Abstract

Background:

Numerous factors influence patient recruitment to, and retention on, peritoneal dialysis (PD), but a major challenge is a perceived “inaccessibility” to treating clinicians. It has been suggested that remote patient monitoring (RPM) could be a means of improving such oversight and, thereby, uptake of PD.

Objective:

To describe patient and clinician perspectives toward RPM and the use of applications (Apps) suitable for mobiles, tablets, or computers to support the provision of PD care.

Design:

Qualitative design using semi-structured interviews.

Setting:

All patient participants perform PD treatment at home under the oversight of an urban PD unit in Sydney, Australia. Patient and clinician interviews were conducted within the PD unit.

Participants:

14 participants (5 clinicians [2 nephrologists, 3 PD nurses] and 9 patients treated with PD).

Methods:

Semi-structured interviews were conducted using interview guides tailored for clinician and patient participants. Transcripts were coded and analyzed by a single researcher using thematic analysis.

Results:

Six themes were identified: perceived benefits of RPM implementation (offering convenience and efficiency, patient assurance through increased surveillance, more complete data and monitoring adherence), uncertainty regarding data governance (protection of personal data, data reliability), reduced patient engagement (transfer of responsibility leading to complacency), changing patient-clinician relationships (reduced patient-initiated communication, the need to maintain patient independence), increased patient and clinician burden (inadequate technological literacy, overmanagement leading to frequent treatment changes), and clinician preference influencing patient behavior.

Limitations:

The interviews were conducted in English only and with participants from a single urban dialysis unit, which may limit generalizability.

Conclusions:

For patients and clinicians, advantages from the use of RPM in PD may include increased patient confidence and assurance, improved treatment oversight, more complete data capture, and overcoming barriers to data documentation. Careful patient selection and patient and clinician education may help to optimize the benefits of RPM, maintain patient independence, and reduce the risks of patient disengagement. The use of an App may support RPM; however, participants expressed concerns about increasing the burden on some patients through the use of unfamiliar technology.

Human Research Ethics Committee Approval Number:

CH62/6/2019-028

Keywords: mobile application, peritoneal dialysis, patient perspective, qualitative research, remote patient monitoring, patient-centered care

Abrégé

Contexte:

De nombreux facteurs influent sur le recrutement et la rétention des patients en dialyse péritonéale (DP); un des principaux défis étant une impression d’« inaccessibilité » aux cliniciens traitants. La télésurveillance des patients (TSP) a été suggérée comme possible moyen d’améliorer le suivi et, par conséquent, l’adhésion des patients à la DP.

Objectif:

Décrire les points de vue des patients et des cliniciens à l’égard de la TSP et de l’utilisation d’applications adaptées aux téléphones intelligents, aux tablettes ou aux ordinateurs pour aider à la prise en charge de la DP.

Type d’étude:

Étude qualitative menée par le biais d’entretiens semi-structurés.

Cadre:

Tous les patients suivant des traitements de DP à domicile sous la supervision de l’unité de DP d’un centre urbain de Sydney (Australie). Les entretiens avec les patients et les cliniciens ont été menés au sein de l’unité de DP.

Participants à l’étude:

14 participants, soit 5 cliniciens (2 néphrologues, 3 infirmières et infirmiers en DP) et 9 patients sous DP.

Méthodologie:

Des entretiens semi-structurés ont été menés à l’aide de guides d’entrevue adaptés aux cliniciens et aux patients participants. Les transcriptions ont été codées, puis une analyse thématique par un seul chercheur a été réalisée.

Résultats:

Six thèmes ont été dégagés : 1) avantages perçus de la TSP (intervention pratique et efficace, patients rassurés par une surveillance accrue, données plus complètes et meilleur suivi de l’observance); 2) incertitude quant à la gouvernance des données (protection des données personnelles, fiabilité des données); 3) réduction de la participation des patients (transfert de responsabilité menant à la complaisance); 4) évolution de la relation patient-clinicien (réduction des échanges initiés par le patient, nécessité de maintenir l’indépendance du patient); 5) fardeau accru pour le patient et le clinicien (connaissances technologiques inadéquates, gestion excessive conduisant à de fréquents changements du traitement) et; 6) comportement du patient influencé par la préférence du clinicien.

Limites:

Les entretiens ont été menés uniquement en anglais, auprès de participants provenant d’une seule unité de dialyse en centre urbain, ce qui pourrait limiter la généralisabilité des résultats.

