Abstract

Background

In the western world, 10–15% of women of child-bearing age suffer from iron-deficiency anemia. Iron overload due to chronic treatment with blood transfusions or hereditary hemochromatosis is much rarer.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent publications retrieved by a selective search on the pathophysiology, clinical features, and diagnostic evaluation of iron deficiency and iron overload.

Results

The main causes of iron deficiency are malnutrition and blood loss. Its differential diagnosis includes iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA), a rare congenital disease in which the hepcidin level is pathologically elevated, as well as the more common anemia of chronic disease (anemia of chronic inflammation), in which increased amounts of hepcidin are formed under the influence of interleukin-6 and enteric iron uptake is blocked as a result. Iron overload comes about through long-term transfusion treatment or a congenital disturbance of iron metabolism (hemochromatosis). Its diagnostic evaluation is based on clinical and laboratory findings, imaging studies, and specific mutation analyses.

Conclusion

Our improving understanding of the molecular pathophysiology of iron metabolism aids in the evaluation of iron deficiency and iron overload and may in future enable treatment not just with iron supplementation or iron chelation, but also with targeted pharmacological modulation of the hepcidin regulatory system.

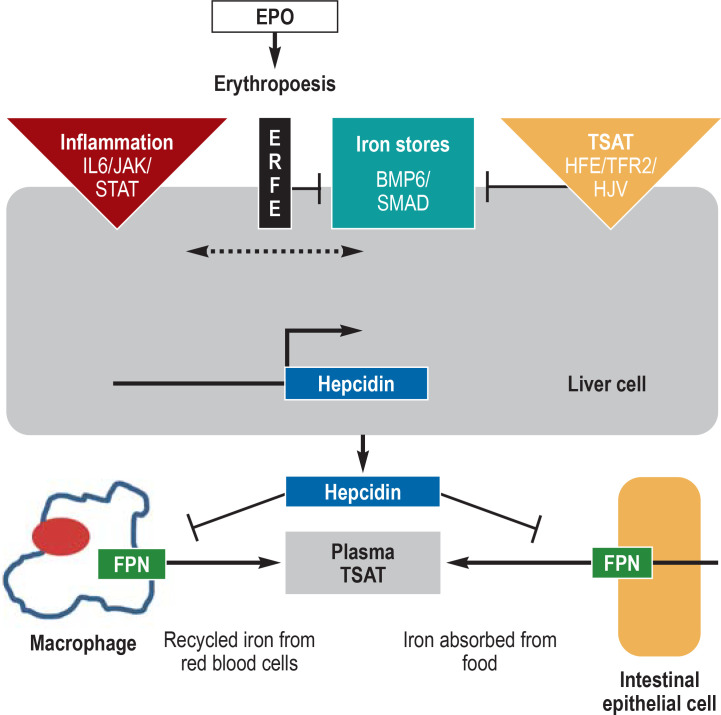

Vital cellular processes such as energy acquisition or oxygen transport require an adequate supply of iron. Transferrin saturation (TSAT) is an important biomarker of iron availability. Iron deficiency is present if the TSAT is less than 20%, and iron overload if it exceeds 40%. At TSAT levels above 60%–70%, so-called free iron is formed, which mainly damages hepatic parenchymal cells. Plasma iron levels are regulated by the hepcidin/ferroportin system. Hepcidin is a peptide hormone produced in the liver. It circulates in plasma and binds to the iron export protein ferroportin, inducing its degradation. Ferroportin is expressed primarily in duodenal mucosa cells, liver cells, and macrophages; it mediates the regulation of dietary iron absorption (1–2 mg per day), iron release from the liver (as needed), and iron recycling in macrophages (20–25 mg per day). When adequate iron is available, the liver produces hepcidin, which blocks further iron absorption from food. When iron stores are empty, hepcidin production is inhibited, so that ferroportin-mediated iron export from the duodenal mucosal cells and the transfer of iron to transferrin can proceed unimpeded (1, 2).

Transferrin saturation.

Transferrin saturation (TSAT) is an important biomarker of iron availability. Iron deficiency is present if the TSAT is less than 20%, and iron overload if it exceeds 40%. At TSAT levels above 60%–70%, so-called free iron is formed, which mainly damages hepatic parenchymal cells.

Hepcidin/ferroportin regulatory system.

Disorders in the hepcidin/ferroportin regulatory system cause diseases associated with iron deficiency or iron overload. In hereditary hemochromatosis (HH), too little hepcidin is produced. The most common form of HH is caused by mutations in the HFE genet.

Disorders in the hepcidin/ferroportin regulatory system cause diseases associated with iron deficiency or iron overload. In hereditary hemochromatosis (HH), too little hepcidin is produced. The most common form of HH is caused by mutations in the HFE gene; rarer forms of HH are due to mutations in the transferrin receptor (TfR)2, hemojuvelin (HJV), hepcidin, or ferroportin genes. The hepcidin deficiency resulting from these mutations leads to excess absorption of dietary iron (3). Hepcidin formation is also diminished in iron-loading anemias (4). For example, in ß-thalassemia, mutations in both ß-globin genes lead to insufficient production of normal hemoglobin and impaired red blood cell function. Without adequate transfusion therapy, the resulting hypoxia induces increased production of erythropoietin (EPO), which stimulates the proliferation of erythropoietic progenitor cells in the bone marrow in an attempt to compensate for the anemia. This attempt, however, is ineffective. When erythropoiesis is ineffective, hepcidin production in the liver is inhibited by erythroferrone (ERFE), which is produced in erythroblasts under the influence of EPO (5). ERFE inhibits the so-called bone morphogenetic protein/small-body-size mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 1 (BMP/SMAD) signaling pathway by binding and inactivating BMP cytokines, which are produced in hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells (6). In ß-thalassemia, ERFE increases iron uptake by downregulating hepcidin production in the liver. In contrast, the anemia of chronic disease (inflammatory anemia) is characterized by abnormally high hepcidin levels due to the effect of interleukin 6 (IL-6), which activates the hepcidin-regulating Janus kinase (JAK) / signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) signaling pathway in liver cells. The increased hepcidin levels block iron release from storage cells and intestinal mucosa cells and thereby lead to a decrease in transferrin saturation (TSAT), as is often seen in the setting of inflammation (6).

