Abstract

Radiotherapy is a mainstay cancer therapy whose antitumor effects partially depend on T cell responses. However, the role of Natural Killer (NK) cells in radiotherapy remains unclear. Here, using a reverse translational approach, we show a central role of NK cells in the radiation-induced immune response involving a CXCL8/IL-8–dependent mechanism. In a randomized controlled pancreatic cancer trial, CXCL8 increased under radiotherapy, and NK cell positively correlated with prolonged overall survival. Accordingly, NK cells preferentially infiltrated irradiated pancreatic tumors and exhibited CD56dim-like cytotoxic transcriptomic states. In experimental models, NF-κB and mTOR orchestrated radiation-induced CXCL8 secretion from tumor cells with senescence features causing directional migration of CD56dim NK cells, thus linking senescence-associated CXCL8 release to innate immune surveillance of human tumors. Moreover, combined high-dose radiotherapy and adoptive NK cell transfer improved tumor control over monotherapies in xenografted mice, suggesting NK cells combined with radiotherapy as a rational cancer treatment strategy.

NK cells rely on the chemokine CXCL8 to play a central role in immune responses to radiotherapy in humans.

INTRODUCTION

Radiotherapy (RT) is a mainstay cancer therapy used either in monotherapy or combined with chemotherapeutic agents, which can improve local tumor control and patient survival. In selected human tumors, RT can be combined with therapeutic antibodies such as cetuximab to further improve patient outcomes (1). At relatively low doses, RT modulates different aspects of antitumor T and myeloid cell responses, including their migration into tumor tissue via vascular remodeling (2). At higher doses, RT causes chemokine release from stroma or tumor cells (3). Mechanistically, tumor cells can enter cellular senescence upon radiation exposure, which is accompanied by the release of soluble mediators collectively called the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) (4–6). Among these SASP mediators, the cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6) and CXCL8 (=IL-8) can induce tumor invasiveness and metastasis and have repeatedly been linked to poor overall survival in cancer patients of various tumor types (7–9).

Natural Killer (NK) cells are being exploited for cancer therapy, either by adoptive transfer (10) or, more frequently, by engaging NK cells with therapeutic antibodies, such as cetuximab, to mediate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) via the Fc-receptor CD16 (1, 11, 12). Cetuximab targets the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) receptor, but its direct antitumor activity in pancreatic cancer is negligible because the EGFR signaling cascade is uncoupled from its receptor due to the high frequency of activating kras mutations in this tumor type (13). However, cetuximab could be used to engage NK cells in pancreatic cancer and other EGFR-positive tumor types. An important obstacle for this therapeutic approach is that NK cells poorly infiltrate solid tumors, which prevents them from unleashing their full antitumor activities (14–17).

While SASP immune interactions and radiation-induced T cell responses have been thoroughly studied in murine model systems, our understanding of its activity on human immune cells is limited. This is of particular importance for NK cells, which show cross-species discrepancies in chemokine receptor expression patterns and consequent differences in migration and responsiveness to cancer (18, 19). In humans, two major subpopulations of NK cells can be distinguished in peripheral blood that are not present in mice: the CD56bright subset, which can release large amounts of immunoregulatory cytokines and the CD56dim subset, which accounts for ~90% of circulating NK cells and exerts high cytotoxicity toward antibody-opsonized cells via the Fc-receptor CD16 (20). Moreover, chemokines such as CXCL8 have species-specific structural and functional properties. For example, CXCL8, while abundant in humans, does not have a structural homolog in mice complicating the direct translation from murine SASP studies to humans. We therefore hypothesized that RT effects on human leukocyte recruitment may differ from the effects described for the murine immune system and that therapeutic antibodies may help engage NK cells when combined with high-dose radiation in contrast to the previously described low-dose radiation effects causing macrophage-dependent vascular remodeling and T cell engagement (2).

To this end, we studied NK cell responses in patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing combined treatment with radiochemotherapy (RCTX) and the ADCC-mediating antibody cetuximab within a randomized controlled clinical trial. We then used experimental systems to explore mechanisms of primary human NK cell migration toward solid tumors and test combined adoptive NK cell and RT as a therapeutic strategy in xenografted mice.

RESULTS

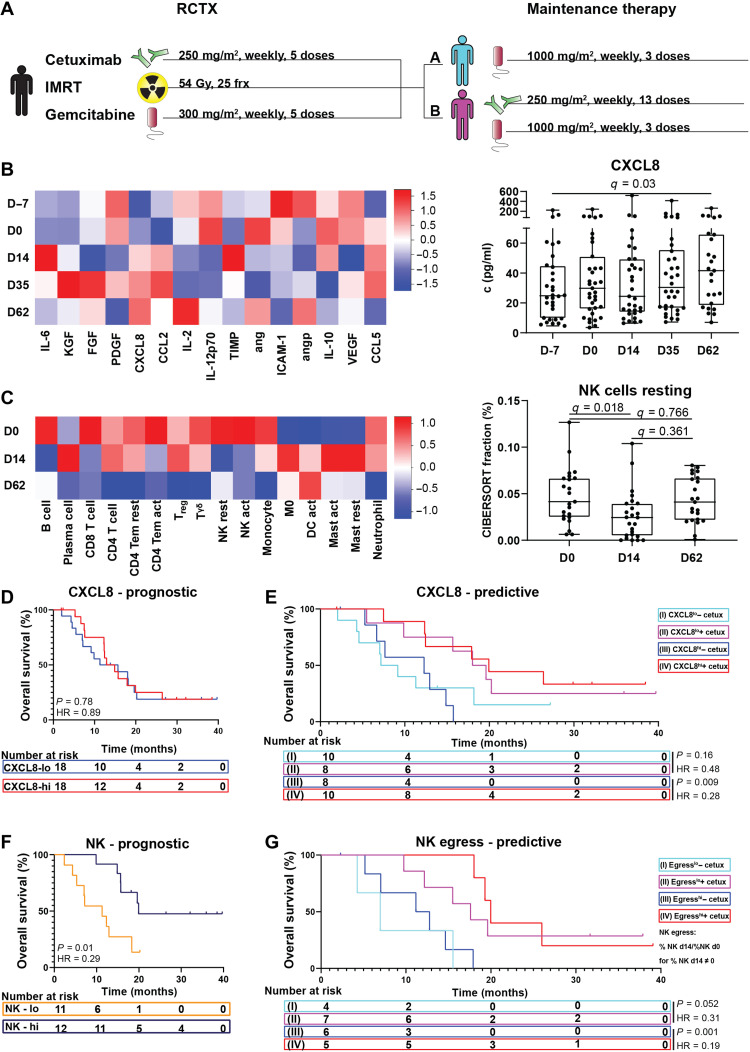

RCTX modulates CXCL8 concentrations and circulating NK cell numbers in patients with pancreatic cancer

To explore immune responses elicited by radiation and therapeutic antibodies, we longitudinally analyzed peripheral blood of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer within a single-center, randomized controlled open-label clinical trial. Patients underwent combined RCTX and subsequent maintenance therapy with gemcitabine ± the therapeutic antibody cetuximab (ISRCTN56652283; Fig. 1A and table S1). Analysis of serum cytokines revealed that only CXCL8 concentrations significantly increased during RCTX {median fold change = 1.68, q value [false discovery rate (FDR)] = 0.03} (Fig. 1B). Deconvolution of leukocyte subsets from whole-blood gene expression data (21) showed a transient drop in resting NK cell numbers in peripheral blood during RCTX (median fold change = 0.45, 0 versus day 14, q = 0.018) (Fig. 1C). Moreover, we observed a decrease in CD56dim but not CD56bright signature gene expression after radiation, suggesting that mainly the CD56dim subset was experiencing RT-induced effects (fig. S2, A and B). In contrast to NK cells, radiosensitive neutrophils did not decrease during RCTX (median fold change = 1.18, q = 0.47), arguing against radiation toxicity as the main cause of the observed changes in leukocyte subsets (fig. S1A). When comparing the randomized cetuximab and control maintenance arms, cetuximab specifically decreased circulating NK cell numbers in peripheral blood after completion of RCTX (fig. S1B). This effect was not observed in patients receiving cetuximab without prior RCTX (fig. S1C), suggesting that RCTX may modulate NK cell responses to the NK cell–engaging antibody cetuximab in patients with pancreatic cancer. Hence, combined treatment with cetuximab and RCTX increased CXCL8 serum levels and decreased peripheral blood NK cell numbers in patients with pancreatic cancer.

Fig. 1. RCTX modulates CXCL8 concentrations and NK cell numbers in patients with pancreatic cancer.

Leukocyte and cytokine levels were determined in pancreatic cancer patients undergoing RCTX followed by either combined gemcitabine and cetuximab (arm B) maintenance therapy or gemcitabine alone (arm A) in a randomized controlled clinical trial (ISRCTN56652283) (A to G). (B) Left: Heatmap indicating z-scored serum cytokine levels at time points indicated with color scale on the right. Right: Box plot indicating CXCL8 concentrations at time points indicated (n = 25 to 32 per time point). (C) Left: Heatmap indicating z-scored relative leukocyte numbers in peripheral blood as determined by the CIBERSORT algorithm with color scale depicted on the right. Right: Box plot indicating resting NK cell proportions at time points indicated (n = 23 to 25 per time point). (B and C) Q values were calculated using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests and the Benjamini and Hochberg method. (D and E) Kaplan-Meier plot indicating overall survival of patients with above (CXCL8hi) or below (CXCL8lo) day 0 median CXCL8 serum levels of all patients (D) or in treatment arms A (I and III) and B (II and IV). (F) Kaplan-Meier plot indicating overall survival of patients with above (NKhi) or below (NKlo) total peripheral blood NK cell proportions as determined by the CIBERSORT algorithm at day 0. (G) Kaplan-Meier plots indicating overall survival of patients with above median (egresshi) or below median (egresslo) decrease in peripheral blood resting NK cell numbers in treatment arms A and B, as determined by CIBERSORT. NK egress: NK proportion d0/NK proportion d14 for all NK proportion d14 ≠ 0; NK egress, ∞ for NK proportion d14 = 0. (D to G) P values and hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated using log-rank tests. act, activated; cetux, cetuximab; D, day; frx, fractions; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; mast, mast cells; rest = resting; TEM, T effector memory cell; Treg, regulatory T cell; DC, dendritic cell; HR, hazard ratio.

