Abstract

Background

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) comprises ankylosing spondylitis (radiographic axSpA) and non‐radiographic (nr‐)axSpA and is associated with psoriasis, uveitis and inflammatory bowel disease. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended as first‐line drug treatment.

Objectives

To determine the benefits and harms of NSAIDs in axSpA.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE to 18 June 2014.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs of NSAIDs versus placebo or any comparator in adults with axSpA and observational cohort studies studying the long term effect (≥ six months) of NSAIDs on radiographic progression or adverse events (AEs). The main comparions were traditional or COX‐2 NSAIDs versus placebo. The major outcomes were pain, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI), radiographic progression, number of withdrawals due to AEs and number of serious AEs

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials for inclusion, assessed the risk of bias, extracted data and assessed the quality of evidence for major outcomes using GRADE.

Main results

We included 39 studies (35 RCTs, two quasi‐RCTs and two cohort studies); and 29 RCTs and two quasi‐RCTs (n = 4356) in quantitative analyses for the comparisons: traditional NSAIDs versus placebo, cyclo‐oxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) versus placebo, COX‐2 versus traditional NSAIDs, NSAIDs versus NSAIDs, naproxen versus other NSAIDs, low versus high dose. Most trials were at unclear risk of selection bias (n = 29), although blinding of participants and personnel was adequate in 24 trials. Twenty‐five trials had low risk of attrition bias and 29 trials had low risk of reporting bias. Risk of bias in both cohort studies was high for study participation, and low or unclear for all other criteria. No trials in the meta‐analyses assessed patients with nr‐axSpA.

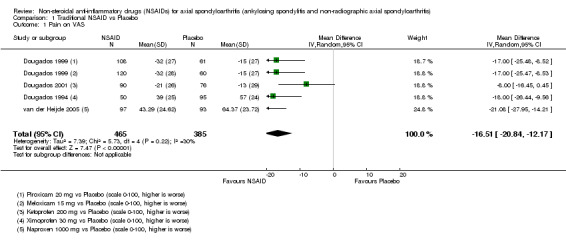

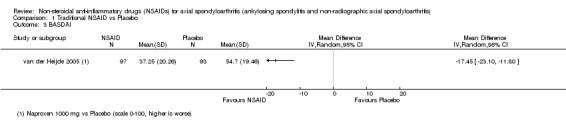

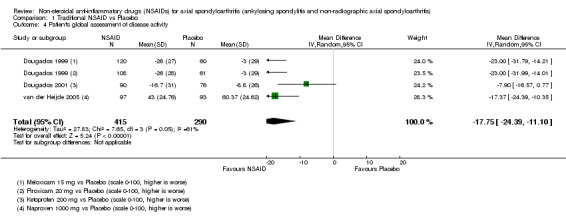

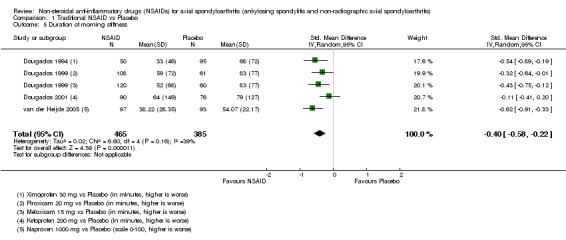

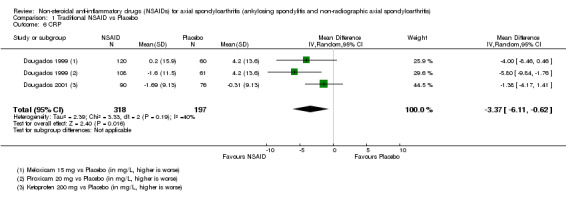

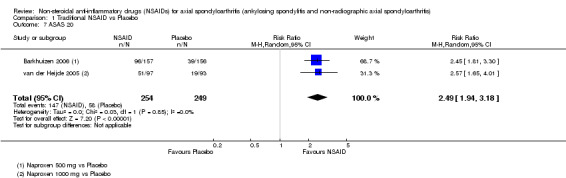

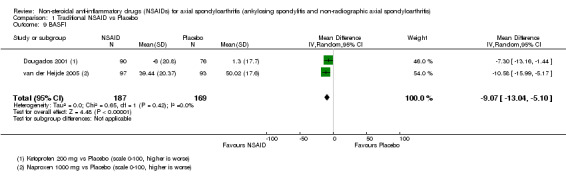

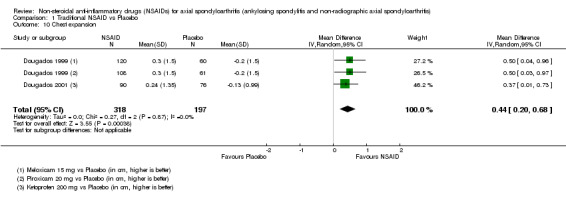

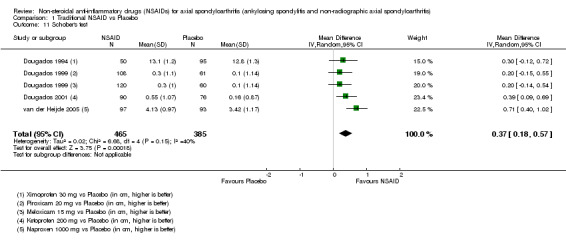

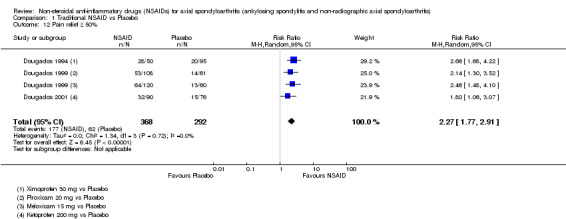

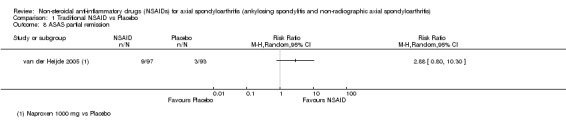

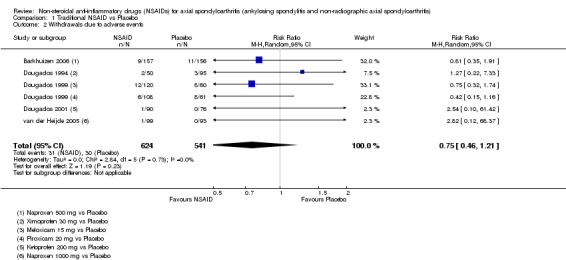

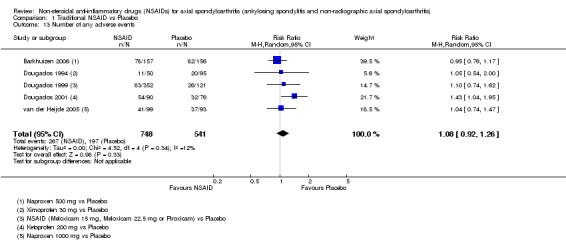

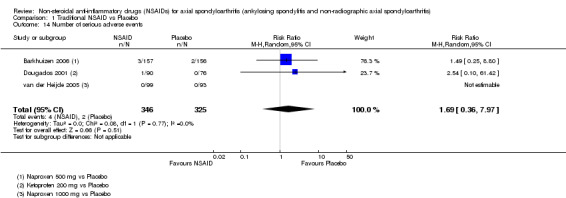

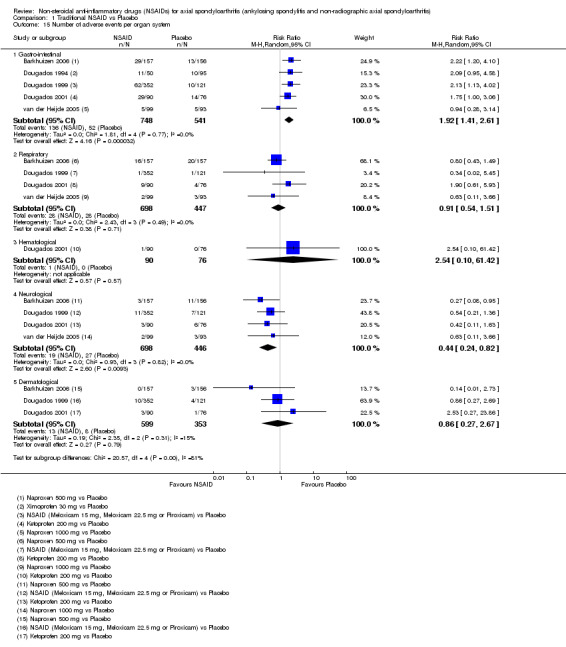

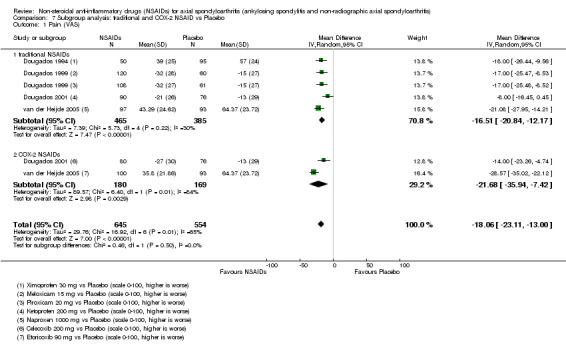

Traditional NSAIDs were more beneficial than placebo at six weeks. High quality evidence (four trials, N=850) indicates better pain relief with NSAIDs (pain in control group ranged from 57 to 64 on a 100mm visual analogue scale (VAS) and was 16.5 points lower in the NSAID group (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐20.8 to ‐12.2), lower scores indicate less pain, NNT 4 (3 to 6)); moderate quality evidence (one trial, n = 190) indicates improved disease activity with NSAIDs (BASDAI in control group was 54.7 on a 100‐point scale and was 17.5 points lower in the NSAID group, 95% CI ‐23.1 to ‐11.8), lower scores indicate less disease activity, NNT 3 (2 to 4)); and high quality evidence (two trials, n = 356) indicates improved function with NSAIDs (BASFI in control group was 50.0 on a 100‐point scale and was 9.1 points lower in the NSAID group (95% CI ‐13.0 to ‐5.1), lower scores indicate better functioning, NNT 5 (3 to 8)). High (five trials, n = 1165) and moderate (three trials, n = 671) quality evidence (downgraded due to potential imprecision) indicates that withdrawals due to AEs and number of serious AEs did not differ significantly between placebo (52/1000 and 2/1000) and NSAID (39/1000 and 3/1000) groups after 12 weeks (risk ratio (RR) 0.75, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.21; and RR 1.69, 95% CI 0.36 to 7.97, respectively). BASMI and radiographic progression were not reported.