Aside from malnutrition and blood loss, there are also rare genetic conditions that cause iron deficiency. Mutations in the serine protease TMPRSS6 (transmembrane protease serine 6, or matriptase-2) elevate the hepcidin concentration, leading to iron-refractory iron-deficiency anemia (IRIDA). TMPRSS6 normally induces the degradation of HJV and thus lessens the activity of the BMP/SMAD pathway; TMPRSS6 mutations enhance signaling activity and raise hepcidin levels. In both inflammatory anemia and IRIDA, hepcidin inhibits the intestinal absorption of iron and the release of recycled iron from macrophages, making patients refractory to oral iron supplementation and less responsive to intravenous iron supplementation (7).

Learning objectives

This article is intended to enable readers to

understand the key elements of the regulation of systemic iron metabolism,

be able to diagnose three stages of iron deficiency on the basis of appropriate laboratory parameters, and

know the main causes of iron overload and its proper diagnostic investigation.

Iron deficiency

Clinical features

BMP/SMAD signaling pathway.

Erythroferrone inhibits the so-called bone morphogenetic protein/small-body-size mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 1 (BMP/SMAD) signaling pathway by binding and inactivating BMP cytokines, which are produced in hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells.

Prevalence.

Around the world, approximately 40% of pregnant women and children under 5 years of age, as well as approximately 30% of nonpregnant women, suffer from iron deficiency due to malnutrition and from the resulting anemia. Iron deficiency is also the most common cause of anemia in Europe, affecting 2%–6% of children.

Around the world, approximately 40% of pregnant women and children under 5 years of age, as well as approximately 30% of non-pregnant women, suffer from iron deficiency due to malnutrition and from the resulting anemia (8, 9). Iron deficiency is also the most common cause of anemia in Europe, affecting 2%–6% of children (10) and 10%–15% of women of childbearing age (9). Vegetarian and vegan diets have become more widespread in recent years and are an increasingly common cause of iron deficiency (11). Chronic bleeding is another common cause, malabsorption syndromes are less common, and genetic disorders of iron absorption and iron homeostasis are rare.

Complications.

A growing number of studies indicate that iron deficiency may be associated with neurocognitive dysfunction and behavioral problems in both children and adults. Iron deficiency is also a treatable risk factor for heart failure with an adverse course.

The main manifestations of iron deficiency are pallor and fatigue resulting from hypochromic-microcytic anemia, which is characterized by anisocytosis in blood smears and by increased red cell distribution width (RDW) in electronic cell counting. Patients with severe iron deficiency may have oral fissures, diffuse alopecia, and atrophic glossitis, and sometimes pica, i.e., the compulsive ingestion of non-food items, such as soil (12). A growing number of studies indicate that iron deficiency may be associated with neurocognitive dysfunction and behavioral problems in both children and adults (13). It is the most common cause of hypochromic–microcytic anemia, and is also a treatable risk factor for heart failure with an adverse course (14, 15). In infants and young children, iron deficiency usually does not manifest itself in anemia until the second half of the first year of life, when the reserves laid down during gestation are depleted and rapid growth leads to an increased iron requirement. A second incidence peak occurs in girls during puberty, when the growth spurt coincides with blood loss from menstruation (12). Later on, pregnancy is the main risk factor for iron deficiency. A proper diet, preferably including meat, is recommended to prevent iron deficiency at times of increased need for iron, e.g., during puberty or pregnancy. Persons on a vegetarian or (especially) vegan diet should take care to supplement their diets with iron salts.

Iron deficiency due to blood loss and infection.

The primary possible causes are hypermenorrhea, excessively frequent blood donation, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Helicobacter pylori infection can also be a cause. Long-term diminution of gastric acid production by proton pump inhibitors or histamine-2 receptor antagonists impairs iron absorption in the duodenum.

The clinical investigation must include a search for causes of blood loss leading to iron deficiency. Possible causes are hypermenorrhea, excessively frequent blood donation, or gastrointestinal bleeding; fecal occult blood should be tested for, and gastrointestinal endoscopy should be performed if indicated. Helicobacter pylori infection can also cause iron deficiency. Moreover, the long-term diminution of gastric acid production by proton pump inhibitors or histamine-2 receptor antagonists impairs iron absorption in the duodenum.

Classification of iron deficiency.

Stage I: negative iron balance/stored iron deficiency/no hematological disorder; stage II: iron deficiency with undersupply of erythropoetic precursors int he bone marrow; stage III: iron-deficiency anemia, hemoglobin below reference range.

Classification

Negative iron balance leads first to a deficiency of stored iron (stage I), which is not yet harmful to the patient, at least in terms of blood counts. Iron deficiency becomes clinically relevant when there is too little iron to meet the needs of the erythropoietic precursors in the bone marrow: this is the stage of iron-deficient erythropoiesis (stage II). Finally, when the hemoglobin value falls below the lower limit of normal, the negative iron balance has reached stage III, or iron-deficiency anemia. This staging system is based on erythropoiesis because there are reliable parameters for assessing the iron supply to the erythropoietic system, at least in otherwise healthy individuals, while there are none at present for assessing the iron supply to other iron-dependent systems in the human organism. For these other systems, an inadequate iron supply is suspected if there are corresponding clinical manifestations, such as fatigue, lack of concentration, or hair loss, which improve after iron supplementation.

Diagnosis

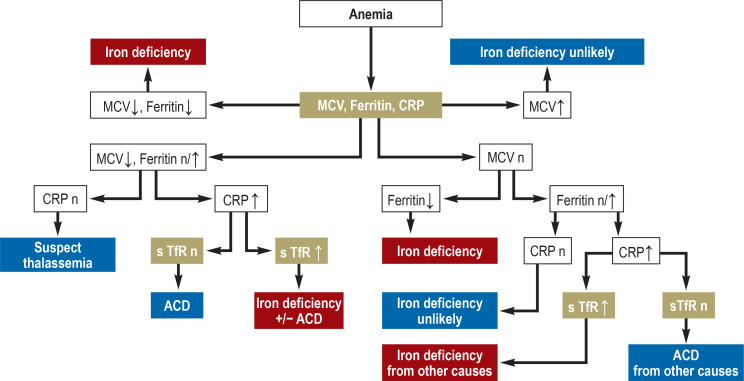

Various „iron tests“ (table 1) are available that provide different kinds information. The ferritin level reflects iron stores, but says nothing about iron supply to the erythropoietic system. For this, other parameters must be used, such as intra-erythrocytic zinc protoporphyrin (ZPP), soluble transferrin receptors (sTfR), hypochromic erythrocytes (HYPO), or reticulocyte hemoglobin (CHr). Low transferrin saturation is indirect evidence of an inadequate iron supply to erythropoiesis; in this situation, a hemoglobin level below the lower limit of normal as defined by the WHO (for women: 120 g/L; for men: 130 g/L) indicates iron-deficiency anemia. Through the use of multiple, complementary parameters, iron status can be adequately characterized and its clinical relevance assessed (Table 2 and diagnostic algorithm in Figure 2).

