ABSTRACT

There is a growing concern that ongoing evolution of SARS-CoV-2 could lead to variants of concern (VOC) that are capable of avoiding some or all of the multifaceted immune response generated by both prior infection or vaccination, with the recently described B.1.1.529 (Omicron) VOC being of particular interest. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell samples from PCR-confirmed, recovered COVID-19 convalescent individuals (n = 30) infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the United States collected in April and May 2020 who possessed at least one or more of six different HLA haplotypes were selected for examination of their anti-SARS-CoV-2 CD8+ T-cell responses using a multiplexed peptide-major histocompatibility complex tetramer staining approach. This analysis examined if the previously identified viral epitopes targeted by CD8+ T cells in these individuals (n = 52 distinct epitopes) are mutated in the newly described Omicron VOC (n = 50 mutations). Within this population, only one low-prevalence epitope from the Spike protein, restricted to two HLA alleles and found in 2/30 (7%) individuals, contained a single amino acid change associated with the Omicron VOC. These data suggest that virtually all individuals with existing anti-SARS-CoV-2 CD8+ T-cell responses should recognize the Omicron VOC and that SARS-CoV-2 has not evolved extensive T-cell escape mutations at this time.

KEYWORDS: convalescent patients, Omicron, CD8+ T cell, COVID-19, convalescent plasma, SARS-CoV-2

OBSERVATION

As the global COVID-19 pandemic has continued, there is growing concern that ongoing evolution of SARS-CoV-2 could lead to a variant of the virus that is capable of avoiding the multifaceted immune response generated by both prior infection or vaccination (1–3). Several of these variants of concern (VOC) have been identified throughout the pandemic and have been associated with large-scale waves of infection. To date, while several VOC have exhibited various levels of antibody resistance in vitro, vaccination, as well as previous infection by SARS-CoV-2, have been shown to maintain a significant level of protection against breakthrough or reinfections, especially in terms of preventing serious disease and mortality (4, 5). However, the B.1.1.529/Omicron variant contains a greater number of mutations than previous VOC (6). If the mutations in the Omicron VOC mediated resistance from any part of the anti-SARC-CoV-2 immune response, either from vaccination or infection, it could have consequences for efforts to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. The variant also has now been identified on every continent except Antarctica, suggesting it has significant transmission potential, similar to other VOC.

The majority of the mutations associated with the Omicron VOC are located in the Spike protein of the virus, presumably due to selection for evasion of antibody responses, and could have significant effects on the ability of preexisting antibodies to neutralize the virus, although to what extent this is the case has yet to be determined. It is also unknown how these mutations affect nonneutralizing binding antibody responses. While it is critical to determine the extent to which Omicron may or may not be susceptible to existing humoral responses, T-cell-associated immunity is, in general, significantly more difficult for viruses to overcome due to the broad and adaptable response generated in a given individual as well as the variety of HLA haplotypes between individuals.

A previous analysis by our group of CD8+ T-cell responses to the original SARS-CoV-2 variant in convalescent individuals found a broad and varied immune response in virtually all patients examined, even in individuals with relatively low anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses (1). A subsequent analysis of these data found that mutations associated with the Alpha, Beta, and Gamma VOC had very minimal cross-over with the epitopes identified in this earlier study (1/52 epitopes affected), suggesting that the CD8+ T-cell response from earlier infection most likely would be effective against the new variants (7). In this study, the mutations associated with Omicron VOC are examined in an identical manner.

RESULTS

The individuals examined in this study were primarily male (60%), and the blood samples were collected a median of 42.5 days (interquartile range, 37.5 to 48.0) from initial diagnosis (1). The patients were selected from the larger study population according to sample availability, and anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG responses with 10 individuals were selected from each of three antibody tertiles (1, 3). A total of 132 SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T-cell responses were identified in these individuals, which corresponded to 52 unique epitopes found across the viral genome targeting both structural and nonstructural proteins.