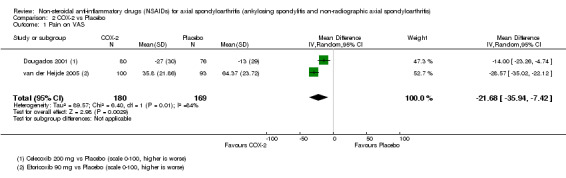

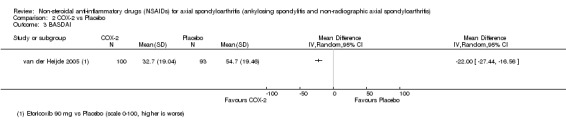

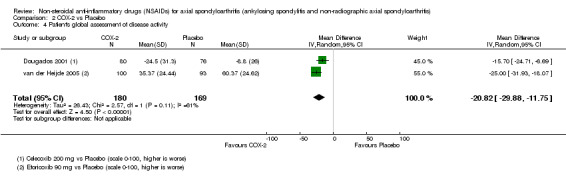

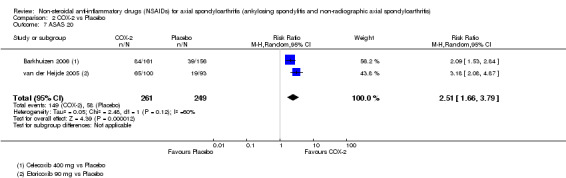

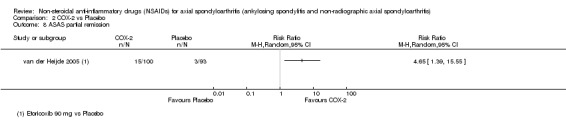

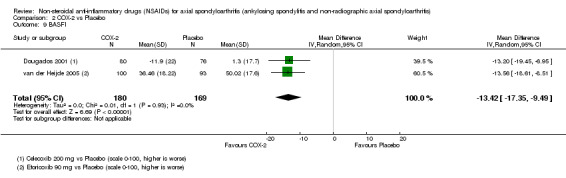

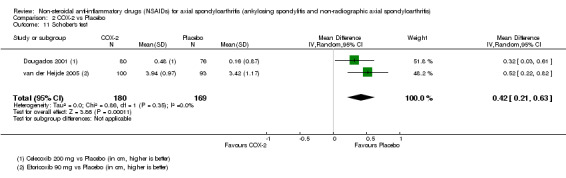

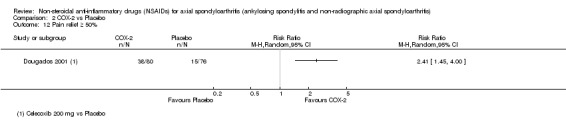

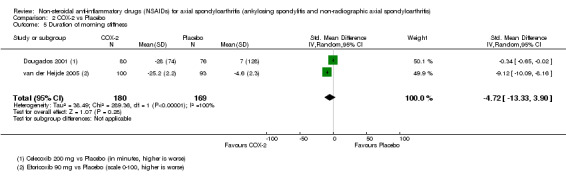

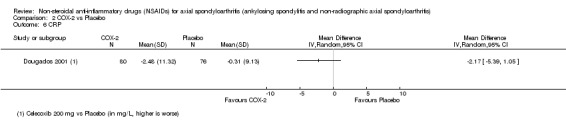

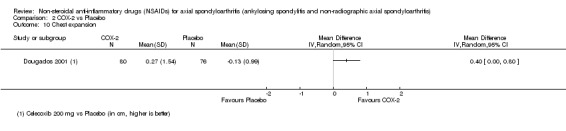

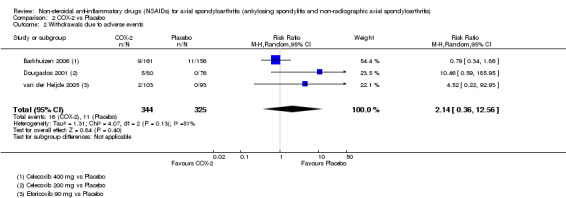

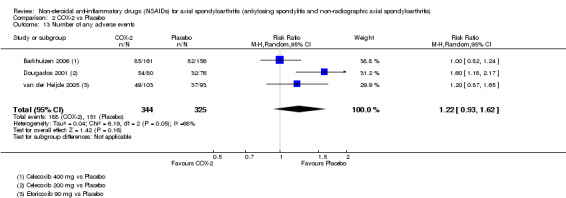

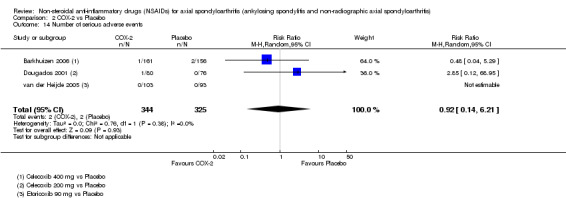

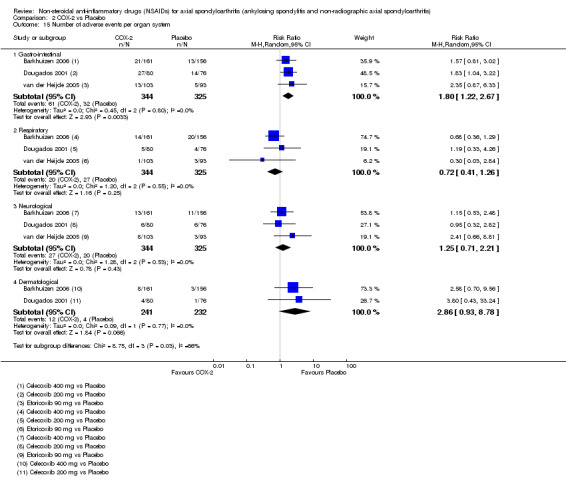

COX‐2 NSAIDS were also more efficacious than placebo at six weeks. High quality evidence (two trials, n = 349) indicates better pain relief with COX‐2 (pain in control group was 64 points and was 21.7 points lower in the COX‐2 group (95% CI ‐35.9 to ‐7.4), NNT 3 (2 to 24)); moderate quality evidence (one trial, n = 193) indicates improved disease activity with COX‐2 (BASDAI in control groups was 54.7 points and was 22 points lower in the COX‐2 group (95% CI ‐27.4 to ‐16.6), NNT 2 (1 to 3)); and high quality evidence (two trials, n = 349) showed improved function with COX‐2 (BASFI in control group was 50.0 points and was 13.4 points lower in the COX‐2 group (95% CI ‐17.4 to ‐9.5), NNT 3 (2 to 4)). Low and moderate quality evidence (three trials, n = 669) (downgraded due to potential imprecision and heterogeneity) indicates that withdrawals due to AEs and number of serious AEs did not differ significantly between placebo (11/1000 and 2/1000) and COX‐2 (24/1000 and 2/1000) groups after 12 weeks (RR 2.14, 95% CI 0.36 to 12.56; and RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.14 to 6.21, respectively). BASMI and radiographic progression were not reported.