Table 1. Laboratory parameters for the investigation of iron deficiency.

| Parameter | Reference value |

| Bone marrow iron stores *1 | 2 |

| Bone marrow sideroblasts | 15%–50% |

| Hemoglobin | Women: 12.3–15.3 g/dL Men: 14.0–17.5 g/dL |

| MCV | 80–96 fl |

| MCH | 28–33 pg |

| Hypochromic erythrocytes | <2.5% |

| Reticulocyte hemoglobin | ≥ 26 pg |

| Ferritin | Women: 15–150 µg/L Men: 30–200 µg/L |

| Transferrin | 200–400 mg/dL |

| Transferrin saturation | 16%–45% |

| Soluble transferrin receptors (sTfR)*2 | 0.76–1.76 mg/dL |

| TfR index*3 | Women: 0.6–3.8 Men: 0.2–3.7 |

| Zinc protoporphyrin | ≤ 40 µmol/mol heme |

*1 Scale of 0 – 4

*2 Reference values depend on the test, in this case Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany;

*3 sTfR assay by Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany;

The German-language Onkopedia Guidelines provide a more detailed characterization of the listed parameters and their respective meaning in the context of iron deficiency investigation.

Table 2. Assessing iron status through the use of multiple, complementary parameters.

|

Patient

no. |

Hb g/L |

MCV fL |

sTfR mg/L |

ZPP* µmol/moL hemoglobin |

Ferritin µg/L |

Clinical findings | Diagnosis |

| 1 | 140 | 83 | 1.2 | 38 | 12 | Hemorrhoidal bleeding, male adult | Stored iron deficiency |

| 2 | 121 | 79 | 2.2 | 120 | 9 | Hypermenorrhea | Iron-deficient EP |

| 3 | 71 | 73 | 4.2 | 438 | 2 | Hypermenorrhea | Iron-deficiency anemia |

| 4 | 142 | 92 | 1.5 | 29 | 1 | Fe(II) p.o. for previous 3 months | Ongoing depleted iron storage |

| 5 | 132 | 82 | 2.0 | 132 | 32 | 100 mg Fe(II) p.o. irregularly | Iron-deficient EP, fatigue |

| 136 | 88 | 0.9 | 56 | 28 | 3 months after 500 mg Fe(III) i.v. | Patient free of symptoms | |

| 132 | 87 | 1.9 | 95 | 9 | 3 months later without replacement | Iron-deficient EP, fatigue | |

| 6 | 77 | 76 | 1.2 | 156 | 438 | Weight loss, B symptoms | ACD |

| 7 | 145 | 87 | 1.1 | 20 | 2856 | Iron overload | Hereditary hemochromatosis |

* The markers of iron-deficient erythropoiesis (sTfR and ZPP) play a key role in the clinical assessment of iron metabolism, in that their rise marks

the transition from stored iron deficiency to iron undersupply at cellular level.

Patients 1 and 2 both have depleted iron stores but are not yet anemic; however, patient 2 is already clearly showing iron-deficient EP (elevated ZPP).

Patient 3 has severe iron-deficiency anemia.

Patient 4 has been taking 100 mg Fe(II) p.o. for 3 months for iron-deficiency anemia; hemoglobin is now high-normal and iron-deficient EP is no longer present, but iron stores are still completely depleted.

Patient 5 complained of fatigue and lassitude. She was not anemic and ferritin was normal, but there was marked iron-deficient EP. Three months after administration of 500 mg iron i.v., the EP iron supply had returned to normal and the patient was symptom-free. After a 3-month break in therapy, the patient complained again of fatigue, understandably because the iron-deficient EP had recurred.

Patient 6, with polymyalgia rheumatica, shows the classic laboratory pattern of an ACD (elevated ZPP, normal sTfR). Patient 7, with hereditary hemochromatosis, shows excess iron stores (ferritin strongly elevated) and an above-average iron supply for EP (ZPP and sTfR low).

ACD, Anämie der chronischen Erkrankungen; EP, Erythropoese; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor; ZPP, zinc protoporphyrin

Reference values: ferritin 15–150 µg/L (women), 15–200 µg/L (men); sTfR: 0.8–1.8 mg/L; ZPP: ≤ 40 µmol/mol heme.

Figure 2.

Diagnostic algorithm for patients with suspected iron-deficiency anemia

ACD, anemia of chronic disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; MCV, mean corpuscular volume;

sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor; n, normal

In iron-deficient erythropoiesis, hemoglobin production is diminished and eventually anemia is the result. Iron deficiency accounts for at least 50% of all cases of anemia around the world (16, 17) and must therefore always be considered at the top of the list of differential diagnoses, particularly in patients with hypochromic-microcytic anemia with low erythrocyte indices (MCV, MCH). Further differential diagnoses with this pattern of laboratory findings include congenital hemoglobinopathies, primarily the thalassemias.

Routine screening test for iron metabolism.

The WHO recommends measuring serum ferritin concentration. Note: This has limited suitability as a screening parameter for iron deficiency in multimorbid patients.