CXCL8 and NK cells predict response to cetuximab in irradiated pancreatic cancer patients

We next explored the prognostic and predictive value of CXCL8 and NK cells in our pancreatic cancer patient cohort. In contrast to tumors not treated with RT and therapeutic antibodies (22), we did not find a significant negative prognostic association between CXCL8 serum levels and median overall survival (mOS) in our pancreatic cancer study (Fig. 1D). Instead, patients with above-median CXCL8 serum levels (>29.8 pg/ml) showed greater mOS under maintenance therapy with cetuximab (12.2 versus 19.9 mOS, P = 0.009; Fig. 1E), an effect which was above the expected mOS for this patient population (23). This effect was not observed in patients with below-median CXCL8 levels or in the pooled patient population (Fig. 1E and fig. S3, A and B). Moreover, we found a strong prognostic association of above-median pretreatment NK cell numbers (NKhigh: CIBERSORT fraction, >4.5%) with prolonged mOS [hazard ratio (HR) 0.29, P = 0.01; Fig. 1F]. By contrast, CD8 T cells did not significantly correlate with mOS, suggesting NK cell–specific associations with prognosis (fig. S3C). Because NK cell numbers dropped under therapy (Fig. 1C), as a sign of NK cell egress from peripheral blood into the tumor tissue, we also assessed the effect of on-treatment changes in NK cell numbers on patient outcomes. While patients with above-median decrease in peripheral blood NK cell numbers (egresshi) showed prolonged mOS under cetuximab maintenance therapy (11.3 versus 20.2 months, P = 0.001; Fig. 1G), we did not observe a significant survival benefit in the egresslo patient subgroup (Fig. 1G). Using CD56dim gene expression signatures confirmed this association with survival (fig. S2C). Hence, both increased CXCL8 levels and NK cell egress correlated with survival after cetuximab treatment in irradiated pancreatic cancer patients.

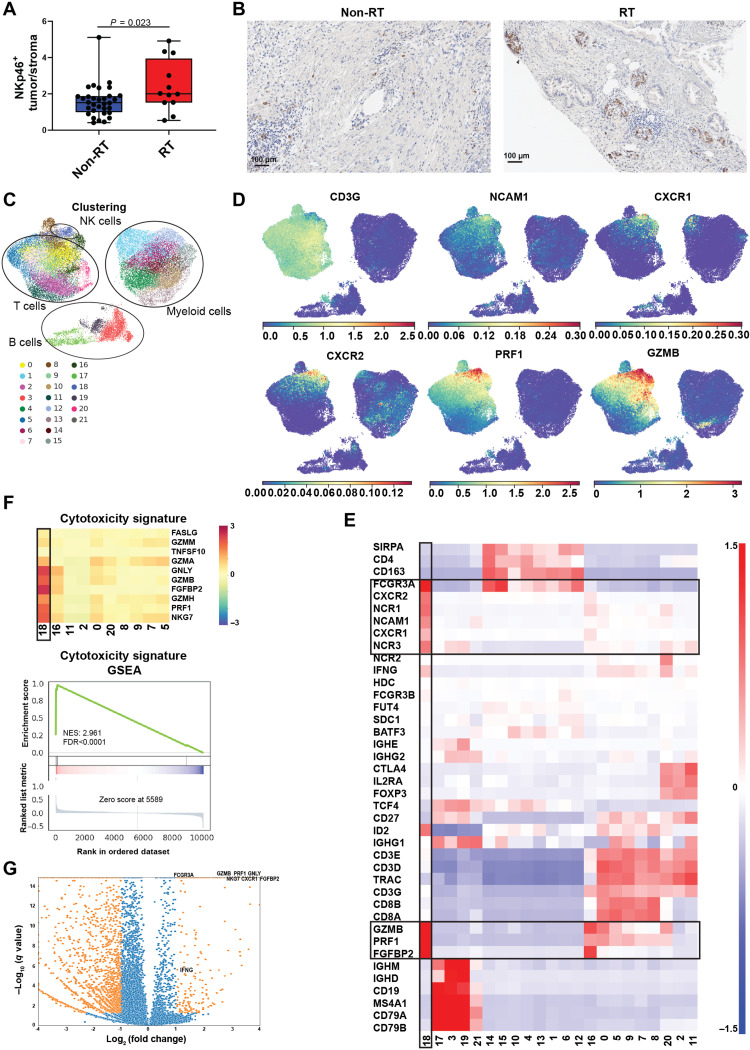

Pancreatic cancer–infiltrating NK cells exhibit CD56dim cytotoxic transcriptomic states

To assess whether RT was also associated with NK cell infiltration into human pancreatic cancers, we analyzed NKp46 expression as an NK cell marker in an independent patient cohort who underwent surgical resection, either as primary treatment or after neoadjuvant RCTX (Fig. 2, A and B, and table S2). In line with the observed drop in peripheral blood NK cell numbers after RCTX in our controlled pancreatic cancer clinical trial, we found preferential accumulation of NK cells in the resected tumors of irradiated patients as compared to nonirradiated controls (Fig. 2, A and B).

Fig. 2. Pancreatic cancer–infiltrating NK cells exhibit CD56dim-like cytotoxic transcriptomic states.

NK cell abundance and phenotype were assessed in pancreatic cancer patients. (A) Box plot indicating the ratio of NKp46+ cells in the tumor core as opposed to the surrounding stroma in surgically resected pancreatic adenocarcinomas (PDACs) of n = 32 nonirradiated and n = 12 neo adjuvantly irradiated pancreatic cancer patients. P values were calculated using an unpaired t test (B) Representative immunohistochemistry images of NKp46 staining in an irradiated (RT) and a nonirradiated (non-RT) patient. (C to G) Transcriptomic states of PDAC-infiltrating NK cells were assessed using public single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data (26). (C and D) Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction (UMAP) showing n = 42,955 pancreas/PDAC-infiltrating leukocytes with PhenoGraph clusters (C, k = 30) or MAGIC-imputed (t = 3) gene expression highlighted in color codes below (D). (E) Heatmap showing z-scored (across cells) scran-normalized marker gene expression of PhenoGraph clusters indicated with CD56dim-like NK cells highlighted with black boxes and gene expression color code on the right. (F) Top: Heatmap indicating mean z-scored (across cells) scran-normalized expression of cytotoxic marker genes in T cell/NK cell and NKT cell clusters. CD56dim-like NK cells are highlighted with a black box. Bottom: Enrichment plot showing enrichment scores and log2 ratio, which was used as a metric to calculate ranks for gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). (G) Volcano plot indicating differentially expressed genes between CD56dim-like NK cells and all remaining leukocytes as calculated by Wald’s test fitting a negative binomial model on raw count data. Genes with at least twofold change and a q value of <0.05 are highlighted in orange.

While NK cells generally exert antitumor functions, the suppressive tumor microenvironment can repolarize NK cells to acquire protumorigenic phenotypes (17, 24, 25). To study the phenotype and chemokine receptor expression patterns of pancreatic cancer–infiltrating NK cells, we analyzed public single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data (Fig. 2, C to G, and figs. S4 to S6) (26). NK cells were sparse in nonirradiated pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and in normal pancreatic tissue (fig. S5B) but showed high Fc receptor FCGR3A (CD16) expression, suggesting a CD56dim-like phenotype and thus a potential responsiveness to therapeutic antibodies such as cetuximab (Fig. 2E). Differential gene expression profiling and subsequent gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed that NK cells also expressed the highest levels of cytotoxic mediators among all leukocytes (Fig. 2, F and G). This included GZMB, PRF1, and FGFBP2, which was the most up-regulated gene in CD56dim-like tumor–infiltrating NK cells [mean fold change, 16.6; q value (FDR) < 10−11; Fig. 2, D and G] and has repeatedly been linked to NK cell cytotoxicity (27, 28).

We then assessed chemokine receptor expression patterns in pancreatic cancer–infiltrating NK cells. CXCR1 and CXCR2, the cognate CXCL8 receptors, were highly specific to pancreatic cancer–infiltrating NK cells and not found in other tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (Fig. 2E and fig. S6), supporting involvement of CXCL8 in NK cell recruitment into pancreatic cancer tissue.

Thus, PDAC-infiltrating NK cells exhibited a CD56dim phenotype with expression of CXCR1 and CXCR2 as well as cytotoxic mediators. Moreover, NK cells preferentially accumulated in the tumors of irradiated pancreatic cancer patients.

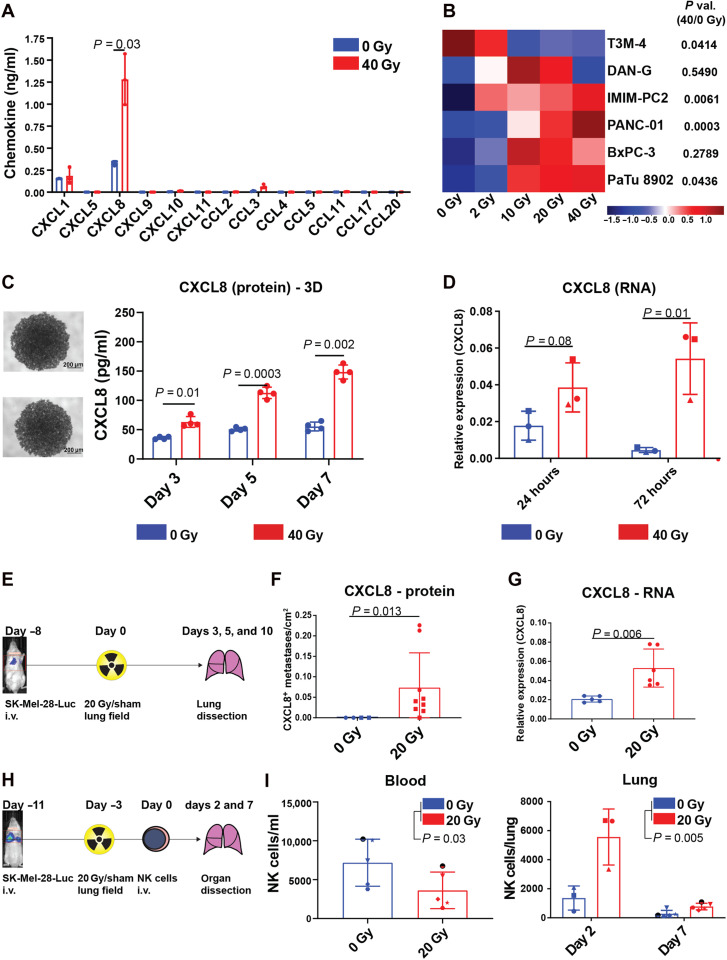

Radiation triggers CXCL8 release and NK cell migration toward irradiated tumors

To explore potential mechanisms explaining our observations from patients with cancer, we reverse-translated our findings to preclinical in vitro and in vivo models. Using an antibody-based multiplex bead array, we found that radiation markedly induced only CXCL8 levels, while other measured chemokines remained unchanged (Fig. 3A). We observed this radiation-induced CXCL8 release in three of six pancreatic cancer cell lines tested (Fig. 3B), as well as in a melanoma (SK-Mel-28; mean fold change, 3.59) and a prostate cancer cell line (PC-3M; mean fold change, 1.52) (fig. S7, A to C) in a time and radiation dose-dependent manner both in two-dimensional (2D) monolayers and in 3D spheroid systems (Fig. 3, B and C, and fig. S7, A to C). Moreover, radiation also up-regulated CXCL8 expression at the transcript level (Fig. 3D and fig. S7D), and many cells remained viable during the observation period of 5 days after irradiation (fig. S8), suggesting active up-regulation of CXCL8 by radiation rather than passive CXCL8 protein release due to membrane disintegration during cell death.

