25 (93) |

| Prefer not to answer | 4 (8) | 2 (7) |

| Missing | 2 | 0 |

| Average years of practice, mean ± SD | 18.3 ± 12.6 | 18.7 ± 12.8 |

| Days per week subjects see patients, No. (%) | ||

| ≤3.5 | 15 (30) | 10 (40) |

| >4 | 35 (70) | 15 (60) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 |

| Leadership role | ||

| No | 31 (63) | 17 (63) |

| Yes | 18 (37) | 10 (37) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Medical director | 6 (35) | 6 (60) |

| Quality improvement | 1 (6) | 0 |

| Other | 10 (59) | 4 (40) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Type of lung cancer screening referrals made, No. (%) | ||

| LDCT only | 29 (58) | 17 (63) |

| LDCT and other screening methods | 14 (28) | 7 (26) |

| Other screening methods | 7 (14) | 3 (11) |

| Average no. of LDCT referrals made per month, No. (%) | ||

| 0 | 11 (23) | 6 (22) |

| 1-3 | 28 (58) | 16 (59) |

| 4-6 | 6 (13) | 5 (19) |

| ≥7 | 3 (6) | 0 |

| Missing | 2 | 0 |

| Do you refer outside of primary location? Yes, No. (%) | 13 (29) | 18 (69) |

| No. of subjects who indicated they refer patients for LDCT screening based on the following indications,c No. (%) | ||

| Patient’s preference | 33 | 20 |

| Closest location | 32 | 15 |

| Patient’s insurance | 23 | 22 |

| My institution | 18 | 4 |

| Affiliated institution | 7 | 3 |

| Other | 5 | 5 |

| Reputation | 3 | 1 |

| Personal connection | 2 | 0 |

| How many providers chose at least one of the top three reasons? No. (%) | 33 (66) | 21 (78) |

| Type of reminder used to determine eligibility for lung cancer screening, No. (%) | ||

| EHR reminder | 31 (66) | 19 (68) |

| No reminders, alerts, or flags | 13 (28) | 7 (25) |

| Other platform | 2 () | 2 (7) |

| Don’t know | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Missing | 3 | 0 |

| Role of staff within lung cancer screening, No. (%) | ||

| Who does the shared decision-making interaction when the patient decides whether to get lung cancer screening? | ||

| Respondent | 43 (96) | 25 (96) |

| Clinic staff | 2 (4) | 1 (4) |

| Radiology facility | 0 | 0 |

| No one | 0 | 0 |

| I don’t know | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 5 | 1 |

| Who is responsible for follow up with patients to ensure they complete their baseline LDCT scan? No. (%) | ||

| Respondent | 12 (27) | 7 (27) |

| Clinic staff | 20 (44) | 12 (46) |

| Radiology facility | 4 (9) | 0 |

| No one | 8 (18) | 5 (19) |

| I don’t know | 1 (2) | 2 (8) |

| Other | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 5 | 1 |

| Who makes sure that patients follow the recommendations from the baseline LDCT scan?d No. (%) | ||

| Respondent | 28 (64) | 19 (73) |

| Clinic staff | 11 (25) | 3 (12) |

| Radiology facility | 3 (7) | 2 (8) |

| No one | 1 (2) | 0 |

| I don’t know | 1 (2) | 1 (4) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Missing | 6 | 1 |

| Who ensures patients are not lost to follow up?e No. (%) | ||

| Respondent | 11 (24) | 5 (19) |

| Clinic staff | 18 (40) | 9 (35) |

| Radiology facility | 2 (4) | 5 (19) |

| No one | 10 (22) | 4 (15) |

| I don’t know | 3 (7) | 3 (12) |

| Other | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Missing | 5 | 1 |

| Who refers a patient to other providers when the LDCT result suggests lung cancer?f No. (%) | ||

| Respondent | 42 (93) | 25 (96) |

| Clinic staff | 3 (7) | 1 (4) |

| Radiology facility | 0 | 0 |

| No one | 0 | 0 |

| I don’t know | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 5 | 1 |

| Who uses a registry (paper or electronic) to track patients who undergo LDCT lung cancer screening?g No. (%) | ||

| Respondent | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Clinic staff | 9 (22) | 4 (16) |

| Radiology facility | 4 (10) | 3 (12) |

| No one | 17 (41) | 11 (44) |

| I don’t know | 9 (22) | 6 (24) |

| Other | 2 (5) | 0 |

| Missing | 9 | 2 |

LDCT = low-dose CT.