What is the best screening test for iron metabolism in routine clinical practice? The WHO recommends measuring the serum ferritin level (SF). Ferritin is the only parameter that reflects iron stores and can thereby be used to detect iron deficiency in an early stage. An SF <15 µg/L is held to indicate a deficiency of stored iron. According to the WHO, the upper limit of the normal range for SF is 150 µg/L in women and 200 µg/L in men. The diagnostic utility of ferritin is limited, however, by the fact that it is also an acute phase protein. Inflammatory and neoplastic diseases and diseases of the liver elevate the serum ferritin level, potentially masking a concomitant iron deficiency. The lower limit of normal for SF has, therefore, been defined differently for different patient groups so that it can still serve as a useful screening test for iron deficiency: this lower limit is 100 µg/L in patients with heart failure, and up to 200 µg/L in dialysis patients (18, 19). In one study, patients with iron-deficiency anemia and hematologic or solid neoplasms had SF values above 100 µg/L in 50% of cases, and half of these even had values above 800 µg/L (20). Moreover, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and other advanced liver diseases canbe associated with secondary iron deposition in the liver and an elevated SF. SF is, therefore, not suitable overall as a screening parameter for iron deficiency in multimorbid patients.

Iron-deficient erythropoiesis.

Further evidence of iron-deficient erythropoiesis can be derived from the percentage of hypochromic erythrocytes with an MCH <28 pg (HYPO). In individuals without iron deficiency this is less than 2.5%.

Parameters for monitoring iron supply.

Two especially valuable parameters for monitoring the iron supply to erythropoiesis are soluble transferrin receptors (sTfR) and zinc protoporphyrin.

It is of marginal clinical importance whether the iron stores are full or less than full, as long as they are within the normal range. What the physician wants to know is whether the patient’s anemia, and/or his or her symptoms, are due to iron deficiency. The laboratory parameters that are relevant to this question are those that reflect the iron supply to erythropoiesis and those that indicate iron-deficient erythropoiesis (21). The TSAT is the most commonly recommended parameter for this purpose, with values under 20% reflecting inadequate iron supply. The same threshold value has been incorporated in the clinical guidelines for patients with neoplasia, heart failure, or chronic kidney disease. Further evidence of iron-deficient erythropoiesis can be derived from the percentage of hypochromic erythrocytes with an MCH <28 pg (HYPO), which is determined by modern blood-counting devices. In individuals without iron deficiency this is less than 2.5%; values above 10% are considered proof of a deficiency in erythropoiesis. HYPO is considered the best indicator of iron undersupply in patients with renal anemia who are undergoing treatment with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA). A further very early parameter of iron-deficient erythropoiesis is CHr, which reflects the hemoglobin content of the reticulocytes that are currently being produced. A CHr value below 26 pg is considered abnormal. CHr can also provide early evidence of successful iron supplementation.

ZPP concentration.

The erythrocyte ZPP concentration rises continually from the onset of iron-deficient erythropoiesis, thus enabling the latter to be quantified and its clinical significance to be assessed.

Two especially valuable parameters for monitoring the iron supply to erythropoiesis are soluble transferrin receptors (sTfR) and zinc protoporphyrin (ZPP). The sTfR concentration depends both on the activity of erythropoiesis and on iron status. Elevated sTfR values are seen both in increased erythropoiesis and in iron-deficient erythropoiesis. ZPP is formed when too little iron is supplied to erythropoiesis, by the incorporation of zinc into protoporphyrin IX instead of iron. An elevated ZPP concentration is, therefore, seen not only in iron deficiency in the strict sense, but also in all conditions that involve iron-deficient erythropoiesis. The ZPP concentration rises continually from the onset of iron-deficient erythropoiesis, thus enabling the latter to be quantified and its clinical significance to be assessed (table 2); see also https://www.onkopedia.com/de/onkopedia/guidelines/eisenmangel-und-eisenmangelanaemie/@@guideline/html/index.html (July 2021; not currently available in English). Parallel measurement of ZPP and sTfR is useful for differential diagnosis because, unlike ZPP, the sTfR concentration does not rise in a patient with an iron utilization disorder (22).

Aside from iron deficiency and hemoglobinopathy, a further differential diagnosis in hypochromic–microcytic anemia is the anemia of chronic disease (ACD), also known as anemia of chronic inflammation (ACI). In the specialized literature, ACD is considered to be a common type of anemia, indeed the most common type among hospitalized patients and the elderly (23, 24). In this situation, the deficiency of iron supply to erythropoiesis is not very pronounced, and a normochromic–normocytic pattern is usually found (25). Nonetheless, in severe, protracted courses, inflammatory anemia can also be hypochromic–microcytic. ACD is demonstrated by an increase in stored iron and by decreased sideroblast content in the bone marrow, which reflects an iron utilization disorder. The laboratory tests that are usually obtained cannot reliably differentiate ACD from true iron deficiency. Serum iron and TSAT levels are low in both cases, and the serum ferritin level is too unreliable, especially in multimorbid patients. Where there is simultaneous elevation of CRP, ACD is generally assumed rather than truly proven, and is thus overdiagnosed. As mentioned, the additional measurement of ZPP and sTfR is essential for differential diagnosis, because ZPP is elevated in both cases, but sTfR is almost always normal in ACD. A high sTfR in a patient with ACD indicates that the patient is suffering from true iron deficiency as well. The parallel measurement of sTfR and serum ferritin is also useful, as an elevated TfR-F index (the quotient sTfR/log SF) can indicate iron deficiency even in the presence of inflammation (21).

Iron overload

Oxidative stress

Oxidative stress.

Iron is needed for a multitude of biological processes, but can also have toxic effect because free iron changes easily between its divalent and trivalent forms and thus acts as an electron carrier, catalyzing biochemical reactions such as the Fenton reaction.

As early as the 16th century, Paracelsus realized that “only the dose makes the poison.” Iron is no exception. Iron is needed for a multitude of biological processes, but can also have toxic effect because free iron changes easily between its divalent and trivalent forms and thus acts as an electron carrier, catalyzing biochemical reactions such as the Fenton reaction, in which oxygen radicals are produced. These reactive oxygen species (ROS) damage macromolecules such as proteins, DNA, and lipids, and consequently also organelles such as lysosomes and mitochondria. The damage at the molecular and cellular levels can eventually lead to organ dysfunction. Iron overload thus has a toxic effect in that excess iron is present in an unbound form, causing severe oxidative stress. When, at a TSAT of approximately 60%–70%, the iron binding capacity of transferrin is exceeded, “non-transferrin-bound iron” (NTBI) is formed. One fraction of NTBI is called labile plasma iron (LPI). LPI is both redox-active and chelatable. It can cross the plasma membrane and is taken up particularly readily by various cells, for example by cardiac muscle cells via voltage-gated calcium channels.