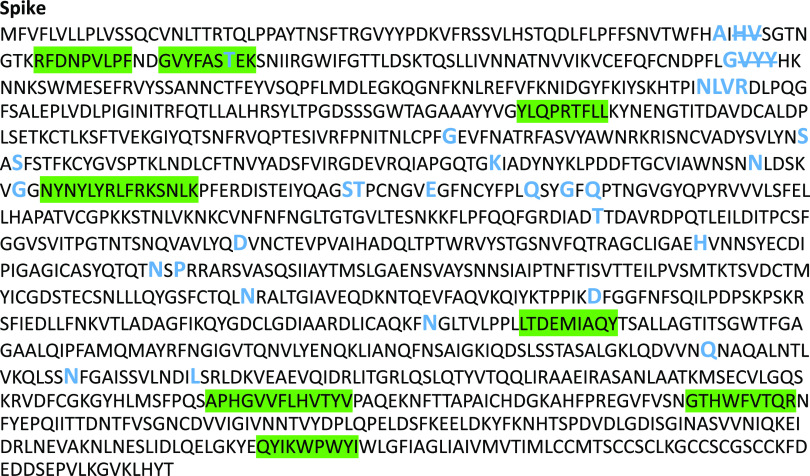

Of the mutations associated with the Omicron variant (n = 50), only one in the Spike protein (T95I) overlapped a CD8+ T-cell epitope (GVYFASTEK) identified in this population (Fig. 1; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This epitope is restricted to HLA-A*03:01 and HLA-A*11:01, and T-cell reactivity was detected in two individuals, typed as HLA-A*03:01 and HLA-A*03:01/HLA-A*11:01, respectively (Tables S1 and S2) (8). Despite the possibility of inducing T-cell responses against GVYFASTEK, presented on both alleles in one individual, this epitope represented a low-prevalence target in both of these individuals, making up 0.1% and a combined 0.3% of all CD8+ T-cell responses in each individual (Table S3) (1). In addition, this epitope was 1 of 5 and 1 of 8 of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 epitopes targeted by the two individuals, respectively (Table S3).

FIG 1.

SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan variant protein amino acid sequence for Spike protein with CD8+ T-cell epitopes highlighted (green), and all mutation and deletion (slash) sites are indicated in large blue letters.

SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan variant protein amino acid sequence with CD8+ T cell epitopes highlighted in green, and all mutation and deletion (slash) sites are indicated in large blue letters (nonoverlapping). Download FIG S1, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (20.7KB, docx) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Study population detection of HLA-A03 and -A11. Download Table S1, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (16.9KB, docx) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Demographics of subjects with a T-cell response against the original spike epitope, mutated in Omicron. Download Table S2, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (16.2KB, docx) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

T-cell reactivity against HLA-A*03:01- and HLA-A*11:01-restricted epitopes in two subjects with T-cell responses against the original spike epitope that was found mutated in Omicron HLA. Download Table S3, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (18.3KB, docx) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

For both HLA-A*03:01- and HLA-A*11:01-restricted epitopes, amino acids V in position two and L in position nine act as strong anchor residues. In addition, position seven, which is the location of the T95I mutation, can also contribute to HLA binding and, in fact, may be a preferred residue for this location (9, 10). Therefore, it is possible that the T95I mutation actually improves epitope binding. However, while binding to major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) may not be detrimentally affected, it is unknown how the mutation would affect the ability of T-cell receptors selected against the original peptide to recognize the mutated peptide in the MHC.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that despite the substantial number of mutations in the Omicron VOC, only one low-prevalence CD8+ T-cell epitope from the Spike protein contained a single amino acid change. No other mutations were associated with previously identified epitopes. These data suggest that virtually all individuals with existing anti-SARS-CoV-2 CD8+ T-cell responses should recognize the Omicron VOC and that SARS-CoV-2 has not evolved extensive T-cell escape mutations at this point.

There are several limitations in this study. The results are based on a relatively small sample size of individuals who were all from the United States. Additionally, we examined the CD8+ T-cell responses in previously infected but not vaccinated individuals, and it is possible that the T-cell responses in the latter group are more limited and therefore more susceptible to escape. However, work examining T-cell responses from vaccinees has demonstrated a strong CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell response in these individuals, suggesting that similar trends should be seen in this population as well (2, 11).

While it is unknown what specific immune response, or more likely, combination of responses, provides optimum protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease, it almost certainly includes a broad and robust CD8+ T-cell response. These data build on the previous analysis of the initial VOC and confirm that while SARS-CoV-2 has demonstrated a continued pattern of ongoing evolution, this has not resulted in any meaningful accumulation of CD8+ T-cell escape mutations (7). These data also suggest that existing CD8+ T-cell responses from a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, and most likely from vaccination, will still recognize the Omicron VOC and should provide a significant level of protection against COVID-19.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The detailed methods of the earlier two studies were published previously (1, 7). In short, peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples from PCR-confirmed, recovered COVID-19 convalescent plasma donors collected in April and May 2020 in the Baltimore, MD, and Washington, DC, region who possessed at least one or more of six different HLA haplotypes (HLA-A*01:01, HLA-A*02:01, HLA-A*03:01, HLA-A*11:01, HLA-A*24:02, and HLA-B*07:02) were selected for examination of their anti-SARS-CoV-2 CD8+ T-cell responses using a multiplexed peptide-MHC tetramer staining approach. The peptides used to evaluate the SARS-CoV-2–specific CD8+ T cells and the specific T-cell antigen specificities are available in the previously published supplemental methods (1).

The mutations associated with Omicron VOC (PL, K38R, delta1265, L1266I, A1892T; Nsp4, T492I; 3CL, P132H; Nsp6, delta105-107, I189V; RdRp, P323L; Nsp14, I42V; Spike, A67V, delta69-70, T95I, G142D, delta143-145, N211I; L212V_RE, V213P, R214E, G339D, S371L, S373P, K417N, N440K, G446S, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, G496S, Q498R, T547K, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, N856K, Q954H, N969K, L981F; envelope, T9I; matrix, D3G, Q19E, A63T; nucleocapsid, P13L, delta31-33, R203K, G204R) were mapped to the epitope map developed in the previous analyses and examined for possible crossover (12).