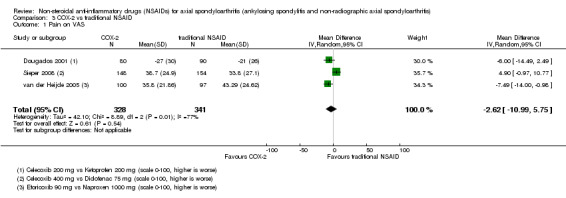

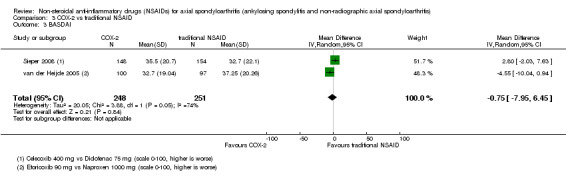

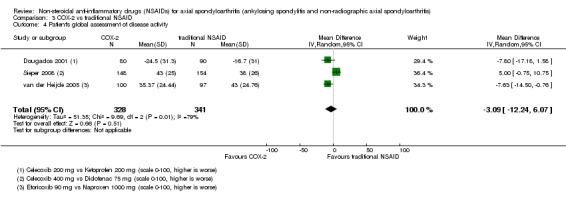

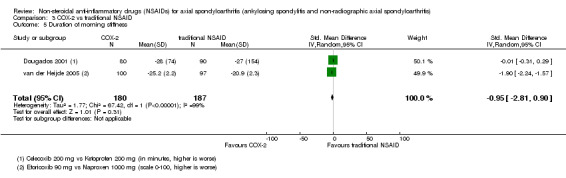

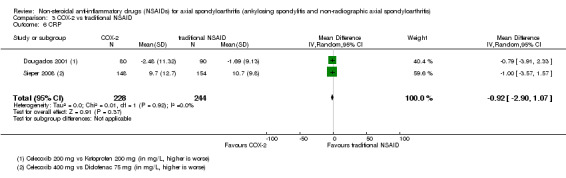

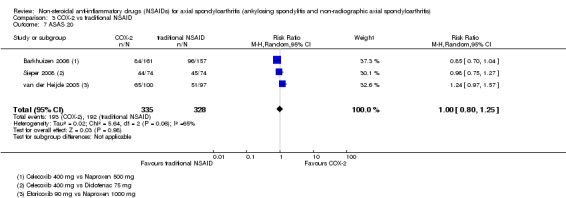

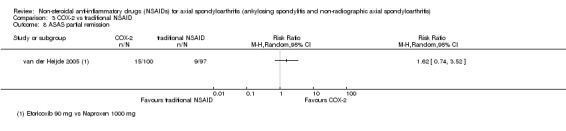

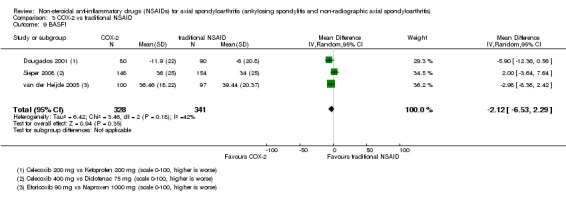

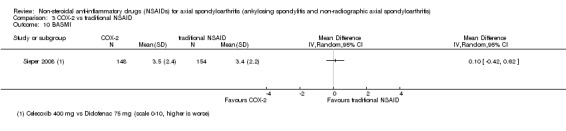

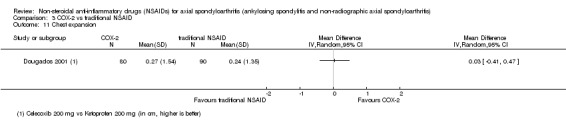

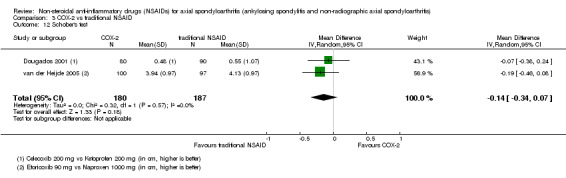

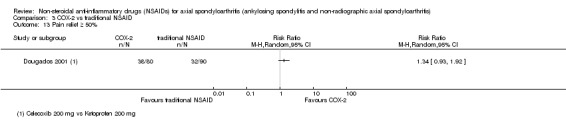

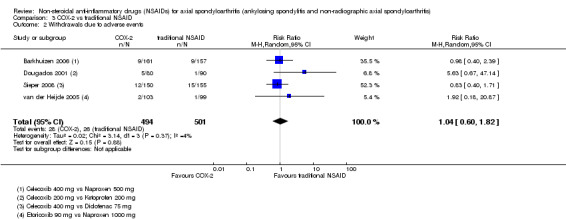

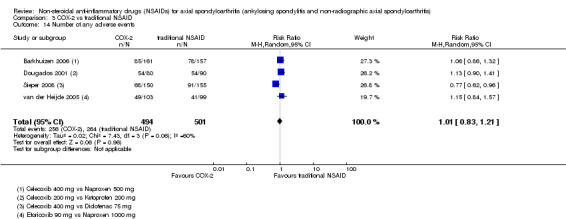

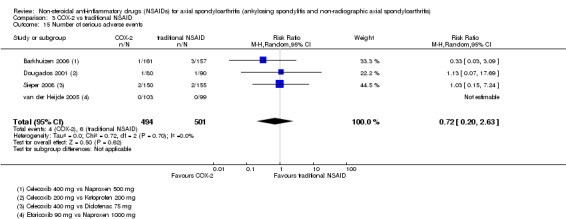

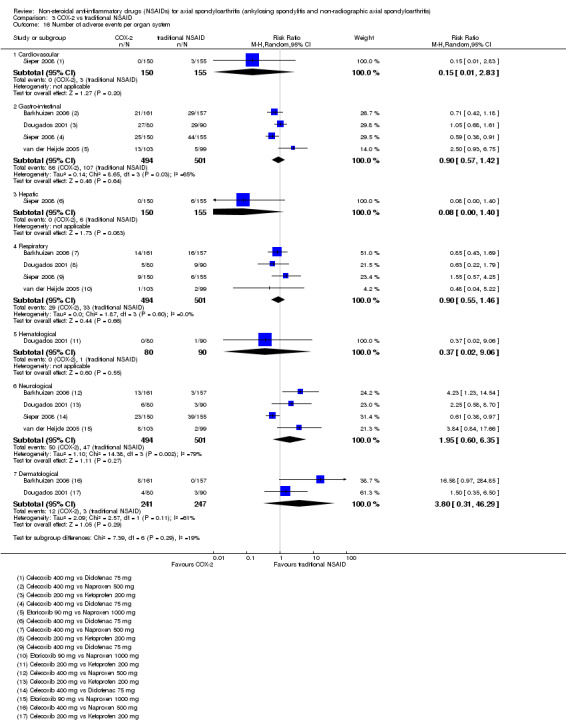

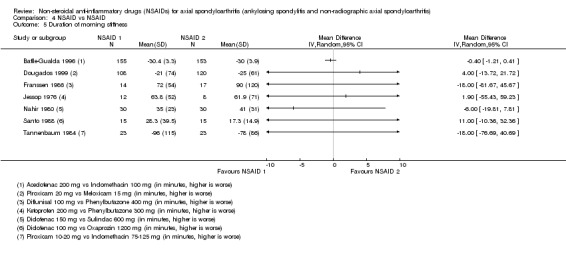

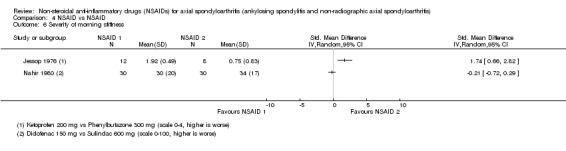

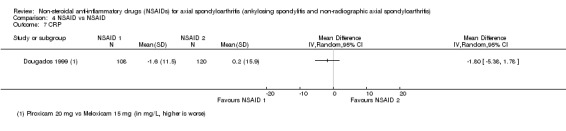

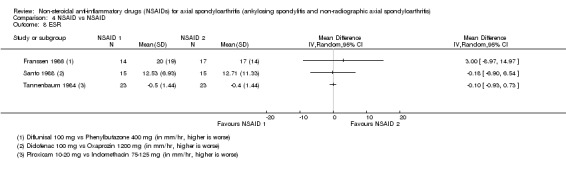

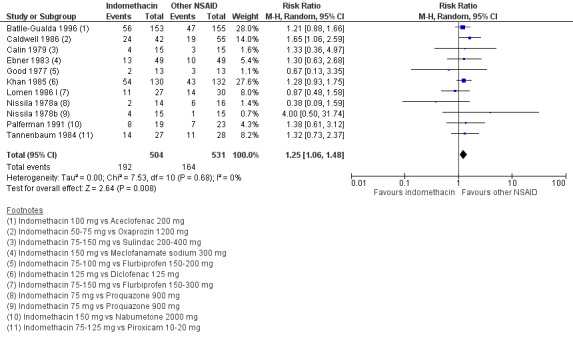

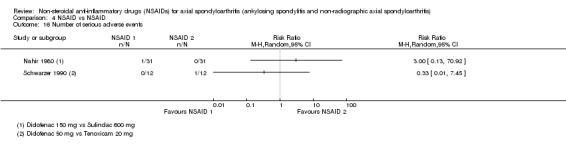

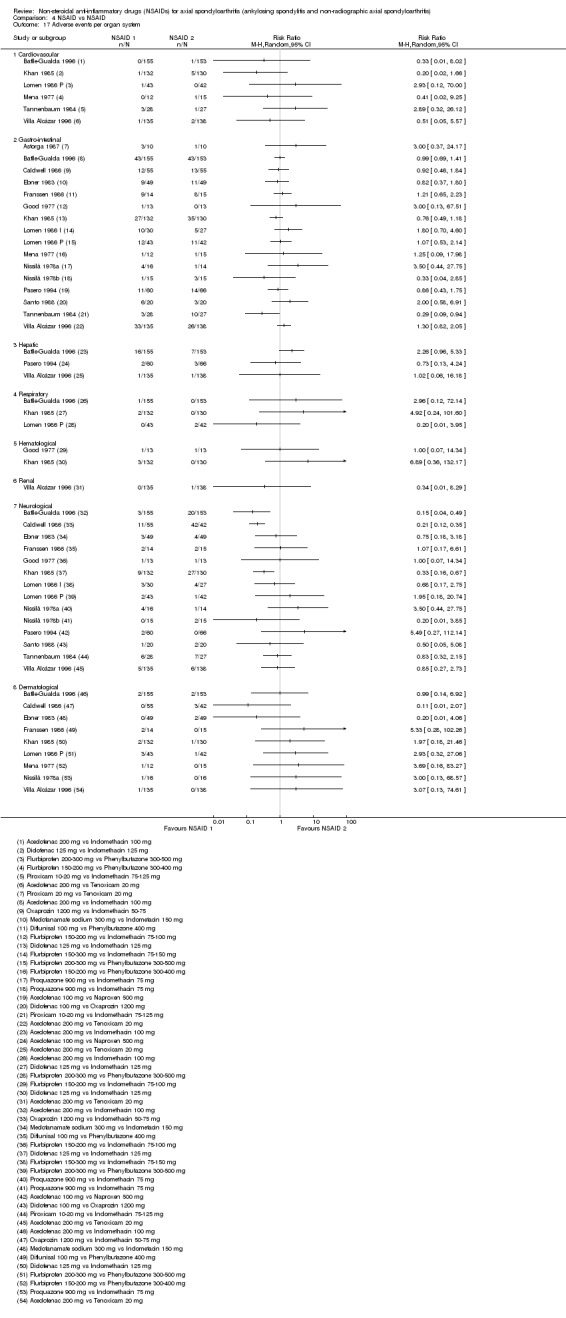

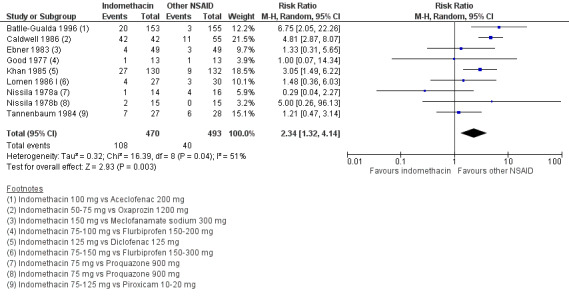

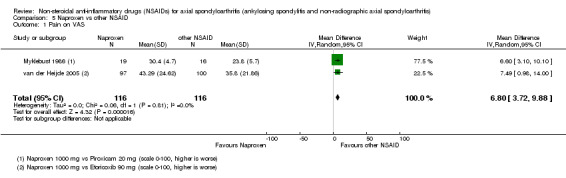

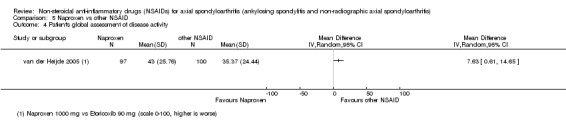

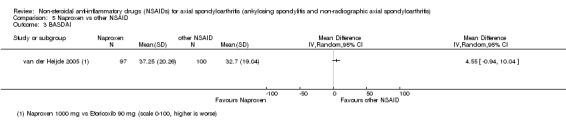

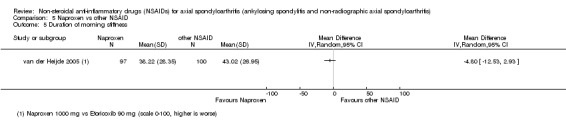

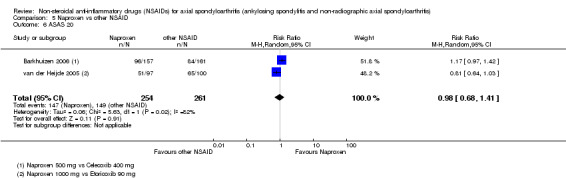

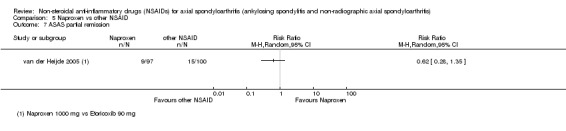

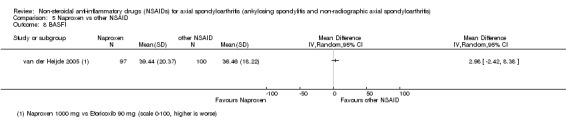

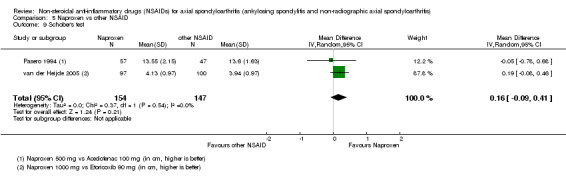

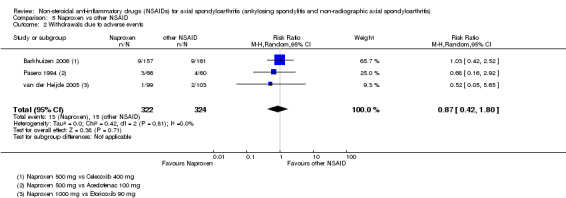

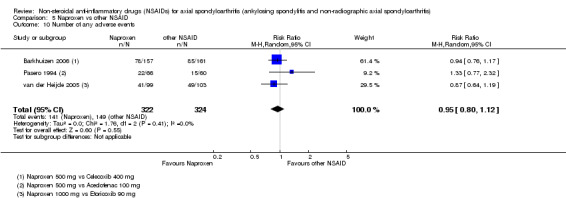

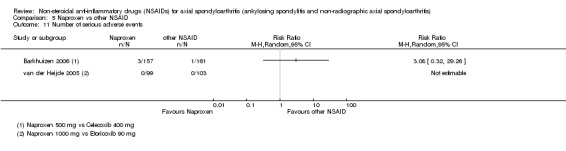

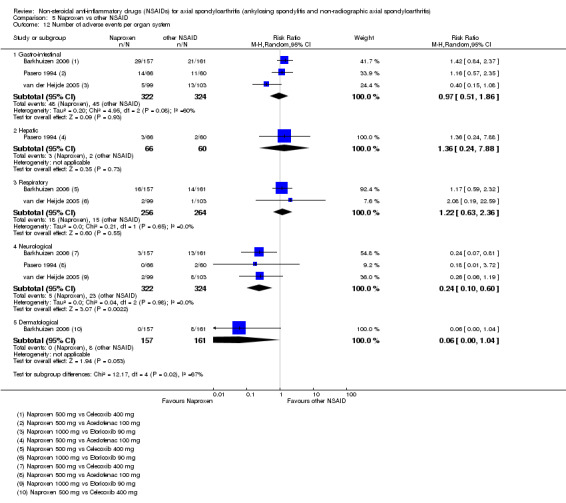

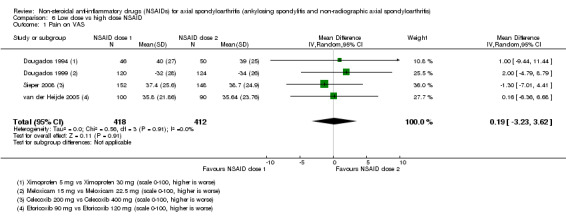

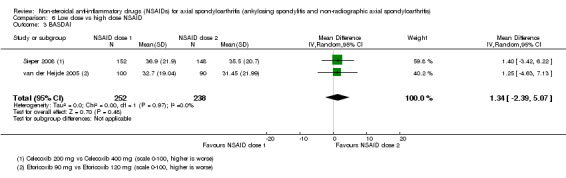

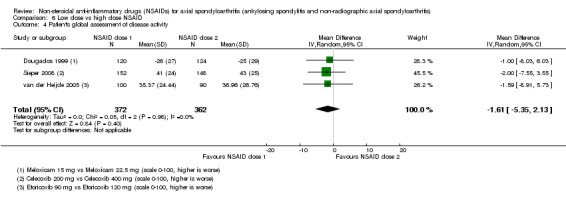

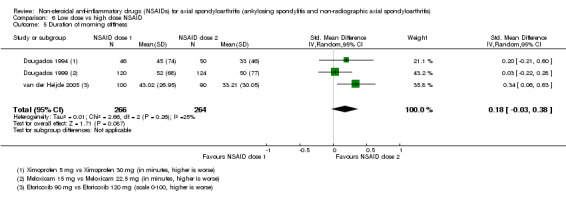

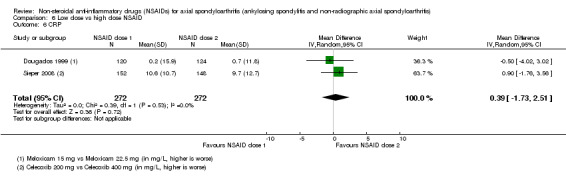

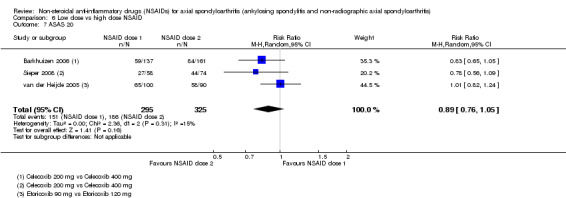

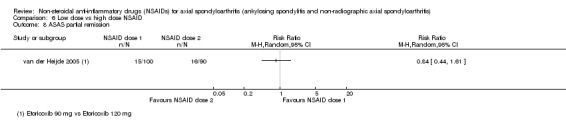

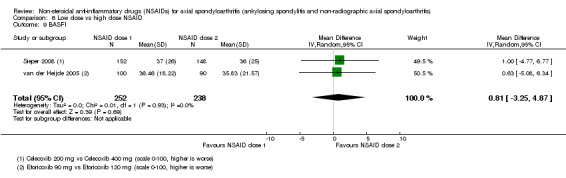

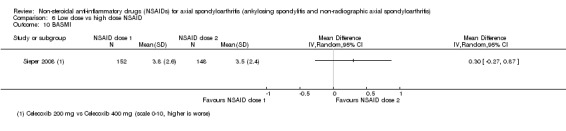

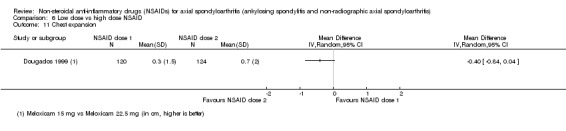

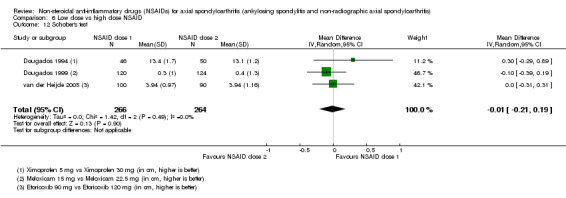

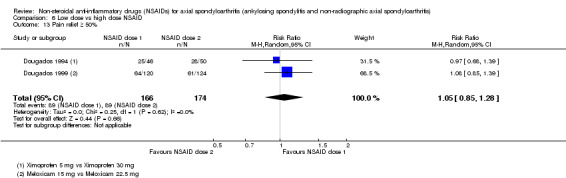

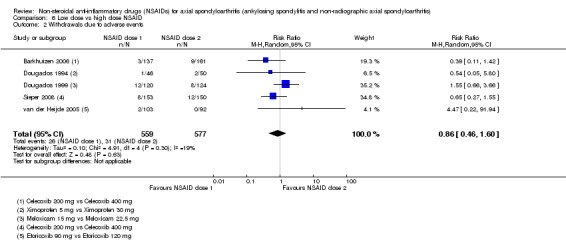

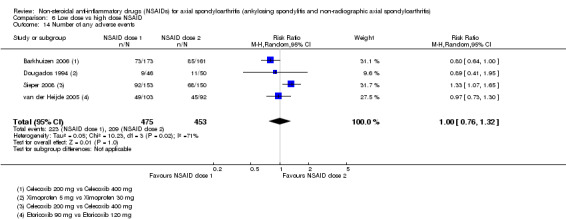

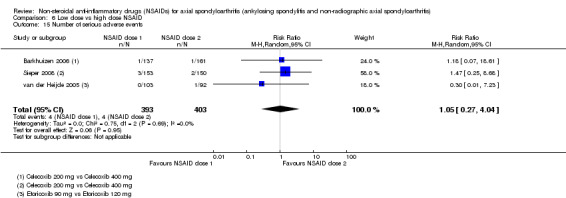

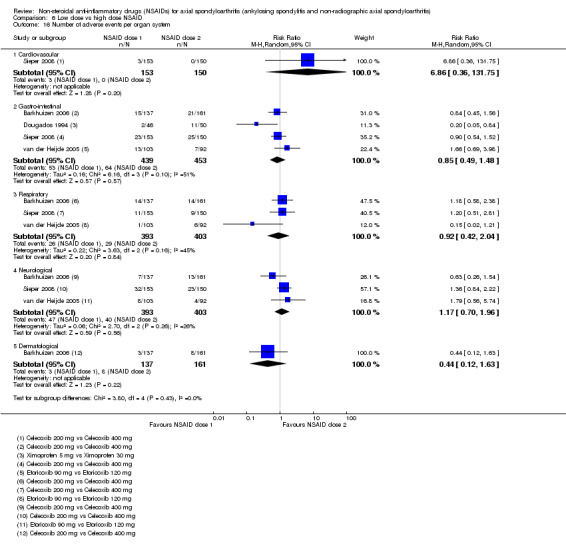

There were no significant differences in benefits (pain on VAS: MD ‐2.62, 95% CI ‐10.99 to 5.75; three trials, n = 669) or harms (withdrawals due to AEs: RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.82; four trials, n = 995) between NSAID classes. While indomethacin use resulted in significantly more AEs (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.48; 11 studies, n = 1135), and neurological AEs (RR 2.34, 95% CI 1.32 to 4.14; nine trials, n = 963) than other NSAIDs, these findings were not robust to sensitivity analyses. We found no important differences in harms between naproxen and other NSAIDs (three trials, n = 646), although other NSAIDs appeared more effective for relieving pain (MD 6.80, 95% CI 3.72 to 9.88; two trials, n = 232). We found no clear dose‐response effect on benefits or harms (five studies, n = 1136). Single studies suggest NSAIDs may be effective in retarding radiographic progression, especially in certain subgroups of patients, e.g. patients with high CRP, and that this may be best achieved by continuous rather than on‐demand use of NSAIDs.

Authors' conclusions

High to moderate quality evidence indicates that both traditional and COX‐2 NSAIDs are efficacious for treating axSpA, and moderate to low quality evidence indicates harms may not differ from placebo in the short term. Various NSAIDs are equally effective. Continuous NSAID use may reduce radiographic spinal progression, but this requires confirmation.

Plain language summary

Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA)

In this Cochrane review of the effect of NSAIDs for people with axSpA (including ankylosing spondylitis and non‐radiographic (nr‐)axSpA), we included 39 studies with 4356 people (search up to 18 June 2014). One study looked at people with nr‐axSpA.

In people with axSpA:

Traditional and COX‐2 NSAIDs improve pain, disease activity and functioning (high quality evidence) and probably do not result in more withdrawals due to adverse events or serious adverse events compared with placebo in the short term (moderate quality evidence, as some outcomes suffered potential imprecision). We often do not have precise information about side effects, particularly for rare but serious side effects. Possible side effects may include gastrointestinal complaints. Rare complications may include gastrointestinal bleeding or problems with heart or blood vessels.

What is axSpA and what are NSAIDs?

AxSpA is a form of arthritis involving the joints of the pelvis or spine or both. It causes pain and stiffness in those regions and can result in deformities of the spine and poor functioning.

NSAIDs are commonly used to reduce pain and inflammation and are considered first‐line treatment for people with axSpA. COX‐2 NSAIDs are a subgroup of NSAIDs that potentially lead to less gastrointestinal complaints than traditional NSAIDs, although there is evidence that they may lead to other complications, like a higher risk of cardiovascular events.

What happens to people with axSpA taking NSAIDs after six weeks:

People who used a traditional NSAID rated their pain to be 16.5 points lower on a scale of 0 to 100 (lower score means less pain) (17% absolute improvement).

‐ People using a traditional NSAID rated their pain to be 44 points; people using placebo 60.5 points.

People who used a traditional NSAID rated their disease activity to be 17.5 points lower on a scale of 0 to 100 (lower score means less disease activity) (18% absolute improvement).

‐ People using a traditional NSAID rated their disease activity to be 37.2 points; people using placebo 54.7 points.

People who used a traditional NSAID rated their functioning to be 9.1 points lower on a scale of 0 to 100 (lower score means better functioning) (9% absolute improvement).

