Abstract

In individuals with substance use disorders, stress is a critical determinant of relapse susceptibility. In some cases, stressors directly trigger cocaine use. In others, stressors interact with other stimuli to promote drug seeking, thereby setting the stage for relapse. Here we review the mechanisms and neurocircuity that mediate stress-triggered and -potentiated cocaine seeking. Stressors trigger cocaine seeking by activating noradrenergic projections originating in the lateral tegmentum that innervate the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis to produce beta adrenergic receptor-dependent regulation of neurons that release corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) into the ventral tegmental area (VTA). CRF promotes the activation of VTA dopamine neurons that innervate the prelimbic prefrontal cortex resulting in D1 receptor-dependent excitation of a pathway to the nucleus accumbens core that mediates cocaine seeking. The stage-setting effects of stress require glucocorticoids, which exert rapid non-canonical effects at several sites within the mesocorticolimbic system. In the nucleus accumbens, corticosterone attenuates dopamine clearance via the organic cation transporter 3 to promote dopamine signaling. In the prelimbic cortex, corticosterone mobilizes the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), which produces CB1 receptor-dependent reductions in inhibitory transmission, thereby increasing excitability of neurons which comprise output pathways responsible for cocaine seeking. Factors that influence the role of stress in cocaine seeking, including prior history of drug use, biological sex, chronic stress/co-morbid stress-related disorders, adolescence, social variables, and genetics are discussed. Better understanding when and how stress contributes to drug seeking should guide the development of more effective interventions, particularly for those whose drug use is stress related.

Keywords: cocaine, stress, reinstatement, seeking, relapse, craving

1. Introduction

Substance use disorders (SUDs) continue to rank among society’s most significant public health challenges, and there is a pressing need for more effective interventions. SUDs are cyclical with bouts of drug taking interrupted by periods of abstinence during which mounting drug craving and exposure to various triggers often lead to relapse to drug use. Indeed, high relapse rates represent the biggest barrier to the effective management of SUDs. Therapeutic approaches aimed at relapse prevention have limited efficacy, and improved interventions await a better understanding of the factors that contribute to drug craving and relapse as well as the underlying neurochemistry. This review will focus on the neurobiological mechanisms and neural circuits that mediate the influence of stress on drug-seeking behavior. We will primarily summarize work from our laboratory and others, with a focus on cocaine seeking. However, many of the neural circuits and mechanisms through which stress regulates cocaine seeking appear to generalize to other drugs of abuse.

There is a strong link between stress and cocaine use disorder. The rate of co-morbidity between cocaine use disorder and stress-related conditions (Kosten and Kleber, 1988), most notably for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Back et al., 2000), is high; among individuals with PTSD, nearly half (46.4%) also meet criteria for an SUD (Mccauley et al. 2012). Further, measures of cumulative lifetime stress positively correlate with the severity of cocaine addiction (Mahoney et al., 2013). Life stress often precedes cocaine use (Wallace, 1989; Preston and Epstein, 2011) and, in some cases, can predict relapse (Waldrop et al., 2007). Moreover, in general, relapse susceptibility is greater in those with SUDs who have lower distress tolerance (Banducci et al., 2016). In a laboratory setting, personalized stress imagery can precipitate cocaine craving (Sinha et al., 1999; Sinha et al., 2000) and the magnitude of craving and associated physiological responses can predict subsequent relapse likelihood (Sinha et al., 2006; Back et al., 2010). However, the relationship between stress and cocaine seeking is complex. While stress often precedes cocaine craving, it does not reliably predict situational craving or craving magnitude (Preston and Epstein, 2011; Furnari et al., 2015) and in many cases appears to function cooperatively with other stimuli that promote craving, such as drug-associated cues (Preston et al., 2018). In some cases, stress is not sufficient to directly trigger cocaine craving (De La Garza et al., 2009) and instead appears to promote, or potentiate, cue-elicited craving (Duncan et al., 2007; Preston et al., 2018), thereby “setting the stage” for drug seeking in response to other triggers.

This review will first describe the neurochemical mechanisms and neural circuits that mediate stress-triggered cocaine seeking. Next, we will summarize the neurobiological mechanisms that underlie the stage-setting effects of stress on cocaine use. Last, we will review factors that can influence the contribution of stress to cocaine seeking, including neuroadaptations that are dependent on the amount and pattern of prior cocaine use, chronic stress and co-morbid stress-related disorders, sex differences, adolescence, social factors, and genetics.

2. Stressor-triggered cocaine seeking

In some cases, episodic stress can trigger drug seeking. Anecdotal reports that stressful life events can precipitate relapse to cocaine use are corroborated by laboratory studies demonstrating that personalized scripts recounting past stressful events can induce craving in those with cocaine use disorder (Sinha et al., 1999; Sinha et al., 2000). Indeed, the magnitude of stress-induced craving in abstinent users in an inpatient setting predicts subsequent relapse to cocaine use (Sinha et al., 2006; Back et al., 2010). In rodents, stress-triggered drug seeking can be studied by assessing the ability of stressors to reinstate extinguished lever pressing or nose poking following self-administration or their ability to re-establish place preference following cocaine conditioning and extinction in mice (see Mantsch et al., 2016 for review). A variety of stressors have been demonstrated to reinstate cocaine seeking following self-administration or conditioned place preference (CPP) (summarized in Table 1). Notably, while there is considerable overlap in the mechanisms that have been implicated in stressor-induced cocaine seeking between the two approaches, differences in the learning processes/constructs involved, species used, contingency of drug delivery, and patterns/amounts of drug exposure must be considered when interpreting results. In our laboratory we study stress-triggered cocaine seeking using intermittent electric footshock following long-access cocaine self-administration and extinction in rats, as well as forced swim following cocaine CPP and extinction in mice.

Table 1:

Stressors that trigger reinstate cocaine seeking following self-administration and extinction in rats and conditioned place preference (CPP) in mice.

| Stressors shown to reinstate cocaine seeking after self-administration | |

|---|---|

| Shock | Erb, Shaham, and Stewart (1996) |

| Food restriction | Shalev, Marinelli, Baumann, Piazza, and Shaham (2003) |

| Forced swim | Conrad et al. (2010) |

| Yohimbine | Feltenstein et al. (2011) |

| Social defeat-predicting cues | Manvich, Stowe, Godfrey, and Weinshenker (2016) |