Clinical features

Complications of hereditary hemochromatosis and anemia requiring chronic transfusion therapy.

Myocardial iron overload can result in heart failure and arrhythmias, and iron overload in the liver leads in the long term to fibrosis, later to cirrhosis, and even to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma

Diseases such as hereditary hemochromatosis and anemia requiring chronic transfusion therapy, such as the thalassemias, show that the consequences of iron overload can be multifarious (26, 27). Myocardial iron overload can result in heart failure and arrhythmias, and iron overload in the liver leads in the long term to fibrosis, later to cirrhosis, and even to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (28). Endocrine organs are particularly sensitive to iron overload, so diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, or – in young patients with thalassemia major – hypogonadism may develop. Iron overload also promotes bacterial growth and thus infections. It also has vascular effects. Macrophages in the vascular wall can accumulate iron, leading to oxidative stress and reduced cholesterol export, resulting in increased plaque formation (29).

Classification

Both congenital and acquired diseases exist that lead to iron overload. As the Box showing the etiological classification makes clear, the division between congenital and acquired is not identical with the division into primary and secondary hemochromatosis. Positing a further subdivision for secondary siderosis (as iron deposition without tissue damage) seems to us unnecessary, since the point at which tissue damage is detected depends on the sensitivity of the examination techniques. This conceptual distinction is not made in the English-language literature either (with the exception of local hemorrhage-related iron deposition, such as in pulmonary siderosis).

Box. Etiological classification of iron overload disorders.

Congenital causes

-

Various types of hereditary (primary) hemochromatosis (HH)

Disordered hepcidin/ferroportin system

Disordered iron transport

-

Hereditary anemia with ineffective erythropoesis („iron loading anemias“)

Increased intestinal iron absorption

Acquired causes Secondary hemochromatosis

-

Ineffective erythropoesis (myelodysplastic syndrome)

Increased intestinal iron absorption

-

Chronic transfusion therapy

High iron supply from red cell concentrates

Classification.

Both congenital and acquired diseases exist that lead to iron overload. The division between congenital and acquired is not identical with the division into primary and secondary hemochromatosis.

Bei den erblichen Erkrankungen handelt es sich einThe hereditary diseases are made up of, first, various types of hereditary (primary) hemochromatosis (HH), which are caused by either a disorder of the hepcidin/ferroportin system or disordered iron transport (27) (etable) and, second, the “iron-loading anemias,” which are due to ineffective erythropoiesis (30). These last are non-transfusion-dependent thalassemia (NTDT), congenital sideroblastic anemia, and congenital dyserythropoietic anemia.

eTable. Hereditary forms of systemic iron overload*.

| Disorder | Gene and mode of inheritance |

Age group at first diagnosis |

Neurological symptoms | Anemia | Transferrin saturation |

| Disorders in the hepcidin/ferroportin regulatory system | |||||

| HH type I | HFE, AR | Adult | No | No | Raised |

| HH type IIA | HFE2, AR | Child, young adult | No | No | Raised |

| HH type IIB | HAMP, AR | Child, young adult | No | No | Raised |

| HH type III | TFR2, AR | Young adult | No | No | Raised |

| HH type IVA (atypical HH) | FP (LOF), AD | Adult | No | Variable | Initially low |

| HH type IVB | FP (GOF), AD | Adult | No | No | Raised |

| Disorders of iron transport | |||||

| Insufficient iron release: aceruloplasminemia | CP, AR | Adults | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Insufficient iron uptake by erythropoietic cells | |||||

| DMT1 mutations | DMT1, AR | Child | No | Yes | Raised |

| Hypotransferrinemia | TF, AR | Variable | No | Yes | Raised |

| Ineffective erythropoiesis | |||||

| Thalassemia | Globin, AR | Child | No | Yes | Raised |

| Congenital sideroblastic anemia |

ALAS2, XL SCL25A38, AR GLRX5, AR ABCB7, XL |

Variable | No No Yes Yes |

Yes | Raised |

| Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia | |||||

| Type I | DAN1, AR | Child | No | Yes | Raised |

| Type II | SEC23B, AR | Child | No | Yes | Raised |

| Type III | Unknown | Child | No | Yes | Raised |

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; CP, ceruloplasmin; GOF, gain of function; LOF, loss of function;

HH, hereditary hemochromatosis; TF, transferrin; XL, X-linked

*Adapted from (27)

Iron overload disorders with an acquired cause also include those due to ineffective erythropoiesis, especially myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) (31), and also in general all acquired hematopoietic disorders that lead to long-term transfusion dependence—apart from MDS, these include for example primary myelofibrosis and aplastic anemia. With each unit of red cell concentrate, the patient receives at least 200 mg of iron. Since the organism has no physiological mechanism for excreting excess iron, a negative iron balance can only be achieved through the use of chelating agents.

Diagnosis

Serum ferritin

Serum ferritin (SF) generally remains proportional to the iron stored in macrophages, which in turn is a useful measure of total body iron. In patients with hereditary hemochromatosis, however, iron overload affects not the macrophages but the liver cells. SF levels then correlate with the latter, but may underestimate the concentration of iron in the liver (32, 33). As an acute-phase protein, SF is also elevated in inflammation. Extremely elevated levels are found in macrophage activation syndrome in the setting of secondary or primary hemophagocytosis. It is therefore recommended that when evaluating SF levels, inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) should be investigated at the same time. It is also important not to rely on a single SF value but to observe the trend over time (34). In patients with myelodysplastic syndrome with a long-term need for transfusion it was found that, after a median of 21 units of red cell concentrate had been given, median SF reached 1000 µµg/L (35).

Transferrin saturation (TSAT)

Serum ferritin.

Serum ferritin (SF) generally remains proportional to the iron stored in macrophages, which in turn is a useful measure of total body iron.

Measuring TSAT is another simple investigation, and in screening for HH it is even more sensitive than SF. A TSAT above 45% in women or above 50% in men should prompt further genetic testing in this direction (etable). Highly elevated TSAT indicates the presence of iron overload related to NTBI- or LPI-mediated iron toxicity. A disadvantage is that serum iron fluctuates considerably over the course of the day, and the TSAT varies accordingly. Another influence arises from the disordered iron distribution seen with inflammation. In addition, production of transferrin and thus total iron binding capacity may be impaired in patients with liver disease and inflammation. The TSAT should be looked at together with the SF. It should be noted that when SF is elevated, the absence of elevated TSAT does not rule out iron overload, as this abnormal combination may occur in patients with a loss-of-function ferroportin mutation or aceruloplasminemia. During iron chelation therapy, the elevated TSAT is slow to regress and is therefore not a good parameter for follow-up (36).