Conclusion:

Selon les patients et les cliniciens interrogés, la TSP en contexte de DP pourrait offrir plusieurs avantages : confiance et assurance accrues pour les patients, meilleure surveillance du traitement, saisie plus complète des données et suppression des entraves liées à la documentation des données. Une sélection rigoureuse des patients et une formation adéquate du patient et du clinicien pourraient contribuer à optimiser les avantages de la TSP, à maintenir l’indépendance du patient et à réduire les risques de désengagement. L’utilisation d’une application pourrait appuyer la TSP; des participants ont cependant exprimé des inquiétudes quant à une augmentation du fardeau pour certains patients moins familiers avec ce type de technologie.

Numéro d’approbation du Comité d’éthique pour la recherche sur l’être humain :

CH62/6/2019 — 028

Introduction

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) offers comparable patient survival to hemodialysis 1 with the convenience of a home-based, flexible treatment schedule and the ability to travel. Although these attributes are ranked among the highest priorities of dialysis by patients and caregivers, 2 only a small minority of all patients receiving dialysis in Australia (18%) 3 and globally (10%) 4 are treated with PD. Numerous factors influence patient recruitment to, and retention on, PD, 4 but a major challenge is a perceived “inaccessibility” to treating clinicians and it has been suggested that remote patient monitoring (RPM) could be a means of improving such oversight and, thereby, uptake of PD. 5

Remote patient monitoring is a framework for monitoring patients at home through digital technology, which extends clinical oversight and contact from the conventional clinical setting to the home. 5 Within PD, real-time monitoring of a patient’s PD treatment data may allow better insight into their clinical condition, earlier identification of dialysis-related complications, and adherence to treatment. 5 While previous studies have shown the feasibility of RPM for patients treated with PD in North America, 6 and reported both patient 7 and clinician 8 enthusiasm for remote monitoring in PD care in New Zealand, a paucity of data regarding RPM in PD still exists. 5 Remote monitoring in PD has advanced with the evolution of automated peritoneal dialysis (APD) machines that enable bidirectional communication, with the latest models providing direct transfer of clinical data from the APD cycler to the hospital care team, enabling doctors and nurses to verify and change the dialysis prescription remotely. 9 However, not all PD patients treated with APD in Australia have access to these newer APD machines and around 30% of those treated with PD are treated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) without the use of a cycler. 3 If RPM is going to contribute to the increased uptake of PD in Australia, and globally, then developing alternative methods of RPM that do not rely on the use of the most advanced APD cyclers will be important. Use of the Internet, mobile phones, and applications (Apps) suitable for mobiles, tablets, or computers may provide one such approach, 10 and understanding the expectations of patients and clinicians regarding the implementation of such approaches will be critical to their development.

Evidence of patient or clinician perspectives toward RPM use in PD care, and in particular the use of Apps to facilitate RPM, remains limited. The aims of this study were to describe patient and clinician perspectives and expectations toward RPM and the use of Apps to support the provision of PD care.

Method

This study is reported according to the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ). 11 The research team, which included 2 patient partners with lived experience of kidney disease identified through a consumer engagement process, reviewed the study design, interview guides, and patient-facing material and contributed to analysis of de-identified synthesized results and manuscript preparation. Semi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face by B.T. (a male nephrology advanced trainee [MBBS] and PhD candidate who had completed training in qualitative data collection, analysis, and reporting). The interviewer was known to clinician participants through work within the local health district but only to one patient participant. The participants were informed that the interviewer was a nephrology advanced trainee and that the study was part of the Affordable Dialysis Project, with the purpose of understanding more about the experiences of patients treated with PD and how data recording could be improved. The interviewer was aware of the model of RPM but had not had direct experience of its use.

Participant Recruitment

Participants were patients and clinicians selected from a single urban PD training unit serving 2 large teaching hospitals in Sydney, Australia. Eligible patients included any English-speaking adult treated with PD for longer than 3 months. Patient participants were identified by clinical staff within the PD unit who had been trained in the study aims and processes. These staff reviewed patient lists and approached potential participants to discuss the study. All patients were considered for suitability and eligibility. Patient participants were purposively selected to include those currently using a form of RPM and those who were able to describe their PD treatment and data monitoring practices. Physicians and nurses with experience delivering PD treatment were identified by the Heads of Renal Departments at each teaching hospital for inclusion as clinician participants. The study received institutional research approval (Ref: CH62/6/2019-028).