Fig. 3. RT triggers CXCL8 release and NK cell migration toward irradiated tumors.

(A) Dot plot showing means ± SD chemokine concentrations in SK-Mel-28–conditioned media (CM) 5 days after irradiation from n = 3 independent experiments as individual symbols. (B) Heatmap indicating z-scored CXCL8 concentrations in CM 5 days after irradiation from two to four independent experiments per cell line. (C) Representative images and CXCL8 levels from PANC-01 spheroids after irradiation with n = 4 spheroids per condition from one experiment. (D) Dot plots indicating means ± SD CXCL8 RNA levels relative to GAPDH after irradiation in SK-Mel-28 cells from n = 3 experiments as individual symbols. (A to D) P values were calculated using ratio paired t tests (two-tailed). (E to G) NOD.Cg-PrkdcSCID IL2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice were intravenously (i.v.) injected with luciferase-transfected SK-Mel-28 melanoma cells and treated with 20-Gy lung field irradiation/sham irradiation as indicated in (E). (F) Dot plots indicating the number per area of CXCL8+ metastases 5 to 10 days after irradiation of n = 13 mice from two independent experiments highlighted with different symbols and P value calculated with a Mann-Whitney U test. (G) Dot plot indicating CXCL8 RNA levels relative to glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) 3 days after irradiation in murine tumor bearing lungs (n = 11) and P value calculated using an unpaired t test. (H and I) NSG mice were treated like in (E) and intravenously injected with overnight IL-2–cultured NK cells as indicated in (H). (I) Left: Dot plot indicating means ± SD NK cell numbers per milliliter peripheral blood ± SD 7 days after injection from one experiment with n = 5 NK cell donors as individual symbols. Right: Dot plots indicating means ± SD NK cells per lung from two independent experiments (days 2 and 7) with n = 3 and n = 5 NK cell donors, respectively, depicted as individual symbols. P values were calculated using two-way ANOVA.

To assess the effects of RT on tumors in vivo, we used a xenograft mouse model, where luciferase-transduced tumor cells were engrafted into the lungs of NK cell–deficient NOD.Cg-PrkdcSCID IL2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice. Tumor engraftment in the lungs was confirmed by bioluminescence imaging (BLI), and tumors were locally irradiated (Fig. 3, E to G). Notably, this mouse model was only intended and suited for studying CXCL8 release from the transplanted human tumor cells because CXCL8 is not expressed by murine cells. Immunohistochemistry revealed that CXCL8-positive metastases were more frequent in irradiated animals (Fig. 3F), and irradiation also increased CXCL8 expression at the transcript level (mean fold change, 2.23; P = 0.006; Fig. 3G). Having no structural homolog in mice, CXCL8 could only be produced by the transferred tumor cells and not by the surrounding stroma, thus supporting our cell culture data. To assess NK cell migration toward irradiated tumors in the in vivo model, we intravenously injected overnight IL-2–activated primary human NK cells after tumor irradiation (Fig. 3H). Like in our patients with cancer (Fig. 1C), NK cell numbers dropped in peripheral blood after tumor irradiation (Fig. 3I, left) and accumulated in irradiated tumors, suggesting radiation-induced NK cell egress from peripheral blood into the tumor tissue (Fig. 3I, right). Moreover, combined RT and NK cell transfer reduced the number of lung metastases as compared to monotherapies, thus suggesting therapeutic efficacy of the infiltrating NK cells (fig. S9). Hence, RT induced NK cell tumor infiltration and CXCL8 release from tumor cells.

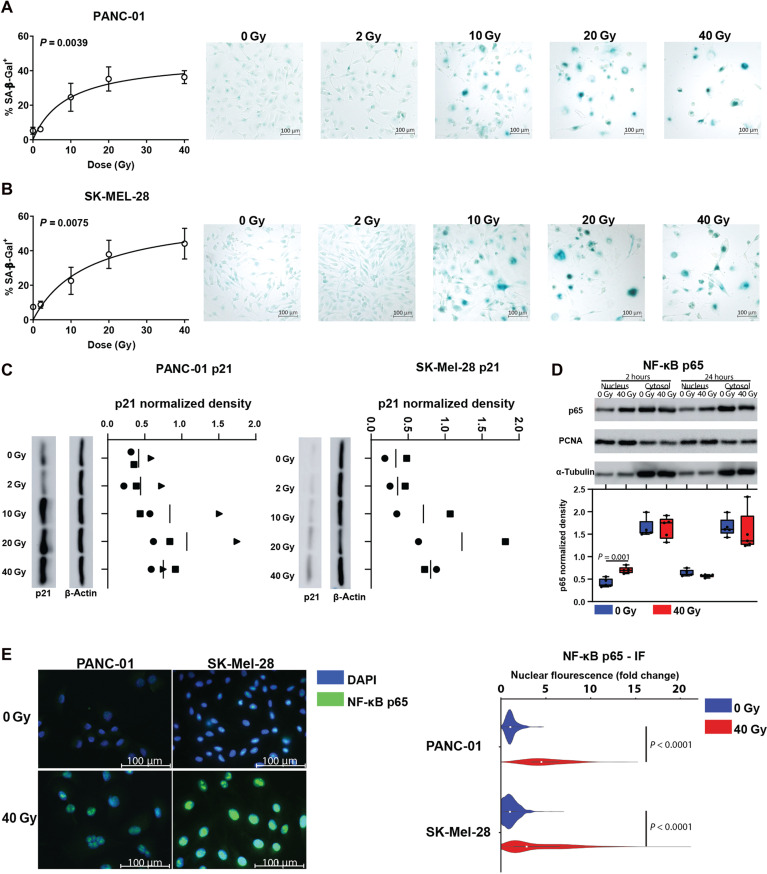

NF-κB and mTOR orchestrate radiation-induced CXCL8 release

Next, we investigated the intracellular events leading to radiation-induced CXCL8 secretion from tumor cells. Release of soluble mediators after DNA-damaging agents has been described in senescent cells as part of the SASP. In line with that, radiation significantly increased the proportion of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal)–positive tumor cells in a radiation dose–dependent manner (Fig. 4, A and B, and fig. S10). Moreover, we observed induction of p21 expression in tumor cell lines 4 days after irradiation (Fig. 4C and fig. S11).

Fig. 4. Radiation induces senescence features and NF-κB pathway activation in tumor cells.

(A and B) XY plot (left) showing the mean proportion ± SD of SA-β-Gal+ cells or representative images (right) of cell lines indicated. Tumor cells were irradiated after plating and stained for SA-β-Gal 4 days after irradiation. Indicated are data from n = 2 independent experiments per cell line. The connecting line was calculated by fitting a hyperbola curve. P values were calculated using ANOVA. (C) p21 expression in whole-cell lysates was determined by immunoblot 4 days after irradiation with indicated doses for PANC-01 cells (left panel) or SK-Mel-28 cells (right panel). Depicted are data from two to three experiments performed in parallel (biological replicates). Data points from individual experiments are highlighted by different symbols. (D) p65 expression in subcellular fractions was determined by immunoblot (WB) of SK-Mel-28 cellular fractions at indicated time points. Top: Indicated are representative WBs. Bottom: Box plots indicating p65 integrated density (ID) in WB images. For nuclear fractions, p65 IDs were divided by PCNA IDs. For cytosol fractions, p65 IDs were divided by α-tubulin IDs. Indicated are n = 5 separate WBs from three independent experiments with different symbols representing data from individual WBs. P value was calculated using a paired t test. (E) Left: Representative immunocytochemistry (IF) images of NF-κB p65 expression in PANC-01 and SK-Mel-28 cells 1 day after irradiation with 40 Gy. Right: Violin plots showing p65 fold change nuclear fluorescence in 40 Gy–irradiated (red) or mock-treated (blue) cells. Boxes within the violin plots indicate the median of n = 338 cells from two (PANC-01) and n = 2686 cells from three (SK-Mel-28) independent experiments, and P values were calculated using unpaired t tests.

The nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) transcription factor RelA(p65) is an important regulator of CXCL8 transcription (6, 29, 30) and is activated during cellular senescence. In an inactive state, this protein is sequestered in the cytoplasm by inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B (IκB) proteins, which detach after phosphorylation by IKK kinases, allowing NF-κB transcription factors to translocate to the nucleus (31). To determine the role of NF-κB in CXCL8 release, we analyzed intracellular localization of the p65 protein in irradiated and nonirradiated tumor cells. Nuclear p65 expression increased after tumor cell irradiation as determined by immunoblots of subcellular fractions (mean fold change, 1.72; P = 0.001) (Fig. 4D and fig. S12) and fluorescence microscopy (PANC-01: mean fold change, 2.45; P < 0.0001; SK-Mel-28: mean fold change, 1.93; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4E and fig. S7A). Thus, radiation triggered senescence and NF-κB pathway activation in tumor cells.