Other laboratory investigations

Measuring serum hepcidin does not improve the estimation of iron overload because there is a correlation between hepcidin and SF (37). The same is true for measurements of NTBI and LPI, which can serve as surrogate parameters for iron-induced oxidative stress and are very rapidly affected by iron chelators but are not a suitable tool for estimating total body iron.

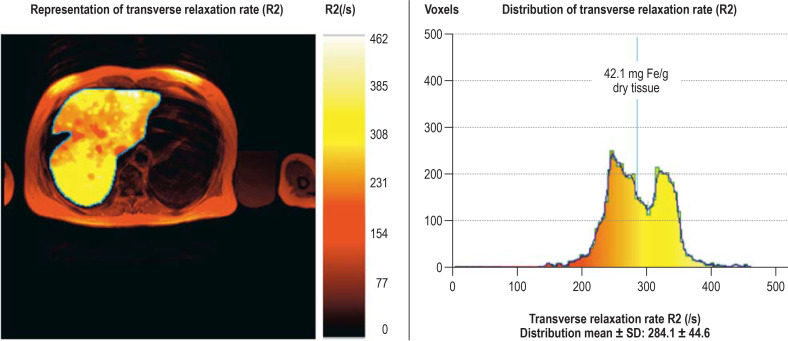

Diagnostic imaging

Measuring cardiac and hepatic iron has an essential role both in assessing impending complications and in guiding iron chelation therapy. Serum ferritin is of limited use in measuring iron overload (38). The iron content of the liver correlates better with total body iron. For noninvasive quantification, an MRI-based method is approved for use in the European Union (39) (figure 3); it is suitable for a broad range of iron-loading disordersand is available at numerous facilities in Germany. Cardiac iron overload is an important special case because it correlates poorly with liver iron levels (40) but has prognostic significance and is important for guiding iron chelation therapy. It usually occurs in patients with thalassemia with a background of many years of transfusion therapy. MRI (T2*-weighted gradient echo sequence) is now the standard technique for measuring cardiac iron (e1). Very low relaxation times of less than 10 ms correlate with the onset of heart failure. These resource-heavy techniques for noninvasive quantification of iron overload are indicated in patients for whom these data affect management decisions, such as guiding iron chelation therapy in patients with long-term transfusion dependence or for risk assessment and treatment decisions in possible candidates for stem cell transplantation.

Figure 3.

Measuring mean liver iron concentration using magnetic resonance imaging

A patient with severe iron overload. As can be seen, the iron is unevenly distributed in the liver, so measuring iron by means of invasive liver biopsy can give unrepresentative findings..

Discussion

Cardiac iron.

MRI (T2*-weighted gradient echo sequence) is now the standard technique for measuring cardiac iron.

When investigating cases of iron deficiency and iron overload, several parameters often need to be looked at simultaneously in order to identify the extent and cause of the problem. Some useful parameters, such as zinc protoporphyrin measurement, are not yet widely available. More detailed understanding of the hepcidin/ferroportin system as the central regulator of iron metabolism in the future will probably enable the treatment of iron metabolism disorders not just by iron substitution or iron chelation, but also by targeted drug manipulation of hepcidin regulation.

Supplementary Material

Case Study

A54-year-old man presented for investigation of long-standing arthralgia of the hands. Clinically, severe swelling of the joints at the base of the index and middle fingers bilaterally was found. Inflammatory markers and serological tests for rheumatoid arthritis were normal. Diagnostically indicative findings were a very high serum ferritin level of 3490 µµg/L and transferrin saturation of 92%. HFE testing was positive and revealed a homozygous C282Y mutation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver was not possible because the patient had a pacemaker. Ultrasonography showed liver fibrosis without portal hypertension. Intensive phlebotomy therapy brought the ferritin level down to within the normal range within 1 year and it remained below 50 µµg/L for the next 12 years. However, the arthropathy progressed, and the patient needed to undergo bilateral total hip replacement and multiple ankle surgeries bilaterally during that period. The further management was complicated by diclofenac-induced renal anemia. However, replacement therapy with erythropoietin allowed phlebotomy therapy to continue for another 3 years; during this time hemoglobin was stable at more than 12 g/dL and serum ferritin around 150 µµg/L. At that point, the patient complained of new-onset severe back pain in the lumbar region. Computed tomography revealed a multifocal, hypervascularized liver tumor with broad-based infiltration of the hepatocaval confluence and right hepatic portal branch, and also “melting” lymph node metastases with infiltration of the L2–3 intervertebral foramen. The tumor, which was inoperable, was strongly suggestive of multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The patient declined further investigation and died of metastatic disease 16 years after the original diagnosis of hereditary hemochromatosis.

This case illustrates, first, that hereditary hemochromatosis as a congenital disorder of iron metabolism may not be diagnosed until the age of 50 years or over. This is particularly common in women, who until the menopause are usually protected from severe iron overload by blood loss through menstruation. Second, it is worth noting that hemochromatosis can become symptomatic initially as arthropathy (e2, e3); this has perhaps been too little known until now. Finally, this case study shows that delayed recognition of hemochromatosis favors the development of HCC because of decades of increased oxidative stress, especially in the liver; in some cases, HCC can develop directly from fibrosis (that is, without passing through a cirrhotic stage) (27).

Figure 1.

Regulation of systemic iron metabolism

The amount of available iron (center and right), inflammatory factors (left), the iron required for erythropoiesis (right), and hormones and growth factors control hepcidin expression. Replete iron stores increase the amount of the cytokine BMP6 (bone morphogenetic protein 6), which together with the coreceptor hemojuvelin (HJV) activates the BMP/SMAD signaling pathway. Hepcidin induces the degradation of ferroportin, thus reducing the release of iron from duodenal enterocytes and macrophages of the reticuloendothelial system. In inflammation-related functional iron deficiency, hepcidin expression is increased via the JAK2-STAT3 signaling pathway. As a consequence of iron deficiency anemia, the kidney produces erythropoietin, which increases erythropoiesis. Erythroid progenitor cells continue to produce erythroferron, which inhibits the BMP/SMAD pathway and hepcidin.