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted face-to-face within the PD unit. Patient participants could be accompanied by a partner or carer if they wished and all participants completed written informed consent. The interview guides were developed following review of the literature and discussion among the research team to include topics that were not covered in the published literature. Separate guides were tailored to clinicians and patients and included questions about PD delivery, training and support, participant experiences of data management, and attitudes regarding the use of an App to document and transfer treatment data to the treating nephrologist or PD nurses (Supplementary File S1). Remote patient monitoring was considered any method of PD treatment data recording that allowed daily monitoring of a patient’s clinical condition by the treating nephrologist or PD nurses. All interviews lasted less than 60 minutes and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Field notes were taken and included reference to nonverbal communication, ideas that were considered important by the interviewer during or directly after the interview and on occasion points raised by participants after the recording had stopped. To minimize participant inconvenience, repeat interviews were not conducted and transcripts were not returned to participants for comment.

Data Analysis

Data were thematically analyzed 12 by B.T., who coded the transcripts line-by-line. B.T. aimed to remain open to new ideas during analysis and assigned codes as closely as possible to how they appeared in the data. Interviews and analyses were conducted in 2 stages, with the second stage following an update to the interview guides based on initial analysis to include questions around changing behavior patterns resulting from RPM. During analysis, codes were inductively identified and grouped with similar codes and then developed into concepts specific to patient and clinician perceptions of RPM. Transcripts were analyzed using NVivo 12 for Windows. 13 A second author (S.F.) independently double-coded 2 transcripts, including patient and clinician transcripts. No new codes were identified in the final interview, indicating data saturation was achieved. The preliminary findings were reviewed by each member of the research team, including our patient partners, to ensure the full breadth and range of data had been captured.

Results

Participant Information

Interviews were completed with 9 patients (2 of whom were accompanied by their partner/carer) and 5 clinicians. Another 7 patients were approached for interviews but declined, citing either limited time or that they did not wish to be interviewed. All clinicians who were approached took part. The participant demographics are presented in Table 1. All patients had used CAPD previously and were using an APD system during the study, and all lived within 20 km of the dialysis unit. At the time of interview, 2 patients were using RPM; one used an APD machine with bidirectional communication and one documented their treatment data into a spreadsheet and e-mailed it daily to the PD unit. All other patients recorded their treatment data using a method of their choice but did not routinely report their data to the PD unit after each treatment. This was considered “standard” data monitoring practice, and in these circumstances, treatment data were only reported to the PD unit during routine home, telephone, or clinic consultations, or if a patient was concerned by their data and chose to contact the PD unit. All clinicians were familiar with RPM as a model of monitoring, although less than 5% of patients treated at the PD unit used a form of regular RPM at the time of data collection.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics (n = 14).

| Patient characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Current type of PD | ||

| APD | 9 | 100 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 30-49 | 1 | 11 |

| 50-69 | 4 | 44 |

| 70-89 | 4 | 44 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 6 | 67 |

| Female | 3 | 33 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 5 | 56 |

| Asian | 1 | 11 |

| European | 2 | 22 |

| Pacific Islands | 1 | 11 |

| Time treated with PD (years) | ||

| <1 | 3 | 33 |

| 1-5 | 4 | 44 |

| >5 | 2 | 22 |

| Current use of RPM | ||

| Yes | 2 | 22 |

| No | 7 | 78 |

| Clinician characteristics | n | (%) |

| Role | ||

| Physician | 2 | 40 |

| PD nurse | 3 | 60 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 3 | 60 |

| Female | 2 | 40 |

| Years of experience with PD | ||

| <5 | 0 | 0 |

| 5-10 | 3 | 60 |

| >10 | 2 | 40 |

Note. PD = peritoneal dialysis; APD = automated peritoneal dialysis; RPM = remote patient monitoring.