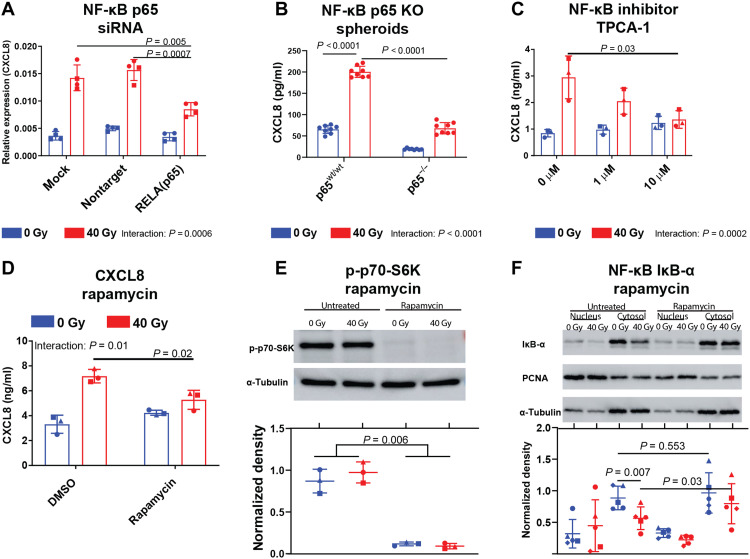

To further assess the effects of p65 in radiation-induced CXCL8 expression, we performed small interfering RNA (siRNA)–mediated knockdown and CRISPR-Cas9–mediated stable knockout of p65 in monolayer cells and cancer cell spheroids. Both siRNA and CRISPR-Cas9–based p65 perturbations blunted CXCL8 induction by radiation (interaction: ω2 = 9.89% P < 0.0001, ω2 = 8.48%, P = 0.0006, respectively) (Fig. 5, A and B, and figs. S13, B and C, and S15B). Similarly, the NF-κB inhibitor 2-(Carbamoylamino)-5-(4-fluorophenyl)-3-thiophenecarboxamide (TPCA-1) abrogated CXCL8 release from irradiated tumor cells (interaction: ω2 = 25.10%, P = 0.0002) (Fig. 5C) (32) further supporting p65 involvement in radiation-induced CXCL8 secretion.

Fig. 5. NF-κB and mTOR activities orchestrate radiation-induced CXCL8 release.

(A) Dot plots indicating means ± SD CXCL8 RNA levels relative to GAPDH in SK-Mel-28 cells transfected with p65 siRNA or nontarget siRNA 2 days after irradiation with 40 Gy. Indicated are two independent experiments with n = 4 separate transfections indicated as individual symbols (one symbol type for each experiment). (B to D) Dot plots indicating means ± SD CXCL8 concentrations in conditioned growth media of p65 knockout PANC-01 spheroids 7 days after irradiation (B) or SK-Mel-28 cells treated with the NF-κB inhibitor TPCA-1 (C) or rapamycin (D) 3 days after irradiation. Indicated are (B) n = 8 spheroids per condition of one representative of two independent experiments with different clones (second experiment in fig. S13C) or (C and D) n = 3 independent experiments as individual symbols. P values were calculated using unpaired (B) or paired t tests (A, C, and D) and repeated measures two-way ANOVA (D). (E and F) Representative images or dot plots of phospho-p70 expression in whole SK-Mel-28 cell lysates (E) or of IκB-α expression in subcellular fractions (F) was determined by WB. Top: Indicated is a representative WB. Bottom: Box plots indicating integrated density (ID) in WB images. For nuclear fractions, p65 IDs were divided by PCNA IDs. For cytosol fractions and whole-cell lysates, p65 IDs were divided by α-tubulin IDs. Indicated are n = 5 separate WBs from three independent experiments with each dot representing one WB. P values were calculated using paired t tests or a two-way ANOVA. KO, knockout; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

Since the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) serine/threonine protein kinase has also been implicated as a major SASP regulator (33, 34), we determined its role in radiation-induced p65 activation and CXCL8 release. Rapamycin down-regulated CXCL8 release from irradiated but not from nonirradiated tumor cells (interaction: ω2 = 21.57%, P = 0.01) (Fig. 5D). Rapamycin also repressed p70–S6 kinase phosphorylation, thus confirming its inhibition of mTOR (P = 0.006; Fig. 5E and fig. S14). As a sign of NF-κB activation, radiation depleted iκB-α from the cytosol (mean fold change, 0.64; P = 0.007; Fig. 5F), and rapamycin increased iκB-α levels in irradiated (mean fold change, 1.39; P = 0.03; Fig. 5F) but not in nonirradiated cells (mean fold change, 1.1; P = 0.55; Fig. 5F and fig. S14). While mTOR positively regulated radiation-induced CXCL8 secretion, mTOR itself was not activated by RT as evidenced by stable levels of downstream signaling pathways (figs. S13, D and E, and S15A). Thus, our data suggest mTOR as a steady-state pathway regulating NF-κB activation by lowering expression levels of the NF-κB inhibitory protein iκB-α in irradiated cells. Hence, NF-κB and mTOR regulate radiation-induced CXCL8 release from tumor cells.

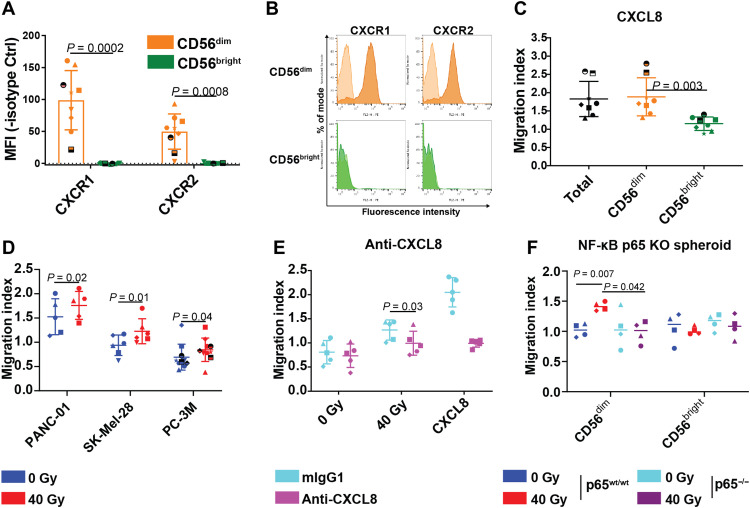

NF-κB–dependent CXCL8 release regulates radiation-induced NK cell migration

Next, we analyzed chemokine receptor expression on the functionally distinct CD56bright and CD56dim peripheral blood NK cell subsets, the latter of which we also found to infiltrate pancreatic cancers in humans (Fig. 2, C to G, and fig. S6). CD56dim but not CD56bright primary human NK cells expressed the cognate CXCL8 receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 (Fig. 6, A and B) (19). Accordingly, recombinant CXCL8 attracted CD56dim, but not CD56bright NK cells, in vitro (Fig. 6C and fig. S16, A and B). Moreover, tumor cell irradiation triggered NK cell migration toward three analyzed tumor cell lines (PANC-01, P = 0.02; SK-Mel-28, P = 0.01; PC-3M, P = 0.04), suggesting soluble mediators to regulate radiation-induced NK cell migration (Fig. 6D). Consistent with the hypothesis that CXCL8 regulated this process, a CXCL8-neutralizing antibody reduced NK cell migration toward irradiated tumor cells (mean fold change, 0.79; P = 0.03) (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6. NF-κB–dependent CXCL8 release mediates NK cell migration toward irradiated tumor cells.

(A) Dot plots showing chemokine receptor surface expression of freshly isolated primary human NK cells. Indicated are means of median fluorescence intensities (MFIs) ± SD from five independent experiments of n = 9 donors indicated as individual symbols. Dashed line indicates an MFI of zero. (B) Representative histograms of chemokine receptor surface expression (filled) or respective isotype control stainings (shaded) of freshly isolated primary human NK cells. (C to F) Dot plots showing mean overnight IL-2–activated NK cell migration indices ± SD toward recombinant CXCL8 (10 ng/ml) (C), CM from different tumor cell lines 5 days after irradiation with 40 Gy (RT) or mock treatment (non-RT) (D), conditioned growth media of 40 Gy–irradiated SK-Mel-28 cells treated or untreated with neutralizing CXCL8 antibody (E), or toward 40 Gy irradiated (RT) or mock-irradiated (non-RT) p65wt/wt or p65−/− PANC-01 spheroids (F). Indicated are mean migration indices ± SD of n = 8 NK cell donors from five independent experiments (C), n = 5 to 10 NK cell donors per cell line from three to five experiments (D), n = 5 CD56dim NK cell donors from two independent experiments (E), and n = 5 CD56dim NK cell donors from three independent experiments (F). Donors are indicated as individual symbols. P values (two-tailed) were calculated using paired t tests.

We then assessed the impact of NF-κB pathway inhibition in cancer cells on NK cell migration. In line with its effects on radiation-induced CXCL8 expression, the NF-κB inhibitor TPCA-1 abrogated NK cell migration toward irradiated tumor cells (mean fold change, 0.67; P = 0.02; fig. S16C). Furthermore, NF-κB p65 CRISPR-Cas9–mediated knockout abrogated CD56dim migration toward tumor cell spheroids (Fig. 3F). Thus, NF-κB–dependent CXCL8 release from tumor cells regulates radiation-induced NK cell migration.

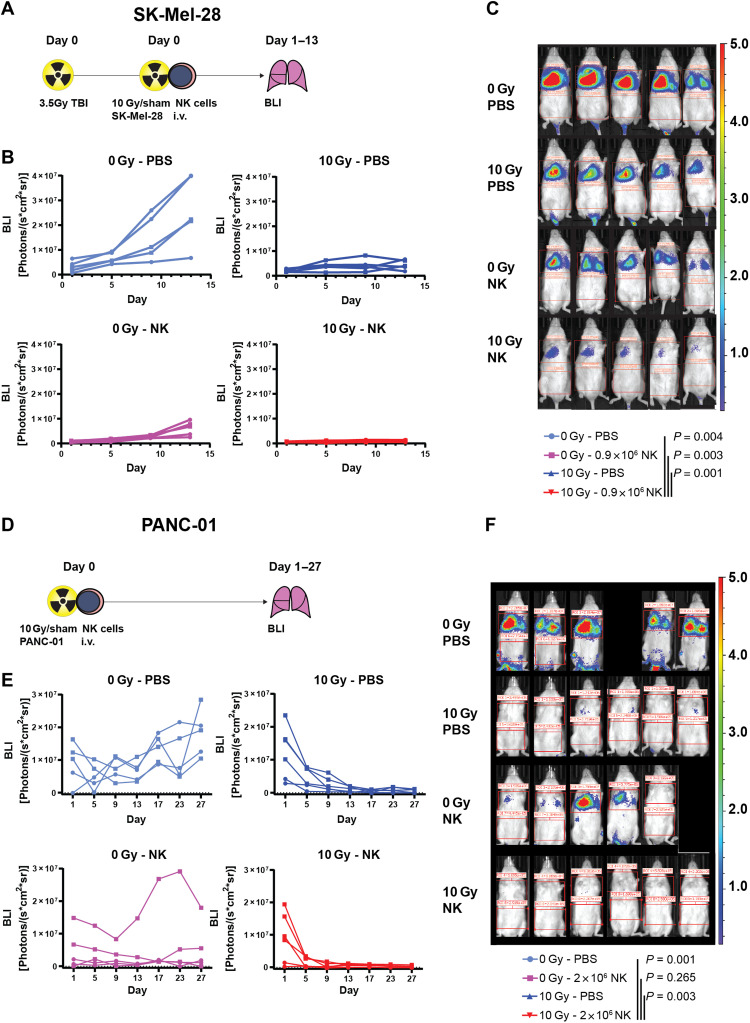

Combined radiation and adoptive NK cell transfer abrogate tumor growth in mice

On the basis of our clinical associations and mechanistic data, we hypothesized that reinforcing NK cell antitumor activity may enhance tumor control achieved by RT. For this purpose, we combined radiation with adoptive transfer of human NK cells in NK cell–deficient male NSG mice and measured tumor growth in the lungs by BLI using two different tumor cell lines, SK-Mel-28 and PANC-01 (Fig. 7). To enhance engraftment, SK-Mel-28 cells were injected into total body irradiated (TBI) mice (Fig. 7A). Radiation alone mitigated tumor growth but did not induce tumor control in the lungs (Fig. 7, B and C). While NK cells alone initially strongly decreased tumor outgrowth, tumors continued to grow starting 9 days after NK cell injection (Fig. 7, B and C). Although radiation or NK cells alone achieved strong tumor control, combined radiation and adoptive NK cell transfer led to a further decrease of tumor load as assessed by BLI in all animals (P < 0.004 versus untreated, P = 0.003 versus NK only, P = 0.001 versus RT only; Fig. 7, B and C, and fig. S17).

Fig. 7. Combined radiation and adoptive NK cell transfer abrogate tumor growth in mice.

NK cells in PBS or PBS alone and 10 Gy–irradiated or nonirradiated luciferase-transduced tumor cells were intravenously injected into NSG mice. Tumor load in the lungs was determined by BLI at time points indicated. (A to C) SK-Mel-28 cells were injected in TBI (3.5 Gy) NSG mice (A). (B) Scatterplots indicating tumor sizes of individual mice with individual data points indicated as dots and lines connecting data points of each individual mouse. Indicated are merged data from two independent experiments for a total of n = 5 mice per group (the first experiment n = 3 per group, indicated as circles, the second experiment n = 2 per group indicated as squares). (C) Representative overlay pictures of photographs and BLI pseudocolor maps at day 13 with color code depicted on the right. (D to F) PANC-01 was injected into nonirradiated NSG mice (D). (E) Scatterplots indicating tumor sizes of individual mice with individual data points indicated as dots and lines connecting data points of each individual mouse. Indicated are merged data from two independent experiments for a total of n = 5 to 6 mice per group (the first experiment n = 2 per group indicated as circles, the second experiment n = 3 to 4 per group indicated as squares). (F) Representative overlay pictures of photographs and BLI pseudocolor maps at day 27 with color code depicted on the right. P values were calculated using repeated measures two-way ANOVA or a mixed-effects model approach if missing values were encountered.

In the PANC-01 tumor model, TBI before tumor cell injection was dispensable given better tumor engraftment (Fig. 7D). Apart from limiting tumor outgrowth, NK cells and radiation led to a significant reduction of tumor load, as measured by BLI, in this model (Fig. 7, E and F). Like in the SK-Mel-28 model, only combined NK cells and radiation induced sustained PANC-01 tumor control with five of six mice remaining tumor-free after 27 days follow-up (defined as BLI < 5 × 105 on two consecutive measurements), whereas zero of five, two of six, and zero of five mice remained tumor free in the untreated, RT monotherapy, and NK cell monotherapy groups, respectively. Hence, combined radiation and adoptive NK cell transfer achieved superior antitumor activity versus monotherapies in mice.

DISCUSSION

Here, we found a yet unappreciated effect of CXCL8 and NK cells in RT. CXCL8 is generally considered protumorigenic and has been associated with poor prognosis in patients with cancer (7–9, 35). By contrast, we found that radiation-induced CXCL8 can attract human NK cells as antitumor immune effectors with potentially important implications for NK cell–based immunotherapy strategies. Radiation-induced NK cell migration was limited to the CD56dim NK cell subset, which expressed the cognate CXCL8 receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2. Mechanistically, radiation-induced CXCL8 release depended on mTOR-dependent NF-κB activation in tumor cells with phenotypic features of cellular senescence. We therefore established a link between cellular senescence and innate immune surveillance of human tumors. At the same time, our findings may provide a biological rationale for the observed enhancement of NK cell infiltration after other DNA-damaging agents such as chemotherapy (36). While CD56bright NK cells predominate certain other cancers, such as cervical cancer and renal cell carcinoma (37, 38), we find here that NK cells in PDAC show CD56dim -like transcriptomic states. NK cells showed the highest expression of cytotoxic gene signatures of all leukocytes in the PDAC microenvironment, which might explain the positive associations of NK cells with survival described in our randomized controlled clinical trial. In an experimental therapeutic model, we also found that reinforcing NK cell antitumor activity by adoptive transfer in combination with radiation can induce tumor control in mice.

Our results in irradiated tumor cells suggest that irradiation induces cellular senescence leading to CXCL8-release likely as part of a SASP. While SASP factors help maintain tumor cell senescence, they can also induce tumor cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition (39, 40), invasiveness, and metastasis (41, 42). CXCL8 plays an important role in these processes and has frequently been associated with poor prognosis in patients with breast, colon, ovarian, and prostate cancer and patients with melanoma (8). As a mechanism counteracting these prometastatic effects, we reveal that CXCL8 helped recruit NK cells into the tumor, which also reduced tumor load in the lungs. Hence, our data support the notion that CXCL8 effects on cytotoxic CD56dim NK cells may constitute an immunological surveillance mechanism of senescent cells (43, 44). Along these lines, potent NK cell antitumor activity has been demonstrated as a prerequisite for subsequent T cell–mediated antitumor immune responses (45, 46). While an imbalance of CXCL8’s protumor and antitumor effects could favor tumor progression, our data suggest that reinforcing NK cell activity may tip this balance toward antitumor function. This also supports the established concept that protein and cellular functions are highly dependent on their environmental and therapeutic context, perhaps prototypically well described by the disparate effects of chemotherapy-induced autophagy activation in the immune competent and deficient context (47).

As a clinical correlate supporting an antitumor immune response in humans, we show that both NK cells and CXCL8 were associated with improved therapeutic efficacy in a randomized controlled clinical trial combining RT and cetuximab. Because of the activating kras mutations observed in most PDAC, the here-reported signs of antitumor activity of cetuximab in our patients with high pretreatment CXCL8 serum levels and high NK cell egress from peripheral blood were likely ADCC-mediated rather than the result of EGFR signaling inhibition. Hence, our data in patients with pancreatic cancer suggest that cetuximab combined with RCTX may have yet unappreciated clinical activity connected to superior NK cell activity. These subset analyses were not predefined in the clinical trial study protocol but support a hypothesis from Melero et al. (14), who suggested that NK cell infiltration enhancing therapies may be promising combination partners for ADCC-mediating antibodies. The concept of combining RT with ADCC-directed therapies may be of particular relevance for cancer patients with high CXCL8 serum levels, because this patient subgroup generally does not benefit from anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint blockade as shown in melanoma and non–small cell lung cancer (48). Using more potent NK cell engagers such as bispecific or trispecific antibodies linking tumor targets to the CD16 receptor may further increase NK cell efficacy after irradiation (49).

Our study also emphasizes the importance of functional human immunological studies to understand cell-extrinsic SASP effects. CXCL8 was the dominant SASP chemokine in the human cell lines investigated but has no structural homolog in mice. Similarly, NK cells and other innate immune cells show disparate chemokine receptor expression patterns in mice and humans (50). Hence, it is likely that immune surveillance of senescent tumors cells also differs in mice and humans. For example, Ruscetti et al. (51) described that in murine lung cancer models, tumor necrosis factor–α and NK cells mediated immune surveillance of senescent tumor cells after experimental therapy with trametinib and palbociclib. Notably, studying human immunology and radiation responses with xenograft models also comes with several caveats. In one of our therapeutic models, 3.5 gray (Gy) total body radiation was required to generate stable tumor engraftment and bioluminescence signals, a dose close to the lethal dose 50 in NSG mice. Moreover, primary human NK cells that are not genetically modified or artificially expanded are short-lived in mice, which, together with radiation toxicity, complicates long follow-up times in the model.

A challenge when studying human cellular radiation responses is a certain dose and fractionation dependence. However, our overlapping findings on NK cells in patients with cancer at clinical standard fractionated dosing and the preclinical data at the higher end of dosing support the notion that our results are valid over a wide and clinically important dose range. We have previously reported that low-dose radiation (2 to 5 Gy single dose) elicits its antitumor immune responses through different mechanisms, primarily facilitating T cell infiltration via vasculature remodeling through macrophages (2). This indicates that tumor immune responses to ionizing radiation are not uniform but clearly dose dependent with marked relevance for NK cells at higher doses. This is increasingly relevant because the ongoing technology progress in high-precision RT allows for high radiation doses in cancer RT regimens.

Together, our study highlights the strength of reverse-translating clinical observations to experimental systems with primary human immune cells, which revealed a CXCL8-dependent mechanism that is absent in the murine immune system. Our results also link mechanisms of CXCL8 induction to innate immune vigilance as a central factor in antitumor responses to RT in humans. RT may represent a therapeutic strategy to enhance NK cell infiltration, which can be readily applied in the clinical setting, especially in patients with high pretherapeutic NK cell numbers. NK cell–engaging therapies such as therapeutic antibodies or adoptive NK cell transfers may further increase NK cell antitumor activity in patients with irradiated cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental design

In this study, we sought to determine immunological mechanisms of high-dose RT. For this purpose, we assessed peripheral blood leukocyte and chemokine levels in patients of a single-center randomized controlled open-label clinical trial and correlated them with patient overall survival. Patient numbers were predefined as indicated in the study protocol and on the basis of sample size estimation (end point overall survival, α = 0.05 and 1-β = 0.8) (52). All blood samples were included in the analysis. Overall survival was defined as a secondary end point in the study protocol (52); the primary end point was safety and has been reported elsewhere (53). Subset analysis was not predefined in the study protocol. To assess correlates of CXCL8 on NK cell migration into the tumor, we analyzed NK cell infiltration in PDAC tissue sections of a retrospective patient cohort that included all samples retrieved from our pancreatic cancer biobank with appropriate quality as determined by a pathologist blinded to the study’s hypothesis. To explore NK cellular phenotypes and chemokine receptor expression status, we used public scRNA-seq data of patients with PDAC (26). On the basis of these findings, we assessed radiation-induced CXCL8 secretion and subsequent effects on NK cell migration in vitro and in human xenograft mouse models. We then tested whether the identified interactions could be therapeutically exploited by using a xenograft mouse model of adoptive NK cell transfer and radiation. For the therapeutic mouse experiments, sample size was prespecified (end point bioluminescence intensity, α = 0.05 and 1-β = 0.8). In the entire study, outliers were included in data analysis and treated as normal samples to avoid bias in data interpretation.

Mice and tumor cells

NSG mice were bred in German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) animal facility and housed in individually ventilated cages under specific pathogen–free conditions, generally in groups of three to six with abundant autoclaved food and water in accordance with German animal protection legislation. Eight- to twelve-week old male mice were used for all experiments. Male mice were used because of more consistent tumor engraftment as opposed to females. All experiments were performed with permission of the animal protection authorities (Regierungspräsidium Karlsruhe, permit G-16/14, G-245/18) and in compliance with German legislation and GV-Solas guidelines. Cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Virginia), P.E.H. (DKFZ), S. Schölch (DKFZ), and A.C. (Heidelberg University). Cell line authentification was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) genotyping (Eurofins Scientific, Brussels).

Human tumor cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin (100 IU/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and 2 mM l-glutamine at 37°C 5% CO2. PC-3M cells were cultured in Ham’s F12 nutrient mixture containing 10% FCS, penicillin (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). For spheroid generation, cells were cultured in 96-well ultralow attachment plates (CLS7007, Corning) and incubated for 16 hours to allow for spheroid formation before irradiation and other downstream applications. Growth media were renewed every 2 days, and intactness of spheroids was monitored by microscopy. Cells were irradiated using either a Gammacell 1000 containing a Cs-137 source (Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd.) or a MultiRad225 (Faxitron) x-ray machine.

Isolation of human PBMCs and NK cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from healthy donor buffy coats using density gradient centrifugation with a polysucrose solution (1.077 g/ml; Biocoll, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). NK cells were isolated using negative selection magnetic-assisted cell sorting (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-092-657), which generally yielded >90% CD56+CD3− cells in viable PBMCs as determined by flow cytometry. Unless indicated differently, NK cells were cultured in Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) serum-free stem cell growth medium (CellGenix) containing 10% human AB serum, penicillin (100 IU/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and human recombinant IL-2 (200 IU/ml). Medium was changed every 2 to 3 days.

Xenograft mouse model

A total of 0.75 × 106 eGFP-2A-CBGr99 transduced SK-Mel-28 melanoma cells per animal were injected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) into the tail vein. After 7 days, tumor engraftment in lungs was confirmed by BLI after intraperitoneal injection of d-luciferin (7903-1G, Biovision) on an IVIS Lumina Series III (PerkinElmer) under inhalation anesthesia with isoflurane. Mice were matched to experimental groups according to BLI, and only mice with adequate BLI [lung field > 5 × 105 photons/(s*cm2*sr)] were used for subsequent experiments. Mice were irradiated using a linear accelerator (ARTISTE, Siemens), and radiation was confined to lung fields using a 160 MLC multileaf collimator. NK cells were cultured overnight in stem cell growth medium (CellGenix, 20802-0500) containing IL-2 (200 IU/ml; Miltenyi Biotec, 130-097-745) and injected into tail veins (5 × 106 cells per mouse).

For the therapeutic model, tumor cells were irradiated ex vivo using a 137Cs source to protect radiosensitive NSG mice from excessive radiation sickness. For the SK-Mel-28 model, mice were TBI with 3.5 Gy to enhance tumor engraftment, and 0.72 × 106 tumor cells per mouse and 0.9 × 106 NK cells per mouse were intravenously injected into the tail veins. For the PANC-01 model, 2 × 106 tumor cells per mouse and 2 × 106 NK cells per mouse were injected. BLI was measured over the lung fields at time points indicated and corrected by the background BLI over the abdomen; if metastases developed in the abdomen, background BLI was measured in the tail area. NK cells were activated for 2 days in IL-2 (200 IU/ml) containing growth medium before injection. Dosimetry was performed by the research group “Physical Quality Control in Radiation Therapy” at DKFZ Heidelberg. After TBI, mice were treated with enrofloxacin or cotrimoxazol in drinking water to prevent infections according to animal protection guidelines. Reporting of animal experiments is in accordance with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines (54).

Reisolation of human NK cells from tumor-bearing mice

Two to seven days after NK cell injection, mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, and blood was drawn from the retroorbital vein plexus and anticoagulated using sodium heparin. A total of 0.4 ml of blood per mouse was incubated in red blood cell lysis buffer. Lungs were perfused by injecting 5 ml of PBS into the right ventricle, washed, minced with a scalpel, incubated in digestion buffer containing sheep testis hyaluronidase V and deoxyribonuclease I (DNAse I), and pressed through a 70-μm cell strainer. Leukocytes were isolated using density gradient centrifugation (CL5035, Cedarlane Laboratories, Canada). Isolated leukocytes were washed and transferred onto 96-well plates for flow cytometric staining. Cells were quantified by flow cytometry using bead standards (345249, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and absolute NK cell numbers were interpolated from a standard curve.

siRNA-mediated knockdown

Cells were reverse transfected with siRNAs using the DharmaFECT 1 Transfection Reagent (Dharmacon, T-2002-02) and OptiMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) growth medium to complex the siRNAs. Briefly, tumor cells were passaged 2 days before the experiment in antibiotic-free complete growth media, detached using 1 mM EDTA in PBS, washed, resuspended in complete growth medium containing transfection reagent and complexed siRNAs, and seeded in 25-cm2 tissue culture flasks. After 48 hours, cells were detached using 1 mM EDTA in PBS, irradiated using a 137Cs source, seeded in 25-cm2 tissue culture flasks, and cultured for 2 days. The following siRNAs used here were RELA (AM16708, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Silencer Negative control 1 (AM4611, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

CRISPR-Cas9–mediated knockout

Guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting the constitutively transcribed exons 3 to 5 were designed using online tools by Thermo Fisher Scientific and Benchling (forward: TCCTTTCCTACAAGCTCGTGGTTTT; reverse: CACGAGCTTGTAGGAAAGGACGGTG). We selected sequences based on their Cutting Frequency Determination (CFD) score (55) and potential off-target effects (56). Off-target sites with up to three mismatches were compared with the human genome (GRCh38/hg38) using the National Center for Biotechnology Information 1000-genome browser. gRNAs were integrated into GeneArt CRISPR Nuclease Vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A21175) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and amplified in One Shot TOP10 Chemically Competent E. Coli (Invitrogen, C4040-10). Plasmids were isolated using GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, K0702) and checked for correct integration using Sanger sequencing. For transfections, plasmids were amplified and isolated using the Plasmid Midi Kit (Qiagen, 12145). Transfection of PANC-1 cells was performed with Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, L3000001) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cancer cells were seeded 1 day before the experiment and grown to approximately 70% confluence. Lipofectamine 3000 was diluted in Opti-MEM medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 31985062), and the plasmid was mixed with Opti-MEM and P3000 reagent. The diluted vector was then incubated for 5 min at room temperature with the Lipofectamine 3000 solution. Medium of cultured cancer cells was then replaced by a mix of the vector-containing solution and fresh antibiotic-free growth medium. Two days later, cells were detached with 1 mM EDTA in PBS and stained for the transfection reporter protein with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) mouse anti-human CD4 antibody (BD Pharmingen, 555346). Positive cells were selected, and single cells were sorted into 96-well microplates by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (BD FACSAria II). Subsequently, cell clones were expanded and protein was isolated. Clones with a sufficient knockout were identified by verifying the absence of NF-κB p65 subunit protein through Western blot analysis.

Generation of luciferase expressing tumor cells

To generate luciferase expressing SK-Mel-28 cells, the green fluorescent protein (GFP)–click beetle luciferase expression cassette (eGFP-2A-CBGr99) was inserted into the pBabe-puro plasmid. Plasmids were transfected into competent bacteria and packaged into retroviral vectors. Then, SK-Mel-28 melanoma cells were transduced and selected using growth media containing appropriate puromycin concentrations and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (BD FACSAria II). To generate luciferase expressing PANC-01 cells, a vector containing an expression cassette of firefly-luciferase fused to GFP was transfected into PANC-01 cells, and GFP-positive cells were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (BD FACSAria II).

Chemical inhibitors

For TPCA-1 treatment, cells were detached using EDTA, irradiated using a 137Cs source, seeded in 25-cm2 tissue culture flasks, and incubated at 37°C 5% CO2. TPCA-1 (1 or 10 μM; S2824, Selleckchem) was added to cell cultures after irradiation.

For rapamycin treatment, cells were passaged, placed into growth medium containing 5 nM of rapamycin (9904S, Cell Signaling Technology), and incubated at 37°C 5% CO2 for 1 day. Cells were detached and irradiated as indicated above, placed in 25-cm2 tissue culture flasks in growth media containing 5 nM rapamycin, and incubated at 37°C 5% CO2.

On day 2 after irradiation, cells were placed in serum-free, TPCA-1/rapamycin-free growth media containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Cell-free supernatants were harvested on day 3 after irradiation and used for migration assays or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Cell migration in vitro

Modified Boyden chamber assays were used to assess cell migration in vitro. Tumor cells were irradiated using a 137Cs source (dose rate > 7.5 Gy/min) or remained nonirradiated and cultured in 25-cm2 tissue culture flasks at 37°C 5% CO2. One day before harvesting supernatants, cells were placed into serum-free growth media containing 0.5% BSA. Cell-free supernatants were harvested and stored at −20° to −80°C until analysis. Thawed supernatants were added to bottom chambers (Corning Inc., #3421). For CXCL8 neutralization, CXCL8 antibody (6217, R&D Systems, Mab208) or isotype control [mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) 1k Isotype Control LEAF, MOPC-21, BioLegend, 400124] were added to supernatants. Equal numbers of NK cells cultured overnight in IL-2–containing growth media were added to the top chambers, which were immediately placed into bottom chambers containing cell-free supernatants and incubated for 4 to 6 hours at 37°C 5% CO2 depending on experiment. Cells were harvested and transferred onto 96-well plates for flow cytometric staining. Cells were quantified using flow cytometry by adding equal numbers of 6-μm beads (BD, 345249). Migration indices indicate the number of migrated cells in the respective sample divided by the number of migrated cells in negative control samples containing unconditioned growth media.

Cellular viability staining

Tumor cells were plated in tissue culture flasks and irradiated or sham-treated as indicated above. At different time points after irradiation, all attached and detached tumor cells were collected and stained with 1:20 annexin V (BioLegend, 640941) and 1:40 7-Aminoactinomycin D (7AAD) (BioLegend, 420404) in a buffer solution containing 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 0.14 M NaCl, and 2.5 mM CaCl2.

Flow cytometry

Cells were transferred onto 96-well plates, washed in flow cytometry buffer (FB) containing 3% FCS, resuspended in FB containing 10% human AB serum and fluorochrome-labeled antibodies, and incubated on ice for 30 min. Cells were washed two times to remove excess nonbinding antibodies, incubated in 7AAD (BioLegend, #420404), and transferred into 5-ml polystyrene test tubes. Samples were acquired on a BD FACSCalibur or BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer depending on experiment. For identification of NK cells, all samples were gated on CD56+ CD3− 7AAD− cells. Antibodies used in this study are as follows: CD56-Allophycocyanin (APC) (HCD56, BioLegend, 318310), CD3-Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (HIT3a, BioLegend, 300306), CD3-Phycoerythrin/Cyanine7 (PE/Cy7) (SK7, BioLegend, 344815), CD16-PE (3G8, BioLegend, 302008), CD16-APC/Cy7 (B73.1, BioLegend, 360709), CXCR1-PE (8F1, BioLegend, 320608), CXCR2-PE (5E8/CXCR2, BioLegend, 320706), CD45-Brilliant Violet 510 (H130, BioLegend, 304035), isotype control mouse IgG1κ-PE (MOPC-21, BioLegend, 400140), and isotype control mouse IgG2bκ-PE (MPC-11, BioLegend, 4001312). Samples were analyzed using FlowJo 10.0.7.2 (FlowJo LLC).

ELISA and chemokine arrays

Secreted chemokines were quantified using ELISA (R&D, DY208) or flow cytometry–based multiplex bead arrays (BioLegend, BLD-740003) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Patient serum protein levels were determined using Fast Quant Human II and Human Angiogenesis antibody arrays (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot

Total protein isolation

Cells were washed with PBS in cell culture dishes and incubated with 1 ml radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer {50 mM tris per 175 cm2 [50 mM trisaminomethane (tris), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 2% NP-40, and 0.1% SDS]} for 10 min containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Cells were scraped, transferred to qia shredder (Qiagen, 79656), and centrifuged for 2 min at 13,000 rpm in a tabletop centrifuge. The flow-through was collected and centrifuged for another 10 min at 13,000 rpm. The supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Isolation of subcellular fractions

We used a subcellular fractionation protocol adopted and modified from Kwon et al. (57). Briefly, cells were detached using PBS containing 1 mM EDTA, washed and incubated for 10 min in buffer 1 [10 mM Hepes at (pH 7.9), 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl, and 10 mM sodium fluoride in ddH2O] containing protease and phosphatatase inhibitors on ice. Cells were then homogenized by passing the solution through a 26-gauge needle for 15 times and centrifuged for 10 min at 1000g, resulting in supernatant 1 and pellet 1. The supernatant 1 was transferred and centrifuged for 45 min at 16,000g at 4°C; the supernatant containing the cytosol fraction was then stored at −80°C until further analysis. Pellet 1 was incubated in buffer 2 [20 mM Hepes at (pH 7.9), 420 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 25% glycerol, and 10 mM sodium flouride] containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors overnight at 4°C. After 15 min centrifugation at 16,000g, supernatants containing nuclear proteins were collected and stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Western blot

Protein content was measured using a Bradford assay with a BSA (A9418-100G Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) standard curve. Samples were then diluted to equal concentrations of protein, and 10 μg per lane was denatured in Lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) sample buffer (NP0007, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and reducing agent (NP0004, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 95°C for 5 min and centrifuged at 2500 rpm in a tabletop centrifuge for 3 min at room temperature. Samples were then loaded on tris-glycine gels for electrophoresis and blotted on methanol-activated polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour with 5% BSA containing tris-buffered saline + 0.1% Tween (TBST) before incubation with primary antibodies in the same buffer overnight at 4°C. Membranes were then washed and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated secondary antibody in the same buffer solution for 1 hour at room temperature, washed, and incubated with LumiGlo (7003S, Cell Signaling Technology, Cambridge, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The membranes were then stripped for a maximum of two times and stained with loading control antibodies using the protocol above. Membranes were stripped by incubation in 2% SDS and 100 mM β-mercaptoethanole–containing buffer at 65°C for 25 min. At least one loading control was prepared per staining of tested proteins. Primary antibodies used for staining of tested proteins: p65 (6956T, Cell Signaling Technology, Cambridge, UK), IκB-α (4814 T, Cell Signaling Technology, Cambridge, UK), p21 (2947, Cell Signaling Technology, Cambridge, UK), phospho-p70–S6 kinase (9234T, Cell Signaling Technology, Cambridge, UK or MAB8963-SP, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), p70–S6 kinase (MAB8962-SP, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and LC3A/B (12741S, Cell Signaling Technology, Cambridge, UK). Loading control antibodies included proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (ab912, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), α-tubulin (2125S, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and β-actin (4967, Cell Signaling Technology, Cambridge, UK). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies included goat polyclonal anti-rabbit (7074S, Cell Signaling Technology, Cambridge, UK) and horse polyclonal anti-mouse (7076, Cell Signaling Technology, Cambridge, UK).

Quantitative reverse transcription–PCR

Murine lungs were isolated and transferred into RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific, AM7021) for RNA stabilization. Tissue was homogenized in buffer RLT (Qiagen, 74104) using the Tissue Lyser II (Qiagen). Cell lines were homogenized by direct resuspension in buffer RLT and repeated pipetting. RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, 74104) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Residual DNA was removed by DNAse I digestion. RNA purity was determined using a Nanodrop Fluorospectrometer. RNA was reverse-transcribed (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 18080093), and control reverse transcription reactions without reverse transcriptase (RT−) were prepared side by side to control for contaminating DNA. Cp values in RT− controls were generally higher than 35 or not detected, suggesting non-substantial DNA contamination. Real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR was performed using the Roche Molecular Diagnostics LightCycler System. Primers and probes were designed using ProbeFinder version 2.53 (Roche Molecular Diagnostics). Primers and probes included the following: CXCL8_Forward: AGACAGCAGAGCACACAAGC, CXCL8_Reverse: ATGGTTCCTTCCGGTGGT, CXCL8_Probe: GCCAGGAA; GAPDH_Forward: AGCCACATCGCTCAGACAC, GAPDH_Reverse: GCCCAATACGACCAAATCC, GAPDH_Probe: TGGGGAAG. Gene expression was determined by calculating 2^(Cphousekeeping − CpCXCL8).

Whole blood transcriptomics

Five milliliters of EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples was stored at −20°C in RNAlater for RNA stabilization. Total RNA was isolated using the RiboPure RNA Purification Kit, blood (Thermo Fisher Scientific, AM1928) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Globin mRNA was depleted using the GLOBINclear kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA quality was determined using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer System. A total of 500 ng of globin mRNA–depleted RNA was reverse-transcribed and amplified using the Low RNA Input Linear Amplification PLUS, One Color (Agilent). Gene expression was determined using the Whole Human Genome 4 × 44k Oligo Microarray (Agilent, 5188-5339). To estimate circulating leukocyte subsets, we used the html implementation of the RNA deconvolution algorithm CIBERSORT using nonnormalized Agilent Microarray data according to the developers’ instructions and the LM22 signature gene file (https://cibersort.stanford.edu/) (21). The CIBERSORT algorithm was run with 1000 permutations, and the P value (two-tailed) for RNA deconvolution was <0.01 in every sample. Total NK cell numbers were calculated as the sum of activated and resting NK cells.

To calculate gene expression signature expression of NK cell subsets, we used CD56dim and CD56bright NK cell subset–specific genes derived from an scRNA-seq study (28). Signature scores were calculated as the average z-scored gene expression of highly up-regulated genes in CD56dim and CD56bright peripheral blood NK cells.

Fluorescence microscopy

For cell culture fluorescence microscopy studies, tumor cells were detached using 1 mM EDTA in PBS, washed, resuspended in complete growth medium, irradiated using a 137Cs source, placed onto autoclaved coverslips in 6-well plates, and incubated at 37°C 5% CO2. After 24 hours, cells were fixed using 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS and permeabilized with Triton X-100. Cells were incubated with Image-iT FX Signal Enhancer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #I36933), washed, and blocked for 30 min with 3% BSA in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100. Cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-p65 antibody (6956, Cell Signaling Technology), washed, and incubated for 1 hour with secondary antibody (A-11029, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 3% BSA in PBS at room temperature. Cells were washed and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) before embedding them in Fluoromount G (0100-01, SouthernBiotech). Images were acquired at ×20 (quantification) or ×60 (example pictures) magnification with equal microscope settings and exposure times using a Nikon Eclipse E600 or Cell Observer (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) microscope. At least three different fields were acquired per biological replicate and experimental condition, generally containing >50 cells each. Integrated density of p65 staining in each nucleus was determined in a semiautomated manner using ImageJ 1.51j8 (W. Rasband, National Institutes of Health, USA).

SA-β-Gal staining

Cells were plated 1 day before the experiment into individual wells of 24-well plates containing sterile coverslips and irradiated in the attached state as indicated. Four days later, cells were fixed and subsequently incubated overnight at 37°C in the staining solution containing X-gal at pH 6.0 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9860S). Cells were thoroughly washed and incubated in DAPI (1 μg/ml) in H2O solution for 15 min. Coverslips were mounted on microscope slides and analyzed with brightfield and fluorescence microscopy. Five random fields per coverslip were recorded, including ca. >100 cells per experimental condition. Cells were identified by DAPI signal, and perinuclear SA-β-Gal staining was quantified in a semiautomated manner using ImageJ v.1.52d for Windows 10 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, USA).

Murine xenograft tissue analysis

For quantification of S100-positive SK-Mel-28 melanoma metastases by immunofluorescence microscopy, 3- to 4-μm-thick paraffin-embedded mouse lungs were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and dried, and antigens were retrieved using proteinase K (Roche, 3115844) for 10 min at 37°C. Sections were washed with TBST (pH 7.4 with 0.05% Tween 20) and incubated with a primary S100 antibody (1:50; Dako, Z0311) in TBST containing 2% dry milk powder for 2 hours at 37°C. After washing thrice in TBST, sections were incubated in TBST containing 0.5% BSA and a donkey anti-rabbit CF594 antibody (1:200; Biotium, #20152). Sections were washed thrice in TBST again and incubated in distilled water containing DAPI (10 mg/ml, 1:2000; Biotium, #40043). Sections were mounted in mounting medium (Dako, #S3023) and imaged using a Zeiss Axioscan Z.1 microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). Images were analyzed using Zen Blue v3.4 (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany), and S100+ metastases were quantified by a blinded investigator. At least 23-mm2 lung area was quantified using up to three tissue sections per mouse.

For immunohistochemistry staining, 7-μm sections were deparaffinized with Roticlear (Carl Roth) and ethanol serial dilutions. Antigen retrieval was performed with 10 mM citrate buffer for 30 min at 97°C. Peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation in 3% H2O2 in methanol. After washing, slides were blocked with Protein Block (X0909, Agilent) and incubated with CXCL8 antibody (2.5 μg/ml; AF208-NA, RnD) overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed, incubated with diluted secondary antibody (1:200; ab97110, Abcam) for 30 min at 37°C, washed, and stained using the 3,3’-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) Peroxidase (HRP) Substrate Kit (SK-4100 Vector Laboratories). Slides were counterstained using hematoxylin and embedded using Eukitt (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) mounting medium. Two to four slides per mouse were scanned completely using a Zeiss Axio Scan.Z1 microscope at ×20 magnification, and CXCL8-positive lung metastases were quantified manually in a systematic manner using the Zen Blue 2.3 lite (Carl Zeiss) software without considering areas of nonspecific staining, tissue borders, and big vessels. Slides stained with secondary antibody only were prepared as controls.

Clinical trial

Sixty-six locally advanced PDAC patients undergoing RCTX with intensity-modulated RT (IMRT) combined with gemcitabine and cetuximab were randomized to receive maintenance therapy with either gemcitabine and cetuximab or gemcitabine alone in an open-label randomized controlled phase 2 clinical trial (ISRCTN56652283). The complete study protocol with inclusion and exclusion criteria has been published with trial initiation and can be found online (52). An overview of the treatment schedule can be found in Fig. 1A. Briefly, IMRT with integrated boost was delivered in 25 fractions over 5 weeks with a median total dose of 54 Gy delivered to the gross tumor volume and 45 Gy to the clinical target volume (CTV). CTV comprised left gastric, hepatic, superior pancreatic, splenic, pyloric, superior mesenteric, and pancreaticoduodenal lymph nodes. Gemcitabine was administered weekly at 300 mg/m2 for a total of eight doses. Cetuximab was administered weekly 250 mg/m2 (loading dose, 400 mg/m2) for 5 doses (study arm A) or 18 doses (study arm B). EDTA and serum blood samples were obtained and on days −8, −7, 0, 14, 35, and 62 relative to start of irradiation and was available for 37 of the 66 patients. Inclusion criteria included the following: age equal or greater than 18 years, primary inoperable locally advanced PDAC, no evidence of metastatic disease, hemoglobin (Hb) > 10.0 g/%, white blood cells (WBCs) > 3000 cells/mm3, platelets > 100,000 cells/mm3, performance status Karnofsky ≥ 70, no acute infections at the time of therapy initiation, patient must be able to give informed consent, and patient has given informed consent. Exclusion criteria included the following: active infection, liver function impairment, pregnancy or breastfeeding, metastatic disease, other severe systemic disease, second malignancy (except carcinoma in situ of the cervix uteri and basal cell carcinoma of the skin after adequate oncologic treatment), any other experimental treatment 4 weeks before study inclusion, known positive HACA (human antichimeric antibody), known allergy against extrinsical proteins, previous antibody therapy, allergy against intravenous contrast agent [for computed tomography (CT) scans], previous chemo- and/or radiation treatment or EGFR inhibitor therapy for pancreatic cancer, lack of compliance, inability to follow the instructions given by the investigator or the telephone interviewer (insufficient command of language, dementia, and lack of time), and lack of informed consent.

Patients were randomized after giving informed consent using sealed opaque envelopes and a software generated (SAS Version 8.2) block randomized list generated using by the investigator (C.T.). Patient number was predefined as indicated in the study protocol and based on sample size estimation (end point overall survival, α = 0.05 and 1-β = 0.8) (52). All available blood samples were included in the analysis. Overall survival was defined as a secondary end point in the study protocol (52), the primary end point was safety, and has been reported elsewhere (53). As an open-label trial, no blinding was performed. Subject demographics such as age and sex are listed in table S1.

Pancreatic cancer surgical specimen tissue analysis

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded primary PDAC specimens of patients who underwent neoadjuvant RCTX or of chemo- and RT naïve patients were provided by the DIN EN ISO/IEC 17020 certified EPZ Pancobank at the Department of Surgery, University Hospital Heidelberg and by the Tissue Bank of the National Center of Tumor Diseases, Heidelberg, Germany in accordance with the regulations of the tissue bank and the approval of the Ethics Committee of Heidelberg University (ethic votes 301/2001 and S-708/2019). Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks were sectioned, hematoxylin and eosin–stained, and reviewed by a board-certified pathologist for sample quality using a 5-point rating scale (1: ideal quality, 2: good quality, 3: sufficient quality, 4: suboptimal quality, 5: poor quality). Only samples with adequate quality (scores 1 to 3) and at least 10% tumor cells and adequate quality were used for downstream analysis and immunohistochemically stained for Nkp46 (1:100; R&D Systems, MAB1850). The complete staining procedure was carried out on a BOND-Max (Leica, Germany) using a Bond Polymer Refine Detection kit (for DAB). Whole-slide images were acquired using an AT2 slide scanner (Leica Germany). Regions of interest were manually delineated by the observer in the software as tumor, stroma, and fat. These outlined areas were used for the digital analysis. The density and distribution of immune cells in complete microscopic images of full tissue sections were semiautomatically analyzed using Visiopharm Integrator System software (Visiopharm A/S, Hoersholm, Denmark).

scRNA-seq data analysis

Preprocessing

scRNA-seq data of PDAC whole-tumor single-cell lysates and normal pancreatic tissue generated with the 10x Genomics Single-Cell 3′ v2 platform were obtained from Peng et al. (26). FASTQ files were downloaded from the Genome Sequence Archive (CRA001160) and aligned to the hg38 human genome reference using the Sequence Quality Control (SEQC) preprocessing pipeline with default parameters (58). One sample repeatedly failed to align to the hg38 reference genome despite intact md5 checksums and was therefore removed from downstream analysis. SEQC distinguishes empty drops from true cells using the cumulative distribution of total molecule counts per cell. Moreover, it removes cells with high mitochondrial gene expression (>20% of total molecule counts per cell) and cells that express a low number of unique genes. This resulted in a total of 201,470 cells passing SEQC quality control. All downstream analyses were performed using AnnData v.0.7.4 and the scanpy package v.1.6.0 (59).

We performed an additional step of empty droplet removal using the EmptyDrops package (60), which defines true cells as cells which expression profile significantly deviate from the average expression profile of all putative cells/droplets. EmptyDrops called 3.59% as empty droplets. Because we wanted to be confident in the cell populations defined in this study not to contain empty droplets, we added an additional layer to the empty drops algorithm to remove residual empty droplets. We clustered the scRNA-seq data using the scanpy implementation of PhenoGraph (k = 10) (61). Clusters were removed if they met the following criteria: (i) They contained >2 times the proportion of empty droplets found in the overall cell population, and (ii) the proportion of empty droplets in a cluster significantly deviated from a uniform distribution as determined by the scipy implementation of chi square test and the Benjamini and Hochberg method with a q < 0.05 considered statistically significant. As a sanity check, we manually confirmed a granular gene covariance structure in all clusters remaining in the dataset for downstream analysis (164 genes × 850 cells). Mitochondrial and ribosomal genes were removed using a manually curated list of 218 mitochondrial and ribosomal genes (data S1). To call putative cellular doublets, we used the DoubletDetection package (10.5281/zenodo.2658729, P value threshold = 1 × 10−16, voter_thresh = 0.05). None of the remaining cell populations expressed marker gene combinations, suggesting heterotypic doublets (e.g., CD3E/F/G and CD19). This resulted in a total of 155,723 single cells that were used for downstream analyses.

Clustering analysis

Principal components were computed on the top 10,000 highly variable genes and leukocytes markers indicated in fig. S3C (all cells) or top 15,000 hv genes and leukocytes markers indicated in fig. S4D (leukocyte subset) (subset leukocytes + leukocyte markers in fig. S4D). We always included biologically relevant marker genes in the genes used for clustering because these genes may be removed in the highly variable gene selection step, resulting in merging of biologically distinct populations in the same clusters. The number of highly variable genes was set to a number of genes where subpopulations of interested could be resolved by clustering.

Clustering was performed using PhenoGraph, and the number of principal components used for clustering was selected as the least number of principal components accounting for >20% of the observed variance. The minimal number of principal components used for PhenoGraph clustering was defined as the kneepoint of the variance ratio versus 100 principal components curve as calculated by the kneed package on 100 principal components versus the explained variance ratio (https://github.com/arvkevi/kneed, v.0.7.0). For the PhenoGraph k parameter, parameters between k = 10 and k = 100 in steps of 10 were tested, and k was set to resolve relevant cell populations while the clustering remained stable in a window around the the chosen k parameter as determined by adjusted rand index. This resulted in a parameter of k = 60 to subset leukocytes from all viable cells and k = 30 to dissect NK cells from all leukocytes.

Normalization

Whole-tumor single-cell suspension RNA sequencing count matrices were normalized so that all cells’ library sizes equaled the median library size of the raw data using the scanpy.pp.normalize_total function. The data were then log1p-transformed using the scanpy.pp.log1p function. After subsetting leukocytes by the strategy indicated below, cells were assigned their raw count values and renormalized using the scran package. The scran package normalizes the data using cell cluster–specific size factors and thereby circumvents a major problem of normalizing cells with biologically apparent differences in cell and library size to equal library sizes, creating artificial differential gene expression that can result in artifacts in downstream analyses such as skewed grouping in clustering (62, 63).

Cell type annotations

Cell type annotation for whole-tumor single-cell suspension RNA sequencing data was performed using a manually curated panel of marker genes shown in fig. S4C to subset leukocytes. Leukocytes were then annotated using the curated marker gene panel indicated in Fig. 5D.

Visualizing gene expression

Because droplet-based scRNA-seq data are sparse due to frequent gene drop-out, the normalized count matrix was imputed using the scanpy implementation of Markov Affinity–based Graph Imputation of Cells v0.1.1 (MAGIC, t = 3) (64) for visualization purposes. Imputed gene expression data were either presented as a color overlay in the scanpy implementation of Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction (UMAP) or as heatmaps showing mean gene expression z scores per cluster with genes z-scored across cells.

Differential gene expresssion

Differential gene expression was computed pairwise between groups of interest with the diffxpy package (v 0.7.4; htttps://github.com/theislab/diffxpy). A negative binomial distribution generalized linear model was fitted to raw count data of both groups, and differential gene expression was calculated using Wald’s test implemented in the diffxpy.test.two_sample function.

Gene set enrichment analysis