Ethics.

All study participants provided written informed consent, and this study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the convalescent plasma study and laboratory teams, and all the convalescent plasma donors, for their generous participation in the study.

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) R01AI120938, R01AI120938S1, and R01AI128779 (A.A.R.T.); the Division of Intramural Research, NIAID, NIH (O.L., A.D.R., and T.C.Q.); and National Heart Lung and Blood Institute 1K23HL151826-01 (E.M.B.).

H.K., B.A., A.N., and M.F. are shareholders and/or employees of ImmunoScape, Pte Ltd. A.N. is a board director of ImmunoScape, Pte Ltd.

Contributor Information

Andrew D. Redd, Email: aredd2@jhmi.edu.

Aaron A. R. Tobian, Email: atobian1@jhmi.edu.

Stephen P. Goff, Columbia University/HHMI

REFERENCES

- 1.Kared H, Redd AD, Bloch EM, et al. 2021. SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in convalescent COVID-19 individuals. J Clin Invest 131:e145476. doi: 10.1172/JCI145476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woldemeskel BA, Garliss CC, Blankson JN. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines induce broad CD4+ T-cell responses that recognize SARS-CoV-2 variants and HCoV-NL63. J Clin Invest 131:e149335. doi: 10.1172/JCI149335DS1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein SL, Pekosz A, Park H-S, Ursin RL, Shapiro JR, Benner SE, Littlefield K, Kumar S, Naik HM, Betenbaugh MJ, Shrestha R, Wu AA, Hughes RM, Burgess I, Caturegli P, Laeyendecker O, Quinn TC, Sullivan D, Shoham S, Redd AD, Bloch EM, Casadevall A, Tobian AA. 2020. Sex, age, and hospitalization drive antibody responses in a COVID-19 convalescent plasma donor population. J Clin Invest 130:6141–6150. doi: 10.1172/JCI142004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopez Bernal J, Andrews N, Gower C, Gallagher E, Simmons R, Thelwall S, Stowe J, Tessier E, Groves N, Dabrera G, Myers R, Campbell CNJ, Amirthalingam G, Edmunds M, Zambon M, Brown KE, Hopkins S, Chand M, Ramsay M. 2021. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant. N Engl J Med 385:585–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang P, Hasan MR, Chemaitelly H, Yassine HM, Benslimane FM, Al Khatib HA, AlMukdad S, Coyle P, Ayoub HH, Al Kanaani Z, Al Kuwari E, Jeremijenko A, Kaleeckal AH, Latif AN, Shaik RM, Abdul Rahim HF, Nasrallah GK, Al Kuwari MG, Al Romaihi HE, Butt AA, Al-Thani MH, Al Khal A, Bertollini R, Abu-Raddad LJ. 2021. BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant in Qatar. Nat Med 27:2136–2143. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01583-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. 2021. Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern. https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern.

- 7.Redd AD, Nardin A, Kared H, et al. 2021. CD8+ T-cell responses in COVID-19 convalescent individuals target conserved epitopes from multiple prominent SARS-CoV-2 circulating variants. Open Forum Infect Dis 8:7. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grifoni A, Weiskopf D, Ramirez SI, Mateus J, Dan JM, Moderbacher CR, Rawlings SA, Sutherland A, Premkumar L, Jadi RS, Marrama D, de Silva AM, Frazier A, Carlin AF, Greenbaum JA, Peters B, Krammer F, Smith DM, Crotty S, Sette A. 2020. Targets of T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell 181:1489–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elamin NE, Bade-Doeding C, Blasczyk R, Eiz-Vesper B. 2010. Polymorphism between HLA-A*0301 and A*0302 located outside the pocket F alters the PΩ peptide motif. Tissue Antigens 76:487–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2010.01547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eichmann M, de Ru A, van Veelen PA, Peakman M, Kronenberg-Versteeg D. 2014. Identification and characterisation of peptide binding motifs of six autoimmune disease-associated human leukocyte antigen-class I molecules including HLA-B*39:06. Tissue Antigens 84:378–388. doi: 10.1111/tan.12413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oberhardt V, Luxenburger H, Kemming J, et al. 2021. Rapid and stable mobilization of CD8+ T-cells by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. Nature 597:268–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03841-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.GISAID. 2021. GISAID. Accessed 1 December 2021. https://www.gisaid.org/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan variant protein amino acid sequence with CD8+ T cell epitopes highlighted in green, and all mutation and deletion (slash) sites are indicated in large blue letters (nonoverlapping). Download FIG S1, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (20.7KB, docx) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Study population detection of HLA-A03 and -A11. Download Table S1, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (16.9KB, docx) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

Demographics of subjects with a T-cell response against the original spike epitope, mutated in Omicron. Download Table S2, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (16.2KB, docx) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.

T-cell reactivity against HLA-A*03:01- and HLA-A*11:01-restricted epitopes in two subjects with T-cell responses against the original spike epitope that was found mutated in Omicron HLA. Download Table S3, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (18.3KB, docx) .

This is a work of the U.S. Government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. Foreign copyrights may apply.