| Stressors shown to reinstate place preference after CPP | |

| Intermittent footshock | Lu et al. (2002) |

| Social defeat | Calpe-López et al. (2021) |

| Restraint | Sanchez et al. (2003) |

| Forced swim | Kreibich and Blendy (2004) |

| Conditioned fear-predictive cues | Sanchez and Sorg (2001) |

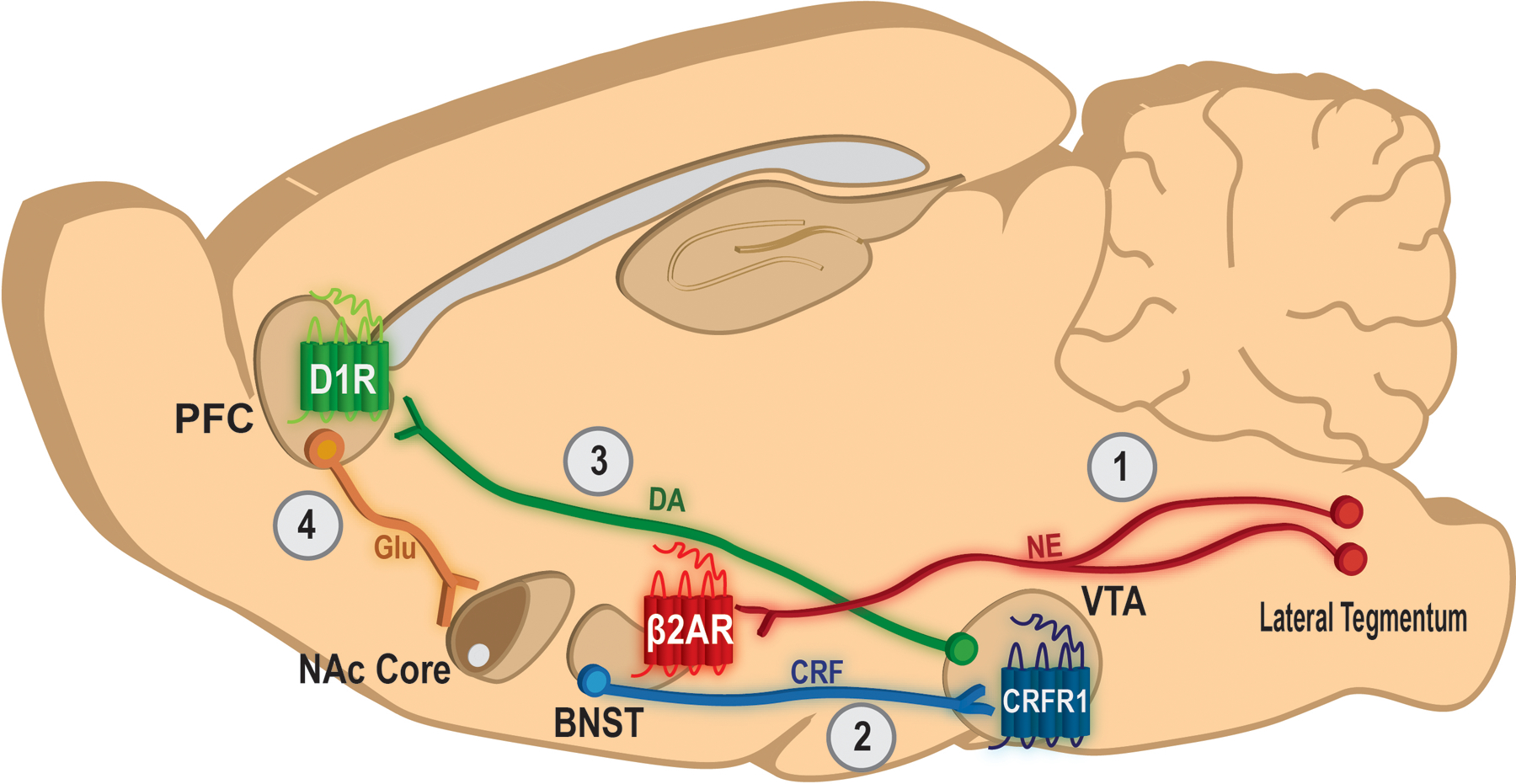

Numerous neural circuits and neurobiological mechanisms appear to contribute to stress-triggered drug use. Much of the work conducted by our laboratory using pre-clinical rodent approaches has focused on how stressor-induced noradrenergic signaling in the extended amygdala and its influence on mesocorticolimbic function via regulation of the ventral tegmental area contributes to stress-triggered cocaine seeking (Figure 1). Here we will review these findings.

Figure 1: Neurocircuitry and mechanisms that contribute to stress-triggered cocaine seeking.

1) Ascending noradrenergic projections from neurons that comprise the A1 and A2 cell groups in the lateral tegmentum release norepinephrine (NE) into regions within the extended amygdala, including the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST). In the BNST, NE activates beta-2 adrenergic receptors (β2AR) which, via a CRF-dependent mechanism (not depicted), promote stimulation of a pathway that co-releases CRF into the ventral tegmental area (VTA). 2) In the VTA, CRF binds to CRF-R1 receptors to promote the activation of dopaminergic neurons that project to the prelimbic region of the prefrontal cortex (PFC). 3) Dopamine released into the prelimbic PFC activates D1 dopamine receptors (D1R) to increase the excitability of pyramidal neuron outputs. 4) Activation of pyramidal neurons that innervate the nucleus accumbens (NAc) core releases glutamate (Glu) to stimulate medium spiny neuron projections to the ventral pallidum that mediate drug seeking.

Noradrenergic Signaling

Stressors evoke widespread noradrenergic signaling in the brain through activation of multiple cell groups in the pons, medulla, and midbrain. While projections from the locus coeruleus (LC) have been found to contribute to drug seeking (Shinohara et al., 2019), much research has focused on projections from the A1 and A2 lateral tegmental medullary cell groups via the ventral noradrenergic bundle to brain regions that comprise the extended amygdala. It has been reported that 6-OHDA lesions of these cell groups attenuates shock-induced drug seeking while pharmacological inhibition of noradrenergic neurons in the LC has no effect (Shaham et al., 2000). Noradrenergic signaling has been implicated in stressor-triggered cocaine seeking. Central norepinephrine (NE) delivery via intracerebroventricular (icv) infusion reinstates extinguished cocaine seeking following self-administration (Brown et al., 2011). Likewise, alpha-2 adrenergic receptor antagonist drugs such as yohimbine, which promote norepinephrine release by antagonizing presynaptic autoreceptors, reinstate extinguished cocaine seeking following self-administration in rats (Feltenstein and See, 2006) and CPP in mice (Mantsch et al., 2010), while alpha-2 receptor agonists, which can suppress norepinephrine release, prevent stressor-induced cocaine seeking (Erb et al., 2000; Mantsch et al., 2010). However, there are some caveats to these findings. First, alpha-2 adrenergic receptors are not exclusively presynaptic autoreceptors in the brain. In the prefrontal cortex (PFC), a region implicated in cocaine seeking, alpha-2A receptors are localized to dendrites on pyramidal neurons where they can regulate PFC outputs (Wang et al., 2007), while in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) some alpha-2 receptors are excitatory Gi-coupled heteroreceptors that can influence drug seeking (Perez et al., 2020). Moreover, yohimbine can promote cue-directed behaviors independently of operant history (Chen et al., 2015). The involvement of noradrenergic signaling in stress-triggered reinstatement is also supported by the observation that the dopamine-beta-hydroxylase inhibitor, nepicastat, which prevents conversion of dopamine to norepinephrine, attenuates yohimbine-induced reinstatement following cocaine self-administration (Schroeder et al.,2013).

Stressor-triggered cocaine seeking is also blocked by adrenergic receptor antagonists. We have used the CPP/reinstatement approach in mice to determine the specific receptors through which stressors reinstate CPP. Forced swim-induced reinstatement is blocked by the non-selective beta-adrenergic receptor antagonist, propranolol (Mantsch et al., 2010), and is not observed in beta-adrenergic receptor knockout mice (Vranjkovic et al., 2012), while the beta-adrenergic receptor agonist, isoproterenol, reproduces the effects of swim stress (Vranjkovic et al., 2012). Stressor-triggered reinstatement appears to involve beta-2, but not beta-1 adrenergic receptors, as forced swim-induced reinstatement of CPP is prevented by the beta-2 receptor antagonist, ICI-118,551, but not the beta-1 receptor antagonist, betaxolol, and is replicated by the beta-2 adrenergic receptor agonist, clenbuterol (Vranjkovic et al., 2012). Although the alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, prazosin, has been reported to contribute to cocaine-primed reinstatement following self-administration in rats (Zhang et al., 2005; Schmidt et al., 2017) we have found that prazosin does not block reinstatement of CPP in mice in response to either forced swim or yohimbine (Mantsch et al., 2010).

Noradrenergic Regulation of the BNST

The primary sites of adrenergic receptor mediation of stress-triggered drug seeking are likely within the extended amygdala, including the central amygdala (CeA), nucleus accumbens (NAc) shell, and the BNST. Each of these regions shows increased Fos reactivity following stressor- (Briand et al., 2010) or norepinephrine- (Brown et al., 2011) triggered cocaine seeking (and pharmacological inactivation of each regions prevents swim-induced cocaine seeking following CPP in mice and/or shock-induced reinstatement following self-administration in rats (McFarland et al., 2004). The CeA and BNST receive dense noradrenergic innervation (Fritschy and Grzanna, 1991; Aston-Jones et al, 1999) and bilateral micro-infusions of a beta-1/beta-2 adrenergic receptor antagonist cocktail into either region attenuates shock-induced reinstatement following self-administration in rats (Leri et al., 2002). Our work has focused on the contribution of beta-adrenergic receptors in the BNST to stressor-induced cocaine seeking. We found that, similar to the effects of systemically administered antagonists on swim-induced reinstatement of CPP in mice, shock-induced reinstatement following self-administration in rats is blocked by intra-BNST administration of the beta-2 receptor antagonist, ICI-118,551, but not the beta-1 receptor antagonist, betaxolol, and is reproduced by the intra-BNST micro-infusions of the beta-2 adrenergic receptor agonist, clenbuterol, but not the beta-1 receptor agonist, dobutamine (Vranjkovic et al., 2014).

NE-CRF Interactions in the BNST

In the BNST, adrenergic receptors work in concert with and/or engage neuropeptide signaling to promote cocaine seeking. The actions of a number of neuropeptides in the BNST, including PACAP (Miles et al., 2017), orexins (Conrad et al., 2012), and dynorphin (Le et al., 2018), have been implicated in stressor-induced drug seeking. However, much emphasis has been placed on corticotropin releasing factor (CRF). Systemic (Shaham et al., 1998) or icv (Erb et al., 1998) CRF antagonist administration prevents shock-induced reinstatement following self-administration in rats and systemic CRF receptor antagonism prevents forced swim-induced reinstatement following CPP in mice (McReynolds et al., 2014), while icv CRF is sufficient to induce cocaine seeking (Erb et al., 2005). The contribution of CRF to stressor-induced cocaine seeking involves actions in the BNST, as intra-BNST CRF antagonist administration blocks shock-induced cocaine seeking in rats (Erb and Stewart, 1999).

CRF signaling in the BNST that contributes to cocaine seeking is regulated by NE. Indeed, reinstatement of cocaine seeking by icv NE following self-administration in rats (Brown et al., 2009) or CPP by systemic clenbuterol in mice (McReynolds et al., 2014) is prevented by CRF receptor antagonism. Clenbuterol administration to mice also increases CRF mRNA levels in the BNST (McReynolds et al., 2014), while intra-BNST administration of the CRF-R1 receptor antagonist, antalarmin, prevents reinstatement of cocaine seeking in response to intra-BNST administration of the beta-2 adrenergic receptor agonist clenbuterol (Vranjkovic et al., 2014). Although, CRF release from neurons originating in the CeA may be involved (Erb et al., 2001), work from Winder and colleagues suggests that beta adrenergic receptors promote excitatory regulation of key BNST output pathways involved in cocaine seeking via a mechanism that requires CRF release from a local population of BNST neurons and CRF-R1 receptor activation (Nobis et al. 2011; Silberman et al., 2013).