We determined rurality using facility zip codes and Oregon Health Department rurality designation data.

Contains nonmissing data and may not equal 100% because of rounding.

Subjects were allowed to pick their top three reasons.

A patient has a nodule found on the initial scan and is recommended to receive a 6-month follow-up LDCT.

The patient comes back for the annual LDCT scan.

Referring a patient to a pulmonologist for a nodule.

More than 10% missing responses.

Consistent with the use of decentralized programs, almost all (88%) of the respondents conducted the decision-making interaction themselves and were responsible for referring patients with suspicious findings to other providers (87%) (Table 1). Participants reported that they or their staff were most often responsible for ensuring that patients completed the LDCT, following up on surveillance recommendations, and ensuring adherence to annual follow-up LDCT scans. Most responding PCPs (56%) either did not use a registry to track patients for follow-up or did not know if one was used.

With respect to aspects of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research domains, most respondents agreed that fellow PCPs in their practice agreed with the goals of LCS and were informed and involved in the use of LDCT for LCS (Table 2). There was less agreement on the use of adequate resources and prioritization of the success of LCS. Most agreed there is strong evidence that LCS reduces lung cancer mortality rates.

Table 2.

Selected Consolidated Framework for the Implementation of Research Questions

| Fellow primary care providers in your clinic… No. (%)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | Agree on the goals for lung cancer screening using LDCT | Informed and involved in lung cancer screening using LDCT | Agree on adequate resources (ie, registries and staff to track patients, No. of available CT scanners, etc) to accomplish lung cancer screening using LDCT | Set a high priority on the success of lung cancer screening using LDCT |

| Ruralb | ||||

| Agree | 27 (57%) | 26 (57%) | 18 (39%) | 14 (30%) |

| Neutral | 17 (36%) | 14 (30%) | 20 (43%) | 17 (36%) |

| Disagree | 3 (6%) | 6 (13%) | 7 (15%) | 16 (34%) |

| Not rural | ||||

| Agree | 18 (69%) | 18 (69%) | 11 (44%) | 5 (20%) |

| Neutral | 4 (15%) | 7 (27%) | 7 (28%) | 10 (40%) |

| Disagree | 4 (15%) | 1 (4%) | 7 (28%) | 10 (40%) |

| Lung cancer screening using LDCT has been proven to reduce lung cancer mortality in routine-care settings, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | How would you rate the strength of the evidence for the [statement above]? | How do you think your colleagues in your clinic would rate the strength of evidence for the [statement above]? |

| Rural | ||

| Weak | 2 (4%) | 3 (6%) |

| Neutral | 5 (10%) | 11 (22%) |

| Strong | 33 (66%) | 24 (48%) |

| Don’t know/NA | 7 (14%) | 12 (24%) |

| Not rural | ||

| Weak | 6 (22%) | 2 (8%) |

| Neutral | 4 (15%) | 10 (38%) |

| Strong | 17 (63%) | 10 (38%) |

| Don’t know/NA | 0 | 4 (15%) |

LDCT = low-dose CT; NA = not applicable.

No. (%) of nonmissing data

We determined rurality using facility zip codes and Oregon Health Department Rurality Designation Data