‐ People using a traditional NSAID rated their functioning to be 40.9 points; people using placebo 50.0 points.

Thirteen people less out of 1,000 stopped taking a traditional NSAID before the end of the study because of side effects (0% absolute difference).

‐ 39 people out of 1,000 receiving a traditional NSAID stopped, compared to 52 out of 1,000 receiving placebo.

One more person out of 1,000 had a serious adverse event while taking a traditional NSAID during the study (0% absolute difference).

‐ 3 people out of 1,000 receiving a traditional NSAID had a serious adverse event during the study, compared to 2 out of 1,000 receiving placebo.

People who used a COX‐2 NSAID rated their pain to be 21.7 points lower on a scale of 0 to 100 (22% absolute improvement).

‐ People using a COX‐2 NSAID rated their pain to be 42.3 points; people using placebo 64 points.

People who used a COX‐2 NSAID rated their disease activity to be 22 points lower on a scale of 0 to 100 (22% absolute improvement).

‐ People using a COX‐2 NSAID rated their disease activity to be 32.7 points; people using placebo 54.7 points.

People who used a selective COX‐2 NSAID rated their functioning to be 13.4 points lower on a scale of 0 to 100 (13% absolute improvement).

‐ People using a COX‐2 NSAID rated their functioning to be 36.6 points; people using placebo 50.0 points.

Thirteen people more out of 1,000 stopped taking a COX‐2 NSAID before the end of the study because of side effects (2% absolute difference).

‐ 24 people out of 1,000 receiving a COX‐2 NSAID stopped, compared to 11 out of 1,000 receiving placebo.

The same number of people had a serious adverse event while taking a COX‐2 NSAID or placebo during the study (0% absolute difference).

‐ 2 people out of 1,000 receiving a COX‐2 NSAID had a serious adverse event during the study, compared to 2 out of 1,000 receiving placebo.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) is an umbrella term that comprises ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriatic arthritis, arthritis/spondylitis with inflammatory bowel disease, and reactive arthritis (Amor 1990; Dougados 1991; van der Linden 1984). Patients with typical features of SpA that do not fulfil the criteria for one of these subgroups have also been incorporated in the SpA concept as undifferentiated SpA (Khan 1985; Khan 1990). Patients with SpA can also be distinguished according to their clinical presentation as patients with either predominantly peripheral (including peripheral arthritis, enthesitis and dactylitis) or axial (inflammation of the sacroiliac joints or the spine, or both) SpA (axSpa), with some overlap between these subtypes.

Patients with axSpA constitute a partly heterogeneous group of patients with specific clinical manifestations, such as spinal inflammation (Braun 2007). Sacroiliac joint involvement is considered the hallmark of the disease and structural consequences of sacroiliitis, visible on radiographs (using the modified New York criteria), are required for the classification of AS, a major subgroup of axSpA (van der Linden 1984). However, there is evidence from several studies that it often takes years from the onset of back pain until definite sacroiliitis on plain radiographs is detectable (Mau 1988; Oostveen 1999; Said‐Nahal 2000; Sampaio‐Barros 2001). This causes a diagnostic delay, on average six to eight years, as sacroiliitis on radiographs is a requirement for classification according to the modified New York criteria (Dougados 1995; Mau 1988; Rudwaleit 2005). Consequently, while these criteria perform well in patients with established disease, they lack sensitivity in early disease. The absence of radiographic sacroiliitis during the early stage of disease does not necessarily imply that inflammation is absent in the sacroiliac joints, as inflammation has been demonstrated on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in people with normal plain radiographs (Rudwaleit 2009a). Thus, the presence and absence of radiographic sacroiliitis in patients with SpA may represent different stages of one disease continuum (Rudwaleit 2005). Furthermore, the presence or absence of radiographic sacroiliitis does not affect the burden of disease (Rudwaleit 2004).

Classification criteria for axSpA have recently been developed by the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) (Rudwaleit 2009a; Rudwaleit 2009b). According to these criteria, a patient with chronic back pain (≥ three months) and age at onset of < 45 years can be classified as having axSpA in the presence of sacroiliitis (either definite radiographic sacroiliitis or active inflammation of sacroiliac joints on MRI, which is highly suggestive of sacroiliitis associated with SpA) plus at least one typical SpA feature, or in the presence of HLA‐B27 plus at least two other SpA features (Rudwaleit 2009b). Using this set of criteria, patients can be classified as not having established radiographic changes in the sacroiliac joint, i.e. non‐radiographic axial SpA (nr‐axSpA), or as having developed radiographic changes in the sacroiliac joint, i.e. radiographic axSpA or AS. In Western European countries axSpA prevalence is between 0.3% and 2.5%. The prevalence rate of AS in Western countries is up to 0.53% (Stolwijk 2012).

Description of the intervention

Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including traditional NSAIDs and selective cyclo‐oxygenase (COX) inhibitors, are well‐established drugs commonly used to treat people with inflammatory conditions. The primary goal in the treatment of patients with AS is to maximize long‐term health‐related quality of life through control of symptoms and inflammation, to prevent progressive, structural damage, and to preserve or normalize function and social participation (Braun 2011). NSAIDs are recommended as first‐line drug treatment for patients with axSpA with pain and stiffness (Braun 2011). Current recommendations for the use of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors in patients with axSpA recommend that patients should have had an adequate therapeutic trial of at least two NSAIDs, defined as at least two NSAIDs over a four‐week period in total at maximum recommended or tolerated anti‐inflammatory dose unless contraindicated (van der Heijde 2011). Continuous treatment with NSAIDs is preferred for patients with persistently active, symptomatic disease (Braun 2011).

Nevertheless, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and renal risks should be taken into account when prescribing NSAIDs (Braun 2011). There is overwhelming evidence that these agents can lead to a variety of gastrointestinal toxicities by inhibition of mucosal prostaglandin production (Armstrong 1987; Fries 1991; Gabriel 1991; Griffin 1988; Langman 1994; MacDonald 1997; Stalnikowicz 1993). The increased risk of cardiovascular events was highlighted by the withdrawal of rofecoxib from the market due to findings that it may have increased the risk of myocardial infarction (Bresalier 2005). Several other NSAIDs have also been shown to be associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (Kearney 2006). Recently, a network meta‐analysis on the cardiovascular safety of NSAIDs was published, which concluded that in comparison to placebo all studied NSAIDs posed an increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Trelle 2011). These harmful effects may occur through a variety of mechanisms, including an increase in blood pressure and peripheral oedema. NSAIDs have also consistently been associated with the development of congestive heart failure (Feenstra 2002). Furthermore, evidence exists that NSAIDs may produce either reversible or permanent renal toxicity and a variety of negative effects on electrolyte and water homeostasis (Murray 1993).

How the intervention might work

The primary site of action of NSAIDs is the enzyme COX that converts arachidonic acid into prostaglandins, which ‐ amongst other functions ‐ mediate inflammation and pain. Two forms of COX have been described, COX‐1 and COX‐2 (Vane 1998). COX‐1 is normally present in high concentration in platelets, vascular endothelial cells, stomach and kidney collecting tubules. It is responsible for the production of prostaglandins which are essential for maintenance of normal endocrine and renal function, gastric mucosal integrity and haemostasis. COX‐2 was first thought to be virtually undetectable in most tissues under physiological circumstances, and its activity only increased by inflammatory and mitogenic stimuli. However, the conventional distinctions between COX‐1 and COX‐2 (that prostaglandins important in physiological function are produced solely via COX‐1 and those that mediate local inflammation are produced solely via COX‐2) have been challenged by more recent evidence (Bertolini 2002). Most NSAIDs are non‐selective COX inhibitors, which means they inhibit both COX‐1 and COX‐2. A newer class of NSAIDs are the COX inhibitors, which selectively inhibit COX‐2.

It has recently been suggested that NSAIDs may also inhibit structural progression in the spine in patients with AS, especially in the group of patients with an elevated C‐reactive protein (CRP) (Poddubnyy 2012; Wanders 2005). This is in contrast to TNF inhibitors, which have been shown not to inhibit radiographic progression despite their ability to rapidly restore CRP levels and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) to normal (van der Heijde 2008a; van der Heijde 2008b; van der Heijde 2009b). These findings suggest that there are inflammation‐independent mechanisms, sensitive to the effects of NSAIDs, which contribute to the process of syndesmophyte formation, the hallmark of structural progression in AS. A possible biological explanation for this is that COX‐2 is relevant in bone formation. This was concluded by a study in which both COX‐2 knock‐out mice and mice treated with COX‐2 inhibiting drugs showed reduced callus formation after a fracture, which seems to be attributable to suppression of osteoblasts (Zhang 2002). Furthermore, in an immuno‐histochemical analysis comparing synovial tissue samples obtained from patients with different forms of inflammatory arthritis (AS, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis), COX‐2 expression appeared to be highest in the samples from patients with AS (Siegle 1998). So if an upregulated level of COX‐2 in AS is indeed responsible for increased osteoblastic bone formation (in the form of syndesmophytes), inhibition of COX‐2 with NSAIDs might be a rational approach to prevent the occurrence of syndesmophytes. In contrast to the effects of NSAIDs seen on bone formation on radiographs, a six‐week open‐label study in patients with AS treated with etoricoxib found only a small effect on MRI‐detected lesions. However, other studies have consistently shown a substantial improvement of MRI lesions after anti‐TNF therapy (Braun 2006; Jarrett 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

There are several reasons why it is important to do this Cochrane review. The review will synthesise the existing data on the benefits and harms of NSAIDs in controlling disease activity, symptoms and radiographic progression in axSpA, and, for the first time, will also include nr‐axSpA. Although NSAIDs are recommended as first‐line therapy for axSpA, no systematic review has yet been undertaken on their effect considering outcomes relevant for clinical practice as recommended by ASAS (Sieper 2009). Although NSAIDs are recommended as first‐line therapy, they may have important side effects, so it is crucial to know whether the benefits offset the risks, especially because the therapy is often given for extended periods of time. Finally, this will be the first systematic review to examine the effect of NSAIDs on radiographic damage, an outcome that has been shown to be associated with impaired spinal mobility and function (Machado 2010; Machado 2011a). This review should provide clinicians with information to guide their decisions about NSAID therapy for patients with axSpA.

Objectives

To assess the benefit and harm of NSAIDs in controlling disease activity, symptoms and radiographic progression in patients with axSpA.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (i.e. where allocation was not truly random). We included only trials that were published as full articles or were available as a full trial report. Extension phases and post‐hoc analyses of RCTs were also included to enable a comprehensive overview of the benefits and harms of NSAIDs.

As radiographic progression, as well as long term harmful effects, were unlikely to be assessed in short‐term RCTs of NSAIDs, we also included observational cohort studies to investigate the effect of NSAIDs on these outcomes. We assessed all included studies in an assessment of adverse events/harms of therapy with NSAIDs. In addition, cohort studies assessing the effect of NSAIDs on radiographic progression had to have a minimum duration of six months in order to be included. There were no restrictions on language of the paper.

Types of participants

We selected studies that included adults aged ≥ 18 years with a clinical diagnosis of axSpA, or patients fulfilling modified New York criteria or ASAS axial SpA criteria, including nr‐axSpA and AS. We included both disease subgroups. Studies containing patients with other diagnoses (e.g. trials that included participants based upon fulfilment of the European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group (ESSG) criteria or the Amor criteria (Amor 1990)) were only eligible if they presented results from patients with axSpA separately (Dougados 1991).

Types of interventions

We included studies that evaluated NSAIDs and all possible variations (dosage, intensity, mode of delivery, duration of delivery, timing of delivery, traditional and COX‐2 selective).

Comparators were:

Placebo;

No therapy;

Another NSAID;

Other pharmacological therapy;

Non‐pharmacological therapy;

Combination therapy;

Different doses, modes of delivery, frequency and duration.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Benefits

Pain (as assessed by the mean change in pain score on a visual analogue scale (VAS) or numerical rating scale (NRS)); back pain was used but if not present in a study, overall pain was used;

-

Harms

Total number of withdrawals due to adverse events;

Disease activity as assessed by the mean improvement in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) (Garrett 1994);

Physical function as assessed by the mean improvement in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) (Calin 1994);

Spinal mobility as assessed by the mean improvement in the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) (Jenkinson 1994);

Radiographic progression as assessed by the mean change in the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score (mSASSS) (Wanders 2004);

Number of serious adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

-

Disease activity

Mean improvement in Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (ASDAS) (van der Heijde 2009a)

Mean improvement in patient's global assessment of disease activity

Mean improvement in fatigue (BASDAI question) (Garrett 1994)

Mean improvement in peripheral joint pain (BASDAI question) (Garrett 1994)

Mean improvement in tenderness of the joints (BASDAI question) (Garrett 1994)

Mean improvement in duration of morning stiffness (BASDAI question) (Garrett 1994)

Mean improvement in severity of morning stiffness (BASDAI question) (Garrett 1994)

Mean improvement in CRP

Mean improvement in ESR

Proportion of patients achieving ASDAS clinically important improvement (improvement ≥ 1.1 in ASDAS) (Machado 2011b)

Proportion of patients achieving ASDAS major improvement (improvement ≥ 2.0 in ASDAS) (Machado 2011b)

Proportion of patients achieving ASDAS inactive disease (ASDAS < 1.3) (Machado 2011b)

Proportion of patients achieving BASDAI 50 (improvement ≥ in BASDAI);

-

Fulfilment of response criteria

Proportion of responders according to ASAS20 (20% improvement in disease activity according to criteria of ASAS) (Anderson 2001)

Proportion of responders according to ASAS40 (40% improvement in disease activity according to criteria of ASAS) (Brandt 2004)

Proportion of responders according to ASAS 5/6 (20% improvement in disease activity according to criteria of ASAS) (Brandt 2004)

Proportion of patients achieving ASAS partial remission (Brandt 2004);

-

Spinal mobility

Mean improvement in lateral spinal flexion (Sieper 2009)

Mean improvement in chest expansion (Sieper 2009)

Mean improvement in tragus‐to‐wall distance (Sieper 2009)

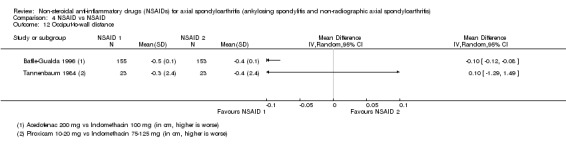

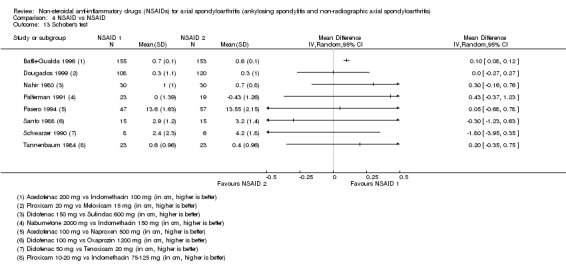

Mean improvement in occiput‐to‐wall distance (Sieper 2009)

Mean improvement in cervical rotation (Sieper 2009)

Mean improvement in intermalleolar distance (Sieper 2009)

Mean improvement in 10 cm modified Schober's test (Sieper 2009);

Pain as assessed by the proportion of patients reporting pain relief of ≥ 50%;

-

Quality of life

Mean improvement in the Short‐Form 36 (SF‐36) (Ware 1992)

Mean improvement in the Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life (ASQoL) score (Doward 2003);

-

Radiographic progression

The proportion of patients showing progression of at least two mSASSS units (Wanders 2004);

-

Adverse events

Number of (all) adverse events

Adverse events broken up by bodily system (e.g. gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, pulmonary).