CRF-Releasing BNST Inputs into the VTA

BNST projections to the ventral tegmental area (VTA) are critical for stressor-triggered drug seeking. These projections include both GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons (Kaufling et al., 2017) although the subpopulation of these neurons that express CRF (Rodaros et al., 2007; Vranjkovic et al., 2014) are primarily GABAergic (Dabrowska et al. 2013). Beta adrenergic receptor agonist application to brain slices containing the BNST promotes excitatory synaptic regulation of retro-labeled VTA-projecting CRF-positive neurons via CRF-R1-dependent glutamate release (Silberman et al., 2013). Shock-induced cocaine seeking following self-administration is associated with increased VTA extracellular CRF levels in rats (Wang et al., 2005) and intra-VTA injections of CRF are sufficient to reinstate extinguished cocaine seeking (Wang et al., 2005; Blacktop et al., 2010). Pharmacological inhibition of the VTA (McFarland et al., 2004) or intra-VTA micro-infusions of CRF receptor antagonists prevent shock-induced cocaine seeking in rats following self-administration (Wang et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2007; Blacktop et al., 2011). Although others have reported that stressor-induced reinstatement involves CRF-R2 receptors in the VTA (Wang et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2014), we have found that shock-induced cocaine seeking following self-administration in rats is mediated by CRF-R1, but not CRF-R2 receptors (Blacktop et al., 2011). Intra-VTA delivery of a CRF-R1, but not CRF-R2, antagonist prevents shock-induced cocaine seeking, while intra-VTA administration of a selective CRF-R1, but not CRF-R2, agonist, reproduces the reinstating effects of shock (Blacktop et., 2011). Consistent with our findings, it has been reported that shRNA knockdown of CRF-R1 in the VTA prevents reinstatement of cocaine seeking by food deprivation following self-administration in mice (Chen et al., 2014). Using a pharmacological disconnection approach in which we administered the beta-2 adrenergic receptor antagonist, ICI-118,551, into the BNST in one hemisphere and the CRF-R1 antagonist, antalarmin, into the contralateral VTA, we have demonstrated that the beta-2 receptor regulated CRF-releasing pathway from the BNST to the VTA is required for shock-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking following self-administration in rats (Vranjkovic et al., 2014). It is important to note, however, that other brain regions send CRF projections to the VTA (Rodaros et al. 2007) and may be involved in stressor-triggered drug seeking.

VTA Projections to the Prelimbic PFC

The VTA sends dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic projections to key regions involved in motivation and drug seeking, including the PFC and NAc core. Our research has focused on pathway from the VTA to the dorsomedial PFC, including the prelimbic cortex – a region considered to have homology with components of the human PFC (e.g., dorsolateral PFC and anterior cingulate cortex; Uylings et al., 2003) that been implicated in cocaine craving (Grant et al., 1996; Breiter et al., 1997; Maas et al., 1998; Kilts et al., 2001; Wexler et al., 2001). Shock-triggered cocaine seeking in rats is associated with increased Fos reactivity in the prelimbic cortex and in retro-labeled prelimbic-projecting VTA neurons (Vranjkovic et al., 2018), which aligns with findings that subpopulations of VTA neurons encode aversive events (Brischoux et al. 2009; Ungless et al. 2010). Consistent with findings that inhibiting the prelimbic cortex using baclofen/muscimol (McFarland et al., 2004) or tetrodotoxin (Capriles et al., 2003) prevents shock-triggered cocaine seeking, we have found that inhibition of prelimbic-projecting VTA neurons using an intersectional DREADD (Designer Receptor Exclusively Activated by Designer Drug) approach in delivery of a virus encoding retro-AAV Cre into the prelimbic cortex and a Cre-dependent hM4Di-expressing vector into the VTA prevents shock-triggered reinstatement of cocaine seeking following self-administration in rats (Vranjkovic et al., 2018).

Prelimbic PFC Dopamine and D1 Receptors

Stressor-triggered cocaine seeking is associated with activation of dopamine neurons in the VTA as measured by Fos expression in tyrosine hydroxylase-positive neurons (McReynolds et al., 2018) and increased extracellular dopamine likely reflecting somatodendritic release (Wang et al., 2005). Chemogenetic activation of VTA dopamine neurons induces cocaine seeking in rats following self-administration and extinction (Mahler et al., 2019). However, stressor regulation of VTA dopamine neurons varies according to the field of neuronal projection. Whereas stressors produce robust increases in dopamine in the PFC (Thierry et al., 1976; Reinhard Jr. et al., 1982; Deutch et al., 1985; Speciale et al., 1986), stressor and CRF effects on NAc dopamine are more complex with reports of increases, reductions, or no effect, depending on the nucleus accumbens subregion, stressor, context, and timeframe (Abercrombie et al., 1989; Puglisi-Allegra et al., 1991; Kalivas and Duffy, 1995; Tidey and Miczek, 1996; Lammel et al., 2011; Badrinarayan et al., 2012; Roitman et al., 2008; Oleson et al., 2012; Wanat et al., 2013; Twining et al., 2015; Brodnik et al. 2020). For example, predator odor exposure can increase the motivation to take cocaine and enhance the reinstating effect of drug-associated cues in susceptible, but not resilient, rats (Schwendt et al. 2018; Brodnik et al. 2017), possibly through enhancement of cocaine-induced dopamine transient frequency in the nucleus accumbens (Brodnik et al. 2020). Shock-triggered cocaine seeking in rats is blocked by dopamine D1 receptor antagonist micro-infusions into the prelimbic cortex (Capriles et al., 2003; McFarland et al., 2004), but not the NAc core (McFarland et al., 2004). Altogether, these findings suggest that CRF release into the VTA from neurons originating in the BNST activates CRFR1 receptors to excite VTA dopamine neurons that project to the prelimbic cortex, resulting in dopamine release, D1 receptor activation, and cocaine seeking. Consistent with this model, we have found that pharmacological disconnection of the VTA-prelimbic cortex pathway by administration of the CRF-R1 antagonist, antalarmin, into the VTA in one hemisphere, and administration of the D1 receptor antagonist SCH 23390 into the prelimbic cortex of the contralateral hemisphere prevents shock-triggered cocaine seeking following self-administration in rats (Vranjkovic et al., 2018).

Regulation of Nucleus Accumbens Core-Projecting PrL PFC Neurons

In the prelimbic cortex, D1 receptors are expressed on and heighten excitability of subpopulations of pyramidal neurons (Lewis and O’Donnell, 2000; Seamans et al., 2001; Tseng and O’Donnell, 2004; Thurley et al., 2008) thereby promoting activation of key output pathways that are thought to mediate cocaine seeking. Although other output pathways may contribute (e.g., paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus/PVT, Giannotti et al., 2018; and dorsal periaqueductal grey, Siciliano et al., 2019), projections from the prelimbic cortex to the NAc core appear to be particularly important for cocaine seeking (Stefanik et al., 2013a; 2016; McGlinchey et al., 2016). While the projections are predominantly ipsilateral (Sesack et al. 1989), both ipsi- and contralateral projections are involved in cocaine-seeking behavior (McGlinchey et al. 2016; James et al. 2018). Pharmacological inhibition of the prelimbic cortex using baclofen/muscimol prevents both shock-induced cocaine seeking and the corresponding increase in extracellular glutamate levels in the NAc core (McFarland et al., 2004), while inhibition of the NAc core prevents shock-induced reinstatement following self-administration in rats (McFarland et al., 2004). Consistent with findings that cue-induced cocaine seeking requires activation of neurons that project from the NAc core to the ventral pallidum (Stefanik et al., 2013b), pharmacological inhibition of the ventral pallidum prevents shock-induced cocaine seeking following self-administration in rats (McFarland et al., 2004).

A diagram depicting the pathways and mechanisms that contribute to stress-triggered cocaine seeking reviewed in this paper is included in Figure 1. Notably, this review is not comprehensive. Other signaling systems (e.g., dynorphin/kappa opioid receptors, Beardsley et al., 2005; Redila and Chavkin, 2008; neurokinins, Schank et al., 2014; PACAP, Miles et al., 2018; and orexins, Schmeichel et al., 2017) and structure/circuits (e.g., lateral hypothalamus to CeA, Tung et al., 2016; lateral habenula, Gill et al., 2013; dorsal raphe nucleus to NAc, Land et al., 2009) have been implicated in stress-triggered cocaine seeking.

Translational Challenges with the Stress-Triggered Reinstatement Model

While preclinical rodent studies have produced relatively clear and consistent findings regarding the mechanisms and neurocircuitry that mediate stress-triggered drug seeking, attempts to translate these findings to clinical application have had very limited success. Although alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist drugs such as clonidine, guanfacine, and lofexidine have been used with some success to mitigate cocaine craving in response to stress imagery (Jobes et al., 2011; Fox et al., 2012) and have long been used to manage opioid withdrawal symptoms as combination therapy (Gowing et al., 2016), their utility for relapse prevention is unclear due to variability in effectiveness in reducing stress-induced craving and the need for additional clinical trials. By contrast, trials assessing the utility of CRF-R1 receptor antagonists in SUDs have produced negative results (Kwako et al., 2015; Schwandt et al., 2016), leading some to question preclinical models used to study the contribution of stress to cocaine and other disorders and the targets that they yield (Shaham and de Wit, 2016; Murrough and Charney, 2017). Thus, there has been a need to re-examine the role that stress plays in cocaine use disorder and to develop preclinical approaches that better reflect the human condition.