Analysis

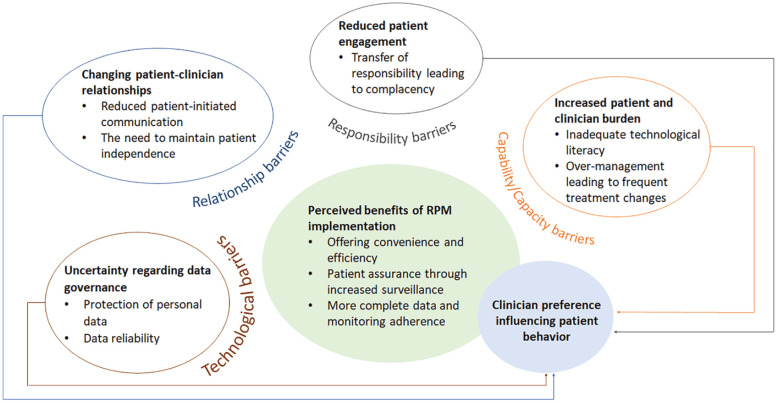

We identified 6 themes: perceived benefits of RPM implementation, uncertainty regarding data governance, reduced patient engagement, changing patient-clinician relationships, increased patient and clinician burden, and clinician preference influencing patient behavior. The themes and subthemes are outlined below and presented in a thematic schema depicting the conceptual links between themes (Figure 1). Illustrative quotations are provided in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Thematic schema.

Note. Patient and clinician perspectives toward RPM were broadly conceptualized either as improved patient and clinician experiences resulting from successful RPM or as potential barriers to RPM, including risks to patients’ data governance, patient-clinician relationships, shifts in responsibility or of increased burden to patients and clinicians. Each of these had the potential to modify clinician preference, which in turn was reported to influence patient behaviors. RPM = remote patient monitoring.

Table 2.

Selected Participant Quotations for Each Theme.

| Theme | Illustrative quotation |

|---|---|

| Perceived benefits of RPM implementation | |

| Offering convenience and efficiency | “I think the logbook’s a pain in the arse. It’s just so difficult . . . you’ve got to pick it up. You’ve got to write it in and then you’ve got to ring back the—you’ve got to send the figures in. It’s not as if you write them in the book and forget about them . . . I find it very easy to have a spreadsheet, put them [treatment data] into the spreadsheet and email my spreadsheet.” (Patient, 70 years old, <1 year PD experience, using RPM) |

| Patient assurance through increased surveillance | “Patients might feel they’re more connected [with RPM], they have a bit more support if required . . . it might provide another layer of support that patients may appreciate.” (Clinician, 5-10 years PD experience) |

| More complete data and monitoring adherence | “It [RPM] is a lot better. I mean because sometimes I wouldn’t write it down, you know. Sometimes I would just do it [PD treatment] and just continue doing what I had to do, and sometimes I just don’t write it at all.” (Patient, 35 years old, <1 year PD experience, using RPM) |

| Uncertainty regarding data governance | |

| Protection of personal data | “I’m always concerned about what’s happening to all this information that, shall we say, the Government is collecting on all the citizens and what they’re doing with it.” (Patient, 76 years old, >5 years PD experience, not using RPM) |

| “People are always worried about data security and privacy. So, lots of people have died because of data security, privacy and their data not getting places it should be.” (Clinician, >10 years PD experience) | |

| Data reliability | “Once you start putting data out there it’s potentially steal-able, hackable, something could go wrong, it could get corrupted, we could be seeing the wrong patient’s data.” (Clinician, 5-10 years PD experience) |

| Reduced patient engagement | |

| Transfer of responsibility leading to complacency | “It would take away more of the responsibility of the patient and give it more to the staff because when we see something then we need to do something.” (Clinician, 5-10 years PD experience) |

| “The other thing is that there may be some false perceptions from the patients that, ‘Oh, I’m being monitored, I don’t need to see them, I don’t need to do my routine visits, they know exactly what’s going on so I don’t really need to come in and have my face to face time,’ that may be another concern.” (Clinician, 5-10 years PD experience) | |

| Changing patient-clinician relationships | |

| Reduced patient-initiated communication | “If it comes automatic, yeah, I don’t even have to ring them up . . . If they go down [data automatically transferred], they’ll see them . . . And if they find something funny, they ring me, perhaps, and ask questions.” (Patient, 81 years old, >5 years PD experience, not using RPM) |

| “They must know everything that happens all the time without me even having to say anything . . . and I won’t have to ring them all the time to tell them what happened. They actually know just by looking at their computer.” (Patient, 35 years old, <1 year PD experience, using RPM) | |

| The need to maintain patient independence | “Everybody just wants ease of access to the people they need when they need them and then they want to be left alone at the other times . . . And being more and more obtrusive, doesn’t necessarily mean you’re doing them anymore favors.” (Clinician, >10 years PD experience) |