We extracted all immediate (after up to two weeks of NSAID treatment), intermediate (up to and including six months of NSAID treatment) and longer‐term data (longer than six months of NSAID treatment).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

One review author (LF) searched the following electronic bibliographical databases: MEDLINE (1946 to June 2014), EMBASE (1980 to June 2014), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library (Issue 6, 2014) without language restrictions (Lefebvre 2011). We have provided the complete search strategies for the database searches in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

In order to retrieve additional references, we pursued an additional search for systematic reviews in the Database of Abstracts of Review of Effects (DARE) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database. We also searched Scopus for conference proceedings, as well as two clinical trial registries for ongoing and recently finished studies (ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/) for unpublished studies (Appendix 1). We screened the reference lists from included RCTs and other systematic reviews on the benefits and harms of NSAIDs for axSpA in order to identify all possible studies for this systematic review.

We also searched the websites of the regulatory agencies (e.g. the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) MedWatch (http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/default.htm), the European Medicines Evaluation Agency (http://www.ema.europa.eu), the Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Bulletin (http://www.tga.gov.au/safety/ews‐monitoring.htm), and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency pharmacovigilance and drug safety updates (http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/index.htm) to identify any reported safety concerns.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (FK, LvdB) independently assessed each title and abstract for suitability for inclusion. They decided independently of each other the eligibility of the article according to the pre‐determined selection criteria (Criteria for considering studies for this review). If there was any doubt, we retrieved and assessed the full‐text article. We resolved any disagreements between the review authors about the eligibility of the articles in a consensus meeting. In case of non‐consensus, a third review author (SR) decided if the study was eligible.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (FK, LvdB) independently extracted data regarding study design (including funding source and number of centres), study duration, characteristics of study population, interventions, outcome measures and timing of outcome assessment, co‐interventions, benefits and adverse effect data, and losses to follow‐up by using a standardized data extraction form. We resolved any disagreements in data‐extraction by referring back to the original articles and by establishing consensus thereafter. If necessary, we consulted a third review author (SR).

We extracted the results (i.e. raw data: means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous outcomes and number of events for dichotomous outcomes) for outcomes of interest in order to assess the benefIts and harms. For studies published in languages other than English, German, Portuguese, French, Spanish or Dutch, we consulted a native speaker or translator with content and methodological expertise.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (FK, LvdB) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included RCT (except for one trial that involved FK which was assessed by LvdB and SR) with regard to the following items: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, care provider, and outcome assessor for each outcome measure (Types of outcome measures), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias (including bias associated with cross‐over design of included studies if applicable (e.g. whether there was a carry‐over effect), baseline imbalance, co‐interventions and contamination), conforming to the methods recommended by Cochrane (Higgins 2011a). To determine the risk of bias of a study, for each criterion the presence of sufficient information and the likelihood of potential bias was evaluated. Each criterion is rated as "low risk of bias", "high risk of bias" or "unclear" (either lack of information or uncertainty over the potential for bias). In a consensus meeting we discussed and resolved any disagreements between the review authors. If consensus could not be reached, a third review author (SR) made the final decision.

Two review authors (FK, LvdB) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included observational study, with regard to the following items: study participation (i.e. representativeness of the study sample), study attrition, prognostic factor measurement, outcome measurement, confounding measurement and account, and analysis, as recommended in Hayden 2006. To determine the risk of bias of a study, for each criterion the presence of sufficient information and the likelihood of potential bias was evaluated. Each criterion is rated as "low risk of bias", "high risk of bias" or "unclear" (either lack of information or uncertainty over the potential for bias). In a consensus meeting, we resolved any disagreements between the review authors. If consensus could not be reached, a third author (SR) made the final decision.

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed the results of the studies using Cochrane's statistical software, Review Manager 2014. We only performed meta‐analysis if the data of the studies were clinically and statistically sufficiently homogeneous. We expressed the results as risk ratios (RRs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous data. A RR greater than 1.0 indicates a beneficial effect of NSAIDs (Deeks 2011).

For continuous data, we analysed results as mean differences (MDs) between the intervention and comparator group, with corresponding 95% CIs. The MD between treated group and control group was weighted by the inverse of the variance in the pooled treatment estimate. However, when different scales were used to measure the same conceptual outcome (e.g. functional status or pain), we calculated the standardized mean differences (SMDs) instead with corresponding 95% CIs. SMDs are calculated by dividing the MD by the SD, resulting in a unit‐less measure of treatment effect (Deeks 2011). SMD greater than zero indicate a beneficial effect in favour of NSAIDs for axSpA and we computed 95% CIs for the SMD. We interpreted the SMD as described by Higgins 2011b; i.e. a SMD of 0.2 was considered to indicate a small beneficial effect, 0.5 a medium effect, and 0.8 a large effect of NSAIDs for axSpA. SMDs were considered to indicate a clinically relevant effect if the SMD was > 0.5. Upon completion of the analysis, we translated the SMD back into a MD, on a scale of 0 to 10, which can be better appraised by clinicians.

For studies containing more than two intervention groups, making multiple pair‐wise comparisons between all possible pairs of intervention groups, we included the same group of participants only once in the meta‐analysis, or we split the group with the 'shared' intervention into two equally large groups to include two comparisons if deemed necessary. Whenever we had to decide between multiple dosages of a NSAID for studies containing more than two intervention groups, we used the proposed equivalent dose of 150 mg Diclofenac based on voting during the ASAS annual meeting (Dougados 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

Unit of analysis problems were not expected in this review. In the event that we identified crossover trials in which the reporting of continuous outcome data precluded paired analysis, we did not include these data in a meta‐analysis in order to avoid unit‐of‐analysis error. Where carry‐over effects were thought to exist, and where sufficient data existed, we included only data from the first period in the analysis (Higgins 2011b). Also, in studies of long duration, results may be presented for several periods of follow‐up. In that case we did not combine results from more than one time point for each study in a meta‐analysis to avoid unit‐of‐analysis error.

Dealing with missing data

Where important data are missing or incomplete, we planned to seek further information from the study authors.

In case individuals were missing from the reported results, we assumed the missing values to have a poor outcome. For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. number of withdrawals due to adverse events), we calculated the withdrawal rate using the number of patients randomised in the group as the denominator (worst case scenario).

For continuous outcomes (e.g. mean change in pain score), we calculated the MD or SMD based on the number of patients analysed at that time point. If the number of patients analysed was not presented for each time point, we used the number of randomised patients in each group at baseline.

Where possible, we computed missing SDs from other statistics such as standard errors, CIs or P values, according to the methods recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011c). If SDs could not be calculated, they were imputed (e.g. from other studies in the meta‐analysis) (Higgins 2011b). If studies with final measurement data and change scores had to be combined using a SMD (e.g. because the studies used different scales), we calculated the final measurement data from the studies presenting change scores and imputed the SD for these final measurement data from the baseline SD from the same study.

Where data were presented graphically only, we extracted data from the graph when possible.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In this Cochrane review, we explored step‐by‐step the clinical and statistical heterogeneity between the studies. Firstly, we assessed studies for clinical homogeneity with respect to intervention groups, control groups, timing of outcome assessment and outcome measures. For any study judged as clinically homogeneous, we assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic (Deeks 2011), using the following as a rough guide for interpretation:

0 to 40%: might not be important;

30 to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50 to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75 to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

In cases of considerable heterogeneity, we explored the data further, including subgroup analyses, in an attempt to explain the heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In order to determine if reporting bias was present, we determined whether the protocol of the RCT was published before recruitment of patients of the study was started. For studies published after 1 July 2005, we screened the WHO ICTRP search portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/). We evaluated whether selective reporting of outcomes was present (outcome reporting bias).

We compared the fixed‐effect model against the random‐effects model to assess the possible presence of small sample bias in the published literature (i.e. in which the intervention effect is more beneficial in smaller studies). In the presence of small sample bias, the random‐effects estimate of the intervention is more beneficial than the fixed‐effect estimate (Sterne 2011).

We further explored the potential for reporting bias by funnel plots if ≥ 10 studies were included.

We planned to add the unpublished trials in the Studies awaiting classification section, but we encountered none through our search strategy.

Data synthesis

We pooled the results of clinically and statistically homogeneous studies using the random‐effects model. We performed data analyses using Review Manager 2014 and produced forest plots for all analyses.

The main comparison of this review was NSAIDs versus placebo. However, many trials included both traditional and COX‐2 NSAIDs so we decided to assess the two NSAID classes separately.

We also considered the following comparisons in this review:

COX‐2 inhibitors versus traditional NSAIDs;

NSAIDs versus NSAIDs;

Naproxen versus other NSAIDs;

Low versus high dose NSAIDs; and

Continuous versus on‐demand NSAID use.

We included the comparison 'naproxen vs other NSAIDs' as a recent meta‐analysis of vascular and upper gastro‐intestinal effects of NSAIDs in various patients (prescribed mostly for rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis, but also for prevention of colorectal adenomata or of Alzheimer's disease) found that naproxen was associated with less vascular (but increased upper gastro‐intestinal) risk than other NSAIDs (Bhala 2013).

'Summary of findings' table

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables, which includes an overall grading of the evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, and a summary of the available data on the main outcomes as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011). We included the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' table:

Pain outcomes (mean change in pain score on a VAS or NRS);

Total number of withdrawals due to adverse events;

Mean improvement in BASDAI;

Mean improvement in BASFI;

Mean improvement in BASMI;

Radiographic progression;

Number of serious adverse events.

We illustrated data from the main comparison (NSAIDs vs placebo) in the main 'Summary of findings' table. Overall outcome data presented in the 'Summary of findings' tables were based on the longest time points measured in each study.

Grading of the evidence involved consideration of within‐study risk of bias, directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias. However, other factors could affect the quality of evidence (e.g. it could be increased by a large magnitude of effect, plausible confounding and dose‐response gradients). Using this system, we graded the quality of the body of evidence as either high, moderate, low or very low (Atkins 2004).

In addition to the absolute and relative magnitude of effect provided in the 'Summary of findings' table, for dichotomous outcomes we calculated the number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) or the number needed to treat to harm (NNTH) where appropriate from the control group event rate (unless the population event rate is known) and the RR using the Visual Rx calculator (Visual Rx 2008). We calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) for continuous outcomes using the Well's calculator software, which is based on the theory of Norman 2001 of determining the NNT based on achieving the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for a particular outcome.

In the 'Summary of findings' table, we provided the absolute percent difference, the relative percent change from baseline, and the NNT (the NNT was provided only when the outcome showed a statistically significant difference).

For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the absolute risk difference using the risk difference statistic in Review Manager 2014 and expressed the result as a percentage. For continuous outcomes, we calculated the absolute benefit as the improvement in the intervention group minus the improvement in the control group, in the original units.

We calculated the relative percent change for dichotomous data as the RR ‐ 1 and expressed it as a percentage. For continuous outcomes, the relative difference in the change from baseline was calculated as the absolute benefit divided by the baseline mean of the control group.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where sufficient data was available, we conducted the following subgroup analyses to examine the influence of:

Gender (male vs female) on the effect of NSAIDs on all the outcomes;

Baseline radiographic damage (present vs absent) on the effect of NSAIDs on radiographic damage;

Baseline CRP (normal vs abnormal) on the effect of NSAIDs on radiographic damage;

Radiographic vs nr‐axSpA on the effect of NSAIDs on all the outcomes.

We selected these subgroups based on some evidence that these factors have prognostic value. Therefore, we wanted to assess whether this held true in this Cochrane review.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to explore effect size differences and the robustness of conclusions. Where sufficient studies existed, we planned sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of any bias attributable to inadequate or unclear treatment allocation, blinding of patient/assessor and loss to follow‐up compared to studies without these study limitations ("low risk" vs "high risk" or "unclear").

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies and Table 3 (Characteristics of included cohort studies) and Table 4 (Characteristics of included post‐hoc studies).