3. Stress-potentiated cocaine seeking

Although periods of stress often lead up to cocaine use, they do not reliably predict the timing and magnitude of cocaine craving (Preston and Epstein, 2011; Furnari et al., 2015). A likely reason for this is that, in many people, stress may interact with other stimuli (e.g., drug-associated cues or drug re-exposure) to promote relapse. Indeed, in some situations, personalized stress imagery is not sufficient to elicit robust craving in cocaine-dependent subjects (De La Garza et al., 2018) and many imagery scripts that directly trigger craving also incorporate imagery related to drug procurement and use. It has been reported that stress can function cooperatively with other stimuli that promote craving (Duncan et al., 2007; Moran-Santa Maria et al., 2014; Preston et al., 2018). In many subjects, stress, under conditions where it does not elicit craving, appears to potentiate cue-induced craving, thereby “setting the stage” for cocaine use (Preston et al., 2018).

Much like in people, we and others have found that, under conditions in which stress alone does not reliably reinstate extinguished cocaine seeking in rats, it can augment reinstatement in response to drug-associated cues (Buffalari et al., 2009) or administration of a low dose of cocaine that by itself is insufficient to prime cocaine seeking (Graf et al., 2013). We have found that both footshock and restraint can potentiate cocaine-primed reinstatement (Graf et al., 2013; McReynolds et al., 2016; McReynolds et al., 2018; Doncheck et al., 2020), while See and colleagues have found that footshock (Buffalari and See, 2009) and yohimbine administration (Feltenstein and See, 2006; Buffalari and See, 2011) can potentiate reinstatement in response to cocaine-associated cues.

Role for Corticosterone

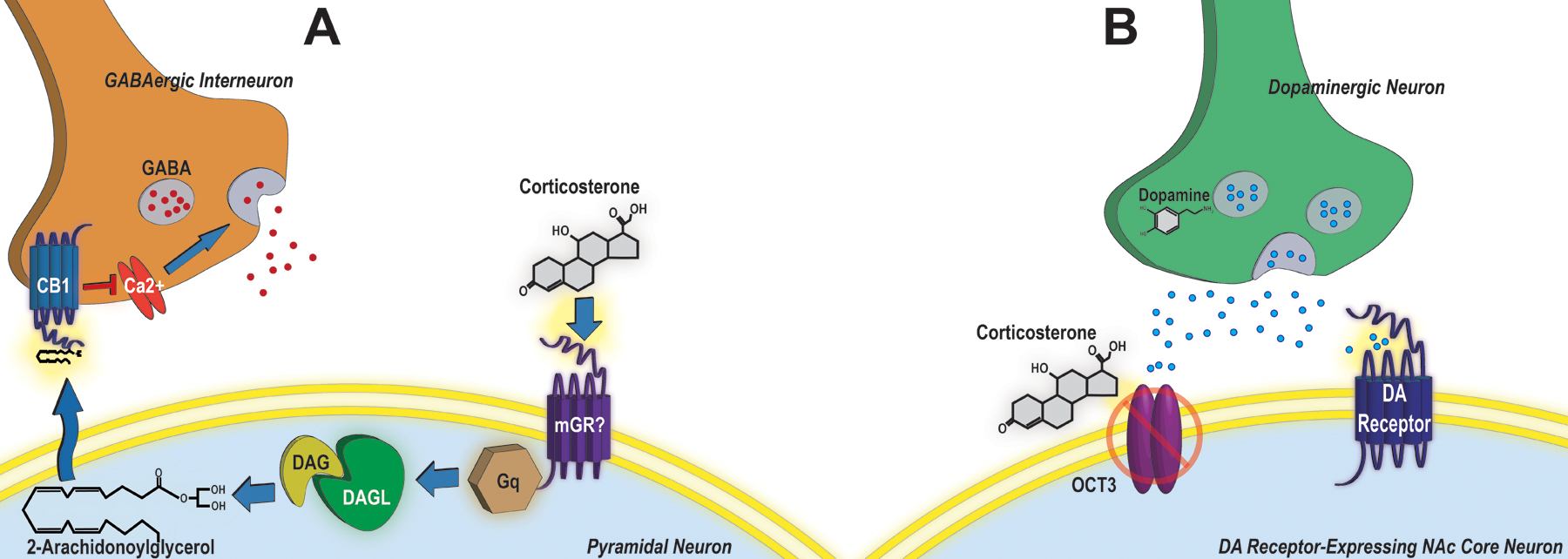

Consistent with clinical reports that elevated cortisol levels can promote cocaine craving (Elman et al., 1997), are associated with poor cocaine use disorder treatment outcomes (Ligabue et al., 2020), and predict cocaine use (Sinha et al., 2006), we have identified a critical role for corticosterone in the stage setting effects of stress on cocaine seeking. The ability of footshock stress to potentiate cocaine-primed reinstatement is eliminated by prior surgical adrenalectomy (Graf et al., 2013) and reproduced in both rat self-administration and mouse CPP models by administration of corticosterone, at a dose that results in plasma levels comparable to those observed following exposure to stressors (Graf et al., 2013; McReynolds et al., 2017). Notably, involvement of corticosterone in stress-potentiated reinstatement stands in contrast to its lack of involvement in stress-triggered cocaine seeking. Elimination of the corticosterone response to electric footshock by surgical adrenalectomy after repeated cocaine self-administration but prior to reinstatement testing fails to affect stresss-triggered cocaine seeking (Graf et al., 2011). The mechanisms through which corticosterone potentiates cocaine seeking are rapid and are not blocked by the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) antagonist, mifepristone (RU 486; Graf et al., 2013), suggesting a non-canonical (i.e., non-genomic) mechanism of action. As corticosterone readily penetrates the blood brain barrier and can engage multiple structures brain-wide, it is well-positioned to influence function at the network level and can do so through engagement of a variety of GR and non-GR targets and processes (Joëls et al., 2018). We have characterized two non-canonical mechanisms through which stressors, via corticosterone, potentiate cocaine-seeking behavior: 1) attenuation of dopamine clearance via blockage of the organic cation transporter 3 (OCT3) in the nucleus accumbens and 2) GR-independent endocannabinoid signaling and CB1 receptor-mediated attenuation of inhibitory synaptic transmission in the prelimbic cortex. Diagrams of these mechanisms are included in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Mechanisms implicated in corticosterone-mediated stress-potentiated reinstatement of cocaine seeking.

Stress can “set the stage” for cocaine seeking via at least two rapid signaling mechanisms that are independent of the canonical glucocorticoid receptor. A) In the prelimbic region of the prefrontal cortex, corticosterone engages an undefined membrane-associated target (mGR?) to mobilize the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoylglyerol (2-AG), likely via Gq G-protein-dependent production of diacylglycerol (DAG) and conversion to 2-AG via DAG lipase (DAGL). 2-AG is released retrogradely from pyramidal neurons (PNs) and engages CB1 receptors on GABAergic interneurons to attenuate Ca2+ influx and Ca2+-dependent GABA release, thereby removing PN inhibition and promoting excitability of output pathways the mediate cocaine seeking. B) In the nucleus accumbens (NAc), corticosterone directly binds to and inhibits the organic cation transporter (OCT3) on both neurons and astrocytes to attenuate dopamine transporter- (DAT) independent dopamine (DA) clearance, thus amplifying dopaminergic signaling and regulation of medium spiny neuron outputs that mediate cocaine seeking.

Organic Cation Transporter 3 in the Nucleus Accumbens

One site at which corticosterone contributes to stress-potentiated cocaine seeking is the NAc. Bilateral micro-infusions of corticosterone into the NAc reproduce the potentiating effects of stressors on reinstatement (Graf et al., 2013). The ability of stress-level corticosterone to potentiate cocaine seeking involves dopamine signaling in the NAc. Similar to cocaine seeking, corticosterone administration potentiates the NAc dopamine response to cocaine as measured using in vivo microdialysis and micro-infusions of non-selective dopamine receptor antagonist, fluphenazine, into the NAc prevents corticosterone-potentiated cocaine seeking (Graf et al., 2013). To further investigate the mechanism through which corticosterone influences dopaminergic signaling, we used in vivo fast scan cyclic voltammetry. We found that corticosterone reduced dopamine clearance, thereby amplifying the NAc dopamine response to cocaine (Graf et al., 2013; Wheeler et al., 2017). This effect on dopamine clearance was observed when the primary dopamine transporter (DAT) was occupied, suggesting a role for DAT-independent dopamine transport (Graf et al., 2013).

OCT3 is a low-affinity, high-capacity monoamine (norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, serotonin and histamine) transporter, one of a collection of transporters that contribute to what was previously known as uptake 2 (Gasser and Lowry, 2018). OCT3 is expressed in neurons and astrocytes throughout the brain, including in the NAc (Gasser et al., 2009; Gasser et al., 2017). While the precise role of OCT3 in regulating monoaminergic signaling is not well-defined, it appears to be important for clearance when primary transporters are saturated or at locations where primary transporters are not expressed. Corticosterone binds to OCT3 and inhibits OCT3-dependent transport. Thus, we hypothesize that during stress, corticosterone inhibits OCT3-mediated dopamine clearance in the NAc to boost dopamine signaling and drug seeking, especially in the presence of cocaine when DAT is blocked (Figure 2B). In support of this hypothesis, the ability of stress and corticosterone to potentiate cocaine-primed reinstatement following either self-administration in rats or CPP in mice is reproduced by the non-glucocorticoid OCT3 inhibitor, normetanephrine (Graf et al., 2013; McReynolds et al., 2017). Moreover, neither corticosterone- nor normetanephrine-potentiated reinstatement of cocaine seeking following CPP is observed in OCT3 knockout mice (McReynolds et al., 2017).