| Increased patient and clinician burden | |

| Inadequate technological literacy | “the population we’re dealing with, are not social media ravens you know, I don’t know how many of them have got smartphones.” (Clinician, >10 years PD experience) |

| Overmanagement leading to frequent treatment changes | “I find that if we see things daily, we tend to change more things, and not obsess, but I guess home in on it, where it might sort itself out. So sometimes it is best to just leave the regime as it is.” (Clinician, 5-10 years PD experience) |

| Clinician preference influencing patient behavior | |

| “I don’t like email . . . I always tell my patients not to email me, ring me . . . I can’t tell emotions through email, because I’m good with contact.” (Clinician, 5-10 years PD experience) | |

| “When I was on the bags [CAPD], I would use an app for it [data recording] which is a lot less trouble . . . The phone’s there and it’s just easy to do it. But I just—when I went to the machine [APD], they gave me the book and they wanted me to bring it in every so often, so it’s just easier to write it in the book . . . I would do it [use an App] if they preferred me to do it that way.” (Patient, 57 years old, 1-5 years PD experience, not using RPM) | |

Note. RPM = remote patient monitoring; PD = peritoneal dialysis; CAPD = continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; APD = automated peritoneal dialysis; App = mobile telephone application.

Perceived Benefits of RPM Implementation

Offering Convenience and Efficiency

Patients using RPM regarded it as more convenient and efficient than standard methods of data monitoring and felt RPM could be expanded to reduce the frequency of home visits. One patient, currently using RPM, described previously needing to write down treatment data and then telephone the PD unit to report it as cumbersome, time-consuming, and prone to error.

Patient Assurance Through Increased Surveillance

Most patients and clinicians described expecting RPM and real-time review of patients’ treatment data to provide additional reassurance and encouragement to patients, allowing them to feel more connected to their medical team while at home. Clinicians described being less certain as to whether RPM would influence modality of kidney replacement therapy (KRT) selection for patients or directly impact on service provision as maintaining “face-to-face hours” was acknowledged as important. Some patients using standard data monitoring did not see a benefit in increased surveillance through RPM as they described feeling sufficiently supported through their current data monitoring practices.

More Complete Data and Monitoring Adherence

Improved oversight of treatment resulting from RPM was felt to be an advantage by patients and clinicians, which could help overcome common barriers to documenting data, including attrition due to the monotony of repetitive daily tasks, difficulties with language, low levels of literacy or visual impairment, and patients underappreciating the utility of treatment data. Clinicians viewed the improved oversight as particularly beneficial for patients where treatment adherence is of concern:

We are identifying patients who really need it [RPM], so patients who we never hear from. We want to know whether they are doing the dialysis or not. (Clinician, 5-10 years PD experience)

Uncertainty Regarding Data Governance

Protection of Personal Data

Clinicians in particular described concerns regarding data protection and the need to ensure security of personal information. One patient also described concerns regarding data security; however, most patients did not consider personal data protection an important risk and would be happy for their data to be transmitted to their supervising team in real time. One patient did not regard data surrounding their dialysis treatments as private:

I don’t worry about privacy or anything like that. It is not like it is sending off . . . something that is, like, that private. (Patient, 35 years old, <1 year PD experience, using RPM)

Data Reliability

The importance of data reliability was emphasized by patients and clinicians. One clinician raised concerns over the risk of RPM data being corrupted or linked to an incorrect patient, whereas patients using RPM considered it to be more reliable than standard methods of data monitoring.

Reduced Patient Engagement

Transfer of Responsibility Leading to Complacency

A concern raised by clinicians was the potential for perceived shifts in responsibility (from patients to PD nurses) to develop in patients using RPM because a nurse is reviewing their treatment data daily. The current standard of care is that PD patients are responsible for documenting their treatment data each day and contacting the PD unit if they have concerns. Some clinicians were concerned that RPM could lead to changes in patient behavior, such as reduced patient engagement, and some patients reported being less likely to contact their clinicians if RPM were in place, even if abnormal treatment data were seen. Individual attitudes differed however, as other patients reported that they would still contact the PD unit regarding any abnormal treatment data. Some clinicians also expressed concerns that information could be overlooked with daily transfer of treatment data.