1. Characteristics of included cohort studies.

| Boersma 1976 | |

| Methods |

Design: Retrospective cohort study Number of centres: 1 Time point of assessments: Whenever radiological examination of the lumbar vertebral column was available. Length of follow‐up: Variable (up to 20 years) |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: Definite AS, with a radiological examination available. Exclusion criteria: NA Classification: New York criteria Continuous Phenylbutazone: Number of participants: 18 Number of completers: 18 Age: NA Male (%): NA Symptom duration: NA Disease duration: NA HLA‐B27 positive (%): NA Not continuous Phenylbutazone: Number of participants: 12 Number of completers: 12 Age: NA Male (%): NA Symptom duration: NA Disease duration: NA HLA‐B27 positive (%): NA No medication: Number of participants: 10 Number of completers: 10 Age: NA Male (%): NA Symptom duration: NA Disease duration: NA HLA‐B27 positive (%): NA |

| Interventions | Continuous Phenylbutazone vs not continuous Phenylbutazone vs no medication |

| Outcomes | Extracted outcomes: Unable to extract outcomes due to the method of presentation (individual data in graphs). |

| Notes | Funding source: Not reported |

| Risk of bias |

|

| Poddubnyy 2012 | |

| Methods |

Design: Post‐hoc analysis of prospective cohort study Number of centres: 13 Time point of assessments: BL, 2 years Length of follow‐up: 2 years |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria (participants with AS): 1. Definite clinical diagnosis of axial SpA according to the local rheumatologist; 2. Duration of symptoms ≤ 10 years at the time of inclusion. Exclusion criteria (participants with AS): NA Classification (participants with AS): modified New York criteria Inclusion criteria (participants with nr‐axSpA): 1. Fulfilling ESSG criteria with minor modifications; 2. Duration of symptoms of ≤ 5 years. Exclusion criteria (participants with nr‐axSpA): NA Classification (participants with nr‐axSpA): ESSG criteria AS, low NSAIDs intake (NSAIDs index < 50): Number of participants: 64 Number of completers: 64 Age (mean (SD)): 36.2 (12.4) Male (%): 67 Symptom duration (mean (SD)): 5.0 (2.9) years Disease duration: NA HLA‐B27 positive (%): 86 AS, high NSAIDs intake (NSAIDs index ≥ 50): Number of participants: 24 Number of completers: 24 Age (mean (SD)): 38.7 (9.8) Male (%): 67 Symptom duration (mean (SD)): 5.5 (2.7) years Disease duration: NA HLA‐B27 positive (%): 79 nr‐axSpA, low NSAIDs intake (NSAIDs index < 50): Number of participants: 57 Number of completers: 57 Age (mean (SD)): 38.6 (9.3) Male (%): 32 Symptom duration (mean (SD)): 3.0 (2.2) years Disease duration: NA HLA‐B27 positive (%): 71 nr‐axSpA, high NSAIDs intake (NSAIDs index ≥50): Number of participants: 19 Number of completers: 19 Age (mean (SD)): 43.0 (9.6) Male (%): 32 Symptom duration (mean (SD)): 3.7 (2.1) years Disease duration: NA HLA‐B27 positive (%): 68 |

| Interventions | Low NSAIDs intake (NSAIDs index < 50) vs high NSAIDs intake (NSAIDs index ≥ 50) Co‐medication: No anti‐TNF therapy was allowed. |

| Outcomes | Extracted outcomes: mSASSS |

| Notes | Funding source: As part of the German competence network in rheumatology (Kompetenznetz Rheuma), GESPIC has been financially supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung – BMBF), grant number: FKZ 01G19946. As funding by BMBF was reduced according to schedule in 2005 and stopped in 2007, complementary financial support has been obtained also from Abbott, Amgen, Centocor, Schering‐Plough and Wyeth. Since 2010, additional support has being obtained also from ANCYLOSS and ArthroMark projects funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. |

| Risk of bias |

|

2. Characteristics of included post‐hoc studies.

| Gossec 2005 | ||||||||||

|

Original study: Post hoc analysis of van der Heijde 2005. Comparison: Active drug (etoricoxib 90, etoricoxib 120 and naproxen 500) vs placebo. Analysis: Subgroup analysis in patients with and without chronic peripheral arthritis (defined as painful or swollen peripheral arthritis of > 4 weeks' duration, or a history of peripheral arthritis (anamnestic and based on medical chart), provided that the spine was the primary source of pain). Outcomes: BASDAI question on spine pain, patient global assessment of disease activity (BASFI), BASDAI question on peripheral pain, BASDAI questions on stiffness, BASDAI question on enthesopathy, ASAS 20 responders. | ||||||||||

| Baseline characteristics | ||||||||||

| Characteristic | Peripheral arthritis ‐ Yes | Peripheral arthritis ‐ No | ||||||||

| Number of participants | 115 | 186 | ||||||||

| Age (mean (SD)) | 43.8 (13.9) | 43.5 (10.4) | ||||||||

| "The two groups appeared to be well balanced, except for a higher percentage of concomitant DMARD and prior corticosteroid use in the group with peripheral arthritis." | ||||||||||

| Results | ||||||||||

| Outcome | Peripheral arthritis? | Treatment (N) | Baseline (mean (SD)) | Change from BL (mean (95% CI)) | P value | |||||

| Spine pain (VAS, 0 to 100, higher is worse) | Yes Yes No No |

Placebo (37) Active drug (117) Placebo (56) Active drug (175) |

78.7 (17.3) 77.6 (15.4) 76.2 (13.8) 77.7 (14.5) |

‐17.5 (‐24.7 to ‐10.3) ‐34.5 (‐38.6 to ‐30.4)* ‐10.0 (‐15.9 to ‐4.1) ‐42.5 (‐45.8 to ‐39.2)* |

*P < 0.05 vs placebo | |||||

| Peripheral pain (BASDAI) (VAS, 0 to 100, higher is worse) | Yes Yes No No |

Placebo (37) Active drug (117) Placebo (56) Active drug (175) |

61.8 (27.0) 61.2 (27.5) 45.4 (31.9) 43.5 (31.5) |

0.9 (‐5.9 to 7.6) ‐16.4 (‐20.3 to ‐12.6)* ‐5.5 (‐11.0 to ‐0.1) ‐26.6 (‐29.7 to ‐23.5)* |

*P < 0.05 vs placebo | |||||

| Patient global (VAS, to 100, higher is worse) | Yes Yes No No |

Placebo (37) Active drug (117) Placebo (56) Active drug (175) |

66.5 (21.8) 64.8 (23.3) 62.8 (20.5) 63.4 (20.3) |

‐3.3 (‐10.0 to 3.5) ‐22.0 (‐25.7 to ‐18.2)* ‐4.3 (‐9.7 to 1.2) ‐28.0 (‐31.1 to ‐24.9)* |

*P < 0.05 vs placebo | |||||

| BASFI (VAS, 0 to 100, higher is worse) | Yes Yes No No |

Placebo (37) Active drug (117) Placebo (56) Active drug (175) |

55.2 (29.8) 58.3 (23.8) 53.4 (25.2) 53.7 (23.3) |

‐3.5 (‐9.2 to 2.3) ‐14.9 (‐18.2 to ‐11.7)* ‐5.1 (‐9.8 to ‐0.4) ‐20.3 (‐22.9 to ‐17.6)* |

*P < 0.05 vs placebo | |||||

| Morning stiffness (duration + severity) (VAS, 0 to 100, higher is worse) | Yes Yes No No |

Placebo (37) Active drug (117) Placebo (56) Active drug (175) |

61.8 (26.0) 61.8 (25.4) 65.0 (21.4) 62.6 (23.7) |

‐5.7 (‐12.4 to 1.0) ‐24.4 (‐28.1 to ‐20.6)* ‐6.2 (‐11.6 to ‐0.7) ‐28.7 (‐31.8 to ‐25.6)* |

*P < 0.05 vs placebo | |||||

| Outcome | Peripheral arthritis? | Treatment (N) | % reaching ASAS 20 | Difference significant? | ||||||

| ASAS 20 | Yes Yes No No |

Placebo (37) Active drug (117) Placebo (56) Active drug (175) |

25% 61%* 25% 71%* |

*P = 0.001 vs placebo *P < 0.001 vs placebo |

||||||

| Discussion: "the combined active drug group provided significant clinical efficacy in AS patients with and without peripheral arthritis. The treatment responses that the authors observed…compared with placebo are in agreement with those seen in other trials...However, the magnitude of these responses was greater in patients without chronic peripheral arthritis or a history of peripheral arthritis. Although a significant difference in treatment effect among those with compared with those without peripheral arthritis was only seen for the primary end point of spinal pain, other end points demonstrated qualitatively similar differences, suggesting an overall difference in response between the two patient subgroups." | ||||||||||

| Kroon 2012 | ||||||||||

|

Original study: Post hoc analysis of Wanders 2005. Comparison: Continuous vs on‐demand NSAID treatment (ketoprofen and celecoxib). Analysis: Relevant subgroups were created by splitting ta‐CRP, ta‐ESR, ta‐BASDAI, ta‐AS‐ DAS‐CRP and ta‐ASDAS‐ESR at predefined values considered as elevated (for the acute phase reactants and representing high and low disease activity for the disease activity measures) ('low' vs 'high'). CRP levels > 5 mg/L and ESR > 12 mm/h were considered elevated; BASDAI > 4 and ASDAS > 2.1 were considered high. These subgroups were further split according to NSAID use (comparing continuous use with on‐demand use). Statistical interactions between subgroups of disease activity and mode of NSAID use, as well as their independent contributory effects, on radiographic progression were tested using multiple regression analysis and logistic regression analysis. Outcomes: BASDAI, inflammation (ESR and CRP), mSASSS, ASDAS‐ESR, ASDAS‐CRP. | ||||||||||

| Baseline characteristics | ||||||||||

| All patients | Patients with complete set of x‐rays | |||||||||

| Characteristic | Continuous use (N = 111) | On‐demand use (N = 103) | Continuous use (N = 76) | On‐demand use (N = 74) | ||||||

| Age (mean (SD) years) | 38.0 (10.7) | 40.1 (10.5) | 40.9 (9.8) | 37.9 (11.9) | ||||||

| Male (%) | 67 | 72 | 66 | 70 | ||||||

| Disease duration (mean (SD) years) | 11.9 (9.3) | 11.0 (9.4) | 13.0 (10.2) | 10.2 (9.3) | ||||||

| HLA‐B27 (pos. %) | 86 | 87 | 88 | 88 | ||||||

| "Between‐group differences at baseline were small and negligible… About 73% of the patients in both groups used celecoxib during the entire study period." | ||||||||||

| Results | ||||||||||

| Time‐averaged determinant | Outcome | Continuous treatment | On‐demand treatment | P value | ||||||

| CRP | High | dmSASSS (SD)* | 0.2 (1.6) (N = 52) | 1.7 (2.8) (N = 45) | 0.003 | |||||

| Nprog (%) | 7 (13%) (N = 52) | 17 (38%) (N = 45) | 0.011 | |||||||

| Low | dmSASSS (SD)* | 0.9 (1.8) (N = 21) | 0.8 (1.1) (N = 25) | 0.62 | ||||||

| Nprog (%) | 5 (24%) (N = 21) | 7 (28%) (N = 25) | 0.97 | |||||||

| ESR | High | dmSASSS (SD)* | 0.9 (1.6) (N = 37) | 2.0 (2.4) (N = 35) | 0.038 | |||||

| Nprog (%) | 8 (22%) (N = 37) | 17 (49%) (N = 35) | 0.031 | |||||||

| Low | dmSASSS (SD)* | 0.1 (1.8) (N = 35) | 0.7 (2.2) (N = 35) | 0.03 | ||||||

| Nprog (%) | 4 (11%) (N = 35) | 7 (20%) (N = 35) | 0.51 | |||||||

| BASDAI | High | dmSASSS (SD)* | 0.1 (1.1) (N = 18) | 1.1 (1.6) (N = 24) | 0.021 | |||||

| Nprog (%) | 1 (6%) (N = 18) | 7 (29%) (N = 24) | 0.126 | |||||||

| Low | dmSASSS (SD)* | 0.5 (1.8) (N = 58) | 1.6 (2.8) (N = 50) | 0.015 | ||||||

| Nprog (%) | 11 (19%) (N = 58) | 19 (38%) (N = 50) | 0.047 | |||||||

| ASDAS‐CRP | High | dmSASSS (SD)* | 0.4 (1.2) (N = 36) | 1.9 (2.7) (N = 40) | 0.005 | |||||

| Nprog (%) | 4 (11%) (N = 36) | 15 (38%) (N = 40) | 0.017 | |||||||

| Low | dmSASSS (SD)* | 0.4 (2.0) (N = 40) | 0.9 (2.1) (N = 34) | 0.11 | ||||||

| Nprog (%) | 8 (20%) (N = 40) | 11 (32%) (N = 34) | 0.35 | |||||||

| ASDAS‐ESR | High | dmSASSS (SD)* | 0.4 (1.3) (N = 30) | 1.8 (2.5) (N = 37) | 0.006 | |||||

| Nprog (%) | 3 (10%) (N = 30) | 15 (41%) (N = 37) | 0.012 | |||||||

| Low | dmSASSS (SD)* | 0.4 (1.9) (N = 46) | 1.1 (2.5) (N = 37) | 0.097 | ||||||

| Nprog (%) | 9 (20%) (N = 46) | 11 (30%) (N = 37) | 0.41 | |||||||

| * Mean (SD) value of δ modified stoke ankylosing spondylitis spine score (dmSASSS) in this (sub) group, defined as the difference between the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score (mSASSS) at month 0 and month 24. Nprog is the number (percentage) of participants in this (sub) group with a progression score on the mSASSS of 2 or more. | ||||||||||

| Discussion: "continued inflammation in this study represented by ESR, CRP or the combined index ASAS‐ESR and ASDAS‐CRP plays an important role in radiographic progression. … this means we would be able to select patients who may benefit more from continuous use of NSAIDs with regards to radiographic progression… continuous use of NSAIDs can almost completely counteract the negative influence of high ESR on structural damage…The application of continuous therapy with NSAIDs in patients with elevated acute phase reactants may lead to an improved benefit to RR of these drugs, although it remains important to weigh the risk and benefit in individual patients". | ||||||||||

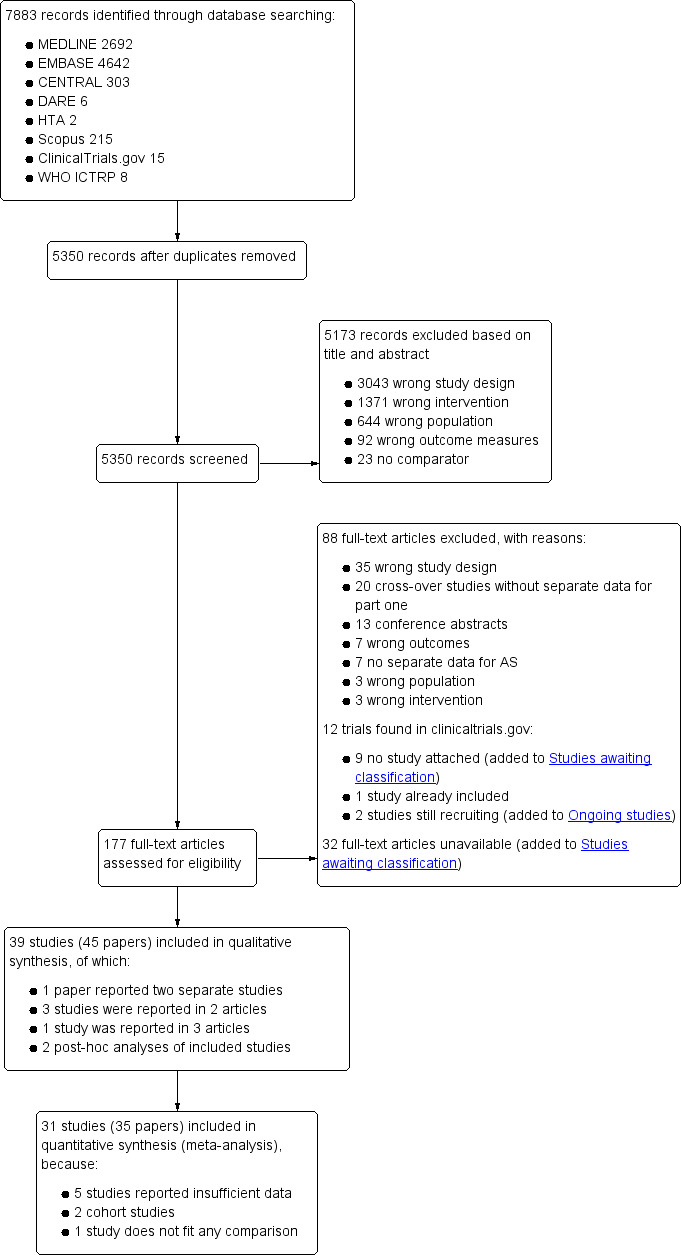

Results of the search

Through database searching we initially identified 7883 records (see Figure 1). No additional records were found through other sources. We assessed 177 full‐text articles for eligibility, of which we included 39 studies. We excluded 88 full‐text articles, for the reasons listed in the Excluded studies section. Finally, we included 31 studies in the quantitative analysis of this Cochrane review. In case the extracted data could not be used in the meta‐analysis, we reported these results in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included a total of 39 studies. In terms of study design there were 35 RCTs (of which six were cross‐over trials (Ansell 1978; Jessop 1976; Lehtinen 1984; Muller‐Fassbender 1985; Simpson 1966; Sydnes 1981)), two were quasi‐RCTs (Caldwell 1986; Calin 1979) and two were cohort studies (Boersma 1976; Poddubnyy 2012).