Endocannabinoid Signaling in the Prelimbic Prefrontal Cortex

A second site at which corticosterone can act to promote cocaine seeking through stage-setting effects is the prelimbic cortex. Similar to stress and stress-level corticosterone, micro-infusions of corticosterone into the prelimbic cortex also potentiate cocaine-primed reinstatement (McReynolds et al., 2018; Doncheck et al., 2020). We have identified a role for endocannabinoid signaling in the prelimbic cortex in stress-potentiated cocaine seeking. As is the case with corticosterone, we have found that endocannabinoid signaling through CB1 receptors is required for stress-potentiated, but not stress-triggered, reinstatement (McReynolds et al., 2016). This contribution of CB1 receptors involves the prelimbic cortex, as micro-infusions of the CB1 receptor inverse agonist, AM-251, prevents potentiated cocaine seeking following self-administration in response to shock, restraint, and stress-level corticosterone (McReynolds et al., 2018; Doncheck et al., 2020), while intra-prelimbic delivery of the CB1 receptor agonist, WIN 55,212-2, reproduces the effects of stress and corticosterone (McReynolds et al., 2018). It has previously been reported that corticosterone can increase 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) content in the prelimbic cortex (Hill et al., 2011). Consistent with a role for 2-AG in corticosterone-mediated effects on cocaine seeking, we have found that corticosterone-potentiated cocaine seeking is prevented by micro-infusions of an inhibitor of diacylglycerol (DAG) lipase, the enzyme required for 2-AG synthesis, into the prelimbic cortex. Additionally, potentiated reinstatement is reproduced by accumulation of 2-AG in the prelimbic cortex as a result of micro-infusions of an inhibitor of monoacylglycerol (MAG) lipase, which hydrolyzes 2-AG (McReynolds et al., 2018). By contrast, corticosterone has been reported to have no acute effects on anandamide levels in the prefrontal cortex (Hill et al., 2010) and we have found that micro-infusions of a fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inhibitor fail to potentiate cocaine seeking (unpublished data).

In the prelimbic cortex, CB1 receptors are predominantly (but not exclusively) localized to GABAergic terminals (Hill et al., 2011), likely on CCK+ GABAergic interneurons (Kotona et al., 1999; Eggan et al., 2010). Retrograde release of 2-AG from the dendrites of pyramidal neurons in the prelimbic cortex could engage these inhibitory receptors to attenuate GABA release. Consistent with this possibility, using ex vivo whole cell recordings in slice we have found that corticosterone application rapidly attenuates the frequency but not amplitude of miniature inhibitory post-synaptic currents in layer V pyramidal neurons in the rat prelimbic cortex (McReynolds et al., 2018; Doncheck et al., 2020). This effect is inhibited the CB1 inverse agonist AM-251 and the DAG lipase inhibitor, DO-34 (McReynolds, et al., 2018; Doncheck et al., 2020). Thus, we hypothesize that, during stress, corticosterone mobilizes 2-AG, which inhibits GABA release from interneurons via CB1 receptors, thereby rendering output pathways that contribute to cocaine seeking, more responsive to excitatory inputs and more susceptible to activation. Ongoing work is aimed at defining these output pathways. Preliminary data using intersectional DREADD expression has implicated the pathway from the prelimbic cortex to the NAc core (unpublished data). Other projections (e.g., to the PVT) are also being examined.

The mechanism through which corticosterone rapidly mobilizes 2-AG and regulates synaptic transmission and behavior is GR-independent and likely involves G-protein signaling, similar to prior reports in other brain regions (e.g., Di et al., 2009; Di et al., 2016). We hypothesize that corticosterone, through either direct receptor engagement or via a heteromeric signaling complex, engages Gq G-protein signaling to mobilize DAG, a substrate for DAG lipase that is converted to 2-AG (Figure 2A). This mechanism is currently under investigation.

4. Factors that influence stress-induced cocaine seeking

History of Drug Use

Despite defining diagnostic criteria (DSM 5), cocaine use disorder, like other SUDs, is heterogeneous in terms of symptoms and severity, and it is progressive. Accordingly, the role of stress in cocaine use disorder varies across individuals. Understanding the factors that influence the contribution of stress to cocaine seeking is critical for both prevention and treatment efforts. In harmony with clinical observations, we have found that stressors “set the stage” for (i.e., potentiate) cocaine seeking in some rats and directly trigger cocaine seeking in others. One key factor that determines the impact of stressors on cocaine seeking is the history of cocaine use. Consistent with reports that stressor-induced craving and associated physiological responses are heightened in individuals with a history of higher vs. lower frequency of cocaine use (Fox et al., 2005), we have found that stress-triggered cocaine seeking in rats depends on the prior pattern/amount of cocaine self-administration (Mantsch et al., 2008a). Male rats with a history of long-access cocaine self-administration (14 × 6–10 hrs/day) show robust shock-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking, while rats with a history of short-access self-administration (14 × 1–2 hrs/day) do not. Thus, repeated cocaine use appears to produce intake-dependent neuroadaptations that amplify stress-related responses and their impact on future cocaine seeking.

While this finding has implications for future studies of stress-related triggers for drug seeking, it is important to acknowledge that the pattern of drug intake may also be a factor in the development of these behaviors. Experienced human cocaine users have reported consuming cocaine in fewer, larger doses compared to inexperienced users, indicating a higher inter-drug use interval (Zimmer et al. 2012). This pattern leads to “spikes” of drug concentration in the brain, as opposed to more consistent levels. This aspect of cocaine use disorder can be modeled using an intermittent-access paradigm where rodents are allowed to self-administer cocaine during a brief 5-min window that is followed by a 25-min timeout session, during which no drug can be taken. This 30-min session is then repeated twelve times for a total session length of 6 hours, and results in large, rapid amounts of self-administered cocaine (“spikes”; Zimmer et al. 2012). Animals undergoing intermittent-access self-administration show an increase in a number of addiction-related measures, include Pmax (a measure to determine the motivation to self-administer drug), escalation of drug intake, resistance to punished drug-taking, and cue- and drug-induced reinstatement (Garcia et al. 2020; Tung et al. 2016; Zimmer et al. 2012; Kawa et al. 2016) compared to animals undergoing standard short-or long-access cocaine self-administration. Intermittent access also promotes the emergence of a negative affective state upon cessation of drug use which could drive drug use after abstinence (Tung et al. 2016). To our knowledge, the effects of intermittent-access self-administration on stress-induced reinstatement (whether triggered or potentiated) have not been examined.

One set of adaptations that appears to be critical for promoting stressor-induced cocaine seeking in rodent models involves CRF signaling in the VTA. Consistent with reports that repeat cocaine exposure upregulates CRF binding (Goeders et al., 1990), enhances CRF-R1 dependent CRF signaling and regulation of excitatory transmission (Hahn et al., 2009), and establishes CRF control of dopaminergic signaling (Wang et al., 2005) in the VTA, we have found that self-administration under long-access conditions recruits VTA CRF signaling to establish CRF-dependent regulation of cocaine-seeking behavior. As is the case with footshock stress, the ability of intra-VTA micro-infusions to reinstate drug seeking is only observed in rats with a history of long-access cocaine self-administration (Blacktop et al., 2011). We have found that this recruitment of CRF-dependent cocaine seeking is associated with increased CRF-R1 mRNA levels in the VTA and a heightened CRF-R1 dependent Fos response in the prelimbic cortex (Vranjkovic et al., 2018). Based on these observations we hypothesize that excessive cocaine use produces persistent increases in CRF-R1 receptors on VTA dopamine neurons that project to the prelimbic cortex, thereby promoting stress-induced drug seeking.

We have also begun to explore the neurobiological processes through which long-access cocaine self-administration recruits VTA CRF signaling and stress-triggered cocaine seeking. Cocaine self-administration elevates corticosterone levels in plasma (Galici et al., 2000; Mantsch et al., 2000) and brain (Palamarchouk et al., 2009). Under conditions of long-access self-administration, these elevations are prolonged and more-pronounced (Mantsch et al., 2003). Based on prior observations that elevated corticosterone produces allostatic alterations in CRF signaling that contribute to neuropathology (Schulkin et al., 1998), we examined the contribution of elevated corticosterone to heightened stressor- and CRF-induced cocaine seeking following long-access cocaine self-administration in rats. When animals underwent surgical adrenalectomy and subsequent corticosterone replacement prior to the 14-day long-access self-administration period, we did not observe reinstatement of cocaine seeking in response to shock or icv CRF (Graf et al., 2011). By contrast, when rats experienced the same surgical/corticosterone replacement conditions following self-administration but prior to reinstatement testing, reinstatement was comparable to sham-operated controls, suggesting that the adrenal response at the time of cocaine use, but not thereafter, is required for drug-induced adaptations that establish susceptibility to stress-triggered reinstatement. Interestingly, while the adrenal response is required, elevated corticosterone alone does not appear to be sufficient to establish relapse susceptibility. Recapitulation of the elevated plasma corticosterone observed during long-access cocaine self-administration fails to alter reinstatement in rats provided daily short access to cocaine (Mantsch et al., 2008b). Thus, other adrenal hormones may contribute cocaine-induced neuroadaptations that promote stress-triggered relapse. One likely contributor is epinephrine, which can signal into the brain via stimulation of the vagus nerve (Miyashita and Williams, 2006) and has found to play a cooperative role along with corticosterone in cocaine-induced behavioral plasticity (de Jong et al., 2009).