Changing Patient-Clinician Relationships

Reduced Patient-Initiated Communication

Both participant groups described the potential for changes in the way patients interact with clinicians resulting from RPM. Some patients not currently using RPM reported being less likely to contact their clinicians if RPM were in place and one patient currently using RPM reported that since transitioning to RPM they believed there was no longer any need to initiate contact with the PD nurses. Despite this belief, the same patient reported increased communication with PD nurses since commencing RPM as a result of the nurses contacting them more frequently in response to the RPM data received.

The Need to Maintain Patient Independence

Clinicians were concerned that an increase in clinician-initiated communication and intervention, which could result from RPM, may be intrusive and burdensome to some patients, particularly those who work. Encouraging patients’ autonomy and independence around their treatment was recognized by clinicians as an important priority.

Increased Patient and Clinician Burden

Inadequate Technological Literacy

Patient and clinician participants raised concerns regarding the need for patients to use new unfamiliar technology, particularly when discussing the use of an App for RPM. The need for simplicity was identified by both groups of participants. Clinicians were particularly concerned about increasing the burden on patients and prioritized features that could simplify data recording. Some patients reported being open to learning new approaches to data monitoring and some participants were aware of the use of Apps for other chronic conditions. Some patients described the use of Apps for data monitoring as convenient and intuitive, and others were less inclined to try:

I don’t like those gadgets. I never use them . . . Stop all those gadgets. (Patient, 81 years old, >5 years PD experience, not using RPM)

Overmanagement Leading to Frequent Treatment Changes

Clinicians raised concerns regarding the potential for overmanagement resulting from PD nurses viewing patients’ treatment data daily, which could lead to unnecessary prescription changes and increased workload for patients and clinicians. The concern regarding overmanagement was reported despite the use of predefined clinical criteria “flags” designed to help stratify the significance of changes in clinical parameters observed.

Clinician Preference Influencing Patient Behavior

Patients and clinicians described how the preference of clinicians can strongly influence patients’ data monitoring practices:

The bulk of them [patients], [use] the paper because that’s what we teach them . . . We’re driven by paper here in terms of that sort of data collection. That’s the easiest way to teach them. (Clinician, >5 years PD experience)

One patient reported that despite preferring to use an App for data monitoring they had switched to using the paper logbook as it seemed easier because it was preferred by the clinicians.

Discussion

Patients and clinicians in our study described numerous potential benefits of RPM, including increased patient confidence and assurance, improved treatment oversight, more complete data capture, and overcoming barriers to data documentation such as difficulties with language, literacy, or sight. Similar perspectives have been described by patients 7 and clinicians 8 in New Zealand, with our study suggesting that these perspectives on using RPM are also considered important by the participants who took part in this study.

Patients in our study with experience of RPM described increased convenience and efficiency resulting from RPM use, which they considered to be more reliable than standard treatment monitoring. Interestingly, clinician views differed to those of patients, with PD nurses expressing concerns that more intensive monitoring could lead to unnecessary treatment changes and a risk of overmanagement. These views differed to those of PD nurses in New Zealand who reported enjoying efficiency benefits with RPM. 8 One explanation for this difference could be that the benefits reported in New Zealand were most notable when treating rural patients and our study was conducted within an urban PD unit with patients living relatively close to the medical service. These differences in clinician perspectives highlight important opportunities for education, training, and appropriate patient selection to fully optimize time and cost saving when implementing RPM.

Clinicians in our study also described concerns that RPM use could lead to reduced patient engagement and a perceived transfer of responsibility to the PD nurses. The view that patients’ recording their own PD data is important in helping to maintain patient engagement has been described previously by patients and clinicians in the United States and United Kingdom. 14 While such concerns were not described by clinicians in New Zealand, 8 adequate education prior to RPM implementation and clear communication regarding the limitations of RPM and the boundaries of responsibility for patients and clinicians were reported as important strategies to help mitigate such risks. 8 Jeopardizing interpersonal connections between patients and clinicians has previously been reported as a concern of patients with chronic diseases regarding RPM use 15 and both participant groups in our study described the risk of reduced patient-initiated communication following the introduction of RPM. Consistent with previous reports of patient7,15 and clinician 8 views that RPM should not replace interpersonal care, clinicians in our study emphasized the need for RPM to be used as an adjunct to routine PD care while maintaining “face-to-face hours” between clinicians and their patients. Ensuring interactive 2-way communication is part of any RPM implementation was also suggested by clinicians as one way to help maintain patient-clinician relationships.