Characteristics of the included RCTs and quasi‐RCTs

Trial design

The 37 included RCTs and quasi‐RCTs involved a total of 4908 participants (range 14 to 611, mean 133) and were published between 1966 and 2006. Twenty‐four studies (65%) were published before 1990 (Ansell 1978; Astorga 1987; Caldwell 1986; Calin 1979; Ebner 1983; Franssen 1986; Good 1977; Heinrichs 1985; Jessop 1976; Khan 1985; Lehtinen 1984; Lomen 1986 I; Lomen 1986 P; Mena 1977; Muller‐Fassbender 1985; Myklebust 1986; Nahir 1980; Nissilä 1978a; Nissilä 1978b; Rejholec 1980; Santo 1988; Simpson 1966; Sydnes 1981; Tannenbaum 1984). Most trials were published in English, except for one trial that was in German (Heinrichs 1985) and one that was in Norwegian (Myklebust 1986). The treatment duration ranged from one week to two years, with a median duration of 12 weeks. Four studies also had an extension phase (Dougados 1999; Franssen 1986; Tannenbaum 1984; van der Heijde 2005). Fifteen trials were multicentre (Batlle‐Gualda 1996; Caldwell 1986; Dougados 1999; Dougados 2001; Khan 1985; Lomen 1986 I; Lomen 1986 P; Myklebust 1986; Palferman 1991; Sieper 2008; Sydnes 1981; Tannenbaum 1984; van der Heijde 2005; Villa Alcázar 1996; Wanders 2005), seven single centre (Carcassi 1990; Jessop 1976; Lehtinen 1984; Nahir 1980; Nissilä 1978a; Nissilä 1978b; Simpson 1966) and in 15 no information was reported on the number of centres involved.

Relevant post‐hoc analyses of two included RCTs (van der Heijde 2005; Wanders 2005) were published in a separate paper. Gossec 2005 is a post‐hoc analysis of data from van der Heijde 2005, in which a subgroup analysis was performed in patients with and without chronic peripheral arthritis. Kroon 2012 is a post‐hoc analysis of data from Wanders 2005, in which the effect of continuous versus on‐demand NSAID treatment was analysed in subgroups of patients with high vs low CRP, ESR, BASDAI, ASDAS‐CRP and ASDAS‐ESR.

Trial participants

Sixteen studies used a flare design (i.e. including only patients with a pre‐defined increase in symptoms after discontinuation of their usual treatment) and 28 studies required a wash‐out period of variable length. In 16 studies no classification criteria were reported for the inclusion of patients, and in the other 21 studies variable classification criteria were used (six trials used the modified New York criteria (Barkhuizen 2006; Dougados 1999; Dougados 2001; Sieper 2008; van der Heijde 2005; Wanders 2005), eight used the New York criteria (Batlle‐Gualda 1996; Calin 1979; Carcassi 1990; Heinrichs 1985; Lehtinen 1984; Schwarzer 1990; Tannenbaum 1984; Villa Alcázar 1996), three used the Rome criteria (Good 1977; Mena 1977; Palferman 1991), two used the ARA criteria (Khan 1985; Sydnes 1981), one used the Bennet and Wood criteria from 1968 (Jessop 1976) and one used multiple classification criteria (Dougados 1994).

All studies recruited adult participants. The mean age of participants was reported in 26 studies and was 40.5 years (SD 11.1 years, range 18 to 78). Of all participants, 81% were male (reported in 36 studies). Sixteen studies reported the mean disease duration, which ranged from 5.9 to 14 years, with a mean disease duration of 9.7 years. Nine trials reported the percentage of participants that were HLA‐B27 positive, which was on average 88.7%. Thirty‐six trials included only patients with AS, while one trial included patients with AS as well as patients with rheumatoid arthritis (Myklebust 1986). For the latter trial, we have included only the results for the AS subset in this review. No studies were found that included patients classified as having nr‐axSpA.

Interventions

The most frequently studied drug was indomethacin (15 studies: Batlle‐Gualda 1996; Caldwell 1986; Calin 1979; Carcassi 1990; Ebner 1983; Good 1977; Khan 1985; Lehtinen 1984; Lomen 1986 I; Nissilä 1978a; Nissilä 1978b; Palferman 1991; Rejholec 1980; Sydnes 1981; Tannenbaum 1984). Other frequently studied NSAIDs were diclofenac (six studies: Heinrichs 1985; Khan 1985; Nahir 1980; Santo 1988; Schwarzer 1990; Sieper 2008), naproxen (five studies: Ansell 1978; Barkhuizen 2006; Myklebust 1986; Pasero 1994; van der Heijde 2005), phenylbutazone (five studies: Franssen 1986; Jessop 1976; Lomen 1986 P; Mena 1977; Simpson 1966), piroxicam (five studies: Astorga 1987; Dougados 1999; Myklebust 1986; Sydnes 1981; Tannenbaum 1984), celecoxib (four studies: Barkhuizen 2006; Dougados 2001; Sieper 2008; Wanders 2005), flurbiprofen (four studies: Good 1977; Lomen 1986 I; Lomen 1986 P; Mena 1977), aceclofenac (three studies, Batlle‐Gualda 1996; Pasero 1994; Villa Alcázar 1996), ketoprofen (three studies: Dougados 2001; Jessop 1976; Muller‐Fassbender 1985), tenoxicam (three studies: Astorga 1987; Schwarzer 1990; Villa Alcázar 1996), oxaprozin (two studies: Caldwell 1986; Santo 1988), proquazone (two studies: Nissilä 1978a; Nissilä 1978b) and sulindac (two studies: Calin 1979; Nahir 1980). Single trials studied the following NSAIDs: butacote (Ansell 1978), diflunisal (Franssen 1986), etoricoxib (van der Heijde 2005), flufenamic acid (Simpson 1966), meclofenamate sodium (Ebner 1983), meloxicam (Dougados 1999), nabumetone (Palferman 1991), pirazolac (Carcassi 1990), tiaprofenacid (Heinrichs 1985), tolfenamic acid (Rejholec 1980) and ximoprofen (Dougados 1994).

There were five trials that included a placebo‐group (Barkhuizen 2006; Dougados 1994; Dougados 1999; Dougados 2001; van der Heijde 2005). Eighteen trials provided information about concurrent Disease Modifying Anti‐Rheumatic Drug (DMARD) and analgesic therapy. Six trials reported the allowance of stable doses of DMARDs, such as gold, penicillamine, chloroquine, sulfasalazine, methotrexate or low dose steroids (Barkhuizen 2006; Caldwell 1986; Myklebust 1986; Sieper 2008; van der Heijde 2005; Wanders 2005). Eleven trials reported that rescue analgesics without anti‐inflammatory effects, such as paracetamol, were allowed (Barkhuizen 2006; Batlle‐Gualda 1996; Caldwell 1986; Dougados 1999; Dougados 2001; Franssen 1986; Jessop 1976; Lehtinen 1984; Sydnes 1981; Villa Alcázar 1996; Wanders 2005). Four studies explicitly reported that no other analgesics or anti‐inflammatory drugs were allowed besides the study drugs (Ebner 1983; Good 1977; Mena 1977; Muller‐Fassbender 1985). None of the participants in the included studies were receiving biological DMARDs.

Characteristics of the included cohort studies

We included two cohort studies in this review:

Boersma 1976 was a retrospective cohort study comparing the effects of continuous phenylbutazone versus intermittent phenylbutazone versus no medication on radiographic progression in 40 patients with definite AS according to the New York criteria. Duration of follow‐up was variable (up to 20 years). No information was provided by trial authors on patient characteristics such as age, gender, HLA‐B27‐positivity or symptom duration.

Poddubnyy 2012 was a post‐hoc analysis of a prospective cohort study comparing the effects of low NSAID intake versus high NSAID intake on radiographic progression in 164 patients with AS (according to the modified New York criteria) or nr‐axSpA (according to the ESSG criteria). Duration of follow‐up was two years. The mean age of participants was 39.1 years, 49.5% were males, 76% were HLA‐B27 positive and the mean symptom duration was 4.3 years.

Reported outcomes

Not all included studies reported all outcomes that we planned to extract (see Types of outcome measures). In the Additional tables section we specified which outcome data were available for each study in each comparison, with a "+" indicating that the data were available in a format that could be used in the meta‐analysis, and a "*" indicating that the data were available but could not be used in the meta‐analysis (e.g. because data were reported without a measure of variance (SD, SE or CI), the number of patients per treatment group was not reported, or the data were only reported graphically) (see Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9; Table 10).

3. Available data for comparison 1 (traditional NSAID vs Placebo).

| Trial | Groups | Pain on VAS | Withdrawals due to adverse events | BASDAI | Patient's global assessment of disease activity | Duration of morning stiffness | CRP | ASAS 20 | ASAS partial remission | BASFI | Chest expansion | Schober's test | Pain relief ≥ 50% | Number of any adverse events | Number of serious adverse events | Adverse events per organ system |

| Barkhuizen 2006 | Naproxen 500 mg vs Placebo | * | + | * | * | * | * | + | * | + | + | + | ||||

| Dougados 1994 | Ximoprofen 30 mg vs Placebo | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Dougados 2001 | Ketoprofen 200 mg vs Placebo | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| Dougados 1999 | Meloxicam 15 mg vs Placebo | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| Dougados 1999 | Piroxicam 20 mg vs Placebo | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| van der Heijde 2005 | Naproxen 1000 mg vs Placebo | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

+ Available data that was used in the meta‐analysis. * Available data that could not be used in the meta‐analysis. Additional information on all included trials can be found in the Characteristics of included studies.

4. Available data for comparison 2 (COX‐2 vs Placebo).

| Trial | Groups | Pain on VAS | Withdrawals due to adverse events | BASDAI | Patient's global assessment of disease activity | Duration of morning stiffness | CRP | ASAS 20 | ASAS partial remission | BASFI | Chest expansion | Schober's test | Pain relief ≥ 50% | Number of any adverse events | Number of serious adverse events | Adverse events per organ system |

| Barkhuizen 2006 | Celecoxib 400 mg vs Placebo | * | + | * | * | * | * | + | * | + | + | + | ||||

| Dougados 2001 | Celecoxib 200 mg vs Placebo | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| van der Heijde 2005 | Etoricoxib 90 mg vs Placebo | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

+ Available data that was used in the meta‐analysis. * Available data that could not be used in the meta‐analysis. Additional information on all included trials can be found in the Characteristics of included studies.

5. Available data for comparison 3 (COX‐2 vs traditional NSAID).

| Trial | Groups | Pain on VAS | Withdrawals due to adverse events | BASDAI | Patient's global assessment of disease activity | Duration of morning stiffness | CRP | ASAS 20 | ASAS partial remission | BASFI | BASMI | Chest expansion | Schober's test | Pain relief ≥ 50% | Number of any adverse events | Number of serious adverse events | Adverse events per organ system |

| Barkhuizen 2006 | Celecoxib 400 mg vs Naproxen 500 mg | * | + | * | * | * | * | + | * | + | + | + | |||||

| Dougados 2001 | Celecoxib 200 mg vs Ketoprofen 200 mg | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Sieper 2008 | Celecoxib 400 mg vs Diclofenac 75 mg | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| van der Heijde 2005 | Etoricoxib 90 mg vs Naproxen 1000 mg | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

+ Available data that was used in the meta‐analysis. * Available data that could not be used in the meta‐analysis. Additional information on all included trials can be found in the Characteristics of included studies.

6. Available data for comparison 4 (NSAID vs NSAID).

| Trial | Groups | Pain on Likert scale | Pain on VAS | Withdrawals due to adverse events | Patient's global assessment of disease activity | Duration of morning stiffness | Severity of morning stiffness | CRP | ESR | Lateral spinal flexion | Chest expansion | Tragus‐to‐wall distance | Occiput‐to‐wall distance | Intermalleolar distance | Schober's test | Pain relief ≥ 50% | Number of any adverse events | Number of serious adverse events | Adverse events per organ system |

| Astorga 1987 | Piroxicam 20 mg vs Tenoxicam 20 mg | + | * | * | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Batlle‐Gualda 1996 | Aceclofenac 200 mg vs Indomethacin 100 mg | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Caldwell 1986 | Oxaprozin 1200 mg vs Indomethacin 50 to 150 mg | * | + | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | + | + | |||||||

| Calin 1979 | Sulindac 200 to 400 mg vs Indomethacin 75 to 150 mg | + | * | * | * | * | + | ||||||||||||

| Dougados 1999 | Piroxicam 20 mg vs Meloxicam 15 mg | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | * | * | ||||||||

| Ebner 1983 | Meclofanamate sodium 300 mg vs Indometacin 150 mg | * | + | * | * | * | * | + | + | ||||||||||

| Franssen 1986 | Diflunisal 100 mg vs Phenylbutazone 400 mg | + | + | + | + | * | * | + | |||||||||||

| Good 1977 | Flurbiprofen 150 to 200 mg vs Indomethacin 75 to 100 mg | * | + | * | * | * | * | * | * | + | + | ||||||||

| Heinrichs 1985 | Diclofenac 150 to 200 mg vs Tiaprofenacid 600 to 700 mg | * | + | * | * | * | * | + | |||||||||||

| Jessop 1976 | Ketoprofen 200 mg vs Phenylbutazone 300 mg | + | + | + | + | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Khan 1985 | Diclofenac 125 mg vs Indomethacin 125 mg | * | + | * | * | * | * | * | + | + | |||||||||

| Lomen 1986 I | Flurbiprofen 150 to 300 mg vs Indomethacin 75 to 150 mg | * | + | * | * | * | * | * | + | + | |||||||||

| Lomen 1986 P | Flurbiprofen 200 to 300 mg vs Phenylbutazone 300 to 500 mg | * | + | * | * | * | * | * | + | + | |||||||||

| Mena 1977 | Flurbiprofen 150 to 200 mg vs Phenylbutazone 300 to 400 mg | * | + | * | * | * | * | * | + | + | |||||||||

| Myklebust 1986 | Piroxicam 20 mg vs Naproxen 1000 mg | + | * | * | * | ||||||||||||||

| Nahir 1980 | Diclofenac 150 mg vs Sulindac 600 mg | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Nissilä 1978a | Proquazone 900 mg vs Indomethacin 75 mg | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||

| Nissilä 1978b | Proquazone 900 mg vs Indomethacin 75 mg | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||

| Palferman 1991 | Nabumetone 2000 mg vs Indomethacin 150 mg | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Pasero 1994 | Aceclofenac 100 mg vs Naproxen 500 mg | * | + | * | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Rejholec 1980 | Tolfenamic acid 600 mg vs Indomethacin 75 mg | * | + | * | * | * | |||||||||||||

| Santo 1988 | Diclofenac 100 mg vs Oxaprozin 1200 mg | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Schwarzer 1990 | Diclofenac 50 mg vs Tenoxicam 20 mg | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| Simpson 1966 | Flufenamic acid 600 mg vs Phenylbutazone 300 mg | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| Tannenbaum 1984 | Piroxicam 10 to 20 mg vs Indomethacin 75 to 125 mg | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| Villa Alcázar 1996 | Aceclofenac 200 mg vs Tenoxicam 20 mg | + | + | * | * | * | * | * | + |

+ Available data that was used in the meta‐analysis. * Available data that could not be used in the meta‐analysis. Additional information on all included trials can be found in the Characteristics of included studies.