EPO, erythropoietin; ERFE, erythroferron; FPN, ferroportin; HFE, high Fe (iron); IL6, interleukin 6; JAK, Janus kinase; STAT, signal transducers and activators of transcription; SMAD, small-body-size mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 1; TFR2, transferrin receptor 2; TSAT, transferrin saturation.

Further information on cme.

Access to the CME certification program is possible only over the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de. This unit can be accessed until 9 December 2022. Submissions by letter, e-mail, or fax cannot be considered.

Once a new CME module comes online, it remains available for 12 months. Results can be accessed 4 weeks after you start work on a module. Please note the closing date for each module, which can be found at cme.aerzteblatt.de

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN), which is found on the CME card (8027XXXXXXXXXXX). The EFN must be stated during registration on www.aerzteblatt.de (“Mein DÄ”) or else entered in “Meine Daten,” and the participant must agree to communication of the results.

CME credit for this unit can be obtained via cme.aerzteblatt.de until 9 December 2022.

Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the answer that is most appropriate.

Question 1

Which blood hormone increases iron absorption in ß-thalassemia?

Insulin

hemojuvelin

transferrin

erythroferrone

interleukin-6

Question 2

Hepcidin is produced in the liver and circulates in the blood. What is the name of the receptor to which hepcidin binds?

Transferrin receptor

Insulin receptor

TMPRSS6

Iron exporter ferroportin

NMDA receptor

Question 3

What is believed to be the function of hepcidin in the regulation of iron availability?

It increases the absorption of iron from food.

It inhibits iron absorption.

It enhances iron recycling by macrophages.

It increases glucagon expression.

It releases iron from macrophages.

Question 4

What is the most common cause of hypochromic–microcytic anemia?

Vitamin B12 deficiency

Renal anemia

Anemia of chronic disease

Iron deficiency

Folic acid deficiency

Question 5

Transferrin saturation is an important biomarker of iron availability. Which are the saturation levels that show iron deficiency and indicate iron overload?

Iron deficiency: <20%, iron overload: >40%

Iron deficiency: <30%, iron overload: >60%

Iron deficiency: <40%, iron overload: >70%

Iron deficiency: <50%, iron overload: >80%

Iron deficiency: <60%, iron overload: >90%

Question 6

What percentage of children in Europe are affected by iron deficiency?

0.05%–0.5%

0.1%–1%

2%–6%

8%–12%

14%–18%

Question 7

A 72-year-old patient with myelodysplastic syndrome becomes permanently dependent on transfusion due to progressive anemia. After the administration of how many units of packed red cells (PRC) can serum ferritin be expected to rise to approximately 1000 µµg/L?

About 5

about 10

about 20

about 40

about 60

Question 8

Which laboratory parameters should be measured when investigating iron deficiency?

Fasting blood sugar and glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase (aspartate aminotransferase)

Total LDL and C-reactive protein

HbA1c and creatinine

Alkaline phosphatase and urea

Ferritin and zinc protoporphyrin

Question 9

In older patients, the consequences of iron overload may be heavily overlaid by age-related medical problems. Which of the following diseases can be a result of systemic iron overload?

Ulcerative colitis

heart failure

glaucoma

Dupuytren‘s disease

morbid obesity

Question 10

What can mask iron deficiency?