Sex Differences in Stress-Induced Cocaine Seeking

Sex differences in stress-related cocaine seeking have also been identified. Although women are less likely to use cocaine than men, it has been reported that women more rapidly progress to the diagnostic criteria for cocaine use disorder (Griffin et al., 1989; Kosten et al., 1993; Haas and Peters, 2000) and show greater susceptibility to cocaine craving (Robbins et al., 1999; Elman et al., 2001; Kennedy et al., 2013). Evidence also suggests that women are more vulnerable to stress-related relapse. Cocaine-dependent women display greater subjective responses to stressors (Back et al., 2005) and heightened stressor-induced craving (Waldrop et al., 2010) compared to men. Interestingly, there appears to be sex differences in the circuitry and mechanisms implicated in stress-triggered cocaine seeking. Functional imaging studies have demonstrated that women with cocaine use disorder also show more pronounced stress-related activity of prefrontal cortical regions (Li et al., 2005) and cortico-striatal circuits (Potenza et al., 2012). Consistent with preclinical studies demonstrating that female rats are more susceptible to reinstatement of cocaine seeking following self-administration by yohimbine (Feltenstein et al., 2011), clinical studies have found that cocaine-dependent women display greater yohimbine-induced augmentation of cue-induced craving (Moran-Santa Maria et al., 2014). Moreover, it has been found that the alpha-2 agonist medication, guanfacine, more effectively reduces cocaine craving in women than in men (Fox et al., 2014). Female rats are more sensitive to reinstatement of cocaine seeking in response to icv delivery of CRF (Buffalari et al., 2012), while cocaine-dependent women show greater CRF reactivity (Brady et al., 2009). Notably, icv CRF delivery has been shown to differentially regulate functional connectivity in networks that include the extended amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and nucleus accumbens in female rats in a manner that appears to be influenced by estradiol (Wiersielis et al., 2016; Salvatore et al., 2018). There also appears to be sex differences in the stage-setting effects of stress. Although stressors potentiate cocaine-primed reinstatement in both male and female rats, footshock stress only potentiates cocaine seeking in males, while restraint stress potentiates cocaine seeking in both sexes (Doncheck et al., 2020). In both males and females, stress-potentiated reinstatement involves endocannabinoid-/CB1 receptor-mediated effects of corticosterone in the prelimbic cortex (Doncheck et al., 2020). However, females are more sensitive to cocaine-primed reinstatement, due to estradiol actions in the same brain region (Doncheck et al., 2018). Thus, the cumulative risk for cocaine seeking when stress and cocaine re-exposure are combined is heightened in female rats.

Comorbid Stress Disorders

Susceptibility to stress-induced cocaine seeking is particularly high in individuals with co-morbid stress-related disorders. This is especially evident with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Rates of PTSD co-morbidity are higher in those with cocaine use disorder (Chen et al., 2011). Further, PTSD symptom severity is predictive of craving for cocaine (Coffey et al., 2002; Saladin et al., 2003) and cocaine users entering treatment with co-morbid PTSD have poorer outcomes (Najavits et al., 2007). These observations are paralleled by findings in rodents that chronic social defeat stress (Covington and Miczek, 2001) or repeated footshock (Mantsch and Katz, 2007) produces persistent increases in cocaine self-administration and that prior exposure to predator odor can promote later cue-elicited cocaine seeking (Schwendt et al., 2018). More recently, we have found that chronic stress during cocaine self-administration heightens later stressor-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking (unpublished data). Similar to the effects of long-access cocaine self-administration, the effects of chronic stress on cocaine seeking require elevated corticosterone (Mantsch and Katz, 2007) and involve heightened CRF signaling in the VTA (Boyson et al., 2014; Holly et al., 2016).

Other Factors

Other factors that influence the risk for stressor-induced cocaine seeking include age, environmental enrichment, and social conditions. The impact of the cocaine is greater on the adolescent brain (Kwan et al., 2020), and it has been reported in rodent models that stressor-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking is greater during adolescence (Anker and Carroll, 2010) and during adulthood when rats self-administer cocaine throughout adolescence (Wong and Marinelli, 2016). Environmental enrichment attenuates yohimbine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking following self-administration in rats (Chauvet et al., 2009). The ability of social defeat stress to promote cocaine seeking in mice is heightened when mice are isolated during self-administration (Engeln et al., 2021). Future studies are needed to determine the neurobiological mechanisms through which these factors contribute to cocaine seeking during periods of stress.

Genetics

Genetic polymorphisms have been associated with cocaine use disorder. However, their collective influence is complex, representing an interplay between genetic predisposition and non-genetic determinants, including stress (Kreek et al., 2012). Work in this area has been somewhat limited. It has been reported that single nucleotide polymorphisms in 13 stress-related genes are associated with cocaine addiction (Levran et al., 2014) and that a variant on the kappa opioid receptor gene (OPRK1) is associated with stress-related drug craving (Xu et al., 2013). In cocaine-dependent individuals with co-morbid PTSD, the ability of trauma-related scripts to influence attendance to cocaine-associated cues is greater in those with a brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val66Met polymorphism (Bardeen et al., 2020). Understanding the genetic determinants of how stress influences cocaine seeking will permit identification of populations at greatest risk for stressor-induced relapse and for guiding interventions.

5. Generalization of findings cross drug classes

While it is beyond the scope of this review to describe in detail the neurobiological mechanism and neurocircuitry that underlies stressor-induced drug seeking for other drugs of abuse, it is important to recognize that there is evidence that many of the mechanisms mentioned here generalize across drug classes. The ability of stressors to reinstate drug seeking generalizes across drug classes. For example, intermittent footshock has been shown to reinstate drug seeking following cocaine (Erb et al., 1996: Ahmed and Koob, 1997), heroin (Shaham and Stewart, 1995), alcohol (Lê et al., 1998), and nicotine (Buczek et al., 1999), self-administration. In each case, shock-induced drug seeking is prevented by CRF receptor antagonism (Erb et al., 1998; Shaham et al., 1997; Lê et al., 2000; Zislis et al., 2007) or administration of an alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist (Erb et al., 2000; Shaham et al., 2000; Lê et al., 2005; Zislis et al., 2007). Additional work is needed to determine the degree to which common neurocircuitry and signaling mechanisms mediate shock-induced drug seeking across classes of drugs. Less is known about the stage-setting effects of stress in other drug classes. Blouin et al. (2020) have found that social defeat stress potentiates methamphetamine-induced reinstatement and the corresponding Fos response in the basolateral amygdala following self-administration in rats. However, the degree to which stress can potentiate drug seeking with other classes of drugs and the degree to which there is circuit and mechanistic overlap awaits further investigation.

6. Conclusions

There is little doubt that stress is a key contributor to craving and relapse in those diagnosed with cocaine use disorder. However, while preclinical research has led to the identification of pathways and mechanisms that mediate stressor-induced drug seeking in rodents, these findings have not translated well to clinical interventions. Thus, there is a need to re-examine the preclinical strategies that we use to study stress-related relapse. The development of more nuanced approaches that better capture the complex contribution of stress to drug craving and seeking (e.g., the stage-setting effects of stress) and the examination of stressor-induced drug seeking in models guided by reverse translation (Kuhn et al., 2019; Venniro et al., 2020), including those that incorporate voluntary abstinence (Venniro et al., 2019), have the potential to reveal novel and more relevant targets for interventions. To the extent that translatable mechanisms can be discovered, our ability to effectively leverage them will rely on our ability to diagnosis those with cocaine use disorder who drug seeking is stress driven.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH/NIDA grants DA052169 and DA048280 to J.R.M.