When considering the potential use of an App for data monitoring, clinicians and patients in our study expressed concerns regarding the use of new unfamiliar technology for patients and the desire to avoid increases in patient burden from their treatment. While the benefits of a comprehensive PD App, including features such as appointment reminders, medication lists, and capabilities to order stock and track blood results, were described, participants reported prioritizing features that could simplify data collection for patients. Patients and clinicians in our study described the influence that clinician preferences can have on patient practices, which highlights the importance of clinician support if RPM implementation is to be successful.

Our study has identified several themes that could present potential barriers to successful RPM implementation (Figure 1). As a result, we suggest some technological and training priorities to be considered when designing and introducing an RPM program, including simple, accurate, and reliable data recording and storage and early education regarding the benefits and limitations of RPM and the need for its use to be as an adjunct to routine care (Table 3).

Table 3.

Priorities for RPM Implementation.

| Suggested priority | Advantages |

|---|---|

| Technological | |

| Simple, user-friendly interface not dependent on levels of literacy or language | • Overcome barriers which can prevent data documentation |

| Accurate and reliable data recording and transfer | • Provide patients and clinicians with confidence using RPM |

| Robust and secure storage of data | • Protection of personal data is viewed as important by patients and clinicians |

| Patients should be able to access their own data easily and in variable formats | • Encourage patient autonomy and engagement with

treatment • Variable data layouts appeal to some patients and may avoid the monotony of repetitive data entry |

| Real-time data transfer and interactive bidirectional communication between patients and clinicians | • Increase patient confidence through real-time connection to

their nephrology team • Allow time-saving by avoiding multiple phone calls and possibly reducing the frequency of home visits • Provide an opportunity to strengthen patient-clinician relationships |

| Patient education | |

| Define the limitations of RPM and the responsibilities of patients and clinicians | • Encourage patient autonomy and continued engagement with their

treatment • Avoid transfer of responsibility to PD nurses and prevent patient complacency |

| Highlight the importance of continued communication between patients and clinicians alongside RPM | • Prevent breakdown of established patient-clinician

relationships • Allow continued feedback of information from patients to clinicians not recorded by RPM |

| Clinician education | |

| Highlight potential benefits and pitfalls of RPM use | • Increase clinician understanding and preference for

RPM • Support the optimal use of RPM |

| Encourage integration of RPM as an adjunct to routine PD care | • Maintaining face-to-face hours is prioritized by patients and

clinicians • Opportunity to enhance patient-clinician relationships • Encourage ongoing holistic management approach and avoid neglect of nondialytic areas of patient care |

| Help establish clearly defined clinical criteria and clinician roles for responding to RPM data | • Avoid overmanagement of patients • Maintain continuity of care • Encourage and protect patient independence • Provide a framework to safely monitor patients |

Note. RPM = remote patient monitoring; PD = peritoneal dialysis.

This study has a number of strengths; we included nephrologists, nurses, and patients to gather a range of perspectives regarding the use of RPM in PD, including patients with and without prior experience of RPM, to better understand patient concerns and potential barriers to implementing an RPM program. To our knowledge, this is the first study of patient or clinician perspectives of RPM in PD to be conducted in Australia and the first study to seek clinician and patient perspectives toward the potential use of an App for RPM in PD. Our study also has some limitations. Analyses were conducted by a single coder and the study was conducted in a single urban dialysis unit in Australia and therefore the generalizability of the findings to other cities, rural settings, or other countries may be limited and the interviewer was known to many of the clinician participants, which may have influenced their responses. All interviews were conducted in English and with purposefully selected participants. While a broad range of participants were sought, this excluded non-English-speaking patients and possibly others such as those with cognitive impairment. Understanding the perspectives of such patients, to whom RPM may be particularly beneficial, will be important moving forward. It should also be acknowledged that whilst all clinicians in our study were familiar with the model of RPM, less than 5% of patients treated at the PD unit were using a form of regular RPM at the time of data collection. Although the impact of age on attitudes toward RPM was not the focus of this study, it is possible that age may influence perspectives toward RPM and therefore that our results in an older cohort (median age 69 years) may not be reflective of the entire PD population. Additional factors such as participants’ educational level, occupational history, or familiarity with devices in the home or workplace, which were not specifically correlated with participant views in our study, could also be explored further. Finally, we interviewed participants already treated with PD, understanding the perspectives of patients who may be reluctant to commence PD will also be important to understand whether RPM could be used to improve the uptake of PD treatment in the future.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that patients and clinicians from an urban PD unit in Australia perceived numerous advantages to the use of RPM in PD, but clinicians suggested that RPM should be used as an adjunct to routine clinical care rather than replacing existing communication and support processes. Appropriate patient selection and careful education is likely to optimize the benefits of RPM and reduce the risks of patient disengagement and misunderstandings around the nature of clinician oversight. While the use of an App may support RPM, particularly for patients treated with CAPD, our study suggests that patients and clinicians share concerns over increasing patient burden through the use of unfamiliar technology and that simplicity should be prioritized. A paucity of data regarding patient perspectives from different regions, including developing healthcare systems, still exists regarding RPM and the use of Apps to support PD and offers an important opportunity for future research.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cjk-10.1177_20543581221084499 for Patient and Clinician Perspectives on the use of Remote Patient Monitoring in Peritoneal Dialysis by Benjamin Talbot, Sara Farnbach, Allison Tong, Steve Chadban, Shaundeep Sen, Vincent Garvey, Martin Gallagher and John Knight in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants for sharing their interesting and thoughtful perspectives in this study. We would also like to thank our 2 patient partners, who reviewed the study design, interview guides, and patient-facing material and contributed to analysis of de-identified synthesized results and manuscript preparation but wish to remain anonymous. B.T. is supported by a Scientia scholarship from the University of New South Wales.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: This study received institutional research approval from Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (CH62/6/2019-028)