High thyroid values

Immunosuppressive drugs

Pregnancy

Inflammatory disease

LDL cholesterol level > 180 mg/dL

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, MD, and Kersti Wagstaff

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Muckenthaler MU, Rivella S, Hentze MW, Galy B. A red carpet for iron metabolism. Cell. 2017;168:344–361. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muckenthaler M, Petrides PE. Heinrich PC, Müller M, Graeve L, Koch HG, editors. Spurenelemente. Biochemie und Pathobiochemie Heidelberg: Springer Verlag. 2021:1042–1069. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corradini E, Buzzetti E, Pietrangelo A. Genetic iron overload disorders. Mol Aspects Med. 2020;75 doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2020.100896. 100896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rivella S. Iron metabolism under conditions of ineffective erythropoiesis in beta-thalassemia. Blood. 2019;133:51–58. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-07-815928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srole DN, Ganz T. Erythroferrone structure, function, and physiology: Iron homeostasis and beyond. J Cell Physiol. 2021;236:4888–4901. doi: 10.1002/jcp.30247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arezes J, Foy N, McHugh K, et al. Erythroferrone inhibits the induction of hepcidin by BMP6. Blood. 2018;132:1473–1477. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-06-857995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heeney MM, Finberg KE. Iron-refractory iron deficiency anemia (IRIDA) Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2014;28:637–652. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO. Anaemia in children. <5 years www.apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.ANEMIACHILDRENREGv?lang=en. (2017) (last accessed on 18 November 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. Prevalence of anemia in woman. www.apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.ANEMIAWOMAN?lang=en . (2017) (last accessed on 18 November 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmermann MB. Global look at nutritional and functional iron deficiency in infancy. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2020;2020:471–477. doi: 10.1182/hematology.2020000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statista. Anzahl der Vegetarier und Veganer in Deutschland. www.de.statista.com./infografik/24000/anzahl-der-vegetarier-und-veganer-in-deutschland/ (last accessed on 18 November 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunz J, Kulozik A. Hoffmann GF, Lentze MJ, Spranger J, Zepp F, Berner R, editors. Anämien Pädiatrie. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag. 2020:2117–2146. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen B, Bourque J, Moore TM, et al. Longitudinal development of brain iron is linked to cognition in youth. J Neurosci. 2020;40:1810–1818. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2434-19.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Haehling S, Ebner N, Evertz R, Ponikowski P, Anker SD. Iron deficiency in heart failure: an overview. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ponikowski P, Kirwan BA, Anker SD, et al. Ferric carboxymaltose for iron deficiency at discharge after acute heart failure: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396:1895–1904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kassebaum NJ, Jasrasaria R, Naghavi M, et al. A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood. 2014;123:615–624. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-508325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, Wojdyla D, de Benoist B. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System, 1993-2005. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:444–454. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chopra VK, Anker SD. Anaemia, iron deficiency and heart failure in 2020: facts and numbers. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7:2007–2011. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Numan S, Kaluza K. Systematic review of guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency anemia using intravenous iron across multiple indications. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36:1769–1782. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2020.1824898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludwig H, Evstatiev R, Kornek G, et al. Iron metabolism and iron supplementation in cancer patients. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2015;127:907–919. doi: 10.1007/s00508-015-0842-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas C, Thomas L. Biochemical markers and hematologic indices in the diagnosis of functional iron deficiency. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1066–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Camaschella C. New insights into iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia. Blood Rev. 2017;31:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fraenkel PG. Anemia of inflammation: a review. Med Clin North Am. 2017;101:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guralnik JM, Eisenstaedt RS, Ferrucci L, Klein HG, Woodman RC. Prevalence of anemia in persons 65 years and older in the United States: evidence for a high rate of unexplained anemia. Blood. 2004;104:2263–2268. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss G, Ganz T, Goodnough LT. Anemia of inflammation. Blood. 2019;133:40–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-06-856500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borgna-Pignatti C, Cappellini MD, De Stefano P, et al. Survival and complications in thalassemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1054:40–47. doi: 10.1196/annals.1345.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleming RE, Ponka P. Iron overload in human disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:348–359. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1004967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niederau C, Fischer R, Sonnenberg A, Stremmel W, Trampisch HJ, Strohmeyer G. Survival and causes of death in cirrhotic and in noncirrhotic patients with primary hemochromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:1256–1262. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198511143132004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vinchi F, Porto G, Simmelbauer A, et al. Atherosclerosis is aggravated by iron overload and ameliorated by dietary and pharmacological iron restriction. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2681–2695. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camaschella C, Nai A. Ineffective erythropoiesis and regulation of iron status in iron loading anaemias. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:512–523. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gattermann N. Iron overload in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) Int J Hematol. 2018;107:55–63. doi: 10.1007/s12185-017-2367-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Origa R, Galanello R, Ganz T, et al. Liver iron concentrations and urinary hepcidin in beta-thalassemia. Haematologica. 2007;92:583–588. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taher A, El Rassi F, Isma‘eel H, Koussa S, Inati A, Cappellini MD. Correlation of liver iron concentration determined by R2 magnetic resonance imaging with serum ferritin in patients with thalassemia intermedia. Haematologica. 2008;93:1584–1586. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Telfer PT, Prestcott E, Holden S, Walker M, Hoffbrand AV, Wonke B. Hepatic iron concentration combined with long-term monitoring of serum ferritin to predict complications of iron overload in thalassaemia major. Br J Haematol. 2000;110:971–977. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malcovati L, Porta MG, Pascutto C, et al. Prognostic factors and life expectancy in myelodysplastic syndromes classified according to WHO criteria: a basis for clinical decision making. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7594–7603. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.7038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porter JB, El-Alfy M, Viprakasit V, et al. Utility of labile plasma iron and transferrin saturation in addition to serum ferritin as iron overload markers in different underlying anemias before and after deferasirox treatment. Eur J Haematol. 2016;96:19–26. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Camaschella C, Nai A, Silvestri L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Haematologica. 2020;105:260–272. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.232124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Virgiliis S, Sanna G, Cornacchia G, et al. Serum ferritin, liver iron stores, and liver histology in children with thalassaemia. Arch Dis Child. 1980;55:43–45. doi: 10.1136/adc.55.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.St Pierre TG, Clark PR, Chua-anusorn W, et al. Noninvasive measurement and imaging of liver iron concentrations using proton magnetic resonance. Blood. 2005;105:855–861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen AR, Galanello R, Pennell DJ, Cunningham MJ, Vichinsky E. Thalassemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2004:14–34. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2004.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Anderson LJ, Holden S, Davis B, et al. Cardiovascular T2-star (T2*) magnetic resonance for the early diagnosis of myocardial iron overload. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:2171–2179. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Braner A. [Haemochromatosis and Arthropathies] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2018;143:1167–1173. doi: 10.1055/a-0505-9244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Carroll GJ, Breidahl WH, Olynyk JK. Characteristics of the arthropathy described in hereditary hemochromatosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:9–14. doi: 10.1002/acr.20501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Case Study

A54-year-old man presented for investigation of long-standing arthralgia of the hands. Clinically, severe swelling of the joints at the base of the index and middle fingers bilaterally was found. Inflammatory markers and serological tests for rheumatoid arthritis were normal. Diagnostically indicative findings were a very high serum ferritin level of 3490 µµg/L and transferrin saturation of 92%. HFE testing was positive and revealed a homozygous C282Y mutation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the liver was not possible because the patient had a pacemaker. Ultrasonography showed liver fibrosis without portal hypertension. Intensive phlebotomy therapy brought the ferritin level down to within the normal range within 1 year and it remained below 50 µµg/L for the next 12 years. However, the arthropathy progressed, and the patient needed to undergo bilateral total hip replacement and multiple ankle surgeries bilaterally during that period. The further management was complicated by diclofenac-induced renal anemia. However, replacement therapy with erythropoietin allowed phlebotomy therapy to continue for another 3 years; during this time hemoglobin was stable at more than 12 g/dL and serum ferritin around 150 µµg/L. At that point, the patient complained of new-onset severe back pain in the lumbar region. Computed tomography revealed a multifocal, hypervascularized liver tumor with broad-based infiltration of the hepatocaval confluence and right hepatic portal branch, and also “melting” lymph node metastases with infiltration of the L2–3 intervertebral foramen. The tumor, which was inoperable, was strongly suggestive of multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The patient declined further investigation and died of metastatic disease 16 years after the original diagnosis of hereditary hemochromatosis.

This case illustrates, first, that hereditary hemochromatosis as a congenital disorder of iron metabolism may not be diagnosed until the age of 50 years or over. This is particularly common in women, who until the menopause are usually protected from severe iron overload by blood loss through menstruation. Second, it is worth noting that hemochromatosis can become symptomatic initially as arthropathy (e2, e3); this has perhaps been too little known until now. Finally, this case study shows that delayed recognition of hemochromatosis favors the development of HCC because of decades of increased oxidative stress, especially in the liver; in some cases, HCC can develop directly from fibrosis (that is, without passing through a cirrhotic stage) (27).