Abbreviations:

- 2-AG

2-arachidonoylglycerol

- BNST

bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

- CB1

cannabinoid receptor type 1

- CeA

central amygdala

- CPP

conditioned place preference

- CRF

corticotropin-releasing factor

- CRF-R1/2

corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 1/2

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- DREADD

Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs

- FAAH

fatty acid amide hydrolase

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- i.c.v.

intracerebroventricular

- LC

locus coeruleus

- NAc

nucleus accumbens

- OCT3

organic cation transporter 3

- PACAP

pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- PTSD

post-traumatic stress disorder

- SUD

substance use disorder

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no competing conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Abercrombie ED, Keefe KA, DiFrischia DS, Zigmond MJ (1989) Differential Effect of Stress on In Vivo Dopamine Release in Striatum, Nucleus Accumbens, and Medial Frontal Cortex. J. Neurochem 52, 1655–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Koob GF (1997) Cocaine- but not food-seeking behavior is reinstated by stress after extinction. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 132, 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Carroll ME (2010) Reinstatement of cocaine seeking induced by drugs, cues, and stress in adolescent and adult rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 208, 211–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Delfs JM, Druhan J, Zhu Y (1999) The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. A target site for noradrenergic actions in opiate withdrawal. Ann. NY Acad. Sci 877, 486–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back S, Dansky BS, Coffey SF, Saladin ME, Sonne S, Brady KT (2000) Cocaine dependence with and without posttraumatic stress disorder: A comparison of substance use, trauma history and psychiatric comorbidity. Am. J. Addict 9, 51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SE, Brady KT, Jackson JL, Salstrom S, Zinzow H (2005) Gender differences in stress reactivity among cocaine-dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 180, 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SE, Hartwell K, DeSantis SM, Saladin M, McRae-Clark AL, Price KL, Moran-Santa Maria MM, et al. (2010) Reactivity to laboratory stress provocation predicts relapse to cocaine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 106, 21–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badrinarayan A, Wescott SA, Weele CMV, Saunders BT, Couturier BE, Maren S, Aragona BJ (2012) Aversive stimuli differentially modulate real-time dopamine transmission dynamics within the nucleus accumbens core and shell. J. Neurosci 32, 15779–15790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banducci AN, Bujarski SJ, Bonn-Miller MO, Patel A, Connolly KM (2015) The impact of intolerance of emotional distress and uncertainty on veterans with co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorders. J. Anxiety Disord 41, 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardeen JR, Daniel TA, Gratz KL, Vallender EJ, Garrett MR, Tull MT (2020) The BDNF Val66Met Polymorphism Moderates the Relationship Between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Trauma Script-evoked Attentional Bias to Cocaine Cues Among Patients with Cocaine Dependence. J. Anxiety Disord 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley PM, Howard JL, Shelton KL, Carroll FI (2005) Differential effects of the novel kappa opioid receptor antagonist, JDTic, on reinstatement of cocaine-seeking induced by footshock stressors vs cocaine primes and its antidepressant-like effects in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 183, 118–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacktop JM, Seubert C, Baker DA, Ferda N, Lee G, Graf EN, Mantsch JR (2011) Augmented cocaine seeking in response to stress or CRF delivered into the ventral tegmental area following long-access self-administration is mediated by CRF receptor type 1 but not CRF receptor type 2. J. Neurosci 31, 11396–11403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin AM, Pisupati S, Hoffer CG, Hafenbreidel M, Jamieson SE, Rumbaugh G, Miller CA (2019) Social stress-potentiated methamphetamine seeking. Addict. Biol 24, 958–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyson CO, Holly EN, Shimamoto A, Albrechet-Souza L, Weiner LA, DeBold JF, Miczek KA (2014) Social stress and CRF-dopamine interactions in the VTA: Role in long-term escalation of cocaine self-administration. J. Neurosci 34, 6659–6667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, McRae AL, Maria MMMS, DeSantis SM, Simpson AN, Waldrop AE, Back SE, Kreek MJ (2009) Response to corticotropin-releasing hormone infusion in cocaine-dependent individuals. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 422–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiter HC, Gollub RL, Weisskoff RM, Kennedy DN, Makris N, Berke JD, Goodman JM, et al. (1997) Acute effects of cocaine on human brain activity and emotion. Neuron 19, 591–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briand LA, Vassoler FM, Pierce RC, Valentino RJ, Blendy JA (2010) Ventral tegmental afferents in stress-induced reinstatement: The role of cAMP response element-binding protein. J. Neurosci 30, 16149–16159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brischoux F, Chakraborty S, Brierley DI, Ungless MA (2009) Phasic excitation of dopamine neurons in ventral VTA by noxious stimuli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 4894–4899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodnik ZD, Black EM, Clark MJ, Kornsey KN, Snyder NW, España RA (2017) Susceptibility to traumatic stress sensitizes the dopaminergic response to cocaine and increases motivation for cocaine. Neuropharmacology 125, 295–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodnik ZD, Black EM, España RA (2020) Accelerated development of cocaine-associated dopamine transients and cocaine use vulnerability following traumatic stress. Neuropsychopharmacology 45, 472–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ZJ, Nobrega JN, Erb S (2011) Central injections of noradrenaline induce reinstatement of cocaine seeking and increase c-fos mRNA expression in the extended amygdala. Behav. Brain Res 217, 472–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ZJ, Tribe E, D’Souza NA, Erb S (2009) Interaction between noradrenaline and corticotrophin-releasing factor in the reinstatement of cocaine seeking in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 203, 121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczek Y, Lê AD, Wang A, Stewart J, Shaham Y (1999) Stress reinstates nicotine seeking but not sucrose solution seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 144, 183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalari DM, Baldwin CK, Feltenstein MW, See RE (2012) Corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF) induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in male and female rats. Physiol. Behav 105, 209–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalari DM, See RE (2009) Footshock stress potentiates cue-induced cocaine-seeking in an animal model of relapse. Physiol. Behav 98, 614–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalari DM, See RE (2011) Inactivation of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in an animal model of relapse: Effects on conditioned cue-induced reinstatement and its enhancement by yohimbine. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 213, 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calpe-López C, Gasparyan A, Navarrete F, Manzanares J, Miñarro J, Aguilar MA (2021). Cannabidiol prevents priming- and stress-induced reinstatement of the conditioned place preference induced by cocaine in mice. J. Psychopharmacol Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1177/0269881120965952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capriles N, Rodaros D, Sorge RE, Stewart J (2003) A role for the prefrontal cortex in stress- and cocaine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 168, 66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet C, Lardeux V, Goldberg SR, Jaber M, Solinas M (2009) Environmental enrichment reduces cocaine seeking and reinstatement induced by cues and stress but not by cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology 34, 2767–2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KW, Banducci AN, Guller L, Macatee RJ, Lavelle A, Daughters SB, Lejuez CW (2011) An examination of psychiatric comorbidities as a function of gender and substance type within an inpatient substance use treatment program. Drug Alcohol Depend. 118, 92–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen NA, Jupp B, Sztainberg Y, Lebow M, Brown RM, Kim JH, Chen A, Lawrence AJ (2014) Knockdown of CRF1 receptors in the ventral tegmental area attenuates cue- and acute food deprivation stress-induced cocaine seeking in mice. J. Neurosci 34, 11560–11570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Fiscella KA, Bacharach SZ, Tanda G, Shaham Y, Calu DJ (2015) Effect of yohimbine on reinstatement of operant responding in rats is dependent on cue contingency but not food reward history. Addict. Biol 20, 690–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Saladin ME, Drobes DJ, Brady KT, Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG (2002) Trauma and substance cue reactivity in individuals with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and cocaine or alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 65, 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KL, McCutcheon JE, Cotterly LM, Ford KA, Beales M, Marinelli M (2010) Persistent increases in cocaine-seeking behavior after acute exposure to cold swim stress. Biol. Psychiatry 68, 303–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KL, Davis AR, Silberman Y, Sheffler DJ, Shields AD, Saleh SA, Sen N, et al. (2012) Yohimbine depresses excitatory transmission in bnst and impairs extinction of cocaine place preference through orexin-dependent, norepinephrine-independent processes. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 2253–2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE, Miczek KA (2001) Repeated social-defeat stress, cocaine or morphine: Effects on behavioral sensitization and intravenous cocaine self-administration “binges.” Psychopharmacology (Berl). 158, 388–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska J, Hazra R, Guo JD, DeWitt S, Rainnie DG (2013) Central CRF neurons are not created equal: Phenotypic differences in CRF-containing neurons of the rat paraventricular hypothalamus and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Front. Neurosci 7, 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutch AY, Lee MC, Gillham MH, Cameron DA, Goldstein M, Iadarola MJ (1991) Stress selectively increases fos protein in dopamine neurons innervating the prefrontal cortex. Cereb. Cortex 1, 273–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di S, Itoga CA, Fisher MO, Solomonow J, Roltsch EA, Gilpin NW, Tasker JG (2016) Acute stress suppresses synaptic inhibition and increases anxiety via endocannabinoid release in the basolateral amygdala. J. Neurosci 36, 8461–8470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di S, Maxson MM, Franco A, Tasker JG (2009) Glucocorticoids regulate glutamate and GABA synapse-specific retrograde transmission via divergent nongenomic signaling pathways. J. Neurosci 29, 393–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doncheck EM, Liddiard GT, Konrath CD, Liu X, Yu L, Urbanik LA, Herbst MR, et al. (2020) Sex, stress, and prefrontal cortex: influence of biological sex on stress-promoted cocaine seeking. Neuropsychopharmacology 45, 1974–1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doncheck EM, Urbanik LA, Debaker MC, Barron LM, Liddiard GT, Tuscher JJ, Frick KM, Hillard CJ, Mantsch JR (2018) 17β-Estradiol Potentiates the Reinstatement of Cocaine Seeking in Female Rats: Role of the Prelimbic Prefrontal Cortex and Cannabinoid Type-1 Receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 43, 781–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan E, Boshoven W, Harenski K, Fiallos A, Tracy H, Jovanovic T, Hu X, Drexler K, Kilts C (2007) An fMRI study of the interaction of stress and cocaine cues on cocaine craving in cocaine-dependent men. Am. J. Addict 16, 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggan SM, Melchitzky DS, Sesack SR, Fish KN, Lewis DA (2010) Relationship of cannabinoid CB1 receptor and cholecystokinin immunoreactivity in monkey dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience 169, 1651–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elman I, Karlsgodt KH, Gastfriend DR (2001) Gender differences in cocaine craving among non-treatment-seeking individuals with cocaine dependence. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 27, 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elman I, Lukas SE, Karlsgodt KH, Gasic GP, Breiter HC (2003) Acute cortisol administration triggers craving in individuals with cocaine dependence. Psychopharmacol. Bull 37, 84–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engeln M, Fox ME, Lobo MK (2020) Housing conditions during self-administration determine motivation for cocaine in mice following chronic social defeat stress. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Hitchcott PK, Rajabi H, Mueller D, Shaham Y, Stewart J (2000) Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists block stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Neuropsychopharmacology 23, 138–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Salmaso N, Rodaros D, Stewart J (2001) A role for the CRF-containing pathway from central nucleus of the amygdala to bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 158, 360–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Shaham Y, Stewart J (1996) Stress reinstates cocaine-seeking behavior after prolonged extinction and a drug-free period. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 128, 408–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Shaham Y, Stewart J (1998) The role of corticotropin-releasing factor and corticosterone in stress- and cocaine-induced relapse to cocaine seeking in rats. J. Neurosci 18, 5529–5536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, Henderson AR, See RE (2011) Enhancement of cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats by yohimbine: Sex differences and the role of the estrous cycle. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 216, 53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, See RE (2006) Potentiation of cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats by the anxiogenic drug yohimbine. Behav. Brain Res 174, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Morgan PT, Sinha R (2014) Sex differences in guanfacine effects on drug craving and stress arousal in cocaine-dependent individuals. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 1527–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Seo D, Tuit K, Hansen J, Kimmerling A, Morgan PT, Sinha R (2012) Guanfacine effects on stress, drug craving and prefrontal activation in cocaine dependent individuals: Preliminary findings. J. Psychopharmacol 26, 958–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Talih M, Malison R, Anderson GM, Kreek MJ, Sinha R (2005) Frequency of recent cocaine and alcohol use affects drug craving and associated responses to stress and drug-related cues. Psychoneuroendocrinology 30, 880–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnari M, Epstein DH, Phillips KA, Jobes ML, Kowalczyk WJ, Vahabzadeh M, Lin JL, Preston KL (2015) Some of the people, some of the time: field evidence for associations and dissociations between stress and drug use. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 232, 3529–3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galici R, Pechnick RN, Poland RE, France CP (2000) Comparison of noncontingent versus contingent cocaine administration on plasma corticosterone levels in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol 387, 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia AF, Webb IG, Yager LM, Seo MB, Ferguson SM (2020) Intermittent but not continuous access to cocaine produces individual variability in addiction susceptibility in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 237, 2929–2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza R. D. La, Ashbrook LH, Evans SE, Jacobsen CA, Kalechstein AD, Newton TF (2009) Influence of verbal recall of a recent stress experience on anxiety and desire for cocaine in non-treatment seeking, cocaine-addicted volunteers. Am. J. Addict 18, 481–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser PJ, Hurley MM, Chan J, Pickel VM (2017) Organic cation transporter 3 (OCT3) is localized to intracellular and surface membranes in select glial and neuronal cells within the basolateral amygdaloid complex of both rats and mice. Brain Struct. Funct 222, 1913–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser PJ, Lowry CA (2009) Organic cation transporter 3: A cellular mechanism underlying rapid, non-genomic glucocorticoid regulation of monoaminergic neurotransmission, physiology, and behavior. Horm. Behav 104, 173–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser PJ, Orchinik M, Raju I, Lowry CA (2009) Distribution of organic cation transporter 3, a corticosterone-sensitive monoamine transporter, in the rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol 512, 529–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannotti G, Barry SM, Siemsen BM, Peters J, McGinty JF (2018) Divergent prelimbic cortical pathways interact with BDNF to regulate cocaine-seeking. J. Neurosci 38, 8956–8966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill MJ, Ghee SM, Harper SM, See RE (2013) Inactivation of the lateral habenula reduces anxiogenic behavior and cocaine seeking under conditions of heightened stress. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 111, 24–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE, Bienvenu OJ, Souza E. B. De (1990) Chronic cocaine administration alters corticotropin-releasing factor receptors in the rat brain. Brain Res. 531, 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowing L, Farrell M, Ali R, White JM (2016) Alpha₂-adrenergic agonists for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 2016, CD002024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf EN, Hoks MA, Baumgardner J, Sierra J, Vranjkovic O, Bohr C, Baker DA, Mantsch JR (2011) Adrenal activity during repeated long-access cocaine self-administration is required for later CRF-induced and CRF-dependent stressor-induced reinstatement in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 36, 1444–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf EN, Wheeler RA, Baker DA, Ebben AL, Hill JE, Mcreynolds JR, Robble MA, et al. (2013a) Corticosterone acts in the nucleus accumbens to enhance dopamine signaling and potentiate reinstatement of cocaine seeking. J. Neurosci 33, 11800–11810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf EN, Wheeler RA, Baker DA, Ebben AL, Hill JE, Mcreynolds JR, Robble MA, et al. (2013b) Corticosterone acts in the nucleus accumbens to enhance dopamine signaling and potentiate reinstatement of cocaine seeking. J. Neurosci 33, 11800–11810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant S, London ED, Newlin DB, Villemagne VL, Liu X, Contoreggi C, Phillips RL, Kimes AS, Margolin A (1996) Activation of memory circuits during cue-elicited cocaine craving. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 93, 12040–12045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin ML, Weiss RD, Mirin SM, Lange U (1989)A comparison of male and female cocaine abusers. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 46, 122–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzanna R, Fritschy JM (1991) Efferent projections of different subpopulations of central noradrenaline neurons. Prog. Brain Res 88, 89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AL, Peters RH (2000) Development of substance abuse problems among drug-involved offenders. Evidence for the telescoping effect. J Subst Abuse. 12, 241–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn J, Woodward Hopf F, Bonci A (2009) Chronic cocaine enhances corticotropin-releasing factor-dependent potentiation of excitatory transmission in ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. J. Neurosci 29, 6535–6544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MN, Karatsoreos IN, Hillard CJ, McEwen BS (2010) Rapid elevations in limbic endocannabinoid content by glucocorticoid hormones in vivo. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35, 1333–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MN, McLaughlin RJ, Pan B, Fitzgerald ML, Roberts CJ, Lee TTY, Karatsoreos IN, et al. (2011) Recruitment of prefrontal cortical endocannabinoid signaling by glucocorticoids contributes to termination of the stress response. J. Neurosci 31, 10506–10515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holly EN, Boyson CO, Montagud-Romero S, Stein DJ, Gobrogge KL, DeBold JF, Miczek KA (2016) Episodic social stress-escalated cocaine self-administration: Role of phasic and tonic corticotropin releasing factor in the anterior and posterior ventral tegmental area. J. Neurosci 36, 4093–4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James MH, McGlinchey EM, Vattikonda A, Mahler SV, Aston-Jones G (2018) Cued Reinstatement of Cocaine but Not Sucrose Seeking Is Dependent on Dopamine Signaling in Prelimbic Cortex and Is Associated with Recruitment of Prelimbic Neurons That Project to Contralateral Nucleus Accumbens Core. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol 21, 89–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobes ML, Ghitza UE, Epstein DH, Phillips KA, Heishman SJ, Preston KL (2011) Clonidine blocks stress-induced craving in cocaine users. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 218, 83–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joëls M Corticosteroids and the brain. (2018) J. Endocrinol 238, R121–R130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong I. E. M. De, Steenbergen PJ, Kloet E. R. De (2009) Behavioral sensitization to cocaine: Cooperation between glucocorticoids and epinephrine. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 204, 693–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Duffy P (1995) Selective activation of dopamine transmission in the shell of the nucleus accumbens by stress. Brain Res. 675, 325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona I, Sperlágh B, Sík A, Käfalvi A, Vizi ES, Mackie K, Freund TF (1999) Presynaptically located CB1 cannabinoid receptors regulate GABA release from axon terminals of specific hippocampal interneurons. J. Neurosci 19, 4544–4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawa AB, Bentzley BS, Robinson TE (2016) Less is more: prolonged intermittent access cocaine self-administration produces incentive-sensitization and addiction-like behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 233, 3587–3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufling J, Girard D, Maitre M, Leste-Lasserre T, Georges F (2017) Species-specific diversity in the anatomical and physiological organisation of the BNST-VTA pathway. Eur. J. Neurosci 45, 1230–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy AP, Epstein DH, Phillips KA, Preston KL (2013) Sex differences in cocaine/heroin users: drug-use triggers and craving in daily life. Drug Alcohol Depend. 132, 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilts CD, Schweitzer JB, Quinn CK, Gross RE, Faber TL, Muhammad F, Ely TD, Hoffman JM, Drexler KPG (2001) Neural activity related to drug craving in cocaine addiction. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 58, 334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Kleber HD (1988) Differential diagnosis of psychiatric comorbidity in substance abusers. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 5, 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Gawin FH, Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ (1993) Gender differences in cocaine use and treatment response. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 10, 63–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Levran O, Reed B, Schlussman SD, Zhou Y, Butelman ER (2012) Opiate addiction and cocaine addiction: underlying molecular neurobiology and genetics. J. Clin. Invest 122, 3387–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreibich AS, Blendy JA (2004) cAMP response element-binding protein is required for stress but not cocaine-induced reinstatement. J. Neurosci 24, 6686–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]