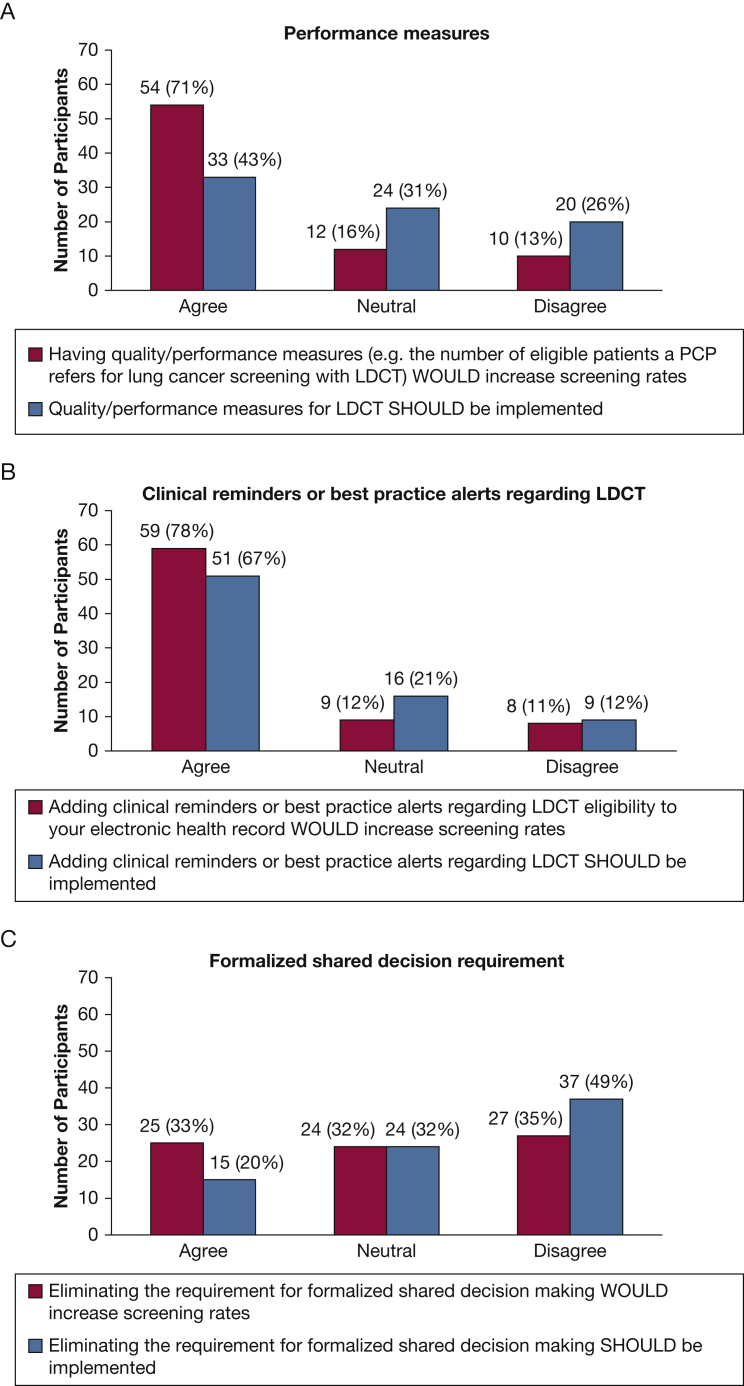

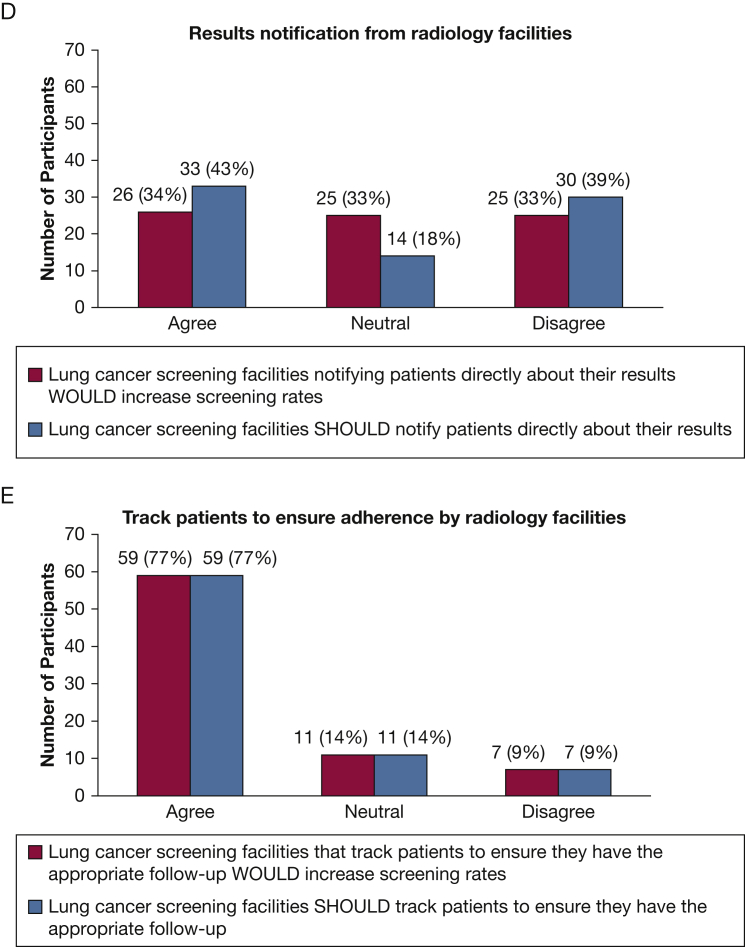

Figure 1 summarizes participant responses regarding recommended strategies that would improve implementation of LDCT for LCS. Notably, 71% of respondents agreed that implementing LDCT performance measures would help, but only 43% reported that they should be required. Only 20% of the respondents reported the requirement for shared decision-making should be eliminated. Three-quarters of the respondents reported that it would help if radiology facilities tracked adherence; the same percentage (77%) reported they should take this step.

Figure 1.

A-E, Which strategies WOULD increase lung cancer screening implementation compared with which SHOULD be implemented The Figure displays the number and percent of participants who reported a certain measure or intervention WOULD improve the number of people who receive lung cancer screening with the use of low-dose CT scans compared with how many reported that this measure or intervention SHOULD be implemented. LDCT = low-dose CT scan.

Discussion

Among Oregon PCP survey participants, 65% were from rural settings; most participants reported that they referred patients for LDCT for LCS and did most of the care processes themselves, although most did not use a registry to help with these burdens. These results mirror our study of Oregon radiology facility LDCT for LCS practices.5 Most respondents reported that implementing LCS decision support tools and radiology facility patient tracking would help increase the number of patients who undergo LDCT for LCS and should be started.

Our study has limitations. We received responses from PCPs across Oregon that represented 9% of primary care clinics with a high percentage of rural respondents, but the overall response rate was low. We could not verify that all respondents were PCPs. There are no comparable data outside of Oregon. Most of our respondents reported the use of LDCT for LCS, so our findings may not be generalizable to PCPs who are not engaged in LCS.

Acknowledgments

Other contributions: We acknowledge Julia Mabry, MS, MPH, for her help with this study.

Role ofsponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL/NONFINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: C.G. S. is the co-director of his facility’s lung cancer screening program and does not receive financial compensation for that role; he has no professional affiliation with any study participant. He served on the American Lung Association panel to develop an online toolkit to support lung cancer screening efforts and received no financial compensation for that role; he started serving on the American Cancer Society, National Lung Cancer Round Table, Lung Cancer Screening Implementation Strategies Task Group in July 2020. None declared (S. E. G., T. T., M. P., S. B., J. S., M. D.).

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This project was supported by the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA069533. It was also supported by resources from the VA Portland Health Care System, Portland, Oregon. Dr. Davis’ time is supported in part by a career development award from the National Cancer Institute (1K07CA211971-01A1)

DISCLAIMER: The Department of Veterans Affairs did not have a role in the conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of data; or in the preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

References

- 1.Moyer V.A. Force USPST. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):330–338. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zgodic A., Zahnd W.E., Miller D.P., Jr., Studts J.L., Eberth J.M. Predictors of lung cancer screening utilization in a population-based survey. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(12):1591–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tailor T.D., Tong B.C., Gao J., Choudhury K.R., Rubin G.D. A geospatial analysis of factors affecting access to CT facilities: implications for lung cancer screening. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(12):1663–1668. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odahowski C.L., Zahnd W.E., Eberth J.M. Challenges and opportunities for lung cancer screening in rural America. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(4 Pt B):590–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slatore C.G., Golden S.E., Thomas T., Bumatay S., Shannon J., Davis M. It’s really like any other study”: rural radiology facilities performing low-dose computed tomography for lung cancer screening. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(12):2058–2066. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202103-333OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis M.M., Gunn R., Kenzie E., et al. Integration of improvement and implementation science in practice-based research networks: a longitudinal, comparative case study. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(6):1503–1513. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06610-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazzone P.J., Silvestri G.A., Patel S., et al. Screening for lung cancer: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2018;153(4):954–985. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damschroder L.J., Aron D.C., Keith R.E., Kirsh S.R., Alexander J.A., Lowery J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;(4):50–65. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Authority O.H. Oregon Health Authority; Portland, OR: 2017. Oregon’s Primary Care Workforce: Based on data collected during 2015 and 2016.https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/ANALYTICS/HealthCareWorkforceReporting/03_PrimaryCareWorkforce_2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oregon Health & Science University Oregon Office of Rural Health Geographic Definitions. https://www.ohsu.edu/oregon-office-of-rural-health/about-rural-and-frontier-data