7. Available data for comparison 5 (Naproxen vs other NSAID).

| Trial | Groups | Pain on VAS | Withdrawals due to adverse events | BASDAI | Patient's global assessment of disease activity | Duration of morning stiffness | CRP | ASAS 20 | ASAS partial remission | BASFI | Chest expansion | Schober's test | Number of any adverse events | Number of serious adverse events | Adverse events per organ system |

| Barkhuizen 2006 | Naproxen 500 mg vs Celecoxib 400 mg | * | + | * | * | * | * | + | * | + | + | + | |||

| Myklebust 1986 | Naproxen 1000 mg vs Piroxicam 20 mg | + | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| Pasero 1994 | Naproxen 500 mg vs Aceclofenac 100 mg | * | + | * | + | + | + | ||||||||

| van der Heijde 2005 | Naproxen 1000 mg vs Etoricoxib 90 mg | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

+ Available data that was used in the meta‐analysis. * Available data that could not be used in the meta‐analysis. Additional information on all included trials can be found in the Characteristics of included studies.

8. Available data for comparison 6 (low dose vs high dose NSAID).

| Trial | Groups | Pain on Likert scale | Pain on VAS | Withdrawals due to adverse events | BASDAI | Patient's global assessment of disease activity | Duration of morning stiffness | CRP | ASAS20 | ASAS partial remission | BASFI | BASMI | Chest expansion | Schober's test | Pain relief ≥ 50% | Number of any adverse events | Number of serious adverse events | Adverse events per organ system |

| Barkhuizen 2006 | Celecoxib 200 mg vs Celecoxib 400 mg | * | + | * | * | * | * | + | * | + | + | + | ||||||

| Dougados 1994 | Ximoprofen 5 mg vs Ximoprofen 30 mg | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Dougados 1999 | Meloxicam 15 mg vs Meloxicam 22.5 mg | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | * | * | |||||||

| Sieper 2008 | Celecoxib 200 mg vs Celecoxib 400 mg | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| van der Heijde 2005 | Etoricoxib 90 mg vs Etoricoxib 120 mg | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

+ Available data that was used in the meta‐analysis. * Available data that could not be used in the meta‐analysis. Additional information on all included trials can be found in the Characteristics of included studies.

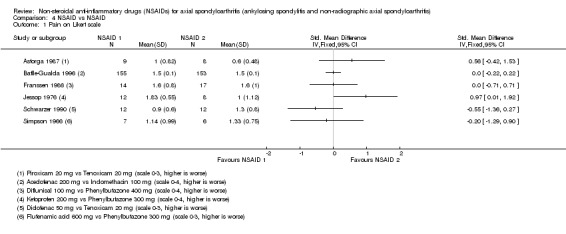

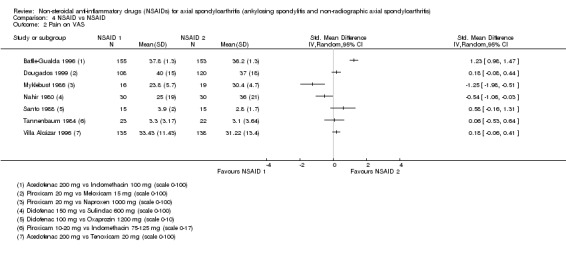

Primary outcomes

Of the 31 studies that were included in the quantitative data‐analysis, 14 trials reported pain on a VAS (which could be used in the analyses of 11 studies) and 15 reported pain on a NRS (which could be used in the analyses of six studies). There were four trials that did not report pain as an outcome (Calin 1979; Nissilä 1978a; Nissilä 1978b; Palferman 1991).

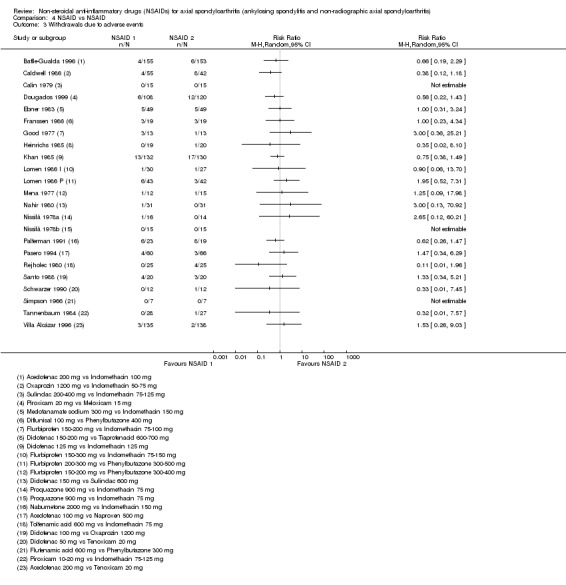

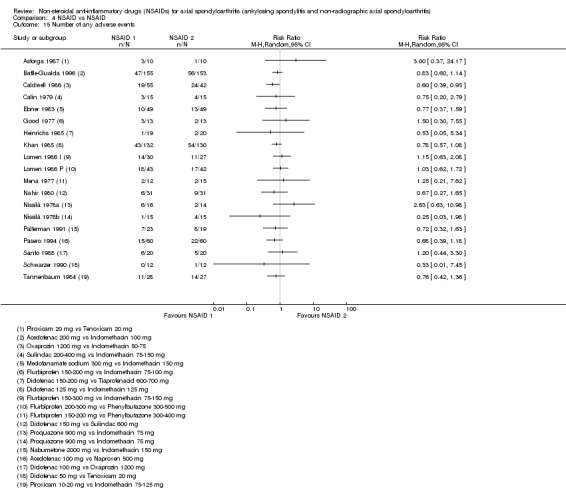

The number of withdrawals due to adverse events was reported in 28 trials (and could be used in the analyses of 28 trials). There were three trials that did not report the number of withdrawals due to adverse events (Astorga 1987; Jessop 1976; Myklebust 1986).

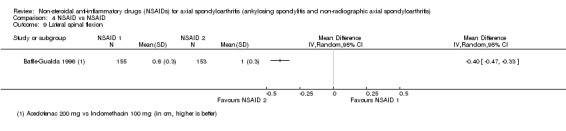

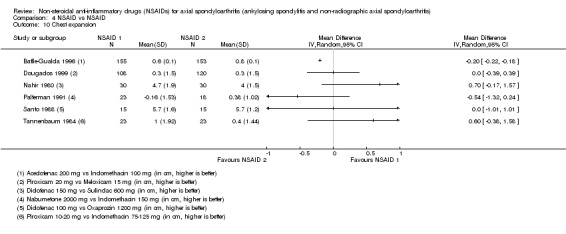

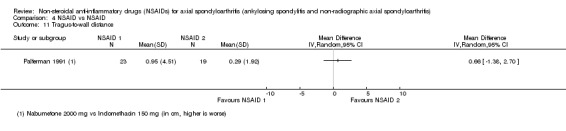

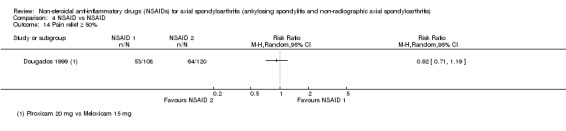

Three studies reported the BASDAI (which could be used in analyses of two studies) (Barkhuizen 2006; Sieper 2008; van der Heijde 2005). BASFI was reported in four studies (and could be used in the analyses of three studies) (Barkhuizen 2006; Dougados 2001; Sieper 2008; van der Heijde 2005). BASMI was only reported by Sieper 2008, and radiographic progression was not reported in any of the studies included in the meta‐analysis. Six studies reported the number of serious adverse events (Barkhuizen 2006; Dougados 2001; Nahir 1980; Schwarzer 1990; Sieper 2008; van der Heijde 2005).

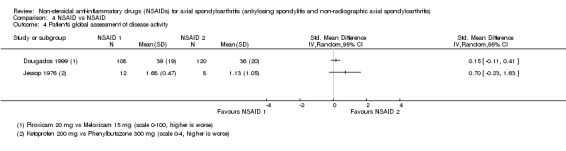

Secondary outcomes

The following secondary outcomes were reported by one or more of the studies included in the meta‐analysis: patient's global assessment of disease activity (9/31 studies, five included in analyses), duration of morning stiffness (22/31 studies, 10 included in analyses), severity of morning stiffness (2/31 studies, two included in analyses), CRP (4/31 studies, three included in analyses), ESR (7/31 studies, three included in analyses), proportion of responders according to ASAS20 (3/31 studies, three included in analyses), proportion of patients achieving ASAS partial remission (1/31 studies, one included in analyses), lateral spinal flexion (4/31 studies, one included in analyses), chest expansion (23/31 studies, seven included in analyses), tragus‐to‐wall distance (2/31 studies, one included in analyses), occiput‐to‐wall distance (11/31 studies, two included in analyses), intermalleolar distance (6/31 studies, 0 included in analyses), Schober's test (26/31 studies, 11 included in analyses), proportion of patients reporting pain relief of ≥ 50% (3/31 studies, three included in analyses), number of (any) adverse events (25/31 studies, 24 included in analyses) and adverse events broken up by bodily system (e.g. gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, neurological) (22/31 studies, 21 included in analyses).

The secondary outcomes not reported by any of the 31 studies included in the meta‐analysis were: ASDAS, fatigue, joint pain, tenderness of the joints, proportion of patients achieving ASDAS clinically important improvement (improvement ≥ 1.1 in ASDAS), proportion of patients achieving ASDAS major improvement (improvement ≥ 2.0 in ASDAS), proportion of patients achieving ASDAS inactive disease (ASDAS < 1.3), proportion of patients achieving BASDAI 50 (improvement ≥ in BASDAI), proportion of responders according to ASAS40, proportion of responders according to ASAS 5/6, cervical rotation, quality of life (assessed by SF‐36 or ASQoL score) and proportion of patients showing radiographic progression of at least two mSASSS units.

Excluded studies

Of the 177 full‐text papers that were assessed for eligibility, we excluded 88 full‐text articles for the following reasons: wrong study design (n = 35), cross‐over study without separate data for part one of the cross‐over (n = 20), conference abstract (n = 13), wrong outcomes (n = 7), no separate data available for patients with AS (n = 7), wrong population (n = 3) and wrong intervention (n = 3) (see Figure 1).

Furthermore, nine trials found in ClinicalTrials.gov did not provide any results, were not published and were thus added to Studies awaiting classification. One trial that was found in ClinicalTrials.gov was a trial that was already included and two trials were still recruiting participants. Thus we added these studies to the Ongoing studies section. Of 32 articles, no full‐text could be obtained after extensive searching, and we added these trials to the Studies awaiting classification. The most relevant excluded trials and the reasons for exclusion are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

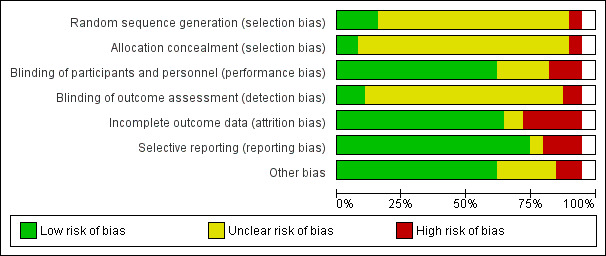

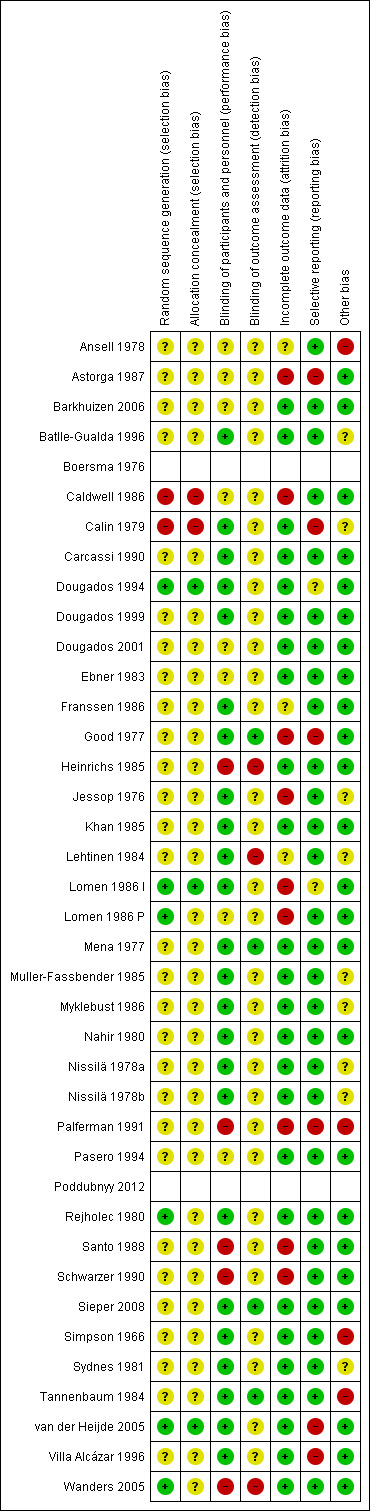

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias for each study (see Characteristics of included studies for RCTs and quasi‐RCTs, see Table 3 for observational studies). The results for RCTs and quasi‐RCTs are also summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.