Consent for Publication: All authors have provided consent for publication of this manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author and subject to approval from Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee.

Authors’ Note: The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract form.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Ellen Medical Devices who are developing the Affordable Dialysis Project. B.T., V.G., and J.K. are employed by Ellen Medical Devices.

ORCID iDs: Benjamin Talbot  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7029-7813

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7029-7813

Martin Gallagher  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9187-6187

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9187-6187

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Davies SJ. Peritoneal dialysis—current status and future challenges. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9(7):399-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morton RL, Tong A, Webster AC, Snelling P, Howard K. Characteristics of dialysis important to patients and family caregivers: a mixed methods approach. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(12):4038-4046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. ANZDATA Registry. 42nd Report, Chapter 2: Prevalence of Renal Replacement Therapy for End Stage Kidney Disease. Adelaide, Australia: Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li PK, Chow KM, Van de Luijtgaarden MW, et al. Changes in the worldwide epidemiology of peritoneal dialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(2):90-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wallace EL, Rosner MH, Alscher MD, et al. Remote patient management for home dialysis patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2(6):1009-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lew SQ, Sikka N, Thompson C, Cherian T, Magnus M. Adoption of telehealth: remote biometric monitoring among peritoneal dialysis patients in the United States. Perit Dial Int. 2017;37(5):576-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Walker RC, Tong A, Howard K, Darby N, Palmer SC. Patients’ and caregivers’ expectations and experiences of remote monitoring for peritoneal dialysis: a qualitative interview study. Perit Dial Int. 2020;40(6):540-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Walker RC, Tong A, Howard K, Palmer SC. Clinicians’ experiences with remote patient monitoring in peritoneal dialysis: a semi-structured interview study. Perit Dial Int. 2020;40(2):202-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giuliani A, Crepaldi C, Milan Manani S, et al. Evolution of automated peritoneal dialysis machines. Contrib Nephrol. 2019;197:9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nayak A, Karopadi A, Antony S, Sreepada S, Nayak KS. Use of a peritoneal dialysis remote monitoring system in India. Perit Dial Int. 2012;32(2):200-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101. [Google Scholar]

- 13. QSR International (1999) NVivo 12 Qualitative Data Analysis Software. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Subramanian L, Kirk R, Cuttitta T, et al. Remote management for peritoneal dialysis: a qualitative study of patient, care partner, and clinician perceptions and priorities in the United States and the United Kingdom. Kidney Med. 2019;1(6):354-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walker RC, Tong A, Howard K, Palmer SC. Patient expectations and experiences of remote monitoring for chronic diseases: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Med Inform. 2019;124:78-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-cjk-10.1177_20543581221084499 for Patient and Clinician Perspectives on the use of Remote Patient Monitoring in Peritoneal Dialysis by Benjamin Talbot, Sara Farnbach, Allison Tong, Steve Chadban, Shaundeep Sen, Vincent Garvey, Martin Gallagher and John Knight in Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease