Abstract

Recent observations of novel spin-orbit coupled states have generated interest in 4d/5d transition metal systems. A prime example is the state in iridate materials and α-RuCl3 that drives Kitaev interactions. Here, by tuning the competition between spin-orbit interaction (λSOC) and trigonal crystal field (ΔT), we restructure the spin-orbital wave functions into a previously unobserved state that drives Ising interactions. This is done via a topochemical reaction that converts Li2RhO3 to Ag3LiRh2O6. Using perturbation theory, we present an explicit expression for the state in the limit ΔT ≫ λSOC realized in Ag3LiRh2O6, different from the conventional state in the limit λSOC ≫ ΔT realized in Li2RhO3. The change of ground state is followed by a marked change of magnetism from a 6 K spin-glass in Li2RhO3 to a 94 K antiferromagnet in Ag3LiRh2O6.

The spin-orbital quantum state is modified by tuning the spin-orbit coupling vs. trigonal lattice distortion.

INTRODUCTION

An exotic quantum state in condensed matter physics is the state in honeycomb iridate materials that leads to the Kitaev exchange interaction (1–6). The state is a product of strong spin-orbit coupling (SOC) in heavy Ir4+ ions that splits the t2g manifold into a quartet and a doublet. With five electrons in the 5d5 configuration, iridates have one electron in the spin-orbital state that satisfies the prerequisites of the Kitaev interaction in a honeycomb lattice as shown by earlier studies (1–5). Here, we introduce a new spin-orbital state, , which we have engineered by tuning the interplay between two energy scales: the SOC (λSOC) and the trigonal crystal field splitting (ΔT). The state drives Ising instead of Kitaev interactions. Although the Ising limit has been discussed in several theoretical studies (7–10), a transition between the Kitaev and Ising limits has not been demonstrated until now. It has been theoretically predicted that the Kitaev limit in Na2IrO3 can be tuned to an Ising limit under uniaxial physical pressure (8), but the required pressure has not been achieved. The Ising limit is relevant to MPS3 (M = Mn, Fe, and Ni) compounds (10); however, a transition from the Ising to Kitaev limit has not been discussed in those materials, even at a theoretical level. This work presents the first observation of a transition between the Kitaev and Ising limits in the same material family.

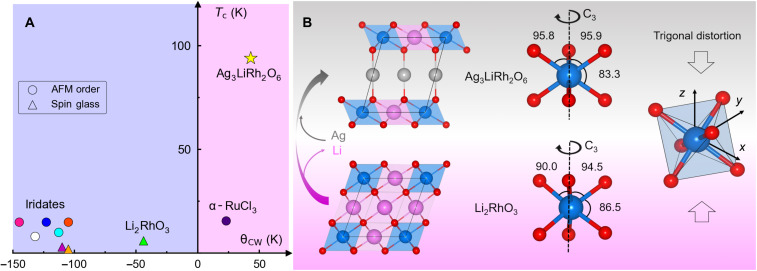

Our experiment was motivated by a survey of the average Curie-Weiss temperature () and the antiferromagnetic (AFM) or spin-glass transition temperatures (TN/Tg) of the two-dimensional (2D) iridium-, rhodium-, and ruthenium-based Kitaev materials (Fig. 1A and table S1). These compounds can be categorized into two groups. The first-generation Kitaev magnets include α-Li2IrO3, Na2IrO3, Li2RhO3, and α-RuCl3, synthesized by conventional solid-state methods (11–19). The second-generation materials, such as H3LiIr2O6, Cu3NaIr2O6, and Ag3LiIr2O6, have been synthesized recently by exchanging the interlayer alkali (Li+ and Na+) in the first-generation compounds with H+, Cu+, and Ag+ using topochemical reactions (20–26). Both the first- and second-generation iridates appear in the same region of the phase diagram in Fig. 1A. The 4d systems, namely, Li2RhO3 and α-RuCl3, appear to be shifted horizontally but not vertically from the iridate block. Despite theoretical predictions of diverse magnetic phases (27, 28), it seems that all 2D Kitaev materials studied so far aggregate in the same region of the phase diagram with TN ≤ 15 K and a state. This observation prompted us to experimentally investigate the possibility of tuning the local spin-orbital state and the magnetic ground state in the same material family.

Fig. 1. Phase diagram.

(A) Critical temperature (Tc) plotted against the Curie-Weiss temperature () using the data in table S1 for polycrystalline 2D Kitaev materials. Circles and triangles represent AFM and spin-glass transitions, respectively. The iridate materials are (from left to right) Cu3LiIr2O6, Ag3LiIr2O6, Na2IrO3, Cu3NaIr2O6, Cu2IrO3, H3LiIr2O6, and α-Li2IrO3. (B) Structural relationship between the first- and second-generation Kitaev systems, Li2RhO3 and Ag3LiRh2O6, with enhanced trigonal distortion in the latter, as evidenced by the change of bond angles after cation exchange.

We focused on rhodate (4d) systems where the SOC is weaker than in the iridate (5d) systems, and ΔT has a better chance to compete with λSOC. Evidence of such competition can be found in earlier density functional theory (DFT) studies of the honeycomb rhodates, where a high sensitivity of the magnetic ground state to structural parameters has been reported (18, 29). To enhance ΔT, we replaced the Li atoms between the honeycomb layers of Li2RhO3 with Ag atoms and synthesized Ag3LiRh2O6 topochemically (Fig. 1B). The change of interlayer bonds leads to a trigonal compression along the local C3 axis (Fig. 1B). Using crystallographic refinement (fig. S1 and tables S2 and S3), we determined the bond angles within the local octahedral (Oh) environments of both compounds and quantified the trigonal distortion by calculating the bond angle variance (9) , where m = 12 and θ0 = 90∘. In an ideal octahedron, σ = 0. In Ag3LiRh2O6, we found σ = 6.1(1)∘, nearly twice the σ = 3.1(1)∘ in Li2RhO3. It has been noted in earlier theoretical works (7, 8) that a trigonal distortion can reconstruct the spin-orbital states and lead to new magnetic regimes; however, it has also been noted that such a regime may not be accessible in iridate materials due to the overwhelmingly strong SOC. As shown in Fig. 1A, we induced such a change of regime between Li2RhO3 and Ag3LiRh2O6 using chemical pressure.

RESULTS

Magnetic properties

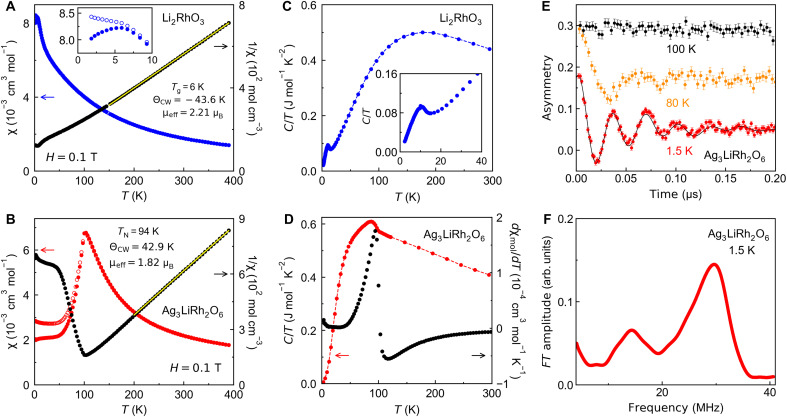

A small peak at Tg = 6.0(5) K in Li2RhO3 with a splitting between the zero-field-cooled (ZFC) and field-cooled (FC) susceptibility data [χ(T) in Fig. 2A] confirms the spin-glass transition as reported in earlier works (18, 30, 31). In stark contrast, Ag3LiRh2O6 exhibits a robust AFM order with a pronounced peak in χ(T) and without ZFC/FC splitting (Fig. 2B). The small difference between the ZFC and FC curves at low temperatures is due to a small amount of stacking faults, which are carefully analyzed in fig. S2. A Curie-Weiss analysis in Fig. 2B yields an effective moment of 1.82 μB and a K, consistent with a prior report (32). A positive despite an AFM order suggests that χ(T) must be highly anisotropic, which is the case in materials with A-type or C-type AFM order. For example, Na3Ni2BiO6 has a C-type AFM order [AFM intralayer and ferromagnetic (FM) interlayer] with TN = 10.4 K and K (33).

Fig. 2. Magnetic characterization.

Magnetic susceptibility plotted as a function of temperature and Curie-Weiss analysis presented in (A) Li2RhO3 (blue) and (B) Ag3LiRh2O6 (red). The ZFC and FC data are shown as full and empty symbols, respectively. Heat capacity as a function of temperature in (C) Li2RhO3 and (D) Ag3LiRh2O6. The black circles in (D) show the derivative of magnetic susceptibility with respect to temperature. (E) μSR asymmetry plotted as a function of time in Ag3LiRh2O6. For clarity, the curves at 100 and 80 K are offset with respect to the 1.5 K spectrum. The solid line is a fit to a Bessel function (see the Supplementary Materials for details). (F) Fourier transform of the μSR spectrum at 1.5 K showing two frequency components.

Both the spin-glass transition in Li2RhO3 and the AFM transition in Ag3LiRh2O6 are marked by peaks in the heat capacity in Fig. 2 (C and D). The heat capacity peak of Ag3LiRh2O6 is visible despite the large phonon background at high temperatures, confirming a robust AFM order. We report TN = 94(3) K using the peak in dχ/dT, which is close to the peak in the heat capacity (Fig. 2D). TN in Ag3LiRh2O6 is nearly an order of magnitude larger than the transition temperature in any other 2D Kitaev material to date.

To obtain information about the local field within the magnetically ordered state of Ag3LiRh2O6, we turned to muon spin relaxation (μSR) experiments. In Fig. 2E, the time-dependent μSR asymmetry curves in zero applied magnetic field show the appearance of spontaneous oscillations below 100 K, confirming the long-range magnetic order. The asymmetry spectrum at 1.5 K fits to a modified zeroth-order Bessel function (34), with the form of the fitting function indicating noncollinear incommensurate magnetic ordering (see the Supplementary Materials for details). As shown in Fig. 2F, the Fourier transform of the 1.5 K spectrum shows two peaks at 12 and 31 MHz, which we have modeled using a two-component expression. Each component has a distribution of local fields between a Bmin and Bmax, indicating incommensurate ordering (table S4). The center of distribution (Bmin + Bmax)/2 is shifted from zero, indicating a noncollinear order (34). The dominant frequency of 31 MHz in Fig. 2F corresponds to a maximum internal field of 0.231 T at the muon stopping site (using ω = γμB with the muon gyromagnetic ratio γμ = 851.6 Mrad s−1 T−1), which is an order of magnitude larger than the internal field of 0.015 T extracted from μSR in Li2RhO3 (31). The marked change of magnetism between Li2RhO3 and Ag3LiRh2O6 in response to mild trigonal distortion, with an order-of-magnitude increase in both TN and internal field, implies a novel underlying interaction in the ground state.

Theoretical wave functions

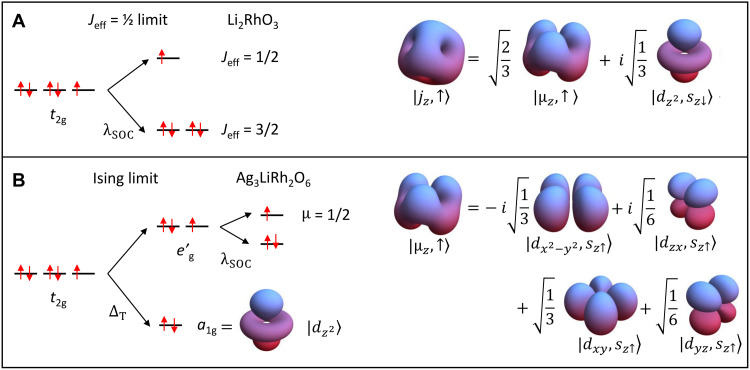

The drastic change of magnetic behavior between Li2RhO3 and Ag3LiRh2O6 originates from a fundamental change of the spin-orbital quantum state (Fig. 3). Both Li2RhO3 and Ag3LiRh2O6 have Rh4+ in the 4d5 configuration, corresponding to one hole in the t2g manifold. Assuming that both compounds are in the Mott insulating regime (fig. S3), their low-energy physics should be described by a Kramers doublet per Rh4+ ion; i.e., they are effective spin- systems. However, the nature of the Kramers doublet may be considerably different depending on the interplay between λSOC and ΔT. We illustrate this by considering two limits: the Jeff = 1/2 limit for λSOC ≫ ΔT relevant to Li2RhO3 (Fig. 3A) and the Ising limit for ΔT ≫ λSOC relevant to Ag3LiRh2O6 (Fig. 3B). The wave functions of the low-energy Kramers doublet can be found in both limits using perturbation theory. The Kramers doublet in the Jeff = 1/2 limit (λSOC ≫ ΔT) comprises the following two states (Fig. 3A)

| (1) |

where {∣μz,↑〉, ∣μz,↓〉} are defined in Eq. 2 below. The Jeff = 1/2 limit has been discussed extensively in the literature, and sizable Kitaev interactions have been proposed for materials in this limit such as the honeycomb iridates (1–4), α-RuCl3 (16), and Li2RhO3 (29–31). The only difference between Eq. 1 and prior works (4) is that we choose the z axis to be normal to the triangular face of the octahedron (Fig. 1B) instead of pointing at the apical oxygens.

Fig. 3. Wave functions.

(A) The Jeff = 1/2 limit, realized in Li2RhO3, where λSOC ≫ ΔT. The probability density is visualized for the isospin-up wave function. (B) The Ising limit, realized in Ag3LiRh2O6, where ΔT ≫ λSOC. The probability density is visualized for the spin-up wave function. Notice the cubic and trigonal symmetries of the Jz and μz orbitals, respectively.

In the Ising limit (ΔT ≫ λSOC), the trigonal distortion leads to new Kramers doublet states (Fig. 3B)

| (2) |

Note that the states {∣jz,↑〉, ∣jz,↓〉} are not orthogonal to the states {∣μz,↑〉, ∣μz,↓〉}, despite being in opposite limits.

The trigonal splitting energy scale ΔT is known to split the sixfold degenerate t2g levels (including spin degrees of freedom) into a twofold a1g manifold and a fourfold manifold (Fig. 3B) (10). Choosing and directions pointing toward oxygen atoms as shown in Fig. 1B, the orbital wave functions are found to be ∣dz2〉 for a1g (Fig. 3B) and {∣τz,↑〉, ∣τz,↓〉} for

| (3) |

In the materials under consideration, the trigonal distortion is a compression along the axis (Fig. 1B) that lowers the energy of the a1g level (Fig. 3B). Thus, for the 4d5 configuration, one should focus on the fourfold manifold. Unlike in the eg manifold, the SOC is not completely quenched in the manifold. We show, in the Supplementary Materials, that the d-orbital angular momentum operator , after projection into the manifold, becomes

| (4) |

where τx,y,z are the pseudospin Pauli matrices. We therefore have, in the manifold

| (5) |

Namely, λSOC further splits the manifold into two Kramers doublets: τy anti-aligned with sz or τy aligned with sz. The former doublet has a lower energy, so the latter doublet is half-filled in the 4d5 configuration. Last, the low-energy effective spin- states in the Ising limit are

| (6) |

which are nothing but the states written in Eq. 2 and illustrated in Fig. 3B.

The exchange couplings for the effective μ spins are expected to have the Ising anisotropy (easy-axis along the direction). To understand its origin, one may consider exchange interactions like between two Rh sites i, j in the absence of the spin-orbit interaction. After λSOC is turned on, the needs to be projected onto the Kramers doublet {∣μz,↑〉, ∣μz,↓〉} at low energies. Only the term JSi,zSj,z survives after the projection. In addition, the g factor of the effective μ spins in a magnetic field is also expected to be highly anisotropic. For example, the effective μ spins do not couple with a magnetic field along the (or ) axis in a linear fashion in this limit. A direct measurement of the magnetic response with respect to the field direction is not possible at this stage because single crystals of Ag3LiRh2O6 are not available. However, indirect evidence of such anisotropic interactions may be the positive Curie-Weiss temperature in polycrystalline samples of Ag3LiRh2O6 (Fig. 2B) that indicates FM interactions despite the AFM ordering. Such a behavior has been reported in Na3Ni2BiO6 and attributed to a C-type AFM order where the coupling within the layers is AFM and between the layers is FM (33).

Spectroscopic evidence

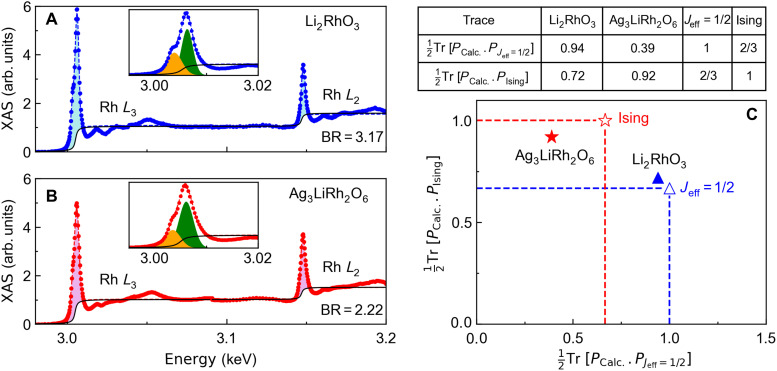

We provide spectroscopic confirmation of the above picture by measuring the branching ratio using x-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). Figure 4A shows the XAS data from a Li2RhO3 sample with the Rh L3 and L2 edges near 3.00 and 3.15 keV, respectively. The branching ratio, BR = I(L3)/I(L2) = 3.17(1), is evaluated by dividing the shaded areas under the L3 and L2 peaks in Fig. 4A. A similar analysis in Ag3LiRh2O6 yields BR = 2.22(1) (Fig. 4B). The branching ratio is related to the SOC through BR = (2 + r)/(1 − r), where r = 〈L · S〉/nh, with nh being the number of holes in the 4d shell (35, 36). Using nh = 5 for Rh4+, we obtain 〈L · S〉 = 1.40 in Li2RhO3 and 0.34 in Ag3LiRh2O6. This is consistent with the above theoretical picture based on λSOC ≫ ΔT and the Jeff limit in Li2RhO3 compared to ΔT ≫ λSOC and the Ising limit in Ag3LiRh2O6.

Fig. 4. X-ray absorption spectroscopy.

(A) XAS data from Rh L2,3 edges of Li2RhO3. The data were modeled with a step and two Gaussian functions for the L3 edge (inset) and one Gaussian function for the L2 edge. (B) Similar data and fits for the Rh L2,3 edges of Ag3LiRh2O6. (C) Theoretically calculated traces of projector products are tabulated and plotted for both the ideal limits (empty symbols) and real materials (full symbols).

Note that the spectroscopic value of 〈L · S〉 is small but nonvanishing in Ag3LiRh2O6. The fine structure of Rh L edge with a shoulder near the L3 peak (inset of Fig. 4B) that is absent in the L2 peak confirms a finite SOC in Ag3LiRh2O6 (37). As illustrated in Fig. 3B, a weak SOC is necessary to split the levels. The fine structure of the Rh L3 edge can be fitted to two Gaussian curves in both Li2RhO3 and Ag3LiRh2O6 (insets of Fig. 4, A and B). A higher ratio between the two Gaussian areas in Ag3LiRh2O6 (2.42) than in Li2RhO3 (1.53) is consistent with a weaker SOC in the former. Supporting information about the Ag L edge is provided in fig. S4 to confirm the Ag+ oxidation state (38, 39).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that a competition between SOC and trigonal distortion could tune a honeycomb structure between the Kitaev () and Ising () limits. Our magnetization, μSR, and XAS data suggest that Li2RhO3 is closer to the Jeff limit, whereas Ag3LiRh2O6 is closer to the Ising limit. We calculated the ideal wave functions and visualized them in Fig. 3. However, a realistic material is generally situated on a spectrum between these two ideal limits. For example, minor lattice distortions (e.g., monoclinic) can further break the trigonal point group symmetry and perturb the ideal wave function.

To make our theoretical discussion more realistic, we calculated the band structure of Li2RhO3 and Ag3LiRh2O6 from first principles and obtained a real-space tight-binding model for each compound. Details of the electronic structure calculations in the presence of Hubbard-U, SOC, and zigzag magnetic ordering are presented in figs. S5 and S6 and table S5. The full orbital content of the energy eigenstates was characterized using a combination of Quantum Espresso and Wannier90 software (40–42). This allowed us to quantitatively investigate the regimes being realized in Li2RhO3 and Ag3LiRh2O6. Specifically, given a Kramers doublet ∣ψ1〉 and ∣ψ2〉, we defined the projectors

| (7) |

For example, PJeff=1/2 and PIsing are projectors defined using the Kramers doublets in the Jeff = 1/2 limit (Eq. 1) and the Ising limit (Eq. 2), respectively. We then compute the traces and . The results are tabulated and visualized in Fig. 4C. These traces would be unity if the calculated system was in the ideal Jeff or Ising limit. Figure 4C locates Li2RhO3 and Ag3LiRh2O6 in the vicinity of the Jeff = 1/2 and Ising (μ = 1/2) limits, respectively.

Our combined experimental and theoretical results show how to change the fabric of spin-orbit coupled states and markedly change the magnetic behavior of the Kitaev materials. Despite theoretical proposals for a diverse global phase diagram, the current Kitaev systems are all in the Jeff limit (1–5, 14, 16, 43–45). Finding an outlier, such as Ag3LiRh2O6, in the phase diagram (Fig. 1A) provides the first glimpse at the diversity of magnetic phases that can be engineered using topochemical methods. Specifically, the interplay between the Kitaev and Ising limits will be a fruitful venue to search for novel noncollinear magnetic orders beyond the familiar Kitaev-Heisenberg paradigm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Material synthesis

Similar to other second-generation Kitaev magnets, Ag3LiRh2O6 is a metastable compound. It is synthesized through a topotactic cation-exchange reaction under mild conditions from the first-generation parent compound Li2RhO3.

| (8) |

Li2RhO3 was synthesized following prior published works (30, 31). To perform the topotactic exchange reaction, Li2RhO3 and AgNO3 powders were mixed and heated to 350∘C for 1 week. The excess AgNO3 was removed with deionized water.

Characterizations

Powder x-ray diffraction was performed using a Bruker D8 ECO instrument in the Bragg-Brentano geometry, using a copper source (Cu-Kα) and a LYNXEYE XE 1D energy-dispersive detector. The FullProf suite was used for the Rietveld analysis (46). Peak shapes were modeled with the Thompson-Cox-Hastings pseudo-Voigt profile convoluted with axial divergence asymmetry. Magnetization was measured using a Quantum Design MPMS3 with the powder sample mounted on a low-background brass holder. Both the electrical resistivity (four-probe technique) and heat capacity (relaxation time method) were measured on a pressed pellet using the Quantum Design PPMS Dynacool. Electron diffraction, high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), and annular bright-field STEM were performed using an aberration double-corrected JEM ARM200F microscope operated at 200 kV and equipped with a CENTURIOEDX detector, Orius Gatan charge-coupled device camera, and GIF Quantum spectrometer (47–49). The μSR measurements were performed in a continuous-flow 4He evaporation cryostat (T ≥ 1.5 K) at the general purpose surface-muon instrument (50) at the Paul Scherrer Institute, and the data were analyzed using the Musrfit program (51). A pressed disk of Ag3LiRh2O6 with diameter 12 mm and thickness 1.2 mm was wrapped in 25-μm silver foil and suspended in the muon beam to minimize the contribution from muons implanted in a sample holder or in the cryostat walls.

First-principles calculations

The electronic structures were computed using the open-source code Quantum Espresso (40, 41) with the experimental crystallographic information as the input. The calculation included SOC and zigzag magnetic ordering for both compounds, and the fully gapped states were achieved using a DFT + U method (52). To stabilize the noncollinear magnetic calculation, we used the norm-conserving pseudopotentials from PseudoDojo (53). For convergence reasons, we implemented the Perdew-Zunger functional in the calculation of Ag3LiRh2O6, while leaving the default Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional for Li2RhO3. To compare with the previous report of the insulating states in chemical formula Li2RhO3 (LRO) (18), we fixed the Hund’s coupling to J = 0.7 eV and tuned the Hubbard-U from 1 to 4 eV. Our results were consistent with the prior work. The real-space tight-binding functions (involving the Rh-4d and O-2p orbitals as well as Ag-4d orbitals for Ag3LiRh2O6) were derived from the band structure using maximally localized Wannier states implemented by the Wannier90 software (42). From here, tight-binding models for a single RhO6 cluster were constructed on the basis of the obtained real-space hopping parameters. The eigenstates of such a RhO6 cluster were used to compute 〈L · S〉 and the traces in Fig. 4.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy

X-ray absorption near-edge structure data at Rh and Ag L2,3 edges were collected at tender energy beamline 8-BM of the National Synchrotron Light Source II and at beamline 4-ID-D of the Advanced Photon Source, respectively. The Rh L2,3 data were collected in total electron yield mode using powder samples in a helium gas environment. The Ag L2,3 data were collected in partial fluorescence yield (PFY) mode with powder samples in vacuum. Silicon and nickel mirrors together with detuning of the second Si(111) monochromator crystal were used to reject high-energy harmonics. The PFY data were corrected for self-absorption (54).

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Valenti and Y. Li for fruitful discussions.

Funding: F.T. and F.B. acknowledge support from the NSF under grant no. DMR-1708929. Y.R. and X.H. acknowledge support from the NSF under grant no. DMR-1712128. This work is based, in part, on experiments performed at the Swiss Muon Source SμS, Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, Switzerland. This research used 8-BM of the National Synchrotron Light Source II, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Brookhaven National laboratory under contract no. DE-SC0012704. Work at the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the DOE of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under award no. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Author contributions: F.B. synthesized the materials, performed magnetic and thermodynamic measurements, and analyzed the data. O.I.L. performed TEM experiments. X.H. and Y.R. performed theoretical calculations. Y.D., G.F., and D.H. performed XAS experiments. C.W., H.L., and M.J.G. performed μSR experiments. F.T. conceptualized the project. All authors participated in writing.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials and permanently archived in Materials Data Facility (DOI: 10.18126/ar66-63gd, LINK: https://doi.org/10.18126/AR66-63GD).

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Tables S1 to S5

Figs. S1 to S6

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Crystallographic Information File (CIF) for Li2RhO3

Crystallographic Information File (CIF) for Ag3LiRh2O6

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Takagi H., Takayama T., Jackeli G., Khaliullin G., Nagler S. E., Concept and realization of Kitaev quantum spin liquids. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 264–280 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knolle J., Moessner R., A field guide to spin liquids. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 10, 451–472 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaloupka J., Jackeli G., Khaliullin G., Kitaev-Heisenberg model on a honeycomb lattice: Possible exotic phases in iridium oxides A2IrO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 027204 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackeli G., Khaliullin G., Mott insulators in the strong spin-orbit coupling limit: From Heisenberg to a quantum compass and Kitaev models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 017205 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim B. J., Jin H., Moon S. J., Kim J.-Y., Park B.-G., Leem C. S., Yu J., Noh T. W., Kim C., Oh S.-J., Park J.-H., Durairaj V., Cao G., Rotenberg E., Novel Jeff = 1/2 Mott state induced by relativistic spin-orbit coupling in Sr2IrO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 076402 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitaev A., Anyons in an exactly solved model and beyond. Ann. Phys. 321, 2–111 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khaliullin G., Orbital order and fluctuations in Mott insulators. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 160, 155–202 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhattacharjee S., Lee S.-S., Kim Y. B., Spin–orbital locking, emergent pseudo-spin and magnetic order in honeycomb lattice iridates. New J. Phys. 14, 073015 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haraguchi Y., Katori H. A., Strong antiferromagnetic interaction owing to a large trigonal distortion in the spin-orbit-coupled honeycomb lattice iridate CdIrO3. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 044401 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joy P. A., Vasudevan S., Magnetism in the layered transition-metal thiophosphates MPS3 (M = Mn, Fe, and Ni). Phys. Rev. B 46, 5425–5433 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh Y., Manni S., Reuther J., Berlijn T., Thomale R., Ku W., Trebst S., Gegenwart P., Relevance of the Heisenberg-Kitaev model for the honeycomb lattice iridates A2IrO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 127203 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehlawat K., Thamizhavel A., Singh Y., Heat capacity evidence for proximity to the Kitaev quantum spin liquid in A2IrO3 (A = Na, Li). Phys. Rev. B 95, 144406 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh Y., Gegenwart P., Antiferromagnetic Mott insulating state in single crystals of the honeycomb lattice material Na2IrO3. Phys. Rev. B 82, 064412 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plumb K. W., Clancy J. P., Sandilands L. J., Shankar V. V., Hu Y. F., Burch K. S., Kee H.-Y., Kim Y.-J., α-RuCl3: A spin-orbit assisted Mott insulator on a honeycomb lattice. Phys. Rev. B 90, 041112 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi Y., Okada T., Asai K., Katada M., Sano H., Ambe F., Moessbauer spectroscopy and magnetization studies of α- and β-ruthenium trichloride. Inorg. Chem. 31, 4570–4574 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koitzsch A., Habenicht C., Müller E., Knupfer M., Büchner B., Kandpal H., van den Brink J., Nowak D., Isaeva A., Doert T., Jeff description of the honeycomb Mott insulator α-RuCl3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 126403 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banerjee A., Bridges C. A., Yan J.-Q., Aczel A. A., Li L., Stone M. B., Granroth G. E., Lumsden M. D., Yiu Y., Knolle J., Bhattacharjee S., Kovrizhin D. L., Moessner R., Tennant D. A., Mandrus D. G., Nagler S. E., Proximate Kitaev quantum spin liquid behaviour in a honeycomb magnet. Nat. Mater. 15, 733–740 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazin I. I., Manni S., Foyevtsova K., Jeschke H. O., Gegenwart P., Valentí R., Origin of the insulating state in honeycomb iridates and rhodates. Phys. Rev. B 88, 035115 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Todorova V., Jansen M., Synthesis, structural characterization and physical properties of a new member of ternary lithium layered compounds—Li2RhO3. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 637, 37–40 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roudebush J. H., Ross K. A., Cava R. J., Iridium containing honeycomb delafossites by topotactic cation exchange. Dalton Trans. 45, 8783–8789 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abramchuk M., Ozsoy-Keskinbora C., Krizan J. W., Metz K. R., Bell D. C., Tafti F., Cu2IrO3: A new magnetically frustrated honeycomb iridate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 15371–15376 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bahrami F., Kenney E. M., Wang C., Berlie A., Lebedev O. I., Graf M. J., Tafti F., Effect of structural disorder on the Kitaev magnet Ag3LiIr2O6. Phys. Rev. B 103, 094427 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenney E. M., Segre C. U., Lafargue-Dit-Hauret W., Lebedev O. I., Abramchuk M., Berlie A., Cottrell S. P., Simutis G., Bahrami F., Mordvinova N. E., Fabbris G., McChesney J. L., Haskel D., Rocquefelte X., Graf M. J., Tafti F., Coexistence of static and dynamic magnetism in the Kitaev spin liquid material Cu2IrO3. Phys. Rev. B 100, 094418 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi S. K., Wang J., Arsenault A., Imai T., Abramchuk M., Tafti F., Singer P. M., Spin excitations of a proximate Kitaev quantum spin liquid realized in Cu2IrO3. Phys. Rev. X 9, 031047 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bahrami F., Lafargue-Dit-Hauret W., Lebedev O. I., Movshovich R., Yang H.-Y., Broido D., Rocquefelte X., Tafti F., Thermodynamic evidence of proximity to a Kitaev spin liquid in Ag3LiIr2O6. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 237203 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitagawa K., Takayama T., Matsumoto Y., Kato A., Takano R., Kishimoto Y., Bette S., Dinnebier R., Jackeli G., Takagi H., A spin–orbital-entangled quantum liquid on a honeycomb lattice. Nature 554, 341–345 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rusnačko J., Gotfryd D., Chaloupka J., Kitaev-like honeycomb magnets: Global phase behavior and emergent effective models. Phys. Rev. B 99, 064425 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rau J. G., Lee E. K.-H., Kee H.-Y., Generic spin model for the honeycomb iridates beyond the Kitaev limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 077204 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katukuri V. M., Nishimoto S., Rousochatzakis I., Stoll H., van den Brink J., Hozoi L., Strong magnetic frustration and anti-site disorder causing spin-glass behavior in honeycomb Li2RhO3. Sci. Rep. 5, 14718 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo Y., Cao C., Si B., Li Y., Bao J., Guo H., Yang X., Shen C., Feng C., Dai J., Cao G., Xu Z.-a., Li2RhO3: A spin-glassy relativistic Mott insulator. Phys. Rev. B 87, 161121 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khuntia P., Manni S., Foronda F. R., Lancaster T., Blundell S. J., Gegenwart P., Baenitz M., Local magnetism and spin dynamics of the frustrated honeycomb rhodate Li2RhO3. Phys. Rev. B 96, 094432 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Todorova V., Leineweber A., Kienle L., Duppel V., Jansen M., On AgRhO2, and the new quaternary delafossites AgLi1/3M2/3O2, syntheses and analyses of real structures. J. Solid State Chem. 184, 1112–1119 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seibel E. M., Roudebush J. H., Wu H., Huang Q., Ali M. N., Ji H., Cava R. J., Structure and magnetic properties of the α-NaFeO2-type honeycomb compound Na3Ni2BiO6. Inorg. Chem. 52, 13605–13611 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amato A., Dalmas de Réotier P., Andreica D., Yaouanc A., Suter A., Lapertot G., Pop I. M., Morenzoni E., Bonfà P., Bernardini F., De Renzi R., Understanding the μSR spectra of MnSi without magnetic polarons. Phys. Rev. B 89, 184425 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Laan G., Thole B. T., Local probe for spin-orbit interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 1977–1980 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laguna-Marco M. A., Haskel D., Souza-Neto N., Lang J. C., Krishnamurthy V. V., Chikara S., Cao G., van Veenendaal M., Orbital magnetism and spin-orbit effects in the electronic structure of BaIrO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 216407 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Groot F. M. F., Hu Z. W., Lopez M. F., Kaindl G., Guillot F., Tronc M., Differences between L3 and L2 x-ray absorption spectra of transition metal compounds. J. Chem. Phys. 101, 6570–6576 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolobov A. V., Rogalev A., Wilhelm F., Jaouen N., Shima T., Tominaga J., Thermal decomposition of a thin AgOx layer generating optical near-field. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 1641–1643 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Behrens P., Aßmann S., Bilow U., Linke C., Jansen M., Electronic structure of silver oxides investigated by AgL XANES spectroscopy. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 625, 111–116 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giannozzi P., Baroni S., Bonini N., Calandra M., Car R., Cavazzoni C., Ceresoli D., Chiarotti G. L., Cococcioni M., Dabo I., Corso A. D., de Gironcoli S., Fabris S., Fratesi G., Gebauer R., Gerstmann U., Gougoussis C., Kokalj A., Lazzeri M., Martin-Samos L., Marzari N., Mauri F., Mazzarello R., Paolini S., Pasquarello A., Paulatto L., Sbraccia C., Scandolo S., Sclauzero G., Seitsonen A. P., Smogunov A., Umari P., Wentzcovitch R. M., Quantum espresso: A modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giannozzi P., Andreussi O., Brumme T., Bunau O., Nardelli M. B., Calandra M., Car R., Cavazzoni C., Ceresoli D., Cococcioni M., Colonna N., Carnimeo I., Dal Corso A., de Gironcoli S., Delugas P., Di Stasio R. A. Jr., Ferretti A., Floris A., Fratesi G., Fugallo G., Gebauer R., Gerstmann U., Giustino F., Gorni T., Jia J., Kawamura M., Ko H.-Y., Kokalj A., Küçükbenli E., Lazzeri M., Marsili M., Marzari N., Mauri F., Nguyen N. L., Nguyen H.-V., Otero-de-la-Roza A., Paulatto L., Poncé S., Rocca D., Sabatini R., Santra B., Schlipf M., Seitsonen A. P., Smogunov A., Timrov I., Thonhauser T., Umari P., Vast N., Wu X., Baroni S., Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pizzi G., Vitale V., Arita R., Blügel S., Freimuth F., Géranton G., Gibertini M., Gresch D., Johnson C., Koretsune T., Ibañez-Azpiroz J., Lee H., Lihm J.-M., Marchand D., Marrazzo A., Mokrousov Y., Mustafa J. I., Nohara Y., Nomura Y., Paulatto L., Poncé S., Ponweiser T., Qiao J., Thöle F., Tsirkin S. S., Wierzbowska M., Marzari N., Vanderbilt D., Souza I., Mostofi A. A., Yates J. R., Wannier90 as a community code: New features and applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 32, 165902 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sears J. A., Chern L. E., Kim S., Bereciartua P. J., Francoual S., Kim Y. B., Kim Y.-J., Ferromagnetic Kitaev interaction and the origin of large magnetic anisotropy in α-RuCl3. Nat. Phys. 16, 837–840 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gretarsson H., Clancy J. P., Liu X., Hill J. P., Bozin E., Singh Y., Manni S., Gegenwart P., Kim J., Said A. H., Casa D., Gog T., Upton M. H., Kim H.-S., Yu J., Katukuri V. M., Hozoi L., van den Brink J., Kim Y.-J., Crystal-field splitting and correlation effect on the electronic structure of A2IrO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 076402 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clancy J. P., Gretarsson H., Sears J. A., Singh Y., Desgreniers S., Mehlawat K., Layek S., Rozenberg G. K., Ding Y., Upton M. H., Casa D., Chen N., Im J., Lee Y., Yadav R., Hozoi L., Efremov D., van den Brink J., Kim Y.-J., Pressure-driven collapse of the relativistic electronic ground state in a honeycomb iridate. npj Quantum Mater. 3, 35 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodríguez-Carvajal J., Recent advances in magnetic structure determination by neutron powder diffraction. Phys. B Condens. Matter 192, 55–69 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Houska C. R., Smith T. M., Least-squares analysis of x-ray diffraction line shapes with analytic functions. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 748–754 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abramchuk M., Lebedev O. I., Hellman O., Bahrami F., Mordvinova N. E., Krizan J. W., Metz K. R., Broido D., Tafti F., Crystal chemistry and phonon heat capacity in quaternary honeycomb delafossites: Cu[Li1/3Sn2/3]O2 and Cu[Na1/3Sn2/3]O2. Inorg. Chem. 57, 12709–12717 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krivanek O. L., Chisholm M. F., Nicolosi V., Pennycook T. J., Corbin G. J., Dellby N., Murfitt M. F., Own C. S., Szilagyi Z. S., Oxley M. P., Pantelides S. T., Pennycook S. J., Atom-by-atom structural and chemical analysis by annular dark-field electron microscopy. Nature 464, 571–574 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amato A., Luetkens H., Sedlak K., Stoykov A., Scheuermann R., Elender M., Raselli A., Graf D., The new versatile general purpose surface-muon instrument (GPS) based on silicon photomultipliers for μSR measurements on a continuous-wave beam. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 88, 093301 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suter A., Wojek B. M., Musrfit: A free platform-independent framework for μSR data analysis. Phys. Procedia 30, 69–73 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cococcioni M., de Gironcoli S., Linear response approach to the calculation of the effective interaction parameters in the LDA+ U method. Phys. Rev. B 71, 035105 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Setten M. J., Giantomassi M., Bousquet E., Verstraete M. J., Hamann D. R., Gonze X., Rignanese G. M., The PseudoDojo: Training and grading a 85 element optimized norm-conserving pseudopotential table. Comput. Phys. Commun. 226, 39–54 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 54.D. Haskel, Fluo: Correcting xanes for self-absorption in fluorescence measurements. Computer program and documentation (1999); https://www3.aps.anl.gov/haskel/fluo.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text

Tables S1 to S5

Figs. S1 to S6

Crystallographic Information File (CIF) for Li2RhO3

Crystallographic Information File (CIF) for Ag3LiRh2O6